Abstract

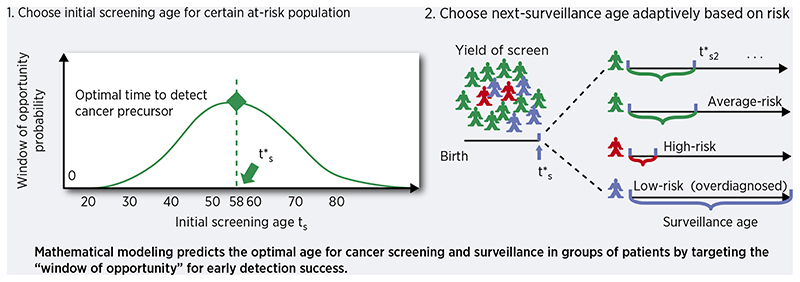

Cancer screening and early detection efforts have been partially successful in reducing incidence and mortality, but many improvements are needed. Although current medical practice is informed by epidemiological studies and experts, the decisions for guidelines are ultimately ad hoc. We propose here that quantitative optimization of protocols can potentially increase screening success and reduce overdiagnosis. Mathematical modeling of the stochastic process of cancer evolution can be used to derive and optimize the timing of clinical screens so that the probability is maximal that a patient is screened within a certain “window of opportunity” for intervention when early cancer development may be observable. Alternative to a strictly empirical approach or microsimulations of a multitude of possible scenarios, biologically-based mechanistic modeling can be used for predicting when best to screen and begin adaptive surveillance. We introduce a methodology for optimizing screening, assessing potential risks, and quantifying associated costs to healthcare using multiscale models. As a case study in Barrett’s esophagus (BE), these methods were applied for a model of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) that was previously calibrated to US cancer registry data. Optimal screening ages for patients with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease were older (58 for men, 64 for women) than what is currently recommended (age > 50 years). These ages are in a cost-effective range to start screening and were independently validated by data used in current guidelines. Collectively, our framework captures critical aspects of cancer evolution within BE patients for a more personalized screening design.

Keywords: Cancer screening, stochastic modeling, early detection

Introduction

The main rationale for cancer screening is that earlier detection of a disease during a patient’s lifetime offers the opportunity to change its prognosis. Compared with incidental cancers, screening can improve the prognosis for patients with early occult cancers detected before symptoms develop, and perhaps even more importantly through removal of pre-invasive lesions such as adenomas in the colon, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in the cervix, and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in the breast. In 2018, it was estimated that nearly half of all cancer incidence in the US was attributable to detection by screening [1] but it is difficult to assess how many of these patients were destined to die from other causes before these cancers would have led to a symptomatic diagnosis, thus proving their screens to be ineffective. Current programs suffer from the problem of overdiagnosis of benign lesions and yet, with often dismal and costly consequences, there is still under-diagnosis of dangerous lesions because they were either missed by the screen itself or there was a lack of screening uptake by high risk individuals at the appropriate age [2]. Consequently, improvement in screening success is an important health policy goal, and one primed for quantitative assessment. Simply put, there is a mathematical balancing act to solve from both public health and cost-effectiveness perspectives: the goal is to maximize successful prevention of future lethal cancers (often by removing their precursors detected on a screen) and minimize the likelihood of overdiagnosis.

From a biological perspective, malignant cells develop in the body originally from normal cells existing at birth through the evolutionary process of carcinogenesis [3]. This process of cancer evolution is stochastic, meaning that random mutations can occur in cells throughout life, which may eventually lead to a malignant phenotype selected in a tissue, but not necessarily so. Mathematical models of carcinogenesis, tumor progression, and metastasis are powerful tools to describe this process and, when calibrated to observed data, can infer important parameters for evolution such as time of metastatic seeding and selection strength of certain mutations that may confer resistance to treatment [4, 5]. Because such variables are not immediately measurable from data, mathematical models are now being explicitly incorporated into translational aims such as interval planning for adaptive therapy trials in cancer patients [6, 7]. We propose that these quantitative models can be further utilized at an earlier stage for cancer prevention and control - namely, to infer sojourn (waiting) times for specific stages of cancer evolution that we wish to target, and then to use these targets as objective functions to optimize the efficacy of cancer screening strategies and surveillance for early detection [8].

For example, in colorectal cancer (CRC) there are certain stages of carcinogenesis that are both common in type (APC gene inactivation for initiation of adenomas) and in timing (adenomas become detectable around age 45 in males and females) [9]. Thus, although no two paths of carcinogenesis are exactly the same in two patients, there are most probable timescales for this stochastic process to take place (as seen in age-specific incidence curves) while still allowing for less likely events to happen (e.g., very young CRC cases). These stochastic features were captured in the first mathematical descriptions of cancer, which have been studied and applied extensively in combination with biostatistical methods for over 60 years [10, 11]. By analyzing the structure of multistage models, we can also formulate these probability distributions as certain “windows of opportunity” that are crucial to capture in cancer screening planning. In this study, we derive conclusions from the theory of stochastic processes applied to carcinogenesis to formally optimize the timing of initial cancer screens in a population, and optimize subsequent surveillance adaptively, conditional on a previous exam result.

We present analytical results for a generalized framework and then apply it in a proof-of-concept study for screening of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), the metaplastic precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), a deadly cancer of unmet need clinically. Briefly, because BE itself is essentially asymptomatic, the majority of BE patients remain undiagnosed and thus most EAC cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. This is unfortunate because, (1) mortality associated with EAC is very high (a majority of patients die within a year), and (2) prior diagnosis of BE is positively associated with improved EAC survival in patients [12]. Therefore US and UK gastroenterologists have been focused on positively identifying BE patients on screening endoscopy, and then recommending that these patients undergo lifelong endoscopic surveillance in order to detect any dysplasia or early cancer that may be removed, thus preventing future lethal EAC. However the clinical reality is that only 0.2-0.5% of people with non-dysplastic BE develop EAC each year [13]. Thus, the majority of diagnosed BE patients will attain little benefit per follow-up exam and over-surveillance of BE patients with no evidence of premalignant high grade dysplasia (HGD) poses a costly problem due to lifelong surveillance recommendations (as frequently as every 3 years by current guidelines). Nonetheless, computational modeling of available population data suggests that, although the annual risk is low for BE to progress to EAC, the vast majority of incident EACs are expected to arise in BE patients so identifying these patients could save lives through early detection during surveillance [14].

To capture this population effectively, recommendations for screening high risk individuals and enrolling positive BE patients into surveillance regimens have been proposed to beneficially use healthcare resources. Overall, these tactics have been limited in strata choices, variable across organizations, and based on conclusions from observational data alone [15]. For example, one current US guideline from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) strongly recommends BE screening for men with chronic and/or frequent (more than weekly) gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms and two or more risk factors for BE or EAC. These risk factors include: age greater than 50 years, Caucasian race, presence of central obesity, current or past history of smoking, and a confirmed family history of BE or EAC (in a first-degree relative) [16]. Alternatively in the UK, the British Society of Gastroenterology recommends endoscopic BE screening for any gender of patients with chronic GERD symptoms and multiple risk factors (at least three among: age 50 years or older, white race, male sex, obesity)[17]. After BE diagnosis, all of the guidelines recommend a certain uniform timing of surveillance that are determined by presence or absence or detectable dysplasia (no other risk factors considered formally, including patient age), which were proposed by experts [18]. Beyond cost-effectiveness for a small number of microsimulated screening ages [19], the optimal starting age for BE screening is unknown.

Overall, some cancer screening recommendations have been justified by microsimulation models [9] but most screening guidelines consider current epidemiological data alone and are ultimately proposed by and decided by experts. The clinical consequences of these decisions are recorded as population outcomes, and then further research determines how effective these recommendations proved to be. When appropriate randomized control trial data (RCT) are lacking, as is commonly the case in cancer screening [20], we propose that the initial choice of screening design could first be determined as an optimal control problem with a machine learning and/or model-based approach. To address this problem, we derive probability equations to be used for optimal screening/surveillance timing and risk estimation, and present results for BE screening ages using a calibrated mathematical model that reproduces US cancer incidence data. Our predictions are in a cost-effective range and were independently validated with available screening data used for current BE guideline rationale and RCT data using novel sensitive screening technology.

Materials and Methods

In the derivation of our optimal timing framework, we refer to cancer screening as initial testing for the presence of a specified premalignant/malignant change (Barrett’s esophagus (BE) in this case study). A second screen after a negative result is defined as re-screening and subsequent tests after a positive screen are defined as surveillance. If the length of time between preclinical detection of BE and clinical presentation of EAC surpasses patient lifetime, the patient is considered an overdiagnosed case. For cancers with curable precursors, screening programs seek the optimal screening age for which the probability is maximal that 1)individuals in a population harbor a screen-detectable precursor, and 2) this timing occurs before incidental cancers would have developed (Fig. 1A).

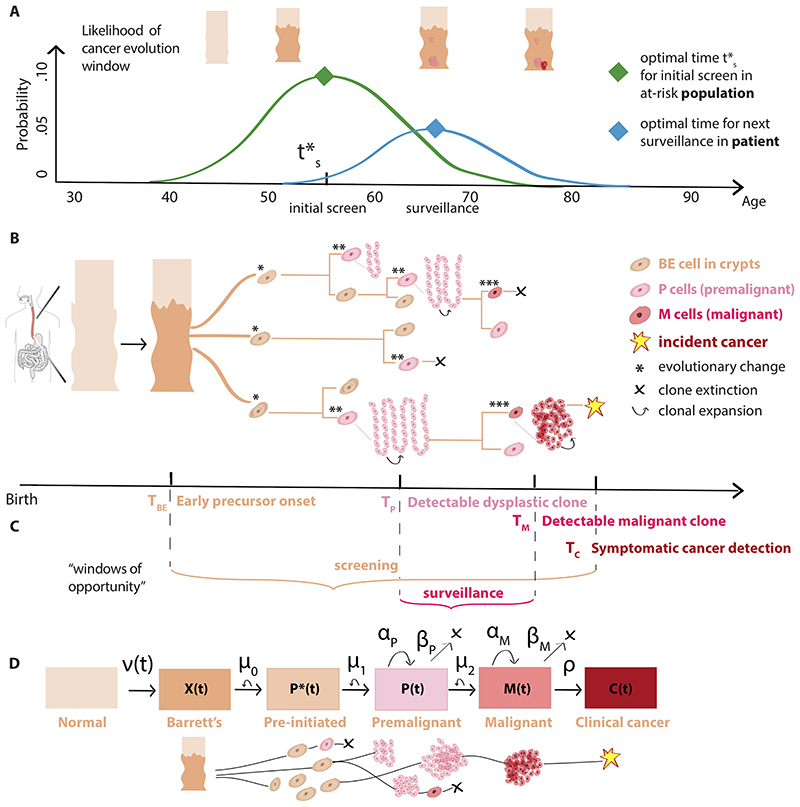

Figure 1. Optimizing screening and surveillance using branching process models of cancer evolution.

(A) After an initial screen to detect premalignant changes at time t’s, adaptive recommendations for patient-specific survei llance can account for the heterogeneity in a screened population. (B) Somatic evolution of stem cell lineages since birth leads to stochastic trajectories (example asymmetric divisions shown on tree nodes) that accumulate mutations and may be selected for advantageous phenotypes. Within an at-risk patient’s esophagus, normal squamous epithelium may transform to a columnar, crypt-filled Barrett’s esophagus (BE) segment. Stochastic initiation of pre-malignant P cells can occur (e.g., after ‘two-hit’ gene inactivation of TP53 in a cancer-promoting microenvironment), which can then undergo clonal expansion. Malignant cells M that are transformed, in turn, may undergo clonal expansions, be detected as a clinical EAC, or go extinct. (C) “Windows of opportunity” for optimal screening and surveillance can be formally defined using random variables T for each stage denoted by subscript (see Supplementary Methods 3.1 for details) to be used in objective functions in (A), example shown specific for BE-EAC pathway. (D) The multi-stage clonal expansion for EAC (MSCE-EAC) model. Model parameters: Transformation rate to X BE cells, ν(t); Pre-initiation Poisson rate, μ0 (P’ progeny); Initiation Poisson rate μ1 (P progeny); Premalignant birth-death-mutation process cell division rate, αp, cell death-or-differentiation rate, βp, malignant transformation rate, μ2; Malignant birth-death-detection process cell division rate, αM, cell death-or-differentiation rate, βM, size-based clinical detection rate, ρ (see Supplementary Methods 3.3 for model fits to cancer incidence).

Biological processes give rise to considerable inter-patient heterogeneity during the progression from normal tissue to incident cancer, and thus optimal timing for surveillance follow-up is expected to be variable within the population based on screening outcome. To account for this heterogeneity in ‘snap-shot’ temporal data, mathematical models that employ a stochastic approach can incorporate and quantify premalignant and malignant clonal expansions during somatic evolution explicitly (Fig. 1B) [21, 22, 23, 24]. This offers the advantage that the onset of precursor clones can be defined as random variables and clonal population sizes can be forecasted into future ages (Fig. 1C).

Previous methods for optimal timing assessment

Population data can provide quantitative benchmarks for certain preclinical states like precursor prevalence but this data alone cannot determine an exact optimal age to initialize screening (and randomized control trials with arms for every starting age in an at-risk population with long-term follow-up are not feasible). To address this, multi-state Markov models have most commonly been used to microsimulate large cohorts of individuals in silico from birth through clinical states of carcinogenesis (boxes in Fig. 1D, for example) to quantify expected outcomes (i.e., natural history). Model rates are inferred by fitting to cancer incidence and mortality data [25], or fitting to screening trial data explicitly [26]. Then with a calibrated model, screening processes are built into microsimulations to compare strategies based on beneficial outcomes from interventions and to quantify associated costs such as numbers of expected surveillance exams. For our specific health policy question of interest for determining the optimal screening age, simulation models have been used in numerous examples: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in the US by testing 3 starting ages (45, 50, or 55) [27], American Cancer Society recommendations for CRC screening by testing 3 starting ages (40, 45, or 50) [28] and recently for one-time CRC screening using single ages from 50 to 65 [29]; for lung cancer screening in the US by testing 4 scenarios of initial age (45, 50, 55, or 60) [30]; and for Barrett’s esophagus screening to reduce esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) by testing 3 starting ages (50, 60, or 70) [19].

While simulation models have assessed particular screening ages, they can only identify cost-effective strategies among those finite number tested and results are often sensitive to numerous inputs and assumptions. Alternatively, mathematical models can search for a global optimum given an objective (utility) function (see [31, 32, 33] for methodologies using discrete clinical states). We extend this type of approach to biomathematical models that include temporal dynamics of cancer evolution detailed above, which simultaneously reproduce cancer incidence patterns. Thus far these types of stochastic models have been used in simulation studies on screening [21, 18, 34] but not in an optimization algorithm that does not require simulation. Here we formulate the novel combination of an evolutionary-based, analytical approach to be used for optimizing timing for early cancer precursor detection.

Case study in Barrett’s esophagus

For specific optimal timing examples presented in Results, we apply our methods to Barrett’s esophagus (BE). For this we utilize the multistage clonal expansion for esophageal adenocarcinoma (MSCE-EAC) model that has been employed within the NCI Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) for cost-effectiveness studies of EAC prevention ([25, 35, 18], see Fig. 1). The random variables described below can be formulated (and expanded) for multistage models in esophagus, colon, lung, breast, and others (see Fig. 1C, and Supplementary Methods 3.1 - 3.2 for derivations). We present the methods for 3 clinical scenarios: (1) Initial screening, (2) Re-screening based on negative screen, and (3) Surveillance based on positive screen. In each scenario, we define the “window of opportunity” for the desired target and the objective (utility) function used to compute optimal times (ages). For initial screening, we present examples for associated costs. For surveillance, we define the age-dependent risk of future cancer.

1. Optimizing initial screening

The probability for the screening “window of opportunity” is defined as the probability that a specific age is both between the onset of precursor BE and cancer, and that the age is also younger than time of patient death (Fig. 1C, beige). Here we incorporate realistic cutoff times due to life expectancy in our framework by using life table estimates for US all-cause mortality survival probabilities [36]. We then define a screening objective function of age, which is the difference between the probabilities the patient has already developed BE and that the patient has already developed EAC (i.e., the patient is in the window of opportunity), weighting the relative differences by a factor, w, and multiplied by the probability the patient is alive at that age. This variable weighting allows policy makers to decide how much to value avoiding underdiagnosis versus avoiding costs associated with overdiagnosis. We then solve for the optimal screening age that maximizes the screening objective function (see Supplementary Methods 3.4 for explicit solution). For examples of two other potential “windows of opportunity” to use as targets for screening, see Supplementary Methods 3.5 - 3.6.

Calculating costs of different screening ages

Once an initial screening age is determined, we present two examples of associated cost functions. First, we define a cost function for screening at each age and surveillance until some fixed final age at which time surveillance is discontinued even if the patient remains alive. This first cost quantifies the number of patient-years expected from needless surveillance of the overdiagnosed population (the “over-screened” fraction of patients diagnosed with precursor BE who will not get cancer before the fixed final age of discontinuing surveillance). Following from this, we define a second cost for the number of futile exams among the overdiagnosed BE cases (see Supplementary Methods 3.4 for derivation).

2. Optimizing re-screening

After a negative (normal) screen, the patient may be asked to return for repeat screen at a later time. We define a new probability for the re-screening “window of opportunity” similar to the one for the first screening above, conditional on the outcome of the first screening. We likewise define a re-screening objective function with similar weighting of over- vs underdiagnosis, w, and solve for the optimal re-screening age (see Supplementary Methods 3.8 for explicit solution).

3. Optimizing surveillance

After a positive screen (precursor detected), most clinical guidelines recommend fixed follow-up intervals without incorporating risk factors of patient progression (e.g., gender, uncontrolled GERD). Alternatively in adaptive surveillance, we make mechanistic predictions conditional on patient demographic/clinical features and detected stage of progression at each specific screening age to provide more refined surveillance. The idea is to iteratively condition on the screening/surveillance result at a patient’s age and derive an interval for the next surveillance given some outcome of interest, to then obtain the optimal age for the next surveillance. If the screening/surveillance result states that no later stages of neoplasia were detected, the probability for the next-surveillance “window of opportunity” is defined as the probability that the surveillance age is both between the ages of having detectable premalignancy and having malignancy of any size, and younger than time of patient death (Fig. 1C, pink). Similar to above, we derive the optimal next-surveillance age as the age that maximizes the corresponding surveillance objective function with similar weighting of over- vs underdiagnosis, w (see Supplementary Methods 3.9 for full solution when precursor onset is known).

Calculating risk for surveillance

In general, a physician will often not know how long a patient has harbored undetected cancer precursors in the body, only that onset occurred sometime before screening. But if we are able to measure this precursor onset age (for example, through measuring a molecular age of a precursor), then his/her associated cancer risk for next-surveillance age could instead be specifically defined in terms of the precursor onset age (e.g., BE onset; equivalently, BE dwell time or BE age) rather than the patient’s years since birth (patient age). See Supplementary Methods 3.10 for explicit solution.

Data

For results on Barrett’s esophagus (BE) screening, we apply the methods above for the MSCE-EAC model specifically. The model inputs only include (1) GERD prevalence (modeled from data for age- and sex-specific estimates), and (2) EAC age- and sex-specific incidence curves provided by Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry [35]. The BE prevalence and neoplastic progression rates are model outputs, i.e. they are not fit to observed BE prevalence nor neoplastic progression rates from empiric studies.

Previous calibration to SEER cancer incidence data

The cell-level description of evolution in this model is linked to the population scale by means of the model hazard function, defined as the instantaneous rate of detecting cancers among individuals who have not been previously diagnosed with cancer [35]. Briefly, the hazard function can be derived from the backward equations for the stochastic multistage branching process described above and solved numerically via a system of coupled ordinary differential equations (Supplementary Methods 3.3). Thus, one may infer rates of cellular processes shown in Fig. 1D from cancer incidence data. From previous rigorous model selection we found the best model was birth cohort-specific (see [25, 35] for previous results using EAC incidence data from the SEER9 registry 1975-2010, with predicted trends to 2030). Parameters used as input data for the case of BE screening are provided in Supplementary Table S1. We separate all results considering sex as a biological variable.

Validation using population prevalence data

The results below include predictions for optimal screening ages that are not fit to screening data explicitly, but are outputs of the model fit to cancer incidence. While population data is conditional on patient survival, our aim was to calculate an optimal window (i.e., joint probabilities) for which no perfectly comparable data exists. Rather, to test the accuracy of our model, we recently validated the simultaneous predictions of BE prevalence (our main target population for screening) using the MSCE-EAC model with various independent data from population-based studies [14]. In that study we also found that our simultaneous model estimates for cancer progression corresponded with published progression rates from non-dysplastic BE to EAC.

Here we include two main validation datasets that are relevant for our optimization problem. First, a main study currently used for screening rationale included age- and sex-specific data from the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) [37]. This data included endoscopic reports for more than 150,000 patients, most of whom were born around 1950 with no prior EAC, stratified by GERD symptoms as indicated in the endoscopy report. To directly compare the CORI prevalence with our model that depends on BE onset rate ν(t) (Fig. 1), we derive the analogous conditional probability to represent the data, which was computed as the fraction of firs-ttime diagnosed BE cases by age within the total patient cohort in CORI who underwent first endoscopy between 2000-2006 (see Supplementary Methods 3.7). Secondly, we compared our results to prospective, randomized control trial (BEST3) BE prevalence data for patients who were screened with sensitive technology Cytosponge-TFF3. Eligible patients in BEST3 were 50 years of age or older, had been taking acid-suppressants for GERD symptoms for over 6 months, and had not undergone an endoscopy procedure within the previous 5 years [38]. To compare our birth-cohort specific model predictions with similarly aged cohorts included in most available studies (including BEST3), we present main results for the US population born in 1950 (as in previous cost-effectiveness analyses of BE screening [19, 25, 35, 18]), and show that results are similar for modern birth cohorts in a 50-year range.

Results

We applied our optimal timing framework to Barrett’s esophagus (BE) for the scenarios of initial screening, re-screening, and surveillance, to obtain theoretical predictions a priori without relying on microsimulations.

Optimal ages to initialize screening for Barrett’s esophagus

Our first aim was to optimize the choice of recommended age to start screening in US populations that would capture the most BE patients before they have progressed to EAC (optimal window in Fig. 1C, beige). All current guidelines that specify an age to begin screening assume age 50 as the threshold across all risk groups but this choice was not based on any optimization process [15]. In our optimal control framework (see Materials and Methods), we achieve this by maximizing the screening objective function, thus obtaining optimal screening ages.

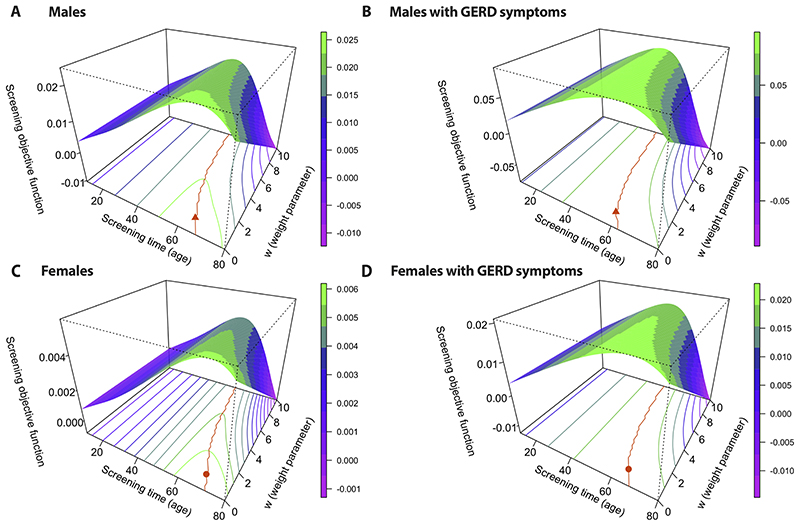

In line with currently considered risk factors in guidelines, we computed the screening objective functions stratified by age, sex, and GERD status (i.e., general population or symptomatic GERD population). Fig. 2 depicts the contour plots of these objective functions along with predicted optimal ages for each weight parameter w (orange lines). We sought ages by whole years for simplicity, in the way that guidelines are formulated currently. For w = 1 (equal weighting of positive screen and safeguarding from cancer before screening), the optimal screening times were 64 years old for all males (Fig. 2A orange triangle), 58 years old for males with GERD symptoms (Fig. 2B orange triangle), 69 years old for all females (Fig. 2C orange circle), and 64 years old for females with GERD symptoms (Fig. 2D orange circle). As incrementally greater weight, w, is given to avoiding underdiagnosis than avoiding overdiagnosis, the optimal screening ages become younger (orange lines).

Figure 2. Predicted optimal ages to screen.

The screening objective function is plotted along the z-axes for screening age between ages 10 and 80 and weighting parameters w between 0 and 10 (see Materials and Methods) in certain populations: men in general population (A), men with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms (B), women in general population (C), and women with GERD symptoms (D). The orange line on each 2D contour plot denotes optimal screening ages (obtained by maximizing the screening objective function for each weight, w), for US populations, all races. Orange symbols indicate optimal screening ages for w = 1.

Table 1 provides results on predicted optimal screening ages along with associated metrics of efficacy. Optimal screening ages depend on an a priori choice of parameter w, which can be chosen such that the risk of EAC before age of screening is below a tolerable level. We found the example for the proper probability for optimal window for screening (see Materials and Methods) with w = 1 had low associated risk of EAC before optimal ages (Table 1, final column), so we present further Results also for w = 1.

Table 1. Predicted optimal screening ages for BE in GERD and general populations.

| Risk group | Sex | Optimal age (95% CI) | SD | OD | PPV | Cancer risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Male | 64 (63 - 66) | 99.5% | 2.4% | 16.8% | 0.17% |

| GERD | Male | 58 (56 - 60) | 99.6% | 7.1% | 28.6% | 0.37% |

| General | Female | 69 (68 - 71) | 100 % | 0.6% | 9.6% | 0.04% |

| GERD | Female | 64 (59 - 67) | 100 % | 1.9% | 17.9% | 0.11% |

Model predictions for optimal screening ages and associated metrics for w = 1 (see Supplementary Methods 3.7 for derivations): successful diagnoses (SD) predictive of future EAC cases up to fixed age 80, overdiagnoses (OD) of non-EAC cases, positive predictive value (PPV), and the risk of cancer occurring before the screening age recommendations (see Supplementary Methods 3.4 for risk equation) for US persons, all races, stratified by sex and GERD symptom status. Abbreviation: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Validation of model predicted optimal ages

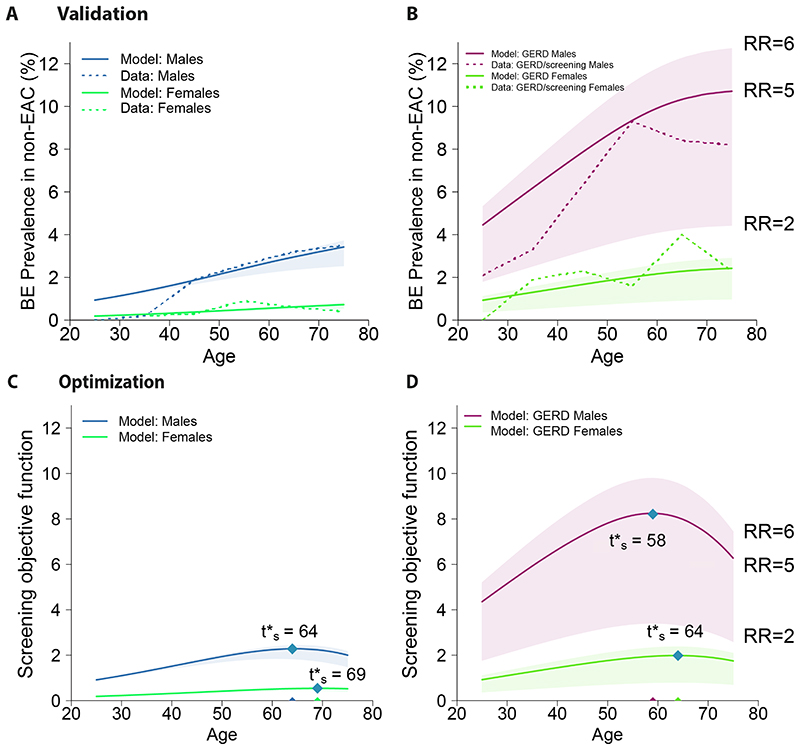

We computed BE prevalence for risk strata in Fig. 2 as predicted by our model (which was only fit to SEER incidence data) to compare with independent published data (see Materials and Methods, Fig. 3A,B). To account for likely heterogenous relative risk (RR) of developing BE in GERD populations based on symptom onset age, BE length, and other factors [14], we considered a range of fixed values (RR = 2-6, Fig. 3A shaded areas) and found age-specific trends broadly consistent with overall BE prevalence results in Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) [37]. Further, we confirmed a main result from Rubenstein et al. that women with GERD (Fig. 3B, green lines) were at no increased risk compared with men without GERD (Fig. 3A, blue lines) and thus, if screening were considered, it should be recommended at the same age. In the pragmatic randomized control trial BEST3 for BE screening, 1750 patients who underwent the screening procedure (8 patients with prior BE were excluded), 127 total were diagnosed with BE by 12 months (weighted overall average) after enrollment (7.3% prevalence with no concurrent esophago-gastric cancer) [38]. Of the 1654 patients with a successful procedure, 52% were women and the median age was 69 years old. Similarly, our model predicted the BE prevalence at age 69 for a GERD population with 52% women was 6.3%, assuming a fixed 5-fold relative risk of BE in the GERD population (RR = 5, [39]). Thus BE prevalence found in BEST3 was slightly higher than our model’s estimate; one reason for this, as the authors note, could be that the 1750 participants who agreed to undergo the Cytosponge-TFF3 procedure might have had more problematic symptoms than the average GERD patient [38].

Figure 3. Validating predicted prevalence and optimizing screening ages.

(A) Model predictions for BE prevalence in general US population stratified by sex, with contributions of relative risk (RR) of BE from the prevalent GERD subpopulation assumed to be RR=5, solid lines (shaded areas, RR=2-6). Dashed lines are BE prevalence data from CORI [14]. (B) Model predictions for BE prevalence in GERD populations with fixed values assumed for range of RR since birth (RR=2-6). CORI data (dashed lines) corresponds with model’s expected predictions for true GERD-specific BE prevalence contributing to subpopulation in (A) that would lie within shaded regions for men and women due to heterogeneity in GERD onset ages. For analogous age-specific populations, bottom row depicts optimization results from screening objective function (see Materials and Methods) with w = 1 in (C) general populations and (D) symptomatic GERD populations, including single age results for optimal initial screening age t’s (blue diamonds). Abbreviation: esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC)

For previous guidelines, the decision for age to screen has been essentially made ad hoc considering such prevalence data that is conditional on being cancer-free and alive, and grouped into decade age-groups [37]. Our model estimates for this were consistent with these studies [14] but did not address optimality. We therefore computed the corresponding joint probability of being cancer-free and alive (captured in the relevant objective functions to optimize, Fig. 2) for any age in general population (Fig. 3C) and subpopulation with GERD symptoms (Fig. 3D). Importantly, we found that identical optimal screening ages were predicted for men and women with GERD for a broad range of relative risks (RR = 2-6) of developing BE (Fig. 3D). Thus, although we allow for heterogeneous relative risk of BE in GERD patients resulting in a plausible range for BE prevalence (Fig. 3B, shaded regions), the optimal age for screening was the same across these high-risk individuals.

Optimal screening ages can decrease over-surveillance and costs vs. ad hoc guidelines

For symptomatic GERD males (highest risk group tested), we next compared the costs associated with the initial screen age of 50 (current practice) versus our predicted optimal age of 58. For both screening ages 50 and 58 in GERD men, there was less than 0.4% risk of screening too late (i.e., very few men who develop EAC will do so before those screening ages). Thus, the current cost burden for EAC cancer control is likely attributable more so to years of futile surveillance than costs associated with missed cases. We estimated the number of patient-years of over-surveillance (see Materials and Methods) of overdiagnosed BE cases in x number of individuals surveilled up to fixed age 80. For screening age 50, we computed 1.68x patient-years, and for optimal screening age 58, 1.52x patient-years. This implies that if we screened the roughly x = 400, 000 US men with GERD from the 1950 birth cohort at-risk at those specific ages, the overall costs associated with screening at optimal age 58 were estimated to be 64,000 patient-years less spent on futile surveillance for this birth cohort alone than what would be expected for screening at age 50; this is due to the savings gained from eliminating 8 years of exams in a large number of middle-aged patients who will not progress to EAC [40].

We also estimated the resulting number of futile endoscopies (esophagogastroduodenoscopies; EGDs) in these overdiagnosed patients with BE in x number of individuals screened (see Materials and Methods). Here we previously estimated in a cost-effectiveness analysis of current BE surveillance that the number of endoscopies per BE patient per year post-diagnosis was equal to 0.4 (see [18], Table E2). Therefore by fixed age 80, we computed 0.67x EGDs for screening age 50, compared to 0.61x EGDs for optimal screening age 58. Thus, if we screened x = 400,000 GERD men from the 1950 birth cohort, the number of futile endoscopies due to screening at optimal age 58 were estimated to be 24,000 less than expected with current practice for screening at 50. Assuming an EGD costs $745 USD [19], this implies a savings of $17.9 million for this birth cohort alone when choosing the optimal age to start screening recommendation versus current practice. In reality, this is a lower bound for savings that does not include costs for treatment of dysplastic lesions found during lifelong surveillance of each additional overdiagnosed case. The cost savings also increase proportionally when applied to additional birth cohorts beyond just that of 1950.

Less than 3% of normal patients will be found with BE on re-screen

When a patient is screened for suspected BE and is normal, an important decision for clinicians is whether to suggest that this patient come back for a re-screen at a later age and if so, at what age they should return. Current guidelines do not advise re-screening unless a patient is healing from esophagitis wounding to ensure underlying BE was not missed initially [16]. This recommendation was based on a CORI study that found 2.3% of patients with an initial negative screen had BE on repeat examination, implying that BE is rarely missed and develops early in patients on surveillance [41]. With our methods we can quantify: (1) when is the best age to offer a second screen, and (2) how likely it would be that BE would be found at that age.

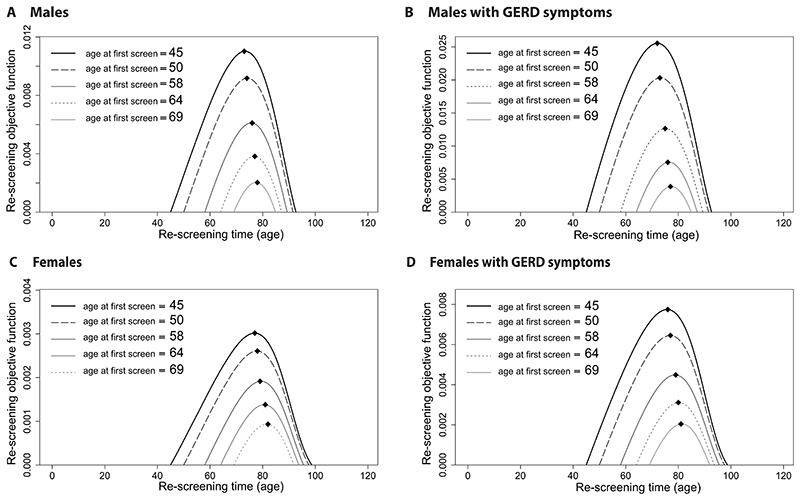

We optimized when to screen this individual again at a later age when he/she is most probable to have developed BE by this time but not yet clinical cancer. Given a range of initial screening ages (age = 45, 50, 58, 64, 69), we computed the re-screening objective functions to maximize (Fig. 4). The black diamonds depict the optimal re-screening ages for the US population, all races, born in 1950. For our choices of initial screening age in ascending order, we found that corresponding optimal timing for follow-up screens were ages 73, 74, 76, 77, 78, for all males (Fig. 4A); ages 72, 73, 75, 76, 77, for GERD males (Fig. 4B); ages 77, 78, 79, 81, 82, for all females (Fig. 4C); and ages 76, 77, 79, 80, 81, for GERD females (Fig. 4D). Thus, even though initial screening times may be over 20 years apart, the optimal range of a follow-up screen was only within a 5 year window.

Figure 4. Optimal ages to re-screen after negative BE screen.

The re-screening objective functions to maximize, given prior screening age 45, 50, 58, 64, 69, are denoted for weighting w =1 (including typical case for current practice, screening age 50, shown in dashed lines). Optimal re-screen ages shown for all races, born in 1950 (diamonds). For the risk group-specific optimal first screening ages (dotted lines), the optimal re-screen ages were (A) 77 for all males, (B) 75 for GERD males, (C) 82 for all females, and (D) 80 for GERD females.

Our estimates for these probabilities of BE yield on re-screen were very close to those found for re-screening both genders in CORI [41], further validating our predictions of screening outcomes and yields based on continuous age. Importantly, we found that the initial age of screening (rather than time since initial screening) affects the future probability of BE yield; such information is not currently considered when clinicians decide whether certain GERD patients should return to be re-screened. For example we found that, if initial screening took place for GERD males at age 58, there would be a 1% chance of a positive re-screen rather than 2-3% when screening first at age 50. Importantly, even this 1% will be mostly overdiagnoses as de novo BE is much less likely to have time to develop to EAC within the remainder of patient lifespan, thus further devaluing a re-screen after initial negative result.

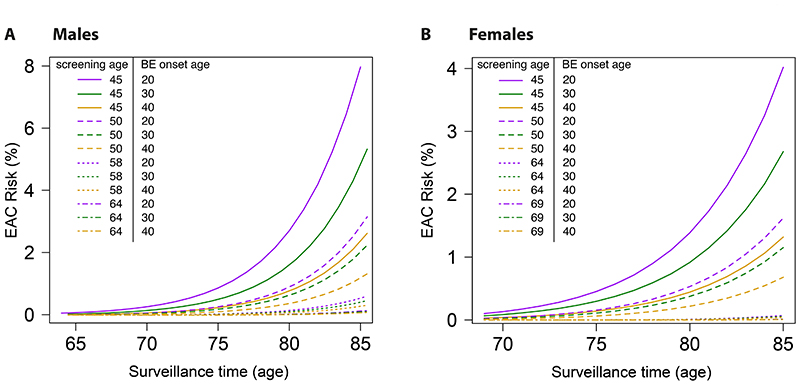

Accurate cancer risk prediction depends on premalignant molecular age

When a patient has a positive BE screen but no neoplasia (HGD/malignancy) at the first screening age, current guidelines suggest these patients return for surveillance every 3-5 years [16, 17] because they still carry risk of EAC that may in fact increase with time regardless of persisting without a diagnosis of dysplasia [42]. Furthermore, non-dysplastic BE patients with “missed” HGD/EAC were significantly older than those who later progressed [43], suggesting the important role age plays as a significant risk factor indicating missed EAC and the need for surveillance of BE patients who have unknowingly harbored BE for longer than younger patients. This prompts the question whether patient-specific BE “dwell time” influences future neoplastic risk.

If we measured BE onset age for a patient with BE diagnosed at some years after onset (e.g., via methylation-based molecular clocks [44]), we can predict with the model his/her associated EAC risk for given next surveillance age (see Supplementary Methods 3.10). We used the model to predict future EAC risk up to age 85 with prior screening ages 45, 50, 58, 64 for males (Fig. 5A), and 45, 50, 64, 69 for females (Fig. 5B). The model predicted that in general the associated EAC risk for those that developed BE earlier in life is greater than the risk for those BE patients who developed BE later in life. For the screen performed at age 50 (dashed lines) in both sexes, the BE patient who developed BE at age 20 (purple line) has a 2.4 predicted relative EAC risk versus the BE patient who developed BE at age 40 (yellow line). Currently in clinical practice however, these two patients would likely be treated equally because they were diagnosed at the same age. Our findings reiterate that knowledge of BE onset ages may translate to large differences in EAC risk [44].

Figure 5. Predicted cancer risk after positive BE screen.

The EAC risk is plotted for each choice of surveillance age until age 85, given the prior screening age (denoted by line type) 45, 50, 58, 64 for males (A) and 45, 50, 64, 69 for females (B), and a BE onset age of 20, 30, or 40 (denoted by color).

Sensitivity of predictions

Our multistage model was calibrated to population incidence data [35] and has been previously tested to quantify the effects of perturbations in model parameters in Supplementary Table S1 (see details in [25, 45, 46]). Similarly here, we tested our model and found that our optimal timing predictions are robust to perturbations in parameters (Table 1) as calculated in a bootstrap analysis of 1,000 re-sampling iterations of the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) posterior distributions for each calibrated parameter (Supplementary Fig. S1A).

We also found that screening optimization predictions are robust through modern birth cohorts in a 50 year range (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Specifically, we considered 5 additional modern birth cohorts beyond the 1950 base case and found that: (1) Optimal screening ages remain unchanged for males (GERD and general populations) born between 1950 and 2000, and (2) similar results to the base case were found for females. Specifically, optimal screening ages varied between these cohorts by only 3 years in females with GERD and 2 years for the general female population (Supplementary Fig. S1B). This is consistent with findings from the CORI study that BE prevalence estimates at index endoscopy show only a small secular age-specific trend in index BE prevalence in white male GERD screenees but no trend in women across the calendar year period years 2000-2006 [37].

Discussion

Mathematical models of cancer evolution are being widely developed to understand timing of events and dynamics of carcinogenesis. In this study, we applied such models to optimize screening and surveillance. Examples that could be applied within our framework include Markov models for natural history of disease [30, 47, 48], biologically-based models that incorporate dynamic processes [21, 34, 24, 25, 49, 50], and biological event timing models that infer ordered genetic events [51]. Our mathematical formalism provides one means of targeting distinct latency periods, or “windows of opportunity” and the specified weight w for the adverse event to suit the purpose of the health policy goal.

Unlike previous studies on screening that incorporated microsimulation of clonal evolution [21, 34], this study provides an analytical framework that does not require simulation to determine the specific age to screen (and whether to screen) for cancer precursors. Microsimulation models have previously been used to inform policy-making decisions on screening, but the optimal design framework developed here offers computational advantages and strengths based on theory that can complement and enhance simulation methods. In particular, microsimulations of many hypothetical scenarios can be time-intensive, prone to sensitivities in parameter choices, and ultimately only test a finite number of options [52]. In contrast, we showed that successful screening probabilities can be analytically solved in certain cases and that these equations 1) are straightforward to optimize in a single computation, 2) reveal model assumptions that have the greatest implications on the sensitivity of the results obtained, and 3) predict future trends to obtain results for younger birth cohorts in a data-driven way.

In the case of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), screening has been recommended to begin in patients with multiple risk factors including increasing age (the specific threshold is 50 years of age), but the clinical evidence for these recommendations has been low to moderate in quality [15]. An appropriate RCT to test proposed screening ages is not practical so cost-effectiveness studies have mainly relied on in silico evaluations of specific screening scenarios [18]. While these models have tested a small number of screening cohorts, we considered the full range of screening ages and found that the optimal ages to begin screening patients with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) were age 58 for men and 64 for women. Importantly, the corresponding BE prevalence estimates predicted by the model align with population studies [14], and here we specifically validated such estimates considering both data used in guideline formation for starting age [37], along with recent data from randomized control trial BEST3 [38]. The optimal age predictions are still within cost-effective ranges found for men with GERD in previous modeling analyses that compared screening ages 50, 60, and 70 [19, 53], particularly when using minimally invasive, cheaper screening modalities in both men and women [19]. We found that an earlier screening age of 50 was more costly to healthcare for men with GERD due to overdiagnoses, while we expect a 9% reduction in total future BE surveillance endoscopies (and 10% reduction in total patient-years of needless surveillance) if screening took place at later age 58. Although incidental EAC cases between ages 50-58 are rare compared to those in 59+ age group, costs due to underdiagnosis of BE that would progress to EAC in this 8 year range could be considered, but would also be counterbalanced against over-treatment of small indolent lesions detected on surveillance.

For the general population, we found that the optimal ages to recommend screening were age 64 for men and age 69 for women (for equal weighting given to BE onset and EAC risk in optimization). These findings for the ages of optimal BE yield are supported by prospective studies’ results that it is more likely to find BE during screening at ages closer to 60 than 50 [54], specifically in two large studies that found the same mean age at BE diagnosis of 61 in men [55], and 61 in both genders together [56]. Lastly, women found with BE were more likely to be older, between ages 61 to 70 at diagnosis, than women found without BE [57, 58]. Taken together, these studies confirm our findings that it may be justified biologically to begin screening at these later ages. These proposed older ages to initialize screening in GERD and general population could be specifically tested in future cost-effectiveness analyses.

Our model describes a number of key transitions in cell biology, each defined by a specific rate parameter. Direct measurement of these parameters is usually lacking, and indeed there remains uncertainty about what key rate-limiting transitions in cancer evolution are essential. Nevertheless, we estimated a tight range for optimal screening ages in our sensitivity analysis with varying cell-level rate inputs, and identical optimal ages for GERD patients when assuming a wide range of published estimates for relative risk of developing BE in this high-risk group. With respect to effective surveillance, we did find that molecular age of precursors (beyond patient chronological age at time of screening) was a critical variable for accurate cancer risk prediction given screening outcome [59]. Because the framework is predicated on a biological description of the natural history of cancer, the inferences drawn are predictive and will need to be validated prospectively even though the underlying mechanistic model framework was validated using available screening data. In particular, additional data on age-specific BE prevalence in GERD populations is needed to strengthen model validation. This approach complements the development of adaptive treatment strategies (ATS) and dynamic treatment regimen (DTR) that rely on large amounts of patient-specific health records and machine learning [60]. Although these new developments are likely to yield important insights considering the wealth of clinical records for common diseases, they are difficult to extend to rare or understudied diseases and therefore are prone to biases. In contrast, models borrow strength from incidence patterns and are easily interpretable and applicable to balance risks with benefits when there is an intention to treat or intervene.

While it is difficult to justify delaying screening from a public health perspective, the problem of overdiagnosis is only becoming larger as fervor for early detection assays continues to grow. Our study’s predictions are reasonable considering the scarcity of epidemiological data that support earlier screening. We show that using a mechanism-based model of cancer could help relieve the costs of unnecessary screening and surveillance, though further validation of associated risks and sensitivities is needed. Overall such approaches are currently under-utilized in public health policies related to cancer screening. Here we demonstrate the potential to inform guidelines through deeper mathematical examination of data for cancers where screening can be life-saving. As “learning cancer screening programs” are being proposed to test many potential strategies in populations via randomized screening arms [20], we suggest that incorporating a model-based approach from the outset could aid in an optimal design plan (such as screening age choice in certain risk strata) to significantly improve health outcomes at acceptable costs.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Our study demonstrates how mathematical modeling of cancer evolution can be used to optimize screening regimes, with the added potential to improve surveillance regimes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov) under grants U01 CA152926, U01 CA199336 (CISNET; K Curtius, GE Luebeck, WD Hazelton, JH Rubenstein), U01 CA182940 (BG-U01; GE Luebeck, WD Hazelton), U54 CA163059 (BETRNET; JH Rubenstein), and UKRI Rutherford Fund Fellowship (K Curtius). The authors thank Professor Trevor Graham for helpful discussions during the writing of this manuscript. The authors also thankfully acknowledge the National Endoscopic Database of the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) for raw data on Barrett’s esophagus prevalence.

Financial support

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov) under grants U01 CA152926 (CISNET), U01 CA182940 (BG-U01), U54CA163059 (BETRNET), and U01CA199336 (CISNET), and UKRI Rutherford Fund Fellowship (KC).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Code and data availability

All analytical distributions to recreate our Results (data in Supplementary Table S1) and apply to other data are available in the Text and Supplementary Data. Code to solve equations was developed in R (version 3.6.1) and is publicly available at: github.com/yosoykit/OptimalTimingScreening. CORI data can be accessed through application with ethical approval to NIDDK: https://niddkrepository.org/studies/cori/.

References

- [1].Wender RC, Brawley OW, Fedewa SA, Gansler T, Smith RA. A blueprint for cancer screening and early detection: Advancing screening’s contribution to cancer control. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:50–79. doi: 10.3322/caac.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Fedewa SA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:297–316. doi: 10.3322/caac.21446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481:306–13. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hu Z, Ding J, Ma Z, Sun R, Seoane JA, Shaffer JS, et al. Quantitative evidence for early metastatic seeding in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1113. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0423-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Williams MJ, Werner B, Heide T, Curtis C, Barnes CP, Sottoriva A, et al. Quantification of subclonal selection in cancer from bulk sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2018;50:895–903. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0128-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhang J, Cunningham JJ, Brown JS, Gatenby RA. Integrating evolutionary dynamics into treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Nature Commun. 2017;8:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01968-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Park DS, Robertson-Tessi M, Luddy KA, Maini PK, Bonsall MB, Gatenby RA, et al. The goldilocks window of personalized chemotherapy: Getting the immune response just right. Cancer Res. 2019;79:5302–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rockne RC, Hawkins-Daarud A, Swanson KR, Sluka JP, Glazier JA, Macklin P, et al. The 2019 mathematical oncology roadmap. Phys Biol. 2019;16:041005. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/ab1a09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].US Preventive Services Task Force. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman D, Curry S, Davidson K, Epling J, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:2564–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Moolgavkar SH. Commentary: Multistage carcinogenesis and epidemiological studies of cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:645–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Luebeck EG, Moolgavkar S. Multistage carcinogenesis and the incidence of colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15095–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222118199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wenker TN, Tan MC, Liu Y, El-Serag HB, Thrift AP. Prior diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is infrequent, but associated with improved esophageal adenocarcinoma survival. Digest Dis Sciences. 2018;63:3112–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5241-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Prasad G, Bansal A, Sharma P, Wang K. Predictors of progression in Barrett’s esophagus: current knowledge and future directions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1490–502. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Curtius K, Rubenstein JH, Chak A, Inadomi JM. Computational modelling suggests that Barrett’s oesophagus may be the precursor of all oesophageal adenocarcinomas. Gut. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Patel A, Gyawali CP. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus: Balancing clinical value and cost-effectiveness. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25:181. doi: 10.5056/jnm18156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB. ACG clinical guideline: Diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. The American Journal Of Gastroenterology. 2016;111(1):30–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, Ang Y, Kang J-Y, Watson P, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kroep A, Heberle CR, Curtius K, Kong CY, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ali A, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus reduces esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality in a comparative modeling analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1471–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Heberle CR, Omidvari AH, Ali A, Kroep S, Kong CY, Inadomi JM, et al. Cost effectiveness of screening patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease for Barrett’s esophagus with a minimally invasive cell sampling device. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kalager M, Bretthauer M. Improving cancer screening programs. Science. 2020;367:143–4. doi: 10.1126/science.aay3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jeon J, Meza R, Moolgavkar S, Luebeck EG. Evaluation of screening strategies for pre-malignant lesions using a biomathematical approach. Math Biosci. 2008;213:56–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ryser MD, Lee WT, Ready NE, Leder KZ, Foo J. Quantifying the dynamics of field cancerization in tobacco-related head and neck cancer: a multi-scale modeling approach. Cancer Res. 2016;76:7078–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dhawan A, Graham TA, Fletcher AG. A computational modeling approach for deriving biomarkers to predict cancer risk in premalignant disease. Cancer Prev Res. 2016;9:283–95. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lang BM, Kuipers J, Misselwitz B, Beerenwinkel N. Predicting colorectal cancer risk from adenoma detection via a two-type branching process model. PLoS Comput Bio. 2020;16:e1007552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Curtius K, Hazelton WD, Jeon J, Luebeck EG. A multiscale model evaluates screening for neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wu D, Kafadar K, Rai SN. Inference of long-term screening outcomes for individuals with screening histories. Statistics and Public Policy. 2018;5:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, Naber SK, Doria-Rose VP, Pabiniak C, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:2595–609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Peterse EF, Meester RG, Siegel RL, Chen JC, Dwyer A, Ahnen DJ, et al. The impact of the rising colorectal cancer incidence in young adults on the optimal age to start screening: microsimulation analysis I to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer. 2018;124:2964–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen C, Stock C, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Optimal age for screening colonoscopy: a modeling study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:017–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].de Koning H, Meza R, Plevritis SK, Ten Haaf K, Munshi VN, Jeon J, et al. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160L:311–20. doi: 10.7326/M13-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ahern CH, Cheng Y, Shen Y. Risk-specific optimal cancer screening schedules: an application to breast cancer early detection. Stat Biosci. 2011;3:169–86. doi: 10.1007/s12561-011-9032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dewanji A, Biswas A. An optimal design for simple illness-death model. J Stat Plan Infer. 2001;96:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Parmigiani G, Skates S, Zelen M. Modeling and optimization in early detection programs with a single exam. Biometrics. 2002;58:30–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hanin L, Pavlova L. Optimal screening schedules for prevention of metastatic cancer. Stat Med. 2013;32:206–19. doi: 10.1002/sim.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kong CY, Kroep S, Curtius K, Hazelton WD, Jeon J, Meza R, et al. Exploring the recent trend in esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality using comparative simulation modeling. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:997–1006. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Arias E. United States life tables, 2008. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System. 2012;61:1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Rubenstein JH, Mattek N, Eisen G. Age-and sex-specific yield of Barrett’s esophagus by endoscopy indication. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, Maroni R, Muldrew B, Debiram-Beecham I, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify barrett’ s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:333–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Taylor J, Rubenstein J. Meta-analyses of the effect of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux on the risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1730–37. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Day JC. Population projections of the united states by age, sex, race, and hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050. U.S. Bureau of the Census; 1996. pp. 25–1130. (Current Population Reports). [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rodriguez S, Mattek N, Lieberman D, Fennerty B, Eisen G. Barrett’s esophagus on repeat endoscopy: should we look more than once? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1892. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01892.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Krishnamoorthi R, Ramos GP, Crews N, Johnson M, Dierkhising R, Shi Q, et al. Persistence of nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus is not protective against progression to adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:950–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].van Putten M, Johnston BT, Murray LJ, Gavin AT, McManus DT, Bhat S, et al. ‘Missed’ oesophageal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus patients: A large population-based study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:519–28. doi: 10.1177/2050640617737466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Curtius K, Wong C-J, Hazelton WD, Kaz AM, Chak A, Willis JE, et al. A molecular clock infers heterogeneous tissue age among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Luebeck EG, Curtius K, Jeon J, Hazelton WD. Impact of tumor progression on cancer incidence curves. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1086–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hazelton WD, Curtius K, Inadomi JM, Vaughan TL, Meza R, Rubenstein JH, et al. The role of gastroesophageal reflux and other factors during progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015:cebp-0323. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0323-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ryser MD, Worni M, Turner EL, Marks JR, Durrett R, Hwang ES. Outcomes of active surveillance for ductal carcinoma in situ: a computational risk analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv372. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Altrock PM, Ferlic J, Galla T, Tomasson MH, Michor F. Computational model of progression to multiple myeloma identifies optimum screening strategies. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018;2:1–12. doi: 10.1200/CCI.17.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hori SS, Lutz AM, Paulmurugan R, Gambhir SS. A model-based personalized cancer screening strategy for detecting early-stage tumors using blood-borne biomarkers. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2570–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lahouel K, Younes L, Danilova L, Giardiello FM, Hruban RH, Groopman J, et al. Revisiting the tumorigenesis timeline with a data-driven generative model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:857–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914589117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mitchell TJ, Turajlic S, Rowan A, Nicol D, Farmery JH, O’Brien T, et al. Timing the landmark events in the evolution of clear cell renal cell cancer: Tracerx renal. Cell. 2018;173:611–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Inadomi JM, Saxena N. Screening and surveillance for Barrett’s esophagus: Is it cost-effective? Digest Dis Sci. 2018;63:2094–104. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Benaglia T, Sharples LD, Fitzgerald RC, Lyratzopoulos G. Health benefits and cost effectiveness of endoscopic and nonendoscopic cytosponge screening for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:62–73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Qumseya BJ, Bukannan A, Gendy S, Ahemd Y, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointestl Endosc. 2019;90:707–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Rubenstein JH, Morgenstern H, Appelman H, Scheiman J, Schoenfeld P, McMahon LF, Jr, et al. Prediction of Barrett’s esophagus among men. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:353. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, Cumings MD, Wong RKH, Vasudeva RS, et al. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterol. 2003;125:1670–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson S-E, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterol. 2005;129:1825–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gerson LB, Banerjee S. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:867–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Yu M, Hazelton WD, Luebeck EG, Grady WM. Epigenetic aging: more than just a clock when it comes to cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;80:367–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Chen G, Liu Y, Shen D, K MR. Composite large margin classifiers with latent subclasses for heterogeneous biomedical data. Stat Anal Data Min. 2016;9:75–88. doi: 10.1002/sam.11300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All analytical distributions to recreate our Results (data in Supplementary Table S1) and apply to other data are available in the Text and Supplementary Data. Code to solve equations was developed in R (version 3.6.1) and is publicly available at: github.com/yosoykit/OptimalTimingScreening. CORI data can be accessed through application with ethical approval to NIDDK: https://niddkrepository.org/studies/cori/.