Abstract

Smoking rates in people with depression and anxiety are twice as high as in the general population, even though people with depression and anxiety are motivated to stop smoking. Most healthcare professionals are aware that stopping smoking is one of the greatest changes that people can make to improve their health. However, smoking cessation can be a difficult topic to raise. Evidence suggests that smoking may cause some mental health problems, and that the tobacco withdrawal cycle partly contributes to worse mental health. By stopping smoking, a person’s mental health may improve, and the size of this improvement might be equal to taking anti-depressants. In this theoretical review and practical guide we outline ways in which healthcare professionals can raise the topic of smoking compassionately and respectfully to encourage smoking cessation. We draw on evidence-based methods like cognitive behavioural therapy, and outline approaches that healthcare professionals can use to integrate these methods into routine care.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, anxiety, depression, cognitive behavioural therapy, theoretical review, practical guide

Introduction

Smoking tobacco is the world’s leading cause of preventable illness and death (World Health Organisation, 2011). One in every two smokers will die of a smoking-related disease, unless they stop smoking (Doll et al., 2004; Pirie et al., 2013). In the United Kingdom smoking prevalence has decreased from 46% during the 1970s to about 15% in recent years (West and Brown, 2019). However, in the UK approximately 34% of people with depression and 29% of people with anxiety, smoke tobacco (Taylor, Itani, et al., 2019). People with depression and anxiety are more heavily addicted, suffer from worse withdrawal (Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2013), and find it harder to quit (odds ratio 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.67 to 0.97) (Hitsman et al., 2013). These inequalities at least partly contribute to a reduction in life-expectancy in people with mood disorders when compared to the general population (mortality rate ratio, 1.92 (95% CI 1.91 to 1.94) (Plana-Ripoll et al., 2019).

Most healthcare professionals are aware that stopping smoking is one of the greatest changes that people can make to improve their health. However, smoking cessation can be a difficult topic to raise. Many people say that smoking tobacco helps them to alleviate stress, cope with their mental health difficulties, like low mood or anxiety and that smoking brings them relaxation or pleasure (Malone, Harrison and Daker-White, 2018). When discussing smoking cessation, it can sometimes feel like we might be depriving people of one of their ‘biggest pleasures’. It can also feel like we might undermine our relationship with them, and their trust in us, which could compromise future consultations and treatment plans.

Traditionally, tobacco addiction and mental health have been treated separately, usually focusing on mental health first (Baker et al., 2019). Research shows that people with mental health problems are as motivated to quit as the general population, with more than half contemplating quitting within 6 months, or preparing to quit within 30 days (Richardson, McNeill and Brose, 2019). However, we know that for many people, mental health conditions can be recurring over the longer term. So, when is ‘the right time’ to quit smoking? People with mood disorders are most likely to die from smoking-related diseases (Plana-Ripoll et al., 2019). How best can we address smoking cessation when their main presenting concern is their mental health?

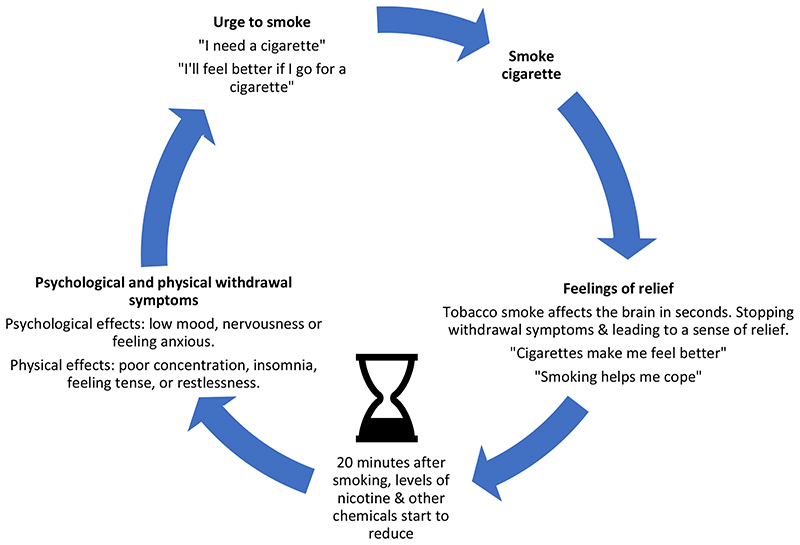

It is not yet widely known that smoking tobacco might actually cause mental health problems (Taylor and Munafò, 2018), and that stopping smoking may improve mental health (Taylor et al., 2014, 2020). In fact, the size of improvement in mental health observed when people stop smoking is similar to the size of effect observed when people take anti-depressants (Taylor et al., 2014). This improvement can be at least partly explained by breaking the tobacco withdrawal cycle. Tobacco addiction leads to periods of withdrawal shortly after having a cigarette, whereby the person who smokes experiences psychological symptoms such as low mood, anxiety, poor concentration and irritability (Benowitz, 2010). If the person smokes on a regular basis they will feel these withdrawal symptoms much of the time, with short periods of relief only when they smoke, and shortly after.

As healthcare professionals there are ways that we can compassionately approach smoking cessation and remain respectful of the person’s autonomy. It’s important that we share new research findings, reassuring patients that stopping smoking will not have a negative impact on their overall mental health and could actually improve it in the long term. This knowledge could empower and motivate smoking cessation. Smoking cessation treatments are effective in this population (Taylor, Itani, et al., 2019). However, as people with common mental health problems often experience higher levels of tobacco dependence, they can require higher doses over longer periods of time of some medicines, like NRT (NCSCT, 2019), and tailored behavioural support during their quit attempt (National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2013), specifically targeting mood (van der Meer et al., 2013).

Learning objectives

Although the focus of this article is primarily on those with common mental health problems, this article may also be useful to guide consulting with patients who report stress, and other common mood disturbances. After reading this article you will be able to:

Use principles from cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) to help your clients with common mental health problems to understand how their tobacco dependence and mental health are linked;

Understand how the tobacco withdrawal cycle, conditioned craving, and possible increases in side-effects of prescribed medications upon cessation can all mimic common mental health symptoms, like anxiety, depression, low mood or stress; and

Understand how breaking the tobacco withdrawal cycle, better coping with cravings, and developing greater self-control can all improve mental health.

Understanding Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Principles

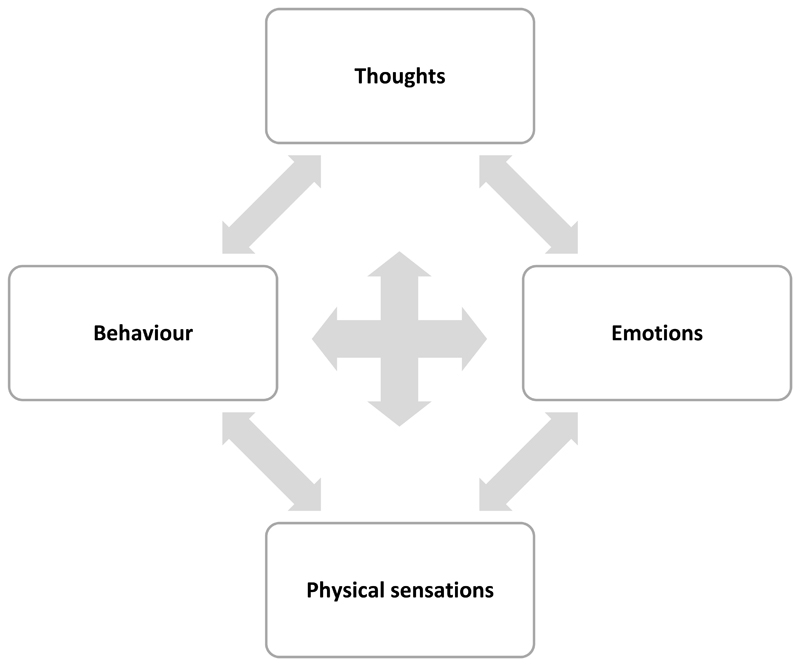

The basic principles of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) are a helpful way to support clients to see how their thoughts, emotions, behaviour and physical sensations are interlinked (Figure 1). CBT is usually used to treat mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, low mood and stress, but can also be used to treat smoking and alcohol and other drug problems. Recently, a dual process theory of addiction has been proposed, whereby addictive behaviour is the result of the predominance of implicit, automatic, and mainly nonconscious cognitive processes over explicit, controlled, and mainly conscious processes (Heather and Segal, 2016). CBT helps people focus in on their present challenges and how these are linked with their thoughts, emotions, behaviour and physical sensations. Using this model can help people to recognise, assess and respond to their problems, by establishing greater behavioural and cognitive control over impulsive urges and preventing relapse (Heather and Segal, 2016).

Figure 1. Tobacco addiction maintenance cycle.

How do I Link Mood and Other Experiences of Mental Health Symptoms and Smoking Using a CBT Model?

Using a CBT model is a helpful way of supporting people to see how their thoughts, emotions, behaviour and physical sensations are interlinked in the context of their tobacco dependence and mental health (Figure 1). To promote smoking cessation for people with depression or anxiety, self-monitoring of mental health symptoms and medication side-effects increases understanding about their links. Monitoring that starts pre-cessation and continues for a few weeks post-cessation may help to distinguish temporary nicotine withdrawal symptoms from a relapse of mental illness and, for those taking medication, can track common adverse side effects that can increase with quitting (Segan et al., 2017). Of course, monitoring can also help to address symptoms regardless of their cause.

The monitoring tool used by Quitline Victoria (See Segan et al. (2017)) includes structured monitoring of: (i) nicotine withdrawal symptoms using the 8-item Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (Hughes, 2007b) to examine: anger/irritability/frustration, anxiety or nervousness, depression/sad mood, desire/craving to smoke, difficulty concentrating, increased appetite/hunger/weight gain, insomnia/sleep problems/awakening at night, and restlessness/impatience, and (ii) the most common adverse side effects of psychiatric medications, i.e., dry mouth, increased thirst, drowsiness, tiredness, fatigue, increased sleep, blurred vision, dizziness, headache, increased sweating, increased salivation, and nausea (Lapshin, Skinner and Finkelstein, 2006). When administered, the scale is referred to as a “mood and experiences scale” because smokers might be confused by completing a “withdrawal” scale prior to cessation and sometimes post-cessation will not report a symptom if they do not believe that it is due to withdrawal. Use of the term “symptom” was avoided as it is very clinical and can imply that something is wrong and needs fixing; hence the phrase “moods and experiences” and “possible side effects.” There is of course some overlap between some nicotine withdrawal symptoms (anxiety, depression, increased appetite/weight gain, insomnia) and common medication side effects.

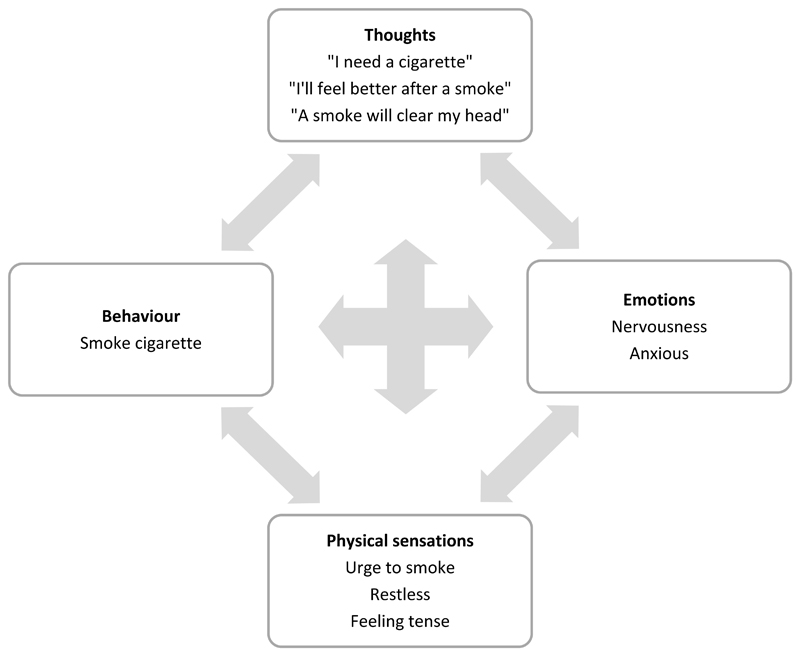

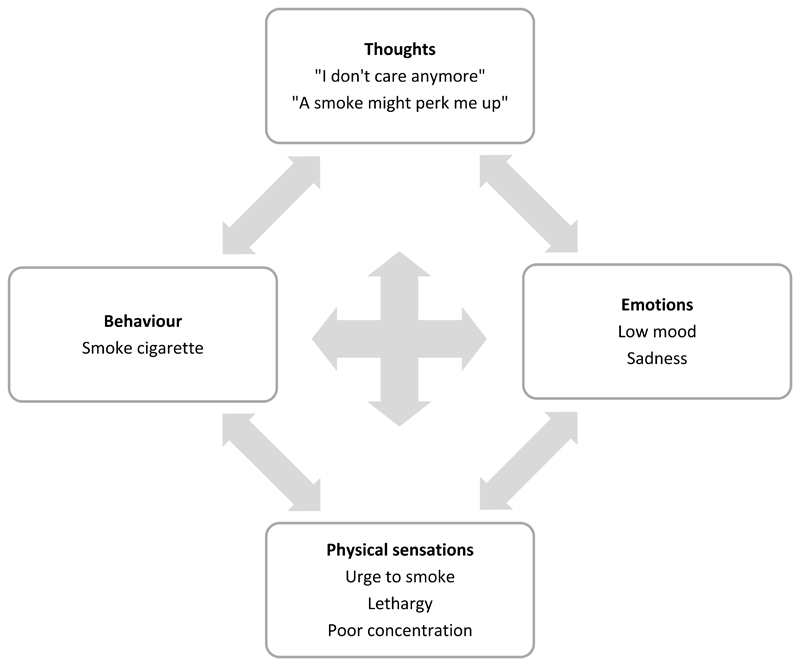

In the case of anxiety, depression, low mood and stress, the five areas of the model can help us understand that these conditions and their associated feelings can be a trigger for smoking (Figures 2 and 3). Smoking may be an effort to calm themselves down, reduce anxiety, make themselves feel relaxed, give themselves a break, or to self-medicate. As smoking provides short term relief from withdrawal, and as the person thinks they feel better after a cigarette, this reinforces their smoking behaviour. However, as little as 20 minutes later this cycle will happen again generating further feelings of anxiety, sadness or hopelessness, etc. Figures 2 and 3 show how these areas interact with one another to maintain an unhelpful coping behaviour, or maintain a pattern of low mood. You can watch this animation available here summarising this approach https://youtu.be/HiYBGOQ-PIo.

Figure 1. Cognitive behavioural model.

Figure 1. Anxiety cycle: Trigger - anxiety provoking event.

In this model you can see how thoughts, emotions, physical sensations, and behaviour are all interlinked.

Showing your client this animation might be a useful tool when explaining links between tobacco use and depression/anxiety symptoms https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQn4MbWbiSU.

How can I Integrate CBT Principles for Smoking and Mental Health into Routine Care?

These CBT principles are designed to be used as a tool, not as a sole treatment, and are best used as part of a NICE recommended smoking cessation treatment, ideally behavioural support in combination with pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation (National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2018). Depending on time available and circumstances, behavioural support may range from very brief advice or behavioural support, or involve developing a collaborative model or ‘formulation’ of the person’s smoking and a plan for cognitive and behavioural change involving such approaches as behavioural activation, mindfulness, coping with cravings and relapse prevention. Pharmacotherapy choice will depend on previous experience, preference, and whether or not the person will also consult a medical practitioner for a prescription. Pharmacotherapy may involve NRT (usually a combination of patch and one or more short-acting forms such as gum, lozenge, spray or vaporizer), varenicline, or bupropion (depending on country). Smokers may also want to try e-cigarettes as a nicotine replacement product, which is supported by Public Health England (McNeill et al., 2018). Adherence to medications is important and this can be monitored along with mood and experiences to enhance discussion of how medication assists in alleviation of withdrawal discomfort.

Very brief advice for smoking cessation

The National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training’s (NCSCT) “very brief advice” approach is being increasingly used. A systematic review and meta-analysis of brief opportunistic interventions for smoking cessation found that healthcare professionals can be more effective in promoting attempts to stop smoking by offering help to all smokers, rather than by offering assistance only to those who state that they want to stop smoking (Aveyard et al., 2012). Brief interventions in settings like primary care, can be very effective to improve lifestyle behaviours (Aveyard et al., 2016).

Very brief advice (the 3 A’s) involves:

ASK - establish smoking status. “Do you smoke tobacco cigarettes or roll-ups?”

ADVISE - that the best way of stopping smoking is to use a combination of behavioural support and drug treatment. “Did you know that smoking cessation medicine plus smoking cessation counselling can double your chances of quitting?”

ASSIST - provide a referral or offer behavioural support using the CBT model as a tool, and follow-up appointments. “Would you like to meet again to talk about smoking cessation options?”, “I can refer you to a smoking cessation specialist, if you like?”

Smokers may say to you that they are “too stressed out to stop”, that they would like to “deal with their mental health problem before they stop smoking”, or that they “won’t be able to cope without cigarettes”. This may be an ideal opportunity to implement the CBT principles for smoking and mental health (Figures 2 and 3) to explore their mental health and tobacco dependence. This might encourage them to think about stopping smoking or even prompt a quit attempt.

Standard behavioural support for smoking cessation

If you are regularly consulting with the person, or are involved in offering behavioural support to change lifestyle behaviours, or are involved in the provision of behavioural support for smoking cessation, the CBT principles for smoking and mental health discussed here can be integrated into the standard smoking cessation treatment programme designed by the NCSCT (NCSCT, 2019). For example, the NCSCT recommends that standard behavioural support for smoking cessation involves of 110 minutes of behavioural support over 6 sessions. Within each of these sessions, there are opportunities to provide support around any concerns the person is having about quitting smoking and their mental health, psychoeducational opportunities about the withdrawal cycle and mental health, and the mental health benefits of smoking cessation.

In the ESCAPE trial (Taylor, Aveyard, et al., 2019), psychological wellbeing practitioners are integrating smoking cessation treatment into psychological services for common mental health problems, using a smoking cessation intervention checklist (Table 1). Using this checklist, they are tailoring the intervention content to the person’s needs. Psychological wellbeing practitioners dedicate time during each session to address the person’s beliefs about smoking and mental health, and tailor intervention components using their knowledge about smoking and mental health, and mental health and tobacco withdrawal.

Table 1. NCSCT standard treatment programme with additional mental health support for smoking cessation (McEwen, 2014; Taylor. Aveyard, et al.. 2019).

| Session | 1 | 2 | 3-5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking cessation treatment session | Pre-quit | Quit day | Followup | Final |

| Task | ||||

| Address client beliefs about smoking and mental health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Inform client about the treatment programme | ✓ | |||

| Assess current smoking | ✓ | |||

| Assess past quit attempts | ✓ | |||

| Explain how smoking dependence develops and assess nicotine dependence | ✓ | |||

| Explain the importance of abrupt cessation and the ‘not a puff’ rule | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Inform the client about withdrawal symptoms | ✓ | |||

| Discuss stop smoking medications/products | ✓ | |||

| Set the quit date | ✓ | |||

| Prompt a commitment from the client | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Check on client progress | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Confirm client readiness and ability to quit | ✓ | |||

| Confirm that the client has a sufficient supply of stop smoking medication/products | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Give client NRT vouchers or refer to pharmacy/GP for varenicline | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Enquire about medication use | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Discuss withdrawal symptoms and cravings, and how to cope | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Advise on changing routine | ✓ | |||

| Carbon monoxide (CO)-monitoring | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Discuss how to address the issue of the client’s smoking contacts and how the client can get support during their quit attempt | ✓ | |||

| Discuss any difficult situations experienced and methods of coping | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Address any potential high-risk situations in the coming week | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Discuss plans and provide a summary | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Understanding Links Between the Tobacco Use and Common Mental Health Problems

When someone starts smoking, there are some rewarding effects of tobacco on mood and cognition. Social reasons, such as feelings of belonging, can also be important. Smoking is also used as an appetite suppressant. However, as the person becomes used to the effects of tobacco, these reasons for smoking tend to diminish as the alleviation of withdrawal symptoms like low mood, irritability, poor concentration, restlessness and anxiety (Benowitz, 2010) gain prominence. Nevertheless, the initial rewarding effects of smoking tend to remain important in the minds of smokers and it is these rewards that can tempt them back to smoking, even long after cessation has been achieved (Stevenson et al., 2017).

Regular smoking causes neuroadaptations in nicotinic pathways in the brain. Neuroadaptations in these pathways are associated with occurrence of depressed mood, agitation and anxiety shortly after a cigarette is smoked (Benowitz, Hukkanen and Jacob, 2009). This withdrawal cycle is marked by fluctuations in a smoker’s psychological state throughout the day and can worsen mental health (Parrott, 2004). There is evidence some systems that are compromised during longer term tobacco exposure recover after smoking cessation (Mamede et al., 2007).

People who smoke regularly will feel these withdrawal symptoms much of the time, with short periods of relief only when they smoke, and shortly after (Figure 4). When caught in this cycle, people can mistakenly believe that smoking helps relieve symptoms of anxiety or low mood (Parrott, 2004). But this isn’t the case – these symptoms are caused by tobacco withdrawal. Stopping smoking will eventually alleviate these symptoms altogether. Improvements in these symptoms, usually start several weeks after stopping smoking, and then the cycle is broken (Hughes, 2007a; Taylor et al., 2014). Lapses to smoking can be associating with recalling the initial pleasures associated with smoking or beliefs around dealing with stress. Lapses can be seen as learning opportunities towards eventual cessation.

Figure 1. Depression cycle: Trigger - feeling depressed at home in the evening.

Tobacco use is a vicious cycle that can negatively affect mental health. It’s useful to explain this cycle to smokers with mental health problems. From here, you can then help them understand how their smoking and mental health are linked. This information can be formulated as part of their presentation and a clear understanding can be sought about how smoking can become a maintenance factor in their mental health difficulties. Figure 4 shows that 20 minutes after smoking a cigarette, levels of nicotine and other chemicals start to reduce (Benowitz, Hukkanen and Jacob, 2009). This leads to physical and psychological tobacco withdrawal with symptoms such as – poor concentration, insomnia, feelings of tension, restlessness, low mood and anxiety. You can see how most of these symptoms might be mis-attributed as mental health symptoms.

Can Smokers Cope Without Tobacco?

There are many reasons why people report smoking tobacco. People with mental health problems usually report smoking cigarettes to alleviate emotional problems and feelings of depression and anxiety, to stabilise mood, for relaxation and stress-relief (Malone, Harrison and Daker-White, 2018).

Studies have followed people making a quit attempt and show that when they stop smoking their mental health improves and, conversely, when they relapse, their mental health worsens to where it was before (Taylor et al., 2014). Similarly, there is good evidence that taking up smoking early in adolescence is associated with developing depression and anxiety (Wu and Anthony, 1999; Jamal et al., 2011, 2012).

Smoking cessation can increase the blood levels and hence side effects of some psychotropic medications as well as alcohol and caffeine (Segan et al., 2017). This is because the tar in cigarette smoke (not the nicotine) causes the body to break down some substances more quickly than usual. Nicotine and nicotine replacement therapies do not affect medication, caffeine, or alcohol levels in this way. Monitoring these side-effects with the person quitting smoking can be helpful and we describe how to do so below.

Will Stopping Smoking Harm Mental Health?

Stopping smoking will not harm mental health. Evidence to-date suggests that there may be a causal effect of smoking on mental health, such that starting smoking increases risk of depression and schizophrenia (Taylor and Munafò, 2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 longitudinal studies found that stopping smoking was also associated with long-term improvements in mental health similar in effect size to taking anti-depressants, and the benefit was at least as large in people with psychiatric conditions (Taylor et al., 2014). Another study found no consistent evidence that varenicline, an effective medicine for smoking cessation, was associated with greater odds of depression, neurotic disorder, antidepressant, or hypnotic/anxiolytic prescription in clients with or without mental health disorders (Taylor, Itani, et al., 2019). In general, this study found that varenicline was associated with improved mental health outcomes, such as reductions in anti-depressant and anxiolytic prescriptions up to 2 years after taking medicine to stop smoking (Taylor, Itani, et al., 2019).

What About Patients with Comorbid Mental Health, Tobacco Dependence and Comorbid Substance/Alcohol Use?

In people with comorbid substance and/or alcohol use, smoking rates are more than double compared to people with similar demographic characteristics (Guydish et al., 2016). Importantly, many people who use substances and/or alcohol, and who smoke tobacco are motivated to quit smoking tobacco, but report lack of support (Gentry et al., 2017).

Some studies show that cannabis co-use is associated with worse tobacco smoking cessation outcomes, compared with tobacco-only users (Abrantes et al., 2009; Schauer, King and McAfee, 2017; Vogel et al., 2018; Weinberger et al., 2018; McClure et al., 2019). However, other studies show that cannabis use is not associated with tobacco cessation outcomes (Humfleet et al., 1999; Hendricks et al., 2012; Rabin et al., 2016). Similarly for alcohol, co-use is associated with worse smoking cessation outcomes compared with tobacco-only users (Humfleet et al., 1999; Van Zundert, Kuntsche and Engels, 2012; Haug, Schaub and Schmid, 2014; Haug et al., 2017; Weinberger, Gbedemah and Goodwin, 2017); alcohol use is also associated with increased tobacco cravings, and vice-versa (Cooney et al., 2007; Verplaetse and McKee, 2017). Patients with alcohol or opioid dependence report several barriers to quitting smoking tobacco including anxiety, tension/irritability, and concerns about the ability to maintain abstinence from their primary substance of abuse (McHugh et al., 2017). Those who report more barriers to smoking cessation while using substances/alcohol report lower confidence in the ability to change their tobacco smoking behaviour (McHugh et al., 2017).

Historically, substance/alcohol use and tobacco dependence are treated separately. However, more recently, there has been a movement towards interventions that target multi-morbidity, including dual tobacco and substance/alcohol use, and in people with common mental disorders (Kay-Lambkin et al., 2013; Baker, A, Kavanagh, D, Kay-Lambkin, F, Hunt, S, Lewin, T, Carr VJ, 2014; Apollonio, Philipps and Bero, 2016). A Cochrane review of interventions for tobacco use cessation in people in treatment for or recovery from substance use found that offering pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation increased tobacco abstinence (risk ratio (RR) 1.88, 95%CI 1.35 to 2.57), as did combined counselling and offering pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation (RR 1.74,95% CI 1.39 to 2.18) compared with usual care or no intervention. The review found that tobacco cessation interventions were associated with smoking cessation for people in substance use treatment (RR 1.99, 95% CI 1.59 to 2.50) and people in recovery (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.67), and for people with alcohol dependence (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.81) and people with other drug dependencies (RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.43 to 2.40). Importantly there was no evidence that offering tobacco cessation interventions to people in drug dependence treatment or recovery impacted on abstinence from alcohol and other drugs (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.03).

How do I Discuss Smoking Without Seeming Didactic?

Smoking cessation can be a sensitive topic. Linking the person’s smoking to their mental health issues and personal values can help to break down the barriers to discussion (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). It’s important not to prematurely focus on smoking. Actively listen to the person’s main concerns (e.g., such as feelings of depression). Introduce smoking by asking open-ended questions about any possible links between smoking and their main concern (e.g., mood), “What links have you noticed between smoking and your moods?” Seek permission to provide information about these links (e.g., “I wonder if you’d be interested in hearing about recent research findings about how smoking effects mental health?”). Healthcare providers can also spend a few moments debunking the myths about smoking: “A lot of people think that smoking is a stress reliever, but most people when they stop feel less stressed. Research shows their mental health permanently improves”. After providing them with information (as outlined further in this guide), ask “What do you make of that?” Explore with them their concerns about how smoking may be influencing their own mental health. Most people have other concerns about smoking, so ask them, “What other concerns do you have? What concerns you the most?” You can start to move the person towards consideration of cessation by asking “What’s the next step?”.

When people are not contemplating quitting in the foreseeable future, it can be worthwhile to open the conversation up, acknowledging the pleasures initially experienced in the early days of smoking, “Tell me some of the reasons you smoke”. Often people will reply that although they did once enjoy being seen as ‘cool’ or part of the social crowd smoking whilst out drinking, they are likely to admit that such pleasures have been long outweighed by concerns such as addiction and cost. Reflect back on these concerns. If no concerns are mentioned, ask “Tell me what reasons you might have to want to quit?” Here, the person’s values may be raised, for example, many people talk about wanting to be good parents, to be around to see their children grow up and want to be available for family members. Normalising the person’s feelings can help, for example, “That’s a common concern”. It’s important to encourage the person and boost their confidence in their ability to quit, “Did you know that you can double your chances of quitting with help from our local stop smoking services?” Health professionals can also spend a few moments debunking the myths about smoking, asking, “Can I tell you a few things about smoking that might surprise you and help you to quit?”, “I wonder, did you know that quitting smoking can improve your overall mental health?”, “Many people think it’s the nicotine in cigarettes that’s harmful, however, It’s the components in the tobacco smoke that are the most harmful”.

Conclusion

Most healthcare professionals are aware that stopping smoking is one of the greatest changes that people can make to improve their health. However, smoking cessation can be a difficult topic to raise, especially when a person’s main reason for consulting is their mental health, or another health concern. Evidence suggests that smoking may cause some mental health problems, and that the tobacco withdrawal cycle partly contributes to worse mental health. By stopping smoking, a person’s mental health may improve, and the size of this improvement might be equal to taking anti-depressants. By drawing on evidence-based methods such as behavioural support and CBT healthcare professionals can address smoking cessation in a compassionate and respectful manner and successfully integrate smoking cessation treatment into routine care.

Who is this Theoretical Review and Guide for?

This guide is for healthcare professionals who are involved in routine healthcare for people who have common mental health problems like anxiety, depression, low mood or stress, and who smoke tobacco.

You could be a nurse, a psychological wellbeing practitioner, a psychiatrist, a GP, a therapist, or clinical psychologist, working in any healthcare setting where you have an opportunity to offer a brief or intensive behavioural intervention to encourage or support smoking cessation.

You do not need to be an expert in tobacco addiction to use, read or apply this review and guide.

Multiple Choice Questions

- The best way to support smoking cessation for people with common mental health problems is:

-

a)To recommend that they try to quit once their mental health improves

-

b)To recommend combination smoking cessation medicine, and behavioural support for smoking cessation

-

c)Suggest that they use will power and nicotine replacement therapy

-

d)Suggest that they go to their pharmacy for over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy

-

e)Not to recommend smoking cessation as smoking tobacco offers stress relief

-

a)

- What do the 3 A’s stand for:

-

a)Ask, Advise, Assist

-

b)Avoid, Advise, Assist

-

c)Argue, Advise, Assist

-

d)Ask, Assess, Assist

-

e)Aid, Assess, Advise

-

a)

- How soon after smoking a cigarette do tobacco withdrawal symptoms start:

-

a)1 hour

-

b)24 hours

-

c)20 minutes

-

d)2-3 hours

-

e)12 hours

-

a)

- Generally, quitting smoking is associated with:

-

a)Worse mental health recovery

-

b)Inability to cope with mental health symptoms

-

c)Long term improvements in common mental health symptoms

-

d)Needing a higher dose of anti-depressants

-

e)None of the above

-

a)

- Smoking is a risk factor in the development of:

-

a)Cancers, and heart disease

-

b)Depression

-

c)Schizophrenia

-

d)Poor quality of life

-

e)All of the above

-

a)

Answers

- The best way to support smoking cessation for people with common mental health problems is:

-

a)F

-

b)T

-

c)F

-

d)F

-

e)F

-

a)

- What do the 3 A’s stand for:

-

a)T

-

b)F

-

c)F

-

d)F

-

e)F

-

a)

- How soon after smoking a cigarette do tobacco withdrawal symptoms start:

-

a)F

-

b)F

-

c)T

-

d)F

-

e)F

-

a)

- Generally, quitting smoking is associated with:

-

a)F

-

b)F

-

c)T

-

d)F

-

e)F

-

a)

- Smoking is a risk factor in the development of:

-

a)F

-

b)F

-

c)F

-

d)F

-

e)T

-

a)

Funding

GT is funded by Cancer Research UK Population Researcher Postdoctoral Fellowship award (C56067/A21330). Amanda Baker is funded by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (G1601524). PA is an NIHR senior investigator and is funded by NIHR Oxford’s Biomedical Research Centre and Applied Research Centre. MRM is a programme lead in the MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) at the University of Bristol (MC_UU_00011/7).

Corresponding Author Biography

Dr Taylor is an Assistant Professor in Clinical Psychology, and Research Director for The Addiction and Mental Health Group (AIM) in the Department of Psychology at The University of Bath. Her work has had international impact in the field of smoking and mental health. She currently holds a post-doctoral fellowship award from Cancer Research UK, which focuses on designing a smoking cessation intervention for people with depression/anxiety and testing the intervention in mental health settings (Improving Access to Psychological Services (IAPT)).

Dr Taylor is an epidemiologist and behavioural scientist. She completed her PhD in epidemiology at The University of Birmingham on the topic of smoking and mental health. Her work falls within the remits of clinical and health psychology, and public health, with a strong focus on applied research. She uses epidemiological methods to find and explore intervention targets, and then interpret the results using behavioural and psychological theory for use in mental health and addiction treatment settings.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

Dr Gemma Taylor and Professor Marcus Munafò have previously received funding from Pfizer, who manufacture smoking cessation products. Professor Paul Aveyard led a trial funded by the NIHR and Glaxo Smith Kline donated nicotine patches to the NHS in support of the trial. Professor Amanda Baker led trials funded by the NHMRC and Glaxo Smith Kline donated nicotine replacement therapy in support of the trials.

References

- Abrantes AM, et al. Health risk behaviors in relation to making a smoking quit attempt among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9184-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apollonio D, Philipps R, Bero L. Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people in treatment for or recovery from substance use disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010274.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard P, et al. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107(6):1066–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard P, et al. Lancet (London, England) 10059. Vol. 388. Elsevier; 2016. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial; pp. 2492–2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A, Kavanagh D, Kay-Lambkin F, Hunt S, Lewin T, Carr VJ, M P. Randomized controlled trial of MICBT for co-existing alcohol misuse and depression: Outcomes to 36-months. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2014;46(3):281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AL, et al. In: A Clinical Introduction to Psychosis Foundations for Clinical Psychologists and Neuropsychologists. Badcock J, Paulik G, editors. Academic Press; 2019. Treating comorbid substance use and psychosis; pp. 511–536. [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz N. Nicotine Addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1038/333287d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P. Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney NL, et al. Alcohol and Tobacco Cessation in Alcohol-Dependent Smokers: Analysis of Real-Time Reports. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007 doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry S, et al. Smoking cessation for substance misusers: A systematic review of qualitative studies on participant and provider beliefs and perceptions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, et al. Addiction. 2. Vol. 111. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2016. An international systematic review of smoking prevalence in addiction treatment; pp. 220–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug S, et al. Efficacy of a technology-based, integrated smoking cessation and alcohol intervention for smoking cessation in adolescents: Results of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug S, Schaub MP, Schmid H. Predictors of adolescent smoking cessation and smoking reduction. Patient Education and Counseling. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Segal G. Addiction and Choice: Rethinking the relationship. Oxford University Press; 2016. Chapter 25: Overview of addiction as a disorder of choice and future prospects; pp. 463–482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, et al. Alcohol and marijuana use in the context of tobacco dependence treatment: Impact on outcome and mediation of effect. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitsman B, et al. Past major depression and smoking cessation outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction. 2013;108(2):294–306. doi: 10.1111/add.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: Valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007a doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Measurement of the Effects of Abstinence from Tobacco: A Qualitative Review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007b;21(2):127–137. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humfleet G, et al. History of alcohol or drug problems, current use of alcohol or marijuana, and success in quitting smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 1999 doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal M, et al. Age at smoking onset and the onset of depression and anxiety disorders. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal M, et al. Association of smoking and nicotine dependence with severity and course of symptoms in patients with depressive or anxiety disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay-Lambkin F, et al. The Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Treatment for Comorbid Depression and Alcohol Misuse. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11469-013-9437-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapshin O, Skinner CJ, Finkelstein J. How do psychiatric patients perceive the side effects of their medications? German Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;9(3):74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Malone V, Harrison R, Daker-White G. Mental health service user and staff perspectives on tobacco addiction and smoking cessation: A meta-synthesis of published qualitative studies. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2018;25(4):270–282. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamede M, et al. Temporal Change in Human Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor After Smoking Cessation: 5IA SPECT Study. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, et al. Cannabis and Alcohol Co-Use in a Smoking Cessation Pharmacotherapy Trial for Adolescents and Emerging Adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2019 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, et al. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. Vol. 74. Elsevier Inc.; 2017. Perceived barriers to smoking cessation among adults with substance use disorders; pp. 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A, et al. Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018. A report commissioned by Public Health England. London, UK: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- van derMeer RM, et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013. Smoking cessation interventions for smokers with current or past depression. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) [Accessed: 17 July 2019];Smoking: acute, maternity and mental health services PH48. 2013 Available at: http://nice.org.uk/guidance/ph48.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) Stop smoking interventions and services NICE guideline [NG92] NICE; 2018. [Accessed: 3 October 2018]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng92/chapter/recommendations#stop-smoking-support. [Google Scholar]

- NCSCT. Standard treatment programme: a guide to behavioural support for smoking cessation. London, UK, UK: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Heightened stress and depression follow cigarette smoking. Psychological Reports. 2004;94(1):33–34. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.1.33-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirie K, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. The lancet. 2013;381(9861):133–141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plana-Ripoll O, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. The Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827–1835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin RA, et al. Does cannabis use moderate smoking cessation outcomes in treatment-seeking tobacco smokers? Analysis from a large multi-center trial. American Journal on Addictions. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ajad.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S, McNeill A, Brose LS. Addictive Behaviors. Vol. 90. Elsevier Ltd; 2019. Smoking and quitting behaviours by mental health conditions in Great Britain (1993–2014) pp. 14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists. Smoking and Mental Health. London, UK, UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, King BA, McAfee TA. Prevalence, correlates, and trends in tobacco use and cessation among current, former, and never adult marijuana users with a history of tobacco use, 2005-2014. Addictive Behaviors. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segan CJ, et al. Nicotine Withdrawal, Relapse of Mental Illness, or Medication Side-Effect? Implementing a Monitoring Tool for People With Mental Illness Into Quitline Counseling. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2017 doi: 10.1080/15504263.2016.1276657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson JG, et al. Addictive Behaviors. Vol. 67. Elsevier Ltd; 2017. Smoking environment cues reduce ability to resist smoking as measured by a delay to smoking task; pp. 49–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GMJ, et al. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GMJ, Aveyard P, et al. intEgrating Smoking Cessation treatment As part of usual Psychological care for dEpression and anxiety (ESCAPE): protocol for a randomised and controlled, multicentre, acceptability, feasibility and implementation trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0385-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GMJ, Itani T, et al. Prescribing Prevalence, Effectiveness, and Mental Health Safety of Smoking Cessation Medicines in Patients With Mental Disorders. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2019 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GMJ, et al. Smoking cessation for improving mental health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020:CD013522. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GMJ, Munafò MR. The lancet Psychiatry. Elsevier; 2018. Does smoking cause poor mental health? 0(0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse TL, McKee SA. An overview of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in the human laboratory. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2017 doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1189927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EA, et al. Associations between marijuana use and tobacco cessation outcomes in young adults. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, et al. Is cannabis use associated with increased risk of cigarette smoking initiation, persistence, and relapse? longitudinal data from a representative sample of US adults. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Goodwin RD. Cigarette smoking quit rates among adults with and without alcohol use disorders and heavy alcohol use, 2002-2015: A representative sample of the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Brown J. Latest trends on smoking in England from the Smoking Toolkit Study. London, UK, UK: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic: Warning about the Dangers of Tobacco. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Anthony JC. Tobacco smoking and depressed mood in late childhood and early adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 1999 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.12.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanZundert RMP, Kuntsche E, Engels RCME. In the heat of the moment: Alcohol consumption and smoking lapse and relapse among adolescents who have quit smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]