Abstract

The nuclear pore complex (NPC) forms a permeability barrier between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Molecules that are able to cross this permeability barrier encounter different disordered phenylalanine glycine rich nucleoporins (FG-Nups) that act as a molecular filter and regulate the selective NPC crossing of biomolecules. In this review, we provide a current overview regarding the interaction mechanism between FG-Nups and the carrier molecules that recognize and enable the transport of cargoes through the NPC aiming to understand the general molecular mechanisms that facilitate the nucleocytoplasmic transport.

Keywords: Nuclear transport receptors, Nucleoporins, Nucleocytoplasmic transport, Multivalency, Intrinsically disordered protein

1. Introduction to the nucleocytoplasmic transport and the transport paradox

The exchange of biomolecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm takes place through the nuclear pore complex (NPC). It is typically considered that molecules below 40 kDa are able to freely diffuse through the NPC. Molecules above this molecular weight require the interaction with nuclear transport receptors (NTRs) to successfully cross through the NPC (see review in Ref. [1]). However, this size limit appears to be rather a gradient, than a strict cut-off limit [2,3]. NTRs, independent of being loaded with a cargo, are able to cross the permeability barrier of the NPC which is primarily formed by a group of proteins called FG-nucleoporins (FG-Nups). NPC crossing is an energy independent process but the directionality of the molecules being actively transported by NTRs depends on a RanGTP/GDP gradient formed between the nucleus and the cytoplasm [4]. RanGTP is more abundant in the nucleus, and can bind to import complexes, causing the cargo release in the nucleoplasm. Vice versa, when bound to export NTRs, RanGTP increases the affinity for export cargoes. The exported cargo can then be released from the export complex by RanGTP hydrolysis in the cytoplasm. The high concentration of RanGTP in the nucleus and of RanGDP in the cytoplasm is caused by the nuclear localization of RanGEF and RCC1, that exchange GDP for GTP, and the cytoplasmic localization of RanGAP, which hydrolyzes RanGTP into RanGDP. Cytoplasmic RanGDP is then recycled back to the nucleus by the NTR NTF2 (see review of RanGTP/GDP cycle in Ref. [5,6]).

The crossing of the NPC by NTRs with or without cargoes is a fast and selective process. Single molecule fluorescence microscopy experiments have enabled the measurement of the translocation time through the NPC of different cargoes by following the trajectories of labeled molecules (reviewed in Ref [7]). In this way, it was directly measured that molecules of different sizes can cross the NPC on millisecond timescales [8,9]. During this time, the NTRs interact with phenylalanine glycine motifs (FG-motifs) from the FG-Nups, on their way throughout the NPC barrier, undergoing multiple binding and unbinding events.

Using the latest published structure of the NPC [10], we can estimate the dimension of the NPC that is occupied by the FG-Nups of the central channel (Fig. 1A). We approximately measured a radius of 22.5 nm and a height of 24 nm for the inner ring of the NPC resulting in a calculated volume of around 38200 nm3. Then we calculate the number of FG, GF and F residues, which are motifs or residues that could engage in the binding to NTRs, present in the disordered region of the FG-Nups based on the known stoichiometry at the NPC [11]. The estimated concentration of FGs at the central NPC barrier is ~ 160 mM. If we then consider in addition the GF residues (~80mM) we would have a local concentration of binding sites of ~240 mM which increases up to ~260 mM if we consider the F residues only. Moreover, different in vitro equilibrium studies of FG-Nups and NTRs have reported high binding affinities from the nM the μM range [12–16]. As high affinity values are often associated with tight specific long-living complexes, it seems as a paradox that NTRs are not mainly stuck to the surface of the FG-Nup barrier, but can actually migrate through it very fast.

Fig. 1. Cartoon of the NPC and the main features of FG-Nups and NTRs.

A) Transversal section of the NPC structure with an estimated diameter of 45 nm and height of 24 nm of the central channel of the NPC (PDB:5IJN overlaid with a cryo-EM subtomogram average EMD-8087 [10]). B) Cartoon of the NPC indicating the location of FG-Nups from the cytoplasmic (red) central channel (blue) and nuclear basket (green). C) Example of FG-Nup containing a folded nuclear targeting and association domain and a disordered FG-motif rich region. The different FG-motifs are color coded and distributed through the FG-Nup sequence. D) Left, secondary structure of the HEAT repeat 5 of Importin-β (PDB:1QGK [46]). Each HEAT repeat is formed by two helices, an A-helix (cyan) and a B-helix (purple) which are oriented in an antiparallel manner. Right, structure of the ARM repeat 5 of Importin-α (PDB:1EE5 [55]). Structure showing the helix H1 (red), H2 (cyan) and H3 (purple), the last two having an antiparallel orientation as it is the case for the HEAT repeats. E) Cartoon representing an NTR composed of stacked HEAT forming a helicoidal structure. The pitch of the helicoid changes when it is bound to a protein by mildly modifying the angle of the repeats.

To further understand the nucleocytoplasmic transport, it is key to study the interaction mechanism between FG-Nups and NTRs. In this review, we provide an overview of the characteristic features of FG-Nups and NTRs with a focus on the latest studies on the interaction between FG-Nups and NTRs. This brings us closer to elucidating the nucleocytoplasmic transport process and to answer how fast and specific transport could be achieved. We will argue that this fundamental concept is largely robust and independent of what “model” one assumes for the structure of the actual, so far elusive permeability barrier.

2. Characteristic features of FG-nucleoporins and nuclear transport receptors

2.1. FG-nucleoporins, the molecular doorkeepers of the NPC

FG-Nups line the central channel of the NPC (Fig. 1B) and are composed of at least a folded domain, involved in anchoring the protein to the NPC, and an intrinsically disordered domain (IDD) protruding into the channel [17]. IDDs or whole intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs, here for simplicity all called IDP) are proteins that lack a stable secondary and tertiary structure and are disordered under native conditions [18,19]. Typically, these structural features are associated with a high net charge and a low hydrophobicity, which allows them to remain unfolded in solution under physiological conditions [19]. FG-Nups however, contain on average high mean hydrophobicity, which is comparable to the levels of hydrophobicity present in globular proteins. FG-Nups also contain a very low net charge, which is lower than in typical disordered domains [20,21]. Furthermore, FG-Nups contain multiple F residues across their sequence, many of which are in direct neighborhood to a G (Fig. 1C) [17,22]. Based on the different amino acids flanking the F residues different types of FG-motifs have been classified: FxFG, GLFG, PxFG, SxFG and FG are the most frequently seen FG-motifs but less abundant FG-motifs have also been identified in some FG-Nups [21,23,24]. In many cases, however, it still remains elusive to what extentthe nature of those repeats directly correlates to a specific function.

The primary sequence of the IDP region of FG-Nups does not have a high sequence conservation, which is often the case for disordered proteins that show a high amino acid substitution rate [25]. A bioinformatic study of FG-Nup sequences showed that the intrinsic disorder of FG-Nups is a conserved feature. However, FG-Nups also showed rapid evolution rates compared to other proteins. Another feature that seems to be conserved across FG-Nups is the hydrophilic inter-motif sequences of 10–20 amino acids present between the FG-motifs [23]. Those “linkers” also show a high amino acid substitution rate but maintain hydrophilic physicochemical properties [23].

The physicochemical properties of FG-Nups are directly related to a topic of central relevance to the field, i.e. how the actual permeability barrier is formed. The structure of the permeability barrier, which depends in part on the general question if FG-Nups interact with each other (are cohesive) or to what degree they rather repel each other (which could yield to brush type structures), still hasn’t converged to a single model that the whole field can easily agree on [17,26–33]. At the core of this problem is that the study of the barrier in situ is extremely challenging because it is a dynamic structure with a size below the resolution limit for conventional light microscopy. Several high resolution cryo-electron tomography 3D maps of the NPC have meanwhile been presented [10,34]. While most folded proteins can already be fitted into the maps with secondary structure resolution, the actual transport conduit shows up as a large empty channel, because the dynamic structures are averaged out and remain invisible to electron tomography technology. In light of a lack of technology to directly visualize the permeability barrier and the inability to purify entire functional NPCs, scientists have designed various elegant approaches to study how the permeability barrier might be formed in vivo. FG-Nups have shown to be able to adapt several single and macromolecular states, ranging from collapsed to extended states as single proteins in solution, as well as brushes and films when mounted on surfaces [26,28,35–37]. In addition, FG-Nups can undergo transitions to supramolecular assemblies giving rise to tough hydrogels, as well as amyloid fibers [21,38,39]. Based on these different studies a large set of models have been developed. In this review, we will not get into the discussion of these models, and rather point the reader to interesting reviews on this topic [20,40,41]. Instead, we will focus on the one thing that most models agree on: The required interaction between NTRs and FG-Nups to cross the selective barrier of the NPC and the roughly known concentration of FGs in the permeability barrier. We will first describe the structural features of different NTRs that are required for the successful NPC crossing followed by an overview of what we learned from recent structural and biochemical studies about the interaction between FG-Nups and NTRs.

2.2. Structural features required for NPC crossing

Binding to NTRs is the major route for cargoes to get across the NPC. To do so, NTRs can recognize and bind nuclear localization and nuclear export signals (NLS and NES respectively) from different cargoes. Many of these carrier proteins belong to the Importin-β/β-karyopherin superfamily (for review see Refs. [42,43]). Members of this superfamily contain an overall high structural similarity but low, between 15 and 20%, sequence identity [44]. β-karyopherins like the import receptor Importin-β and Transportin or the export receptor CRM1 are composed of a tandem series of HEAT repeats (reviewed in Ref. [45]). HEAT is an acronym that comes from the different proteins where this motif was originally found: Huntingtin, elongation factor 3, the A subunit of the protein phosphatase 2A and the kinase TOR1. Each HEAT motif is composed of approximately ~30-40 amino acids that form two amphiphilic α-helices (A-helix and B-helix) (Fig. 1D) with one side containing hydrophobic residues and the other side being enriched in hydrophilic amino acids. Both helices are linked by a turn and oriented in an antiparallel manner so that the hydrophobic surfaces of each helix are facing each other [46,47]. The tandem of HEAT repeats form a solenoid structure which contains the A and B helices arranged in the concave and convex surfaces respectively. This structural HEAT repeat composition provides the proteins with different levels of structural elasticity [48] which enables the NTRs to adopt different conformations resulting in curvature changes so that the solenoid adopts a helicoidal structure [42,49] (Fig. 1E). These structural changes have been reported to vary depending on the binding partner the karyopherin is bound to. For example, the level of compaction of NTRs like Importin-β increases when bound to the auto-inhibitory binding domain of Importin-α (IBB) when the import complex Importin-β/Importin-α/cargo is formed [46]. Structural studies have revealed that the binding of RanGTP to Importin-β also causes a conformational change in the helicoidal structure that inhibit the binding to Importin-α or cargoes by an allosteric mechanism [46,50]. The exportin CRM1 also undergoes a conformational change upon binding to RanGTP, in this case the conformational change upon RanGTP binding is required for the formation of the export complex. All these structural studies highlight the ability of NTRs to adapt and change the pitch of the helicoid upon binding to the different binding partners. It has been speculated that this structural rearrangements of the helicoid could store energy and would allow highly specific high energy interactions and at the same time due to the high level of flexibility it enables big structural changes in the helicoid with small movements of the repeats [42,51]. In addition to these conformational changes, NTRs have also been shown to undergo structural fluctuations in which the level of exposed hydrophobic protein surface fluctuates reversibly depending on the composition of the medium, having a larger exposed hydrophobic surface in a hydrophobic environment [52]. This structural “breathing” may be useful to adapt to the different environments that the NTRs encounter i.e. a more aqueous in the cytoplasm and more hydrophobic in the transport conduit of the NPC.

A different example of an Importin molecule that crosses the NPC and is formed by stacked consecutive α-helical repeats is Importin-α. Importin-α recognizes and binds to the NLS from the cargoes functioning as an adaptor protein between the cargo and Importin-β. Importin-α is formed of consecutive armadillo repeats (ARM) [53]. ARM repeats consist of three α-helices (H1, H2 and H3) (Fig. 1D) where helices H2 and H3 are placed in an antiparallel manner, as it is the case for the A-helix and B-helix of the HEAT repeats, and the helix H1 is placed slightly perpendicular to H2 and H3. As for stacked HEAT repeats, the stacking of different ARM repeats form a solenoid structure in which the concave surface is involved in ligand binding [54,55]. ARM and HEAT repeats contain seven highly conserved hydrophobic residues that form the hydrophobic core of the repeat (for a comparative review between HEAT and ARM repeats see Ref. [56]). Nevertheless, not all the molecules that have the ability to cross the NPC are formed of solenoids forming helicoidal structures and are part of the β-karyopherin superfamily. The NTR nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2) for example is a key component of the nucleocytoplasmic transport required for transport of RanGDP to the nucleoplasm [57,58]. NTF2 is formed by two homo-dimers containing a bent β-sheet and three α-helices, one longer and two shorter ones [59]. The hydrophobic cavity formed between the homo-dimers forms in combination with its neighboring surface the interaction interface between NTF2 and RanGDP.

Despite the structural similarities or differences within NTRs, all transport receptors have the common ability to cross the NPC with a cargo by interacting with the FG-motifs of the FG-Nups located at the NPC. In the following sections, we will focus on describing the interaction mechanism between FG-Nups and NTRs and its implication in the context of the nucleocytoplasmic transport.

3. Interaction between FG-Nups and NTRs

3.1. FG-Nup NTR interaction, multiple sites with multiple strengths

Over the years numerous crystal structures of different NTRs with short peptides containing FG-motifs have revealed many structural details of the interaction between FG-Nups and NTRs. For example, it has been shown that Importin-β has at least two main hydrophobic FG binding pockets between the A-helix of HEAT repeat 5 and 6 and of 6 and 7 that bind to FxFG peptides [60] (Fig. 2A). The binding groove formed by the HEAT repeat 5 and 6 has also been crystallized bound to a peptide containing GLFG motifs [61]. Due to the structural features of many NTRs, of stacked repeats, there are multiple binding groves available to bind with FG-Nups. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have shown that FG peptides engage with binding sites in agreement with previous X-ray crystallographic results and have in addition identified at least 6 more possible FG-motif binding sites in Importin-β [62], highlighting the multivalent nature of the interaction between FG-Nups and NTRs. Atomic force microscopy measurements of Nup153 and Importin-β showed that different binding pockets of the NTRs have different affinities for FG-Nups [63]. Moreover, there is also evidence that the conformational plasticity of NTRs can tune the interaction strength to FGs. The crystal structure of Importin-β bound to RanGTP and an FG peptide indicated that the structural changes caused in Importin-β upon RanGTP binding induced the movement of the A-helix from the HEAT repeat 5. This may facilitate the release of the FxFG peptide from the binding groove [60]. This effect on the FG binding to Importin-β/RanGTP complex was also observed by single-molecule force measurements [63]. These observations form the basis for a model in which RanGTP can facilitate Importin-β release from the NPC [33].

Fig. 2. Structures of NTRs bound to FG-motifs.

A) Crystal structure of Importin-β (grey cartoon) bound to an FxFG motif (red) in between the HEAT repeats number 5–6 and 6-7 (PDB:1F59 [60]). B) Structure of NTF2 dimer (grey) bound to an FxFG peptide (red), the FxFG peptide binds to the hydrophobic groove formed in the binding interface between the NTF2 monomers (PDB:1GYB [57]). C) Crystal structure of CRM1/RanGTP (grey/light grey) bound to a 117 amino acid long C-terminal sequence of Nup214 (red). Nup214 wraps around the outer surface binding at different hydrophobic pockets connecting the C-and the N-terminal site of CRM1 (PDB:5DIS [66]).

Not only NTRs formed out of stacked repeats are able to bind with FG-Nups. In the case of NTF2, it has been shown that the successful import of RanGDP into the nucleus was dependent on the ability of NTF2 to interact with FxFG containing nucleoporins [57]. The crystal structure of NTF2 with a short FxFG peptide showed that both Fs were buried in the hydrophobic groove formed between the two NTF2 monomers [64] (Fig. 2B). Further NMR studies confirmed the data obtained by X-ray crystallography and indicated an additional secondary FxFG binding site [65].

More recently, Port et al. showed a crystal structure of the exportin CRM1 bound to RanGTP and a 117 amino acid long disordered Nup214 [66]. Here, the C-terminal region of Nup214 appeared bound to the outer convex surface of CRM1 and it binds to the NTR with three FG regions in different hydrophobic pockets of CRM1 [66] (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, these FG regions interact with the N- and the C- terminal sites of CRM1 when bound to RanGTP and the authors suggested that this may be a mechanism of stabilizing CRM1/RanGTP export complex in a closed conformation and that Nup214 may be acting as a molecular clamp [66]. It is remarkable that the structure of Nup214 bound to CRM1/RanGTP showed high quality electron density in the FG-Nup binding sites. Notably, the structures did not reveal substantial secondary structure in the Nup, and it remains up to investigation, if the crystallization process trapped a specific state, or if indeed these regions lock specifically onto CRM1. Independent biochemical studies from different groups have indicated a possible different behavior of CRM1 export complexes compared to other NTR complexes when it comes to FG-Nup binding. In one of the studies the permeability properties of FG-Nup hydrogels, which have been formed under certain in vitro experimental conditions, for different NTRs and NTR complexes was tested [39]. Hydrogels formed of Nup214 showed that the complex of GFP-CRM1-NES bound to RanGTP penetrated the hydrogel minimally and the signal was mainly detected on the gel surface. In contrast, a deeper penetration of GFP-CRM1 alone or CAS/GFP-Importin-α bound to RanGTP was observed [39]. This would be in agreement with previous reports that suggested that Nup214 is a terminal binder for the CRM1 export complexes [67]. Moreover, similarly to the crystal structure of Nup214 and CRM1/RanGTP, the yeast homolog of Ran-binding protein RanBP3, Yrb2p that mediates the formation of export complexes also showed a similar binding with Xpo1p, the yeast homolog of CRM1, where two FG regions where also found to be bound to the N- and the C-terminal sites in the crystal structure [66,68]. Related to the export complex, it has also been shown that CRM1/NES/RanGTPbound to Nup358/RanBP2 can form a complex in which 2 FG-motif regions which are around 200 amino acids apart appear to engage with CRM1, potentially reducing the flexibility of the FG-Nup [69].

3.2. Insights into the binding of dynamic FG-Nup NTR complexes

IDPs are highly dynamic proteins in solution that are populating an ensemble of multiple conformations, their flexibility is often used by nature to form highly dynamic complexes (see review in Ref. [70]). Multiple conventional methodologies are very useful studying strong static complexes but the characterization of weak transient interactions with fast dissociation rate constants (koff) are in some cases not easily detected.

Multi-parameter single-molecule FRET (Förster resonance energy transfer) (smFRET) is a highly sensitive fluorescent method that can investigate changes in distances and conformational dynamics of single molecules labeled site-specifically with a donor and an acceptor dye forming a FRET pair [71,72]. Any changes in the conformation that would lead to a change in the distance between the donor and the acceptor dyes can be monitored as a change in the efficiency of energy transferred from the donor to the acceptor dye. In addition, these measurements are also able to show if the complex under study is static (does not undergo any conformational change during the measuring time) or dynamic (multiple conformations take place during the measuring time leading to the detection of the average conformation). The smFRET study of the conformational state of FG-Nups shows that they are highly dynamic proteins [73]. Noteable, the average distance distribution of the disordered ensemble and the average dynamics were retained even when the FG-Nups were bound to the folded NTR, a phenomen also in agreement with furtherMD simulations and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [73,74]. It appears, that F residues of the FG-Nup necessary for the binding were preexposed on the surface and ready to bind the hydrophobic pockets of the NTR so that no major changes in the conformational ensemble of the FG-Nup are necessary to form a highly dynamic FG-Nup•NTR complex [73,74].

MD simulations of FxFG peptides binding to the hydrophobic groove between NTF2 monomers showed that not only the FG motifs bound NTF2 but also the spacer residues between the FG-peptide where able to interact transiently, possibly contributing to the binding of the neighboring FG-motif [75]. A notable finding from these MD simulations was also that the FG-motifs, while being bound to NTF2, showed some local motion along the binding site, which was described as sliding of the FG-motif at the NTF2 contact site. FG-motifs did not interact in a static defined position but had a high degree of motion while bound to the binding groove of NTF2 [75]. They also observed that FG-motifs sliding on the hydrophobic groove could slide out and then either slide back into the bound state or they would unbind from NTF2. With these results Raveh et al. proposed a slide-and-exchange mechanism of binding between FG-Nups and NTRs. In this slide-and-exchange mechanism the transition from a strongly interacting state into a weakly interacting state enables the hydrophobic pocket to be accessible for the return of an FG-motif from the weakly interacting state back into the strongly interacting state, or in other words, it enables easy displacement of an FG-motif by a different one [75].

3.3. Reconciling kinetics and equilibrium constants with nucleocytoplasmic transport time scales

The above described results highlight the multivalent nature of the binding between FG-Nups and NTRs, where multiple F residues can engage with different binding pockets of the same NTR and that binding of FG-motifs across the NTR surface is a common feature for FG-Nup NTR binding. Due to the formation of multivalent complexes most equilibrium measurements report on the avidity (KD,global) of the formed complex, which is the result of the combination of the binding strengths of the binding events that take place simultaneously by the different FG-motifs of an FG-Nup and the different hydrophobic pockets of the NTR. This shall not be confused with the affinity (KD,ind) which is here defined as the binding strength of a single binding event (single F to a single binding pocket).

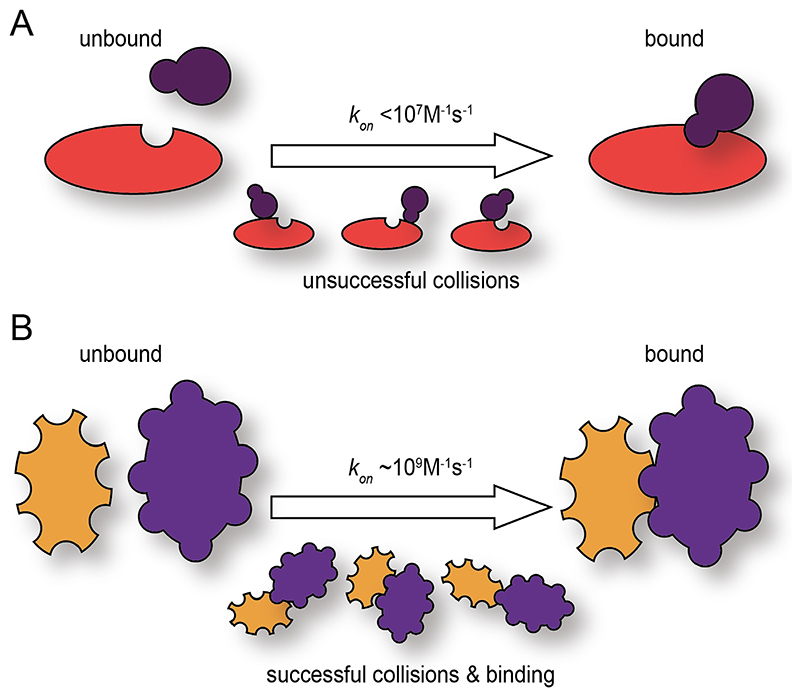

Many binding reactions between proteins cover a wide range of association rate constants (k on) (~104–107 M−1 s−1) [76]. Typically, fast protein-protein interaction values are frequently in the range of 106–107 M−1 s−1 [77]. This is because in order to achieve a successful binding, the right orientation between the binding partners is required and this may need several collisions between the proteins (Fig. 3A). Considering that KD =k off/k on one can calculate an upper limit for the k off,max. From this k off,max value the dissociation half-life, which is equal to 0.693/k off, for a bound protein complex can be calculated. In order to calculate the dissociation half-life of a FG-Nup/NTR complex, if we take 1 μM as the avidity of an average FG-Nup/NTR complex and a k on of 107 M−1 s−1 one would obtain a k off,max of 10 s−1 which corresponds to a dissociation half-life of ~70 ms. Considering that during the crossing of NTRs through the NPC multiple binding and unbinding events must take place, the calculated half-life is orders of magnitude higher than what it is required in order to be in agreement with the measured NPC crossing times of molecules (approximately 5 ms) [8,9].

Fig. 3. Cartoon representing the different association rate constants (k on) for different binding modes.

A) Representation of the typical bimolecular binding that requires proper orientation of the binding partners to achieve a successful collision and binding. B) Representation of a diffusion limited protein-protein binding where the binding partners contain a highly reactive surface in which any collision encounter leads to a successful binding event.

Stopped-flow spectroscopy association kinetic experiments enabled to measure k on values for different FG-Nups and NTRs near the diffusion limit (~109 M−1 s−1), a result in agreement with Brownian Dynamics (BD) simulation experiments [73]. Diffusion limited protein binding however, can only occur when both proteins are able to bind upon any collisional encounter (Fig. 3B). How is this possible? The orientation and association kinetics of binding proteins can be favored by long-range electrostatic interactions [78,79]. Association kinetic experiments at different ionic strength conditions enable the estimation of a basal k on, at infinite ionic strength where all the electrostatic interactions are shielded. The estimated k on basal for Nup153 and Importin-β was largely unaffected by the shielding of electrostatic forces. BD simulation experiments,where the electrostatic contribution during the simulation was excluded, agreed with the stopped-flow kinetic results. Therefore, the remaining explanation is the existence of a highly reactive surface of the FG-Nup, leading to a k on limited by the translational diffusion of the proteins where binding takes place everytime when the molecules come into contact. The FG-Nup/ NTR dissociation half-life us-ing the mea-sured k on in this case would be of 0.7 ms. Moreover, BD simulations also tested the effect on the k on in the absence of apolar desolvation, which accounts for the hydrophobic effect or the segregation of water molecules from the non-polar surfaces. When the hydrophobic effect was not considered in the simulations, the k on was affected by more than two orders of magnitude indicating a strong relationship between water solvation and fast binding between F residues of FG-Nups and hydrophobic pockets of the NTRs [73].

Due to the multivalent nature of the interaction between FG-Nups and NTRs, any measured k off will represent the dissociation rate constant of the entire molecule (k off,global of Fig. 4A), meaning that each individual binding site must be unbound for the complex to fall apart. Due to this, the measured k off for a single site (k off,ind of Fig. 4A) will be orders of magnitude faster than for the entire molecule [80]. Instead of using the measured avidity value of 1 μM we can also make use of the affinity value for a single site, which was suggested to be in the μM to mM range [15,73,74,81]. For an affinity of 1 mM and a k on of 109 M−1 s−1 the dissociation half-life would be of ~0. 7 μs, a value that would easily enable an NTR to cross the NPC undergoing multiple binding and unbinding events during a single transport event.

Fig 4.

Cartoon illustrating the differences between k off,global/k off,indiv. and K D,global/K D,single for molecules with different valency and cartoon of NTR crossing the NPC. A) Cartoon of 3 molecules (orange): a monovalent (molecule A), divalent (molecule B) and trivalent (molecule C) that bind to their binding partners (purple) that are also mono-,di- and trivalent. These three molecules contain the same binding sites and bind to the same motifs the only difference is the valency.

These findings indicate that the interaction of multiple low affinity binding events between individual FG-motifs and NTR binding pockets,with ultrafast kinetics, are able to form highly dynamic complexes that would allow the fast crossing of NTRs through the NPC (Fig. 4B).

4. Conclusions and future perspectives

The mechanistic understanding of the nucleocytoplasmic transport is limited by the complexity of the NPC and the lack of experimental methods to directly monitor the conformation and dynamics of FG-Nups in situ during nucleocytoplasmic transport.

In this review, we have summarized the main characteristics of the major players of the nucleocytoplasmic transport: FG-Nups and NTRs. We have briefly highlighted the main features that are required from both parts to perform their function. We have also summarized the latest results obtained in the field that increase the understanding of how fast yet specific transport across the NPC can be achieved. Multivalent interaction of multiple low affinity ultrafast binding and unbinding events taking place between the FG-Nups and the NTRs that allow the rapid exchange of FG-motifs from the different NTR binding pockets [73,75]. Despite the advances in the understanding of the nucleocytoplasmic transport many questions remain open, besides the fundamental question on how the permeability barrier is built. For example, how do sequence heterogeneity correlate with specific function, specific NTR interactions, or potentially spatially distinct mechanisms in the NPC is still not fully understood, and complicated by the effect, that the permeability barrier is highly robust, and functions even when multiple proteins are removed [82,83]. Thus several regulatory mechanism still remain to be discovered.

Another remaining open question derived from the previously described BD simulation experiments brings the attention to the study of the effect of the solvation by water, the most abundant molecule in the cytoplasm, which may play a crucial role in the interaction mechanism between FG-Nups and NTRs and other protein-protein interactions. It will also be interesting to elucidate what are the implications of the structural modulation of NTRs in the different stages of the nucleocytoplasmic transport. How could the modulation of the number and the type of binding grooves that are available to bind FG motifs, due to the conformational changes of the NTR, can affect the kinetics affecting the dwell times at the NPC. This could regulate the NTR release from the permeability barrier or could even modulate the interaction with different FG motifs in different FG-Nups that could even potentially shape different transport routes through the nuclear pore complex.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the fruitful discussions, comments and feedback from Lemke group. IVA and EAL acknowledge funding from the ERC grant SMPF v2.0.

Footnotes

We also assume that the k on for each motif molecules is equal and we exclude cooperative binding in our model. Because of this, the binding affinity (k D,single) and dissociation rate constant (k off,single) for each motif individually is the same. However, the k off,global for molecule A will be faster than for the divalent or the trivalent molecule because molecule B and C require that more motifs unbind from the entire molecule in order to achieve the dissociation of the complex. In this way, the k off,global increases (slower unbinding) with increasing valency. Due to the increase in the k off,global the molecules with higher valency will have a higher avidity (lower KD,global) even if the affinity of each motif (KD,single) is equal in all the molecules. B) Cartoon illustrating the crossing of an NTR through the NPC barrier interacting with multiple FG-motifs from different FG-Nups. Due to the low affinity of each binding pocket of the NTR and the fast binding and unbinding kinetics multiple binding and unbinding events can take place during a single NPC crossing. The arrows next to the FG-motifs indicate a FG leaving the NTR binding pocket (red) and a FG that will bind to the same pocket (green).

References

- [1].Adams RL, Wente SR. Uncovering nuclear pore complexity with innovation. Cell. 2013;152:1218–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Timney BL, Raveh B, Mironska R, Trivedi JM, Kim SJ, Russel D, et al. Simple rules for passive diffusion through the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 2016;215:57–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201601004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Popken P, Ghavami A, Onck PR, Poolman B, Veenhoff LM. Size-dependent leak of soluble and membrane proteins through the yeast nuclear pore complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:1386–1394. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kalab P, Weis K, Heald R. Visualization of a Ran-GTP gradient in interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Science (New York, NY) 2002;295:2452–2456. doi: 10.1126/science.1068798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Melchior F. Ran GTPase cycle: One mechanism – two functions. Curr Biol: CB. 2001;11:R257–R260. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yudin D, Fainzilber M. Ran on tracks–cytoplasmic roles for a nuclear regulator. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:587–593. doi: 10.1242/jcs.015289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Musser SM, Grunwald D. Deciphering the structure and function of nuclear pores using single-molecule fluorescence approaches. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:2091–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kubitscheck U, Grünwald D, Hoekstra A, Rohleder D, Kues T, Siebrasse JP, et al. Nuclear transport of single molecules. J Cell Biol. 2005;168 doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yang W, Gelles J, Musser SM. Imaging of single-molecule translocation through nuclear pore complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12887–12892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403675101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kosinski J, Mosalaganti S, von Appen A, Teimer R, DiGuilio AL, Wan W, et al. Molecular architecture of the inner ring scaffold of the human nuclear pore complex. Science. 2016;352:363–365. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ori A, Banterle N, Iskar M, Andres-Pons A, Escher C, Khanh Bui H, et al. Cell type-specific nuclear pores: a case in point for context-dependent stoichiometry of molecular machines. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:648. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ben-Efraim I, Gerace L. Gradient of increasing affinity of importin beta for nucleoporins along the pathway of nuclear import. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:411–417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Milles S, Lemke EA. Mapping multivalency and differential affinities within large intrinsically disordered protein complexes with segmental motion analysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:7364–7367. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pyhtila B, Rexach M. A gradient of affinity for the karyopherin Kap95p along the yeast nuclear pore complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42699–42709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tetenbaum-Novatt J, Hough LE, Mironska R, McKenney AS, Rout MP. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: a role for nonspecific competition in karyopherin-nucleoporin interactions. Mol Cell Proteom. 2012;11:31–46. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bednenko J, Cingolani G, Gerace L. Importin beta contains a COOH-terminal nucleoporin binding region important for nuclear transport. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wagner RS, Kapinos LE, Marshall NJ, Stewart M, Lim RY. Promiscuous binding of Karyopherinbeta1 modulates FG nucleoporin barrier function and expedites NTF2 transport kinetics. Biophys J. 2015;108:918–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Plodinec M, Lim RY. Nanomechanical characterization of living mammary tissues by atomic force microscopy. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1293:231–246. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2519-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Fink AL. Why are natively unfolded proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins: Struct, Funct Genet. 2000;41:415–427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::aid-prot130>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schmidt HB, Görlich D. Transport selectivity of nuclear pores, phase separation, and membraneless organelles. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:46–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schmidt HB, Görlich D, Kohler A, Bradatsch B, Bassler J, Hurt E, et al. Nup98 FG domains from diverse species spontaneously phase-separate into particles with nuclear pore-like permselectivity. eLife. 2015;4:51–62. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Patel SS, Belmont BJ, Sante JM, Rexach MF. Natively unfolded nucleoporins gate protein diffusion across the nuclear pore complex. Cell. 2007;129:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Denning DP, Rexach MF. Rapid evolution exposes the boundaries of domain structure and function in natively unfolded FG nucleoporins. Mol Cell Proteom. 2007;6:272–282. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600309-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cushman I, Palzkill T, Moore MS. Using peptide arrays to define nuclear carrier binding sites on nucleoporins. Methods. 2006;39:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Brown CJ, Takayama S, Campen AM, Vise P, Marshall TW, Oldfield CJ, et al. Evolutionary rate heterogeneity in proteins with long disordered regions. J Mol Evol. 2002;55:104–110. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-2309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lim RY, Fahrenkrog B, Koser J, Schwarz-Herion K, Deng J, Aebi U. Nanomechanical basis of selective gating by the nuclear pore complex. Science. 2007;318:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1145980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Frey S, Gorlich D. A saturated FG-repeat hydrogel can reproduce the permeability properties of nuclear pore complexes. Cell. 2007;130:512–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yamada J, Phillips JL, Patel S, Goldfien G, Calestagne-Morelli A, Huang H, et al. A bimodal distribution of two distinct categories of intrinsically disordered structures with separate functions in FG nucleoporins. Mol Cell Proteom. 2010;9:2205–2224. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000035-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Moussavi-Baygi R, Jamali Y, Karimi R, Mofrad MR. Brownian dynamics simulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport: a coarse-grained model for the functional state of the nuclear pore complex. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jovanovic-Talisman T, Tetenbaum-Novatt J, McKenney AS, Zilman A, Peters R, Rout MP, et al. Artificial nanopores that mimic the transport selectivity of the nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2009;457:1023–1027. doi: 10.1038/nature07600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Peters R. Translocation through the nuclear pore: kaps pave the way. BioEssays: News Rev Mol Cell Dev Biol. 2009;31:466–477. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Eisele NB, Labokha AA, Frey S, Gorlich D, Richter RP. Cohesiveness tunes assembly and morphology of FG nucleoporin domain meshworks – Implications for nuclear pore permeability. Biophys J. 2013;105:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lowe AR, Tang JH, Yassif J, Graf M, Huang WY, Groves JT, et al. Importin-beta modulates the permeability of the nuclear pore complex in a Ran-dependent manner. Elife. 2015:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].von Appen A, Kosinski J, Sparks L, Ori A, DiGuilio AL, Vollmer B, et al. In situ structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2015;526:140–143. doi: 10.1038/nature15381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Milles S, Lemke EA. Single molecule study of the intrinsically disordered FG-repeat nucleoporin 153. Biophys J. 2011;101:1710–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Eisele NB, Frey S, Piehler J, Gorlich D, Richter RP. Ultrathin nucleoporin phenylalanine-glycine repeat films and their interaction with nuclear transport receptors. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:366–372. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schoch RL, Kapinos LE, Lim RY. Nuclear transport receptor binding avidity triggers a self-healing collapse transition in FG-nucleoporin molecular brushes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16911–16916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208440109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Milles S, Huy Bui K, Koehler C, Eltsov M, Beck M, Lemke EA. Facilitated aggregation of FG nucleoporins under molecular crowding conditions. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:178–183. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Labokha AA, Gradmann S, Frey S, Hü Lsmann BB, Urlaub H, Baldus M, et al. Systematic analysis of barrier-forming FG hydrogels from Xenopus nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J. 2013;32302:204–218. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Walde S, Kehlenbach RH. The Part and the Whole: functions of nucleoporins in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lim RY, Huang B, Kapinos LE. How to operate a nuclear pore complex by Kap-centric control. Nucleus. 2015;6:366–372. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2015.1090061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Conti E, Muller CW, Stewart M. Karyopherin flexibility in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cook A, Bono F, Jinek M, Conti E. Structural biology of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:647–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.161529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].O’Reilly AJ, Dacks JB, Field MC, Brenner SE, Chervitz SA. Evolution of the karyopherin-β family of nucleocytoplasmic transport factors; ancient origins and continued specialization. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19308-e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yoshimura SH, Hirano T. HEAT repeats –versatile arrays of amphiphilic helices working in crowded environments. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:3963–3970. doi: 10.1242/jcs.185710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cingolani G, Petosa C, Weis K, Muller CW. Structure of importin-beta bound to the IBB domain of importin-alpha. Nature. 1999;399:221–229. doi: 10.1038/20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Raveh B, Karp JM, Sparks S, Dutta K, Rout MP, Sali A, et al. Slide-and-exchange mechanism for rapid and selective transport through the nuclear pore complex. PNAS. 2016;113(18):E2489–E2497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522663113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fournier D, Palidwor GA, Shcherbinin S, Szengel A, Schaefer MH, Perez-Iratxeta C, et al. Functional and genomic analyses of alpha-solenoid proteins. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79894-e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fukuhara N, Fernandez E, Ebert J, Conti E, Svergun D. Conformational variability of nucleo-cytoplasmic transport factors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2176–2181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lee SJ, Matsuura Y, Liu SM, Stewart M. Structural basis for nuclear import complex dissociation by RanGTP. Nature. 2005;435:693–696. doi: 10.1038/nature03578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Stewart M. Nuclear trafficking. Science. 2003:302. doi: 10.1126/science.1092863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yoshimura Shige H, Kumeta M, Takeyasu K. Structural mechanism of nuclear transport mediated by importin β and flexible amphiphilic proteins. Structure. 2014;22:1699–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Görlich D, Prehn S, Laskey RA, Hartmann E. Isolation of a protein that is essential for the first step of nuclear protein import. Cell. 1994;79:767–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Huber AH, Nelson WJ, Weis WI. Three-dimensional structure of the armadillo repeat region of β-catenin. Cell. 1997;90:871–882. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Conti E, Uy M, Leighton L, Blobel G, Kuriyan J. Crystallographic analysis of the recognition of a nuclear localization signal by the nuclear import factor karyopherin alpha. Cell. 1998;94:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Andrade MA, Petosa C, O’Donoghue SI, Muller CW, Bork P. Comparison of ARM and HEAT protein repeats. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:1–18. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bayliss R, Ribbeck K, Akin D, Kent HM, Feldherr CM, Gorlich D, et al. Interaction between NTF2 and xFxFG-containing nucleoporins is required to mediate nuclear import of RanGDP. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:579–593. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Stewart M. Insights into the molecular mechanism of nuclear trafficking using nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2) Cell Struct Funct. 2000;25:217–225. doi: 10.1247/csf.25.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Bullock TL, Clarkson WD, Kent HM, Stewart M. The 1.6 angstroms resolution crystal structure of nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2) J Mol Biol. 1996;260:422–431. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Bayliss R, Kent HM, Corbett AH, Stewart M. Crystallization and initial X-ray diffraction characterization of complexes of FxFG nucleoporin repeats with nuclear transport factors. J Struct Biol. 2000;131:240–247. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bayliss R, Littlewood T, Strawn LA, Wente SR, Stewart MG. GLFG and FxFG nucleoporins bind to overlapping sites on importin-beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50597–50606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Isgro TA, Schulten K. Binding dynamics of isolated nucleoporin repeat regions to importin-p. Structure. 2005;13:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Otsuka S, Iwasaka S, Yoneda Y, Takeyasu K, Yoshimura SH. Individual binding pockets of importin-beta for FG-nucleoporins have different binding properties and different sensitivities to RanGTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16101–16106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802647105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bayliss R, Leung SW, Baker RP, Quimby BB, Corbett AH, Stewart M. Structural basis for the interaction between NTF2 and nucleoporin FxFG repeats. EMBO J. 2002;21:2843–2853. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Morrison J, Yang JC, Stewart M, Neuhaus D. Solution NMR study of the interaction between NTF2 and nucleoporin FxFG repeats. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:587–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Port SA, Monecke T, Dickmanns A, Spillner C, Hofele R, Urlaub H, et al. Structural and functional characterization of CRM1-Nup214 interactions reveals multiple FG-binding sites involved in nuclear export. Cell Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hutten S, Kehlenbach RH. Nup214 is required for CRM1-dependent nuclear protein export in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;68 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00342-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Koyama M, Shirai N, Matsuura Y. Structural insights into how Yrb2p accelerates the assembly of the Xpo1p nuclear export complex. Cell Rep. 2014;9:983–995. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ritterhoff T, Das H, Hofhaus G, Schröder RR, Flotho A, Melchior F. The RanBP2/RanGAP1*SUMO1/Ubc9 SUMO E3 ligase is a disassembly machine for Crm1-dependent nuclear export complexes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11482. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sharma R, Raduly Z, Miskei M, Fuxreiter M. Fuzzy complexes: specific binding without complete folding. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:2533–2542. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Sisamakis E, Valeri A, Kalinin S, Rothwell PJ, Seidel CAM. Accurate single-molecule fret studies using multiparameter fluorescence detection. Method Enzymol. 2010;475:455–514. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)75018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Schuler B, Muller-Spath S, Soranno A, Nettels D. Application of confocal single-molecule FRET to intrinsically disordered proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;896:21–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3704-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Milles S, Mercadante D, Aramburu IV, Jensen MRb, Banterle N, Koehler C, et al. Plasticity of an ultrafast interaction between nucleoporins and nuclear transport receptors. Cell. 2015;163:734–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hough LE, Dutta K, Sparks S, Temel DB, Kamal A, Tetenbaum-Novatt J, et al. The molecular mechanism of nuclear transport revealed by atomic-scale measurements. eLife. 2015;4:1–23. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Raveh B, Karp JM, Sparks S, Dutta K, Rout MP, Sali A. Slide-and-exchange mechanism for rapid and selective transport through the nuclear pore complex. PNAS. 2016;113(18):E2489–E2497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522663113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Qin S, Pang X, Zhou HX. Automated prediction of protein association rate constants. Structure. 2011;19:1744–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Pollard TD, De La Cruz EM. Take advantage of time in your experiments: a guide to simple, informative kinetics assays. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1103–1110. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-01-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Spaar A, Dammer C, Gabdoulline RR, Wade RC, Helms V. Diffusional encounter of Barnase and Barstar. Biophys J. 2006;90:1913–1924. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.075507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Shammas SL, Travis AJ, Clarke J. Remarkably fast coupled folding and binding of the intrinsically disordered transactivation domain of cMyb to CBP KIX. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:13346–13356. doi: 10.1021/jp404267e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Kramer RH, Karpen JW. Spanning binding sites on allosteric proteins with polymer-linked ligand dimers. Nature. 1998;395:710–713. doi: 10.1038/27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Tu L-C, Fu G, Zilman A, Musser SM. Large cargo transport by nuclear pores: implications for the spatial organization of FG-nucleoporins. EMBO J. 2013;32:3220–3230. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Hulsmann BB, Labokha AA, Gorlich D. The permeability of reconstituted nuclear pores provides direct evidence for the selective phase model. Cell. 2012;150:738–751. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Strawn LA, Shen T, Shulga N, Goldfarb DS, Wente SR. Minimal nuclear pore complexes define FG repeat domains essential for transport. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ncb1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]