Abstract

Migraine is a common and disabling neurological disorder, with important psychiatric comorbidities. Its pathophysiology involves activation of neurons in the trigeminocervical complex (TCC). Kainate receptors carrying the glutamate receptor subunit 5 (GluK1) are present in key brain areas involved in migraine pathophysiology. To study the influence of kainate receptors on trigeminovascular neurotransmission, we determined the presence of GluK1 receptors within the trigeminal ganglion and TCC with immunohistochemistry. We performed in vivo electrophysiological recordings from TCC neurons and investigated whether local or systemic application of GluK1 receptor antagonists modulated trigeminovascular transmission. Microiontophoretic application of a selective GluK1 receptor antagonist, but not of a non-specific ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, markedly attenuated cell firing in a subpopulation of neurons activated in response to dural stimulation, consistent with selective inhibition of post-synaptic GluK1 receptor-evoked firing seen in all recorded neurons. In contrast, trigeminovascular activation was significantly facilitated in a different neuronal population. The clinically active kainate receptor antagonist LY466195 attenuated trigeminovascular activation in all neurons. In addition LY466195 demonstrated an NMDA receptor-mediated effect. The current study demonstrates a differential role of GluK1 receptors in the TCC, antagonism of which can inhibit trigeminovascular activation through post-synaptic mechanisms. Further, the data suggests a novel, possibly pre-synaptic, modulatory role of trigeminocervical kainate receptors in vivo. Differential activation of kainate receptors suggests unique roles for this receptor in pro- and antinociceptive mechanisms in migraine pathophysiology.

Keywords: kainate receptor, migraine, trigeminovascular activation, microiontophoresis

1. Introduction

Migraine is the most common cause of neurological disability worldwide [41]. It is costly [42], and whilst its pathophysiology is incompletely understood, it is thought to involve activation of the trigeminal afferents [22]. Glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, has been implicated in migraine pathophysiology through experimental work [7; 23; 39], human biomarker studies [19] and by results of clinical trials [1; 45]. Given well recognised side effects of actions at the glutamate NMDA receptor, attention has moved to other targets.

The kainate receptor is a member of the ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluR) family, consisting of the GluK1-5, [15], which can form multimeric assemblies giving rise to functional receptor-channels [14]. In vitro experiments have demonstrated kainate receptors function as mediators and modulators of synaptic transmission and plasticity by regulating post-synaptic currents [11] and pre-synaptic neurotransmitter release [31]. Increasing evidence has shown activation and modulation of kainate receptors by nociceptive stimuli [46]. The presence of functional kainate receptors in dorsal root ganglia [2], trigeminal ganglion [47] and in both pre- and post-synaptic sites in superficial laminae of the spinal cord and caudal brainstem [24; 35; 37], indicates their potential importance.

Non-selective α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA)/kainate receptor antagonists have been shown to produce anti-nociceptive effects in both animal [39] and human studies [48]. Competitive GluK1-selective receptor antagonists were effective in blocking trigeminal activation after stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion [20; 50]. In a double-blind controlled study the GluK1 receptor antagonist LY466195 was effective in relieving pain in acute migraine [28]. Topiramate, a partial kainate receptor antagonist [17], is a clinically effective migraine preventive [12] and has been shown to reduce trigeminovascular and thalamic activation and to inhibit cortical spreading depression in the mammalian cortex [3; 4; 6].

Here we aimed to examine the role of GluK1 kainate receptors in trigeminovascular nociceptive processing. We used microiontophoresis to investigate the effects of GluK1 agents directly on second order trigeminocervical neurons, utilizing the GluK1 receptor antagonist UBP302 and the clinically active GluK1 receptor antagonist LY466195 [50]. We further examined the effects of intravenous LY466195 on responses of neurons in the TCC to mimic the peripheral administration of the drug clinically.

2. Methods

All experiments were conducted under the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) and approved by the University of California San Francisco, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1. Surgical preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 55; 300-370 g) were anesthetized with 60 mgkg-1 pentobarbital intraperitoneally and then maintained with pentobarbital infusion (25-35 mgkg-1h-1). The left femoral artery and both femoral veins were cannulated for blood pressure recordings and infusion of anesthetic, neuromuscular blocker and test compounds, respectively. Animals were positioned on a rat stereotaxic frame and ventilated with oxygen-enriched air (Harvard Apparatus, Ltd., Edenbridge, Kent, UK). Throughout the experiments, the end-tidal CO2 was monitored (Capstar-100; CWE Inc., Ardmore, PA) and blood pressure were monitored and stable. Blood gases were measured at intervals and were within normal limits: arterial blood pH 7.37 ± 0.06 and pCO2 3.70 ± 0.42 kPa. The dura mater/middle meningeal artery (MMA) complex was accessed through a craniotomy. A hemi-C1 laminectomy exposed the brainstem at the level of the caudal medulla. Depth of anesthesia was judged by the absence of paw withdrawal and corneal blink reflex and by the lack of fluctuations in blood pressure during muscular paralysis.

2.2. Stimulation of MMA and Recordings from TCC

Stimulation of the MMA was performed by using a bipolar stimulating electrode and the lowest possible stimulus intensity was used (10-16 V; 0.5 Hz; 100 μs duration). Extracellular recordings were made from second order neurons in the region of the TCC, using microiontophoretic electrodes (Kation Scientific, Minneapolis, MN, USA) consisting of a seven-barrelled glass pipette and incorporating a carbon fiber recording electrode (impedance @ 1 kHz: 0.4-0.8 MΩ). The signal from the recording electrode was fed via a head stage amplifier (NL100AK, Neurolog, Digitimer, Herts, UK), to a series of filters and amplifiers and data collected Spike2v5 software (CED, Cambridge UK). Post-stimulation histograms were constructed, as the sum of a total of 25 stimuli in order to record the response of units to electrical stimulation of the MMA as previously described [6]. Background cellular activity was continuously monitored via peri-stimulus histograms. Neuronal action potential firing in response to microiontophoresis of glutamate receptor agonists was analyzed as cumulative rate histograms.

Receptive fields

The cutaneous receptive field was assessed in all three dermatomes of the trigeminal innervations as the recording electrode was advanced in the spinal cord. The receptive field was assessed for both non-noxious, with gentle brushing, and noxious inputs by pinching with forceps and light brush of the cornea. When a neuron sensitive to noxious stimulation of the ophthalmic dermatome was identified, it was tested for convergent input from the dura mater. All recorded neurons were wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons responding to both innocuous and noxious stimulation of the ophthalmic dermatome.

2.3. Drugs

Freshly prepared solutions of LY466195 (50, 100 and 200 μgkg-1), were intravenously infused over one minute at least ten minutes after three consistent baseline responses to electrical stimulation of the MMA.

Seven-barrel carbon-fiber electrodes were used to deliver by microiontophoresis freshly prepared solutions of glutamate receptor agents using a current generator (Dagan 6400, Dagan Corporation, MN, USA).

Micropipette barrels were filled with 25 mM of the GluK1 receptor antagonist (S)-1-(2-Amino-2-carboxyethyl)-3-(2-carboxybenzyl)pyrim idine-2,4-dione (UBP302; Tocris Cookson Ltd., Bristol, UK), 25 mM of the GluK1 receptor antagonist (3S,4aR,6S,8aR)-6-[[(2S)-2-carboxy-4,4-difluoro-1-pyrrolidinyl]-methyl]de cahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxylic acid (LY466195; kindly provided by Lilly Laboratories), 10 mM of the non-selective ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; Tocris), 200 mM L-glutamate monosodium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 25 mM of the GluK1 receptor agonist iodowillardiine (Tocris), 25 mM of the AMPA agonist fluorowillardiine (Tocris), 50 mM of the GluK1/2 receptor agonist (2S,4R)-4-Methylglutamic acid (SYM 2081; Tocris), 100 mM N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA; Tocris), 200 mM D-serine (Tocris), Pontamine sky blue dye (Gurr 6BX, BDH Laboratory Supplies, Poole, UK; 2.5% w/v in 100 mM sodium acetate; pH 6.5). All compounds were ejected as anions (5-100 nA) and retained with small positive currents. Saline was used as a control and represents the ejection of both Cl- and OH- ions, since the pH of the saline was adjusted by the addition of 0.01 M NaOH. Current balance was provided through a barrel containing 200 mM NaCl. Microiontophoretic barrels had resistances of 9-100 MΩ.

2.4. Experimental protocol

Trigeminal responses were recorded and challenged by kainate receptor antagonists intravenously (LY466195) or locally by microiontophoresis into the TCC (LY466195, UBP302, CNQX). For each intravenous treatment, MMA stimulation-evoked firing was recorded before (three baselines) and 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90 minutes after the LY466195 or saline control were injected. For the iontophoretic studies, once neurons were identified by their response to ophthalmic facial receptive field stimulation, they were tested for a stable response to electrical stimulation of the MMA and an increased firing rate to microintophorised glutamate receptor agonists. Three baseline responses to MMA stimulation were collected five minutes apart. The glutamate receptor agonists tested for each experiment were ejected in a random order and once five stable baseline cycles were recorded, then UBP302 (10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 100 nA) or LY466195 (5, 10, 20 nA) or their control ions (Cl-, OH-) were ejected with each current applied during individual ejecting cycles of agonists. CNQX or vehicle control (Cl-, OH-) was applied at 20 nA over three cycles of glutamate receptor agonists. A post-stimulus histogram was collected during each ejecting current of the antagonists or their controls, and at the end of the recovery period.

To assess the effects of the antagonists on noxious and non-noxious stimulation of the cutaneous facial receptive field, light touch, noxious pinch and corneal brush were randomly applied during baseline cycles, during each ejecting current of the antagonists or their controls, and following the recovery period. At the conclusion of the antagonist or vehicle control ejection, agonists’ cycles were continued for 15-30 minutes and the neuronal responses were observed. The location of the recording site was obtained by either direct marking of the site by ejection of charged pontamine sky blue via a BAB-350 pump (Kation), or by reconstruction from a marked reference point and microdrive readings. Upon termination of the experiment, the tissue was removed and processed for histological verification using the brain atlas by Paxinos and Watson [43].

2.5. Tissue processing and Immunohistochemistry

Untreated control male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 3) weighing 310-330 g were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p) and perfused through the left ventricle with 200 ml of heparinized saline, followed by 500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer saline (PBS 0.1 M, pH 7.4, 4 °C). The trigeminal ganglia and the lower brainstem including the upper cervical segments were removed and cryoprotected at 4-8 °C in sucrose solution (30% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS with 0.1% sodium azide) until saturated. One trigeminal ganglion was cut per animal into 20 μm sections and mounted on slides. The brainstem was sectioned in 40 μm sagittal sections and processed as free floating in PBS.

Sections were first left for 10 minutes in a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution for blocking endogenous peroxidase activity, following by 1 h incubation with 10% normal goat serum in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBS++; Vector, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature. This was followed by a 2-step avidin-biotin blocking solution (Vector) for 30 minutes to block nonspecific binding sites and a 48h incubation at 4°C with a solution of rabbit-raised antibody against the amino acids CHQRRTQRKETVA of rat GluK1 subunit located in the intracellular C-terminal (1:250; Millipore, Billerica, MA), made up in 2% normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBS+). This was followed by incubation for 90 minutes at room temperature in goat-raised biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500; Vector) in PBS+. Following, the sections were incubated for 30 minutes with an avidin-biotin peroxidise complex (ABC, Vectastain ABC kitA, Vector), and further incubated with the biotinylated tyramide solution (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) for 5 min, followed by 1 h incubation in fluoroscein avidin-D (1:500; Vector) made up in PB+ at room temperature. Direct immunohistofluorescence was used for double labelling for calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). After blocking the sections in PB++, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in a previously validate mouse anti-CGRP primary antibody (1:2000; the epitope recognized by the antibody resides within the C-terminal ten amino acids of rat α-CGRP; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) [38], and then incubated for 1h at room temperature with anti-mouse avidin coupled to Texas Red in PB+ (1:500; Vector). Sections were then rinsed, airdried, covered with mounting medium (Vector), and examined using a Zeiss Axioplan Universal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). All steps mentioned above were separated with thorough washes using PBS. Negative control samples were obtained by omitting the primary or secondary antibodies. Sections from the trigeminal ganglia were used as positive controls.

2.6. Data analysis

To compare the effect of systemic administration of LY466195, the recorded data after the intravenous injection of LY466195 and saline were converted to a percentage of the average of the three baselines. The effects of the drugs over time and the interaction of both the drug used and time were evaluated using an analysis of variance with repeated measures followed by Bonferroni tests. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction of the degrees of freedom was applied when the assumption of sphericity was not met. A paired t test (LY466195 vs saline) was used to compare further each time point.

For microiontophoresis experiments, the statistical analysis was conducted as described previously [8].Briefly, the response of each cell for each glutamate agonist under test conditions was examined as followed: (a) iGluR agonist (baseline), (b) iGluR co-ejected with an antagonist or control ions (Cl- and OH-) at increasing doses (c) iGluR agonist (recovery). Five baseline pulses of iGluR agonists were analyzed to avoid variations of the responses of a cell between individual pulses and the reliability of the measurements was tested using Cronbach’s alpha (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The baseline response probability to MMA or cutaneous receptive field stimulation was calculated from up to three post-stimulus histograms and peristimulus histograms respectively, and repeated during treatment with antagonist or control, separately for each current and following recovery period. Effects of antagonist or vehicle control interventions were analyzed using an ANOVA for repeated measures followed by paired t-test with Bonferroni post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons, using the average of the baselines of all tested parameters for comparisons. An independent t-test was used to compare the effects of the antagonist UBP302 over two different neuronal subpopulations (see results). Data are expressed as mean percentage of the baseline response ± SEM and significance was assessed at the P < 0.05 levels.

3. Results

3.1. Immunohistochemistry

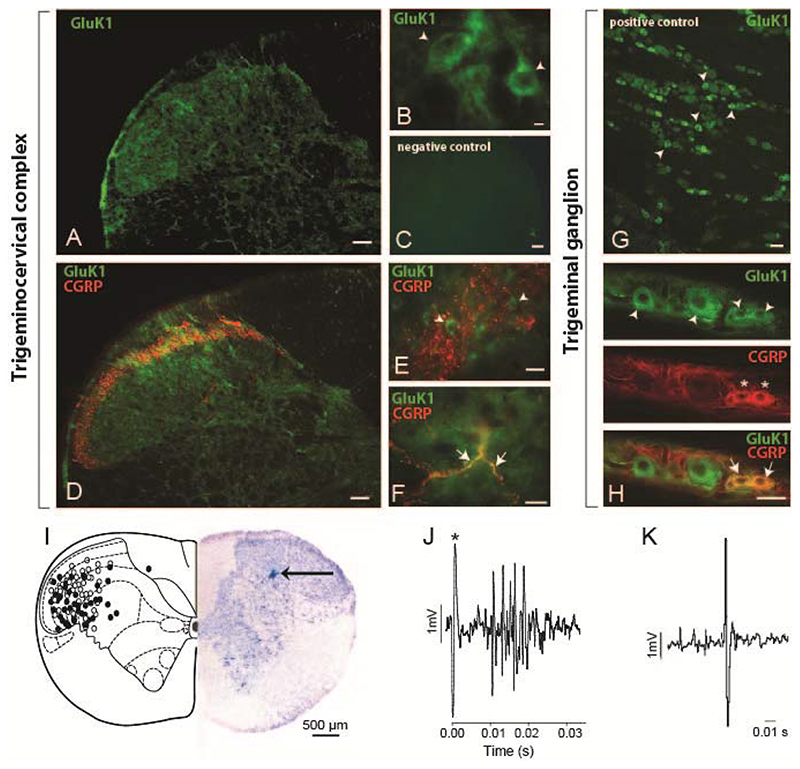

The qualitative analysis of immunofluorescent stained sections revealed GluK1 receptors throughout the TCC (Figure 1A, B, D-F). Cell bodies and punctate staining was evident in laminae I-III and mainly cell bodies were seen in deeper laminae. Stained cells were round or pear-shaped and ranged in diameter size from 15 to 26 μm. Within lamina I and outer lamina II, where CGRP positive fibers project, GluK1-like staining was seen in cell bodies (Figure 1E) as well as in punctate staining, which might represent proximal processes or GluK1-like primary fibers as some colocalization with CGRP-like fibers was seen (Figure 1F).The presence of GluK1-like receptors within primary fibers arising from the trigeminal ganglia is very likely, as many trigeminal neurons, mainly of medium and small size, were GluK1 positive (Figure 1G) as previously reported [47]. Some co-localization with CGRP-positive neurons was also seen (Figure 1H), mainly in small size neurons (~25-30%).

Figure 1. GluK1-like immunofluorescent staining within the trigeminocervical complex and trigeminal ganglia, and reconstruction of recording sites.

A-B. Photomicrographs of the trigeminocervical complex taken from the C1level, showing GluK1-like staining (green). Cell bodies and punctate staining was evident in laminae I-III and mainly cell bodies were seen in deeper laminae. Stained cells were round or pear-shaped. D-F. Within lamina I and outer lamina II, where calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-like fibers project (red), GluK1-like staining (green) was seen in cell bodies as well as in punctate staining, which might represent proximal processes or GluK1 primary fibers as some co-localization (yellow) with CGRP was seen (Figure 1G). C. A photomicrograph of a negative control section of the TCC. G. A photomicrograph of GluK1-like cells (green) within the trigeminal ganglion. H. GluK1-like cells (green) mainly co-localized with small size CGRP-positive cells (red) within the trigeminal ganglion. Arrowheads present examples of GluK1-like positive cells, stars indicate CGRP-like positive cells and arrows show co-localization of CGRP- and GluK1-like fibers (F) or cells (H). Scale bars = 100 μm (A, C, D), 50 μm (E, G, H), 10 μm (B, F). I. Reconstruction of recording sites within the C1 spinal cord level, plotted after Paxinos and Watson [43], identified histologically (solid circles represent pontamine sky blue spots) and by microdrive readings (open circles). A photomicrograph demonstrating an original recording site marked by ejection of pontamine sky blue (arrow) is shown. J. An original trace showing a cluster of cells in the trigeminocervical complex, firing in response to stimulation of the middle meningeal artery (100 μs, 0.5 Hz, 12 volts; * stimulus artefact). K. Original tracing from a neuron in the trigeminocervical complex responding to microiontophoresis of L-glutamate.

3.2. Localization and neuronal characteristics

A total of 98 wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons were studied from the TCC (Figure 1I) and each displayed convergent trigeminal viscerosomatic inputs of the ophthalmic dermatome. Only cell bodies identified by the size and shape of the action potential in response to glutamate receptor agonists microiontophoresis were recorded (Figure 1K). Extracellular recordings were made from neurons responding in a reversible excitatory manner to all iGluR agonists tested and to MMA electrical stimulation with latencies consistent with Aδ fibers (average latency 8-12 ms; Figure 1J). No unit was studied with more than one antagonist, and between one and three units were studied per animal.

3.3. Effects of intravenous LY466195 on middle meningeal artery-stimulation evoked activity

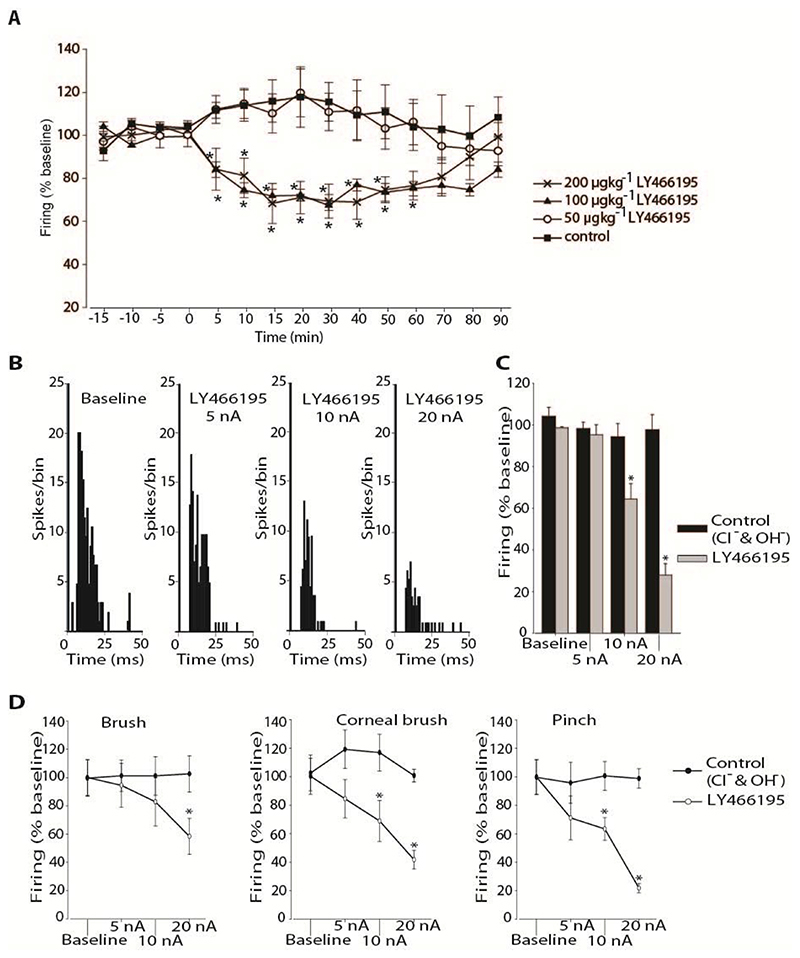

LY466195 administered intravenously significantly inhibited trigeminocervical activity in response to MMA stimulation at a dose of 100 μgkg-1 (n = 7; P < 0.05; Figure 2A) by a maximum of 33 ± 2% (t 12 = 4.48, P < 0.05). LY466195 at 200 μgkg-1 significantly decreased responses (n = 5; P < 0.05) at similar levels as the 100 μgkg-1 dose by a maximum of 32 ± 9% (t 6 = 4.20, P < 0.05; Figure 2A) and there was no significant difference between the effects induced by the two doses (P ≥ 0.40). Cell firing returned to baseline levels within 90 minutes. At the dose of 50 μgkg-1 LY466195 did not display a significant effect on cell firing (n = 5; P = 0.13).

Figure 2.

A. Effect of intravenously administrated LY466195 on responses of trigeminocervical neurons to middle meningeal artery stimulation. LY466195 inhibited firing to dural electrical stimulation at 200 and 100 μgkg-1, but not at 50 μgkg-1. Saline control ejection had no effect on neuronal firing. * P < 0.05 B. Effect of microiontophoresis of LY466195 on responses of trigeminocervical neurons to middle meningeal artery stimulation and to receptive field characterisation. Example of post-stimulus histograms from a representative neuron, recorded during baseline conditions and during ejection of LY466195 at currents 5, 10 and 20 nA. C. Comparison of the middle meningeal artery stimulation evoked firing under each condition. Ejection of LY466195 demonstrated a dose dependent inhibition of the cell firing, maximally at 20 nA. D. Effects of microiontophoretically delivered LY466195 and its vehicle control (Cl-, OH-) on the firing rates of second order neurons in response to receptive field characterisation. Microiontophoretic application of LY466195 at 20 nA significantly inhibited firing to both innocuous (brush) and nocuous (corneal brush; pinch) stimulation of the ophthalmic dermatome, while a lower ejection current (10 nA) significantly inhibited noxious stimulation of the receptive field. * P < 0.05

Intravenous administration of vehicle control had no effect on firing in response to MMA stimulation (n = 7; P = 0.18; Figure 2A). In all animals neither intravenous administration of LY466195 nor saline control produced any changes on blood pressure.

3.4. Effects of microiontophoretic administration of LY466195 on trigeminal neuronal firing

Effect on MMA and receptive field stimulation

Ejection of LY466195 significantly inhibited cell firing in response to MMA stimulation (n = 8; P < 0.005; Figure 2B, C) in all neurons tested in a current-dose dependent manner by a maximum of 72 ± 6% (t7 = 4.65, P < 0.05) post LY466195.

LY466195 significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner evoked firing to both innocuous (brush) and noxious (pinch and corneal brush) mechanical stimulation of the ophthalmic facial cutaneous receptive field in all neurons tested (n = 6; Figure 2D).

3.4.1. Effects of microiontophoretic application of LY466195 on post-synaptic firing evoked by glutamate agonists

LY466195 was applied by microiontophoresis on cells firing in response to the agonists NMDA (NMDA receptor agonist), fluorowillardiine (AMPA receptor agonist) and iodowillardiine (GluK1 kainate receptor agonist). For all three agonists tested there was no difference across the mean firing of the five repeated epochs recorded during baseline (n = 8) and all responses were reliable (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.94).

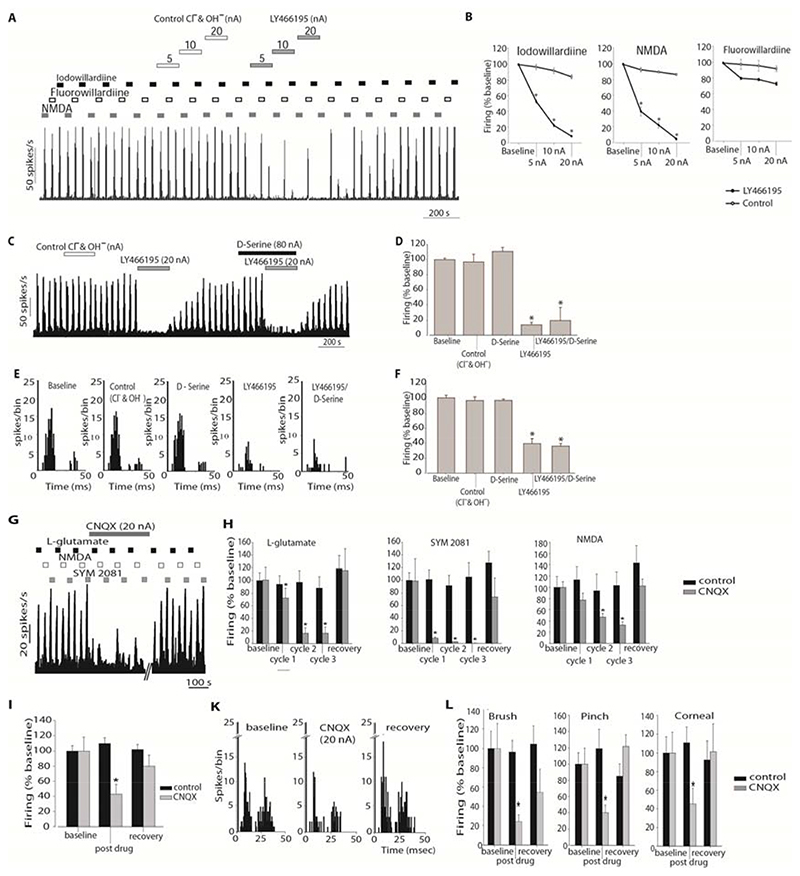

LY466195 potently inhibited responses to iodowillardiine (P < 0.001) and NMDA (P < 0.005) evoked-firing in a dose response manner (Figure 3A, B). Fluorowillardiine-evoked firing was not altered by LY466195 across the cohort (P = 0.09).

Figure 3.

A. Example of the effects of LY466195 on the firing rates to pulsed ejections of Fluorowillardiine, Iodowillardiine and NMDA. Cell firing in response to the ejected agonists returned to baseline levels within 2-5 minutes after LY466195 microiontophoresis ceased. B. Comparison of the effect of LY466195 and control ions (Cl-, OH-) on iodowillardiine, NMDA and fluorowillardiine evoked responses. Cell firing in response to iodowillardiine and NMDA was significantly inhibited by microiontophoretically administered LY466195. C. Example of the response of a trigeminocervical neuron to pulsed NMDA. Ejection of serine, LY466195 and control ions are shown with the solid bars. Ejection of LY466195 demonstrated a potent inhibitory effect on NMDA-evoked firing that was not reversed by pre-treatment with serine. D. Comparison of the NMDA evoked firing during ejection of control ions and LY466195. E. Post-stimulus histograms generated from a representative trigeminocervical neuron following electrical stimulation of the middle meningeal artery. Microiontophoresis of serine or control ions at the same current had no effect on neuronal firing. Co-ejection of serine with LY466195 failed to block the inhibitory actions of LY466195. F. Comparison of the middle meningeal artery stimulation-evoked firing under the influence of LY466195, serine and control ions. G. Example of the effects of CNQX on the firing rates to pulsed ejections of the L-glutamate, Iodowillardiine and SYM 2081. Cell firing in response to the ejected agonists returned to baseline levels within 30 min after CNQX microiontophoresis ceased. B-H. Effects of CNQX on cell firing in response to L-glutamate, SYM 2081 and NMDA, separately for each ejection cycle. CNQX strongly inhibited L-glutamate, SYM 2081 and NMDA-evoked firing. Ejection of control ions had no significant effects on glutamate agonists-evoked firing. I. Comparison of the middle meningeal artery stimulation-evoked firing under the influence of CNQX and control ions. CNQX significantly inhibited neuronal firing in response to trigeminovascular stimulation. K. Post-stimulus histograms generated from a representative trigeminocervical neuron following electrical stimulation of the middle meningeal artery during baseline conditions, microiontophoresis of CNQX and recovery. neuronal firing. L. Effects of microiontophoretically delivered CNQX on the firing rates of second order neurons in response to receptive field characterisation. Microiontophoretic application of CNQX at 20 nA significantly inhibited firing to both innocuous (brush) and nocuous (corneal brush; pinch) stimulation of the ophthalmic dermatome, while a lower ejection current (10 nA) significantly inhibited noxious stimulation of the receptive field. * P < 0.05 compared to control

3.4.2. Effects of microiontophoretic application of LY466195 and serine on NMDA-evoked post-synaptic firing

As LY466195 demonstrated a significant action on NMDA receptors we aimed to investigate whether this effect was due to actions of LY466195 on the glycine/serine binding site of the NMDA receptor. Serine is an endogenous co-agonist of glutamate at the NMDA receptor, increasing the affinity of the receptor for the endogenous agonist glutamate [40]. Ejection of serine alone neither affected neuronal firing in response to NMDA ejection (Figure 3C, D) nor to MMA stimulation (Figure 3E, F) compared to control ions. Co-ejection of serine with LY466195 failed to reverse the inhibitory actions of LY466195 on NMDA evoked post-synaptic firing (Figure 3D, F).

3.5. Effects of microiontophoretic administration of GluK1 receptor antagonist UBP302 on trigeminal neuronal firing

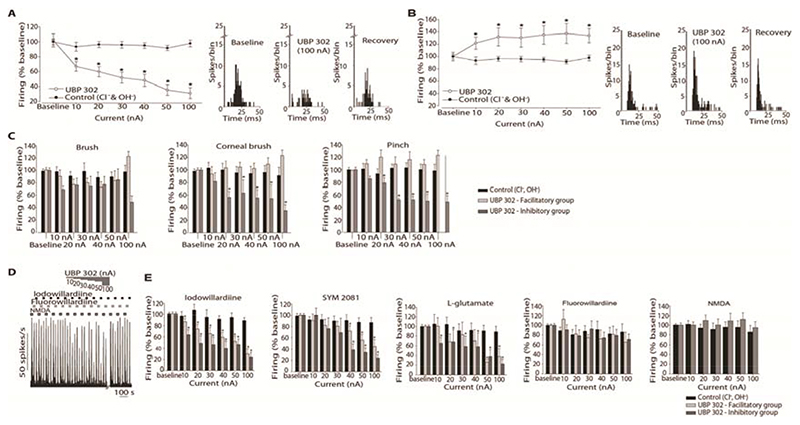

3.5.1. Effects of microiontophoretic application of UBP302 on dural stimulation-evoked activity

UBP302 significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner evoked firing to MMA stimulation in 15 out of 27 neurons (Figure 4A). The maximum inhibition of 70 ± 7% was obtained at the ejection current of 100 nA. Evoked responses to MMA stimulation were significantly facilitated by UBP302 in 12 out of 27 cells (P < 0.001; Figure 4B). In some cases further to the facilitation observed from Aδ-fiber input, a decrease in the threshold to C-fiber activation was also observed during application of UBP302. Inhibitory and facilitatory responses during ejection of UBP302 were frequently seen from neurons recorded in the same animal and the firing returned to baseline within thirty minutes in both groups. Ejection of control ions had no effect (n = 15).

Figure 4.

Effect of microiontophoresis of UBP302 on responses of trigeminocervical neurons to middle meningeal artery stimulation and to receptive field characterisation. Ejection of UBP302 produced two opposing responses. A. In 15 units ejection of UBP302 demonstrated a dose dependent inhibition of the cell firing, maximally at 100 nA. B. In 12 neurons UBP302 significantly potentiated cell firing. Control vehicle had no effect. Post-stimulus histograms from representative cluster of neurons in the inhibitory (A) and facilitatory (B) groups, recorded pre- UBP302 ejection, during ejection of UBP302 at 100 nA, and 30 minutes after the cessation of ejection. C. Effects of microiontophoretically delivered UBP302 and its vehicle control (Cl-, OH-) on the firing rates of second order neurons in response to receptive field characterisation. Cell firing in response to light brush was not altered by microiontophoretically administered UBP302 neither in the inhibitory group nor in the facilitatory group. Cell firing in response to pinch and to corneal stimulation was significantly inhibited by microiontophoretically administered UBP302 in the inhibitory group. Noxious-evoked responses to both pinch and corneal stimulus were not significantly facilitated across the cohort in the facilitatory group. Control ejection had no significant effect. D. Example of the effects of UBP302 on the firing rates to pulsed ejections of fluorowillardiine, iodowillardiine and NMDA. Cell firing in response to the ejected agonists returned to baseline levels within 30 minutes after UBP302 microiontophoresis ceased. E. Comparison of the current-response curves for UBP302 and control (Cl- and OH-) on iodowillardiine, SYM 2081, L-glutamate , fluorowillardiine and NMDA evoked responses. Overall, cell firing in response to iodowillardiine (n = 19), SYM 2081 (n = 18) and L-glutamate (n = 18) was significantly inhibited by microiontophoretically administered UBP302, and there was no significant difference between the inhibitory and the facilitatory groups. Cell firing in response to fluorowillardiine (n = 17) and NMDA (n = 6) was unaffected by microiontophoretically delivered UBP302. Vehicle control had no significance on any agonist-evoked firing. * P < 0.05

Based on the responses of the two groups of cells to UBP302 ejection, these units were further analyzed separately and will be referred to as the inhibitory group and facilitatory group.

3.5.2. Effects of microiontophoretic application of UBP302 on receptive field stimulation-evoked activity

The effects of UBP302 on cell firing to innocuous (brush) and noxious (pinch and corneal brush) mechanical stimulation of the ophthalmic facial cutaneous receptive field were tested in 26 WDR neurons (Figure 4C). Based on the responses of the MMA-evoked activity to UBP302 fourteen of the neurons recorded were clustered in the inhibitory group and twelve were clustered in the facilitatory group; neurons were analyzed separately based on their groups.

Overall, microriontophoretic ejection of UBP302 had no effect on firing rate in response to non-noxious stimulation of the ophthalmic cutaneous area (n = 26; P = 0.10) and there was no significant difference between the inhibitory and facilitatory groups (P ≥ 0.07). UBP302 significantly reduced, in a dose-dependent manner, evoked firing to both pinch and corneal brush stimulation in all neurons clustered in the inhibitory group (pinch: P < 0.001; corneal: P < 0.001), and noxious stimulation-evoked firing returned to baseline within thirty minutes after stopping UBP302 ejection. In the facilitatory group evoked responses to noxious stimulus were facilitated during UBP302 ejection by a maximum of 23 ± 9% but overall there was no significant difference across the cohort (pinch: P = 0.53; corneal: P = 0.38). For both responses to pinch and corneal stimulation, there was a significant difference between the inhibitory and facilitatory groups (P < 0.05).

3.5.3. Effects of microiontophoretic application of UBP302 on post-synaptic firing evoked by glutamate receptor agonists

For all agonists tested there was no difference across the mean firing of the five repeated epochs recorded during baseline (data not shown).

UBP302 reversibly and significantly inhibited trigeminal firing in response to microiontophoresed iodowillardiine (kainate receptor agonist) in all 19 neurons tested, demonstrating a dose-dependent effect (n = 19; Figure 4D, E). SYM 2081 (kainate receptor agonist)-evoked firing was additionally reversibly reduced by UBP302 in a dose-dependent manner (n = 18; Figure 4E), in all units. Based on the responses of the MMA-evoked activity to UBP302, iodowillardiine and SYM 2081-evoked firing was inhibited by UBP302 in both the inhibitory (iodowillardiine: n = 9; SYM 2081: n = 9) and facilitatory (iodowillardiine: n = 10; SYM 2081: n = 9) groups. UBP302 reduced significantly and reversibly the probability of neuronal firing in response to L-glutamate ejection (n = 18; P < 0.05; Figure 4E). UBP302 reduced firing in both inhibitory (n = 9) and facilitatory (n = 9) grouped cells equally.

The effect of UBP302 on fluorowillardiine (AMPA receptor agonist) and on NMDA-evoked firing were tested in 17 and 9 units respectively, and UBP302 produce negligible effects on neuronal firing across the cohort for both agonists (Figure 4E).

3.6. Effects of microiontophoretic administration of the non-selective ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist CNQX on trigeminal neuronal firing

3.6.1. Effects of microiontophoretic application of CNQX on dural stimulation-evoked activity

CNQX at 20 nA inhibited MMA electrical stimulation-evoked cell firing to 43 ± 13% compared to control (P < 0.005), and this effect was ubiquitous among all cells (Figure 3I, K).

3.6.2. Effects of microiontophoretic application of CNQX on receptive field stimulation-evoked activity

CNQX significantly inhibited evoked firing to both non-noxious stimulation of the V1 receptive field to 24 ± 7% (P < 0.05) and to noxious pinch stimulation to 40 ± 9% (t 9 = 5.7; P < 0.005) and corneal mechanical stimulation to 45 ± 17% (n = 4; P = 0.05; Figure 3L). No facilitation was observed on any of the neurons tested with CNQX.

3.6.3. Effects of microiontophoretic application of CNQX on post-synaptic firing evoked by glutamate receptor agonists

The baseline firing responses to glutamate receptor agonist application demonstrated good stability and there was no difference across the mean firing of the five repeated epochs. CNQX inhibited L-glutamate evoked responses to 16 ± 9% (t 7 = 5.50, P < 0.005) and abolished SYM 2081 evoked firing (t 7 = 4.21, P < 0.005). NMDA-evoked firing was significantly reduced to a lesser degree than to L-glutamate and SYM 2081 by a maximum of 67 ± 6% (P < 0.001; Figure 3G,H).

Discussion

The data presented demonstrate a robust modulation of trigeminovascular transmission by kainate receptors at TCC neurons receiving nociceptive trigeminovascular inputs. The use of microiontophoretic application of a kainate specific antagonist in our model, with its technical advantage of precise anatomical localisation [49], enabled the demonstration of bi-directional regulation of trigeminovascular nociceptive transmission in the TCC mediated by kainate receptors, which at the level of individual neurons in vivo is certainly novel. In this context, it is noteworthy that models of neurogenic dural vasodilation [7; 13] failed to demonstrate a peripheral action for kainate receptor antagonists, which makes a central action even more attractive. Moreover, the addition of a cohort of animals treated intravenously emphasizes the potentially translational implications of the data. The current study further offers a plausible locus of action for the clinically active compound LY466195 in migraine [28], via both kainate and NMDA receptor antagonism in the trigeminovascular pain pathway.

The current study used electrical stimulation of dural structures to identify nociceptive neurons. The MMA and its surrounding dura mater are densely innervated by A-and C-fibers [10] and there is clear evidence in humans that electrical stimulation of the meninges reproduces at least pain referred to the head [18; 44]. MMA stimulation has been used extensively as a model for the study of trigeminal nociception and to successfully predict the efficacy of anti-migraine drugs in animal models of head pain [9]. The use of microiontophoresis in our study enabled us to investigate in isolation the induction of post-synaptic action potentials via exogenous applications of glutamate agonists, thus eliminating the role of presynaptic transmitter release. This is a widely used method that allows one to narrow the field of possible induction mechanisms to those of post-synaptic origin [49]. Local ejection of UBP302, a selective GluK1 receptor antagonist, by microiontophoresis blocked in all neurons the post-synaptic activation in response to local application of kainate receptor agonists. This indicates the presence of GluK1 kainate receptors on post-synaptic locations in the TCC, which was further confirmed by means of immunohistochemistry. Interestingly, while post-synaptic firing in response to application of kainate receptor agonists was always inhibited by local application of UBP302, firing evoked by stimulation of the MMA was either inhibited or facilitated by UBP302. This may be due to a different synaptic environment in each neuronal subpopulation where a dominant presence of pre-synaptic kainate receptors may be responsible for the facilitatory effects (Figure 5). In our study we demonstrated the presence of GluK1 receptors in both primary afferents and within neuronal bodies in the TCC. The differential function and pharmacology of pre- and post-synaptic kainate receptors has been demonstrated before in vitro [30–32]. In our study we further suggest such a differential function in vivo.

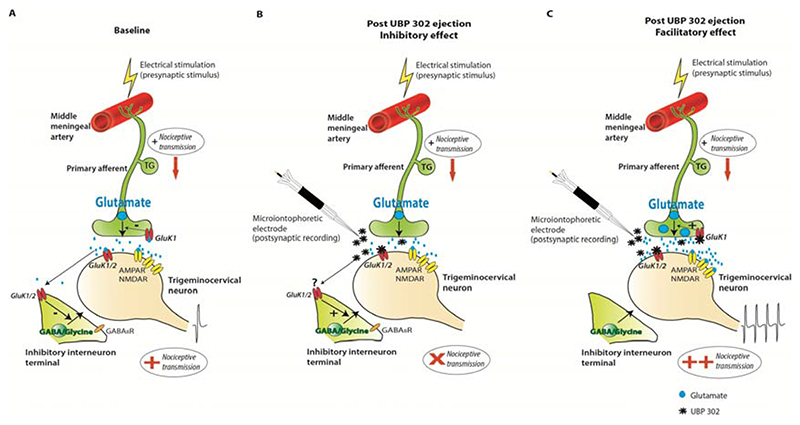

Figure 5. Proposed mechanism of action of microiontophoresed UBP302 on trigeminovascular activation.

Electrical stimulation of the middle meningeal artery will activate fibers arising from the trigeminal ganglion (TG) and increase neuronal firing of second order neurons in the trigeminocervical complex.

A. During baseline recordings, activation of primary afferents innervating the middle meningeal artery causes glutamate release in the trigeminocervical complex. Glutamate activates post-synaptic kainate receptors in addition to AMPA and NMDA receptors activation, promoting trigeminocervical nociceptive transmission. Pre-synaptic kainate receptors on primary trigeminal afferents could be activated by glutamate and control glutamate release, whereas activation of kainate receptors on inhibitory interneurons is also possible, and will modulate inhibitory synaptic transmission. B. Local application of UBP302 by microiontophoresis can selectively block post-synaptic kainate receptors on second order neurons and inhibit nociceptive transmission, most likely in the absence of kainate receptors on the pre-synaptic trigeminal nerve fiber. Blockade of kainate receptors on inhibitory GABAergic terminals could occur due to UBP302 diffusion, and this could additionally account for the resultant analgesic effect. However, as we did not directly study this, such a blockade of kainate heteroreceptors on GABAergic interneurons is shown with a “?”. In such a synaptic environment post-synaptic kainate receptors play an important role in trigeminovascular nociceptive transmission and their selective blockade could prove a beneficial treatment for migraine. C. In a different synaptic environment where both pre- and post-synaptic kainate receptors are present on trigeminal fibers and second-order trigeminocervical neurons respectively, local application of UBP302 by microiontophoresis can selectively block post-synaptic kainate receptors on trigeminocervical neurons. In addition blockade of pre-synaptic kainate receptors on primary afferents might inhibit the negative control feedback of glutamate release by kainate receptors. This results in increased glutamate release upon stimulation of the trigeminal fibers innervating the middle meningeal artery. Released glutamate could then act on a bigger scale on AMPA and NMDA receptors and facilitate nociceptive transmission. In these neurons it is also possible that post-synaptic GluK1 kainate receptors do not mediate sensory transmission.

The inhibition of the MMA stimulation-evoked firing is likely produced by the post- synaptic blockade of GluK1 kainate receptors on these second order neurons, as seen by the attenuation of the kainate receptor agonist’s post-synaptic activation (Figure 5A, B). Stimulation of Aδ- and C-fibers, but not of non-nociceptive primary fibers, has been previously shown to activate post-synaptic kainate receptors on spinal dorsal horn neurons [35], suggesting that kainate receptors are post-synaptically placed, largely at synapses that receive inputs from nociceptive primary afferent fibers. Interestingly, in the current study, in the same neuronal subpopulation noxious over non-noxious receptive field responses were preferentially inhibited. Given the data it seems reasonable to pursue the post-synaptic kainate receptor on second order neurons in the TCC as a target for the development of novel treatments for migraine. In the spinal cord it has also been suggested that kainate heteroreceptors on GABAergic terminals [36] could be activated by glutamate spillover from neighbouring excitatory synapses and occlude GABA/glycine release [27; 30], through indirect activation of GABAB autoreceptors [30], thus promoting a possible pro-nociceptive mechanism. In our study, diffusion of UBP302 to neighbouring GABAergic interneurons may be also a possibility, and therefore blockade of such kainate heteroreceptors would further contribute towards an analgesic effect. However, the direct blockade of kainate receptors that we certainly observed was that of post-synaptic GluK1 kainate receptors on second order neurons.

Interestingly, the GluK1 selective receptor antagonist UBP302, in addition to the inhibition of trigeminovascular activation, also facilitated trigeminovascular transmission in a subset of neurons, despite the selective reduction of post-synaptic firing in responses to kainate receptor agonists. It is thus unlikely that the observed facilitation was due to post-synaptic blockade of kainate receptors or, as discussed above, due to blockade of kainate heteroreceptors on GABAergic terminals, as these would have resulted in inhibition. A non-glutamate receptor action of UBP302 is also rather unlikely, as UBP302 is consistently described as a highly selective and potent GluK1 antagonist. None of the other willardiine derivative antagonists were ever described to have non-glutamate receptor actions [16]. We, and others have shown that GluK1 subunits are expressed in the trigeminal ganglion [47] and on primary afferents in the TCC [24]. It is believed that presynaptic kainate receptors on primary afferents act as autoreceptors and occlude further glutamate release when activated [32]. It is likely that strong activation of presynaptic kainate receptors leads to inhibition of glutamate release [25; 33], possibly by inactivating calcium and/or sodium channels [29]. Thus, the facilitation observed in a subpopulation of trigeminovascular neurons by antagonism of GluK1 receptors could be due to blockade of presynaptic kainate autoreceptors [30-32]resulting in enhanced glutamate release in response to trigeminovascular stimulation. The released glutamate could then act on AMPA and NMDA receptors, resulting in enhancement of sensory transmission (Figure 5A, C). Thus, in a synaptic environment where both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic GluK1 are present on primary trigeminal fibers and second order neurons respectively, a GluK1 antagonist may induce facilitation of trigeminovascular activity, whereas, in a synaptic environment where there is a dominant presence of post-synaptic GluK1 receptors, a GluK1 antagonist is more likely to have anti-nociceptive properties.

Although UBP302, demonstrated a trend to also facilitate corneal brush and pinch responses in the facilitatory group where trigeminovascular stimulation was facilitated, this was not significant. Trigeminovascular activation recorded in this study was mainly induced by Aδ-fibers, whereas activation induced by corneal brush and pinch are more likely induced by stimulation of C-fibers. It is likely that GluK1 are not located on pre-synaptic trigeminal C-fibers, however our immunohistochemistry data suggest that kainate receptors may be found in small size neurons, possibly corresponding to Aδ- and C-fibers. The differential effect may be explained due to the modality of stimulation in each case, where in trigeminovascular activation electrical stimulation was used and data were collected over a total of 25 stimuli, whereas during noxious receptive field activation, mechanical stimulation was used and data were collected over a 2s stimulation of the receptive field. However, it is difficult to safely reach a conclusion for these effects.

In contrast to the dual effects of UBP302, application of CNQX resulted only in inhibition of nociceptive transmission in the TCC, further suggesting that the facilitation seen is a specific kainate receptor mediated effect. Microiontophoretic application of the clinically active compound LY466195 also failed to demonstrate any bi-directional regulation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the TCC. This was probably due to the fact that although LY466195 demonstrated a potent antagonist action on GluK1 receptor-evoked firing in accordance with its pharmacological characterisation [50], to our surprise, a significant action on NMDA receptors was additionally recorded. With most kainate receptor antagonists described to date, it is more common to have some action on AMPA than on NMDA receptors [26]. In vitro data of LY466195 demonstrated some competitive binding affinity on NMDA receptors, with a 55-fold selectivity for GluK1 receptors over NMDA [50]. Other kainate or AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists such as kynurenic acid [21] and CNQX [34], have an antagonist action on the glycine/serine site of the NMDA receptor. Our data suggest that LY466195 has no actions on the glycine/serine binding site of the NMDA receptors, as serine, failed to prevent its inhibitory actions over NMDA-evoked firing. In a randomized double-blind study, LY466195 was effective in relieving acute migraine [28], although patients reported visual side effects, that may be attributed to blockade of both receptors. Although, a global blockade of glutamate receptors may indeed appear to have stronger analgesic effects, the widespread distribution of AMPA and NMDA receptors in the CNS, as well as essence of their physiological activity for normal neuronal function, will very likely induce unacceptable clinical side effects [5]. Kainate receptors on the other hand are not as widely distributed within the CNS; but they are, certainly found in areas of interest in terms of the pain pathways involved in migraine, such as in the trigeminal ganglia, the TCC and the thalamus.

In conclusion, our data provide evidence for the regulation of trigeminovascular transmission by both post-synaptic and pre-synaptic kainate receptors, indicating a modulatory role of kainate receptors in trigeminovascular nociceptive processing, at the level of TCC. Differential activation of kainate receptors has revealed novel roles of this receptor in pro- and anti-nociceptive mechanisms in the TCC and its differential targeting in terms of synaptic localisation might provide new options in migraine therapeutics.

Acknowledgements

The work was funded by the Sandler Foundation.

Funding and Disclosure

The work has been funded by the Migraine Trust, EUROHEADPAIN European Union FP7, the Sandler Family Foundation and the Wellcome Trust (104033).

PJG has consulted for Eli-Lilly on migraine therapeutics.

Eli-Lilly had no involvement of any type in the work or manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AMPA

a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CNQX

6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- iGluR

ionotropic glutamate receptor

- LY466195

3S,4aR,6S,8aR)-6-[[(2S)-2-carboxy-4,4-difluoro-1-pyrrolidinyl]-methyl]de cahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxylic acid

- MMA

middle meningeal artery

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- SYM 2081

(2S,4R)-4-Methylglutamic acid

- TCC

trigeminocervical complex

- UBP302

(S)-1-(2-Amino-2-carboxyethyl)-3-(2-carboxybenzyl)pyrimidine-2,4-dione

- WDR

wide dynamic range

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Abbreviated title: kainate receptors modulate trigeminovascular activation

References

- [1].Afridi S, Giffin NJ, Kaube H, Goadsby PJ. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in migraine with prolonged aura. Neurology. 2013;80:642–647. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182824e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Agrawal SG, Evans RH. The primary afferent depolarizing action of kainate in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1986;87(2):345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Akerman S, Goadsby PJ. Topiramate inhibits cortical spreading depression in rat and cat: impact in migraine aura. Neuroreport. 2005;16(12):1383–1387. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000175250.33159.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Akerman S, Goadsby PJ. Topiramate inhibits trigeminovascular activation: an intravital microscopy study. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146(1):7–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Andreou AP, Goadsby PJ. Therapeutic potential of novel glutamate receptor antagonists in migraine. Expert opinion on investigational drugs. 2009;18(6):789–803. doi: 10.1517/13543780902913792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Andreou AP, Goadsby PJ. Topiramate in the treatment of migraine: a kainate (glutamate) receptor antagonist within the trigeminothalamic pathway. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(13):1343–1358. doi: 10.1177/0333102411418259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Andreou AP, HP R, Goadsby PJ. Activation of iGluR5 kainate receptors inhibits neurogenic dural vasodilatation in an animal model of trigeminovascular activation. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00142.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Andreou AP, Shields KG, Goadsby PJ. GABA and valproate modulate trigeminovascular nociceptive transmission in the thalamus. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010;37:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Andreou AP, Summ O, Charbit AR, Romero Reyes M, Goadsby PJ. Animal models of headache-From bedside to bench and back to beside. Expert Review in Neurotherapeutics. 2010;10:389–411. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Andres KH, von During M, Muszynski K, Schmidt RF. Nerve fibres and their terminals of the dura mater encephali of the rat. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1987;175(3):289–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00309843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bortolotto ZA, Clarke VR, Delany CM, Parry MC, Smolders I, Vignes M, Ho KH, Miu P, Brinton BT, Fantaske R, Ogden A, et al. Kainate receptors are involved in synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1999;402(6759):297–301. doi: 10.1038/46290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bussone G, Diener H-C, Pfeil J, Schwalen S. Topiramate 100 mg/day in migraine prevention: a pooled analysis of double-blinded randomised controlled trials. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2005;59:961–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chan KY, Gupta S, van Veghel R, de Vries R, Danser AHJ, Maassen Van Den Brink A. Distinct effects of several glutamate receptor antagonists on rat dural artery diameter in a rat intravital microscopy model. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:101. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chittajallu R, Braithwaite SP, Clarke VR, Henley JM. Kainate receptors: subunits, synaptic localization and function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20(1):26–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Collingridge GL, Olsen RW, Peters J, Spedding M. A nomenclature for ligand gated ion channels. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:2–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dolman NP, More JC, Alt A, Knauss JL, Troop HM, Bleakman D, Collingridge GL, Jane DE. Structure-activity relationship studies on N3-substituted willardiine derivatives acting as AMPA or kainate receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2006;49(8):2579–2592. doi: 10.1021/jm051086f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dudek FE, Bramley JR. GluR5 Kainate Receptors and Topiramate: A New Site of Action for Antiepileptic Drugs? Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4(1):17. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7597.2004.04107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Feindel W, Penfield W, McNaughton F. The tentorial nerves and localization of intracranial pain in man. Neurology. 1960;10:555–563. doi: 10.1212/wnl.10.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ferrari MD, Odink J, Box KD, Malessy MJA, Bruyn GW. Neuroexcitatory plasma amino acids are elevated in migraine. Neurology. 1990;40:1582–1586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.10.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Filla SA, Winter MA, Johnson KW, Bleakman D, Bell MG, Bleisch TJ, Castano AM, Clemens-Smith A, del Prado M, Dieckman DK, Dominguez E, et al. Ethyl (3S,4aR,6S,8aR)-6-(4-ethoxycar-bonylimidazol-1-ylmethyl)decahydroiso-quinoline-3-carboxylic ester: a prodrug of a GluR5 kainate receptor antagonist active in two animal models of acute migraine. J Med Chem. 2002;45(20):4383–4386. doi: 10.1021/jm025548q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Foster AC, Kemp JA, Leeson PD, Grimwood S, Donald AE, Marshall GR, Priestley T, Smith JD, Carling RW. Kynurenic acid analogues with improved affinity and selectivity for the glycine site on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor from rat brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41(5):914–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Goadsby PJ, Charbit AR, Andreou AP, Akerman S, Holland PR. Neurobiology of migraine. Neuroscience. 2009;161(2):327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Goadsby PJ, Classey JD. Glutamatergic transmission in the trigeminal nucleus assessed with local blood flow. Brain Res. 2000;875(1-2):119–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hegarty DM, Mitchell JL, Swanson KC, Aicher SA. Kainate receptors are primarily postsynaptic to SP-containing axon terminals in the trigeminal dorsal horn. Brain Res. 2007;1184:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Huettner JE. Kainate receptors and synaptic transmission. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(5):387–407. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jane DE, Lodge D, Collingridge GL. Kainate receptors: Pharmacology, function and therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(1):90–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jiang L, Xu J, Nedergaard M, Kang J. A kainate receptor increases the efficacy of GABAergic synapses. Neuron. 2001;30(2):503–513. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Johnson KW, Nisenbaum ES, Johnson MP, Dieckman DK, Clemens-Smith A, Siuda ER, Dell CP, Dehlinger V, Hudziak KJ, Filla SA, Ornstein PL, et al. Innovative drug development for headache disorders: glutamate. In: Olesen J, Ramadan N, et al., editors. Innovative Drug Development for Headache Disorders. Vol. 16. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kamiya H, Ozawa S. Kainate receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition at the mouse hippocampal mossy fibre synapse. J Physiol. 2000;523(Pt 3):653–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kerchner GA, Wang GD, Qiu CS, Huettner JE, Zhuo M. Direct presynaptic regulation of GABA/glycine release by kainate receptors in the dorsal horn: an ionotropic mechanism. Neuron. 2001;32(3):477–488. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kerchner GA, Wilding TJ, Huettner JE, Zhuo M. Kainate receptor subunits underlying presynaptic regulation of transmitter release in the dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 2002;22(18):8010–8017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08010.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kerchner GA, Wilding TJ, Li P, Zhuo M, Huettner JE. Presynaptic kainate receptors regulate spinal sensory transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21(1):59–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00059.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lerma J. Roles and rules of kainate receptors in synaptic transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(6):481–495. doi: 10.1038/nrn1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lester RA, Quarum ML, Parker JD, Weber E, Jahr CE. Interaction of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione with the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-associated glycine binding site. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;35(5):565–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li P, Wilding TJ, Kim SJ, Calejesan AA, Huettner JE, Zhuo M. Kainate-receptor-mediated sensory synaptic transmission in mammalian spinal cord. Nature. 1999;397(6715):161–164. doi: 10.1038/16469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lu CR, Willcockson HH, Phend KD, Lucifora S, Darstein M, Valtschanoff JG, Rustioni A. Ionotropic glutamate receptors are expressed in GABAergic terminals in the rat superficial dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol. 2005;486(2):169–178. doi: 10.1002/cne.20525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lucifora S, Willcockson HH, Lu CR, Darstein M, Phend KD, Valtschanoff JG, Rustioni A. Presynaptic low-and high-affinity kainate receptors in nociceptive spinal afferents. Pain. 2006;120(1-2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mathew R, Andreou AP, Chami L, Bergerot A, van den Maagdenberg AM, Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ. Immunohistochemical characterization of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the trigeminal system of the familial hemiplegic migraine 1 knock-in mouse. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(13):1368–1380. doi: 10.1177/0333102411418847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mitsikostas DD, Sanchez del Rio M, Waeber C, Huang Z, Cutrer FM, Moskowitz MA. Non-NMDA glutamate receptors modulate capsaicin induced c-fos expression within trigeminal nucleus caudalis. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127(3):623–630. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mothet JP, Parent AT, Wolosker H, Brady RO, Jr, Linden DJ, Ferris CD, Rogawski MA, Snyder SH. D-serine is an endogenous ligand for the glycine site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(9):4926–4931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Wittchen HU, Jonsson B. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Penfield W, McNaughton FL. dural headache and innervation of the dura matter. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1940(44):43–75. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ramadan NM, Sang C, Chappell AS, Vandenhende F, Johnson K, Phebus L, Bleakman D, Ornstein P, Arnold B, Freitag FG, Smith TR, et al. IV LY293558, an AMPA/Kainate receptor antagonist, is effective in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2001;21:267–268. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Role of kainate receptors in nociception. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;40(1-3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sahara Y, Noro N, Iida Y, Soma K, Nakamura Y. Glutamate receptor subunits GluR5 and KA-2 are coexpressed in rat trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17(17):6611–6620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sang CN, Ramadan NM, Wallihan RG, Chappell AS, Freitag FG, Smith TR, Silberstein SD, Johnson KW, Phebus LA, Bleakman D, Ornstein PL, et al. LY293558, a novel AMPA/GluR5 antagonist, is efficacious and well-tolerated in acute migraine. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(7):596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Stone TW. Microiontophoresis and Pressure Injection. John Wiley and Sons; Chichester: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Weiss B, Alt A, Ogden AM, Gates M, Dieckman DK, Clemens-Smith A, Ho KH, Jarvie K, Rizkalla G, Wright RA, Calligaro DO, et al. Pharmacological characterization of the competitive GLUK5 receptor antagonist decahydroisoquinoline LY466195 in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318(2):772–781. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]