Abstract

It is widely hypothesized that removing cellular transfer RNAs (tRNAs) – making their cognate codons unreadable – might create a genetic firewall to viral infection and enable sense codon reassignment. However, it has been impossible to test these hypotheses. In this work, following synonymous codon compression and laboratory evolution in Escherichia coli, we deleted the tRNAs and release factor-1, which normally decode two sense codons and a stop codon; the resulting cells could not read the canonical genetic code and were completely resistant to a cocktail of viruses. We reassigned these codons to enable the efficient synthesis of proteins containing three distinct noncanonical amino acids. Notably, we demonstrate the facile reprogramming of our cells for the encoded translation of diverse noncanonical heteropolymers and macrocycles.

Nature uses 64 triplet codons to encode the synthesis of proteins composed of the 20 canonical amino acids, and most amino acids are encoded by more than one synonymous codon (1). It is widely hypothesized that removing sense codons and the tRNAs that read them from the genome may enable the creation of cells with several properties not found in natural biology – including new modes of viral resistance (2) and the ability to encode the biosynthesis of noncanonical heteropolymers (3–6). However, these hypotheses have not been experimentally tested. Removing release factor-1 (RF1) (and therefore the ability to efficiently terminate translation on the TAG stop codon) from Escherichia coli, provides some resistance to a limited subset of phage (7, 8). However, this resistance is not general and phage are often propagated in the absence of RF1 (8) because the TAG stop codon is rarely used for the termination of translation (9), and – even when viral genes do terminate in an amber codon – the inability to read a stop codon does not limit the synthesis of full-length viral proteins. In contrast, sense codons are commonly at least 10 times more abundant than amber codons in viral genomes, and occur over the length of viral genes; thus we predicted that a cell that does not read sense codons would not make full-length viral proteins and would therefore be completely resistant to viruses.

Current strategies for encoding new monomers in cells are limited to encoding a single type of monomer (commonly in response to the amber stop codon) (3, 10, 11), directing the inefficient incorporation of monomers or potentially incompatible with encoding sequential monomers (12–17); these limitations preclude the synthesis of noncanonical heteropolymer sequences composed entirely of noncanonical monomers. We hypothesized that reassigning sense codons to noncanonical monomers may enable the efficient and sequential polymerization of distinct noncanonical monomers to produce noncanonical heteropolymers.

Recently, a strain of E. coli, Syn61, was created with a synthetic recoded genome in which all annotated occurrences of two sense codons (serine codons TCG and TCA) and a stop codon (TAG) were replaced with synonymous codons (18). In this study, we evolved Syn61 and deleted the tRNAs and release factor that decode TCG, TCA and TAG codons. We show that the resulting strain provides complete resistance to a cocktail of viruses. Moreover, we demonstrate the encoded incorporation of noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs) in response to all three codons and the encoded, programmable cellular synthesis of entirely noncanonical heteropolymers and macrocycles.

Creating Syn61Δ3

We predicted that replacing the annotated TCA, TCG and TAG codons in the genome would enable deletion of serT and serU (encoding tRNASer UGA and tRNASer CGA, respectively) and prfA (encoding RF1), which decode these codons, in a single strain (Fig. 1A). We previously showed that serT, serU, and prfA could be deleted in separate strains derived from Syn61 (18); however, this does not capture the potential epistasis between these genes. We sought to determine whether serT, serU, and prfA could be deleted in a single strain derived from Syn61.

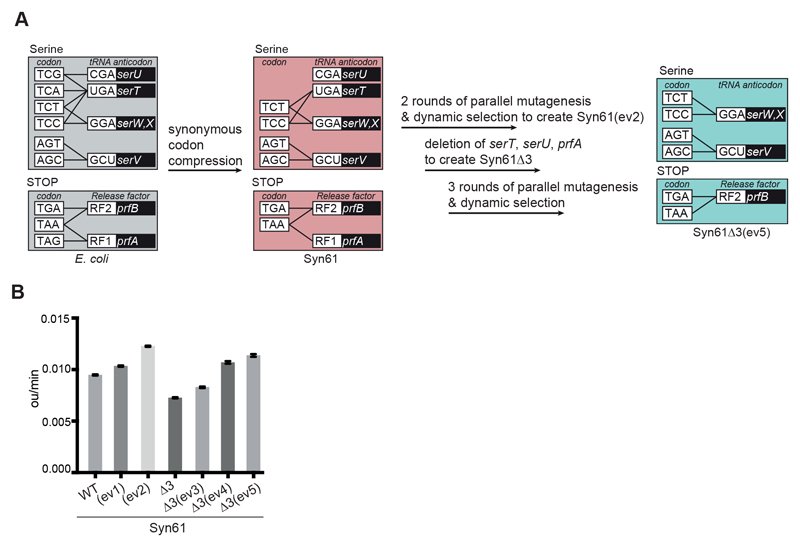

Fig. 1. Strain evolution and creation of Syn61Δ3.

(A) Schematic of strain evolution. Black lines connect the codons that encode serine and protein termination to the anticodons of the tRNAs or release factors predicted to decode them. The genes encoding the corresponding tRNAs and release factors are indicated in the black boxes. Cells with the decoding rules of Syn61 are denoted with a pink box throughout. Two rounds of parallel mutagenesis and dynamic selection created Syn61(ev2). serT, serU, and prfA were then deleted to create Syn61Δ3. Finally, three rounds of parallel mutagenesis and dynamic selection were applied to create Syn61Δ3(ev5); Syn61Δ3 and Syn61Δ3(ev5) are represented by the light-teal box throughout.

(B) Growth rates of Syn61 and all intermediate strains in the development of Syn61Δ3(ev5). Growth rates were calculated on the basis of growth curves measured for n = 8 replicate cultures for each strain. For statistics see methods in the supplementary materials.

Syn61 grows 1.6 fold slower than the strain from which it was derived (18). To increase the growth rate of the strain prior to serT, serU and prfA deletion, we applied a previously described random parallel mutagenesis and automated dynamic parallel selection strategy (19); this approach uses feedback control to dynamically dilute mutated cultures on the basis of growth rate, and thereby selects fast growing strains from within mutated populations (fig. S1A). Through two consecutive rounds of mutagenesis and selection we created a strain, Syn61(ev2), which grew 1.3-fold faster (Fig. 1B, fig. S1B to E, and data S1 and S2).

Next, we removed serU, serT and prfA from Syn61(ev2) to create Syn61Δ3 (Fig. 1A, fig. S1C, and data S1 and S2). This demonstrated that removing the target codons in Syn61 was sufficient to enable the deletion of all decoders of the target codons in the same strain. However, Syn61Δ3 grew 1.7- fold slower than Syn61(ev2) (Fig. 1B). This growth decrease may result from the presence of target codons in the genome of Syn61 that were not annotated and targeted (20, 21), and it may also result from the other noncanonical roles that tRNAs may play (22, 23).

We performed three sequential rounds of random parallel mutagenesis and automated dynamic parallel selection to evolve Syn61Δ3 to Syn61Δ3(ev5), which grew 1.6-fold faster than Syn61Δ3 (Fig. 1A and B, fig. S1, B, C, and F to H, and data S1). When grown in lysogeny broth (LB) media in shake flasks the doubling time of Syn61Δ3(ev5) was 38.72 +/- 1.02 min (fig. S1I). Syn61Δ3(ev5) contains 482 additional mutations with respect to Syn61 – 420 substitutions and 62 indels – of which 72 are in intergenic regions (data S1 and S3, and fig. S2). No target codons were reverted, further demonstrating the stability of our recoding scheme. Sixteen sense codons in non-essential genes were converted to target codons (5xTCG, 3xTCA, 8xTAG); these frequencies are comparable to those observed for other codons (data S1). Subsequent experiments used Syn61Δ3 or (once available) its evolved derivatives to investigate the new properties of these strains.

tRNA deletion ablates virus production in Syn61Δ3

We investigated the effects of deleting the genes encoding tRNASer CGA, tRNASer UGA, and RF1 on phage propagation by Syn61Δ3 (Fig. 2A), in a modified one-step growth experiment (24).

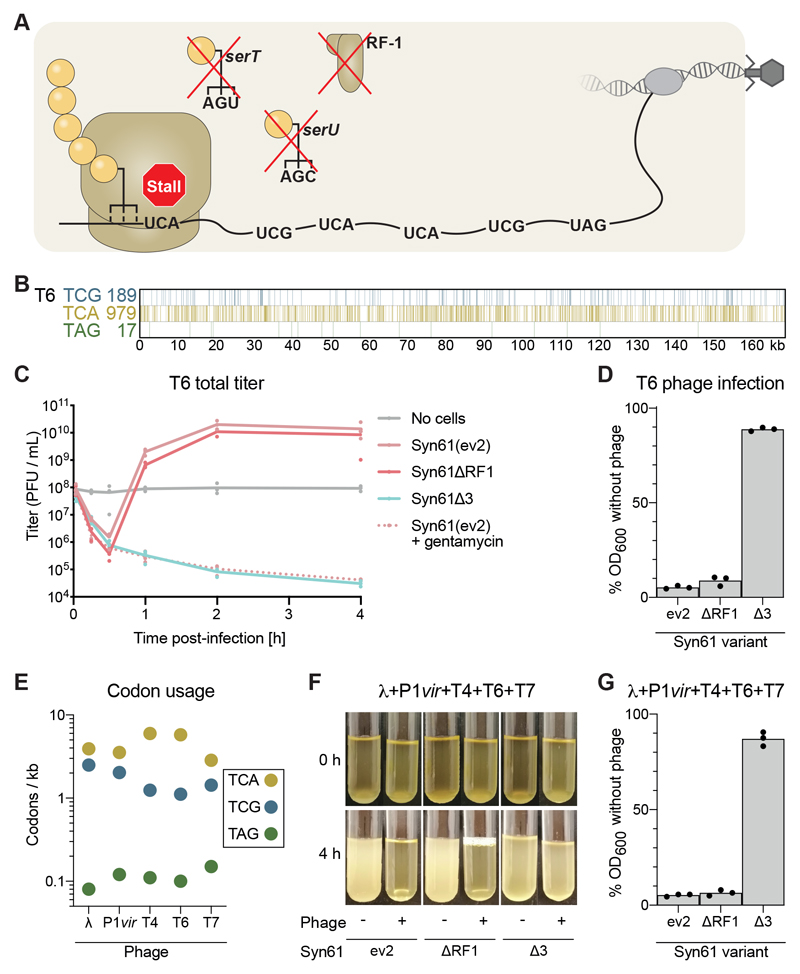

Fig. 2. Lytic phage propagation and cell lysis is obstructed in Syn61Δ3.

(A) Schematic of viral infection of Syn61Δ3. Deletion of serU (encoding tRNASer CGA), serT (encoding tRNASer UGA), and prfA (encoding RF1) makes the UCG, UCA, and UAG codons unreadable and the ribosome will stall at these codons within an mRNA that contains them, as shown here for a viral mRNA.

(B) Schematic of the number of TCG, TCA, and TAG codons and their positions in the genome of T6 phage.

(C) Cultures were infected with T6 phage at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 x 10-2, and the total titer (intracellular phage plus free phage) was monitored over 4 hours. PFU, plaque-forming units. Treatment with gentamicin was used to ablate protein synthesis, providing a control for cells that cannot synthesize viral proteins or produce new viral particles.

(D) T6 efficiently lyses Syn61 variants but not Syn61Δ3. Cultures were infected as in panel (C) and OD600 was measured after 4 hours.

(E) Number of the indicated codons per kilobase in each indicated phage.

(F and G) Syn61Δ3 survives simultaneous infection of multiple phage: (F) photos of the culture at the indicated time points after infection (+) or in the absence of infection (-). Cultures were infected with phage λ, P1, T4, T6, and T7, each with an MOI = 1 x 10-2. (G) OD600 of the cultures was measured after 4 hours. All experiments were performed in three independent replicates, the dots represent the independent replicates and the line (panel (C)) or bar [panels (D) and (G)] represents the mean. The photo (F) is a representative of data from three independent replicates.

For Syn61(ev2) the total titer of phage T6 [a representative of the lytic, T-even family (Fig. 2B)] briefly dropped (as phage infected cells) before rising to 2-logs10 above the input titer, as infected cells produced new phage particles (Fig. 2C, and fig. S3A). As expected, the optical density at 600-nm wavelength (OD600) of Syn61(ev2) was decreased by infection with T6 phage, which is lytic (Fig. 2D). Syn61ΔRF1 (data S1) and Syn61(ev2) produced a comparable level of phage on a comparable time scale and showed similar changes in OD600 upon infection. We conclude that deletion of RF1 alone has little, if any, effect on T6 phage production or cell lysis.

Infection of Syn61Δ3 with T6 phage led to a steady decrease in total phage titer. Notably, this decrease was comparable to that observed when protein synthesis – and therefore phage production in cells – was completely inhibited by addition of gentamicin (Fig. 2C, and fig. S3B). Moreover, T6 infection had a minimal effect on the growth of Syn61Δ3 (Fig. 2D). We conclude that Syn61Δ3 does not produce new phage particles upon infection with T6 phage and that T6 phage does not lyse these cells. Similar results were obtained with T7 phage, which has 57 TCG codons, 114 TCA codons and 6 TAG codons in its 40 kb genome (fig. S3, A, C and D). We treated cells with a cocktail of phage containing lambda, P1vir, T4, T6 and T7, which have TCA or TCG sense codons that are 10– to 58–times more abundant than the amber stop codon in their genomes (Fig. 2E and fig. S3E), and found that the treatment with this phage cocktail led to lysis of Syn61(ev2) and Syn61ΔRF1, but had little effect on the growth of Syn61Δ3 (Fig. 2, F and G), suggesting that the deletion of tRNAs in Syn61Δ3 provides resistance to a broad range of phage.

Reassigning target codons for ncAA incorporation

We expressed Ub11XXX genes (ubiquitin-His6 bearing TCG, TCA or TAG at position 11), and genes encoding the cognate orthogonal MmPylRS/MmtRNAPyl YYY pair (25) (in which the anticodon is complementary to the codon at position 11 in the Ub gene) in Syn61Δ3(ev5) (Fig. 3A and data S2).

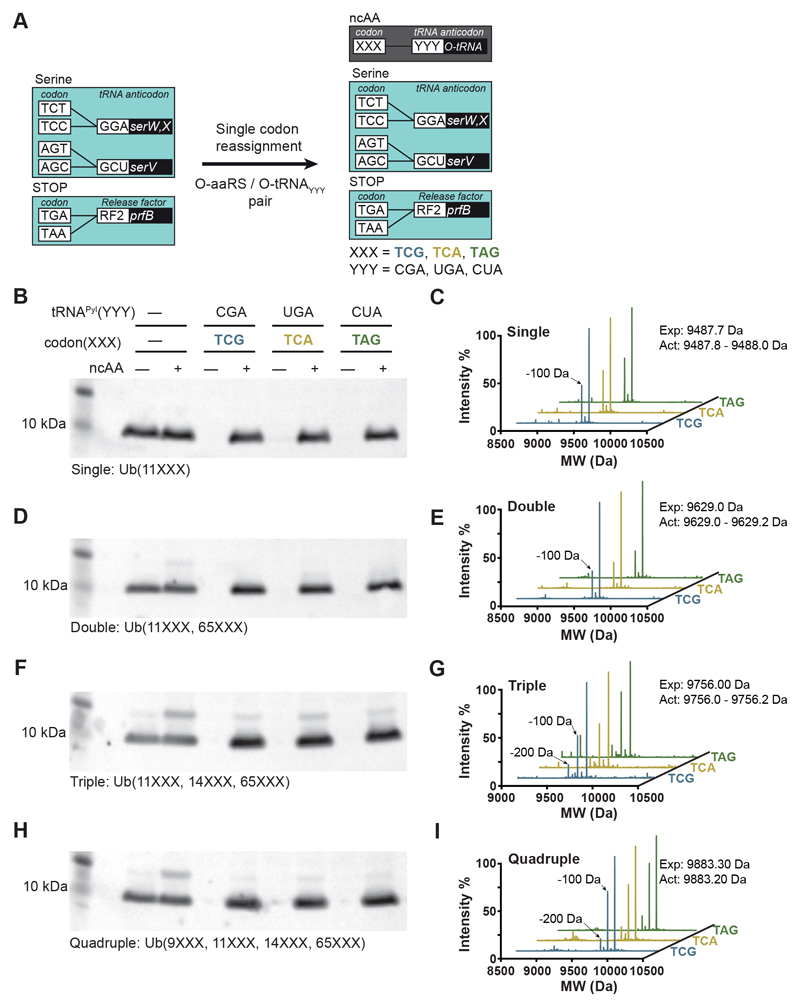

Fig. 3. Reassigning two sense codons and a stop codon to noncanonical amino acid in Syn61Δ3.

(A) Schematic of each codon reassignment. Introduction of an orthogonal aaRS/tRNAYYY pair – where YYY is the sequence of the anticodon of the orthogonal tRNA (encoded by O-tRNA) – to Syn61Δ3 (light teal box, as described in Fig. 1A) enables decoding of the cognate codon (XXX) introduced into a gene of interest. The orthogonal pair directs the incorporation of a noncanonical amino acid (ncAA) in response to the XXX codon. These codon reassignments are indicated in the dark gray box.

(B) TCG, TCA and TAG codons are not read by the translational machinery in Syn61Δ3, and codon reassignment enables ncAA incorporation into Ub11XXX. Plasmids encoding the orthogonal MmPylRS/MmtRNAPyl YYY pair and a C-terminally His6-tagged ubiquitin, with a single TCG, TCA, or TAG codon at position 11 (Ub11XXX), or no target codons (wild type, wt) were introduced into Syn61Δ3. “XXX” denotes a target codon and “YYY” denotes a cognate anticodon. Expression of ubiquitin-His6 was performed in the absence (-) or presence (+) of a ncAA substrate for MmPylRS, BocK. Full-length ubiquitin-His6 was detected in cell lysate from an equal number of cells with an anti-His6 antibody.

(C) Production of ubiquitin-His6 incorporating BocK, Ub-(11BocK)-His6, from a Ub11XXX gene bearing the indicated target codon was confirmed by ESI-MS. MW, molecular weight. Theoretical mass: 9487.7 Da; measured mass: 9487.8 Da (TCG), 9487.8 Da (TCA), and 9488.0 Da (TAG). The smaller peak of -100 Da results from the loss of tert-butoxycarbonyl from BocK.

(D) As in (B), but using Ub11XXX,65XXX, which contains target codons at positions 11 and 65 of the Ub gene.

(E) Production of ubiquitin-His6 incorporating BocK at positions 11 and 65, from a Ub11XXX65XXX gene bearing the indicated target codons was confirmed by ESI-MS. Theoretical mass: 9629.0 Da; measured mass: 9629.2 Da (TCG), 9629.0 Da (TCA), and 9629.0 Da (TAG). The smaller peak of -100 Da corresponds to loss of tert-butoxycarbonyl from BocK.

(F) As in (B), but using Ub11XXX,14XXX,65XXX, which contains target codons at positions 11, 14, and 65 of the Ub gene.

(G) Production of ubiquitin-His6 incorporating BocK at positions 11, 14 and 65, from Ub11XXX,14XXX,65XXX bearing the indicated target codons was confirmed by ESI-MS. Theoretical mass: 9756.1 Da; measured mass: 9756.2 Da (TCG), 9756.0 Da (TCA), and 9756.0 Da (TAG). The smaller peaks of -100 or -200 Da correspond to loss of tert-butoxycarbonyl from one or two BocK residues, respectively.

(H) As in (B), but using Ub9XXX,11XXX,14XXX,65XXX, which contains target codons at positions 9, 11, 14 and 65 of the Ub gene.

(I) Production of ubiquitin-His6 incorporating BocK at positions 9, 11, 14 and 65, from Ub9XXX,11XXX,14XXX,65XXX bearing the indicated target codons was confirmed by ESI-MS. Theoretical mass: 9883.3 Da; measured mass: 9883.2 Da (TCG), 9883.2 Da (TCA), and 9883.2 Da (TAG). The smaller peaks of -100 or -200 Da correspond to loss of tert-butoxycarbonyl from one or two BocK residues, respectively. All experiments were performed in biological replicates three times with similar results.

In the absence of added ncAA, little to no ubiquitin was detected from Ub genes bearing a target codon at position 11, while control experiments demonstrated that ubiquitin is produced from a ‘wildtype’ gene that does not contain any target codons (Fig. 3B). Thus, none of the target codons are read by the endogenous translational machinery in Syn61Δ3. This further demonstrates that all of the target codons are orthogonal in this strain.

Upon addition of a ncAA substrate for the MmPylRS / MmtRNAPyl pair (Nε-((tert-butoxy)carbonyl)-L-lysine (BocK)) (25), ubiquitin was produced at levels comparable to wildtype controls (Fig. 3B and data S4). ESI-MS and MS/MS demonstrated the genetically directed incorporation of BocK at position 11 of Ub in response to each target codon using the complementary MmPylRS / MmtRNAPyl YYY pair (Fig. 3C and fig. S4A). Additional experiments demonstrated efficient incorporation of ncAAs in response to sense and stop codons in GST-MBP (fig. S5 and data S4). We demonstrated good yields of Ub-His6 incorporating 2, 3, or 4 ncAAs into a single polypeptide in response to each of the target codons (data S4; Fig. 3, D to I; and fig. S4, B to G), and we further demonstrated the incorporation of 9 ncAAs in response to 9 TCG codons in a single repeat protein (fig. S6). Together, these results demonstrated that the sense codons TCG and TCA, and the stop codon TAG, can be efficiently reassigned to ncAAs in Syn61Δ3 derivatives.

Encoding distinct ncAAs in response to distinct target codons

Next, we assigned TCG, TCA and TAG codons to distinct ncAAs in Syn61Δ3(ev4) using engineered mutually orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS)/tRNA pairs that recognize distinct ncAAs and decode distinct codons (Fig. 4A and fig. S7). We incorporated two distinct ncAAs into ubiquitin in response to TCG and TAG codons (Fig. 4B and fig. S8, A and B), and demonstrated the incorporation of two distinct ncAAs at four sites in ubiquitin, with each ncAA incorporated at two different sites in the protein (Fig. 4, B and C; and fig. S8, C to E; and data S4). We incorporated three distinct ncAAs into ubiquitin, in response to TCG, TCA and TAG codons (Fig. 4, D and E, and fig. S8F). We demonstrated the generality of our approach by synthesizing seven distinct versions of ubiquitin, each of which incorporated three distinct ncAAs (fig. S9, fig. S10, and data S4).

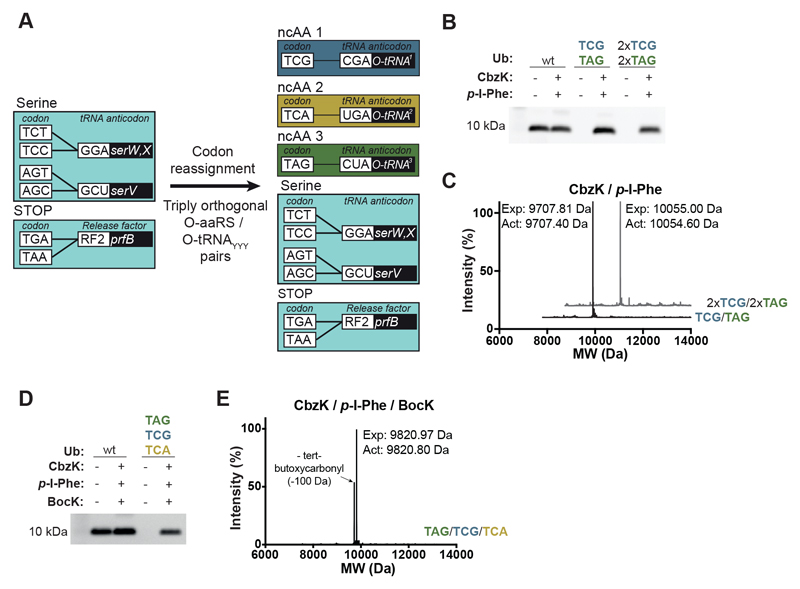

Fig. 4. Double and triple incorporation of distinct noncanonical amino acids into TCG, TCA, and TAG codons in Syn61Δ3 cells.

(A) Reassignment of TCG (blue box), TCA (gold box) and TAG (green box) codons to distinct ncAAs in Syn61Δ3. Reassigning all three codons to distinct ncAAs in a single cell requires three engineered triply orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs. Each pair must recognize a distinct ncAA and decode a distinct codon. The tRNAs from these triply orthogonal pairs are labelled O-tRNA1-3.

(C) ESI-MS analyses of purified Ub-(11CbzK, 65p-I-Phe) (black trace) and Ub-(11CbzK, 14CbzK, 57p-I-Phe, 65p-I-Phe) (gray trace), expressed in the presence of CbzK and p-I-Phe, as described in (E) and purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography. These data confirm the quantitative incorporation of CbzK and p-I-Phe in response to TCG and TAG codons, respectively. Ub-(11CbzK, 65p-I-Phe), theoretical mass: 9707.81 Da; measured mass: 9707.40 Da. Ub-(11CbzK, 14CbzK, 57p-I-Phe, 65p-I-Phe), theoretical mass: 10,055.00 Da; measured mass: 10,054.60 Da.

(D) The incorporation of three distinct noncanonical amino acids into TCG, TCA, and TAG codons in a single gene. Syn61Δ3(ev4) – containing the 1R26PylRS(CbzK)/AlvtRNAΔNPyl(8) CGA pair, the MmPylRS/MmtRNAPyl UGA pair and the AfTyrRS(p-I-Phe)/AftRNATyr(A01) CUA pair – were provided with CbzK, BocK and p-I-Phe. Cells also contained Ub9TAG,11TCG,14TCA (TCG/TCA/TAG). Expression of this gene was performed in the absence (-) or presence (+) of the ncAAs. Full-length Ub-(9p-I-Phe, 11CbzK, 14BocK)-His6 was detected in cell lysate from an equal number of cells with an anti-His6 antibody.

(E) ESI-MS of purified Ub-(9p-I-Phe, 11CbzK, 14BocK), theoretical mass: 9820.97 Da; measured mass: 9820.80 Da. Western blot experiments [(B) and (D)] were performed in five biological replicates with similar results. The ESI-MS data [(C) and (E)] were collected once.

Encoded noncanonical polymers and macrocycles

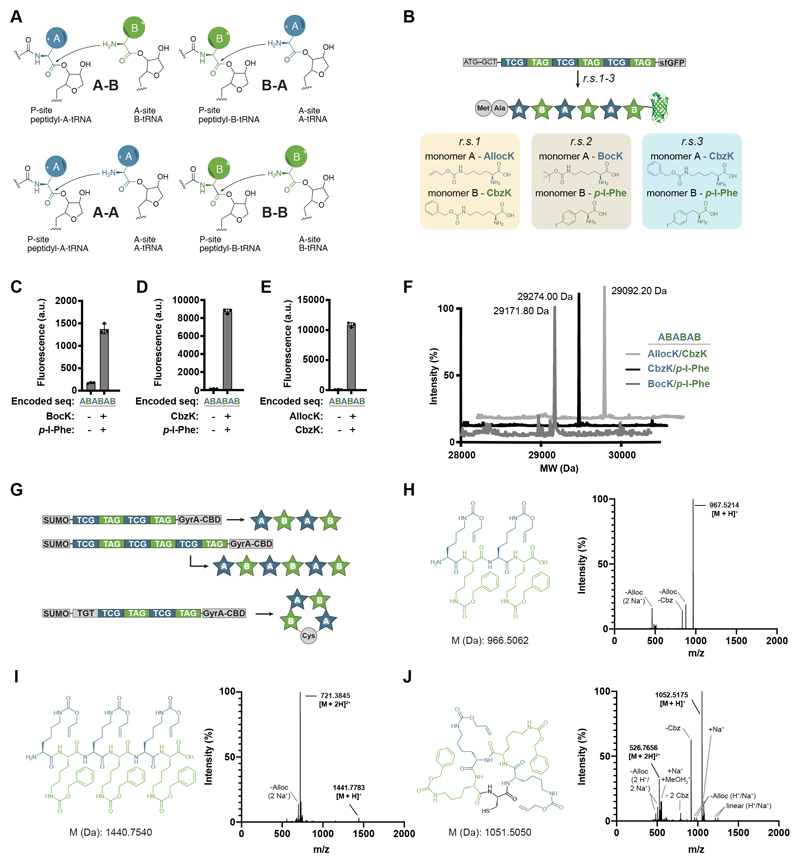

For a linear polymer composed of two distinct monomers (A and B) there are four elementary polymerization steps (A+B -> AB, B+A -> BA, A+A -> AA, B+B -> BB) from which any sequence can be composed (Fig. 5A). For ribosome-mediated polymerization these four elementary steps correspond to each monomer acting as an aminoacyl-site (A-site) or peptidyl-site (P-site) substrate to form a bond with another copy of the same monomer or with a distinct monomer (Fig. 5A). We encoded each elementary step by inserting TCG-TCG (encoding AA; we arbitrarily assign monomer A to the TCG codon in this nomenclature), TAG-TAG (encoding BB; we assign monomer B to the TAG codon), TCG-TAG (encoding AB) and TAG-TCG (encoding BA) at codon 3 of a superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) gene. We demonstrated the elementary steps for three pairs of monomers: A = BocK, B = (S)-2-Amino-3-(4-iodophenyl)propanoic acid (p-I-Phe); A = Nε-(carbobenzyloxy)-L-lysine (CbzK), B = p-I-Phe; A = Nε-allyloxycarbonyl-L-lysine (AllocK), B = CbzK (Fig. 5B and fig. S11). We genetically encoded six entirely non-natural tetrameric sequences and a hexameric sequence for each pair of monomers, as well as an octameric sequence for the AllocK, CbzK pair (22 synthetic polymer sequences in total) (figs. S11 and S13 and Fig. 5, C to E). All encoded polymerizations were ncAA dependent (figs. S11 and S12B and Fig. 5, C to E) and ESI-MS confirmed that we had synthesized the noncanonical hexamers and octamers as sfGFP fusions (Fig. 5F and fig. S12C). We encoded tetramer and hexamer sequences composed of AllocK and CbzK between SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) and GyrA-CBD (DNA gyrase subunit A-chitin-binding domain) and purified the free polymers (Fig. 5, G to I, and fig. S13). Finally, we encoded the synthesis of a non-natural macrocycle reminiscent of the products of non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (Fig. 5, G and J).

Fig. 5. Programmable, encoded synthesis of noncanonical heteropolymers and macrocycles.

(A) Elementary steps in the ribosomal polymerization of two distinct ncAA monomers [labelled A (dark blue) and B (green)]. All linear heteropolymer sequences composed of A and B can be encoded from these four elementary steps.

(B) Encoding heteropolymer sequences (noncanonical monomers are shown as stars). The sequence of monomers in the heteropolymer is programmed by the sequence of codons written by the user. The identity of monomers (A and B) is defined by the aaRS/tRNA pairs added to the cell. Cells can be reprogrammed to encode different heteropolymer sequences from a single DNA sequence. Sequences were encoded as insertions at position 3 of sfGFP-His6. Reassignment scheme 1 (r.s.1) uses the MmPylRS/MmtRNAPyl CGA pair to assign AllocK as monomer A and the 1R26PylRS(CbzK)/AlvtRNAΔNPyl(8) cua pair to assign CbzK as monomer B (Fig. S7, D to E). r.s.2 uses the MmPylRS/MmtRNAPyl CGA pair to assign BocK as monomer A and an AfTyrRS(p-I-Phe)/AftRNATyr(A01) CUA pair to assign p-I-Phe as monomer B. r.s.3 uses the 1R26PylRS(CbzK)/AlvtRNAΔNPyl(8) CGA pair to assign CbzK as monomer A and the AfTyrRS(p-I-Phe)/AftRNATyr(A01) CUA pair to assign p-I-Phe as monomer B.

(C-E) Polymerization of the encoded sequence composed of the indicated ncAAs, and the resulting sfGFP-His6 expression in Syn61Δ3(ev5) were dependent on the addition of both ncAAs to the medium. a.u., arbitrary units.

(F) ESI-MS of purified sfGFP-His6 variants containing the indicated ncAA hexamers. BocK/p-I-Phe (expected mass after loss of N-terminal methionine: 29,172.07 Da; observed: 29,171.8 Da), CbzK/p-I-Phe (expected mass after loss of N-terminal methionine: 29,274.13 Da; observed: 29,274.0 Da) and AllocK/CbzK (expected mass after loss of N-terminal methionine: 29,091.64 Da; observed: 29,092.2 Da). The ESI-MS data was collected once.

(G) Encoded synthesis of free noncanonical polymers. DNA sequences encoding a tetramer and a hexamer were inserted between SUMO and a GyrA intein coupled to a CBD, in Syn61Δ3(ev5) cells containing the same pairs as in r.s.1 (B). Expression of the constructs, followed by ubiquitin-like-specific protease 1 (Ulp1) cleavage and GyrA trans-thioesterification cleavage, results in the isolation of free noncanonical tetramer and hexamer polymers. Adding an additional cysteine immediately upstream of the polymer sequence results in self-cleavage and release of a macrocyclic noncanonical polymer.

(H-J) Chemical structures and ESI-MS spectra of the purified linear and cyclic AllocK/CbzK heteropolymers. The raw ESI-MS spectra show the relative intensity and observed mass/charge ratios for the different noncanonical peptides. The observed masses corresponding to the expected [M + H]+ or [M + 2H]2+ ions are highlighted in bold. Other adducts and fragment ions are labeled relative to these.

Discussion

We have synthetically uncoupled our strain from the ability to read the canonical code, and this advance provides a potential basis for bioproduction without the catastrophic risks associated with viral contamination and lysis (26, 27). We note that the synthetic codon compression and codon reassignment strategy we have implemented is analogous to models proposed for codon capture in the course of natural evolution (28).

Future work will expand the principles we have exemplified herein to further compress and reassign the genetic code. We anticipate that, in combination with ongoing advances in engineering the translational machinery of cells (4), this work will enable the programmable and encoded cellular synthesis of an expanded set of noncanonical heteropolymers with emergent, and potentially useful, properties.

Supplementary Material

One Sentence Summary.

The genetic code of a synthetic E. coli strain is reprogrammed to confer viral resistance and enable the encoded, programmable synthesis of noncanonical polymers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Z. Zeng and R. Monson (Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge) for helping with phage assays. Funding: This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC), UK (MC_U105181009, MC_UP_A024_1008, and Development Gap Fund Award P2019-0003) and an ERC Advanced Grant SGCR, all to J.W.C.

Footnotes

Author contributions: L.F.H.F and K.C.L performed strain evolution experiments. L.F.H.F., W.E.R. and S.B. performed experiments to knockout serT, serU, and prfA. L.F.H.F analyzed genome sequences. J.F. performed phage experiments with advice and supervision from G.P.C.S. W.E.R., D.d.l.T., T.S.E., Y.C., D.C., F.L.B., M.S. and S.M. performed experiments and analysis to demonstrate codon reassignment and ncAA incorporation in response to target codons. D.C. wrote scripts to analyze codon usage in bacteriophage genomes. J.W.C supervised the project and wrote the manuscript together with the other authors.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability

The GenBank accession numbers for all the strains and plasmids described in the text are provided in data S1 and S2, and the authors agree to provide any data or materials and strains used in this study upon request. Scripts for analyzing codon usage, next-generation sequencing sample preparation, and automated strain evolution are available in Zenodo (30).

References and Notes

- 1.Crick FHC, Barnett L, Brenner S, Watts-Tobin RJ. General Nature of the Genetic Code for Proteins. Nature. 1961;192:1227–1232. doi: 10.1038/1921227a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marliere P. The farther, the safer: a manifesto for securely navigating synthetic species away from the old living world. Systems and Synthetic Biology. 2009;3:77. doi: 10.1007/s11693-009-9040-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin JW. Expanding and reprogramming the genetic code. Nature. 2017;550:53–60. doi: 10.1038/nature24031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de la Torre D, Chin JW. Reprogramming the genetic code. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2020;22:169–184. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Passioura T, Suga H. Reprogramming the genetic code in vitro. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster AC, et al. Programming peptidomimetic syntheses by translating genetic codes designed de novo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6353–6357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1132122100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lajoie MJ, et al. Genomically Recoded Organisms Expand Biological Functions. Science. 2013;342:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.1241459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma NJ, Isaacs FJ. Genomic Recoding Broadly Obstructs the Propagation of Horizontally Transferred Genetic Elements. Cell Systems. 2016;3:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korkmaz G, Holm M, Wiens T, Sanyal S. Comprehensive analysis of stop codon usage in bacteria and its correlation with release factor abundance. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:30334–30342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.606632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young DD, Schultz PG. Playing with the Molecules of Life. ACS Chemical Biology. 2018;13:854–870. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu CC, Schultz PG. Adding New Chemistries to the Genetic Code. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, et al. A semi-synthetic organism that stores and retrieves increased genetic information. Nature. 2017;551:644–647. doi: 10.1038/nature24659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer EC, et al. New codons for efficient production of unnatural proteins in a semisynthetic organism. Nature Chemical Biology. 2020;16:570–576. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0507-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann H, Wang K, Davis L, Garcia-Alai M, Chin JW. Encoding multiple unnatural amino acids via evolution of a quadruplet-decoding ribosome. Nature. 2010;464:441–444. doi: 10.1038/nature08817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K, et al. Optimized orthogonal translation of unnatural amino acids enables spontaneous protein double-labelling and FRET. Nature Chemistry. 2014;6:393–403. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunkelmann DL, Willis JCW, Beattie AT, Chin JW. Engineered triply orthogonal pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pairs enable the genetic encoding of three distinct non-canonical amino acids. Nature Chemistry. 2020;12:535–544. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0472-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Italia JS, et al. Mutually Orthogonal Nonsense-Suppression Systems and Conjugation Chemistries for Precise Protein Labeling at up to Three Distinct Sites. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2019;141:6204–6212. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b12954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredens J, et al. Total synthesis of Escherichia coli with a recoded genome. Nature. 2019;569:514–518. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmied WH, et al. Controlling orthogonal ribosome subunit interactions enables evolution of new function. Nature. 2018;564:444–448. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0773-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemm MR, et al. Small Stress Response Proteins in Escherichia coli: Proteins Missed by Classical Proteomic Studies. Journal of Bacteriology. 2010;192:46. doi: 10.1128/JB.00872-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meydan S, et al. Retapamulin-Assisted Ribosome Profiling Reveals the Alternative Bacterial Proteome. Mol Cell. 2019;74:481–493.:e486. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz A, Elgamal S, Rajkovic A, Ibba M. Non-canonical roles of tRNAs and tRNA mimics in bacterial cell biology. Mol Microbiol. 2016;101:545–558. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su Z, Wilson B, Kumar P, Dutta A. Noncanonical Roles of tRNAs: tRNA Fragments and Beyond. Annu Rev Genet. 2020;54:47–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-022620-101840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.You L, Suthers PF, Yin J. Effects of Escherichia coli Physiology on Growth of Phage T7 In Vivo and In Silico. Journal of Bacteriology. 2002;184:1888. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1888-1894.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanagisawa T, et al. Multistep Engineering of Pyrrolysyl-tRNA Synthetase to Genetically Encode Ne—(o-Azidobenzyloxycarbonyl) lysine for Site-Specific Protein Modification. Chemistry & Biology. 2008;15:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bethencourt V. Virus stalls Genzyme plant. Nature Biotechnology. 2009;27:681–681. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zahn J, Halter M. Surveillance and Elimination of Bacteriophage Contamination in an Industrial Fermentation Process. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osawa S, Jukes TH. Codon reassignment (codon capture) in evolution. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1989;28:271–278. doi: 10.1007/BF02103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cervettini D, et al. Rapid discovery and evolution of orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-tRNA pairs. Nature Biotechnology. 2020;38:989–999. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cervettini D, Liu KC, Chin JW. Scripts for Sense Codon Reassignment Enables Viral Resistance and Encoded Polymer Synthesis, Version 1.0, Zenodo. 2021 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4666529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badran AH, Liu DR. Development of potent in vivo mutagenesis plasmids with broad mutational spectra. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8425. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K, Fredens J, Brunner SF, Kim SH, Chia T, Chin JW. Defining synonymous codon compression schemes by genome recoding. Nature. 2016;539:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature20124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deatherage DE, Barrick JE. Identification of mutations in laboratory-evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1151:165–188. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0554-6_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorvaldsd Hóttir, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): High-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cock PJA, Antao T, Chang JT, Chapman BA, Cox CJ, Dalke A, Friedberg I, Hamelryck T, Kauff F, Wilczynski B, de Hoon MJL. Biopython: Freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1422–1423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunter JD. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput Sci Eng. 2007;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott TS, Townsley FM, Bianco A, Ernst RJ, Sachdeva A, Elsässer SJ, Davis L, Lang K, Pisa R, Greiss S, Lilley KS, et al. Proteome labeling and protein identification in specific tissues and at specific developmental stages in an animal. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:465–472. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan C, Xiong H, Reynolds NM, Söll D. Rationally evolving tRNAPyl for efficient incorporation of noncanonical amino acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beyer JN, Hosseinzadeh P, Gottfried-Lee I, Van Fossen EM, Zhu P, Bednar RM, Karplus PA, Mehl RA, Cooley RB. Overcoming near-cognate suppression in a release factor 1-deficient host with an improved nitro-tyrosine tRNA synthetase. J Mol Biol. 2020;432:4690–4704. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schultz KC, Supekova L, Ryu Y, Xie J, Perera R, Schultz PG. A genetically encoded infrared probe. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13984–13985. doi: 10.1021/ja0636690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Telenti A, Southworth M, Alcaide F, Daugelat S, Jacobs WR, Jr, Perler FB. The Mycobacterium xenopi GyrA protein splicing element: Characterization of a minimal intein. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6378–6382. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6378-6382.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The GenBank accession numbers for all the strains and plasmids described in the text are provided in data S1 and S2, and the authors agree to provide any data or materials and strains used in this study upon request. Scripts for analyzing codon usage, next-generation sequencing sample preparation, and automated strain evolution are available in Zenodo (30).