Abstract

Cholera remains a major risk in developing countries, particularly after natural or man-made disasters. Vibrio cholerae El Tor is the most important cause of these outbreaks, and is becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics, so alternative therapies are urgently needed. In this study, a single bacteriophage, Phi_1, was used to control cholera prophylactically and therapeutically in an infant rabbit model. In both cases, phage-treated animals showed no clinical signs of disease, compared with 69% of untreated control animals. Bacterial counts in the intestines of phage-treated animals were reduced by up to 4 log10 colony-forming units/g. There was evidence of phage multiplication only in animals that received a V. cholerae challenge. No phage-resistant bacterial mutants were isolated from the animals, despite extensive searching. This is the first evidence that a single phage could be effective in the treatment of cholera, without detectable levels of resistance. Clinical trials in human patients should be considered.

Keywords: bacteriophage therapy, cholera, phage, infant rabbit, prophylaxis, Vibrio cholera

Vibrio cholerae has caused 7 cholera pandemics since 1817, leading to significant morbidity and mortality [1]. The first 6 pandemics (1816–1923) were caused by the Classical O1 biotype, whereas the seventh (1961 to the present) was caused by the El Tor biotype [1]. The current pandemic affects 3–5 million persons per annum, causing 21 000–143 000 deaths [1, 2]. Cholera is contracted from contaminated food and water in developing countries, where sanitation is generally inadequate or has been damaged by wars or natural disasters, and it is then transmitted from person to person [3].

Rehydration therapy reduces mortality rates and, with antibiotics, can diminish the intensity and duration of clinical signs and fecal shedding [4]. However, the World Health Organization now advises that only severe cases of cholera should be treated with antibiotics owing to the spread of antimicrobial resistance. Alternative approaches to cholera control are urgently needed, for both treatment of primary infections and prevention of secondary spread. Biological control using bacteriophages (phages) is one alternative, particularly where antibiotic resistance is a problem [5]. Phages have been used to treat experimental infections in a range of animal models including mice, chickens, cattle, pigs, and lambs [6–8].

In this study, we show that a phage vB_VchoP_1 (Phi_1) belonging to the Podoviridae N4virus genus was highly effective (P < .001) in preventing clinical symptoms of V. cholerae infection in infant rabbits, the most relevant animal model of cholera in humans. Phage treatment was accompanied by significant reductions (P < .05) in V. cholerae recovered from several intestinal compartments compared with untreated control animals. Notably, we recovered no phage-resistant mutants. The current study is the first showing that a single phage can prevent clinical symptoms of cholera infection in this model, with no evidence of resistance development. Its findings demonstrate that phage could be a viable alternative treatment for cholera in humans, and further research to support the application of phage in clinical trials is warranted.

Methods

Bacteriophage Isolation

Phage isolation from lake water samples from several locations in eastern China was performed as described elsewhere [9], using host V. cholerae O1 strain 2095. Plaques were serially purified a minimum of 5 times before further use. Additional phage isolates Phi_1, Phi_2, and Phi_3 were obtained from Tom Cheasty, former head of the Gastrointestinal Infections Reference Unit, Public Health England. Phages Phi_24 and Phi_X29 were purchased from the Felix d’Herelle Reference Centre for Bacterial Viruses.

Bacteriophage Propagation

Liquid lysates (10 mL) were prepared by inoculating mid-exponential cultures of V. cholerae with phage at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 and incubating them overnight at 37°C in an orbital shaker at 150 rpm. The lysate was centrifuged (at 10 000g for 10 minutes) and filtered (0.45-μm pore size; Sartorius). Phage titers were determined by plating decimal dilutions of lysates onto duplicate Luria Bertani (LB) agar plates using the agar overlay method [10]. The top agar from plates showing semiconfluent lysis was transferred to a 250-mL centrifuge tube, to which was added 5 mL of Sodium Magnesium (SM) buffer per plate. Phages were eluted by incubation at 4°C overnight with gentle shaking, followed by 2 rounds of centrifugation (at 4000g for 10 minutes and 4°C), filtration (0.45-μm pore size), and storage at 4°C.

Host Range Profile

Agar overlays of each of the 89 V. cholerae strains (Supplementary Table 1) were prepared as described above. Aliquots (10 μL) of each phage (108 plaque-forming units [PFUs]/mL) were spotted onto the bacterial lawns and left to dry. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and then scored for lysis, as reported elsewhere [11].

One-Step Growth Curve

A mid-exponential-phase culture of V. cholerae was infected with a single phage (multiplicity of infection, 0.1). After phage adsorption, the suspension was diluted in LB broth to a final concentration of 104 colony-forming units (CFUs)/mL [9]. Samples (1 mL) of the infected culture were collected at 5-minuted intervals for 90 minutes and filtered (0.45-μm pore size). The phages were enumerated on agar overlays as described above, and the burst size was calculated [12].

DNA Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation of Phage Genome

Phage genomic DNA was extracted using a Wizard DNA Clean-Up system (A7280; Promega). Next-generation sequencing was performed by Source Biosciences and NU-OMICS using the Illumina Miseq platform, with a 2 × 250–base pair paired-end run. The sequence data were assembled de novo, and single contigs for the phage were generated using the SPAdes version 3.1.0 assembler [13] with 120× coverage. The data quality was checked using FastQC software (Babraham Bioinformatics) and reads were quality trimmed. Genome annotation was carried out using RAST (version 2.0) [14] and Geneious (version 6.1.7; Biomatters) software with some manual curation, which provided the translated sequences of protein-coding regions. These sequences were used to interrogate the National Center for Biotechnology Information database using the protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Conserved protein motifs were identified using a HHpred search of the Pfam database [15]. With protein BLAST analysis, proteins were assigned to a gene sequence only when there was ≥90% identity with protein motifs in the database. The transfer RNA (tRNA) annotation was performed using tRNAscan-SE (version 2.0) [16] and ARAGORN (version 1.2.38) [17] software. After annotation, the genome was submitted to GenBank (Supplementary Table 2). The nucleotide sequence alignments were performed by ClustalW (Clustal 2.1) [18]. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis was performed using the generalized time-reversible model with FastTree software [19] and the phylogeny was visualized using FigTree software, version 1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree).

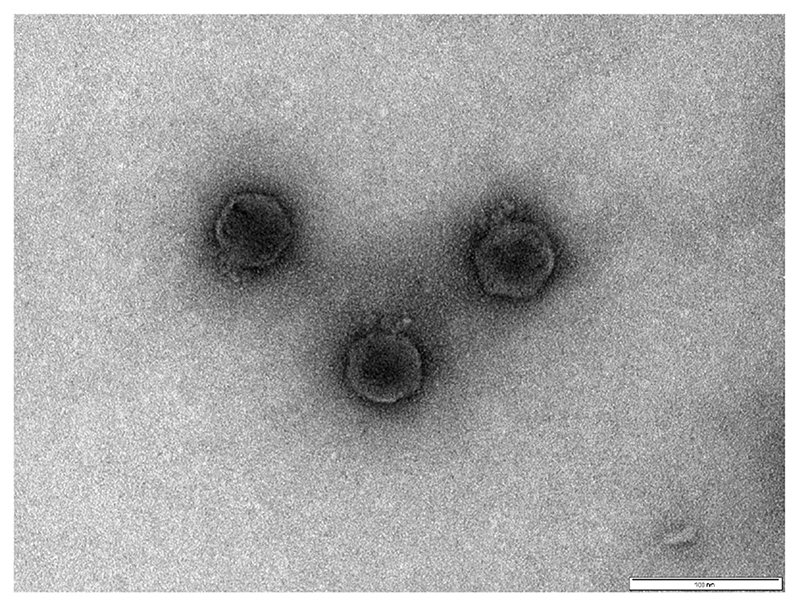

Transmission Electron Microscopy

High-titer phage lysates were purified by means of ultracentrifugation using a cesium chloride gradient [20]. A 3-μL sample of cesium chloride–purified phage was applied to a hydrophilic (glow-discharged) carbon and Pioloform-coated 300 square mesh copper grid (Agar Scientific). After adsorption (2 minutes), excess sample was removed with filter paper. The grid was rinsed twice with 5 μL of distilled deionized water, and the excess was removed before staining with 1% uranyl acetate. Once dry, the grids were observed on a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. Digital images were recorded using a SIS Megaview III digital camera with iTEM software (version 5.1).

Infant Rabbit Trials

All experimental protocols involving animals were approved by the local Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (under UK Home Office project license 70–7495) and performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) and EU directive 2010/63/EU. The infant rabbit cholera model was used to test the effectiveness of phage treatment [21]. Time-mated New Zealand White rabbits were obtained from Harlan Laboratories. After parturition, litters were housed as a group with the lactating doe for the duration of the study.

Two hours before infection with bacteria, 2-day-old rabbits were pretreated intraperitoneally with ranitidine (5 mg/kg body weight; GlaxoSmithKline). Oral inoculations of bacteria (0.5-mL volume) and/or phage (1-mL volume) were delivered using separate 5F catheters (Arrow International). The bacterial inoculum was prepared from stationary-phase cultures of pathogenic V. cholerae O1 (Classical biotype) 1051 SmR (from the National Institute of Cholera & Enteric Diseases, Kolkata, India). These cultures were resuspended in a sodium bicarbonate solution (2.5 g in 100 mL; pH 9) with a final concentration of approximately 5 × 108 CFUs per animal. Phage Phi_1 was administered either 6 hours before or 6 hours after bacterial challenge for prophylaxis and treatment, respectively (Table 1). Phage kinetics in the intestinal tract were studied by dosing rabbits with phage only and collecting samples for analyses at time points corresponding to 24-hour postbacterial infection (ie, at 18 hours to mimic treatment and 30 hours to mimic prophylaxis).

Table 1. Litter Size, Bacterial and Phage Dose, and Treatment Inoculation Schedule of Rabbit Experiments.

| Group | Animals, No. | Vibrio cholerae Inoculum, CFUs per Animal | Phage Inoculum, PFUs per Animal | Treatment Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||

| 1 | 6 | 7 × 108 | ... | ... |

| 2 | 5 | 2 × 108 | ... | |

| 3 | 7 | 6 × 108 | ... | |

| Therapeutic | ||||

| 1 | 10 | 1 × 109 | 1 × 109 | At 6–8 h after bacterial infection |

| 2 | 6 | 4 × 108 | 1 × 109 | |

| 3 | 4 | 1 × 109 | 1 × 109 | |

| Prophylactic | ||||

| 1 | 10 | 5 × 108 | 1 × 109 | At 6 h before bacterial infection |

| 2 | 6 | 5 × 108 | 1 × 109 | |

| 3 | 6 | 8 × 108 | 1 × 109 | |

| Therapeutic control | 8 | ... | 1 × 109 | At 6–8 h after bacterial infection |

| Prophylactic control | 6 | ... | 1 × 109 | At 6 h before bacterial infection |

Abbreviations: CFUs, colony-forming units; PFUs, plaque-forming units.

Diarrhea was scored using the following scale: none (no signs of fecal contamination or wetness on their ventral surfaces; on dissection, the colon contained digesta that appeared normal [dark green, hard, and formed)]), mild (soft yellow stools and/or limited areas of wetness on the rabbit’s fur; on dissection, digesta was missing from the colon or appeared yellow, soft, and unformed; some fluid accumulation in the cecum), and severe (extensive areas of wetness on their tails and ventral surfaces; on dissection, no digesta was found in the colon and the cecum and small intestine contained large quantities of clear fluid). Control and treatment group litters were housed separately to avoid cross-contamination, and ≥3 litters were used for each treatment strategy.

Animals were anesthetized 24 hours after infection using inhalation isoflurane (Isofol) and euthanized with intracardiac potassium chloride (15% wt/vol; MercuryPharma) at 2.5 mL/100 g body weight. Tissue segments (1 cm) were collected from the upper, middle, and lower portions of the small intestine, and cecal fluid was collected using gravity. The tissue samples were mechanically homogenized between sterile glass slides in 2 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Cecal fluid accumulation ratios were calculated as reported elsewhere [21]. When no cecal fluid was collected, cecal content was used instead to report numbers of bacteria. For bacterial enumeration, samples were decimally diluted and triplicate 10-μL aliquots spotted onto Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) containing streptomycin (200 μg/mL). In addition, 100 μL of the original sample, and in some instances, a 5-fold concentration of this volume, was spread onto the same medium to enable lower numbers of cells to be detected. Phage enumeration was performed by spotting 10-μL volumes of filtered (0.45-μm syringe filters) intestinal content onto lawns of the host strain. All plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours before examination for colonies or plaques.

Phage Resistance

Presumptive V. cholerae isolates recovered from phage-treated and control animal groups were confirmed by means of polymerase chain reaction [22] and streaked on both LB agar plates, with and without supplementation with Phi_1 (1 × 109 PFUs/ mL). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours before examination for colonies.

Statistical Analysis

Rabbit disease scores and cecal fluid accumulation ratios were analyzed using the Fisher exact test and 1-way analysis of variance, respectively. All bacterial and phage count data were log10 transformed before statistical analysis. Bacterial count data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test with the Dunn post hoc multiple-comparison test (GraphPad Prism; version 5.02). Differences in phage count data were analyzed using the 2-sam-ple Mann Whitney U test (using Minitab, version 17.2.1).

Results

Phage Isolation, Morphological Characterization, and Selection for Use as a Therapeutic

Seven phages were isolated from samples of lake water collected from China. Another 5 phages were obtained from existing collections. The morphological characteristics of each phage were used to determine a provisional taxonomic classification (Table 2). The host range and burst size of each phage were determined using a collection of 89 V. cholerae O1, O139, and non-O1/O139 strains (Supplementary Table 1) to identify candidates best suited for therapeutic application. The 3 Myoviridae phages (Phi_2, Phi_24 and Phi_X29) exhibited much narrower host ranges (1.1%–4.4%) than Podoviridae or Siphoviridae phages (Table 1). The different phage families did not cluster according to latent period or burst size.

Table 2. Bacteriophage Source and Characterization Including Host Range and One-Step Growth Curve.

| Phage Full Name | Short Name | Phage Source | Family | Head Diameter, Mean (SE), nma | Tail Length, Mean (SE), nma | Host Range, % | Latent Period, Mean (SE), mina | Burst Size, Mean (SE), PFUsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vB_VchoP_QH | Phi_QH | Qing He river (Beijing) | Podoviridae | 51 (0.1) | 12 (0.0) | 84.6 | 12 (4.0) | 92 (9) |

| vB_VchoP_CJY | Phi_CJY | Cui Jia Yao river (Beijing) | Podoviridae | 54 (0.1) | 10 (0.0) | 16.5 | 13 (4.3) | 182 (62) |

| vB_VchoP_H1 | Phi_H1 | Fu Jia Wan lake (Hubei) | Podoviridae | 56 (0.1) | 11 (0.0) | 37.3 | 6 (2.3) | 89 (32) |

| vB_VchoP_H2 | Phi_H2 | Ye Zhi Hu lake (Hubei) | Podoviridae | 57 (0.1) | 12 (0.0) | 18.7 | 15 (1.6) | 63 (13) |

| vB_VchoP_H3 | Phi_H3 | Nan Hu lake (Hubei) | Podoviridae | 55 (0.1) | 12 (0.0) | 70.3 | 7 (3.5) | 126 (18) |

| vB_VchoP_J2 | Phi_J2 | Yudai He river (Jiangxi) | Podoviridae | 54 (0.1) | 12 (0.0) | 16.5 | 5 (0.6) | 34 (13) |

| vB_VchoP_J3 | Phi_J3 | Yudai He river (Jiangxi) | Podoviridae | 52 (0.1) | 11 (0.0) | 76.9 | 14 (1.5) | 56 (17) |

| vB_VchoP_1 | Phi_1 | PHE | Podoviridae | 34 (0.2) | 13 (0.1) | 67.0 | 12 (0.0) | 43 (5) |

| vB_VchoM_2 | Phi_2 | PHE | Myoviridae | 53 (0.2) | 118 (0.4) | 4.4 | 14 (1.6) | 6 (1) |

| vB_VchoS_3 | Phi_3 | PHE | Siphoviridae | 75 (0.1) | 156 (0.2) | 62.6 | 13 (4.1) | 54 (26) |

| vB_VchoM_24 | Phi_24 | HER | Myoviridae | 64 (0.1) | 69 (0.1) | 1.1 | 4 (0.0) | 87 (26) |

| vB VchoM X29 | Phi_X29 | HER | Myoviridae | 64 (0.1) | 95 (0.3) | 2.2 | 16 (0.0) | 77 (16) |

Abbreviations: HER, Felix d’Herelle Reference Centre for Bacterial Viruses; PFUs, plaque-forming units; PHE, Public Health England; SE, standard error.

Mean of 3 independent measurements.

In addition to exhibiting a broad host range and large burst size, phage therapy candidates should not possess genes associated with virulence or lysogeny. Therefore, we sequenced the phage and examined their genomes for proteins of known function. The GenBank accession numbers for all phage genomes are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Sequencing revealed that none of the phage genomes contained known virulence genes. However, all of the phages, except Phi_1 and Phi_3, contained integrase sequences, suggesting that they may be temperate phages and unsuitable for therapeutic applications. Given that Phi_1 exhibited a slightly broader host range than Phi_3, we focused our efforts on Phi_1 (an electron micrograph of Phi_1 presented in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Electron micrograph of Podoviridae phage Phi_1.

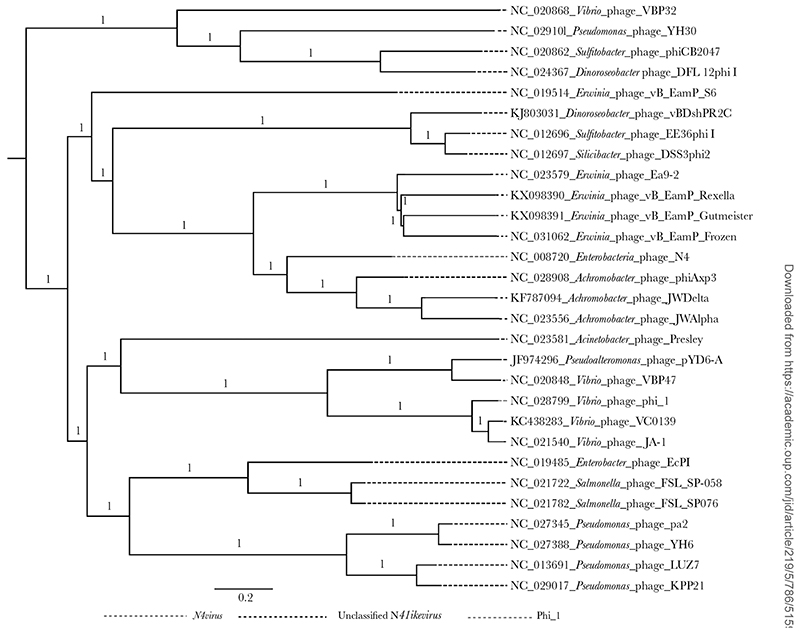

The Phi_1 genome is 66.7 kb and contains 110 genes (Supplementary Table 3). Among these, 12 were listed as early or middle genes associated with metabolism and replication, 6 could be grouped into the late genes related to head morphogenesis and host cell lysis, and the remaining 92 genes encoded hypothetical proteins. Nucleotide BLAST analysis revealed that phage Phi_1 was most closely related to 2 N4like viruses, Vibrio phages JA1 (GenBank NC_021540.1) and VCO139 (GenBank KC438283.1), with 97% pairwise identity and similar GC content (34.5% vs 34.6%). No tRNA sequences were detected in the Phi_1 genome in contrast to a single tRNA in each of JA1 and VCO139. To further resolve the taxonomic placement of Phi_1, phylogenetic analysis was performed comparing the genome sequence of Phi_1 with the available published genome sequences of phage in the genus N4virus. Phylogeny showed that Phi_1 grouped with VCO139 and JA-1, with the only classified species of the genus N4virus, Escherichia phage N4, located in a distant clade (Figure 2). Thus, we have identified a previously undescribed Podoviridae N4-like virus with characteristics that are favorable for phage therapy including being effective against a range of clinical V. cholerae strains grown under laboratory conditions.

Figure 2.

The maximum likelihood phylogenetic comparison of vB_VchoP_1 with the published genome sequences of phage species from the genus N4virus. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the generalized time-reversible model with FastTree software and the phylogeny was visualized using FigTree software.

Effectiveness of Phi_1 to Control Experimental Cholera in Infant Rabbits

To assess whether phage Phi_1 could be used to control experimental cholera, therapeutic and prophylactic studies were performed using the infant rabbit cholera model [23]. For the therapeutic trials, groups of infant rabbits were orally infected with approximately 8 × 108 CFUs of SmR V. cholerae O1 strain 1051 and treated with phage (109 PFUs) 6 hours after infection. Control animals receiving only V. cholerae showed signs of disease as reported previously for rabbits infected with V. cholerae O1 [23]. Signs included the production of watery diarrhea, loose stool, and/or notable cecal fluid accumulation occurring in the majority of infected animals (11 of 17) (Table 3). In marked contrast, none of the phage-treated animals (0 of 19) showed signs of disease 24 hours after infection. Cecal fluid accumulation ratios were 6-fold higher in diseased control animals than in phage-treated animals (mean [standard deviation], 0.39 [0.08] vs 0.06 [0.01]; P < .001), consistent with the lack of disease.

Table 3. Disease Status and Fluid Accumulation Ratios in Infant Rabbits Treated With Phage Phi_1 Before and After Infection with Vibrio cholerae 01.

| Phage Administrationa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Status | No Treatment | Therapeutic | Prophylactic |

| Disease, % | 69b | 0b | 0b |

| Disease score, No. of rabbitsc | |||

| Severe | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| None | 6 | 19 | 22 |

| Total | 17 | 19 | 22 |

| Fluid accumulation ratio, mean (SD)d | 0.39 (0.31) | 0.06 (0.05)d | 0.04 (0.02)d |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Phage Phi_1 was orally administered 6 hours before (prophylactic) or 6 hours after (therapeutic) the bacteria.

The Fisher exact test was used to compare the proportion of animals with disease symptoms in groups treated with phage Phi_1 therapeutically or prophylactically, compared with untreated control animals (P < .001).

The disease scoring system is described in the text.

The fluid accumulation ratio is calculated as the ratio of the weight of the cecal fluid to the tissue for each animal.

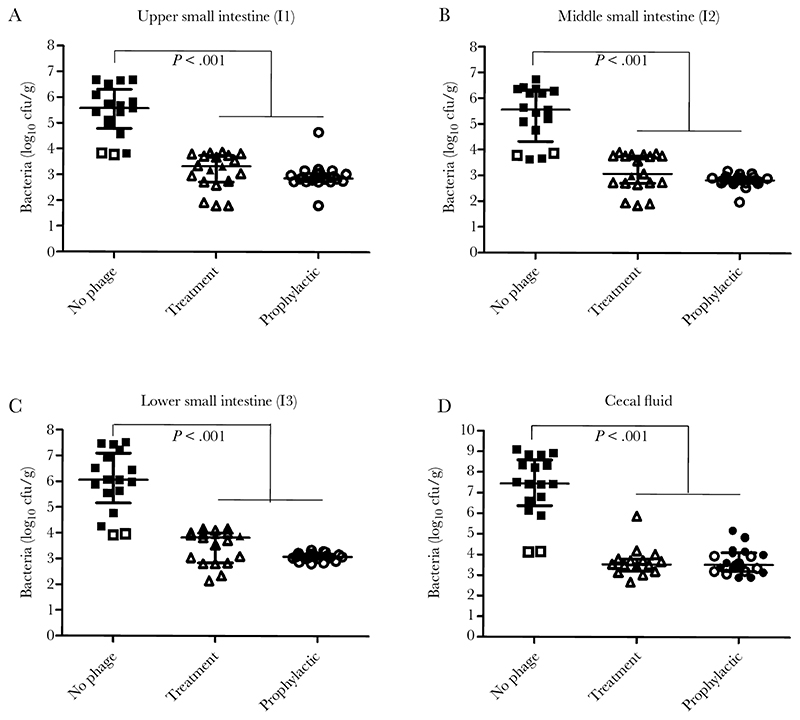

Furthermore, phage treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the number of V. cholerae recovered from the intestine compared with the control group, with no detectable colonies recovered in more than half of the animals (Figure 2A–2C). Median reductions of 2–4 log10 CFUs/g V. cholerae were recorded in different intestinal compartments, including in cecal content (Figure 3D). This, together with the low volumes of fluid evident in the intestine, would lead to a marked reduction in the number of organisms shed from the host.

Figure 3.

Efficacy of phage Phi-1 in reducing Vibrio cholerae O1 colonization of the infant rabbit intestine. Rabbits were administered 1 × 109 plaque-forming units (PFUs) phage Phi-1 orally, 6 hours before or after infection with 5-8 × 108 colony-forming units (CFUs) V. cholerae O1. Viable V. cholerae were recovered from the upper (A), middle (B), and distal (C) portions of the small intestine and in cecal fluid (D) 24 hours after bacterial infection, following tissue homogenization and plating on selective media. Symbols represent individual animals, with open symbols representing samples where the number of recoverable colonies was below the limit of detection. The number of animals in each group was 17, 22, and 19 respectively, and each group was derived from 3 independent litters. Bars represent the median and interquartile range. Data were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn post hoc multiple-comparisons test.

We also assessed the ability of Phi_1 to be used prophylactically. In these studies, infant rabbits were administered 109 PFUs phage 6 hours before infection with approximately 5 × 108 CFUs per animal V. cholerae. Reflecting the therapeutic trials, phage-treated animals showed no symptoms of disease and exhibited significant reductions in recoverable V. cholerae and intestinal fluid compared with untreated control animals (Table 2 and Figure 2A–2D). Overall, these data indicate that Phi_1 is effective at killing V. cholerae in several intestinal compartments both before and after challenge with virulent V. cholerae.

Amplification of Phage Phi_1 in the Intestine, and the Development of Phage Resistance

When administered 6 hours after V. cholerae infection, approximately 106–107 PFUs/g of phage were recovered in the intestine of the animals, approximately 100-fold higher than in animals given phage only (range 104–106 PFUs/g) (Table 4). Slightly lower levels of phage were recovered during the prophylaxis experiments, most likely reflecting the increased time for transit through the intestine before bacterial inoculation (18 and 30 hours, respectively). However, in both cases, significant amplification of phage was recorded in most intestinal compartments, leading to a multiplicity of infection throughout the intestinal tract of about 1–2 phages per V. cholerae cell (Table 4). Finally, these data suggest that significant numbers of phage (104–105 PFUs/g) were recoverable from the intestine up to 30 hours after administration, even in the absence of V. cholerae.

Table 4. Bacteriophage Concentration, Production, and MOI During Prophylactic and Therapeutic Treatments.

| Treatment Phage Concentration, Mean (SE), Log10 PFUs/ga | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Schedule | Prophylactic Schedule | |||||||

| Sample | Control (n = 8)b | Treatment (n = 18) | Phage Production | MOI | Control (n = 6)c | Treatment (n = 22) | Phage Production | MOI |

| Small intestine | ||||||||

| Upper | 4.2 (1.8) | 6.4 (0.3)*** | 2.2 | 1.9 | 4.7 (0.4) | 5.1 (0.2) | 0.4 | 1.8 |

| Middle | 5.3 (0.9) | 6.6 (0.2)** | 1.3 | 2.0 | 4.6 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.1) | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| Lower | 4.8 (0.8) | 6.8 (0.3)*** | 2.0 | 1.7 | 5.0 (0.6) | 5.7 (0.2)* | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| Midcolon | 6.6 (0.5) | 76 (0.7)** | 1.0 | 2.0 | 5.7 (0.6) | 6.7 (0.2)** | 0.9 | 2.1 |

| Cecal fluid | 6.1 (2.5) | 7.8 (0.3)* | 1.7 | 2.3 | 5.4 (0.7) | 71 (0.1)*** | 1.7 | 2.0 |

Abbreviations: MOI, multiplicity of infection; PFUs, plaque-forming units; SE, standard error.

Phage Phi_1 was orally administered following the therapeutic or prophylactic schedule. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare values between groups.

Control animals in this group were given only Vibrio cholerae 1051.

Control animals in this group were given only phage Phi_1.

P < .05 (Mann-Whitney U test).

P < .01 (Mann-Whitney U test).

P < .001 (Mann-Whitney U test).

The V. cholerae colonies recovered from all the in vivo experiments were tested for their susceptibility to phage Phi_1 to determine levels of phage-resistance. Somewhat surprisingly, none of the colonies grew in LB medium supplemented with 109 PFUs of phage Phi_1, indicating that they remained sensitive to the phage. Moreover, attempts to generate phage-resistant mutants in vitro using plate-based methods were not successful, suggesting that the as-yet-uncharacterized phage Phi_1 receptor is important for V. cholerae viability under these conditions.

Discussion

In the current study, we show for the first time that oral administration of a single Podoviridae phage could prevent clinical cholera symptoms in infant rabbits without the development of phage resistance. Our findings provide further evidence that phage can both reduce the severity of disease and limit spread of the organism to the environment. Given the well-documented challenges associated with the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, phage may yet provide a viable alternative to antibiotics.

The strain of V. cholerae used has been shown experimentally by this group to result in cholera using the infant rabbit model [21], with fluid accumulation in the small intestine, perianal staining, and dehydration resulting in death if humane termination is not carried out. The infant rabbit model combines sensitivity with a greater convenience than other whole-animal models, such as the ligated intestinal loop model in adult rabbits [24] or mouse models [21].

Given that animals receiving only bacteriophage had detectable levels of phage in their intestines for ≥24 hours; prophylaxis experiments with a longer interval between phage and bacteria administration would be worth assessing. However, because the rabbits are in an enclosed environment, environmental contamination with phage may occur with the ingestion and reingestion of phage from the mother’s skin or the bedding.

Yen and colleagues [25] published a study describing the prophylactic use of a 3-phage (ICP) cocktail to treat cholera. They recorded a marked reduction in disease and V. cholerae recovered from rabbits given the phage cocktail. However, in contrast to the present study, they also recovered phage-resistant mutants. Susceptibility profiling of the in vivo–passaged V. cholerae against the individual phage present in the ICP cocktail revealed that resistance differed depending on the animal host as well as over time. The phage used in the study by Yen et al were all members of the Podoviridae, previously identified as containing phage that make “better” in vivo therapeutic agents [26].

Rational and systematic evaluation of phage characteristics according to morphology, genomics, and a number of cultural phenotypes, including latent period, burst size, and host range, seems to be critical in the selection of phage as therapeutic agents. Latent period, burst size, and the presence of a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase have all been found to correlate with in vivo efficacy in controlling experimental Escherichia coli infections [26]. Both phage Phi_1 and ICP3 encode a specific RNA polymerase that could improve their effectivity in vivo. However, it could also be that phage Phi_1 uses a crucial receptor for V. cholerae survival in the intestinal tract, such as the O1 lipopolysaccharide antigen. It is well known that phase-variable mutants of the O1 receptor are protected from phage infection but become attenuated [27]. Selecting phages that target surface virulence determinants can be an effective approach, because phage-resistant mutants are often attenuated.

In one study, using E. coli phage targeting the K1 capsule resulted in the recovery of acapsular but attenuated mutants [8]. The potential development of resistance is a concern if phages are applied in the field, because oral administration to patients may result in extensive shedding of bacteria and phage in the environment, potentially resulting in recirculation of phage-resistant mutants. In some circumstances, this could be avoided by limiting phage administration to patients in clinics and composting the evacuated feces. Alternatively, the impact of phage recirculation could be minimized by using different phage preparations that target different receptors, or combinations of receptors, to limit the emergence of resistant strains.

Two previous studies of phage therapy to treat cholera in small groups of human patients found either little clinical effect [28], or the requirement for large phage doses (>1015 PFUs) [29]. However, the phages used were not well characterized, and some seemed to be temperate and ill suited for therapy. In addition, neither study neutralized stomach acid before phage administration, which may significantly affect the results. Both studies used phage cocktails that, if combined carefully, may offer some protection against the emergence of resistant mutants. However, the performance of phage cocktails may be no better than individual phages [30], and could be worse. The use of cocktails requires a balance to be struck between the practical limitations of preparing lysates of many different phage, and the need to include sufficient phage to minimize the emergence of resistant mutants. Principally, this should be done through genomic and phenotypic analysis to combine compatible phages that target different receptors.

Characterization of the interaction of Phi_1 and its receptor(s) may provide some clues as to why phage-resistant mutants were not recovered. Prophylactic and therapeutic trials with Phi_1 need to be performed in human volunteers to determine if this treatment is viable. Should this prove successful, bacteriophage therapy could be deployed relatively easily to remote and underserved communities in developing countries owing to the ease and speed with which phage can be prepared, using basic laboratory equipment. Alternatively, preparations of phage can be made using lyophilization, spray drying, emulsification, and microencapsulation, which remain stable for years (recently reviewed in [31]). Phage therapy has significant potential to save hundreds or thousands of lives during outbreaks of cholera that follow natural and man-made disasters, an aim strongly worth pursuing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. S.’s team at China Agricultural University for their excellent support during the isolation of phage in China. B. L. S., B. W., and Neil Williams are gratefully acknowledged for sharing their collection of V. cholerae isolates.

Footnotes

Financial support.

This work was supported by University of Nottingham internal funds (Global Food Security Initiative), the University of Nottingham Advanced Data Analysis Centre, and the UK-India Education and Research Initiative (grant UKIERI-DST-2012/13–043 to R. J. A.).

Potential conflicts of interest.

All authors: no reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Hu D, Liu B, Feng L, et al. Origins of the current seventh cholera pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E7730-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608732113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimoto JD, Koepke AA, Kenah EE, et al. Household transmission of Vibrio cholerae n Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitaoka M, Miyata ST, Unterweger D, Pukatzki S. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms ofVibrio cholerae . J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:397–407. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.023051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czaplewski L, Bax R, Clokie M, et al. Alternatives to antibi-otics—a pipeline portfolio review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:239–51. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith HW, Huggins MB. Effectiveness of phages in treating experimentalEscherichia colidiarrhoea in calves, piglets and lambs. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2659–75. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-8-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrow P, Lovell M, Berchieri A., Jr Use of lytic bacteriophage for control of experimental Escherichia coli septicemia and meningitis in chickens and calves. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:294–8. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.3.294-298.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith HW, Huggins MB. Successful treatment of experimental Escherichia coli infections in mice using phage: its general superiority over antibiotics. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:307–18. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-2-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clokie MRJ, Kropinski AM. Bacteriophages : methods and protocols. 1st. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning a laboratory manual. 2nd. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atterbury RJ, Van Bergen MA, Ortiz F, et al. Bacteriophage therapy to reduce salmonella colonization of broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4543–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00049-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi C, Kuatsjah E, Wu E, Yuan S. The effect of cell size on the burst size of T4 bacteriophage infections ofEscherichia coliB23. J Exp Microbiol Immunol. 2010;14:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–77. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:222–230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schattner P, Brooks AN, Lowe TM. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W686-9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laslett D, Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:11–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1641–50. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooton SP, Timms AR, Rowsell J, Wilson R, Connerton IF. SalmonellaTyphimurium-specific bacteriophage ΦSH19 and the origins of species specificity in the Vi01-like phage family. Virol J. 2011;8:498. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie JM, Rui H, Bronson RT, Waldor MK. Back to the future: studying cholera pathogenesis using infant rabbits. MBio. 2010;1:e00047-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nhung PH, Ohkusu K, Miyasaka J, Sun XS, Ezaki T. Rapid and specific identification of 5 human pathogenic Vibrio species by multiplex polymerase chain reaction targeted to dnaJ gene. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:271–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie JM, Rui H, Bronson RT, Waldor MK. Back to the future: studying cholera pathogenesis using infant rabbits. MBio. 2010:1. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De SN, Chatterje DN. An experimental study of the mechanism of action of Vibrio cholerae on the intestinal mucous membrane. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1953;66:559–62. doi: 10.1002/path.1700660228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen M, Cairns LS, Camilli A. A cocktail of three virulent bacteriophages prevents Vibrio cholerae infection in animal models. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14187. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baig A, Colom J, Barrow P, et al. Biology and genomics of an historic therapeutic Escherichia coli bacteriophage collection. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1652. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seed KD, Faruque SM, Mekalanos JJ, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Camilli A. Phase variable O antigen biosynthetic genes control expression of the major protective antigen and bacteriophage receptor in Vibrio cholerae O1. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002917. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcuk LM, Nikiforov VN, Scerbak JF, et al. Clinical studies of the use of bacteriophage in the treatment of cholera. Bull World Health Organ. 1971;45:77–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monsur KA, Rahman MA, Huq F, Islam MN, Northrup RS, Hirschhorn N. Effect of massive doses of bacteriophage on excretion of vibrios, duration of diarrhoea and output of stools in acute cases of cholera. Bull World Health Organ. 1970;42:723–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaiswal A, Koley H, Ghosh A, Palit A, Sarkar B. Efficacy of cocktail phage therapy in treating Vibrio cholerae infection in rabbit model. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:152–6. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik DJ, Sokolov IJ, Vinner GK, et al. Formulation, stabilisation and encapsulation of bacteriophage for phage therapy. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;249:100–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.