Abstract

The biosynthesis of about one third of the human proteome, including membrane receptors and secreted proteins, occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Conditions that perturb ER homeostasis activate the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). An ‘optimistic’ UPR output aims at restoring homeostasis by reinforcement of machineries that guarantee efficiency and fidelity of protein biogenesis in the ER. Yet, once the UPR ‘deems’ that ER homeostatic readjustment fails, it transitions to a ‘pessimistic’ output, which—depending on the cell-type—will result in apoptosis. In this essay, we discuss emerging concepts on how the UPR ‘evaluates’ ER stress, how the UPR is repurposed, in particular in B cells, and how UPR-driven counter-selection of cells undergoing homeostatic failure serves organismal homeostasis and humoral immunity.

Keywords: B cell development, antibody production, endoplasmic reticulum, proteostasis, unfolded protein response, RIDD

Why ER Stress Evaluation Matters for Humoral Immunity

The vast majority of membrane and secretory proteins, as well as proteins with a destination anywhere along the endomembrane system, are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where they fold and assemble with assistance of ER-resident chaperones and enzymes [1,2]. The ER client proteins are retained in the early secretory pathway until their folding and assembly are completed, whereupon the clients are dispatched to downstream stations along the secretory pathway. Conversely, terminally misfolded proteins or orphan subunits of hetero-oligomers are cleared form the ER, primarily via ER-associated degradation (ERAD), which entails their dislocation to the cytosol for proteasomal destruction [3]. Clearance of non-ERAD-prone misfolded proteins and aggregates may occur either through autophagy [4], or through direct vesicular transfer from ER to lysosomes, in a process called ER-to-lysosome associated degradation (ERLAD) [5]. Despite these clearance mechanisms, the load of client proteins in the ER may still rise to an extent that it overwhelms the ER folding machinery, a condition that is referred to as ER stress. Typically, secretory tissues experience episodic if not persistent ER stress. In addition, pathological conditions may go hand in hand with chronic ER stress also in other tissues. Indeed, various types of genetic disease stem from aberrant ER client proteins that misfold and clog the secretory pathway.

Cells mount the unfolded protein response (UPR) to counteract ER stress and to restore homeostasis [6]. However, when ER homeostatic readjustment fails, the UPR may transition to a pro-apoptotic output [7]. Recent insights from cell models, in which antibody subunits pose a proteostatic insult, point at how the UPR ‘evaluates’ ER stress based on ratiometric stress sensing of the expression levels of ER client proteins versus those of the key ER-resident molecular chaperone Binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) [8,9]. In this essay we argue that, based on the BiP/client ratio, the UPR switches from an ‘optimistic’ to a ‘pessimistic’ signaling output. Central to our concept of ER stress ‘evaluation’ is that once the UPR sensor IRE1α has consumed the finite amount of its preferred substrate XBP1 mRNA, it broadcasts a ‘pessimistic’ signaling output by targeting alternative substrates in a process called regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD) [10]. Since it now has become clear that depending on the cell type, RIDD targets are different [11–15], we posit that the manifestation of the UPR transitioning to a ‘pessimistic’ mode accordingly differs per cell type. This framework sheds new light on how the UPR is purposed and repurposed in various tissues. In particular, we revisit how the UPR appears to be co-opted to warrant efficiency and fidelity of the humoral immune response by (i) counter-selecting against (pre-) B cells that produce aberrant immunoglobulin (Ig) subunits, (ii) preemptively expanding the ER of activated B lymphocytes in anticipation of bulk antibody production, and (iii) fine-tuning the efficiency of secretory antibody production once B cells have become plasma cells. Finally, we extrapolate these insights to the immune response at large.

The UPR Signaling Circuitry

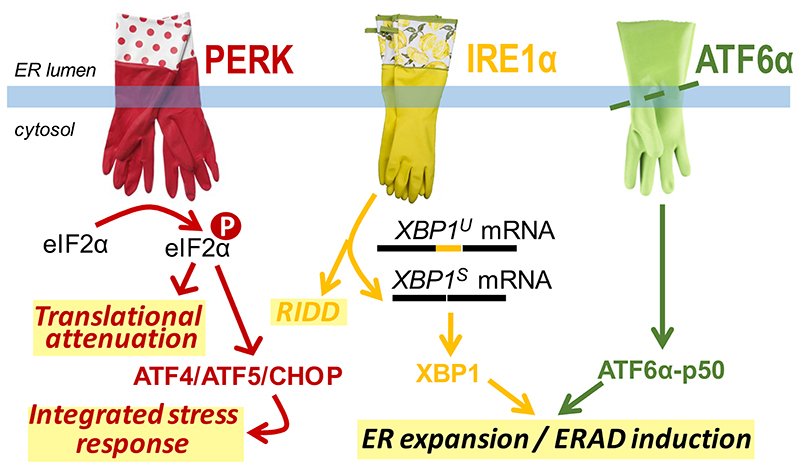

The UPR is the central homeostatic control of ER function (Figure 1), as has been evident since the seminal work in yeast from Kazu Mori, Peter Walter, and co-workers in the early ‘90s [16,17]. In metazoans, the UPR is signaled by at least three main UPR transducers: IRE1α, PERK and ATF6α [6]. Each has a sensing domain in the ER lumen and an effector domain in the cytosol. When ATF6α is activated, it relocalizes to the Golgi apparatus, where regulated intramembrane proteolysis liberates the N-terminal cytosolic portion, ATF6α-p50. The latter localizes to the nucleus where it acts as a transcription factor. The cytosolic effector domains of IRE1α and PERK contain kinase modules that undergo trans-autophosphorylation. Once PERK is activated it mediates phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α, which transiently attenuates overall protein synthesis. Notably, the translation of some targets, including the transcription factors ATF4 and ATF5 is exempted from attenuation. In fact, eIF2α phosphorylation actually favors their expression, and thereby the expression of their downstream effectors, such as the ATF4 target CHOP. Autophosphorylation of the kinase domain of IRE1α activates a second effector domain in its cytosolic portion, which has an endonuclease function. The main target of IRE1α’s endonuclease activity is unspliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1U), which is severed at two positions.

Figure 1. The UPR circuitry.

The UPR in humans is signaled at least via three branches: PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6α. Upon activation by ER stress, PERK mediates the phosphorylation of eIF2α, which leads to translational attenuation. A few transcripts are exempted from translational attenuation, in particular, the expression of the PERK downstream effectors, ATF4 and ATF5 is enhanced when eIF2α is phosphorylated. Targets of ATF4 and ATF5, such as the ATF4 target CHOP, are induced as a consequence. Since next to PERK a few other stress-responsive kinases (PKR, HRI, and GCN2) can drive phosphorylation of eIF2α as well, the effector program downstream of the transcription factors ATF4, ATF5, and CHOP is referred to as the Integrated Stress Response. Upon its activation IRE1α removes an intron from unspliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1U), yielding spliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1S), which encodes the transcription factor XBP1. Next to XBP1 mRNA, IRE1α can target other RNA molecules in a process referred to as RIDD. Upon activation ATF6α is severed in its transmembrane region, releasing its cytosolic domain, ATF6α-p50, which serves as a transcription factor that, like XBP1, drives expression of ER chaperones and ERAD components. As such, the ER protein folding machinery as well as its machinery to dispose of misfolded ER client proteins expands. Thus, the combined efforts of the three UPR branches aim at ER homeostatic readjustment [6].

The two extremities are then religated, such that effectively a small intron is removed, yielding spliced XBP1 mRNA (XBP1S), which encodes the XBP1 transcription factor. However, certain ER stress conditions provoke IRE1α endonuclease activity to commit to RIDD. XBP1 is a target of ATF6α-p50, which provides positive feedback as ATF6α-p50 and XBP1 jointly drive the expression of ER-resident chaperones and enzymes for membrane synthesis, as well as ERAD components. As such, the UPR aims for ER homeostatic readjustment by reinforcing the disposal capacity from and the folding machinery in the ER [6].

A Unified Model for UPR Activation

Activation of UPR pathways has been the central focus of a wealth of studies. In particular, the employment of drugs that rather specifically sabotage productive protein folding in the ER, such as tunicamycin (which disrupts N-glycosylation in the ER), thapsigargin (which depletes Ca2+ from the ER), and dithiothreitol (which counteracts disulfide bond formation in the ER), has been instrumental in mapping the UPR circuitry [6]. Yet, surprisingly little attention has been given to the process of UPR-driven ER homeostatic readjustment, and to what is key for ER homeostatic success. One reason is that the widely-used strategy of employing ER stress-eliciting drugs obscures how ER homeostatic readjustment may be achieved because of the eventual pleiotropic cytotoxicity of these drugs; i.e. the cells die before ER homeostatic readjustment can be achieved.

Recently, a HeLa cell model, in which a proteostatic insult is provoked by inducible over-expression of orphan secretory heavy chain (HC) of IgM (μs), has been employed to circumvent the pleiotropic shortcomings of ER stress-eliciting drugs. The inducible bulk expression of μs causes that ATF6α, IRE1α, and PERK are maximally activated, but the proteostatic insult has no negative impact on cell viability [8]. Hence, the HeLa-μs allows to study the process of ER homeostatic readjustment in detail. As such, it has become clear that the amplitude of UPR signaling does not depend on the extent of misfolded proteins accumulating in the ER per se, but rather on the levels of the ER chaperone BiP being temporarily eclipsed by those of its client μs. Once the levels of BiP outmatch those of μs again, ER homeostatic readjustment is successful, and UPR signaling subsides to submaximal levels [8].

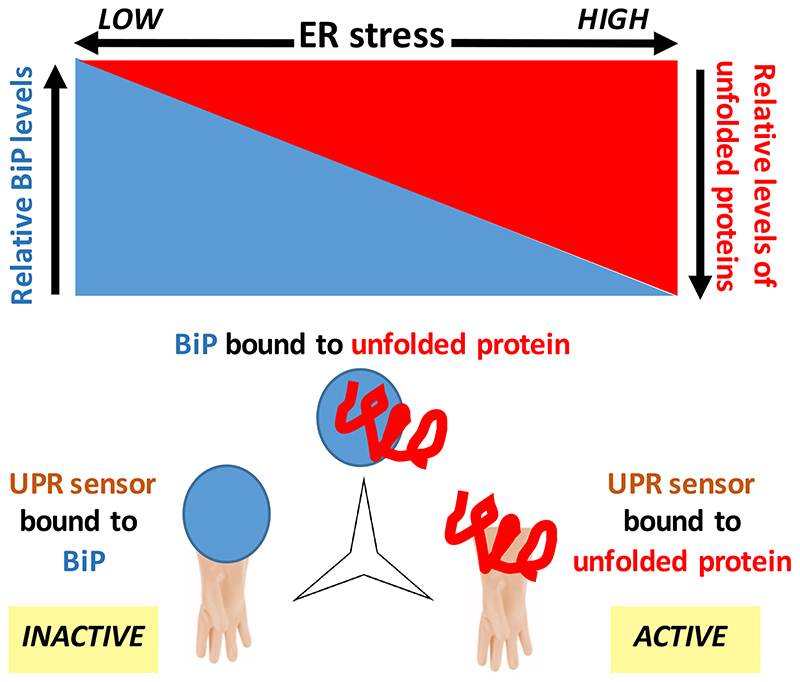

Previously, two models have been proposed for UPR activation. One model entails that dissociation of BiP from the main ER stress sensors, IRE1α, PERK [18] and ATF6α [19] is sufficient for their activation. Non-BiP-sequestering clients, in fact, go undetected by the UPR sensors, as has been shown for μs, lacking the first constant domain (CH1) [9]—HCs, such as μs, indeed interact with BiP exclusively through the CH1 domain [20–22]. In the other model, direct binding of unfolded proteins [23], including the CH1 domain of the HC [24], would be the main mode of activation of these sensors. We argue that these two UPR activation models are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they are complementary and should be unified, since in a three-way competition between UPR sensors, BiP, and an ER client protein (such as μs) for binding one another, the ratio of UPR sensors bound to the client versus those bound to BiP most robustly report on the client/BiP ratio, to which indeed the UPR signaling amplitude correlates [8,9] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A unified model for ratiometric ER stress sensing and UPR activation.

The way the UPR sensors are activated has been highly debated. Since UPR activation coincides with the ER chaperone BiP dissociating from the UPR sensors, it was proposed that titrating BiP away from those sensors by unfolded ER client proteins would be sufficient for UPR activation [18,19]. A contrasting model was put forward when it was shown that unfolded proteins can serve as activating ligands of UPR sensors, namely that the extent of UPR activation would tie in with the extent of unfolded protein associating with the sensors [20]. However, ER stress sensing by the UPR is commensurate with the ratio of unfolded ER client protein levels over BiP [8]. Therefore, the two models are not contradictory, but complementary, since the ratio of UPR sensors bound to unfolded protein over UPR sensors bound to BiP, by essence, would serve as the best readout for the ratio of unfolded protein over BiP. Thus, we posit that the two models can be unified in a single model of ratiometric UPR sensing [8,9].

Do ATF6 Proteins Govern the ‘Generic’ Pathway for ER Homeostasis?

The genetic ablation of all three UPR pathways is tolerated in HeLa cells, but not when they express μs in bulk [8]. ATF6α emerges as the key contributor to setting the programs in motion that lead to ER homeostatic readjustment in HeLa cells, since ablation of both IRE1α and PERK is tolerated in μs-expressing cells, while ablation of ATF6α alone already leads to severe loss of cell growth and apoptosis [9]. Indeed, in the HeLa cells, enhanced expression of ER chaperones, and ER expansion in general, critically depend on ATF6α, but not on IRE1α and/or PERK [9]. Accordingly, it has been proposed that ER homeostatic readjustment in most tissues would rely mainly on the ATF6 proteins, ATF6α and ATF6β [25,26], as the ATF6α/β double KO confers embryonic lethality in mice [26]. In contrast, PERK ablation is not embryonic lethal. PERK KO mice merely suffer from degeneration of tissues with episodic secretory activity, such as the pancreas [27]. Indeed, the PERK-mediated translational block, which is only transient, offers negligible advantage for the response to the sudden but from then on persistent proteostatic insult of μs expression in HeLa cells [8,9].

Different from PERK, it was originally reported that ablation of both IRE1α [28,29] and XBP1 [30] conferred embryonic lethality to mice. Later, however, it turned out that XBP1 KO mice can be rescued by the reintroduction of XBP1 as a transgene even when it is exclusively expressed in the liver [31]. Similarly, IRE1α KO mice survive once IRE1α expression is reconstituted in the placenta [32], and the IRE1α KO mice that are born as a result, suffer from relatively mild aberrations, such as hypoinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and decreased antibody titers [33]. Thus, the PERK and XBP1/IRE1α axes of the UPR emerge as key homeostatic control pathways only within the specific contexts of a few exocrine tissues and cell types, while the ATF6α/β axes may instead serve as the ‘generic’ control pathways for maintaining ER homeostasis in most cell types. Still, PERK, IRE1α and XBP1 are ubiquitously expressed in all tissues (http://www.gtexportal.org). The question is therefore what role(s) the PERK and XBP1/IRE1α axes of the UPR may serve in those tissues that would not rely on them for ‘day-to-day’ ER homeostatic readjustment.

UPR Signaling Upon ER Homeostatic Failure

Not only the UPR but also ERAD is key for HeLa cells to cope with bulk expression of μs, as pharmacological inhibition of ERAD or the ablation of core components of the ERAD machinery causes synthetic lethality upon μs expression [9]. When there is no ERAD, the ever-increasing levels of μs chains in the ER eventually outnumber BiP, even though BiP expression is maximally upregulated. As a consequence of the chronic BiP shortage, ER homeostatic readjustment fails, and IRE1α and PERK chronically signal at maximum amplitude [9]. We reason that such prolonged maximal activation of IRE1α and PERK represents a molecular switch from ‘homeostatic optimism’ (ER homeostasis is ‘deemed’ to be restorable) to ‘homeostatic pessimism’ (ER homeostatic readjustment is doomed to fail). Still, it is important to realize that accumulation of client proteins in the ER is proteotoxic regardless of UPR signaling, since μs-expressing HeLa cells undergo apoptosis even more promptly when all three main UPR branches, IRE1α, ATF6α, and PERK, are ablated [8,9]. Thus, the UPR is not essential for the initiation of pro-apoptotic pathways under irremediable ER stress conditions. Instead, the switch from cyto-protective to pro-apoptotic UPR signaling seems to have arisen in metazoans to preemptively eliminate cells in which restoration of ER homeostasis is unachievable.

UPR-Driven Apoptosis and Beyond

It has been acknowledged, in fact for decades, that unresolved ER stress ties in with PERK- and/or IRE1α-driven cell death [6,7]. However, no consensus has been reached on how or when the UPR transducers would commit to activating pro-apoptotic pathways. We argue that the main obstacle to pinpoint how the UPR transitions to a pro-apoptotic output again has been the wide-spread employment of ER stress-eliciting drugs, which are cytotoxic per se [8], making it a challenge to tease apart specifically UPR-driven pro-apoptotic pathways from other pleiotropically induced pathways that lead to cell death. Moreover, the initiation of pro-apoptotic pathways unlikely represents the only downstream option to give a physiologically meaningful follow-up to a ‘pessimistic’ UPR. Depending on the tissue, dedifferentiation or senescence of the affected cell may favor homeostasis of that tissue better than apoptosis.

The key concept we wish to put forward here is that stress signaling pathways not only must aim for homeostatic readjustment, but also should involve mechanisms through which cells can evaluate whether the attempt at homeostatic readjustment is successful or not. In view of their implication in initiating pro-apoptotic pathways, IRE1α and PERK are the principal candidate ‘evaluators’ of ER homeostatic readjustment being a success or failure. While IRE1α and PERK do contribute to ER homeostatic readjustment, in particular in exocrine tissues, the ‘evaluator’ function may turn out to be the primary task of IRE1α and PERK, in particular in those tissues in which the ATF6 pathways are devoted to executing the lion’s share of ER homeostatic readjustment.

RIDD and the Evaluation of ER Homeostatic Success or Failure

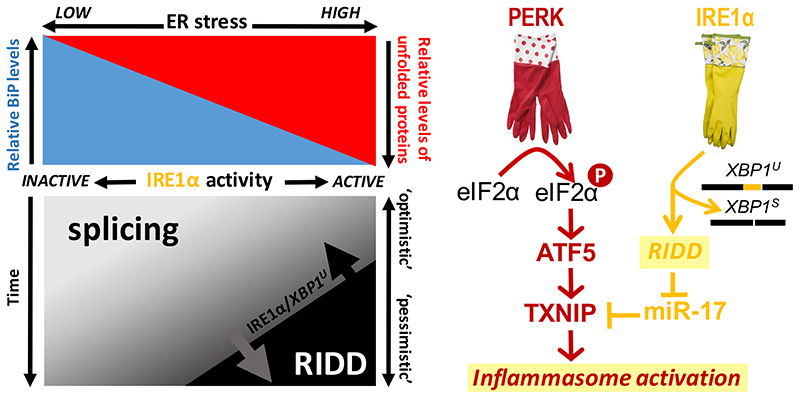

In order to faithfully fulfill as ‘evaluators’ of ER homeostatic readjustment, IRE1α and PERK ought to ‘judge’ ER stress in such a way that they selectively transition to a pro-apoptotic output only if ER homeostasis is ‘deemed’ to be unachievable. In that light, it is of note that RIDD activity has been reported to invoke cell death through cleavage of various microRNAs, most in particular miR-17 [13]. RIDD-controlled decay of miR-17 leads to the stabilization of the mRNA encoding the thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP). TXNIP, in turn, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to promote programmed cell death [34]. Since TXNIP is upregulated through PERK and its downstream effector ATF5 [35], PERK and IRE1α activities converge (at least via TXNIP), as they jointly promote apoptosis when ER homeostatic readjustment is unsuccessful (Figure 3).

Figure 3. RIDD and the transitioning from an ‘optimistic’ to a ‘pessimistic’ UPR.

When ER homeostatic readjustment is successful, it entails that the UPR has ensured that BiP levels eclipse those of its unfolded ER client proteins again [8]. Yet, when unfolded proteins persistently eclipse BiP, PERK and IRE1α are chronically maximally activated [9]. Since persistent IRE1α activity entails that the pre-existing pool of unspliced XBP1U mRNA is depleted (as all will be converted into spliced XBP1S mRNA), IRE1α automatically commits to RIDD as its activity will be directed against other substrates [36]. As such, splicing-to-RIDD transitioning is a readout for persistent maximal IRE1α activation and, hence, for persistent ER stress. Splicing-to-RIDD transitioning can serve as a molecular device for the cell to switch from being ‘optimistic’ to ‘pessimistic’ when ER homeostatic readjustment cannot be achieved. The onset of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning depends also on the ratio of the preexisting levels of XBP1 mRNA over those of IRE1α, which are developmentally determined. An established example of how splicing-to-RIDD transitioning can initiate pro-apoptotic pathways is that TXNIP, which is a downstream target of PERK (via ATF5), will activate the inflammasome. Normally, the TXNIP transcript is targeted for degradation by miR-17, but once IRE1α commits to RIDD of miR-17, TXNIP is de-repressed. Thus, PERK and IRE1α activity converge in jointly driving a pro-apoptotic UPR [13,34,35]. Yet, the outcome of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning, and, hence, of the UPR turning ‘pessimistic’ may differ depending on the cell type, as other RIDD targets come into play.

The concept of RIDD playing a central role once ER homeostatic readjustment fails, is particularly appealing if one takes into consideration that RIDD occurs in competition with splicing of XBP1 mRNA. Prolonged activation of IRE1α (because of unresolved ER stress) ultimately depletes the pre-existing pool of XBP1U mRNA, and, hence, IRE1α automatically commits to RIDD once its preferred substrate, XBP1U mRNA, runs low [36]. It also has been proposed that IRE1α would adopt a different catalytic mechanism to switch from XBP1 mRNA splicing to RIDD activity [37], but in that scenario it remains unclear what upstream molecular machinery would account for IRE1α changing its catalytic modus. By Occam’s razor, the concept of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning due to XBP1U mRNA running low is more plausible, since it would obviate the need for any external driver of IRE1α committing to a RIDD output.

Moreover, in the scenario in which splicing-to-RIDD transitioning depends on XBP1U mRNA being depleted, the developmentally determined ratio in the expression levels of IRE1α over XBP1 mRNA would be key for ER stress sensitivity (Figure 3). This ratio, in fact, varies greatly depending on the tissue, being low in secretory tissues, and high in non-secretory tissues (http://www.gtexportal.org). Indeed, tissue-specific ER stress sensitivity levels appear to vary accordingly. Finally, the activation of the miR-17/TXNIP pathway may represent just one outcome of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning. Diverse cell type-specific (expression levels of) RIDD targets apparently ensure that splicing-to-RIDD transitioning leads to diverse outcomes upon ER homeostatic failure depending on the tissue. In some tissues, RIDD may entail the initiation of pro-apoptotic pathways, while in others it may invoke steps towards dedifferentiation, or to further developmental specialization.

Preemptive Co-Option of the UPR in B-to-Plasma Cell Differentiation

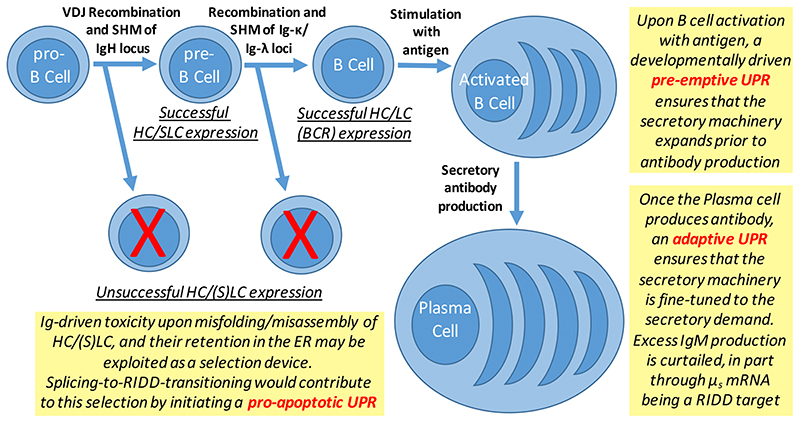

The HeLa-μs model recapitulates how a sudden proteostatic insult would come ‘unexpectedly’, while becoming so uncharacteristically grave for the cell type in question that a ‘pessimistic’ UPR output would be warranted [8,9]. In contrast, the increased demand on the secretory machinery is ‘foreseeable’ for B lymphocytes. Once B lymphocytes are stimulated by antigen, they indeed meticulously prepare for their future secretory tasks as plasma cells: they first stock up on mitochondrial and cytosolic chaperones, probably to sustain increased energy consumption and protein synthesis, while the numbers of chaperones in the ER build up steadily. Finally, the production of secretory antibodies increases exponentially, but only after a lag period, allowing the cell to build an efficient antibody production factory in advance [38]. Accordingly, UPR activation is detectable only at the later stages when IgM is already expressed in bulk [38]. In fact, the morphogenetic changes, including ER expansion, occur in differentiating B cells even when μs is ablated [39]. These insights led to the notion that developmental cues co-opt (branches of) the UPR and, thereby, bypass the necessity of unfolded proteins accumulating in the ER for—at least—the initial stages of UPR activation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. How (re-)purposing the IRE1α/XBP1 UPR branch serves humoral immunity.

The IRE1α/XBP1 branch of the UPR is key for the humoral immune response, since antibody production is compromised when either IRE1α, or XBP1, or both, are ablated [14,29,43–46]. We argue that the purposing and repurposing of the IRE1α/XBP1 branch shapes the B cell lineage at least at three stages. Firstly, when pro-B cells undergo VDJ recombination and somatic hypermutation (SHM): the resulting HCs in many cases are unfit to fold and/or to assemble with SLC [53]. Likewise, recombination and SHM of the Ig-κ/Ig-λ loci in pre-B cells often results in LCs that cannot assemble with the HC into a functional BCR [61]. In either case of unsuccessful HC/(S)LC folding and/or assembly, ER homeostatic failure ensues, and IRE1α may serve as the executor of ‘HC toxicity’ by initiating pro-apoptotic pathways upon splicing-to-RIDD transitioning. Secondly, upon antigen stimulation, B lymphocytes massively induce XBP1 expression [14,42] to an extent that basal IRE1α activity likely yields sufficient XBP1 protein to drive ER expansion in absence of ER stress. As such, an antibody production plant is ready before the onset antibody production [38]. Finally, once bulk antibody production is underway, the HC often accumulates in the ER to (re-)activate the IRE1α/XBP1 branch, such that ensuing XBP1 production reinforces ER function. In the plasma cell, splicing-to-RIDD transitioning does no longer herald apoptosis, since μs mRNA is a key RIDD target. Thus, when all XBP1U mRNA is consumed, RIDD serves to curtail excess secretory HC expression [14,46].

B-cell activation leads to the induction of the transcription factor Blimp-1, which represses the transcription factor BSAP/Pax5 [40,41]. Since BSAP/Pax5 represses XBP1, XBP1 transcription is effectively enhanced upon activation of B cells [42]. When it was discovered that ablation of XBP1 severely compromises plasma cell function [42–44], the UPR was embraced as a key homeostatic control during B-to-plasma cell differentiation [45]. It therefore came as a surprise that concomitant ablation of both IRE1α and XBP1 to a large extent restores plasma cell function [14,46]. The explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that deletion of XBP1 alone causes IRE1α to be constitutively active [14]. As a result, IRE1α displays a gain-of-function activity, because in the absence of its preferred substrate (XBP1U mRNA) it fully commits to RIDD. Since in plasma cells the mRNA encoding μs is a prominent RIDD target, antibody titers drop drastically once XBP1 is deleted. Conversely, antibody titers can be recovered when hyperactivation of IRE1α and its commitment to RIDD is prevented [14], for instance by replacing IRE1α with a mutant allele that cannot be phosphorylated at residue S729 [46].

Altogether, these findings reopen the question of how the UPR is co-opted to facilitate B-to-plasma cell differentiation. In fact, substantial splicing of XBP1 mRNA occurs only in the later stages of plasma cell development [29,47], indicating that early during B-to-plasma cell differentiation, the cells do not suffer from any marked ER stress. How then does the ER expand in the early stages of B cell differentiation? Perhaps it simply is due to XBP1 mRNA expression being induced to such high levels upon B cell activation [42] that even modest IRE1α activity, and the ensuing modest splicing of XBP1 mRNA, leads to production of XBP1s at levels that suffice to drive ER expansion. Thus, upon B cell activation, the IRE1α/XBP1 branch is ‘hypersensitized’ to respond to even the slightest perturbations in ER homeostasis. In that light, it is not surprising that only the IRE1α/XBP1 branch is key to fine-tune antibody secretion in terminally differentiating plasma cells [14,29,46], while the ATF6α branch appears to be dispensable, and the PERK branch even suppressed [48–50].

Plasma Cells are Protected Against ‘Excessive’ ER Stress

While plasma cells do experience ER stress, they are safeguarded from the stress becoming excessive in several ways. The developmentally driven ER expansion [38] in itself likely is protective against ER stress (as will be discussed below in further detail). Moreover, removal of surplus HCs through ERAD is highly efficient in plasma cells [51]. Likewise, excess accumulation of Ig subunits in the ER is curtailed by ER-phagy in plasma cells [52]. Finally, splicing-to-RIDD transitioning of IRE1α activity may herald cell death in various cell types [13,34,35], but such a scenario is unlikely to unfold in plasma cells, not only because the ratio in the expression levels of XBP1 mRNA over those of IRE1α is highly elevated in plasma cells, but also because the μs mRNA is a RIDD target. Similarly, pro-insulin mRNA represents a prominent RIDD target in pancreatic β-cells, in particular once XBP1 is ablated [11,12]. Thus, it appears to be a common feature of professional secretory cells that those mRNAs that encode bulk secretory products have evolved to be RIDD targets so as to curtail excess expression levels. Obviously, any potential pro-apoptotic effects of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning are trumped as an aside.

How ER Stress and the UPR may be Exploited for B Cell Selection

By curtailing excessive levels of μs mRNA, the splicing-to-RIDD transitioning plays a protective role in the plasma cell. Does splicing-to-RIDD transitioning play any role at earlier steps during B cell development? To explore that idea, one should consider that for all ‘regular’ ER clients, selective pressure has been such that they have evolved not to pose insurmountable problems to their being folded and assembled in the secretory pathway. Indeed, germline mutations of ER clients often cause chronic ER stress and disease [6]. The notable exception to the rule that ER clients have been evolutionarily selected for smooth folding and assembly are, of course, those ER clients, which—out of immunological necessity—undergo recombination and/or hypermutation within the individual organism itself. Indeed, the fundamental tenet of adaptive immunology is that both B and T cells achieve to cover a wide repertoire of antigen-recognition. During early B cell development, highly variable antigen-recognizing sequences are generated by sequential and strictly controlled rearrangements of the germline V (variable), D (diversity), and J (joining) regions of the Ig-H, encoding the antibody HC, and the two Ig-L loci, Ig-κ and Ig-λ, encoding light chains (LCs). Subsequent activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)-dependent somatic hypermutation of these VDJ regions further ensures that each of the estimated >1011 different B lymphocytes encodes a unique HC-LC tandem to form a unique antigen-recognizing antibody [53,54]. Yet, a majority of these VDJ recombination events result in aberrant HC sequences due to frame shifts, premature stop codons, or destabilizing mutations [53].

In pre-B cells, a so-called surrogate LC (SLC) acts as a template to test the fitness of the newly recombined HC. Only when a suitable HC is produced that can team up with the SLC to appear on the cell surface, either the Ig-κ or Ig-λ locus undergoes recombination. As a result, the SLC is replaced by the LC, and the mature membrane-bound antibody is formed to be displayed at the cell surface as B cell receptor (BCR) [55,56]. We argue that those HCs that cannot meaningfully team up with (S)LC will be retained in the ER, causing ER homeostatic failure. As such, misfolding-prone HC-driven proteotoxic ER stress may well be responsible for ‘HC toxicity’ [57,58], i.e. that B cells which fail to produce a bona fide HC-SLC tandem or BCR succumb (Figure 4). Indeed, in mice in which both Ig-κ and Ig-λ are ablated, there is almost a complete lack of mature B cells [59]. The only LC-less B cells that do survive express at the cell surface HC in which the CH1 domain is deleted [60], highlighting that the CH1 domain is key for ER retention of the HC, and for eliciting (UPR-driven) HC toxicity, which is in line with our findings in the HeLa-μs model [9]. Also the recombination and somatic hypermutation of the Ig-κ or Ig-λ locus often result in aberrant LCs that provoke proteotoxic ER stress [61], which, analogously, could be co-opted as a counter-selection criterion for defective B cell clones. Thus, aberrant Ig subunit-driven proteotoxic ER stress may complement the positive clonal selection resulting from the ligand-independent, ‘tonic’ pro-survival signal that emanates from functional BCRs [62–64].

In IRE1α-ablated B cells the expression of recombination–activating genes RAG1 and RAG2 appears to be compromised, but the B cells still undergo VDJ recombination. A large fraction of these B cells, however, displays defective BCRs due to the lack of IRE1α activity [29]. The survival of B lymphocytes with defective BCRs is problematic, because these ‘faulty’ B cells compete with bona fide B cells for limited space in peripheral lymphoid tissues. As a result, within the total pool of B cells, a majority will fail to undergo B-to-plasma cell differentiation, which explains why in the IRE1α-ablated mice only limited antibody secretion ensues upon stimulation with antigen [29]. Also these insights are therefore in line with IRE1α activity contributing to the elimination of (pre-)B cells that produce aberrant Ig subunits.

ER Expansion as A Buffer Against Accumulation of Orphan Subunits?

A puzzling question always has been why plasma cells expand their ER far more than pancreatic β-cells, which have the task to synthesize the single subunit product insulin, even though the two cell types release similar bulk amounts of proteins on a daily basis [24,65]. This question is all the more poignant considering that an expanded ER is not even essential to sustain bulk IgM production, since in HeLa cells co-expression of LC and the μs HC at levels on a par with those in plasma cells engenders little, if any, UPR activation, and hence, only minor ER expansion, as long as the IgM subunits are expressed at equivalent levels [8].

In that sense, the arguments put forward above may also shed light on the physiological relevance of ER expansion during B cell differentiation. Namely, when viable B cell clones duly have been selected (and those with a potentially dangerous affinity to a self-antigen eliminated [66]), the resulting pair of HC and LC is highly unique in its antigen recognition, but, potentially, the individual HC and LC subunits in a given B cell may still substantially differ in stability. Ample ER expansion would safeguard against potentially unfavorable HC/LC stoichiometries, in particular, when due to substoichiometric availability of the LC, excess orphan HC subunits would accumulate. The ‘extra storage space’ for surplus HC offered by a maximally expanded ER thus protects plasma cells against HC toxicity.

Is the UPR Exploited to (Counter-)Select Other Lymphoid Cells?

For adaptive immunity, a wide repertoire of T cell receptor (TCR) sequences is equally important as that of the BCR and antibodies. One could envision that similar mechanisms as sketched above for (pre-)B lymphocytes may be operational in maturing T cells: aberrancies of TCR subunits (again generated through recombination and hypermutation events) would elicit ER stress, and the resulting ER stress response is exploited to counter-select against defective TCR-producing T cells. Surprisingly, however, ER stress and UPR activation in T cells thus far have been poorly investigated [67].

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)—known as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in mice—class I receptors need to assemble such that the default subunits form complexes with antigenic peptides that are highly variable in sequence identity. The HLA/MHC class I complex with antigenic peptide therefore is—depending on the peptide—inherently of variable stability. One could argue that due to this inherent variability, antigen presentation might pose a similar challenge to the ER folding machinery as the production of the highly variable TCR, BCR, and antibody complexes. Yet, HLA/MHC class I receptors are expressed virtually by all nucleated cells, which already rules out that their production causes ER stress by default. Conversely, bulk production of these receptors, such as occurs in dedicated antigen presenting cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), might still compromise ER homeostasis. In that vein, it is of interest that XBP1 mRNA is constitutively spliced in DCs [68], specifically in one of the two main conventional DC subsets, cDC1s [69].

While the committal of IRE1α to RIDD activity leads to the depletion of various key components of the antigen presentation machinery [70], it is unlikely that RIDD counter-selects against DCs with improperly assembled MHC/peptide complexes, since RIDD activation does not lead to cell death in these DCs but rather to their survival [15]. Apparently, in DCs it is developmentally ingrained that sustained IRE1α activity entails processing of RIDD targets that act as a decoy to quench potential pro-apoptotic pathways, or rather that the processing of RIDD targets in DCs promotes pro-survival pathways and/or further development.

Still, XBP1 ablation leads to a loss of various other immune cells, including eosinophils [71]. Thus, a recurring theme in the interpretation of (tissue-specific) xbp1 -/- phenotypes is that one should consider that there is a gain of function through excessive RIDD activity of IRE1α, which leads to the initiation of pro-apoptotic pathways in various cell types, while the outcome is different in those cell types in which other, non-pro-apoptotic RIDD targets are prominent.

Concluding Remarks

For decades, antibodies and antibody-producing cells have been goldmines for biologists: break-through discoveries on recombination, splicing, somatic mutation, NF-κB function, and many other fundamental insights have sprung from immunoglobulin-inspired studies. Likewise, BiP was originally found in search of the mechanisms that lie at the basis of allelic exclusion [22,23]. Since then, BiP has been recognized as the master regulator of ER function [72]. In that light, it comes perhaps as no surprise that recent exploitation of Ig-components to study the UPR has yielded valuable new insights [8,9]. The HeLa cell-based models for Ig-driven proteostatic ER stress indeed further solidify the central role of BiP in determining the UPR signaling amplitude. The μs-expressing HeLa model recapitulates how ER stress and UPR activation ensues upon bulk expression of orphan or defective ER client proteins in various cell types and tissues, whether due to a genetic disease or due to somatic mutations. By using a specific block of ERAD, the HeLa-μs model moreover recapitulates how ER homeostatic readjustment may fail. We reason that under such conditions, based on BiP/client ratiometric sensing, the UPR ‘evaluates’ the attempts at restoring ER homeostasis as being unsuccessful.

From the studies summarized here, we argue that the UPR is ideally suited to counter-select against unproductive precursor cells of the immune system, considering the inherent sequence variability of components of the BCR and antibodies (but perhaps also of TCR complexes), and considering that defective, misfolding-prone variants of these molecules cause ER homeostatic failure. We propose that splicing-to-RIDD transitioning of IRE1α activity, and the ensuing initiation of pro-apoptotic pathways conveys such counter-selection. Accordingly, XBP1 mRNA is expressed at low levels in precursor B cells, which would allow stringency in the counter-selection process. Once the precursor cells have obtained the stamp of approval for expressing a functional BCR, XBP1 mRNA levels increase to boost ER expansion, while precluding these cells from undergoing RIDD-elicited apoptosis any further. Furthermore, the outcome of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning varies depending on the cell type, since RIDD targets are tissue-specific. As such, RIDD plays a protective role in DCs, in pancreatic β-cells, and also in plasma cells, because μs mRNA is a RIDD target. Thus, the challenges that lie ahead are to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms that allow the UPR machineries to ‘evaluate’ whether their dealing with a given ER stress is adequate or not, and to decipher how ‘evaluation’ of the success or failure of ER homeostatic readjustment is translated into tissue-specific needs (see Outstanding Questions).

Highlights.

-

◉

ER stress sensing occurs in a ratiometric fashion: the ratio of BiP levels over its clients determines the UPR signaling amplitude. This insight unifies previous models of UPR activation.

-

◉

UPR-driven ER homeostatic readjustment is successful only when BiP levels rise to eclipse (again) those of its clients. Otherwise, homeostatic failure and client-driven proteotoxicity ensues.

-

◉

Upon ER homeostatic failure, the UPR sensor IRE1α is chronically maximally activated, such that, through splicing, it ‘consumes’ available stores of its main substrate XBP1U mRNA, and, as a result, commits to RIDD.

-

◉

Splicing-to-RIDD transitioning thus heralds a shift from an ‘optimistic’ to a ‘pessimistic’ UPR, which may entail apoptosis.

-

◉

Immunologically driven Ig sequence variability inherently leads to ER homeostatic failure in many precursor B cells. Thus, the UPR likely serves to counter-select against ‘faulty’ B cells.

Outstanding Questions.

-

◉

Activation of the UPR occurs when ER client proteins sequester the chaperone BiP, but the UPR sensors are ‘blind’ to non-BiP clients. Yet, also these clients may accumulate in the ER. What UPR-independent pathways are required to deal with BiP-independent ER stress?

-

◉

IRE1α and PERK are essential for the function of some secretory tissues, but dispensable for most other tissues, which suggests that maintenance of ER homeostasis in those tissues relies mainly on the ATF6α/β branches of the UPR. Whether ATF6α/β indeed account for ‘day-to-day’ ER homeostatic control awaits confirmation.

-

◉

The process of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning of IRE1α activity may be generic, as it ties in with IRE1α having depleted its preferred substrate XBP1U mRNA. The outcome of splicing-to-RIDD transitioning, however, is different depending on what RIDD targets come to the fore, which explains why it has been difficult to find a unifying role for RIDD. Hence, it is key to stratify what mRNAs/miRNAs are RIDD targets given the tissue context.

-

◉

For decades, the UPR has been implicated in pro-apoptotic activity upon irremediable ER stress. We predict that (tissue-specific) effectors of the ‘pessimistic’ UPR include some that promote senescence or affect differentiation status, since the clearance of apoptotic cells may be detrimental for the homeostasis of the affected tissue.

-

◉

We infer that ER homeostatic failure, and an ensuing ‘pessimistic’ UPR, are key for the elimination of B cell precursors that produce defective Ig subunits. Yet, formal proof needs to be provided for that scenario, and for whether splicing-to-RIDD transitioning is key in the process.

-

◉

A process reminiscent of VDJ recombination and SHM of the BCR occurs to produce a variety of TCR sequences. By analogy, we argue that a ‘pessimistic’ UPR may drive elimination of T cell precursors that express defective TCR subunits, but also this hypothesis awaits experimental confirmation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Drs Tomás Aragón, Ritwick Sawarkar, and Agnès Delaunay-Moisan for critical reading of the manuscript. EvA acknowledges the Armenise-Harvard foundation, AIRC, and PRIN for financial support. AB acknowledges support from a Fondazione Centro San Raffaele Fellowship. SJ acknowledges the ERC, the FWO and EOS for financial support.

References

- 1.Anelli T, Sitia R. Protein quality control in the early secretory pathway. EMBO J. 2008;27:315–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Anken E, Braakman I. Versatility of the endoplasmic reticulum protein folding factory. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;40:191–228. doi: 10.1080/10409230591008161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hampton RY, Sommer T. Finding the will and the way of ERAD substrate retrotranslocation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrester A, et al. A selective ER-phagy exerts procollagen quality control via a Calnexin-FAM134B complex. EMBO J. 2019;38:e99847. doi: 10.15252/embj.201899847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fregno I, et al. ER-to-lysosome-associated degradation of proteasome-resistant ATZ polymers occurs via receptor-mediated vesicular transport. EMBO J. 2018;37:e99259. doi: 10.15252/embj.201899259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hetz C, Papa FR. The Unfolded Protein Response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 2018;18:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakunts A, et al. Ratiometric sensing of BiP-client versus BiP levels by the unfolded protein response determines its signaling amplitude. eLife. 2017;6:e27518. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitale M, et al. Inadequate BiP availability defines endoplasmic reticulum stress. eLife. 2019;8:e41168. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollien J, Weissman JS. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2006;313:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipson KL, et al. The role of IRE1α in the degradation of insulin mRNA in pancreatic β-cells. PloS One. 2008;3:e1648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han D, et al. IRE1α kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 2009;138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Upton JP, et al. IRE1α cleaves select microRNAs during ER stress to derepress translation of proapoptotic Caspase-2. Science. 2012;338:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1226191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benhamron S, et al. Regulated IRE1-dependent decay participates in curtailing immunoglobulin secretion from plasma cells. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:867–876. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavernier SJ, et al. Regulated IRE1-dependent mRNA decay sets the threshold for dendritic cell survival. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:698–710. doi: 10.1038/ncb3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox JS, et al. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mori K, et al. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell. 1993;74:743–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90521-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertolotti A, et al. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen J, et al. ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev Cell. 2002;3:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas IG, Wabl M. Immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein. Nature. 1983;306:387–389. doi: 10.1038/306387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bole DG, et al. Posttranslational association of immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein with nascent heavy chains in nonsecreting and secreting hybridomas. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1558–1566. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendershot LM, Sitia R. In: Molecular Biology of B Cells. Honjo T, Alt FW, Neuberger MS, editors. Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. Immunoglobulin assembly and secretion; pp. 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner BM, Walter P. Unfolded proteins are Ire1-activating ligands that directly induce the unfolded protein response. Science. 2011;333:1891–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.1209126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karagöz GE, et al. An unfolded protein-induced conformational switch activates mammalian IRE1. eLife. 2017;6:e30700. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, et al. ATF6α optimizes long-term endoplasmic reticulum function to protect cells from chronic stress. Dev Cell. 2007;13:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto K, et al. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6α and XBP1. Dev Cell. 2007;13:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang P, et al. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the Pancreas. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3864-3874.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urano F, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang K, et al. The unfolded protein response sensor IRE1alpha is required at 2 distinct steps in B cell lymphopoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:268–281. doi: 10.1172/JCI21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reimold AM, et al. An essential role in liver development for transcription factor XBP-1. Gen Dev. 2000;14:152–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee AH, et al. XBP-1 is required for biogenesis of cellular secretory machinery of exocrine glands. EMBO J. 2005;24:4368–4380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwawaki T, et al. Function of IRE1α in the placenta is essential for placental development and embryonic viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16657–16662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903775106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwawaki T, et al. IRE1α disruption causes histological abnormality of exocrine tissues, increase of blood glucose level, and decrease of serum immunoglobulin level. PloS One. 2010;5:e13052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lerner AG, et al. IRE1alpha induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 2012;16:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oslowski CM, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates ER stress-induced β-cell death through initiation of the inflammasome. Cell Metab. 2012;16:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Anken E, et al. A RIDDle solved: why an intact IRE1α/XBP-1 signaling relay is key for humoral immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:641–645. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tam AB, et al. Ire1 has distinct catalytic mechanisms for XBP1/HAC1 splicing and RIDD. Cell Rep. 2014;9:850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Anken E, et al. Sequential waves of functionally related proteins are expressed when B cells prepare for antibody secretion. Immunity. 2003;18:243–253. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu CC, et al. XBP-1 regulates signal transduction, transcription factors and bone marrow colonization in B cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:1624–1636. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaffer AL, et al. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 2002;17:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin KI, et al. Blimp-1- dependent repression of Pax-5 is required for differentiation of B cells to immunoglobulin M-secreting plasma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4771–4780. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4771-4780.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaffer AL, et al. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2004;21:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reimold AM, et al. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tirosh B, et al. XBP-1 specifically promotes IgM synthesis and secretion, but is dispensable for degradation of glycoproteins in primary B cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:505–516. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwakoshi NN, et al. Plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response intersect at the transcription factor XBP-1. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:321–329. doi: 10.1038/ni907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang CH, et al. Phosphorylation of IRE1 at S729 regulates RIDD in B cells and antibody production after immunization. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:1739–1755. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201709137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gass JN, et al. Activation of an unfolded protein response during differentiation of antibody-secreting B cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49047–49054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gass JN, et al. The unfolded protein response of B-lymphocytes: PERK-independent development of antibody-secreting cells. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masciarelli S, et al. CHOP-independent apoptosis and pathway-selective induction of the UPR in developing plasma cells. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:1356–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aragon IV, et al. The specialized unfolded protein response of B lymphocytes: ATF6alpha-independent development of antibody-secreting B cells. Mol Immunol. 2012;51:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fagioli C, Sitia R. Glycoprotein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mannose trimming by endoplasmic reticulum mannosidase I times the proteasomal degradation of unassembled immunoglobulin subunits. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12885–12892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pengo N, et al. Plasma cells require autophagy for sustainable immunoglobulin production. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:298–305. doi: 10.1038/ni.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jung D, et al. Mechanism and control of V(D)J recombination at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Ann Rev Immunol. 2006;24:541–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pavri R, Nussenzweig MC. AID targeting in antibody diversity. Adv Immunol. 2011;110:1–26. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387663-8.00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karasuyama H, et al. Surrogate light chain in B cell development. Adv Immunol. 1996;63:1–41. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60853-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Melchers F, et al. Repertoire selection by pre-B-cell receptors and B-cell receptors, and genetic control of B-cell development from immature to mature B cells. Immunol Rev. 2000;175:33–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Köhler G. Immunoglobulin chain loss in hybridoma lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2197–2199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wabl M, Steinberg C. A theory of allelic and isotypic exclusion for immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6976–6978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.22.6976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zou X, et al. Block in development at the pre-B-II to immature B cell stage in mice without Ig kappa and Ig lambda light chain. J Immunol. 2003;170:1354–1361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zou X, et al. Heavy chain-only antibodies are spontaneously produced in light chain-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3271–3283. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srour N, et al. A plasma cell differentiation quality control ablates B cell clones with biallelic Ig rearrangements and truncated Ig production. J Exp Med. 2016;213:109–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lam KP, et al. In vivo ablation of surface immunoglobulin on mature B cells by inducible gene targeting results in rapid cell death. Cell. 1997;90:1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kraus M, et al. Survival of resting mature B lymphocytes depends on BCR signaling via the Igalpha/beta heterodimer. Cell. 2004;117:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srinivasan L, et al. PI3 kinase signals BCR-dependent mature B cell survival. Cell. 2009;139:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Müller A, et al. A global approach for quantitative super resolution and electron microscopy on cryo and epoxy sections using self-labeling protein tags. Sci Rep. 2017;7:23. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00033-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goodnow CC, et al. Cellular and genetic mechanisms of self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:590–597. doi: 10.1038/nature03724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grootjans J, et al. The unfolded protein response in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:469–484. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iwakoshi NN, et al. The transcription factor XBP-1 is essential for the development and survival of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2267–2275. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Osorio F, et al. The unfolded-protein-response sensor IRE-1α regulates the function of CD8α+ dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:248–57. doi: 10.1038/ni.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Osorio F, et al. Antigen presentation unfolded: identifying convergence points between the UPR and antigen presentation pathways. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;52:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bettigole SE, et al. The transcription factor XBP1 is selectively required for eosinophil differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:829–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hendershot LM. The ER chaperone BiP is a master regulator of ER function. Mt Sinai J Med. 2004;71:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]