Abstract

Cyclic oligonucleotide based anti-phage signaling systems (CBASS) are a family of anti-phage defense systems that share ancestry with the animal cGAS-STING innate immune pathway. CBASS systems are composed of an oligonucleotide cyclase, which generates signaling cyclic oligonucleotides in response to phage infection, and an effector that is activated by the cyclic oligonucleotides and promotes cell death. Cell death occurs prior to the completion of phage replication, thus preventing the spread of phages to nearby cells. Here we analysed 38,000 bacterial and archaeal genomes and identified over 5,000 CBASS systems, which have diverse architectures with multiple signaling molecules, effectors and ancillary genes. We propose a classification system for CBASS that groups systems according to their operon organization, signaling molecules and effector function. Four major CBASS types were identified, sharing at least six effector subtypes that promote cell death by membrane impairment, DNA degradation or other means. We observed evidence of extensive gain and loss of CBASS systems, as well as shuffling of effector genes between systems. Our classification and nomenclature scheme is expected to guide future research in the developing CBASS field.

Introduction

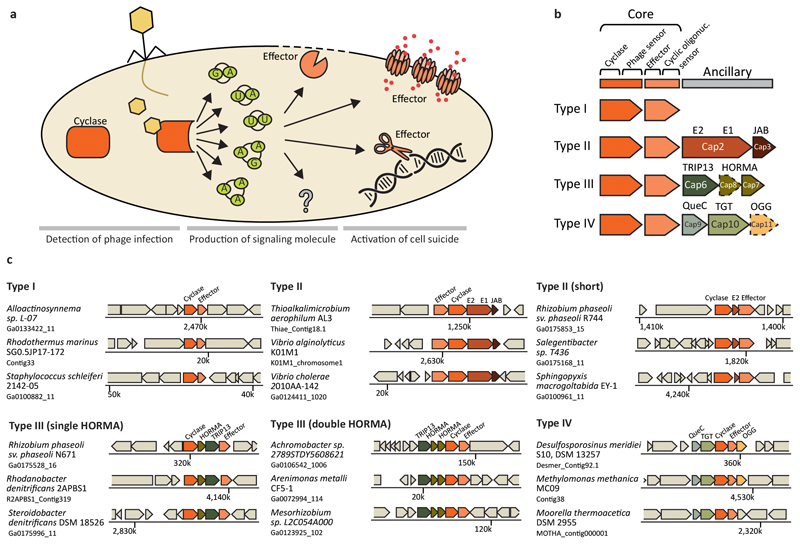

Bacteria and archaea have active defense systems to protect against viruses that infect them1–4. Recent studies in Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli have reported a bacterial defense system that is thought to share ancient common ancestry with the animal cGAS-STING antiviral pathway5. The bacterial cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase)6 generates cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) molecules upon sensing that the cell has been infected, and the cGAMP molecules activate a phospholipase7 that degrades the inner membrane of the bacterial cell which results in cell death5. cGAS-mediated cell death occurs before the phage is able to complete its replication cycle, so that no mature phage particles emerge from the infected cell and the phage does not spread to nearby cells5. This mode of bacterial defense was named CBASS (cyclic-oligonucleotide-based anti-phage signaling system)5. In general, CBASS systems are characterized by at least two proteins with the following minimal configuration: one protein is thought to sense the presence of the phage and then produces the cyclic oligonucleotide signal, and the second, effector protein senses the cyclic oligonucleotide signal and exerts the cell-suicide function (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1. General description of CBASS systems.

a | A general model for the mode of action of CBASS systems. Phage infection is sensed by the cyclase (or by the ancillary genes, together with the cyclase), leading to activation of the cyclase which generates a cyclic oligonucleotide signaling molecule. The signaling molecule is sensed by the effector and activates its cell killing function. CBASS cyclases can generate a variety of cyclic di- and tri-nucleotides, and CBASS effectors can exert cell death through membrane degradation, cleavage of phage and host DNA, formation of membrane-spanning pores, and other means whose mechanisms are yet to be identified. b | Four types of CBASS systems classified according to their ancillary gene content. Box arrows with dashed outlines represent genes that are present in some, but not all, of the systems in the respective CBASS type. Ancillary genes are denotes as Cap genes (CD-NTase-Associated Proteins). c | Representative instances of CBASS operons and their genomic neighborhood. The name of the bacterial species and the accession of the relevant genomic scaffold in the IMG database34 are indicated on the left.

Bioinformatic and functional analyses have revealed that variants of the CBASS system are widespread in bacterial and archaeal genomes, forming a large and highly diverse family of anti-phage defense systems5,8–11. Bacterial CBASS systems show variety in every part of the system, including the oligonucleotide cyclase, the signaling molecule produced, the effector cell-killing gene and ancillary genes5,8–10.

Here, we systematically analyze CBASS systems in microbial genomes and identify four major types of CBASS. We analyze the different protein domains associated with cyclic oligonucleotide recognition, effector activity, and ancillary functions, and propose a standardized nomenclature to describe CBASS diversity.

Results

The presence of an oligonucleotide cyclase gene of the CD-NTase family is the hallmark of CBASS systems5,8. To study the distribution and variation of CBASS systems in bacteria and archaea, we first searched for homologs of oligonucleotide cyclase genes in a set of 38,167 bacterial and archaeal genomes, belonging to 14,566 species (Methods). We found 5,756 such genes in 4,894 (13%) of the genomes, spanning, in agreement with previous analyses5,8, all major bacterial phyla as well as one archaeal phylum (Supplementary Tables 1–5). We then analyzed the genomic environment of the oligonucleotide cyclases and identified, in the majority of cases, the effector gene and additional commonly associated ancillary genes, which are denoted Cap genes (CD-NTase Associated Proteins)12 (Figure 1B, 1C; Methods). Following the analysis of these identified CBASS systems we propose a CBASS classification scheme that is based on three axes: the CBASS operon composition (CBASS types I, II, III and IV); the effector activity; and the signaling molecule produced by the oligonucleotide cyclase (Figure 1B). Overall we detected 5,675 cyclase-containing CBASS operons (with some operons containing more than one cyclase, see below).

Classification axis I - CBASS operon configuration

Type I CBASS: a compact, two-gene system

In 2,376 of the CBASSs we identified (42%), the system appears in a minimal configuration consisting of an oligonucleotide cyclase and an effector gene, without associated ancillary genes (Supplementary Table 1). As this is the most abundant CBASS configuration, we denote it “Type I”. A type I CBASS from Bacillus cereus, when cloned into Bacillus subtilis, was demonstrated experimentally to confer protection against phages, indicating that this two-gene minimal configuration does not necessitate ancillary genes for its anti-phage activity5. Type I CBASS can be found in all major phyla (Figure 2). The effector proteins in the majority of type I CBASS systems contain one or several transmembrane-spanning helices, which are predicted to form pores in the membrane once activated by the cyclic oligonucleotide signal (Figure 2D)5,11.

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic distribution of CBASS types and effectors.

a | Presence of CBASS systems in analyzed genomes, divided by phyla. Data for phyla with >100 genomes in the database are shown. Numbers above each bar represent the number of genomes from the specific phylum that contain CBASS out of the total number of genomes from the specific phylum that are present in the analyzed database. b | Presence of CBASS systems in species, divided by phyla. CBASS was counted as present in a species if at least one genome of that species contained CBASS. Numbers above each bar represent the number of species from the specific phylum that contain CBASS out of the total number of species from the specific phylum that are present in the analyzed database. c | Phyletic distribution of genomes per CBASS type. Data are shown for phyla with >200 genomes in the database. Rightmost bar depicts the phyletic distribution of all 38,167 genomes in the database for comparison purposes. d | Distribution of effector genes in each CBASS type.

Type II CBASS: ancillary genes encoding ubiquitin-associated domains

We found 2,199 CBASS systems (39%) encoding, in addition to the core cyclase-effector pair, two additional genes (called cap2 and cap3 12) that encode domains typical of the eukaryotic ubiquitin machinery. These systems are denoted type II CBASS. Cap2 comprises a fusion between a ubiquitin activating E1-like enzymatic domain and a ubiquitin conjugating E2-like domain. The second gene, cap3, encodes a protein domain predicted as an isopeptidase of the JAB /JAMM family, which is usually found in eukaryotic deubiquitinase enzymes that remove ubiquitin from target proteins. Two type II CBASS systems, one from E. coli and one from V. cholerae, were shown experimentally to confer defense against a phylogenetically wide set of coliphages, when cloned to a CBASS-less E. coli strain5. Interestingly, cap2 and cap3 were necessary for protection against some, but not all, of the phages, suggesting that these genes have an ancillary function in the CBASS system that expands the range of phages against which the system protects. As ubiquitin is not known to be present in E. coli or V. cholerae, it is still a mystery which protein is the target of the ubiquitin-handling domains encoded by the cap2 and cap3 ancillary genes. In the experimentally tested type II CBASS systems from E. coli and V. cholerae, the effector gene is a phospholipase that is thought to degrade the inner bacterial membrane once activated by the signaling molecule5,7; such phospholipase domains are the most common effector domains in type II CBASS systems (Figure 2D).

As the cap3 gene is short (160 amino acids on average), it is sometime not annotated in the genome in which the CBASS is identified. Nevertheless, examination of the intergenic regions downstream cap2 enabled the identification of cap3 in many cases (Supplementary Table 2). In a minority (19) of type II CBASS systems, cap2 and cap3 are fused, and in other cases (13) cap3 is fused to the effector gene. A subset of 616 (28%) of the type II CBASS systems have a minimal configuration that comprises, in addition to the cyclase-effector pair, only a short E2 domain gene, without E1 or JAB (Table S1; Figure 1C). It is unclear whether this subtype functions on its own or uses other genes in the cell to fill in for the missing E1 and JAB functions.

Type III CBASS: ancillary genes encoding HORMA and TRIP13 domains

About 10% of the CBASS systems we identified (572 systems) are associated with another set of ancillary genes, which, interestingly, also encode protein domains that were so far mainly described in eukaryotes13. One of these genes (hereafter called cap7) encodes a HORMA-domain protein; such proteins form signaling complexes that control steps in meiosis, mitosis and DNA repair in eukaryotes14. The second gene (cap6) comprises a TRIP13 domain (also called Pch2 domain), which is a known inhibitor of HORMA-domain proteins activity. In eukaryotes, TRIP13 proteins dissociate the HORMA signaling complexes and thus turn off the signal15.

A type III CBASS from E. coli MS115-1 was shown to provide protection against phage lambda infection9. The oligonucleotide cyclase in this system produces cyclic tri-adenylate molecules (cAAA) in response to phage infection, and this molecule was shown to activate the effector protein, an endonuclease, that non-discriminately and completely degrades both phage and host DNA leading to abortive infection and cell death9,10. It was shown that the HORMA-domain protein (Cap7) is essential for phage defense, and that the oligonucleotide cyclase becomes active only when physically bound by the HORMA-domain protein. The TRIP13 protein Cap6, on the other hand, was shown to dissociate the HORMA protein from the oligonucleotide cyclase, indicating that TRIP13 is a negative regulator of cyclic oligonucleotide production9. Based on these results it was suggested that under normal conditions Cap6 prevents Cap7 from associating with and activating the oligonucleotide cyclase; but during phage infection, Cap7 recognizes the infection (perhaps via binding to a phage-encoded protein), and changes its conformation to remain bound to the oligonucleotide cyclase. This binding activates the production of the cyclic oligonucleotide molecule, which, in turn, activates the effector protein leading to cell death before the phage has completed its replication cycle 9,10 .

Type III systems are overrepresented in Proteobacteria and are almost completely absent from Firmicutes (Figure 2C). These CBASS systems appear in two main configurations: one with a single HORMA-domain protein (cap7), and the second with two HORMA-domain proteins where one of the two HORMA-domain proteins (which we denote cap8) is significantly divergent and is identifiable only via structure-based, but not sequence based, comparisons9 (Figure 1C). This divergent cap8 HORMA was not found to activate the cyclase in vitro and was therefore suggested to function as a scaffold9. The oligonucleotide cyclases that are present in the two type III subtypes form two distinct clades on the phylogenetic tree of the oligonucleotide cyclase family (Extended Data Fig. 1). A specific subclade of the type III CBASS systems (102 cases, 18% of type III systems) contains an additional ancillary gene with a predicted 3’-5’ exonuclease domain (Supplementary Table 3).

Type IV: ancillary proteins with nucleotide-modifying domains

Type IV is a rare form of CBASS, with only 43 instances in the analyzed genomes, appearing mostly in archaea and Firmicutes. Type IV CBASS comprises two ancillary genes (cap9 and cap10) with protein domains involved in nucleotide modification. Cap9 contains a predicted QueC enzymatic domain, which is known to convert the modified base 7-carboxy-7-deazaguanine (CDG) to 7-cyano-7-deazaguanine (preQ0)16,17. Cap10 encodes a predicted enzyme called TGT, that catalyzes base-exchange of a specific guanine residue with preQ0 in tRNAs18. Genes encoding these enzymatic domains were also shown to modify guanine residues on DNA as part of a restriction-modification system called dpd19. In 12 (28%) of the type IV CBASS systems, another gene (cap11) annotated as an N-glycosylase/DNA lyase (OGG) is also present in the CBASS operon. N-glycosylase/DNA lyases are known to remove damaged guanine bases (8-oxoG) from the DNA and to nick DNA in apurinic/apyrimidinic sites20. To date, no type IV CBASS systems were demonstrated to defend against phages, and the function of their ancillary genes remains obscure.

Type IV systems are enriched in archaea and form two clades on the phylogenetic tree of the oligonucleotide cyclase family (Extended Data Fig. 1), one of which is a distinct, previously unreported clade. Notably, the relatively small number of sequenced archaeal genomes in the databases (representing only 2.5% of the set of >38,000 genomes we analyzed) may have led to an under-representation of type IV CBASSs in our set of genomes.

Standalone oligonucleotide cyclases

We detected 485 (9%) cases where the oligonucleotide cyclase gene was not associated with effector and/or ancillary genes (Supplementary Table 4). In many cases, these standalone cyclases appear at or near the edge of partially assembled genomic scaffolds, most probably representing cases where the remainder of the CBASS operon was in the not-yet-assembled part of the draft genome. Other cases of standalone cyclases may represent degenerated, pseudogenized CBASS systems in which some of the genes were mutated or deleted, or cases where the effector gene is not adjacent to the cyclase but is rather found elsewhere on the genome. We cannot rule out the possibility that some oligonucleotide cyclases exert their function as standalone genes. Indeed, we detected 3 cases in which CBASS systems appear on a single gene, which comprises a fusion between the oligonucleotide cyclase and the effector gene (Supplementary Table 5).

Classification axis II - the effector cell-killing domain

The effector gene of CBASS systems is usually composed of two domains: the cyclic oligonucleotide sensing domain, and the cell-killing domain that becomes activated once the cyclic oligonucleotide is sensed. The various cell-killing domains can be associated with several CBASS types. In our CBASS classification scheme we mark cell-killing domains by capital letters (for example, A stands for a phospholipase domain, B for transmembrane domains, C for endonuclease domain, etc.; see below). Hence, CBASS type I-A stands for a type I system with a phospholipase effector, and CBASS type II-C stands for a type II system with an endonuclease effector.

The following cell-killing domains are identified in CBASS effector genes. In some cases, they were shown to cause cell death; in others, the cell-killing effect is hypothesized but was not yet examined experimentally.

A. Patatin-like phospholipase

Effector proteins with this domain were shown to degrade the phospholipids of the inner cell membrane, as demonstrated in vitro as well as by in vivo studies in V. cholerae 7. This leads to a change in the cell shape and eventual cell lysis5. Effector genes with phospholipase domains are found both in type I and type II CBASSs, but are absent from types III and IV. These effectors are the most common effectors in type II CBASS (Figure 2D).

B. Effectors with two (2TM) or four (4TM) transmembrane helices

This effector class is composed of proteins that do not have an identifiable enzymatic domain, but rather encode transmembrane helices. These effectors are predicted to promote cell death by forming pores in the cell membrane once they become activated by the cyclic oligonucleotide5,11. 2TM effectors are the most common effector class in type I and type IV CBASSs, and are rare in type III systems (Figure 2D).

Several protein families (Pfams) have been designated by Aravind and colleagues11 to identify CBASS-associated 2TM effector domains (Table 1). A minority of 2TM effectors contain an additional functional domain annotated as a NUDIX hydrolase11 (Table 1). This domain is known to cleave nucleoside diphosphate molecules linked to other moieties21, and hence this subclass of effectors probably exerts another function instead, or in addition to, forming membrane pores.

Table 1. Protein families (Pfams) commonly associated with CBASS systems in prokaryotes.

| PFAM | FUNCTION IN CBASS | ADDITIONAL NAMES |

|---|---|---|

| PF18144 | Oligonucleotide cyclase | CD-NTase8 |

| PF18134 | Domain of unknown function fused to cyclases | AGS-C11 |

| PF18145 | Oligonucleotide-sensing domain | SAVED11 |

| PF18178 | Oligonucleotide-sensing domain | TPALS11 |

| PF15009 | Oligonucleotide-sensing domain (STING) | STING |

| PF18153 | Effector domain (2TM) | S_2TMBeta11 |

| PF18179 | Effector domain (2TM) | SUa-2TM11 |

| PF18303 | Effector domain (2TM) | SAF 2TM11 |

| PF18181 | Effector domain (2TM) | SLATT11 |

| PF18183 | Effector domain (2TM) | SLATT11 |

| PF18184 | Effector domain (2TM) | SLATT11 |

| PF18186 | Effector domain (2TM) | SLATT11 |

| PF18160 | Effector domain (2TM) | SLATT11 |

| PF18169 | Effector domain (2TM) | SLATT11 |

| PF18167 | Effector domain (2TM) | SMODS-associated NUDIX domain11 |

| PF18159 | Effector domain (4TM) | S-4TM11 |

| COG3105 | Effector domain (1TM) | DUF1043 |

| PF00899 | Ancillary gene, type II (E1 domain) | |

| PF14461 | Ancillary gene, type II (E2 domain) | |

| PF14464 | Ancillary gene, type II (JAB domain) | |

| PF18173 | Ancillary gene, type III (HORMA domain) | |

| PF18138 | Ancillary gene, type III (HORMA domain) |

Some CBASSs encode effector proteins with four transmembrane helices (4TM). This is possibly a fusion of two 2TM effectors, containing two distinct 2TM effector domains. A 4TM effector was demonstrated to promote infection-mediated cell death in the type I CBASS system of B. cereus VD1465. Interestingly, about 10% of the systems with a 4TM effector have two cyclase genes (compared to ~1% in systems with other effectors), suggesting that the effector may respond to signals from the two cyclases (see below).

Finally, several CBASS effectors (69 of the cases) involve a single transmembrane domain (1TM). Most of these are annotated with a domain of unknown function DUF1043.

C. Endonuclease

Another common effector type encodes an endonuclease domain (Figure 2D). Endonuclease domains are found mostly in CBASS types II and III. Three different subclasses of endonuclease domains appear with these effectors: HNH endonuclease (CBASS types I and II), NucC endonuclease (mostly in type III CBASS), a recently identified endonuclease of pfam family PF14130 (formerly called DUF4297)12, and rarely Mrr or calcineurin-like nucleases. The NucC-domain effector protein of type III CBASS from E. coli MS115-1 was shown to be activated by its cognate cyclic oligonucleotide (cyclic tri-adenylate), and, once activated, it was shown to degrade double stranded DNA indiscriminately to fragments sized 50-100 bp10. DNA degradation during the infection process eliminates both phage and host genomes, aborting the infection and leading to cell death10. In a similar manner, effector proteins that contain the DUF4297 endonuclease (denoted Cap4) or the HNH endonuclease domain (Cap5) were shown to degrade DNA into short fragments when activated by their cognate cyclic oligonucleotide molecules12.

D. TIR domains

TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor) domains were originally found in pathogen-sensing innate immunity proteins in eukaryotes22. These domains were recently shown to participate in a widespread anti-phage defense system called Thoeris, whose mechanism of action is yet to be deciphered2. The presence of TIR domains within CBASS effectors mark TIRs as possibly exerting a cell-killing function. Three subclasses of TIR-domains are associated with CBASS systems: (i) a TIR-like domain fused to a STING domain in type I CBASS; (ii) a TIR-like domain fused to a cyclic oligonucleotide sensor domain annotated with a Pfam PF18145 in type II systems; and (iii) a TIR-like domain fused to a cyclic oligonucleotide sensor domain annotated with a Pfam PF18178 in type III systems.

E. Phosphorylase/nucleosidase superfamily

Protein domains with this annotation are found rarely (60 cases in our set) in effector genes from type III CBASS systems.

F. Peptidase

Peptidases of the caspase-like superfamily are found, rarely (20 such cases in our set), in effector genes that mostly belong to type I CBASS. We postulate that this domain may be involved in cell suicide, perhaps by cleave of essential cellular proteins.

Classification axis III - the signaling molecule

In a recent comprehensive study, Kranzusch and colleagues have shown that the bacterial cGAS protein, originally detected in V. cholerae 6, is part of a large and diverse family of oligonucleotide cyclases (CD-NTases) widespread in microbes8. Various cyclases from the CD-NTase family have been experimentally shown to generate a variety of cyclic di- and tri- nucleotides including cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), cyclic UMP-AMP, cyclic UMP-UMP, cyclic AMP-AMP-GMP, and more8. CBASSs of the same type can encode different cyclases that produce different signaling molecules (Table 2). We propose to depict the biologically active signaling molecule of CBASS systems as a superscript, so that, for example, a type II CBASS with a phospholipase effector that utilizes cyclic UMP-AMP signaling molecule will be named CBASS type II-AUA (Table 2).

Table 2. Experimentally studied CBASS systems and their classifications.

| Species | Cyclase | Effector | Ancillary genes | Signaling molecule | CBASS classification | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli V. cholerae | DncV (cGAS) | Phospholipase | E1-E2, JAB | cGAMP | Type II-AGA | 5 |

| P. aeruginosa Xanthomonas citci | CD-NTase002 CD-NTase003 | Phospholipase | E1-E2, JAB | cGAMP | Type II-AGA | 8 |

| E. coli | CdnE | Phospholipase | E1-E2, JAB | Cyclic UMP-AMP | Type II-AUA | 8 |

| Legioiwhla pneemophila | Lp-CdnE02 | 2TM | None | Cyclic UMP-UMP | Type I-BUU | 8 |

| Eniarobactcr clcaoac | Ec-CdnD02 | Endonuclease | E1-E2, JAB | Cyclic AMP-AMP-GMP | Type II-CAAG | 8,12 |

| E. coli | CdnC | Endonuclease | HORMA, TRIP13 | Cyclic AMP-AMP-AMP | Type III-CAAA | 9 |

| P. aeruginosa | CdnD | Endonuclease | HORMA x 2, TRIP13 | Cyclic AMP-AMP-AMP | Type III-CAAA | 9 |

| B. cereus | IK1 05630 | 4TM | None | Unknown | Type I-B | 8 |

| Acinehobacter baamaomi | AbCdnD | Endonuclease | E1-E2, JAB | Cyclic AMP-AMP-AMP-AMP | Type II-CAAAA | 12 |

The phylogenetic tree of the oligonucleotide cyclase proteins is presented in Extended Data Fig. 1. This tree largely follows the trees for this family of proteins presented in refs5,8, and we now add the updated CBASS and effector types overlaid on the tree (Extended Data Fig. 1).

CBASS effector genes must encode cyclic oligonucleotide-sensing domains that match the signaling molecule produced by their cognate oligonucleotide cyclase. About 30% of the effector proteins in CBASS systems encode a domain called SAVED11, which was recently shown to form the oligonucleotide sensing platform in the effector protein. Divergence in SAVED nucleotide binding pockets enables the specific recognition of a large variety of cyclic oligonucleotides that differ in ring size and composition12. Other protein domains that are found in CBASS effector proteins that do not encode SAVED domains are predicted to form additional oligonucleotide sensing platforms (Table 1).

Variations on a theme

In addition to the common CBASS configurations presented above, several variations are worth mentioning. There are 78 cases in which the CBASS operon contains two oligonucleotide cyclase enzymes (Supplementary Tables 1–5). Interestingly, the majority (53%) of these CBASSs encode a 4TM effector that seems, as mentioned above, like a fusion of two 2TM effectors. It is possible that these systems represent an actual fusion of two CBASS effectors, and that each half of the effector senses the signaling molecule generated by one of the two associated oligonucleotide cyclases but not the other.

In 914 of the CBASS systems we examined, the oligonucleotide cyclase gene contains an extra domain (Pfam PF18134). The vast majority (98%) of these cases are type I systems (Supplementary Table 1). This protein domain has previously been suggested to function as a cyclic oligonucleotide sensor11; but its presence in the oligonucleotide cyclase protein suggests that its role may be to identify the invading phage. The abundance of the PF18134 protein domain specifically in type I CBASSs may also imply that this domain replaces the function of the ancillary genes, which are naturally missing from type I systems.

An interesting variant of CBASS systems lacks the hallmark oligonucleotide cyclase gene. Instead, these systems contain a gene annotated as an adenylate/guanylate cyclase, and an effector gene with a cyclic AMP (cAMP)-binding domain instead of the common cyclic oligonucleotide binding domain (Supplementary Tables 6–7). We found 460 such systems (303 of type I CBASS and 127 of type II CBASS), and it is possible that in these systems the signaling molecule is a single nucleotide with a cyclic monophosphate rather than a cyclic oligonucleotide. As cAMP is frequently used for housekeeping signaling functions in bacteria23, it is likely that the signaling molecule is cGMP. Alternatively, it is possible that the adenylate cyclase gene produces a cAMP variant that differs from the housekeeping cAMP (for example, perhaps the cyclic phosphate is formed by covalent linkage with the 2’ carbon of the ribose instead of the 3’ carbon).

Evolutionary shuffling of CBASS systems and genes

Many anti-phage defense systems were shown to be subject to rampant horizontal gene transfer1,24,25. It was suggested that bacteria employ horizontal gene transfer to access defense mechanisms encoded by the “pan immune system” of closely related strains1. In accordance with this, we find that different strains of the same species can host different CBASS types and effectors, sometimes with multiple systems in the same genome (Figure 3a). This checkered pattern of CBASS distribution in closely related genomes suggests rapid gain and loss of CBASS systems, consistent with the current theory on the pan immune system of bacteria1. We found 561 genomes that contain more than one CBASS, with some genomes containing 4 or even 5 such systems (Supplementary Tables 1–7).

Fig. 3. Rapid gain and loss of and gene shuffling in CBASS systems.

a | Presence of different CBASS systems in closely related genomes. Each row represents a different strain of either Escherichia coli (left) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (right), each column corresponds to a different CBASS type (colored boxes indicate the presence of the CBASS system; grey boxes depict absence of CBASS). Letter within the box represents the effector type (A, phospholipase; B, transmembrane domains; C, endonuclease; E, domain of unknown function DUF4297; F, phosphorylase/nucleosidase). P. aeruginosa strain ST-111 refers to ST-111 38_London_12_VIM_2_08_12. b | Phylogenetic tree of 3 highly similar cyclases (80-85% protein sequence identity) that belong to a type III CBASS. The % identity between each protein and its cognate protein in the neighboring leaf of the tree is depicted.

Examination of the phylogenetic tree of oligonucleotide cyclases show evidence for shuffling of cyclase and effector genes between CBASS systems (Extended Data Fig. 1). Cyclase genes that are phylogenetically close to each other on the tree (i.e, having similar sequences) can be associated with different effector types and even with different CBASS types (Extended Data Fig. 1). In some cases we find highly similar systems (>80% identity when comparing the cyclase proteins) that have completely different effectors (Figure 3b). Presumably, such a shuffling of effector genes between CBASS systems is evolutionarily driven by the necessity to mitigate infection by phages that can inhibit or overcome some of the effectors.

Discussion

We have classified the vast diversity of CBASS systems into a streamlined nomenclature that will hopefully assist researchers to give recognizable names to CBASS systems they study. The three classification identifiers are operon organization, effector type and signaling molecule, and applying this classification strategy will enable straightforward description of most CBASSs, providing a common language for research in the field. The complexity of CBASS systems parallels that of CRISPR systems, for which similar past classifications were instrumental in generating a common language for research in the field26,27.

CBASS types differ by the content of their ancillary genes. In type II and type III CBASSs, the proteins encoded by the ancillary genes have counteractive functions. In type III CBASS, the Cap7 HORMA-domain protein activates the oligonucleotide cyclase by directly binding to it, and the Cap6 TRIP13 protein inhibits this activation by dissociating Cap7 from the cyclase enzyme9. In a similar manner, it is predicted that the Cap2 ancillary protein of type II CBASSs would use its E1 and E2 domains to conjugate a (yet unidentified) moiety to a target protein to possibly activate the cyclase enzyme, while the Cap3 JAB-domain isopeptidase protein would counteract this activity by removing this moiety from its target.

An interesting parallel of the CBASS system is found in type III CRISPR-Cas systems. Upon recognition of foreign nucleic acids by the crRNA/protein complex of type III CRISPR-Cas, the Cas10 subunit of the complex generates a cyclic oligoadenylate molecule (comprised of two to six adenosine monophosphate molecules conjugated in a cyclic form)28,29. This molecule then binds and activates the RNase effector Csm6 that indiscriminately degrades the RNA of both host and phage, presumably leading to cell dormancy or death28,29. In at least some cases, bona fide CBASS effectors such as the NucC endonuclease function as effectors of type III CRISPR-Cas systems10, suggesting that these two defense systems share functional components.

Interactions between bacteria and phage have led to the evolution of multiple and diverse bacterial immune systems. Many of these systems, including CBASS, are absent from many model organisms and have only been discovered very recently by studying genomes of non-model organisms1,2,5,30–33. It is likely that many more novel defense systems will be discovered that will showcase the manifold ways bacteria have evolved to defend against virus infection.

Methods

Identification of CBASS cyclases and operon types

Protein sequences of all genes in 38,167 bacterial and archaeal genomes were downloaded from the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) database34 in October 2017. These proteins were clustered using the ‘cluster’ option of MMseqs235 (release 2-1c7a89), with default parameters. The sequences of each cluster were aligned using Clustal Omega36. Multiple sequence alignments of clusters of 10 or more proteins were scanned with HHsearch37 using 50% gap rule (-M 50) against the PDB_mmCIF7038 and Pfam3239 databases. For clusters with less than 10 proteins a step of HHblits37 with two iterations was used before scanning with HHsearch. Clusters with HHsearch hits to one of the cGAS entries (Protein Data Bank (PDB) codes: 4LEV, 4MKP, 4O67, 5VDR, 5V8H, 4LEW, 5VDP, 4KM5, 4O68, 4O69, 5V8J, 5V8N, 5V8O, 5VDO, 5VDQ, 5VDS, 5VDT, 5VDU, 5VDV, 5VDW, 4XJ5, 4XJ1, 4XJ6, 4XJ3 and 4XJ4, and Pfam PF03281) with >90% probability in the top 30 hits were taken for manual analysis. Fragmented cyclase genes were counted as a single gene in further analyses.

To identify the CBASS operon types the genomic environments spanning 10 genes upstream and downstream of each of the predicted oligonucleotide cyclase genes were searched to identify conserved gene cassettes, as previously described2,5. Predicted systems were manually reviewed and unrelated genes (for example, mobilome genes and genes of other defense systems) were omitted.

To search for unannotated JAB proteins, the nucleotide sequences of E1-E2 genes from type II CBASS operons that do not contain JAB were extracted, along with 2,000 nt upstream and downstream. These sequences were searched using Blastx against the JAB protein from the CBASS operon of E. coli TW116815. Hits with e-value < 0.01 were considered as cases in which JAB is present. The same process was used to detect unannotated E2 genes.

Phylogenetic analysis

Genomes that contain CBASS were counted for each phylum. A species was counted as containing CBASS (for Figure 2b) if at least one of the genomes belonging to the species had a CBASS system.

To generate the phylogenetic tree in Extended Data Fig. 1, cyclases that do not have 10 genes upstream and downstream were removed. The ‘clusthash’ option of MMseqs2 (release 6-f5a1c) was used to remove protein redundancies (using the ‘-min-seq-id 0.9’ parameter). Sequences shorter than 200 amino acids were also removed. The human cGAS protein (UniProt Q8N884) was added, as well as the human oligoadenylate synthase genes (UniProt P00973, P29728 and Q9Y6K5); these were used as outgroup. Sequences were aligned using clustal-omega 1.2.4 with default parameters. The FastTree software40 was used to generate a tree from the multiple sequence alignment using default parameters. The iTOL41 software was used for tree visualization. Clades where colored according to refs 5,8.

Search for CBASSs AMP/GMP cyclases

The genomic environments spanning 10 genes upstream and downstream of E1-E2 genes were searched to identify conserved gene cassettes, as previously described2,5. Genes associated with E1-E2-containng operons that did not contain an oligonucleotide cyclase were mapped to their respective cluster (see the explanation for the protein clustering above). Multiple sequence alignments of proteins in these clusters were scanned with HHsearch37 using 50% gap rule (-M 50) against the Pfam3239 database. Clusters with hits to Pfam PF00211 with >90% probability in the top 30 hits were then manually examined.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Phylogenetic analysis of oligonucleotide cyclases (CD-NTase) and their CBASS types.

The phylogenetic tree of all cyclases, as depicted and colored in refs (5 and 8) is presented in the center. Each clade is then expanded and presented in the periphery as a circular tree to increase resolution. Outer ring depicts the effector type; middle ring depicts the system type. Numbers next to each clade represent the bootstrap value for that node in the central tree.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Sorek laboratory members for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. A.M. was supported by a fellowship from the Ariane de Rothschild Women Doctoral Program. R.S. was supported, in part, by the Israel Science Foundation (personal grant 1360/16), the European Research Council (grant ERC-CoG 681203), the German Research Council (DFG) priority program SPP 2002 (grant SO 1611/1-1), the Israeli Council for Higher Education via the Weizmann Data Science Research Center, the Ernest and Bonnie Beutler Research Program of Excellence in Genomic Medicine, the Minerva Foundation with funding from the Federal German Ministry for Education and Research, and the Knell Family Center for Microbiology.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.M. collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. S.M. and G.A. were involved in classification of CBASS systems. R.S. supervised this study and wrote the paper.

Competing interests

R.S. is a scientific cofounder and consultant of BiomX, Pantheon Bioscience and Ecophage

Data availability statement

All genomic data that support the findings of this study are available in IMG, https://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/mer/main.cgi. Accession codes for all data are provided in Supplementary Tables 1–7.

PDB and Pfam databases are available at the HHsuite database page: http://wwwuser.gwdg.de/~compbiol/data/hhsuite/databases/hhsuite_dbs/

References

- 1.Bernheim A, Sorek R. The pan-immune system of bacteria: antiviral defence as a community resource. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:113–119. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doron S, et al. Systematic discovery of antiphage defense systems in the microbial pangenome. Science. 2018;359:eaar4120. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rostøl JT, Marraffini L. (Ph)ighting Phages: How Bacteria Resist Their Parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampton HG, Watson BNJ, Fineran PC. The arms race between bacteria and their phage foes. Nature. 2020;577:327–336. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen D, et al. Cyclic GMP–AMP signalling protects bacteria against viral infection. Nature. 2019;574:691–695. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies BW, Bogard RW, Young TS, Mekalanos JJ. Coordinated regulation of accessory genetic elements produces cyclic di-nucleotides for V. cholerae virulence. Cell. 2012;149:358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Severin GB, et al. Direct activation of a phospholipase by cyclic GMP-AMP in El Tor Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E6048–E6055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801233115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteley AT, et al. Bacterial cGAS-like enzymes synthesize diverse nucleotide signals. Nature. 2019;567:194–199. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0953-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye Q, et al. HORMA Domain Proteins and a Trip13-like ATPase Regulate Bacterial cGAS-like Enzymes to Mediate Bacteriophage Immunity. Mol Cell. 2020;77:709–722.:e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau RK, et al. Structure and Mechanism of a Cyclic Trinucleotide-Activated Bacterial Endonuclease Mediating Bacteriophage Immunity. Mol Cell. 2020;77:723–733.:e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burroughs AM, Zhang D, Schäffer DE, Iyer LM, Aravind L. Comparative genomic analyses reveal a vast, novel network of nucleotide-centric systems in biological conflicts, immunity and signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:10633–10654. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowey B, et al. CBASS Immunity Uses CARF-Related Effectors to Sense 3’-5’- and 2’-5’-Linked Cyclic Oligonucleotide Signals and Protect Bacteria from Phage Infection. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The HORMA domain: a common structural denominator in mitotic checkpoints, chromosome synapsis and DNA repair. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:284–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg SC, Corbett KD. The multifaceted roles of the HORMA domain in cellular signaling. J Cell Biol. 2015;211:745–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201509076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vader G. Pch2(TRIP13): controlling cell division through regulation of HORMA domains. Chromosoma. 2015;124:333–9. doi: 10.1007/s00412-015-0516-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reader JS, Metzgar D, Schimmel P, de Crécy-Lagard V. Identification of four genes necessary for biosynthesis of the modified nucleoside queuosine. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6280–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarty RM, Somogyi A, Lin G, Jacobsen NE, Bandarian V. The deazapurine biosynthetic pathway revealed: in vitro enzymatic synthesis of PreQ(0) from guanosine 5’-triphosphate in four steps. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3847–52. doi: 10.1021/bi900400e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okada N, et al. Novel mechanism of post-transcriptional modification of tRNA. Insertion of bases of Q precursors into tRNA by a specific tRNA transglycosylase reaction. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:3067–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiaville JJ, et al. Novel genomic island modifies DNA with 7-deazaguanine derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1452–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518570113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.David SS, O’Shea VL, Kundu S. Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nature. 2007;447:941–950. doi: 10.1038/nature05978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLennan AG. The Nudix hydrolase superfamily. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:123–43. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5386-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Botsford JL, Harman JG. Cyclic AMP in prokaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:100–22. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.100-122.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Wolf YI. Evolutionary Genomics of Defense Systems in Archaea and Bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:233–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Houte S, Buckling A, Westra ER. Evolutionary Ecology of Prokaryotic Immune Mechanisms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80:745–63. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00011-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makarova KS, et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:467–77. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makarova KS, et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:722–36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazlauskiene M, Kostiuk G, Venclovas C, Tamulaitis G, Siksnys V. A cyclic oligonucleotide signaling pathway in type III CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. 2017;357:605–609. doi: 10.1126/science.aao0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niewoehner O, et al. Type III CRISPR-Cas systems produce cyclic oligoadenylate second messengers. Nature. 2017;548:543–548. doi: 10.1038/nature23467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ofir G, et al. DISARM is a widespread bacterial defence system with broad anti-phage activities. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:90–98. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0051-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldfarb T, et al. BREX is a novel phage resistance system widespread in microbial genomes. EMBO J. 2015;34:169–183. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ofir G, Sorek R. Contemporary Phage Biology: From Classic Models to New Insights. Cell. 2018;172:1260–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopatina A, Tal N, Sorek R. Abortive Infection: Bacterial Suicide as an Antiviral Immune Strategy. Annu Rev Virol. 2020;7 doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-011620-040628. annurev-virology-011620-040628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen IMA, et al. IMG/M v.5.0: An integrated data management and comparative analysis system for microbial genomes and microbiomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D666–D677. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinegger M, Söding J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:1026–1028. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sievers F, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinegger M, et al. HH-suite3 for fast remote homology detection and deep protein annotation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20:473. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-3019-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berman HM, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Gebali S, et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D427–D432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. Fasttree: Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All genomic data that support the findings of this study are available in IMG, https://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/mer/main.cgi. Accession codes for all data are provided in Supplementary Tables 1–7.

PDB and Pfam databases are available at the HHsuite database page: http://wwwuser.gwdg.de/~compbiol/data/hhsuite/databases/hhsuite_dbs/