Abstract

Misregulation of gut function and homeostasis impinges on the overall wellbeing of the entire organism. Diarrheal disease is the second leading cause of death in children under 5 years of age, and globally, 1.7 billion cases of childhood diarrhea are reported every year. Accompanying diarrheal episodes are a number of secondary effects in gut physiology and structure, such as erosion of the mucosal barrier that lines the gut, facilitating further inflammation of the gut in response to the normal microbiome. Here, we focus on pathogenic bacteria-mediated diarrhea, emphasizing the role of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate and cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in driving signaling outputs that result in the secretion of water and ions from the epithelial cells of the gut. We also speculate on how this aberrant efflux and influx of ions could modulate inflammasome signaling, and therefore cell survival and maintenance of gut architecture and function.

Keywords: cAMP, cGMP, cholera toxin, inflammasome, receptor guanylyl cyclase C, salmonellosis

1. Introduction

Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cGMP) are key nucleotide second messengers that are exploited by various pathogenic bacteria during the course of infection and persistence in host cells [1–3]. Levels of cyclic nucleotides are increased markedly during some bacterial infections, and because they orchestrate fluid and electrolyte imbalance, these signaling molecules may have a broader role in virulence [3–5]. In contrast, recent studies demonstrated that cyclic nucleotides, particularly cGMP, can have a protective role in gut infection [6,7]. Here, we discuss important insights that have been gained into the role of cyclic nucleotides in the context of three common bacterial gut infections, namely cholera, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) infection, and salmonellosis. As the actions of cyclic nucleotides in the gut often lead to ion imbalances, we speculate on how this may impinge on the innate immune system via the inflammasome.

Cholera

Cholera is an important public health issue worldwide. Recent estimates indicate high burden of cholera in 69 endemic countries with ~ 2.9 million cases and 95 000 deaths annually [8]. Cholera toxin (CTX), a virulence factor produced by Vibrio cholerae, was discovered by Sambhu Nath De in Kolkata in 1959 by demonstrating that a bacteria-free culture filtrate can result in profound fluid accumulation in ligated rabbit ileal loops [9]. A decade later, Goldberg et al. reported that CTX specifically induces cAMP production, but not cGMP production, in canine intestinal mucosa [10,11]. Arguably, the pathogenesis of cholera mediated by cAMP signaling is one of the most thoroughly studied and best understood diarrheal disease mechanisms.

Vibrio cholerae is transmitted by the fecal–oral route, whereupon it colonizes intestinal crypts and releases CTX, an enterotoxin with a monomeric A (enzymatic) subunit divided into two domains (A1 and A2) inside a pore formed by the pentameric B (binding) subunit [12]. The B subunit ring of the CTX binds to GM1 ganglioside receptor on the plasma membrane of the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), triggering endocytosis and retrograde trafficking of the toxin to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) via the trans-Golgi network [5]. In the ER, the A1 chain unfolds and mimics an ER-associated degradation substrate to get access to the cytoplasm, where it refolds and escapes ubiquitination and degradation. Constitutive activation of adenylyl cyclase by A1 chain-mediated ADP ribosylation of Gs alpha subunit (Gas) protein results in pathological increases in cAMP [13].

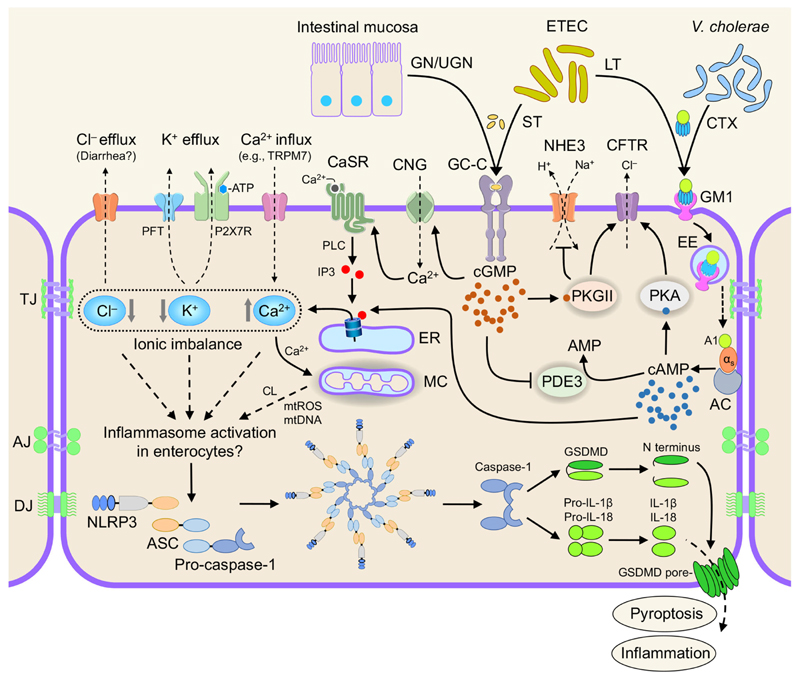

One of the key downstream effectors of cAMP is protein kinase A (PKA), which in turn phosphorylates and stimulates the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) ion channel. Sustained activation of CFTR by CTX causes hypersecretion of anions, chloride and bicarbonate into the intestinal lumen [4,5]. To preserve electroneutrality and osmotic balance, rapid loss of sodium ions and water follows, resulting in acute watery diarrhea in the form of ricewater stool of up to 1 L·hour−1, severe dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance that can be fatal within hours if left untreated [4,5,14]. Consistent with this model of CTX action, strong linear correlation was observed between fecal cAMP levels and fluid loss in cholera patients [15]. Furthermore, CFTR-null mice showed reduced fluid secretion in the intestine in response to CTX, despite intracellular accumulation of cAMP, providing evidence for the crucial role of CFTR in cholera pathophysiology (Fig. 1) [16].

Figure 1. Proposed model for ionic regulation of inflammasomes in enterocytes.

Vibrio cholerae, ETEC, and Salmonella modulate ionic balance through various mechanisms. The LT produced by ETEC and the closely related CTX act on Gas proteins and increase cAMP levels. Endogenous hormones GN and UGN or ST produced by ETEC binds to GC-C and stimulates the production of cGMP. cGMP directly stimulates the CFTR, CNG, and PKGII and inhibits PDE3. CNG stimulates CaSR surface expression and signaling, which results in the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) and increased production of IP3 and release of intracellular Ca2+ from the ER. Elevated intracellular cAMP levels could also increase intracellular Ca2+ by modulating IP3 receptors. NLRP3 inflammasome activation could proceed through ionic imbalances and cyclic nucleotide signaling as suggested in the text and depicted in the figure. Note that the evidence for activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by disturbances in intracellular ion fluxes has been suggested largely from studies on professional immune cells, such as macrophages. AC: adenylyl cyclase; AJ: adherens junction; CL: cardiolipin; DJ: desmosome junction; EE: early endosome; MC: mitochondria; mtROS: mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; TJ: tight junction.

In addition to its role in CFTR activation, cAMP could contribute to cholera pathogenesis through additional mechanisms. For instance, attenuation of Na+ absorption due to reduced expression of Na+/H+ exchangers (e.g., NHE3) and enhancement of HCO3− secretion due to stimulation of Cl−/HCO3− exchangers (e.g., DRA/downregulated in adenoma) could act in parallel to cause diarrhea [17,18]. Furthermore, CTX-driven cAMP increase was reported to inhibit autophagy by suppressing autophagosome maturation, which might help bacteria escape host defense [19]. CTX was shown to inhibit phagocytosis and inter-leukin-12 (IL-12) cytokine production [20,21], and CTX-mediated cAMP increase was shown to disrupt intestinal barrier function by inhibiting exocyst-mediated trafficking of proteins, including E-cadherin and Notch signaling components, to cell–cell junctions [22].

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection

Enterotoxigenic E. coli strains cause diarrheal disease that is widespread in developing countries and a leading cause of pediatric morbidity and mortality worldwide. ETEC is also the most common causative agent isolated in traveler’s diarrhea [23]. Following ingestion via the fecal–oral route, ETEC colonizes and adheres to the small intestinal mucosa and elaborates two enterotoxins, a heat-labile toxin (LT) and a heat-stable toxin (ST) [24]. Evans et al. first described the mechanism of LT-mediated adenylate cyclase activation using pigeon erythrocyte membranes [25]. Soon afterward, Hughes et al. and Field et al. independently reported the ability of ST to increase cGMP by activation of the receptor guanylate cyclase C in IECs [26,27]. Consistent with these observations, patients infected with E. coli expressing only ST had markedly lower fecal cAMP as compared to infection with E. coli expressing both LT and ST [28]. The ST peptide elicits a rapid rise in secretory response followed by a gradual decay. On the other hand, LT results in a slow and sustained increase in fluid accumulation [29].

Labile toxin is strikingly similar to CTX, in terms of structure, function, and immune response [30]. Studies determining evolutionary origins of the toxins indicated that LT is horizontally acquired from V. c-holerae [31]. Like CTX, LT is composed of a single A subunit incorporated within a ring of five B subunits [32]. The catalytically active A1 fragment of LT activates adenylate cyclase causing an increase in cAMP levels, which in turn results in CFTR activation and Cl- secretion in host cells (Fig. 1) [30,32]. Although both LT and ST have been documented to cause hypersecretion of fluid and electrolytes, activation of adenylate cyclase and cAMP production by LT is recognized as the major contributor to ETEC pathogenesis and mediates principal virulence functions such as bacterial adhesion and disruption of intestinal fluid homeostasis [33,34]. The exact mechanism by which LT enhances bacterial adhesion to host cells remains unclear. One potential scenario is that cAMP released by the host cells into the intestinal lumen is sensed by ETEC to promote adherence to host cells [35]. Of note, microaerophilic conditions and media rich in glucose and salt induce LT expression [36,37]. Thus, glucose-regulated enhancement of ETEC adhesion might be mediated, in part, by LT production and increase in cAMP release by IECs [38]. On the other hand, exposure of ETEC to short-chain fatty acids in the colon may reduce the production of LT to aid shedding of bacteria into the feces to continue the chain of infection [39,40]. Most insights concerning cAMP-regulated cellular phenotypes have come from cell culture studies. In addition to enhancing bacterial adhesion and secretory response, both LT and CTX induce morphological alterations of cells in multiple cell models, but the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unknown [41–43]. Furthermore, in vitro studies in the Caco-2 cell line suggested that the increase in intracellular cAMP level during ETEC infection could inhibit intestinal vitamin B1 (thiamin) uptake and contribute to malnutrition in diarrhea [44].

The heat-stable enterotoxin (ST) is an 18-amino acid peptide with three disulfide bridges and is structurally and functionally similar to endogenous hormones, guanylin (GN) and uroguanylin (UGN) [2]. Studies in vitro and in vivo have established the guanylyl cyclase C (GUCY2C or GC-C), a protein predominantly expressed on the apical surface of IECs, as the bona fide ST receptor [2,45–47]. GC-C is a multidomain protein and, like other members of the receptor guanylyl cyclase family, consists of an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane domain, a juxtamembrane domain, a pseudokinase domain, and a C-terminal guanylyl cyclase domain [48]. Binding of endogenous paracrine hormones (GN and UGN) or the superagonist ST peptide to GC-C results in elevated guanylyl cyclase activity and production of cGMP. The cGMP signaling cascade in the intestine has two downstream elements: activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase II (PKGII) and inhibition of cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE3). PKGII activation leads to the stimulation of CFTR and concurrent inhibition of NHE3. On the other hand, cGMP-mediated inhibition of PDE3 might also stimulate CFTR through the cross-activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) [2]. The net effect is increase in chloride secretion and reduction in sodium absorption, resulting in watery diarrhea (Fig. 1) [2]. In addition, GC-C stimulation enhances duodenal bicarbonate secretion and increases Ca2+ influx through cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNG) [49,50]. The GC-C/cGMP axis can also activate cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 leading to cytostasis and cellular senescence [51]. The model of ST-induced, GC-C-mediated diarrhea was tested by examining wild-type and GC-C knockout mice orally challenged with ST peptide or infection with ETEC. Under both conditions, GC-C-null mice were resistant to ST-mediated diarrhea [45,46]. The recent identification of a familial diarrhea syndrome caused by gain-of-function mutations in GC-C further supports the mechanism of GC-C activation in ST-mediated diarrhea [52,53].

Salmonellosis

Salmonellosis is a common foodborne illness caused by Salmonella enterica sp., with serovars Typhi, Paratyphi, and Typhimurium exemplifying important human pathogens. Recent global estimates of disease burden reported 90 300 deaths from nontyphoidal and 178 000 deaths from typhoidal salmonellosis in 2015 [54]. Given that Salmonella is an invasive pathogen, the pathogenesis of salmonellosis is different from that of cholera and ETEC. Studies using ligated rabbit ileal loops infected with Salmonella Typhimurium strains showed fluid accumulation to a similar extent as that of cholera loops. Salmonella-challenged loops, however, contained more mucus than V. cholerae-infected loops. More importantly, both S. Typhimurium and V. cholerae infection exhibited similar potential to increase mucosal cAMP levels [55]. Apart from causing secretory diarrheal phenotypes, the increase in cAMP levels in salmonellosis could impact multiple cellular pathways, including inhibition of autophagy to facilitate intracellular bacterial survival and replication [19].

Three potential mechanisms could explain the induction of cAMP in salmonellosis. The first could be the presence of a putative enterotoxin, similar to CTX and LT, that activates adenylate cyclase causing an increase in intracellular cAMP concentration [56]. Independent studies demonstrating that a cell-free lysate of S. Typhimurium can induce cAMP levels in isolated intestinal cells and fluid accumulation in ligated ileal loops support an enterotoxin-mediated mechanism [57,58], although the molecular nature of this toxin remains to be elucidated. Second, activation of adenylate cyclase may be due to prostaglandins released upon tissue damage during Salmonella infection. This mechanism is supported by the fact that indomethacin, an anti-inflammatory drug that acts primarily through the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, inhibited Salmonella-induced adenylate cyclase activity and cAMP accumulation [59]. Third, S. Typhimurium infection releases a large quantity of extracellular ATP, in amounts similar to those found in enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) infection, which is broken down to adenosine in the intestinal lumen [60]. Extracellular adenosine is an important mediator of inflammation of the intestinal mucosa and acts by interacting with adenosine receptor 2B, causing a marked rise in cAMP levels in host cells [61]. Adenosine and cAMP are reported to be potent regulators of S. Typhimurium infection-triggered pro-inflammatory IL-6 cytokine production [62]. In addition, adenosine-driven rise in cAMP could activate CFTR and result in Cl− secretion and secretory diarrhea [61]. Although the later mechanism has not been explored in the context of Salmonella infection, there are reports in the literature describing potent Cl secretory response mediated by adenosine that could contribute to watery diarrhea in EPEC infection [63]. In this context, it is worth noting that the two transport proteins well documented to play a role in EPEC diarrhea, namely NHE3 and DRA, are also regulated by cyclic nucleotides [4,5]. Cyclic GMP signaling is known to play a key role in diverse cellular functions, and their contribution to the pathogenesis of enteroinvasive infection has been recognized. For instance, apart from inducing cAMP levels in the host, enteroinvasive bacteria such as Salmonella serovar Dublin and enteroinvasive E. coli were shown to increase cGMP concentration [64]. Likewise, the increase in nitrated cGMP (8-nitro-cGMP) during infection with S. Typhimurium is thought to mediate nitric oxide (NO)-regulated cyto-protective and antimicrobial host defense [65]. Stronger evidence emerged from recent studies discovering a critical role for receptor guanylyl cyclase C (GC-C)/ cGMP axis in protecting the intestinal mucosa from invasive S. Typhimurium infection [6].

Studies in the GC-C-null mice documenting accelerated mortality during oral S. Typhimurium, but not by intraperitoneal infection, provided most definitive evidence for the role for GC-C in providing protection against enteroinvasive infections [6]. Consistent with this finding, in vitro and in vivo studies indicated that GC-C deficiency enhanced S. Typhimurium invasion of the intestinal epithelium [7]. General stress response markers including raised serum cortisol, thymic atrophy, and depletion of CD4/CD8 thymocytes were exacerbated in Salmonella-infected GC-C-null mice [6]. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the ileum showed elevated cytokine and chemokine expression, and histopathological examination showed marked epithelial damage, submucosal edema, thinning of mucus lining, loss of goblet cells, focal tufting, and distortion of the crypt–villus architecture in GC-C-null mice following oral S. Typhimurium infection [6,7]. Mechanistically, Salmonella infection downregulates GC-C-cGMP axis and suppresses IL-22-mediated host antimicrobial defenses and alters the gut microbiome [6].

Guanylyl cyclase C-null mice infected with Citrobacter rodentium, the natural rodent pathogen closely related to EPEC and enterohemorrhagic E. coli, also showed enhanced susceptibility and systemic dissemination, indicating compromised immune defenses against an attaching–effacing enteric bacterial pathogen [66]. Taken together, the unique mechanism linking cGMP signaling, mucosal homeostasis, and host immunity established GC-C as a key player guarding host intestine from some enteric pathogens. Given the importance of GC-C signaling in intestinal barrier function, and the use of linaclotide and plecanatide, two recently FDA-approved oral GC-C agonists for managing irritable bowel syndrome with constipation [67], this opens up new possibilities for treating enteroinvasive diseases.

Ionic regulation of inflammasomes and pyroptotic cell death

The activation of inflammatory and immune pathways during infection, for example, by Toll-like receptors, is well understood. Here, we discuss pathways called the inflammasomes which have emerged as important mediators of inflammation, and potential regulation of their function by ionic imbalances induced by bacterial enterotoxins.

The inflammasome is an intracellular multiprotein complex that detects pathogenic microorganisms and sterile stressors, resulting in the production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 and subsequent cell death by pyroptosis. Inflammasomes play a central role in mucosal innate immunity and provide the first-line host defense against enteric infections [68,69]. Inflammasomes assemble through the actions of sensor proteins that include the family of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD), leucine-rich repeat domain proteins containing a pyrin domain or caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD), absent in melanoma 2-like receptors, or the protein pyrin. These proteins oligomerize to recruit and activate caspase-1 through an adaptor protein called apoptotic speck-containing protein with CARD (ASC). Upon activation, inflammasomes form single ‘foci’ or ‘specks’ which contain the sensor, ASC, and caspase-1. The catalytic activation of caspase-1 results in proteolytic maturation of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 and the cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD). The N terminus of cleaved GSDMD forms pores that result in loss of ions and influx of water, resulting in cell swelling and lysis during pyroptosis.

Studies have shown that ionic imbalances can trigger pyroptosis through the activation of inflammasomes. For instance, altered K+ or Cl− ion fluxes activate the NOD, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome sensor [70]. NLRP3 inflammasome assembly is also mediated by physico-chemically distinct cues that include endogenous danger signals (e.g., ATP) or metabolites (e.g., fatty acids) [71]. The ubiquitously expressed two-pore domain K+ channel subfamily K member 6 (also known as TWIK2) has been implicated in K+ efflux during NLRP3 activation in macrophages [72]. Pannexin-1 channels indirectly activate NLRP3 by promoting the release of ATP which activates its P2X purinoceptor 7 (P2X7R), a large nonspecific channel, stimulating NLRP3 through loss of ions, including K+. Recombinant ASC protein can form inflammasome-like aggregates in the presence of low K+ in vitro, which suggests that features inherent in its structure may facilitate the response to low K+ [73].

In the gut, P2X7R and pannexin-1 are expressed in enteric neurons. P2X7R–pannexin-1 signaling and ASC-dependent death of neurons and glia have been studied in a mouse model of Crohn’s disease [74]. The inhibition of pannexin-1 with probenecid in vivo reduced glial responses. Inhibition of caspases with zVAD in cultured enteric neurons prevented cell death, suggesting a role for inflammasomes in these processes. In colitic mice, the loss of enteric neurons was correlated with decreased electrical field stimulation (EFS)-driven colon relaxation and elevated EFS-driven contractions. Despite the role of P2X7R in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease and its increased expression in Crohn’s disease mucosa [75], P2X7R antagonists (e.g., AZD9056) have shown little efficacy in preventing symptoms of Crohn’s disease; however, the reduction in abdominal pain indicates a more important role for P2X7R in nociception [76,77].

During infection, NLRP3 assembly and caspase-1 activation can be induced directly by K+ efflux driven by bacterial pore-forming toxins (PFTs), including those produced by enteric pathogens [78–80]. Gramnegative bacteria can directly activate caspase-4 or cas-pase-5, which serve as cytosolic receptors for bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). EPEC [81], Salmonella, and other enteric Gram-negative bacteria [82] can activate caspase-4/5, which cleave GSDMD, leading to pore formation and K+ efflux. This caspase-4/5-dependent, ‘noncanonical’ NLRP3-activation pathway is unique to Gram-negative bacteria and distinct from ‘canonical’ NLRP3 activation by PFTs, P2X7R, and pannexin-1 [70]. Blocking K+ efflux, for example, by antagonists of P2X7R (e.g., A438079, AZ11645373, AZ11648720, AZ10573295), pannexin-1 (e.g., probenecid), or ATP-sensitive K+ channels (e.g., glibenclamide) inhibits NLRP3 activation and inflammation [83]. Thus, the reduction of cellular K+ is a common and widespread mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation that can be impaired by high extracellular K+ concentrations [70].

In addition to K+, the loss of Cl− ions can trigger ASC focus formation in an NLRP3-dependent manner [84]. The exposure of LPS-treated macrophages to culture medium lacking both K+ and Cl− (e.g., by using Na-gluconate for ionic and osmotic balance) results in the spontaneous assembly of inflammasomes containing NLRP3 and ASC specks and activation of cas-pase-1. However, loss of Cl− alone triggers NLRP3-dependent assembly of ASC specks, a reduction in K+-triggered NLRP3 assembly, interaction with the activator NEK7, and caspase-1 activation. It is plausible that reduced intracellular Cl− primes inflammasomes and reduces the threshold for full activation by a second trigger that stimulates K+ efflux. This would increase the risk of inflammation in conditions where luminal Cl− is constitutively elevated, for example, in familial chloride diarrheas that arise from inactivating mutations in the Cl− /HCO3− exchanger DRA (SLC26A3) expressed on the apical surface of IECs [85,86]. Inflammasome activation can therefore be blocked with Cl− channel blockers such as 4-(2-butyl-6,7-dichloro-2-cyclopentylindan-1-on-5-yl)oxybutyric acid, flufenamic acid (an nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug), and 5-nitro-1-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid [84].

An alternative mechanism mediated by K+-induced translocation of chloride intracellular channels to the plasma membrane and consequent Cl− efflux has been demonstrated [87]. Further studies are required to demonstrate whether basolaterally secreted K+ ions in IECs, the key to fluid release during diarrhea [4], affect NLRP3 activation.

Cyclic nucleotides, Ca2+, and NLRP3: a potential link?

Ca2+ is also an important regulator of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Murine G protein-coupled Ca-sensing receptor (CaSR; encoded by G protein-coupled receptor family C group 2 member A) activates NLRP3 through the generation of inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), which releases Ca2+ from the ER [88]. In addition to Ca2+, CaSR responds to cations such as Gd3+ and the allosteric agonist R568. In human monocytes, both CaSR and the related G protein-coupled receptor family C group 6 member A, which signals via Gaq, trigger NLRP3 activation in response to high extracellular Ca2+ [89]. High intracellular Ca2+ that can be induced, for example, by thapsigargin (which inhibits the sequestration of cytosolic Ca2+ into the ER) may trigger NLRP3 activation. Uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria, leading to elevated ROS, cardiolipin exposure, and release of mtDNA can all increase NLRP3 activation in macrophages. Plasma membrane calcium channels such as transient receptor potential melastatin 2, transient receptor potential melastatin 7, and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 2 have also been linked to NLRP3 inflammasome activation, for example, in response to cell swelling [90,91]. In summary, these studies indicate that elevated cytosolic Ca2+ can trigger NLRP3 inflammasomes, inflammatory cytokine release, and pyroptosis.

Importantly, CTX, which increases cytoplasmic cAMP and Ca2+ (via modulation of IP3 receptors; Fig. 1), triggers activation of inflammasomes [79,92,93]. However, the exact mechanisms by which cAMP regulates inflammasome activity remain to be clarified. For example, both adenosine receptor-mediated increases in cAMP levels [94] and CaSR-mediated reduction in cAMP increased inflammasome activity [88].

No less fascinating, though far less understood, is how and if cGMP signaling could impact inflammasome pathways. Notably, NO, an activator of soluble guanylyl cyclase and inducer of cGMP levels, was found to suppress activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. However, this effect was found to be independent of cGMP [95]. Furthermore, unlike cAMP, no interaction was observed between cGMP and endogenous NLRP3 [88]. However, studies on GC-C have provided insights into the potential role of cGMP signaling in inflammasome activation. The GC-C/cGMP axis stimulates CNG, resulting in an increase in Ca2+ influx and post-transcriptional induction of CaSR surface expression and signaling [50]. Thus, cGMP-mediated effects on cytoplasmic Ca2+ and CaSR expression could represent a previously unrecognized mechanism of cGMP-mediated regulation of inflammasome pathways (Fig. 1).

Activation of inflammasomes during enteric infections could act as a barrier to limit the bacterial burden and systemic spread of pathogens. Indeed, the inflammasome is a major component of the innate immune system that is induced early in the intestinal mucosa in patients with cholera [96]. Therefore, it is not surprising that the genetic resistance to cholera in humans involved natural selection of genes of the inflammasome pathway and K+ channels involved in cyclic AMP-mediated chloride secretion [97].

Studies conducted using mouse models also support a key role for inflammasome activation in response to V. cholerae infection [98]. Toxins secreted by V. cholerae can activate the inflammasome in a variety of ways. For example, CTX has been shown to specifically induce release of IL-1β through an ASC-dependent but NLRP3-independent pathway, whereas the PFT hemolysin, secreted by El Tor biotype strains, triggers the NLRP3–ASC-dependent inflammasome [79]. Other Gram-negative enteric pathogens, such as E. coli (including ETEC), C. rodentium, and S. Typhimurium, have been shown to activate the inflammasome through cytosolic sensing of their LPS [81,82,98,99].

It is important to note that certain enteric bacteria have also adopted inflammasome-evasion strategies crucial for virulence. For example, following cellular invasion, Salmonella downregulates expression of flagellin and type 3 secretion system to attenuate caspase-1 responses [100]. Thus, taken together, inflammasome activation is common to enteric infections where cAMP and cGMP play crucial roles, but molecular links between these second messengers and the inflammasome are as yet unknown.

Conclusions

Gut microbiota play an important role in protecting against diarrheal infection as well contributing to inflammation in chronic gut diseases [101,102]. Ion transport across IECs may play an important role in the establishment and maintenance of the gut microbiota [103]. Indeed, prominent depletion of Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium and an increase in Enterobacteriaceae have been described in patients with an activating mutation in GC-C that is characterized by dysregulated intestinal ion transport, secretory diarrhea, and chronic mucosal inflammation [104]. Independent studies have also reported alterations in the gut microbiota composition in GC-C-null mice and a decrease in the relative abundance of Lactobacillus spp., members of which have been implicated in inflammasome activation through caspase-1-dependent processing and release of IL-1b by macrophages [6,66,105]. These findings support an alternate model in which cyclic nucleotide signaling in enterocytes could regulate inflammasome activation by shaping the gut microbiota and modulating host–microbe cross talk. Thus, prolonged inflammasome activation may explain why chronic inflammation is seen in patients with activating mutations in GC-C, with a considerable number of them diagnosed with Crohn’s disease [104].

In summary, it is attractive to speculate that cyclic nucleotides may play a complex role in the regulation of inflammasomes in the context of enteric infections. The host has evolved redundant systems to detect and respond to pathogens, and on the other hand, pathogens can subvert inflammasome signaling to increase virulence. The effects of ionic imbalances, which underlie diarrhea, on inflammation need to be better understood to appreciate the broader impact of infection on physiological and immune homeostasis in the gut.

Acknowledgements

HP is an Early Career Fellow of the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance (IA/E/17/1/503665). SSV is supported by a Margdarshi Fellowship from the DBT/ Wellcome Trust India Alliance (IA/M/16/1/50260621/ 06/2017) and by a JC Bose Fellowship from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (SB/S2/JCB-18/2013). ARS would like to acknowledge support from the Medical Research Council, UK (MR/P022138/1).

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- AJ

adherens junction

- ASC

apoptotic speck-containing protein with caspase activation and recruitment domain

- CARD

caspase activation and recruitment domain

- CaSR

calcium-sensing receptor

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CL

cardiolipin

- CNG

cyclic nucleotide-gated channels

- CTX

cholera toxin

- DJ

desmosome junction

- DRA, downregulated in adenoma

- EE

early endosome

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- EPEC

enteropathogenic Escherichia coli

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ETEC

enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli

- GN

guanylin

- GSDMD

gasdermin D

- GUCY2C/GC-C

guanylyl cyclase C

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cell

- KCNK6

K+ channel subfamily K member 6

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LT

heat-labile toxin

- MC

mitochondria

- mtROS

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

- NHE3

Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3

- NLRP3, NOD

leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain containing protein 3

- NOD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- P2X7R

P2X purinoceptor 7

- PDE3

cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase

- PFT

pore-forming toxin

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKGII

cGMP-dependent protein kinase II

- ST

heat-stable toxin

- TJ

tight junction

- UGN

uroguanylin

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All authors wrote the paper and finalized the manuscript.

References

- 1.Johnson RM, McDonough KA. Cyclic nucleotide signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an expanding repertoire. Pathog Dis. 2018;76 doi: 10.1093/femspd/fty048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arshad N, Visweswariah SS. The multiple and enigmatic roles of guanylyl cyclase C in intestinal homeostasis. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2835–2840. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serezani CH, Ballinger MN, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Cyclic AMP: master regulator of innate immune cell function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:127–132. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0091TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiagarajah JR, Donowitz M, Verkman AS. Secretory diarrhoea: mechanisms and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:446–457. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viswanathan VK, Hodges K, Hecht G. Enteric infection meets intestinal function: how bacterial pathogens cause diarrhoea. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:110–119. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majumdar S, Mishra V, Nandi S, Abdullah M, Barman A, Raghavan A, Nandi D, Visweswariah SS. Absence of receptor guanylyl cyclase c enhances ileal damage and reduces cytokine and antimicrobial peptide production during oral Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 2018;86:e00799–17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00799-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amarachintha S, Harmel-Laws E, Steinbrecher KA. Guanylate cyclase C reduces invasion of intestinal epithelial cells by bacterial pathogens. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1521. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De SN. Enterotoxicity of bacteria-free culturefiltrate of Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 1959;183:1533–1534. doi: 10.1038/1831533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafer DE, Lust WD, Sircar B, Goldberg ND. Elevated concentration of adenosine 3’:5’-cyclic monophosphate in intestinal mucosa after treatment with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;67:851–856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.2.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafer DE, Lust WD, Polson JB, Hedtke J, Sircar B, Thakur AK, Goldberg ND. The possible role of cyclic AMP in some actions of cholera toxin. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1971;185:376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1971.tb45263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang RG, Scott DL, Westbrook ML, Nance S, Spangler BD, Shipley GG, Westbrook EM. The three-dimensional crystal structure of cholera toxin. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:563–573. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wernick NL, Chinnapen DJ, Cho JA, Lencer WI. Cholera toxin: an intracellular journey into the cytosol by way of the endoplasmic reticulum. Toxins (Basel) 2010;2:310–325. doi: 10.3390/toxins2030310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK. Cholera. Lancet. 2004;363:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aye K, Khin Maung U. Correlation of fecal cAMP with fluid loss in cholera. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1990;43:80–82. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(90)90011-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabriel SE, Brigman KN, Koller BH, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Cystic fibrosis heterozygote resistance to cholera toxin in the cystic fibrosis mouse model. Science. 1994;266:107–109. doi: 10.1126/science.7524148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramanya SB, Rajendran VM, Srinivasan P, Nanda Kumar NS, Ramakrishna BS, Binder HJ. Differential regulation of cholera toxin-inhibited Na-H exchange isoforms by butyrate in rat ileum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G857–G863. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00462.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tse C-M, Yin J, Singh V, Sarker R, Lin R, Verkman AS, Turner JR, Donowitz M. cAMP stimulates SLC26A3 activity in human colon by a CFTR-dependent mechanism that does not require CFTR activity. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7:641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahnazari S, Namolovan A, Mogridge J, Kim PK, Brumell JH. Bacterial toxins can inhibit host cell autophagy through cAMP generation. Autophagy. 2011;7:957–965. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.9.16435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun MC, He J, Wu CY, Kelsall BL. Cholera toxin suppresses interleukin (IL)-12 production and IL-12 receptor beta1 and beta2 chain expression. J Exp Med. 1999;189:541–552. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemialtowski M, Klucinski W, Malicki K, de Faundez IS. Cholera toxin (choleragen)-polymorphonuclear leukocyte interactions: effect on migration in vitro and Fc gamma R-dependent phagocytic and bactericidal activity. Microbiol Immunol. 1993;37:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb03179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guichard A, Cruz-Moreno B, Aguilar B, van Sorge NM, Kuang J, Kurkciyan AA, Wang Z, Hang S, Pineton de, Chambrun GP, McCole DF, et al. Cholera toxin disrupts barrier function by inhibiting exocyst-mediated trafficking of host proteins to intestinal cell junctions. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rojas-Lopez M, Monterio R, Pizza M, Desvaux M, Rosini R. Intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: insights for vaccine development. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:440. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czirok E, Semjen G, Steinruck H, Herpay M, Milch H, Nyomarkay I, Stverteczky Z, Szeness A. Comparison of rapid methods for detection of heat-labile (LT) and heat-stable (ST) enterotoxin in Escherichia coli. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:398–402. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-6-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill DM, Evan DJ, Jr, Evans DG. Mechanism of activation adenylate cyclase in vitro by polymyxin-released, heat-labile enterotoxin of Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1976;133(Suppl):103–107. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.supplement_1.s103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes JM, Murad F, Chang B, Guerrant RL. Role of cyclic GMP in the action of heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli. Nature. 1978;271:755–756. doi: 10.1038/271755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field M, Graf LH, Jr, Laird WJ, Smith PL. Heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli: in vitro effects on guanylate cyclase activity, cyclic GMP concentration, and ion transport in small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2800–2804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molla A, Lonnroth I, Jahan F, Bardhan PK, Molla AM, Holmgren J. Stool cyclic AMP in diarrhoea due to different causative organisms. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1985;3:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans DG, Evans DJ, Jr, Pierce NF. Differences in the response of rabbit small intestine to heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1973;7:873–880. doi: 10.1128/iai.7.6.873-880.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudrak B, Kuehn MJ. Heat-labile enterotoxin: beyond G(m1) binding. Toxins (Basel) 2010;2:1445–1470. doi: 10.3390/toxins2061445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto T, Gojobori T, Yokota T. Evolutionary origin of pathogenic determinants in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae O1. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1352–1357. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1352-1357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sixma TK, Pronk SE, Kalk KH, Wartna ES, van Zanten BA, Witholt B, Hol WG. Crystal structure of a cholera toxin-related heat-labile enterotoxin from E. coli Nature. 1991;351:371–377. doi: 10.1038/351371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berberov EM, Zhou Y, Francis DH, Scott MA, Kachman SD, Moxley RA. Relative importance of heat-labile enterotoxin in the causation of severe diarrheal disease in the gnotobiotic piglet model by a strain of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli that produces multiple enterotoxins. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3914–3924. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3914-3924.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Berberov EM, Freeling J, He D, Moxley RA, Francis DH. Significance of heat-stable and heat-labile enterotoxins in porcine colibacillosis in an additive model for pathogenicity studies. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3107–3114. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01338-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson AM, Kaushik RS, Francis DH, Fleckenstein JM, Hardwidge PR. Heat-labile enterotoxin promotes Escherichia coli adherence to intestinal epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:178–186. doi: 10.1128/JB.00822-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilligan PH, Robertson DC. Nutritional requirements for synthesis of heat-labile enterotoxin by enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1979;23:99–107. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.1.99-107.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trachman JD, Yasmin M. Thermoosmoregulation of heat-labile enterotoxin expression by Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol. 2004;49:353–360. doi: 10.1007/s00284-004-4282-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wijemanne P, Moxley RA. Glucose significantly enhances enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli adherence to intestinal epithelial cells through its effects on heat-labile enterotoxin production. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e113230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong JM, de Souza R, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:235–243. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takashi K, Fujita I, Kobari K. Effects of short chain fatty acids on the production of heat-labile enterotoxin from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1989;50:495–498. doi: 10.1254/jjp.50.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sack DA, Sack RB. Test for enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli using Y-1 adrenal cells in miniculture. Infect Immun. 1975;11:334–336. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.2.334-336.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guerrant RL, Brunton LL, Schnaitman TC, Rebhun LI, Gilman AG. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate and alteration of Chinese hamster ovary cell morphology: a rapid, sensitive in vitro assay for the enterotoxins of Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1974;10:320–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.2.320-327.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donta ST, Moon HW, Whipp SC. Detection of heat-labile Escherichia coli enterotoxin with the use of adrenal cells in tissue culture. Science. 1974;183:334–336. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4122.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghosal A, Chatterjee NS, Chou T, Said HM. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection and intestinal thiamin uptake: studies with intestinal epithelial Caco-2 monolayers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C1185–C1191. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00276.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mann EA, Jump ML, Wu J, Yee E, Giannella RA. Mice lacking the guanylyl cyclase C receptor are resistant to STa-induced intestinal secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:463–466. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulz S, Lopez MJ, Kuhn M, Garbers DL. Disruption of the guanylyl cyclase-C gene leads to a paradoxical phenotype of viable but heat-stable enterotoxin-resistant mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1590–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI119683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schulz S, Green CK, Yuen PS, Garbers DL. Guanylyl cyclase is a heat-stable enterotoxin receptor. Cell. 1990;63:941–948. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mishra V, Goel R, Visweswariah SS. The regulatory role of the kinase-homology domain in receptor guanylyl cyclases nothing ‘pseudo’ about it! Biochem Soc Trans. 2018;46:1729–1742. doi: 10.1042/BST20180472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sellers ZM, Childs D, Chow JY, Smith AJ, Hogan DL, Isenberg JI, Dong H, Barrett KE, Pratha VS. Heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli stimulates a non-CFTR-mediated duodenal bicarbonate secretory pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G654–G663. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00386.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pitari GM, Lin JE, Shah FJ, Lubbe WJ, Zuzga DS, Li P, Schulz S, Waldman SA. Enterotoxin preconditioning restores calcium-sensing receptor-mediated cytostasis in colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1601–1607. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basu N, Saha S, Khan I, Ramachandra SG, Visweswariah SS. Intestinal cell proliferation and senescence are regulated by receptor guanylyl cyclase C and p21. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:581–593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.511311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiskerstrand T, Arshad N, Haukanes BI, Tronstad RR, Pham KD, Johansson S, Havik B, Tonder SL, Levy SE, Brackman D, et al. Familial diarrhea syndrome caused by an activating GUCY2C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1586–1595. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muller T, Rasool I, Heinz-Erian P, Mildenberger E, Hulstrunk C, Muller A, Michaud L, Koot BG, Ballauff A, Vodopiutz J, et al. Congenital secretory diarrhoea caused by activating germline mutations in GUCY2C. Gut. 2016;65:1306–1313. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mortality & Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, allcause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peterson JW, Molina NC, Houston CW, Fader RC. Elevated cAMP in intestinal epithelial cells during experimental cholera and salmonellosis. Toxicon. 1983;21:761–775. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(83)90065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prasad R, Chopra AK, Peterson JW, Pericas R, Houston CW. Biological and immunological characterization of a cloned cholera toxin-like enterotoxin from Salmonella Typhimurium. Microb Pathog. 1990;9:315–329. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murray MJ. Enterotoxin activity of a Salmonella Typhimurium of equine origin in vivo in rabbits and the effect of Salmonella culture lysates and cholera toxin on equine colonic mucosa in vitro . Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:769–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duebbert IE, Peterson JW. Enterotoxin-induced fluid accumulation during experimental salmonellosis and cholera: involvement of prostaglandin synthesis by intestinal cells. Toxicon. 1985;23:157–172. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(85)90118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giannella RA, Gots RE, Charney AN, Greenough WB, 3rd, Formal SB. Pathogenesis of Salmonella-mediated intestinal fluid secretion. Activation of adenylate cyclase and inhibition by indomethacin. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:1238–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kao DJ, Saeedi BJ, Kitzenberg D, Burney KM, Dobrinskikh E, Battista KD, Vazquez-Torres A, Colgan SP, Kominsky DJ. Intestinal epithelial ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) regulates intestinal colonization and infection by nontyphoidal Salmonella. Infect Immun. 2017;85:e01022–16. doi: 10.1128/IAi01022-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kolachala VL, Bajaj R, Chalasani M, Sitaraman SV. Purinergic receptors in gastrointestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G401–G410. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00454.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sitaraman SV, Merlin D, Wang L, Wong M, Gewirtz AT, Si-Tahar M, Madara JL. Neutrophil-epithelial crosstalk at the intestinal lumenal surface mediated by reciprocal secretion of adenosine and IL-6. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:861–869. doi: 10.1172/JCI11783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crane JK, Olson RA, Jones HM, Duffey ME. Release of ATP during host cell killing by enteropathogenic E. coli and its role as a secretory mediator. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G74–G86. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00484.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE. Enteroinvasive bacteria alter barrier and transport properties of human intestinal epithelium: role of iNOS and COX-2. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1070–1087. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zaki MH, Fujii S, Okamoto T, Islam S, Khan S, Ahmed KA, Sawa T, Akaike T. Cytoprotective function of heme oxygenase 1 induced by a nitrated cyclic nucleotide formed during murine salmonellosis. J Immunol. 2009;182:3746–3756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mann EA, Harmel-Laws E, Cohen MB, Steinbrecher KA. Guanylate cyclase C limits systemic dissemination of a murine enteric pathogen. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharma A, Herekar AA, Bhagatwala J, Rao SS. Profile of plecanatide in the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation: design, development, and place in therapy. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:31. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S145668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gagliani N, Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Flavell RA. Inflammasomes and intestinal homeostasis: regulating and connecting infection, inflammation and the microbiota. Int Immunol. 2014;26:495–499. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxu066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eldridge MJ, Shenoy AR. Antimicrobial inflammasomes: unified signalling against diverse bacterial pathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Broz P, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Munoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martinez-Colon G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Nunez G. K(+)efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38:1142–5115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di A, Xiong S, Ye Z, Malireddi RKS, Kometani S, Zhong M, Mittal M, Hong Z, Kanneganti TD, Rehman J, et al. The TWIK2 potassium efflux channel in macrophages mediates NLRP3 inflammasome-induced inflammation. Immunity. 2018;49:56–65.:e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Yu JW, Datta P, Miller B, Jankowski W, Rosenberg S, Zhang J, Alnemri ES. The pyroptosome: a supramolecular assembly of ASC dimers mediating inflammatory cell death via caspase-1 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1590–1604. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gulbransen BD, Bashashati M, Hirota SA, Gui X, Roberts JA, MacDonald JA, Muruve DA, McKay DM, Beck PL, Mawe GM, et al. Activation of neuronal P2X7 receptor-pannexin-1 mediates death of enteric neurons during colitis. Nat Med. 2012;18:600–604. doi: 10.1038/nm.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Neves AR, Castelo-Branco MT, Figliuolo VR, Bernardazzi C, Buongusto F, Yoshimoto A, Nanini HF, Coutinho CM, Carneiro AJ, Coutinho-Silva R, et al. Overexpression of ATP-activated P2X7 receptors in the intestinal mucosa is implicated in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:444–457. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000441201.10454.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eser A, Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, Vogelsang H, Braddock M, Persson T, Reinisch W. Safety and efficacy of an oral inhibitor of the purinergic receptor P2X7 in adult patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase IIa study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2247–2253. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burnstock G, Jacobson KA, Christofi FL. Purinergic drug targets for gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2017;37:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meixenberger K, Pache F, Eitel J, Schmeck B, Hippenstiel S, Slevogt H, N’Guessan P, Witzenrath M, Netea MG, Chakraborty T, et al. Listeria monocytogenes-infected human peripheral blood mononuclear cells produce IL-1beta, depending on listeriolysin O and NLRP3. J Immunol. 2010;184:922–930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Queen J, Agarwal S, Dolores JS, Stehlik C, Satchell KJ. Mechanisms of inflammasome activation by Vibrio cholerae secreted toxins vary with strain biotype. Infect Immun. 2015;83:2496–2506. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02461-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang X, Cheng Y, Xiong Y, Ye C, Zheng H, Sun H, Zhao H, Ren Z, Xu J. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli specific enterohemolysin induced IL-1beta in human macrophages and EHEC-induced IL-1beta required activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goddard PJ, Sanchez-Garrido J, Slater SL, Kalyan M, Ruano-Gallego D, Marches O, Fernandez LA, Frankel G, Shenoy AR. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli stimulates effector-driven rapid caspase-4 activation in human macrophages. Cell Rep. 2019;27:1008–1017.:e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fisch D, Bando H, Clough B, Hornung V, Yamamoto M, Shenoy AR, Frickel EM. Human GBP1 is a microbe-specific gatekeeper of macrophage apoptosis and pyroptosis. EMBO J. 2019;38:e100926. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lopez-Castejon G, Pelegrin P. Current status of inflammasome blockers as anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:995–1007. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.690032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Green JP, Yu S, Martin-Sanchez F, Pelegrin P, Lopez-Castejon G, Lawrence CB, Brough D. Chloride regulates dynamic NLRP3-dependent ASC oligomerization and inflammasome priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E9371–E9380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812744115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoglund P, Haila S, Socha J, Tomaszewski L, Saarialho-Kere U, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Airola K, Holmberg C, de la Chapelle A, Kere J. Mutations of the Down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) gene cause congenital chloride diarrhoea. Nat Genet. 1996;14:316–319. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wedenoja S, Pekansaari E, Hoglund P, Makela S, Holmberg C, Kere J. Update on SLC26A3 mutations in congenital chloride diarrhea. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:715–722. doi: 10.1002/humu.21498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tang T, Lang X, Xu C, Wang X, Gong T, Yang Y, Cui J, Bai L, Wang J, Jiang W, et al. CLICs-dependent chloride efflux is an essential and proximal upstream event for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun. 2017;8:202. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00227-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee GS, Subramanian N, Kim AI, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R, Sacks DB, Germain RN, Kastner DL, Chae JJ. The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature. 2012;492:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rossol M, Pierer M, Raulien N, Quandt D, Meusch U, Rothe K, Schubert K, Schoneberg T, Schaefer M, Krugel U, et al. Extracellular Ca2+ is a danger signal activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through G protein-coupled calcium sensing receptors. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1329. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Compan V, Baroja-Mazo A, Lopez-Castejon G, Gomez AI, Martinez CM, Angosto D, Montero MT, Herranz AS, Bazan E, Reimers D, et al. Cell volume regulation modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2012;37:487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhong Z, Zhai Y, Liang S, Mori Y, Han R, Sutterwala FS, Qiao L. TRPM2 links oxidative stress to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1611. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maenz DD, Gabriel SE, Forsyth GW. Calcium transport affinity, ion competition and cholera toxin effects on cytosolic Ca concentration. J Membr Biol. 1987;96:243–249. doi: 10.1007/BF01869306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taylor CW. Regulation of IP3 receptors by cyclic AMP. Cell Calcium. 2017;63:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ouyang X, Ghani A, Malik A, Wilder T, Colegio OR, Flavell RA, Cronstein BN, Mehal WZ. Adenosine is required for sustained inflammasome activation via the A(2)A receptor and the HIF-1alpha pathway. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2909. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mao K, Chen S, Chen M, Ma Y, Wang Y, Huang B, He Z, Zeng Y, Hu Y, Sun S, et al. Nitric oxide suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation and protects against LPS-induced septic shock. Cell Res. 2013;23:201–212. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ellis CN, LaRocque RC, Uddin T, Krastins B, Mayo-Smith LM, Sarracino D, Karlsson EK, Rahman A, Shirin T, Bhuiyan TR, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis reveals activation of mucosal innate immune signaling pathways during cholera. Infect Immun. 2015;83:1089–1103. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02765-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karlsson EK, Harris JB, Tabrizi S, Rahman A, Shlyakhter I, Patterson N, O’Dushlaine C, Schaffner SF, Gupta S, Chowdhury F, et al. Natural selection in a bangladeshi population from the choleraendemic ganges river delta. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:192ra86. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, Newton K, Qu Y, Liu J, Heldens S, et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Loss H, Aschenbach JR, Tedin K, Ebner F, Lodemann U. The inflammatory response to enterotoxigenic E. coli and probiotic E. faecium in a coculture model of porcine intestinal epithelial and dendritic cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/9368295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miao EA, Rajan JV. Salmonella and caspase-1: a complex interplay of detection and evasion. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:85. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Stecher B. The roles of inflammation, nutrient availability and the commensal microbiota in enteric pathogen infection. Microbiol Spectr 3. 2015 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MBP-0008-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vogt SL, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota-mediated protection against diarrheal infections. J Travel Med. 2017;24:S39–S43. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taw086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Keely S, Kelly CJ, Weissmueller T, Burgess A, Wagner BD, Robertson CE, Harris JK, Colgan SP. Activated fluid transport regulates bacterial-epithelial interactions and significantly shifts the murine colonic microbiome. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:250–260. doi: 10.4161/gmic.20529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tronstad RR, Kummen M, Holm K, von Volkmann HL, Anmarkrud JA, Høivik ML, Moum B, Gilja OH, Hausken T, Baines J. Guanylate cyclase c activation shapes the intestinal microbiota in patients with familial diarrhea and increased susceptibility for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1752–1761. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Miettinen M, Pietiläa TE, Kekkonen RA, Kankainen M, Latvala S, Pirhonen J, Österlund P, Korpela R, Julkunen I. Nonpathogenic Lactobacillus rhamnosus activates the inflammasome and antiviral responses in human macrophages. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:510–522. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]