Abstract

Objective

Neonatal diabetes can result from mutations in the Kir6.2 or SUR1 subunits of the KATP channel. Transfer from insulin to oral sulfonylureas in patients with neonatal diabetes due to Kir6.2 mutations is well described, but less is known about changing therapy in patients with SUR1 mutations. We aimed to describe the response to sulfonylurea therapy in patients with SUR1 mutations and compare it with Kir6.2 mutations.

Research Design and Methods

We followed 27 patients with SUR1 mutations for at least two months after attempted transfer to sulfonylureas. Information was collected on clinical features, treatment before and after transfer and the transfer protocol used. We compared: successful and unsuccessful transfer patients, glycaemic control before and after transfer, and treatment requirements in patients with SUR1 and Kir6.2 mutations.

Results

23 patients (85%) successfully transferred onto sulfonylureas without significant side effects or increased hypoglycaemia and did not need insulin injections. In these patients the median HbA1c fell from 7.2% (IQR 6.6-8.2%) on insulin to 5.5% (IQR 5.3–6.2%) on sulfonylureas P=0.01. When compared to Kir6.2 patients, SUR1 patients needed lower doses of both insulin before transfer (0.4 vs 0.7u/kg/day, P=0.002) and sulfonylureas after transfer (0.26 vs 0.45 mg/kg/day, P=0.005).

Conclusions

Oral sulfonylurea therapy is safe and effective in the short-term in most patients with diabetes due to SUR1 mutations and may successfully replace treatment with insulin injections. A different treatment protocol needs to be developed for this group as they require lower doses of sulfonylureas than Kir6.2 patients.

Activating mutations in the Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits of the pancreatic potassium ATP channel (KATP), coded for by the genes KCNJ11 and ABCC8 are recently identified major causes of both transient and permanent neonatal diabetes (1–3). To date over 40 different heterozygous activating mutations have been reported in the KCNJ11 gene and are thought to account for between 25-55% of all cases of neonatal diabetes (1; 4–6). ABCC8 gene mutations may be either dominantly or recessively acting and approximately 40 different mutations have been reported in patients with neonatal diabetes (7; 8). Mutations in the ABCC8 gene are thought to account for ~10% of all cases of neonatal diabetes (9), and frequently cause TNDM (3; 9; 10).

In the normal pancreatic beta-cell metabolism results in increased cellular ATP, which binds to Kir6.2 to close the potassium channel, and hence depolarise the membrane and through increased calcium entry initiate insulin release (11; 12). Conversely, increased cellular ADP acts on SUR1 to open the channel and prevent insulin release (11). Activating mutations in these channels reduce sensitivity to the inhibitory actions of ATP and increase sensitivity to the stimulatory actions of ADP (2; 9). This causes the KATP channel to remain open, even in the presence of glucose, therefore preventing insulin release.

Sulfonylureas act by an ATP independent mechanism to close these channels, even when mutations are present (2; 9; 13). They result in insulin release and are therefore a potential treatment option in neonatal diabetes caused by mutations in these channels. The effective replacement of insulin treatment by high dose sulfonylureas has been shown to be successful in 90% of patients with Kir6.2 mutations and result in improved glycaemic control in a series of 49 patients described by Pearson et al.(14).

There is far less information on the use in patients with SUR1 mutations. Successful transfer from insulin to oral sulfonylureas has been described in 8 patients with neonatal diabetes due to SUR1 mutations (9; 10; 15–17). This study will examine the treatment response to sulfonylureas in a cohort of 27 patients with diabetes due to SUR1 mutations to identify if they can be used effectively and how their transfer and treatment differs from Kir6.2 patients.

Research Design and Methods

We studied an international series of 27 patients with ages ranging from 2 months to 46 years, with a genetic diagnosis of diabetes due to an ABCC8 gene mutation (or mutations), identified by sequencing in Exeter, UK. Genetic information on 23 of these mutations have been previously published (3; 7) (see Table 1). Most patients were referred from members of the International Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD). All of the patients attempted transfer from treatment with insulin to a sufficient dose of sulfonylureas, except two who were initially on no treatment and then treated with sulfonylureas when treatment was required. The dose of sulfonylurea was considered to be sufficient if equivalent to at least 0.6 mg per kilogram of body weight per day of glyburide was used; this is the highest reported dose required in previously published cases with patients with ABCC8 gene mutations (9). No other selection criteria were applied and all patients were included when there was outcome data for the attempted transfer. The observation period was at least 2 months after commencing sulfonylureas in all patients. Treatment details for 2 patients have been described previously (8; 15; 17).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients with SUR1 mutations, according to the success of treatment with sulfonylureas.

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 27) | Patients with Successful Sulfonylurea treatment (N = 23) | Patients with Unsuccessful Sulfonylurea treatment (N = 4) | P Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | N/A | V86G†, P45L/G1401R† (2), D209E† (3), T229I/V1523L†, Q211K†, V86A† (2), E1507G, V215I/V607M, E208K/Y263D†, R1380L§ (2), D212I‡ (3) T229I/T229I§, R1183W‡, L225P†, R826W and D209N. | F132L† (2), F132V†, and N72S† (mosaic). | NA |

| Classification: TNDM initial/ TNDM relapse/ PNDM/ non neonatal Diabetes – N | 2 / 6 / 17 / 2 | 2 / 6 / 13 / 2 | 0 / 0 / 4 / 0 | NA |

| Neurological features – N (%) | 6 (22) | 4 (17) | 2 (50) | 0.20 |

| Male sex – N (%) | 10 (37) | 8 (35) | 2 (50) | 0.61 |

| Birth weight – g | 2675 (1470 to 3870) | 2675 (1470 to 3500) | 2670 (2440 to 3870) | |

| Birth weight – SD score | -1.3 (-2.8 to 0.64) | -1.3 (-2.8 to -0.1) | -1.1 (-1.4 to 0.64) | 0.22 |

| Age at diagnosis – weeks | 6 (0 to 30) | 5 (0 to 30) | 17 (5 to 26) | 0.046 |

| Age at start of sulfonylurea treatment – yr | 7.8 (0.2 to 46.5) | 7.1 (0.2 to 46.5) | 14.9 (0.4 to 28.5) | 0.52 |

| Glycated haemoglobin before sulfonylurea treatment – % | 7.5 (5.0 to 21.0) | 7.1 (5.0 to 21.0) | 10.0 (7.5 to 12.0) | 0.11 |

| Insulin dose – U/kg/day | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.2) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.2) | 0.097 |

| Equivalent dose of glyburide – mg/kg/day | 0.28 (0.07 to 2.80) | 0.26 (0.07 to 2.80) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.12) | NA |

Data are medians (range) or % unless otherwise indicated. % are rounded up to the nearest whole number. NA denotes Not Applicable.

P values are for comparison of the patients with a successful switch with patients with an unsuccessful switch and were calculated by the Mann-Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data.

Reported in Ellard et al., 2007 (7),

Reported in Flanagan et al., 2007 (3)

Reported in Patch et al., 2007 (8).

Switch to sulfonylurea

For this study clinicians were provided with two recommended protocols for the transfer to the sulfonylurea glyburide (also known as glibenclamide) as used for Kir6.2 patients (see www.diabetesgenes.org and 14). One was for a rapid inpatient transfer where the glyburide dose was increased by 0.2mg/kg/day every day and the other for a slower outpatient transfer where the glyburide dose was increased by 0.2mg/kg/day every week. Both involved the gradual withdrawal of insulin as sulfonylurea was introduced depending on blood glucose. These protocols were modified by the treating clinicians. In 7 patients, as a result of physician choice, the recommended sulfonylurea, glyburide, was not used: 3 patients used gliclazide, 3 used glipizide and 1 used tolbutamide. For these patients equivalent doses of glyburide were calculated to allow inclusion of these results. This, as previously described (14), was done by expressing the sulfonylurea dose as a percentage of the maximum recommended dose (according to the British National Formulary 2007) and converting this to an equivalent dose of Glyburide.

Transfer was considered a success if the patient was able to completely stop insulin at any dose of sulfonylurea and was considered unsuccessful if insulin was still required with a dose of sulfonylurea equivalent to at least 0.6 mg/kg/day of glyburide.

Information was collected from clinicians regarding treatment before and after transfer, clinical features and details of the transfer. Clinical features were compared between patients who successfully transferred onto sulfonylureas and patients whose transfer was unsuccessful. The Fischer’s exact test for categorical data and the Mann Whitney U test for continuous data were used, as the data was not normally distributed. Glycaemic control before and after sulfonylurea therapy was compared by analysing the glycated haemoglobin values using the Wilcoxon rank test. Doses of insulin and sulfonylurea used in Kir6.2 and SUR1 patients who successfully transferred from insulin to sulfonylurea therapy were compared using the Mann Whitney U test. All tests were two-sided. Data are expressed as medians with ranges. Differences with a P value of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participating patients with parental consent given on behalf of children.

Results

Successful Transfer

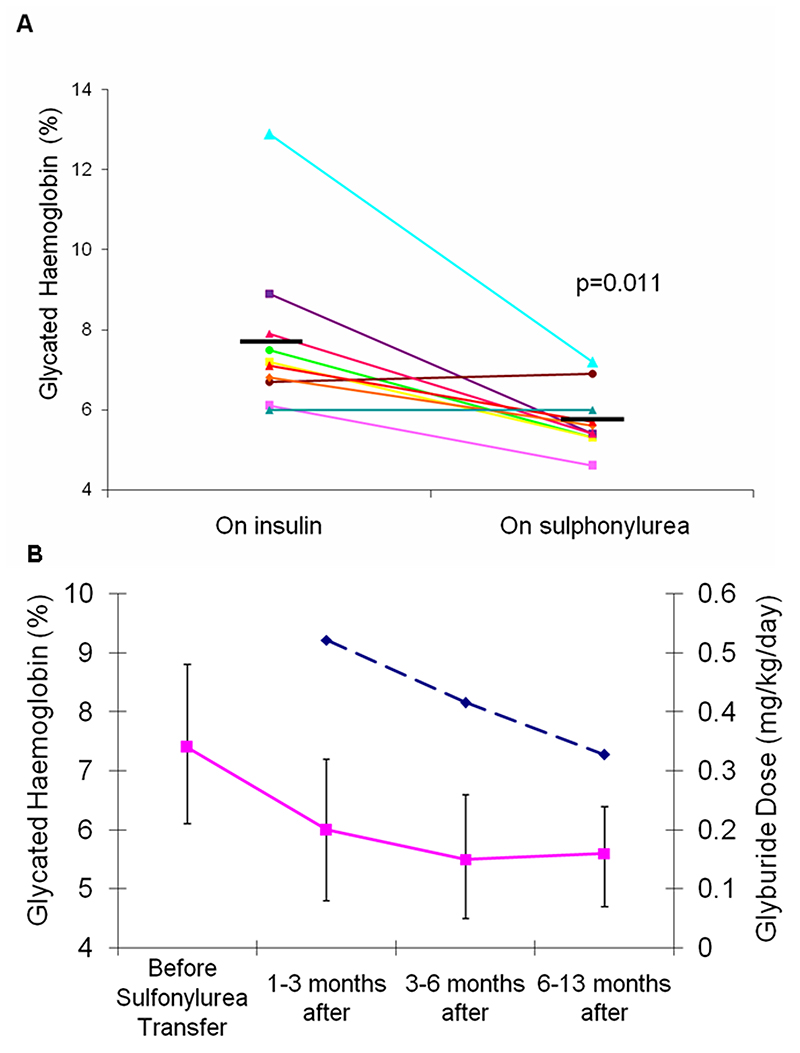

Of the 27 patients who attempted transfer onto sulfonylureas at an adequate dose, 23 (85%) were successful in being able to be treated with sulfonylureas alone. Successful transfer occurred with all the different sulfonylureas used suggesting the choice of agent was not critical. The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The ages of these patients at transfer ranged from 2 months to 46 years. All eight patients with transient neonatal diabetes were successfully treated with sulfonylureas: six were treated having relapsed and two were treated in the initial diabetic phase before they went into remission approximately 11 months after transfer. Four patients with neurological features successfully transferred onto sulfonylureas; all of these had developmental delay and one also had generalised seizures. Median HbA1c level dropped from 7.2% (IQR 6.6-8.2%) on insulin to 5.5% (IQR 5.3-6.2%) on sulfonylureas (p=0.011) (see Figure 1A) in the 10 patients in whom HbA1c measurements were available before and at least 4 weeks after transfer (median 15 weeks).

Figure 1. Initial reduction in glycated haemoglobin levels following transfer from insulin to sulfonylurea.

Panel A shows glycated haemoglobin values (HbA1c) for 10 patients (all those with full data) who had HbA1c measured when on insulin treatment and also at least 4 weeks after (median 15) weeks after successful transfer onto sulfonylurea medication. The thick horizontal lines represent the mean HbA1c with insulin and sulfonylurea treatment.

Panel B shows mean glycated haemoglobin values and sulfonylurea doses for 5 patients for whom data were available for at least 6 months after transfer onto sulfonylureas. The solid line represents mean glycated haemoglobin values. The bars show 95% confidence intervals and the dashed line represents the mean equivalent dose of glyburide in mg/kg/day.

In the 5 patients where follow up data was available for more than 6 months following transfer onto sulfonylurea, glycaemic control continued to improve despite decreasing sulfonylurea doses, with a mean drop in glycated haemoglobin levels of 1.86% (95% CI 0.2- 3.5%) from after transfer to the most recent value, see Figure 1B.

Unsuccessful transfer

Four patients were unable to completely stop treatment with insulin despite receiving an adequate dose of at least 1mg/kg/day of sulfonylurea (Table 1). Two of these patients with F132V and F132L mutations had increased C peptide levels following the transfer, but it was decided that the response was insufficient to discontinue insulin. Two of the patients had neurological features, including one patient who had severe developmental delay, epilepsy and neonatal diabetes (DEND syndrome) (2).

The clinical features of the patients according to whether transfer was successful are shown in table 1. The unsuccessful patients were diagnosed diabetic later: median age at diagnosis 17 weeks (range, 5 to 26 weeks) compared to 5 weeks (range, 0 to 30) (p = 0.046).

Side Effects

Three patients reported side effects during treatment with sulfonylureas. One patient had mild transitory diarrhoea on glyburide, which has been previously reported (15), but when transferred to tolbutamide, another sulfonylurea, no further side effects were experienced. Another patient had morning nausea whilst on glyburide, which may have been a side effect of the sulfonylurea therapy but resolved without discontinuing treatment. Transitory nausea has been previously reported in patients on glyburide (18). One severe hypoglycaemic episode (grade 3 in the ISPAD 2000 consensus guidelines) was reported in a patient, requiring a reduction in dosage of sulfonylureas. This patient also experienced abdominal discomfort, which started before the transfer, but may have worsened during treatment with glyburide. No other severe hypoglycaemic episodes were reported before or after the transfer onto sulfonylureas in any patients and no other side effects were reported.

Comparison with patients with Kir6.2 mutations who successfully transferred to sulfonylureas

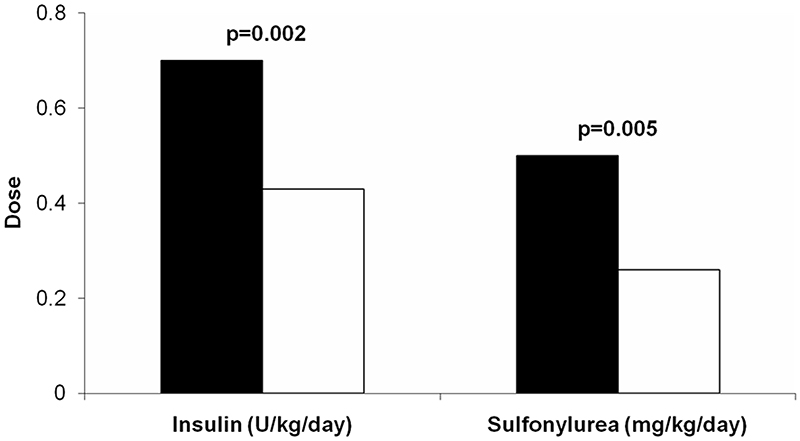

Our SUR1 patients who successfully transferred from insulin to sulfonylureas were compared to the previously published series of patients with Kir6.2 mutations published by Pearson et al. (14) (table 2). Comparison of treatment in SUR1 patients with Kir6.2 patients showed different treatment requirements (figure 2). The SUR1 patients needed a lower dose of insulin before transfer, median of 0.4u/kg/day (range, 0.2 to 0.9u/kg/day) compared to 0.7u/kg/day (range, 0.1 to 1.2u/kg/day) in Kir6.2 patients (p=0.002). SUR1 patients also required a lower dose of sulfonylurea after transfer, with a median of 0.26 mg/kg/day (range, 0.07 to 0.63mg/kg/day) compared to 0.45 mg/kg/day (range, 0.05 to 1.50 mg/kg/day) in Kir6.2 patients (p = 0.005). In four SUR1 patients the dose of sulfonylurea required was less than 0.1mg/kg/day, and these patients all had glycated haemoglobin levels on insulin treatment of less than 7%.

Table 2. A comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with SUR1 and Kir6.2 mutations who successfully transferred from insulin onto sulfonylureas.

| Characteristic | SUR1 Patients with Successful Sulfonylurea treatment (N = 21) | Kir6.2 Patients with Successful Sulfonylurea treatment* (N = 44) | P Value † |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological features – N (%) | 4 (19) | 6 (14) | 0.72 |

| Male sex – N (%) | 8 (38) | 24 (55) | 0.16 |

| Birth weight – g | 2700 (1470 to 3500) | 2740 (1871 to 3570) | 0.27 |

| Birth weight – SD score | -1.3 (-2.79 to -0.1) | -1.0 (-3.7 to 1.3) | 0.46 |

| Age at diagnosis – weeks | 5 (0 to 30) | 6 (0 to 152) | 0.52 |

| Age at start of sulfonylurea treatment – yr | 7.2 (0.2 to 46.5) | 6 (0.2 to 36.0) | 0.55 |

| Number of days to transfer | 3.5 (1 to 107) | 12 (0 to 170) | 0.12 |

| Glycated haemoglobin before sulfonylurea treatment – % | 7.1 (5.0 to 21.0) | 8.1 (6.3 to 13.1) | 0.062 |

| Insulin dose – U/kg/day | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.7 (0.1 to 1.2) | 0.002 |

| Equivalent dose of glyburide – mg/kg/day | 0.26 (0.07 to 2.8) | 0.45 (0.05 to 1.5) | 0.005 |

Data from the Kir6.2 patients is taken from reference 14. Summary data is given as median (range) unless otherwise indicated.

Data from Pearson et al. (14).

P values are for comparison of the patients with SUR1 mutations with patients with Kir6.2 mutations and were calculated by the Mann-Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data.

Conclusions

We found that the majority of patients (85%) with diabetes due to ABCC8 gene mutations could be successfully treated with oral sulfonylurea treatment even if they had previously been treated with insulin. As with Kir6.2 mutations (14) patients who transferred from insulin showed markedly improved glycaemic control and the good control was maintained over the first year. There was no evidence that despite the improved control that there was an increase in hypoglycaemia.

Lower doses of sulfonylureas were needed in the SUR1 patients compared to Kir6.2 patients. This meant that doses were closer to those used in Type 2 diabetes if calculated as dose corrected for body weight, while Kir6.2 mutations are considerably higher. It is likely that this reduced dose of sulfonylureas represented increased endogenous insulin secretion as the patients also required less insulin prior to transfer. Further support that the degree of endogenous insulin secretion determines the sulfonylurea dose came from the 4 patients with excellent control on insulin (HbA1c<7%), who all required very low doses of sulfonylureas (<0.1mg/kg/day). The lower sulfonylurea requirements suggest that a different protocol for transfer onto sulfonylureas is needed for SUR1 patients than for the Kir6.2 patients. We suggest that in SUR1 patients the gradual increase in glyburide dose is recommended during inpatient transfer should be 0.1mg/kg/day, which is half the increase /day used for Kir6.2 patients.

Particular care should be taken when attempting transfer in patients with evidence of existing endogenous insulin secretion. These patients are likely to already have good glycaemic control with HbA1c levels <7%, insulin doses <0.5u/kg/day and measurable C peptide. It is likely that these patients will need lower doses of sulfonylureas and they should be monitored closely to avoid hypoglycaemic episodes and an even slower increase in glyburide should be considered. Despite this some patients may still need high doses of sulfonylureas, particularly when they were transferred outside childhood.

The prevalence of side effects was low. There was only one severe hypoglycaemic episode reported in our cohort, but this is further evidence that caution and close blood glucose monitoring is needed during transfer to avoid hypoglycaemic episodes. Despite this, sulfonylurea use in this group appears to be safe, with the only other side effects reported being mild transitory diarrhoea, morning nausea and abdominal discomfort. Sulfonylurea doses of over 1mg/kg/day were used in this study with no reported adverse effects. Continued close follow up is recommended in view of the high doses being used.

Four patients in our study were unable to completely stop insulin and successfully transfer onto sulfonylureas. Patients who could not transfer were diagnosed with diabetes later in life than those who did transfer. This might suggest that in addition to the characteristics of the mutation, exposure before diagnosis of the pancreatic islet to untreated hyperglycaemia might alter the response to sulfonylureas. Two of the patients who could not transfer also have neurological complications, including one case of DEND syndrome, which is the most severe form of neonatal diabetes. Previous studies have shown that patients with neurological complications and Kir6.2 mutations are less likely to successfully transfer onto sulfonylureas (14). This can be explained by in vitro studies which found that mutations associated with neurological symptoms are less responsive to sulfonylureas as well as responding less to ATP (19; 20). Despite this, four patients in our study who had neurological features successfully transferred onto sulfonylureas. This indicates that presence of neurological complications in patients with diabetes due to SUR1 mutations should not act as a barrier to attempting sulfonylurea therapy.

Our study had some limitations. At present it is only possible to comment that the transfer to sulfonylureas is successful in the short term as we do not have follow-up data outside the immediate starting of sulfonylurea treatment. It is encouraging that the few patients with data over the first year maintained excellent glycaemic control despite a decreasing sulfonylurea dose over time. The transfer was performed in multiple centres throughout the world and hence it is not possible to ensure a standard protocol, as shown by the choice of medication varying. Finally it is not possible to be certain about the prevalence of hypoglycaemia before and after transfer as this was not formally studied using techniques such as 24 hr glucose monitoring.

We conclude that most patients with ABCC8 gene mutations can successfully transfer onto sulfonylureas. This treatment has been shown to be safe and achieve improved glycaemic control in the short term. Long-term follow up is needed in a large cohort of patients to see if trends in improved glycaemic control and decreased sulfonylurea dose continue. In comparison with Kir6.2 patients, lower doses of both insulin and sulfonylurea were found in SUR1 patients suggesting they have greater endogenous insulin secretion. We recommend that patients with diabetes diagnosed before 6 months of age should undergo genetic testing for ABCC8 gene mutations if they do not have a KCNJ11 mutation encoding Kir6.2, and if positive transfer onto oral sulfonylureas should be attempted, but using a different protocol to Kir6.2 patients.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2. Lower treatment doses are needed in patients with SUR1 mutations compared to patients with Kir6.2 mutations.

Black bars = Kir6.2 patients, White bars = SUR1 patients. Median insulin and sulfonylurea doses are shown for 21 patients with SUR1 mutations and 44 with Kir6.2 mutations who successfully transferred from insulin to sulfonylurea therapy.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the Wellcome Trust to M.R. We would also like to acknowledge funding from the Sir Graham Wilkins studentship to S.E.F. The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust and was supported by the European Union (Integrated Project EURODIA LSHM-CT-2006-518153 in the Framework Programme 6 of the European Community). A.T.H. is a Wellcome Trust Research Leave Fellow.

The authors thank all of the families for participating in this study. Our thanks go to the many referring clinicians.

References

- 1.Gloyn AL, Pearson ER, Antcliff JF, Proks P, Bruining GJ, Slingerland AS, Howard N, Srinivasan S, Silva JM, Molnes J, Edghill EL, et al. Hattersley AT: Activating mutations in the gene encoding the ATP-sensitive potassium-channel subunit Kir6.2 and permanent neonatal diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1838–1849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proks P, Arnold AL, Bruining J, Girard C, Flanagan SE, Larkin B, Colclough K, Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM, Ellard S. A heterozygous activating mutation in the sulphonylurea receptor SUR1 (ABCC8) causes neonatal diabetes. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1793–1800. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flanagan SE, Patch AM, Mackay DJ, Edghill EL, Gloyn AL, Robinson D, Shield JP, Temple K, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Mutations in ATP-sensitive K+ channel genes cause transient neonatal diabetes and permanent diabetes in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2007;56:1930–1937. doi: 10.2337/db07-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massa O, Iafusco D, D’Amato E, Gloyn AL, Hattersley AT, Pasquino B, Tonini G, Dammacco F, Zanette G, Meschi F, Porzio O, et al. KCNJ11 activating mutations in Italian patients with permanent neonatal diabetes. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:22–27. doi: 10.1002/humu.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaxillaire M, Populaire C, Busiah K, Cave H, Gloyn AL, Hattersley AT, Czernichow P, Froguel P, Polak M. Kir6.2 mutations are a common cause of permanent neonatal diabetes in a large cohort of French patients. Diabetes. 2004;53:2719–2722. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanagan SE, Edghill EL, Gloyn AL, Ellard S, H AT. Mutations in KCNJ11, which encodes Kir6.2, are a common cause of diabetes diagnosed in the first 6 months of life with the phenotype determined by genotype. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1190–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0246-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellard S, Flanagan SE, Girard CA, Patch AM, Harries LW, Parrish A, Edghill EL, Mackay DJG, Proks P, Shimomura K, Haberland H, et al. Permanent Neonatal Diabetes Caused by Dominant, Recessive, or Compound Heterozygous SUR1 Mutations with Opposite Functional Effects. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:375–382. doi: 10.1086/519174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patch AM, Flanagan SE, Boustred C, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. Mutations in the ABCC8 gene encoding the SUR1 subunit of the KATP channel cause transient neonatal diabetes, permanent neonatal diabetes or permanent diabetes diagnosed outside the neonatal period. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 9(s2):28–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babenko AP, Polak M, Cave H, Busiah K, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L, Vaxillaire M, Froguel P. Activating mutations in the ABCC8 gene in neonatal diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:456–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaxillaire M, Dechaume A, Busiah K, Cave H, Pereira S, Scharfmann R, de Nanclares GP, Castano L, Froguel P, Polak M. New ABCC8 mutations in relapsing neonatal diabetes and clinical features. Diabetes. 2007;56:1737–1741. doi: 10.2337/db06-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gloyn AL, Siddiqui J, Ellard S. Mutations in the genes encoding the pancreatic betacell KATP channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) in diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinism. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:220–231. doi: 10.1002/humu.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashcroft FM, Gribble FM. Tissue-specific effects of sulfonylureas: lessons from studies of cloned K(ATP) channels. J Diabetes Complications. 2000;14:192–196. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(00)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson ER, Flechtner I, Njolstad PR, Malecki MT, Flanagan SE, Larkin B, Ashcroft FM, Klimes I, Codner E, Iotova V, Slingerland AS, et al. Switching from insulin to oral sulfonylureas in patients with diabetes due to Kir6.2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:467–477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Codner E, Flanagan SE, Ugarte F, García H, Vidal T, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Sulfonylurea Treatment in Young Children With Neonatal Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007 Mar 2;:e28–e29. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masia R, De Leon DD, MacMullen C, McKnight H, Stanley CA, Nichols CG. A mutation in the TMD0-L0 region of sulfonylurea receptor-1 (L225P) causes permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus (PNDM) Diabetes. 2007;56:1357–1362. doi: 10.2337/db06-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanik J, Gasperikova D, Paskova M, Barak L, Javorkova J, Jancova E, Ciljakova M, Hlava P, Michalek J, Flanagan SE, Pearson E, et al. Prevalence of Permanent Neonatal Diabetes in Slovakia and Successful Replacement of Insulin with Sulfonylurea Therapy in KCNJ11 and ABCC8 Mutation Carriers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1276–1282. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malecki MT, Skupien J, Klupa T, Wanic K, Mlynarski W, Gach A, Solecka I, Sieradzki J. Transfer to sulphonylurea therapy in adult subjects with permanent neonatal diabetes due to KCNJ11-activating [corrected] mutations: evidence for improvement in insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:147–149. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proks P, Antcliff JF, Lippiat J, Gloyn AL, Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM. Molecular basis of Kir6.2 mutations associated with neonatal diabetes or neonatal diabetes plus neurological features. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17539–17544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404756101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trapp S, Proks P, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. Molecular analysis of ATP-sensitive K channel gating and implications for channel inhibition by ATP. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:333–349. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.