Abstract

Unspecific peroxygenases (UPO) are glycosylated fungal enzymes that can selectively oxidize C-H bonds. UPOs employ hydrogen peroxide as oxygen donor and reductant. With such an easy-to-handle co-substrate and without the need of a reducing agent, UPOs are emerging as convenient oxidative biocatalysts. Here, an unspecific peroxygenase from Hypoxylon sp. EC38 (HspUPO) was identified in an activity-based screen of six putative peroxygenase enzymes that were heterologously expressed in Pichia pastoris. The enzyme was found to tolerate selected organic solvents such as acetonitrile and acetone. HspUPO is a versatile catalyst performing various reactions, such as the oxidation of prim- and sec-alcohols, epoxidations and hydroxylations. Semi-preparative biotransformations were demonstrated for the non-enantioselective oxidation of racemic 1-phenylethanol rac -1b (TON = 13000), giving the product with 88% isolated yield, and the oxidation of indole 6a to give indigo 6b (TON = 2800) with 98% isolated yield. HspUPO features a compact and rigid three-dimensional conformation that wraps around the heme and defines a funnel-shaped tunnel that leads to the heme iron from the protein surface. The tunnel extends along a distance of about 12 Å with a fairly constant diameter in its innermost segment. Its surface comprises both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups for dealing with small-to-medium size substrates of variable polarities. The structural investigation of several protein-ligand complexes revealed that the active site of HspUPO is accessible to molecules of varying bulkiness and polarity with minimal or no conformational changes, explaining the relatively broad substrate scope of the enzyme. With its convenient expression system, robust operational properties, relatively small size, well-defined structural features, and diverse reaction scope, HspUPO is an exploitable candidate for peroxygenase-based biocatalysis.

Keywords: substrate recognition, protein tunnels, biocatalytic oxidation, monooxygenase, peroxygenase

Introduction

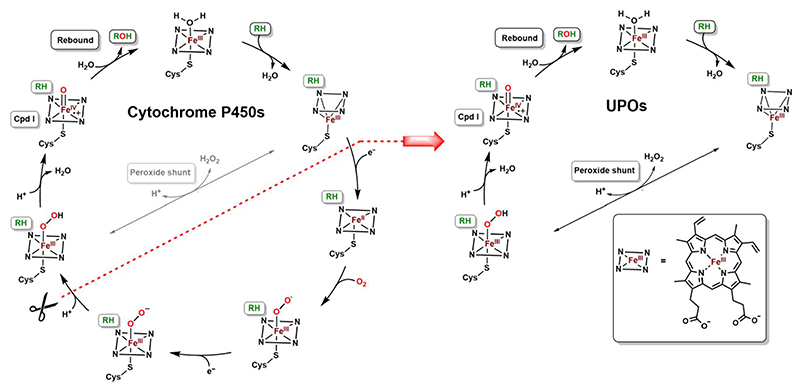

The C-H bond is relatively inert and its oxidation is one of the most challenging conversions in chemistry (1–5). The cytochrome P450s have been historically considered as a particularly attractive group of enzymes to perform oxidative reactions targeting C-H groups (6). Their reaction mechanism relies on the reductive activation of molecular oxygen through a stepwise catalytic cycle that involves the formation of the highly oxidized and reactive oxo-ferryl intermediate (Scheme 1) (7). The direct interaction between this so-called compound I and the substrate affords substrate oxygenation. Cytochrome P450s require a reducing agent, such as NAD(P)H, and auxiliary flavoproteins that respectively donate and transport electrons (8). The mandatory presence of this complex protein machinery makes cytochrome P450s prone to the “oxygen dilemma”: the complexity of the electron transport mediators inevitable promotes uncoupling pathways that waste reducing equivalents and significantly lower the catalytic turnover (9). These limitations, summed to the low operational stability as purified proteins, hampered the use of cytochrome P450s as a general catalyst for large-scale biocatalytic applications. Several solutions have been proposed to overcome these issues (10). They include various strategies such as the usage of whole microbial cells (11), the enzymatic regeneration of the reduced nicotinamide cofactor, the co-expression with NADPH-regenerating systems (12–13), and the exploitation of engineered cytochrome P450s endowed with peroxygenase activities (14–18).

Scheme 1. Comparison between the mechanisms of cytochrome P450s and UPOs.

In 2004, Ullrich et al. documented the discovery of a new secreted enzyme from the fungus Agrocybe aegerita (19). After its initial classification as an haloperoxidase, it was finally recognized as unspecific peroxygenase (UPO) and considered as the first member of a new sub-subclass of oxidoreductases (E.C 1.11.2.1) (20). This milestone discovery has been followed by an increasing interest for UPOs which were defined as the “generational successors” to P450s (21–22). UPOs are highly glycosylated, naturally secreted, fungal heme-enzymes that combine a wide versatility in terms of substrate scope with a relatively simple reaction mechanism that does not need an external electron donor (23). In their reaction cycle, compound I is formed directly from the reaction between H2O2 and the protoporphyrin IX in the enzyme core (Scheme 1) (24). The remarkable feature of this reaction is the dual function of the H2O2 co-substrate, acting both as oxygen donor and reductant that directly reacts with the enzyme prosthetic group.

To date, just the crystal structures of two peroxygenases are available, namely the one from Agrocybe aegerita (PDB: 2YOR for wild-type and 5OXU for the PaDa-I secretion variant) (25–26) and from Marasmius rotula (PDB: 5FUK; unpublished). Both crystal structures highlighted and elucidated the distinctive features of UPOs whose core is mainly composed by α-helices that organize the active site around the heme’s iron center. The active site is mainly cladded with aromatic residues conferring a preference for mildly hydrophobic substrates. UPOs have been demonstrated to be active as oxygenases on many compounds, ranging from the aliphatic propane (27) and fatty acids (28) to the aromatic naphthalene (29–31), benzene (32–33), phenethylamine (21), and styrene (34). A number of strategies have been described to improve the challenging expression these enzymes (35–39). We identified a highly promising novel unspecific peroxygenase from Hypoxylon sp. EC38 (HspUPO). The enzyme can efficiently be expressed as secreted recombinant protein in P. pastoris and retains the activity under moderately harsh conditions. Moreover, HspUPO performs various types of reactions including hydroxylation, epoxidation and alcohol oxidation. Additionally, we were able to successfully crystallize HspUPO in the presence of different ligands, highlighting a rigid scaffold embedding a funnel for substrate diffusion to the heme.

Experimental Section

Strain generation

Plasmids were obtained by bisy (bisy GmbH, Hofstaehen, Austria) and generated as described in (40). These vectors are optimized to drive the expression of the full-length protein fused with the Mating-Factor signal sequence [MKSLSFSLALGFGSTLVYS] allowing the secretion of the target polypeptide under the control of a bidirectional promotor PPDF. The plasmids were transformed in Pichia pastoris, strain BSYBG11 (bisy GmbH, Hofstaehen, Austria), to afford the integration of the target cassette into the recipient genome by homologous recombination.

Small scale protein expression

Single colonies of the transformed Pichia pastoris cells, grown on YPD agar (1% yeast extract; 2% peptone; 2% dextrose; 2% agar) and selected with Zeocin (final 100 μg/mL), were picked, inoculated in 45 mL of Buffered Minimal Dextrose medium (100 mM potassium phosphate pH 6; 1.34% YNB; 4·10-5% biotin; 1% dextrose), and incubated at 28 °C with 200 rpm shaking for 60 hours. The induction was then started by the addition of 5 mL of Buffered Minimal Methanol medium (100 mM potassium phosphate pH 6; 1.34% YNB; 4·10-5% biotin; 0,5% methanol). 12, 24 and 36 hours later, 0.5 mL of pure methanol were added to the culture media. After a total of 180 hours of cultivation, the cell cultures were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 8000 rpm.

Activity based screenings

The cell free supernatant containing the secreted enzymes was screened for activity using two assays.

2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) assay

The assay mix solution consisted of 1 mL 20x ABTS (440 mg of ABTS dissolved in 50 mL of 50 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5) and 19 mL of 200 mM sodium citrate pH 4.5. In the 96-well plate (Greiner), 15 μL of cell free supernatant were mixed with 140 μL of assay solution and the reaction was started upon the addition of 1.75 μL of 30% H2O2 in each well. Product formation was monitored following the increase in absorbance at 405 nm (ε 405= 36000 M-1 cm-1) for 15 minutes.

Naphthalene assay

The assay mix solution consisted of 2 mL naphthalene (4 mM, stock solution prepared in pure acetone) and up to 10 mL with 200 mM citrate-phosphate pH 7. Each well contained 15 μL of cell free supernatant and 140 μL of assay mix. The reaction was started upon the addition of 1.75 μL of 30% H2O2. Product formation was detected at 310 nm (ɛ 405= 2030 M-1 cm-1).

The volumetric activities of the enzymes were calculated as follows:

Where:

U = units per mL [μmol * mL –1 * min –1]

Vtot = total assay volume [mL]

ΔAΔt –1= slope [ΔAmin –1]

D= Dilution factor of the sample

d= layer thickness [cm]

vsample = sample volume [mL]

ɛnm= extinction coefficient [mL * μmol –1 cm–1]

Expression in shaking flasks

Pre-cultures were prepared by picking a single colony and inoculating it in 5 mL YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) supplemented with Zeocin (100 μg/mL final) followed by an overnight incubation at 28 °C with 200 rpm shaking. After the initial growth, the pre-culture was splitted and 2.5 mL were added to 450 mL of Buffered Minimal Dextrose medium and grew at 28 °C, 200 rpm shaking for 72 hours. The induction was started with the addition of 50 mL of Buffered Minimal Methanol medium and every 12 hours, for a total of 72 hours, 5 mL of pure methanol were supplemented to the culture. The culture was then harvested by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 15 minutes and the resulting decanted supernatant was sterile filtrated prior to test enzymatic activity as described in the previous paragraph.

Fermentation and purification

HspUPO was expressed in P. pastoris using a 5 L glass vessel fermenter (Bioflo 3000) filled with Basal Salts Medium (26.7 mL/L 85% phosphoric acid, 0.93 g/L CaSO4 ·2H2O, 14.9 g/L MgSO4 ·7H2O, 18.2 g/L K2SO4, 4.13 g/L KOH; 40 g/L glycerol, initial volume: 3 L) supplemented with 4.35 mL/L PTM1 trace salts and 4·10-5% biotin. The pH was set to 5.0 and kept constant with ammonium hydroxide solution (30%). The temperature was set to 28 °C. The fermentation batch phase was started by inoculating 0.2 L of P. pastoris pre-culture, grown for 16 h in baffled flask on YPD medium at 200 rpm shaking and 28 °C. After 12 h, the glycerol in the basal salt medium was totally consumed leading to a drop in the dissolved oxygen concentration, that was always kept above 30%. At this stage, the culture was supplemented with 50% (w/v) glycerolfeed containing 12 mL/L PTM1 trace salts and 4·10-5% biotin, until the cell density was 180 g/L. Methanol feed (0.5% v/v final concentration) was started at the end of the glycerol fed-batch phase, when dissolved oxygen concentration spiked at 80%, and lasted for 72 h. At the end of the fermentation, cell culture was clarified by centrifugation at 70’000 g for 20 minutes and the obtained supernatant was then decanted and filtrated with 0,22 μm filters (Millipore). Using a cross-flow device (Sartorius), as final downstream process, the supernatant was then concentrated 6-fold, buffer exchanged to 10 mM potassium phosphate pH 6 and stored at -20°C. Polished supernatant was dialyzed overnight against 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8 (Buffer A) using 10 kDa dialysis cassette (Thermofisher). The day after, it was loaded by Akta System (Cytiva) equipped with a multiwavelength detector (set at 280/350/420 nm) into a CaptoQ column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with buffer A. After washing (5 column volumes) with buffer A, a linear ascending salt gradient (0-50% 1M NaCl) was applied to elute bound proteins. Fractions containing the purified proteins were analyzed by SDS Page and fractions containing the enzyme, with an appropriate Reinheitszahl value (Abs420/Abs280; experimental value of 1.8 vs the theoretical value of 1.9), were pooled together and incubated overnight with the homemade 6xHis-EndoH deglycosylase (5 mg/mL) in ratio of 3:1 (mgHspUPO:mgENDOH). While incubating, the protein mix was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.8, to remove the excess of salt. The resulting sample was loaded, on His-Trap column (5 mL, Cytiva) to remove the His-tagged ENDOH while the protein of interest was collected in the flow through. Fractions were then pooled together, concentrated with Amicon 3K (Millipore) until an appropriate volume and then loaded on size-exclusion HiPrep Superdex 75 16/60 (Cytiva), previously equilibrated with storage buffer 50 mM Hepes pH 7.8 (Buffer B). Protein fractions were concentrated with Amicon 3K prior to crystallization screenings.

Protein crystallization and structure determination

Extensive crystallization screenings were performed with several commercial kits and using an Oryx 8 robot (Douglas instruments) in sitting drop plates (Swissci, Molecular Dimension). Crystallization droplets were prepared with a 1:1 volume ratio by mixing 11 mg/mL protein in 50 mM Hepes pH 7.8 with the reservoir solution. Promising conditions were optimized by manually prepared sitting drop plates (Cryschem, Hampton) increasing drop volume up to 1 μL. By using nylon loops (Hampton research) crystals were harvested and cryocooled in liquid nitrogen. Soaking experiments (0.5 h) with 1-phenylimidazole and styrene were performed in cryoprotectant solutions consisting of 20% PEG500 MME, 10% PEG20000, 0.1 M MES monohydrate pH 6.5 and the compound of interest (15 mM), followed by flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen. Xray diffraction data were collected at Swiss Light Synchrotron in Villigen, Swizerland (SLS), at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France (ESRF) and at the Diamond Light Source in Didcot, United Kingdom. Diffraction images were processed with XDS (41) and Aimless of the CCP4i package (42). Structure solution was performed with Molrep using 5FUK as searching model for molecular replacement (43). Atomic models were refined with Refmac5 (44) and Coot (45). Figures were created by use of ChimeraX (46). Superpositions were performed with DALI (47).

Activities and steady-state kinetic analysis

HspUPO activities were determined by absorbance-based methods using 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid diammonium salt (ABTS), indole, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol, 5-nitro-1,3-benzodioxole, 3,4-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol, benzyl alcohol as substrates. The reactions were started by the addition of hydrogen peroxide (2 mM final concentration). Prior to steady state kinetic experiments, optimal pH values were determined in McIlvaine (pH 3-8) and borate saline (pH 9) buffers. Specific activities were determined by measuring the initial rates of product formation with varying substrates concentrations. The assay mixture consisted of 0.05-1.5 μM HspUPO and McIlvaine buffer pH 4 (ABTS and 3,4-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol), pH 5 (2,6-dimethoxyphenol) and pH 7 (indole, 5-nitro-1,3-benzodioxole and benzyl alcohol). Measurements were carried out at 25 °C using Cary100 spectrophotometer (Agilent) and product formation was followed monitoring the reactions at 405 nm for ABTS (ɛ 405= 36000 M-1cm-1), 670 nm for indole (ɛ 670= 4800 M-1cm-1), 469 nm for 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (ɛ 469= 27500 M-1cm-1), 425 nm for 5-nitro-1,3-benzodioxole (ɛ 425= 9700 M-1cm-1), 310 nm for 3,4-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol (ɛ 310= 9300 M-1cm-1), and 280 nm for benzyl alcohol (ɛ 280= 1400 M-1cm-1). Data were fit to Michaelis-Menten equation and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software 6.0. Each point was assayed in duplicate.

Temperature and solvents sensitivity

HspUPO (final concentration 1 μM) was mixed with 200 mM sodium citrate pH 4.5 (final volume 400 μl). The mix was then splitted in 20 μl samples and each of them was incubated, using a Thermocycler, at 35, 40, 50 and 60°C. An aliquot from each sample was tested for enzyme activity at different time points (10, 30, 60 and 90 minutes). The blank measurement was performed by mixing HspUPO (final concentration 50 nm), ABTS (final concentration 30 μM) in 200 mM sodium citrate pH 4.5 and the reaction was started upon the addition of H2O2 (2 mM final concentration). Tolerance to solvents was assayed with the ABTS and indole as substrates in presence of different increasing concentrations of acetone, acetonitrile and DMSO (2, 5, 10, 20 and 30%). The mix used for ABTS oxidation assay consisted of HspUPO (final concentration 50 nm), ABTS (final concentration 30 μM), increasing concentrations of solvent in 200 mM sodium citrate pH 4.5. The mix used for the indigo production assay consisted of HspUPO (final concentration 1.5 μM), indole (final concentration 100 μM; stock solution solubilized in acetone or acetonitrile), increasing concentrations of solvents in 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4. The reaction was started by the addition of H2O2 (2mM final concentration) and was carried out at 25 °C. Equation used to calculate residual activity (%):

kcat(obs) = kcat calculated for each temperature/solvent percentage

kcat (standard)= kcat calculated with standard assay conditon

Biotransformations

Reactions on a 1 mL scale were carried out in crimp top glass vials (1.5 mL volume) with a septum in horizontal adjustment in a benchtop incubator at 30°C and 500 rpm. The reaction mixture contained HspUPO (7 μM) and the substrate (1a-6a, 10 mM, 50 μL of a 200 mM stock in acetonitrile, added last) in tricine buffer 100 mM, pH 7.5 with 5% (v/v) acetonitrile. Conversion was started by the continuous addition of in total 40 μL of a 0.5 M H2O2 solution in reaction buffer (10 μL/h over 4 h for 1a-5a, 40 μL/h over 1 h for 6a, final concentration of H2O2: 20 mM, 2 equiv.) with a kdScientific pump, equipped with 1 mL Omnifix®-F syringes from BRAUN (Ø 4.7 mm) and 100 Sterican® needles (Ø 0.80 mm x 120 mm). After completion of H2O2 addition the reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 μL catalase from M. lysodeikticus (170000 U/mL) and 15 mins of incubation at 500 rpm and room temperature to quench excess H2O2. Reactions containing substrates 1a,3a-5a and rac-1b were extracted with ethyl acetate (2 x 500 μL), dried over Na2SO4 and analyzed on GC. Reactions containing substrate 2a were diluted with acetonitrile (1 mL, dilution factor = 2) thoroughly vortexed, centrifuged (14650 rpm, 5 min, room temperature) and filtered prior to analysis on HPLC. Reactions containing substrate 6a were directly centrifuged which led to accumulation of the insoluble 6b as a pellet on the bottom of the vial. The supernatant was removed and treated as with substrate 2a. The remaining dark-blue pellet was dried under a gentle air-flow and dissolved in DMSO (dilution factor = 10). The aqueous supernatant as well as the DMSO solute were analyzed individually on HPLC.

Semi-preparative scale biotransformations

Synthesis of 1c: The reaction was carried out on a 20 mL scale in a microwave vial with a septum cap in horizontal adjustment in a benchtop incubator at 30°C and 300 rpm. The reaction mixture contained HspUPO (cfinal = 7 μM) and the substrate rac-1b (244 mg, added as 2 mL of a 1 M stock in acetonitrile, cfinal = 100 mM) in tricine buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5) with 10 vol% MeCN. The conversion was started by the continuous addition of in total 1.6 mL of a 1375 mM H2O2 solution in reaction buffer (400 μL/h over 4 h, cfinal =: 110 mM, 1.1 equiv.) with a kdScientific pump, equipped with a 5 mL Omnifix®-F syringe from BRAUN (Ø 10 mm) and a 100 Sterican® needle (Ø 0.80 mm x 120 mm). After completion of H2O2 addition, the reaction was extracted (3x 20 mL ethyl acetate). The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the product was purified by flash chromatography (cyclohexane/ethyl acetate, 9:1). Synthesis of 6b: The reaction vessel and adjustment was identical to the conditions described above for 1c. The reaction mixture contained HspUPO (cfinal = 7 μM), indole 6a (46.8 mg, directly dissolved in reaction buffer, cfinal = 20 mM) in tricine buffer 100 mM, pH 7.5. The conversion was started by the continuous addition of in total 0.8 mL of a 550 mM H2O2 solution in reaction buffer (800 μL/h over 1 h, cfinal = 22 mM, 1.1 equiv.). After completion of H2O2 addition the reaction was stopped by the addition of 40 μL catalase from M. lysodeikticus (170000 U/mL) and 15 min of incubation at 500 rpm at room temperature to quench excess H2O2. The reaction solution was then transferred to two 15 mL plastic tubes and centrifuged to separate the insoluble indigo from the aqueous phase. The supernatant was removed and analyzed as stated for 1 mL scale biotransformations. The remaining indigo pellet was washed 3 times with deionized H2O in order to remove any buffer salt residues and the wet pellet was then dried by lyophilization. The structure of both preparative scale biotransformation products 1c and 6b was verified by NMR.

Results and Discussion

Peroxygenase candidate screening and HspUPO isolation

To identify an efficient and versatile UPO, six enzyme candidates of fungal origin were tested. They were selected to represent a sufficiently diverse panel of putative peroxygenases as predicted from the similarity of their amino acid sequences to the sequence of UPO from Agrocybe aegerita (25) (Table 1). The enzymes were expressed as secreted recombinant proteins using P. pastoris with satisfactory secretion levels (0.2 g/L). We probed the peroxidase and peroxygenase activities of the candidate enzymes using two potential substrates; 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS; peroxidase assay, pH 4.5) and naphthalene (peroxygenase assay, pH 7). For both substrates, convenient spectrophotometric assays were employed. Although all UPO candidates exhibited activities when expressed on a 0.45 L scale (Table 1), it became clear that when performing the protein expression on a 5 L scale, only the enzyme from Hypoxylon sp. EC38 (HspUPO) fully retained its heme cofactor when purified, while all other enzymes mostly became inactive. Thus, HspUPO emerged as the logical candidate for further biochemical and structural studies (see Figure S1 for details about the purification procedures and yields).

Table 1. Screening of UPO candidates.

| Source of origin | Accession code | Sequence identity (%) with AaeUPOa | Relative activity ABTS/Naphthaleneb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agrocybe aegerita | B9W4V6c | 100 | 100/100 |

| Aspergillus brasiliensis | OJJ73116.1c | 35 | 200/68 |

| Hypoxylon sp. EC38(HspUPO) | OTA57433.1c | 30 | 277/53 |

| Podospora anserina | XP_001911526.1c | 28 | 52/16 |

| Daldinia sp. | OTB17553.1c | 30 | 22/17 |

| Aspergillus niger | GAQ45152c | 34 | 270/30 |

| Aspergillus niger | XP_001390900.2d | 33 | 301/33 |

UPO from Agrocybe aegerita (PDB ID: 2YOR) (25).

The activity of 15 μ1 of cell free supernatant using ABTS and naphthalene, relative to the enzyme from Agrocybe aegerita which used as a reference.

UniPROT database.

Database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Steady state kinetics on HspUPO

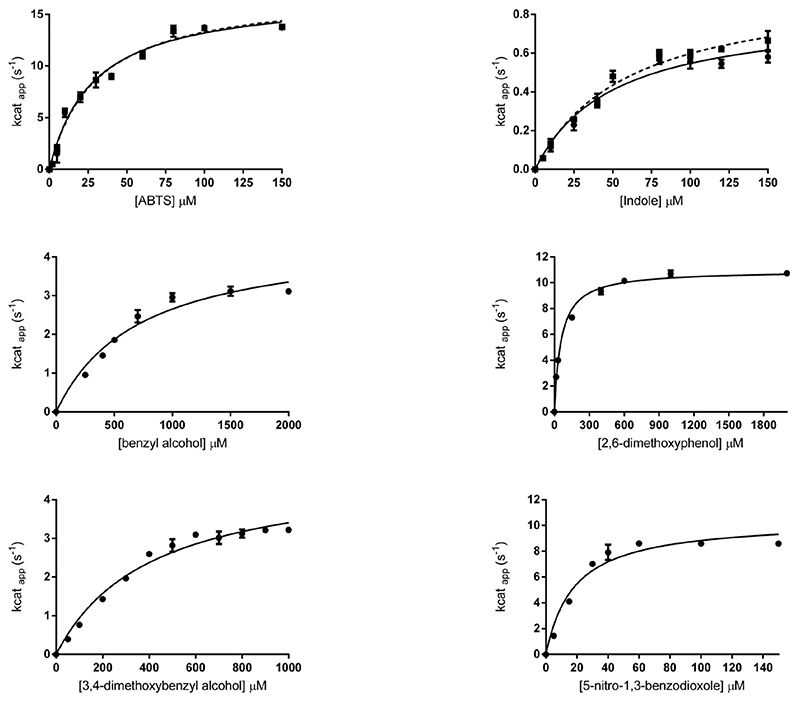

In the early stages of the project, we observed that addition of indole and H2O2 to the secreted media immediately led to a blue color suggesting that HspUPO converts indole to indigo. Therefore, we initially chose indole to study the steady-state kinetics of a reaction that involves substrate oxygenation (peroxygenase activity). We further used ABTS to probe a substrate-oxidation reaction (peroxidase activity). HspUPO oxidizes efficiently ABTS (kcat= 16.94 s-1) whereas a slower – yet pronounced - catalytic turnover was observed for indole (kcat = 0.79 s-1). Both ABTS and indole exhibited remarkably low KM values of ~30-50 μM so that their activities reached the plateau at about 150 μM concentrations (Figure 1 and Table 2). Based on these initial promising observations, we expanded our analysis to other potential substrates; benzyl alcohol, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol, 3,4-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol and 5-nitro-1,3-benzodioxole (35). For all these compounds, we observed good activities with kcat values in the range of 3-12 s-1 (Table 2 and Figure 1). In summary, HspUPO proved to be active on several diverse substrates.

Figure 1. Biochemical characterization of HspUPO.

Michaelis-Menten curves for six substrates. ABTS and indole were evaluated also using the deglycosylated HspUPO (dashed lines).

Table 2. Steady state kinetic parametera.

| Substrate | kcat (s-1) | KM (μM) | kcat/KM (s-1μM-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS | 17.29 ± 0.73 | 30 ± 3.65 | 0.57 |

| Indole | 0.89 ± 0.055 | 54 ± 8.16 | 0.016 |

| Benzyl alcohol | 4.56 ±0.39 | 680 ± 0.14 | 0.006 |

| 2,6-Dimethoxyphenol | 11 ±0.17 | 57.5 ± 5 | 0.191 |

| 3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl alcohol | 7,15 ± 0.58 | 758 ± 100 | 0.01 |

| 5-Nitro-1,3-benzodioxole | 10.4 ± 0.55 | 18 ± 3.42 | 0.57 |

Operational robustness of HspUPO

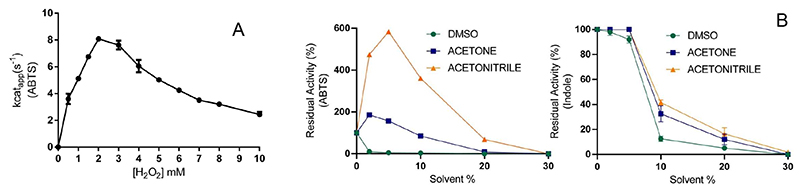

Beside the advantage of bypassing the need of expensive and demanding electron donors, the H2O2 co-substrate may come with a price: the potential oxidative damage inflicted to the protein and reactants used in the biotransformations. Therefore, we probed the capacity of HspUPO to stand relatively high hydrogen peroxide concentrations for prolonged incubation times. We conducted these experiments employing HspUPO with ABTS as substrate (Figure 2A). Rewardingly, the enzyme retained 75% and 40% of the activity in the presence of 5 mM and 10 mM H2O2 whereas the optimal activity was observed at 2 mM H2O2 (kcat ~ 8 s-1). A similar pattern was reported for UPO from Agrocybe aegerita (19). Our data on the Hypoxylon sp enzyme thereby confirm that UPOs are not severely affected by elevated hydrogen peroxide concentrations as needed for efficient biotransformations.

Figure 2. Conditions for HspUPO optimal activity.

A) To probe for the sensitivity towards hydrogen peroxide, the assay mixtures consisted of 200 mM sodium citrate pH 4.5, 30 μM ABTS, 50 nM HspUPO and increasing concentration of H2O2. B) Solvent tolerance was probed in reaction mixtures consisting of 200 mM sodium citrate pH 4.5, 2 mM H2O2, 30 μM ABTS and 50 nM HspUPO. In the experiments performed with indole, the reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4, 2 mM H2O2, 100 μM indole, and 1.5 μM HspUPO. Each datapoint represents the mean and standard deviation from two measurements.

Hydrophobic substrates require a range of solvents for improving substrate availability in the aqueous phase. Thus, the solvent tolerance of native HspUPO was assessed towards several commonly used solvents; DMSO, acetone and acetonitrile. DMSO was hardly tolerated by HspUPO when assayed with ABTS as substrate. Indeed, the residual activity dropped to near 0% already with 2% (v/v) DMSO (Figure 2B, green solid line). To provide additional validation to this finding, we investigated the impact of DMSO on indole conversion (Figure 2B, green solid line). With this substrate, the tolerance to DMSO was slightly better as compared to the activity loss registered for ABTS. As observed for other peroxygenases (i.e. Agrocybe aegerita UPO), DMSO appears to be an inhibitor of HspUPO, likely by binding to the iron center (26). In general, the activity was retained as long as the DMSO percentage was no higher than 5%.

On the other hand, acetone and acetonitrile boosted the activity of HspUPO towards ABTS by up to twofold (2% acetone) and sixfold (5% acetonitrile), respectively (Figure 2B). We speculate that the less polar acetone and acetonitrile co-solvents facilitate binding of the charged ABTS and thereby accelerate its conversion. Likewise, indole conversions were significantly affected by acetone and acetonitrile only at co-solvent concentrations above 10% (>50% decrease; Figure 2B). In summary, both acetone and acetonitrile may be applied at 10-20% concentrations without exceedingly large decreases in the enzymatic activities.

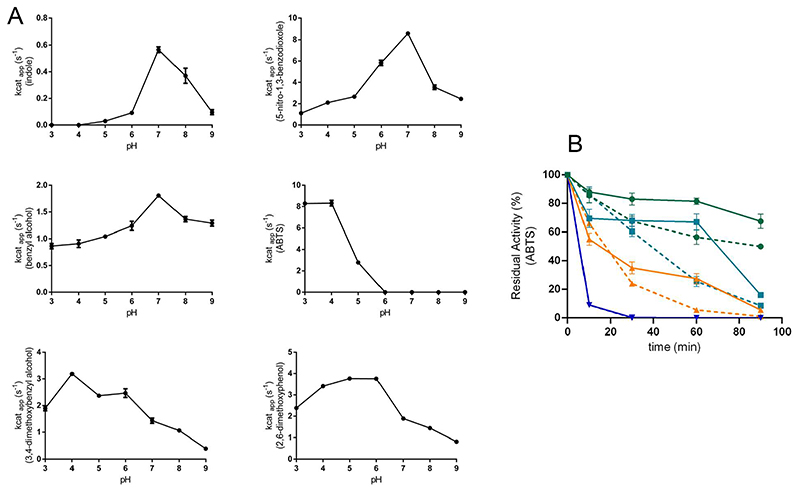

In addition to the sensitivity to the chemicals employed in bioconversions, critical factors are the pH and temperature. We found that HspUPO is optimally active at neutral pH with indole, 5-nitro-1,3-benzodioxole, and benzyl alcohol whereas more acidic pH values are optimal for the conversions of ABTS (pH 4), 3,4-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol (pH 4) and 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (pH 5) (Figure 3A). Such pronounced variations in the pH dependency have been observed before for other peroxidases and peroxygenases (35). We further probed the operational robustness of HspUPO by measuring the activity towards ABTS after incubation at increasing temperatures (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. pH activity profiles and thermal inactivation assay on purified HspUPO.

A) pH activity profiles. B) Thermal inactivation was evaluated using glycosylated (solid lines) and deglycosylated (dashed lines) HspUPO with ABTS as substrate (blue, 60 °C; orange 50 °C, cyan, 40 °C; green, 35 °C)

HspUPO was mostly inactivated after 20-30 minute exposures to temperatures higher than 50 °C. Conversely, HspUPO overall activity was minimally affected at 40 °C and only after 90 minutes the enzyme mostly lost activity. At the temperature of 35 °C, there was some activity loss only after 60 minutes but the enzyme remained mostly active even after longer incubations.

Recombinant HspUPO is a highly glycosylated protein with a sugar contribution of 28 kDa to the final molecular weight of 55 kDa (27 kDa the fully deglycosylated isoform). In light of this feature, it was of interest to understand if and how the glycosylations influence the enzyme properties. The enzymatically-generated deglycosylated HspUPO showed steady-state kinetics parameters practically identical to those measured with the native fully-glycosylated enzyme (Figure 1 and Figure S1). However, deglycosylation clearly proved to negatively impact on the resistance of the enzyme to thermal inactivation (Figure 3B). It is interesting to observe that deglycosylation had virtually no effect on the temperature of unfolding (Tm of 76 °C for both the native and deglycosylated enzymes). Thus, the protective and stabilizing role of glycosylation becomes manifested only upon long incubations and by probing the enzymatic activities rather than protein denaturation. Activities may sense multiple factors, such as the loss of the heme, and not only the global protein unfolding as interrogated by the thermal denaturation methods. In essence, protein glycosylations contribute to the operational robustness of the enzyme.

Biotransformations

To characterize the reaction potential of HspUPO, various substrates displaying a broad scope of functional groups were investigated under the optimal conditions as suggested by the above-described experiments (Table 3 and Supporting Information). Ethylbenzene 1a, a common test substrate for hydroxylation, was regioselectively C-H oxidized at the benzylic position to give the corresponding (R)-alcohol (R)-1b with 23% e.e. (Entry 1 in Table 3). In this reaction also the corresponding ketone, acetophenone 1c, was detected, indicating that HspUPO has also the potential to perform the oxidation of benzylic sec-alcohols. Indeed, when testing racemic phenylethanol rac-1b, the alcohol was oxidized with high efficiency giving exclusively the ketone product 1c with >99% conversion (Entry 2). The oxidation of 1a was also performed on a semi-preparative scale (20 mL) with increased substrate concentration (100 mM) yielding 210 mg of 1c (88% isolated yield, 92% GC-yield, TON=13143). Thus, HspUPO transforms both phenylethanol enantiomers efficiently. This is worth to be noted since the well-characterized Agrocybe aegerita UPO converts ethylbenzene to the secondary benzyl alcohols (ee values up to 99% and TON=10600) with only traces of α-ketones (48–49). The reactivity of HspUPO towards phenylethanol can be very attractive because biocatalysts oxidizing both enantiomers of a sec-alcohol are highly desired e.g. in the amination of sec-alcohols. In various studies, two stereo-complementary enzymes (mostly alcohol dehydrogenases) had to be employed to ensure the oxidation of both enantiomers (50–52); therefore, HspUPO may offer here an alternative.

Table 3. Biocatalytic oxidation of various chemical functionalities with purified HspUPO.

| Entry | Substrate | Conv.a [%] | TON | Productsb (relative amount in %) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxylation (main product) | 1 |

|

39 | 557 |

|

|

m/z = 136.0 1d (22) | ||

| Alcohol oxidation | 2 |

|

>99 | 1428 |

|

||||

| 3 |

|

79 | 1128 |

|

|

[M-H]+ = 321.06012 C15H13O8 2d (8) | [M-H]+ = 169.04930 C3H9O4 2f (7) | [M-H]+ = 183.06500 C9H11O4 2e (2) | |

| Epoxidation (main product) | 4 |

|

45 c | 642 |

|

|

|

||

| 5 |

|

>99 | 1428 |

|

|

||||

| 6 |

|

71 | 1014 |

|

|

||||

| Indole oxidation | 7 |

|

75-96 d | 1071-1371 |

|

|

[M-H]+ = 134.05 C8H8NO 6d (<1) | ||

Conversions are based on substrate recovery with the exception of 1a and 3a where the conversions are based on product formation due to volatility of the substrate. Reaction conditions are the following: substrate 10 mM, acetonitrile 5%, HspUPO 7 μM, H2O2 20 mM (2 eq, continuous addition), tricine buffer 100 mM pH 7.5, Vfinal = 1 mL, 30 °C, 500 rpm, 4 h (1h for 6a). All experiments performed in triplicates.

Product ratio is determined by peak area or calibration with commercial reference material on GC or HPLC.

For analysis of trace oxidation products (missing 15% in product ratio) see supporting information.

Conversion is displayed as a range since replicates deviate more than 10%.

The benzylic primary alcohol 2a (veratryl alcohol) was oxidized to the corresponding carboxylic acid 2c as the main product, whereby at the conditions employed also significant amounts of aldehyde were present (Entry 3). The structures of minor side-products formed were not elucidated. However, the masses indicate most likely demethylation of the substrate and dimerization. The ability of HspUPO to convert veratryl alcohol to the corresponding acid marks another substantial difference with Agrocybe aegerita UPO that mostly produces the aldehyde (48–49).

Turning to alkenes, cyclohexene 3a underwent epoxidation as the main reaction giving cyclohexene oxide 3b as the dominant product in the product mixture (69%, Entry 4). Additional products like the epoxy ketone 3d indicate that first C-H oxidation in the allylic position must have occurred prior to further oxidation. The oxidation of styrene 4a went to completion leading the corresponding (S)-epoxide (S)-4b (10% e.e.) as main product (91%, Entry 5). These numbers favorably compare with Agrocybe aegerita UPO that was reported to convert up to 71% styrene giving the epoxide with an ee of 7% and TON=7900 (48–49). Introducing a chloro-substituent in para-position of styrene (substrate 5a) resulted in a switch of the enantiomer formed in excess by HspUPO, thus giving the (R)-epoxide with moderate e.e. (30%, Entry 6).

Indole 6a can be considered as a substrate with high potential for application, since it is a precursor for indigo. HspUPO oxidized 6a to indigo 6b within only 1 h of incubation and conversions ranging from 75-96% (Entry 7). The synthesis of 6b was also performed on 20 mL scale with increased substrate concentration (20 mM) yielding 51 mg of isolated product (98%, TON=2813). A comparison with other reports (53) using unspecific peroxygenases shows that HspUPO is a very promising biocatalyst for indigo production. For instance, the enzymatic preparation of indigo has been described in two patents (54–55), whereby an unspecific peroxygenase from Humicola insolens was able to give 72.4% indigo formation based on limiting co-substrate H2O2 (2 mM) in a 100 mL reaction. HspUPO surpasses H. insolens UPO in terms of absolute indigo product concentration while also displaying lower byproduct formation. Nevertheless, it should be stated that the varying reaction set-ups and conditions make it difficult to reliably compare the productivity of these biocatalysts towards indigo production.

In summary, this first tapping of the potential of the catalyst clearly indicate that HspUPO can catalyze various reactions such as hydroxylation in benzylic position, alcohol oxidation and epoxidation with high efficiency. Side reactions indicate also the potential for hydroxylation in allylic position as well as demethylation.

Three-dimensional structure of HspUPO

Knowledge of the three-dimensional structure became of interest to gain further insight into the substrate and reactivity profile featured by HspUPO. Glycosylated proteins may be problematic for crystallization and HspUPO was no exception as no crystals were obtained with the native enzyme. The hurdle was overcome by crystallizing the deglycosylated protein which we found to be enzymatically active and sufficiently stable for biochemical analysis. Indeed, deglycosylated HspUPO (Figure S1) readily crystallized enabling the structure determination of several ligand complexes of the heme-bound holoenzyme. All the crystal structures were solved at high resolutions ranging from 1.3 Å to 2.5 Å (Table 4).

Table 4. Crystallographic statistics.

| HspUPO complex | Imidazole (7O1R) | 1-Phenylimidazole (7O1X) | S-1,2-propandiol (7O1Z) | MES (7O2D) | Styrene (7O2G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution range | 48.2 - 1.3 | 48.0 - 1.6 | 48.0- 1.8 | 29.8 - 2.6 | 52.6 - 2.1 |

| Space group | P41212 | P41212 | P41212 | P41212 | P41212 |

| Unit cell axes (Å) | 71.7 71.7 153.7 | 71.5 71.5 153.2 | 71.4 71.4 152.6 | 73.1 73.1 154.1 | 71.9 71.9 154.5 |

| Total reflectionsa | 2556180 (120423) | 687067 (35537) | 478559 (28188) | 325802 (42673) | 302461 (26523) |

| Unique reflectionsa | 9926 (4837) | 53428 (2629) | 37610 (2196) | 12383 (1603) | 23855 (1968) |

| Multiplicitya | 25.8 (25.0) | 12.9 (13.5) | 12.8 (12.7) | 26.3 (26.6) | 12.7 (13.5) |

| Completenessa (%) | 99.96 (99.85) | 99.96 (99.98) | 99.99 (100.00) | 99.8 (99.3) | 97.1 (99.8) |

| Mean I/sigma(I)a | 14.8 (0.8) | 11.5 (2.1) | 25.7 (5.8) | 22.5 (4.7) | 8.0 (0.5) |

| Wilson B-factor | 14.83 | 19.51 | 22.77 | 52.54 | 49.00 |

| R-mergea,b | 0.155 (4.6) | 0.159 (1.7) | 0.059 (0.40) | 0.13 (0.91) | 0.21 (5.42) |

| CC1/2a,c | 0.999 (0.44) | 0.999 (0.812) | 1.0 (0.963) | 0.999 (0.991) | 0.998 (0.379) |

| Reflections used in | 99151 (9737) | 53337 (5238) | 37532 (3665) | 12383 (1183) | 23783 (2365) |

| refinementa | |||||

| R-worka | 0.140 (0.309) | 0.134 (0.181) | 0.123 (0.151) | 0.200 (0.191) | 0.202 (0.413) |

| R-freea | 0.158 (0.353) | 0.159 (0.211) | 0.168 (0.223) | 0.255 (0.336) | 0.222 (0.465) |

| N. of non-hydrogen atoms | 2135 | 2108 | 2104 | 1879 | 1871 |

| macromolecules | 1814 | 1774 | 1804 | 1763 | 1757 |

| ligands | 99 | 103 | 105 | 112 | 84 |

| solvent | 222 | 231 | 195 | 4 | 30 |

| Protein residues | 227 | 224 | 225 | 228 | 227 |

| RMS (bonds) (A) | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.017 | 0.016 |

| RMS (angles) (°) | 2.20 | 2.05 | 2.09 | 2.08 | 1.96 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97.8 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 96.9 | 96.8 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 3.1 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.00 |

| Average B-factor | 19.46 | 22.65 | 26.68 | 64.17 | 55.35 |

| macromolecules | 18.02 | 21.11 | 25.16 | 62.95 | 55.26 |

| ligands | 24.05 | 27.55 | 38.96 | 84.03 | 59.56 |

| solvent | 29.12 | 32.25 | 34.14 | 45.07 | 48.34 |

Values in parentheses are for reflections in the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge=Σ|Ii-<I>|/ΣIi, where Ii is the intensity of ith observation and <I> is the mean intensity of the reflection.

The resolution cut-off was set to CC1/2’> 0.3 where CC1/2 is the Pearson correlation coefficient of two ‘half data sets, each derived by averaging half of the observations for a given reflection.

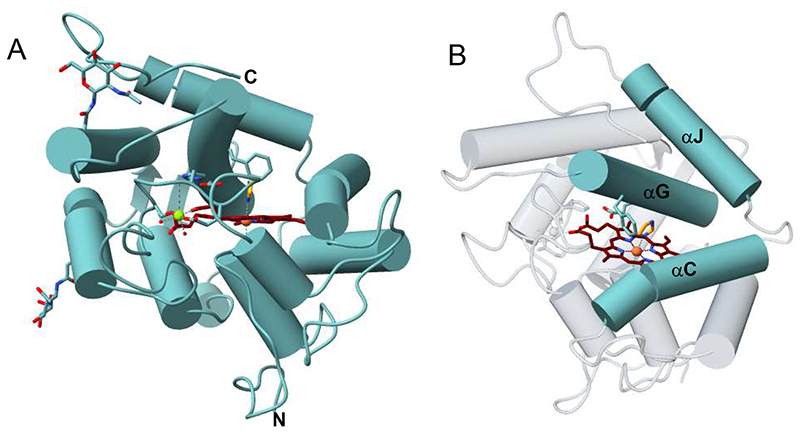

Overall, HspUPO can be described as a highly ordered and compact protein, whose many helices completely wrap the heme prosthetic group. In agreement with size-exclusion chromatography data (Figure S1), the analysis of the crystal packing indicates that the protein is monomeric. HspUPO three-dimensional structure comprises 10 α-helices and two short β-strands, which we labelled following the current literature (αA:40-48; αB:60-71; αC:75-88; αD:99-103; αE:129-138; αF:146-163; αG:171-188; αH:198-207; αI:212-214; β1:143-145; β2:195-197) (25). Two molecules of N-acetylglucosamine were found to be linked to Asn133 and Asn161 (Figure 4A-B). The N-terminal residues 1-24 form the signal peptide and were predicted to be cleaved during protein maturation process. Indeed, the first ordered amino acid is Ser25. A noticeable feature is the high degree of order displayed by the protein structure as a whole. All protein residues display clearly defined electron density. Only the C-terminal residues, spanning from 251 to 261, do not reveal any electron density owing to their flexible conformation.

Figure 4. Crystal structure of HspUPO in complex with imidazole.

A) Ribbon diagram of the overall conformation of HspUPO. Protein, heme carbon atoms, magnesium ion, and imidazole are colored respectively in cyan, maroon, lawn green, and orange. “N” and “C” outline the N- and C-termini. The C-terminal residues 251-261 are disordered. B) The α-helices αC, αG and αJ shape the active site.

The active site is a tube-shaped closed tunnel and is finely circumscribed by three α-helices (αC, αG, αJ) (Figure 4B and 5A). The iron atom of the heme sits at the dead-end of the tunnel. The prosthetic group is coordinated by the thiol side chain of Cys39, the axial ligand, and firmly anchored to the protein through extensive interactions. A heme propionate group is bound to a magnesium that is further coordinated by two side chains (Glu109 and Ser113), a backbone nitrogen (His110) and two water molecules, defining an octahedral coordination sphere (Figure 5B).

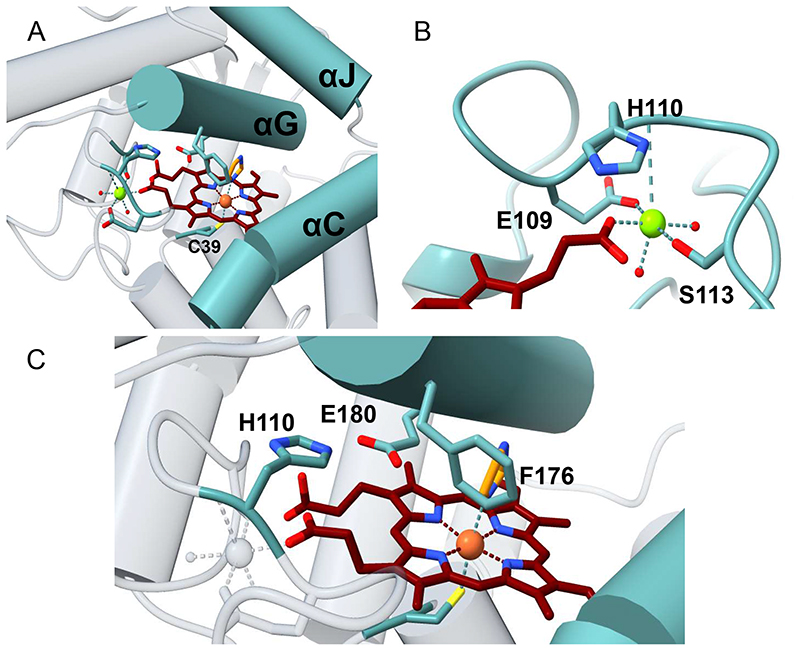

Figure 5. Close-up view of HspUPO active site.

A) The substrate-binding site is located at the bottom of a tunnel, lined by helices αJ, αG, and αC. B) A heme propionate group interacts with a magnesium ion that is coordinated by other three residues and two water molecules. C) His110, Glu180 and Phe176 protrude from the α-helix G and are positioned above the iron, providing critical elements for catalysis and substrate binding.

Further active site analysis portrays three core side chains, His110, Glu180 and Phe176, which protrude from the αG helix above the Fe center (Figure 5C). Phe176 provides a steric block that coordinates and channels the substrate towards the iron atom of the heme whereas the His110-Glu180 pair has been proposed to play a leading role in the catalytic cycle by promoting compound I formation (Scheme 1).

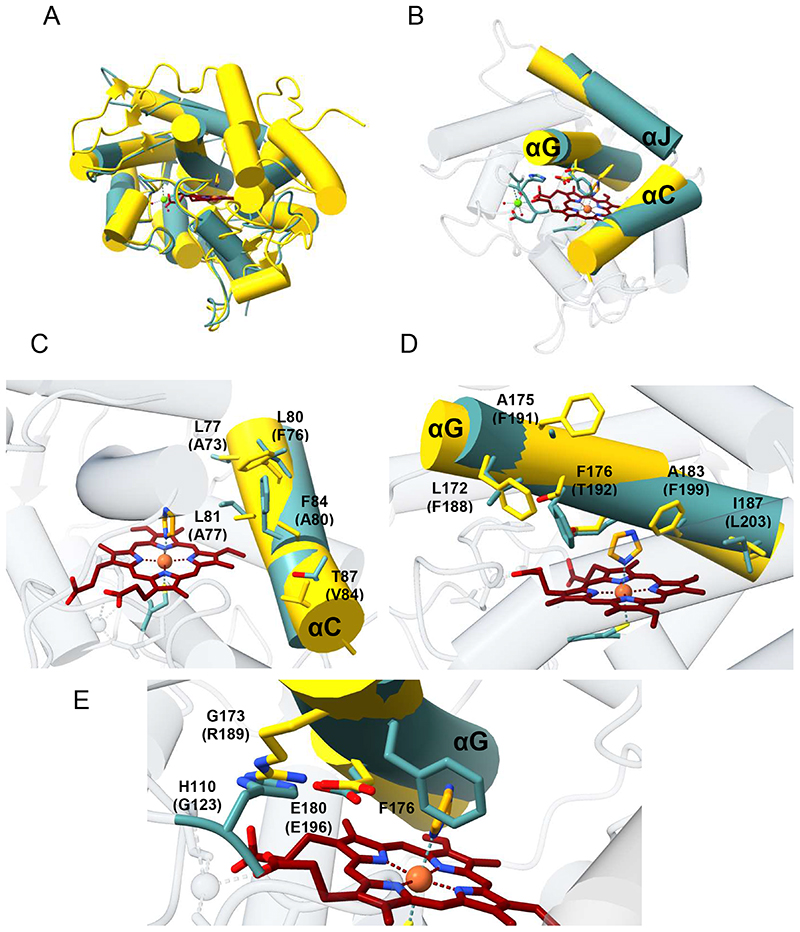

Based on sequence similarities, HspUPO belongs to the class I – so-called “short” – peroxygenases (56). Comparison of HspUPO with the structure of UPO from Agrocybe aegerita (25), a class II - long - peroxygenase, shows that the two enzymes share a similar overall structure, with a root-mean-square deviation of 2.1 Å for 201 Cα atoms (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Structural comparisons.

A) Pairwise superposition between HspUPO and UPO from Agrocybe aegerita (PDB ID: 2YOR), colored in cyan and yellow, respectively. The A. aegerita enzyme has a 70-residue extension that comprises three helices not present in HspUPO. B-E) The active sites of the two proteins differ due to re-orientations of the helices αC, αG, and αJ (B), coupled to various changes in the side chains that protrude from these helices. The amino acid labels of A. aegerita UPO are in brackets.

However, the comparison also reveals a few evident differences. The long (class II) A. aegerita UPO features a 70-residue α-helical C-terminal extension and a less compact structure compared to that of the short (class I) HspUPO. Moreover, the active-site shaping helices αC, αG, and αJ of HspUPO are shifted by about 3-4 Å and re-oriented by ~10° (Figure 6B). This re-arrangement is coupled to several amino acid replacements particularly on αC and αG. Though the hydrophobic nature of these amino acids is mostly conserved, the bulkiness of their side chains is not, as detailed in Figure 6C-D. This results in a generally narrower substrate-binding site in HspUPO. Another cluster of critical variations is found in the residues that directly surround the iron center above the heme. The catalytic acid-base pair (Arg189-Glu196) of A. aegerita UPO is replaced by Gly173 and Glu180 in HspUPO whereas Gly123 of A. aegerita UPO is replaced by His110 in HspUPO (Figure 6E). As a result of these amino acid replacements, the His110 side chain of HspUPO spatially overlaps on the Arg189 side chain of the A. aegerita structure. This observation validates the prediction that in the short (class I) UPOs, the catalytic role of “charge stabilizer” is played by a class I-specific conserved histidine (His110 in HspUPO) rather than by an arginine as found for the class II enzymes (Arg189 in A. aegerita UPO) (20). In summary, beside an identical fold and similar overall conformations, the two peroxygenases differ in the fine details of the active site and these differences can have far-reaching implications in the modulation of their substrate scopes. The narrow shape of the HspUPO site may well explain its preferences for aromatic substrates with small substituents as evidenced by our bioconversion experiments (Table 3).

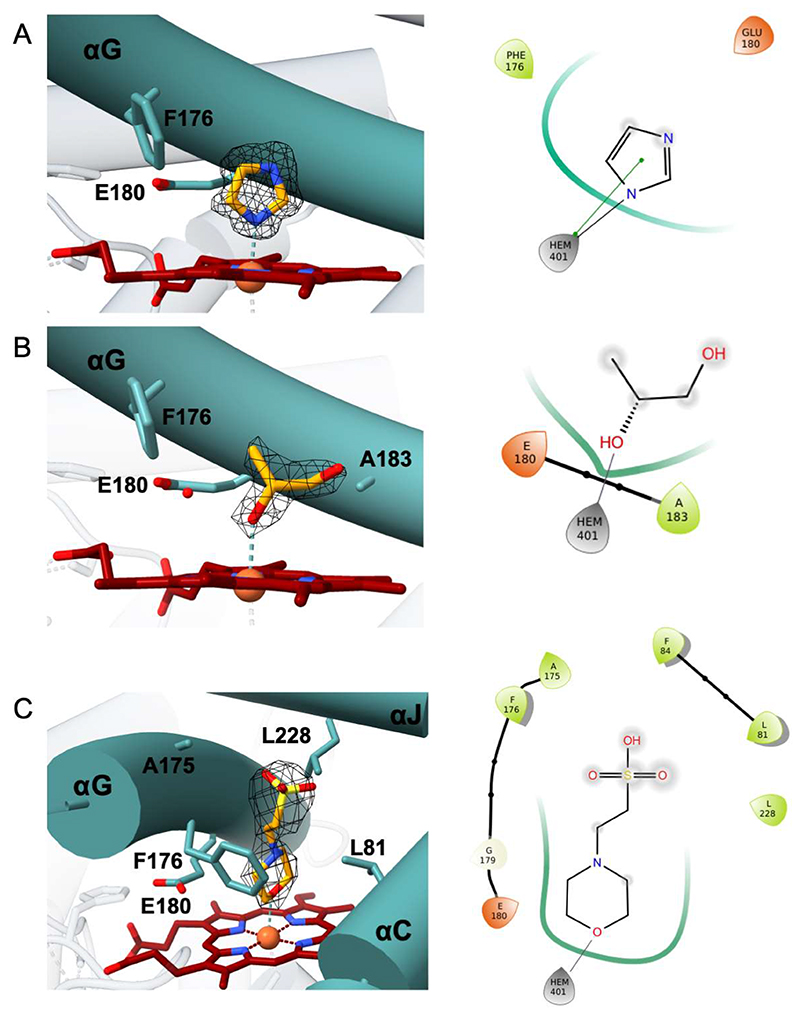

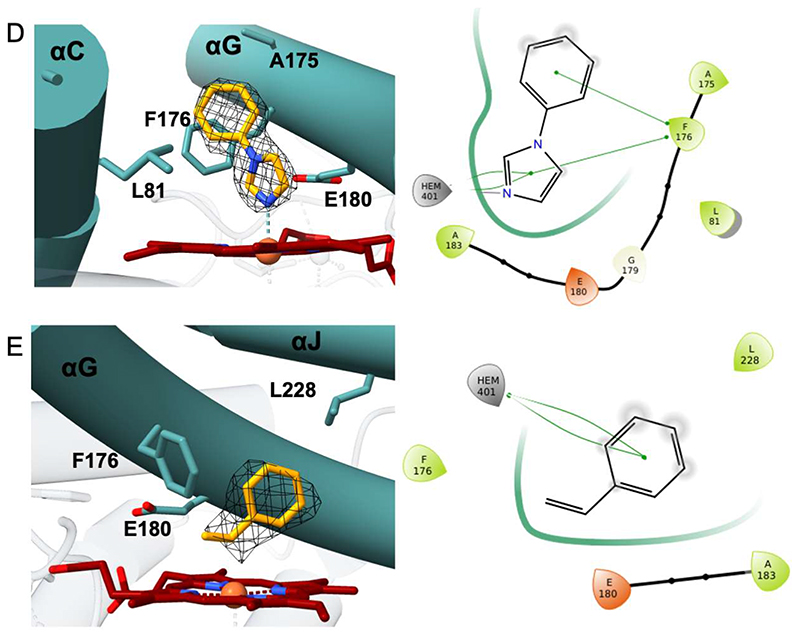

Different ligands and same protein conformation

The main aim of the structural analysis was to rationalize the substrate profile exhibited by HspUPO. Towards this aim, it was very helpful that crystals of deglycosylated HspUPO were found in many conditions and could be successfully used for data collection experiments. Inspection of the resulting electron densities revealed that various ligands were bound in proximity of the iron. Remarkably, the bulkiness and polarities of these ligands differ substantially, ranging from a small alcohol [(S)-1,2-propanediol)] to a small heterocycle (imidazole) to a larger molecule [MES; 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid]. In the crystal structure of the imidazole complex (Figure 7A), a ligand nitrogen directly coordinates the heme iron. Similarly, (S)-1,2-propanediol and MES bind to the heme through their hydroxyl and ether oxygens, respectively (Figure 7B-C). In light of the preference for aromatic substrates exhibited by HspUPO, we then decided to further investigate the ligand acceptance by considering aromatic ligands. We first took advantage of the propensity of heme to bind imidazole by conducting a soaking experiment with 1-phenylimidazole (Figure 7D), a double ring imidazole-substituted molecule. As with imidazole, 1-phenylimidazole was found to coordinate the iron center with its nitrogen. Moreover, its aromatic substituent interacts with Phe176 through an edge-to-face interaction whereby the two aromatic rings are oriented orthogonal to each other. We next solved the structure of the enzyme bound to styrene, possibly the most efficiently converted substrate (Table 3 and Figure 6E). Also in this case, the ligand sits on top of the heme with its ethyl side chain oriented towards the iron and the edge of its aromatic ring facing the edge of Phe176 side chain. This binding mode is similar to that previously found in Agrocybe aegerita UPO (25) and is fully compatible with catalysis leading to epoxidation styrene.

Figure 7. HspUPO active site in complex with A) imidazole, B) S-1,2-propanediol, C) MES, D) 1-phenylimidazole, E) styrene.

Left panels: Weighted 2Fo-Fc electron density contoured at 1.4 σ. Right panels: Two-dimensional schematic diagram of the interactions between ligands and the protein residues. Green line indicates Van der Waals contacts whereas grey line indicates metal coordination.

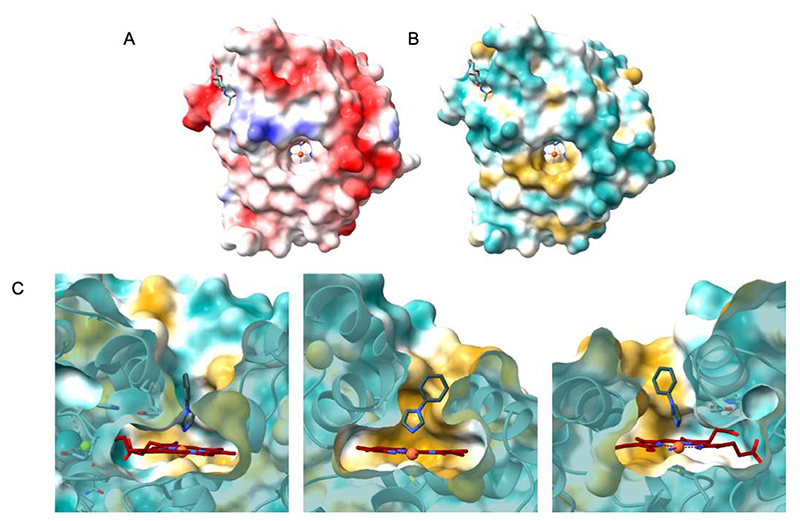

This set of enzyme-ligand structures corroborates the biotransformation experiments. All ligands are located in the same region at the bottom of the funnel-shaped tunnel leading to the heme in direct contact with the iron. The ligand-protein contacts comprise extensive van der Waals interactions involving the side chains that decorate the innermost segment of the tunnel. As shown by the 1,2-propanediol complex, HspUPO is able to bind alcohols as the hydroxyl group can orient itself towards the iron (Figure 7B). This is in line with the capacity of oxidizing several prim- and sec-alcohols (Entries 2-3 of Table 3). The structure with MES reveals how a cyclic aliphatic compound can bind in the active site providing a clue about the binding of a substrate such as cyclohexene that is efficiently oxidized by HspUPO (Entry 4 of Table 3). The binding of 1-phenylimidazole rationalizes the efficiency in indole conversion exhibited by HspUPO, as the two compounds have similar steric hindrance and comprise a heterocyclic ring. Together with 1-phenylimidazole complex, the structure with styrene shows how an aromatic ring can snugly fit at the bottom of the tunnel to establish several van der Waals interactions with the surrounding residues. A noticeable feature arising from these structural studies is that the binding of this rather diverse panel of ligands does not cause any conformational change in the active site. The only detectable variation is a slight, 0.1 Å, shift of Phe176 side chain upon binding of 1-phenylimidazole. Moreover, none of the ligands forms hydrogen-bond interactions with the surrounding protein groups as inspected with MAESTRO (57) (Figure 7). In the absence of highly specific interactions, the bound substrates are unlikely to be anchored in a tightly restrained single orientation. This feature may explain of the low stereo- and enantio-selectivities of the reactions as outlined by the conversions of alcohol and styrene compounds, respectively (Entries 2,5,6 of Table 3). Along these lines, it is interesting to notice that the surface of the tunnel has a double-face nature that can be appreciated by looking at Figure 8. Along the entire 12 Å path, one side of the tunnel surface is mostly hydrophobic and populated by aromatic and aliphatic side chains whereas the opposite side is more hydrophilic as it comprises hydrophilic side chains or main chain atoms Figure 8C). Such a fine partition is evident also at the tunnel opening where the side chains are arranged to form two hemi-circles. One is mostly hydrophobic whereas the other is more hydrophilic with a prevalence of positively charged groups (Figure 8A-B). With its bipartite nature and funnel shape, the active site of HspUPO seems perfectly tailored for dealing with substrates that are not exceedingly hydrophobic and bulky or require a precise constellation of hydrogen-bonding groups to enable their recognition.

Figure 8. HspUPO molecular surfaces.

A) Enzyme surface colored by electrostatic potential as calculated with Coulombic surface coloring in Chimera. Blue and red indicate, respectively, positively and negatively charged residues. B-C) Enzyme surface colored by molecular lipophilicity potential where cyan denotes hydrophilic residues and gold hydrophobic. Following the same color scheme, in image C is shown a close-up sliced view of the tunnel that brings to the active site cavity where it is buried the heme coordinated with 1-phenylimidazole, colored respectively in maroon and dark grey.

Conclusions

The increasing interest for UPOs stems from their ability to operate by using hydrogen peroxide only as co-substrate without the need electron donors or auxiliary electron-transporting subunits. After an initial testing of six candidates, the UPO from Hypoxylon sp. EC38 was identified as a suitable enzyme. HspUPO can be expressed with high yields as secreted recombinant protein using P. pastoris. In addition to the ease of expression and purification, HspUPO can stand widely used organic solvents such as acetone and acetonitrile. Moreover, the enzyme can easily operate at temperatures of 35 °C, although operational stability at high temperatures will probably need to be further improved. We further notice that HspUPO can sustain catalysis with relatively high mM concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. This is the critical feature that makes peroxygenases so attractive and distinguishes them from cytochrome P450s.

HspUPO is applicable for the transformation of various functional groups. Remarkably, HspUPO exhibits relatively low KM values, in the double-digit μM range, and yet we could not detect substrate inhibition in steady-state assays. These reactivities can be framed in the context of the three-dimensional structure. HspUPO displays a characteristic funnel-shaped tunnel that leads from the surface to the heme. The enzyme has a well-ordered overall structure and this type of rigid and compact conformation finds a counterpart in the absence of detectable conformational changes upon binding of diverse ligands. No specific hydrogen bonding interactions are found in any of the five enzyme-ligand complexes that have been crystallographically characterized. With a bipartite nature that provides hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups for interactions, the tunnel thereby functions as a molecular sieve, promoting the diffusion of small-to-medium sized substrates that can reach to and react with the oxoferryl (compound I) intermediate (Scheme 1). Oxygenation is therefore afforded by promoting the encounter between the activated oxygen of the oxoferryl and the substrate in the highly confined environment at the end of the catalytic tunnel, which is in line with the low KM values. Such a combination of a rigid and structurally well-defined protein scaffold with an initial portfolio of known substrates highlights HspUPO as a biocatalyst with high potential for the development of designer peroxygenases targeting specific substrates.

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information contains protein purification protocols, analytical methods, GC and HPLC traces.

Funding

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy (BMWFW), the Federal Ministry of Traffic, Innovation and Technology (bmvit), the Styrian Business Promotion Agency SFG, the Standortagentur Tirol, and the Government of Lower Austrian and Business Agency Vienna through the COMET-Funding Program managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG. Funding from the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR): Dipartimenti di Eccellenza Program (2018–2022) – Department of Biology and Biotechnology “L. Spallanzani” University of Pavia, is acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- UPO

unspecific peroxygenase

- HspUPO

Hypoxylon sp. UPO

- ABTS

2,2’-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt.

Footnotes

Author contributions: L.R. performed all activity measurements, purifications, kinetics, and crystallographic studies. C.R. performed the cloning and initial expression and screening experiments. A.S. performed the biotransformations. W.K., A.G. and A.M. designed and supervised the research. The manuscript was written with contributions from all authors.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in regards to this manuscript.

References

- [1].Newhouse T, Baran PS. If C-H Bonds Could Talk: Selective C-H Bond Oxidation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:3362–3374. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sheldon RA, Norton M. Green chemistry and the plastic pollution challenge: towards a circular economy. Green Chem. 2020;19:6310–6322. doi: 10.1039/D0GC02630A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sheldon RA, Woodley JM. Role of Biocatalysis in Sustainable Chemistry. Chem Rev. 2018;118:801–838. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Clomburg JM, Crumbley AM, Gonzalez R. Industrial biomanufacturing: The future of chemical production. Science. 2017;355 doi: 10.1126/science.aag0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li Z, van Beilen JB, Duetz WA, Schmid A, de Raadt A, Griengl H, Witholt B. Oxidative biotransformations using oxygenases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:136–144. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Montellano PRO. Hydrocarbon Hydroxylation by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Chem Rev. 2009;110:932–948. doi: 10.1021/cr9002193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Krest CM, Onderko EL, Yosca TH, Calixto JC, Karp RF, Livada J, Rittle J, Green MT. Reactive Intermediates in Cytochrome P450 Catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2013;228:17074–17081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.473108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Smith GCM, Tew DG, Wolf R. Dissection of NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase into distinct functional domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8710–8714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Holtmann D, Hollmann F. The Oxygen Dilemma: A Severe Challenge for the Application of Monooxygenases? ChemBioChem. 2016;17:1391–1398. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Holtmann D, Fraaije MW, Arends IW, Opperman DJ, Hollmann F. The taming of oxygen: biocatalytic oxyfunctionalisations. Chem Commun. 2014;50:13180–13200. doi: 10.1039/C3CC49747J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hilker I, Gutierrez MC, Furstoss R, Ward J, Wohlgemuth R, Alphand V. Preparative scale Baeyer-Villiger biooxidation at high concentration using recombinant Escherichia coli and in situ substrate feeding and product removal process. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:546–554. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hollmann F, Arends IWCE, Buehler K. Biocatalytic Redox Reactions for Organic Synthesis: Nonconventional Regeneration Methods. ChemCatChem. 2010;2:762–782. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201000069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mifsud M, Gargiulo S, Iborra S, Arends IWCE, Hollmann F, Corma A. Photobiocatalytic chemistry of oxidoreductases using water as the electron donor. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fujishiro T, Shoji O, Nagano S, Sugimoto H, Shiro Y, Watanabe Y. Crystal Structure of H2O2-dependent Cytochrome P450SPa with Its Bound Fatty Acid Substrate: insight into the regioselective hydroxylation of fatty acids at the a position. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29941–29950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Girvan HM, Poddar H, McLean KJ, Nelson DR, Hollywood KA, Levy CW, Leys D, Munro AW. Structural and catalytic properties of the peroxygenase P450 enzyme CYP152K6 from Bacillus methanolicus. J Inorg Biochem. 2018;188:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pickl M, Kurakin S, Cantú Reinhard FG, Schmid P, Pöcheim A, Winkler CK, Kroutil W, de Visser SP, Faber K. Mechanistic Studies of Fatty Acid Activation by CYP152 Peroxygenases Reveal Unexpected Desaturase Activity. ACS Catal. 2019;9:565–577. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b03733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yu D, Wang J-B, Reetz MT. Exploiting Designed Oxidase-Peroxygenase Mutual Benefit System for Asymmetric Cascade Reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:5655–5658. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b01939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dunham NP, Arnold FH. “Nature’s Machinery, Repurposed: Expanding the Repertoire of Iron-Dependent Oxygenases”. ACS Catal. 2020;10:12239–12255. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c03606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ullrich R, Nüske J, Scheibner K, Spantzel J, Hofrichter M. Novel Haloperoxidase from the Agaric Basidiomycete Agrocybe aegerita Oxidizes Aryl Alcohols and Aldehydes. Appl Envirom Microbiol. 2004;70:4575–4581. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4575-4581.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hofrichter M, Kellner H, Pecyna MJ, Ullrich R. Fungal unspecific peroxygenases: heme-thiolate proteins that combine peroxidase and cytochrome p450 properties. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;851:341–368. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-16009-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pullman P, Knorrscheidt A, Munch J, Palme PR, Hoehenwarter W, Marillonnet S, Alcalde M, Westermann B, Weissenborn MJ. A modular two yeast species secretion system for the production and preparative application of unspecific peroxygenases. Commun Biol. 2021;4:562. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02076-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gomez de Santos P, Cervantes FV, Tieves F, Plou FJ, Hollmann F, Alcalde M. Benchmarking of laboratory evolved unspecific peroxygenases for the synthesis of human drug metabolites. Tetrahedron. 2019;75:1827–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2019.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang Y, Lan D, Durrani R, Hollmann F. Peroxygenases en route to becoming dream catalysts. What are the opportunities and challenges? Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;37:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shoji O, Watanabe Y. Peroxygenase reactions catalyzed by cytochromes P450. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2014;19:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00775-014-1106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Piontek K, Strittmatter E, Ullrich R, Gröbe G, Pecyna MJ, Kluge M, Scheibner K, Hofrichter M, Plattner DA. Structural Basis of Substrate Conversion in a New Aromatic Peroxygenase: Cytochrome P450 functionality with benefits. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:34767–34776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ramirez-Escudero M, Molina-Espeja P, Gomez de Santos P, Hofrichter M, Sanz-Aparicio J, Alcalde M. Structural Insights into the Substrate Promiscuity of a Laboratory-Evolved Peroxygenase. ACS Chem Biol. 2018;13:3259–3268. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.8b00500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bordeaux M, Galarneau A, Drone J. Catalytic, Mild, and Selective Oxyfunctionalization of Linear Alkanes: Current Challenges. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10712–10723. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gutiérrez A, Babot ED, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M, Martínez AT, Del Río J. Regioselective oxygenation of fatty acids, fatty alcohols and other aliphatic compounds by a basidiomycete heme-thiolate peroxidase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;514:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kluge M, Ullrich R, Dolge C, Scheibner K, Hofrichter M. Hydroxylation of naphthalene by aromatic peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita proceeds via oxygen transfer from H2O2 and intermediary epoxidation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;81:1071–1076. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1704-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhang W, Li H, Younes HHS, Gòmez de Santos P, Tieves F, Grogan G, Pabst M, Alcalde M, Whitwood AC, Hollmann F. Biocatalytic Aromaticity-Breaking Epoxidation of Naphthalene and Nucleophilic Ring-Opening Reactions. ACS Catal. 2021;11:2644–2649. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c05588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Molina-Espeja P, Canellas M, Plou FJ, Hofrichter M, Lucas F, Guallar V, Alcalde M. “Synthesis of 1-Naphthol by a Natural Peroxygenase Engineered by Directed Evolution”. Chembiochem. 2016;17:341–349. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Karich A, Kluge M, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M. Benzene oxygenation and oxidation by the peroxygenase of Agrocybe aegerita. AMB Express. 2013;3 doi: 10.1186/2191-0855-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tonin F, Tieves F, Willot S, van Troost A, van Oosten R, Breestraat S, van Pelt S, Alcalde M, Hollmann F. Pilot-Scale “Production of Peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita”. Org Process Res Dev. 2021;25:1414–1418. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.1c00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kluge M, Ullrich R, Scheibner K, Hofrichter M. Stereoselective benzylic hydroxylation of alkylbenzenes and epoxidation of styrene derivatives catalyzed by the peroxygenase of Agrocybe aegerita. AMB Express. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/2191-0855-3-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Molina-Espeja P, Garcia-Ruiz E, Gonzalez-Perez D, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M, Alcalde M. Directed evolution of unspecific peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:3496–3507. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00490-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Molina-Espeja P, Ma S, Mate DM, Ludwig R, Alcalde M. Tandem-yeast expression system for engineering and producing unspecific peroxygenase. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2015;73:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pullmann P, Weissenborn MJ. Improving the Heterologous Production of Fungal Peroxygenases through an Episomal Pichia pastoris Promoter and Signal Peptide Shuffling System. ACS Synth Biol. 2021;10:1360–1372. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Carro J, Gonzalez-Benjumea A, Fernandez-Fueyo E, Aranda C, Guallar V, Gutierrez A, Martinez AT. Modulating Fatty Acid Epoxidation vs Hydroxylation in a Fungal Peroxygenase. ACS Catal. 2019;7:6234–6242. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b01454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Linde D, Olmedo A, Gonzalez-Benjumea A, Estévez M, Renau-Minguez C, Carro J, Fernandez-Fueyo E, Gutierrez A, Martinez AT. Two New Unspecific Peroxygenases from Heterologous Expression of Fungal Genes in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86 doi: 10.1128/AEM.02899-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Garrigós-Martínez J, Weninger A, Montesinos-Seguí JL, Schmid C, Valero F, Rinnofner C, Glieder A, Garcia-Ortega X. Scalable production and application of Pichia pastoris whole cell catalysts expressing human cytochrome P450 2C9. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20 doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01577-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kabsch W. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;66:133–144. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an Automated Program for Molecular Replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;30:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Murshudov GN, Vagin A, Lebedev A, Wilson KS, Dodson EJ. Effcient anisotropic refnement of macromolecular structures using FFT. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:247–255. doi: 10.1107/S090744499801405X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Holm L. Benchmarking fold detection by DaliLite v.5. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:5326–5327. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bormann S, Gomez-Baraibar A, Ni Y, Holtmann D, Hollmann F. Specific oxyfunctionalisations catalysed by peroxygenases: opportunities, challenges and solutions. Catal Sci Technol. 2015;4:2038–2052. doi: 10.1039/C4CY01477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kluge M, Ullrich R, Scheibner K, Hofrichter M. Stereoselective benzylic hydroxylation of alkylbenzenes and epoxidation of styrene derivatives catalyzed by the peroxygenase of Agrocybe aegerita. Green Chem. 2012;2 doi: 10.1039/C1GC16173C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wang H, Zheng Y-C, Chen F-F, Xu J-H, Yu H-L. Enantioselective Bioamination of Aromatic Alkanes Using Ammonia: A Multienzymatic Cascade Approach. ChemCatChem. 2020;12:2011–2082. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201902253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mutti FG, Knaus T, Scrutton N, Breuer M, Turner NJ. Conversion of alcohols to enantiopure amines through dual-enzyme hydrogen-borrowing cascades. Science. 2015;349:1525–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tian K, Li Z. A Simple Biosystem for the High-Yielding Cascade Conversion of Racemic Alcohols to Enantiopure Amines. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59:21745–21751. doi: 10.1002/anie.202009733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fabara AN, Fraaije MW. An overview of microbial indigo-forming enzymes. Appl Microbial Biotechnol. 2020;104:925–933. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10292-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kalum L, Lund H, Hofrichter M, Ullrich R. Enzymatic preparation of indigo dyes and intermediates. Patent WO2014122109A1. 2014

- [55].Tovborg M, Hofrichter M, Poraj-Kobielska M, Lund H. Enzymatic preparation of indigo dyes and in situ dyeing process. Patent WO2018002379A2. 2017

- [56].Kellner H, Luis P, Pecyna MJ, Barbi F, Kapturska D, Kruger D, Zak DR, Marmeisse R, Vadenbol M, Hofrichter M. Widespread occurrence of expressed fungal secretory peroxidases in forest soils. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bell JA, Cao Y, Gunn JR, Day T, Gallicchio E, Zhou Z, Levy R, Farid R. PrimeX and the Schrödinger computational chemistry suite of programs. International Tables for Crystallography. 2012 doi: 10.1107/97809553602060000864. F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.