Abstract

The lysosomal cell death, (LCD), pathway is a caspase-independent, cell death pathway that has been suggested as a possible target for cancer therapy; making the development of sensitive and specific high-throughput (HT) assays to identify LCD-inducers highly desirable. Here, we report a two-step HT screening platform to reliably identify LCD-inducers. First we identify compounds that kill through a non-apoptotic pathway. A multiplexed phenotypic image-based assay using a Gal-3 reporter was then used to further classify hits as LCD-inducers. The identification of permeablized lysosomes in our phenotypic assay is not affected by changes in the lysosomal pH, thus resolving an important limitation in currently used methods. We have validated our platform in a screen by identifying 24 LCD-inducers, some of them previously known to be LCD-inducers. Although most LCD-inducers were cationic amphiphilic drugs, (CADs) our data also gave new insights into the biology of LCD suggesting that lysosomal accumulation and ASM inhibition are not sufficient or necessary for the induction of LCD. Accordingly, we have identified a non-CAD LCD-inducer, which is of great interest in the field. Overall our results demonstrate a robust rapid HT platform to identify novel LCD-inducers that will also be very useful for gaining deeper insights in to the role of role of lysosomal membrane permeabilization in drug-induced toxicity.

Introduction

Apoptosis is a universal, caspase-dependent cell death pathway which is the target of many cancer therapies. However, tumor cells often harbor genetic mutations that make them resistant to apoptotic cell death. Many changes conferring apoptosis resistance have been observed different cancer cells, such as mutations in the gene encoding p53 (TP53) which are found in 50% of solid tumors (Brown and Attardi, 2005; Jaattela, 2004). In breast and prostate cancers, increased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 blocks the apoptotic pathway (Yang, et al., 1997). Therefore, the induction of cell death in cancer cells by pathways that are caspase, p53 or Bcl2-independent are very interesting for the development of novel anticancer treatments. One such an alternative cell death pathway is lysosomal cell death (LCD) that has been suggested in recent years as a possible target for cancer therapy (Groth-Pedersen and Jaattela, 2013).

Lysosomes are digestive organelles that are essential for cell homeostasis (de Duve, 1983; Luzio, et al., 2007). They act as the cell recycling center and receive cargo mainly through autophagy and endocytosis. Apart from their function in general protein and organelle turnover, lysosomes are also involved in processes such as control of cell cycle progression, antigen presentation, epidermal homeostasis, and hair follicle morphogenesis (Reinheckel, et al., 2001). Remarkably, lysosomes have also been shown to be important players in triggering programmed cell death (PCD). Lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) and the subsequent release of lysosomal hydrolases to the cytosol is the main hallmark of LCD, also called LMP-induced apoptosis-like PCD (Appelqvist, et al., 2013; Cesen, et al., 2012; Kroemer and Jaattela, 2005; Mrschtik and Ryan, 2015). Cathepsin B, L and D, readily abundant in cells, are among the best defined effector molecules for LCD (Aits and Jaattela, 2013; Kirkegaard and Jaattela, 2009; Stoka, et al., 2007). Nevertheless, their inhibition often confers only partial protection against LMP-induced cell death thus suggesting the possible involvement of other lysosomal enzymes. Although the precise mechanisms of LMP and the role of the released lysosomal enzymes in cell death are still largely unknown, it is clear that LMP can be triggered by a wide variety of stimuli such as death-receptor activation, microtubule-stabilizing agents, oxidative stress, growth factor deprivation, and sphingosine and other compounds (Aits and Jaattela, 2013; Guicciardi, et al., 2004).

Interestingly, upon transformation, many tumor cells are subject to changes in their lysosomal system, that selectively increases their vulnerability to LMP. For example, the expression levels of cathepsin D, B and other cysteine cathepsins are significantly upregulated in many human cancers (De Stefanis, et al., 1997; Kallunki, et al., 2013). Also, the actual number of lysosomes can be increased in cancer cells (Mohamed and Sloane, 2006). Importantly, higher expression of the lysosomal hydrolase Cathepsin B leads to increased degradation of LAMP-1 and −2, which increases the susceptibility to LMP (Fehrenbacher, et al., 2008). Thus, the changes that occur in the lysosomal system of cancer cells sensitize them to LCD.

Because compounds that induce alternative cell death pathways may be able to eradicate tumors that are resistant to the classical therapies, we decided to develop a high throughput screening platform to identify such compounds. Phenotypic image-based assays are highly informative for the elucidation of the mechanism of action of bioactive compounds (Carpenter, 2007; Feng, et al., 2009) as they allow the definition of a cellular phenotype. Hence, we developed a phenotypic assay to identify compounds that can trigger LCD by measuring LMP.

Until now, the development of HTS strategies to discover LCD-triggering compounds has been hampered by the lack of an appropriate detection method for LMP. Most lysosomal fluorescence markers are fluorophores linked to a weak base. Under physiological conditions, these lysosomal dyes accumulate inside lysosomes due to the pH gradient and are trapped upon protonation and become fluorescence [e.g. LysoTracker dyes] (Nadanaciva, et al., 2011). Consequently, basic drugs (eg. CADs) that accumulate in the lysosome and affect their pH can reduce the dye fluorescence even when not causing LMP (Kroemer and Jaattela, 2005; Lemieux, et al., 2004; Ostenfeld, et al., 2008). Other methods used to measure LMP are based in cytosolic extraction and measure of enzymatic activity within the cytosol (Aits, et al., 2015). These assays require numerous steps for the efficient and reliable extraction of the cytosol making them very error-prone and difficult to adapt to a HTS setting. More recently, an assay to measure LMP based on galectin translocation has been established. Galectins are small soluble proteins normally found in the cytosol, which can bind beta-galactoside sugar-containing carbohydrates. These carbohydrates are normally present only on the exterior of the plasma membrane and on the interior of intracellular endocytic vesicles, where they become accessible after vesicle permeabilization. Galectin-3 and −8 have previously been used to measure vacuole lysis promoted by invasive pathogens (Freeman, et al., 2013; Maejima, et al., 2013; Paz, et al., 2010; Thurston, et al., 2012). We have also described the use of galectin-3 (Gal-3) to visualize and quantify macropinositome leakage during Induced Transduction by Osmocytosis and Propanebetaine (iTOP) (D’Astolfo, et al., 2015). More recently, we have also validated the detection of Galectin puncta as a reporter to measure LMP (Aits, et al., 2015). Galectin1, −3, −8 and −9 translocate rapidly from their diffuse cytosolic localization to leaky lysosomes during lysosomal cell death, thereby forming cytoplasmic puncta. The formation of these puncta occurs regardless of the stimuli used to induce LMP. Importantly, Galectin puncta can be observed early after treatment with LMP inducers, and they are maintained for several hours. These characteristics make galectins an excellent reporter system to develop a live-cell, image-based phenotypic assay for the detection of LMP and identification of LCD triggering compounds in a high throughput setting.

Here, we describe the development and validation of a multi-step phenotypic screening platform which allows the rapid identification of compounds that induce alternative cell death pathways with particular emphasis on LMP as a mechanism of action. The primary screen is a robust highly scalable fluorescence-based high throughput assay that uses genetically modified cell lines to discard the compounds that kill through classical apoptosis identifying those that induce caspase and Bcl2-independent alternative cell death pathways. The secondary screen includes a phenotypic assay, using a Gal-3 reporter cell line, which allows the characterization of the hits as LCD-inducers.

Using our platform, we were able to correctly identify several previously known LCD-inducers validating our strategy but also, the screen revealed LCD-inducers that had not been previously identified. The platform is robust, rapid, and sensitive. Our phenotypic screening platform constitutes a versatile system that can be used to quickly identify novel LCD-inducers using different small molecules libraries and/or different cancer cell types. We discuss the perspectives of this screening platform that can be used to further investigate the poorly understood LCD pathway.

Results

Development of a cell-based high throughput screening assay to identify small molecules that induce caspase-independent cell death

We designed a primary screen to select compounds that can induce alternative cell death pathways while discarding those that can only kill through apoptosis. The screen was based on a simple, homogenous high throughput assay that measures cell death using propidium iodide (PI) staining on apoptosis resistant cells.

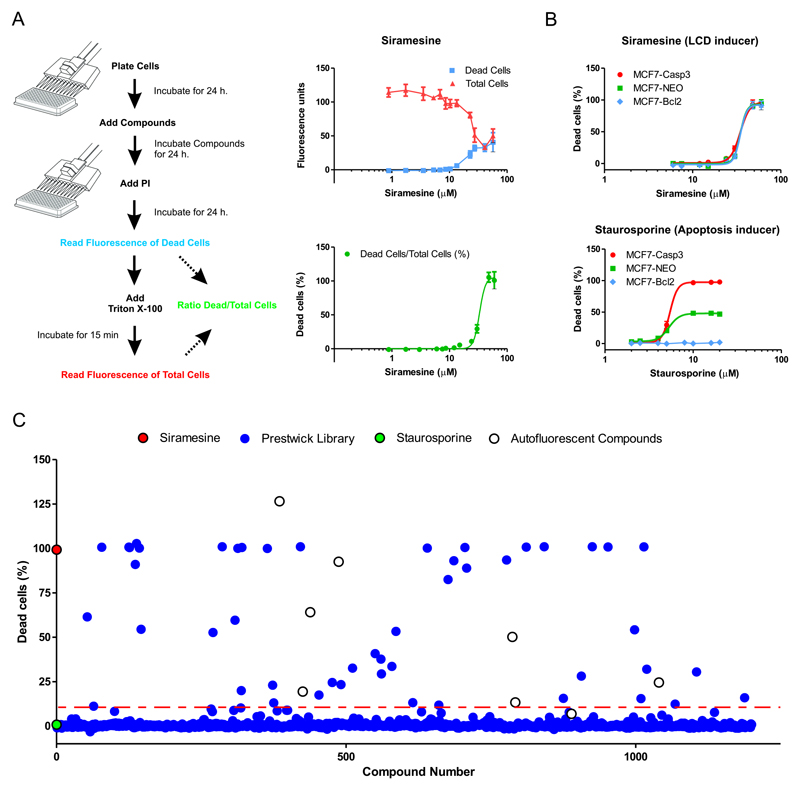

Propidium Iodide is an inexpensive fluorescent dye that has been widely used to measure cell death by assessing plasma membrane integrity. It is frequently combined with a second stain to quantify total cells - e.g. SYBR Green or Hoechst (Buenz, et al., 2007; Feng, et al., 2014) – measuring cell death with automated microscopy. As an alternative, PI has also been used as a single stain, but cell death is analyzed by flow cytometry to allow the determination of total cells in each sample (Edwards, et al., 2007). Our assay also uses PI as the only cell stain but quantify total cells different thus making it suitable for a plate reader which allows higher throughput. In brief, our PI Cytotoxicity Assay works as follows (Figure 1A). After compound treatment, dead cells are labeled with PI giving a red fluorescence that is proportional to the amount of dead cells in the well. After the first fluorescence measurement, a solution of 0.8% Triton-I00x is added to permeabilize and label all cells in the well. The PI fluorescence is then measured again, to obtain a value that is now proportional to the total amount of cells present in each well. This ratiometric assay allows us to calculate the proportion of cell death induced by the compound treatment (Figure 1A) eliminating the variations that can arise from a different number of cells per well and/or different growth rates resulting from compound treatment.

Figure 1. Development of a cell-based high throughput screening assay to identify compounds that induce alternative cell death pathways.

A. Left panel. Scheme of the PI Cytotoxicity Assay used in our primary HTS. Cells were treated for 24 hs with compounds before labeling with propidium iodide (PI) and measuring fluorescence (Dead cells). Then, cells were treated with 0.8% of Triton-100x to permeabilize all cells and fluorescence was measured again, now being proportional to the total amount of cell per well (Total cells). The % of dead cells per well was calculated with the formula: Dead cells/Total cells x 100. Right panel. Cytotoxicity concertation-response curves of Siramesine prepared in our laboratory (see also Figure S1) in MCF7 cells. Cells were exposed 24 hs to siramesine at 12 different concentrations from 2 μM to 50 μM. The top graph shows the raw fluorescence values after the first (dead cells) and second (total cells) measurements. In the bottom graph the calculated % dead cells were used to calculate the LC50 = of 33.19 ± 2.8μM with a R2=0.906. Value is LC50 ± 95% confidence interval (95% CI) form a best-fit curve with a non-linear regression model using GraphPad Prism 5.0.

B. Cytotoxicity dose-response of siramesine and staurosporine were measured as described in A) in MCF7-wt, MCF7-Bcl2 and MCF7-Casp3. Cells were treated for 24 hs at 8 different concentrations ranging from 1 μM to 60 μM. The percentage of dead cells was used to calculate the LC50 form a best-fit curve with a non-linear regression model using GraphPad Prism 5.0. For siramesine: LC50 (MCF7-wt) = 36.3 ± 3.0μM, LC50 (MCF7-Bcl2) = 34.9 ± 4.6μM, LC50 (MCF7-Casp3) = 33.8 ± 2.5μM; F-test (GraphPad Prism 5.0) showed no difference between all three LC50 values (p-value = 0.48). For staurosporine: LC50 (MCF7-Casp3) = 5.4 ± 2.0μM. Values are LC50 ± 95% Cl form a best-fit curve with a non-linear regression model using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software.

C. We used our PI Cytotoxicity Assay to screen 1280 compounds from the Prestwick library. MCF7-Bcl2 were treated with compounds at 50 μM for 24 h. As control we used siramesine (cyan dot) as LCD-inducers, and staurosporine (yellow dot) as apoptosis inducer. The mean of DMSO samples was used as background discount. Hits threshold was set to 20% of dead cells (red dashed line). Autofluorescent compounds (green dots). Raw values can be found in Table 1.

To evaluate the performance of our PI Cytotoxicity Assay, we determined the LC50 (concentration with 50% PI positive cells after treatment) of siramesine, a well-characterize LCD inducer (Ostenfeld, et al., 2008), on the human breast cancer cell line MCF7 after 24 h of exposure. Siramesine, is not commercially available and was synthesized in our laboratory following the protocol described in materials and methods (Figure S1). Using our PI-Cytotoxicity Assay we found an LC50 of 33.19 ± 2.8μM (Figure 1A). This LC50 is higher than the previous published values but the difference can be attributed to experimental conditions, mainly the difference in cell density which affects siramesine sensitivity (Ostenfeld, et al., 2005). The method is highly reproducible, since we obtained similar LC50 values for siramesine in five independent experiments (Figure 1A). Thus, these results illustrate the utility of our assay and, in addition, confirm the cytotoxicity of our newly synthesized siramesine. Importantly, no washing step is required, making the assay amenable to high throughput applications. In a pilot experiment in 96-well format using siramesine (30μM, positive control) and 0.5% DMSO (negative control), the assay gave an 8-fold signal to background ratio (data not shown), which is more than sufficient a for high throughput screening assay. The Z’ factors measured in 5 independent plates were 0.8-0.95, with an average of 0.86 (data not shown) indicating a robust and reliable assay (Zhang et al.,1999).

The second requirement for our primary screening was to distinguish between compounds that are able to trigger alternative cell death pathways from those that can only induce apoptosis. We propose the use of a genetically modified apoptosis resistant cell line resistant. We test three genetically modified MCF7 breast cancer cell lines with differing sensitivities toward apoptosis: i) MCF7 cells that overexpress Bcl2 protein (MCF7-Bcl2) that are highly resistant to apoptotic cell death (Ellegaard, et al., 2013); ii) The parental MCF7 cells (MCF-wt) that lack functional caspase-3 due to a 47-base pair deletion within exon 3 of the CASP3 gene (Janicke, et al., 1998) and are partially resistant to apoptotic stimuli and iii) MCF7 cells that overexpress wild-type caspase-3 (MCF7-Casp3) and therefore have fully restored apoptotic signaling (Ostenfeld, et al., 2005). Only compounds that act through non-apoptotic pathways are expected to show similarly toxicity for all three cell lines. Compounds that trigger apoptosis would be more toxic to MCF7-Casp3 cells and less toxic to MCF7-Bcl2 cells compared to the MCF7-wt cells. Siramesine showed similar toxicity on all three cell lines (Figure 1B). This is in agreement with the fact that siramesine-induced cell death is Bcl2-insensitive and caspase-3-independent (Ostenfeld, et al., 2008). In contrast, the three cell lines showed very distinct responses to staurosporine, an inducer of classical apoptosis: MCF7-Bcl2 cells were completely resistant in this concentration range, MCF7-wt cells were partially resistant and MCF7-Casp3 cells were highly sensitive, i.e. an expected profile for a drug inducing classical apoptosis (Figure 1B). These results demonstrate that the MCF7-Bcl2 cell line can be used in a primary screen to discriminate between compounds that induce apoptosis (like staurosporine) from those that trigger Bcl2-insensitive and caspase-3-independent cell death alternative cell death pathways, such as LCD (like siramesine).

High throughput screening assay identified 39 small molecules that induced Bcl2- and Caspase 3-independent cell death in cancer cells

We used MCF7-Bcl2 cells to screen the Prestwick Chemical library (Prestwick Chemical, France), composed of 1200 FDA-approved off-patent compounds. The compounds were screened at a final concentration of 50 μM, and cytotoxicity was measured after 24 h using our PI Cytotoxicity Assay as described above. Compounds that induced more than 10% cell death were selected as hits for retesting. Siramesine, was used as positive control and the apoptosis inducer staurosporine was also included. The Z’ score was 0.7 indicating that the response of the controls was similar through all the plates (p > 0.05). We also observed low inter-plate variation (Z’ scores for > 0.5 in all cases) (Zhang, et al., 1999). In this primary screen, 51 compounds were selected as follows: 1) 39 compounds (3% of the library) induced more than 10% cell death in MCF7-Bcl2 cells and were consider as Hits. 2) The other 11 compounds showed low potency (<10%) but had chemical structures closely related to the Hits. These compounds were also selected to further confirm their lack of cytotoxicity and to serve as internal controls in our characterization. The results of the screen are shown in Figure 1C and a list of all 51 selected small molecules is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Screening results for the 51 Hits.

1. Percentage of cell death obtained in the primary screening as in Figure 1C. 2-3. LC50 ± 95%CI calculated with Graph Pad Prism 5.0 from percentages of cell dead at 8 different concentrations. An LC50 >60 means that the compound didn’t showed activity at the measured concertation range. 4. Correspond to the concertation that showed higher spot area with minimum cell death. 5. Average “Spot_Total_Area_PerObject” ± SD, triplicate samples. Asterisk indicate statistical difference with respect to Staurosporine (negative control), with p-values expressed as: *** <0.001, ** 0.001-0.01, * 0.01-0.05 (2 tailed, equal variance t-Test). Values are represented in Figure 5A. (#) Compounds that showed no activity in primary screening but were selected to follow-up due to its structural similarities with the hits. 7. The positive and the negative control were present in all the screening plates in 5 replicates. The value showed here is the average ± SD between all screening plates. 8. Siramesine concertation curve was included in all the screening plates to access variability between the plates. The value showed here is the average ± SD of 9 curves across the screening plates. LT = Lysosomotropic, LCD = Induce Lysosomal cell death, ASM = Induce inhibition of Acid Sphingomyelinase, CAD = Cationic Amphiphilic Drug.

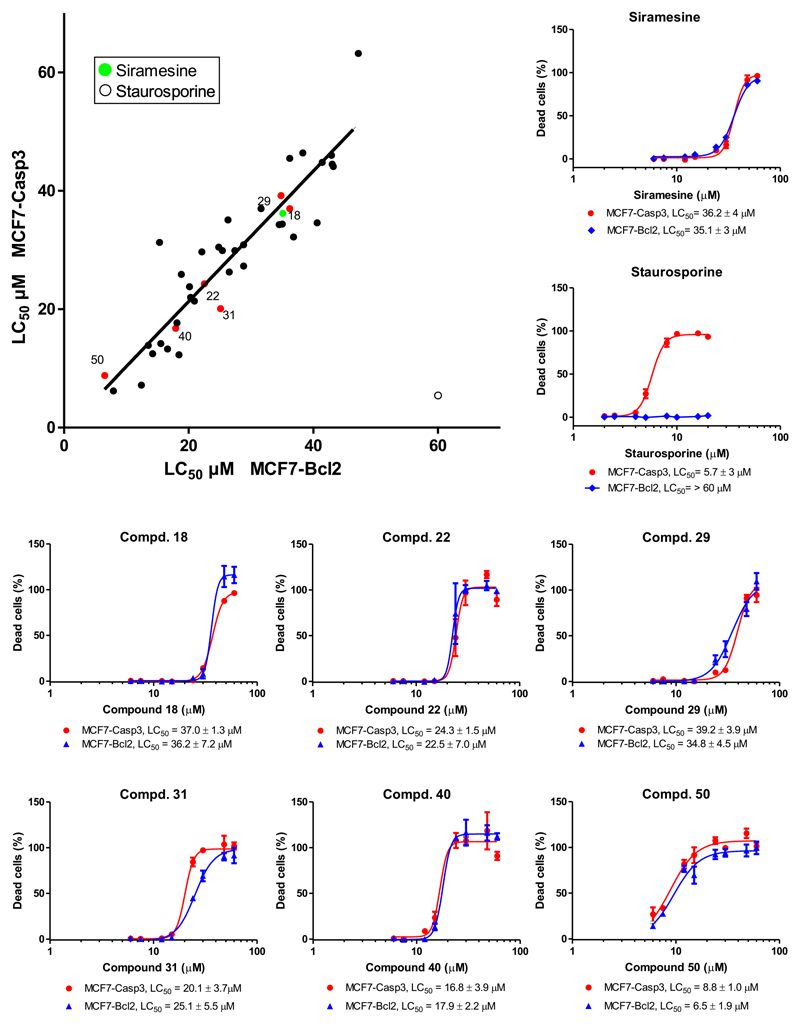

To confirm that the cytotoxicity of the 39 selected compounds was caspase-3-independent, we established and compare their LC50 in MCF7-Bcl2 and MCF7-Casp3 cells using 8 different concentrations ranging for 6-60 μM (Figure 2). The 39 hits induced dose-dependent cytotoxicity in MCF7-Bcl2 cells and MCF7-Casp3 cells while the 11 structurally related extra compounds showed no activity against both cell lines in this concentration range (Table 1 and Figure S2). We found that 34 out of 39 hits showed similar LC50 in both cell lines (F-test, p-value >0.05), suggesting that cell death induced by these compounds is caspase-independent (Figure 2 and Table 1). On the contrary, staurosporine showed low micromolar LC50 in MCF7-Casp3 cells and no cytotoxicity against MCF7-Bcl2 cells at up to 60 μM. Most of the hits had a lower LC50 than siramesine, the most potent hit being auranofin. The success of our approach to identify compounds that induce alternative cell death pathways was validated by the identification of some previously described LCD-inducers such as tamoxifen (Hwang, et al., 2010; Kim, et al., 2014) and terfenadine (Petersen, et al., 2013).

Figure 2. Graphical representation of IC50 values of Prestwick Library Hits in MCF7-Casp3 and MCF7-Bcl2.

MCF7-Casp3 and MCF7-Bcl2 cells were exposed to the 51 compound selected in the primary screen. Cells were treated with 8 different concentrations for 24hs and cell death was measured with the HT PI Cytotoxicity Assay. The percentage of dead cells was plotted with GraphPad Prism 5.0 to calculate the LC50 values. Top-left panel. Graphic representation of the calculated LC50 for each compound on both cell lines. The solid black line correspond to an artificial line with slope = 1 representing the ideal situation where the LC50 is identical on both cell lines. Green dots = LC50 for siramesine calculated form 9 concertation-response curves distributed across the screen plates, blue dots = LC50 for staurosporine, black dots = LC50 for Prestwick library Hits, red dots= LC50 for Prestwick library Hits for which concertation-response curves are showed in the middle and bottom panels. The similar LC50 in both cell lines suggest that cell death induced by most of this compound is indeed Casp3 independent (see also Figure S3). The top-right panel. Concertation-response curves for siramesine (average of 9 curves) and staurosporine. LC50 ± 95% CI are shown. LC50 values for siramesine in both cell lines were compared with an F-test and show no significant difference (p-value = 0.48). Middle and bottom panel. Concertation-response curves for representative compound. LC50 ± 95% CI are shown. F-test and show no significant difference (p-value = > 0.05). The curves for the other compounds are shown in Figure S2.

Inspection of chemical structure similarities revealed that the hits could be classified in 9 different structural groups (Table 1). The largest group of compounds, Group 1, includes 17 phenothiazine derivatives, many of which are tricyclic antidepressants and antipsychotics. Some phenothiazine derivatives have previously been described to accumulate in lysosomes and induce LCD (Table 1 indicated with the acronym LCD) (Zong, et al., 2014). On the other hand, Group 9 includes a variety of structurally unrelated compounds, many of which haven’t been described before to induce an alternative cell death pathway. Importantly, we notice that many of our hits are lipophilic and contain an amine group with a pKa > 6 (Table S1). This resembles the physicochemical properties of so-called cationic amphiphilic drugs (CADs) which are known to accumulate in the lysosome (Nadanaciva, et al., 2011). In fact, at least 6 of our hits have previously been shown do so (Nadanaciva, et al., 2011) (Table 1, indicated as lysosomotropic, LT). More interestingly, 19 compounds have been shown to inhibit acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) (Table 1, indicated with the acronym ASM) (Kornhuber, et al., 2008). Both, the accumulation of compounds in the lysosomes and their ability to inhibit ASM, have been shown to be related to LCD induction (Ellegaard, et al., 2013; Ostenfeld, et al., 2008; Petersen, et al., 2013).

A phenotypic screening assay classify 24 compounds as LCD-inducers

We developed a phenotypic screening assay that can reliably measure LMP, the main hallmark of LCD, in order to determine which of our hits actually killed via LCD. Many groups have used fluorescent dyes such as LysoTraker Red-DND-99 or Acridine Orange to measure lysosomal membrane damage. These methods rely on the pH gradient between the lysosome (4.6-5.0) and the cell cytosol (around neutral) (Antunes, et al., 2001; Lemieux, et al., 2004; Moriyama, et al., 1982). However, most lysosomotropic compounds are basic cationic amphiphilic drugs (CADs) which accumulate in the lysosome as they get protonated, significantly increasing the lysosomal pH and competing with the dyes. This phenomenon results in a pH-dependent decrease in the fluorescence signal of the above-mentioned dyes, (Lemieux, et al., 2004) without necessarily indicating LMP. In fact, many of our 11 structurally related non-active compounds showed complete depletion of LysoTracker-Red florescence after 2-4hs of exposure (Table S1) despite having no cytotoxic effect. This clearly indicates that pH-dependent dyes should not be used to measure LMP.

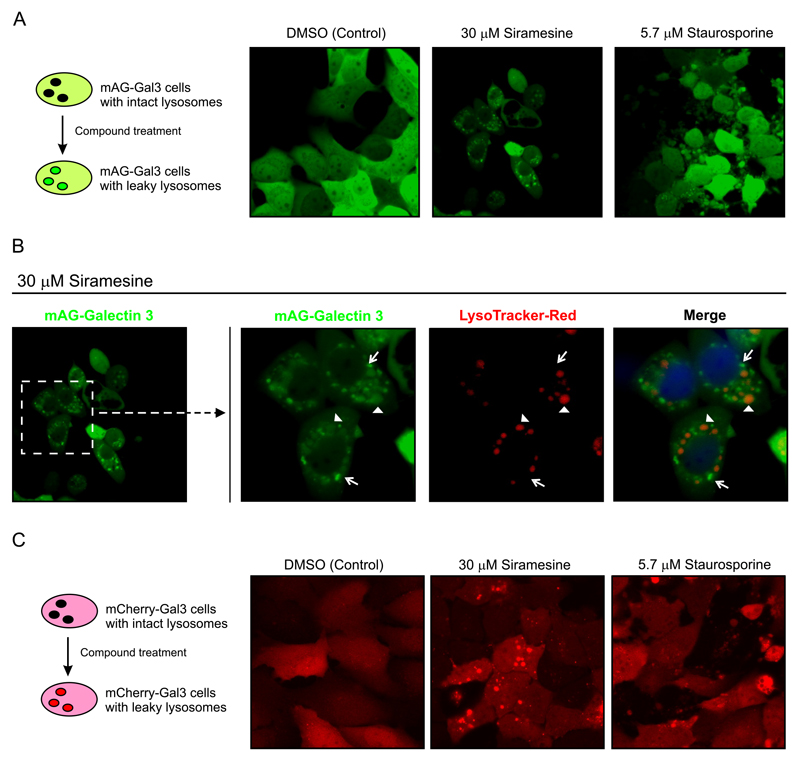

As an alternative, we developed an assay using the Gal-3 reporter system, which has been previously used as a marker of vacuole lysis by invasive pathogens (Freeman, et al., 2013; Maejima, et al., 2013; Paz, et al., 2010) or LMP induced by different stimuli (Aits, et al., 2015). To generate a reporter cell line that expresses Gal-3 in the cytosol, we fused Gal-3 protein to a monomeric green fluorescent protein (mAG-Gal3) with which we stably transfect MCF7 cells. MCF7-mAG-Gal3 cells expressed cytosolic mAG-Gal3 protein (Figure 3A) with a diffuse homogenous phenotype. Upon treatment with siramesine for 6 h mAG-Gal3 formed a punctate pattern. The location of the puncta around the nuclei suggested that these structures corresponded to damaged lysosomes to which mAG-Gal3 had translocated. The punctate pattern was not observed when cells were treated with staurosporine for 6 h, which instead showed a dispersed mAG-Gal3 pattern, similar to the non-treated cells, and apoptotic membrane blebbing. To confirm that mAG-Gal3 dots indeed corresponded to lysosomes with a damaged membrane, MCF7-mAG-Gal3 cells were treated with siramesine for 6 h and stained with LysoTracker Red-DND-99 (Figure 3B). Vesicles with intense mAG-Gal3 fluorescence were negative for LysoTracker indicating membrane damage. The vesicles that still retained LysoTracker were either negative for mAG-Gal3 or showed weak staining suggestive of partial leakage (AIts et al., 2015). Similar phenotypes were observed with a second reporter cell line, U2OS cells stably transfected with m-Cherry-Gal3 plasmid (U2OS-mCherry-Gal3, Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Detection of Lysosomal membrane permeabilization with Galectin-3 reporter cell lines.

A. Left Panel. Schematic representation of the mAG-Gal3 reporter assay. Cells express Gal-3 in the cytosol and contain intact lysosomes (back vesicles). After compound treatment, the rupture of the lysosomal membrane allows the entry of the cytosolic expressed mAG-Gal3 protein, resulting in bright fluorescent dots (permeabilized lysosomes). Right panel. Confocal images of MCF7-mAG-Gal3 cells, after treatment for 8hs with the indicated compounds.

B. MCF7-mAG-Gal3 cells were treated with 30 μM Siramesine for 6 h and then stained with Lysotraker Red-DND-99 to mark the intact lysosomes. Right panel. Zoom-in of the indicated area showing the single channels images for mAG-Gal3 and Lysotracker-Red, and merge. The arrows point to damage lysosomes that showed strong Gal-3 stain and were negative lysotracker. The arrowheads point to lysosomes that haven’t totally release their content yet, showing lysotracker staining and either negative or deem stain for mAG-Gal3.

C. Left Panel. Schematic representation of the mCherry-Gal3 reporter assay. The principle is as in A. Right panel. Confocal images of MCF7-mCherry-Gal3 cells, after treatment for 6 h with the indicated compounds.

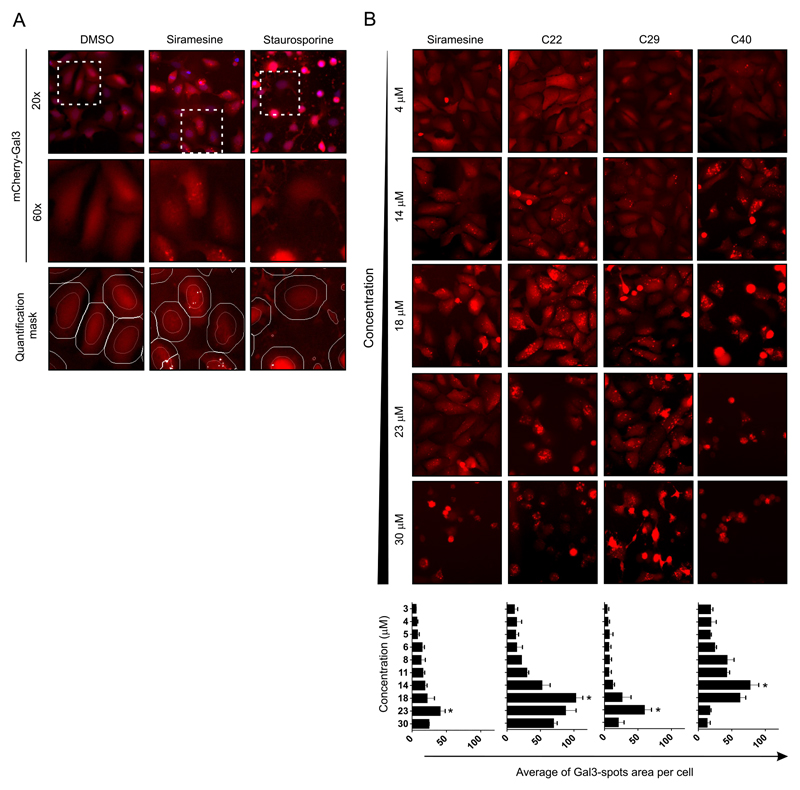

Using the U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 reporter cell line, we developed a rapid cell-based HCS assay to measure lysosomal leakage in live cells. In this assay, the Gal-3 puncta were recognized by automatic microscopy as “spots”. The assay was multiplexed so that cell viability could also be assessed. Calcein-AM, which is only fluorescent in metabolically active cells, was used to guarantee that only live cells were taken into account in the quantification of m-Cherry-Gal3 puncta. The fluorescent dye, Hoechst 33342, was used to stain nuclei. U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 cells were treated for 6 h with serial dilutions (10 concentrations, 3-30 μM) of the 51 compounds selected in the primary screen. The selection of a 6 h treatment was based on time course confocal microscopy experiments in which 6 h was the optimum time to detect abundant mCherry-Gal3 puncta while cells remained still viable as judged by their morphology and Calcein-AM positivity (data not shown). Automated live-cell image acquisition was performed with a Thermo Cell Insight™ High Content Screening (HCS) reader and the quantification algorithm was optimized to detect mCherry-Gal3 puncta. In this algorithm, cells were first identified by their nuclear stain and a circular region for each cell was defined centered in the nucleus. Gal-3 Intense fluorescent areas (spots) within this circular region were identified and analyzed (Figure 4A). In our assay, these spots represent the Gal-3 that have translocated to damage lysosomes and was quantified as the “Mean_spot_area_per_cell (MSAPC)” in channel 2. Special attention was taken to avoid the identification and quantification of cell blebbing, observed with apoptosis inducers like staurosporine, as mCherry-Gal3 puncta (Figure 4A). A punctate pattern of mCherry-Gal3 was observed around the nuclei in samples treated with 23 μM siramesine (Figure 4A). The quantification of 10 random fields in duplicate samples showed an MSAPC of 40.5 ± 7.7 μm2 (Table 1). On the contrary, significantly less Gal-3 puncta were detected in samples treated with DMSO or staurosporine (Figure 4A) with an MSAPC of 5.3 ± 1.6 and 9.7 ± 5.6 μm2, respectively. Hence, the HCS assay was able to correctly identify siramesine as an LCD inducer compound and staurosporine as a non-LCD inducer based on the total area occupied by bright mCherry-Gal3 puncta after treatment. Importantly, we observed a concentration-dependent increase in the mCherry-Gal3 puncta but for some compounds the highest concentration(s) induced extensive cell death with cell rounding-up, which hampered the mCherry-Gal3 spot quantification (Figure 4B). Nevertheless, each compound showed an optimal concentration at which the mCherry-Gal3 puncta were clearly visible and abundant with low cell cytotoxicity (as determined by Calcein-AM stain). Due to the different potency of the hits, the optimum concentration for Gal-3 quantification varied across all 51 tested compounds. Thus, for this type of phenotypic assay it is advantageous to screen all compounds in a dose response scheme instead of simply using a single screening concentration.

Figure 4. Quantification of Gal-3 re-localization to damages lysosomes by automatic microscopy.

A. LMP can be detected with U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 reporter cells using an automatic microscope. Cells were treated for 6 h, at concentration between 3 and 30 μM. Cells were stained with Hoechst (nuclear mask) and Calcein-AM (cell mask) and subjected to quantitative image analysis using the CellInsight™ CX5 High Content Screening (HCS) Platform. The quantification algorithm was optimized to detect the mCherry-Gal3 puncta (damaged lysosomes) within an artificially defined circular area centered on each nucleus. mCHerry-Gal3 puncta were quantified as the Mean_spot_area_per_cells in channel 2. Top row. CellInsight representative images for the vehicle (DMSO), positive (siramesine) and negative (staurosporine), overlays of the nuclei (Channel 1, blue) and mCherry-Gal3 (Channel 2, red). Middle row. Magnification of the mCherry-Gal3 channel for the indicated area. Bottom row. Magnification of the mCherry-Gal3 channel in overlay with the quantification marks for “nucleus” (orange) “cell mask” (white) and “detected spots” (white spots) as determined by the established automatic cell image quantification algorithm.

B. Automatic microscopy images of mCherry-Gal3 channel for four selected compounds at five selected concentrations. The assay was performed as indicated in panel A. There is an optimal concertation for the detection of Gal-3 puncta above which cell rounded-up. Bottom panel. Graphs showing the average “Gal-3 spot area per cells” across the 10 concentrations for the four selected compounds. Error bars are SDs for means of 3 wells. For each well, 10 images with a total of > 500 cells/sample.

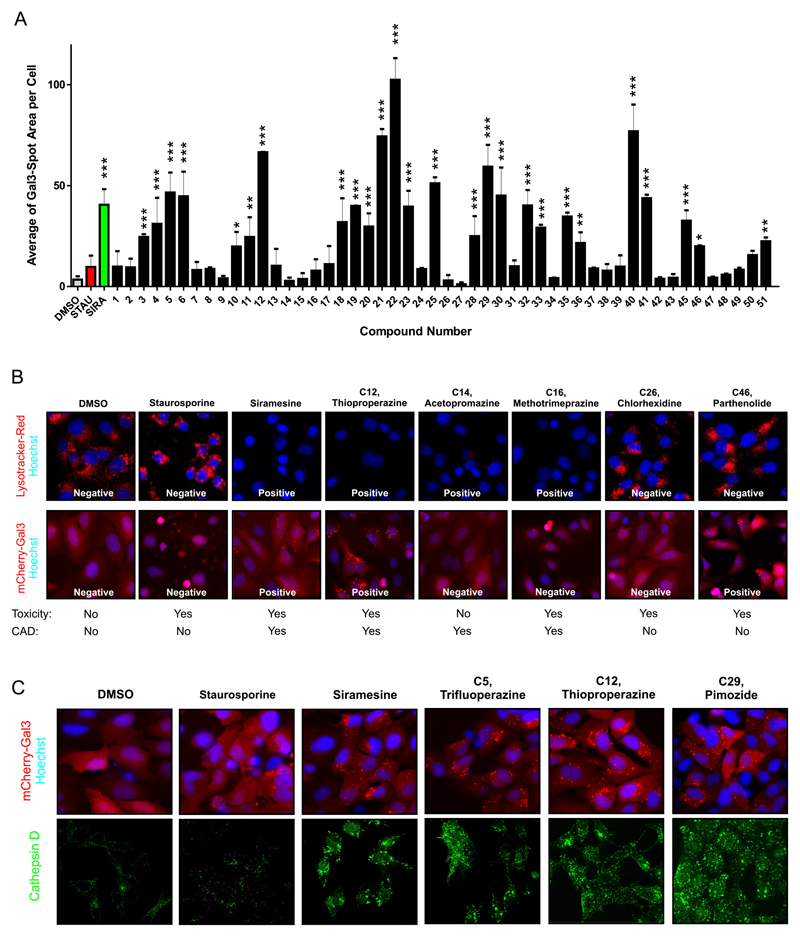

The average of mCherry-Gal3 puncta area per cell at the optimal concentration for each compound was used to determinate which compounds induced lysosomal leakage (Figure 5A). The value obtained for each compound was compared with that of the staurosporine sample (Figure 5A and Table 1). Of the 39 hits identified in the primary screen, 24 (>50%) induced strong mCherry-Gal3 puncta formation at 6 h and were identified as LCD inducers (Table 1). Most of these compounds were CADs but the assay was also able to identify a non-CAD as LCD-inducer, Parthenolide (Table 1 and Figure 5A-B). The remaining 15 compounds, which were able to kill apoptosis-resistant cells, showed no mCherry-Gal3 puncta development indicating a mechanism different than LCD. Among these were the five compounds of the structural groups 6 and 8 (compound 26-27 and 36-38), which most likely kill non-specifically due to detergent properties. Several phenothiazine hits (group 1, compounds 1, 2, 7, 8, 13 and 16) failed to induce the formation of mCherry-Gal3 puncta. Instead they caused the cells to quickly round up, without blebbing or nuclear condensation, suggesting a type of cell death that is neither apoptosis nor LCD. Nevertheless, these Phenothiazine derivatives decreased LysoTracker staining after 2 h indicating that they accumulate in lysosomes (Table S1). As expected, the 11 structurally related compounds which did not induce cell death in the primary screen (Table 1) also failed to induce mCherry-Gal3 puncta, except loperamide and GBR 12909 (compounds 33 and 36). Importantly, most of them did alter LysoTracker staining due to its CAD properties (Figure 5B and Table S1). Thus, this confirms that the Gal-3 reporter assay can discriminate between compounds that induce LMP and those that merely affect the pH of the lysosome but do not permeabilize its membrane. Figure 5B shows example images for compound and show that while the Gal-3 assay is not affected by the basic properties of the compound LysoTracker-Red wrongly identify as LCD-inducer compound that were either non-active (C14) or that were active but don’t seem to damage the lysosomal membrane (C16). This clearly shows the advantages of the Gal-3 assay against using LysoTracker-Red. Moreover, the identification of a non-CAD LCD-inducer and the fact that some CADs showed no Gal-3 puncta, suggests that CAD properties are important but nor sufficient to induce LCD.

Figure 5. Phenotypic determination of LMP by Gal-3 re-localization to damages lysosomes.

A. Average of “Gal-3 spot area per cell” for all 51 Hits, vehicle (DMSO, gray bar), negative control (red bar) and positive control (green bar) at the respective optimal concentration (see table 1). Values are average ± SD of three equally treated wells within a 96-well plate. On each well 10 images with a total of > 500 cells/sample were quantified. Asterisk indicate statistical difference with respect to Staurosporine (Red Bar), with p-values expressed as: *** <0.001, ** 0.001-0.01, * 0.01-0.05 (2 tailed, equal variance t-Test).

B. Top panel. Representative confocal images of MCF7-Bcl2 cells treated for 2h with vehicle (1% DMSO), or a concertation equal to the LC50, for the indicated compounds. Nuclei are visualized with Hoechst 33342 (blue) and cells were stained with Lysotracker-Red. Bottom panel. Representative confocal images of U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 cells treated for 6 h with vehicle (1% DMSO) or the indicated compound at a concertation equal to the optimum Gal-3 detection concertation (see Table1). Nuclei are visualized with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Cytotoxic (yes/no) indicates if the compound was found to kill MCF7-BCl2 cells in primary screening. CAD (yes/no) indicates if the compound is a cationic amphiphilic drug.

C. Top panel. Representative confocal images of U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 cells treated for 6 h with vehicle, 2.5 μM (staurosporine), 23 μM (siramesine), 23 μM (Pimozide, C29), 23 μM (Thioproperazine, C12), 23 μM (Trifluoperazine, C5). Nuclei are visualized with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Lysosomal leakage is visualized by the relocation of Gal-3 to a puncta pattern representing the damaged lysosomes. Bottom panel. Visualization of lysosomal leakage by relocation of Cathepsin-D from a puncta pattern to a more diffuse cytosolic staining. Representative confocal images for siramesine and 3 selected compounds. MCF7-wt cells were treated as indicated for 6 hs, the cells were fixed and stained with anti-Cathepsin D antibody.

Since one of the major hallmarks of LCD is the release of cathepsins to the cytosol, we compared the Gal-3 assay with the detection of cathepsins in the cytosol by immunostaining for 3 compounds classified as LCD inducer in our HCS assay (Figure 5C and 5D). Immunostaining of cathepsin D, showed a change of pattern from punctate to more diffuse cytosolic and nuclear staining upon 6 h treatment with siramesine and the three selected LCD-inducer compounds (Figure 5D). Importantly, cell death induced by these compounds was not decreased by pre-incubation of cells with either a pan-caspase inhibitor or an inhibitor of necroptosis (Figure S5).

All together this demonstrates that our platform can be used to successfully identify inducers of lysosomal cell death.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to develop a rapid phenotypic screening platform for the identification of compounds that induce LCD. We settled upon a two-step strategy. A primary screen aimed at rapidly eliminating the compounds that induce classical apoptosis while identifying those that induce alternative programed cell death. A secondary phenotypic image-based screening used to identify those that specifically induce LCD.

Our primary screen, a ratiometric assay based on nuclear PI-uptake in MCF7-Bcl2 cells, allowed us to rapidly eliminate compounds that only kill through canonical apoptotic pathways. The assay is simple, cheap, fast and very reproducible. It can be read on a fluorescence plate reader making it suitable for high throughput testing of 100,000s of compounds in a short period of time. One major advantage of this assay is that it measures cell death directly. Many commonly used cell viability assays such as the MTT assay, measure metabolism, which can vary independently of toxicity. These assays cannot distinguish between cytotoxicity and inhibition of proliferation. Our assay has the advantage of measuring cytotoxicity independently of metabolism and proliferation, as it calculates the percentage of cell death in relation to the total cell content of each well. Also, the assay can be performed in complete media, allowing for more prolonged compound exposure times than buffer-based systems, and it requires no washing steps which makes amenable to automation. A major advantage of using a genetically modified apoptosis-resistant cell line is that there is no need to introduce a pretreatment with apoptosis inhibitors (Varma, et al., 2013) which are usually not completely specific making it necessary to use several inhibitors to obtain reliable results.

OurGal3 phenotypic assay allowed us to identify LCD inducers amongst the hits from our PI cytotoxicity assay. This assay has the major advantage over previously described methods that the accumulation of the cytosolic expressed fluorescence-tagged Gal-3 in the damaged lysosomes is completely independent of pH as it depends solely in the permeability of the lysosomal membrane. Therefore, our assay minimizes the time consumed during the fruitless analysis of false positives. Furthermore, the assay is simple, rapid, high-throughput and the use of a second live staining allows us to measure LMP in live cells. The utility of our phenotypic approach was supported by the identification of five previously described LCD-inducers, namely Trifluoperazine and Fluphenazine (Zong, et al., 2011), Tamoxifen (Hwang, et al., 2010; Kim, et al., 2014), Terfenadine (Petersen, et al., 2013) and Mefloquine (Sukhai, et al., 2013).

The mechanisms by which the identified LCD inducers disrupt the lysosomes are unknown. However, like Siramesine, most of the hits were CADs. As such, they accumulate in lysosomes as indicated by the pied decrease in LysoTracker-Red fluorescence(Table 1S)(Nadanaciva, et al., 2011). Many of these Lysosomotropic CADs have also been shown to be functional inhibitors of ASM (Kornhuber, et al., 2010; Kornhuber, et al., 2008; Nadanaciva, et al., 2011). Interestingly, the accumulation of compound in the lysosomes has shown to be important to LMP induction (Ostenfeld, et al., 2008) and inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase has also been shown to promote LMP (Petersen, et al., 2013). Astemizole and sertindole (Kornhuber, et al., 2008; Nadanaciva, et al., 2011), which show structural features similar to siramesine, were among the compounds with strongest Gal-3 puncta formation suggesting that they are strong inducers of LCD. Intriguingly, 9 out of 31 CADs didn’t show formation of mCherry-Gal3 spots- e.g. prochlorperazine, metixene and prenylamine-despite inducing cell death. Thus, the data suggest that being a CAD, which results in lysosomal accumulation and ASM inhibition, is important but not sufficient to induce LCD. In agreement with this, our phenotypic assay was also able to identify a non-CAD, parthenolide, as an LCD inducer. This compound has no basic group in its chemical structure and it does not accumulate in lysosomes (See LysoTracker-Red displacement, Table S1). Therefore, Parthenolide must induce LCD by a mechanism independent of lysosomal accumulation. Interestingly, Parthenolide is known to have anti-cancer activity (Kim, et al., 2015; Kreuger, et al., 2012; Wyrebska, et al., 2014) and has even been in clinical trials (Ghantous, et al., 2010) but has never before been described as an LCD inducer. Nevertheless, it has been shown to increases cysteine protease activity and to induce the appearance of large lysosomal-like structures when used as an antiparasitc (Tiuman, et al., 2005), supporting the notion that parthenolide cytotoxicity may be related to lysosomal effects. Parthenolide may affect the lysosomes due to its disruptive effect on microtubules and mitosis (Fonrose, et al., 2007; Schneider, et al., 2015).Other microtubule-targeting drugs have shown similar effects causing inhibition of the spindle protein Eg5/KIF11 which has previously been shown to cause LMP (Groth-Pedersen, et al., 2012; Groth-Pedersen, et al., 2007). In addition, parthenolide can lead to the formation of reactive oxygen species which are known to damage lysosomes (Aits and Jaattela, 2013; D’Anneo, et al., 2013). More experiments are needed to study the mechanism of action of parthenolide and to investigate how LCD can be triggered independently of lysosomal accumulation. It will also be interesting to see whether parthenolide acts synergistically with CADs to induce LCD in cancer cells.

The development of anticancer agents with novel mechanisms of action is of key importance in overcoming clinical therapy resistance. It is surprising to see that of the 39 compounds that were found to induce caspase-3 and Bcl-2 independent cell death in our screen, 24 (61%) were shown to induce LMP/LCD. This supports the notion that LCD is an important alternative cell death pathway that can be exploited for cancer treatment. In cancer cells, the lysosomal compartment is frequently dramatically increased in volume, and shows elevated expression and activity of lysosomal enzymes as well as altered membrane trafficking (Fehrenbacher and Jaattela, 2005). These changes correlate with the aggressiveness of tumors but also sensitize cells to LMP. Therefore, drugs that induce the lysosomal cell death pathway independently of caspases could be particularly efficient in cancer treatment (Groth-Pedersen and Jaattela, 2013). Therefore, the demonstration that LMP is potentially a common mechanism of action for drug that target apoptotic resistant cells is interesting in terms of future drug development. However, anticancer drugs that specifically target this pathway have not yet been developed. This is due in part to the limitations of the previously available assays. Our platform can contribute to overcome this limitation by allowing the rapid and reliable identification of novel inducers of LCD.

Conclusion

We developed a robust, high throughput phenotypic platform that can reliably identify compounds that induce LCD pathway. The assay correctly identified compounds that are known to induce LCD and enabled us to define novel LCD-inducers, including parthenolide which represents a novel class of non-CAD LMP/LCD inducers. The development of anticancer agents with novel mechanisms of action is of key importance in overcoming clinical therapy resistance. The LCD pathway has been suggested as one of this novel potential cancer target (Fehrenbacher and Jaattela, 2005), but anticancer drugs that trigger this pathway are not in clinical use yet. Considering the high frequency of p53 and Bcl2 mutations in human cancer cells, the identification of compounds that induce LMP/LCD could lead to the developed of LCD-targeting drugs.

We envisage that our platform can also be used in early pre-clinical stages to elucidate the role of compound-induced LMP in compound toxicity. Alternatively, it can be incorporated into siRNA knock-down or CRISPR knocks-out screens to study the influence of different genes on LCD induction. These could help to bring some insight into how different stimuli induce LMP, something that is currently unknown. Another extension of our Gal-3 phonotypic assay would be the possibility to measure compound-induced LCD in primary cells, and more importantly in 3D culture systems like cancer organoids (van de Wetering, et al., 2015) which may better reflect the potency and mechanism of action of a certain drug.

Significance

The ability to trigger caspase-3 and Bcl2 independent alternative cells death pathways with small molecules has the potential to transform cancer therapy. In this study we aimed to develop a screening platform to identify small molecules that trigger lysosomal cell death (LCD). Until now the screening of LCD inducers has been limited by the lack of a high throughput assay that can differentiate intact from damaged lysosomes while remaining independent of the changes in lysosomal internal pH. The pH dependency of most lysosomal fluorescence staining for live-cell imaging has systematically leaded to identifying basic compounds that accumulate in lysosomes as potential LCD-inducers (e.g.CADs). Although accumulation in lysosomes has been liked to LCD, our assay clearly demonstrates lysosomal accumulation is not sufficient or necessary for LCD. Therefore, our HT phenotypic assay based in a Gal-3 reporter provides a useful tool to reliably identify LCD-inducers in a technically simple and affordable manner, minimalizing the false positives and increasing the efficiency of screening campaigns.

The LCD pathway has been suggested before as a good target for cancer therapy but anticancer drugs that trigger this pathway haven’t reach the clinic yet. One of the reasons is the current limitations in assays that can be used to find novel small molecules that trigger this pathway. Our HT platform can contribute to overcoming these limitations facilitating the discovery of new LCD-inducers that target apoptotic resistant cells.

Experimental procedures

Chemicals

Propidium iodide (PI, P4170) and Hoechst 33342 (14533) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (P4170). Calcein-AM (C3099) and LysoTracker® Red DND-99 (L7528) were form Thermo-Fisher Scientific. The pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK was from Bachem (N1510.0005). Necrostatin-1 (N9037) and Staurosporine (S5921) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Prestwick Chemical library used for the screening was acquired form Prestwick Chemical, France. For the confirmation screening selected compounds were purchased as single 10 mg vials form Prestwick Chemicals (France) unless otherwise indicated (See Supplemental Experimental Procedures). All other chemicals were also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise indicated.

Synthesis of siramesine

Siramesine was synthesized using a modification of the protocol of Perregaard et.al. (Perregaard, et al., 1995). In brief, commercially available 4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-butanoic acid (1) was converted to 4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-butanol (2) by first producing the methanesulfonate ester (1a) followed by its reduction with LiAH4 to generate the mentioned alcohol. 4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-butanol was arylated using the Ullmann procedure to obtain 4-[1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)-butanol (3). The spiro-[isobenzofuran-1(3H),4’-piperidine] (4) was synthesized as previously described by Sommer et.al. (Sommer and Nielsen, 2004). Finally, siramesine (5) was obtained by amine-alkylation of this spiro-piperidine heterocycle (4) with the methane-sulfonate ester of 3 (3a). Figure S1 summarizes the synthetic strategy of siramesine. Detailed information of the synthetic route and the materials used during the synthesis of Siramesine are includes in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Cell Culture

MCF7-Bcl2 cells and MCF7-Casp3 cells have been described elsewhere (Aits, et al., 2015; Ellegaard, et al., 2013; Ostenfeld, et al., 2005)U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 cells (Maier, et al., 2012) were kindly provided by Dr. Harald Wodrich (Laboratoire de Microbiologie Fondamentale et Pathogénicité, Bordeaux, France). All MCF7 cells were maintained in a basic culture media of high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. Selection antibiotics were as follow: Hygromycin B (150 μg/ml) for MCF7-Bcl2 cells, G418 (200 μg/ml) for MCF7-Casp3 cells and puromycin (2 μg/ml) for MCF7-mAG-Gal3 cells.

PI-Cytotoxicity assay. Calculation of LC50

MCF7 cells were plated in clear-bottom 96-well plates at a density of 93,750 cell/cm2 (30,000 cells/well) and they were allowed to attach overnight. Compounds were serially diluted in DMSO and then added manually form stocks solutions (200x). After 24hs of treatment, the cells were stained with 30 μM of Propidium Iodide (PI) and incubated 30 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured with a SpectraMAXPlus (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) microplate reader with excitation/emission wavelengths of 544/624 nm. Immediately after, we add Triton X-100 at 3.2% and incubated 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured again. The percentages of dead cells at each compound concertation were used to calculate the LC50 form a best-fit curve with a non-linear regression model, using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. All values are indicated as LC50 ± 95% confidence interval (95% CI). More details of this procedure and the statistical treatment of the data are provided in supplemental Experimental Procedures.

High throughput PI-Cytotoxicity Assay

MCF7 cells were plated in clear-bottom 96-well plates at a density of 93,750 cell/cm2 (30,000 cells/well) and they were allowed to attach overnight before compound treatment. Compounds were added using an automatic liquid handler (Sciclone G3 Automated Liquid Handling Workstation, Perkin-Elmer) by a two-step dilution scheme (40x + 5x) form DMSO stock solutions. Siramesine, Staurosporine and DMSO 5% were included as controls in all plates in 5 replicates each. After 24hs treatment, the same staining and fluorescent reading protocol as in PI-Cytotoxicity assay was applied (see above). The percentage of dead cells was calculated form the ratio of the two fluorescence reading. The variability inter-assay (play to plate consistency overall the screening) and intra-assay (5 replicates within each plate) was assessed by calculation the Z0 factor(Zhang, et al., 1999). A Z0 >0.5 was used as criteria for low variability. When necessary, percentages of dead cells at each concertation were used to calculate the LC50 form a best-fit curve with a non-linear regression model using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. A detailed protocol of the High throughput assay as well as a complete description of the statistical analysis of the data is provided in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Reporter plasmids and generation of reporter cell line

The generation of the mAG-Gal3 reporter plasmid (Adgene, Plasmid #62734) was described elsewhere (Appelqvist, et al., 2013). In brief, Phage2 lentiviral plasmid containing EF1a-RFP-ires-PuroR was digested with Nco1 and BamH1 to remove the RFP sequence. The linearized vector was gel-purified and reporter DNA sequences were PCR-amplified and inserted into the linear vector by using the In-Fusion Kit (Clontech, 638909). The Gal-3 reporter vectors contain the elements EF1a-mAG-Gal3-ires-PuroR. MCF7-mAG-Gal3 reporter cells lines were made by transduction of cells with lentiviral particles containing the reporter sequences. After 2 days of lentiviral transduction, cells were selected and maintained in basic culture media supplemented with 1 mg/ml of puromycin.

Phenotypic screening assay to determinate LMP

U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 cells were plated in 96-well plates (12,500 cells/well (39,000 cell/cm2) and cell were allow to attached overnight. The following morning compounds added with a TECAN D300e Digital Dispenser (Hewlett-Packard) in a lineal 1.3x serial dilution form a 20 mM DMSO stock. DMSO was normalized to a final concentration of 0.3%. The cells were incubated for 6 h with the 51 test compounds, siramesine, staurosporine or DMSO (duplicates). After treatment, cells were stained with 27.7 μM Hoechst and 11 μM Calcein-AM, incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Automated live-cell image acquisition was performed on a Thermo Fisher CellInsight™ CX5 High Content Screening (HCS) Reader using a 20x objective. Image analysis was performed using the Spot Detector Bioapplication (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gal-3 relocation (representing damaged lysosomes) was defined as punctate signal (Spots) within an artificially defined circular area centered on each nucleus and was quantified as the “Mean_spot_area_per_cells” in the corresponding channel. A more detailed description of the image acquisition, image analysis and statistical analysis of the data is provided in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Cells were grown on glass cover slips in 24-well plates and treated with the compounds as indicated. Cells were fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with ice cold methanol for 5 min and quenched with 50 mM of NH4Cl/PBS for 10 min. We then apply blocking buffer (PBS 1% BSA) for 1 h following by incubation with primary antibodies anti-Cathepsin D (1:150, R&D Systems Cat#AF1014). After washing 3 times with PBS, we incubated cells 1 h in the dark with secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:400, A-11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell were stained with ProLong Gold Antifade mounting media with DAPI (P36935, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subjected to imaging.

For live-cell confocal images, cells were seeded on 4-well 35 cm glass bottom dish (Greiner Bio One, 627870) to a density of 70,000 cells/well and grown overnight. The following day, cells were treated with compounds or DMSO as indicated, and labelled with 6 μM Hoechst 33342 for nucleus visualization and/or 25 nM of LysoTracker-Red. We incubated for 30 and image cells with an LSM 520 confocal microscope using an Apochromat 63x/1.40 Oil DIC M27 objective and Zen 2010 software (all equipment and software from Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Pinholes were set so that the section thickness was equal for all channels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Harald Wodrich (Laboratoire de Microbiologie Fondamentale et Pathogénicité, Bordeaux, France) for kindly providing the U2OS-mCherry-Gal3 cells. This work was funded in part by …UMC?………., the European Research Council (LYSOSOME), the Danish National Research Foundation (CARD), the Danish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council and the Danish Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

Author Contribution

D.A.E. directed the project. R.J.P. conceived, designed and performed all experiments, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. D.S.D helped to set up reporter cell lines and design special plasmid for this end. D.L. participated in experiment related to HTS and assisted in the automatization of the assays. R.D.P. helped to perform automatic microscopy Gal-3 experiments. M.J. provided several stable cell lines and together with S.A. contributed with their knowledge on LCD to design the screening strategy and in manuscript preparation. N.M. and R.L. participate in the synthesis of Siramesine that was performed by R.J.P. in R.L. laboratory at Utrecht University under the supervision of N.M. J.K. contribute with her knowledge in cell biology, lysosomes and trafficking and support the development of this project.

References

- Aits S, Jaattela M. Lysosomal cell death at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1905–1912. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aits S, Jaattela M, Nylandsted J. Methods for the quantification of lysosomal membrane permeabilization: a hallmark of lysosomal cell death. Methods in cell biology. 2015;126:261–285. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2014.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aits S, Kricker J, Liu B, Ellegaard AM, Hamalisto S, Tvingsholm S, Corcelle-Termeau E, Hogh S, Farkas T, Holm Jonassen A, et al. Sensitive detection of lysosomal membrane permeabilization by lysosomal galectin puncta assay. Autophagy. 2015;11:1408–1424. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1063871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes F, Cadenas E, Brunk UT. Apoptosis induced by exposure to a low steady-state concentration of H2O2 is a consequence of lysosomal rupture. Biochem J. 2001;356:549–555. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelqvist H, Waster P, Kagedal K, Ollinger K. The lysosome: from waste bag to potential therapeutic target. J Mol Cell Biol. 2013;5:214–226. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Attardi LD. The role of apoptosis in cancer development and treatment response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nrc1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenz EJ, Limburg PJ, Howe CL. A high-throughput 3-parameter flow cytometry-based cell death assay. Cytometry A. 2007;71:170–173. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter AE. Image-based chemical screening. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesen MH, Pegan K, Spes A, Turk B. Lysosomal pathways to cell death and their therapeutic applications. Exp Cell Res. 318:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anneo A, Carlisi D, Lauricella M, Puleio R, Martinez R, Di Bella S, Di Marco P, Emanuele S, Di Fiore R, Guercio A, et al. Parthenolide generates reactive oxygen species and autophagy in MDA-MB231 cells. A soluble parthenolide analogue inhibits tumour growth and metastasis in a xenograft model of breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e891. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Astolfo DS, Pagliero RJ, Pras A, Karthaus WR, Clevers H, Prasad V, Lebbink RJ, Rehmann H, Geijsen N. Efficient intracellular delivery of native proteins. Cell. 2015;161:674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C. Lysosomes revisited. Eur J Biochem. 1983;137:391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefanis D, Demoz M, Dragonetti A, Houri JJ, Ogier-Denis E, Codogno P, Baccino FM, Isidoro C. Differentiation-induced changes in the content, secretion, and subcellular distribution of lysosomal cathepsins in the human colon cancer HT-29 cell line. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;289:109–117. doi: 10.1007/s004410050856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards BS, Ivnitski-Steele I, Young SM, Salas VM, Sklar LA. High-throughput cytotoxicity screening by propidium iodide staining. Current protocols in cytometry / editorial board J Paul Robinson, managing editor … [et al.] 2007;Chapter 9:Unit9 24. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0924s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegaard AM, Groth-Pedersen L, Oorschot V, Klumperman J, Kirkegaard T, Nylandsted J, Jaattela M. Sunitinib and SU11652 inhibit acid sphingomyelinase, destabilize lysosomes, and inhibit multidrug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2018–2030. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher N, Bastholm L, Kirkegaard-Sorensen T, Rafn B, Bottzauw T, Nielsen C, Weber E, Shirasawa S, Kallunki T, Jaattela M. Sensitization to the lysosomal cell death pathway by oncogene-induced down-regulation of lysosome-associated membrane proteins 1 and 2. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6623–6633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher N, Jaattela M. Lysosomes as targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2993–2995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Wang T, Zhang S, Shi W, Zhang Y. An optimized SYBR Green I/PI assay for rapid viability assessment and antibiotic susceptibility testing for Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Mitchison TJ, Bender A, Young DW, Tallarico JA. Multi-parameter phenotypic profiling: using cellular effects to characterize small-molecule compounds. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:567–578. doi: 10.1038/nrd2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonrose X, Ausseil F, Soleilhac E, Masson V, David B, Pouny I, Cintrat JC, Rousseau B, Barette C, Massiot G, et al. Parthenolide inhibits tubulin carboxypeptidase activity. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3371–3378. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D, Cedillos R, Choyke S, Lukic Z, McGuire K, Marvin S, Burrage AM, Sudholt S, Rana A, O’Connor C, et al. Alpha-synuclein induces lysosomal rupture and cathepsin dependent reactive oxygen species following endocytosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghantous A, Gali-Muhtasib H, Vuorela H, Saliba NA, Darwiche N. What made sesquiterpene lactones reach cancer clinical trials? Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth-Pedersen L, Aits S, Corcelle-Termeau E, Petersen NH, Nylandsted J, Jaattela M. Identification of cytoskeleton-associated proteins essential for lysosomal stability and survival of human cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth-Pedersen L, Jaattela M. Combating apoptosis and multidrug resistant cancers by targeting lysosomes. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth-Pedersen L, Ostenfeld MS, Hoyer-Hansen M, Nylandsted J, Jaattela M. Vincristine induces dramatic lysosomal changes and sensitizes cancer cells to lysosome-destabilizing siramesine. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2217–2225. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guicciardi ME, Leist M, Gores GJ. Lysosomes in cell death. Oncogene. 2004;23:2881–2890. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Kim H, Kim J, Cho DH, Kim M, Kim YS, Kim Y, Park SJ, Koh JY. Zinc(II) ion mediates tamoxifen-induced autophagy and cell death in MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. BioMetals. 2010;23:997–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaattela M. Multiple cell death pathways as regulators of tumour initiation and progression. Oncogene. 2004;23:2746–2756. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicke RU, Sprengart ML, Wati MR, Porter AG. Caspase-3 is required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9357–9360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallunki T, Olsen OD, Jaattela M. Cancer-associated lysosomal changes: friends or foes? Oncogene. 2013;32:1995–2004. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim LA, Amarnani D, Gnanaguru G, Tseng WA, Vavvas DG, D’Amore PA. Tamoxifen toxicity in cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells is mediated by concurrent regulated cell death mechanisms. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4747–4758. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SL, Liu YC, Seo SY, Kim SH, Kim IH, Lee SO, Lee ST, Kim DG, Kim SW. Parthenolide induces apoptosis in colitis-associated colon cancer, inhibiting NF-kappaB signaling. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2135–2142. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkegaard T, Jaattela M. Lysosomal involvement in cell death and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhuber J, Tripal P, Reichel M, Muhle C, Rhein C, Muehlbacher M, Groemer TW, Gulbins E. Functional Inhibitors of Acid Sphingomyelinase (FIASMAs): a novel pharmacological group of drugs with broad clinical applications. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;26:9–20. doi: 10.1159/000315101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhuber J, Tripal P, Reichel M, Terfloth L, Bleich S, Wiltfang J, Gulbins E. Identification of new functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase using a structure-property-activity relation model. J Med Chem. 2008;51:219–237. doi: 10.1021/jm070524a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuger MR, Grootjans S, Biavatti MW, Vandenabeele P, D’Herde K. Sesquiterpene lactones as drugs with multiple targets in cancer treatment: focus on parthenolide. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:883–896. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328356cad9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Jaattela M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:886–897. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux B, Percival MD, Falgueyret JP. Quantitation of the lysosomotropic character of cationic amphiphilic drugs using the fluorescent basic amine Red DND-99. Analytical biochemistry. 2004;327:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio JP, Pryor PR, Bright NA. Lysosomes: fusion and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:622–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima I, Takahashi A, Omori H, Kimura T, Takabatake Y, Saitoh T, Yamamoto A, Hamasaki M, Noda T, Isaka Y, et al. Autophagy sequesters damaged lysosomes to control lysosomal biogenesis and kidney injury. EMBO J. 2013;32:2336–2347. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier O, Marvin SA, Wodrich H, Campbell EM, Wiethoff CM. Spatiotemporal dynamics of adenovirus membrane rupture and endosomal escape. J Virol. 2012;86:10821–10828. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01428-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MM, Sloane BF. Cysteine cathepsins: multifunctional enzymes in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:764–775. doi: 10.1038/nrc1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama Y, Takano T, Ohkuma S. Acridine orange as a fluorescent probe for lysosomal proton pump. J Biochem. 1982;92:1333–1336. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrschtik M, Ryan KM. Lysosomal proteins in cell death and autophagy. FEBS J. 2015;282:1858–1870. doi: 10.1111/febs.13253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadanaciva S, Lu S, Gebhard DF, Jessen BA, Pennie WD, Will Y. A high content screening assay for identifying lysosomotropic compounds. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011;25:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostenfeld MS, Fehrenbacher N, Hoyer-Hansen M, Thomsen C, Farkas T, Jaattela M. Effective tumor cell death by sigma-2 receptor ligand siramesine involves lysosomal leakage and oxidative stress. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8975–8983. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostenfeld MS, Hoyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Fehrenbacher N, Olsen OD, Groth-Pedersen L, Puustinen P, Kirkegaard-Sorensen T, Nylandsted J, Farkas T, et al. Anti-cancer agent siramesine is a lysosomotropic detergent that induces cytoprotective autophagosome accumulation. Autophagy. 2008;4:487–499. doi: 10.4161/auto.5774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz I, Sachse M, Dupont N, Mounier J, Cederfur C, Enninga J, Leffler H, Poirier F, Prevost MC, Lafont F, et al. Galectin-3, a marker for vacuole lysis by invasive pathogens. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:530–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perregaard J, Moltzen EK, Meier E, Sanchez C .sigma. Ligands with Subnanomolar Affinity and Preference for the .sigma.2 Binding Site. 1. 3-(.omega.-Aminoalkyl)-1H-indoles. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1995;38:1998–2008. doi: 10.1021/jm00011a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen NH, Olsen OD, Groth-Pedersen L, Ellegaard AM, Bilgin M, Redmer S, Ostenfeld MS, Ulanet D, Dovmark TH, Lonborg A, et al. Transformation-associated changes in sphingolipid metabolism sensitize cells to lysosomal cell death induced by inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinheckel T, Deussing J, Roth W, Peters C. Towards specific functions of lysosomal cysteine peptidases: phenotypes of mice deficient for cathepsin B or cathepsin L. Biol Chem. 2001;382:735–741. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider N, Ludwig H, Nick P. Suppression of tubulin detyrosination by parthenolide recruits the plant-specific kinesin KCH to cortical microtubules. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:2001–2011. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M, Nielsen O. L A/S, editor. Methods for manufacture of dihydroisobenzofuran derivatives. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Stoka V, Turk V, Turk B. Lysosomal cysteine cathepsins: signaling pathways in apoptosis. Biol Chem. 2007;388:555–560. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhai MA, Prabha S, Hurren R, Rutledge AC, Lee AY, Sriskanthadevan S, Sun H, Wang X, Skrtic M, Seneviratne A, et al. Lysosomal disruption preferentially targets acute myeloid leukemia cells and progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:315–328. doi: 10.1172/JCI64180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston TL, Wandel MP, von Muhlinen N, Foeglein A, Randow F. Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion. Nature. 2012;482:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiuman TS, Ueda-Nakamura T, Garcia Cortez DA, Dias Filho BP, Morgado-Diaz JA, de Souza W, Nakamura CV. Antileishmanial activity of parthenolide, a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Tanacetum parthenium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:176–182. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.176-182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Francies HE, Francis JM, Bounova G, Iorio F, Pronk A, van Houdt W, van Gorp J, Taylor-Weiner A, Kester L, et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell. 2015;161:933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma H, Gangadhar NM, Letso RR, Wolpaw AJ, Sriramaratnam R, Stockwell BR. Identification of a small molecule that induces ATG5-and-cathepsin-l-dependent cell death and modulates polyglutamine toxicity. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1759–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrebska A, Gach K, Janecka A. Combined effect of parthenolide and various anti-cancer drugs or anticancer candidate substances on malignant cells in vitro and in vivo. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2014;14:222–228. doi: 10.2174/1389557514666140219113509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP, Wang X. Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science. 1997;275:1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong D, Haag P, Yakymovych I, Lewensohn R, Viktorsson K. Chemosensitization by phenothiazines in human lung cancer cells: impaired resolution of gammaH2AX and increased oxidative stress elicit apoptosis associated with lysosomal expansion and intense vacuolation. Cell death & disease. 2011;2:e181. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong D, Zielinska-Chomej K, Juntti T, Mork B, Lewensohn R, Haag P, Viktorsson K. Harnessing the lysosome-dependent antitumor activity of phenothiazines in human small cell lung cancer. Cell death & disease. 2014;5:e1111. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.