Abstract

Background

Mental capacity is an emerging ethical legal concept in psychiatric settings but its relation to clinical parameters remains uncertain. We sought to investigate the associations of regaining capacity to make treatment decisions following approximately 1 month of in-patient psychiatric treatment.

Method

We followed up 115 consecutive patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital who were judged to lack capacity to make treatment decisions at the point of hospitalization. We were primarily interested in whether the diagnosis of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder associated with reduced chances of regaining capacity compared with other diagnoses and whether affective symptoms on admission associated with increased chances of regaining capacity. In addition, we examined how change in insight was associated with regaining capacity in schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder (BPAD)-mania, and depression.

Results

We found evidence that the category of ‘schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder’ associated with not regaining capacity at 1 month compared with BPAD-mania [odds ratio (OR) 3.62, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.13-11.6] and depression (OR 5.35, 95% CI 1.47-9.55) and that affective symptoms on admission associated with regaining capacity (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.02-1.48). In addition, using an interaction model, we found some evidence that gain in insight may not be a good indicator of regaining capacity in patients with depression compared with patients with schizophrenia and BPAD-mania.

Conclusions

We suggest that clinico-ethical studies using mental capacity provide a way of assessing the validity of nosological and other clinical concepts in psychiatry.

Keywords: Empirical ethics, ethics, insight, mental capacity, nosology, psychopathology

Introduction

Since the 1950s, the concept of mental capacity – which relates to people with mental disorder, whatever the cause – has been evolving in the courts in both the USA (Appelbaum & Grisso, 1995; Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998) and Europe (Richardson, 2005) as a means of safeguarding the right of individual autonomy. Most liberal legal systems now have two systems of law in relation to people with mental disorder: one that is based on the law of consent, and typically incorporates the notion of mental capacity, and another that is mainly based upon risk and risk management with no consistent reference to the law of consent.

Clinicians treating mental disorder in a psychiatric hospital have generally not had to consider the concept of mental capacity because risk-based systems of law have traditionally applied in this setting (Appelbaum, 1995; Fennell, 1996). This is no longer the case, clinicians are increasingly being expected to assess mental capacity and think within frameworks of the law that place major emphasis on it. Recent capacity statutes in the UK [Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act, 2000; The Mental Capacity Act, 2005] are examples of this.

Relative to its importance, very little research evidence is available to guide clinicians in the assessment of mental capacity. Studies aiming to clarify the relationships between capacity and concepts with which clinicians are more familiar are even sparser. Clinicians need a firmer grip on the relationships that mental capacity has to clinical concepts that have evolved to assist decision making about whether the necessary conditions for surrogate decision making are met. Such clinical concepts include psychiatric diagnoses, psychiatric symptoms and insight.

Several key decision-making points exist for clinicians with regard to surrogate treatment decision making. Foremost amongst these are the point of admission to hospital and the point of discharge to the community or the point following a period of inpatient treatment. In relation to admission, there is some evidence about the prevalence and clinical associations of capacity (Cairns et al. 2005; Okai et al. 2007; Owen et al. 2008, 2009). In relation to discharge, or the points in time following treatment, there is almost no information about mental capacity. With the transition to legal systems that place more weight upon the concept of mental capacity, this absence of data is leaving the law, psychiatry and society in a condition of uncertainty. More empirical data about the relationship between mental capacity and other variables in clinical settings are now needed. This is especially the case in clinical settings where levels of perceived risk run high and the threshold for moral panic is low (Appelbaum, 2003) – the acute psychiatric hospital is such a setting.

This study is the first follow-up of mental capacity in the psychiatric in-patient setting. As well as providing descriptive and experimental data on the associations of regaining mental capacity after approximately 1 month period of in-patient treatment, we wish to test two hypotheses.

The first is that schizophrenia and related disorders are associated with a reduced chance of regaining capacity. The second is that affective symptoms at admission are associated with an increased chance of regaining capacity. Since Kraepelin, schizophrenia and related disorders have been thought of as carrying a poorer prognosis than other psychiatric disorders. In Leonhard’s classification of the endogenous psychoses, the schizophrenias are characterized as having relatively non-phasic courses with low chances of recovery, whilst the disorders with more affective symptoms are characterized as more phasic with a greater expectation of recovery (Leonhard, 1957) Neither Kraepelin nor Leonhardt were very clear about how ‘recovery’ related to decision-making ability. We seek to relate these nosological concepts to the ethical legal concept of decisional capacity.

In addition to the above, we sought to explore the relationships between mental capacity, diagnosis and insight. Previous results from a cross-sectional study have shown a stronger association between incapacity and low insight in patients with psychosis and bipolar mania than patients with depression (Owen et al. 2009). In this follow-up study we examine the associations between regaining mental capacity, diagnosis and change in insight. From our previous work (Owen et al. 2009) we expect to find that depression exerts effects on capacity in a manner that is different quantitatively and qualitatively from schizophrenia and mania.

Method

This study has been described in detail elsewhere (Owen et al. 2008). Consecutively admitted patients between February 2006 and June 2007 to three general adult psychiatric wards (one female and two male), serving a deprived inner-city area, at the Maudsley Hospital, London were included in this study. Patients were identified by regular examination of the electronic medical records and consultations with the ward nursing staff. All admissions were included other than those admitted during planned research breaks. The sole exclusions were patients from other catchment areas admitted to the wards and patients transferred from other in-patient facilities. All patients who spoke English were approached for a research interview. Those who assented were provided with full details of the study and the interview was stopped if there was any subsequent change in choice or resistance. Written consent was sought and patients were offered £5 for their time. Interviews were conducted as close to the admission as possible. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee.

Assessment of capacity

Relevant information about the patient’s presenting problems, diagnosis and treatment plan was obtained from their medical records and discussion with the clinical team. The clinical researcher (G.O.) determined whether the treating team’s principal treatment concerned medication or admission to hospital. If it was medication, then the capacity assessment centred on the decision to take the prescribed medication or not. This involved a disclosure about that medication and its risks and benefits. If it was hospitalization then it was the capacity to decide on whether to come into hospital or not. This involved disclosures about what hospital offered (e.g. focused assessment, place of safety), what out-patient services offered (e.g. home environment, follow-up) and their risks and benefits. This scheme was adopted to reflect the decisions that face most patients in the acute setting and to keep the interviews focused.

The presence or absence of capacity to decide on treatment was based on the two-stage test formulated in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. This requires; (1) evidence of ‘an impairment of, or disturbance in, the functioning of the mind or brain’ [Section 2(1)]; (2) evidence that this impairment or disturbance means that the person is unable to make a specific decision [Section 3(1)]. We interpreted the first stage of the test using clinical psychopathological concepts and ICD-10 diagnoses (WHO, 1992).

The capacity assessment was facilitated by a clinical assessment (notes review and clinical interview) and the administration of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T) (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998; Appelbaum, 2007). The MacCAT-T is a semi-structured interview that provides relevant information disclosures to patients about their illness, the nature of treatment options and their risks and benefits. The assessor evaluates capacity in terms of four abilities relating to the disclosures: understanding; appreciation; reasoning; expressing a choice. These abilities map on to the abilities regarded as relevant by the Mental Capacity Act 2005, which are understanding, retaining, using, weighing and communicating. ‘Using’ is the term the Law Commission favoured in place of the term ‘appreciation’ (The Law Commission, 1995, para 3.17). We interpreted the terms to have equivalent meanings. A key feature of the capacity test is that it requires evidence that the decision-making process is impaired; it takes the focus off the decision-making outcome. The judgement about capacity followed the approach outlined by Grisso & Appelbaum (1998). This incorporated presenting the information relevant to the decision in simple language and repeating and rephrasing as judged appropriate. It also incorporated the ‘sliding scale’ concept, whereby decisions that carry a greater risk require greater evidence of the relevant decisionmaking abilities. This concept is similar to the English Law requirement that the graver the consequences of the decision, the commensurately greater the level of competence that is required to make it.

The content of the MacCAT-T was modified for this study. When the principal treatment decision concerned medication, patients were given a disclosure about ‘no medication’ as the alternative to the ‘recommended’ medication rather than iterate through all medication options. This was done to simplify the interview and to reflect the main choice that patients who are acutely ill typically face. When the principal treatment decision concerned hospitalization, patients were given a disclosure about the option of being an in-patient or not. Each disclosure involved giving the patient simple information about the nature of the option and its risks and benefits. The form of the MacCAT-T was left unaltered by these changes. Previous studies have demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability (κ>0.8) when the MacCAT-T is used in this way (Cairns et al. 2005; Okai et al. 2007).

Other variables

The Expanded Schedule for the Assessment of Insight (SAI-E; Sanz et al. 1998) and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Ventura et al. 1993) were also administered. Both are clinically based, semi-structured interviews. The SAI-E comprises three main dimensions (awareness of illness; re-labelling of symptoms as abnormal; treatment compliance). A total score was calculated. We adjusted the total BPRS score to account for domains of psychopathology that were not assessable (e.g. hallucinations in a mute patient) by summing subscores and dividing the total by the number of BPRS domains that were assessable. This was done to obtain a measure of total psychopathology that was not misleadingly low in patients who did not respond to questions about symptoms. We defined ‘affective’ symptoms as the sum of the depression and elation subscores and ‘psychotic’ symptoms as the sum of the hallucinations, unusual thought content and conceptual disorganization subscores.

We used the matrix reasoning subtest from the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (PsychCorp, 1999) to assess cognition. This consists of four non-verbal reasoning tasks: pattern recognition ; classification; analogy; serial reasoning. This subtest has the advantage of being less dependent on language in a sample where many did not have English as a first language. We converted raw scores into age-adjusted t score equivalents according to the manual.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were collected from the medical records and nursing observations.

Only if patients were found to lack capacity at admission were they followed up. The follow-up assessment took place at either the point of discharge from hospital or at 1 month (whichever was sooner). At follow-up, the capacity assessment was repeated, together with the assessment of insight. The permission procedure was the same. Fig. 1 shows the flow of patients through the study.

Fig. 1. Flow of patients through the study.

Statistical analysis

The capacity assessment at the follow-up defines a binary outcome (regain/not regain capacity), subject to logistic regression analysis. Multiple imputation methods using ice family commands (Rubin, 1976; Royston, 2004; 2005a, b) in Stata 10.1 (StataCorp, USA) have been used to deal with the missing capacity evaluations at the follow-up (about 18%) and with parameter estimation. We have assumed that the missing at random assumption holds (Rubin, 1976). A model including all the covariates of interest has been used for imputation.

Regarding the exploration of the combined effects of insight and diagnosis on capacity, we examined the change in insight score, calculated as the difference between the insight scores recorded at the follow-up and on admission. We selected change in insight as the variable of interest because absolute levels of insight can vary according to cultural factors rather than illness (Kirmayer et al. 2004). Change in insight is a continuous, fairly normally distributed variable (mean=5.66, S.D.=8.11) with 29% missing records due to non-assessability. It is important to state that there is no missing information in the diagnosis group variable. The imputation model was reasonably rich, also including the age of the patients (completed for each participant in the study) in addition to the diagnosis and capacity groups. Interaction terms have been passively imputed as they are not independent variables using Stata ice specific options (passive). An empirical plot for goodness of fit (standardized residuals against the fitted values for the observed data) was consistent with regression assumptions. A post-hoc estimation predicts the average insight change in each cell determined by the two groups (with and without interaction).

Results

Descriptive data

Of the 350 patients who entered the study, 200 (57.1%) participated in formal capacity assessments. The details of participants and non-participants at this stage of the study are given elsewhere (Owen et al. 2008). Of the patients formally assessed on admission, 115 (57.5%) lacked capacity to make treatment decisions and were followed up. In total, 21 patients (18%) were lost to follow-up (10 refused re-assessment and 11 were discharged before seen and could not be contacted). Of those followed, 35 patients (37%) were judged to have regained capacity.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients who regained capacity compared to patients who did not. The time between capacity assessments was comparable and averages just less than 1 month in both groups. Age and years of education were also similar. There are apparent differences between patients of male gender and black ethnicity with greater percentages of patients with black ethnicity and male gender not regaining capacity but the potential confounds are numerous and the numbers are too small for further analysis (Singh et al. 2007; Owen et al. 2009). Diagnostic groups appear to be different and this is tested in the univariate analysis below (Table 2). The ‘other’ category comprised mainly psychotic episodes (76%), where the underlying disorder was uncertain. Living in supported accommodation appeared as if it may be associated with reduced chances of regaining capacity; involuntary admission did not. Level of symptoms on admission and cognitive ability, as measured using the matrix reasoning task, did not appear to strongly relate to regaining capacity.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients regaining and not regaining capacity.

| Variables | Regaining capacity (n=35) | Not regaining capacity (n=59) |

|---|---|---|

| Days between interviews, mean (S.D.) | 24.1 (8.5) | 25.3 (9.1) |

| Age in years, mean (S.D.) | 41.6 (10.9) | 39.0 (11.4) |

| Years of education, mean (S.D.) | 7.1 (3.5) | 7.2 (2.8) |

| Years of service contact, mean (S.D.) | 14.5 (12.3) | 12.1 (10.4) |

| Total BPRS score (adjusted) on admission, mean (S.D.) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.7) |

| Matrix reasoning score on admission, mean (S.D.) | 38.8 (12.0) | 33.9 (11.3) |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (52.6) | 39 (66.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 19 (54.3) | 18 (30.5) |

| Black | 11 (31.4) | 36 (61.0) |

| Other | 5 (14.3) | 5 (8.5) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 7 (20.0) | 26 (44.1) |

| BPAD-manic | 11 (31.4) | 10 (16.9) |

| Depression – unipolar or bipolar | 7 (20.0) | 4 (6.8) |

| Other | 10 (28.6) | 19 (32.2) |

| Supported accommodation, n (%) | 1 (2.9) | 9 (15.3) |

| Involuntary admission under Mental Health Act, n (%) | 21 (60.0) | 36 (61.0) |

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BPAD, bipolar affective disorder.

Table 2. Univariate associations of regaining capacity (with imputation unless specified).

| Variable | N | Effect sizes | p value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic group | OR of regaining capacity relative to reference group | |||

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 40 | Reference group | – | – |

| BPAD-mania | 22 | 3.62 | 0.03 | 1.13-11.6 |

| Depression (unipolar or bipolar) | 16 | 5.35 | 0.01 | 1.47-19.55 |

| Other | 37 | 2.09 | 0.16 | 0.74-5.88 |

| Continuous variables (scale range) | OR for unit increase of the variable | |||

| Affective symptoms on admission (0-14) | 1.23 | 0.03 | 1.02-1.48 | |

| Psychotic symptoms on admission (0-21) | 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.85-1.13 | |

| Insight on admission (0-28) | 1.07 | 0.02 | 1.01-1.13 | |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.44 | 0.98-1.05 | |

| Years of service contact | 1.01 | 0.58 | 0.97-1.06 | |

| Categorical variables without imputation (raw data range) | ||||

| Affective symptoms on admission | ||||

| Low (0-3) | 36 | 0.03a | ||

| Medium (4-6) | 24 | |||

| High (7-10) | 25 | |||

| Psychotic symptoms on admission | ||||

| Low (3-6) | 14 | 0.45a | ||

| Medium (7-13) | 39 | |||

| High (14-19) | 14 | |||

| Insight on admission | ||||

| Low (2-7) | 39 | 0.08a | ||

| Medium (7-17) | 36 | |||

| High (17-26) | 12 | |||

CI, Confidence intervals; OR, odds ratio; BPAD, bipolar affective disorder.

Test for trend of regaining capacity (without imputation).

Fig. 2 shows the change in adjusted total BPRS score across the follow-up period according to diagnosis and whether capacity was regained. The great majority of patients improved symptomatically regardless of whether capacity was regained. All patients who regained capacity improved symptomatically.

Fig. 2.

Box plot of change in total symptoms (adjusted) according to diagnosis and regaining or not regaining capacity (× represent means). BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BPAD, bipolar affective disorder.

Fig. 3 shows the change in abilities scores from the MacCAT interview across the follow-up period according to whether capacity was regained. The expressing a choice ability is omitted because it has less relevance in this setting. Understanding, appreciation and reasoning all show change across the follow-up with the changes in abilities all significantly greater if capacity is regained (Kruskal-Wallis test, p values all <0.001). In the regaining capacity group, the means are normally distributed and relative to the scales for understanding (0-6), appreciation (0-4) and reasoning (0-8) represent changes of approximately 30% (understanding), 40% (appreciation) and 50% (reasoning).

Fig. 3.

Box plot of change in understanding (◼), appreciation (◼) and reasoning (◻) according to regaining or not regaining capacity (× represent means).

Univariate analysis

Table 2 shows the univariate associations of regaining capacity using imputation for missing follow-up data. We found some evidence that the odds of regaining capacity is 3.62 times higher [95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.13-11.6, p=0.03] for bipolar affective disorder (BPAD) mania and 5.35 times higher (95% CI 1.47-19.55, p=0.01) for depression compared with schizophrenia and related disorders. We found no evidence of a significant difference between BPAD mania and depression (p=0.72) with regard to the odds of regaining capacity. Nevertheless, the wide CI limit these conclusions.

There is some evidence that regaining capacity is associated with affective symptoms on admission (p=0.03). In contrast, there was no evidence for an association between ‘psychotic symptoms score’ on admission and the odds of regaining capacity (p=0.80). Insight on admission was associated with regaining capacity to a modest extent (p=0.02). There is no evidence of an association between regaining capacity and participants’ age (p=0.44) or years of contact with service (p=0.58; Table 2). We also analysed the possibility of an interaction between diagnosis and age or years of service contact and no evidence for these. The p values corresponding to interaction terms for age/years of contact with diagnosis exceeded 0.3. This suggested that age or length of illness were not associated with regaining capacity and not strong effect modifiers of regaining capacity.

These quantifications of affective symptoms, psychotic symptoms and insight with mental capacity status need to be interpreted cautiously because they assume the same effect size across a scale (such that the difference between, for example, 1 and 2 on the scale is equivalent to the difference between 7 and 8). However, similar associations are seen if one categorizes these variables into a low, medium and high score for each scale following a test for trend in proportions of the people regaining capacity across the newly created categories (Table 2). The results display some evidence of an association between affective symptoms and regaining capacity (p=0.03), a lack of association with psychotic symptoms (p=0.45) and a marginal association with baseline insight (p=0.08). The tests were performed on crude data (without imputation). They are, as expected, consistent with the results, using their continuous analogues and the imputation method (Table 2).

Analysis of insight

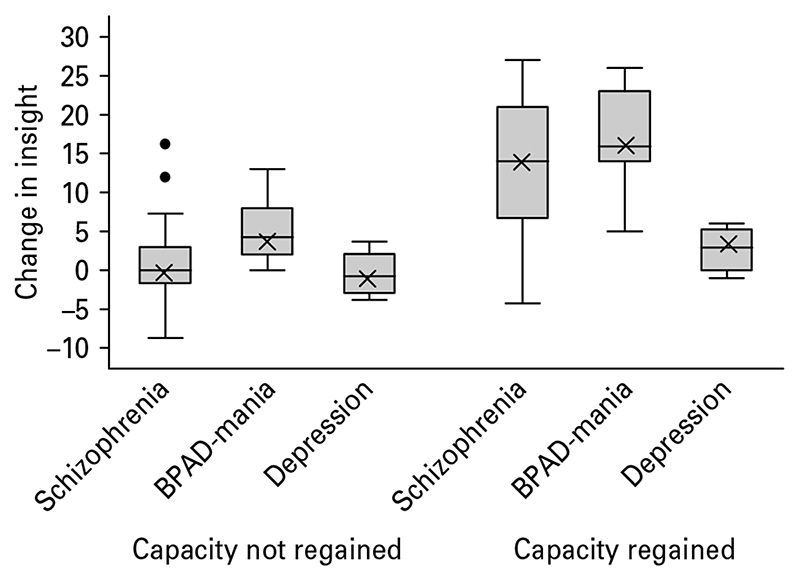

Fig. 4 is a box plot showing scores for observed data without imputation. It presents the magnitude and direction of change in insight according to diagnosis and capacity at follow-up. On the left of Fig. 4 are the box plots for patients in the diagnostic groups when capacity was not regained; on the right-hand side for patients who did regain capacity. Table 3 shows the associations (crude and adjusted) between change in insight, capacity and diagnosis. Significant associations exist between change in insight and regaining capacity (p<0.001 crude) and between change in insight and diagnostic group (p=0.002 crude). The univariate association between diagnostic group and regaining capacity (Table 2) suggests the possibility that these two variables may confound each other with regard to their effect on change in insight, so both have to be included in the model. Both associations remain significant.

Fig. 4.

Insight change : data box plot (without imputation) and the means as predicted by a two way analysis of variance model with interaction (using imputation). The bars represent the mean insight change in each group as observed ; the crosses represent the mean insight change in each group as predicted by the interaction model; BPAD, bipolar affective disorder.

Table 3. Predicted means and observed means for change in insight in each diagnosis x capacity group of interest.

| Diagnostic×capacity group | Observed data | Model without interaction | Model with interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change in insight | Mean change in insight | 95% CI | Mean change in insight | 95% CI | |

| Schizophrenia and related disorder | |||||

| Not regaining capacity | 1.07 | 1.44 | (−1.01 to 3.89) | − 0.96 | (− 1.73 to 3.64) |

| Regaining capacity | 13.24 | 11.27 | (8.34-14.19) | 13.28 | (8.64-17.76) |

| BPAD-mania | |||||

| Not regaining capacity | 5.13 | 5.5 | (2.8, 8.8) | 4.82 | (0.83-8.82) |

| Regaining capacity | 16.18 | 14.9 | (12.4, 18.3) | 16.11 | (12.19-20.03) |

| Depression (unipolar or bipolar) | |||||

| Not regaining capacity | −0.40 | −4.3 | (− 8.9 to − 0.5) | −1.46 | (− 8.00 to 5.08) |

| Regaining capacity | 2.74 | 5.0 | (1.0-15.0) | 2.84 | (2.84-7.29) |

CI, Confidence intervals; BPAD, bipolar affective disorder.

We tested whether the association between regaining capacity and change in insight would be modified by diagnostic group as we expected a different behaviour in the patients with depression. Although the interaction is statistically classified as non-significant (p=0.14), the small sample size in the depression group (raw n=11) requires cautious interpretation. The interaction model predicts the mean values across the groups more accurately with regard to the observed data compared with the model where the interaction term is dropped (Table 3; Fig. 4). On the interaction model, patients with depression when regaining capacity are not predicted to gain insight in the marked way that patients with schizophrenia or BPAD-mania are (2.84 units compared with 13.28 and 16.11 respectively). Even in the model where the interaction term is dropped, there are anomalous features of depression. This is seen in Table 3, where patients who do not regain capacity have achieved a mean loss of insight at follow-up (−4.3 units).

Discussion

This study follows up patients who were admitted to psychiatric hospital without capacity to make treatment decisions. It seeks to clarify the associations of regaining capacity following approximately 1 month of treatment in hospital. We found that 37% of patients had regained capacity to make treatment decisions over this time. It is noteworthy how some variables such as years of service contact, years of education, cognitive function and total symptoms on admission did not differ much between patients regaining capacity and patients who do not. For some of these patients, 1 month of treatment (including treatment as simple care) may not have been long enough to regain capacity to make treatment decisions. For others, the incapacity to decide on treatment may be more enduring and both pre-exist the admission and post date the discharge by a considerable time.

There has been discussion of which legal ability (understanding, appreciation, reasoning), or combination of abilities, courts and clinicians should apply in the assessment of capacity (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1995; Vollmann et al. 2003). We found that change in each of the legal abilities was associated with regaining capacity. The restricted ranges in the MacCAT and the sample size limited analysis of how these changes may differ between ability and diagnostic group and so we are unable to add any specific empirically based guidance on how the legal abilities constitute capacity in this setting. It remains largely a matter of judgement. Appreciation and reasoning change a little more as a percentage of their MacCAT range than understanding. This might indicate their relatively greater importance in this setting. Our data do speak to the need to develop legal concepts and tests for appreciation and reasoning (or ‘use’ and ‘weigh’ in English legal language) which, compared with understanding, are underdeveloped.

Regaining capacity was predicted by diagnosis, affective symptoms and insight. As hypothesized, those with schizophrenia and related disorders had a lower chance of regaining capacity. This is consistent with clinical conceptualizations of schizophrenia and related disorders as mental disorders that carry a poorer prognosis. Psychotic symptoms at admission, however, do not have an association with maintained incapacity at follow-up. By contrast, and as hypothesized, affective symptoms at admission were associated with regaining capacity. The associations, however, are crude and the limited sample size prevents more sophisticated modelling of relationships. It is noteworthy that when old psychiatric classifications (e.g. those deriving from Kraepelin and Leonhard) are related to the concept of regaining mental capacity, associations are found. Kraepelin and Leonhard developed their classification systems within an organic frame of reference, whereas the concept of mental capacity has been developed within an ethical/legal frame of reference. Organic frames of reference, including their markers of prognosis, are traditionally construed as ethically neutral. One might speculate that implicit in the nosological efforts of Kraepelin and Leonhard were ethical considerations or, alternatively, that implicit within ethical/legal analyses of mental disorder are distinctions of a nosological kind. In any case, the results challenge strong separations between psychiatric and ethical/legal analyses of mental disorder and provide a different perspective on ongoing discussions regarding the validity of schizophrenia as a nosological concept (van Os & McKenna, 2003).

In cross-sectional studies in general psychiatric inpatient settings, insight is the clinical variable that associates most closely with capacity (Cairns et al. 2005; Owen et al. 2009). There are, however, difficulties – both conceptual and empirical – about this relationship in depression. Cutting has argued that the psychopathology of depression is paradoxical in relation to the insight concept because patients with severe depression can be morbidly sensitive to existential realities (e.g. suffering, guilt, death), which healthy individuals tend to pass over (Cutting, 1997). Similar points have been made by other psychopathologists (Ghaemi, 2007) and by experimental psychologists interested in the phenomenon of ‘depressive realism’ (Alloy & Abramson, 1979). Empirical studies of insight and depression have found that depression, even when severe, associates with relatively high insight scores and that, as mood gets lower, insight scores can indeed increase (Pini et al. 2001; Ghaemi & Rosenquist, 2004). In a previous study, in which we looked at the associations between capacity, insight and depression, we found that a wide range of insight scores (including those in the very good insight range) were compatible with incapacity to make treatment decisions in patients with depression.

In this follow-up study we have tested associations between change in insight, regaining capacity and diagnosis. Associations have been confirmed. Regaining capacity in depression has a different relationship with change in insight compared with regaining capacity in schizophrenia or mania. The study is underpowered to specify this difference but it provides evidence that the clinical construct of insight is not a good indicator of mental capacity for patients with depression. In patients with schizophrenia and BPAD-mania, loss of insight indicates movement away from capacity, whereas in patients with depression this is not clearly the case. To illustrate this, one patient with depression in the study scored high on insight when incapable to decide treatment and high at follow-up when capacity was regained. On admission the patient moderately participated in treatment and was aware of anxiety, low mood, paranoia and a ‘nervous condition ’ ; he thought these symptoms were preventing him from working or communicating effectively and were due to something wrong with his brain, which warranted medication. He thought that he wanted to die because he only existed and suffered and that whilst he hoped treatment might help reduce anxiety the decision meant little to him. At follow-up, the insight features were much the same but the mood state had improved markedly. The patient said about the treatment options: ‘I agree with what I said before but I now think the treatment options are not the same. I see the difference now’ ; and about the effect of mood on his thinking: ‘I was just thinking emotionally. I wasn’t thinking in sentences’.

To model the relationships between change in insight, regaining capacity and diagnosis more precisely would require a larger study – ideally with a longer follow-up, and multiple assessments in the same patient. We suggest that this study provides a stimulus for it.

This study has some limitations. It was carried out in an urban setting with high rates of psychosis (Kirkbride et al. 2006) admitted to hospital and may not generalize to other settings entirely. The considerable ethnic, cultural and socio-economic diversity in the setting also poses challenges for how information is fairly disclosed in the capacity assessment. We used the MacCAT structure with a context sensitive approach, whereby information disclosure was adjusted to the individual case in an informal manner. Some studies have used more formal techniques to simplify or enhance information disclosure and render it less dependent upon verbal ability. These studies have reported improvements in the understanding domain (Wong et al. 2000; Jacob et al. 2005; Jeste et al. 2009). Our study may have overestimated incapacity in cases where verbal communication was impeded. The marked changes in legal abilities across the follow-up, however, suggest to us that this was unlikely to have been a major problem. Follow-up only of the patients lacking capacity who participated in the study may have biased the outcomes as may loss to follow-up. Our analysis of participants and non-participants (see corresponding author for details) suggests that this first possible bias is not large and the loss of only 18% of the sample limits the second.

Mental disorder is an important testing ground for philosophical assumptions and commitments. There is a need for clarity of thought regarding philosophical commitments to autonomy among patients with psychiatric disorders. A key liberal philosophical commitment is the idea of a fundamental right to individual autonomy and the safeguarding of this right with the law of capacity and consent. There is progress in this direction but it is neither uniform nor entirely confident (Richardson, 2007). Apart from the considerable conceptual challenges that surround the study of decisional autonomy, one possible reason for this stuttering course is the lack of empirical data to moderate ideological antipathies between ‘libertarians ’ on the one hand and medical ‘paternalists ’ on the other when it comes to the treatment of people with mental disorder. We report some data using mental capacity, which we believe both supports some old psychiatric ideas about the clinical significance of the schizophrenia concept and the notion of insight and also should stimulate some new thinking about how depression can incapacitate decision making.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and the ward staff. ICS thanks Mike Kenward from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for discussions regarding missing data. The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. M.H. and A.S.D. are supported by the Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College London and The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology General. 1979;108:441–485. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.108.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS. Almost a Revolution: Mental Health Law and the Limits of Change. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: dangerous persons, moral panic, and the uses of psychiatry. Psychiatric Servives. 2003;54:441–442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patient’s competence to consent to treatment. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:1834–1840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp074045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. I : mental illness and competence to consent to treatment. Law & Human Behavior. 1995;19:105–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01499321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R, Maddock C, David AS, Hayward P, Richardson G, Szmukler G, Hotopf M. Prevalence and predictors of mental incapacity in psychiatric in-patients. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:379–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting J. Principles of Psychopathology. Oxford Medical Publications; Oxford: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell P. Treatment without Consent: Law, Psychiatry and the Treatment of Mentally Disordered People since 1845. Routledge; London: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN. Feeling and time: the phenomenology of mood disorders, depressive realism, and existential psychotherapy. Schizophernia Bulletin. 2007;33:122–130. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Rosenquist KL. In: Insight and Psychosis. Amador X, David AS, editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2004. Insight in mood disorder : an empirical and conceptual review; pp. 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Comparison of standards for assessing patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1033–1037. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob R, Clare ICH, Holland A, Watson PC, Maimaris C, Gunn M. Self harm capacity and refusal of treatment: implications for emergency practice. A prospective observational study. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2005;22:799–802. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.018671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Golshan S, Eyler LT, Dunn LB, Meeks T, Glorioso D, Fellows I, Kraemer H, Appelbaum PS. Multimedia consent for research in people with schizophrenia and normal subjects : a randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35:719–729. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Tarrant J, Lloyd T, Holloway J, Hutchinson G, Leff JP, Mallett RM, et al. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AeSOP study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:250–258. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Corin E, Jarvis GE. In: Insight and Psychosis: Awareness of Illness in Schizophrenia and Related Disorders. Amador X, David A, editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2004. Inside knowledge: cultural constructions of insight in psychosis; pp. 197–229. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhard K. The Classifcation of Endogenous Psychoses. Irvington Publishers, Inc; New York: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Okai D, Owen G, McGuire H, Singh S, Churchill R, Hotopf M. Mental capacity in psychiatric patients : Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:291–297. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.035162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen GS, David AS, Richardson G, Szmuker G, Hayward P, Hotopf M. Mental capacity, diagnosis and insight. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:1389–1398. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen GS, Richardson G, David A, Szmuker G, Hayward P, Hotopf M. Mental capacity to make decisions on treatment in people admitted to psychiatric hospitals: a cross sectional study. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39580.546597.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S, Cassano GB, Dell’Osso L, Amador XF. Insight into illness in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and mood disorders with psychotic features. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:122–125. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PsychCorp. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence - Manual. PsychCorp; Oxford, UK: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G. The European Convention and mental health law in England and Wales : moving beyond process. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2005;28:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G. Balancing autonomy and risk: a failure of nerve in England and Wales? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2007;30:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4:227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple impuation of missing values: update of ice. Stata Journal. 2005a;5:527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: update. Stata Journal. 2005b;5:188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Inference and missing data (with discussion) Biometrika. 1976;63:581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M, Constable G, Lopez-Ibor I, Kemp R, David AS. A comparative study of insight scales and their relationship to psychopathological and clinical variables. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:437–446. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Greenwood N, White S, Churchill R. Ethnicity and the Mental Health Act 1983. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:99–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Law Commission. Mental Incapacity. HMSO; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, McKenna P. [Accessed 23 January 2010];Does schizophrenia exist? Maudsley Discussion Paper, No. 12. 2003 http://www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/departments/?locator=525)

- Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, Liberman RP. Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: ‘ the drift buster’. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1993;3:221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmann J, Bauer A, Danker-Hopfe H, Helmchen H. Competence of mentally ill patients : a comparative empirical study. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:1463–1471. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JG, Clare ICH, Holland AJ, Watson PC, Gunn M. The capacity of people with a ‘mental disability’ to make a health care decision. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:295–306. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700001768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. WHO; Geneva: 1992. [Google Scholar]