Abstract

An evolutionary advantage of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) is their ability to bind a variety of folded proteins—a paradigm that is central to the nucleocytoplasmic transport mechanism, in which nuclear transport receptors mediate the translocation of various cargo through the nuclear pore complex by binding disordered phenylalanine–glycine-rich nucleoporins (FG-Nups). FG-Nups are highly dynamic, which poses a substantial problem when trying to determine precisely their function using common experimental approaches. FG-Nups have been studied under a variety of conditions, ranging from those that constitute single-molecule measurements to physiological concentrations at which they can form supramolecular structures. In this review, I describe the physicochemical properties of FG-Nups and compare them to those of other disordered systems, including well-studied IDPs. From this comparison, it is apparent that FG-Nups not only share some properties with IDPs in general but also possess unique characteristics that might be key to their central role in the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery.

Keywords: intrinsically disordered proteins, nucleocytoplasmic transport, protein folding and dynamics, phase separation, protein moonlighting

Introduction

The nuclear pore complex (NPC) is one of the largest molecular machineries in the cell. The NPC consists of a large set of proteins—the so-called “nucleoporins” (Nups)—each appearing in multiple copies. Figure 1 shows a typical electron microscopy (EM) view of the NPC. A notable feature of EM tomograms of the NPC is the appearance of a scaffold that forms a channel with a large hole (~30–40 nm) [1–3]. Proteins contributing in large part to the visible scaffold structure are referred to as scaffold Nups. For a detailed understanding of how scaffold Nups form the structured part and how this can anchor the NPC inside the double membrane of the nuclear envelope, the reader is referred to the review by von Appen and Beck et al. in this special issue [4]. However, the tomogram of the NPC (Fig. 1) also nicely demonstrates the difficulties encountered when well-established structure determination methods are used to study dynamic proteins because single-particle averaging techniques used in the generation of such data enhance well-structured features while conformationally dynamic elements are diluted out. In reality, the “large hole” (central channel) is filled with a dense mass of proteins at a concentration of around 1 mM; this constitutes the key functional architecture of the NPC—the permeability barrier. Those dynamic proteins contributing mainly to this “invisible” barrier are referred to as permeability barrier Nups, which are termed “FG-Nups” due to their enrichment in phenylalanine and glycine residues. The highly dynamic permeability barrier is permselective; that is, molecules smaller than approximately 40 kDa (~4 nm) can easily pass through it. Larger molecules typically bind to special nuclear transport receptors (NTRs) via nuclear localization or nuclear export signals, which can allow their bound cargo to be shuttled through the barrier (for reviews, see, e.g., Refs. [5] and [6]). Remarkably, cargo can be as large as preribosomal subunits or entire virus capsids, such as the hepatitis B capsid, which is approximately 39 nm in diameter [7]. The channel, together with the NTRs, forms the actual transport machinery. The direction of transport (import versus export) and release of the cargo are controlled by a RanGTP/ GDP gradient [8]. A comprehensive molecular understanding of both the FG-Nups and the NTRs, and how they act together, is essential for unraveling the mechanism by which the transport machinery functions. There exist several strategies to study the complexity of the nuclear transport machinery experimentally, of which three major ones are listed in the order of roughly increasing complexity of the system.

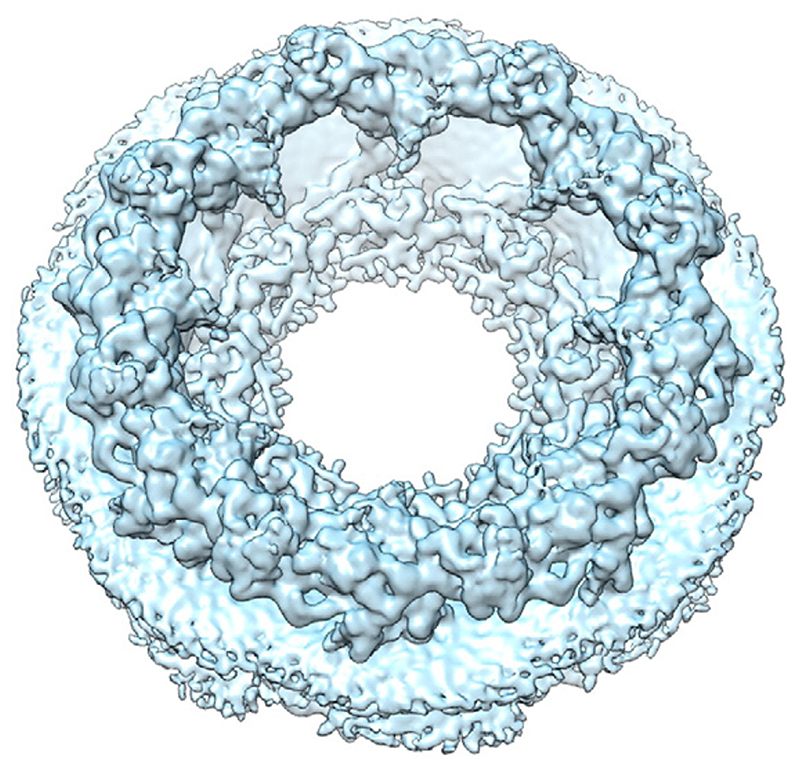

Fig. 1.

Top view of an EM tomogram of the human NPC, showing an empty channel, according to Ref. [3]. Disordered proteins that fill the channel are not visible to conventional structural biology approaches, and a hole with an approximate diameter of 41 nm is apparent.

-

(i)

Biochemical and biophysical experiments and analysis under controlled environments, such as studies performed on diluted proteins solutions, make major contributions in providing a solid understanding of the molecular aspects of nuclear transport. Although such studies do not necessarily take into account all aspects of the complexity of the NPC in living cells, they provide crucial fundamental information on how proteins can behave. Reviewing those experiments is the major focus of this article.

-

(ii)

An in vitro/reconstituted system that models the essential features of NPC function would be an ideal platform to study the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery at the molecular level. To that end, existing experimental approaches involve the nanofabrication of artificial channels with grafted permeability barriers or utilization of the intrinsic properties of barrier proteins to assemble into supramolecular structures. The reader is referred to those throughout the text.

-

(iii)

Studies on the cellular machinery help us to understand in detail the roles and functions of individual molecules. In particular, permeabilized-cell assays have been widely used in combination with single-particle tracking assays. The use of permeabilized-cell assays allows reconstitution of the soluble fraction of the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery. This allows convenient introduction of, for example, fluorescently labeled cargo, or NTRs, and it allows their passage through the NPC to be tracked. The resolution of contemporary techniques even enables the user to track single molecules, which can help to resolve individual steps during a single nuclear transport event.

In this review, I focus on describing experiments that fall largely into categories (i) and (ii), while in this special issue, Grunwald and Musser provide an excellent overview for studies in category (iii) [9]. Where possible, I have compared the findings on permeability barrier proteins to the known behavior of related proteins, to identify the characteristics that might be unique to permeability barrier Nups and those that might be common. It is clear that permeability barrier proteins are multifaceted biomolecules that exhibit dramatically different behavior under various conditions in different types of experiments and that there is still much to learn about even the basic properties of these proteins. Accordingly, interpretation of experimental results diverges among different research groups and has yielded a variety of models of how the permeability barrier is built in vivo and might function. These models are reviewed in detail, for example, in Ref. [10] and also by Grunwald and Musser in this issue [9].

This review is structured to cover the basic properties of permeability barrier Nups, as well as more complex aggregation and phase-separation behavior. Also discussed are the types of experiments that have been designed to reveal information about the interactions of permeability barrier Nups with NTRs under various conditions.

Basic properties of permeability barrier Nups (FG-domains)

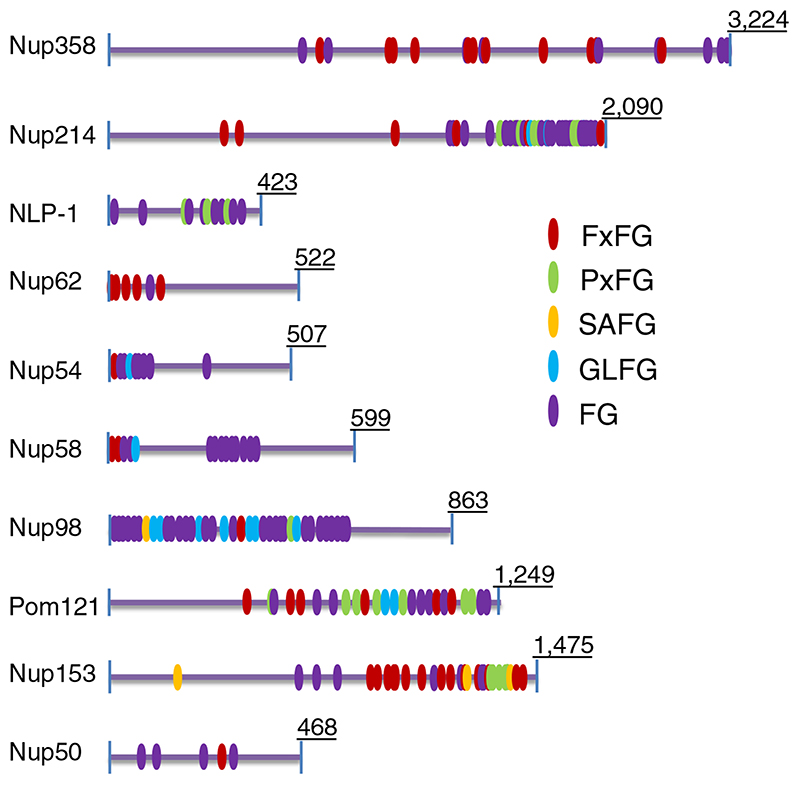

The most obvious feature of permeability barrier Nups is that phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats occur across the sequence, with a typical spacing of about 20 amino acids. Many of the neighboring residues of FG repeats do not seem to be coincidental, and many Nups have been further classified on that basis, for example, as FxFG-, GLFG-, PxFG-, and SxFG-repeat-rich Nups (where x is any amino acid). The long FG-rich regions are typically termed “FG-domains”, while the individual proteins might also have other domains that, for example, anchor them to the pore. Figure 2 shows an overview of mammalian permeability barrier Nups from which visual patterns of FG-rich sequences emerge. Unfortunately, comparative sequence analysis across many species reveals only limited conservation of FG-repeat domains [11]. The regions between FG repeats also do not appear to be particularly conserved, but are largely hydrophilic, and have large low-complexity regions, such as several serine residues in a row. Notably, a previous study involving a sequence analysis across several hundred species showed that the FG-domain of Nup98, despite having a similar mean hydrophobicity as many other proteins, possesses a substantially lower mean fraction of charged residues [12], pointing to a rather unique sequence space populated by Nup98 and potentially other FG-domains.

Fig. 2. Sequences of an assortment of disordered human FG-Nup according to UniProt, with different color-coded FG repeats.

FG-domains are disordered, similar to around half of the proteome

With such little sequence conservation, one might wonder what are the design rules behind FG-domain architecture and if there is anything other than the Phe residue and the neighboring Gly (these can certainly also be found in other proteins) that defines an FG-domain and gives rise to its specific function as an NPC permeability barrier protein. In 2001, Denning et al. reported experimental evidence that the FG-domains are intrinsically disordered domains [13,14]. This finding is established in the literature, and no doubts remain that the contributions to the actual permeability barrier are from disordered regions of the Nups. The FG-repeat region of an FG-Nup should be referred to as an intrinsically disordered domain in order to be accurate. For simplicity, and in the context of this review, I use the term “intrinsically disordered protein” (IDP) if referring to a large disordered protein or a large disordered domain.

By definition, an IDP is disordered in its native state and lacks stable secondary and tertiary structure [15]. It is useful to summarize some general features of IDPs in the context of what we know about FG-domains. IDPs are less frequently found in prokaryotic organisms, but it is estimated that 30–50% of the entire proteome is disordered in eukaryotes [16]. As not much is known about the disordered proteome, due to the limitations of conventional structural biology approaches, this can also be referred to as the “dark proteome”. A prominent feature of IDPs is that they lack a hydrophobic core that would seed a folding tendency—this can be predicted computationally and a number of computational tools exist that have been validated across larger sets of experimental data. Consequently, computational disorder predictors are largely considered to be reliable tools for identifying IDPs [17].

Disorder might have been enriched during evolution, as it provides a novel route for nature to achieve “moonlighting” of proteins, that is, to encode more than one functionality into a single biomolecule [18]. One can easily imagine that a “solid”, folded protein might possess a structure optimized for one or a few tasks but that it might be harder to repurpose it for another. An IDP, however, can be seen as an ensemble of several rapidly interconverting structures, none of which are sufficiently stabilized to dominantly populate the equilibrium. This can confer an amazing structural plasticity and diversity in terms of ability to bind interaction partners (see Refs. [19] and [20]), and some general key findings on IDPs are summarized as follows:

-

(i)

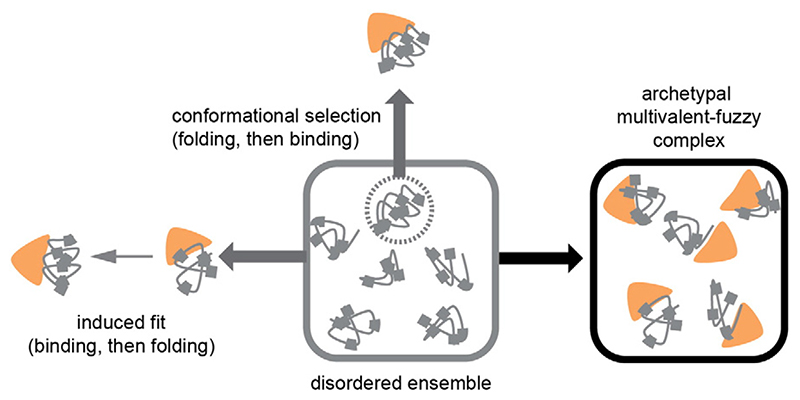

Folding upon binding: The classical concept, and arguably the most intuitive, is that folding is encoded in a binding partner; that is, the IDP folds into a specific structure upon binding, which reestablishes the classical structure-function paradigm [19]. Once structured, the “former” IDP can be more easily studied by using conventional structural biology approaches, and due to this effect, much of our IDP knowledge is biased in favor of understanding the folded state. If the IDP retains some of its disorder even in the bound state, the complex is typically termed “fuzzy” [16]. Figure 3 summarizes the two most common mechanisms of folding upon binding that have been observed experimentally. Later in this review, I discuss recent findings that show how FG-domain-NTR interactions behave with respect to these two mechanisms.

-

(ii)

Functional linkers: The spatial organization of proteins is a crucial factor for the functioning of more complex cellular machineries, and local protein concentration can have an impact on physiological mechanisms. Disordered regions can be used to link two folded domains and impart mechanical flexibility between them. Molecular machines can be tuned through the use of such linkers, for example, by changing the properties of the linker using posttranslational modifications. This has been well studied for ampholytic IDPs (those having both negative and positive charges). For example, a negatively charged region placed next to a positively charged one can facilitate loop formation to bring two folded domains into close proximity. The linker properties could be altered by phosphorylation, giving posttranslational modifications of disordered regions an important regulatory role. Such phenomena can sometimes be predicted computationally, which can greatly assist experimental research [21]. In the NPC, linker regions in Nups might have an important role in helping to assemble different domains in the scaffold structure [22], but to what extent FG-domains might function as linkers is still under speculation.

-

(iii)

Motif binding: IDPs often act through short linear motifs that facilitate binding interactions. In nucleocytoplasmic transport, the nuclear localization signal is one of the most widely known motifs and is a specific recognition sequence that targets cargo proteins to be recognized by import NTRs. Generally in biology, motifs are widely distributed, but the exact definition of a motif is certainly not clear, especially if the motif is very short. The eukaryotic linear motif database is a good starting point for identifying and learning about validated motifs [23] and does not list the FG sequence as a motif. As FG sequences also occur in proteins other than Nups, which is possible also by chance, it is still debatable under what conditions a Phe-Gly dipeptide should be considered a motif.

-

(iv)

Polymer view of IDP compactness/ expansion: Due to the lack of structure, for many IDPs, the importance of the amino acid sequence is not easily established. For example, it has been shown for disordered histone tails that sequence scrambling yields functional proteins in vivo if the overall amino acid composition is unchanged [24]. There is no strong evidence that the exact primary sequence of an FG-domain plays a major role, whereas in general, spacing of the FG repeats, the net charge, and the degree of low complexity are characteristics of an FG-domain sequence [11].

Fig. 3.

The different binding modes observed for IDP interactions (shown in gray, with valencies indicated by gray square markers) with folded proteins (orange). Due to their dynamics, IDPs populate a disordered ensemble in isolation [109]. In the “conformational selection” binding mode, the folded binding partner can bind to a specific conformation of the ensemble, which can also be a folded state. In the “induced-fit” binding mode, the presence of the binding partner induces folding of the IDP. For FG-domain-NTR interactions, it appears as if the native-state ensemble tends to bind to NTRs so that many conformations can readily engage with the NTR without requiring much time or energy. The result appears to be an archetypal, multivalent fuzzy complex that can form remarkably quickly (reprinted from ref. [46]).

Due to the lack of stable secondary structure, IDPs are frequently characterized in terms of their expansion in solution. This parameter—borrowed from polymer physics and defined as the radius of gyration, the end-to-end distance, or the hydrodynamic radius [25]—might have several implications for protein function in general [26,27]. For example, it has been shown for many IDPs that transient intramolecular forces can contribute to a somewhat collapsed behavior state of a protein in solution [28–30]. On a microscopic level, or if protein concentration is increased, intramolecular forces can give rise to intermolecular interactions that lead to, for example, various aggregation phenotypes (as discussed below). A systematic study of yeast FG-domains has indicated that they can be roughly assigned to one of two categories based on their hydrodynamic radius, which might have implications for their ability to form supramolecular assemblies (Ref. [27]; see also the section on phase separation, below).

Interactions between FG-Nups and NTRs

That FG-domains bind NTRs is well established [31–36]. Many NTRs have an importin-like fold, which are large superhelical proteins composed of multiple α-helical repeats. Onto many NTRs, one or more FG-binding sites have been experimentally mapped [34,37–43]. One confounding experimental observation is that nuclear transport is fast but specific. NTRs face a massive concentration of FG repeats when passing the barrier that is at least 30 nm thick, and the entire transport process is typically complete within approximately 5 ms [44,45]. Paradoxically, many FG-domains appear to have a high, sometimes even, nanomolar affinity to bind to FG-domains, when studied in solution. However, this cannot be explained easily using the simple kinetic principle that K D = k off/k on, as most experimentally observed k on values for binary complex formation are around 106 M−1 s−1. If K D = 100 nM, this would translate into an unrealistic k off value of 0.1 s−1 (so much less than one dissociation event during a single transport being possible).

A solution to this was found using a recent integrative structural biology approach [46], in which various single-molecule and ensemble spectroscopic techniques as well as computer simulations were used to analyze the formation of complexes between NTRs and FG-domains in detail. For the common folding-upon-binding interactions, a period of time is required for the two binding partners to orient themselves such that a collision event actually results in a binding event. Strong electrostatics between oppositely charged molecules can assist this orientation and facilitate attraction to achieve very fast on-rates [47]. Remarkably, observed FG-domain–NTR complex formation was found to approach the theoretical Einstein-Smoluchowski diffusion limit of around 109 M−1 s−1 even under electrostatic shielding conditions, which is usually only valid in the limited case involving the random diffusion and collision of two perfectly reactive spheres, for which every encounter counts as a binding event. It was found that the highly dynamic FG-domain presents an ultrareactive surface to the NTRs, as many Phe residues—despite being hydrophobic—are readily available and exposed on the surface to engage in multivalent binding with the NTR. The side chain of an exposed single Phe residue can engage in an approximately millimolar-affinity binding event with the NTR, in agreement with a previous computationally derived model [35], which, due to multivalency, translates into strong binding for entire FG-Nup-NTR complexes. Consequently, no large-scale conformational changes are necessary to facilitate binding, and in assays probing the expansion and dynamics of the FG-domain, no change was observed, whether bound or unbound.

Together, these effects easily explain how several hundred binding and unbinding events can occur during a 5-ms transport cycle; these give rise to a cumulative proofreading effect that specifically enables NTRs to pass the FG-filled NPC conduit [46]. The observed ultrafast binding mechanism can also explain various experimental observations on how NTRs interact with FG-domain hydrogels and with surface-grafted FG-domains, as discussed below.

Figure 3 shows a summary of the experimentally determined binding mechanism (also with respect to other common binding mechanisms for IDPs), which was observed for a large variety of FG-domain-NTR complexes, thus substantiating the generality of the mechanism [46]. Even NTF2, which has a β-sheet-rich fold completely different to those of importins, was found to adopt a similar mechanism of binding. Despite the generality of this binding mode, a systematic advanced fluorescence study also showed that the FG-repeat type of an FG-Nup can confer a preferential ability of that region to bind different NTRs [48] and, for example, NTF2 is known to preferentially bind FxFG motifs [49,50]. Whereas binding affinity between FG-domains and NTRs likely contributes little to the directionality of transport, it might be a factor in the organization of the spatial segregation of transport routes. As FG-domains are roughly aligned radially symmetrically due to the 8-fold rotational symmetry of the NPC, one could speculate that NTRs have differential affinities that translate into a preference on where to enter the barrier.

As IDPs have a high potential for interacting with a variety of binding partners, it is not surprising that FG-domains are involved in many other cellular mechanisms and have likely many more interaction partners than only NTRs (for a review, see Ref. [51]). More recently, several roles for FG-Nups, potentially unrelated to NPCs but instead associated with epigenetic regulation and transcription mechanisms, have been found. However, we currently lack a detailed understanding on how these proteins moonlight in other mechanisms involving diverse complexes, and the reader is advised to refer to excellent literature articles on these topics [52–57].

The ability of FG-domains to phase separate

Many protein solutions can undergo various types of phase separation, such as the widely known liquid–solid phase separation during a crystallization process. In this section, I review experiments in which the formation of FG-domain assemblies was observed and point to similarities and differences with other common IDP assembly pathways.

Fibril formation of FG-domains

Amyloid fibers are well known for their roles in a number of neurodegenerative diseases [58]. Amyloid structures arise from stacked β-sheets, which are typically thermodynamically stable, and are one of the most abundant supramolecular structures proteins can form. Amyloid formation is a pathway by which proteins can bury their hydrophobic residues [59] if, for any reason, they cannot fold into their native structure or if they are IDPs that “misfold”. Consequently, almost all folded or disordered proteins can form amyloids under certain conditions [60]. IDPs are particularly prone to being trapped along an amyloid-forming pathway, as is the case for α-synuclein, tau, the yeast prion Sup35, and polyQ-containing proteins. These proteins are all disorder-rich and are known to have the propensity to form amyloid structures. Many are infamous for their involvement in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington’s diseases [61]. However, amyloids are not necessarily dysfunctional in vivo, one of the most famous examples being the yeast prion Sup35 [62]. Amyloid formation of Sup35 can function as translational regulation and can confer an advantage to the yeast under certain stress conditions [63].

Several studies have shown that, at higher concentrations, FG-domains can aggregate into amyloid-like structures [64] or form even entire amyloid fibers [62,65,66]. However, whether the amyloid fiber phenotype of FG-domains is physiologically relevant is unknown. Under certain conditions, FG-domains might even be particularly prone to form amyloids [66]; therefore, it is important to ask how cells prevent a protein from entering this aggregation pathway, and several possibilities exist. It was previously shown in the test tube that NTRs can inhibit the formation of the FG-domain aggregation phenotype, likely by acting as a chaperone [66]. As NTRs are also abundant proteins in the cell, this presents a potential mechanism for the cell to control potential FG-domain aggregation pathways. From studies on other IDPs, it is known that posttranslational modifications can also alter aggregation tendency [67]. Also, cases are known in which mixtures of proteins—on their own aggregation-prone—actually suppress aggregation [68,69]. At present, it is completely speculative to estimate the extent to which such aggregation-inhibiting mechanisms exist under physiological conditions for the NPC, but FG-domains are subject to various posttranslational modifications, and the NPC itself is a mixture of different types of FG-domains. Furthermore, the protein homeostasis pathway is a major mechanism for clearing the cell of unwanted aggregates [70].

The ability of FG-domains to form supramolecular hydrogels

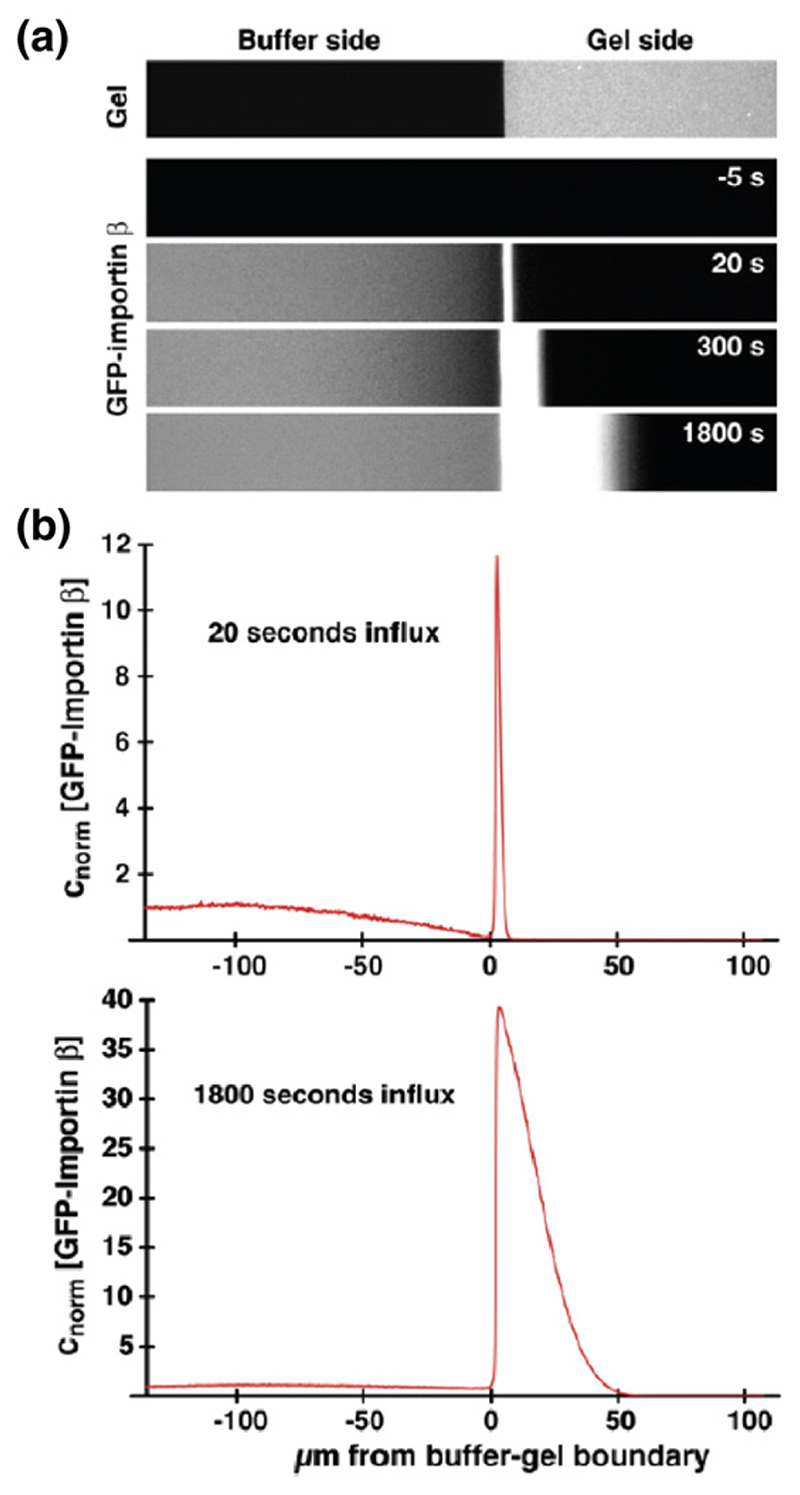

An important finding in the NPC field was that FG-domains can form hydrogels. If lyophilized FG-domains are rapidly shifted to physiological conditions at high concentration [71–73], mechanically stiff hydrogels can form. These gels can display NPC-like permeability barrier properties; that is, larger transport-incompetent protein cargo complexes are excluded from the gel, whereas NTRs can rapidly enter the gel, even when bound to cargo molecules. In fact, the gel functions as a sink for NTRs, and entry into the gel is so rapid that even an NTR depletion zone can become visible in front of the gel (Fig. 4). This macroscopic observation is consistent with the ultrafast mode of binding and the observed almost diffusion-limited in vitro kinetics described above (and summarized in Fig. 3).

Fig. 4. An experiment to demonstrate how NTRs in solution can rapidly penetrate FG-domain hydrogels.

(a) The interface between an FG-domain hydrogel and a buffer solution. Once a fluorescent NTR (importin-β) was added to the buffer solution outside the gel, the NTR rapidly enriched in the gel boundary. (b) Intensity profiles corresponding to the images in (a), from which it is apparent that a depletion zone exists in at the buffer-gel interface. Adapted from Ref. [71] with permission from Elsevier.

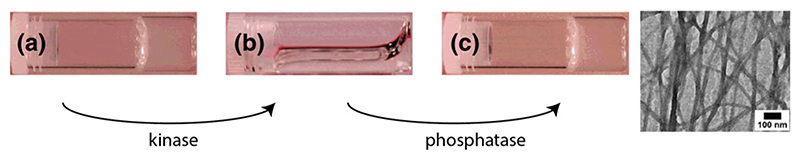

Due to the remarkable NPC-like properties of these hydrogels to function as a selective phase for NTRs [72], it is fascinating to speculate how such gels could be formed under physiological conditions. One such pathway can be borrowed from related disciplines. In the field of material science, hydrogels are widely known, and even simple peptide-based gels exist. For example, a classical “hydrogelator motif” is an FFGEY peptide. This peptide is capped at the N terminus with a naphthyl (NAP) group, which helps in wetting of the peptide to facilitate solubility and hydrogel formation [74]. This peptide has been designed to be switched under physiological conditions from the liquid to the tough gel-like state in a reversible manner using kinases and phosphatases, which phosphorylate and dephosphorylate the Tyr residue, respectively. As summarized in Fig. 5, the dephosphorylated NAP-FFGEY peptide forms a tough gel, whereas the phosphorylated form gives a clear solution. This system is a brilliant visual demonstration of enzymatic/posttranslational modification-mediated switching between gel and solution phase using a minimal system. Such “designer” physiological switching conditions could certainly form the basis for explaining how hydrogels form in the cell, especially as phosphorylation is a common cellular control mechanism.

Fig. 5.

An FFGEY peptide gel can be switched from a tough hydrogel-like state (a) to a liquid-like state (b) using a kinase and a phosphatase, as demonstrated by Yang et al. [74]. The right-hand panel shows that the gel has a fibrillar ultrastructure as observed by EM, which gives rise to a mechanically stable gel. If the FFGEY peptide is phosphorylated at the Tyr residue by a kinase, the solution is a liquid. If dephosphorylated by action of a phosphatase, an amyloid fiber network forms to a tough gel (a and c). The process is reversible and can be controlled by the addition of a phosphatase or kinase. Adapted with permission from Ref. [74], Copyright (2006) American Chemical Society.

The FFGEY-based hydrogels have been extensively studied from a structural perspective to understand the origins of their mechanical stability. Indeed, EM studies, which are routinely used to characterize the ultrastructure of hydrogels, have demonstrated that the FFGEY peptide gel is made from amyloid-type β-sheet-rich fibers (Fig. 5), and the degree to which the fibers intertwine influences the toughness of the gel [74].

Other “assemblages”

Phase separation of biomacromolecular solutions into liquid-like states has been recognized as an important mechanism in cell biology to form transient organelles that are not surrounded by membranes [75,76]. This can lead to local “assemblages” that can perform, or act as a template for, specific functions that isolated or dilute species would not be able to (e.g., see Refs. [77–80]). From a molecular standpoint, such phase separation represents a perfect balance of protein-protein versus protein-solvent interactions. One mechanism for controlling phase separation from a protein solution was recently shown by the Rosen laboratory [81], who showed that polyvalency can be an important factor, such that a higher-order aggregate can be formed.

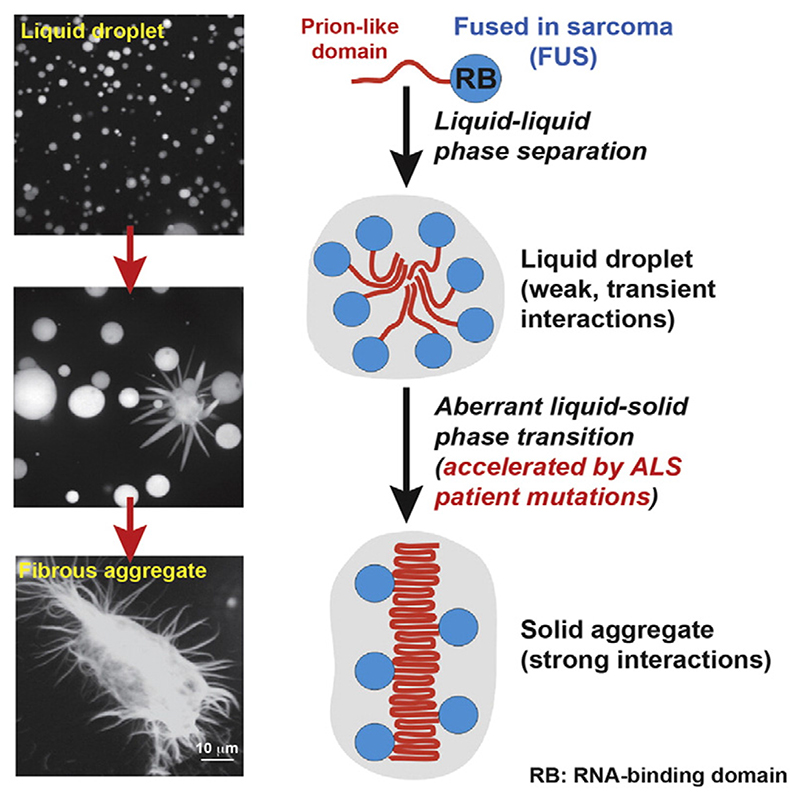

A particularly well studied phase-separating system is the IDP “fused in sarcoma” (FUS), consideration of which will help to explain the overall complexity of phase separation and to define the terms liquid–liquid, liquid-gel, and liquid-solid phase separation for the purpose of a further discussion on FG-domains. Figure 6 summarizes some existing knowledge about FUS assemblages. The FUS protein can exist stably as a homogenous protein solution, as well as undergo liquid-liquid phase separation to droplets, if, for example, 10 μM FUS is mixed with a 10% dextran solution [78]. These droplets are highly dynamic, which can be demonstrated by bleaching only half a droplet formed from fluorescent FUS assemblages; that half then undergoes fast recovery after photo-bleaching due to the high protein dynamics within the droplet (Fig. 7). Also owing to the liquid-like state, these droplets acquire a spherical shape, and they can also fuse with each other to coalesce into larger assemblages. At a very high concentration (500 μM), FUS was shown to assemble into tough hydrogels, which appear more rigid and can also have nonspherical shape, likely due to there being more, and thus cumulatively stronger, interactions within the gel [78]. Notably, it was also observed that, under certain conditions (in particular with certain disease-relevant mutations), FUS droplets can also be metastable and further convert (age) into fibrillar, amyloid-rich structures [78]. In order to demarcate the two end states (gel and fiber), the hydrogel-forming phase separation is referred to as a liquid-gel transition and the liquid-to-fiber transition as a liquid-solid transition.

Fig. 6.

Cartoon of the pathway by which FUS can undergo various phase transitions to form different assemblies. FUS can undergo liquid–liquid phase separation into droplets. Under certain conditions, these droplets can further age and undergo a liquid–solid phase transition into a fibrillar amyloid-like structure. Reprinted from Ref. [78] with permission from Elsevier.

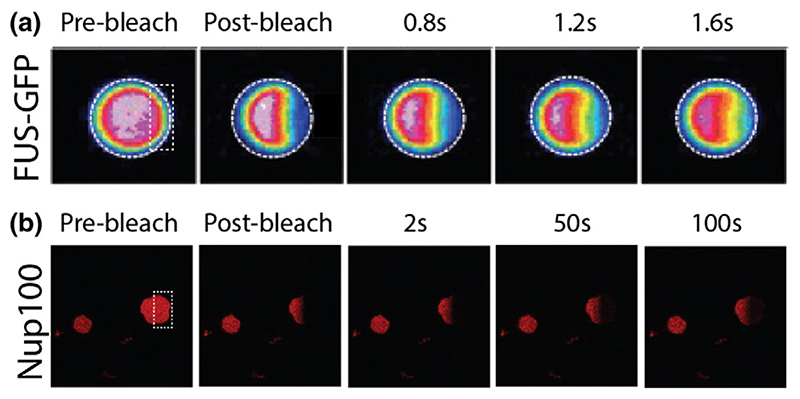

Fig. 7. Half-bleach experiments of phase-separated FUS and FG-Nup100 assemblages (droplets).

(a) Droplets were formed from GFP-labeled FUS, and then only the right-hand half of a droplet was bleached. The fluorescence recovered rapidly (blue to red indicating increasing fluorescence intensity), which points to the droplet being dynamic (liquid-like), and is the result of a liquid-liquid phase separation. (b) A similar half-bleach experiment from a different study for FG-Nup100 (doped with FG-Nup100 labeled with a synthetic fluorophore, shown in red). The droplets appear rigid, which points to the existence of a liquid-gel phase separation. Reprinted from Refs. [78] with permission from Elsevier and [12], respectively.

As mentioned above, FG-domains have also been found to form hydrogels, and some of those—but by no means all—have been also shown to contain a fibrillar phenotype [66]. As the experiments with FUS demonstrated, nonfibrillar gels and liquid droplets can be formed from the same protein under different conditions (high and low concentrations of FUS, respectively). It is thus likely that nonfibrillar FG-domain gel types exist and that only small differences in experimental conditions can yield different supramolecular phenotypes. Remarkably, it was recently shown that concentrated FG-domain solutions can also undergo phase separation simply by their dilution in physiological buffer [12]. Half-bleach experiments show that the resulting droplet structures (which were not necessarily spherical) are neither dynamic nor liquid-like (Fig. 7), which is indicative of a liquid-gel transition. Notably, these gel droplets also show NPC-like permeability properties.

Consistent with multivalency being a driving force for phase separation, it was recently discovered that mixtures of FG-domains and NTRs can also undergo phase separation [82]. In those assemblages, NTRs might function as crosslinks between FG-domains and are thus molecularly different from the aforementioned FG-domain gels, which form in the absence of NTRs.

As the cellular milieu itself can tune the properties of FG-domains and FG-NTR interactions [32,36], systematic comparison of FG-domain behavior in different environments will further foster our understanding of FG-domain interaction propensity [32,36].

The ability of FG-domains to form supramolecular brushes and films

As mentioned above, polymer theory has provided an impressive description of the dynamics of many IDP-like complex biomolecules in solution. It continues to be refined and will be developed into an even better predictive tool in the future [20]. Certain polymers have the ability to form brushes, with polyethylene glycol (PEG) brushes being the most common to passivate surfaces [83,84]. As with any polymer dissolved in water, a hydration shell surrounds the individual PEG molecules in solution. As PEG is also chemically inert toward itself, it is easy to imagine what happens if different PEG molecules are grafted close together: they will form a brush-like structure. One can expect that most “nonsticky” biopolymers will form brushes if forced together through grafting closer than their excluded volume (in simple terms: their size) [25]. That certain FG-domains can do the same was shown in 2007 by Lim et al. [85], and it was speculated that the channel is filled with FG-domains in a brushlike state. Clearly, a brush is an extreme state and is highly dependent on grafting density and also on the inertness/stickiness/cohesiveness of the molecules. Any form of intermolecular or intramolecular force can contribute to condensation of the brush. Condensation by noncovalent crosslinks can yield a thin film with, for example, gel-like properties, and experimental evidence that supports such behavior also for FG-domains exists [86]. As many FG-domains exist, it is credible that a large spectrum of states can result from surface grafting. These states range from being more brush-like to rather more like a film. It was also suggested that a larger expansion in solution of FG-domains might correlate with their tendency to form brushes when surface grafted while those that are more collapsed in solution might have a higher tendency to form gel-like states [27]. However, up to now, objective parameters to define the point at which a brush begins to condense and at which a thin gel film is reached are not easy to determine [86–90].

An important question to address is what happens to a brush or film when NTRs are present, as this could provide insights on how the barrier might be formed and/or function in vivo. NTRs such as importin-β have multiple FG-binding sites [39,42], and many FG-domains have more than 20 FG sites. It is thus a highly polyvalent system. Even if the interactions involved are only transient, NTRs can either trigger condensation or explore space between FG-domains that, for example, was occupied by water. Again, different effects of NTRs on densely grafted layers have been observed, ranging from decrease and nonchange to increase in layer/brush/ film height [86–90]. Due to the complexity of the brush/layer/film system, divergence between different studies, and thus also different interpretations, likely results from the different samples and methods used and the existence of a gradient of properties, which are not trivial to categorize.

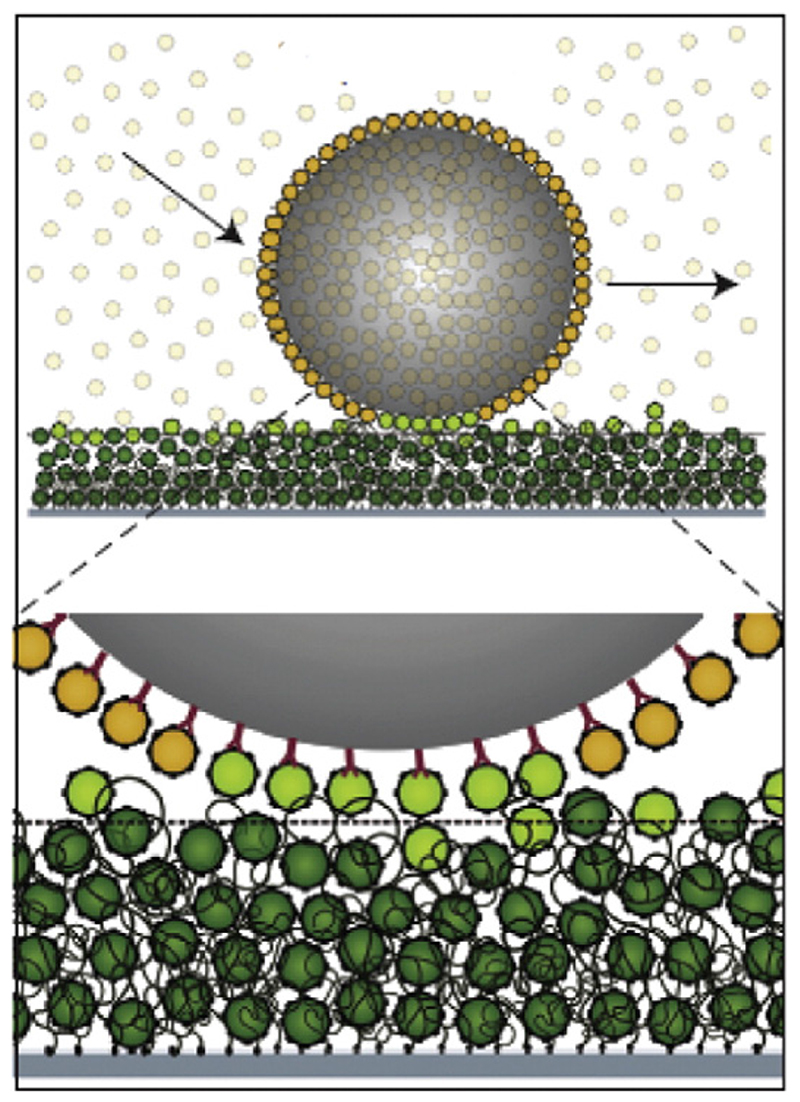

In this context, a fascinating experiment was performed by Schleicher et al. [91], in which an FG-domain layer was soaked in a solution of NTRs, and large beads were coated with these receptors (Fig. 8). Notably, the beads began a two-dimensional random walk on the surface. This macroscopic observation can again be explained by the ultrafast binding mode illustrated in Fig. 3 because, due to the rapid kinetics, individual FG-NTR bonds can be broken and reformed at little-to-no energetic cost. Due to multivalency, the bead sticks to the surface, where it can easily perform a basically unhindered two-dimensional random walk.

Fig. 8.

An experiment in which large beads were coated with NTRs. When these were placed on a layer of densely grafted FG-domains soaked in a solution of NTRs (small spheres in different green and light yellow colors), the beads were able to diffuse on the surface. Adapted with permission from Ref. [91].

A few experiments have also been performed to attempt to bring the grafting concept to three-dimensional models, to make artificial NPC mimics, and indeed, even FG-domain-grafted nanopores can show features of NPC-like permeability barriers with respect to facilitated passage of NTRs [32,92]. Analogous to the functional NPC, due to the small size of the artificial pore, it cannot always be easily assessed if the pore is filled, for example, with a brush, NTR-soaked film, or gel-like layer. However, simple artificial model systems will certainly facilitate the study of understanding the molecular architecture of such a barrier.

Conclusion

FG-domains are multivalent polymers, and much of their potential behavior can be anticipated from knowledge of other biological systems or even other disciplines, such as material science and polymer theory. Based on the diverse experimental results, various models have been generated to suggest how the physiological NPC might function such as the selective phase, the brush, virtual gate, the reduction of dimensionality and the karyopherin centric model, and so on, as well as mixtures of those [27,71,82,85,86,89,93–97], and vice versa, many of the experiments described in this review were designed to prove or disprove certain models/ hypothesis. For example, hydrogels (in which FG-domains interact with each other) have been suggested to represent a selective phase in the NPC [71,72,98]. NTRs have the ability to easily penetrate this phase, even when binding cargo molecules, as hypothesized in Ref. [99]. Another model is based on FG-domains forming a brush (in which FG-domains do not interact with each other), which fills the NPC channel and is suggested to form a barrier [85]. The reader is referred to many excellent reviews (e.g., see Ref. [10] and Grunwald and Musser in this issue [9] in which various transport models are discussed in detail). However, in this review, I introduced some of the core observations described in the literature and aimed to express that many are credible in the context of what can be expected from a polymer. There seems to be many possibilities on how FG-domains can assemble/phase separate, and thus, the cell biologist is tasked with designing experiments to test for or to exclude the existence of a particular state or phase. In addition, more than one state can exist in parallel for an FG-domain, and states might also be in dynamic equilibrium. New types of experiments that can directly visualize the arrangement and dynamics of FG-domains in the functional NPC will be helpful to address the design of how a barrier is formed inside the NPC and how it functions.

However, especially if one looks into the diversity of FG-domains and the rather low conservation across species, it is clear that many more regulatory mechanisms encoded into the NPC machinery remain to be discovered, even if the field could agree on a general working principle of the transport mechanism. It would be especially useful to reconstitute the NPC machinery in vitro in a bottom-up approach so that function could be studied against an increasing number of building blocks. The formation of artificial nanopores [92,94], and the design of functional NPCs in cells with a reduced number of permeability barrier proteins [100,101] are important steps to deal with the complexity of the full NPC transport machinery. Another particularly powerful approach is single-molecule observation of the NPC machinery, as it affords a direct view in cells of how single transport events are achieved (see Ref. [9]).

Computer simulations will be important assets for testing different scenarios, and indeed many have already been performed and stimulated the design of experiments to test and predict the working mechanism of NPCs. However, many different simulations are not yet converging on the same conclusion, and the reader is thus referred to the primary literature on these topics, which can, for example, be found in Refs. [95] and [102–108]. However, the power of computational approaches grows with the number of available parameters to constrain simulations, and thus, these tools will improve the more experimental data that are generated at various levels of complexity, ranging from properties of isolated molecules to function of large assemblages and in vivo behavior.

Acknowledgements

I thank Aritra Chowdhury, Adrian Neal, and Iker Valle Aramburu for critical reading of the manuscript, as well as my whole group for helpful discussions. Funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Emmy Noether Program and the European Research Council consolidator grant SMPFv2.0 are gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations used

- IDP

intrinsically disordered protein

- NPC

nuclear pore complex

- EM

electron microscopy

- NTR

nuclear transport receptor

- FUS

fused in sarcoma

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

References

- [1].Eibauer M, Pellanda M, Turgay Y, Dubrovsky A, Wild A, Medalia O. Structure and gating of the nuclear pore complex. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7532. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bui KH, von Appen A, DiGuilio AL, Ori A, Sparks L, Mackmull MT, Bock T, Hagen W, Andres-Pons A, Glavy JS, Beck M. Integrated structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex scaffold. Cell. 2013;155:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].von Appen A, Kosinski J, Sparks L, Ori A, DiGuilio AL, Vollmer B, Mackmull MT, Banterle N, Parca L, Kastritis P, Buczak K, et al. In situ structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2015;526:140–143. doi: 10.1038/nature15381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].von Appen A, Beck M. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.01.004. in this special issue, (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Terry LJ, Shows EB, Wente SR. Crossing the nuclear envelope: Hierarchical regulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Science. 2007;318:1412–1416. doi: 10.1126/science.1142204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Grunwald D, Singer RH. Multiscale dynamics in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;24:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pante N, Kann M. Nuclear pore complex is able to transport macromolecules with diameters of about 39 nm. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:425–434. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-06-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Izaurralde E, Kutay U, von Kobbe C, Mattaj IW, Gorlich D. The asymmetric distribution of the constituents of the Ran system is essential for transport into and out of the nucleus. EMBO J. 1997;16:6535–6547. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Grunwald D, Musser SM. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.02.023. in this special issue (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Walde S, Kehlenbach RH. The part and the whole: Functions of nucleoporins in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ando D, Colvin M, Rexach M, Gopinathan A. Physical motif clustering within intrinsically disordered nucleoporin sequences reveals universal functional features. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schmidt HB, Gorlich D. Nup98 FG domains from diverse species spontaneously phase-separate into particles with nuclear pore-like permselectivity. eLife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.04251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Denning D, Mykytka B, Allen NP, Huang L, Al B, Rexach M. The nucleoporin Nup60p functions as a Gsp1p-GTP-sensitive tether for Nup2p at the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:937–950. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200101007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Denning DP, Patel SS, Uversky V, Fink AL, Rexach M. Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: The FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2450–2455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437902100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tompa P. Intrinsically unstructured proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tompa P, Fuxreiter M. Fuzzy complexes: Polymorphism and structural disorder in protein-protein interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Oates ME, Romero P, Ishida T, Ghalwash M, Mizianty MJ, Xue B, Dosztanyi Z, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z, Kurgan L, Dunker AK, et al. D(2)P(2): Database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D508–D516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tompa P, Szasz C, Buday L. Structural disorder throws new light on moonlighting. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Das RK, Ruff KM, Pappu RV. Relating sequence encoded information to form and function of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;32:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Das RK, Pappu RV. Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13392–13397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304749110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fischer J, Teimer R, Amlacher S, Kunze R, Hurt E. Linker Nups connect the nuclear pore complex inner ring with the outer ring and transport channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:774–781. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Diella F, Cameron S, Gemund C, Linding R, Via A, Kuster B, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Blom N, Gibson TJ. Phospho.ELM: A database of experimentally verified phosphorylation sites in eukaryotic proteins. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lu X, Hamkalo B, Parseghian MH, Hansen JC. Chromatin condensing functions of the linker histone C-terminal domain are mediated by specific amino acid composition and intrinsic protein disorder. Biochemistry. 2009;48:164–172. doi: 10.1021/bi801636y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Teraoka I. Polymer solutions: An introduction to physical properties. Wiley; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Krishnan VV, Lau EY, Yamada J, Denning DP, Patel SS, Colvin ME, Rexach MF. Intramolecular cohesion of coils mediated by phenylalanine–glycine motifs in the natively unfolded domain of a nucleoporin. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yamada J, Phillips JL, Patel S, Goldfien G, Calestagne-Morelli A, Huang H, Reza R, Acheson J, Krishnan VV, Newsam S, Gopinathan A, et al. A bimodal distribution of two distinct categories of intrinsically-disordered structures with separate functions in FG nucleoporins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2205–2224. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000035-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Soranno A, Buchli B, Nettels D, Cheng RR, Muller-Spath S, Pfeil SH, Hoffmann A, Lipman EA, Makarov DE, Schuler B. Quantifying internal friction in unfolded and intrinsically disordered proteins with singlemolecule spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17800–17806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117368109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hofmann H, Soranno A, Borgia A, Gast K, Nettels D, Schuler B. Polymer scaling laws of unfolded and intrinsically disordered proteins quantified with single-molecule spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U SA. 2012;109:16155–16160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207719109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Milles S, Lemke EA. Single molecule study of the intrinsically disordered FG-repeat nucleoporin 153. Biophys J. 2011;101:1710–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mukhopadhyay S, Krishnan R, Lemke EA, Lindquist S, Deniz AA. A natively unfolded yeast prion monomer adopts an ensemble of collapsed and rapidly fluctuating structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2649–2654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611503104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tetenbaum-Novatt J, Hough LE, Mironska R, McKenney AS, Rout MP. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: A role for non-specific competition in karyopherin-nucleoporin interactions. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:31–46. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ben-Efraim I, Gerace L. Gradient of increasing affinity of importin beta for nucleoporins along the pathway of nuclear import. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:411–417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bednenko J, Cingolani G, Gerace L. Importin beta contains a COOH-terminal nucleoporin binding region important for nuclear transport. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tu LC, Fu G, Zilman A, Musser SM. Large cargo transport by nuclear pores: Implications for the spatial organization of FG-nucleoporins. EMBO J. 2013;32:3220–3230. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hough LE, Dutta K, Sparks S, Temel DB, Kamal A, Tetenbaum-Novatt J, Rout MP, Cowburn D. The molecular mechanism of nuclear transport revealed by atomic-scale measurements. eLife. 2015;4:e10027. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bayliss R, Littlewood T, Stewart M. Structural basis for the interaction between FxFG nucleoporin repeats and importin-beta in nuclear trafficking. Cell. 2000;102:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bayliss R, Littlewood T, Strawn LA, Wente SR, Stewart M. GLFG and FxFG nucleoporins bind to overlapping sites on importin-beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50597–50606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Isgro TA, Schulten K. Binding dynamics of isolated nucleoporin repeat regions to importin-beta. Structure. 2005;13:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Koyama M, Shirai N, Matsuura Y. Structural insights into how Yrb2p accelerates the assembly of the Xpo1p nuclear export complex. Cell Rep. 2014;9:983–995. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cook A, Bono F, Jinek M, Conti E. Structural biology of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:647–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.161529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Otsuka S, Iwasaka S, Yoneda Y, Takeyasu K, Yoshimura SH. Individual binding pockets of importin-beta for FG-nucleoporins have different binding properties and different sensitivities to RanGTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16101–16106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802647105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Port SA, Monecke T, Dickmanns A, Spillner C, Hofele R, Urlaub H, Ficner R, Kehlenbach RH. Structural and functional characterization of CRM1-Nup214 interactions reveals multiple FG-binding sites involved in nuclear export. Cell Rep. 2015;13:690–702. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kubitscheck U, Grunwald D, Hoekstra A, Rohleder D, Kues T, Siebrasse JP, Peters R. Nuclear transport of single molecules: Dwell times at the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:233–243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yang W, Gelles J, Musser SM. Imaging of single-molecule translocation through nuclear pore complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12887–12892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403675101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Milles S, Mercadante D, Aramburu IV, Jensen MR, Banterle N, Koehler C, Tyagi S, Clarke J, Shammas SL, Blackledge M, Grater F, et al. Plasticity of an ultrafast interaction between nucleoporins and nuclear transport receptors. Cell. 2015;163:734–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ganguly D, Zhang W, Chen J. Electrostatically accelerated encounter and folding for facile recognition of intrinsically disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Milles S, Lemke EA. Mapping multivalency and differential affinities within large intrinsically disordered protein complexes with segmental motion analysis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:7364–7367. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Morrison J, Yang J-C, Stewart M, Neuhaus D. Solution NMR study of the interaction between NTF2 and nucleoporin FxFG repeats. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:587–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Vognsen T, Møller IR, Kristensen O. Crystal structures of the human G3BP1 NTF2-like domain visualize FxFG Nup repeat specificity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Adams RL, Wente SR. Uncovering nuclear pore complexity with innovation. Cell. 2013;152:1218–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Brown CR, Kennedy CJ, Delmar VA, Forbes DJ, Silver PA. Global histone acetylation induces functional genomic reorganization at mammalian nuclear pore complexes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:627–639. doi: 10.1101/gad.1632708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Vaquerizas JM, Suyama R, Kind J, Miura K, Luscombe NM, Akhtar A. Nuclear pore proteins Nup153 and megator define transcriptionally active regions in the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Capelson M, Hetzer MW. The role of nuclear pores in gene regulation, development and disease. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:697–705. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M. Nucleoporins directly stimulate expression of developmental and cell-cycle genes inside the nucleoplasm. Cell. 2010;140:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kehat I, Accornero F, Aronow BJ, Molkentin JD. Modulation of chromatin position and gene expression by HDAC4 interaction with nucleoporins. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:21–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Arib G, Akhtar A. Multiple facets of nuclear periphery in gene expression control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Koo EH, Lansbury PT, Jr, Kelly JW. Amyloid diseases: Abnormal protein aggregation in neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9989–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Agócs G, Szabó Bence T, Köhler G, Osváth S. Comparing the folding and misfolding energy landscapes of phosphoglycerate kinase. Biophys J. 2012;102:2828–2834. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schmittschmitt JP, Scholtz JM. The role of protein stability, solubility, and net charge in amyloid fibril formation. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2374–2378. doi: 10.1110/ps.03152903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Uversky VN. Targeting intrinsically disordered proteins in neurodegenerative and protein dysfunction diseases: Another illustration of the D(2) concept. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2010;7:543–564. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 2009;137:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Frederick KK, Debelouchina GT, Kayatekin C, Dorminy T, Jacavone AC, Griffin RG, Lindquist S. Distinct prion strains are defined by amyloid core structure and chaperone binding site dynamics. Chem Biol. 2014;21:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ader C, Frey S, Maas W, Schmidt HB, Gorlich D, Baldus M. Amyloid-like interactions within nucleoporin FG hydrogels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6281–6285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910163107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Halfmann R, Wright J, Alberti S, Lindquist S, Rexach M. Prion formation by a yeast GLFG nucleoporin. Prion. 2012;6:391–399. doi: 10.4161/pri.20199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Milles S, Huy Bui K, Koehler C, Eltsov M, Beck M, Lemke EA. Facilitated aggregation of FG nucleoporins under molecular crowding conditions. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:178–183. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Broncel M, Falenski JA, Wagner SC, Hackenberger CPR, Koksch B. How post-translational modifications influence amyloid formation: A systematic study of phosphorylation and glycosylation in model peptides. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:7881–7888. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bachhuber T, Katzmarski N, McCarter JF, Loreth D, Tahirovic S, Kamp F, Abou-Ajram C, Nuscher B, Serrano-Pozo A, Muller A, Prinz M, et al. Inhibition of amyloid-beta plaque formation by alpha-synuclein. Nat Med. 2015;21:802–807. doi: 10.1038/nm.3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Park JY, Lansbury PT., Jr Beta-synuclein inhibits formation of alpha-synuclein protofibrils: A possible therapeutic strategy against Parkinson’s disease. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3696–3700. doi: 10.1021/bi020604a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Frey S, Gorlich D. A saturated FG-repeat hydrogel can reproduce the permeability properties of nuclear pore complexes. Cell. 2007;130:512–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Frey S, Richter RP, Gorlich D. FG-rich repeats of nuclear pore proteins form a three-dimensional meshwork with hydrogel-like properties. Science. 2006;314:815–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1132516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Labokha AA, Gradmann S, Frey S, Hulsmann BB, Urlaub H, Baldus M, Gorlich D. Systematic analysis of barrier-forming FG hydrogels from Xenopus nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J. 2013;32:204–218. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Yang Z, Liang G, Wang L, Xu B. Using a kinase/phosphatase switch to regulate a supramolecular hydrogel and forming the supramolecular hydrogel in vivo . J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3038–3043. doi: 10.1021/ja057412y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Brangwynne CP, Eckmann CR, Courson DS, Rybarska A, Hoege C, Gharakhani J, Julicher F, Hyman AA. Germline P granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science. 2009;324:1729–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1172046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hyman AA, Weber CA, Julicher F. Liquid–liquid phase separation in biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:39–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Toretsky JA, Wright PE. Assemblages: Functional units formed by cellular phase separation. J Cell Biol. 2014;206:579–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Patel A, Lee HO, Jawerth L, Maharana S, Jahnel M, Hein MY, Stoynov S, Mahamid J, Saha S, Franzmann TM, Pozniakovski A, et al. A liquid-to-solid phase transition of the ALS protein FUS accelerated by disease mutation. Cell. 2015;162:1066–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Molliex A, Temirov J, Lee J, Coughlin M, Kanagaraj AP, Kim HJ, Mittag T, Taylor JP. Phase separation by low complexity domains promotes stress granule assembly and drives pathological fibrillization. Cell. 2015;163:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Jiang H, Wang S, Huang Y, He X, Cui H, Zhu X, Zheng Y. Phase transition of spindle-associated protein regulate spindle apparatus assembly. Cell. 2015;163:108–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Li P, Banjade S, Cheng HC, Kim S, Chen B, Guo L, Llaguno M, Hollingsworth JV, King DS, Banani SF, Russo PS, et al. Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature. 2012;483:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lowe AR, Tang JH, Yassif J, Graf M, Huang WY, Groves JT, Weis K, Liphardt JT. Importin-beta modulates the permeability of the nuclear pore complex in a Ran-dependent manner. eLife. 2015;4:e04052. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Lim RY, Deng J. Interaction forces and reversible collapse of a polymer brush-gated nanopore. ACS Nano. 2009;3:2911–2918. doi: 10.1021/nn900152m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Roy R, Hohng S, Ha T. A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nat Methods. 2008;5:507–516. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Lim RY, Fahrenkrog B, Koser J, Schwarz-Herion K, Deng J, Aebi U. Nanomechanical basis of selective gating by the nuclear pore complex. Science. 2007;318:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1145980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Eisele NB, Labokha AA, Frey S, Gorlich D, Richter RP. Cohesiveness tunes assembly and morphology of FG nucleoporin domain meshworks—Implications for nuclear pore permeability. Biophys J. 2013;105:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Eisele NB, Andersson FI, Frey S, Richter RP. Viscoelasticity of thin biomolecular films: A case study on nucleoporin phenylalanine-glycine repeats grafted to a histidine-tag capturing QCM-D sensor. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:2322–2332. doi: 10.1021/bm300577s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Eisele NB, Frey S, Piehler J, Gorlich D, Richter RP. Ultrathin nucleoporin phenylalanine-glycine repeat films and their interaction with nuclear transport receptors. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:366–372. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Wagner RS, Kapinos LE, Marshall NJ, Stewart M, Lim RY. Promiscuous binding of karyopherinbeta1 modulates FG nucleoporin barrier function and expedites NTF2 transport kinetics. Biophys J. 2015;108:918–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Schoch RL, Kapinos LE, Lim RY. Nuclear transport receptor binding avidity triggers a self-healing collapse transition in FG-nucleoporin molecular brushes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16911–16916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208440109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Schleicher KD, Dettmer SL, Kapinos LE, Pagliara S, Keyser UF, Jeney S, Lim RY. Selective transport control on molecular velcro made from intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:525–530. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Kowalczyk SW, Kapinos L, Blosser TR, Magalhaes T, van Nies P, Lim RY, Dekker C. Single-molecule transport across an individual biomimetic nuclear pore complex. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:433–438. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Magnasco MO, Chait BT. Virtual gating and nuclear transport: The hole picture. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:622–628. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Jovanovic-Talisman T, Tetenbaum-Novatt J, McKenney AS, Zilman A, Peters R, Rout MP, Chait BT. Artificial nanopores that mimic the transport selectivity of the nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2009;457:1023–1027. doi: 10.1038/nature07600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Moussavi-Baygi R, Jamali Y, Karimi R, Mofrad MR. Brownian dynamics simulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport: A coarse-grained model for the functional state of the nuclear pore complex. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Peters R. Translocation through the nuclear pore: Kaps pave the way. BioEssays. 2009;31:466–477. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Patel SS, Belmont BJ, Sante JM, Rexach MF. Natively unfolded nucleoporins gate protein diffusion across the nuclear pore complex. Cell. 2007;129:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Schmidt HB, Gorlich D. Transport selectivity of nuclear pores, phase separation, and membraneless organelles. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;41:46–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Ribbeck K, Gorlich D. Kinetic analysis of translocation through nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J. 2001;20:1320–1330. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Strawn LA, Shen T, Shulga N, Goldfarb DS, Wente SR. Minimal nuclear pore complexes define FG repeat domains essential for transport. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ncb1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Hulsmann BB, Labokha AA, Gorlich D. The permeability of reconstituted nuclear pores provides direct evidence for the selective phase model. Cell. 2012;150:738–751. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Ghavami A, Veenhoff LM, van der Giessen E, Onck PR. Probing the disordered domain of the nuclear pore complex through coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J. 2014;107:1393–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Mincer JS, Simon SM. Simulations of nuclear pore transport yield mechanistic insights and quantitative predictions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E351–E358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104521108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Ando D, Zandi R, Kim YW, Colvin M, Rexach M, Gopinathan A. Nuclear pore complex protein sequences determine overall copolymer brush structure and function. Biophys J. 2014;106:1997–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Gamini R, Han W, Stone JE, Schulten K. Assembly of Nsp1 nucleoporins provides insight into nuclear pore complex gating. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Zilman A, Di Talia S, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Chait BT, Rout MP, Magnasco MO. Enhancement of transport selectivity through nano-channels by non-specific competition. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Opferman MG, Coalson RD, Jasnow D, Zilman A. Morphological control of grafted polymer films via attraction to small nanoparticle inclusions. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2012;86:031806. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.031806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Bestembayeva A, Kramer A, Labokha AA, Osmanovic D, Liashkovich I, Orlova EV, Ford IJ, Charras G, Fassati A, Hoogenboom BW. Nanoscale stiffness topography reveals structure and mechanics of the transport barrier in intact nuclear pore complexes. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10:60–64. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]