Structural biology has paved the way for a ground-up description of biological systems, contributing atomic structures of proteins amenable to crystallography, uncovering high-resolution maps of ‘difficult’ proteins with the cryo-electron microscopy revolution, and filling knowledge gaps regarding dynamic and disordered proteins using nuclear magnetic resonance. From the very beginning, the cellular context of a protein of interest was considered; John Kendrew chose sperm whale myoglobin for crystallization because of myoglobin’s importance and abundance within the dark red tissues of diving animals and thereby solved the first three-dimensional protein structure1. Together, cell and structural biology work synergistically towards a common goal: to build a mechanistic description of biological systems.

Although at first these two disciplines were seemingly separated by the scale at which they approached problems, technical advances are bringing them closer together. Structural biology techniques have progressively described protein assemblies of increasing size and complexity. At the same time, novel microscopy methods have steadily decreased the scale at which it is possible to view the operation of cell biological processes. These advances provide complementary viewpoints to address conceptually similar questions and thus blur previous boundaries between cell and structural biology. An emerging technology at this interface is electron cryo-tomography (cryo-ET) applied to cell and tissue samples. It directly allows structural information to be obtained within the cellular context (Fig. 1). Several recent studies provide a glimpse to what the future holds for a joint adventure of cell and structural biologists.

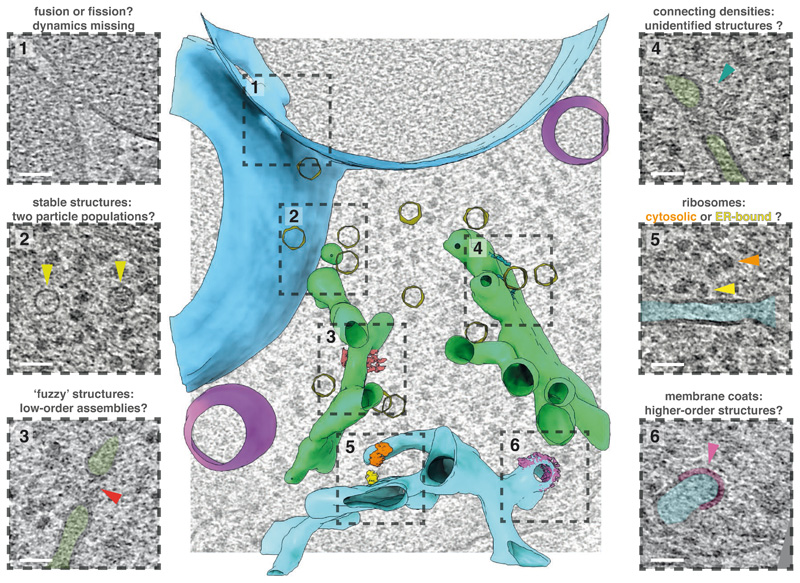

Fig. 1.

Cell architecture within a budding yeast cell, visualized by cryo-ET. The rich cellular context offers insights into how supramolecular organization relates to cellular functions. At the same time, conformationally heterogenous, transient, rare or even unidentified structures await structural investigation. Scale bars, 50 nm. Figure prepared using UCSF ChimeraX9 and IMOD10.

Analogously to protein structure, the molecular architecture of cells – the spatial and temporal arrangement of macromolecules – also provides a key to unlock mechanisms of biological processes. For instance, the positioning and distribution of individual proteins within the cellular landscape can reveal their functions2. Supramolecular assemblies can range from highly ordered, such as cytoskeleton filaments, to multivalent, possibly stochastic, interactions which are only revealed in the cellular context2. Cryo-ET’s ability to visualise individual proteins that adopt multiple conformations or oligomeric states can reveal correlations between subcellular location and structure without being strictly dependent on the individual structure’s resolution3. Optimistically, the cellular context could help to build a more complete understanding of intrinsically disordered proteins. For example, within the regular arrangement of nuclear pore rings are disordered Phe-Gly repeats. Although high-resolution information of these repeats remains elusive by cryo-ET, knowledge of their location within tomograms might be harnessed towards understanding the interplay between structured and unstructured cellular elements4. Another exciting prospect of cryo-ET is the description of hitherto unknown or elusive supercomplexes within the cell. A stirring recent example is the in-cell structure of the actively transcribing-translating expressome5.

Many outstanding questions regarding cellular structures will require integration of temporal and compositional information. Towards this goal, advances in correlative light and electron microscopy expand the range of questions addressable by cryo-ET3. Moreover, visually unresolvable, molecular-level information can be integrated using cross-linking mass spectrometry5,6. Finally, particular molecular architectures may be specific to organisms or tissues. It is thus inspiring that structural work within multicellular samples and visualization of molecular structures within clinical samples appear within reach7,8.

Collating all these emerging opportunities, we believe that the exploration of cell and tissue architecture represents an exciting future avenue for structural biology. This endeavour requires a blend of skills and seamless collaborations between cell and structural biologists, towards their common goal of a mechanistic understanding of biological complexity.

References

- 1.Kendrew JC, et al. A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis. Nature. 1958;181:662–6. doi: 10.1038/181662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo Q, et al. In Situ Structure of Neuronal C9orf72 Poly-GA Aggregates Reveals Proteasome Recruitment. Cell. 2018;172:696–705.:e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ader NR, et al. Molecular and topological reorganizations in mitochondrial architecture interplay during Bax-mediated steps of apoptosis. Elife. 2019;8:e40712. doi: 10.7554/eLife.40712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zila V, et al. Cone-shaped HIV-1 capsids are transported through intact nuclear pores. Cell. 2021;184:1032–1046.:e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Reilly FJ, et al. In-cell architecture of an actively transcribing-translating expressome. Science. 2020;369:554–557. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Kügelgen A, et al. In Situ Structure of an Intact Lipopolysaccharide-Bound Bacterial Surface Layer. Cell. 2020;180:348–358.:e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaffer M, et al. A cryo-FIB lift-out technique enables molecular-resolution cryo-ET within native Caenorhabditis elegans tissue. Nat Methods. 2019;16:757–762. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss GL, et al. Architecture and function of human uromodulin filaments in urinary tract infections. Science. 2020;369:1005–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz9866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettersen EF, et al. Protein Sci. 2021;30:70–82. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]