Abstract

Human astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas are defined by mutations of the metabolic enzymes isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 or 2, resulting in the production of the abnormal metabolite D-2 hydroxyglutarate. Here, we studied the effect of mutant IDH on cell proliferation and apoptosis in a glioma mouse model. Tumors were generated by inactivating Pten and p53 in forebrain progenitors and compared with tumors additionally expressing the Idh1 R132H mutation. Idh-mutant cells proliferated less in vitro and mice with Idh-mutant tumors survived significantly longer compared to Idh-wildtype mice. Comparison of micro-RNA and RNA expression profiles of Idh-wildtype and Idh-mutant cells and tumors revealed miR183 was significantly upregulated in IDH-mutant cells. Idh-mutant cells were more sensitive to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, resulting in increased apoptosis and thus reduced cell proliferation and survival. This was mediated by the interaction of miR183 with the 5’ untranslated region of Semaphorin3E, downregulating its function as an apoptosis suppressor. In conclusion, we show that mutant Idh1 delays tumorigenesis, sensitises tumour cells to ER stress and apoptosis. This may open opportunities for drug treatments targeting the miR183-semaphorin axis.

Keywords: Brain tumours, Isocitrate dehydrogenase, Cre lox system, Glioblastoma, Endoplasmic reticulum stress

Introduction

The grading of gliomas, previously largely based on histological criteria, has over the last years been complemented with diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers (1). The discovery of “neomorphic” mutations in the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) genes 1 or 2 (2) has provided a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of oligodendrogliomas and astrocytomas. This delineates them from IDH-wildtype gliomas which carry a poorer prognosis (3,4). IDH-wild-type and IDH-mutant glioblastomas are histologically similar but molecularly distinct, and differ not only by their IDH mutation status. Therefore, a direct comparison and evaluation of the effects of mutant IDH is possible only in experimental settings. Cells expressing mutant IDH1/2 catalyse α-ketoglutarate into the D-enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate (D2HG), which causes the DNA hypermethylator phenotype (5). Developmental expression of mutant Idh (R132H) in the mouse brain causes early postnatal lethal brain haemorrhages, possibly due to stabilised hypoxic-inducible hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) -1α, (6), impaired collagen maturation and basement membrane structure and function. This lethal phenotype precluded the study of neoplastic effects of mutant Idh. A study of inducible Nestin-CreER(T2)-mediated expression of Idh1 R132H in adult neural progenitors of the subventricular zone (SVZ) circumvented embryonic lethality. These mice showed an enlarged SVZ with increased numbers of quiescent neural stem cells and their progeny but did not form brain tumours. Instead they developed hydrocephalus, a sign of brain atrophy (7). Instead, the growth-delaying effects of high intracellular levels of R(–)-2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) (8), appear contradictory to the tumour-promoting role of IDH1 R132H. The combination of mutant Idh1, Atrx and Pten in an experimental model formed gliomas, but has not addressed the role of Idh1 R132H itself in neoplastic neural progenitor formation (9). A role of mutant Idh1 in suppressing immune infiltrating cells in experimental gliomas has been shown in an RCAS/tva model (10).

We hypothesise that mutant IDH and the production of 2-HG induces a growth delay (8) by triggering cellular pathways that reduce proliferation or render tumour cells prone to cell death. This hypothesis was tested in mouse and cell models to selectively investigate the role of mutant Idh1 in the context of an established intrinsic brain tumour model. The Idh-mutant glioma-initiating cells and tumours corresponded well to human IDH-mutant astrocytomas and glioblastomas, producing high levels of 2-HG, and showing a proneural expression profile. We chose this approach to compare the transcriptome of Idh-wildtype and Idh-mutant tumours, and we have identified gene sets enriched for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response and the microRNA (miR) family 96-182-183, controlling Semaphorins and mediating ER stress response.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mouse studies were performed under approval and licence granted by the UK Home Office (Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986), project licence number PA79953C0, and conformed to UCL institutional and Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/arrive-guidelines). All mice were kept at the Biological Service Facility, UCL. The following published mouse strains were used: p53loxP/loxP (11); ptenloxP/loxP (12); and GLAST-cre ER(T2) (13). All mice used in this study have a reporter gene lacZloxP/loxP reporter gene in the ROSA26 locus ((Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor). Mice were genotyped as described (14).

The Idh1 PM/Flex mouse (B6N-Idh1tm1(R132H)Avd/N) containing a conditional point mutation (R132H) in Idh1 exon 3 was generated in the Mouse Clinical Institute (MCI, Illkirch, France) using Flex transgenesis technology. The procedure of the conditional knock-in of the Idh1 R132H (395-396 GA>AT) into the murine Idh1 locus under the endogenous promoter is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Primers for Idh1 genotyping can be found in supplementary table 1.

Retrovirus production and injection

The PDGFB-Ires-Cre retroviral construct was kindly provided by Prof. Peter Canoll (Columbia University Medical Center, USA,) and the use of this retrovirus to generate gliomas have been described previously (15). Retrovirus was transfected into Platinum E cells using Fugene (Promega) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The Platinum E cells were kindly provided by Prof. Verdon Taylor (University of Basel, Switzerland). Supernatant containing retrovirus was concentrated using Retro-X concentrator (Clontech, PT5063-2). Just before injection, polybrene (final concentration 8 μg/ml) was supplemented to retrovirus solution to facility infection rates. 1 μl of retrovirus solution was injected to the subventricular zone of neonatal mice (age P0-P1).

Tunicamycin administration in vivo and imaging

Tunicamycin injection method has been described in detail previously (16). Briefly, tunicamycin (New England Biolabs NEB, #12819S) was first dissolved in DMSO to make a 10 μg/μl stock solution, and then diluted to 0.3 μg/μl with 150 mM Glucose for injection. Each mouse received 3 μg/g body weight (10 μl/g) tunicamycin twice by subcutaneous injection. Two such doses were administered with an interval of two hours. Mice were sacrificed 24h after the second tunicamycin injection. For in vivo comparison of ER-stress induced apoptosis, Annexin-vivo 750 (Perkin Elmer NEV11053) fluorescent imaging agent was administered intravenously 2 hours prior to imaging on an IVIS III preclinical imaging system. Automatic unmixing as per manufacturers guidelines was performed to separate Annexin-vivo 750 signal from background autofluorescence.

RNA and microRNA sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed at UCL Genomics (UCL Institute of Child Health). The library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis were described previously (17). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) were performed using datasets downloaded from the Broad Institute (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) as described previously (18). miRNA sequencing was performed by Exiqon (17). miRNA sequencing libraries were prepared from 500 ng total RNA using NEBNEXT library generation kit (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s protocols. Adaptors were ligated to each individual RNA sample, allowing amplification of RNAs with specific primers using RT-PCR for 15 cycles. After amplification libraries were purified QiaQuick (Qiagen) columns and cDNA with approximate size of 142nt (120nt plus ~22nt miRNAs) were selected on a LabChip XT (Perkin Elmer). Samples were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 500 system (Illumina). Sequencing data were mapped to mouse annotated miRNA (miRBase 20), and normalised using trimmed mean of M-value method (19). Differential expression analysis was performed on R using EdgeR package (Bioconductor). RNA and miRNA sequencing data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under GSE119741 and GSE119740, respectively.

Cell culture

Freshly prepared murine neural stem cells (NSC) or brain tumour initiating cells (BTIC) derived from in vitro recombined NSC were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium, supplemented with B27 (2%), penicillin/streptomycin (1%), EGF (20 ng/ml) and FGF (20ng/ml). Cell proliferation assay was performed in an IncuCyte interval image capture chamber (Essen bioscience, US). Short oligonucleotides including siRNA, miRNA mimics/inhibitors and negative controls (Supplementary table 1) were transfected into cells with TransIT-X2 reagent (Mirus), and plasmids were transfected with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. No established or externally acquired cell lines were used.

D2HG quantification

The cellular level of D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D2HG) were assessed using an enzymatic assay described previously (20). Briefly, cells were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer, which contains 0.1% NP40 (Calbiochem, 492016), 135 mM NaCl and 45 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Protein amount used for normalization was determined using BCA assay (Thermo, 23225). Commercial D2HG (Sigma, #H8378) with a range of concentrations (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 25, 50 and 100μM) was set as standards. Samples and standards were deproteinized using a deproteinization kit (Biovision, K808-200) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The deproteinized samples and standards in triplicate were incubated with assay solution, which contains 100 mM of pH 8.0 HEPES (Applichem, H0887), 100 uM NAD+ (Applichem, #A1124), 5 uM resazurin (Applichem, #A2830), 0.01U/ml diaphorase (MP Biomedicals, #150843) and 1 μg/ml D-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (HGDH, kindly provided by Prof. A. von Deimling), at room temperature for 30 min in black 96-well plate (BRANDTech, #781608). The fluorescent intensity (FI) was detected using FLUOstar microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Germany) with excitation at 540 nm and emission at 610 nm. The standard curve was created using 4-parameter fit method in Omega Data Analysis software to determine the D2HG concentration in each sample.

Caspase-3/7 activity assay

Cells were lysed (#7018; Cell Signaling) and, 5-10 μg of the lysate was mixed with 150 μl protease assay buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, and 2 mM DTT, and 20 μM fluorogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC (#556449, BD Pharmingen), followed by a 2-hour incubation at 37°C in a black 96-well plate. Fluorescence intensity was determined (excitation, 360 nm; emission, 460 nm) with a FLUOstar Omega plate reader (BMG labtech, Germany).

PCR and RT-qRCR

Primers used for PCR or RT-qPCR were listed in Supplementary table 1. The use of Xbp1 splicing primers were reported previously (21). For RT-qPCR, cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid RT kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), and SYBR green was used as reporter. GAPDH levels were used as normalization and fold changes were calculated using the 2ΔΔCt method on DataAssist 3.1 software (Thermo Fisher). PCR analysis of the Idh and wild type alleles on brain tumours was performed on genomic DNA extracted from different tumours, microdissected from paraffin sections as described previously (14).

Immunoblots

Cell lysate for immunoblots was collected with RIPA buffer (Thermo, 89900) containing protease/phosphatase inhibitor (Cell Signaling, 5872). The protein concentration was assessed using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo, 23225). Equal amount of protein from each sample was separated using 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare, 10600023). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 hour at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibody conjugated with HRP incubation at room temperature for 1 hour, and signal was detected with ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Kit (GE Healthcare, RPN2232). Antibody information is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Luciferase assay

The 3’UTR of Sema3E (174bp) containing wildtype or mutant miR183-5p binding site were synthesized commercially (GeneArt, Invitrogen). The 3’UTR fragment was inserted to pMIRREPORT luciferase vector between HindIII and SpeI restriction sites. Luciferase signal was measured 48h post-transfection using Dual-Light kit (Applied Biosystems).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

Brains were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, cut into 3μm sections and processed for haematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. Staining was carried out using a Ventana Discovery automated staining instruments (ROCHE Ventana Medical Systems) following the manufacturer’s guidelines, using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin complex and diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 1

Image analysis

Histological slides were digitised on LEICA SCN400 scanner (LEICA, Milton Keynes UK), or Hamamatsu S360 (Hamamatsu Welwyn Garden City, UK) at 40x magnification, and images were captured from the LECIA Slidepath slide management software. Digital image analysis was performed on Definiens Developer 2.4 (Munich, Germany) as previously published (17,22) or on the open source software QuPath (23) Version 0.2m2.

Human tissue resources

The use of human tissue samples was licensed by the NRES, University College London Hospitals NRES license for using human tissue samples: Project ref 08/0077 (S.B.). The storage of human tissue is licensed by the Human Tissue Authority, UK, License #12054 to SB. Glioma tissue blocks and associated clinical and molecular information were from the archives of the NHNN.

Results

Expression of Idh1 R132H increases intracellular D2HG levels and inhibits cell proliferation

To study the pathological function of mutant IDH1 R132 in tumour initiation and propagation, we generated a knock-in mouse model of Idh1LoxP(R132H) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1). Expression of Cre replaces exon 3 of the Idh1 gene with the mutant exon 3 (Fig. 1B) and the resulting Idh1 R132H can be detected with the mutation-specific antibody H09 (24) (Fig. 1C). Idh1LoxP(R132H) knock-in mice were crossed with wildtype, or p53LoxP/LoxP, or PtenLoxP/LoxP; p53LoxP/LoxP mice, resulting in Idh1LoxP(R132H)/+; or Idh1LoxP(R132H)/+; p53LoxP/LoxP; or Idh1LoxP(R132H)/+; PtenLoxP/LoxP; p53LoxP/LoxP mice, and controls, respectively (in short “p53”, “Pten/p53”, and “Idh/p53”, “Idh/Pten/p53”). All mice were kept in a ROSA26lox/lox reporter (Gt(ROSA)26Sorm1Sor) background (25) to identify recombined cells. Mutant IDH1 catalyses α-ketoglutarate into D-2-hydroxyglutarate, which accumulates in Idh-mutant tumours (7,20,26), and in our model (Fig. 1D), which replicates the metabolic changes of human IDH-mutant tumours.

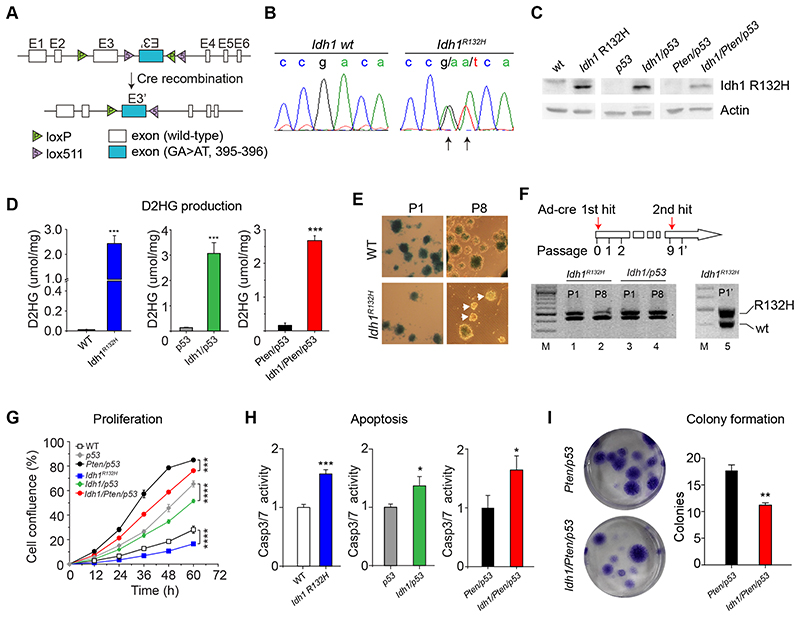

Figure 1. characterisation of Idh-mutant neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPC) and brain tumor initiating cells (BTIC).

A: targeting strategy of conditional mutant mice carrying an inducible Idh1 R132H mutation. B: demonstration of the Idh mutation in NSPC and BTIC. C, immunoblotting with antibody DIA-H09 detects Idh1 R132H in lysate of mutant cells but not in controls. D, D2HG production in Idh-mutant NSPC and BTIC. E & F, NSPC cultures of recombined ROSA26lox/lox (blue). NPSC maintain recombined neurospheres during multiple passages (WT; P1, P8), whilst IDH-mutant NSPC become gradually overgrown by the expanding non-recombinant moiety (IDH1R132H, P1, P8). F, PCR analysis of IDH-mutant cultures show a reduction of heterozygous IDH-mutant cells in the course of 8 passages. Lane 1, Idh1R132H/+ P1; lane 2, IDH1R132H/+ P8 with reduced Idh-mutant moiety; lane 3,4, Idh1/p53 BTIC P1 and P8 retain the recombined allele due to expansion of BTIC. Lane 5, repeat recombination of P8 IDH1R132H/+ NPSC, demonstrating that cells did not lose the allele but were overgrown by non-recombined IDH1lox(R132H)/+ cells. G, Idh R132H inhibits proliferation of NPSC and BTIC. Live cell imaging shows slower growth of Idh R132H mutant NPSC and BTIC compared to IDH-wildtype controls (n=3). H, increased apoptosis IDH R132H mutant NPSC or BTIC compared to IDH-wildtype counterparts (n=3). I, Idh1 R132H mutation inhibits cell survival. Colony formation assay was performed on Idh1/Pten/p53 cells Pten/p53 controls (n=3).

To establish the effect of Idh1 R132H on naïve neural stem cells we derived neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPC) from the murine subventricular zone (SVZ) and induced Idh1 R132 expression with adeno-cre as described (14) (Fig. 1C). Unexpectedly, non-recombined, β-galactosidase negative (Idh-wildtype) cells or spheres grew faster than the Idh-mutant moiety over multiple passages (Fig. 1E). Repeat transfection with adeno-cre “restored” a population of β-galactosidase positive, Idh-mutant cells, indicating that Idh-wildtype cells had a growth advantage over Idh-mutant cells (Fig. 1F). The growth reduction of Idh-mutant cells was overcompensated by the additional homozygous deletion of p53, giving Idh1/p53 cells a growth advantage over the wildtype cells (Fig. 1G). All Idh1 mutant cultures had consistently a reduced proliferation compared to wildtype counterparts (Idh1 vs. wt, Idh1/p53 vs. p53, and Idh1/Pten/p53 vs. Pten/p53; Fig. 1G). A Caspase 3/7 activity assay (Fig. 1h) shows 1.5-fold increase (p<0.05) of apoptosis in Idh-mutant cell cultures. The formation of colonies, a measure of self-renewal, was significantly reduced (p<0.01) in Idh/Pten/p53 cultures compared to Pten/p53 controls (Fig. 1I). In conclusion, the introduction of the Idh1 R132H into naïve neural stem cells reduces cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in vitro.

Idh1 R132H is not sufficient for tumorigenesis, delays tumor growth in vivo and is associated with increased apoptosis

We assessed the effect of Idh1 R132H on stem cell growth and tumorigenesis in vivo by crossing Idh1LoxP(R132H) mice with GLAST-cre ER(T2) (13) and ROSA26lox/lox reporter mice. Tamoxifen was administered systemically (Fig. 2A) and led to Cre expression in the SVZ stem cell population (27) (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. 2). Five weeks after Cre activation, the proliferation in the SVZ was determined by Ki67 labelling. There was overall a smaller number of recombined cells in the SVZ and the subcallosal zone of GLAST-cre ER(T2); Idh1LoxP(R132H) mice compared to controls, but proportionally there was still a significant reduction of Ki-67 labelled nuclei in IDH-mutant SVZ-derived cells (Fig. 2C). Long-term observation of tamoxifen-induced GLAST-cre ER(T2); ROSA26lox/lox; Idh1LoxP(R132H) mice or of adeno-cre injected ROSA2dox/ìox; Idh1LoxP(R132H) mice showed populations of recombined SVZ stem/progenitor cells but no tumors (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. 3).

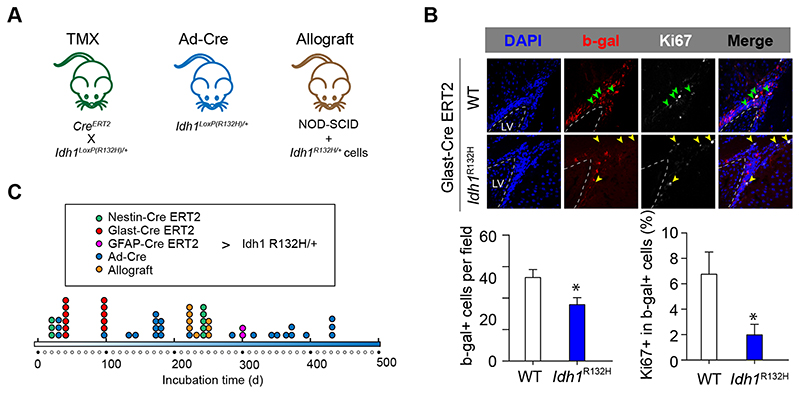

Figure 2. Idh1 R132H is not sufficient for tumorigenesis and reduces proliferation of subventricular zone stem/progenitor cells in vivo .

A, three model systems were used to establish the tumor-initiating role of Idh1 R132H: Tamoxifen-induced recombination in GLAST-cre ERT(2); Idh1R132HloX+ mice (13,27). Intraventricular adeno-cre injection of Idh1R132Hlox/+ mice (14), and striatum allografts into NOD-SCID mice. B, significant reduction of the number and proliferation of recombined cells (ROSA26lox/lox reporter, β-gal-expressing) in the IDH-mutant NSPC population (4 mice) compared to controls (3 mice). C, Time points of brain analysis. No tumors or clusters of neoplastic cells were identified at up to 430 days.

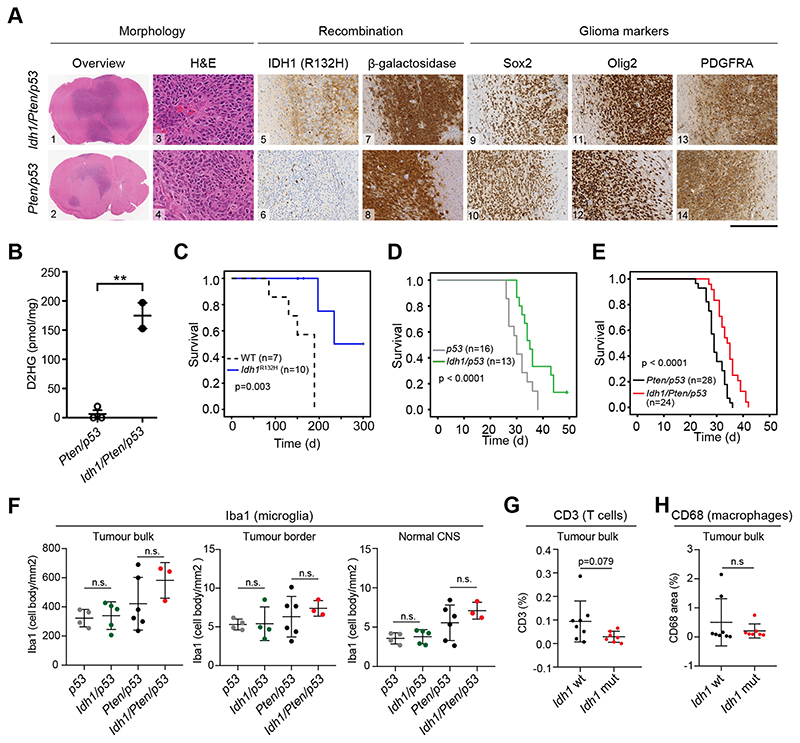

To confirm the tumor growth-delaying effects of mutant Idh1, we generated Idh/p53, and Idh/Pten/p53 mice. Idh1LoxP(R132H) mice and wildtype mice served as controls. Intraventricular injection of a retrovirus expressing PDGF-IRES-Cre into new-born Idh-wildtype or Idh-mutant mice induced glioblastomas (15) with >90% incidence (Fig. 3A and supplementary table 1) within 30-50 days. Tumours of Idh mutant mice contained high levels of D2HG, consistent with findings in human IDH-mutant astrocytomas (Fig 3B). Whilst controls with an Idh mutation alone or no mutation developed tumours with long latencies (Fig 3C), p53 mice (n=16) developed tumors already at 30 days (SEM ± 0.93d). The additional expression of mutant Idh1 (n=13) delayed tumor formation to 35 days (SEM ± 1.16d) (p<0.0001) (Fig. 3D and supplementary table 1,). Further deletion of both Pten alleles led to an acceleration of tumorigenesis in both, Pten/p53 and Idh/Pten/p53 mice and again, the Idh-wildtype group (Pten/p53, n=28), survived shorter (29d, SEM ± 0.66d) than the Idh-mutant group (Idh/Pten/p53, n=24, 34d, SEM ± 1.27d) (Fig 3E). Idh-mutant and wildtype tumors showed no difference in neural and glial marker expression (Fig. 3A, supplementary Fig. 4A, B), or tumor microenvironment (microglia, T cells, macrophages; Fig. 3F-H). Neonatal ROSA2dox/lox reporter mice injected with PDGF-IRES-Cre retrovirus (wt or Idh) developed small infiltrative gliomas after more than 150 days (wt, n=6, Idh, n=10) (Fig 3C, Supplementary Fig. 4C), as previously shown (28), again confirming growth-delaying role of mutant Idh1. The Idh mutation in these tumours was confirmed on DNA (supplementary Fig. 4D and protein level (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Figure 4A-C). In conclusion, we show here that mutant Idh1 delays tumorigenesis. Adeno-cre induced tumors (14) in Pten/p53 and Idh/Pten/p53 mice again were morphologically indistinguishable (supplementary Fig. 4A) but occurred with lower incidence (Idh/Pten/p53, 3/46 and Pten/p53 group, 6/57). In keeping, Idh1/Pten/p53 or Pten/p53 cells grafted into the striatum of NOD-SCID showed a difference with lower tumor incidence in Idh1/Pten/p53 transplants (p=0.047, supplementary Fig. 4E).

Figure 3. Idh1 R132H mutation delays gliomagenesis.

A: Tumors show morphological features of high-grade gliomas with microvascular proliferation and necrosis. Idh R132H is detected in Idh/Pten/p53 but not in Pten/p53, whilst the β-galactosidase reporter is expressed in both genotypes. Markers of progenitors (Sox2, Olig2 and PDGFRA) are strongly expressed in both genotypes. B: D2HG production in IDH-mutant (n=2) but not in IDH-wildtype (n=3) tumors confirms catalytically active Idh1 R132H. C, PDGFR-induced tumors are delayed in IDH-mutant mice (p=0.003). D, rapid induction of brain tumors in p53 and Idh/p53, and E, in Idh/Pten/p53 and Pten/p53 mice, with significant delay of formation of IDH-mutant tumors (p<0.0001). No effect of mutant IDH on microglia (F), T cells (G) or macrophages (H).

Idh1 R132H mutant BTIC are sensitive to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress

To understand how mutant Idh1 reduces cell growth and promotes apoptosis, we performed RNA sequencing on Idh1/Pten/p53 and Pten/p53 brain tumor-initiating cells (BTIC). Gene set enrichment analysis showed significant enrichment of ER response and ER stress-induced apoptosis pathways in Idh1/Pten/p53 cells (Fig. 4A). Treatment of Idh1-mutant cells with ER stress inducers tunicamycin (16) or thapsigargin (29) increased cell death in Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC (Fig. 4B). To explore if this ER stress sensitisation was mediated by D2HG, we treated Idh-mutant cells with AGI-5198, an inhibitor of the catalytic pocket of Idh1 R132 (30), and conversely, Idh1 wildtype cells with D2HG, and then exposed them to tunicamycin and thapsigargin. Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC showed 4-fold increase of apoptosis after tunicamycin treatment, compared to 1.5 fold in Pten/p53 BTIC. Inhibition with AGI-5198 prevented ER stress-induced apoptosis in Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC (Fig. 4C), and in turn, treatment of Pten/p53 BTIC with 10mg/ml (D)-2-Hydroxyglutaric acid disodium salt significantly sensitised Pten/p53 BTIC to ER stress (Fig. 4C) whilst treatment with AGI-5198 or D2HG alone, without tunicamycin or thapsigargin showed no effect (Fig. 4D).

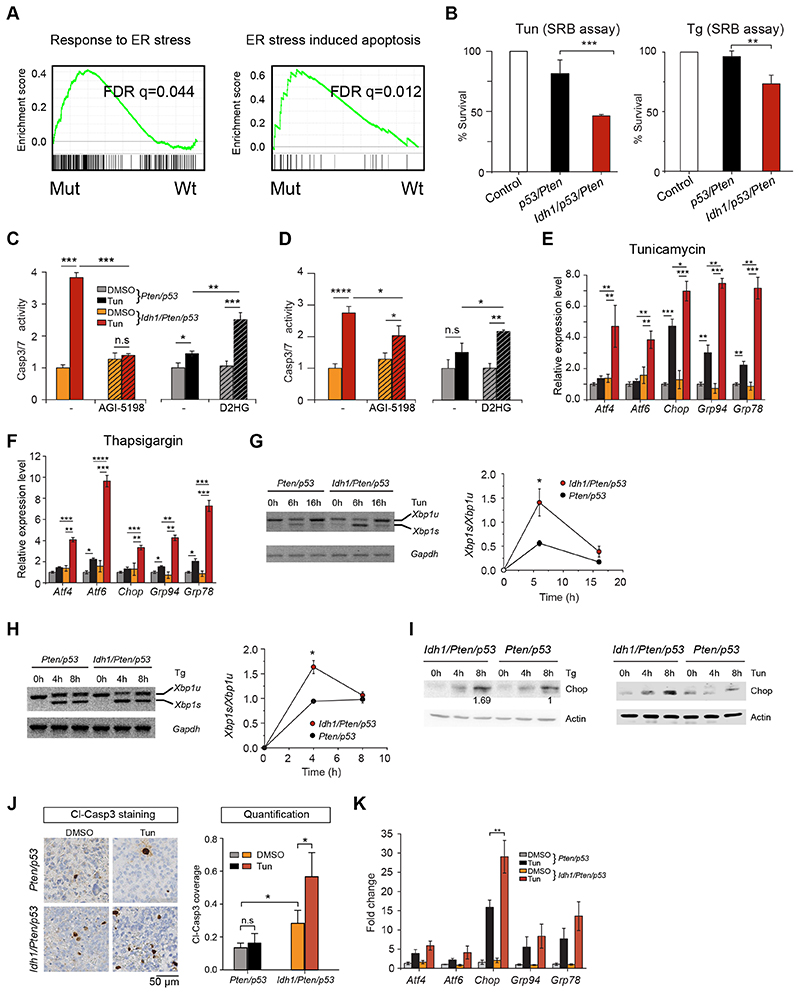

Figure 4. Idh1 R132H sensitises BTIC to endoplasmic reticulum stress and causes increased apoptosis and upregulation of UPR pathways.

A, gene set enrichment analysis of RNAseq data from Pten/p53 and Idh/Pten/p53 cells shows activation of genes related to ER stress response and ER stress-induced apoptosis. B, Sulforhodamine B (SRB) cell viability assay shows reduced survival of IDH mutant BTIC upon tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml, 48h) or Thapsigargan (0.5 μM, 24h). C, increased apoptosis in tunicamycin treated IDH-mutant Pten/p53 BTIC (red bar) and suppression of apoptosis by treatment with competitive inhibitor AGI 5198 (hatched red bar). Conversely there is induction of apoptosis by treatment of Pten/p53 mutant BTIC with D2HG (hatched dark grey bar); 3 independent experiments. D, similar results in BTIC treated with thapsigargin. E, significant Upregulation of UPR pathway genes in Idh-mutant cells. Chop, Grp94 and Grp78 are upregulated also in Pten/53 cells, but significantly more in IDH mutant counterparts (3 independent experiments). F, significant upregulation of UPR pathway genes in Idh-mutant BTIC after treatment with thapsigargin (3 independent experiments). G, XBP1 splice products are increased in Idh/Pten/p53 cells upon tunicamycin (G) or thapsigargin (H) treatment (3 independent experiments). I, Upregulation of Chop over time is increased in Idh1/Pten/p53 mutant cells. J, mice with brain tumors were injected with DMSO or tunicamycin and called one day later (Idh1/Pten/p53 DMSO: n=8; Idh1/Pten/p53 Tun: n=5; Pten/p53 DMSO: n=6; Pten/p53 Tun: n=4. Immunostaining of tumors for cleaved Caspase 3 shows significantly more apoptosis in IDH-mutant tumors (n=8; controls n=6). K, qRT-PCR of tumor RNA shows similar results to the in vitro experiments (E), with a highly significant upregulation of Chop and a trend in upregulation of Atf4, Atf6, Grp94 and Grrp78, upon Tunicamycin treatment in vivo (n=3 per group).

Next, we analysed the activation of ER stress-triggered unfolded protein response (UPR) pathways. The UPR is mediated by three stress receptors, (i) inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endoribonuclease 1 (IRE1), (ii) protein kinase RNA (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK); and (iii) activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6) (31). ATF4 and CHOP/Ddit3 are activated downstream of PERK. Without tunicamycin or thapsigargin treatment, Idh1/Pten/p53 and Pten/p53 BTIC expressed similar levels of the downstream targets of PERK (Atf4, Chop/Ddit3), of Atf6 and its target Grp94 (Hsp90b1) and of the target of X-Box-Binding Protein 1 (XBP1), Grp78 (Hspa5 or Bip) (Fig. 4E, F), although Chop protein is undetectable at this condition. Tunicamycin or thapsigargin treatment upregulated UPR genes in Idh1/Pten/p53, but not in Pten/p53 BTIC, Fig. 4E, F). Splicing of XBP1 mRNA is a direct indicator of IRE1 pathway activation (32–34) and indeed Xbp1 splicing during ER stress is increased in tunicamycin and thapsigargin treated Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC (Fig. 4G, H). This effect was also seen in vivo in tunicamycin treated tumor-bearing mice (16). We then assessed the alteration of protein levels of UPR genes during tunicamycin and thapsigargin treatment for 8 hours, in Idh1/Pten/p53 and Pten/p53 BTIC. In both BTIC genotypes, Chop (and phosphorylated eIf2α and PERK) gradually accumulated, but at a higher rate in Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC (Fig. 4I). Protein levels of Grp78/Bip instead remained constant in both genotypes even though Grp78 transcripts were differentially expressed (Supplementary Fig. 5). In vivo treatment of tumor-bearing mice with tunicamycin showed nearly absent Caspase 3 labelled apoptotic nuclei in the DMSO treated Pten/p53 group (n=7) and rare positive nuclei in the tunicamycin treated group (n=4) with no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 4J). Instead, Idh1/Pten/p53 tumors had a higher (p<0.05) baseline Caspase 3/7 activity than Pten/p53 tumors and a significant increase of apoptosis in tunicamycin-treated Idh1/Pten/p53 tumors (p<0.05), i.e. tunicamycin sensitises Idh-mutant tumors to apoptosis in vivo (Fig. 4J, Supplementary Fig. 5C). Expression analysis of transcripts of the ER stress pathway shows upregulation of Chop transcripts in Idh1/Pten/p53 tumors compared to Pten/p53 controls (Fig. 4K). Overall, we show that the Idh1 R132H mutation sensitizes BTIC to ER stress in vitro and in vivo.

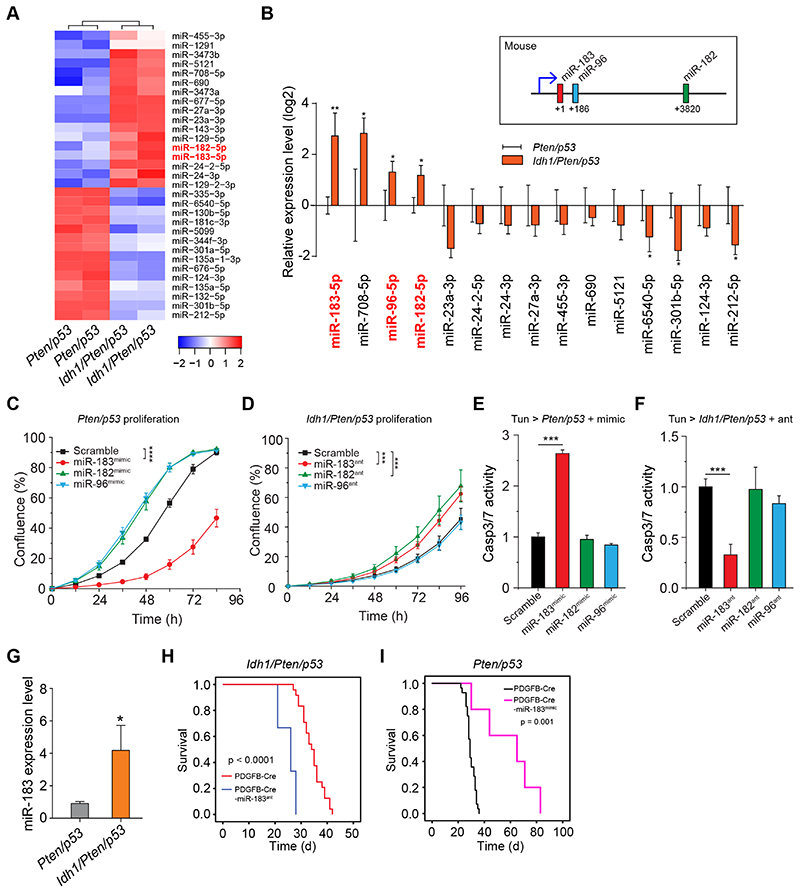

miR183 is most significantly differentially expressed between Idh-mutant and Idh-wildtype BTIC

To identify the mechanism of Idh1 R132H-mediated ER stress sensitization we compared miRNA expression profiles of Idh1/Pten/p53 and Pten/p53 BTIC. A functional connection between ER-induced UPR (ERUPR) signalling and miRNA expression has revealed mechanisms of protein homeostasis regulation, and miRNA biogenesis is regulated by the ERupr (35). We found 31 significantly differentially expressed miRNAs (DE-miRNAs, Fig. 5A, p<0.05). Validation of the top 14 DE-miRNAs RT-qPCR, identified miR183-5p as most significantly differentially regulated (Fig. 5B). miR183 is part of a miRNA cluster which comprises miR182, and miR96 (36). RT-qPCR confirmed significant upregulation of all 3 miR in Idh1/Pten/p53 cells (Fig. 5B). This was the starting point for the analysis of these microRNAs in the involvement in regulating apoptotic pathways (37).

Figure 5. Idh1 mutation upregulates expression of the miR183-182-96 cluster.

A, Heatmap of differential expression of miRNAs (DE-miRs) between Idh1/Pten/p53 and Pten/p53 BTIC. B, RT-qPCR validation of the top 15 DE-miRs confirming significant miR183-182-96 upregulation in Idh-mutant BTIC (n=3). C, functional validation of miR183-182-96 effects on Pten/p53 BTIC shows that overexpression of miR183 inhibits the proliferation of Pten/p53 BTIC (2 independent experiments, 3 replicas each), whilst miR183 antagomir increases proliferation of Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC (D) (2 independent experiments, 3 replicas each). E, expression of miR183 (red bar) but not of miR182 or miR96 mimics (green, blue bars) in Pten/p53 BTIC causes significant apoptosis during tunicamycin-induced ER stress (3 independent experiments). F, Treatment of in Idh/Pten/p53 cells only with miR183 but not miR182 or miR96 reduces tunicamycin-induced apoptosis (3 independent experiments). G, miR183 is highly expressed also in vivo in Idh/Pten/p53 tumors (n=5, controls n=4). H, I: In vivo validation of the effects of miR183 on tumor growth and overall survival by administering miR183 in the same retroviral vector with PDGF-IRES-cre. Idh/Pten/p53 mice receiving miR183 antagomir (n=3, controls n=24) showed significantly reduced survival (p<0.0001), whilst expression of miR183 mimic (n=5, controls n=28) in Pten/p53 tumors (I) results in significantly prolonged survival (p=0.001).

Regulation of ER stress response by mutant Idh1 is mediated by miR183 but not miR182 and -96

To establish the roles of miR183, miR182 and miR96 in modulating proliferation and apoptosis in Idh1/Pten/p53 and Pten/p53 BTIC we transfected them with mimics and antagomirs. Cell confluence and growth rates were determined by live cell imaging (17). Pten/p53 BTIC transfected with miR183 mimics (Fig 5C) and antagomiR183 treated Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC (Fig 5D) showed a significant growth increase compared to controls (p<0.0001), whilst transfection with miR96 or miR182 mimics (Fig. 5B, C) did not significantly change their growth rate. To investigate how miR183 sensitises cells to tunicamycin, we transfected Pten/p53 cells, in which miR183 baseline levels are low, with miR183 mimic (supplementary Fig. 6). Tunicamycin treatment of Pten/p53-miR183mımıc cells significantly increases Caspase 3/7 activity (Fig. 5E). Correspondingly, transfecting Idh/Pten/p53 cells (high miR183 base levels) with miR183 antagomir significantly reduces tunicamycin-induced cell death (p <0.001), i.e. antagonising miR183 desensitises cells to tunicamycin induced ER stress, and in this context against Idh R132H-mediated effects (Fig. 5F). Instead, miR182 and miR96 had no significant effect on cell proliferation in vitro (Fig. 5C, D) and did not modulate tunicamycin-induced ER stress in Idh1/Pten/p53 or Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC. In conclusion, we show here that miR183-mediates Idh1 mutation-associated ER stress sensitization in BTIC. Baseline expression levels of miR183 is higher in IDH mutant tumours (Fig. 5G). We have confirmed its pathobiological role in vivo by inserting miR183 or miR183 antagomir expression cassette into a PDGF-IRES-cre retroviral vector. Tumors were induced with PDGF-IRES-cre-miR183ant in Idh/Pten/p53 mice (n=3) (Figure 5H) and in Pten/p53 mice (n=5) with PDGF-IRES-cre-miR183mimic (Pten/p53-miR183mimic) (Fig. 5I). Pten/p53-miR183mimic mice (n=5; controls n=28) showed a significant delay in tumorigenesis, with an increased survival of 29 days (p =0.001), whilst Idh/Pten/p53- miR183ant mice (n=3; controls n=24) showed a significant acceleration of tumor formation with a reduction by 9 days (p<0.0001). In conclusion, miR183 mediates ER stress response in IDH-mutant BTIC in vitro and in IDH-mutant experimental gliomas in vivo.

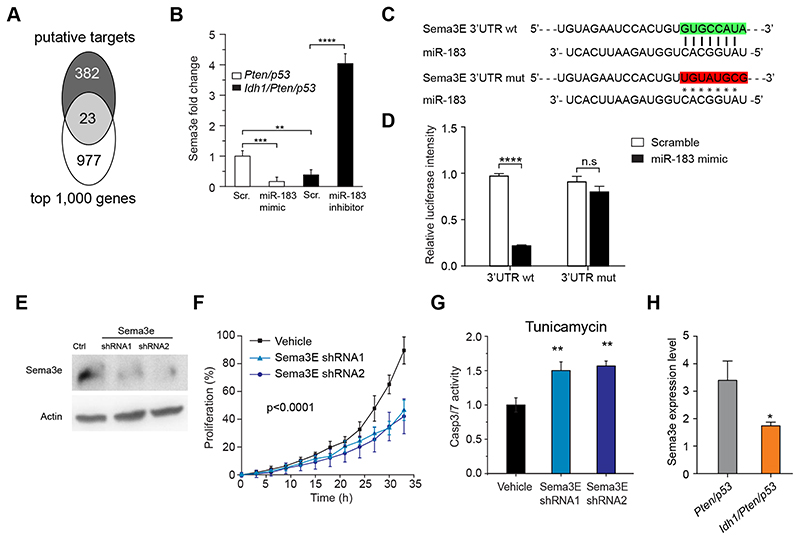

miR183 downregulates semaphorin 3E, an axonal guidance and apoptosis suppressor protein

To identify the target binding sites of miR183 with relevance to apoptosis, we performed a TargetScan and identified amongst 23 differentially regulated genes, semaphorin 3E (Sema3E) (Fig. 6A). Sema3E regulates tumor cell survival by suppressing an apoptotic pathway (38). The interaction of miR183 with semaphorin 3E was confirmed by expression of miR183-mimic in Pten/p53 BTIC, resulting in a highly significant (p <0.001) down-regulation of semaphorin 3E transcripts. Conversely, expression of miR183-inhibitor in Idh1/Pten/p53 cells, significantly upregulated semaphorin 3E transcripts (Fig. 6B). A luciferase reporter assay of miR183 binding (Fig. 6C) to the 5’ Untranslated Region (UTR) of Sema3E containing wildtype or mutated miR183-5p binding site showed a reduction of the luciferase signal upon miR183 binding to the Sema3E UTR but not to the mutated control Sema3E UTR (Fig. 6D), i.e. there is a functional interaction of miR183 with the Sema3E promoter. In keeping, knockdown of Sema3E with two different shRNA (Fig. 6E) reduces proliferation of Pten/p53 cells (Fig. 6F), sensitises them to Tunicamycin-induced ER stress (Fig. 6G) and induces apoptosis. This interaction is further confirmed in Idh/Pten/p53 BTIC (miR183high) which show a downregulation of Sema3E (Fig. 6H). In conclusion, we show here the role of miR183 in targeting Sema3E and reducing its expression, thus antagonising the apoptosis-suppressing effect, rendering cells more sensitive to ER stress.

Figure 6. miR183 regulate cell response to ER stress through targeting Sema3e.

A, Target binding sites of miR183 relevant to apoptosis ae identified with TargetScan and identified of Sema3E amongst 23 differentially regulated genes. B, Pten/p53 BTIC express higher levels of Sema3e than Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC (n=3). miR183 overexpression (=mimic) in Pten/p53 down regulates Sema3E, and miR183 inhibition in Idh1/Pten/p53 BTIC upregulates Sema3e. C, Binding sites between miR183 and Sema3E 3’UTR and scramble (mut) in the luciferase reporter construct. D, Luciferase assay confirming direct binding between miR183 and Sema3e. E immunoblot of Pten/p53 cells (high Sema3E base levels) transfected with two different Sema3E shRNA confirms functional suppression of Sema3E. F, one Pten/p53 BTIC and two Pten/p53 Sema3E knockdown BTIC lines confirm reduction of proliferation, and (G) increased apoptosis upon tunicamycin–induced ER stress (2 independent experiments). H, Sema3E expression is reduced in Idh1/Pten/p53 tumors (n=7, controls n=7).

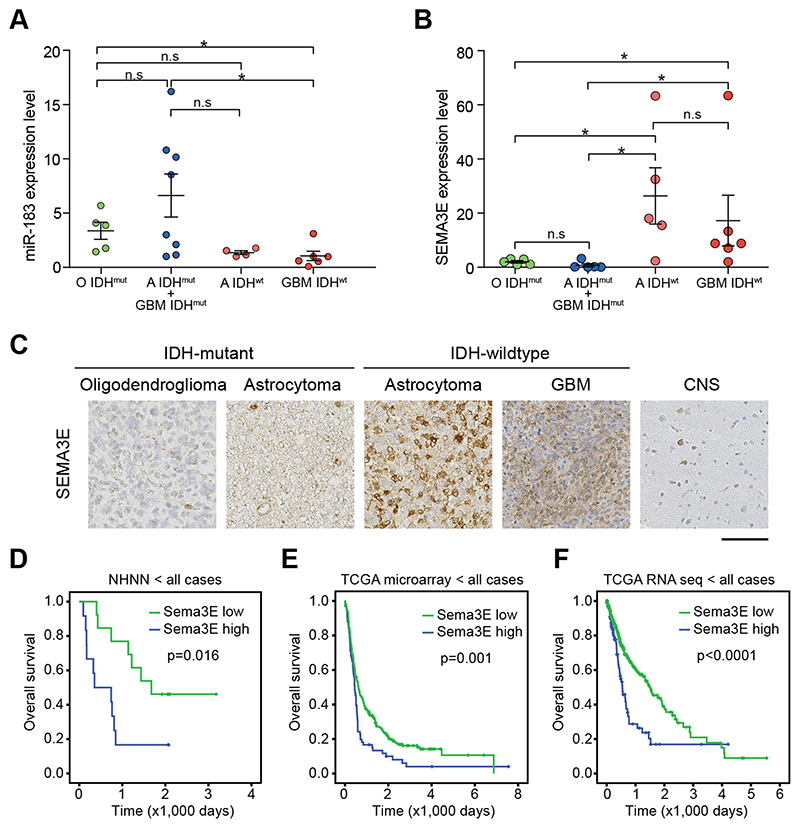

miR183 and semaphorin 3E expression inversely correlate in brain tumors in vivo

To demonstrate the inverse correlation of Sema3E and miR183 expression, we analysed transcripts of miR183 and found a statistically non-significant trend of increased miR183 expression in Idh1/Pten/p53 tumors compared to Pten/p53 controls, and inversely, a non-significant trend of reduced semaphorin 3E expression in Idh1/Pten/p53 tumors. Immunostaining for Sema3E protein on murine brain tumors showed patchy expression in tumor cells and widespread expression in selected neuronal populations. Overall, however there was no significant difference between Idh-mutant and IDH-wildtype tumors.

Semaphorin 3E is downregulated in IDH-mutant gliomas

To translate the experimental findings to the biology of human gliomas, we analysed miR183 and Sema3E transcripts in a selection of human gliomas. IDH-mutant astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas were compared to IDH-wildtype astrocytic gliomas with molecular signature of glioblastoma (4)), and to IDH-wildtype GBM (1). The tumors used in this study were previously described and molecularly characterised in detail (17). First, we determined transcript levels of miR183 in IDH-mutant (n=13; 5 oligodendrogliomas and 8 astrocytomas) and IDH-wildtype gliomas (n=10; 4 IDH-wildtype astrocytomas with molecular profile corresponding to GBM, and 6 GBM) and found a significantly higher miR183 expression in IDH-mutant gliomas (Fig. 7A),), in keeping with the mouse model where Idh-mutant tumors have higher miR183 transcript levels (p<0.05; Fig. 5G). miR183 downregulates Sema3E through binding to its 3’UTR (Fig. 6C). In keeping, Sema3E transcript levels are low in all IDH-mutant tumors (Fig. 7B, C), and significantly higher in IDH-wildtype gliomas (p<0.05), consistent with the prediction from the in vitro experiments (Fig. 5). Importantly, higher Sema3E expression levels are associated with shorter survival in patients from our own cohort (Fig 7D) as well as the TCGA cohorts (Fig. 7E, F). The longer survival of patients with lower Sem3E expression is explained by an overrepresentation of IDH-mutant tumors in this cohort, consistent with our data in Fig. 7B, C). In conclusion, we show that IDH-mutant gliomas express high levels of miR183 which downregulates its target Sema3E, and Sema3E expression inversely correlates with survival.

Figure 7. Translational validation of miR183 effects on Sema3E expression in human brain tumors.

A, miR183 is expressed at higher levels in two IDH-mutant brain tumor types ((Oligodendrogliomas, green and Astrocytomas, blue), and reduced in IDH-wildtype gliomas with molecular characteristics of GBM (astrocytoma, which can be considered as precursors to IDH-wildtype GBM, light red) and GBM (dark red). B, Sema3E expression in the same tumors, showing significantly higher expression in clinically aggressive IDH-wildtype gliomas than in the two IDH-mutant tumor types, or in CNS grey matter. C, representative histological images of such tumors, immunostained for Sema3E, showing no or little expression in the IDH-mutant tumors and strong expression in IDH mutant gliomas. C, D, E: Kaplan Meyer survival curves show a significantly longer overall survival of patient whose tumors express higher levels of Sema3E. NHNN, our own patient cohort, TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset.

Discussion

In this study we show a novel role of mutant Idh1 (R132H) in sensitising glioma cells to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress through upregulation of miR183 and suppression of its target semaphorin 3E (SemaE3), leading to apoptosis. We induced Idh1 R132H expression and loss of Pten and p53 in the SVZ (14) of newborns. This model (i) allows the tumor to develop in an environment similar to the SVZ of young human adults, i.e. during a certain developmental stage of the cell of origin (“window of opportunity”); (ii) combines Idh1 R132H and p53 mutations that are commonly found in astrocytomas; (iii) overexpresses PDGFR, a feature of IDH-mutant astrocytomas (39) and (iv) rapidly forms tumors to allow the study of large cohorts and the effects of inhibitory or stimulating signals. The effects of mutant Idh1 were selectively studied by comparing Idh-mutant with wildtype cells, i.e. Idh1/p53 with p53 mutant tumors and Idh1/Pten/p53 with Pten/p53 mutant tumors. Corresponding to IDH-mutant human tumours (5), Idh R132H-mutant murine cells and tumors produce the metabolite D-2-Hydroxyglutarate (D2HG) (Fig. 1D). The Idh R132H mutation delays self-renewal and proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells in vitro (Fig. 1E) and in vivo. Interestingly, this is in discrepancy with previous reports where the presence of mutant Idh1 R132H in stem/progenitor cells led to an expansion of the progenitor pool. (7). It is possible that our study more accurately tracked the fate of recombined, Idh1 R132H cells with a mutation specific antibody, whilst the previous study examined only indirect evidence of recombination (7). A key finding in human IDH-mutant gliomas is the relatively slow growth compared with IDH-wildtype “counterparts”, although it should be acknowledged that these “counterparts” are biologically distinct entities which have only morphological features in common (IDH-mutant and IDH-wildtype GBM, and correspondingly IDH-mutant and IDH-wildtype astrocytomas). Thus, a direct comparison of the pathobiology of IDH-mutant and IDH-wildtype gliomas made it difficult to dissect the specific role if mutant IDH. Therefore our model was designed to identify biological effects related to IDH1 R132H comparing Idh1/p53 with p53 mutant tumors and Idh1/Pten/p53 with Pten/p53 mutant tumors. Corresponding to the human counterparts, our experimental IDH-mutant and wildtype gliomas are morphologically indistinguishable (Fig. 3A), and the IDH-mutant gliomas produce D2HG ((5,40), Fig. 3B). Importantly, whilst it is not possible to directly demonstrate a growth-inhibiting effect of mutant IDH in human tumors (due to the lack of a biologically equivalent, direct comparator), we can demonstrate that Idh1 (R132H) significantly delays tumorigenesis (Fig. 3C). Our experimental paradigm differs from previous studies (9), combining some, but not all genetic lesions of IDH-mutant astrocytomas. The study of (9) has in common with our model the expression of mutant IDH1, targeting of Pten, but not p53. Instead, their model also targets Atrx, which is a diagnostic mutation in IDH-mutant astrocytomas (41), and it required additional CDKN2A/B deletion to elicit tumours (42,43).

Direct comparison of IDH-mutant with wildtype tumors (in an otherwise identical genetic background) revealed that mutant IDH sensitises BTIC to ER stress (Fig. 4). This led to the identification of differentially expressed microRNAs (miRNAs). miRNAs control many biological processes, such as cell cycle, apoptosis, stem cell differentiation, and immune responses (44), and they also play a key role in the differentiation and maintenance of tissue identity (45). We found that miR183, a member of a family comprising miR183, miR182 and miR96 was differentially regulated. This miR cluster is highly conserved and miR183 has varied effects during development, in mental health and cancer (36), utilising multiple mechanisms governing development, energy and metabolism, and immune signalling (36). A mouse model where the microRNA-183/96/182 cluster was inactivated showed retina degeneration but no additional phenotype (46). In lung cancer, overexpression of miR183 inhibits growth, consistent with our findings (47), and overexpression was also shown in medulloblastoma (48). In malignant gliomas an effect of miR183 on the expression of IDH2 and HIF1α have been described (49), but no mechanistic context has been given.

We have identified Sema3E as a direct target of miR183. Semaphorins are a large family of conserved, secreted and membrane-associated proteins which possess a semaphorin domain and a PSI domain (found in plexins, semaphorins and integrins) in the N-terminal extracellular portion (50). The semaphorin guidance molecules and their receptors, the plexins, are often inappropriately expressed in cancers. Sema3E has recently been identified to regulate tumor cell survival in breast cancer by suppressing an apoptotic pathway (38) by suppressing an apoptotic pathway triggered by the Plexin D1 dependence receptor. In analogy with our findings where higher Sema3E levels are associated with the more aggressive IDH-wildtype glioma (Fig. 7B, C), it has been shown that Sema3E level correlates with metastatic progression of human breast cancers (38). Silencing of Sema3E induces apoptosis in the 4T1 mouse mammary breast cancer, consistent with our findings that IDH mutant, Sema3Elow cells are more sensitive to apoptosis, in particular under ER stress (Fig. 6E-G). Lower Sema3E expression is associated with better survival (Fig. 7), as Sema3Elow tumors are strongly associated with the IDH mutation which correlates with better clinical outcome. Our findings suggest that drugs inhibiting the enzymatic effect of IDH1 R32H (e.g. Ag inhibitors) may counteract the growth-delaying, apoptosis-promoting effect of D2HG (Fig 3C, D), thus potentially reducing the efficacy of treatments that aim to induce cytotoxic stress and cell death.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

The pathological metabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate, generated by IDH-mutant astrocytomas, sensitizes tumor cells to ER-stress and delays tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgements

The PDGFB-Ires-Cre retroviral construct was kindly provided by Prof. Peter Canoll (Columbia University Medical Center, USA). Platinum E cells were kindly provided by Prof. Verdon Taylor (University of Basel, Switzerland). We thank G. Graham, C. Fitzhugh, R. Labesse-Garbal and other staff of the MRC Prion Unit Biological Services facility for animal observation and care.

Financial support

Part of this work was supported by a grant from the Brain Tumour Charity UK to NL and SB (BTC, 8/128) and by a Centre grant from BTC (8/197). NL was also supported by a Centre of Excellence grant to Queen May University London from Brain Tumour Research UK. SB is supported by the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centre’s funding scheme and BRC399/NS/RB/101410. The tissue resource was supported by the CRUK Accelerator Ed-UCL Grant C416/A23615. YZ was supported by a PhD Overseas research scholarship, UCL-ORS) and UCLH Trustees. ME was funded by a Cancer Research UK Accelerator grant Cl 15121 A 20256.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Stefan Pusch and Andreas von Deimling are patent holders of “Means and methods for the determination of (D)-2-hydroxyglutarate (D2HG)”, the enzymatic 2HG assay used for 2HG determination in this manuscript (WO2013127997A1).

Andreas von Deimling is patent holder of “Methods for the diagnosis and the prognosis of a brain tumor”, the IDH1R132H specific antibody used in this manuscript (US 8367347 B2).

All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD, Yung WK, Salama SR, et al. Comprehensive, Integrative Genomic Analysis of Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2481–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuss DE, Kratz A, Sahm F, Capper D, Schrimpf D, Koelsche C, et al. Adult IDH wild type astrocytomas biologically and clinically resolve into other tumor entities. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:407–17. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–44. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki M, Knobbe CB, Itsumi M, Elia AJ, Harris IS, Chio II, et al. D-2-hydroxyglutarate produced by mutant IDH1 perturbs collagen maturation and basement membrane function. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2038–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.198200.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardella C, Al-Dalahmah O, Krell D, Brazauskas P, Al-Qahtani K, Tomkova M, et al. Expression of Idh1(R132H) in the Murine Subventricular Zone Stem Cell Niche Recapitulates Features of Early Gliomagenesis. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:578–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye D, Ma S, Xiong Y, Guan KL. R-2-hydroxyglutarate as the key effector of IDH mutations promoting oncogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:274–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philip B, Yu DX, Silvis MR, Shin CH, Robinson JP, Robinson GL, et al. Mutant IDH1 Promotes Glioma Formation In Vivo. Cell Rep. 2018;23:1553–64. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amankulor NM, Kim Y, Arora S, Kargl J, Szulzewsky F, Hanke M, et al. Mutant IDH1 regulates the tumor-associated immune system in gliomas. Genes Dev. 2017;31:774–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.294991.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marino S, Vooijs M, van Der Gulden H, Jonkers J, Berns A. Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum. Genes Dev. 2000;14:994–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino S, Krimpenfort P, Leung C, van der Korput HA, Trapman J, Camenisch I, et al. PTEN is essential for cell migration but not for fate determination and tumourigenesis in the cerebellum. Development. 2002;129:3513–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.14.3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori T, Tanaka K, Buffo A, Wurst W, Kuhn R, Gotz M. Inducible gene deletion in astroglia and radial glia--a valuable tool for functional and lineage analysis. Glia. 2006;54:21–34. doi: 10.1002/glia.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacques TS, Swales A, Brzozowski MJ, Henriquez NV, Linehan JM, Mirzadeh Z, et al. Combinations of genetic mutations in the adult neural stem cell compartment determine brain tumour phenotypes. EMBO J. 2010;29:222–35. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonabend AM, Yun J, Lei L, Leung R, Soderquist C, Crisman C, et al. Murine cell line model of proneural glioma for evaluation of anti-tumor therapies. J Neurooncol. 2013;112:375–82. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1082-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Wang X, Ke ZJ, Comer AL, Xu M, Frank JA, et al. Tunicamycin-induced unfolded protein response in the developing mouse brain. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;283:157–67. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li N, Zhang Y, Sidlauskas K, Ellis M, Evans I, Frankel P, et al. Inhibition of GPR158 by microRNA-449a suppresses neural lineage of glioma stem/progenitor cells and correlates with higher glioma grades. Oncogene. 2018;37:4313–33. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0277-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian A, Kuehn H, Gould J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GSEA-P: a desktop application for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3251–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balss J, Pusch S, Beck AC, Herold-Mende C, Kramer A, Thiede C, et al. Enzymatic assay for quantitative analysis of (D)-2-hydroxyglutarate. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:883–91. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1060-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mimura N, Fulciniti M, Gorgun G, Tai YT, Cirstea D, Santo L, et al. Blockade of XBP1 splicing by inhibition of IRE1alpha is a promising therapeutic option in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:5772–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriquez NV, Forshew T, Tatevossian R, Ellis M, Richard-Loendt A, Rogers H, et al. Comparative expression analysis reveals lineage relationships between human and murine gliomas and a dominance of glial signatures during tumor propagation in vitro. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5834–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:16878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capper D, Zentgraf H, Balss J, Hartmann C, von Deimling A. Monoclonal antibody specific for IDH1 R132H mutation. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:599–601. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–1. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pusch S, Schweizer L, Beck AC, Lehmler JM, Weissert S, Balss J, et al. D-2-Hydroxyglutarate producing neo-enzymatic activity inversely correlates with frequency of the type of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutations found in glioma. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:19. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benedykcinska A, Ferreira A, Lau J, Broni J, Richard-Loendt A, Henriquez NV, et al. Generation of brain tumours in mice by Cre-mediated recombination of neural progenitors in situ with the tamoxifen metabolite endoxifen. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:211–20. doi: 10.1242/dmm.022715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson EL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Gil-Perotin S, Roy M, Quinones-Hinojosa A, VandenBerg S, et al. PDGFR alpha-positive B cells are neural stem cells in the adult SVZ that form glioma-like growths in response to increased PDGF signaling. Neuron. 2006;51:187–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keestra-Gounder AM, Byndloss MX, Seyffert N, Young BM, Chavez-Arroyo A, Tsai AY, et al. NOD1 and NOD2 signalling links ER stress with inflammation. Nature. 2016;532:394–7. doi: 10.1038/nature17631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, Turcan S, Grommes C, Campos C, et al. An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science. 2013;340:626–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1236062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the unfolded protein response on human disease. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:857–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Schadewijk A, van’t Wout EF, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS. A quantitative method for detection of spliced X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1) mRNA as a measure of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Cell stress & chaperones. 2012;17:275–9. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0306-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirota M, Kitagaki M, Itagaki H, Aiba S. Quantitative measurement of spliced XBP1 mRNA as an indicator of endoplasmic reticulum stress. The Journal of toxicological sciences. 2006;31:149–56. doi: 10.2131/jts.31.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maurel M, Chevet E. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling: the microRNA connection. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2013;304:C1117–26. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00061.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dambal S, Shah M, Mihelich B, Nonn L. The microRNA-183 cluster: the family that plays together stays together. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7173–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hilgers V, Bushati N, Cohen SM. Drosophila microRNAs 263a/b confer robustness during development by protecting nascent sense organs from apoptosis. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luchino J, Hocine M, Amoureux MC, Gibert B, Bernet A, Royet A, et al. Semaphorin 3E suppresses tumor cell death triggered by the plexin D1 dependence receptor in metastatic breast cancers. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:673–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorovets D, Kannan K, Shen R, Kastenhuber ER, Islamdoust N, Campos C, et al. IDH mutation and neuroglial developmental features define clinically distinct subclasses of lower grade diffuse astrocytic glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2490–501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sahm F, Capper D, Pusch S, Balss J, Koch A, Langhans CD, et al. Detection of 2-hydroxyglutarate in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded glioma specimens by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reuss DE, Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Wiestler B, Capper D, Koelsche C, et al. ATRX and IDH1-R132H immunohistochemistry with subsequent copy number analysis and IDH sequencing as a basis for an "integrated" diagnostic approach for adult astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma and glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:133–46. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shirahata M, Ono T, Stichel D, Schrimpf D, Reuss DE, Sahm F, et al. Novel, improved grading system(s) for IDH-mutant astrocytic gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:153–66. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Deimling A, Ono T, Shirahata M, Louis DN. Grading of Diffuse Astrocytic Gliomas: A Review of Studies Before and After the Advent of IDH Testing. Seminars in neurology. 2018;38:19–23. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1636430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pham JT, Gallicano GI. Specification of neural cell fate and regulation of neural stem cell proliferation by microRNAs. Am J Stem Cells. 2012;1:182–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lumayag S, Haldin CE, Corbett NJ, Wahlin KJ, Cowan C, Turturro S, et al. Inactivation of the microRNA-183/96/182 cluster results in syndromic retinal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E507–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212655110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang G, Mao W, Zheng S. MicroRNA-183 regulates Ezrin expression in lung cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3663–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Z, Li S, Cheng SY. The miR-183 approximately 96 approximately 182 cluster promotes tumorigenesis in a mouse model of medulloblastoma. J Biomed Res. 2013;27:486–94. doi: 10.7555/JBR.27.20130010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka H, Sasayama T, Tanaka K, Nakamizo S, Nishihara M, Mizukawa K, et al. MicroRNA-183 upregulates HIF-1alpha by targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) in glioma cells. J Neurooncol. 2013;111:273–83. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-1027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alto LT, Terman JR. Semaphorins and their Signaling Mechanisms. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1493:1–25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6448-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.