Abstract

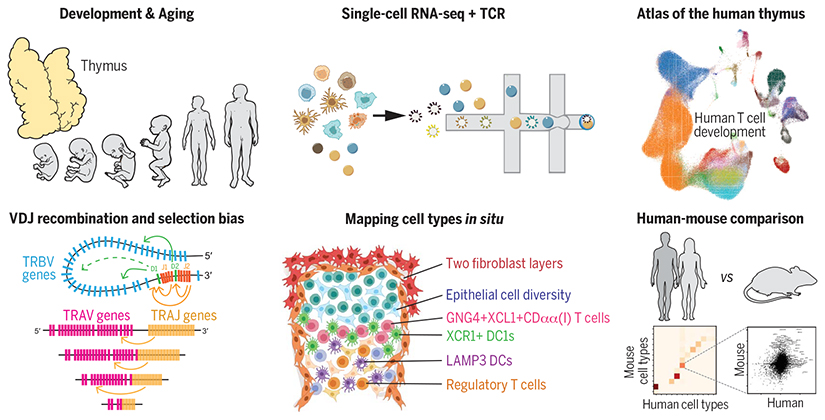

The thymus provides a nurturing environment for the differentiation and selection of T cells, a process orchestrated by their interaction with multiple thymic cell types. We used single-cell RNA sequencing to create a cell census of the human thymus across the life span and to reconstruct T cell differentiation trajectories and T cell receptor (TCR) recombination kinetics. Using this approach, we identified and located in situ CD8αα+ T cell populations, thymic fibroblast subtypes, and activated dendritic cell states. In addition, we reveal a bias in TCR recombination and selection, which is attributed to genomic position and the kinetics of lineage commitment. Taken together, our data provide a comprehensive atlas of the human thymus across the life span with new insights into human T cell development.

The thymus plays an essential role in the establishment of adaptive immunity and central tolerance as it mediates the maturation and selection of T cells. This organ degenerates early during life, and the resulting reduction in T cell output has been linked to age-related incidence of cancer, infection, and autoimmunity (1, 2). T cell precursors from fetal liver or bone marrow migrate into the thymus, where they differentiate into diverse types of mature T cells (3, 4). The thymic microenvironment cooperatively supports T cell differentiation (5, 6). Although thymic epithelial cells (TECs) provide critical cues to promote T cell fate (7), other cell types are also involved in this process, such as dendritic cells (DCs), which undertake antigen presentation, and mesenchymal cells, which support TEC differentiation and maintenance (8–11). Seminal experiments in animal models have provided major insights into the function and cellular composition of the thymus (12, 13). More recently, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed new aspects of thymus organogenesis and new types of TECs in mouse (14–16). However, the human organ matures in a mode and tempo that is unique to our species (17–19), calling for a comprehensive genome-wide study for human thymus.

T cell development involves a parallel process of staged T cell lymphocyte differentiation accompanied by acquisition of a diverse TCR repertoire for antigen recognition (20). This is achieved by the genomic recombination process that selects variable (V), joining (J), and, in some cases, diversity (D) gene segments from the multiple genomic copies. This V(D)J gene recombination can preferentially include certain gene segments, leading to the skewing of the repertoire (21–23). To date, most of our knowledge of VDJ recombination and repertoire biases has come from animal models and human peripheral blood analysis, with little comprehensive data on the human thymic TCR repertoire (22, 24, 25).

Here, we applied scRNA-seq to generate a comprehensive transcriptomic profile of the diverse cell populations present in embryonic, fetal, pediatric, and adult stages of the human thymus, and we combined this with detailed TCR repertoire analysis to reconstruct the T cell differentiation process.

Cellular composition of the human thymus across life

We performed scRNA-seq on 15 prenatal thymi ranging from 7 PCW (post-conception weeks), when the thymic rudiment can be dissected, to 17 PCW, when thymic development is complete (Fig. 1, A and B). We also analyzed nine postnatal samples covering the entire period of active thymic function. Isolated single cells were sorted on the basis of CD45, CD3, or epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) expression to sample thymocytes and enrich for non-thymocytes, prior to single-cell transcriptomic analysis coupled with TCRαβ profiling. After quality control including doublet removal, we obtained a total of 138,397 cells from developing thymus and 117,504 cells from postnatal thymus (table S1). If available, other relevant organs were collected from the same donor. We performed batch correction using the BBKNN algorithm combined with linear regression (fig. S1) (26).

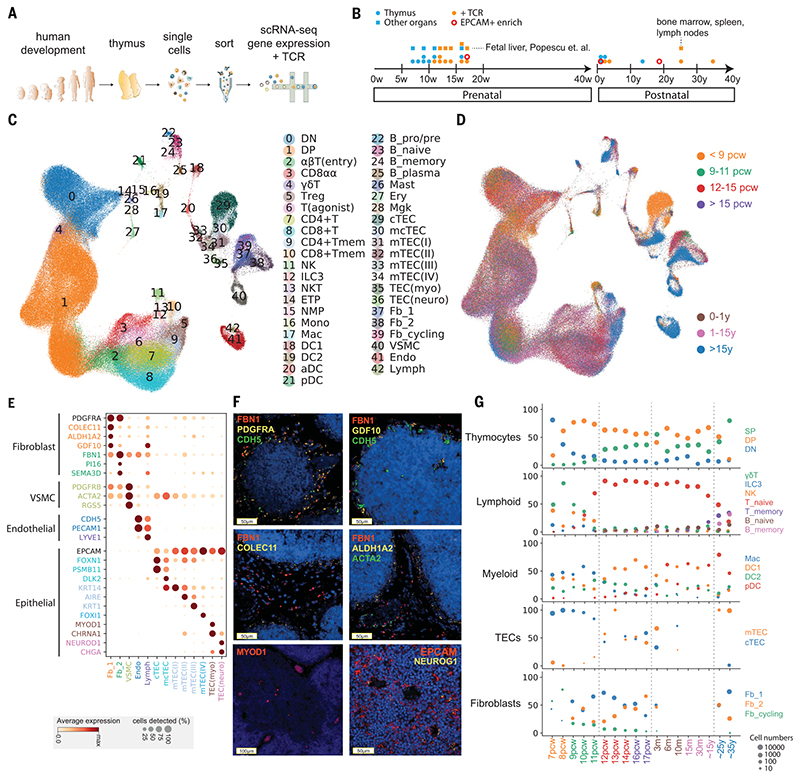

Fig. 1. Cellular composition of the developing human thymus.

(A) Schematic of single-cell transcriptome profiling of the developing human thymus. (B) Summary of gestational stage/age of samples, organs (circles denote thymus; rectangles denote fetal liver or adult bone marrow, adult spleen, and lymph nodes), and 10x Genomics chemistry (colors). (C) UMAP visualization of the cellular composition of the human thymus colored by cell type (DN, double-negative T cells; DP, double-positive T cells; ETP, early thymic progenitor; aDC, activated dendritic cells; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; Mono, monocyte; Mac, macrophage; Mgk, megakaryocyte; Endo, endothelial cells; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells; Fb, fibroblasts; Ery, erythrocytes). (D) Same UMAP plot colored by age groups, indicated by post-conception weeks (PCW) or postnatal years (y). (E) Dot plot for expression of marker genes in thymic stromal cell types. Here and in later figures, color represents maximum-normalized mean expression of marker genes in each cell group, and size indicates the proportion of cells expressing marker genes. (F) RNA smFISH in human fetal thymus slides with probes targeting stromal cell populations. Top left: Fb2 population marker FBN1 and general fibroblast markers PDGFRA and CDH5. Top right: Fb1 marker GDF10, FBN1, and CDH5. Middle left: Fb1 marker COLEC11 and FBN1. Middle right: Fb1 marker ALDH1A2, VSMC marker ACTA2, and FBN1. Bottom left: TEC(myo) marker MYOD1. Bottom right: Epithelial cell marker EPCAM and TEC(neuro) marker NEUROG1. Data are representative of two experiments. (G) Relative proportion of cell types throughout different age groups. Dot size is proportional to absolute cell numbers detected in the dataset. Statistical testing for population dynamics was performed by t tests using proportions between stage groups. The x axis shows age of samples, which are colored in the same scheme as (D).

We annotated cell clusters into more than 40 different cell types or cell states (Fig. 1, C and D, and tables S2 and S3), which can be clearly identified by the expression of specific marker genes (fig. S2 and table S4). Differentiating T cells are well represented in the dataset, including double negative (DN), double positive (DP), CD4+ single positive (CD4+), CD8+ single positive (CD8+), FOXP3+ regulatory (Treg), CD8αα+, and γδ T cells. We also identified other immune cells including B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), macrophages, monocytes, and DCs. DCs can be further classified into myeloid/conventional DC1 and DC2 and plasmacytoid DC (pDC).

Our dataset also featured the diverse non-immune cell types that constitute the thymic microenvironment. We further classified them into subtypes including TECs, fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), endothelial cells, and lymphatic endothelial cells (Fig. 1E). Thymic fibroblasts were further divided into two subtypes, neither of which has been previously described: fibroblast type 1 (Fb1) cells (COLEC11, C7, GDF10) and fibroblast type 2 (Fb2) cells (PI16, FN1, FBN1) (Fig. 1E). Fb1 cells uniquely express COLEC11, which plays an important role in innate immunity (27), and ALDH1A2, an enzyme responsible for the production of retinoic acid, which regulates epithelial growth (28). In contrast, extracellular matrix (ECM) genes and semaphoring which regulate vascular development (29), are specifically detected in Fb2 (fig. S3A). To explore the localization pattern of these fibroblast subtypes, we performed in situ single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) targeting Fb1 and Fb2 markers (COLEC11 and FBN1) together with general fibroblast (PDGFRA), endothelial (CDH5), and VSMC (ACTA2) markers (Fig. 1F). The results show that Fb1 cells were perilobular, whereas Fb2 cells were interlobular and were often associated with large blood vessels lined with VSMCs, consistent with their transcriptomic profile of genes regulating vascular development. We confirmed the expression of GDF10 and ALDH1A2 localized in the perilobular area (Fig. 1F).

In addition to fibroblasts, we also identified subpopulations of human TECs (Fig. 1E and fig. S4), such as medullary and cortical TECs (mTECs and cTECs). To maximize the coverage of epithelial cells, we enriched for EpCAM-positive cells across several time points (Fig. 1B). To annotate human TECs, we compared our human dataset to the published mouse TEC dataset (15) (figs. S5 to S7). We were able to identify conserved TEC populations across species, including PSMB11-positive cTECs, KRT74-positive mTEC(I)s, AIRE-expressing mTEC(II)s, and KRT1-expressing mTEC(III)s (Fig. 1E and fig. S4). Interestingly, cTECs were more abundant during early development (7 to 8 PCW), and an intermediate population (mcTECs), marked by expression of DLK2, was evident in late fetal and pediatric human thymi (fig. S4B). We identified a very rare population of mTEC(IV)s in humans, which are similar to tuft-like mTEC(IV)s described in the mouse thymus. However, DCLK1 or POU2F3, the markers used to define mTEC(IV)s in mouse (15, 16), were enriched but not specific to this population in human (figs. S4B, S5, and S6). We noted two EpCAM+ cell types that are specific to human: (i) MYOD1- and MYOG-expressing myoid cells [TEC(myo)s] and (ii) NEUROD1-, NEUROG1-, and CHGA-expressing TEC(neuro)s, which resemble neuroendocrine cells (Fig. 1E and figs. S6 and S7). Notably, CHRNA1, which has been associated with the autoimmune disease myasthenia gravis (30), was specifically expressed by both of these cell types in addition to mTEC(II)s (Fig. 1E), expanding the pool of candidate cell types that may be involved in tolerance induction in myasthenia gravis (31, 32). In support of this possibility, we detected MYOD1- and NEUROG1-expressing cells preferentially located in thymic medulla (Fig. 1F).

Lastly, we analyzed the expression pattern of genes known to cause congenital T cell immunodeficiencies to provide insight into when and where these rare disease genes may play a role during thymic development (fig. S8).

Coordinated development of thymic stroma and T cells

Next, we investigated the dynamics of the different thymic cell types across development (Fig. 1G). In the early fetal samples (7 to 8 PCW), the lymphoid compartment contained NK cells, γδ T cells, and ILC3s, with very few differentiating αβT cells. Differentiating T cells were mostly found at DN stage in 7 PCW samples; they gradually progressed through DP to SP stages thereafter, reaching equilibrium around 12 PCW. Conversely, the proportion of innate lymphocytes decreased.

Of note, the adult sample showed morphological evidence of thymic degeneration (fig. S9). Comparison with spleen and lymph nodes taken from the same donor showed the presence of terminally differentiated T cells in the thymus, suggesting reentry into thymus or contamination with circulating cells (Fig. 1G and fig. S10). Notably, cytotoxic CD4+ T lymphocytes (CD4+ CTLs) expressing IL10,perforin, and granzymes were enriched in the degenerated thymus sample (33)(fig. S10C). The trendof increased memory T cells and B cells was also confirmed in other samples (Fig. 1G; P = 9.3 × 10−6 for memory T cells, P = 0.0096 for memory B cells).

The trend in T cell development was mirrored by corresponding changes in thymic stromal cells. We observed temporal changes in TEC populations starting from enriched cTECs toward the balanced representation of cTECs and mTECs (Fig. 1G; P = 0.0054), aligned with the onset of T cell maturation. This supports the notion of “thymic cross-talk” in which epithelial cells and mature T cells interact synergistically to support their mutual differentiation (34).

Moreover, fibroblast composition also changed during development. The Fb1 population mentioned above dominated early development, with similar numbers of Fb1 and Fb2 cells observed at later developmental time points (P = 0.014) and a reduction in the number of cycling cells (Fig. 1G). This was also confirmed by thymic fibroblast explant cultures, which showed an increase in the Fb2 cell marker PI16 by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (fig. S3, B and C).

Finally, other immune cells also change dynamically over gestation and in postnatal life. Macrophages were abundant during early gestation, whereas DCs increased throughout development (Fig. 1G). DC1 was dominant after 12 PCW, and pDCs increased in frequency in postnatal life (P = 2.7 × 10−8 for macrophage, P = 1.05 × 10−3 for DC1, P = 4.86 × 10−5 for DC2).

To further investigate the factors mediating the coordinated development of thymic stroma and T cells, we systematically investigated cellular interactions using our public database CellPhoneDB.org (35) to predict the ligandreceptor pairs specifically expressed across them (table S5). Among the predicted interactions, we checked the expression pattern of signaling factors known to be involved in thymic development across different cell types and developmental stages (fig. S11) (36–41). Lymphotoxin signaling (LTB:LTBR) comes from diverse immune cells and is received by most of the stromal cell states. In contrast, RANKL-RANK (ZNFRSF11:ZNFRSF11A) signaling is confined between ILC3 and mTEC(II)s/lymphatic endothelial cells. FGF signaling (FGF7:FGFR2) comes from fibroblasts signaling to TECs, with decreasing expression of FGFR2 in adult thymus. For Notch signaling, NOTCH1 is the main receptor expressed in early thymic progenitors (ETPs), and diverse Notch ligands are expressed by different cell types: cTECs and endothelial cells express both JAG2 and DLL4, and other TECs broadly express JAG1 (42, 43).

Conventional T cell differentiation trajectory

Because fetal liver is the main hematopoietic organ and source of hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors (HSCs/MPPs) when the thymic rudiment develops, we analyzed paired thymus and liver samples from the same fetus (44), similar to what has been described for early hematopoietic organs (45). We merged the thymus and liver data, and selected clusters including liver HSCs/MPPs, thymic ETPs, and DN thymocytes for data analysis and visualization (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S12). This positioned thymic ETPs at the isthmus between fetal liver HSCs/MPPs and pre/pro-B cells. We integrated our liver/thymic hematopoietic progenitor subset with the single-cell transcriptomes of human hematopoietic progenitors sorted from bone marrow using defined markers (46) (fig. S13). This analysis positions the ETPs next to the multilymphoid progenitor (MLP) from bone marrow and early lymphoid progenitor in fetal liver.

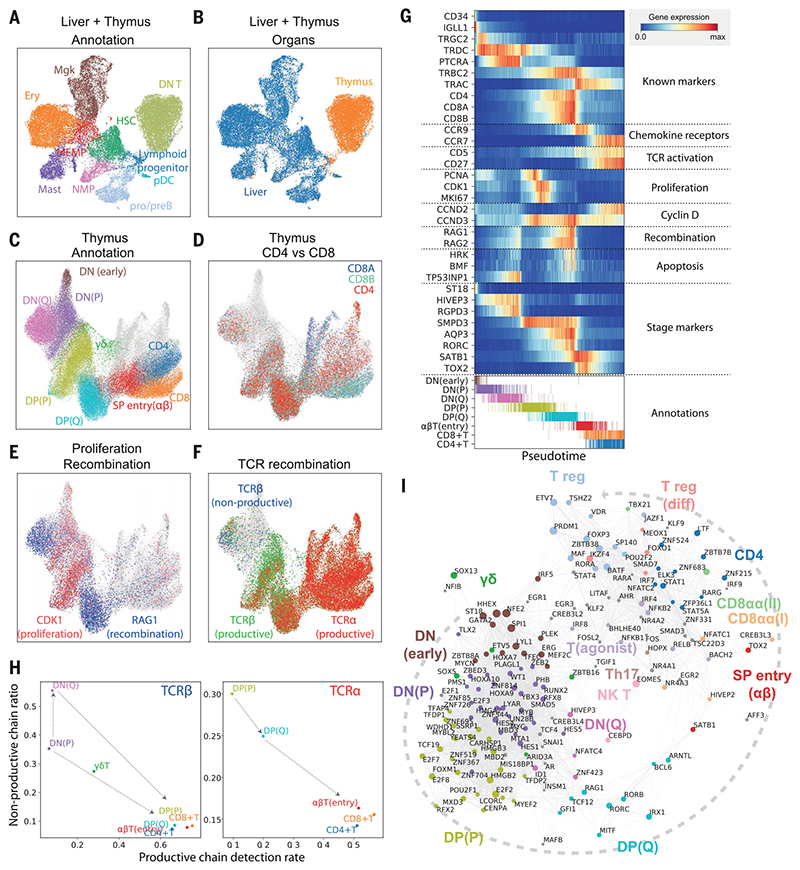

Fig. 2. Thymic seeding of early thymic progenitors (ETPs) and T cell differentiation trajectory.

(A) UMAP visualization of ETP and fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and early progenitors. NMP, neutrophil-myeloid progenitor; MEMP, megakaryocyte/erythrocyte/mast cell progenitor. (B) The same UMAP colored by organ (liver in blue, thymus in yellow/red). (C) UMAP visualization of developing thymocytes after batch correction. DN, doublenegative T cells; DP, double-positive T cells; SP, single-positive T cells; P, proliferating; Q, quiescent). The data contain cells from all sampled developmental stages. Cells from abundant clusters are downsampled for better visualization. The reproducibility of structure is confirmed across individual samples. Unconventional T cells are in gray. (D to F) The same UMAP plot showing CD4, CD8A, and CD8B gene expression (D), CDK1 cell cycle and RAG1 recombination gene expression (E), and TCRa, productive TCRb, and nonproductive TCRβ VDJ genes (F). (G) Heat map showing differentially expressed genes across T cell differentiation pseudotime. Top: The x axis represents pseudo-temporal ordering. Gene expression levels across the pseudotime axis are maximum-normalized and smoothed. Genes are grouped by their functional categories and expression patterns. Bottom: Cell type annotation of cells aligned along the pseudotime axis. Colors are as in (C). (H) Scatterplot showing the rate of productive chain detection within cells in specific cell types (x axis) and the ratio of nonproductive/productive TCR chains detected in specific cell types (y axis). Left: TCRβ; right, TCRa. (I) Graph showing correlation-based network of transcription factors expressed by thymocytes. Nodes represent transcription factors; edge widths are proportional to the correlation coefficient between two transcription factors. Transcription factors with significant association to specific cell types are depicted in color. Node size is proportional to the significance of association to specific cell types.

To investigate the downstream T cell differentiation trajectory, we selected the T cell populations and projected them using UMAP and force-directed graph analysis (Fig. 2C, fig. S14A, and data S1), which showed a continuous trajectory of differentiating T cells. To confirm the validity of this trajectory, we overlaid hallmark genes of T cell differentiation: CD4/CD8A/CD8B genes (Fig. 2D), cell cycle (CDK1) and recombination (RAG1) genes (Fig. 2E), and fully recombined TCRαs/TCRβs (Fig. 2F) (47). The trajectory started from CD4−CD8− DN cells, which gradually express CD4 and CD8 to become CD4+CD8+ DP cells, and then transitioned through a CCR9high Tαβ(entry) stage to diverge into mature CD4+ or CD8+ SP cells (Fig. 2D). We also noted a separate lineage of cells diverging from the DN-DP junction corresponding to γδ T cell differentiation. Additional T cell lineages identified in this analysis are discussed below (Fig. 2C, gray). DN and DP cells were separated into two phases by the expression of cell cycle genes (Fig. 2E). We designated the early population with strong cell cycle signature as proliferating (P) and the later population as quiescent (Q) (Fig. 2C). Expression of VDJ recombination genes (RAG1 and RAG2)increasedfrom the lateproliferativephase and peaked at the quiescent phases. This pattern reflects the proliferation of T cells that precedes each round of recombination (48, 49).

Next, we aligned the TCR recombination data to this trajectory (Fig. 2F). In the DN stage, recombined TCRβ sequences were detected from the late P phase, which coincides with an increase in recombination signature and the expression of pre-TCRa (PTCRA) (Fig. 2G and fig. S15). The ratio of nonproductive to productive recombination events (nonproductivity score) for TCRβ was relatively higher in DN stages and dropped to a basal level as cells entered DP stages, demonstrating the impact of beta selection (Fig. 2H). Notably, the nonproductivity score for TCRβ was highest in the DN(Q) stage, which suggests that cells failing to secure a productive TCRβ recombination for the first allele undergo recombination of the other allele. In the DP stage, recombined TCRα chains were detected from P stage onward. In contrast to TCRβ, nonproductive TCRα chains were not enriched in the DP(Q) cells, but rather were depleted (Fig. 2H).

To match the transcriptome-based clustering from this study to a published protein marker-based sorting strategy, we compared our data with repository data from FACS-sorted thymocytes analyzed by microarray (50) (fig. S16). On the basis of cell cycle gene signature and marker gene expression, DN(P), DN(Q), and DP(P) stages are closely matched to CD34+CD1A+, ISP CD4+, and DP CD3− populations, respectively. Both our DP(Q)-stage and Tαβ(entry)-stage cell signatures are enriched in the bulk transcriptome data from the DP CD3+ FACS-sorted cells. The enrichment of pre-beta selection cells in DN(Q) cells matches well with the characteristics of ISP CD4+ serving as a checkpoint for beta selection (Fig. 2F and fig. S15).

To model the development of conventional αβT cells in more detail, we performed pseudotime analysis, which resulted in an ordering of cells highly consistent with known marker genes and transcription factors (Fig. 2G). In addition, we identified T cell developmental markers, including ST18 for early DN, AQP3 for DP, and TOX2 for DP-to-SP transition. To derive further insights into transcription factors that specify T cell stages and lineages, we created a correlation-based transcription factor network, after imputing gene expression (see materials and methods), which demonstrated modules of transcription factors specific for lineage commitment (Fig. 2I).

Development of Tregs and unconventional T cells

In addition to conventional CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, which constitute the majority of T cells in the developing thymus, our data identified multiple unconventional T cell types, which were grouped by the expression of signature marker genes (Fig. 2I and Fig. 3, A and B). Unconventional T cells have been suggested to require agonist selection for development (3). In support of this, we observed a lower ratio of nonproductive TCR chains for these cells, implying that they reside longer in the thymus than do conventional T cells (Fig. 3C).

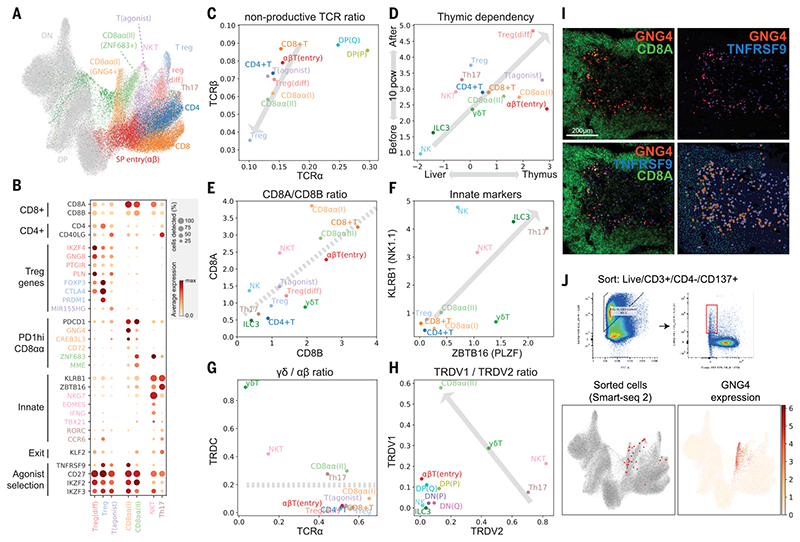

Fig. 3. Identification of GNG4+ CD8αα T cells in the thymic medulla.

(A) UMAP visualization of mature T cell populations in the thymus. Axes and coordinates are as in Fig. 2C. (The cell annotation color scheme used here is maintained throughout this figure.) (B) Dot plot showing marker gene expression for the mature T cell types. Genes are stratified according to associated cell types or functional relationship. (C) Scatterplot showing the ratio of nonproductive/productive TCR chains detected in specific cell types in TCRa chain (x axis) and TCRβ chain (y axis). The gray arrow indicates a trendline for decreasing nonproductive TCR chain ratio in unconventional versus conventional T cells. (D) Scatterplot showing the relative abundance of each cell type between fetal liver and thymus (x axis) and before and after thymic maturation (delimited at 10 PCW) (y axis). Gray arrow indicates trendline for increasing thymic dependency. (E to H) Scatterplots comparing the characteristics of unconventional T cells based on CD8A versus CD8B expression levels (E), KLRB1 versus ZBTB16 expression levels (F), TCRa productive chain versus TRDC detection ratio (G), and TRDV1 versus TRDV2 expression levels (H). Gray arrows or lines are used to set boundaries between groups [(E), (G), (H)] or to indicate the trend of innate marker gene expression (F). (I) RNA smFISH showing GNG4, TNFRSF9, and CD8A in a 15 PCW thymus. Lower right panel shows detected spots from the image on top of the tissue structure based on 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) signal. Color scheme for spots is the same as in the image. (J) FACS gating strategy to isolate CD8αα(I) cells (live/CD3+/CD4^/CD137+) and Smart-seq2 validation of FACS-isolated cells projected to the UMAP presentation of total mature T cells from the discovery dataset (lower left). GNG4 expression pattern is overlaid onto the same UMAP plot (lower right).

Next, we investigated whether development of these unconventional T cells is dependent on the thymus. We reasoned that if a population is thymus-dependent, it would accumulate after thymic maturation (~10 PCW) and would be enriched in the thymus relative to other hematopoietic organs. Consistent with this idea, we found that all unconventional T cells were enriched in the thymus, particularly after thymic maturation, which suggests that they are thymus-derived (Fig. 3D).

Tregs were the most abundant unconventional T cells in the thymus. There was a clear differentiation trajectory connecting αβT cells and Tregs. We defined the connecting population as differentiating Tregs (Treg(diff)) (Fig. 3A). Relative to canonical Tregs, Treg(diff) cells displayed lower expression of FOXP3 and CTLA4 and higher expression of IKZF4, GNG8, and PTGIR (Fig. 3B). These genes have been associated with autoimmunity and Treg differentiation (51).

We also noted another population that shares expression modules with Treg(diff) cells, but not with terminally differentiated Treg cells. We named this population—defined by the expression of a noncoding RNA, MIR155HG—as T(agonist) (Fig. 3, A and B). Interestingly, this population expressed IL2RA but has low FOXP3 mRNA. These features are similar to those of a previously described mouse CD25+FOXP3− Treg progenitor (52) (fig. S17). Further analysis showed that the signature of two Treg progenitors (CD25+ and FOXP3l? Treg progenitors) defined in previous studies are expressed at a higher level in T(agonist) and Treg(diff) populations, respectively (fig. S17B). The UMAP and force-directed graph showed that both of these populations are linked to mature Tregs (fig. S17A), suggesting the possibility of two Treg progenitors in the human thymus.

Other unconventional T cell populations included CD8αα+T cells, NKT-like cells, and TH17-like cells (Fig. 3B). There were three distinct populations of CD8αα+ Tcells: GNG4+ CD8αα+ T(I) cells, ZNF683+ CD8αα+ T(II) cells, and a CD8αα+ NKT-like population marked by EOMES (Fig. 3E). GNG4+CD8αα+ T(I) cells and ZNF683+ CD8αα+ T(II) cells shared PDCD1 expression at an early stage, which decreased in their terminally differentiated state (fig. S14B). Whereas GNG4+ CD8αα+ T(I) cells display a clear trajectory diverging from late DP stage (αβTSP entry cells), ZNF683+CD8αα+ T(II) cells have a mixed αβ and γδ T cell signatures, and sit next to both GNG4+CD8αα+ T(I) cells and γδ T cells (Fig. 3A and fig. S14B).

EOMES+ NKT-like cells have a shared gene expression profile with NK cells (NKG7, IFNG, TBX21) and are enriched in γδ T cells; that is, their TCRs are γδ rather than αβ (Fig. 3B and fig. S14B). Interestingly, previously described gene sets from bulk RNA sequencing of human thymic or cord blood CD8αα+ T cells can now be deconvoluted into our three CD8αα+ T cell populations using signature genes. These results suggest that our three CD8αα+ T cell populations are present in these previously published thymic and cord blood samples at different frequencies, as shown in fig. S18 (53).

Finally, we found another fetal-specific cell cluster that we named “TH17-like cells” based on CD4, CD40LG, RORC, and CCR6 expression (Fig. 3B). TH17-like cells and NKT-like cells expressed KLRB1 and ZBTB16, which are hallmarks of innate lymphocytes (54, 55) (Fig. 3F).

As described above, many cell clusters contained a mixed signature of αβ and γδ T cells, meaning that a single cluster contained some cells with αβ TCR expression and others with γδ TCR expression. To classify cells into αβ and γδ T cells, we analyzed the TCRα/δ loci, where recombination of TCRα excises TCRδ, making the two mutually exclusive (Fig. 3G). This clearly showed that γδ Tcells diverging between the DN and DP populations are pure γδ T cells. In contrast, CD8αα+ T(II), NKT-like, and TH17-like cells included both αβ and γδ T cell populations, suggesting transcriptomic convergence of some αβ and γδ T cells.

Interestingly, TRDV1 and TRDV2, the two most frequently used TCRδ Vgenesinhuman, displayed clear usage bias: TRDV2 was used at an earlier stage (DN), whereas TRDV1 was used exclusively in later T cell development [DP(Q) and αβT entry] (Fig. 3H). On the basis of this pattern, we can attribute the stage of origin of γδ T cell populations, which suggests that CD8αα+ T(II) cells are derived from the late DP stage, whereas NKT-like/TH17-like cells arise from earlier stages (Fig. 3H).

Discovery and characterization of GNG4 + CD8αα T cells in the thymic medulla

Having identified unconventional T cells and their trajectory of origin within thymic T cell development, we focused on our newly identified GNG4+CD8αα+ T(I) cells, as they have a unique gene expression profile (GNG4, CREB3L3, and CD72). This is in contrast to CD8αα+ T(II) cells, which express known markers of CD8αα+ T cells such as ZNF683 and MME (53). Moreover, the expression level of KLF2, a regulator of thymic emigration, was extremely low in CD8αα+ T(I) cells, which suggests that they may be thymic-resident (Fig. 3B). To locate and validate CD8αα+ T(I) cells in situ, we performed RNA smFISH targeting GNG4 in fetal thymus tissue sections. The GNG4 RNA probe identified a distinct group of cells enriched in the thymic medulla, and colocalized with CD8A RNA (Fig. 3I). TNFRSF9 (CD137) is a marker shared between CD8αα+ T(I) cells and Tregs. When tested in situ, GNG4+ cells were a subset of TNFRSF9+ cells, further confirming the validity of the localization pattern.

Because CD137 is a surface marker of both CD8αα+ T(I) cells and Tregs, we enriched these cells using this marker (fig. S19). Further refinement using CD3+CD137+CD4− FACS sorting allowed us to specifically enrich for CD8αα+ T(I) cells and confirm their identity by Smart-seq2 scRNA sequencing, thereby providing additional transcriptomic phenotyping of these cells (Fig. 3J).

To compare our findings in human thymus to mouse thymus, we generated a comprehensive mouse thymus single-cell atlas of postnatal murine samples (4, 8, or 24 weeks old) and combined these data with a published prenatal mouse thymus scRNA-seq dataset (14) (fig. S20). Integrative analysis of mature T cells from human and mouse showed that cell states are well mixed across species (fig. S21). This analysis showed that GNG4+ CD8αα+ T(I) cells in humans are most similar to the mouse intraepithelial lymphocyte precursor type A (IELpA) cells (56) (fig. S21), sharing expression of HIVEP3, NR4A3, PDCD1,and TNFRSF9 (fig. S22). However, there were also highly differentially expressed genes between them, including GNG4 and XCL1 in human and ZEB2 and CLDN10 in mouse, suggesting a potential difference in function (fig. S23). Moreover, human CD8αα+ T(I) cells fully mature into a CD8Ahigh/CD8Blow phenotype, whereas IELpA cells become triple negative (CD8Alow CD8BlowCD4low) cells (fig. S23). This shows that human and mouse TNFRSF9high agonist-selected cells in the thymus take on distinct transcriptional characteristics.

Recruitment and activation of DCs for thymocyte selection

Selection of T cells is coordinated by specialized TECs and DCs. We identified three previously well-characterized thymic DC subtypes: DC1 (XCR1+CLEC9A+), DC2 (SIRPA+CLEC10A+), and pDC (IL3RA+CLEC4C+)(6, 57, 58). We also identified a population that was previously incompletely described, which we call “activated DCs” (aDCs), characterized by LAMP3 and CCR7 expression (Fig. 4, A and B) (59, 60). aDCs expressed a high level of chemokines and costimulatory molecules, together with transcription factors such as AIRE and FOXD4, which we validated in situ (Fig. 4B and fig. S24); these findings suggest that they may correspond to the previously described AIRE+CCR7+ DCs in human tonsils and thymus (61).

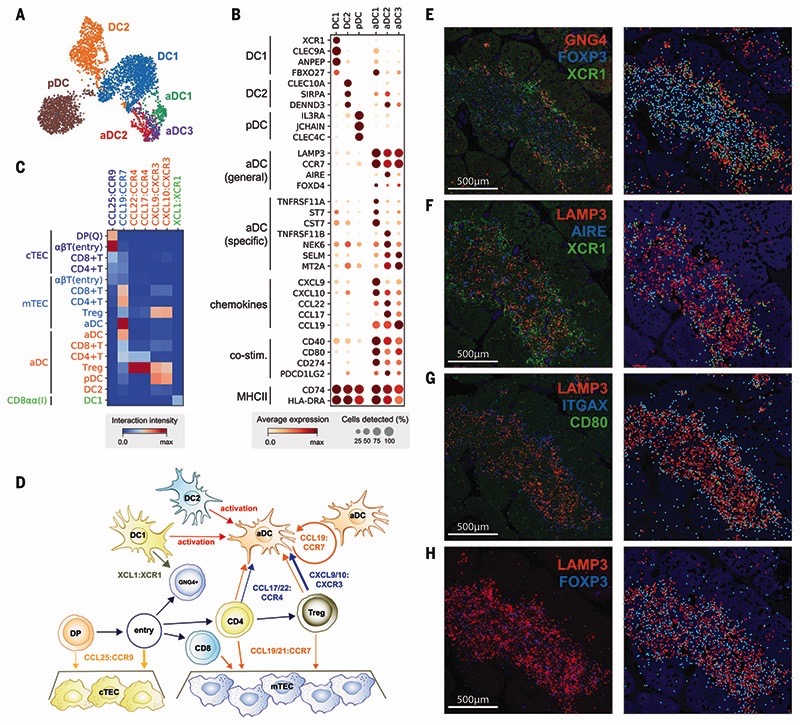

Fig. 4. Recruitment and activation of dendritic cells for thymocyte selection.

(A and B) UMAP visualization of thymic DC populations (A) and dot plot of their marker genes (B). (C) Heat map of chemokine interactions among T cells, DCs, and TECs, where the chemokine is expressed by the outside cell type and the cognate receptor by the inside cell type. (D) Schematic model summarizing the interactions of TECs, DCs, and T cells. The ligand is secreted by the cell at the beginning of an arrow, and the receptor is expressed by the cell at the end of that arrow. (E) Left: RNA smFISH detection of GNG4, XCR1, and FOXP3 in 15 PCW thymus. Right: Computationally detected spots are shown as solid circles over the tissue structure based on DAPI signal. Color schemes for circles are the same as in the image. (F to H) Sequential slide sections from the same sample are stained for the detection of LAMP3, AIRE, and XCR1 (F), LAMP3, ITGAX, and CD80 (G), and LAMP3 and FOXP3 (H). Spot detection and representation are as in (E). Data are representative of two experiments.

Interestingly, our single-cell data revealed three subsets within the aDC group, identified by distinct gene expression profiles: aDC1, aDC2, and aDC3 (Fig. 4, A and B). aDC1 and aDC2 subtypes shared several marker genes with DC1 and DC2, respectively. To systematically compare aDC subtypes to canonical DCs, we calculated an identity score for each DC population by summarizing marker gene expression. This demonstrated a clear relationship between aDC1-DC1 and aDC2-DC2 pairs, which suggests that each aDC subtype derives from a distinct DC population (fig S25). Interestingly, aDC1 and aDC2 displayed distinct patterns of chemokine expression, suggesting functional diversification of these aDCs (Fig. 4B). Moreover, aDC3 cells had decreased major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and costimulatory molecule expression relative to other aDC subsets, which may reflect a postactivation DC state.

Having identified two canonical TECs and a variety of DC subsets, we used CellPhoneDB analysis to identify specific interactions between these antigen-presenting cells and differentiating T cells (35). We focused on interactions mediated by chemokines, which enable cell migration and anatomical colocalization (Fig. 4C). This demonstrated the relay of differentiating T cells from the cortex to the medulla, which is orchestrated by CCL25:CCR9 and CCL19/21:CCR7 interactions between cTEC/mTEC and DP/SP T cells, respectively (62). Interestingly, aDCs expressed CCR7, together with CCL19,enabling attraction to and recruitment of T cells into the thymic medulla. Moreover, they strongly expressed the chemo-kines CCL17 and CCL22, whose receptor CCR4 was enriched in CD4+ T cells and particularly Tregs. aDCs also potentially recruit other DCs and mature Tregs via CXCL9/10:CXCR3 interactions and are able to provide a strong costimulatory signal, which suggests a role in Treg generation. We also noted that GNG4+CD8αα+ T(I) cells expressed XCL1, which may be involved in the recruitment of XCR1-expressing DC1 cells (63). Our analysis shows that XCL1 is expressed most highly by CD8aa+ T(I) cells and at a lower level by NK cells (fig. S26). The location of CD8αα+ T(I) cells in the perimedul-lary region suggests a potential relay of signals from CD8aa+ T(I) cells to recruit XCR1+ DC1 cells into the medulla, where these cells are activated and up-regulate CCR7 (Fig. 4D).

To confirm our in silico predictions, we performed smFISH to identify the anatomical location of CD8αα+ T(I) cells (GNG4), DC1s (XCR1), aDCs (LAMP3, CD80), and Tregs (FOXP3). A generic marker of nonactivated DCs (LTGAX) and mTECs (AIRE) was also used to provide a reference for the organ structure. Imaging of consecutive sections of fetal thymus (15 PCW) revealed the zonation of CD8αα+ T(I) cells, DC1s, and nonactivated DCs located in the perimedullary region, and aDCs and Tregs enriched in the center of the medulla (Fig. 4, E to H). All localization patterns are supportive of our in silico model, demonstrating the power of single-cell transcriptomics coupled with CellPhoneDB predictions.

Bias in human TCR repertoire formation and selection

Because our data featured detailed T cell trajectories combined with single-cell resolution TCR sequences, it provided an opportunity to investigate the kinetics of TCR recombination. TCR chains detected from the TCR-enriched 5’ sequencing libraries were filtered for fulllength recombinants and were associated with our cell type annotation. This allowed us to analyze patterns in TCR repertoire formation and selection (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5. Intrinsic bias in human TCR repertoire formation and selection.

(A) Heat map showing the proportion of each TCRβ V, D, and J gene segment present at progressive stages of T cell development. Gene segments are positioned according to genomic location. (B) Same scheme as in (A) applied to TCRα V and J gene segments. Although there is a usage bias of segments at the beginning of development, segments are evenly used by the late developmental stages, indicating progressive recombination leading to even usage of segments. (C and D) Schematics illustrating a hypothetical chromatin loop that may explain genomic location bias in recombination of TCRβ locus (C) and the mechanism of progressive recombination of TCRα locus leading to even usage of segments (D). (E) Principal components analysis plots showing TRBV or TRAV and TRAJ gene usage pattern in different T cell types. Arrows depict T cell developmental order. For TRBV, there is a strong effect from beta selection, after which point the CD4+ and CD8+ repertoires diverge. The development for TRAV+ TRAJ is more progressive, with stepwise divergence into the CD4+ and CD8+ repertoires. (F) Relative usage of TCRα V and J gene segments according to cell type. The z-score for each segment is calculated from the distribution of normalized proportions stratified by the cell type and sample. P value is calculated by comparing z-scores in CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells using t test, and false discovery rate (FDR) is calculated using Benjamini-Hochberg correction: *P < 0.05, **FDR < 10%. Gene names and asterisks are colored by significant enrichment in CD4+ T cells (blue) or CD8+ T cells (orange).

For TCRβ, we observed a strong bias in VDJ gene usage that persisted from the initiation of recombination (DN cells) to the mature T cell stage (Fig. 5A). This bias is not explained by recombination signal sequence (RSS) score (fig. S27). The bias does correlate well with genomic position (fig. S27), and this is consistent with a looping structure of the locus, which has been observed in the mouse (Fig. 5C) (64). However, the V gene usage bias that we observe in human is not found in mouse (25). We also observed a preferential association of D2 genes with J2 genes, whereas D1 genes can recombine with J1 and J2 genes with similar frequency (fig. S28). There was no clear association between TCRβ V-D or V-J pairs (fig. S28A).

Although the initial recombination pattern largely shapes the repertoire, selection also contributes to the preference in TCRβ repertoire. We observed that several TRBV genes were depleted or enriched after beta selection (DP cells) relative to before beta selection (DN cells). This suggests that there are germline-encoded differences between the different Vβ genes’ ability to respond to peptide-MHC (pMHC) stimulation (fig. S29A). This result is in line with the molecular finding that Vβ makes the most contacts with pMHC molecule versus DJ (and also Vα) (65).

For the TCRα locus, we found a clear association between developmental timing and V-J pairing, as previously described (66): Proximal pairs were recombined first, followed by recombination of distal pairs (Fig. 5B), which in turn restricted the pairing between V and J genes (fig. S28B). This provides direct evidence for progressive recombination of the TCRα locus (Fig. 5D). Notably, proximal pairs were depleted in mature T cells relative to DP cells, showing a further bias in the positive selection step (fig. S28B).

To investigate whether differential TCR repertoire bias exists between cell types, we compared the TCR repertoire of different cell types by running a principal components analysis (Fig. 5E). Notably, we observed a clear separation of CD8+ Tcells and other cell types. The trend was consistent in all individual donor samples. Statistical testing of the difference in odds ratios identified several TCR genes responsible for this phenomenon (fig. S29B). The observed trend was largely similar to that seen in naïve CD4+/CD8+ T cells isolated from peripheral blood (22, 23). Notably, relative to other cell types, the TRAV-TRAJ repertoire of CD8+ T cells was biased toward distal V-J pairs (Fig. 5F). Considering that distal repertoires are generated at a later stage of progressive TCRa recombination, this might be due to slower or less efficient commitment toward the CD8+ T lineage (Fig. 5D). There was also a slight bias toward proximal V-J pairs for CD8αα+ T(I) cells that was much more evident in the postnatal thymic sample compared to fetal samples (fig. S29C) (53).

Discussion

We reconstructed the trajectory of human conventional and unconventional T cell differentiation combined with TCR repertoire information, which revealed a bias in the TCR repertoire of mature conventional T cells. Because TCR repertoire bias predisposes our reactivity to diverse pMHC combinations, this may have profound implications for how we respond to antigenic challenges.

Our analysis of the thymic microenvironment revealed the complexity of cell types constituting the thymus, as well as the breadth of interactions between stromal cells and innate immune cells to coordinate thymic development to support T cell differentiation. The intercellular communication network that we describe between thymocytes and supporting cells can be used to enhance in vitro culture systems to generate T cells, and will influence future T cell therapeutic engineering strategies.

Materials and methods

Tissue acquisition and processing

All tissue samples used for this study were obtained with written informed consent from all participants in accordance with the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki 2000 from multiple centers. All tissues were processed immediately after isolation using consistent protocols with variation in enzymatic digestion strength. Tissue was transferred to a sterile 10-mm2 tissue culture dish and cut into segments (<1 mm3) before being transferred to a 50-ml conical tube. For mild digestion, tissues were digested with collagenase type IV (1.6 mg/ml, Worthington) in RPMI (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), penicillin (100 U/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C with intermittent shaking. For stringent digestion, tissue was digested with Liberase (0.2 mg/ml, Roche)/0.125 KU DNase1 (Sigma-Aldrich)/10 mM HEPES in RPMI for 30 min at 37°C with intermittent shaking. The dissociated cells were separated and remaining undigested tissue were digested again with fresh media. This procedure was repeated until the tissue was completely dissociated. Digested tissue was passed through a 100-μm filter, and cells collected by centrifugation (500g for 5 min at 4°C). Cells were treated with 1× red blood cell [RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience)] for 5 min at room temperature and washed once with flow buffer [PBS containing 5% (v/v) FBS and 2 mM EDTA] prior to cell counting.

Single-cell RNA sequencing experiment

For FACS sorting of isolated thymus cells, dissociated cells were stained with a panel of antibodies prior to sorting based on CD45 or CD3 expression gate. Enrichment of EpCAM-positive cells was performed using CD326 (EpCAM) microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-061-101) according to manufacturer’s protocol. CD45 depleted cells were obtained using CD45 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130045-801) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cell number and viability were checked after the enrichment to ensure that no significant cell death has been caused by the process.

For the droplet-encapsulation scRNA-seq experiments, 8000 live, single, CD45+ or CD45− FACS-isolated cells or MACS-enriched cells were loaded on to each of the Chromium Controller (10x Genomics). Single-cell cDNA synthesis, amplification, and sequencing libraries were generated using the Single Cell 3’ and 5’ Reagent Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries from up to eight loaded channels were multiplexed together and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000. The libraries were distributed over eight lanes per flow cell and sequenced using the following parameters: Read1: 26 cycles, i7: 8 cycles, i5: 0 cycles; Read2: 98 cycles to generate 75-bp paired-end reads. For the plate-based scRNA-seq experiments, a slightly modified Smart-Seq2 protocol was used. After cDNA generation, libraries were prepared (384 cells per library) using the Illumina Nextera XT kit. Index v2 sets A, B, C, and D were used per library to barcode each cell for multiplexing. Each library was sequenced (384 cells) per lane at a sequencing depth of 1 to 2 million reads per cell on HiSeq 4000 using v4 SBS chemistry to create 75-bp paired-end reads.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data analysis

Droplet-based sequencing data were aligned and quantified using the Cell Ranger SingleCell Software Suite (version 2.0.2 for 3’ chemistry and version 2.1.0 for 5’ chemistry, 10x Genomics Inc.) using the GRCh38 human reference genome (official Cell Ranger reference, version 1.2.0). Cells with fewer than 2000 UMI counts and 500 detected genes were considered as empty droplets and removed from the dataset. Cells with more than 7000 detected genes were considered as potential doublets and removed from the dataset.

Smart-seq2 sequencing data were aligned with STAR (version 2.5.1b), using the STAR index and annotation from the same reference as the 10x data. Gene-specific read counts were calculated using htseq-count (version 0.10.0). Scanpy (version 1.3.4) python package was used to load the cell-gene count matrix and perform downstream analysis. Doublet detection, clustering, annotation, batch alignment, trajectory analysis, cell-cell interaction, and repertoire analysis is performed using the tools in Scanpy package complemented with some custom codes.

RNA smFISH

Samples were fixed in 10% NBF, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in paraffin wax. Samples (5 μm) were cut, baked at 60°C for 1 hour, and processed using standard pre-treatment conditions, as per the RNAscope multiplex fluorescent reagent kit version 2 assay protocol (manual) or the RNAscope 2.5 LS fluorescent multiplex assay (automated). TSA-plus fluorescein, Cy3, and Cy5 fluorophores were used at 1:1500 dilution for the manual assay, or 1:300 dilution for the automated assay. Slides were imaged on different microscopes: Hamamatsu Nanozoomer S60 or 3DHistech Pannoramic MIDI. Stained sections were also imaged with a Perkin Elmer Opera Phenix High-Content Screening System, in confocal mode with 1 μm z-step size, using 20× (NA 0.16, 0.299 μm/pixel) and 40× (NA 1.1,0.149 μm/pixel) water-immersion objectives.

Supplementary Material

Introduction

The thymus is the critical organ for T cell development and T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire formation, which shapes the landscape of adaptive immunity. T cell development in the thymus is spatially coordinated, and this process is orchestrated by diverse cell types constituting the thymic microenvironment. Although the thymus has been extensively studied using diverse animal models, human immunity cannot be understood without a detailed atlas of the human thymus.

Rationale

To provide a comprehensive atlas of thymic cells across human life, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) using dissociated cells from human thymus during development, childhood, and adult life. We sampled 15 embryonic and fetal thymi spanning thymic developmental stages between 7 and 17 post-conception weeks, as well as nine postnatal thymi from pediatric and adult individuals. Diverse sorting schemes were applied to increase the coverage on underrepresented cell populations. Using the marker genes obtained from single-cell transcriptomes, we spatially localized cell states by single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH). To provide a systematic comparison between human and mouse, we also generated single-cell data on postnatal mouse thymi and combined this with preexisting mouse datasets. Finally, to investigate the bias in the recombination and selection of human TCR repertoires, we enriched the TCR sequences for single-cell library generation.

Results

We identified more than 50 different cell states in the human thymus. Human thymus cell states dynamically change in abundance and gene expression profiles across development and during pediatric and adult life. We identified novel subpopulations of human thymic fibroblasts and epithelial cells and located them in situ. We computationally predicted the trajectory of human T cell development from early progenitors in the hematopoietic fetal liver into diverse mature T cell types. Using this trajectory, we constructed a framework of putative transcription factors driving T cell fate determination. Among thymic unconventional T cells, we noted a distinct subset of CD8αα+ T cells, which is marked by GNG4 expression and located in the perimedullary region of the thymus. This subset expressed high levels of XCL1 and colocalized with XCR1+ dendritic cells. Comparison of human and mouse thymic cells revealed diverget gene expression profiles of these unconventional T cell types. Finally, we identified a strong bias in human VDJ usage shaped by recombination and multiple rounds of selection, including a TCRα V-J bias for CD8+ T cells.

Conclusion

Our single-cell transcriptome profile of the thymus across the human lifetime and across species provides a high-resolution census of T cell development within the native tissue microenvironment. Systematic comparison between the human and mouse thymus highlights human-specific cell states and gene expression signatures. Our detailed cellular network of the thymic niche for T cell development will aid the establishment of in vitro organoid culture models that faithfully recapitulate human in vivo thymic tissue.

Constructing the human thymus cell atlas.

We analyzed human thymic cells across development and postnatal life using scRNA-seq and spatial methods to delineate the diversity of thymic-derived T cells and the localization of cells constituting the thymus microenvironment. With T cell development trajectory reconstituted at singlecell resolution combined with TCR sequence, we investigated the bias in the VDJ recombination and selection of human TCR repertoires. Finally, we provide a systematic comparison between human and mouse thymic cell atlases.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Sanger Flow Cytometry Facility, Newcastle University Flow Cytometry Core Facility, Sanger Cellular Generation and Phenotyping (CGaP) Core Facility, and Sanger Core Sequencing pipeline for support with sample processing and sequencing library preparation. We thank the MRC/Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Newcastle Molecular Pathology Node for support on paraffin embedding fetal tissues; J. Eliasova for graphical images, J. Choi for helpful discussions, and S. Aldridge for editing the manuscript. The human embryonic and fetal material was provided by the Joint MRC/Wellcome (MR/R006237/1) Human Developmental Biology Resource (www.hdbr.org). The material from the deceased organ donor was provided by the Cambridge Biorepository for Translational Medicine. Pediatric thymus material was provided by Ghent University Hospital. We are grateful to the donors and donor families for granting access to the tissue samples. This publication is part of the Human Cell Atlas: www.humancellatlas.org/publications.

Funding

Supported by Wellcome Human Cell Atlas Strategic Science Support (WT211276/Z/18/Z) and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZF2019-002445); Wellcome (WT206194), ERC Consolidator (no. 646794), and EU MRG-Grammar awards (S.A.T.); Wellcome (WT107931/Z/15/Z), the Lister Institute for Preventive Medicine and NIHR and Newcastle-Biomedical Research Centre (M.H.); Research Foundation Flanders (FWO grant G053816N) and Ghent University Special Research Fund (BOF18-GOA-024) (T.T.); an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship (J.-E.P.); the Wellcome Trust under grants 203828/Z/16/A and 203828/Z/16/Z (D.J.K.); and the European Research Council (ERC-Stg 639429), the Rosetrees Trust (M362; M362-F1), the UCL Therapeutic Acceleration Support Fund, and the GOSH BRC (P.B.). R.A.B. is an NIHR Senior Investigator and is also supported by NIHR funding of the Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre. Cambridge fetal tissue was collected in part from funding from the WT MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.-E.P., S.A.T., M.H., and T.T. designed the experiments; J.-E.P., R.A.B., D.-M.P., E.S., M.L., C.D.C., J.R.F., N.V., K.T.M., I.G., L.B., D.C., F.D., and X.H. performed sampling and library prep with help from S. W., D.M., A.Fu., A.Fi., L.M., G.R., D.D., S.L., D.H., K.S.-P., and R. V.-T.; J.-E.P., D.J.K., K.P., M.L., C.D.C., and V.R.K. analyzed the data; J.-E.P., C.D.C., E.T., O.B., K.R., A.W.-C., R.A.B., and R.R. performed validation experiments; J.-E.P., C.D.C., S.A.T., M.H., and T. T. wrote the manuscript with contributions from R.A.B., K.B.M., Y.S., M.R.C., P.B., S.B., R.V.-T., K.S.-P., and D.J.K. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests: J.-E.P. and S.A.T. are inventors on a patent application (GB1918902.6) submitted by Genome Research Limited that covers a defined set of transcription factors.

Data and materials availability

All sequencing data have been deposited to ArrayExpress (accession number E-MTAB-8581) and can be accessed online through a web portal (https://developmentcellatlas.ncl.ac.uk). All codes used for data analysis are available from Zenodo repository (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3572422).

References and Notes

- 1.Palmer S, Albergante L, Blackburn CC, Newman TJ. Thymic involution and rising disease incidence with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:1883–1888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714478115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch HE, et al. Thymic involution and immune reconstitution. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:366–373. doi: 10.1016/Jit.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stritesky GL, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Selection of self-reactive T cells in the thymus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:95–114. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sánchez MJ, et al. Putative prethymic T cell precursors within the early human embryonic liver: A molecular and functional analysis. J Exp Med. 1993;177:19–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun L, et al. FSP1+fibroblast subpopulation is essential for the maintenance and regeneration of medullary thymic epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14871. doi: 10.1038/srep14871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu L, Shortman K. Heterogeneity of thymic dendritic cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:304–312. doi: 10.1016/Jsmim.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson G, Takahama Y. Thymic epithelial cells: Working class heroes for T cell development and repertoire selection. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:256–263. doi: 10.1016/Jit.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y-J. A unified theory of central tolerance in the thymus. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:215–221. doi: 10.1016/Jit.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gameiro J, Nagib P, Verinaud L. The thymus microenvironment in regulating thymocyte differentiation. Cell Adhes Migr. 2010;4:382–390. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.3.11789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkinson WE, Rossi SW, Parnell SM, Jenkinson EJ, Anderson G. PDGFRα-expressing mesenchyme regulates thymus growth and the availability of intrathymic niches. Blood. 2007;109:954–960. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inglesfield S, Cosway EJ, Jenkinson WE, Anderson G. Rethinking Thymic Tolerance: Lessons from Mice. Trends Immunol. 2019;40:279–291. doi: 10.1016/Jit.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller JFAP. The golden anniversary of the thymus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:489–495. doi: 10.1038/nri2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon J, Manley NR. Mechanisms of thymus organogenesis and morphogenesis. Development. 2011;138:3865–3878. doi: 10.1242/dev059998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kernfeld EM, et al. A Single-Cell Transcriptomic Atlas of Thymus Organogenesis Resolves Cell Types and Developmental Maturation. Immunity. 2018;48:1258–1270.:e6. doi: 10.1016/Jimmuni.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bornstein C, et al. Single-cell mapping of the thymic stroma identifies IL-25-producing tuft epithelial cells. Nature. 2018;559:622–626. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller CN, et al. Thymic tuft cells promote an IL-4-enriched medulla and shape thymocyte development. Nature. 2018;559:627–631. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0345-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mestas J, Hughes CCW. Of mice and not men: Differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol. 2004;172:2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farley AM, et al. Dynamics of thymus organogenesis and colonization in early human development. Development. 2013;140:2015–2026. doi: 10.1242/dev087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar BV, Connors TJ, Farber DL. Human T Cell Development, Localization, and Function throughout Life. Immunity. 2018;48:202–213. doi: 10.1016/Jimmuni.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikolich-Žugich J, Slifka MK, Messaoudi I. The many important facets of T cell repertoire diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:123–132. doi: 10.1038/nri1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jores R, Meo T. Few V gene segments dominate the T cell receptor ß-chain repertoire of the human thymus. J Immunol. 1993;151:6110–6122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter JA, et al. T cell receptor αβ chain pairing is associated with CD4+ and CD8+ lineage specification. bioRxiv. 2018 Apr 3;:293852. [preprint] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klarenbeek PL, et al. Somatic Variation of T cell Receptor Genes Strongly Associate with HLA Class Restriction. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0140815. doi: 10.1371/journalpone.0140815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warren RL, et al. Exhaustive T cell repertoire sequencing of human peripheral blood samples reveals signatures of antigen selection and a directly measured repertoire size of at least 1 million clonotypes. Genome Res. 2011;21:790–797. doi: 10.1101/gr.115428.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gopalakrishnan S, et al. Unifying model for molecular determinants of the preselection Vß repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E3206–E3215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304048110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polański K, et al. BBKNN: Fast Batch Alignment of Single Cell Transcriptomes. Bioinformatics. 2019:btz625. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen S, et al. Collectin 11 (CL-11, CL-K1) is a MASP-1/3-associated plasma collectin with microbial-binding activity. J Immunol. 2010;185:6096–6104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol1002185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sitnik KM, et al. Mesenchymal cells regulate retinoic acid receptor-dependent cortical thymic epithelial cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2012;188:4801–4809. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol1200358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu C, Giraudo E. The role of semaphorins and their receptors in vascular development and cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1306–1316. doi: 10.1016/Jyexcr.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garchon HJ, Djabiri F, Viard JP, Gajdos P, Bach JF. Involvement of human muscle acetylcholine receptor α-subunit gene (CHRNA) in susceptibility to myasthenia gravis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4668–4672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mesnard-Rouiller L, Bismuth J, Wakkach A, Poёa-Guyon S, Berrih-Aknin S. Thymic myoid cells express high levels of muscle genes. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;148:97–105. doi: 10.1016/Jjneuroim.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zóttowska A, et al. Myoid cells and neuroendocrine markers in myasthenic thymuses. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 1998;46:253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patil VS, et al. Precursors of human CD4+cytotoxic T lymphocytes identified by single-cell transcriptome analysis. Sci Immunol. 2018;3:eaan8664. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aan8664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopes N, Sergé A, Ferrier P, Irla M. Thymic Crosstalk Coordinates Medulla Organization and T cell Tolerance Induction. Front Immunol. 2015;6:365. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vento-Tormo R, et al. Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal-fetal interface in humans. Nature. 2018;563:347–353. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0698-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elewaut D, Ware CF. The unconventional role of LTαß in T cell differentiation. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:169–175. doi: 10.1016/Jit.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi SW, et al. RANK signals from CD4+3− inducer cells regulate development of Aire-expressing epithelial cells in the thymic medulla. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1267–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Revest JM, Suniara RK, Kerr K, Owen JJ, Dickson C. Development of the thymus requires signaling through the fibroblast growth factor receptor R2-IIIb. J Immunol. 2001;167:1954–1961. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol167.4.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.García-León MJ, Fuentes P, de la Pompa JL, Toribio ML. Dynamic regulation of NOTCH1 activation and Notch ligand expression in human thymus development. Development. 2018;145:dev165597. doi: 10.1242/dev165597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Desanti GE, et al. Developmentally regulated availability of RANKL and CD40 ligand reveals distinct mechanisms of fetal and adult cross-talk in the thymus medulla. J Immunol. 2012;189:5519–5526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol1201815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cosway EJ, et al. Redefining thymus medulla specialization for central tolerance. J Exp Med. 2017;214:3183–3195. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van de Walle I, et al. Jagged2 acts as a Delta-like Notch ligand during early hematopoietic cell fate decisions. Blood. 2011;117:4449–4459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van de Walle I, et al. Specific Notch receptor-ligand interactions control human TCR-αß/γδ development by inducing differential Notch signal strength. J Exp Med. 2013;210:683–697. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popescu D-M, et al. Decoding human fetal liver haematopoiesis. Nature. 2019;574:365–371. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1652-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng Y, et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Resolves Spatiotemporal Development of Pre-thymic Lymphoid Progenitors and Thymus Organogenesis in Human Embryos. Immunity. 2019;51:930–948.:e6. doi: 10.1016/Jimmuni.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pellin D, et al. A comprehensive single cell transcriptional landscape of human hematopoietic progenitors. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2395. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah DK, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. An overview of the intrathymic intricacies of T cell development. J Immunol. 2014;192:4017–4023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol1302259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrie HT, Tourigny M, Burtrum DB, Livak F. Precursor thymocyte proliferation and differentiation are controlled by signals unrelated to the pre-TCR. J Immunol. 2000;165:3094–3098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol165.6.3094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tourigny MR, Mazel S, Burtrum DB, Petrie HT. T cell receptor (TCR)-ß gene recombination: Dissociation from cell cycle regulation and developmental progression during T cell ontogeny. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1549–1556. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dik WA, et al. New insights on human T cell development by quantitative T cell receptor gene rearrangement studies and gene expression profiling. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1715–1723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmiedel BJ, et al. Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on Human Immune Cell Gene Expression. Cell. 2018;175:1701–1715.:e16. doi: 10.1016/Jcell2018.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owen DL, et al. Thymic regulatory T cells arise via two distinct developmental programs. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:195–205. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0289-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verstichel G, et al. The checkpoint for agonist selection precedes conventional selection in human thymus. Sci Immunol. 2017;2:eaah4232. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunolaah4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fergusson JR, Fleming VM, Klenerman P. CD161-expressing human T cells. Front Immunol. 2011;2:36. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alonzo ES, Sant’Angelo DB. Development of PLZF-expressing innate T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:220–227. doi: 10.1016/Jcoi.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruscher R, Kummer RL, Lee YJ, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. CD8αα intraepithelial lymphocytes arise from two main thymic precursors. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:771–779. doi: 10.1038/ni.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oh J, Shin J-S. The Role of Dendritic Cells in Central Tolerance. Immune Netw. 2015;15:111–120. doi: 10.4110/in2015.15.3.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villani A-C, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science. 2017;356:eaah4573. doi: 10.1126/science.aah4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe N, et al. Hassall’s corpuscles instruct dendritic cells to induce CD4+CD25+regulatory T cells in human thymus. Nature. 2005;436:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/nature03886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fairchild PJ, Austyn JM. Thymic dendritic cells: Phenotype and function. Int Rev Immunol. 1990;6:187–196. doi: 10.3109/08830189009056629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fergusson JR, et al. Maturing Human CD127+ CCR7+ PDL1+ Dendritic Cells Express AIRE in the Absence of Tissue Restricted Antigens. Front Immunol. 2019;9:2902. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu Z, Lancaster JN, Ehrlich LIR. The Contribution of Chemokines and Migration to the Induction of Central Tolerance in the Thymus. Front Immunol. 2015;6:398. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lei Y, et al. Aire-dependent production of XCL1 mediates medullary accumulation of thymic dendritic cells and contributes to regulatory T cell development. J Exp Med. 2011;208:383–394. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Skok JA, et al. Reversible contraction by looping of the Tcra and Tcrb loci in rearranging thymocytes. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:378–387. doi: 10.1038/ni1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mallis RJ, et al. Pre-TCR ligand binding impacts thymocyte development before αßTCR expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:8373–8378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504971112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carico ZM, Roy Choudhury K, Zhang B, Zhuang Y, Krangel MS. Tcrd Rearrangement Redirects a Processive Tcra Recombination Program to Expand the Tcra Repertoire. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2157–2173. doi: 10.1016/Jcelrep.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequencing data have been deposited to ArrayExpress (accession number E-MTAB-8581) and can be accessed online through a web portal (https://developmentcellatlas.ncl.ac.uk). All codes used for data analysis are available from Zenodo repository (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3572422).