Abstract

Difficulties in applying emotion regulation (ER) skills are associated with depression and anxiety symptoms and are common targets of treatment. This meta-analysis examined whether improvements in ER skills were associated with psychological treatment outcomes for depression and/or anxiety in youth. A multivariate, random-effects meta-analysis was run using metafor in R. Inclusion criteria included: studies that were randomized-controlled trials of a psychological intervention for depression and/or anxiety in patients aged 14-24; peer reviewed; written in English; measured depression and/or anxiety symptoms as an outcome; and measured ER as an outcome. Medline, Embase, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL, and The Cochrane Library were searched up to 26 June 2020. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias 2.0 tool. The meta-analysis includes 385 effect sizes from 90 RCTs with total N=11,652. Psychological treatments significantly reduced depression, anxiety, emotion dysregulation (k = 13, Hedges’ g = 0.54, P<0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.30–0.78), and disengagement ER (k=83, g=0.24, 95% CI=0.15-0.32, p<.001); engagement ER also increased (k=82, g=0.26, 95% CI=0.15-0.32, p<.001). Improvements in depression and anxiety were positively associated with improved engagement ER skills, reduced emotion dysregulation, and reduced disengagement ER skills. Sensitivity considered study selection and publication bias. Longer treatments, group formats, and cognitive-behavioral orientations produced larger positive associations between improved ER skills and reduced symptoms. ER skill improvement is linked to depression and anxiety across a broad range of interventions for youth. Limitations of the current study include reliance on self-report measures, content overlap between variables, and inability to test the directionality of associations.

Keywords: emotion dysregulation, emotion regulation strategies, transdiagnostic, common factors

Introduction

Depressive and anxiety disorders most often begin in adolescence and young adulthood, before the age of 24.1 Depression and anxiety are common and disabling conditions that often co-occur,2–4 increasing the potential for mental health difficulties and suicidal behavior in adulthood if not treated.1,3–5 Given the substantial and sustained burden caused by these symptoms in young persons, it is critically important to identify effective psychosocial interventions to further advance treatment and prevention efforts. Equally important is the exploration of the specific components of psychological interventions that are associated with successful reduction in clinical symptoms.6 Here, we examined how three indices of emotion regulation (ER) skills were associated with changes in depression and anxiety symptoms following psychological interventions for youth and young adults aged 14-24.

In daily life, we implement ER skills to change the frequency, intensity, and duration of negative emotional experiences (e.g., reframing the impact of a poor grade).7 ER skills are also used to increase or maintain positive emotional experiences (e.g., celebration of a milestone with others). These skills can be intrapersonal, originating from within a person, and interpersonal, involving an interaction with others. Indeed, many emotions happen in a social context and can be regulated through others as much as our own selves.8 Skills can have both cognitive and behavioral components, such as physically avoiding an anxiety-provoking situation or using experiential avoidance to avoid unwanted thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations. Thus, ER skills represent a broad set of processes or strategies for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying our emotional experiences in the short-term and dynamically over time.7 From childhood to young adulthood, we are continuously diversifying our ER skills, learning from caregivers and interpersonal relationships,9 as higher-order cognition develops, and novel contexts are encountered.10–12 We even become willing to experience negative emotions for others in different interpersonal contexts (e.g., parenting, social relationships) to serve long-term hedonic or prosocial benefits.13 As adults, we start to exhibit more stable patterns of ER skills most frequently used and individual differences in how we respond to emotional experiences are linked to a range of interpersonal, psychological, and physical well-being indices.14–16 Existing research suggests that individual differences in intrapersonal and interpersonal ER skills are transdiagnostic factors that underlie the development and course of depression and anxiety disorders.17–20

Using the process model framework,7 mental disorders such as depression and anxiety are said to arise from failures to select and implement ER skills effectively. Indeed, evidence suggests that dysfunctional patterns in intrapersonal ER skills in youth and young adults are positively associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety cross-sectionally,18,21–23 and prospectively predict anxiety and depressive symptoms over time.24,25 Moreover, individual differences in interpersonal ER skills, such as becoming dependent on others or social settings to regulate one’s own emotions (e.g., through excessive reassurance or advice seeking)20,26 have been shown to predict depressive and anxiety symptoms in adults.19,27 When people exhibit several deficits in intrapersonal ER skills or use skills in a manner that is harmful, impulsive, and serves to reinforce the heightened experience of negative emotions, they are typically said to be experiencing emotion dysregulation, which is common to depressive and anxiety disorders.28–30 Similar to dysfunctional patterns in ER skills, the experience of emotion dysregulation is also positively associated with depressive and anxiety symptom severity.31–33 Thus, accumulating evidence suggests that individual differences in the ability to engage in intrapersonal and interpersonal ER skills may have a transdiagnostic role in the development and course of depressive and anxiety disorder symptoms.

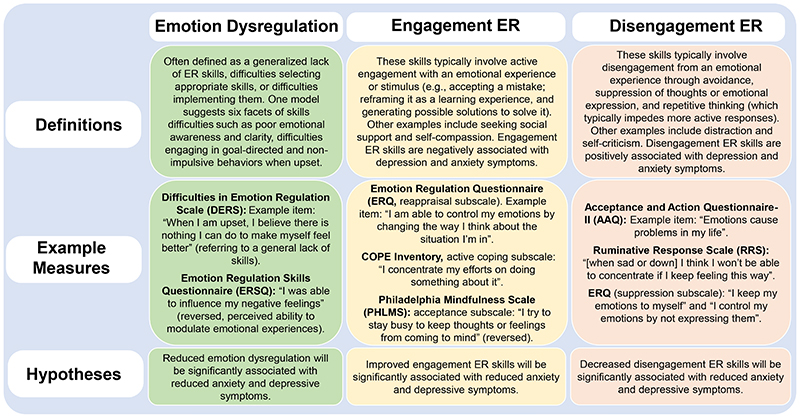

One of the challenges in studying ER skills is the wide range of skills identified and variability in their operational definition and assessment. The current integration was guided by previous reviews and focused on ER skills that have a substantial theoretical and empirical foundation as well as validated self-report measures (see Figure 1).34,38 We organized these ER skills into two broad classes which align closely to a two-factor structure used to evaluate their relationship with psychopathology.34,39 We define “engagement ER skills” as those that involve active engagement with an emotional experience or stimulus (e.g., acceptance, cognitive reappraisal, and problem-solving) and are negatively associated with psychopathology if used habitually. Alternatively, “disengagement ER skills” are those involving disengagement from an emotional experience or stimulus through avoidance, inhibition of thoughts or overt expression, or the use of repetitive thinking (e.g., avoidance, suppression, and rumination) and are positively associated with psychopathology if used habitually. To give an example, one can accept, or engage with the anxiety that comes with giving a presentation in front of an audience or suppress thoughts about its existence which inhibits an emotional experience. By accepting its existence (or the potential for its occurrence), it may allow one to then reduce of the feeling of anxiety though relaxation or other methods. We acknowledge that adapting skills to situational demands may be most important to mental wellbeing.40,41 However, contextual use of ER skills remains difficult to measure versus habitual ER skill use. In addition, given its association with depression and anxiety symptoms, we also incorporated measures of emotion dysregulation, because treatments that increase general abilities to regulate emotions may also support insights into the treatment of anxiety and depressive symptoms in young people.

Figure 1. Three ways of measuring improvements in ER over the course of psychological treatment in the present synthesis.

Note: A more detailed review, with additional examples of measures, can be found in the Supplementary Information. References corresponding to scales: DERS82, ERSQ83, ERQ16, COPE84, PHLMS85, AAQ86, and RRS70.

Evidence for ER skill improvements during treatments for depression and anxiety is already accumulating. Several reviews have argued that a range of psychological treatments with varied theoretical orientations improve intrapersonal ER skills in youth and adults with heterogeneous clinical presentations.37,38 This effect appears to be transdiagnostic across mental disorders and invariant to the type of psychological intervention used. In the most comprehensive review of the literature to date, 95% of studies (which largely focused on adult samples) found substantial decreases in disengagement ER skills and overall emotion dysregulation, regardless of the specific treatment protocol, the construct of ER examined, or the disorder targeted.38 Other research has demonstrated that improvements in ER skills during treatment are associated with positive treatment outcomes for a variety of evidence-based psychological treatments, including Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and Emotion Regulation Therapy, among others.42–48 These results suggest that distinct psychological treatments can produce meaningful changes in intrapersonal ER skills, and that these changes may represent a core process across psychological disorders likely to produce change when targeted in treatment.49 There is also great potential in examining changes in interpersonal ER skills during treatment, given their importance in maintaining depressive and anxiety symptoms.19,20 While ER skills training may be a key factor to consider in treatment outcomes for depressive and anxiety disorders, few of these studies or reviews have considered multiple indices of ER for enhanced specificity. Moreover, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have less often examined whether improvement in ER skills are associated with depression and anxiety treatment outcomes in young persons.

The present systematic review investigated whether improvements in ER skills are associated with improvements in symptoms in the psychological treatment of anxiety and depression in young persons aged 14-24. We defined anxiety and depression as dimensional symptom constructs, rather than categorical diagnoses, as assessed by validated self-report measures over time. Measures of depression (e.g., Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale) assessed symptoms of depressed mood and a loss of interest or pleasure in activities, along with difficulties sleeping, fatigue, diminished concentration, and suicidal thoughts. Measures of social and/or generalized anxiety (e.g., Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale) assessed feelings of worrisome thoughts that tend to recur intrusively leading to experiential avoidance, social anxiety, along with tension and physical changes in the body. Some measures assess both symptoms of depression and anxiety (e.g., Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale). Search criteria were designed to be broad to capture as many interventions as possible that were targeted to this age group. We hypothesized that improvements in ER skills (i.e., decreased emotion dysregulation, decreased disengagement ER skills, and increased engagement ER skills) would be positively associated with the reduction of depression and anxiety symptoms in young persons. Following the examination of overall effects, we completed sensitivity analyses to further understand in what contexts, and for whom, under which this association is evident or enhanced. Individual ER skills were also investigated when sufficient information was available. Notably, these research questions and methodology were informed by youth with lived experience, whose recommendations meaningfully shaped this synthesis.

Results

Search Results and Characteristics of Selected Studies

As depicted in Figure 2, our initial search garnered 10,804 results once 7,044 results were removed as duplicates. Following title and abstract screening by two independent team members, 3,044 articles were selected for full-text review, and ultimately 143 articles met inclusion criteria and were assessed for data extraction. Data were extracted and primary analyses were conducted using 385 effect sizes from 88 included studies. Two of these studies contained secondary studies, for a total of 90 RCTs (N=11,652). Half of these RCTs (50%) were from countries where English was not a primary language. As seen in Figure 3, risk of bias ratings indicated that 85% of RCTs had low or some concerns. Primary findings were compared to 55 non-RCTs (N=3,224) that met criteria for inclusion but were analyzed separately. A summary of study characteristics for RCTs and non-RCTs is presented in Table 1, with study reference lists found in the Supplementary Information. As further explained in the Supplementary Information, we were unable to locate any studies that utilized interpersonal ER measures; we highlight other associated findings there, while focusing exclusively on intrapersonal ER skills in the main text.

Figure 2. PRISMA figure depicting the flow of studies in the present synthesis using a comprehensive search strategy.

Note: Two of the 88 studies in the included RCTs section had an additional study reported within the respective paper. Hence, there are a total of 90 RCTs.

Figure 3. Overall and domain-specific Risk of Bias ratings for each of the 90 RCTs included in the meta-analysis.

Note: Only the 90 RCTs received ROB ratings as most of the non-RCTs were single-arm designs and would automatically be rated as having “some concern”. Overall ratings are provided with the study characteristics of RCTs in Supplementary Table 1. A full breakdown of ROB ratings per study can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 1. Summary of Study Characteristics for RCTs (n=90) versus non-RCTs (n=55) studies.

| Variable | Categories | RCT | Non-RCT | Chi-Square (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 1-50 | 31 (34.4%) | 37 (67.3%) | χ 2=14.78(3), p=.002 |

| 51-100 | 30 (33.3%) | 9 (16.4%) | ||

| 101-200 | 19 (21.1%) | 6 (10.9%) | ||

| >201 | 10 (11.1%) | 3 (5.5%) | ||

| Mean age (or median if range used) | 14-17.9 | 32 (35.6%) | 27 (49.1%) | χ 2=2.15(2), p=.34 |

| 18-21.9 | 34 (37.8%) | 18 (32.7%) | ||

| 22-24.9 | 21 (23.3%) | 10 (18.2%) | ||

| Percent Female | 0-40% | 0 | 4 (7.3%) | χ 2=6.70(3), p=.08 |

| 41-60% | 19 (21.1%) | 11 (20.0%) | ||

| 61-80% | 37 (41.1%) | 23 (41.8%) | ||

| 81-100% | 30 (33.3%) | 16 (29.1%) | ||

| Type of Control | Active (i.e., treatment as usual) | 44 (48.9%) | 8 (14.5%) | χ 2=1.86(2), p=.39* |

| Inactive (i.e., waitlist) | 37 (41.1%) | 8 (14.5%) | ||

| Both (i.e., study had multiple arms) | 9 (10.0%) | 0 | ||

| None (i.e., single-arm study)* | 0 | 39 (70.9%) | ||

| Treatment Length | 1 session | 8 (8.9%) | 1 (1.8%) | χ 2=11.15(4), p=.02 |

| 2-6 sessions | 35 (38.9%) | 17 (58.2%) | ||

| 7-10 sessions | 35 (38.9%) | 18 (32.7%) | ||

| 11-14 sessions | 9 (10.0%) | 10 (18.2%) | ||

| >14 sessions | 3 (3.3%) | 8 (14.5%) | ||

| Sample Type | High School | 23 (25.6%) | 10 (18.2%) | χ 2=17.23(3), p=.002 |

| College | 53 (58.9%) | 18 (32.7%) | ||

| Outpatient | 8 (8.9%) | 12 (21.8%) | ||

| Community | 10 (11.1%) | 15 (27.3%) | ||

| Other/Special (Inpatient, Military, Correctional) | 1 (1.1%) | 3 (5.5%) | ||

| Modality of Intervention | Individual | 33 (36.7%) | 11 (20.0%) | χ 2=9.62(3), p=.02 |

| Group | 46 (51.1%) | 38 (69.1%) | ||

| Online/Blended | 11 (12.2%) | 7 (12.7%) | ||

| Family | 0 | 3 (5.5%) | ||

| Therapeutic Orientation | Cognitive Training (CBM, ABM, etc.) | 15 (16.7%) | 1 (1.8%) | χ 2=14.96(3), p=.006 |

| CBT or CBT-based (or PST, IPT) | 35 (38.9%) | 17 (30.9%) | ||

| Acceptance/ER-based (ACT, ABBT, DBT, ERT) | 15 (16.7%) | 12 (21.8%) | ||

| Mindfulness-based (MBCT, MSBR) | 22 (24.4%) | 20 (36.4%) | ||

| Other (Psychodynamic, mentalization, UP, family) | 3 (3.3%) | 8 (14.5%) |

Note: *One row was excluded from categorical analyses as it produced a structural zero. All other zeroes and low values were observed rather than expected, and the large sample of studies (N>120) made Chi-Square approximation acceptable. Some information was unavailable: Mean age/median (3 RCTs), Percent female (4 RCTs; 1 non-RCT), Treatment Length (1 non-RCT, where treatment lengths varied per person). Percent was calculated inclusive of these missing values. Some studies had multiple arms with different therapeutic orientations, therefore sums may be more than the total number of unique studies. ABBT = Acceptance-based behavior therapy; ABM = Attention bias modification; ACT = Acceptance and commitment therapy; CBM = Cognitive bias modification; CBT = Cognitive-behavioral therapy; DBT = Dialectical behavior therapy; ER = Emotion regulation; ERT = Emotion regulation therapy; IPT = Interpersonal psychotherapy; MBCT = Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; MSBR = Mindfulness-based stress reduction; PST = problem solving therapy; UP = Unified Protocol.

The majority of RCTs delivered between 2 and 10 intervention sessions in either college or high school samples with fewer than 100 individuals. RCTs were relatively equal in distribution across three mean age groups (14-17.9, 18-21.9, and 22-24.9) and females were well represented, often being the majority sex in these interventions. Almost half of RCTs utilized an active control (e.g., treatment-as-usual), 42% utilized an inactive control (e.g., waitlist) and 10% used both due to the involvement of multiple intervention arms. Most RCTs utilized individual or group intervention formats, with fewer online/blended formats (12.5%). There was a wide range of interventions, with CBT-, Mindfulness-, and Acceptance/ER-based (e.g., ACT, DBT) interventions well represented. Categorical analyses indicated several differences between RCT and non-RCT study characteristics (see Table 1). For this reason, we conducted supplementary analyses with non-RCTs to ensure that our primary findings could be replicated despite these significant differences in study design and sample features.

Effects of Psychological Treatments on Symptoms and ER

Our meta-analytic findings revealed that psychological treatments produced small-to-medium effect size decreases in depression symptoms (k=117, g=0.35, p<.001, 95% CI=0.24-0.46), anxiety symptoms (k=90, g=0.29, p<.001, 95% CI=0.12-0.40), emotion dysregulation (k=13, g=0.54, p<.001, 95% CI=0.30-0.78), and disengagement ER skills (k=83, g=0.24, p<.001, 95% CI=0.15-0.32); they also produced small effect size increases in engagement ER skills (k=82, g=0.26, p<.001, 95% CI=0.15-0.32). Heterogeneity estimates were significant for the moderator (Q[5]=53.46, p<.001; I 2=90.65%) and residual model (Q[380]=1543.06, p<.001; I2=75.37%). As displayed in Table 2, main effects for depression and anxiety symptom reduction were consistent across nearly every sensitivity analysis tested, except for cognitive training interventions (see Supplementary Table 3 for heterogeneity statistics). Additionally, studies with a high overall risk of bias did not produce significant reductions in anxiety symptoms. Psychological treatments produced improvements in ER skills across almost all sensitivity analyses; however, engagement ER skills did not improve with cognitive training interventions and disengagement ER skills did not improve with Acceptance/ER-based interventions. Finally, although emotion dysregulation improvements were significant across all analyses, effect sizes could not be calculated in some areas due to a lack of studies.

Table 2. Sensitivity Analyses for the Simultaneous Effect of Psychological Treatments on Outcome Measures.

| Symptom Outcomes | ER Skills Outcomes | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Symptoms | Depressive Symptoms | Engagement ER Skills | Disengagement ER Skills | Emotion Dysregulation | |||||||||||||||||

| No. Studies | k | g | 95% CI | p | k | g | 95% CI | p | k | g | 95% CI | p | k | g | 95% CI | p | k | g | 95% CI | p | |

| Mean age | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 14-17.9 | 32 | 31 | .21 | .09, .32 | <.001 | 51 | .27 | .10, .44 | .002 | 27 | .20 | .11, .28 | <.001 | 29 | .25 | .12, .39 | <.001 | 7 | .30 | .15, .46 | <.001 |

| 18-21.9 | 34 | 36 | .39 | .22, .57 | <.001 | 40 | .37 | .23, .51 | <.001 | 32 | .32 | .19, .46 | <.001 | 35 | .27 | .18, .38 | <.001 | 2 | .33 | -.05, .71 | .09 |

| 22-24.9 | 21 | 21 | .29 | -.04, .61 | .08 | 22 | .39 | -.003, .77 | .052 | 19 | .36 | .06, .66 | .02 | 17 | .09 | -.22, .40 | .58 | 3 | .93 | .40, 1.46 | <.001 |

| Number of Sessions | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sessions > 6 | 47 | 47 | .31 | .14, .47 | <.001 | 66 | .38 | .18, .58 | <.001 | 51 | .31 | .18, .46 | <.001 | 37 | .22 | .03, .41 | .03 | 8 | .58 | .25, .92 | <.001 |

| Sessions ≤ 6 | 43 | 43 | .24 | .13, .35 | <.001 | 51 | .26 | .17, .36 | <.001 | 31 | .25 | .15, .35 | <.001 | 46 | .20 | .14, .26 | <.001 | 5 | .29 | .13, .44 | <.001 |

| Format of Delivery | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Blended / Online | 12 | 15 | .31 | .16, .45 | <.001 | 18 | .35 | .19, .50 | <.001 | 12 | .24 | .09, .40 | .002 | 10 | .26 | .08, .44 | .005 | 1 | .40 | .05, .76 | .03 |

| Individual | 32 | 33 | .40 | .18, .62 | <.001 | 44 | .32 | .17, .47 | <.001 | 14 | .31 | .09, .52 | .005 | 37 | .27 | .15, .39 | <.001 | 4 | .76 | .27, 1.25 | .002 |

| Group | 46 | 42 | .22 | .08, .36 | .003 | 55 | .34 | .15, .52 | <.001 | 56 | .25 | .14, .36 | <.001 | 36 | .20 | .07, .33 | .003 | 8 | .38 | .20, .56 | <.001 |

| Sample Type | |||||||||||||||||||||

| College | 53 | 54 | .32 | .17, .48 | <.001 | 60 | .38 | .21, .54 | <.001 | 48 | .34 | .19, .48 | <.001 | 52 | .24 | .11, .37 | <.001 | 5 | .63 | .29, .97 | <.001 |

| High School | 23 | 25 | .45 | .08, .81 | .02 | 39 | .32 | .08, .55 | .008 | 20 | .19 | .09, .30 | <.001 | 24 | .30 | .08, .52 | .007 | 4 | .32 | .10, .55 | .004 |

| Community / Outpatient | 17 | 13 | .32 | .05, .59 | .02 | 20 | .37 | .21, .53 | <.001 | 17 | .31 | .17, .45 | <.001 | 9 | .39 | .18, .60 | <.001 | 4 | .71 | .26, 1.16 | .002 |

| Type of Control Arm | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Active Control | 55 | 49 | .20 | .10, .30 | <.001 | 68 | .27 | .15, .39 | <.001 | 43 | .26 | .18, .33 | <.001 | 48 | .19 | .11, .28 | <.001 | 8 | .36 | .07, .65 | .02 |

| Inactive Control | 45 | 41 | .49 | .34, .65 | <.001 | 49 | .52 | .37, .67 | <.001 | 39 | .44 | .30, .58 | <.001 | 35 | .37 | .25, .49 | <.001 | 5 | .57 | .30, .85 | <.001 |

| Sample Size | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Large (>100) | 25 | 23 | .20 | .07, .34 | .004 | 41 | .26 | .07, .44 | .006 | 18 | .16 | .07, .26 | .001 | 34 | .18 | .10, .26 | <.001 | 0 | -- | -- | -- |

| Medium | 33 | 38 | .31 | .20, .42 | <.001 | 36 | .44 | .31, .56 | <.001 | 28 | .35 | .24, .47 | <.001 | 26 | .34 | .23, .45 | <.001 | 9 | .67c | .39, .95 | <.001 |

| Small (<50) | 34 | 29 | .43 | .14, .72 | .003 | 40 | .33 | .08, .59 | .01 | 36 | .40 | .17, .62 | <.001 | 23 | .25 | .01, .48 | .013 | 4 | .46 | .05, .88 | .05 |

| Risk of Bias Rating | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Low | 37 | 40 | .29 | .10, .48 | .003 | 49 | .30 | .11, .49 | .002 | 34 | .25 | .09, .42 | .003 | 38 | .20 | .02, .38 | .034 | 4 | .42 | .06, .77 | .02 |

| Some Concerns | 40 | 36 | .29 | .18, .41 | <.001 | 54 | .30 | .18, .41 | <.001 | 31 | .26 | .16, .36 | <.001 | 34 | .20 | .13, .27 | <.001 | 9 | .46 | .20, .72 | <.001 |

| High | 13 | 14 | .18 | -.14, .51 | .27 | 14 | .51 | .03, .99 | .04 | 17 | .43 | .22, .64 | <.001 | 11 | .28 | .07, .49 | .009 | 0 | -- | -- | -- |

| Analytic Approach | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ITT | 64 | 63 | .26 | .15, .37 | <.001 | 87 | .33 | .20, .47 | <.001 | 53 | .24 | .16, .32 | <.001 | 58 | .20 | .10, .30 | <.001 | 10 | .46 | .17, .75 | .002 |

| Completer | 26 | 27 | .39 | .15, .62 | .001 | 30 | .32 | .17, .47 | <.001 | 29 | .34 | .20, .47 | <.001 | 25 | .42 | .24, .60 | <.001 | 3 | .40 | .18, .63 | <.001 |

| Intervention Type | |||||||||||||||||||||

| CBT or PST | 36 | 32 | 37 | .11, .63 | .005 | 53 | .41 | .15, .67 | .002 | 43 | .27 | .11, .44 | .001 | 35 | .32 | .12, .52 | .002 | 4 | .89 | .36, 1.41 | <.001 |

| MSBR or MBCT | 21 | 24 | .36 | .20, .53 | <.001 | 25 | .41 | .30, .53 | <.001 | 27 | .43 | .31, .54 | <.001 | 11 | .40 | .23, .56 | <.001 | 3 | .45 | .22, .68 | <.001 |

| ABBT, ACT, DBT, UP, or other | 18 | 16 | .24 | .08, .40 | .004 | 16 | .41 | .25, .57 | <.001 | 11 | .26 | .05, .48 | .02 | 13 | .13 | -.09, .35 | .23 | 6 | .41 | .15, .66 | .002 |

| CBM, ABM, or AMT | 15 | 18 | .13 | -.01, .27 | .07 | 23 | .13 | -.02, .27 | .09 | 1 | .14 | -.21, .48 | .44 | 24 | .11 | .01, .22 | .03 | 0 | -- | -- | -- |

Note: See Supplementary Table 3 for heterogeneity statistics, the majority of which were statistically significant. Each line of statistical values was computed from one random effect multivariate meta-analytic model, given the high level of heterogeneity. Individual effect sizes were categorized by outcome and nested within the larger study. No. Studies refers to the number of unique studies that contribute to the multivariate analyses. k = number of unique statistics that contribute to the outcome result. g = Hedges’ g produced from meta-analysis; CI = confidence interval; ABBT = Acceptance-based behavior therapy; ABM = Attention bias modification; ACT = Acceptance and commitment therapy; AMT = Autobiographical memory training; CBM = Cognitive bias modification; CBT = Cognitive-behavioral therapy; DBT = Dialectical behavior therapy; ITT = Intent-to-treat; MBCT = Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; MSBR = Mindfulness-based stress reduction; PST = problem solving therapy; UP = Unified Protocol.

Are ER Skills Associated with Youth Treatment Outcomes?

Correlational analyses indicated that reduced emotion dysregulation and reduced disengagement ER skills (note, decreases in these indices were coded positively) had positive associations with improved depression and anxiety symptoms overall (see Table 3). Moreover, improved engagement ER skills had positive associations with improved anxiety and depression symptoms across all studies. Likelihood ratio tests indicated that the full model (i.e., all correlations estimated) always retained better fit statistics compared to restricted models in which one correlation was set to zero. The correlations between anxiety and engagement ER, χ2(1)=10.54, p=.012, anxiety and emotion dysregulation, χ2(1)=13.05, p=.003, and anxiety and disengagement ER, χ2(1)=20.92, p<.001, were significantly different compared to restricted models where their correlation was set to zero. A similar pattern was found for correlations between depression and engagement ER, χ2(1)=35.96, p<.001, depression and emotion dysregulation, χ2(1)=8.50, p=.004, and depression and disengagement ER, χ2(1)=20.29, p<.001. Finally, the full model retained better fit statistics compared to a restricted model where all six estimated correlations were set to zero, χ2(6)=53.96, p<.001. Below, we discuss sensitivity analyses with a focus on sample and intervention characteristics for ease (see Table 3 for results related to analytic approach, risk of bias rating, and type of intervention control).

Table 3. Overall Correlations between Depression and Anxiety Symptom Reduction and Improvement in ER Skills along with Sensitivity Analyses.

| Anxiety Symptoms | Depressive Symptoms | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement ER | Emotion Dysregulation | Disengagement ER | Engagement ER | Emotion Dysregulation | Disengagement ER | ≥ Corr. vs. Overall | |||||||

| Corr. | N | Corr. | N | Corr. | N | Corr. | N | Corr. | N | Corr. | N | % | |

| All studies overall | .54 | 39 | .88 | 10 | .72 | 37 | .92 | 47 | .94 | 10 | .82 | 45 | 100% |

| Mean age | |||||||||||||

| 14-17.9 | >.99 | 10 | .96 | 5 | .91 | 9 | .96 | 17 | >.99 | 6 | .98 | 14 | 100% |

| 18-21.9 | .21 | 16 | -- | -- | .08 | 16 | .81 | 17 | -- | -- | .55 | 20 | 0% |

| 22-24.9 | .80 | 12 | >.99 | 3 | .78 | 10 | .99 | 11 | -- | -- | .93 | 10 | 83% |

| Number of Sessions | |||||||||||||

| Sessions > 6 | .98 | 23 | .93 | 8 | .66 | 16 | .97 | 30 | .92 | 7 | .83 | 21 | 67% |

| Sessions ≤ 6 | -.99 | 16 | -- | -- | .84 | 21 | -.11 | 17 | >.99 | 3 | .59 | 24 | 33% |

| Format of Delivery | |||||||||||||

| Blended / Online | -.05 | 7 | -- | -- | -.88 | 6 | .54 | 8 | -- | -- | -.93 | 6 | 0% |

| Individual | .21 | 7 | .98 | 3 | .20 | 18 | .90 | 9 | -- | -- | .77 | 21 | 33% |

| Group | .76 | 25 | .85 | 6 | .97 | 13 | .99 | 30 | .99 | 7 | .86 | 18 | 83% |

| Sample Type | |||||||||||||

| College | .52 | 25 | .97 | 4 | .69 | 27 | .93 | 26 | .79 | 3 | .84 | 30 | 50% |

| High School | >.99 | 8 | -- | -- | >.99 | 8 | >.99 | 12 | >.99 | 3 | >.99 | 11 | 83% |

| Community / Outpatient | .84 | 8 | .37 | 4 | .76 | 3 | .92 | 11 | .83 | 4 | .57 | 5 | 50% |

| Type of Control Arm | |||||||||||||

| Active Control | .51 | 21 | .87 | 6 | .77 | 22 | .77 | 28 | >.99 | 7 | >.99 | 28 | 50% |

| Inactive Control | .42 | 23 | .92 | 5 | .18 | 21 | .91 | 25 | .38 | 4 | .55 | 25 | 17% |

| Sample Size | |||||||||||||

| Large (>100) | .61 | 9 | -- | -- | .98 | 11 | .90 | 13 | -- | -- | .97 | 16 | 50% |

| Medium | .02 | 13 | .46 | 6 | -.13 | 15 | .90 | 16 | .97 | 7 | -.22 | 16 | 17% |

| Small (<50) | .65 | 18 | .97 | 4 | .64 | 13 | .90 | 19 | .63 | 3 | .94 | 15 | 50% |

| Risk of Bias Rating | |||||||||||||

| Low | .67 | 20 | .98 | 3 | .63 | 17 | .93 | 19 | -- | -- | .95 | 17 | 83% |

| Some Concerns | .75 | 15 | .72 | 7 | .63 | 15 | .92 | 19 | .94 | 8 | .57 | 22 | 50% |

| High | .22 | 4 | -- | -- | .54 | 5 | .91 | 9 | -- | -- | .92 | 6 | 17% |

| Analytic Approach | |||||||||||||

| ITT | .90 | 26 | .88 | 8 | .67 | 26 | .97 | 32 | .87 | 8 | .83 | 34 | 67% |

| Completer | .29 | 13 | -- | -- | .81 | 11 | .66 | 15 | -- | -- | .80 | 11 | 17% |

| Intervention Type | |||||||||||||

| CBT or PST | .65 | 14 | -- | -- | .90 | 14 | .95 | 21 | >.99 | 3 | .91 | 15 | 83% |

| MSBR or MBCT | .26 | 17 | -- | -- | .88 | 4 | -.33 | 18 | -- | -- | >.99 | 6 | 33% |

| ABBT, ACT, DBT, UP, or other | -.91 | 7 | .64 | 6 | -.99 | 10 | -.12 | 7 | >.99 | 5 | -.65 | 10 | 17% |

| CBM, ABM, or AMT | -- | -- | -- | -- | -.61 | 9 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -.93 | 14 | 0% |

Note: Correlations (Corr.) = estimated correlation between two random effects, which are assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution and therefore is not simply the product-moment correlations between two variables. Each line of statistical values was computed from one random effect multivariate meta-analytic model, given the high level of heterogeneity. Positive correlations are consistent with our hypotheses, whereas negative correlations are inconsistent with our hypotheses. “≥ Corr. vs. Overall” refers to the percentage of correlations produced by a sensitivity variable that were larger (in magnitude) than the main overall finding, inclusive of missing values. ABBT = Acceptance-based behavior therapy; ABM = Attention bias modification; ACT = Acceptance and commitment therapy; AMT = Autobiographical memory training; CBM = Cognitive bias modification; CBT = Cognitive-behavioral therapy; DBT = Dialectical behavior therapy; ITT = Intent-to-treat; MBCT = Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; MSBR = Mindfulness-based stress reduction; PST = problem solving therapy; UP = Unified Protocol.

Compared to overall findings, we observed larger positive associations between improved anxiety symptoms and reduced disengagement ER skills for studies with group delivery, college and community/outpatient samples, large sample sizes, mean ages between 14-17.9 and 22-24.9, briefer treatments of six sessions or less, and CBT- and Mindfulness-based interventions. Associations in the opposite direction from expectations (i.e., improvements in anxiety and ER skills were negatively correlated) were observed for studies with blended/online delivery formats, medium sample sizes, as well as cognitive training and Acceptance/ER-based interventions. Compared to overall findings, the observed positive relationship between improved depression symptoms and reduced disengagement ER skills was larger for studies with group delivery, longer treatment lengths (greater than six sessions), mean ages between 14-17.9 and 22-24.9, college and high school samples, small and large sample sizes, and CBT- and Mindfulness-based treatments. Relationships in the opposite hypothesized direction were observed for studies with blended/online delivery formats, medium sample sizes, as well as cognitive training and Acceptance/ER-based interventions.

Compared to overall findings, the observed positive relationship between improved anxiety symptoms and improved engagement ER skills was larger for studies with longer treatments, group delivery formats, samples with mean ages between 14-17.9 and 22-24.9, small and large sample sizes, high school and community/outpatient samples, and CBT-based treatments. Shorter treatment lengths, blended/online delivery, and Acceptance/ER-based interventions produced correlations in the opposite direction of expectations (i.e., negative correlations). Improved depressive symptoms were associated with improved engagement ER skills across most sensitivity analyses, though observed correlations were larger compared to overall analyses for studies with all sample types, mean ages between 14-17.9 and 22-24.9, longer treatments, group formats, and CBT-based interventions. Negative correlations were observed for briefer treatments and those studies with Mindfulness- and Acceptance/ER-based interventions.

Compared to overall findings, the observed positive association between improved anxiety and reduced emotion dysregulation was larger for studies with longer treatments, samples with mean ages between 14-17.9 and 22-24.9, individual formats of delivery, college students, and small sample sizes. The positive association between improved depression and reduced emotion dysregulation was larger than overall findings for briefer treatments, group formats, high school samples, samples aged 14-17.9, and both CBT- and Acceptance/ER-based interventions. No relationships opposite to expectations were observed for emotion dysregulation in relationship to reduced depression or anxiety, but several correlations could not be calculated due to a lack of information.

Results for Individual ER Skills

While controlling for shared variance in symptom reduction, psychological treatments for depression and anxiety tended to increase acceptance and problem solving, but not cognitive reappraisal (see Table 4, upper portion). Additionally, psychological treatments reduced avoidance, rumination, and suppression. Findings indicate that regardless of diagnostic target or intervention approach, young people’s improvements in individual ER skills were in line with expected changes at the specific skills level, except for cognitive reappraisal. We also observed positive associations between engagement ER skills and reduced depression and anxiety extended to the specific skills of acceptance, problem-solving, and cognitive reappraisal (see Table 4, lower portion). Similarly, positive associations between reduced disengagement ER skills and reduced depression and anxiety were observed with a decrease in the specific skill of rumination. For avoidance, decreases were positively associated with reduced anxiety symptoms but negatively associated with reduced depression symptoms (the latter finding is opposite to expectations). Finally, decreased suppression was negatively associated with reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms (opposite to expectations).

Table 4. Results for Individual ER Skills Using a Multivariate Meta-Analytic Approach.

| A. Meta-Analytic Outcomes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual ER Skill | Anxiety Symptoms | Depression Symptoms | ||||||||||||

| No. Studies | k | g | 95% CI | p | k | g | 95% CI | p | k | g | 95% CI | p | ||

| Acceptance | 32 | 41 | .32 | .07, .42 | <.001 | 37 | .24 | .07, .42 | .007 | 39 | .32 | .14, .51 | <.001 | |

| Problem-Solving | 17 | 22 | .31 | .14, .47 | <.001 | 11 | .81 | .23, 1.39 | .006 | 28 | .50 | .17, .83 | .003 | |

| Cognitive Reappraisal | 16 | 19 | .23 | -.01, .47 | .06 | 15 | .27 | -.08, .63 | .13 | 19 | .44 | -.004, .88 | .052 | |

| Avoidance | 18 | 19 | .18 | .03, .32 | .02 | 13 | .21 | .04, .39 | .02 | 19 | .35 | .14, .55 | <.001 | |

| Rumination | 32 | 53 | .18 | .06, .30 | .002 | 39 | .12 | .04, .26 | .08 | 48 | .22 | .04, .39 | .02 | |

| Suppression | 9 | 11 | .26 | .03, .50 | .03 | 7 | .16 | -.39, .70 | .58 | 12 | .13 | -.04, .30 | .14 | |

| B. Heterogeneity Statistics | C. Associations between Individual ER skills and symptoms over treatment | |||||||||||||

| Moderator | Residual | Anxiety Symptoms | Depression Symptoms | |||||||||||

| Q | I2 | p | Q | I2 | p | Corr. | N | Corr. | N | |||||

| Acceptance | 14.59 | 79.4% | .002 | 462.78 | 75.4% | <.001 | .80 | 27 | .85 | 27 | ||||

| Problem-Solving | 19.85 | 84.9% | <.001 | 302.75 | 80.8% | <.001 | >.99 | 9 | >.99 | 17 | ||||

| Cognitive Reappraisal | 3.92 | 23.5% | .27 | 337.12 | 85.2% | <.001 | .67 | 10 | .90 | 12 | ||||

| Avoidance | 35.16 | 91.5% | <.001 | 146.71 | 67.3% | <.001 | .87 | 6 | -.79 | 7 | ||||

| Rumination | 9.36 | 67.9% | .03 | 635.36 | 78.4% | <.001 | .72 | 23 | .88 | 29 | ||||

| Suppression | 10.74 | 72.1% | .01 | 92.23 | 70.7% | <.001 | -.71 | 12 | -.07 | 15 | ||||

Note: Each line of statistical values was computed from one random effect multivariate meta-analytic model according to the specific ER skill, given the high level of heterogeneity. No. Studies refers to the number of unique studies that contribute to the multivariate analyses. k = number of unique statistics that contribute to the outcome result. g = Hedges’ g produced from meta-analysis; CI = confidence interval; Q = Cochrane Q, a statistic to determine heterogeneity in meta-analyses. Moderator Q = Cochran test of moderator heterogeneity. Residual Q = Cochran test for residual heterogeneity once moderator heterogeneity is removed. I 2 = heterogeneity statistic describing the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Correlations (Corr.) = estimated correlation between two random effects, which are assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution and therefore is not simply the product-moment correlations between two variables.

Consideration of Publication Bias

Egger’s test was significant for subgroupings of studies focused on outcomes for anxiety, t(65)=4.25, p<.001, and depression, t(78)=4.79, p<.001, due to a skew towards underestimating the magnitude of positive intervention findings. Using the trim-and-fill procedure under random effects assumptions, seven studies were estimated as missing to the right of the mean for the anxiety outcome studies, with an adjusted random-effects Hedges’ g=0.42, p<.001, 95% CI=0.32-0.51, favoring larger intervention effects than estimated. For depression outcome studies, 13 studies were estimated as missing to the right of the mean under random effects modeling, with an adjusted random-effects Hedges’ g=0.48, p<.001, 95% CI=0.38-0.58, again favoring larger intervention effects. Funnel plots for the anxiety and depression RCTs subgroupings with graphical imputation of the missing studies, can be found in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Given the significant differences in study characteristics between RCTs and non-RCTs, we completed supplementary analyses on the extracted intervention data utilizing the single-arm and active intervention arms if the study had multiple arms (i.e., no study controls were present in this secondary analysis). Results from 186 effect size extractions across 55 non-RCT studies largely converged with the above. After simultaneous entry of all outcome variables in a multivariate format, results indicated medium-to-large main effects in reducing symptoms of depression (k=55, g=0.61, p<.001, 95% CI=0.46-0.75), anxiety (k=44, g=0.53, p<.001, 95% CI=0.40-0.66), disengagement ER skills (k=33, g=0.56, p<.001, 95% CI=0.32-0.60), emotion dysregulation (k=10, g=0.83, p<.001, 95% CI=0.58-1.08). Small-to-medium increases in engagement ER skills were also found pre-to-post treatment (k=44, g=0.48, p<.001, 95% CI=0.37-0.59). The larger effects of treatment found for non-RCTs compared to RCTs relates to the lack of control arm data and supports our underestimation of treatment effect above. Heterogeneity remained significant for the moderators (Q[5]=111.87, p<.001; I 2=95.53%) and the residual model (Q[181]=806.08, p<.001; I2=77.55). Reduced anxiety symptoms exhibited positive associations (i.e., estimated correlations between random effects, ρ) with reduced disengagement ER skills (N=21, ρ=0.85; χ2(1)=5.48, p=.019) and improved engagement ER skills (N=29, ρ=0.60; χ2(1)=9.39, p=.002), with likelihood ratio tests indicating better fit statistics compared to restricted models where their correlations were set to zero. Reduced depression symptoms exhibited positive associations with reduced disengagement ER skills (N=25, ρ=0.90; χ2(1)=31.13, p<.001) and improved engagement ER skills (N=31, ρ=0.58; χ2(1)=22.29, p<.001), with similar likelihood ratio test findings. Reduced emotion dysregulation was associated with reduced symptoms of anxiety (N=6, ρ=0.87; χ2(1)<0.1, p>.99) and depression (N=9, ρ=0.64; χ2(1)=2.33, p=.13) in a positive direction, but likelihood ratio tests indicated that these models were statistically equivalent to restricted models where the above correlations were set to zero. Finally, the full model retained better fit statistics compared to a restricted model where all six estimated correlations were set to zero, χ2(6)=40.60, p<.001.

Discussion

Our goal was to synthesize the associative changes between ER skills and emotion dysregulation during psychological interventions targeting depression and anxiety in youth and young adults. The current study extends other reviews37,38 by focusing on dimensional depressive and anxiety symptoms in young persons aged 14-24, incorporating ER skills to broaden previous reviews, and involving a panel of youths with lived experience to support study design and knowledge dissemination. Our youth advisory informed the interpretation of the results and commentary outlined below.

Psychological treatments reduced anxiety, depression, disengagement ER skills, and emotion dysregulation, and improved engagement ER skills. Results for depression and anxiety were robust across almost all sensitivity analyses conducted and consistent at the individual skill level, with the two engagement ER skills increasing, and three disengagement skills decreasing, over the course of treatments for anxiety and/or depression symptoms. Moreover, significant reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms during treatment were positively associated with significant reductions in emotion dysregulation and disengagement ER skills, as well as significant increases in engagement ER skills. Our findings are consistent with discussions regarding the importance of ER in treatment,50,51 the general effectiveness of various psychological treatments for depression and anxiety symptoms52,53 and the discussion of common factors that may underlie them.54,55 Improvements in intrapersonal ER skills may represent a common “active” ingredient across psychological interventions for young people, consistent with a substantial treatment literature in adult samples demonstrating a similar effect.42–48 Findings suggest that a common goal across psychological interventions for depression and anxiety symptoms in youth and young adults may be to increase and diversify the types of intrapersonal ER skills used to regulate emotions. However, future work will want to examine this question empirically using mediation analyses and determine if this relationship remains true during follow-up.

With respect to anxiety symptoms, positive treatment outcomes produced relatively larger positive associations with reduced disengagement (vs. improved engagement) ER skills during treatment. One possible explanation for this finding is the central role in reducing the experiential avoidance and anxious arousal common in anxiety through exposures and cognitive restructuring across several intervention approaches.56,57 Young people with anxiety are often explicitly taught to accept rather than suppress their feared thoughts or situations in treatments, which may facilitate a reduction in disengagement ER skills (i.e., avoidance, ruminative negative thinking, and suppression) that may have maintained their anxiety.56,57 Nevertheless, increases in engagement ER and reductions to emotion dysregulation were also associated with reduced anxiety symptoms during treatment. Our youth advisory board highlighted the utility of framing depression and anxiety as problems with ER to reduce the stigma regarding the disorders; moreover, they felt that it would be valuable to increase awareness of the relationships between ER skills and depression/anxiety symptoms to the broader youth audience.

Positive outcomes for depression produced large positive associations with increased engagement ER skills. Nevertheless, positive treatment outcomes were also positively associated with reduced disengagement ER skills and general emotion dysregulation. Given pre-treatment relationships between intrapersonal skills and symptoms of depression and anxiety,18,21–25 young people with depression appear to endorse rumination (or repetitive thinking) more strongly along with avoidance and suppression of their negative emotions. Coupled with lower use of problem-solving and other engagement ER skills,34–36 rumination can increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors,58 and so youth with depression may simply have more skills to gain from treatment to avoid negative mental health outcomes. Regardless of how one defines ER skills, it appears that helping to correct a bias in using disengagement over engagement ER skills is common to interventions for depression in youth and young adults. As a result, overall reductions in emotion dysregulation were also associated with large effect-size reductions in depression symptoms during treatment in a similar manner. Collectively, our multidimensional investigation permitted a nuanced investigation of these three different ER skills constructs with treatment outcomes and elucidates the multiple possible pathways to recovery for youth with anxiety. As a result, interventions that focus on improving engagement ER skills, and decreasing disengagement ER skills and emotion dysregulation, may all be particularly impactful for anxiety and depression symptom reduction.

There were some unexpected findings: youth aged 18-21.9 exhibited positive, but smaller in magnitude, correlations between symptom reduction and improved ER skills versus two other age groups. There is considerable moderator (i.e., outcome) heterogeneity for studies in this age group, which may have suppressed enhanced positive relationships (see Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, shorter treatments, blended/online formats, and cognitive training and Acceptance/ER-based interventions exhibited some negative correlations (opposite direction than expected) for both anxiety and depression compared to previous research.44–48 It is possible that longer treatments are necessary for youth anxiety and depression to build engagement ER skills (perhaps related to exposure protocols) whereas positive associations in disengagement ER and emotion dysregulation were found regardless of treatment length. Our findings related to blended/online and Acceptance/ER-based interventions should be interpreted with caution due to the lower number of studies contributing to these analyses. In addition, studies incorporating Acceptance/ER-based interventions appeared to be smaller in sample size and had more risk of bias concerns on average, which may have led to these unexpected findings. Finally, cognitive training interventions are usually delivered as brief treatments (i.e., single-session) and observed changes to ER skills pre-to-post treatment may not be immediately observable.

Reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms during treatment were not universally associated with reduced disengagement ER skills on an individual basis. In fact, reduced suppression was in the direction opposite to expectations for changes in anxiety and depression, while avoidance was in the direction opposite to expectations for changes in the latter only. Improvements in all three engagement ER skills considered here were positively associated with anxiety and/or depression symptom reduction, though problem-solving had the largest observed association. Alternatively, reductions in suppression and avoidance were not consistently associated with reductions in depression and or anxiety symptoms. Previous reviews37,38 found decreases in all disengagement ER skills (rumination, avoidance, and suppression) following psychological treatment, a potential reflection of the shared repetitive negative thinking construct that underlies psychopathology.59 However, the present study quantitatively assessed specific ER skills and focused on depression and anxiety symptoms in youth and young adults, which could potentially explain the difference in findings. While replication and more stringent mediation methods are necessary to understand these relationships, results suggest that it may not be necessary to completely reduce disengagement ER skills for positive anxiety and depression treatment outcomes. We also note that the labels “disengagement” and “engagement” are used to imply habitual use of these skills over relatively long periods of time, which over the long-term are respectively associated with higher and lower levels of psychopathology,24,25,34 and research about their relationship with emotional experiences.39,60 Nevertheless, our two-factor grouping of ER skills fails to consider the context in which those skills are used, a factor found to be increasingly important to determine effectiveness and mental health outcomes,40,41 though less research has been conducted on post-treatment individuals.

Substantial differences between RCTs and non-RCTs that met criteria for inclusion suggested that our RCTs may be different than the broader sample of treatment studies at large. Although we largely confirmed our meta-analytic findings in non-RCTs, the associations were more limited in some cases (i.e., emotion dysregulation) by the smaller number of studies included overall. Our risk of bias assessment for RCTs found less than 20% were at high risk for bias, even after we employed a conservative approach which automatically elevated some studies to high risk. No study had two or more domains where high risk was identified. Results from funnel plot examination and the trim-and-fill procedure indicated that findings with respect to interventions were underestimated due to our selection of a large range of studies that were variable in their reduction of depression and anxiety symptoms. This is also indicated by the small-to-medium effect size reduction in symptoms for RCTs compared to the large effect sizes seen in the relatively more uncontrolled nature of non-RCTs. Thus, we argue that our findings remain unchanged even after considering potential study selection and publication bias.

Our sensitivity analyses were attempts to understand which features of interventions were linked to larger associations between symptom reduction and improvement in ER skills, as well as who might benefit the most. Overall, studies that produced larger positive associations tended to have interventions that were longer (>6 sessions), delivered in group format, and were CBT-based. There were relatively consistent effects regardless of sample type and age, suggesting that most youth with depression and anxiety symptoms can benefit from interventions that yield ER skill improvements and especially those under 18. There were some differences depending on whether depression versus anxiety symptoms were targeted. In addition to the above findings, shorter interventions and individual formats were also effective approaches at times for depression symptoms and produced positive associations with improvements in ER skills. Overall, there were mixed findings with respect to which interventions enhanced treatment outcomes for depression versus anxiety, and this was likely related to a difficulty in dividing the studies into distinct categories based on therapeutic orientation. Nevertheless, CBT-based interventions more consistently improved engagement (and reduced disengagement) ER skills, while Acceptance/ER-based interventions were successful in reducing emotion dysregulation. Mindfulness-based interventions were also particularly effective in reducing disengagement ER skills. As treatments become more transdiagnostic, these findings could help clinicians design and evaluate new formats of intervention delivery for the population they serve.

Broader clinical implications may include facilitating the design and implementation of briefer, more efficacious treatments for depression and anxiety that specifically target improvements to ER skills. Discussions with youth indicated a need for greater awareness around the relationship between ER skills and mental health, and a greater understanding of how improvements in ER skills contribute to more positive treatment outcomes. Our youth advisory also commented on a need to increase the agency and autonomy of young people by developing self-assessment tools to understand which skills they already have, and which could use improvement. In addition, helping youth to understand the types of ER skills they might gain from certain interventions may help them make better, informed decisions about treatment. At a higher level, the advisory recommended reforms to school curriculums to incorporate ER skills training at all levels of education as a preventative strategy to mitigate mental health concerns in young people. This approach would have the benefit of removing barriers typically associated with treatment in young adults (e.g., cost of services, finding a therapist, stigma) and could incorporate peer-led delivery of skills coaching.

Results also serve to support affective science perspectives on mental disorders and theoretical models of emotion dysregulation.7,28–30 Reductions in symptoms during treatment were generally associated with improvements in ER skills, translating into the reduction of emotion dysregulation. Moreover, the results of our synthesis support continued distinction between the two groupings of skills utilized in this study, as findings for engagement and disengagement ER skills were generally in the expected direction, supporting their earlier putative associations with psychopathology and models of their common structure.34,39 However, subtle differences between the two skills groupings also remained and played an important role in identifying key factors involved in the treatment of depression versus anxiety. Overall, we demonstrated more specificity of the ER constructs compared to past reviews37,38 by conducting separate analyses for more generalized measures of emotion dysregulation and specific ER skills.

Additional limitations of the present meta-analysis, include limiting the selection of studies to only those written in English and relying almost entirely on data from self-report measures, which can be susceptible to recall bias.61 Future treatment trials should also consider more ecologically valid tools such as experience sampling assessments to evaluate treatment success.62 Further, adults with higher levels of emotion dysregulation have more difficulty reporting on their emotional experiences,63,64 which suggests that youth may introduce substantial variability in subjective responses as well. There were slight biases in how studies contributed to the meta-analysis; for example, RCTs with Mindfulness-based interventions more often assessed engagement ER skills (e.g., acceptance) whereas trials of Acceptance/ER-based and cognitive training interventions more often assessed disengagement ER skills (e.g., rumination). There was some indication of publication bias and significant heterogeneity between individual RCTs treating depression and anxiety symptoms; however, we attempted to mitigate concerns by conducting sensitivity analyses, and considering other non-RCTs which met the criteria for inclusion, which tended to align with the overall findings. It is worth restating that we were unable to examine more causal relationships, such as whether improvements in ER skills in the middle of treatment acted as a mediator for positive treatment outcomes at the end of treatment or at follow-up, something we hope future research can address.

Similarly, a separate but ongoing debate centers on whether depressive or anxious symptoms cause difficulties in ER or vice versa. One possibility not examined here is that these constructs exhibit reciprocal relationships that change dynamically over time with other additional variables, such as the person’s environment and conditioning playing a role in how one learns to regulate their emotions.29,30,65 This may be particularly relevant for adolescents and young adults who rely on family members, caregivers, and interpersonal relationships for emotional support. More broadly, there is important discussion regarding the overlapping nature of depression and anxiety with certain ER skills (e.g., rumination and depression;35,66 avoidance and anxiety67); this conceptual issue has been noted previously34–39 and may contribute to artificially inflated effects in the current synthesis. Moreover, there are critical discussions revolving around what constitutes an ER skill and whether definitions have become too broad.39 These issues can make it difficult to understand whether changes in depression and anxiety are caused by changes in ER skills or the opposite, or whether they simply represent overlapping constructs. Despite an attempt, this synthesis was not able to examine or incorporate analyses related to whether interpersonal ER skills improve in relation to depression and anxiety symptom reduction over treatment in youth. We do not diminish the potential importance that psychological treatments have on improving interpersonal ER in comparison to intrapersonal ER skills. Given the recent development of appropriate interpersonal ER skills measures,19,27,68 we are hopeful that future research will address this, and the other issues noted above, in an appropriate and quantitative manner.

Drawing inferences from the large body of evidence incorporated into the current study, we found that improvements in intrapersonal ER skills defined in three different ways (e.g., emotion dysregulation; disengagement ER; engagement ER) were associated with significant treatment gains for depression and anxiety in youth and young adults. Interventions with six or more sessions, cognitive-behavioral interventions, and a group format of delivery produced larger associations between improvements in ER and symptom reduction. These findings are consistent with the improvement of ER skills as a transdiagnostic active ingredient in the treatment of depression and anxiety in young people. Dissemination of these findings to youth and healthcare providers will aid in increased awareness and more informed decisions regarding treatment.

Method

Protocol

We used established PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines and the AMSTAR recommendations to conduct this review.69 We also followed procedures outlined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews.70

Inclusion (and Exclusion) Criteria

Studies were identified according to the following criteria for inclusion (in bold), with notes relevant for exclusion described:

-

a)

Written in English.

-

b)

Primary cohort data in peer-reviewed source. Secondary sources, case studies, dissertations, and published abstracts were excluded.

-

c)

Young people with a mean age between 14.0 and 24.9 received an intervention. This age range was chosen based on epidemiological studies regarding the age-of-onset for depression and anxiety.1,2 Studies that only reported age range were retained if the median value fell within the above age range, unless the authors utilized a sample of considerable interest (e.g., college or high school students; n = 3 in the current synthesis).

-

d)

Contains a psychological intervention. We defined a psychological intervention as any evidence-based intervention that was grounded in psychological principles to reduce symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. This definition was designed to include protocols derived from established and more novel psychological treatments across a range of modalities (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive bias modification). We excluded interventions that were psychoeducational only (e.g., provided pamphlet, online resource), pharmacological, or neurostimulation-based. We utilized lists of treatments endorsed by Division 12 (Society of Clinical Psychology) of the American Psychological Association as a guide to evidence-based psychological interventions.71

-

e)

Outcome measure assessing depression and/or anxiety symptoms. Studies could vary in diagnostic focus (e.g., although the majority targeted depression or anxiety, some studies did recruit young persons with eating or substance use disorders) but were required to include a dimensional outcome measure of depression, social anxiety, and/or generalized anxiety (e.g., Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale; Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale; Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders). No cutoff on these measures was applied. We excluded studies with more general measures of psychopathology (e.g., internalizing symptoms) and well-being (e.g., quality of life) as they do not assess depression or anxiety precisely and impact the capacity to pool and interpret results. We did not explicitly exclude studies with a focus on panic disorder, agoraphobia, or specific phobia. We excluded studies with primary diagnoses of obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder because the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders now places them in a separate classification section from the depressive and anxiety disorders described above.72

-

f)

Outcome measure assessing emotion regulation skills or lack thereof. We included studies that incorporated a general measure of emotion dysregulation (e.g., ER skills deficits) and/or a specific measure of ER skills, based on previous expert reviews (e.g., rumination, suppression, avoidance, cognitive reappraisal, acceptance, or problem solving).34–39 We excluded studies with more general measures of coping, unless the study utilized a subscale that overlapped substantially with one of the above specific ER skills. We considered several assessment measures related to expert reviews of interpersonal ER19,20,27,68; however, we were unable to locate any intervention trials that utilized these measures. For more details on our operational definitions as well as examples of scales and items utilized see the Supplementary Information. There, we also include findings pertaining to interpersonal ER summarized in a qualitative format.

Involvement of Youth with Lived Experience

A youth advisory was recruited from members of the National Youth Action Council at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health were involved in all stages of the current research. The council was developed to engage young persons in clinical, educational, and research programming. Two youth facilitators and three members of the council with lived experience about psychological treatments for depressive and/or anxiety symptoms advised the design and implementation of the current review, and associated knowledge dissemination activities. Advisory meetings provided input on the study questions and design, results interpretation, and recommendations for knowledge dissemination materials and knowledge mobilization from a youth perspective.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

Articles were identified through searches using database-specific subject headings and keywords in natural language in the following databases: Medline (including Epub ahead of print, in-process, and other non-indexed citations), Embase, APA PsycInfo, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and The Cochrane Library. A medical librarian (TR) developed the search strategies with input from the team and conducted all searches on June 26, 2020. We used terms to capture psychopathology (e.g., “depression”, or “anxiety”) and youth and young adult populations (e.g., young adult” or “transitional age”). These concepts were then combined with two separate strands. The first strand listed specific therapeutic modalities (e.g., “cognitive behavioral therapy”), while the second strand combined terms related to mental health services (e.g., “psychotherapy”) with emotion regulation terms (e.g., “mood regulation”). This approach allowed us to capture studies that may not include ER skills as a primary outcome. Conference abstracts, dissertations, case reports, commentaries, editorials, and letters to the editor were excluded when possible. Year limits applied were 1994-present, coinciding with the development and publication of diagnostic and ER conceptual definitions.73 No language limits were applied. The full Medline and PsycInfo search strategies can be found in our Supplementary Information. Results of the literature search were imported into online software (Covidence), where duplicates were removed.

At the first stage, all titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion by two independent team members and conflicts were resolved by team consensus (81% average agreement; κ = .51). Although this indicated “moderate” inter-rater agreement for this stage (rather than substantial, κ = .61-.80, or almost perfect agreement, κ = .81-1.00), this was most likely due to the use of “maybe” ratings (i.e., three response alternatives) within Covidence at this stage, which were later resolved through consensus meetings. The second screening stage used two response alternatives. Here, each full-text article was similarly reviewed by two team members with conflicts resolved by team consensus (96% average agreement; κ = .82). At each stage, the team carefully excluded studies that focused on severe medical issues (e.g., cancer, HIV, heart/liver diseases), brain or body trauma (e.g., traumatic brain/spinal cord injuries, stroke), neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., fetal alcohol spectrum and autism spectrum disorders), intellectual disabilities or impairments, and psychiatric conditions that would supersede a diagnosis of a depressive or anxiety disorder in terms of severity (e.g., psychotic spectrum disorders). Reference lists of chosen articles were also hand-searched to identify any relevant resources not captured by the systematic searches.

Data Extraction

We extracted data from all studies selected for inclusion; however, primary analyses were conducted on data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) due to their rigorous study design. We then compared the study characteristics of RCTs to non-RCTs (i.e., single intervention arm or non-random allocation to treatment arms) to examine differences as well as potential publication bias. The study characteristics of included RCTs and non-RCTs and are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 (respectively), including the mean age/range, sex, sample type (e.g., college, outpatient, high school), sample size, intervention setting (e.g., hospital, university), intervention arm comparisons, mode of delivery (e.g., group, individual, blended), intervention length and session frequency, and outcome measures.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Quality and risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias (ROB) tool (version 2.0).74 This tool allows sources of bias to be assessed in five domains: generation of randomized allocation sequence; concealment of randomization; reporting of incomplete outcome data; selective reporting of data; and protection against contamination. We followed the provided algorithm to assess individual domains, with two minor modifications to improve the consistency of the overall bias rating. First, any study with least one “High” risk rating or ≥4 “Some Concerns” ratings automatically received a “High” overall rating to improve the conservative nature of ROB ratings and distribute them more evenly for later sensitivity analyses. Second, low risk studies had either all “Low” risk ratings across the five domains or only one “Some Concerns” rating. Quality ratings were completed by SAH and SA and all ratings were discussed through consultation meetings with ARD for final consensus. A full breakdown for each domain and their overall score provided in Supplementary Table 4. Because the design of non-RCTs would automatically introduce multiple concerns with respect to randomization and participant allocation, we did not complete ROB ratings for these studies.

Calculation of Effect Sizes

Quantitative data from RCTs was imported directly into Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 3.3.070 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) and converted to a standardized score (Hedges’ g). Hedges’ g was used because it can correct for small sample sizes and because the magnitudes for effect sizes are similar to Cohen’s d (≥ 0.20 for small; ≥ 0.50 for medium; ≥ 0.80 for large).75 Effect sizes were calculated only from reliable and validated self-report and observer-rated questionnaires (i.e., no single item assessments). We extracted data from as many studies as possible using the means, standard deviations, change scores, effect sizes, and/or t- or F-tests reported in each article. Positive effects were coded when change in that variable were in the expected direction over treatment (as hypothesized above). We prioritized intent-to-treat sample size and treatment data (71%); otherwise, completer data was used (29%). When more than one measure was used for a single outcome (e.g., for depression, anxiety, ER skills), or more than two interventions were compared (e.g., three-arm studies), we computed all effect sizes and standard errors and grouped them under each study using additional variables for treatment arm and specific measure. Later, in the meta-analysis we used outcome as the inner factor and study as the outer factor to account for nesting of effect sizes within each study.

Meta-Analysis

Given the stochastically dependent nature of our five outcome variables,76,77 we ran a multivariate meta-analysis using the “metafor” package in R (version 4.0.2).78 This method allowed us to conduct one large meta-analysis followed by sensitivity analyses, simplifying the output. Random-effects models were used, which assume that included studies are from populations of studies that differ from each other systematically. The effect sizes calculated in CMA were exported and loaded into R. As we lacked prior knowledge of the covariance structure between the dependent effect sizes, we followed established methods76 and estimated our meta-analytic outcomes while “using robust computations of the variances that consider the dependence of the effect-size estimates within studies”. Thus, a working covariance matrix was created across each of the outcome variables within each study based on an estimate of the population-level correlations. We chose a conservative ρ (Rho) value of 0.70 to estimate this population-level correlation, given that depression and anxiety symptoms are strongly correlated but not completely overlapping (i.e., between .60 and .80).79 While previous meta-analyses found medium effect size correlations between anxiety/depression symptoms and disengagement ER strategies (e.g., ≤0.56), with smaller effect size correlations for engagement ER strategies,34 0.70 was used to more conservatively control for shared variance among all outcome variables. In preliminary analyses, we tested several assumptions for our hypothesized ρ value (0, which would imply no population-level correlation; 0.50, 0.70, and 0.90). As the assumed correlation between our dependent variables increased, the estimates for each outcome decreased (in line with theoretical assumptions). However, results were relatively insensitive to small differences when ρ > 0, with all estimates remaining significant; therefore, we continued using 0.70.

To examine the associations between changes in depression or anxiety symptoms and change in ER skills within three overarching categories associated with their operational definition (e.g., disengagement ER, engagement ER, emotion dysregulation), we utilized the correlation matrix that was produced by the “metafor” package. These computed correlations represent the estimated restricted maximum likelihood relationship between two random effects, which are assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution. This differs from product-moment correlations between two observed variables and therefore cannot be tested using standard methods for traditional correlation coefficients (i.e., Pearson, Spearman). To test the sensitivity of the overall correlations, we compared them against restricted models where each of the six correlations were set to zero (using the rho argument), reducing each by one parameter. The ANOVA function in R was used to produce a likelihood ratio test, which follows (asymptotically) a chi-square distribution where degrees of freedom is equal to the difference in the number of parameters in the full and the reduced model. In addition, we report the correlation estimates from our sensitivity analyses to examine the relative magnitude of association between changes in each ER skills construct with changes in depression and anxiety while also controlling for shared associations. A caveat is that we do not present tests to support significant differences between the correlations themselves. All meta-analysis statistics, in addition to other statistics computed in this manuscript utilize two-sided probability.

Assessing Homogeneity and Sensitivity Analyses

The “metafor” package provided Cochran’s Q values to test the significance of heterogeneity in both the moderators and the residual model (after accounting for heterogeneity of the moderators). In addition to the Q statistic, I 2 is an intuitive and simple expression of the inconsistency of studies’ results and indicates the percentage (0% indicating none; 25% low; 50% moderate; and 75% substantial heterogeneity) of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance.80 The I 2 value does not depend on the number of studies for its calculation and was estimated using the formula: I 2 = 100% × [(Q - degrees of freedom)/Q]. As an additional method to probe heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were planned to probe the overall effects of RCTs. We conducted analyses based on sample type (e.g., college, outpatient, high school), sample size, mode of delivery (e.g., group, individual, blended), intervention length, analytic approach, and overall risk of bias rating.

Publication Bias

In addition to study selection bias, publication bias for the treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms was assessed by funnel plot inspection, Egger’s test for asymmetry, and Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill procedure;81 the latter yields an estimate of the effect size after publication bias has been considered with an imputation of missing studies. These analyses were completed in CMA. In addition to this standard procedure, we ran exploratory analyses using data extracted from non-RCTs as a comparative analysis upon examining the differences in RCT versus non-RCT study characteristics. Effect sizes were first calculated in CMA as above, and then exported and run in R using the same multivariate approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by funding from the Wellcome Trust. This project was developed in partnership with the Youth Engagement Initiative, supported by the Margaret and Wallace McCain Centre for Child, Youth & Family Mental Health and the Child, Youth and Emerging Adult Program at CAMH. Funding by the Wellcome Trust was awarded to ARD, SAH, and LCQ after a competitive request for proposals examining “active ingredients” in psychological treatments for youth depression and anxiety aged 14-24. More information about the initiative and the other teams funded can be found here (https://wellcome.org/what-we-do/our-work/mental-health-transforming-research-and-treatments).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: ARD, SAH, and LCQ conceived, designed, and obtained funding for the study; TR designed and executed the search strategy in consultation with ARD, SAH, and LCQ; TR managed the database of search results; ARD and SA performed data analysis; ARD, SAH, and LCQ organized and met with youth advisory board. All authors (ARD, SAH, SA, SK, TR, and LCQ) contributed to study selection and screening procedures, as well as writing of the manuscript and additional supplementary materials.

Competing Interests: None of the authors have financial conflicts of interest to disclose or have a relationship that may pose a conflict of interest in relation to the content presented in the manuscript. The authors independently chose the active ingredient based on their expertise and the funding source did not play a role in the design of this review, data collection and analyses, or the decision to publish this manuscript. None of the authors have previously received funding from the funding source.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available through an OSF repository (https://osf.io/56fvu). Additional details are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code Availability Statement