Abstract

Antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) containing pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimers are being evaluated clinically in both hematological and solid tumors. These include ADCT-301 (camidanlumab tesirine) and ADCT-402 (loncastuximab tesirine) in pivotal Phase 2 trials that contain the payload tesirine which releases the PBD dimer warhead SG3199. An important consideration in future clinical development is acquired resistance. The aim was to generate and characterize PBD acquired resistant cell lines in both a hematological and solid tumor setting.

Human Karpas-299 (ACLC) and NCI-N87 (gastric cancer) cells were incubated with increasing IC50 doses of ADC (targeting CD25 and HER2, respectively) or SG3199 in a pulsed manner until stable acquired resistance was established. The level of resistance achieved was ~3000-fold for ADCT-301 and 3-fold for SG3199 in Karpas-299, and 8-fold for ADCT-502 and 4-fold for SG3199 in NCI-N87. Cross-resistance between ADC and SG3199, and with an alternative PBD-containing ADC or PBD dimer was observed.

The acquired resistant lines produced fewer DNA interstrand cross-links indicating an up-stream mechanism of resistance. Loss of antibody binding or internalisation was not observed. A human drug-transporter PCR Array revealed several genes upregulated in all the resistant cell lines including ABCG2 and ABCC2, but not ABCB1(MDR1). These findings were confirmed by RT-PCR and western blot, and inhibitors and siRNA knockdown of ABCG2 and ABCC2 recovered drug sensitivity.

These data show that acquired resistance to PBD-ADCs and SG3199 can involve specific ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug transporters. This has clinical implications as potential biomarkers of resistance and for the rational design of drug combinations.

Keywords: Acquired drug resistance, PBD dimer, antibody-drug conjugate, ABC transporter

Introduction

The increasing interest in pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimers as warheads for antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) over the last decade has resulted in numerous clinical trials of PBD dimer-based ADCs in both solid and hematological tumors [1]. For example, ADCT-402 (loncastuximab tesirine) [2] and ADCT-301 (camidanlumab tesirine) [3] are currently in pivotal phase 2 trials in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) and Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL), respectively [1].

As PBD-dimer based ADCs progress through clinical development, the long-term success of these drugs will depend on understanding and overcoming the potential development of acquired resistance, which due to the small molecule-antibody conjugate composition and multi-stage mechanism of action of ADCs can be complex, as cells have multiple opportunities to resist the ADC [4]. Both pre-clinical and clinical studies have been carried out on currently approved ADCs and the mechanism of acquired resistance generally falls into two major categories; related to the antibody portion of the ADC, or related to the drug/drug-linker portion of the ADC [5]. Tumor cells that have become refractory to monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy often show downregulation of the target antigen or impaired mAb-antigen complex internalisation [6], a resistance mechanism that has also been reported with trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) [7, 8], brentuximab vedotin (BV) [9] and gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) [10].

Should the binding and internalisation of the ADC not be significantly affected, acquired resistance to the small drug molecule released inside the tumor cell can develop due to upregulation of drug efflux pumps, upregulation of cellular repair mechanisms associated with the drugs mechanism of action, or prevention of apoptosis [11, 12]. The membrane bound drug transporter P-glycoprotein (MDR1, ABCB1) is one of the most commonly upregulated efflux pumps associated with small molecule drug resistance [13], as well as other members of the ABC transporter family [14, 15]. Indeed, MDR1 has been implicated in the resistance to T-DM1, GO and inotuzumab ozogamicin [7, 16]. The PBD dimer SJG-136 (SG2000, Figure 1) has been shown to be a weak substrate for MDR1 so it is possible that the upregulation of this transporter could play a role in acquired resistance to PBD dimer-based ADCs [17].

Figure 1. The generation of cell lines with acquired resistance to PBD dimer or PBD dimer-based ADCs.

A. General structure of the PBD dimer warheads SG3199 and SG2000, antibody-drug conjugates containing the drug-linker tesirine (ADCT-301, ADCT-502), and SG3560. B. Continuous exposure in vitro growth inhibition of wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with target ADC and PBD dimer. C. Interstrand cross-link formation of wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with target ADC and PBD dimer (Karpas: 130 pM ADCT-301, 280 pM SG3199; NCI-N97: 1 nM ADCT-502, 1.7 nM SG3199). D. Continuous exposure in vitro growth inhibition of wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with SG3560 ADCs and SG2000. Each data point represents the average of at least 3 biological repeats with +/- SD error bars. p-values obtained using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests.

The mechanism of action of the PBD dimers involves the rapid formation of persistent DNA interstrand cross-links (ICLs) in the minor grove of the DNA, causing stalled replication forks and triggering apoptosis during cell division [18]. Repair of ICLs is complex and can involve a combination of repair mechanisms including nucleotide excision repair (NER) and homologous recombination (HR) [19]. Increased repair (unhooking) of DNA ICLs has been observed as a mechanism of clinical acquired resistance to conventional DNA cross-linking agents including melphalan in myeloma [20] and cisplatin in ovarian cancer [21]. However, the nature of the PBD dimer ICL, causing minimal distortion of the DNA structure, and its resulting persistence in cells, suggests that it may be refractory to some DNA repair mechanisms [22].

From a clinical perspective, it is important to understand the mechanisms by which some tumor cells may have inherent sensitivity to, or following treatment, may develop acquired resistance to, PBD dimer-based ADCs. This could result in predictive biomarkers for response to the ADC or the development of rational combination strategies. In this study, two ADCs containing the cathepsin cleavable drug-linker tesirine (Figure 1), which upon cleavage from the N-10 position releases the PBD dimer SG3199 (Figure 1) were used to generate cell lines with acquired resistance. One ADC, targeting CD25, was used to develop resistance in a hematological cancer setting, the other, targeting HER2 in a solid tumor setting. In parallel, resistant cell lines were also generated to the free warhead SG3199 [23]. Our findings show that specific ABC transporter upregulation was conserved across tumor model and ADC or naked PBD dimer resistance. The results also suggest potential treatment strategies of overcoming the resistance with the use of appropriate transporter inhibitors.

Materials And Methods

Cell lines and reagents

The Karpas-299 (ALCL) cell line was purchased from The European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC), and the NCI-N87 (Gastric carcinoma) cell line was purchased from the ATCC, both authenticate their cell lines using short tandem repeat DNA typing. Both wt and all resistant cells were grown in RPMI-1640 (ThermoFisher) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS (ThermoFisher) and 2 mmol/L glutamine (Sigma). All cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a humidified with a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The ADCs ADCT-301 [3], ADCT-502 [24], PBD dimer SG3199 [23] and the CD25 specific antibody HuMax-TAC were provided by ADC Therapeutics. Trastuzumab was obtained from Roche.

Resistant cell line generation

Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 cells were incubated with IC50 concentrations of ADC or PBD dimer (3 days Karpas, 6 days NCI-N87) followed by recovery without treatment, until normal cell growth had returned. This method was intended to simulate the chronic, multicycle dosing strategy used for cytotoxic therapeutics in the clinic. The resistance of the cells was monitored every month using the MTS assay and the dose of drug adjusted to match the new IC50 as the cells became increasingly resistant after multiple treatment cycles.

In vitro growth inhibition

10,000 cells per well were seeded in a flat bottom 96-well plate, and NCI-N87 cell were incubated overnight before treatment. For ADC growth inhibition assays, cells were then incubated with serial dilutions of ADCT-301 or ADCT-502 in triplicate. For the SG3199 growth inhibition assays, cells were mixed with a serial dilution of SG3199 in DMSO before seeding. Growth inhibition was measured after 96 hours in Karpas-299 cells and 144 hours in NCI-N87 cells using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One MTS Solution (Promega), and absorbance measured on a Multiskan Ascent plate reader (ThermoFisher) at 492 nm. Growth inhibition was calculated as a percentage of absorbance compared to an untreated control, and IC50 values were calculated using the sigmoidal, 4PL, X is log(concentration) equation in GraphPad Prism. For drug transporter inhibitor combination cytotox, the resistant cell lines were incubated overnight with either 5 μM MK-571 (ABCC2 inhibitor, Abcam), 10 μM FTC (ABCG2 inhibitor, Sigma), 5 μM Reversin-121 (ABCB1 inhibitor, Cayman Chemical) or 10 nM Lovastatin (SLCO2B1 inhibitor, Abcam) overnight before carrying out the ADC or PBD growth inhibition assay as previously described.

Single cell gel electrophoresis (comet) assay

The formation of DNA interstrand cross-links (ICLs) by either ADCT-301, ADCT-502 or SG3199 was measured using a modification of the single cell gel electrophoresis (comet) assay. The comet assay was carried out according to the protocol described previously [25]. Cells were treated with 130 pM ADCT-301 or 280 pM SG3199 (Karpas-299), or 1 nM ADCT-502 or 1.7 nM SG3199 (NCI-N87) for 2 hours, then washed and incubated for 24 hours under normal cell culture conditions. All cells were irradiated with 18 Gy (5Gy/min for 3.6 min). ICL formation was quantitated by measuring Olive tail moment (OTM) using the Komet 6 software (Andor Technology, Belfast, UK) and the percentage reduction in OTM calculated according to the formula:

TMdi= Tail Moment drug irradiated; TMcu= TM control un-irradiated; TMci = TM control irradiated

Antibody binding and internalisation

Parental and resistant cells (1.5 x105) were blocked on ice for 30 minutes before incubation with a serial dilution of trastuzumab or HuMax-TAC for 1 hour on ice in triplicate. The cells were washed and incubated with a F(ab’)2-goat anti-human IgG Fc-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (ThermoFisher) 1:50 in blocking buffer. After incubation for 1 hour on ice in the dark, cells were washed and processed on a Fortessa X20 flow cytometer, and the MFI measured using the B530/30 laser/filter.

Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 parental and resistant cells were seeded in a poly-L-ornithine coated 96-well plate and allowed to attach at 37 °C. HuMax-TAC or trastuzumab was incubated with a 3 X molar excess of FabFluor pH red antibody internalisation reagent (Essen Bioscience) for 15 minutes at room temperature, then a 3-fold serial dilution set up with cell culture medium. The labelled antibody dilutions were added to the cells, and images taken at 10x magnification every 2 hours with phase contrast and red fluorescence filters in an IncuCyte Zoom (Essen BioScience). Mean red object area per well was calculated using the IncuCyte Zoom software.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR assays

Total RNA was extracted from Karpas-299 or NCI-N87 wt and resistant cells, and purified with the RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen). The real-time RT2 Profiler PCR Array for human drug-transporters or DNA damage signaling (Qiagen) were used to probe cDNA generated from Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 resistant and parental cell line lysates. CT values were normalized based on a panel of housekeeping genes (HKG). The Qiagen data analysis web portal calculated fold change/regulation using ΔΔ CT method, in which Δ CT was calculated between gene of interest (GOI) and an average of HKGs, followed by ΔΔ CT calculations (Δ CT (Test Group)- Δ CT (Control Group)). Fold change was then calculated using 2^ (-ΔΔ CT) formula. For confirmation of gene upregulation, qRT-PCR was performed using TaqMan gene expression probes (LifeTech) for the drug transporter of choice or the housekeeping gene ABL-1, and fold change/regulation calculated using ΔΔ CT method as described above.

Immunoblot analysis

1.5 - 2 x106 cell lysates were collected in lysis buffer (0.0625 M Tris-HCL, 2 % SDS, 10% glycerol). Protein concentrations were determined with the DC™ Protein Estimation Assay (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein (20-30 μg) was loaded into a 4-15 % Mini-PROTEAN® TGX gel (BioRad), and transferred onto a 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad), followed by primary and secondary antibody incubation. The following antibodies were used: rabbit monoclonal anti-ABCC2 (Cell Signalling), rabbit monoclonal anti-ABCG2 (Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-Calnexin (Cell Signalling), and goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signalling). Secondary antibody was detected using the ECL detection kit (Amersham).

siRNA knockdown

Silencer® Select siRNA oligonucleotides targeting ABCC2 and nontargeting siRNAs were purchased from Ambion/ThermoFisher. For reverse transfection, Opti-MEM medium was mixed with siRNA to give a final concentration of 25 pmol/L, this was then combined with diluted Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX (Thermo Scientific). After 20-minute incubation at room temperature, the transfection mixture was aliquoted into 6-well plates. Cells were added to each well containing siRNA and RNAiMAX complex. 48 hours after transfection, cells were harvested and used for immunoblotting or growth inhibition assays as previously described.

Results

Generation of PBD-ADC and PBD dimer acquired resistant cell lines

IC50 growth inhibition concentrations of the parental cell lines to either the target ADC (Karpas-299: 1.5 ng/mL ADCT-301, NCI-N87: 1.3 ng/mL ADCT-502) or SG3199 (Karpas-299: 70 pM, NCI-N87: 15.9 pM) were established using the MTS assay (Table 1). Cells were incubated with the IC50 concentration of drug for approximately the time required for three cell divisions, then washed and allowed to recover in drug-free medium until normal cell proliferation was restored. This process was repeated over a period of 12-18 months, growth monitored and the dose of ADC or PBD dimer increased to mirror the increase in IC50. This pulsatile approach resulted in the generation of cell lines with an acquired resistance that was stable for multiple passages in the absence of any drug.

Table 1. IC50 values and fold resistance of Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 resistant cell lines to PBD dimer and PBD dimer-based ADCs.

| Cell line | IC50 (fold resistance) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADCT-301 ng/mL | ADCT-502 ng/mL | SG3199 pM | SG2000 nM | mAb-SG3560 ng/mL | |

| Karpas wt | 1.5 | - | 70 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Karpas ADCr | ~5000 (~3333) | - | 306.5 (4.4) | 2.8 (3.1) | >10,000 (>7692) |

| Karpas PBDr | 72.8 (48.5) | - | 204.5 (2.9) | 4.7 (5.2) | >10,000 (>7692) |

| NCI-N87 wt | - | 1.3 | 15.9 | 0.06 | 1.0 |

| NCI-N87 ADCr | - | 9.9 (7.6) | 60.4 (3.8) | 0.46 (7.7) | 95 (95) |

| NCI-N87 PBDr | - | 7.2 (5.5) | 58.6 (3.7) | 0.47 (7.8) | 54 (54) |

Growth inhibition assays showed an increase in the IC50 values in all the cell lines made resistance to either ADC (ADCr) or PBD dimer (PBDr) ranging from 2.9-fold to >3000 fold (Figure 1B, Table 1). Interestingly, the cell lines made resistant to ADC were also found to be cross-resistant to SG3199 and the cell lines made resistant to SG3199 were cross-resistant to ADC (Figure 1B, Table 1).

Reduced DNA ICL formation in resistant cells

Since the mechanism of action of PBD dimers involves the formation of DNA ICLs, a modification of the single cell gel electrophoresis (comet) assay was used to measure the amount of ICL formation following a single dose of either ADC or PBD dimer. All the cell lines were treated with a dose previously found to give an approximate 50% reduction in OTM in the parental cell lines after a 2-hour drug exposure, followed by 24-hour drug free incubation (Karpas: 130 pM ADCT-301, 280 pM SG3199; NCI-N87: 1 nM ADCT-502, 1.7 nM SG3199). The comet assays showed a significant reduction in DNA ICL formation in Karpas ADCr cells treated with ADCT-301 (53.5% to 15% reduction in OTM, p-value 0.0004), Karpas PBDr cells treated with SG3199 (55.5% to 25.7%, p-value 0.003), NCI-N87 ADCr cells treated with ADCT-502 (54.7% to 29%, p-value 0.004) and NCI-N87 PBDr cells treated with SG3199 (51% to 30.7%, p-value 0.004) (Figure 1C). In addition, consistent with the IC50 data, the level of DNA ICL formation was also significantly reduced in the ADCr cell lines treated with SG3199 and PBDr cell lines treated with ADC (Figure 1B). These data suggest mechanisms of resistance in all four of the cell lines which prevent the formation of DNA damage.

Cross-resistance to other PBD-containing ADCs and DNA-interacting drugs

To further investigate the cross-resistance in the four cell lines, growth inhibition was compared with the parental cell line when treated with the structurally similar, but less potent, PBD dimer SG2000, and a C2-linked PBD dimer-based ADC (SG3560) (Figure 1A). The cell lines were cross-resistant to both SG2000 and the SG3560-based ADCs (Figure 1D). Comparing the IC50 values to the parental cells showed similar levels of resistance to SG2000 to those seen with SG3199 (Table 1). In contrast, the level of resistance to the C2-linked SG3560 ADCs was greater than with the N10-linked (tesirine) ADCs. Indeed, no growth inhibition was seen in the Karpas-299 resistant cells following treatment with the C2-linked SG3560 ADC at the concentrations tested (Figure 1D). The shift in IC50 was also much greater than with the N10-linked ADC in the NCI-N87 ADCr (95-fold versus 7.6-fold) and NCI-N87 PBDr cells (54-fold versus 3.7-fold, Table 1).

Cross-resistance to three conventional DNA-interacting chemotherapeutic drugs, cisplatin, doxorubicin and melphalan was also measured using the MTS assay in all resistant cell lines. No cross-resistance was seen between any of these drugs in either the Karpas-299 ADCr or PBDr cell lines (Supplementary Figure 1). In contrast, there was a decrease in growth inhibition in both NCI-N87 ADCr and PBDr cells treated with all three of these drugs compared to the parental cell line (Supplementary Figure 1).

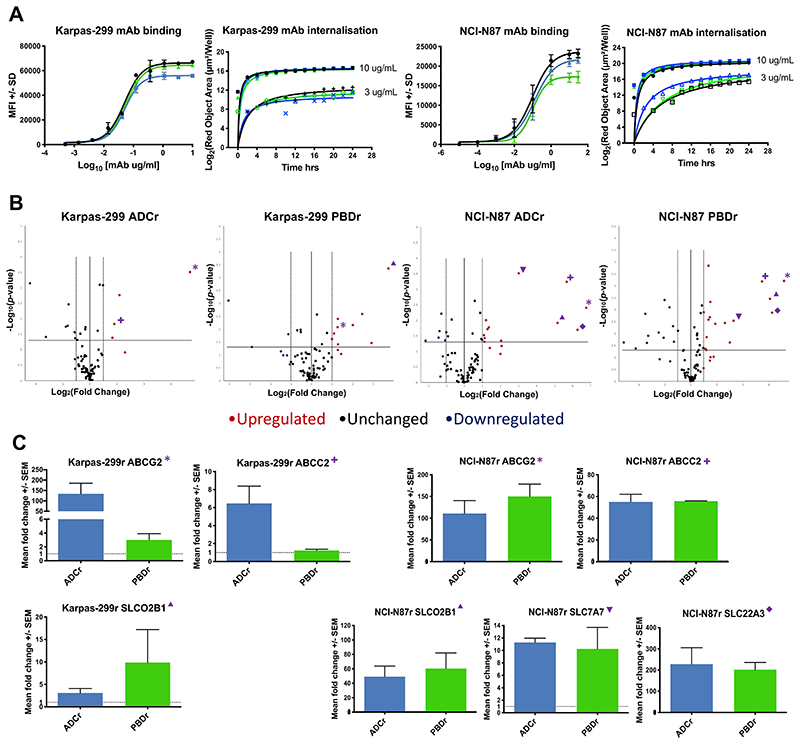

Cell surface antigen expression, binding and internalisation

Since resistance to antibody-based therapies can arise from modified cell surface antigen expression, CD25 or HER2 expression and antibody binding affinity were compared in resistant versus parental cells by flow cytometry, and internalisation kinetics and lysosomal trafficking by the IncuCyte internalisation assay. There was a small decrease in the maximum fluorescence intensity (MFI) reached by the Karpas-299 ADCr cells compared to the PBDr and parental cell lines (Figure 2A), however all cells continued to express high levels of antigen. In the NCI-N87 cell lines there was a small decrease in MFI reached by the PBDr cell line, but the ADCr cell line was unchanged compared to the parental line (Figure 2A). The internalisation kinetics for HuMax-TAC or trastuzumab were unchanged in the resistant cell lines treated with 10 or 0.3 μg/mL of antibody over a 24 hours period (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Investigating the mechanism of PBD and PBD-based ADC acquired resistance in Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 cells.

A. Surface antigen expression and binding of unconjugated mAb (HuMax-TAC or trastuzumab) by flow cytometry, and lysosomal internalisation kinetics of 10 and 0.3 μg/mL unconjugated mAb by IncuCyte pHAb internalisation assay. B. Qiagen RT2 human drug transporter PCR array of Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 ADC and PBD resistant cell lines. C. qRT-PCR confirmation of commonly upregulated transporter genes using TaqMan probes in Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 ADC and PBD resistant cell lines. Each data point represents the average of at least 3 biological repeats with +/- SD error bars, or SEM in the RT-PCR. *: ABCG2; +: ABCC2; ▴: SLCO2B1; ▾: SLC7A7; ♦: SLC22A3.

Changes in gene expression in ADCr and PBDr cell lines

Another possible mechanism of resistance upstream of the DNA ICL formation is that the PBD dimer molecules are being actively effluxed out of the cells when they are either released by ADC metabolism, or they have entered into the cell as stand-alone agents. To investigate this potential pathway of drug resistance, RT2 PCR arrays (Qiagen) were carried out comparing the gene expression of 82 known human drug transporter genes in the resistant versus parental cell lines. Volcano plots generated by the online analysis software showed a number of genes to be significantly upregulated (>2-fold change, p-value <0.05) in the four acquired resistant cell lines (Figure 2B).

Interestingly, ABCG2 was significantly upregulated in the Karpas ADCr, Karpas PBDr, NCI-N87 ADCr and NCI-N87 PBDr cell lines (Fold change and p values shown in Table 2). ABCC2 was also upregulated in the Karpas ADCr, NCI-N87 ADCr and NCI-N87 PBDr cells. SLCO2B1 was upregulated in the Karpas PBDr cells, NCI-N87 ADCr and NCI-N87 PBDr cells. The drug transporter genes SLC22A3 and SLC7A7 were significantly upregulated only in the NCI-N87 ADCr and NCI-N87 PBDr cell lines (Table 2).

Table 2. Human drug transporter gene upregulation in Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 resistant cell lines by RT2 PCR array and TaqMan probe qRT-PCR analysis.

| Transporter gene | Fold change (p-value/SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karpas ADCr | Karpas PBDr | NCI ADCr | NCI PBDr | |||||

| RT2 | Taq | RT2 | Taq | RT2 | Taq | RT2 | Taq | |

| ABCG2 | 167.5 (0.0003) | 134 (87) | 2.4 (0.008) | 3 (1.5) | 107 (0.004) | 111 (51) | 144.4 (0.00006) | 150 (40) |

| ABCC2 | 3.5 (0.01) | 6.5 (3.3) | - | 1 (0.2) | 50.95 (0.0005) | 55 (12) | 44.8 (0.00006) | 56 (0.2) |

| SLCO2B1 | - | 3.1 (1.4) | 13.31 (0.00004) | 9.8 (10.9) | 35.87 (0.01) | 49 (25) | 66.8 (0.0003) | 60 (37) |

| SLC22A3 | - | - | - | - | 77.38 (0.02) | 220 (134) | 77.1 (0.001) | 201 (48) |

| SLC7A7 | - | - | - | - | 8.08 (0.0003) | 11 (1.1) | 9.9 (0.002) | 10 (4.8) |

The upregulation of drug transporter genes ABCG2, ABCC2, SLCO2B1, SLC22A3 and SLC7A7 in the resistant lines compared to the parental cells was confirmed in all cases by RT-PCR using TaqMan probes (Figure 2C). All the genes tested were found to be upregulated in close agreement to the RT2-PCR array (Fold change and SD in Table 2). ABCG2 and SLCO2B1 were upregulated in all four resistant cell lines, while ABCC2 was upregulated in all lines except the Karpas-299 PBDr cells and SLC22A3 and SLC7A7 were both upregulated in the two solid tumor cell lines.

In contrast to the results obtained with the human drug transporter gene array, an RT2 PCR array for DNA damage signaling pathway showed no significantly upregulated genes in any of the acquired resistant lines (Supplementary Figure 2). Overall, the data are consistent with the mechanism of resistance being upstream of the DNA damage produced by the PBD dimer.

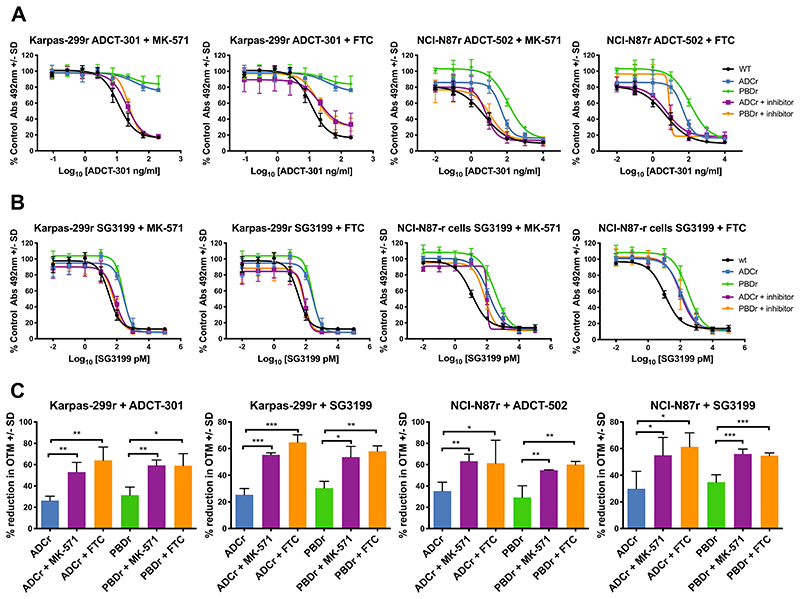

Reversal of resistance by ABC transporter inhibitors

In order to investigate further the contribution of ABC drug transporter upregulation in the acquired resistance to the PBD dimer and PBD dimer-based ADC resistant cell lines, inhibitors of ABCG2 (Fumitremorgin C, FTC) and ABCC2 (MK-571) were used in combination with the ADC or PBD dimer to assess the effect on growth inhibition using the MTS assay. Karpas and NCI-N87 resistant cells were treated with a non-toxic dose of MK-571 (5 μM) or FTC (10 μM) for 24 hours before the addition of the ADC or PBD dimer. Both MK-571 and FTC showed a dramatic re-sensitisation of Karpas-299 ADCr and PBDr cells to ADCT-301 treatment (Figure 3A). Similarly, in the NCI-N87 ADCr and PBDr cells treated with either MK-571 or FTC the response to ADCT-502 was restored to the level of the parental cell line (Figure 3A). Restoration of sensitivity was observed when the ABC transporter inhibitors were combined with SG3199 in Karpas ADCr and PBDr cells (Figure 3B). Lovastatin, an inhibitor of SLCO2B1, however failed to reverse the resistance in any of the cell lines (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 3. Reversing the acquired PBD or PBD-based ADC resistance with ABC drug transporter inhibitors.

A. Continuous exposure in vitro growth inhibition of Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with target ADC and either 5 μM MK-571 or 10 μM FTC. B. Continuous exposure in vitro growth inhibition of Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with SG3199 and either 5 μM MK-571 or 10 μM FTC. C. Interstrand cross-link formation in Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with target ADC or SG3199 (Karpas: 130 pM ADCT-301, 280 pM SG3199; NCI-N97: 1 nM ADCT-502, 1.7 nM SG3199) and either 5 μM MK-571 or 10 μM FTC. Each data point represents the average of at least 3 biological repeats with +/- SD error bars. p-values obtained using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests.

In order to correlate the inhibition of the ABC transporters with the reversal of ADC and PBD dimer resistance mechanistically, the comet assay was used to measure DNA ICL formation in the resistant cell lines by the ADC or PBD dimer pre-treated with either 5 μM MK-571 or 10 μM FTC. In all the resistant cell lines, treatment with transporter inhibitor resulted in increased formation of ADC or PBD-induced DNA interstrand cross-linking. These data are consistent with increased retention of PBD dimer in cells resulting in increased DNA damage and resultant cytotoxicity.

Protein analysis of ABC transporters and siRNA knockout of ABCC2

The two drug transporters with the most consistent mRNA upregulation across the resistant cell lines, which also responded to appropriate transporter inhibition to restore drug sensitivity were ABCG2 and ABCC2. Immunoblotting showed the ABCG2 protein to be upregulated in the Karpas-299 ADCr cells compared to the parental cell line, while any upregulation in PBDr cells could not be detected (Figure 4A). This reflects the very different levels of upregulation observed by PCR in these cells. Despite numerous attempts, ABCC2 protein could not be observed by immunoblotting in either parental nor the resistant Karpas-299 cells. In the NCI-N87 resistant cell line immunoblots, both ABCC2 and ABCG2 were both clearly upregulated compared to the parental cell line (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. ABC transporter immunoblots and ABCC2 siRNA knockdown reversed resistance in NCI-N87 resistant cells.

A. Representative western blot for ABCC2 and ABCG2 in Karpas-299 and NCI-N87 wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines. B. Representative western blot for ABCC2 NCI-N87 ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with siRNA against ABCC2 or scramble control. C. ABCC2 siRNA knockdown continuous exposure in vitro growth inhibition of NCI-N87 wt, ADC and PBD resistant cell lines with ADCT-502 or SG3199. Each data point represents the average of at least 3 biological repeats with +/- SD error bars.

NCI-N87 cells were transfected with siRNA against ABCC2 and ABCG2. ABCG2 was not able to be effectively knocked out due to the very long half-life of the protein (Supplementary Figure 4), but ABCC2 was successfully depleted in both NCI-N87 ADCr and PBDr cells compared with a non-target siRNA control (Figure 4B). The depletion of ABCC2 in the NCI-N87 ADCr and PBDr cells was able to restore cytotoxic sensitivity to ADCT-502 and SG3199 to the level of the parental cell line (Figure 4C), further implicating ABCC2 in the mechanism of acquired resistance in these cell lines.

Discussion

Understanding the acquired resistance of antibody-drug conjugates is not straightforward due to their multi-step mechanism of action, and multiple routes exist for the cells to avoid and escape drug-initiated apoptosis [4]. We have shown that it is possible to generate cell lines with stable acquired resistance to the highly potent PBD dimer SG3199 and also to ADCs that release SG3199 as their warhead. In this study, two human cell lines, one hematological background (Karpas-299, ALCL) and one solid tumor background (NCI-N87, gastric) were made resistant to either a PBD dimer-based ADC or SG3199. All four acquired resistant cell lines were fully characterised to understand the mechanism of resistance and a conserved upregulation of specific ABC drug transporters was observed which was reversed by appropriate ABC transporter inhibitors, or siRNA.

The Karpas-299 cell lines were significantly more resistant to ADCT-301 than SG3199, therefore, the hypothesis was that more than one mechanism of resistance could be present. One of the most common ways of cells to become resistant to an antibody-based therapy is the loss of antigen expression, or epitope modification, to prevent antibody binding and internalisation or signaling [6]. This mechanism has not only been seen with naked antibody therapy, but also with ADCs in vitro and clinically [7–9]. Our study showed that the binding and subsequent internalisation of the CD25 and HER2 antibodies was not affected in the acquired resistant cell lines and the apparent affinity of the antibody to all the cell lines was unchanged. Although there was a small drop in maximum binding of HuMax-TAC to the Karpas-299 ADCr cells, this could not account for the significant loss of growth inhibition seen with ADCT-301, or the cross-resistance observed to SG3199. Internalisation assays confirmed that, in all cases, the antibody was internalised into the lysosomes, a process which is essential for ADC linker cleavage to release the cytotoxic warhead.

Importantly, the acquired resistant cell lines were not only resistant to the PBD dimer or ADC to which they were treated during establishment, but they were also cross-resistant. This overlap in the profile of the drug-resistance generated suggested an overlapping mechanism of resistance across the different cell lines. Indeed, all the resistant cell lines also showed a decrease in DNA ICL formation when treated with the ADC or PBD dimer compared to the parental cell lines, which indicated that the mechanism of resistance is upstream of DNA ICL formation, and not a downstream DNA repair or apoptosis signaling evasion mechanism.

Consistent with an upstream mechanism of resistance, the human drug transporter PCR array performed on all the cell lines showed that specific drug transporters were upregulated in all of the cell lines, and this was corroborated by qRT-PCR. In contrast, DNA damage signaling pathway arrays did not reveal any significant upregulation that would be relevant to PBD dimer resistance. Previously, changes in expression of specific DNA damage signaling genes have been observed following treatment of cells with conventional DNA cross-linking agents such as melphalan or cisplatin [26], and specific DNA repair proteins such as ERCC1 have been found to be upregulated in cells with acquired resistance to cisplatin [27, 28]. DNA ICLs produced by PBD dimers persist compared to those produced by conventional DNA cross-linking agents [23] which is likely due to poor recognition by DNA repair and damage response proteins, however the XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease and homologous recombination have been shown to contribute to the ultimate repair of the minor groove ICLs produced by PBD dimers including SG3199 [29].

Two members of the ABC transporter family, ABCC2 and ABCG2, were significantly upregulated in the acquired resistance cell lines, and inhibitors to these two transporters recovered the cytotoxic sensitivity of the cells to the ADCs and SG3199. The NCI-N87 cells did not respond as well to the inhibitors in the PBD assay, most likely due to the inability to pre-treat the NCI-N87 cells with inhibitors before SG3199 addition. The ABC inhibitors induced a restoration of DNA ICL formation to levels seen in the parental cell lines. ABCC2 (multi-drug resistance protein 2, MRP2) and ABCG2 (breast cancer resistance protein, BCRP) have been widely implicated in chemotherapy resistance [12, 30]. Interestingly, ABCB1 (MDR1, P-glycoprotein 1) was not significantly upregulated in any of the resistant cell lines. Previously, SG3199 was found to be moderately susceptible to multidrug resistance mechanisms when compared in human tumor cell lines non-expressing or expressing MDR1 and the inhibitor verapamil was able to reverse the resistance [23]. Members of the SLC transporter family were also upregulated in some of the acquired cell lines. Lovastatin, an SLC transporter inhibitor did not reverse the resistance suggesting that these transporters are unlikely to be key in the resistance mechanism. SLC transporters mediate the influx of drugs into cells [31], therefore, it would be interesting to investigate any downregulated SLC genes, which could play a role in a resistance phenotype by reducing the bystander effect known to play a role in PBD-ADC cytotoxicity [32].

In addition to cross-resistance between the ADCs used for establishment of the resistant lines and SG3199, cross-resistance was also observed with another, less potent, PBD dimer SG2000 and with a C2-linked PBD-ADC (mAb-SG3560) rather than N10-linked ADCs. Interestingly, in the latter case, the level of resistance for mAB-SG3560 was much greater than for the N10-linked ADCs. This may reflect differences in the biophysical properties of the released warheads [33]. The PBD dimer released by mAb-SG3560 is much more hydrophobic and may therefore be a better substrate for the ABC transporters. No cross-resistance was observed in the Karpas-299 resistant cell lines and with conventional DNA-cross-linking chemotherapeutic drugs cisplatin and melphalan. This is consistent with the fact that these agents are not considered to be substrates for ABCG2. In contrast, the DNA intercalating drug doxorubicin is a known substrate for MDR1, but again no cross-resistance was observed in the resistant lines, consistent with the lack of upregulation of ABCB1. Some cross-resistance was, however, observed with these agents in the NCI-N87 resistant lines, which is consistent with the fact that platinum agents can be substrates for ABCC1/2 as well as MDR1 [34].

Taken together, the data presented in this paper suggest that the ABC drug transporters ABCG2 and ABCC2 play an important role in determining sensitivity to PBD dimers and PBD-containing ADCs. It remains to be determined to what extent these findings in vitro translate into clinical relevance and whether these transporters become upregulated in patients that relapse on PBD based ADC therapy. Screening of tumors for expression may also be used as a biomarker for response to treatment. Development of clinically acquired drug resistance by this mechanism would also guide future patient management with non-PBD based therapy, including the use of ADCs delivering warheads of differing mechanism of action. These could involve the same targeting antibody since significant changes in antigen expression level have not been observed in the current study. An alternative strategy could involve combination therapy with specific ABC transporter inhibitors, as a clinical trial in R/R HL patients who were also previously refractory to BV, the mechanism for which is MDR1 related, has shown that combination with the wide-ranging ABC transporter inhibitor cyclosporine can re-sensitise patients to BV [35].

Several PBD dimer-based ADCs are currently undergoing clinical development in both solid and hematological tumors. The current study has shown that specific ABC transporters may be key in both selecting patients and as a marker of acquired resistance following repeated therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SC acknowledges ADC Therapeutics for funding a PhD studentship. J.A. Hartley acknowledges Programme Grant support from Cancer Research UK (C2559A/A16569).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: P.W. Howard is an employee of AstraZeneca/Spirogen. P.H van Berkel, F. Zammarchi, are employees of ADC Therapeutics and P.H. van Berkel, J.A. Hartley and P.W. Howard are also shareholders.

References

- 1.Yu B, Liu D. Antibody-drug conjugates in clinical trials for lymphoid malignancies and multiple myeloma. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0786-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zammarchi F, et al. ADCT-402, a PBD dimer-containing antibody drug conjugate targeting CD19-expressing malignancies. Blood. 2018;131(10):1094–1105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-813493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flynn MJ, et al. ADCT-301, a Pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) Dimer-Containing Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) Targeting CD25-Expressing Hematological Malignancies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15(11):2709–2721. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins DM, et al. Acquired Resistance to Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(3):394. doi: 10.3390/cancers11030394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barok M, Joensuu H, Isola J. Trastuzumab emtansine: mechanisms of action and drug resistance. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(2):209. doi: 10.1186/bcr3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nahta R, Esteva FJ. Herceptin: mechanisms of action and resistance. Cancer Lett. 2006;232(2):123–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loganzo F, et al. Tumor cells chronically treated with a trastuzumab-maytansinoid antibody-drug conjugate develop varied resistance mechanisms but respond to alternate treatments. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(4):952–63. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sung M, et al. Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis as a Novel Mechanism of Resistance to Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(1):243–253. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen R, et al. CD30 Downregulation, MMAE Resistance, and MDR1 Upregulation Are All Associated with Resistance to Brentuximab Vedotin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(6):1376–84. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter RB, et al. CD33 expression and P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux inversely correlate and predict clinical outcome in patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with gemtuzumab ozogamicin monotherapy. Blood. 2007;109(10):4168–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillet J-P, Gottesman MM. Multi-Drug Resistance in Cancer. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2009;596:47–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-416-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathawala RJ, et al. The modulation of ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer: a review of the past decade. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;18:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katayama K, Noguchi K, Sugimoto Y. Regulations of P-Glycoprotein/ABCB1/MDR1in Human Cancer Cells. New Journal of Science. 2014;2014:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beretta GL, et al. Overcoming ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance: The dual role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors as multitargeting agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2017;142:271–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limtrakul P, et al. Modulation of function of three ABC drug transporters, P-glycoprotein (ABCB1), mitoxantrone resistance protein (ABCG2) and multidrug resistance protein 1 (ABCC1) by tetrahydrocurcumin, a major metabolite of curcumin. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;296(1-2):85–95. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeshita A, et al. CMC-544 (inotuzumab ozogamicin) shows less effect on multidrug resistant cells: analyses in cell lines and cells from patients with B -cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lymphoma. British Journal of Haematology. 2009;146(1):34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guichard SM, et al. Influence of P-glycoprotein expression on in vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo antitumour activity of the novel pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer SJG-136. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(12):1811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartley JA. The development of pyrrolobenzodiazepines as antitumour agents. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20(6):733–44. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.573477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Silva IU, et al. Defining the roles of nucleotide excision repair and recombination in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(21):7980–90. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7980-7990.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spanswick VJ, et al. Repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks as a mechanism of clinical resistance to melphalan in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;100(1):224–229. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wynne P, et al. Enhanced repair of DNA interstrand crosslinking in ovarian cancer cells from patients following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(7):927–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHugh PJ, Spanswick VJ, Hartley JA. Repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks: molecular mechanisms and clinical relevance. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(8):483–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartley JA, et al. Pre-clinical pharmacology and mechanism of action of SG3199, the pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimer warhead component of antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) payload tesirine. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10479. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28533-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zammarchi F, et al. ADCT-502, a novel pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD)-based antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) targeting low HER2-expressing solid cancers. European Journal of Cancer. 2016;69:S28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spanswick VJ, Hartley JM, Hartley JA. Humana Press; 2009. Measurement of DNA Interstrand Crosslinking in Individual Cells Using the Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis (Comet) Assay; pp. 267–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spanswick VJ, et al. Evidence for different mechanisms of ‘unhooking’ for melphalan and cisplatin-induced DNA interstrand cross-links in vitro and in clinical acquired resistant tumour samples. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:436. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Britten RA, et al. ERCC1 expression as a molecular marker of cisplatin resistance in human cervical tumor cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2000;89(5):453–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferry KV, Hamilton TC, Johnson SW. Increased nucleotide excision repair in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells: role of ERCC1-XPF. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60(9):1305–13. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clingen PH, et al. The XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease and homologous recombination contribute to the repair of minor groove DNA interstrand crosslinks in mammalian cells produced by the pyrrolo[2,1-c][1,4]benzodiazepine dimer SJG-136. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(10):3283–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyle L, Ross DD. Multidrug resistance mediated by the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2) Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7340–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joyce H, et al. Influence of multidrug resistance and drug transport proteins on chemotherapy drug metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11(5):795–809. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2015.1028356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li F, et al. Intracellular Released Payload Influences Potency and Bystander-Killing Effects of Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Preclinical Models. Cancer Res. 2016;76(9):2710–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cailleau T, et al. Potentiation of PBD Dimers by Lipophilicity Manipulation. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19(9):741–752. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190401112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guminski AD, et al. MRP2 (ABCC2) and cisplatin sensitivity in hepatocytes and human ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100(2):239–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen R, et al. Inhibition of MDR1 Overcomes Resistance to Brentuximab Vedotin in Hodgkin Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1768. clincanres.1768.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.