Abstract

We repurposed a terminal uridylyl transferase enzyme to site-specifically label RNA with microenvironment sensing fluorescent nucleotide mimics, which in turn provided direct read-outs to estimate the binding affinities of the enzyme to RNA and nucleotide substrates. This enzyme–probe system provides insights into the catalytic cycle, and can facilitate the development of discovery platforms to identify robust enzyme inhibitors.

Recent advances in epitranscriptomics indicate that posttranscriptional RNA modifications serve as key metabolic switches in controlling gene expression by modulating the stability, processing and degradation of transcripts.1 One such important class of modification, which is analogous to polyadenylation of pre-mRNA,2–4 is the addition of uridine(s) by terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase) or poly (U) polymerase (PUP).5 These enzymes catalyze the non-templated addition of uridines at the 3’-end of coding and non-coding RNAs and control their stability and degradation.6–8 Identification of 3’ uridylation of novel RNAs within the epitranscriptome by these enzymes has aided the discovery of new obscure pathways of RNA regulation.9,10 Importantly, these enzymes give access to downstream control of therapeutic RNA substrates, and are therefore, considered as new drug targets.8 For example, polyuridylation activity of the human TUTase 4 (TUT4) results in tumorigenesis as it reduces the stability of the let-7 family of miRNAs, which are responsible for negative regulation of oncogenes.11–13 Similarly, the cell viability of Trypanosoma brucei, a parasite that causes Human African Trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) and Chagas disease for which current therapies are inadequate, greatly relies on polyuridylation and RNA editing activity of TUTase (RET1).14,15 Currently there are no clinically viable small molecule candidates that target and inhibit the activity of TUTase, and hence, there is imminent interest in this direction.

A conventional method for the detection of the uridylation activity of TUTase employs indirect measurement of the bispyrophosphate byproduct using a coupled assay with pyruvate phosphate dikinase and luciferase.15 This method has also been used in setting up screening assays to identify inhibitors of human TUT4 and parasite RET1.11,15 Here, we report the use of an innovative approach wherein a TUTase (SpCID1: Schizosaccharomyces pombe caffeine-induced death suppressor 1) has been repurposed to efficiently label RNA with very useful environment-sensitive fluorescent UTP analog probes, which in turn enabled the development of a fluorescence displacement assay that would facilitate the identification of pharmacological agents competing for the active site (Fig. 1). Furthermore, a comparison of the binding affinities of the nucleotide analog, nucleotide-labeled RNA oligonucleotide (ON) and natural substrate (UTP) provided insights into the catalytic cycle of SpCID1. Notably, this approach has two advantages—(i) RNA labeled with probes for nucleic acid analysis can be generated, and (ii) since the fluorescent UTP probe binds strongly, only very strong binders would be able to displace the nucleotide analog from the active site, which essentially would enable robust clinically relevant TUTase inhibitors to be identified.

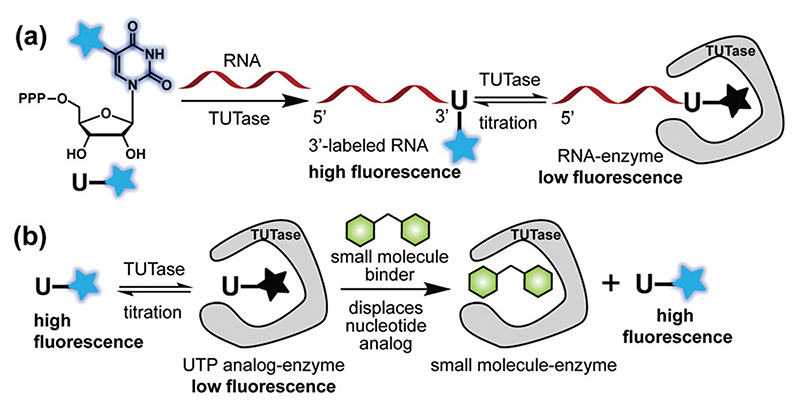

Fig. 1.

(a) TUTase efficiently incorporates UTP analogs (1 and 2, see Fig. 2) to generate 3′-end labeled RNA ONs exhibiting high fluorescence. Labeled RNA upon titration with the enzyme results in progressive quenching in fluorescence, which enables the determination of the binding constant. (b) The analog (e.g., 2) bound to the enzyme shows low fluorescence and the addition of a small molecule (e.g., UTP) displaces the analog resulting in an enhancement in fluorescence, which constitutes a simple turn-on fluorescent platform for the identification of TUTase binders/inhibitors.

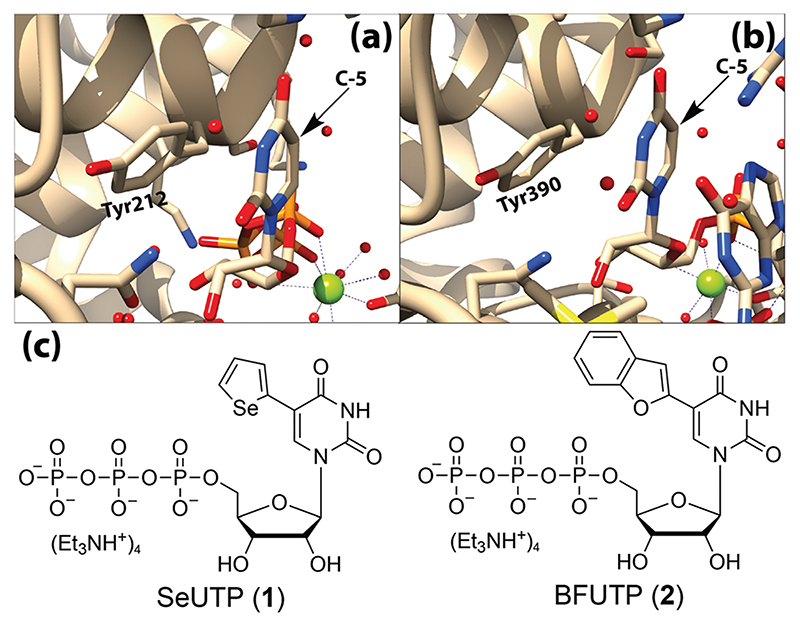

Careful analysis of the crystal structures of a cytoplasmic TUTase (SpCID1) enabled us to identify suitable nucleotide substrate analogs, which could serve as probes to setup a fluorescence assay to identify binders. Crystal structures of SpCID1 in the presence of UTP and a dinucleotide ApU reveal that the nucleotide at the active site is stabilized by a series of interactions with amino acids, and particularly by a tyrosine residue (Tyr212), which π stacks with the uracil base (Fig. 2a).16–18 Since the crystal structure of SpCID1 has not been solved with an RNA ON, a glance at the active site of a homologous TUTase, Drosophila melanogaster Tailor (DmTailor) with bound RNA, reveals similar π-stacking of the 3′-terminal nucleobase with the conserved tyrosine residue (Fig. 2b).19 These observations suggest that the conserved tyrosine (Tyr212 in SpCID1) is an important motif in TUTases for the binding of RNA and UTP. Furthermore, the crystal structures revealed a void space around the C5-position of uridine, which suggests that TUTase could promiscuously accept C5-modified UTP analogs as substrates in the uridylation reaction. We recently showed that SpCID1 can efficiently incorporate multiple C5-azide modified UTP analogs at the 3’ end of RNA ONs.20 Based on these key observations, we envisioned that 5-heterocycle-modified fluorescent UTP analogs would serve as smart substrate mimics by directly sensing the microenvironment of the active site without hampering the enzyme’s processivity. This setup will essentially enable realtime quantification of the probe binding to the enzyme and assist in devising a screening platform to identify potential inhibitors.21,22

Fig. 2.

(a) Crystal structure of SpCID1 bound to UTP showing uracil stacking with Tyr212 (PDB: 4FH5)17 (b) Crystal structure of DmTailor bound to RNA showing the last nucleobase, uracil stacking with Tyr390 (PDB: 6I0V).19 Vacant space around the C5-position of uracil can been seen in the structures. (c) Microenvironment sensing UTP analogs used in terminal uridylation reactions.

Among the various C5-modified fluorescent UTP analogs, we chose to use 5-selenophene UTP (1, SeUTP) and 5-benzofuran UTP (2, BFUTP) developed in our laboratory (Fig. 2c). These fluorescent analogs are highly sensitive to their microenvironment and serve as excellent probes in detecting ligand-induced conformational changes in bacterial ribosomal decoding site RNA and also in decoding conformational changes in the non- canonical nucleic acid structures.23–25 SeUTP is a dual purpose probe as it contains an anomalous scattering center (Se atom), which is useful in the X-ray analysis of nucleic acids.23,24 Furthermore, the excitation (~330 nm) and emission (~440 nm) maxima of the analogs are significandy red-shifted as compared to intrinsic fluorophores (tryptophan and tyrosine) present in SpCID1, and hence, should not interfere with the spectral readouts of the nucleotide analogs.

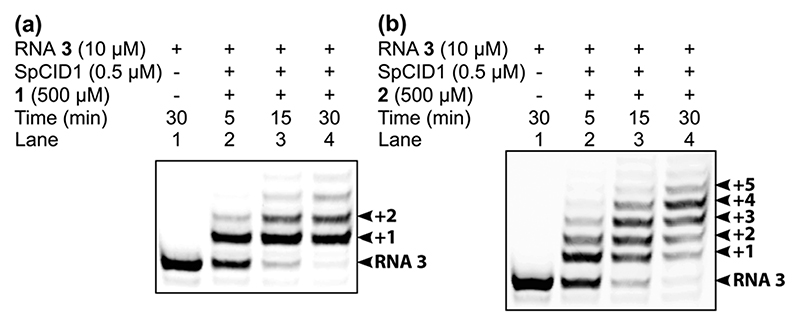

Terminal uridylation reactions were performed using 5′-FAM- labeled RNA ON 3 (1 equiv., Table 1) in the presence of modified UTPs, 1 or 2 (50 equiv.) and SpCID1 (0.05 equiv.), which was recombinantly expressed in E. coli. Uridylated ON products obtained at various time-points were resolved using PAGE under denaturing conditions and imaged using a fluorescence scanner at the FAM emission wavelength (Fig. 3). Rewardingly, as per our hypothesis, the C5-modified nucleotide analogs, SeUTP (1) and BFUTP (2), were found to be very good substrates in the SpCID1- catalyzed 3′-uridylation reactions. The enzyme incorporated SeUTP in a distributive fashion, which tends to saturate upon addition of a single modified nucleotide at the 3′-end (Fig. 3a, lane 4). In the distributive process, the enzyme dissociates from the RNA ON after each successive nucleotide addition resulting in RNA ONs containing a few added nucleotides.18 Previously, we had observed that performing terminal uridylation under similar conditions employing UTP and azide-modified UTPs with SpCID1 resulted in distributive enzyme addition.20 Interestingly, BFUTP exhibited multiple rounds of distributive incorporation with no visible saturation even after 30 min (Fig. 3b, lane 4). Discernably higher incorporation efficiency of a bulky nucleotide like BFUTP (4 or more nucleotides) indicates that the RNA ON products containing BFU(s) act as good substrates for further multiple enzymatic insertions unlike in the case of SeUTP. This might be a result of an additional molecular interaction of BFU or RNA products containing BFU with the SpCID1 active site, possibly π-π stacking interaction with Tyr212 as seen in the X-ray crystal structure (Fig. 2a and b, vide supra).17,19

Table 1. Sequence of RNA ONs.

| RNA ON | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 5′-FAM-labeled RNA ON 3 | 5′ FAM-UUACCAUAGAAUCAUGUGCCAUACAUCA 3′ |

| 3BFU | 5′ FAM-UUACCAUAGAAUCAUGUGCCAUACAUCA-BFU 3′ |

| Unlabeled RNA ON 4 | 5′ UUACCAUAGAAUCAUGUGCCAUACAUCA 3′ |

| 4BFU | 5′ UUACCAUAGAAUCAUGUGCCAUACAUCA-BFU 3′ |

Fig. 3.

3′ -Terminal uridylation of 5′-FAM-labeled RNA ON 3 with (a) SeUTP 1 and (b) BFUTP 2 using SpCID1. Arrows indicate the number of insertions at the 3’-end.

Next, we sought to optimize the reaction conditions to prepare an RNA ON labeled with a single BFU at the 3’-end (as it is a better substrate than SeU-labeled RNA ON, vide supra, Fig. 3) so as to investigate the interaction of the microenvironment sensing probe with the catalytic core of SpCID1 using fluorescence. 5’-FAM-labeled RNA ON 3 (1 equiv.) was incubated with a lower concentration of the enzyme (0.01 equiv.) and varying concentrations of BFUTP (1-5 equiv., Fig. S1a, ESI†). Since the substrate exhibited highly efficient distributive incorporation, we could not limit the reaction exclusively to a single BFU-labeled product. A reaction with 2 equivalents of BFUTP for 30 min gave ~40% of singly labeled product band (Fig. S1a, ESI†, lane 7). These results also allude to the point that RNA ON labeled with BFU is a better binder than native RNA ON, and hence, serves as a good substrate for sequential incorporation by the transferase enzyme. Multiple such reactions were performed using ON 3 and unlabeled RNA ON 4 to obtain reasonable amounts for further studies (Table 1 and Fig. S1b, ESI†). The desired ON products 3BFU and 4BFU were easily isolated using RP-HPLC (Fig. S1c, ESI†) and their integrity was confirmed using mass analysis (Fig. S2 and Table S1, ESI†). It is worth mentioning here that 3′-labeled RNA ONs could be ligated to another RNA ON, thereby achieving site-specific internal labeling of RNA.2 Furthermore, this method of synthesizing RNA ONs with multiple BFUs placed in neighboring positions could show interesting fluorescence properties due to cross-talk, which may find application as hybridization probes.26,27

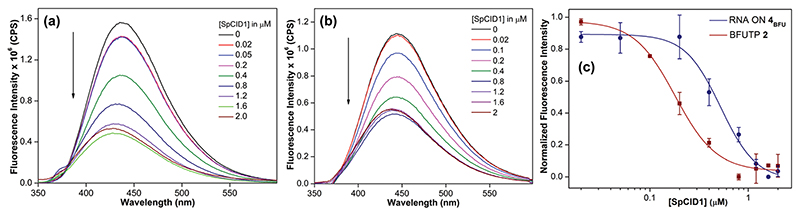

We then investigated whether the BFU probe on RNA and triphosphate can be used for quantifying the substrate binding to SpCID1. Upon exciting samples of RNA ON 4BFU containing varying concentrations of SpCID1 at 330 nm, a dose-dependent quenching in fluorescence intensity (~ 3-fold) accompanied by a small blue shift in emission maximum was observed (Fig. 4a). From our previous studies, it is known that BFU exhibits quenched and blue-shifted emission when it is stacked and placed in a less polar environment.25,28 Fitting the normalized fluorescence intensity as a function of enzyme concentration gave an apparent Kd of 0.52 ± 0.04 μM (Fig. 4c). Validating our design, BFU quantitatively reported the binding of the RNA substrate to the enzyme active site via changes in fluorescence, which is likely due to the stacking of BFU with Tyr212 and small variations in the micropolarity. The formation of an enzyme–RNA substrate complex was further proved using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). 5′-FAM, 3′-BFU-labeled RNA ON 3BFU was incubated with varying concentrations of SpCID1 and resolved using native PAGE. Fluorescence imaging of the gel (FAM channel) showed concentration-dependent formation of the binary complex, which gave a Kd of ~ 5.4 μM (Fig. S3, ESI†). This is in the range of Kd values (~1 μM and ~21 μM) reported for SpCID1 binding to 15 nucleotide homopolymers (U)15 and (A)15 obtained using EMSA.18 However, our probe provides a direct and efficient real-time read-out of the binding of the RNA substrate to SpCID1 in solution under equilibrium conditions.

Fig. 4.

Emission spectra of (a) BFU-labeled RNA ON 4BFU and (b) BFUTP 2 (200 nM) as a function of increasing concentration of SpCID1 (0–2 μM). (c) A plot of normalized fluorescence intensity at λem = 435 nm versus [SpCID1] showing the curve fit for the binding of 4BFU and 2 to SpCID1. See ESI† for details.

To confirm that the changes in fluorescence are due to the specific interaction of 3′-BFU-labeled RNA ON at the active site, a competitive binding assay was performed wherein the SpCID1 and ON 4BFU complex were titrated with increasing concentrations of control unlabeled RNA ON 4. Increasing concentrations of 4 resulted in a progressive increase in fluorescence intensity with a minor red-shift in emission maximum, which suggests that 4 competes with 4BFU for binding to the enzyme’s active site (Fig. S4a, ESI†). However, even a 10-fold excess concentration of the unlabeled ON 4 could not completely recover the fluorescence, which again indicates that BFU-labeled RNA ON binds more tightly to SpCID1.

Similarly, the binding of BFUTP 2 to the enzyme was determined by titrating the fluorescent nucleotide probe with increasing concentrations of SpCID1. As before, we observed a concentration-dependent quenching in fluorescence intensity along with a minor blue shift in the emission maximum, which enabled the determination of Kd (0.18 ± 0.04 μM, Fig. 4b and c). To detect the binding of UTP and also establish a fluorescence displacement assay, a SpCID1–BFUTP complex was titrated with increasing concentrations of UTP. If UTP competitively binds to the active site, then fluorescence will be turned-on as a result of release of more emissive free nucleotide analogs. Though addition of UTP displaced BFUTP from the active site, even a 200-fold excess of UTP was not sufficient to completely recover the fluorescence (Fig. S4b, ESI†). It is clear that BFUTP binds significantly better as compared to BFU-labeled and unlabeled RNA ONs, which implies that in the catalytic cycle, BFUTP should bind to the active site first and then the RNA substrate, which subsequently gets uridylated. In the second and subsequent uridylation cycles, BFUTP binding is followed by BFU-labeled RNA ON, which gets tailed distributively with BFU. A similar pathway has been proposed for this reaction,29 but here we provide experimental evidence.

In summary, we have devised a useful platform to study the recognition properties of an important class of RNA processing enzyme, namely TUTase, using a microenvironment-sensing fluorescent nucleotide substrate mimic (BFUTP). The analog is efficiently incorporated by SpCID1 and the addition of multiple bulky modified uridylates on RNA does not majorly compromise the enzyme’s processivity. Both the substrates, BFUTP (2) and BFU-labeled RNA ON (4BFU), serve as probes in estimating substrate binding to the active site. Importantly, the affinity of the nucleotide probe to TUTase is in the nanomolar range, and hence, only very strong binders will be able to displace BFUTP from the active site and turn-on the fluorescence signal. Therefore, the responsiveness of the probe can be used to setup a robust competitive displacement screening assay to identify highly efficient small-molecule binders of TUTase. In terms of therapeutic utility, this platform provides two options. Identified high affinity binders could be (i) competitive inhibitors, which could be used to block the maturation of pathogenic RNA substrates or (ii) excellent substrates like BFUTP, in which case the matured RNA may not be functionally competent for downstream processes. Furthermore, this approach of using substrates as probes can be expanded to investigate other DNA/ RNA processing enzymes, and research in this direction is in progress in our laboratory.

We thank Rupam Bhattacharjee for his help in the mass analysis of RNA ONs. J. T. G. thanks IISER Pune and Wellcome Trust-DBT India Alliance for the graduate research fellowship. Support received from Wellcome Trust-DBT India Alliance (IA/S/16/1/502360) by S. G. S for this work is acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. Cell. 2017;169:1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winz M-L, Samanta A, Benzinger D, Jaschke A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e78. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anhauser L, Huwel S, Zobel T, Rentmeister A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:e42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westerich KJ, Chandrasekaran KS, Gross-Thebing T, Kueck N, Raz E, Rentmeister A. Chem Sci. 2020;11:3089–3095. doi: 10.1039/c9sc05981d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rissland OS, Mikulasova A, Norbury CJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3612–3624. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02209-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munoz-Tello P, Rajappa L, Coquille S, Thore S. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:968127. doi: 10.1155/2015/968127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zigáčková D, Vaňáčová Š. Philos Trans R Soc, B. 2018;373:20180171. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menezes MR, Balzeau J, Hagan JP. Front Mol Biosci. 2018;5:1–20. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2018.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim B, Ha M, Loeff L, Chang H, Simanshu DK, Li S, Fareh M, Patel DJ, Joo C, Kim VN. EMBO J. 2015;34:1801–1815. doi: 10.15252/embj.201590931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung CZ, Jaramillo JE, Ellis MJ, Bour DYN, Seidl LE, Jo DHS, Turk MA, Mann MR, Bi Y, Haniford DB, Duennwald ML, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:3045–3057. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin S, Gregory RI. RNA Biol. 2015;12:792–800. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1058478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagan JP, Piskounova E, Gregory RI. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornton JE, Chang H-M, Piskounova E, Gregory RI. RNA. 2012;18:1875–1885. doi: 10.1261/rna.034538.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajappa-Titu L, Suematsu T, Munoz-Tello P, Long M, Demir Ö, Cheng KJ, Stagno JR, Luecke H, Amaro RE, Aphasizheva I, Aphasizhev R, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:10862–10878. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cording A, Gormally M, Bond PJ, Carrington M, Balasubramanian S, Miska EA, Thomas B. RNA Biol. 2017;14:611–619. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1137422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yates LA, Fleurdépine S, Rissland OS, De Colibus L, Harlos K, Norbury CJ, Gilbert RJC. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:782. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunde BM, Magler I, Meinhart A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9815–9824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz-Tello P, Gabus C, Thore S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:3372–3380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroupova A, Ivaşcu A, Jinek M, Reimâo-Pinto MM, Ameres SL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:1030–1042. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George JT, Azhar M, Aich M, Sinha D, Ambi UB, Maiti S, Chakraborty D, Srivatsan SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142:13954–13965. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c06541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie Y, Maxson T, Tor Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11896–11897. doi: 10.1021/ja105244t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hafner M, Schmitz A, Grüme I, Srivatsan SG, Paul B, Kolanus W, Quast T, Kremmer E, Bauer I, Famulok M. Nature. 2006;444:941–944. doi: 10.1038/nature05415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuthanakanti A, Boerneke MA, Hermann T, Srivatsan SG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017;56:2640–2644. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuthanakanti A, Ahmed I, Khatik SY, Saikrishnan K, Srivatsan SG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:6059–6072. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanpure AA, Srivatsan SG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang S, Guo J, Ono T, Kool ET. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:7176–7180. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noée MS, Sinkeldam RW, Tor Y. J Org Chem. 2013;78:8123–8128. doi: 10.1021/jo4008964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabale PM, George JT, Srivatsan SG. Nanoscale. 2014;6:10460–10469. doi: 10.1039/c4nr00878b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durrant BP, Harlos K, Yates LA, Gilbert RJC, Fleurdéepine S, Norbury CJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:2968–2979. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.