Abstract

Background

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the fourth most common cause for need for renal replacement therapy (RRT). Still, there are few epidemiological data on the prevalence of, and survival on RRT for ADPKD.

Methods

This study used data from the ERA-EDTA Registry on RRT prevalence and survival on RRT in 12 European countries with 208 million inhabitants. We studied four 5-year periods (1991-2010). Survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method and by Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

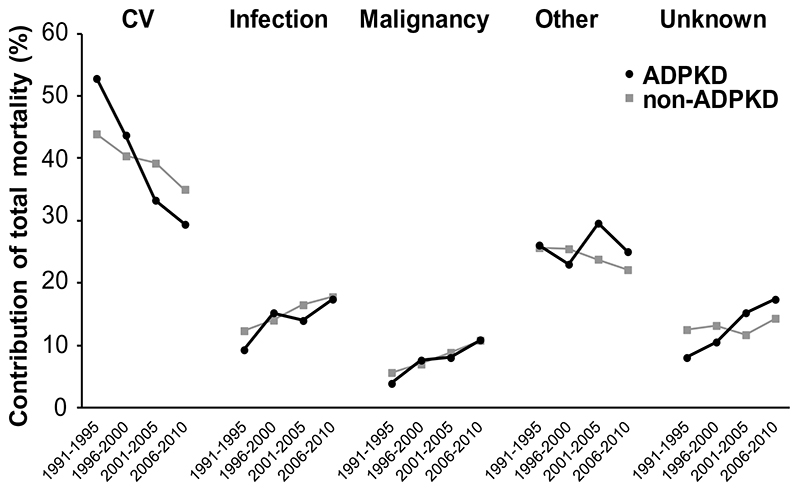

From the first to the last study period, the prevalence of RRT for ADPKD increased from 56.8 to 91.1 per million population (pmp). The relative proportion of ADPKD patients of the total number of prevalent RRT patients remained fairly stable at 9.8%. Two-year survival of ADPKD patients on RRT (adjusted for age, sex and country) increased significantly from 89.0 to 92.8%, and was higher than for non-ADPKD subjects. Improved survival was noted for all RRT modalities: hemodialysis (adjusted Hazard Ratio for mortality last versus first time period 0.75 (95% CI 0.61-0.91), peritoneal dialysis 0.55 (0.38-0.80) and transplantation 0.52 (0.32-0.74)). Cardiovascular mortality as proportion of total mortality on RRT decreased more in ADPKD patients (from 53% to 29%), than in non-ADPKD patients (from 44% to 35%). Of note, the incidence rate of RRT for ADPKD remained relatively stable at 7.6 vs. 8.3 pmp from the first to the last study period.

Conclusions

In ADPKD patients on RRT survival has improved markedly, especially due to a decrease in cardiovascular mortality. This has led to a considerable increase in the number of ADPKD patients being treated with RRT.

Keywords: ADPKD, epidemiology, renal replacement therapy, survival, prevalence

Introduction

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) is the most common hereditary kidney disease. It affects approximately 1 in every 1000 subjects of the general population (1). The disease is characterised by progressive cysts formation, especially in the kidneys, leading to massive kidney enlargement, pain and hematuria. Most ADPKD subjects show progressive renal function decline and approximately 70% develop end-stage renal disease between their 4th to 7th decade of life (2–4). ADPKD occurs worldwide and in all races (5), and it is generally assumed that this patient group accounts for around 10% of all subjects who are dependent on renal replacement therapy (RRT). However, differences in prevalence between regions have been suggested (6).

The choice of renal replacement modality is dependent on several factors, including patient choice, physicians’ advice and resource availability. For the last 20 years, three RRT modalities have been available; hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and renal transplantation. In ADPKD peritoneal dialysis may be complicated by an increased prevalence of abdominal wall hernias and lower dialysis efficiency because of reduced abdominal space secondary to the enlarged kidneys and liver (7). This raised concern whether peritoneal dialysis is a good treatment modality in ADPKD patients. Based on clinical experience and evidence from small-scale observational studies (8, 9), however, new opinions have been formed and policy changed. It has recently even been suggested that peritoneal dialysis may be associated with a better prognosis in ADPKD than in non-ADPKD patients (10).

The survival of patients with treated end-stage renal disease for ADPKD has been described in the 90’s. These studies showed that ADPKD patients had better survival on RRT than non-ADPKD patients (10–12). More recent studies suggested a further improvement in survival, but these studies were performed in relatively small patient populations (13–15). As a result of this increased survival, the number of ADPKD patients on RRT and the associated costs for medical care may be expected to have increased. However, there is no recent comprehensive overview of trends in time of prevalence, survival and costs associated with RRT for ADPKD.

The European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) Registry and the EuroCYST consortium have initiated a project to increase knowledge of the epidemiology of RRT for ADPKD in Europe. As part of this project, we investigated for ADPKD the prevalence of RRT and survival after start of RRT (overall and per specific treatment modality) across Europe.

Methods

Data collection

The study population consisted of RRT patients included in the ERA-EDTA Registry. Currently, 24 national and regional registries from 12 countries within Europe are participating, covering a population of 208 million people. Individual patient data, including date of birth, sex, primary renal disease, treatment modality history (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and transplantation), and date and cause of death were derived from the national registries of Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Romania, Sweden, the Netherlands and England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland (the United Kingdom), and from the regional registries of Dutch and French-speaking Belgium, Calabria (Italy), Andalusia, Aragon, Asturias, Basque country, Cantabria, Castile and León, Castile-La Mancha, Catalonia, Extremadura, Galicia, and Valencian region (Spain). Of these registries information on all RRT patients were used, except for Belgium, Spain (Cantabria, Castile and Leon and Castile-La Mancha) and the United Kingdom (except Scotland) that delivered information on patients >20 years of age. These registries were also included, because ADPKD patients only rarely reach end-stage renal disease before this age. This age limitation was therefore not expected to influence results on prevalence of RRT for ADPKD. Registries from the following countries/regions provided complete information for all years within the study period: Andalusia (Spain), Austria, Basque country (Spain), Catalonia (Spain), Denmark, Finland, French-speaking Belgium, Greece, Sweden, Scotland, the Netherlands, and Valencia (Spain). For Belgium, Spain and the United Kingdom (except Scotland that provided complete data for the whole period), participation rates increased over time. Information on participation rates is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Definition

Primary renal disease for which RRT was started was assessed using the ERA-EDTA coding system (16). Two ERA-EDTA primary renal disease codes can be used for the diagnosis of ADPKD: 40 (unspecified polycystic kidney disease) and 41 (polycystic kidney disease adult type). Among countries, a substantial variation (0.1% to 3.4%) in the mean prevalence of code 40 was observed (see Supplementary Table 2). We combined codes 40 and 41 for the definition of ADPKD, because the prevalence of non-ADPKD polycystic kidney disease is expected from clinical experience to be very low, and unlikely to account for figures such as 3.4%.

Data analysis

The prevalence of RRT and survival after start of RRT (overall and per specific treatment modality) were studied for ADPKD patients and compared with data for non-ADPKD patients (all other RRT patients).

Prevalence was studied in 4 consecutive 5-year periods (1991-1995, 1996-2000, 2001-2005, and 2006-2010). For each period, we calculated for participating registries the average prevalence of RRT for ADPKD as the sum of the prevalence of ADPKD patients alive and on RRT on December 31st of 5 subsequent years divided by the sum of the total general population covered by that registry in the same 5 years. Treatment modality was defined as the treatment patients were attending at December 31st of each year. The age and sex distribution of the 2005 EU27 population as provided by Eurostat (17) was used to adjust for age and sex, to allow evaluation of trends in time and differences among countries. To investigate the association between prevalence of RRT for ADPKD versus for non-ADPKD, we used weighted least squares regression analysis to take country specific population sizes into account.

Survival analyses for dialysis were performed on incident patients, i.e. patients who started dialysis. Treatment modality at day 91 after start of RRT was used to categorize subjects into hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. For renal transplant recipients, survival analyses were performed using data after the first transplantation, i.e. such patients could have been on dialysis before transplantation. We used the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards regression to calculate crude and adjusted survival. Data on two-year survival was used, because two-year survival was known for all four study periods under investigation. For the survival analyses, death was the event studied and reasons for censoring were loss to follow-up, renal transplantation (in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients) or the end of the follow-up period. To allow evaluations evaluation of trends in time, and comparisons between ADPKD and non-ADPKD patients, survival analyses were adjusted for age, sex, primary renal disease and country. In addition, survival analyses were performed for specifically patients with primary glomerulonephritis (ERA-EDTA primary renal disease codes 10-19) as extra control group. Survival analyses were only performed using data of registries that had information over the entire study period (i.e. from 1991 through 2010). Patient survival was calculated for the overall RRT population, but also for a specific age group (age 60-65 years at start RRT). For analyses of causes of death only data from registries reporting less than 25% missing or unknown causes of death were included. These registries are: Austria, Belgium (French-speaking), Denmark, Finland, Greece, Spain (Andalusia, Basque country, Catalonia, Valencian region), Sweden and The Netherlands. Cause of death was coded using the ERA-EDTA coding system for causes of death (16). For analyses of causes of death per RRT modality, modality was determined at two-years of follow-up, or at 60 days before the date of death in case patients died before two-years of follow-up. Regression and survival analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.2.

To determine the economic burden associated with end-stage renal disease for ADPKD the costs involved with RRT were estimated. Country specific information obtained from literature was used. For costs involved with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis therapy data were obtained from: Austria (18), Belgium (19), Denmark (20), Finland (21), France (22), Greece (23), Italy (24), Romania (25), Spain (26), Sweden (27), the Netherlands (28), and the United Kingdom (29). For costs involved with transplantation (first and subsequent years) data were obtained from: Austria (18), Finland (21), France (22), Greece (23), the Netherlands (28) and Spain (26). Costs were adjusted for currency, and for inflation by harmonised indices of consumer prices as provided by Eurostat (17). Per RRT treatment modality the average of the costs obtained from these countries was calculated, together with a 95% confidence interval. These numbers were multiplied by the total number of prevalent ADPKD patients per RRT treatment modality in 2010 and summed.

Results

Prevalence of RRT

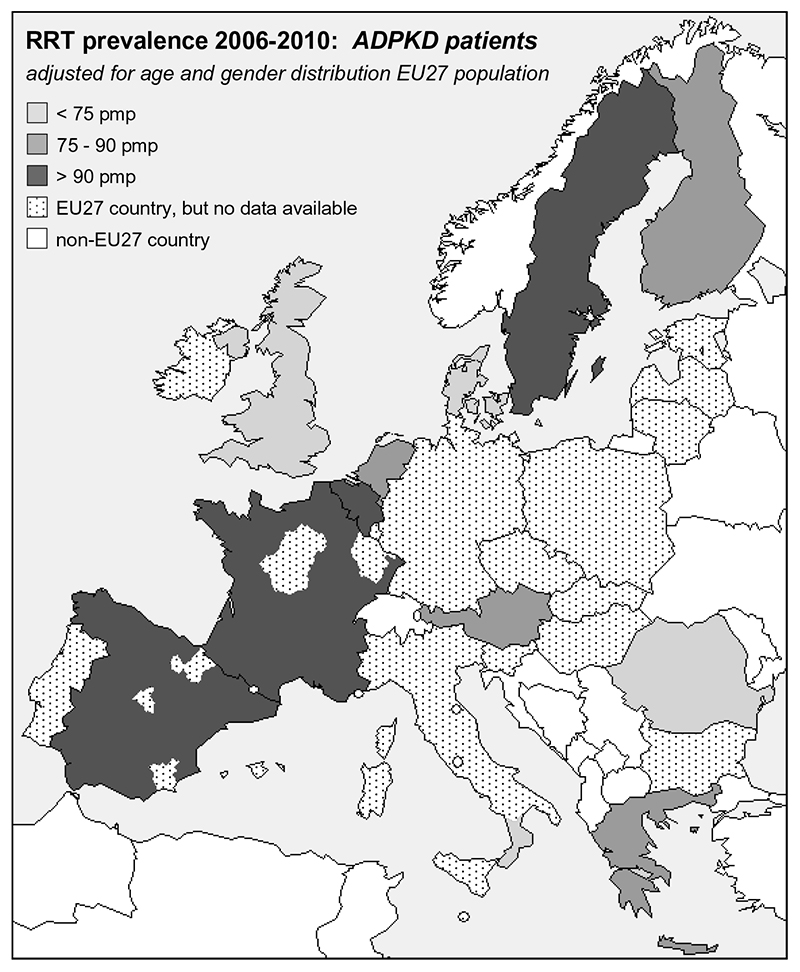

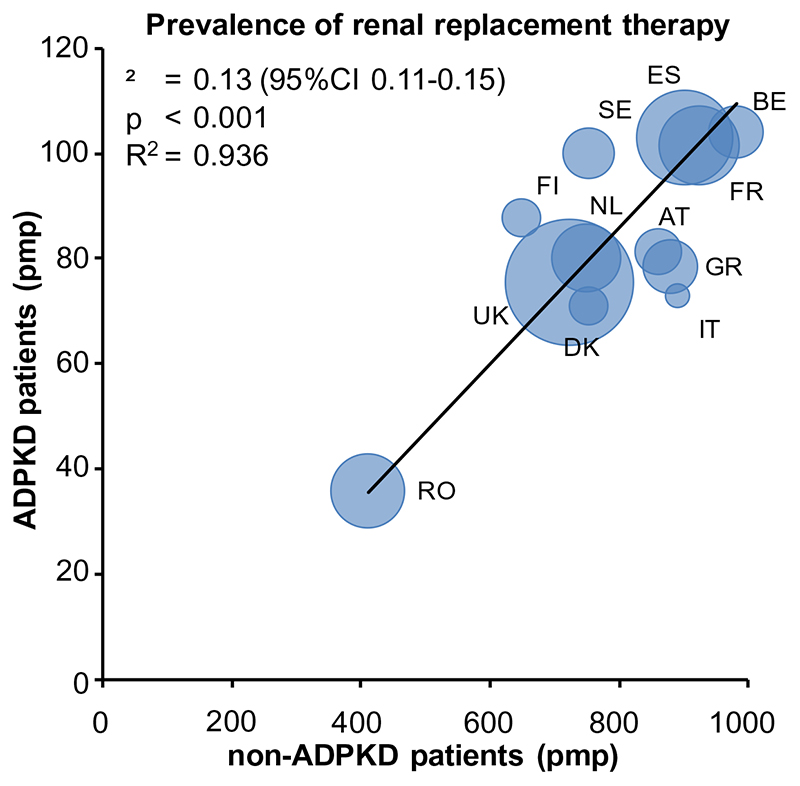

Between 1991 and 2010 a total of 437,496 prevalent patients from 12 countries received RRT; 35,164 patients with ADPKD and 402,332 non-ADPKD patients. Of these patients, 265,866 were male (61%) (18,588 ADPKD patients and 247,278 non-ADPKD patients). Table 1 shows the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of ADPKD subjects on RRT for the participating countries during 4 consecutive periods of 5-years. Having observed differences in crude prevalence among European countries, we standardized for age and sex of the 2005 EU27 population, but differences persisted (Table 1). Prevalence in Denmark, Italy (Calabria), Romania and the United Kingdom was below the mean (91.1 per million population [pmp]), whereas in Belgium, France, Spain and Sweden, the prevalence was higher. Figure 1 visualises these differences geographically. Figure 2 shows per country the prevalence of RRT for ADPKD versus the prevalence of RRT for non-ADPKD in the same time period (2006 through 2010), standardized for age and sex to the 2005 EU27 population. This figure shows a clear positive correlation (R2=0.936, p<0.001), indicating that in countries with a high overall number of non-ADPKD patients on RRT, there is also a high number of ADPKD patients on RRT.

Table 1.

Prevalence of ADPKD patients receiving renal replacement therapy overall (upper panel), and subdivided in dialysis (middle panel) or living with a renal transplant (lower panel). All data are standardised to the age and sex distribution of the 2005 EU27 population and expressed per million population (pmp).

| 1991-1995 | 1996-2000 | 2001-2005 | 2006-2010 | Change# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmp | pmp | pmp | pmp | % | |

| All RRT | |||||

| Austria- | 47.4 | 60.4 | 73.0 | 81.4 | +71.7 |

| Belgium* | 51.4 | 72.5 | 88.9 | 104.1 | +102.5 |

| Denmark- | 47.4 | 55.4 | 64.1 | 71.1 | +50.0 |

| Finland- | 44.0 | 62.9 | 79.1 | 87.9 | +99.8 |

| France | 101.5 | NA | |||

| Greece- | 38.6 | 58.1 | 72.0 | 78.5 | +103.4 |

| Italy, Calabria | 64.7 | 69.5 | 72.9 | +12.7 | |

| Romania | 35.9 | NA | |||

| Spain* | 80.8 | 91.5 | 93.0 | 103.0 | +27.5 |

| Sweden- | 64.7 | 77.1 | 90.4 | 100.0 | +54.6 |

| The Netherlands- | 56.3 | 65.0 | 72.2 | 80.2 | +42.5 |

| United Kingdom* | 46.4 | 55.4 | 61.9 | 75.6 | +62.9 |

| All countries + | 56.8 | 70.3 | 82.1 | 91.1 | +60.4 |

| Dialysis | |||||

| Austria- | 22.4 | 28.3 | 30.9 | 32.3 | +44.2 |

| Belgium* | 33.3 | 33.1 | 34.6 | 37.6 | +12.9 |

| Denmark- | 22.8 | 28.9 | 33.8 | 33.7 | +47.8 |

| Finland- | 17.9 | 21.1 | 23.4 | 22.5 | +25.7 |

| France | 39.5 | NA | |||

| Greece- | 32.0 | 48.3 | 56.0 | 56.0 | +75.0 |

| Italy, Calabria | 57.1 | 57.7 | 53.4 | -6.5 | |

| Romania | 34.4 | NA | |||

| Spain* | 54.2 | 47.4 | 39.9 | 39.4 | -27.3 |

| Sweden- | 22.7 | 26.4 | 31.1 | 31.6 | +39.2 |

| The Netherlands- | 28.8 | 29.3 | 30.3 | 26.8 | -6.9 |

| United Kingdom* | 20.7 | 23.4 | 26.2 | 29.9 | +44.4 |

| All countries+ | 32.1 | 35.8 | 37.8 | 37.3 | +16.2 |

| Transplantation | |||||

| Austria- | 25.0 | 32.1 | 42.1 | 49.1 | +96.4 |

| Belgium* | 18.1 | 39.4 | 54.3 | 66.3 | +266.3 |

| Denmark- | 24.6 | 26.4 | 30.1 | 37.0 | +50.4 |

| Finland- | 26.1 | 41.8 | 55.7 | 65.5 | +151.0 |

| France | 61.6 | NA | |||

| Greece- | 6.6 | 9.8 | 15.9 | 22.4 | +239.4 |

| Italy, Calabria | 7.7 | 11.8 | 19.5 | +153.2 | |

| Romania | 1.4 | NA | |||

| Spain* | 26.2 | 43.5 | 52.8 | 63.5 | +142.4 |

| Sweden- | 42.0 | 50.7 | 59.3 | 68.4 | +62.9 |

| The Netherlands- | 27.5 | 35.8 | 41.8 | 53.4 | +94.2 |

| United Kingdom* | 25.7 | 29.9 | 34.3 | 45.3 | +76.3 |

| All countries+ | 24.6 | 34.4 | 44.2 | 53.8 | +118.7 |

NA, not applicable

coverage of the general population by the renal registry increasing over time, see for details Supplementary Table 1.

country with complete coverage during all 4 periods

average of countries with complete coverage during all 4 periods.

Change between 1991-1995 and 2006-2010.

Change between 1996-2000 and 2006-2010

Figure 1.

Prevalence of renal replacement therapy (RRT) for patients with ADPKD. Data are the average of the period 2006 through 2010, expressed per million population (pmp), and adjusted for age and sex distribution of the 2005 EU27 population.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of renal replacement therapy for patients with ADPKD versus non-ADPKD kidney diseases. Data are the average of the period 2006 through 2010, expressed per million population, and adjusted for age and sex to the distribution of the 2005 EU27 population. The size of marker denotes the size of the general population under study. Abbreviations: AT, Austria; BE, Belgium; DK, Denmark; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; FR, France; GR, Greece; IT, Italy, Calabria; NL, The Netherlands; RO, Romania; SE, Sweden; UK, United Kingdom.

Trends in prevalence of overall RRT

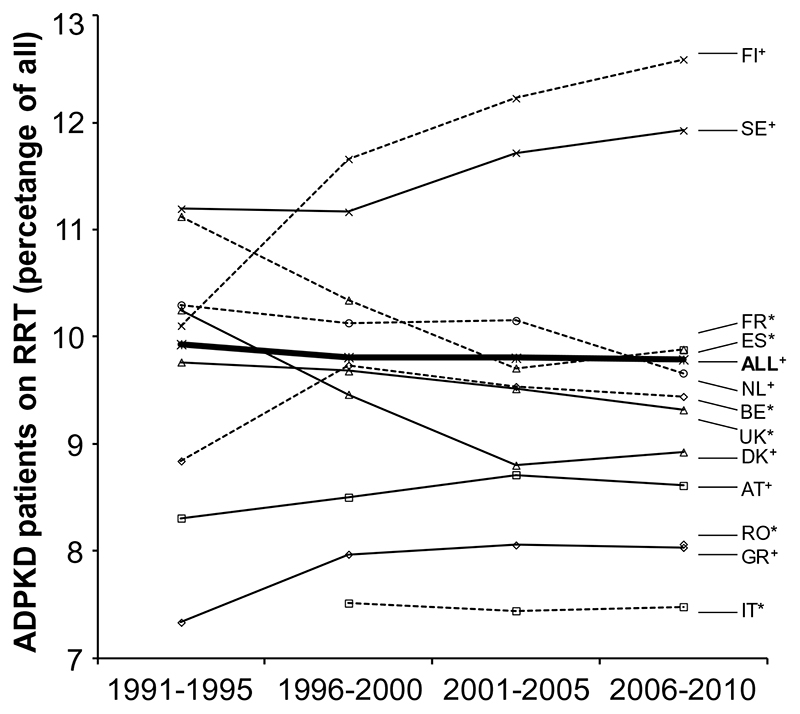

The average prevalence of ADPKD patients receiving RRT increased by 60.4% from 56.8 pmp in 1991-1995 to 91.1 pmp in 2005-2010 (Table 1). While the prevalence of RRT for ADPKD has increased markedly in Belgium and Greece, there has been only a modest increase in other countries, such as the Netherlands and Spain. Figure 3 shows the percentage of prevalent RRT patients with ADPKD for each country and the average for the participating registries with complete follow-up. The average percentage has remained fairly stable over time (9.9% in 1991-1995 versus 9.8% in 2006-2010), with some exceptions at the country level.

Figure 3.

Trends in prevalence of ADPKD patients on renal replacement therapy as percentage of the total population on renal replacement therapy. Abbreviations: AT, Austria; BE, Belgium; DK, Denmark; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; FR, France; GR, Greece; IT, Italy, Calabria; NL, The Netherlands; RO, Romania; SE, Sweden; UK, United Kingdom. * ; Coverage increasing over time, see for details Supplementary Table 1.+ ; All countries with complete follow-up coverage.

Trends in prevalence of specific RRT modalities

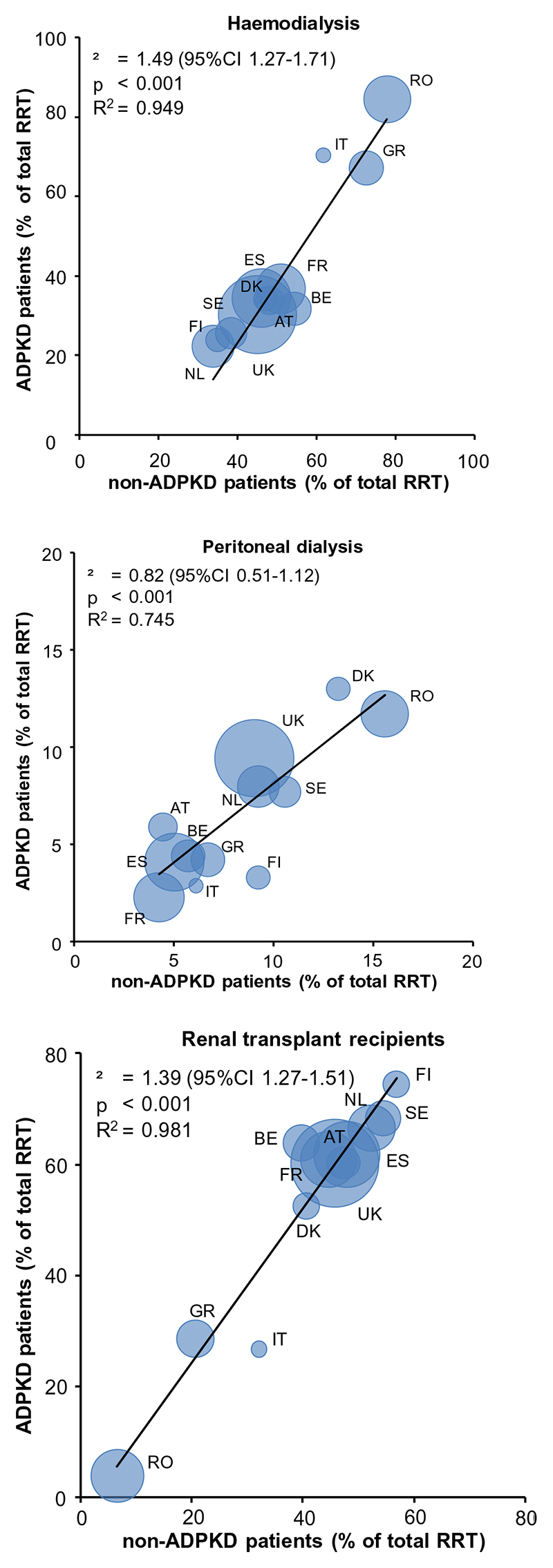

Over the past 20 years, the prevalence of ADPKD patients treated with the various RRT modalities changed. The prevalence of hemodialysis increased from 25.2 to 32.0 pmp, that of peritoneal dialysis from 3.8 to 5.3 pmp and that of renal transplant recipients from 22.3 to 53.8 pmp (1991-1996 versus 2006-2010, respectively). In ADPKD patients the relative contribution to overall RRT decreased for hemodialysis from 49.1% to 35.1%, whereas that of peritoneal dialysis decreased from 7.4% to 5.8%, and that of kidney transplantation increased from 43.5% to 59.1%. Of note, in non-ADPKD patients the relative contribution to overall RRT of hemodialysis has remained stable at 48.0%, whereas peritoneal dialysis decreased from 9.7% to 7.1% and kidney transplantation increased only slightly from 41.2% to 44.1%. Figure 4 shows the prevalence of hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and renal transplantation as percentage of overall RRT in ADPKD versus non-ADPKD patients in the period 2006-2010. It indicates that peritoneal dialysis is as frequently applied as treatment modality in ADPKD as in non-ADPKD patients, whereas ADPKD patients are more likely to be renal transplant recipients (especially of a deceased donor rather than a living donor, Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Patients on hemodialysis (upper panel), peritoneal dialysis (middle panel) and living with a renal transplant (lower panel) as percentage of the total population on renal replacement therapy with ADPKD versus non-ADPKD. Data are the average of the period 2006 through 2010, and adjusted for age and sex to the distribution of the EU27 population in 2005. The size of marker denotes the size of the general population under study. Abbreviations AT, Austria; BE, Belgium; DK, Denmark; ES, Spain; FI, Finland; FR, France; GR, Greece; IT, Italy, Calabria; NL, The Netherlands; RO, Romania; SE, Sweden; UK, United Kingdom.

Trends in survival

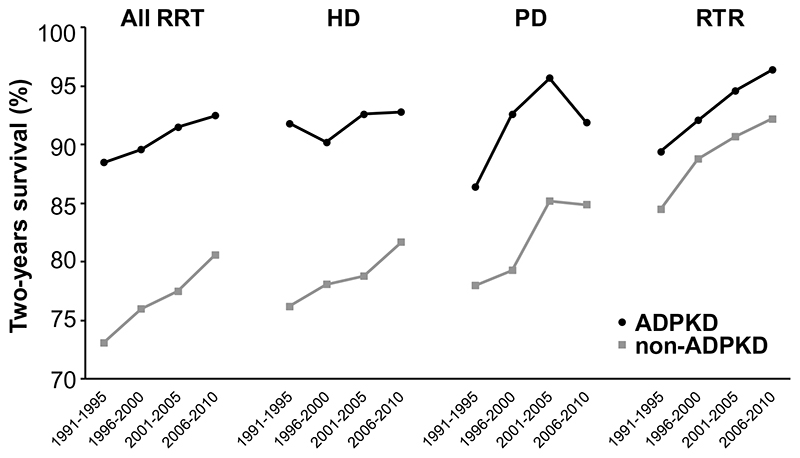

The incidence rate of RRT for ADPKD remained relatively stable at 7.6 vs. 8.3 pmp. Crude two-year survival rate of incident ADPKD patients starting RRT increased from 88.3% in 1991-1995 to 90.8% in 2006-2010. When using the first time period as reference, this corresponds with a Hazard Ratio (HR) for total mortality in the later study period of 0.77 (95% CI 0.66-0.90) (Table 2). When adjusted for age, sex and country, the HR for total mortality was even lower at 0.64 (95% CI 0.55-0.75), indicating that two-year mortality has decreased by 36% in the most recent compared to the first time period (Table 2). When the three different RRT modalities are studied separately, it shows that mortality decreased especially in ADPKD patients starting peritoneal dialysis or receiving a renal transplant (adjusted mortality decreased by 45% and 48%, respectively), whereas in ADPKD patients starting hemodialysis adjusted mortality decreased by only 25% (Table 2). The adjusted survival on RRT is higher in female than in male ADPKD patients (Supplementary Table 3), and in ADPKD patients higher than in non-ADPKD patients (overall, as well as when only patients with primary glomerulonephritis were studied as control group, Supplementary Table 4).The average age at which RRT is started may differ between ADPKD and non-ADPKD patients. Therefore we calculated also survival rates for a specific age group (60-65 years) to allow a fair comparison between ADPKD and non-ADPKD. Figure 5 shows that also in this age group ADPKD patients starting RRT have a higher survival compared to non-ADPKD patients.

Table 2.

Two-year patient survival rate and Hazard Ratio for mortality in ADPKD patients starting renal replacement therapy (RRT), dialysis or receiving a first kidney transplant.

| Two-year survival | Hazard Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All RRT | N | Crude | Adjusted* | Crude | Adjusted** |

| 1991-1995 | 2756 | 88.3 (87.1-89.3) | 89.0 (87.8-90.2) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 1996-2000 | 3279 | 88.9 (87.9-89.8) | 90.3 (89.3-91.3) | 0.94 (0.81-1.10) | 0.88 (0.75-1.02) |

| 2001-2005 | 3547 | 89.4 (88.5-90.3) | 91.6 (90.7-92.5) | 0.90 (0.77-1.04) | 0.75 (0.65-0.88) |

| 2006-2010 | 3708 | 90.8 (89.9-91.7) | 92.8 (92.0-93.6) | 0.77 (0.66-0.90) | 0.64 (0.55-0.75) |

| Hemodialysis | |||||

| 1991-1995 | 1984 | 89.0 (87.6-90.3) | 90.4 (89.0-91.7) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 1996-2000 | 2488 | 88.1 (86.9-89.3) | 90.2 (89.0-91.4) | 1.10 (0.91-1.33) | 1.03 (0.85-1.25) |

| 2001-2005 | 2573 | 88.5 (87.3-89.6) | 91.5 (90.4-92.6) | 1.07 (0.88-1.29) | 0.89 (0.73-1.07) |

| 2006-2010 | 2550 | 90.2 (89.0-91.3) | 92.8 (91.8-93.9) | 0.90 (0.74-1.10) | 0.75 (0.61-0.91) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | |||||

| 1991-1995 | 606 | 86.2 (83.2-88.6) | 88.0 (84.6-91.5) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 1996-2000 | 622 | 91.9 (89.4-93.8) | 92.9 (90.5-95.3) | 0.57 (0.39-0.84) | 0.58 (0.39-0.86) |

| 2001-2005 | 748 | 93.8 (91.7-95.3) | 94.6 (92.7-96.5) | 0.42 (0.28-0.62) | 0.42 (0.28-0.63) |

| 2006-2010 | 789 | 91.7 (89.4-93.5) | 93.1 (90.9-95.3) | 0.57 (0.40-0.82) | 0.55 (0.38-0.80) |

| Transplantation | |||||

| 1991-1995 | 815 | 94.2 (92.5-95.6) | 90.6 (87.9-93.4) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 1996-2000 | 1505 | 94.8 (93.6-95.8) | 91.9 (90.0-93.8) | 0.90 (0.62-1.29) | 0.86 (0.60-1.24) |

| 2001-2005 | 1862 | 95.3 (94.2-96.1) | 93.2 (91.7-94.6) | 0.82 (0.57-1.17) | 0.72 (0.50-1.03) |

| 2006-2010 | 2538 | 96.4 (95.6-97.1) | 94.9 (93.8-96.1) | 0.60 (0.42-0.86) | 0.52 (0.36-0.74) |

Hazard ratios are based on two-year survival.

Adjusted for fixed values of age (at start RRT / dialysis or kidney transplantation), sex and country.

Adjusted for age (at start RRT / dialysis or kidney transplantation), sex, and country.

Figure 5.

Trends in two-year patient survival in ADPKD versus non-ADPKD patients aged 60-65 years at onset of renal replacement therapy, overall and per specific treatment modality. Adjusted for age at start RRT, sex and primary renal disease (diabetes, hypertension, glomerulonephritis and other). Survival probabilities are standardised according to the following fixed values: age=60, males=60%, diabetes=20%, hypertension=17% and glomerulonephritis=15%). Abbreviations: RRT, renal replacement therapy; HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RTR, renal transplant recipients.

Trends in causes of death

The primary causes of death were divided into 5 categories (Figure 6). Cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death in both ADPKD and non-ADPKD patients. During the study period, the relative contribution of cardiovascular mortality to total mortality decreased from 53% to 29% (a decrease of 44%) in ADPKD patients and from 44% to 35% (a decrease of 20%) in non-ADPKD patients. These data indicate that in 1991-1995 the relative contribution of cardiovascular mortality to total mortality was higher in ADPDK patients than in non-ADPKD patients, whereas in 2006-2010 the opposite was true. Additional analyses showed that in ADPKD patients stroke mortality decreased from 10.0% to 6.7 % (a decrease of 33%) in 1990-1995 to 2006-2010. In a sensitivity analysis using an extended definition for cardiovascular mortality, i.e. adding mortality due to unknown causes to cardiovascular mortality per se, still a more pronounced reduction in cardiovascular mortality was noted in ADPKD patients when compared to non-ADPKD patients (a decrease of 23% versus 13%, respectively). No difference in cardiovascular mortality was observed between male and female patients (Supplementary Table 5). Furthermore, we investigated for ADPKD patients the causes of death per treatment modality separately. For renal transplant recipients the relative contribution of cardiovascular mortality to total mortality decreased from 62.6% to 5.3%, for hemodialysis from 50.1% to 26.4 % and for peritoneal dialysis from 46.6% to 31.0%.

Figure 6.

Trends in causes of death in patients on renal replacement therapy for ADPKD and non-ADPKD. Adjusted for to average age and gender distribution of all patients starting RRT between 1991 and 2010. Abbreviation: CV, cardiovascular.

Costs involved with renal replacement therapy

The population for this sub-study includes data of 12 registries (Supplementary Table 6), and comprises approximately 42% of the total population of the 27 European Union countries. In this population the costs involved with RRT for the 20.983 prevalent ADPKD patients receiving RRT in 2010 (number of patients on hemodialysis 7.457, peritoneal dialysis 1.078, first year of transplantation 1.636 and later after transplantation 10.879) are estimated to be approximately 651 million Euro per year with a 95% confidence interval of 473 – 829 million Euro. Using these data it can be extrapolated that in the 27 countries that are part of the European Union approximately 50,000 ADPKD patients received RRT in 2010, and that the costs involved with RRT for these patients were 1.5 billion Euro (95% confidence interval: 1.1-2.0 billion Euro).

Discussion

This study shows that across Europe the prevalence of ADPKD patients being dependent on RRT has increased considerably between 1991-1995 and 2006-2010. It also indicates that the relative contribution of ADPKD as cause of end-stage renal disease for which RRT is started has remained fairly stable during this period (approximately 10%). When compared to non-ADPKD patients that receive RRT, ADPKD patients are more likely to be living with a renal transplant, whereas peritoneal dialysis is as frequently used as treatment modality. The survival of ADPKD patients on RRT has improved significantly, mainly due to a marked reduction in cardiovascular mortality.

Differences in prevalence of RRT for ADPKD were observed among the countries participating in the ERA-EDTA registry. There are at least three possible explanations for these differences. First, a difference in prevalence could be explained by a difference in general population structure among the countries. However, after standardisation for age and sex to the 2005 EU27 population differences in prevalence remained. Second, the prevalence of the disease itself may be different between the participating countries. Several studies from Germany, France, Portugal and the United Kingdom have tried to establish country specific ADPKD prevalence data (30–33). Unfortunately, the methodology of these studies differs essentially, which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions on this issue. Third, the participating countries may have different policies with respect to acceptance of patients for RRT programs. Interestingly, we found that the ratio of ADPKD versus non-ADPKD patients on RRT was remarkably stable between countries. Countries with a low overall number of patients receiving RRT have also a low number of ADPKD patients receiving RRT and vice versa. It seems unlikely that countries with a low or high prevalence of ADPKD will have a proportionally low or high prevalence of non-ADPKD chronic kidney disease. In our opinion, these data suggest that differences among countries in prevalence of RRT for ADPKD are a reflection of differences in RRT acceptance policies that are dependent on social and economic motivations (34, 35). It cannot be excluded that environmental variables, such as CKD prevention programs, that affect ADPKD and non-ADPKD to the same extent may also play a role. However, as yet there is no treatment of which it is known to affect the course of ADPKD.

With respect to the different RRT modalities, we observed that renal transplantation is a more frequently used modality in ADPKD patients compared to non-ADPKD patients. This is in line with literature (11). A case-control study from the USRDS found that ADPKD patients were transplanted at a two-fold higher rate than controls. This may be due to the fact that in general ADPKD patients are younger when they reach end-stage renal disease than non-ADPKD patients (36). However, even after adjustment for age it appeared that more ADPKD patients were renal transplant recipients than non-ADPKD patients, especially of kidneys of deceased donors (Supplementary Figure 1). It may well be that is due to ADPKD patients having less co-morbidity and therefore are more likely to be accepted on the transplant waiting list. With respect to peritoneal dialysis, ADPKD patients were as likely to be on this treatment modality as non-ADPKD patients, and mortality in these ADPKD patients after starting peritoneal dialysis was lower. Of course selection bias should be considered, because patients with very large polycystic kidneys and/or livers peritoneal dialysis may be less often offered the option of peritoneal dialysis (37), but these data suggest that peritoneal dialysis is a safe treatment option in ADPKD patients that reach end-stage renal disease.

We observed an increase of 60.4% in the prevalence of ADPKD subjects on RRT from 1991-1995 to 2006-2010. Prevalence of RRT is influenced predominantly by two factors, incidence and survival on RRT. We observed in the countries participating in the ERA-EDTA registry that the incidence rate of RRT for ADPKD remained relatively stable at 7.6 pmp in 1991-1995 vs. 8.3 pmp in 2006-2010 (36). Because of the abundance of information, data on incident RRT will be presented in detail in a separate report. In contrast, survival on RRT has improved considerably in ADPKD patients, making it the major contributing factor to the increase in the number of ADPKD patients being dependent on RRT. In line with literature, we show that ADPKD patients have a better survival compared to non-ADPKD patients, even after age, and sex adjustment (12). We add to existing literature that ADPKD patients have also better survival when compared to patients in whom also the kidney is the predominant diseased organ (i.e. patients with primary glomerulonephritis, Supplemental Table 4). Of note, the choice for a specific RRT modality is not a random process, but influenced by personal preferences of patients and their treating physicians. In addition, the survival of dialysis patients is determined from the start of RRT, whereas survival of renal transplant recipients is determined after their first transplantation and many will have been treated with dialysis before their transplantation. These considerations make that survival should not be compared between the various RRT treatment modalities, but they do allow evaluations of trends in time per treatment modality and comparisons between ADPKD and non-ADPKD patients per treatment modality.

The increase in survival that we observed is especially due to a marked reduction in cardiovascular mortality, which was more evident in ADPKD patients than in non-ADPKD patients. This reduction in cardiovascular mortality is not caused by a reduction in stroke, but mainly due to a decrease in non-stroke cardiovascular mortality. The cause of this improvement in cardiovascular mortality cannot be concluded from the present study. Observational studies have suggested that better risk factor management before and after start of RRT (i.e. improved blood pressure and cholesterol control) and improvements in quality of coronary interventions (i.e. CABGs and PCIs) may play a role (38–41), but it could also be due to an improvement in RRT.

The costs involved with RRT for ADPKD for the EU27 zone in 2010 were estimated to be approximately 1.5 billion Euro (95% confidence interval 1.1-1.9 billion Euro). To reduce the economic burden for the community at large, and of course to reduce the loss of quantity and quality of life of ADPKD patients, it is of utmost importance to prevent end-stage renal disease in this patient group. For a long time no treatment options were available to prevent renal function decline in this patient group. Recently, however, it was shown in a large scale RCT that the use of the vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist tolvaptan was associated with a decrease in rate of kidney growth and renal function decline when compared to placebo (42). However, this drug has not been registered for the indication ADPKD yet and is associated with side effects. Other treatment options are therefore necessary. A limited number of these has been tested in clinical trials, and sometimes the results were promising (43–46). Efficacy of these novel treatments, however, needs confirmation in large scale RCTs before they can be prescribed in clinical practice. Given these considerations more funding for ADPKD related clinical care and research is urgently needed to allow studies developing and testing new therapies.

We acknowledge that this study has limitations. First, the costs involved with RRT are difficult to determine. Country specific data on costs associated with RRT were obtained from literature, but they differ with respect to costs that are taken into account. Some countries included costs of for instance medication, costs of staffing and laboratory analyses, whereas other countries did not. The costs involved with RRT for ADPKD that we calculated should therefore be used as an estimate rather than as an exact figure. It should be noted that the true economic burden will even be considerably higher than this figure, because it only relates to medical costs involved with RRT, and not costs associated with for instance the loss of money earning capacity and the medical complications of affected patients. Second, not all countries in the European Union are participating in the ERA-EDTA Registry and for participating registries detailed information was not complete for all time periods. Average values for the evaluation of trends in time and survival analyses were therefore only calculated for countries that did have complete datasets during the four study periods. Notwithstanding, this study still covers 42% of the inhabitants of the European Union, representing more than 200 million people. This study reports, therefore, on the by far most comprehensive epidemiological dataset on ADPKD to date. Other strengths are that we took into account not only ADPKD, but also non-ADPKD patients on RRT, that we studied prevalence of RRT overall and per treatment modality, and that we investigated trends in RRT prevalence and survival over a 20 year time period.

In summary, these data provide the most comprehensive insight thus far in the epidemiology of end-stage renal disease for ADPKD for which RRT is started. These data show that in Europe the prevalence of RRT for ADPKD has markedly increased during the last two decades, but that the relative contribution of ADPKD to the overall RRT population has remained stable at approximately 10%. Importantly, survival of ADPKD patients on RRT has increased significantly, mainly due to a reduction in cardiovascular mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and the staff of all the dialysis and transplant units who contributed data via their national or regional renal registries.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

All authors declare that the results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format. None to declare is applicable for all the authors.

Contributor Information

ERA-EDTA is the acronym for the European Renal Association – European Dialysis and Transplantation Association. ERA-EDTA Registry collaborators:

J.M. Abad, Bazaga M. de los Ángeles García, F. Caskey, C. Couchoud, N.A. Fosalba, P. Finne, J. Heaf, A. Hoitsma, J. de Meester, W. Metcalfe, J. Pascual, M. Postorino, P. Ravani, E. Rodrigo, R.A. Torre, and O Zurriaga

the EuroCYST consortium:

D. Chauveau, O. Devuyst, T. Ecder, K.U. Eckardt, R.T. Gansevoort, A. Köttgen, A.C. Ong, K. Petzold, Y. Pirson, G. Remuzzi, R. Torra, R.N. Sandford, A.L. Serra, V. Tesar, G. Walz, and R.P. Wüthrich

WGIKD Steering Committee:

C. Antignac, R. Bindels, D. Chauveau, O. Devuyst, F. Emma, R.T. Gansevoort, P.H. Maxwell, A.C. Ong, G. Remuzzi, P. Ronco, and F. Schaefer

References

- 1.Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1287–1301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hateboer N, v Dijk MA, Bogdanova N, et al. Comparison of phenotypes of polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. European PKD1-PKD2 Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iglesias CG, Torres VE, Offord KP, Holley KE, Beard CM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of adult polycystic kidney disease, Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1935-1980. AmJKidney Dis. 1983;2:630–639. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(83)80044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabow PA. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:332–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grantham JJ. Clinical practice. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1477–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy M, Feingold J. Estimating prevalence in single-gene kidney diseases progressing to renal failure. Kidney Int. 2000;58:925–943. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Peso G, Bajo MA, Costero O, et al. Risk factors for abdominal wall complications in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2003;23:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadimeri H, Johansson AC, Haraldsson B, Nyberg G. CAPD in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. PeritDialInt. 1998;18:429–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S, Fan SL, Raftery MJ, Yaqoob MM. Long term outcome of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney diseases receiving peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2008;74:946–951. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott KC, Agodoa LY. Polycystic kidney disease at end-stage renal disease in the United States: patient characteristics and survival. ClinNephrol. 2002;57:208–214. doi: 10.5414/cnp57208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrone RD, Ruthazer R, Terrin NC. Survival after end-stage renal disease in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: contribution of extrarenal complications to mortality. AmJKidney Dis. 2001;38:777–784. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roscoe JM, Brissenden JE, Williams EA, Chery AL, Silverman M. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Toronto. Kidney Int. 1993;44:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes R, Kheradmand F, Winearls CG. Survival after starting renal replacement treatment in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a single-centre 40-year study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c42-7. doi: 10.1159/000334429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orskov B, Romming Sorensen V, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Strandgaard S. Improved prognosis in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Denmark. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2034–2039. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01460210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrier RW, McFann KK, Johnson AM. Epidemiological study of kidney survival in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63:678–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dijk PC, Jager KJ, de Charro F, et al. Renal replacement therapy in Europe: the results of a collaborative effort by the ERA-EDTA registry and six national or regional registries. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1120–1129. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.6.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eurostat. European Harmonised indices of consumer prices annual data 2004-2010. Eurostat statistics Office; Luxembourg: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haller M, Gutjahr G, Kramar R, Harnoncourt F, Oberbauer R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of renal replacement therapy in Austria. NephrolDialTransplant. 2011;26:2988–2995. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleemput I, Beguin C, de la Kethule Y, et al. Organisation et financement de la dialyse chronique en Belgique. Heath Technology Assessment (HTA). Bruxelles Centre federal d’expertise des soins de sante (KCE), 2010. KCE Reports 124B. 2010 Dec [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maschoreck TR, Sorensen MC, Andresen M, Hogsberg IM, Rasmussen P, Sogaard J. Cost analysis of dialysis treatment at the Odense University Hospital and the Sonderborg Hospital. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160:7418–7424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salonen T, Reina T, Oksa H, Sintonen H, Pasternack A. Cost analysis of renal replacement therapies in Finland. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:1228–1238. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blotiere PO, Tuppin P, Weill A, Ricordeau P, Allemand H. The cost of dialysis and kidney transplantation in France in 2007, impact of an increase of peritoneal dialysis and transplantation. Nephrol Ther. 2010;6:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. An estimate of lifelong costs and QALYs in renal replacement therapy based on patients’ life expectancy. Health Policy. 2008;86:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tediosi F, Bertolini G, Parazzini F, Mecca G, Garattini L. Cost analysis of dialysis modalities in Italy. Health Serv Manage Res. 2001;14:9–17. doi: 10.1177/095148480101400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neil N, Walker DR, Sesso R, et al. Gaining efficiencies: resources and demand for dialysis around the globe. Value Health. 2009;12:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villa G, Rodriguez-Carmona A, Fernandez-Ortiz L, et al. Cost analysis of the Spanish renal replacement therapy programme. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:3709–3714. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sennfalt K, Magnusson M, Carlsson P. Comparison of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis--a cost-utility analysis. Perit Dial Int. 2002;22:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Wit GA, Ramsteijn PG, de Charro FT. Economic evaluation of end stage renal disease treatment. Health Policy. 1998;44:215–232. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(98)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baboolal K, McEwan P, Sondhi S, Spiewanowski P, Wechowski J, Wilson K. The cost of renal dialysis in a UK setting--a multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1982–1989. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies F, Coles GA, Harper PS, Williams AJ, Evans C, Cochlin D. Polycystic kidney disease re-evaluated: a population-based study. Q J Med. 1991;79:477–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann HP, Jilg C, Bacher J, et al. Epidemiology of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: an in-depth clinical study for south-western Germany. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon P, Le Goff JY, Ang KS, Charasse C, Le Cacheux P, Cam G. Epidemiologic data, clinical and prognostic features of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in a French region. Nephrologie. 1996;17:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Almeida E, Sousa A, Pires C, Aniceto J, Barros S, Prata MM. Prevalence of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in Alentejo, Portugal. Kidney Int. 2001;59:2374. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caskey FJ, Kramer A, Elliott RF, et al. Global variation in renal replacement therapy for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2604–2610. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Covic A, Schiller A. Burden of disease - prevalence and incidence of ESRD in selected European regions and populations. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(Suppl 1):S23–7. doi: 10.5414/cnp74s023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spithoven EM, Kramer A, Meijer E, Orskov B. Incidence of renal replacement therapy for ADPKD in Europe. Abstract ASN. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goffin E, Pirson Y. Is peritoneal dialysis a suitable renal replacement therapy in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2009;5:122–123. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou W, Lv J, Perkovic V, et al. Effect of statin therapy on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1807–1817. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.John M. Anonymous Comparative Effectiveness Review Summary Guides for Clinicians. Rockville (MD): 2007. Eisenberg Center for Clinical Decisions and Communications Science. Adding ACEIs and/or ARBs to Standard Therapy for Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Benefits and Harms. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patch C, Charlton J, Roderick PJ, Gulliford MC. Use of antihypertensive medications and mortality of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:856–862. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiviott SD, White HD, Ohman EM, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with or without angiography: a secondary, prespecified analysis of the TRILOGY ACS trial. Lancet. 2013;382:605–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2407–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caroli A, Perico N, Perna A, et al. Effect of longacting somatostatin analogue on kidney and cyst growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ALADIN): a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meijer E, Drenth JPH, d’Agnolo H, Casteleijn NF. Rationale and design of the DIPAK 1 Study: A randomised, controlled clinical trial assessing the efficacy of Lanreotide to halt disease progression in ADPKD. AJKD. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jardine MJ, Liyanage T, Buxton E, Perkovic V. mTOR inhibition in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): the question remains open. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:242–244. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stallone G, Infante B, Grandaliano G, et al. Rapamycin for treatment of type I autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (RAPYD-study): a randomized, controlled study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3560–3567. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.