Abstract

Introduction

Exhaled breath analysis has the potential to provide valuable insight on the status of various metabolic pathways taking place in the lungs locally and other vital organs, via systemic circulation. For years, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have been proposed as feasible alternative diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for different respiratory pathologies.

Methods

We reviewed the currently published literature on the discovery of exhaled breath volatile organic compounds and their utilisation in various respiratory diseases

Results

Key barriers in the development of clinical breath tests include the lack of unified consensus for breath collection and analysis and the complexity of understanding the relationship between the exhaled VOCs and the underlying metabolic pathways.

We present a comprehensive overview, in light of published literature and our experience from co-ordinating a national breathomics centre, of the progress made to date and some of the key challenges in the field and ways to overcome them. We particularly focus on the relevance of breathomics to clinicians and the valuable insights it adds to diagnostics and disease monitoring.

Conclusions

Breathomics holds great promise and our findings merit further large-scale multicentre diagnostic studies using standardised protocols to help position this novel technology at the centre of respiratory disease diagnostics.

Keywords: Exhaled Airway Markers, Respiratory Infection

Introduction

Respiratory diseases remain among the leading causes of death worldwide1. By 2030, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that respiratory illnesses will account for about one in five deaths worldwide2.

Early, rapid detection and treatment of lung diseases remain a priority, which would improve patient care and personalised therapy3. For years, existing technologies like lung function tools and blood biomarkers have played an important role in diagnosing and monitoring lung diseases. However, there remains an unmet need for point-of-care respiratory specific biomarkers that can aid in advancing precision medicine in both acute and stable respiratory diseases.

The lungs are almost unique owing to their ability to provide biological samples, direct from the organ with every breath. The ability to capture and analyse this sample type is highly attractive, as it allows direct non-invasive measurement of on-going metabolic processes.

Breathomics, a branch of metabolomics studying exhaled breath, is a steadily evolving field that focuses on understanding the nature of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and their health-related uses. VOCs can be leveraged as diagnostic biomarkers owing to their potential to mirror pathological processes taking place locally in the lungs and systematically, via the blood circulation4. Additionally, they offer a non-invasive platform that is repeatable and potentially personalised, via ‘breathprint’ signatures5. Despite years of clinical trials, technical and statistical challenges have delayed further translation of this technology to a real-world clinical setting.

In this state-of-the-art review we examine the current evidence, analytical challenges and future considerations of exhaled breath analysis in respiratory diseases.

Data sources and search criteria

For the purpose of this narrative review, a systematic search was conducted using the following evidence databases: (i) PubMed, (ii) Medline and (iii) EMBASE. The keywords and mesh terms used to complete the search included: ‘asthma’, ‘volatile organic compound(s)’, ‘exhaled breath’, ‘VOC’, ‘VOCs’, ‘origin of VOCs’, ‘electronic nose’, ‘eNose’, ‘chronic obstructive pulmonary disease’, ‘respiratory infections’, ‘lung cancer’, ‘airflow limitation’, ‘Emphysema’ and ‘chronic bronchitis’.

Published peer-reviewed, full-text articles concerning clinical studies using volatile organic compounds in a diagnostic or disease monitoring capacity were assessed for eligibility. The following study types were included: observational studies, cross-sectional, case–control and cohort, and randomised controlled trials. The references lists of included studies were scrutinised to identify further relevant studies.

The studies were assessed based on their methodology and published results. Key findings from these studies are presented in the relevant sections.

Historical Perspective of Breath analysis

Utilisation of exhaled breath VOCs for disease diagnostics dates back to ancient Greek civilisations where breath was used to diagnose various illnesses. For example, the fruity smell of diabetic ketoacidosis and the fishy smell of liver illnesses6–8. These elementary smell detection tests can be considered as the foundation of breath analysis.

The 20th century witnessed remarkable achievements in the field of breath testing, notably in 1971 Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling presented a gas chromatogram showing separation of volatile substances from human breath, subsequently describing 250 components in exhaled breath9. It was not, however, until the mid-eighties when Gordon et al. demonstrated the feasibility of analysing exhaled breath VOCs in early diagnosis of lung cancer10. This early association of VOCs and human disease formed the foundation for the current use of breathomics in early diagnosis and stratification of lung diseases.

In the following years, exhaled breath analysis gained increasing attention as a tool for diagnosing various illnesses. The specific pathways for these VOCs are not fully understood, nonetheless, profound progress has taken place with analytical technologies and detection capabilities.

Volatile organic compounds

Each exhaled breath contains thousands of VOCs; a heterogeneous group of carbon-based chemicals characterised by a high vapour pressure resulting from a low boiling point at room temperature.

Each breath cycle consists of different breath phases, and breath samples are often captured from the phase involved in gaseous exchange. This is also known as the ‘end expiratory phase’ or ‘alveolar breath’, excluding the dead space 11,12.This can be achieved using ‘gated sampling’, a process by which fractions of breath are collected based on measured parameters.

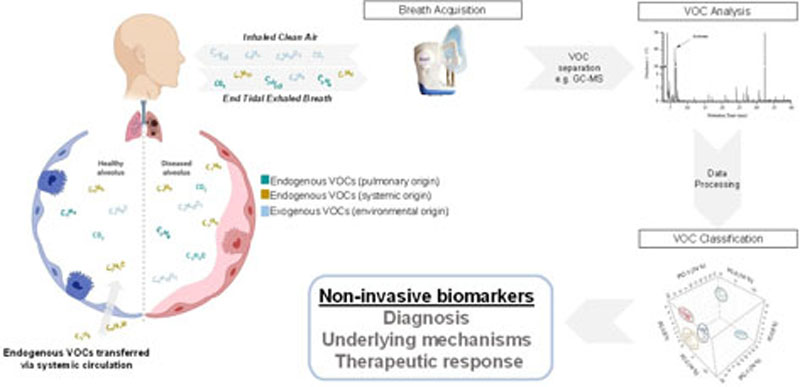

VOCs can originate from the external environment (exogenous) or from internal metabolic processes (endogenous) (Figure 1). The presence of abundant exogenous compounds in breath samples (i.e. environmental contamination) represents a fundamental challenge in breath research. Exogenous VOCs are continuously introduced into the respiratory system and owing to the complex kinetics of gas exchange, these can result in the production of volatile by-products, via various interactions with airway microbiota and mucosal lining13.

Figure 1.

This figure highlights the complex kinetic of gaseous exchange. Endogenous VOCs can originate from the lungs or distant organs, via systemic circulation. Exogenous VOCs are continuously introduced into the respiratory system which can result in the production of volatile downstream products. Breath samples containing endogenous and exogenous VOCs are analysed to generate clinically meaningful data.

Removal of exogenous VOCs may simplify analysis, but loses potentially useful signals and requires additional processing steps. For example Limonene, a widely used food additive and fragrance for cosmetic or cleaning products14, is present in higher levels in patients with liver cirrhosis and those with hepatic encephalopathy symptoms15.

In essence, exogenous VOCs and environmental contamination should be given special consideration when analysing exhaled breath VOCs for discovery studies; it continues to be an area of great uncertainty and larger multi-centre studies validating environmental exposomes should be carried out.

Breath collection and storage

VOCs are found in trace levels (mainly in parts per trillion to parts per billion range) which poses considerable analytical challenge to operators16. Current technologies allow for hundreds of VOCs to be detected in each exhaled breath sample.

Breath collection is a key step in this process and sub-optimal sampling can introduce contaminants, lose potential markers or alter the balance of breath patterns. As a result, considerable effort has been put into improving and standardising sampling and pre-concentration steps.

Breath sampling can either be direct, usually with point-of-care analysis, known as “online” sampling; or indirect, with breath stored for lab-based analysis, known as “offline” sampling. In both, careful attention needs to be paid to the choice of sampling process and analytic platform.

Collection bags made of Tedlar®, PTFE or foil have been widely used as receptacles for breath sample storage. Bags are attractive as they are a convenient, inexpensive and are disposable for potentially infectious samples17, however, potential drawbacks are 1) compound degradation within collection bags, particularly when samples remain mixed with water vapour and 2) compound interactions within the bag product. Additionally, Steeghs et al 18 tested the compatibility of Tedlar® bags and highlighted two abundant compounds contaminating bag contents. A reproducible compound loss was also detected both during bag filling and at a later stage following storage. Important considerations and suggestions for bag handling have been published17.

Various direct breath collection devices have emerged over the last few years 19–21. One example is the ReCIVA® (Respiration Collector for In Vitro Analysis) breath sampler (Owlstone Medical, Cambridge, UK), which is a handheld, portable device, designed to collect breath directly onto sorbent tubes that are then transferred for analysis 22. The portability of such devices allow for breath collection at the patient’s bedside.

Sorbent tubes are commonly used for trapping and transporting VOCs from breath samplers to analytical devices, offering significant cost and logistical advantages 23. Sampling onto sorbent tubes is usually carried out using a calibrated pump where air is drawn through the tube at a constant rate and as the breath sample passes through the tube, compounds are collected on the absorbent inside.

A common concern with this method is that sorbents can retain moisture, given the high water vapour content in breath, which can negatively affect the quantitative capture of some analytes. In an attempt to overcome this problem, samples can be dry purged where a pure inert gas is passed through the sorbent tube to eliminate any additional trapped moisture whilst retaining analytes24.

VOCs are released from the tube for analysis using a process known as thermal desorption. Samples are heated to allow for sample extraction from the absorbent interior onto a pre-cooled trap, before further desorption into the analytical system. This offers numerous benefits including concentration enhancements, amplifying detection limits and eliminating unwanted analytical interferences25.

Other considerations when undergoing breath collection include the time of day. Wilkinson et al 26 demonstrated a circadian variability in a proportion of exhaled VOCs over a 24 hours period with differential patterns of VOC release in asthmatics compared to healthy breath.

Breath analysis

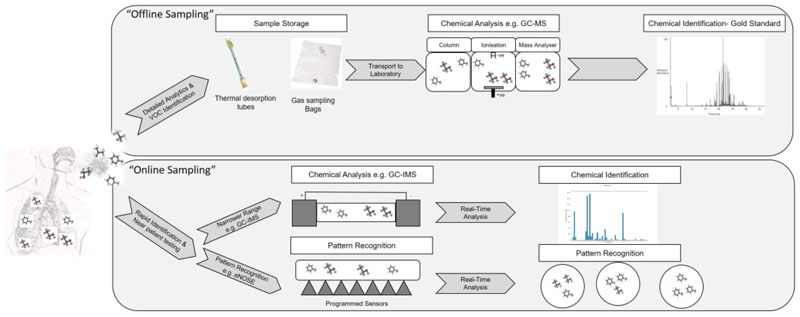

There are a number of technologies that can be used to analyse breath samples. Broadly these can be divided based on offline and online sampling techniques (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Exhaled breath VOCs can be analysed using offline or online technologies. Offline technologies, currently considered gold standard, involve storing samples in a sorbent tube or collection bag prior to injecting them to an analytical instrument (e.g. GC-MS). Online technologies involve direct introduction of breath samples to analytical instruments for analysis, negating the need for sample collection and storage. Online technologies require less analytical instrument time and technical skills and results can be obtained immediately, however, they lack the ability to identify compounds with high fidelity which limited its applications

Offline technologies

Offline technologies are considered the gold standard techniques for breath analysis and include:

Gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is the commonest chromatographic technique, allowing for compound separation and identification based on both retention time and mass spectra matching27. Gas chromatography comprises two main phases 1) the mobile phase: the vaporised sample is carried in an inert gas (e.g. helium) at a predetermined speed which is then passed through a chromatographic column 2) the stationary phase: compounds are separated based on the strength of interaction between the molecules and the column; with the time taken for it to pass through the column known as retention time. Despite being highly sensitive and reproducible, complex pre-sample processing, prolonged analysis time and expert knowledge requirement has hampered its use in a wider clinical setting. A number of studies have emerged over the years using GC-MS to examine specific VOCs for lung pathologies28–30, however, the lack of standardisation and methodological platforms limited further exploration of this technology in wider multi-centre comparison studies.

Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC×GC-MS) Is a multidimensional gas chromatography technique where the addition of an extra column provides superior separation over conventional GC-MS31. As the analytes elute from the primary column, they are modulated onto a secondary column. This shorter secondary column leads to further separation allowing peaks with similar volatility, which could not be separated adequately with one-dimensional chromatography, to be separated by another mechanism. This is particularly helpful in complex matrices like breath samples31–33. As the technique is more advanced, it has a higher initial capital cost compared to traditional GC-MS and requires more specialist skills to operate.

Online technologies

Online technologies involve direct introduction of breath samples into analytical instruments for analysis, negating the need for sample storage. As online technologies often require less analytical time results can be obtained immediately and, owing to their portability, they offer a potential for point of care testing. However, this means any chromatographic separation and analytical detector are often simplified, reducing the ability to identify compounds with high fidelity. This, and the lack of data processing parameters, limits its applications to proof-of-concept benchmarking studies and validation studies34.

Common examples of these technologies include:

Gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS): First described by McDaniel in the 1950s, IMS is an analytical technique that separates and identifies ionised molecules in the gas phase based on their mobility in a carrier buffer gas35, it can detect VOCs down to ultra-trace levels (ng/l to pg/l range) without the need for pre-concentration, visualising VOCs in a 3D IMS chromatogram. Without identifying individual chemical components, IMS recognises peak patterns that can be used for disease recognition. Its simplicity and easy patient interface allowed its utilisation in few studies in the last decade 36–39.

Proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry (PTRMS) PTR-MS has the capability of real-time analysis: it’s considered one of the fastest analytical techniques with a typical time resolution of <100ms. VOCs are ionised by transferring a proton from the reagent ion, hydronium (H3O+), to any molecules with a suitable proton affinity, which are then separated in the mass spectrometer. Despite its speed the lack of pre-concentration can limit sensitivity and the absence of chromatographic separation limits its ability to definitively identify compounds compared to GC-MS.

Electronic nose technology (eNose)

Loosely mimicking human olfaction, electronic noses are made of multiple array sensors programmed to recognise different odours and comparing them to pre-programed patterns40. Array sensors convert chemical input (breath samples) into electrical signals41. Electronic noses do not contribute to individual compound identification, instead disease separation occurs through recognition of different breath profiles, also known as ‘breath prints’ or ‘breath signatures’ using pattern recognition algorithms.

Unlike GC-MS, analysis eNoses don’t require highly skilled operators, and has a relatively quick operational time (results within minutes), with lower technical costs. Its readily implementable nature makes it more suited for point of care clinical testing compared to other offline technologies7. However, there are some disadvantages compared to mass spectroscopy, mainly the inability to identify named compounds in complex mixtures, making it impossible to link back to metabolic processes and mechanistic pathways 42. Additionally, the breath signatures are highly influenced by environmental factors and water vapour, so considered to be less rigorous7.

Several diagnostic studies have been carried out using eNoses in airway disease43–46 and lung cancer47–49 with good discriminatory power. Furthermore, Plaza et al 50 described the ability of breath signatures in stratifying different phenotypes of asthma based on their sputum granulocytic count.

As described, eNose technology has the potential to make a powerful screening tool for various pulmonary diseases. Further largescale pragmatic clinical trials are required to further validate this. The limited sensor stability, inability to calibrate and the difficulty in mass generating identical sensors have hindered further translation of this technology to a real-world clinical setting.

Headspace analysis

Headspace refers to the volume of gas directly above and in contact with a biological sample. Headspace has been utilised as a VOC source for a number of solid and liquid samples. For headspace analysis purposes, samples are usually kept within sealed glass vials that are either heated or air is driven over them to stimulate VOC release out of samples. Once stabilised, the gas within the vial is then collected or directly transferred to instruments for analysis.

Although still in the early stages of development, headspace analysis has been used to investigate compounds from bacteria implicated in ventilator-associated pneumonia 51 and the identification of more specific organisms such as Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Aspergillus fumigatus 52–54, with promising results.

In-vitro breath analysis adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of headspace VOC analysis in clinical practice, however, it faces many challenges including sample degradation requiring standardised protocols for sample storage and treatment.

VOCs in Respiratory Disease

Exhaled breath of healthy individuals contains a wide range of volatile organic compounds at varying concentrations. These compounds include, but are not limited to, hydrocarbons, ketones, aldehydes and alcohols55. A breakdown of the various functional groups and their structure formulas are highlighted in (Supplementary table 1). The content and concentrations of these VOCs vary depending on the underlying metabolomic pathways during health and disease states as well as environmental interferences.

It wasn’t until advanced analytical techniques were introduced in the 1990s that a complete set of human breath profile had emerged for the first time56. Hydrocarbons were one of the first discovered compounds in human breath, dating back to 1963 Chandra and Spencer reported unexpected ethylene levels in exhaled human breath that were not thought to be solely attributable to gut flora57. This was later believed to be associated to disease state when small chain hydrocarbons, which were thought to be a direct result of lipid peroxidation, were identified in exhaled breath58.

Exhaled breath VOCs analysis has been utilised in a variety of respiratory conditions, including:

Airway diseases

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are two of the most common respiratory diseases affecting millions of people59. The utilisation of VOCs in airways disease is promising, although to date there are no definitive diagnostic breath signatures for either disease to aid disease classification. Numerous studies have evaluated the use of exhaled VOCs in diagnosing and phenotyping airways diseases, with the most commonly identified compounds belonging to carbonyl-containing groups (i.e. aldehydes, esters, and ketones) and hydrocarbons (i.e. alkanes, alkenes and monoaromatics)60–62.

In one of the largest exhaled breath studies in asthma, Schleich et al 63 were able to successfully classify 521 asthmatic patients into three groups based on their sputum granulocytic cell count, potentially offering surrogate biomarkers for eosinophilic and neutrophilic asthma.

Exhaled breath VOCs have been shown to successfully separate asthma and COPD 64,65, breath signatures using eNoses have been shown to do the same based on clinical and inflammatory characteristics rather than disease diagnosis 66.

Basanta et al 67 investigated the relationship between exhaled breath VOCs and existing indices of inflammation and described in great detail the ability of GC-ToF-MS in discriminating COPD patients based on inflammatory cells into eosinophilic and neutrophilic subgroups, this particularly relevant in precision medicine and assessment of treatment response.

Exhaled breath analysis shows a promise in enhancing our knowledge of the pathogenic pathways driving airway diseases. The use of VOCs as stratification biomarkers in this diverse patient population has the potential to transform the care we offer. Further progression towards a real world clinical translation will highly depend on the implementation of large-scale, well powered, multi-centre clinical studies.

VOCs in respiratory infections

The treatment of microbial respiratory infections is an obvious target for breathomics, as early and accurate identification of causative organisms can be challenging, particularly in patients with severe infections68. Micro-organisms produce a wide variety of volatile metabolites, which can be released in the stable state or when the cell is disrupted in cases of infection69–71; these volatiles can serve as a biological marker of microbial presence and have the potential to enhance the diagnostic process, improving clinical outcomes72.

The presence of distinct VOC profiles in pneumonia has been demonstrated by multiple studies73–75, however, none have established sufficient granularity to accurately diagnose pneumonia based on a single breath test. A systematic review by Van Oort et al 76 outlined nitric oxide (NO), among others, as a potential diagnostic biomarker; though this is thought to be less specific as various other respiratory conditions drive altered NO bioactivity during disease state 77.

Boots et al78 examined two hundred samples of bacterial headspace (defined as the area of gas directly surrounding a sample) from four different microorganisms (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae) and demonstrated a highly significant difference in VOC occurrence of different bacterial cultures, Additionally, they demonstrated separation between methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive isolates of staphylococcus aureus potentially translating to a valuable diagnostic tool in medical microbiology.

There is an urgent unmet need for a rapid and accurate test to diagnose tuberculosis, owing to the high diagnostic delay 79,80. Breath analysis has the potential to diagnose TB with moderate accuracy 81 through the detection of specific VOCs produced by Mycobacteria 82,83, however, implementing VOCs as standard diagnostic tools will require further developments.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a growing area of interest in respiratory medicine, several studies have examined the role of exhaled breath VOCs in CF patients; Kramer et al 84 demonstrated a proof-of-concept approach to using exhaled VOCs for the rapid identification of infectious agents in CF patients with lower respiratory tract infections. 2-aminoacetophenone (2-AA) was assessed for its specificity to Pseusdomonas aeruginosa in 29 CF patients and its suitability as a potential breath biomarker using GC-MS 85. The 2-AA was detected in a significantly higher proportion of subjects colonised with Ps. aeruginosa (93.7%) than both the healthy controls (29%) and CF patients not colonised with Ps. aeruginosa (30.7%) indicating that (2-AA) is potentially a promising breath biomarker for colonisation.

Breath analysis has the potential to be positioned in both the diagnostic and therapeutic work-flows of respiratory infections, guiding early diagnosis and judicious antimicrobial use.

VOCs in lung cancer

Lung cancer has a poor prognosis, mostly due to the lack of symptoms and late presentation. While screening with CT has been introduced, the ability to diagnose through breath would likely lead to significant clinical impact, with considerably less radiation exposure to patients86.

Metabolic changes within cancer cells can lead to significant changes in volatile breath profile87. Over the years, this has been explored as a potential avenue for early detection and diagnosis of lung cancer 88–91.

One of the first studies to utilise VOCs in lung cancer was carried out by Gordon et al 10 in 1985, they reported a GC-MS profile of exhaled breath profile of 12 samples from lung cancer patients and 17 control samples with almost complete differentiation between the two groups.

Bajtarevic et al 89 expanded on this to include an additional analytical instrument, utilising both proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry (PTR-MS) and solid phase microextraction with subsequent gas chromatography mass spectrometry (SPME-GCMS), with a larger sample size (220 lung cancer patients at different stages of illness and 441 healthy volunteers), they reported that the three main compounds appearing in everybody’s exhaled breath (isoprene, acetone and methanol) were found at a slightly lower concentration in lung cancer patients compared to healthy volunteers using PTRMS, additionally, the sensitivity of detection of lung cancer volatiles in breath based on the presence of four different compounds was only 52%, going up to 71% when including 15 compounds. The compounds identified were mainly alcohols, aldehydes, ketones and hydrocarbons.

Dragonieri et al 48 adopted a different approach by using electronic nose and was able to discriminate breath profiles of 30 subjects with non-small cell lung cancer from COPD patients and healthy volunteers, with modest accuracy.

The aforementioned studies have formed the foundation for large scale clinical trials evaluating the use of exhaled breath VOCs in patients with a clinical suspicion of lung cancer 92. Further results of large scale trials are eagerly anticipated.

VOCs in other respiratory conditions

Exhaled breath VOCs have been utilised in various other respiratory illnesses, nearly 90% of 25 patients with Pneumoconiosis were discriminated by their breath profile (ROC-AUC 0.88) 93.

Several studies examined the role of exhaled VOCs in interstitial lung disease, Yamada et al 39 described five characteristic VOCs in the exhaled breath of IPF patients, using multi-capillary column-ion mobility spectrometry (MCC-IMS). Of the five VOCs, four were identified as p-cymene, acetoin, isoprene and ethylbenzene. Further work in ILD was carried out using ion mobility spectrometry (IMS), which seems to be a promising technique in discriminating ILD patients from healthy controls94.

eNose sensors were used in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), breath prints changed dramatically after a single-night CPAP and changes conformed to two well-distinguished patterns indicating that exhaled breath prints can potentially qualify as a surrogate index of response to and compliance with CPAP95.

The most clinically relevant volatile compounds are listed in (Supplementary table 2) along with the corresponding analytical technologies and reported concentration changes.

Clinical Implementation

The non-invasive nature, low patient burden, and ability to directly sample from the target organ, makes the adoption of breathomics in real-world clinical practice an attractive prospect. However, clinical implementation has proved more challenging. The majority of reported breath studies so far have been small in size, single-centred, and with no external validation. Nonetheless, several papers have assessed the feasibility of breath sampling in various clinical settings, including outpatient clinics 61,96, acute admission units 97,98, and intensive care units 74,99, with promising results.

External validation of breath biomarkers in independent populations is considered instrumental as it produces reliable predictions that can be reproduced in other clinical settings. The lack of external validation has created significant reporting challenges. From our review, there is little overlap between biomarkers reported by various groups which can be partially explained by the differences in methodology and reporting tools. The first step towards establishing a breathomics platform in clinical settings would be to regulate practices, including agreed common standardised operating procedures (SOPs) for breath collection, storage, and analysis.

Clinical implementation of breathomics is thought to be particularly relevant amidst the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported to cause a multitude of symptoms that affect several organs and systematic metabolism resulting in altered volatile metabolite distribution. Additionally, the rapid detection of COVID-19 specific VOC panel is thought to be particularly rewarding if tuned to assess the negative predictive value; this can be used to screen large populations (e.g. airports, schools) as a first line test in ruling-out rather than ruling-in test, and to determine which individuals need further testing. This will enable rapid decision making as well as provide complementary information that will strengthen disease diagnostics.

Challenges and future considerations

Current analytical technologies have demonstrated an innovative ability to separate and detect a wide range of exhaled breath VOCs, however, the implementation of these techniques in a real world clinical setting faces considerable chemical and analytical barriers. One of the major unresolved challenges is that of environmental contamination and their interference with exhaled breath VOCs, there is still no unified consensus on how to tackle this issue; as relevant as it is to subtract environmental VOCs100, it is crucial to take all molecular breath interactions into consideration when generating a diagnostic breath matrix. Standardised protocols should be instated for breath collection, analysis and reporting to guide future studies and allow a transparent analytical comparability across sites.

The availability of multiple analytical platforms with contrasting performance measures adds to the complexity of standardising biomarker discovery protocols. The choice of technology comes down to device availability and study budget, however, discovery studies are carried out using devices with the ability to separate and detect compounds with higher sensitivity and established robustness like (GC-MS). Although considered gold standard, GC-MS devices are considered highly complex for the non-experienced and are time consuming, making them less desirable in a real-world clinical setting. Sensor-array based technologies are much easier to use but are usually spared for when studies are aiming to distinguish between breath profile without the need for named compounds.

Analysis of breath matrices is highly complex, the combination of large variables and a relatively small sample size has led to various analytical challenges, the commonest being that of ‘overfitting’. With overfitting, usually owing to a limited sample size, the whole dataset is used to train and validate discovery prediction models, as opposed to having separate discovery and replication datasets, this results in a falsely optimistic models that can’t be generalised to the entire population. Ideally, this is overcome by training prediction models in a distinct dataset that is separate to and independent from the validation dataset, currently considered the gold standard method101,102.

Exhaled breath biomarkers are envisaged to have a crucial role as point-of-care tests in emergency departments and primary care clinics, however, to our knowledge no major studies have been completed in these settings. To date, biomarker discovery studies have mostly been small in size and confined to single centres. With few exceptions103–105, the majority of the published breath discovery studies have been carried out in the stable disease state or at an outpatient clinic level. Further large-scale trials targeting acute disease states are required to properly evaluate the reliability of these breath tests and to formally assess the replicability in a real-world clinical setting.

Exhaled VOCs can provide valuable insight into the metabolic processes in the human body beyond the lungs, this can further expand our understanding of the common respiratory metabolic traits, translating into improved patient-centred diagnostics and therapeutic measures. Only when the aforementioned challenges are addressed, can the value of breath technology be fully appreciated.

Conclusion

Exhaled breath analysis possesses an inherit appeal that has been explored by scientists and clinicians for many decades. The lack of consistency in trial outcomes among other challenges have hindered faster translation of this technology into a real-world clinical setting. Considerable effort has been invested over the last few years to address these issues but exhaled breath analysis is still far from clinical implementation. In this state-of-the-art review we presented a comprehensive critique of the published literature and highlighted some of the key challenges and ways to overcome them.

Looking at the current state of the field compared to where it was 10 years ago predicts an encouraging future for exhaled breath analysis that can potentially revolutionise health care and point-of-care diagnostics.

Table 1. A breakdown of various functional groups and their structure formulas.

| Functional group | Structure formula | Class of compound | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino | -NH2 | Amines |

|

| Carbonyl | -CHO | Aldehydes |

|

| Carbonyl | -CO | Ketone |

|

| Carboxyl | R-COOH | Carboxylic acid |

|

| Hydroxyl | R-OH | Alcohols |

|

| Phenyl |

|

Cyclic/aromatic |

|

Table 2. Summary of VOC biomarkers in various respiratory conditions from key breath studies and their reported concentration changes.

| Compound and chemical classification | Author | Disease | Participants | (N=) | Concentration | change | Analytical technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldehydes | |||||||

| 2-oxoglutaric acid semi-aldehyde | Bregy et al 60 | COPD | 36 | ↑ | SESI-MS | ||

| aspartic acid semi-aldehyde | Bregy et al 60 | COPD | 36 | ↑ | SESI-MS | ||

| Nonanal | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | ↑ | GC-TOF-MS | ||

| Nonanal | Callol-Sanchez et al 90 | Lung cancer | f 210 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Nonanal | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Nonanal | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Nonanal | Fowler et al 73 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 46 | ↑ | TD/GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Pentadecanal | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | ↑ | GC-TOF-MS | ||

| Pentadecanal | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| Tetradecanal | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Undecanal | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | ↑ | GC-TOF-MS | ||

| Acrolein | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↓ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Esters | |||||||

| Ethyl 2,2-dimethylacetoacetate | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Linalylacetate | Gaida et al 62 | COPD | 190 | ↑ | TD-GC-MS | ||

| Ketones | |||||||

| 2-butanone | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 2-hexanone | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| 2-pentanone | Allers et al 108 | COPD | 58 | ↑ | GC-APCI-MS | ||

| 2-pentanone | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↑ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| 4-heptanone | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↑ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↓ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| Acetone | Martinez et al 109 | COPD | 61 | ↑ | GC-IMS | ||

| Cyclohexanone | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↑ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| Cyclohexanone (CAS 108-94-1) | Westhoff et al 110 | COPD | ↑ | GC-IMS | |||

| 2-methyl cyclopentanone | Fowler et al 73 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 46 | î | TD-GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Organic acids | |||||||

| 11-hydroxyundecanoic acid | Bregy et al 60 | COPD | 36 | ↓ | SESI-MS | ||

| Acetic acid | Phillips et al 20 | COPD | 182 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Butanoic acid | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | ↓ | GC-TOF-MS | ||

| Dodecanedioic acid | Bregy et al 60 | COPD | 36 | ↓ | SESI-MS | ||

| Oxoheptadecanoic acid | Bregy et al 60 | COPD | 36 | ↓ | SESI-MS | ||

| Pentanoic acid | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | ↓ | GC-TOF-MS | ||

| Alkanes | |||||||

| 3,7-dimethylnonane | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| Hexane | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| Undecane | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 2,6-Dimethyl-heptane | Van Berkel et al 111 | COPD | 79 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| 4,7-Dimethyl-undecane | Van Berkel et al 111 | COPD | 79 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| 4-Methyl-octane | Van Berkel et al 111 | COPD | 79 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Hexadecane | Van Berkel et al 111 | COPD | 79 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| 6-ethyl-2-methyl-Decane | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↑ | SPME-GC-MS | ||

| Decane | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↑ | SPME-GC-MS | ||

| Hexane, 3-ethyl-4-methyl- | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↓ | SPME-GC-MS | ||

| 2 methyl-decane | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 2,6,10-trimethyl-dodecane | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 2,6,11-trimethyl-dodecane | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 5,5-Dibutylnonane | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| Dodecane | Schnabel 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↓ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Tetradecane | Schnabel 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Pentane | Olopade et al 56 | Asthma | 40 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Ethane | Paredi et al 113 | Asthma | 40 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Butane | Phillips et al 20 | COPD | 182 | — | GC-MS | ||

| Butane | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| 2,4-dimethylheptane | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↓ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| 2,6-dimethyloctane | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↓ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| 2-methylhexane | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↑ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| cyclohexane | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↑ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| n-butane | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↓ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| n-Heptane | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↑ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| Heptane | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Heptane | Fowler et al 73 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 46 | ↓ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Alkenes | |||||||

| 3-tetradecene | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Pentadecene | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Isoprene | Van Berkel et al 111 | COPD | 79 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Isoprene | Phillips et al 20 | COPD | 182 | — | GC-MS | ||

| 1-Pentene, 2,4,4-trimethyl- | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↓ | SPME – GC-MS | ||

| 1,6-Dimethyl-1,3,5-heptatriene | Gaida et al 62 | COPD | 190 | — | GC-MS | ||

| 3,5-heptatriene | Gaida et al 62 | COPD | 190 | — | GC-MS | ||

| 4-ethyl-o-xylene | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| Nonadecane | Phillips et al 20 | COPD | 182 | — | GC-MS | ||

| Monoaromatics | |||||||

| Benzene, 1,3,5-tri-tert-butyl- | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↓ | SPME – GC-MS | ||

| 1-Ethyl-3-methyl benzene | Gaida et al 62 | COPD | 190 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Benzene | Phillips et al 20 | COPD | 182 | — | GC-MS | ||

| Ethylbenzene | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated • pneumonia | 100 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Terpenes | |||||||

| Limonene | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↓ | SPME – GC-MS | ||

| Terpinolene | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Alcohols | |||||||

| Cyclohexanol | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | ↑ | GC-TOF-MS | ||

| Bicyclo[2.2.2]octan-1-ol, 4-methyl -C9H16O | Brinkman et al 104 | Asthma | 23 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Methanol CH3OH | Brinkman et al 104 | Asthma | 23 | ↑ | ■GC-MS | ||

| 2-Propanol | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↓ | SPME – GC-MS | ||

| Phenole | Gaida et al 62 | COPD | 190 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 2-butylcyclohexanol | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| Ethanol | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Isopropyl Alcohol | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↓ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Benzyl alcohol | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 1-propanol | Schleich et al 63 | Asthma | 521 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| 1-propanol | Van Oort et al 74 | Pneumonia | 93 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Phenol derivatives | |||||||

| Butylated hydroxytoluene | Cazzola et al 112 | COPD | 34 | ↓ | SPME – GC-MS | ||

| m/p-Cresol, | Gaida et al 62 | COPD | 190 | — | GC-MS | ||

| Sulphides | |||||||

| Phthalic anhydride | Phillips et al 20 | COPD | 182 | — | GC-MS | ||

| Sulphur dioxide | Phillips et al 20 | COPD | 182 | — | GC-MS | ||

| dimethyl disulfide | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | — | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| methyl propyl sulfide | Pizzini et al 61 | COPD | 54 | ↑ | TD-GC-ToF-MS | ||

| Permanent gases | |||||||

| Ethyl 4-nitrobenzoate | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| Indole | Martinez et al 109 | COPD | 61 | ↑ | GC-IMS | ||

| Indole | Gaida et al 62 | COPD | 190 | — | GC-MS | ||

| Heterocycles | |||||||

| Oxirane-dodecyl | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | — | GC-TOF-MS | ||

| y-hydroxy-L-homoarginine | Bregy et al 60 | COPD | 36 | ↑ | SESI-MS | ||

| Nitriles | |||||||

| Ace-tonitrile - C2H3N | Brinkman et al 104 | Asthma | 23 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Hexyl ethylphosphonofluoridate | Cazzola et al 114 | COPD | 34 | ↓ | SPME – GC-MS | ||

| Furans | |||||||

| 2-pentylfuran | Basanta et al 67 | COPD | 71 | ↑ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Tetrahydro-Furan | Schnabel et al 107 | Ventilator associated pneumonia | 100 | ↓ | GC-Tof-MS | ||

| Others | |||||||

| 2,6-Di-tert-butylquinone | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↓ | GC-MS | ||

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzonitrile | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| Allyl methyl sulphide | Ibrahim et al 106 | Asthma | 58 | ↑ | GC-MS | ||

| 2'-Aminoacetophenone | Scott Thomas et al 85 | Cystic Fibrosis | 46 | ↑ | SPME – (GCMS) | ||

| Hexafluoroisopropanol | Van Oort et al 74 | Pneumonia | 93 | ↓ | GC-MS – compound considered by authors to be likely exogenous in origin |

Acknowledgments

We thank the entire EMBER team for supporting this project. The following respondents opted to have their name acknowledged:

Ananga Sundari, Beverley Hargadon, Sheila Jones, Bharti Patel, Asia Awal, Rachael Phillips, Teresa McNally, Clare Foxon, (University Hospitals of Leicester). Dr. Matthew Richardson, Prof. Toru Suzuki, Prof. Leong L Ng, Dr. Erol Gaillard, Dr. Caroline Beardsmore, Prof. Tim Coates, Dr. Robert C Free, Dr. Bo Zhao, Rosa Peltrini, Luke Bryant (University of Leicester). Dorota Ruszkiewicz (Loughborough University)

Funding

This review was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Stratified Medicine Grant for Molecular Pathology Nodes (Grant No. MR/N005880/1) and Midlands Asthma and Allergy Research Association (MAARA), supported by the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Leicester Clinical Research Facility. Dr Greening is funded by a NIHR Fellowship (pdf-2017-10-052). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Footnotes

Contributorship statement

W.I and N.G conceived the presented review. W.I took the lead in writing the manuscript with support from N.G. and L. Ca.

All authors, including R. Co, M. Wi, D. Sa, P. Mo, P. Th, C. Br and S. Si contributed to the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ferkol T, Schraufnagel D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(3):404–6. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-405PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation (2010) Global status report on noncommunicable diseases, retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHS ENGLAND 2019. The NHS Long Term Plan, retrieved from https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/chapter-3-further-progress-on-care-quality-and-outcomes/better-care-for-major-health-conditions/respiratory-disease/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes VM, Kennedy AD, Panagakos F, et al. Global metabolomic analysis of human saliva and plasma from healthy and diabetic subjects, with and without periodontal disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cikach FS, Jr, Dweik RA. Cardiovascular biomarkers in exhaled breath. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;55(1):34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Probert CS, Ahmed I, Khalid T, Johnson E, Smith S, Ratcliffe N. Volatile organic compounds as diagnostic biomarkers in gastrointestinal and liver diseases. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18(3):337–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fens N, van der Schee MP, Brinkman P, Sterk PJ. Exhaled breath analysis by electronic nose in airways disease. Established issues and key questions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(7):705–15. doi: 10.1111/cea.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel K. Noninvasive tools to assess liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(3):227–33. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283383c68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pauling L, Robinson AB, Teranishi R, Cary P. Quantitative analysis of urine vapor and breath by gas-liquid partition chromatography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68(10):2374–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.10.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon SSJP, Krotoszynski BK, Gibbons RD, O’Neill HJ. Volatile Organic Compounds in Exhaled Air from Patients with Lung Cancer. Clinical chemistry. 1985;31(8) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawal O, Ahmed WM, Nijsen TME, Goodacre R, Fowler SJ. Exhaled breath analysis: a review of 'breath-taking' methods for off-line analysis. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2017;13(10):110. doi: 10.1007/s11306-017-1241-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doran SLF, Romano A, Hanna GB. Optimisation of sampling parameters for standardised exhaled breath sampling. J Breath Res. 2017;12(1):016007. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa8a46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson JC, Hlastala MP. Breath tests and airway gas exchange. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20(2):112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Limonene C. [accessed on June 5];2020 https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Limonene.

- 15.O’Hara ME, Fernández del Río R, Holt A, et al. Limonene in exhaled breath is elevated in hepatic encephalopathy. Journal of Breath Research. 2016;10(4) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/4/046010. 046010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith D, Spanel P. The challenge of breath analysis for clinical diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring. Analyst. 2007;132(5):390–6. doi: 10.1039/b700542n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beauchamp J, Herbig J, Gutmann R, Hansel A. On the use of Tedlar(R) bags for breath-gas sampling and analysis. J Breath Res. 2008;2(4) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/2/4/046001. 046001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steeghs MM, Cristescu SM, Harren FJ. The suitability of Tedlar bags for breath sampling in medical diagnostic research. Physiol Meas. 2007;28(1):73–84. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/1/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwak J, Fan M, Harshman SW, et al. Evaluation of Bio-VOC Sampler for Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds in Exhaled Breath. Metabolites. 2014;4(4):879–88. doi: 10.3390/metabo4040879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips CO, Syed Y, Parthalain NM, Zwiggelaar R, Claypole TC, Lewis KE. Machine learning methods on exhaled volatile organic compounds for distinguishing COPD patients from healthy controls. J Breath Res. 2012;6(3) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/6/3/036003. 036003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scarlata S, Finamore P, Santangelo S, et al. Cluster analysis on breath print of newly diagnosed COPD patients: effects of therapy. Journal of breath research. 2018;12(3) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aac273. 036022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitchen S, Edge A, Smith R, et al. LATE-BREAKING ABSTRACT: Breathe free: Open source development of a breath sampler by a consortium of breath researchers. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46(suppl 59) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woolfenden E. Monitoring VOCs in Air Using Sorbent Tubes Followed by Thermal Desorption-Capillary GC Analysis: Summary of Data and Practical Guidelines. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 1997;47(1):20–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gawlowski J, Gierczak T, Pietruszyñska E, Gawrys M, Niedzielski J. Dry purge for the removal of water from the solid sorbents used to sample volatile organic compounds from the atmospheric air. Analyst. 2000;125:2112–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang S, Paul Thomas CL. How long may a breath sample be stored for at -80 degrees C? A study of the stability of volatile organic compounds trapped onto a mixed Tenax:Carbograph trap adsorbent bed from exhaled breath. J Breath Res. 2016;10(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/2/026011. 026011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkinson M, Maidstone R, Loudon A, et al. Circadian rhythm of exhaled biomarkers in health and asthma. The European respiratory journal. 2019;54(4) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01068-2019. 1901068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia ABC. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)-Based Metabolomics. Metabolic Profiling. 2011;708:191–204. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-985-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dallinga JW, Van Berkel JJBN, Moonen EJC, et al. Volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath as a diagnostic tool for asthma in children. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2010;40(1):68–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van De Kant K, Jobsis Q, Klaassen E, et al. Volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath differentiate between preschool children with and without recurrent wheeze. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010;65:138. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munoz-Lucas A, Wagner-Struwing C, Jareno-Esteban J, et al. Differences in volatile organic compounds (VOC) determined in exhaled breath in two populations of lung cancer (LC): With and without COPD. European Respiratory Journal. 2013;42 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips M, Cataneo RN, Chaturvedi A, et al. Detection of an extended human volatome with comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry. PLoS One. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075274. e75274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caldeira M, Perestrelo R, Barros AS, et al. Allergic asthma exhaled breath metabolome: a challenge for comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1254:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das MK, Bishwal SC, Das A, et al. Investigation of Gender-Specific Exhaled Breath Volatome in Humans by GCxGC-TOF-MS. Analytical Chemistry. 2014;86(2):1229–37. doi: 10.1021/ac403541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruderer T, Gaisl T, Gaugg MT, et al. On-Line Analysis of Exhaled Breath. Chemical Reviews. 2019;119(19):10803–28. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanu AB, Dwivedi P, Tam M, Matz L, Hill HH., Jr Ion mobility-mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43(1):1–22. doi: 10.1002/jms.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anhenn O, Rabis T, Sommerwerck U, et al. Detection of differences in volatile organic compounds (VOCs) by ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) of exhaled breath in patients with interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) compared to healthy controls (HC) European Respiratory Journal. 2011;38 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurth JI, Darwiche K, Baumbach JI, Freitag L. A new possibility of process monitoring in lung cancer: Volatile organic compounds detected with ion mobility spectrometry to follow the success of the therapeutic process. European Respiratory Journal. 2011;38 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Besa V, Teschler H, Kurth I, et al. Exhaled volatile organic compounds discriminate patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from healthy subjects. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2015;10:399–406. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S76212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada Y-I, Yamada G, Otsuka M, et al. Volatile Organic Compounds in Exhaled Breath of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis for Discrimination from Healthy Subjects. Lung. 2017;195(2):247–54. doi: 10.1007/s00408-017-9979-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner JW, Bartlett PN. A brief history of electronic noses. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 1994;18(1):210–1. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bedard A, Dumas O, Kauffmann F, Garcia-Aymerich J, Siroux V, Varraso R. Potential confounders in the asthma-diet association: how causal approach could help? Allergy. 2012;67(11):1461–2. doi: 10.1111/all.12025. author reply 2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson AD. Advances in electronic-nose technologies for the detection of volatile biomarker metabolites in the human breath. Metabolites. 2015;5(1):140–63. doi: 10.3390/metabo5010140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dragonieri S, Schot R, Mertens BJA, et al. An electronic nose in the discrimination of patients with asthma and controls. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;120(4):856–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fens N, van der Schee MP, Brinkman P, Sterk PJ. Exhaled breath analysis by electronic nose in airways disease. Established issues and key questions. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2013;43(7):705–15. doi: 10.1111/cea.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lazar Z, Fens N, van der Maten J, et al. Electronic nose breathprints are independent of acute changes in airway caliber in asthma. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2010;10(10):9127–38. doi: 10.3390/s101009127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montuschi P, Mores N, Valente S, et al. Comparison of E-nose, fraction of exhaled nitric oxide and pulmonary function testing reproducibility in patients with stable COPD. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amann A, Corradi M, Mutti A, Mazzone P. Lung cancer biomarkers in exhaled breath. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2011;11(2):207–17. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dragonieri S, Annema JT, Schot R, et al. An electronic nose in the discrimination of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and COPD. Lung Cancer. 2009;64(2):166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McWilliams A, Beigi P, Srinidhi A, Lam S, MacAulay CE. Sex and smoking status effects on the early detection of early lung cancer in high-risk smokers using an electronic nose. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2015;62(8):2044–54. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2015.2409092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plaza V, Crespo A, Giner J, et al. Inflammatory Asthma Phenotype Discrimination Using an Electronic Nose Breath Analyzer. Journal of investigational allergology & clinical immunology. 2015;25(6):431–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawal O, Muhamadali H, Ahmed WM, et al. Headspace volatile organic compounds from bacteria implicated in ventilator-associated pneumonia analysed by TD-GC/MS. Journal of breath research. 2018;12(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa8efc. 026002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zscheppank C, Wiegand HL, Lenzen C, Wingender J, Telgheder U. Investigation of volatile metabolites during growth of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by needle trap-GC-MS. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406(26):6617–28. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu J, Bean HD, Wargo MJ, Leclair LW, Hill JE. Detecting bacterial lung infections: in vivo evaluation of in vitro volatile fingerprints. Journal of breath research. 2013;7(1) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/7/1/016003. 016003- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neerincx AH, Geurts BP, Habets MF, et al. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Aspergillus fumigatus mono-and co-cultures based on volatile biomarker combinations. J Breath Res. 2016;10(1) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/1/016002. 016002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fenske JD, Paulson SE. Human breath emissions of VOCs. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 1999;49(5):594–8. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1999.10463831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olopade CO, Zakkar M, Swedler WI, Rubinstein I. Exhaled pentane levels in acute asthma. Chest. 1997;111(4):862–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.4.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chandra GR, Spencer M. A micro apparatus for absorption of ethylene and its use in determination of ethylene in exhaled gases from human subjects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;69:423–5. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(63)91283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riely CA, Cohen G, Lieberman M. Ethane evolution: a new index of lipid peroxidation. Science. 1974;183(4121):208–10. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4121.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Global Strategy for the Diagnosis MaPoC. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bregy L, Martinez-Lozano Sinues P, Garcia-Gomez D, et al. Real-time mass spectrometric identification of metabolites characteristic of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in exhaled breath. Clinical Mass Spectrometry. 2018;7:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.clinms.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pizzini A, Filipiak W, Wille J, et al. Analysis of volatile organic compounds in the breath of patients with stable or acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of breath research. 2018;12(3) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aaa4c5. 036002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaida A, Holz O, Nell C, et al. A dual center study to compare breath volatile organic compounds from smokers and non-smokers with and without COPD. Journal of breath research. 2016;10(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/2/026006. 026006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schleich FN, Zanella D, Stefanuto P-H, et al. Exhaled Volatile Organic Compounds are Able to Discriminate between Neutrophilic and Eosinophilic Asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2019 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201811-2210OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fens N, Zwinderman AH, van der Schee MP, et al. Exhaled breath profiling enables discrimination of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180(11):1076–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0939OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Timms C, Thomas PS, Yates DH. Detection of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in patients with obstructive lung disease using exhaled breath profiling. J Breath Res. 2012;6(1) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/6/1/016003. 016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Vries R, Dagelet YWF, Spoor P, et al. Clinical and inflammatory phenotyping by breathomics in chronic airway diseases irrespective of the diagnostic label. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01817-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Basanta M, Ibrahim B, Dockry R, et al. Exhaled volatile organic compounds for phenotyping chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study. Respiratory research. 2012;13:72. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Masterton RG, Galloway A, French G, et al. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: report of the working party on hospital-acquired pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(1):5–34. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dickschat JS, Martens T, Brinkhoff T, Simon M, Schulz S. Volatiles released by a Streptomyces species isolated from the North Sea. Chem Biodivers. 2005;2(7):837–65. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200590062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Korpi A, Jarnberg J, Pasanen AL. Microbial volatile organic compounds. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009;39(2):139–93. doi: 10.1080/10408440802291497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crespo E, de Ronde H, Kuijper S, et al. Potential biomarkers for identification of mycobacterial cultures by proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry analysis. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2012;26(6):679–85. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulz S, Dickschat JS. Bacterial volatiles: the smell of small organisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24(4):814–42. doi: 10.1039/b507392h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fowler SJ, Basanta-Sanchez M, Xu Y, Goodacre R, Dark PM. Surveillance for lower airway pathogens in mechanically ventilated patients by metabolomic analysis of exhaled breath: a case-control study. Thorax. 2015;70(4):320–5. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Oort PMP, de Bruin S, Weda H, et al. Exhaled Breath Metabolomics for the Diagnosis of Pneumonia in Intubated and Mechanically-Ventilated Intensive Care Unit (ICU)-Patients. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017;18(2):449. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Oort PM, Povoa P, Schnabel R, et al. The potential role of exhaled breath analysis in the diagnostic process of pneumonia-a systematic review. J Breath Res. 2018;12(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aaa499. 024001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bos LDJ, Sterk PJ, Schultz MJ. Volatile metabolites of pathogens: a systematic review. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9(5):e1003311–e. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ricciardolo FL, Sterk PJ, Gaston B, Folkerts G. Nitric oxide in health and disease of the respiratory system. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(3):731–65. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boots AW, Smolinska A, van Berkel JJ, et al. Identification of microorganisms based on headspace analysis of volatile organic compounds by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Breath Res. 2014;8(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/8/2/027106. 027106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cai J, Wang X, Ma A, Wang Q, Han X, Li Y. Factors associated with patient and provider delays for tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120088. e0120088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sreeramareddy CT, Qin ZZ, Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Pai M. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(3):255–66. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saktiawati AMI, Putera DD, Setyawan A, Mahendradhata Y, van der Werf TS. Diagnosis of tuberculosis through breath test: A systematic review. EBioMedicine. 2019;46:202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Syhre M, Chambers ST. The scent of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2008;88(4):317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Syhre M, Manning L, Phuanukoonnon S, Harino P, Chambers ST. The scent of Mycobacterium tuberculosis – Part II breath. Tuberculosis. 2009;89(4):263–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kramer R, Sauer-Heilborn A, Welte T, Guzman CA, Höfle MG, Abraham WR. A rapid method for breath analysis in cystic fibrosis patients. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2015;34(4):745–51. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scott-Thomas AJ, Syhre M, Pattemore PK, et al. 2-Aminoacetophenone as a potential breath biomarker for Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the cystic fibrosis lung. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2010;10:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Flake GP, Rivera MP, Funkhouser WK, et al. Detection of pre-invasive lung cancer: technical aspects of the LIFE project. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(1):65–74. doi: 10.1080/01926230601052659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chung-man Ho J, Zheng S, Comhair SA, Farver C, Erzurum SC. Differential expression of manganese superoxide dismutase and catalase in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61(23):8578–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mazzone PJ, Hammel J, Dweik R, et al. Diagnosis of lung cancer by the analysis of exhaled breath with a colorimetric sensor array. Thorax. 2007;62(7):565–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.072892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bajtarevic A, Ager C, Pienz M, et al. Noninvasive detection of lung cancer by analysis of exhaled breath. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:348. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Callol-Sanchez L, Munoz-Lucas MA, Gomez-Martin O, et al. Observation of nonanoic acid and aldehydes in exhaled breath of patients with lung cancer. Journal of breath research. 2017;11(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa6485. 026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Esteban JJ, Lucas MAM, Aranda BC, et al. Volatile organic compounds (VOC) in exhaled breath in patients with lung cancer, using the analytical technique thermal desorber-gase chromatography-spectrometer mases. European Respiratory Journal. 2012;40 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van Der Schee M, Gaude E, Boschmans J, et al. MS29.04 LuCID Exhaled Breath Analysis. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2018;13(10):S302. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang H-Y, Shie R-H, Chang C-J, Chen P-C. Development of breath test for pneumoconiosis: a case-control study. Respiratory research. 2017;18(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0661-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Anhenn O, Rabis T, Sommerwerck U, et al. Detection of differences in volatile organic compounds (VOCs) by ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) of exhaled breath in patients with interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) compared to healthy controls (HC) European Respiratory Journal. 2011;38(Suppl 55):4772. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Incalzi RA, Pennazza G, Scarlata S, et al. Comorbidity modulates non invasive ventilation-induced changes in breath print of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients. Sleep and Breathing. 2015;19(2):623–30. doi: 10.1007/s11325-014-1065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dragonieri S, Quaranta VN, Carratu P, Ranieri T, Resta O. Exhaled breath profiling by electronic nose enabled discrimination of allergic rhinitis and extrinsic asthma. Biomarkers : biochemical indicators of exposure, response, and susceptibility to chemicals. 2018:1–24. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2018.1508307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ibrahim W, Wilde M, Cordell R, et al. Assessment of breath volatile organic compounds in acute cardiorespiratory breathlessness: a protocol describing a prospective real-world observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025486. e025486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shafiek H, Fiorentino F, Merino JL, et al. Using the Electronic Nose to Identify Airway Infection during COPD Exacerbations. PLoS One. 2015;10(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135199. e0135199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Douglas IS. Pulmonary infections in critical/intensive care - rapid diagnosis and optimizing antimicrobial usage. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2017;23(3):198–203. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Phillips M, Greenberg J, Awad J. Metabolic and environmental origins of volatile organic compounds in breath. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47(11):1052–3. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.11.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Browne MW. Cross-Validation Methods. Journal of mathematical psychology. 2000;44:108–32. doi: 10.1006/jmps.1999.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Phillips M, Erickson GA, Sabas M, Smith JP, Greenberg J. Volatile organic compounds in the breath of patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48(5):466–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Van Der Schee MP, Liley J, Palmay R, Cowan J, Taylor D. Predicting steroid responsiveness in patients with asthma using the electronic nose. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;185 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brinkman P, van de Pol MA, Gerritsen MG, et al. Exhaled breath profiles in the monitoring of loss of control and clinical recovery in asthma. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017;47(9):1159–69. doi: 10.1111/cea.12965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shafiek H, Fiorentino F, Merino JL, et al. Using the Electronic Nose to Identify Airway Infection during COPD Exacerbations. PloS one. 2015;10(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135199. e0135199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ibrahim B, Basanta M, Cadden P, et al. Non-invasive phenotyping using exhaled volatile organic compounds in asthma. Thorax. 2011;66(9):804–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.156695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schnabel R, Fijten R, Smolinska A, et al. Analysis of volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath to diagnose ventilator-associated pneumonia. Scientific reports. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep17179. 17179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Allers M, Langejuergen J, Gaida A, et al. Measurement of exhaled volatile organic compounds from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using closed gas loop GC-IMS and GC-APCI-MS. Journal of breath research. 2016;10(2) doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/2/026004. 026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Martinez-Lozano Sinues P, Meier L, Berchtold C, et al. Breath analysis in real time by mass spectrometry in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2014;87(4):301–10. doi: 10.1159/000357785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Westhoff M, Litterst P, Maddula S, et al. Differentiation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) including lung cancer from healthy control group by breath analysis using ion mobility spectrometry. International Journal for Ion Mobility Spectrometry. 2010;13(3-4):131–9. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Van Berkel JJ, Dallinga JW, Moller GM, et al. A profile of volatile organic compounds in breath discriminates COPD patients from controls. Respir Med. 2010;104(4):557–63. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cazzola M, Segreti A, Bergamini A, et al. Analysis of exhaled breath fingerprints and volatile organic compounds in COPD. COPD Research and Practice. 2015;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- 113.Paredi P, Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Elevation of exhaled ethane concentration in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(4 Pt 1):1450–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.2003064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cazzola M, Segreti A, Capuano R, et al. Analysis of exhaled breath fingerprints and volatile organic compounds in COPD. COPD Research and Practice. 2015;1(1):7. [Google Scholar]