Summary

Severe infections are a major stress on haematopoiesis, where the consequences for haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have only recently started to emerge. HSC function critically depends on the integrity of complex bone marrow (BM) niches, however what role the BM microenvironment plays in mediating the effects of infection on HSCs remains an open question. Here, using a murine model of malaria and combining single cell RNA sequencing, mathematical modelling, transplantation assays and intravital microscopy, we show that haematopoiesis is reprogrammed upon infection, whereby the HSC compartment turns over significantly faster than in steady-state and HSC function is drastically affected. Interferon is found to affect both haematopoietic and mesenchymal BM cells and we specifically identify a dramatic loss of osteoblasts and alterations in endothelial cell function. Osteo-active parathyroid hormone treatment abolishes infection-triggered HSC proliferation and, coupled with Reactive Oxygen Species quenching, enables partial rescuing of HSC function.

Introduction

Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside within the bone marrow (BM) where they interact with multiple stroma and haematopoietic cell types. These cells form complex niches that regulate HSC function by maintaining quiescence and supporting their self-renewal1. Once outside the niche, HSC progeny differentiate into highly proliferative progenitor cells, which further develop into erythroid, megakaryocyte, myeloid and lymphoid lineages.

Infection is a natural stressor of the haematopoietic system, whereby haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) modify their progeny output to promptly cope with the increased demand for mature cells2–5. Infectious challenges result in hallmark HSPC responses, including expansion of the early progenitor compartment (Lineage-c-Kit+Sca-1+, or LKS cells) and alterations in HSC cycling properties, long-term function and migration patterns6–9. It is widely accepted that increased proliferation leads to loss of HSC function, but it is unclear whether during infections other factors may contribute to HSC decline. These phenomena happen within the BM microenvironment, yet little is known about the role of HSC niche components in regulating the observed changes in HSPC dynamics. With severe infections on the rise worldwide, it is important to devise therapeutic strategies that preserve HSC function, including through targeting the niche.

Malaria is a life-threatening disease with an estimated 216 million new cases in 2016 resulting in approximately 445,000 deaths10. Plasmodium infects and destroys red blood cells, has significant impacts on erythropoiesis11–14 and haematopoietic/immune function of Malaria survivors is compromised both short- and long-term15,16 due to alterations in myeloid lineage cells15,17. It is likely that these effects originate from changes at the earliest stages of haematopoiesis, including the HSC compartment. So far, however, little work directly addresses the effect of Plasmodium infection on primitive HSPCs. Using the murine experimental model Plasmodium berghei, we previously demonstrated that multiple components of the haematopoietic tree simultaneously respond with a substantial increase in proliferation during advanced blood stage infection9. This raised questions about what cell-intrinsic or -extrinsic mechanisms mediate the observed haematopoietic dynamics, how this affects HSC long-term function and whether infection-induced changes to the BM microenvironment contribute to the phenotypes observed.

Here, we combine molecular, phenotypic, functional and intravital microscopy (IVM) analyses to study the haematopoietic and BM microenvironment responses over the course of infection, investigate causal links between the two, and test whether niche manipulation is a viable approach to rescue HSC function.

Results

P. berghei infection leads to loss of HSC transcriptional identity and function

Mice infected by bites of mosquitos carrying P. berghei sporozoites are an excellent experimental model to study the effect of severe malaria on haematopoiesis9. Despite variability in parasitaemia, flow cytometry analysis of BM from control and infected mice highlighted a dramatic increase in the number of LKS cells by day 7 post-sporozoite infection (psi) (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. P. berghei infection alters HSC transcriptional identity and function.

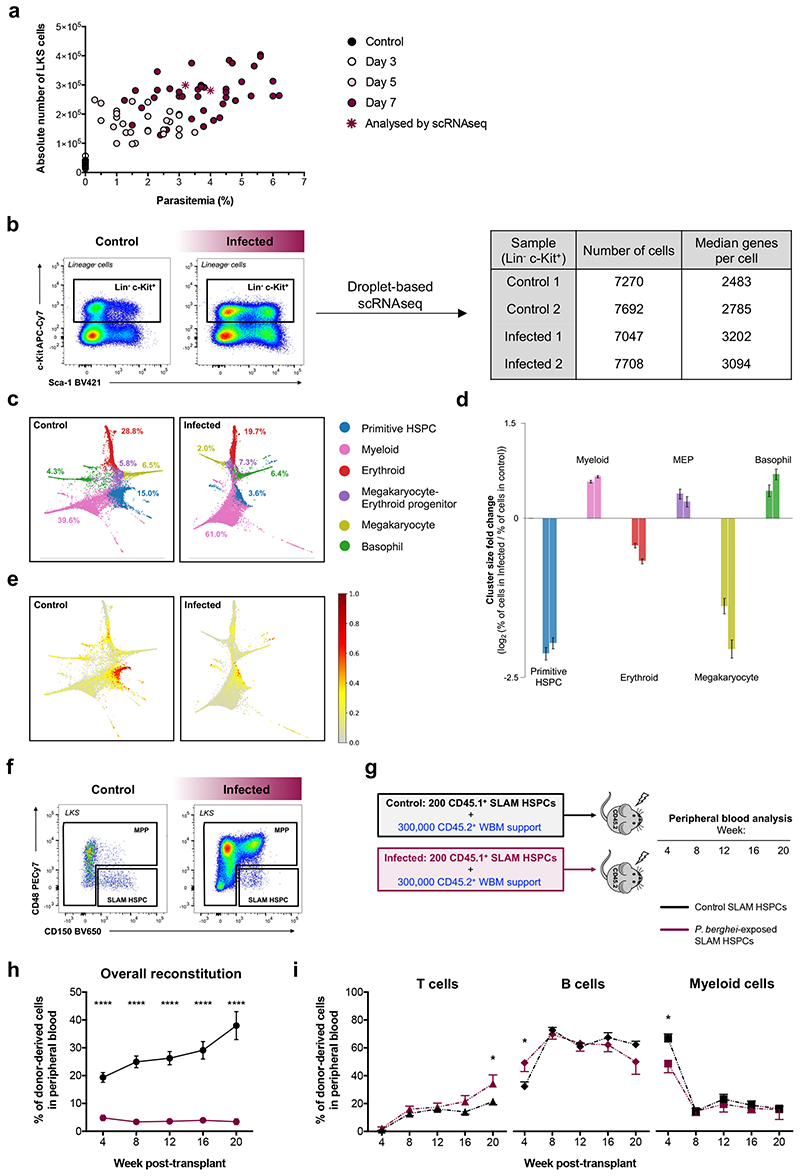

(a) Parasitaemia in peripheral blood over the course of infection and absolute number of LKS cells. Each circle represents one mouse and stars indicate mice analysed by scRNAseq (control n = 10 control, day 3 n = 20, day 5 n = 27 and day 7 n = 42). Data pooled from >3 independent infections.

(b) Gating strategy used to isolate Lineage-c-Kit+ cells for droplet-based scRNAseq at day 7 psi. Boxes indicate the number of cells that passed quality control and the median number of genes detected per cell per sample.

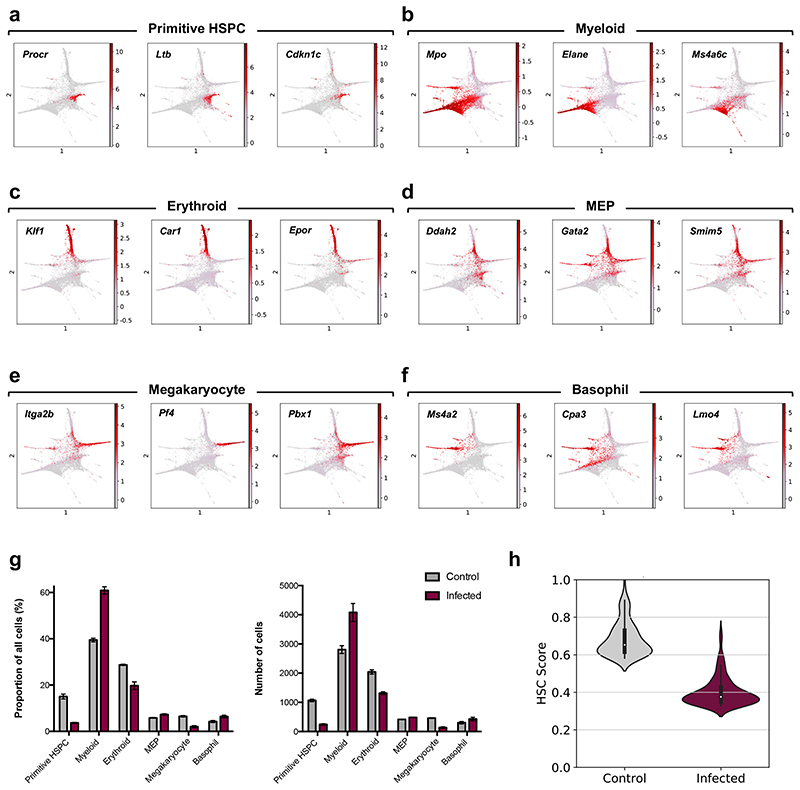

(c) Cluster identity of cells from control and infected mice. Using Louvain clustering on the k-nearest neighbour graph, control cells were organised into 6 populations, specified in the key. Infected cells were mapped to their corresponding control cluster. The proportions of each cluster in both conditions are shown.

(d) Log2 fold change (positive values: increase, negative values: decrease) of the percentage of infected cells mapped to each cluster divided by the percentage of control cells in the same cluster. Left-hand and right-hand bars indicate fold changes for samples from two separate infected mice. Error bars represent one standard deviation of the results as calculated through binomial bootstrapping using the observed abundance changes as the prior distribution.

(e) HSC-score values plotted on the force-directed graph embedding for all cells from control and infected mice.

(f) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the gating strategy for MPP and SLAM HSPC populations in control and infected mice at day 7 psi.

(g) Schematic of the transplantation assay presented in (h).

(h) Overall peripheral blood reconstitution and (i) multilineage output of transplanted SLAM HSPCs from control and infected donors into lethally irradiated recipients, assessed by flow cytometry. Data pooled from recipients of 2 independent donor groups from 2 infections. n = 12 recipients per group. Data presented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. P values determined by two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni corrections (h) or unpaired two tailed Student’s t-tests (i).

To obtain a broad and unbiased understanding of the cellular and molecular changes taking place in HSPCs as a consequence of P. berghei infection, we performed single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) on Lineage-c-Kit+ cells from control and day 7 psi infected mice (Fig. 1b). Similar numbers of cells were analysed from two control and two infected animals with ‘average’ parasitaemia for the disease stage (Fig. 1a). Over 7000 cells passed quality control in all samples, and a median of over 2400 genes were detected per cell (Fig. 1b). We grouped control cells into clusters (Extended Data Fig. 1a-f) and mapped cells from infected animals against their corresponding control cluster. Force-directed graphs18 highlighting the various lineage branches (Fig. 1c) indicated that, in infected mice, early haematopoiesis was substantially rewired towards myeloid and basophil lineages, at the expense of primitive cells, erythroid and megakaryocyte lineages (Fig. 1d; Extended Data Fig. 1g). These data can be further explored on our interactive website. Next, we determined that machine-learning based HSC-scores19 were strikingly decreased for cells from infected mice (Fig. 1e; Extended Data Fig. 1h), raising questions about how P. berghei affects HSC function.

In order to perform functional analyses on relatively homogeneous cell populations whose properties are well understood at steady-state, we focused on the LKS CD150+CD48low/neg phenotypic cell population, which is enriched for HSCs, however, includes primitive multipotent progenitors (MPPs)20–23. Here, we label this phenotype ‘SLAM HSPC’, and collectively label the remaining cells within the LKS population ‘MPP’ (Fig. 1f; Extended data Fig. 2a,b). Transplantation of purified SLAM HSPCs from control and infected CD45.1 donor mice, together with limited numbers of CD45.2 whole bone marrow (WBM) support cells, into lethally irradiated CD45.2 recipients (Fig. 1g) indicated that cells from infected animals had drastically reduced engraftment ability (Fig. 1h), however their long-term multilineage potential was largely consistent with that of transplanted control SLAM HSPCs (Fig. 1i). Together with the scRNAseq, these data demonstrate a significant loss of HSC transcriptional identity and functionality upon infection, raising questions about what mechanisms trigger this extensive damage.

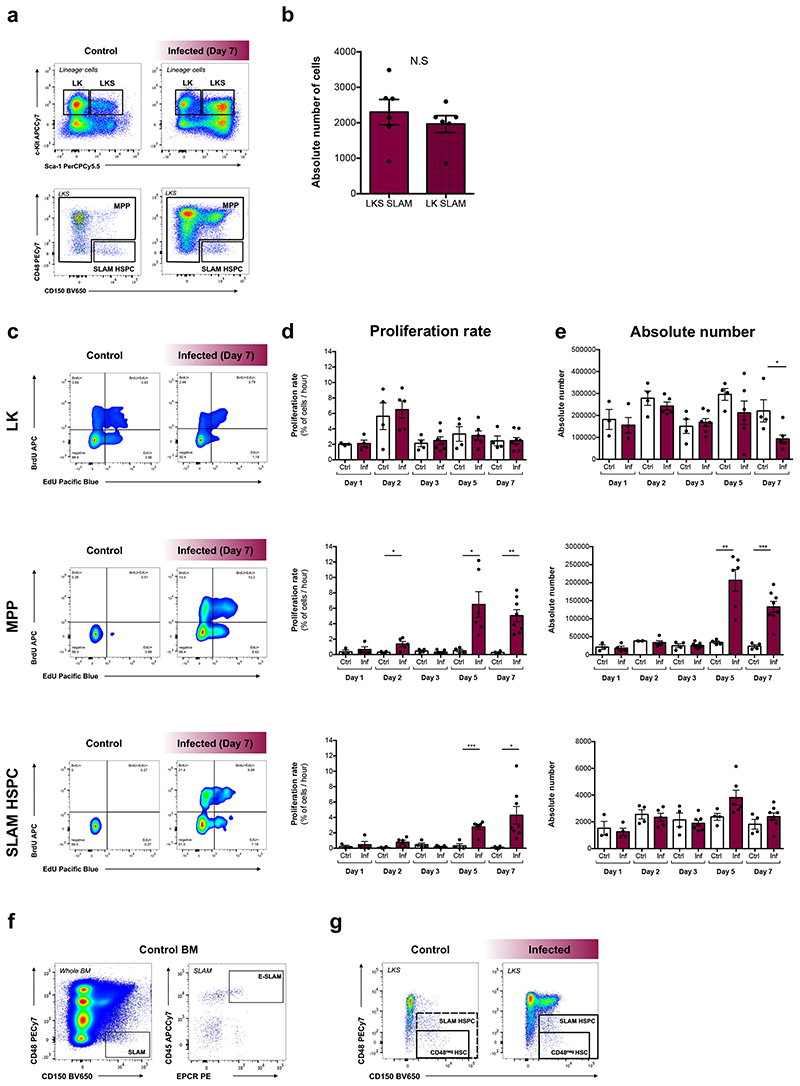

P. berghei infection affects the population dynamics of early HSPCs

To gain a quantitative understanding of HSPC dynamics as infection progresses we employed an established dual-pulse labelling method23. Consistent with previous observations9, the LK compartment had increased proliferation rate but reduced size by day 7 psi, whereas proliferation of both MPPs and SLAM HSPCs increased significantly by day 5 (Extended Data Fig. 2c-e; circles in Fig. 2a). Unlike MPPs, SLAM HSPC numbers remained constant throughout the infection (Extended Data Fig. 2e; circles in Fig. 2b), despite increased proliferation.

Fig. 2. P. berghei affects population dynamics of early HSPCs.

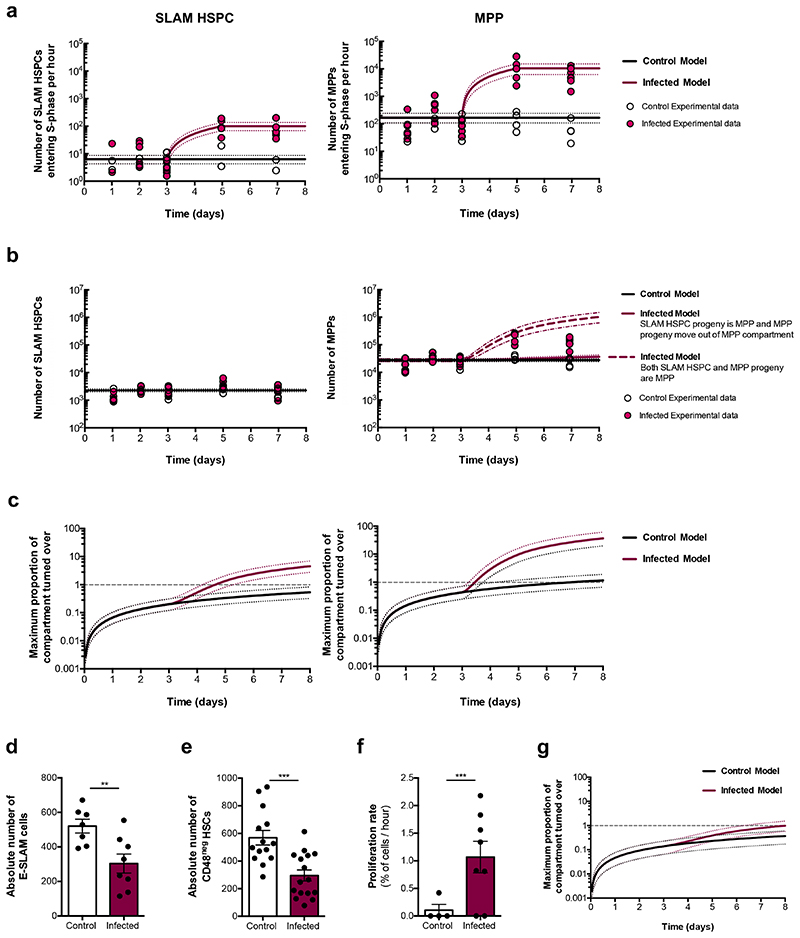

(a) Experimental data and mathematical model representing SLAM HSPC and MPP proliferation rates. In the control model, proliferation is constant, corresponding to the average of measurements from all mice up to day 3 psi. In the infected model, proliferation is constant with control until day 3, then linearly increases to the average of the data from infected mice at day 5 and day 7 psi.

(b) Experimental data and mathematical model of SLAM HSPC and MPP compartment sizes. SLAM HSPCs are modelled as a constant corresponding to the average data from all animals. For MPPs, the control model is a constant corresponding to the average of measurements from all control plus infected mice up to day 3 psi. In the first infected model (continuous maroon line), the number is constant with the control model until day 3, then increases corresponding to the additional SLAM HSPCs entering S-phase in the infected model, shown in (a). In the second infected model (dashed maroon line), the number is constant until day 3, then increases based on the sum of additional SLAM HSPCs and MPPs entering S-phase in the infected model, shown in (a).

(c) Modelling of the maximum proportion of SLAM HSPCs and MPPs turned over as a function of time in control and infected mice. Note: a log scale is used for the y-axis. Intersections with the grey dashed line visually represents when the entire compartment could have completed one turnover.

Dotted lines indicate 95% percentile bootstrap confidence intervals for each model (a-c). Absolute number of (d) E-SLAM cells (n = 7 control, 8 infected) and (e) CD48neg HSCs (n = 14 control, 16 infected) at day 7 psi.

(f) Proliferation rate of CD48neg HSCs at day 7 psi (n = 4 control, 7 infected).

(g) Modelling of the maximum proportion of CD48neg HSCs turned over as a function of time in control and infected mice.

Data pooled from up to 3 independent infections. Data presented as mean ± s.e.m (d - f). P values determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests.

To test the contribution of proliferation and differentiation to each compartment, we performed quantitative inference via a simple mathematical model based on the collected data (Fig. 2a,b; Supplementary Discussion). This demonstrated that SLAM HSPC contribution alone is not sufficient to account for the growth of the MPP population observed experimentally. This instead is consistent with MPP progeny remaining within the same compartment up to day 5, after which differentiation accelerates. Next, we assessed the effect of proliferation on SLAM HSPC and MPP cell compartments’ turnover, assuming that all cells within a compartment cycled sequentially. In control mice, the maximum number of SLAM HSPCs undergoing S-phase at least once within 8 days constituted less than the whole compartment (Fig. 2c). However, in infected mice, by day 5 psi the whole SLAM HSPC compartment could have already turned over once, and by day 8 psi it is possible that the whole SLAM HSPC population will have turned over approximately 5 times as a result of the faster proliferation rates. The MPP compartment could turnover once every 8 days in control mice, but this would increase up to 40 times during infection (Fig. 2c). These data demonstrate that P. berghei infection drastically increases HSPC turnover and, together with the transcriptomic analysis and transplantation assays, suggest a mechanism for the loss of functional SLAM HSPCs in response to severe infection.

Next, we deepened our flow cytometry analyses to focus on immunophenotypes highly enriched for the most functional HSCs, namely EPCR+ (E-SLAM) HSCs24 (Extended Data Fig. 2f) and LKS CD150+CD48neg HSCs (CD48neg HSCs)23 (Extended Data Fig. 2g). The size of each population significantly decreased in infected mice (Fig. 2d,e) and the proliferation rate of the surviving CD48neg HSCs increased substantially (Fig. 2f). However, our mathematical analysis indicated that by day 8 psi 85% of the CD48neg HSC compartment would have been replaced by completely new cells compared to 30% in control (Fig. 2g). These data highlighted that although P. berghei induces proliferation of more quiescent HSC subsets, it does not cause the entire compartment to turnover. Proliferation alone is therefore unlikely to cause the near complete loss of HSC function observed.

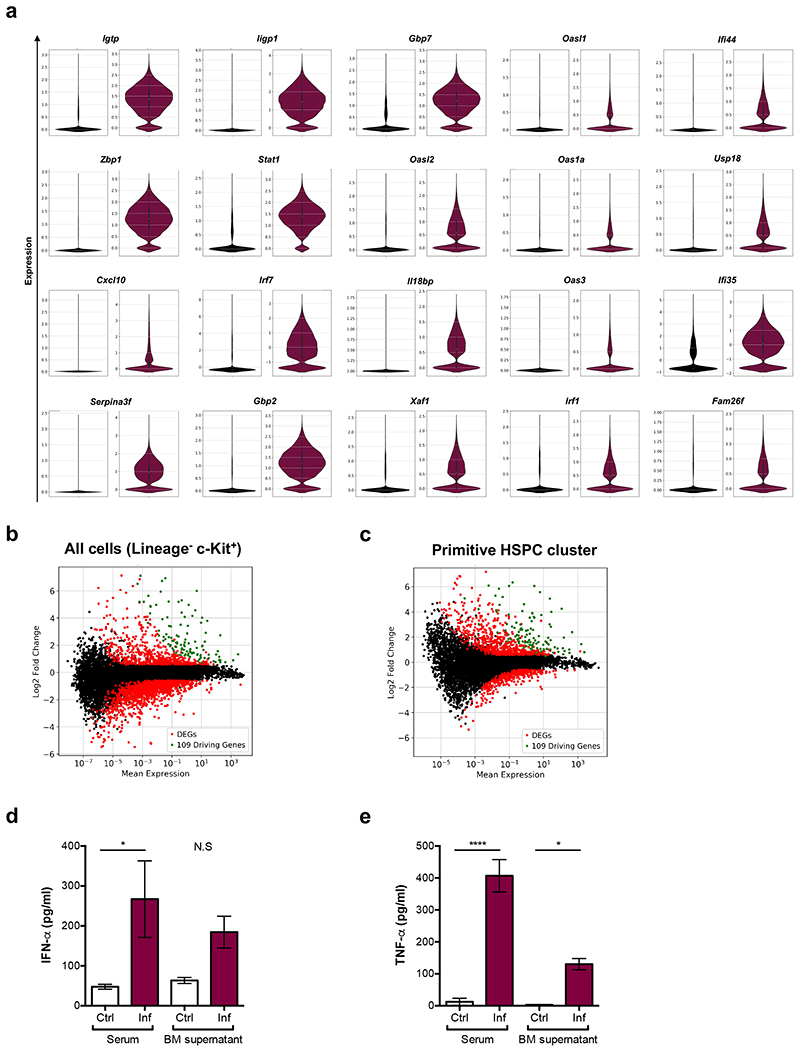

P. berghei-exposed HSPCs and BM stroma cells exhibit a strong interferon response

To identify molecular mechanisms driving HSC damage, we re-examined the scRNAseq dataset to determine differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between control and infected samples. Filtering for genes at least 4-fold upregulated in all clusters identified 20 initial ‘driving genes’ and the list grew to 109 when including DEGs whose expression correlated highly (Supplementary Table 1). SPRING analysis highlighted the role of these genes in separating HSPCs from healthy and infected animals (Fig. 3a). Most of the genes were related to IFN, and some specifically to IFN-gamma (IFN-γ) signalling (Fig. 3b,c and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Interestingly, when comparing DEGs in the overall HSPC population or in specific clusters it became apparent that the driving genes were indeed upregulated in all clusters (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c). Downregulated genes were more numerous and less shared between clusters, consistent with haematopoietic rewiring requiring the inhibition of programmes linked to several lineages and the initiation of a common transcriptional program. GO analysis of primitive HSPC cluster DEGs further highlighted the prominence of IFN-γ-mediated signalling pathways, together with cell cycle regulators, Type-I IFN and Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) signalling, and metabolism-related genes (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 2). To validate the role of cytokines, we measured IFN-γ, IFN-α and TNF-α levels. We detected a striking increase of IFN-γ in the serum and the BM supernatant of infected animals (Fig. 3e). IFN-α and TNF-α levels were also augmented (Extended Data Fig. 3d,e), albeit to a lesser extent than IFN-γ. This was consistent with IFN-γ being most widely associated with responses to Plasmodium infection in mice and humans25–28.

Fig. 3. P. berghei exposed HSPCs and BM stroma cells exhibit a strong interferon response.

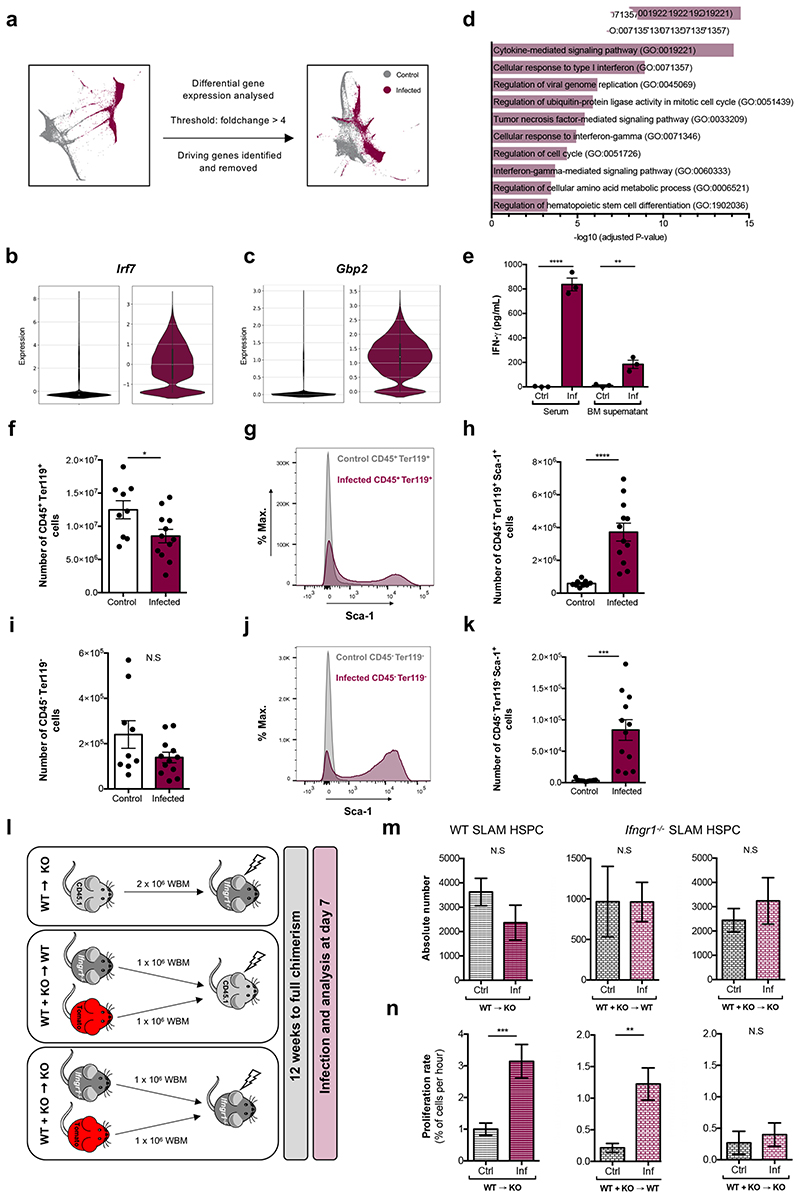

(a) Single force-graph embedding of combined control and infected cells highlighting the large separation between samples according to their infection status, regardless of cell type. Recalculating the force graph with ‘driving’ genes removed suggests they play a major role in driving this parting.

Violin plots show the expression of (b) Irf7 and (c) Gbp2 determined via scRNAseq analysis in control (black, left panels) and infected (maroon, right panels) samples.

(d) Representative results from a GO analysis of biological processes enriched in samples sequenced from infected mice compared to control.

(e) IFN-γ levels (pg/mL) measured by ELISA in serum and BM supernatant at day 7 psi (n = 3 per group).

(f) Absolute number of CD45+Ter119+ haematopoietic cells at day 7 psi (n = 9 control, 12 infected).

(g) Representative histogram plots and (h) absolute number of CD45+Ter119+Sca-1+ cells at day 7 psi (n = 9 control, 12 infected).

(i) Absolute number of CD45-Ter119- mixed haematopoietic and stroma cells at day 7 psi (n = 9 control, 12 infected).

(j) Representative histogram plots and (k) absolute number of CD45-Ter119-Sca-1+ cells at day 7 psi (n = 9 control, 12 infected).

(l) Schematic detailing the generation of Ifngr1 -/- reverse and mixed chimera groups that were subsequently infected and analysed.

(m) Absolute number and (n) proliferation rate of WT (n = 9 control, 7 infected) or Ifngr1 -/- (n = 5 control, 5 infected) SLAM HSPCs from chimeric mice.

Data pooled from up to 3 independent infections. All data presented as mean ± s.e.m. P values determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests. N.S, not significant.

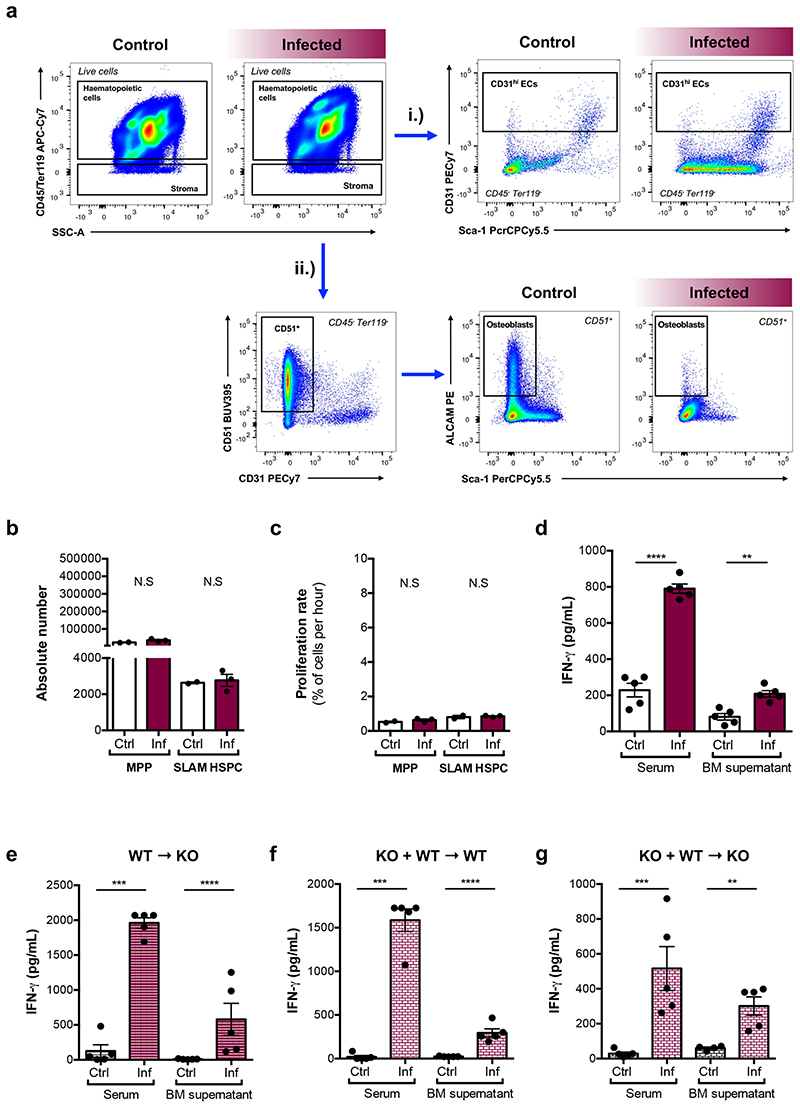

Based on this and given previous reports highlighting the complex effects of IFN-γ on HSCs and niche components29, we investigated how these effects may be coordinated, and whether the niche may be a key mediator. We tested whether not only HSPCs, but rather all BM cells - including stroma - would sense and respond to the elevated systemic and local IFN-γ in our model by measuring Sca-1 upregulation as a proxy of IFN-γ signalling30. Haematopoietic cells (CD45+ and/or Ter119+) were reduced in number and, as expected, had substantially upregulated Sca-1 (Fig. 3f-h). While the overall number of CD45-Ter119- mixed haematopoietic and stroma cells31 was not significantly affected (Fig. 3i), the majority of these cells also upregulated Sca-1 (Fig. 3j,k).

To dissect the importance of direct IFN-γ action on HSPCs versus an indirect action mediated by changes in the BM microenvironment, we studied IFN-γ receptor 1 (Ifngr1) knock out and chimeric mice. Consistent with previous studies, we observed no difference in SLAM HSPC and MPP compartment size and proliferation rate in control and infected Ifngr1 -/- mice (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b) despite the presence of high levels of IFN-γ (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Next, we generated reverse chimeras and two groups of 50:50 mixed-BM chimeras (Fig. 3l). Upon infection, IFN-γ levels were significantly higher in all three chimera types (Extended Data Fig. 4df). In the reverse chimeras, the number of total SLAM HSPCs was unchanged (Fig. 3m, left panel) and their proliferation rate significantly increased upon infection (Fig. 3n, left panel). In the mixed chimera groups, we analysed Ifngr1-deficient SLAM HSPCs. Their absolute numbers were unchanged in both groups (Fig. 3m, middle and right panels). SLAM HSPCs became highly proliferative upon infection in the presence of an Ifngr1 -proficient niche (Fig. 3n, middle panel). Interestingly, this response was suppressed in mixed chimeras with an Ifngr1-deficient niche (Fig. 3n, right panel). These data highlight that indirect, niche-mediated mechanisms contribute to HSC proliferation during infection, prompting further investigation into morphological and/or functional changes in the BM microenvironment.

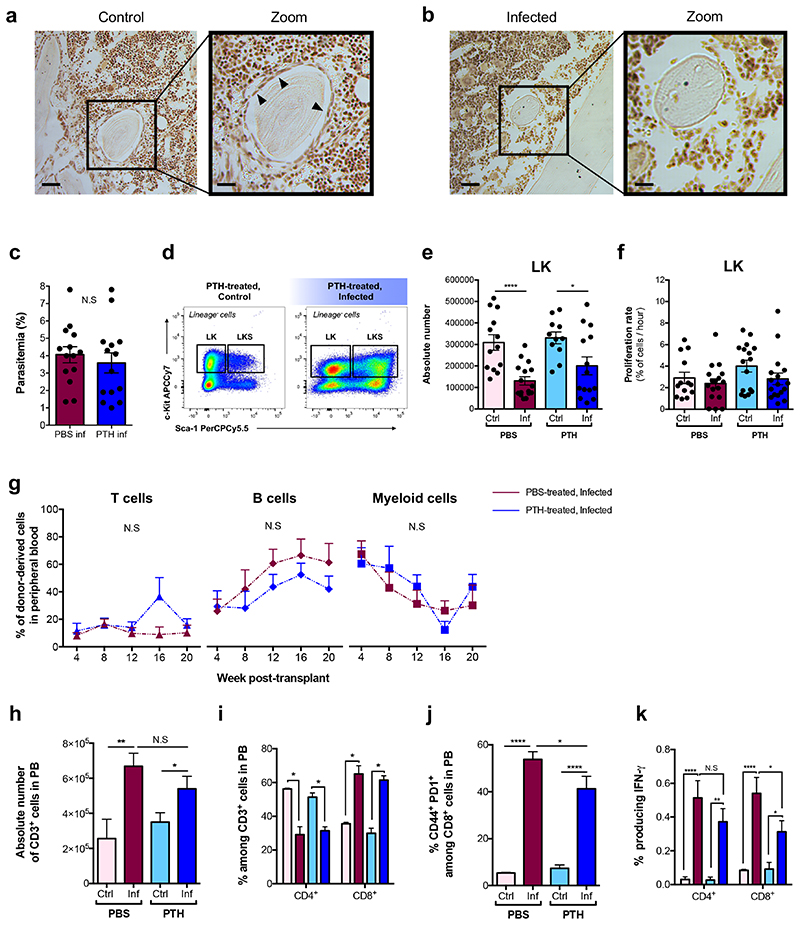

Targeting the osteolineage inhibits HSC proliferation in response to P. berghei infection

Osteoblasts have long been associated with HSC maintenance32–35. IVM of calvarium BM of control and infected Col2.3-GFP osteoblast reporter mice36 revealed a progressive and systemic loss of GFP+ cells throughout infection (Fig. 4a,b). To confirm that this reflected loss of osteoblasts, we examined histological sections of femurs. While endosteum-lining cells were visible in control sections, they were undetectable in infected ones (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b).

Fig. 4. Osteolineage targeting inhibits P. berghei-induced HSC proliferation.

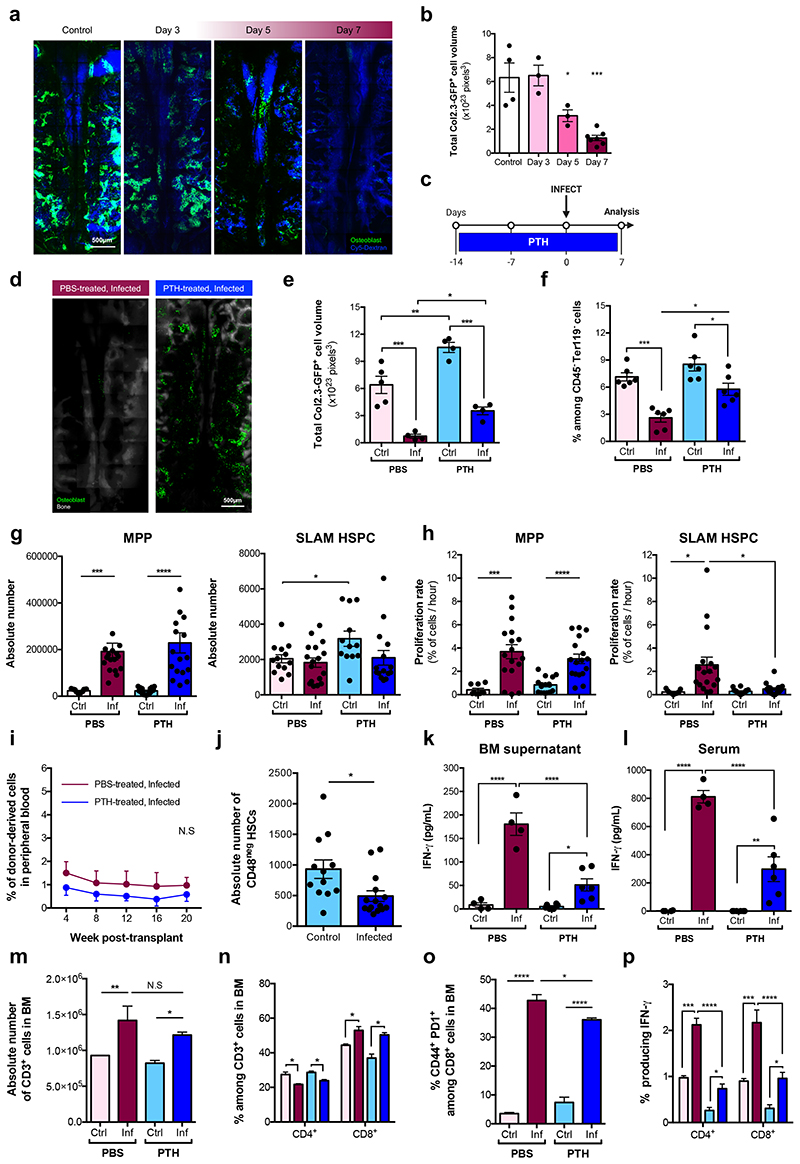

(a) Representative maximum projections and (b) automated segmentation and volume calculation (voxels) of Col2.3-GFP+ osteoblastic cells in tilescans of calvarium BM from control (n = 4) and infected Col2.3-GFP mice at day 3 (n = 3), 5 (n = 3) and 7 (n = 7) psi.

(c) Schematic of the PTH treatment regime.

(d) Representative maximum projections and (e) quantification of Col2.3-GFP+ osteoblastic cells in tilescans from PBS- (n = 5 control, 4 infected) and PTH-treated (n = 4 control, 4 infected) mice at day 7 psi.

(f) Proportion of osteoblasts identified by flow cytometry analysis of long-bones from PBS and PTH-treated mice at day 7 psi (n = 6 per group).

(g) Absolute number and (h) proliferation rate of MPP and SLAM HSPCs in PBS- and PTH-treated mice at day 7 psi (n > 9 per group).

(i) Peripheral blood reconstitution of transplanted SLAM HSPCs from PBS- and PTH-treated, infected mT/mG donors into lethally irradiated CD45.2 recipient mice, assessed by flow cytometry. (n = 6 per group).

(j) Absolute number of CD48neg HSCs in PTH-treated mice at day 7 psi (n = 12 control, 15 infected).

IFN-γ levels (pg/mL) measured by ELISA in (k) BM supernatant and (l) serum from PBS- (n = 4 control, 4 infected) and PTH-treated (n = 6 control, 6 infected) mice.

(m) Absolute number of CD3+ T-cells in BM from PBS- and PTH-treated mice.

(n) CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells as a proportion of CD3+ T-cells, (o) proportion of activated CD8+ T-cells and (p) proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells producing IFN-γ in the BM of PBS- and PTH-treated mice - quantified by flow cytometry.

n = 4 control, 5 infected (m - p). Data pooled from up to 6 independent infections. All data presented as mean ± s.e.m. P values determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests (g - j), one-way (b, e, f, k, l, m, o) or two-way (n, p) ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni corrections. N.S, not significant.

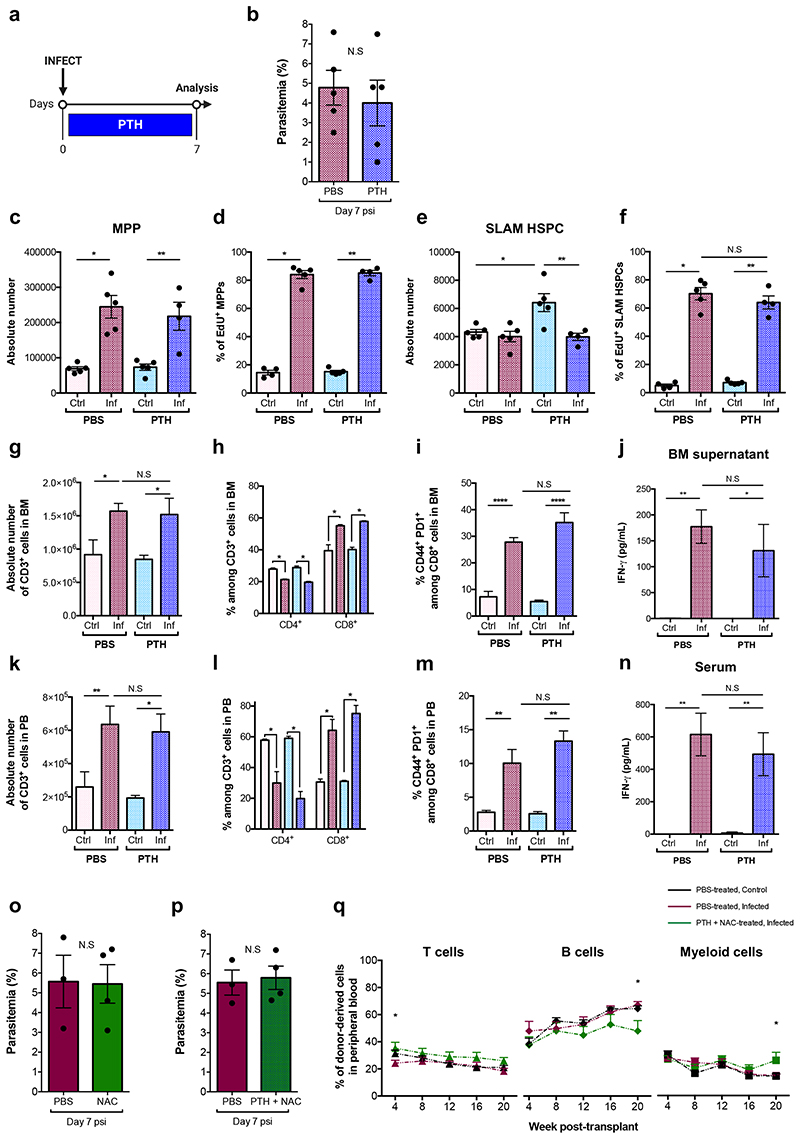

We reasoned that by targeting the osteolineage one may control HSC proliferation and rescue HSC function during infection. Intermittent treatment with Parathyroid hormone (PTH) enhances bone formation and increases osteoblast numbers by stimulating their proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis and driving osteoblast progenitor differentiation37–41. We treated mice with PTH for two weeks prior to and a further week during infection before sacrifice and analysis (Fig. 4c). While PTH had no effect on parasitaemia (Extended Data Fig. 5c), it had an anabolic effect on the osteolineage and a significant number of osteoblasts survived through infection, measured by IVM tilescans and flow cytometry analyses of long-bones (Fig. 4d-f).

To investigate the effects of PTH treatment on HSPC population dynamics, we measured their size and proliferation rate. Consistent with Sca-1 upregulation occurring in both groups of infected mice (Extended Data Fig. 5d), absolute number and proliferation rate of LK cells (Extended Data Fig. 5e,f) and MPPs (Fig. 4g,h, left panels) were similar in all infected animals. However, PTH treatment had a specific effect on SLAM HSPCs. In line with previous studies32,42,43, in control mice PTH treatment alone increased SLAM HSPCs’ number without affecting their proliferation rate (Fig. 4g,h, right panels). Importantly, SLAM HSPCs from PTH-treated, infected mice proliferated as little as those of control animals and significantly less than those of PBS-treated, infected mice.

To test whether PTH treatment could rescue HSC function, we performed transplantation assays with SLAM HSPCs purified from PBS- and PTH-treated, infected donors at day 7 psi. Surprisingly, we observed no difference between the engraftment and multilineage output of the two populations and overall donor-derived reconstitution was very low (Fig. 4i and Extended Data Fig. 5g). When we measured the number of CD48neg HSCs in PTH-treated mice, we observed that their abundance was significantly reduced in infected animals (Fig. 4j), despite proliferation not being induced. Interestingly, systemic and local IFN-γ levels were higher in PTH-treated, infected mice compared to PTH-treated, non-infected, however were significantly lower than those of PBS-treated, infected animals (Fig. 4k,l). Because PTH has immunomodulatory properties and T-cells have been described to contribute to the anabolic processes triggered by this hormone42,44, we analysed T-cells in the BM and blood of PBS- and PTH-treated mice. While there were no differences in the absolute number of T-cells and no change in proportion of T-cell subsets in the BM of PTH-treated mice (Fig. 4m,n), there was a significant decrease in the proportion of activated CD8+ T-cells in PTH-treated, infected animals compared to those that were PBS-treated (Fig. 4o). Further analyses revealed overall lower proportions of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells producing IFN-γ in PTH-treated, infected mice when compared to PBS-treated (Fig. 4p). This was reflected by T-cells analysed in the blood of these mice (Extended Data Fig. 5h-k). We observed this effect on T-cells only following the prolonged, anabolic PTH treatment regime, and not when PTH was administered exclusively for the week following infection initiation (Extended Data Fig. 6). This raises the interesting hypothesis that in this context PTH may not act directly/acutely on T-cells, but rather its immunomodulatory effects may be niche-mediated too. Together, these data suggest that although prolonged PTH treatment leads to partial retention of osteoblasts, avoidance of infection-induced HSC proliferation and a global reduction of IFN-γ levels, the remaining IFN-γ may still be sufficient to affect the long-term reconstitution capacity of HSCs exposed to P. berghei, possibly by affecting other niche components.

P. berghei infection alters the integrity of vessels in the BM microenvironment

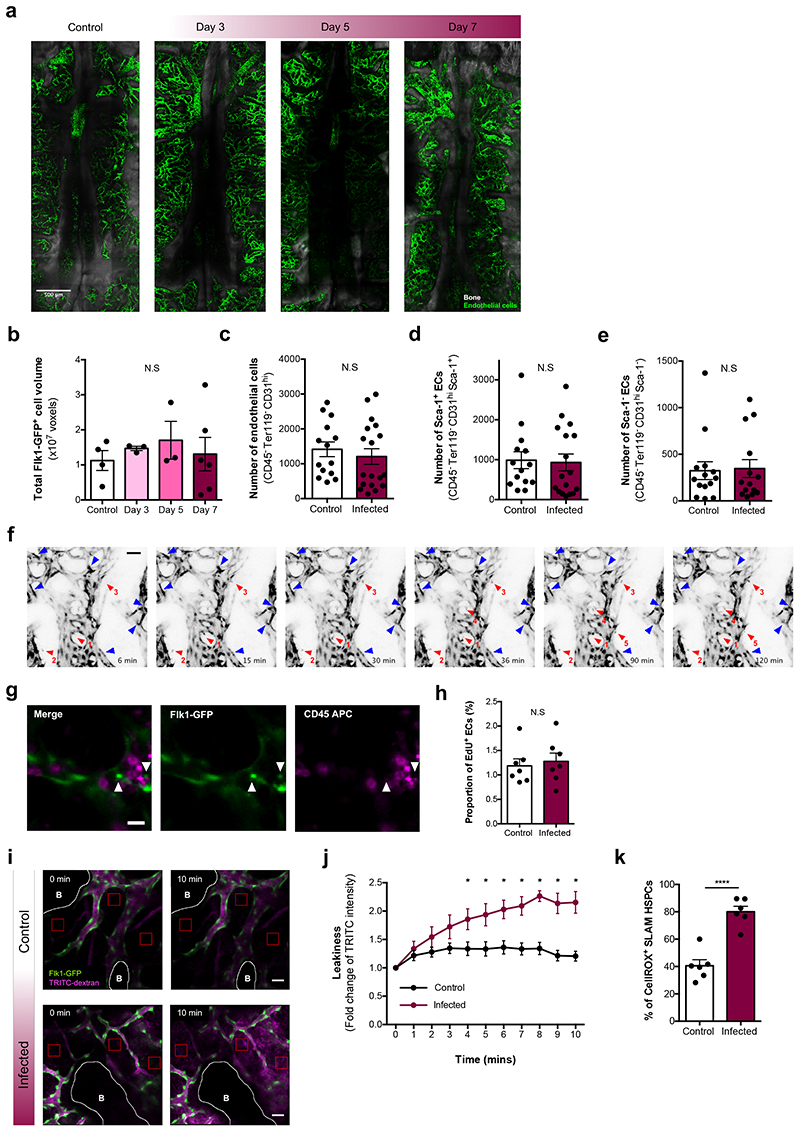

Osteoblasts have been shown to be dependent on healthy endothelial cells (ECs)45 and ECs support HSC maintenance and function46–49. Using IVM of Flk1-GFP transgenic mice50, we investigated the distribution, morphology and function of BM ECs. Tilescans revealed no obvious changes in BM vessels (Fig. 5a) and the number of GFP+ voxels remained constant throughout infection (Fig. 5b). Flow cytometry analysis of long-bone ECs, including arteriolar Sca-1+ and sinusoidal Sca-1- ECs, reflected this with no alterations by day 7 psi (Fig. 5c-e).

Fig. 5. P. berghei infection affects vascular integrity and function.

(a) Representative tilescan maximum projections and (b) automated segmentation and volume calculation (voxels) of Flk1-GFP+ ECs in tilescans of calvarium BM from control (n = 4) and infected Flkl-GFP mice at day 3 (n = 3), 5 (n = 3) and 7 (n = 6) psi.

(c) Absolute number of total ECs, (d) arteriolar Sca-1+ ECs, (e) sinusoidal Sca-1- ECs in control and infected mice at day 7 psi, analysed by flow cytometry (n > 14 per group).

(f) Selected frames from representative time-lapse imaging of an infected Flk1-GFP mouse, at day 7 psi, demonstrating shifting in centre of mass of certain ECs (blue arrowheads) and detachment from the endothelium and migration of GFP+ cells into the parenchyma (red, numbered arrowheads). Scale bar represents 50¼m.

(g) Representative maximum projection of an area of calvarium BM in an infected Flk1-GFP mouse, at day 7 psi, injected with CD45 antibody. White arrows indicate GFP+ cells that have detached from the endothelium. Scale bar represents 20¼m.

(h) Proportion of EdU+ ECs at day 7 psi, measured by flow cytometry (n = 7 control, 7 infected).

(i) Vascular leakiness assessed by time-lapse imaging of randomly selected regions (red boxes) within the calvarium following the administration of TRITC-dextran i.v. Selected frames from control and infected Flk1-GFP mice at day 7 psi demonstrate how extravasation of vascular dye over time allows quantification of vascular permeability. White lines delineate bone (B). Scale bar represents 50¼m.

(j) Quantification of the fold change of TRITC-dextran intensity in calvaria at day 7 psi. (n = 4 control, 5 infected with 4 positions acquired per mouse).

(k) Intracellular ROS levels in SLAM HSPCs measured by flow cytometry at day 7 psi (n = 6 control, 6 infected).

Data pooled from up to 6 independent infections. All data presented as mean ± s.e.m. P values determined by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni corrections (b) or unpaired two tailed Student’s t-tests (b - e, h, k) with Holm-Sidak corrections for multiple comparisons (j). N.S, not significant. In (j), * represents P < 0.05.

Time-lapse IVM of randomly selected calvarium BM areas in these mice revealed unusual dynamics over the course of a few hours. While the vasculature of control mice appeared static (Supplementary Video 1), in infected animals GFP+ cells were significantly more dynamic, with many shifting their centre of mass while maintaining their position along the vessel wall (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Video 1, blue arrowheads), and some separating from the vessel surface and migrating within the extravascular space (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Video 1, red numbered arrowheads). We confirmed by CD45 in vivo staining that these migratory cells were not haematopoietic51 (Fig. 5g). Questioning whether the observed GFP+ cells may be due to EC proliferation, flow cytometry analysis revealed no change in the proportion of EdU+ ECs by day 7 psi (Fig. 5h).

To assess whether the dynamism shown by ECs was an indication of vascular stress, we investigated whether damage developed during the course of P. berghei infection, using vascular leakiness as our readout52. Following the injection of TRITC-labelled dextran, time lapse imaging revealed that infected mice had highly permeable vessels (Fig. 5i,j and Supplementary Video 2). HSCs localised in the proximity of more leaky vessels have been shown to have higher levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)53. Thus, we measured intracellular ROS in SLAM HSPCs from infected animals and, as expected, the increased vascular leakiness triggered by P. berghei was associated with a 2-fold rise in the concentration of ROS (Fig. 5k).

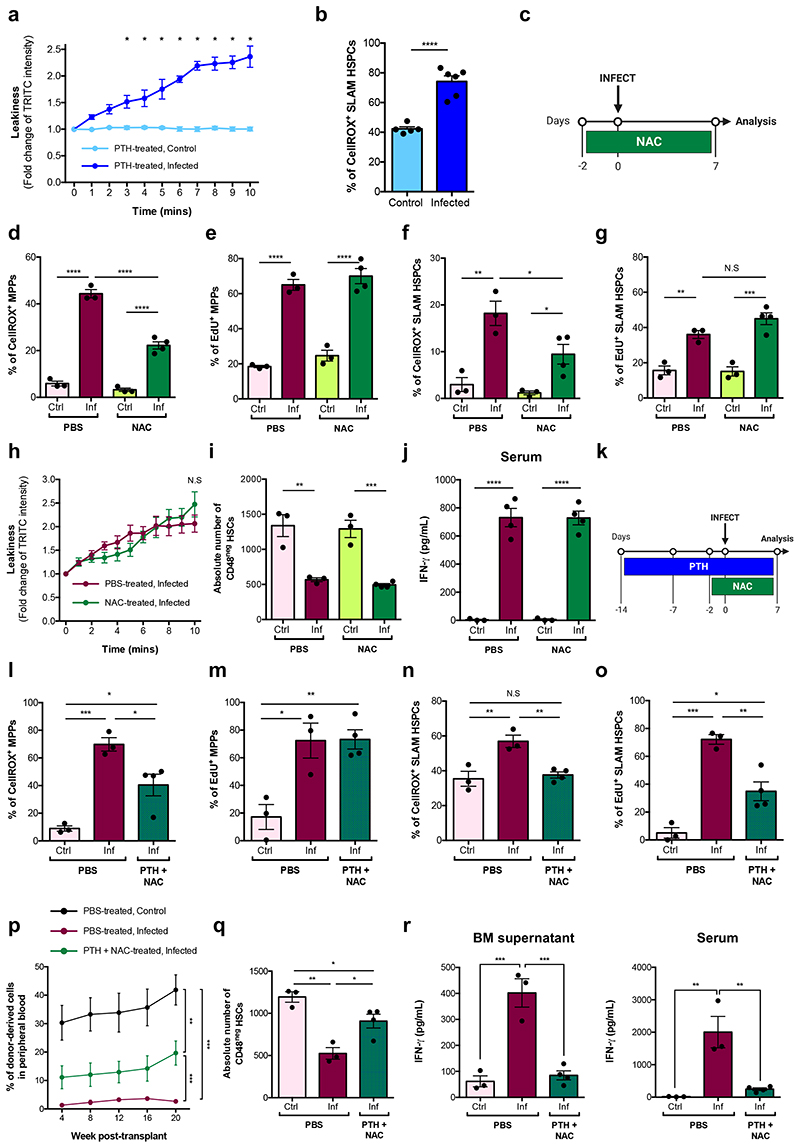

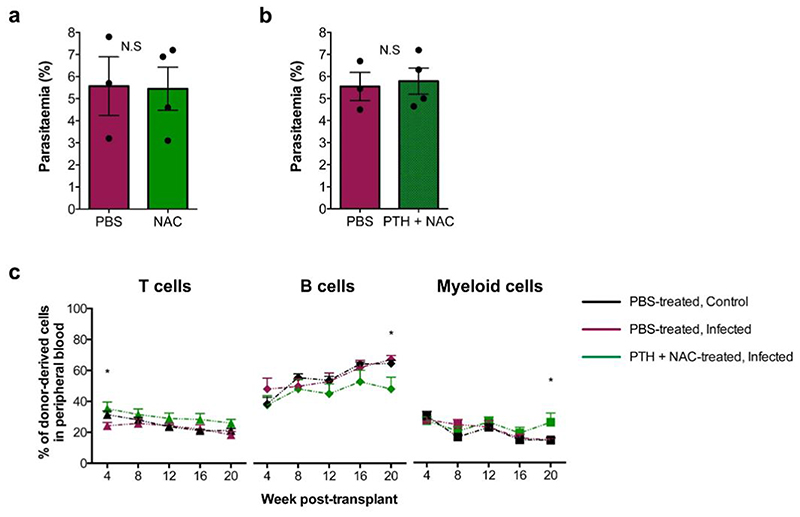

PTH treatment coupled with ROS scavenging rescues function of P. berghei-exposed HSCs

Our data on increased vascular leakiness and SLAM HSPC ROS suggest that they may inter alia be one of the mechanisms leading to loss of functional HSCs during P. berghei infection. In line with this, PTH-treated, infected animals exhibited leaky vasculature and increased ROS+ SLAM HSPCs (Fig. 6a,b). Vascular permeability is important in enabling immune responses globally, however ROS are highly damaging to cells. We reasoned that ROS may be an appropriate target to curb HSPC proliferation and/or damage in response to P. berghei infection. We treated mice with the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) daily from 2 days prior to infection until analysis (Fig. 6c). This had no effect on parasitaemia (Extended Data Fig. 7a), but reduced ROS in MPPs and SLAM HSPCs compared to PBS-treated, infected animals (Fig. 6d,f); however, proliferation of both cell types was comparable to that of PBS-treated, infected controls (Fig. 6e,g). After NAC treatment, vessels remained highly permeable (Fig. 6h), osteoblasts were lost and the absolute number of CD48neg HSCs was as reduced as in PBS-treated, infected mice (Fig. 6i). Consistent with this, IFN-γ levels remained elevated (Fig. 6j). These observations suggest that NAC treatment alone is insufficient to limit HSC and niche damage resulting from P. berghei infection.

Fig. 6. Treating infected animals with NAC reduces HSPC intracellular ROS levels.

(a) Quantification of the fold change of TRITC-dextran intensity measured in the calvaria of PTH-treated control (n = 5) and infected (n = 6) mice at day 7 psi.

(b) Cellular ROS levels in SLAM HSPCs measured by flow cytometry in PTH-treated, control (n = 5) and infected (n = 6) mice at day 7 psi.

(c) Schematic of the NAC treatment regime carried out.

Cellular ROS levels in (d) MPPs and (f) SLAM HSPCs measured by flow cytometry in PBS- and NAC-treated, control and infected mice at day 7 psi (n > 3 per group). Proportion of EdU+ (e) MPPs and (g) SLAM HSPCs in PBS- and NAC-treated, control and infected mice at day 7 psi, measured by flow cytometry (n > 3 per group).

(h) Quantification of the fold change of TRITC-dextran intensity measured in the calvaria of PBS- and NAC-treated control (n = 3) and infected (n = 3) mice at day 7 psi.

(i) Absolute number of CD48neg HSCs in PBS- and NAC-treated control and infected mice at day 7 psi, analysed by flow cytometry (n > 3 mice per group).

(j) IFN-γ levels (pg/mL) measured by ELISA in serum of PBS- and NAC-treated, control (n = 3) and infected (n = 4) mice at day 7 psi.

Data pooled from up to 2 independent infections. All data presented as mean ± s.e.m. P values determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests (b) with Holm-Sidak corrections for multiple comparisons (a, h) or one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni corrections (d - g, i, j). N.S, not significant. In (a), * represents P < 0.05.

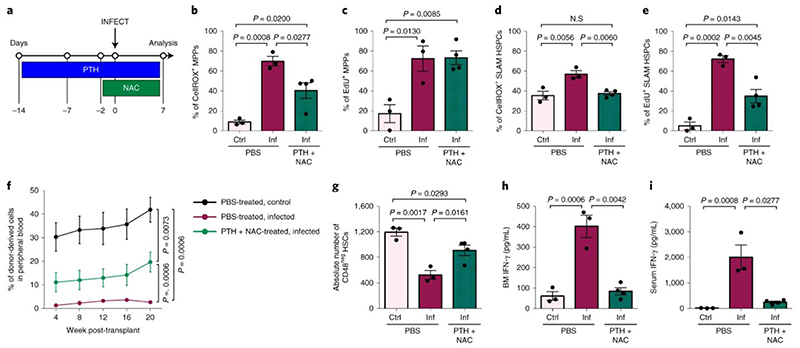

We hypothesized that a combination of PTH treatment to reduce proliferation and NAC treatment to reduce ROS levels could have a positive impact on HSC function. Mice were pre-treated with PTH for 2 weeks and NAC for 2 days prior to infection and both treatments continued until analysis (Fig. 7a). Parasitaemia was not affected by treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7b), but ROS levels in both MPPs and SLAM HSPCs were significantly reduced compared to PBS-treated, infected controls (Fig. 7b,d). Consistent with PTH treatment alone, PTH+NAC treatment did not affect MPPs’ proliferation (Fig. 7c), however it reduced the proportion of proliferating SLAM HSPCs compared to PBS-treated, infected controls (Fig. 7e). To determine whether this combined treatment could rescue HSC function, we transplanted SLAM HSPCs from each group into lethally irradiated recipient mice. Cells from control, healthy mice achieved the highest engraftment; however, PTH+NAC treatment led to significantly better engraftment of SLAM HSPCs (Fig 7f) - compared to the same cells from PBS-treated, infected donors - a lineage output similar to that of healthy donors (Extended Data Fig. 7c), and donors had notably more CD48neg HSCs in the BM (Fig. 7g). Interestingly, local and systemic levels of IFN-γ in combination-treated mice were strikingly lower than in PBS-treated, infected controls (Fig. 7h,i) and suggest, consistent with the scRNAseq GO analysis, that IFN-γ is not the only trigger of HSC damage in P. berghei-infected mice. Altogether, our data indicate that by targeting cellular or chemical components of the HSC niche it is possible to limit HSC loss during severe infection.

Fig. 7. Combining PTH treatment and sequestration of ROS during infection partially rescues HSC function.

(a) Schematic of the PTH and NAC combined-treatment regime carried out.

Cellular ROS levels in (b) MPPs and (d) SLAM HSPCs measured by flow cytometry in PBS- and PTH+NAC-treated, control and infected mice at day 7 psi (n > 3 mice per group).

Proportion of EdU+ (c) MPPs and (e) SLAM HSPCs in PBS- and PTH+NAC-treated, control and infected mice at day 7 psi, measured by flow cytometry (n > 3 mice per group).

(f) Peripheral blood reconstitution of transplanted SLAM HSPCs from PBS-treated, control (black line) and infected (maroon line) or PTH+NAC-treated, infected (green line) CD45.2 donors into lethally irradiated mT/mG recipient mice, assessed by flow cytometry of tomato-cells up to 20 weeks after transplantation (n > 6 mice per group).

(g) Absolute number of CD48neg HSCs in PBS-treated, control (n = 3) and infected (n = 3) mice and PTH + NAC-treated, infected mice (n = 4) at day 7 psi, analysed by flow cytometry.

(h) IFN-γ levels (pg/mL) measured by ELISA in BM supernatant and serum of PBS-treated, control (n = 3) and infected (n = 3) mice and PTH + NAC-treated, infected mice (n = 4) at day 7 psi.

Data pooled from up to 2 independent infections. All data presented as mean ± s.e.m. P values determined by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni corrections (b - e, g - i) or an exact one-tailed permutation test (f). N.S, not significant.

Discussion

HSC function is profoundly affected by severe infection, but the cellular and molecular mechanisms are not yet fully understood. Here, we used a natural Plasmodium infection to gain a quantitative understanding of its impact on primitive HSPC populations and to investigate the role of the BM microenvironment in mediating the phenotypes observed.

scRNAseq analysis of Lineage-c-Kit+ cells provided an unbiased approach and confirmed the development of emergency myelopoiesis described for multiple infections5,54,55. Moreover, we identified a dramatic loss of the most primitive HSPC transcriptional signature and, consistent with this, transplantation assays highlighted infection-induced loss of functional HSCs. Building on our previous qualitative observations9, we measured proliferation rate and compartment size of multiple HSPC populations, and a simple mathematical model demonstrated the extent of increased turnover of each population studied. Both SLAM HSPC and MPP populations turned over multiple times, and even the most quiescent CD48neg HSC compartment was seen to proliferate, albeit at a much lower rate. This suggests that other mechanisms beyond simply proliferation could be driving the dramatic loss of functional HSCs.

Gene expression profiling highlighted the central role of IFN in driving the observed phenotypes. IFN-γ is highly expressed in response to multiple strains of human and murine Plasmodium and contributes to controlling the intensity of infection25,26,28. It has, however, also been reported to mediate and exacerbate the disease itself, causing damage to the host27. In our model the IFN-response was shared across not only haematopoietic cells, but also BM stroma, including known components of the HSC niche. Consistent with a role of the BM microenvironment in mediating infection and IFN-γ-driven HSC damage, Ifngr1 -/- SLAM HSPCs in chimeric mice with haematopoietic cells derived from both WT and Ifngr1 -/- donors exhibited a proliferative response. Importantly, this was lost when stroma was Ifngr1-deficient, indicating that P. berghei-induced IFN-γ affects HSPCs both directly and indirectly, through niche cells that sense and respond to it.

It was recently reported that both Plasmodium infection and sepsis affect bone biology56,57. Sepsis-induced loss of osteoblasts has been linked to the loss of lymphoid progenitors and myeloid-skewed haematopoiesis, and the same mechanism is likely to take place in response to Plasmodium infection. Here, we show that loss of osteoblasts is specifically associated with primitive HSPC proliferation and loss of function, potentially through a reduction of the most HSC-enriched cell populations, including CD48neg HSCs. Osteoblast maintenance through PTH treatment was associated with the rescue of infection-induced HSC proliferation but did not preserve HSC function. This is an important finding as HSC proliferation and loss of function are usually directly linked5,8. While the effects seen on mature osteoblasts is dramatic, we cannot exclude an important role for other mesenchymal cells contributing to the effects of PTH; however, based on our data, it is unlikely that HSC proliferation is regulated directly by PTH-responsive T-cells.

BM vascular damage was recently reported in response to IFN-α58 and in mice burdened with malaria, where it was proposed to mediate parasite accumulation in the tissue59,60. Our data on vascular leakiness and HSPC intracellular ROS are consistent with previous observations that steady-state HSCs residing in the vicinity of more permeable vessels contain higher levels of ROS and are less functional53, suggesting that increased vascular permeability may be one of the mechanisms leading to loss of functional HSCs during P. berghei infection, and the same is likely to happen in human malaria. ROS trigger signalling cascades and are a recognised component of the HSC niche chemical milieu61. ROS quenching alone did not rescue vascular leakiness, nor SLAM HSPC proliferation or osteoblasts loss. However, combined PTH treatment and ROS quenching partially reduced SLAM HSPC proliferation and limited HSC function decline. PTH+NAC-treated mice displayed IFN-γ levels similar to those of uninfected animals, suggesting that PTH+NAC treatment does not impair immune responses and that IFN-γ is an important, yet not the only, trigger of HSC damage. Given the effects of PTH and NAC treatments alone, we propose that the two interventions combined may act side-by-side and on specific components of the HSC milieu, however further studies will be needed to fully understand the interplay of all the involved cell types within the BM. While our interventions are not directly translatable to malaria sufferers, our data provide a promising indication that it might prove possible to limit HSC damage during severe infection, and future work should focus on identifying therapeutic approaches aimed at preserving HSCs through the course of severe infections.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 2.

Extended Data Figure 3.

Extended Data Figure 4.

Extended Data Figure 5.

Extended a Data Figure 6.

Extended a Data Figure 7.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by ERC, BBSRC and the Wellcome Trust (ERC_STG 337066, BB/L023776/1, IA 212304/Z/18/Z to C.L.C, PhD studentship 105398/Z/14/Z to M.L.R.H). A.M.B was funded by the MRC (NIRG MR/N00227X/1); S.W by an MRC studentship; T.C.L by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship (210424/Z/18/Z). Work in the Göttgens group is funded by the Wellcome Trust, Bloodwise, CRUK and core funding by the Wellcome & MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute. C.L.C and K.R.D were supported in part by the Royal Irish Academy - Royal Society International Exchange Program (IEC\R1\180061).

We thank Mark Tunnicliff for passaging parasites and preparing mosquitos, Dr Fiona Angrisano and Kasia Sala for technical assistance and advice with infections, Dr Iwo Kucinski for support creating the interactive website; Imperial College DoLS Flow Cytometry and Central Biomedical Services and Crick Biological Research Facilities for their support; Helen Fletcher, Aubrey Cunnington and all Lo Celso group members for constructive discussions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

M.L.R.H., C.L.C., A.M.B. and R.E.S. conceived the project. A.M.B. provided all mosquitos and support with infections. M.L.R.H. conducted core experiments and data analysis. K.E., A.L., H.A., F.B., C.P, S.G.A. and N.R. performed animal and flow cytometry experiments. S.W., N.K.W. and B.G. implemented scRNAseq and analysis. K.R.D. conducted mathematical modelling. M.L.V. created histological sections. C.P., T.C.L., J.L. contributed to experimental design and data analysis. M.L.R.H. and C.L.C. analysed data and wrote the manuscript, with all authors contributing feedback.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;505:327–334. doi: 10.1038/nature12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essers MAG, et al. IFNα activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009;458:904. doi: 10.1038/nature07815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esplin BL, et al. Chronic Exposure to a TLR Ligand Injures Hematopoietic Stem Cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5367–5375. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King KY, Goodell MA. Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011;11:685. doi: 10.1038/nri3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacNamara KC, Jones M, Martin O, Winslow GM. Transient Activation of Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells by IFNγ during Acute Bacterial Infection. Plos One. 2011;6:e28669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldridge MT, King KY, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Goodell MA. Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-γ in response to chronic infection. Nature. 2010;465:793. doi: 10.1038/nature09135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashidi NM, et al. In vivo time-lapse imaging shows diverse niche engagement by quiescent and naturally activated hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2014;124:79–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-534859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matatall KA, et al. Chronic Infection Depletes Hematopoietic Stem Cells through Stress-Induced Terminal Differentiation. Cell Reports. 2016;17:2584–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vainieri ML, et al. Systematic tracking of altered haematopoiesis during sporozoite-mediated malaria development reveals multiple response points. Open Biology. 2016;6:160038. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips MA, et al. Malaria. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2017;3:nrdp201750. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dörmer P, Dietrich M, Kern P, Horstmann R. Ineffective erythropoiesis in acute human P. falciparum malaria. Blut. 1983;46:279–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00319868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maggio-Price L, Brookoff D, Weiss L. Changes in hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow of mice with Plasmodium berghei malaria. Blood. 1985;66:1080–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wickramasinghe S, Looareesuwan S, Nagachinta B, White N. Dyserythropoiesis and ineffective erythropoiesis in Plasmodium vivax malaria. British Journal of Haematology. 1989;72:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb07658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boehm D, Healy L, Ring S, Bell A. Inhibition of ex vivo erythropoiesis by secreted and haemozoin-associated Plasmodium falciparum products. Parasitology. 2018;145:1865–1875. doi: 10.1017/S0031182018000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orf K, Cunnington AJ. Infection-related hemolysis and susceptibility to Gram-negative bacterial co-infection. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6:666. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White NJ. Anaemia and malaria. Malaria Journal. 2018;17:371. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mamedov MR, et al. A Macrophage Colony-Stimulating-Factor-Producing γδ T Cell Subset Prevents Malarial Parasitemic Recurrence. Immunity. 2018;48:350–363.:e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinreb C, Wolock S, Klein A. SPRING: a kinetic interface for visualizing high dimensional single-cell expression data. Bioinform Oxf Engl. 2017 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamey FK, Göttgens B. Machine learning predicts putative haematopoietic stem cells within large single-cell transcriptomics datasets. Exp Hematol. 2019;78:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson A, et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cells Reversibly Switch from Dormancy to Self-Renewal during Homeostasis and Repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oguro H, Ding L, Morrison SJ. SLAM Family Markers Resolve Functionally Distinct Subpopulations of Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Multipotent Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:102–116. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabezas-Wallscheid N, et al. Identification of Regulatory Networks in HSCs and Their Immediate Progeny via Integrated Proteome, Transcriptome, and DNA Methylome Analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akinduro O, et al. Proliferation dynamics of acute myeloid leukaemia and haematopoietic progenitors competing for bone marrow space. Nat Commun. 2018;9:519. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02376-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kent DG, et al. Prospective isolation and molecular characterization of hematopoietic stem cells with durable self-renewal potential. Blood. 2009;113:6342–6350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meding S, Cheng S, Simon-Haarhaus B, Langhorne J. Role of gamma interferon during infection with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Infection and immunity. 1990;58:3671–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3671-3678.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John CC, et al. Gamma Interferon Responses to Plasmodium falciparum Liver-Stage Antigen 1 and Thrombospondin-Related Adhesive Protein and Their Relationship to Age, Transmission Intensity, and Protection against Malaria. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72:5135–5142. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5135-5142.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King T, Lamb T. Interferon-γ: The Jekyll and Hyde of Malaria. PLOS Pathogens. 2015;11:e1005118. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lelliott PM, Coban C. IFN-γ protects hepatocytes against Plasmodium vivax infection via LAP-like degradation of sporozoites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113:6813–6815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607007113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morales-Mantilla DE, King KY. The Role of Interferon-Gamma in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Development, Homeostasis, and Disease. Curr Stem Cell Reports. 2018;4:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s40778-018-0139-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma X, Ling K, Dzierzak E. Cloning of the Ly-6A (Sca-1) gene locus and identification of a 3’ distal fragment responsible for high-level γ-interferon-induced expression in vitro. British Journal of Haematology. 2001;114:724–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulais PE, et al. The Majority of CD45– Ter119–CD31– Bone Marrow Cell Fraction Is of Hematopoietic Origin and Contains Erythroid and Lymphoid Progenitors. Immunity. 2018;49:627–639.:e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calvi LM, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arai F, et al. Tie2/Angiopoietin-1 Signaling Regulates Hematopoietic Stem Cell Quiescence in the Bone Marrow Niche. Cell. 2004;118:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo Celso C, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009;457:92. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalajzic I, et al. Use of Type I Collagen Green Fluorescent Protein Transgenes to Identify Subpopulations of Cells at Different Stages of the Osteoblast Lineage. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2002;17:15–25. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jilka RL, et al. Increased bone formation by prevention of osteoblast apoptosis with parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:439–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jilka RL. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone. 2007;40:1434–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jilka RL, et al. Intermittent PTH stimulates periosteal bone formation by actions on post-mitotic preosteoblasts. Bone. 2009;44:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim SW, et al. Intermittent parathyroid hormone administration converts quiescent lining cells to active osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:2075–2084. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balani DH, Ono N, Kronenberg HM. Parathyroid hormone regulates fates of murine osteoblast precursors in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3327–3338. doi: 10.1172/JCI91699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J-Y, et al. PTH expands short-term murine hemopoietic stem cells through T cells. Blood. 2012;120:4352–4362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao H, et al. Parathyroid Hormone Enhances Hematopoietic Expansion Via Upregulation of Cadherin-11 in Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. STEM CELLS. 2014;32:2245–2255. doi: 10.1002/stem.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terauchi M, et al. T Lymphocytes Amplify the Anabolic Activity of Parathyroid Hormone through Wnt10b Signaling. Cell Metabolism. 2009;10:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duarte D, et al. Inhibition of Endosteal Vascular Niche Remodeling Rescues Hematopoietic Stem Cell Loss in AML. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hooper AT, et al. Engraftment and Reconstitution of Hematopoiesis Is Dependent on VEGFR2-Mediated Regeneration of Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butler JM, et al. Endothelial Cells Are Essential for the Self-Renewal and Repopulation of Notch-Dependent Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobayashi H, et al. Angiocrine factors from Akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12:1046. doi: 10.1038/ncb2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkler IG, et al. Vascular niche E-selectin regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy, self renewal and chemoresistance. Nature Medicine. 2012;18:1651. doi: 10.1038/nm.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishitobi H, et al. Flk1-GFP BAC Tg Mice: An Animal Model for the Study of Blood Vessel Development. Exp Anim Tokyo. 2010;59:615–622. doi: 10.1538/expanim.59.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirito K, Fox N, Komatsu N, Kaushansky K. Thrombopoietin enhances expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in primitive hematopoietic cells through induction of HIF-1α. Blood. 2005;105:4258–4263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Passaro D, et al. Increased Vascular Permeability in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment Contributes to Disease Progression and Drug Response in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:324–341.:e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Itkin T, et al. Distinct bone marrow blood vessels differentially regulate haematopoiesis. Nature. 2016;532:323. doi: 10.1038/nature17624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boettcher S, et al. Cutting Edge: LPS-Induced Emergency Myelopoiesis Depends on TLR4-Expressing Nonhematopoietic Cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:5824–5828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schürch CM, Riether C, Ochsenbein AF. Cytotoxic CD8+ T Cells Stimulate Hematopoietic Progenitors by Promoting Cytokine Release from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:460–472. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee MS, et al. Plasmodium products persist in the bone marrow and promote chronic bone loss. Science Immunology. 2017;2:eaam8093. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aam8093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terashima A, et al. Sepsis-Induced Osteoblast Ablation Causes Immunodeficiency. Immunity. 2016;44:1434–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prendergast ÁM, et al. IFNα-mediated remodeling of endothelial cells in the bone marrow niche. Haematologica. 2016;102:445–453. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.151209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niz MD, et al. Plasmodium gametocytes display homing and vascular transmigration in the host bone marrow. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaat3775. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joice R, et al. Plasmodium falciparum transmission stages accumulate in the human bone marrow. Science Translational Medicine. 2014;6:244re5-244re5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Batsivari A, et al. Dynamic responses of the haematopoietic stem cell niche to diverse stresses. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22:7–17. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.