Abstract

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a stem cell-derived neoplasm characterized by dysplasia, uncontrolled expansion of monocytes and a substantial risk to transform to secondary acute myeloid leukemia (sAML). So far, little is known about CMML-initiating cells. We found that leukemic stem cells (LSC) in CMML reside in a CD34+/CD38– fraction of the malignant clone. Whereas CD34+/CD38– cells engrafted NSGS mice with overt CMML, no CMML was produced by CD34+/CD38+ progenitors or the bulk of CD34– monocytes. CMML LSC invariably expressed CD33, CD117, CD123 and CD133. In a subset of patients, CMML LSC also displayed CD52, IL-1RAP and/or CLL-1. CMML LSC did not express CD25 or CD26. However, in sAML following CMML, the LSC also expressed CD25 and high levels of CD114, CD123 and IL-1RAP. No correlations between LSC phenotypes, CMML-variant, mutation-profiles, or clinical course were identified. Pre-incubation of CMML LSC with gemtuzumab-ozogamicin or venetoclax resulted in decreased growth and impaired engraftment in NSGS mice. Together, CMML LSC are CD34+/CD38– cells that express a distinct profile of surface markers and target-antigens. During progression to sAML, LSC acquire or upregulate certain cytokine receptors, including CD25, CD114 and CD123. Characterization of CMML LSC should facilitate their enrichment and the development of LSC-eradicating therapies.

Keywords: Leukemic Stem Cells, AML, NSGS Mice, CD33, Venetoclax

Introduction

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a myeloid neoplasm defined by dysplastic bone marrow (BM) cells, persistent peripheral blood (PB) monocytosis (≥1000/μL and ≥10%) and a considerable risk of transformation to secondary acute myeloid leukemia (sAML).1–5 In most cases, splenomegaly is detected at diagnosis. According to leukocyte- and blast cell counts, CMML can be divided into dysplastic and proliferative variants.4,6,7 In addition, the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO) separates CMML patients into CMML-0 (<2% blasts in PB or <5% in BM), CMML-1 (2-4% blasts in PB or 6-9% blasts in BM) and CMML-2 (5-19% blasts in PB or 10-19% blasts in the BM).6,7

CMML cells exhibit variable combinations of somatic mutations in a number of genes, including TET-2, SRSF2, ASXL-1, RUNX1 and RAS in the absence of BCR-ABL1.5,8–10 In addition, the JAK2 mutation V617F or KIT mutation D816V may be detected.11–16 The presence of multiple mutations in CMML is associated with advanced disease and poor outcomes.17–19 Overall, the prognosis of advanced CMML and sAML is poor and treatment options are limited.17–20 The only (potentially) curative treatment approach for these patients is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), but most patients are ineligible due to age or comorbidities.21,22

There is compelling evidence that leukemias are organized in a hierarchical fashion with leukemic stem cells (LSC) at the top, providing the basis for approaches to improve treatment strategies by eliminating disease-propagating cells.23–31 The leukemia-initiating ability of LSC can be demonstrated in highly immuno-deficient mice, such as non-obese diabetic severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice lacking an IL-2 receptor-gamma chain (NSG mice). In most forms of AML, NSG-engrafting LSC reside in the CD34+ cell compartment.24,25,32 Depending on the AML variant and mouse strain employed, AML LSC are detected in CD34+/CD38– and sometimes also in CD34+/CD38+ sub-fractions.32 In the blast phase of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), CD34+ LSC also exhibit CD3833, while in chronic phase CML, LSC are primarily found in a CD34+/CD38– cell fraction.26,27,34,35 Normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) also reside in a CD34+/CD38– compartment. However, in contrast to BM HSC, CML LSC express CD25, CD26, and IL-1RAP.34–36 Cell surface antigens abnormally (aberrantly) expressed on CD34+/CD38– AML LSC include CD25, CD47, CD96 and CLL-1.37–39

In patients with CMML, the malignant clone consists almost entirely of myelomonocytic cells of variable maturation.1–4 In those with advanced CMML, increased numbers of CD34+ (blast) cells may be detected. However, so far, only little is known about the phenotype of NSG-engrafting CMML LSC. This is in part due to the lack of suitable engraftment models in CMML. When injecting CMML cells into NOD/SCID mice or NSG mice, no or only low engraftment is found. However, recent data suggest that substantial engraftment of CMML cells can be achieved in NSGSGM3 (NSGS) mice.40,41 These mice express three human cytokines: stem cell factor (SCF), interleukin-3 (IL-3) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).40,41 However, little is known about the phenotype and target expression profiles of NSGS-engrafting CMML LSC.

The aims of the current study were to identify and characterize the phenotype of CMML-initiating and propagating LSC and to compare LSC phenotypes in untransformed CMML with those found in patients with sAML following CMML.

Patients and Methods

Reagents

RPMI 1640 medium and penicillin/streptomycin were purchased from Lonza (Verviers, Belgium), amphotericin B from PAN-Biotech (Aidenbach, Germany), fetal calf serum (FCS) from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) and venetoclax, ponatinib, and selinexor from Selleckchem (Houston, TX). Gemtuzumab-ozogamicin (GO) was obtained from Pfizer (New York, NY). Stock solutions of drugs were prepared by dissolving in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). 3H-thymidine was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA). A specification of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) used in this study is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Patients

Twenty-six patients with initial diagnosis of CMML (9 female, 17 male; median age: 72 years, range: 45-82 years) were included. Detailed information on the patients’ diagnosis are provided in the supplement. Patient characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table S2. All patients gave written and informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the participating centers and conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Details are provided in the supplement.

Cell lines

The human monoblastic cell lines U937, MonoMac-6 and THP-1 were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ; Leipzig, Germany). All cell lines were grown in RPMI medium plus 10% FCS and antibiotics at 37°C. Cells were periodically tested for mycoplasma contamination by conventional PCR using the Venor GeM Classic Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Minerva Biolabs, Berlin, Germany). In addition, the identity of the cell lines was checked in regular time intervals by genotyping, qPCR and surface phenotyping.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Heparinized BM or PB aspirate samples (25-100 μL) were incubated with combinations of mAb for 15 minutes. After erythrocyte-lysis, performed with BD lysing-solution (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA), expression of surface antigens on CD34+ CMML cell-subsets (LSC and progenitor-enriched fractions) was examined by multicolor flow cytometry on a FACSCantoII (BD Biosciences). The gating strategy employed to identify LSC is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Antibody-reactivity was controlled by isotype-matched control-antibodies. Cell sorting was performed with purified and CD3-depleted mononuclear cells (MNC) on a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). After sorting, the purity of the sorted cell-fractions was >95% in each case, and cell viability amounted to >80% in all samples.

Culture of neoplastic cells and in vitro experiments

In drug incubation experiments, primary BM-derived MNC as well as the monoblastic cell lines (U937, MonoMac-6, THP-1) were employed. In typical experiments, cells were incubated in control medium or increasing drug concentrations and proliferation was measured after 48 h using 3H-thymidine uptake. In an initial screen, GO and venetoclax were selected as most potent drugs. Details are provided in the supplement. Drug effects on cell viability were examined by flow cytometry. In these experiments, cells were treated with increasing drug concentrations for 48 h. Viability and apoptosis of drug-exposed cells were determined by staining with Annexin-V and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Primary MNC were additionally stained with mAb to allow gating for LSC-enriched fractions (CD45+/CD34+/CD38– cells) as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Xenotransplantation experiments

In a subset of patients (CMML-1, n=4; CMML-2, n=4; sAML, n=3), sub-populations of primary MNC were purified by magnetic T cell-depletion and subsequent cell sorting on a FACSAria sorter (BD Biosciences). CD3-depleted total MNC served as control. Sorted cells were injected intravenously (i.v.) into the tail vein of NSGS mice. In a separate set of experiments, cells were treated in vitro with GO (100 ng/ml) or venetoclax (100 nM) for 1 h prior to injection. Drugs were removed by centrifugation before injection into NSGS mice. After injection, mice were inspected daily and sacrificed when they showed disease symptoms or after 25 weeks (6 months). BM cells were obtained from flushed femurs, tibias, and humeri of these mice and engraftment was analyzed by flow cytometry and Giemsa-staining of cytospin preparations. Animal studies were approved by the ethics committees of the Medical University of Vienna and the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, and carried out in accordance with guidelines for animal care and protection and protocols approved by Austrian law (GZ-68.205/0050-WF/V/3b/2015).

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations and tests are described in the supplement. Differences were considered significant when p<0.05.

Results

CD34+ cells obtained from the BM or PB of CMML patients engraft NSGS mice

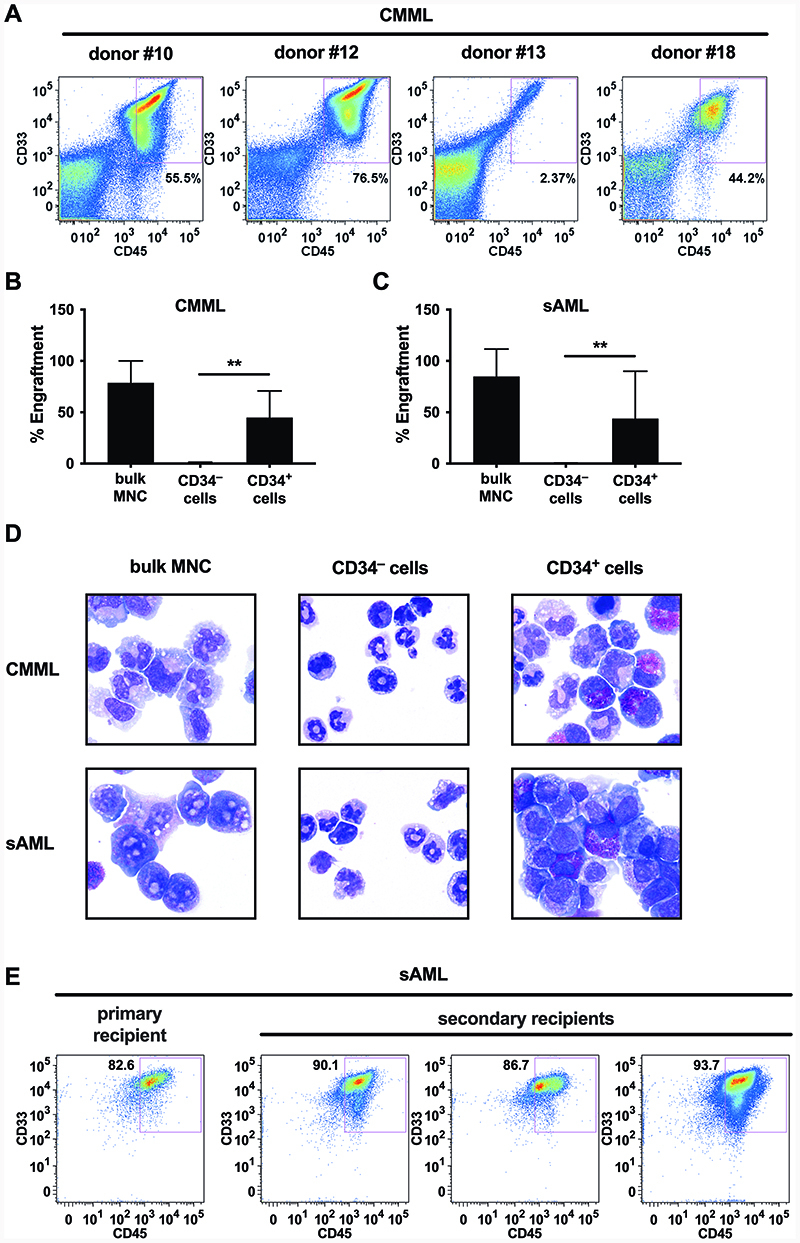

To identify CMML LSC, we purified CD45+/CD34+ cells in 4 donors with CMML (PB, n=3; BM, n=1) and injected these cells into NSGS mice to define their CMML-initiating and propagating capacity. In all 4 donors, the CD34+ cells produced leukemic engraftment after 2-6 months (≥1% human CD45+ cells in mouse BM; Figure 1A+1B, Table 1). The same result was obtained in sAML (Figure 1C, Table 1). As expected, bulk MNC (CD3-depleted cells in CMML and sAML) also produced myeloid engraftment (CD34+/CD33+ cells) in all donors tested (Table 1). By contrast, CD45+/CD34– CMML and sAML cells did not engraft in NSGS mice (Figure 1B+1C, Table 1). Engrafting cell populations consisted of immature and mature monocytes as well as eosinophils, basophils and blast cells in the CMML samples, and predominantly of blast cells in the sAML samples (Figure 1D). Monocytic engraftment was confirmed by demonstrating the presence of human CD14+ cells in mouse BM samples by flow cytometry (not shown). We next calculated the frequency of NSGS-repopulating LSC in the CD34+ cell fractions by limiting dilution experiments. The calculated frequency of NSGS-engrafting CMML LSC ranged between 0.00893% and 0.0423% of all CD34+ cells (Supplementary Table S3). Engrafted sAML cells were also able to produce leukemic engraftment in secondary transplant recipients (Figure 1E) whereas no engraftment of CMML cells was found in secondary recipient mice (Supplementary Figure S2), which may be due to a low self-renewal rate of LSC. Together, these results indicate that CMML-initiating LSC reside in a CD34+ sub-fraction of the leukemic clone.

Figure 1. CD34+ cells from CMML or sAML donors engraft in NSGS mice.

A Purified CD34+ cells from 4 donors (numbers refer to Supplementary Table S2A) were injected i.v. into sublethally irradiated NSGS mice as described in the text. After 8-12 weeks, mice were sacrificed and engraftment assessed by flow cytometry of BM cells using antibodies specific for human CD33 and CD45. A single representative mouse for each donor is shown. B,C T-cell depleted bulk MNC or purified CD34+ or CD34– cells from donors with CMML (B) or sAML (C) were injected into NSGS mice. Bars show the mean±SD of engraftment levels (i.e. percentage of human CD45+/CD33+/CD14+ cells) in all mice in each cohort. **, p<0.01 D Cytospin preparations of BM cells obtained from mice were stained using Wright-Giemsa stain. The figure shows a photograph from one representative mouse in each cohort. E BM cells from one sAML recipient mouse were sequentially injected into secondary recipient mice. A representative dot-plot demonstrating the engraftment in the primary recipient and secondary recipients is shown. Abbreviations: CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; sAML, post-CMML secondary acute myeloid leukemia; MNC, mononuclear cells.

Table 1. Summary of engraftment results in NSGS mice.

| Donor | Diagnosis | Injected Fraction | Injected cell number | Calculated LSC number | Engraftment (% CD45+/CD33+ cells) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #10 | CMML-1 | Bulk (n=5) | 3.0 x 106 | > 2.8 | 94.9 ± 0.8 % |

| CD34+ (n=3) | 0.3 x 106 | > 30.6 | 63.8 ± 3.5 % | ||

| CD34– (n=3) | 1.0 x 106 | n.a. | 0.4 ± 0.1 % | ||

| # 18 | CMML-2 | Bulk (n=5) | 3.0 x 106 | > 7.0 | 62.4 ± 19.2 % |

| CD34+ (n=3) | 0.3 x 106 | > 20.4 | 25.8 ± 24.4 % | ||

| CD34– (n=3) | 1.0 x 106 | n.a. | 1.3 ± 0.2 % | ||

| #21 | sAML | Bulk (n=5) | 1.2 x 106 | > 26.1 | 75.2 ± 37.0 % |

| CD34+ (n=5) | 0.4 x 106 | > 16.3 | 19.5 ± 41.8 % | ||

| CD34– (n=5) | 0.4 x 106 | n.a. | 0.4 ± 0.2 % | ||

| #23 | sAML | Bulk (n=5) | 7.0 x 106 | > 261.3 | 94.4 ± 3.0 % |

| CD34+ (n=3) | 1.6 x 106 | > 163.2 | 84.3 ± 1.9 % | ||

| CD34– (n=3) | 1.5 x 106 | n.a. | 0.6 ± 0.2 % |

CD3-depleted bulk BM cells or FACS-purified CD34+ or CD34– cell fractions obtained from patients with CMML or sAML were injected i.v. into NSGS mice. For detailed patient characteristics, see Supplementary Table S2. After 6 weeks (donor 10), 12 weeks (donors 18 and 23) or 25 weeks (donor 21), mice were sacrificed and engraftment evaluated by flow cytometry. The table shows a summary of these experiments including number of mice injected, number of cells injected, calculated number of LSC injected (based on LSC frequency calculations shown in Supplementary Table S3) and engraftment levels (expressed as mean±S.D. of human CD45+/CD33+ cells in the murine BM). Abbreviations: CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; sAML, post-CMML secondary acute myeloid leukemia; LSC, leukemic stem cell; n.a., not applicable.

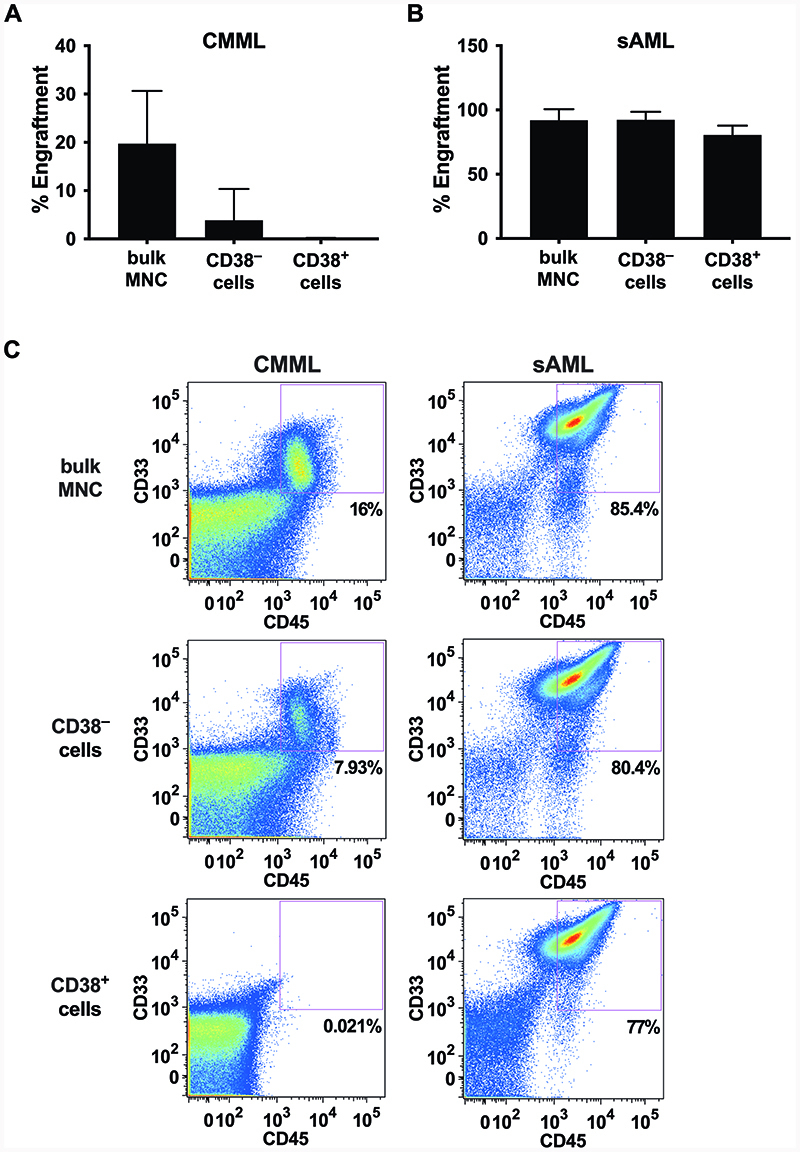

Only the CD38– fractions of CD34+ cells contain CMML LSC

We next asked whether NSGS-engrafting CMML LSC reside in a particular sub-fraction of CD34+ cells. To address this question, CMML fractions containing CD34+/CD38+ or CD34+/CD38– cells were purified by cell-sorting and then injected separately into NSGS mice. In these experiments, only the CD38– sub-fraction produced leukemic engraftment in NSGS mice, whereas CD38+ CMML cells did not engraft (Figure 2A), suggesting that CMML LSC strictly reside in a CD34+/CD38– compartment of the clone. By contrast, in patients with post-CMML sAML, leukemic engraftment was produced by both, the CD34+/CD38+ and the CD34+/CD38– sub-fraction of the leukemic clone, indicating that both fractions contained LSC, similar to the situation described in other (primary) AML variants (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Differential engraftment of CD38+ cells in CMML and sAML.

A, B MNC from a donor with CMML (A) and one with sAML (B) were separated by flow-sorting into CD38+ and CD38– fractions and subsequently injected i.v. into NSGS mice as described in ’materials and methods’. Mice were sacrificed after 8 to 12 weeks and the engraftment rate in the BM was measured by flow cytometry analysis of BM cells. The bars show the mean±SD of engraftment levels (i.e. percentage of human CD45+/CD33+/CD14+ cells) of all mice in each cohort. ***, p<0.001. C Dot plots from representative NSGS mice for each of the cohorts presented in figures 2A and 2B are shown. Abbreviations: CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; sAML, post-CMML secondary acute myeloid leukemia; MNC, mononuclear cells.

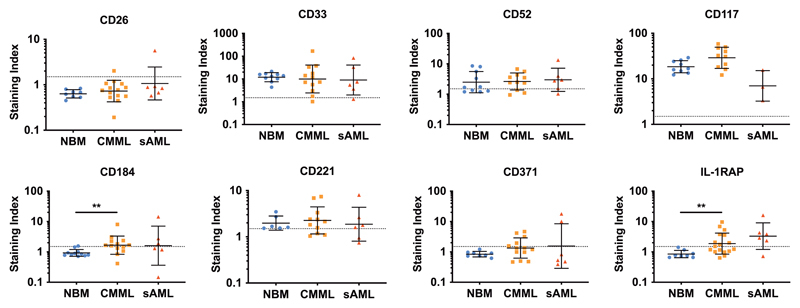

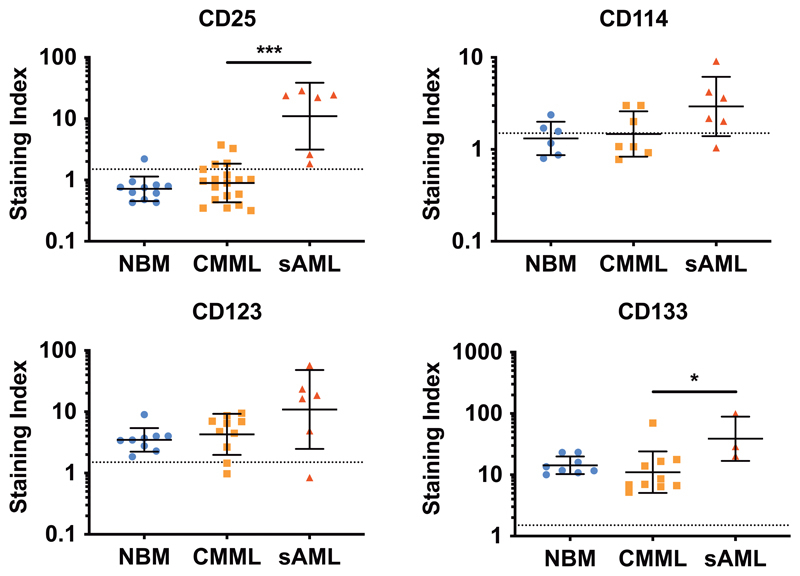

CMML LSC display a distinct cell surface phenotype

To define marker- and target expression profiles in LSC, CD34+/CD38– CMML cells and CD34+/CD38+ progenitor cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a larger panel of mAb. Several surface antigens, including CD33, CD117 (KIT), CD123, and CD133 were invariably expressed on CD34+/CD38– cells in all CMML samples tested (Figure 3 and 4). In a subset of patients, CMML LSC also expressed CD52 (8/11 patients; 73%), CD114 (3/7 patients; 43%), CD184 (8/13 patients; 62%), CD221 (8/11 patients; 73%), IL-1RAP (9/17 patients; 53%) and/or CD371 (7/13 patients; 54%). Figure 3, Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S3 show the expression levels of various surface molecules on LSC in the individual CMML donors tested. CD25 (IL2RA) and CD26 (DPPIV), both of which are expressed on CML LSC35, were not detectable on CMML LSC. Compared to normal HSC, CMML LSC displayed slightly increased levels of CD184/CXCR4 and IL-1RAP, whereas expression of CD90 was slightly lower in CMML LSC compared to HSC. Finally, we were able to show that putative CMML LSC display several immune-checkpoint molecules, including CD47 and PD-L1 (CD274) (Supplementary Figure S3) but do not express PD1 (not shown). A summary of cell surface markers expressed on CD34+/CD38– LSC in CMML, sAML and normal BM is shown in Table 2.

Figure 3. Expression of selected markers on the surface of CMML- and sAML-LSC.

BM samples from patients with CMML (n=20), sAML (n=6) or healthy control samples (normal BM = NBM, n=12) were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies against CD34, CD38 and CD45, and LSC identified as CD34+/CD38– cells (Supplementary Figure S1). Expression of markers and targets on normal BM cells (blue dots), CMML LSC (orange squares) and post-CMML sAML LSC (red triangles) was quantified by multi-color flow cytometry. Results are expressed as staining index (i.e. median fluorescence intensity of the indicated marker divided by the median fluorescence intensity of the isotype control). Each dot represents a single donor. Horizontal lines show geometric mean±SD values in each cohort. The dotted lines (at a staining index of 1.5) show the threshold above which a marker was considered to be positive. **, p<0.01. Abbreviations: NBM, normal bone marrow; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; sAML, post-CMML secondary acute myeloid leukemia; IL-1RAP, interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein.

Figure 4. Upregulation of cell surface markers on LSC during progression to sAML.

BM samples from patients with CMML (n=20), sAML (n=6) or healthy controls (NBM, n=12) were stained with antibodies against CD34, CD38 and CD45 to gate CD34+/CD38– LSC as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Afterwards, expression of markers on gated LSC was assessed by multicolor flow cytometry. Results are expressed as staining index (i.e. median fluorescence intensity of the indicated marker divided by the median fluorescence intensity of the appropriate isotype control). Each dot represents a single donor and the lines show the geometric mean±SD of the respective cohort. The dotted lines (at a staining index of 1.5) show the threshold above which a marker is considered as positive. *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001. Abbreviations: NBM, normal bone marrow; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; sAML, post-CMML secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

Table 2. Surface phenotype of LSC in CMML, sAML, and healthy hematopoietic stem cells.

| Antigen | CD | Expression on the cell surface of CD34+/CD38– cells in | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBM | CMML | sAML | ||

| IL-2RA | 25 | – | – | ++ |

| DPPIV | 26 | – | – | – |

| Siglec-3 | 33 | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| IAP | 47 | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Campath-1 | 52 | +/– | +/– | +/– |

| Thy-1 | 90 | +/– | – | – |

| C1QR1 | 93 | +/– | + | + |

| TACTILE | 96 | – | – | – |

| Endoglin | 105 | + | + | + |

| TPO-R | 110 | +/– | +/– | + |

| G-CSFR | 114 | – | – | +/– |

| M-CSFR | 115 | – | – | – |

| GM-CSFR | 116 | +/– | +/– | +/– |

| KIT | 117 | ++ | ++ | + |

| IL-3RA | 123 | + | + | ++ |

| AC133 | 133 | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| FLT-3 | 135 | +/– | +/– | + |

| CXCR4 | 184 | – | +/– | +/– |

| IGF1R | 221 | +/– | +/– | +/– |

| LNGFR | 271 | – | – | – |

| PD-L1 | 274 | + | +/– | +/– |

| KDR | 309 | – | – | – |

| CLL-1 | 371 | – | – | +/– |

| IL-1RAP | n.c. | – | +/– | + |

| EPO-R | n.c. | +/– | – | +/– |

| OSMRb | n.c. | – | – | – |

BM samples from patients with CMML (n=20), sAML (n=6) or healthy control samples (n=11) were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of the indicated markers on the surface of CD34+/CD38– cells. Results are expressed as staining index (SI; median fluorescence intensity of the marker divided by median fluorescence intensity of the corresponding isotype control) and indicate the mean SI of all patients tested in the respective cohort. SI-dependent score of staining results: –, SI<1.5; +/–, SI 1.5-3; +, SI 3-10; ++, SI >10. Abbreviations: NBM, normal bone marrow, CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; sAML, secondary AML from CMML; IL-2RA, interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain; DPPIV, dipeptidylpeptidase IV; IAP, integrin-associated protein; C1QR1, Complement activator C1q receptor 1; TACTILE, T-cell activation increased late expression; TPO-R, thrombopoietin receptor; G-CSFR, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor receptor; M-CSFR, macrophage-colony stimulating factor receptor; GM-CSFR, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor receptor; IL-3RA, interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain; FLT-3, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3; CXCR4, chemokine C-X-C motif receptor 4; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; LNGFR, low affinity nerve growth factor receptor; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; KDR, kinase insert domain receptor; CLL-1, C-type lectin like 1; IL-1RAP, interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein; EPO-R, erythropoietin receptor; OSMRb, oncostatin M receptor beta chain.

The LSC phenotype changes during progression of CMML into sAML

In sAML developing from CMML, CD34+/CD38– cells were found to display a similar phenotype compared to CMML LSC. However, several surface antigens appeared to be upregulated on LSC in sAML compared to CMML. In particular, we found that in sAML, CD34+/CD38– LSC exhibit CD25 whereas CD25 was not detectable or only expressed at trace amounts on CMML LSC. Moreover, we found that during progression from CMML to sAML, expression levels of CD114 (G-CSFR), CD123 (IL-3Ralpha) and CD133 on LSC increased (Figure 4).

Effects of targeted drugs on growth and survival of CMML LSC

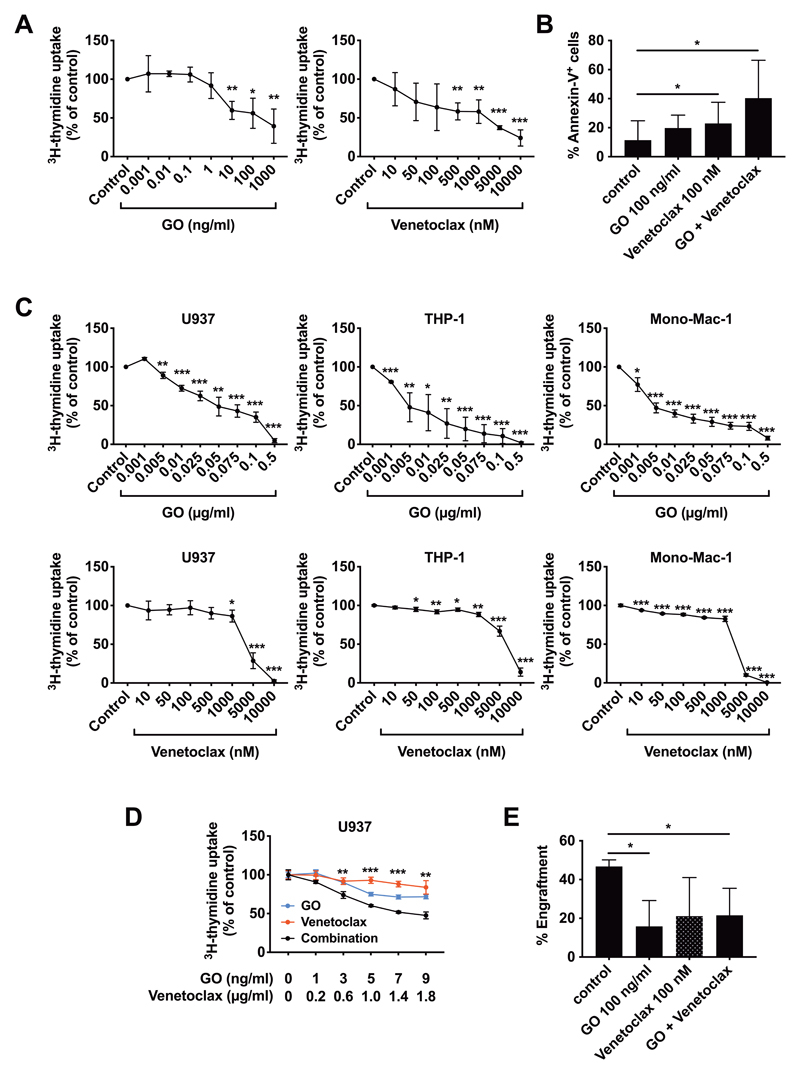

Subsequent experiments were conducted to validate therapeutically relevant targets identified in LSC. In these experiments, we used primary CMML cells and the monoblastic cell lines U937, MonoMac-6 and THP-1. In an initial screen, we found that several anti-neoplastic drugs, including GO, selinexor, ponatinib, and venetoclax, inhibit the growth of monoblastic cell lines and primary CMML cells (Supplementary Table S4). Of all drugs tested, two were found to be the most promising agents: the CD33-targeting drug GO and the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax. In vitro incubation of CMML MNC with GO or venetoclax resulted in markedly reduced proliferation (Figure 5A). Both GO and venetoclax were found to induce apoptosis in CMML LSC, and when used in combination, GO and venetoclax produced cooperative apoptosis-inducing effects on these cells (Figure 5B). Interestingly, however, there was no clear correlation between CD33 expression on CMML LSC and the percentage of apoptotic LSC after treatment with GO (R2=0.046, p>0.05) (Supplemental Figure S4). GO and venetoclax were also found to induce major growth inhibitory effects in monoblastic cell lines (Figure 5C). Furthermore, combined treatment with GO and venetoclax was found to exert cooperative inhibitory effects on proliferation of U937 cells (Figure 5D). Finally, we were able to show that exposure to GO for 1 hour interferes with engraftment of primary CMML LSC in NSGS mice, and that combined treatment with venetoclax augments the depletion of NSGS-engrafting cells (Figure 5E). These results suggest that CD33 and BCL-2 are potentially relevant targets in CMML LSC.

Figure 5. Effect of GO and Venetoclax on CMML LSC proliferation and engraftment.

A Primary MNC from the BM of 3 CMML donors were incubated in vitro with the indicated concentrations of GO (left) or venetoclax (right). After 48 hours, proliferation was measured by measuring 3H-thymidine incorporation. Results are expressed as mean±SD of the percentage of untreated control cells. B Primary MNC from the BM of 6 CMML donors were incubated with GO (100 ng/ml), venetoclax (100 nM) or a combination of the two drugs. After 48 hours, apoptosis induction was measured by flow cytometry staining for Annexin-V and DAPI. The bars show the mean±SD of Annexin-V+ cells. C The monoblastic cell lines U937 (left), THP-1 (middle), and Mono-Mac-1 (right) were treated with the indicated concentrations of GO (top) or venetoclax (bottom). After 48 hours, proliferation was measured by measuring 3H-thymidine incorporation. The results are expressed as mean±SD of the percentage of untreated control cells. D U937 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of GO (blue line), venetoclax (red line), or a combination of the two drugs (black line). After 48 hours, proliferation was measured by measuring 3H-thymidine incorporation. Results are expressed as mean±SD of the percentage of untreated control cells. E T-cell depleted MNC from a CMML donor were incubated with GO (100 ng/ml), venetoclax (100 nM) or a combination of both drugs for 1 hour. Afterwards, drugs were removed by centrifugation and cells were injected i.v. into NSGS mice. After 28 weeks, mice were sacrificed and engraftment measured by flow cytometry. Bars show the mean±SD of the engraftment levels (percentage of human CD45+/CD33+ cells) in all mice in each cohort.

*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. Abbreviations: CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; MNC, mononuclear cells; GO, gemtuzumab-ozogamicin.

Discussion

Although CMML is considered a stem cell-derived BM neoplasm, little is known about the phenotype, function and target expression profiles of disease-initiating LSC in this malignancy. Recent data suggest that CMML LSC can engraft NSGS mice.40,41 Building on this observation we established the phenotype of NSGS-engrafting CMML LSC. We found that CD34+ CMML cells engraft NSGS mice with an overt leukemia whereas the bulk of CD34– cells, including all mature monocytic CMML cells, were unable to engraft NSGS mice. Corresponding results were obtained with cells derived from sAML patients. These data formally establish that CMML stem cells reside in a CD34+ subpopulation. In subsequent studies we found that NSGS-engrafting CMML cells reside in the CD34+/CD38– sub-fraction of CMML cells whereas CD34+/CD38+ cells were unable to engraft NSGS mice.

In most variants of de novo AML, NSG-engrafting LSC can be detected in both the CD34+/CD38– and the CD34+/CD38+ subset of clonal cells. In this study, we examined samples from patients who progressed from CMML to sAML. In these experiments we found that the NSGS-engrafting sAML LSC reside in both, the CD34+/CD38– and the CD34+/CD38+ subsets of the clone similar to other (de novo) AML types. We also asked whether sAML LSC can reside in a CD34-negative population. However, in all sAML donors and samples tested, only the CD34+ fractions of neoplastic cells, but not the CD34-negative cells or the enriched (sorted) CD14+ monocytes, engrafted NSGS mice.

In the normal BM and in chronic phase CML, stem cells reside in a CD38– sub-fraction whereas the more mature progenitor cells lack stem cell (LSC) function.23,27 By contrast, in acute leukemias, both the CD38– and CD38+ sub-populations usually exhibit long-term repopulating capacity indicative of stem cell function.32 In the current study, we were able to confirm this concept in CMML. In fact, in the CMML samples, only the CD38– but not the CD38+ progenitor cells engrafted NSGS mice, whereas in sAML arising from CMML, both the CD34+/CD38– and CD34+/CD38+ fractions of the malignant clone produced AML-like engraftment.

We used NSGS mice in our experiments because of their specific ability to engraft CMML cells. So far, it remains unknown why CMML and post-CMML AML samples do not engraft in conventional NSG mice.40,41 The most likely explanation is that the full cytokine support (GM-CSF, IL-3 and SCF) is required for engraftment of CMML stem cells. This hypothesis is in line with previous observations suggesting that GM-CSF is an essential growth factor for CMML progenitors.42 Moreover, we were able to confirm that the CD34+/CD38– CMML LSC display receptors for these cytokines. We also tested additional mouse strains expressing human GM-CSF or other cytokines, but we were unable to document leukemic engraftment of CMML LSC in these mice (Supplementary Table S5) suggesting that NSGS mice and the cytokine combination in these mice are essential for optimal leukemic engraftment with CMML (stem) cells. In contrast, the other mouse models were less permissive or less able to engraft within a certain time frame. For example, when testing MISTR-G and MITR-G mice43, we observed that most of the injected mice develop a severe lung disease (pulmonary alveolar proteinosis) before an engraftment was seen. Therefore, in these mice (MISTRG and MITRG) injections are often performed in juvenile mice in order to make sure that engraftment can be documented.43

Next we asked whether the engrafted cells reflect the underlying disease. Indeed, we found the engrafting cells mirrored the phenotype of neoplastic cells observed in the donor samples and thus the donor’s disease. Recipient mice receiving cells of CMML samples engrafted with a mixture of immature and mature monocytes and a few blast cells as well as eosinophils and basophils, whereas engraftment of samples derived from sAML patients consisted predominantly of blast cells, indicating that the observed engraftment in these mice was indeed derived from leukemic cells (LSC) but not from residual healthy HSC. The possibility that a substantial number of engrafted cells were normal monocytic cells in our CMML samples seems very unlikely. In fact, although normal stem cells and CMML LSC showed overlapping phenotypes and some of the injected cells might indeed have been normal cells, healthy stem cells usually exhaust after a few months whereas leukemic stem cells can still engraft after several months in NSG mice. In line with this concept, the engrafted cells detected in our experiments were immature monocytes by morphology and phenotyping.

The detection of basophils and eosinophils in the mouse BM is in line with the notion that GM-CSF and IL-3 are major growth factors for human basophils and eosinophils.44,45

As mentioned, the phenotype of CMML LSC was found to be similar to the phenotype of normal HSC. Apart from being CD45+/CD34+/CD38– cells, CMML LSC also expressed other stem cell markers such as CD117 (KIT), CD123 and CD133 at levels comparable to that seen in BM HSC. Other markers, such as CD184 and IL-1RAP, showed increased expression on CMML LSC, similar to the phenotype of LSC in patients with de novo AML and post-CMML sAML. CD25 and CD26, established LSC markers in CML, were completely absent from CMML LSC. However, after progression to sAML, LSC showed a marked upregulation of CD25. The molecular basis of the increase in cytokine receptor expression remains unknown. Since CD25 is a STAT5-target gene in LSC46,47 and STAT5 is a well-known driver in AML48,49, an attractive hypothesis would be that oncogenic signaling through STAT5 promotes expression of CD25 in post-CMML sAML LSC.

All these data were obtained in in vitro studies. However, the situation in vivo may be more complex, and LSC evolution may be affected by additional factors relevant to the BM microenvironment and the local immune system. In fact, recent data suggest that dendritic cells (often forming aggregates in these conditions), other niche cells, and immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-L1 or indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO) play a role in the evolution of MDS and CMML.50,51 Further studies will be necessary to assess the exact impact of these molecules on progression to sAML and responsiveness of LSC to targeted drugs in vivo.

In a final step, we evaluated the effects of various targeted drugs, including GO and venetoclax, on CMML LSC. In line with the notion that CMML LSC (and more mature clonal CMML cells) invariably expressed CD33, GO was found to inhibit the proliferation of primary CMML cells and growth of various monoblastic cell lines at low concentrations, with IC50 values ranging between 100 and 500 ng/ml. In addition, GO was found to induce apoptosis in CMML LSC. Surprisingly, we were not able to demonstrate a clear correlation between CD33 expression on CMML LSC and the percentage of apoptotic LSC after treatment with GO (Supplementary Figure S4). This observation may be explained by the fact that low levels of surface CD33 are sufficient to mediate GO effects.

Interestingly, venetoclax showed less pronounced effects in the monoblastic cell lines (IC50 between 5 and 10 μM), but was very effective in inhibiting the proliferation of primary CMML cells (IC50: 10-100 nM), indicating that BCL-2-mediated survival signals become less important once progression to sAML has occurred. However, the combination of GO and venetoclax proved to be superior in growth inhibition over either substance alone in all models tested. Clinically, combinations of venetoclax with demethylating agents such as azacytidine are effective in AML, including sAML following CMML.52 Our data suggest that venetoclax as a single agent or combined with GO should be evaluated in clinical studies in patients with chronic phase CMML. In conclusion, we have identified NSGS-engrafting leukemia-initiating stem cells (LSC) in CMML and show that these cells reside in a CD45+/CD34+/CD38– fraction of CMML cells. During transformation from CMML to sAML, the LSC acquire a phenotype that is more closely resembling the phenotype seen in de novo AML. In both CMML and sAML, LSC display a number of molecular targets. Finally, we show that LSC in CMML and sAML are susceptible to GO and venetoclax, providing a rationale for clinical studies in CMML.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We like to thank Christiana Winding, Tina Bernthaler and Siegfried Kosik for skillful technical assistance. This study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), grants F4704-B20, P30625-B28, and a Research Grant of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria. Cell sorting experiments were performed with support from the Core Facility Flow Cytometry, Medical University of Vienna.

Footnotes

Contributions

G.E., I.S., and P.V. designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. G.E., B.P., I.S., A.K., D.I., K.B., D.B., and G.S. performed key laboratory experiments. P.B., H.S., K.G., K.V.G, W.R.S., and M.D. provided patients’ samples and clinical information. G.G. performed and analyzed molecular studies. M.W., K.S. and T.R. performed animal experiments. All authors wrote parts of the manuscript, corrected the draft version of the manuscript and approved the final version of the document.

Disclosure

P.V. received honoraria from Pfizer. H.S. received honoraria from Pfizer and AbbVie. M.D. received honoraria from Pfizer and Incyte. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Storniolo AM, Moloney WC, Rosenthal DS, Cox C, Bennett JM. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 1990;4:766–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al. Proposals for the classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 1982;51:189–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick H, et al. The chronic myeloid leukaemias: guidelines for distinguishing chronic granulocytic, atypical chronic myeloid, and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Proposals by the French-American-British Cooperative Leukaemia Group. Br J Haematol. 1994;87:746–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb06734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patnaik MM, Parikh SA, Hanson CA, Tefferi A. Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia: a concise clinical and pathophysiological review. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:273–286. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCullough KB, Patnaik MM. Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia: a Genetic and Clinical Update. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10:292–302. doi: 10.1007/s11899-015-0271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Beau MML, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orazi A, Bennett JM, Germing U, Brunning RD, Bain BJ, Cazzola M, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press; 2017. Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohlmann A, Grossmann V, Klein H-U, Schindela S, Weiss T, Kazak B, et al. Next-generation sequencing technology reveals a characteristic pattern of molecular mutations in 72.8% of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by detecting frequent alterations in TET2, CBL RAS, and RUNX1. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3858–3865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itzykson R, Duchmann M, Lucas N, Solary E. CMML: Clinical and molecular aspects. Int J Hematol. 2017;105:711–719. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2243-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Chronic Myelomonocytic leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:97–115. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pich A, Riera L, Sismondi F, Godio L, Davico Bonino L, Marmont F, et al. JAK2V617F activating mutation is associated with the myeloproliferative type of chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:798–801. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.065904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gur HD, Loghavi S, Garcia-Manero G, Routbort M, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Quesada A, et al. Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia With Fibrosis Is a Distinct Disease Subset With Myeloproliferative Features and Frequent JAK2 p.V617F Mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:799–806. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperr WR, Horny H-P, Valent P. Spectrum of associated clonal hematologic non-mast cell lineage disorders occurring in patients with systemic mastocytosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:140–142. doi: 10.1159/000048186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sotlar K, Fridrich C, Mall A, Jaussi R, Bültmann B, Valent P, et al. Detection of c-kit point mutation Asp-816 --> Val in microdissected pooled single mast cells and leukemic cells in a patient with systemic mastocytosis and concomitant chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2002;26:979–984. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valent P, Orazi A, Savona MR, Patnaik MM, Onida F, van de Loosdrecht AA, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for classical chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), CMML variants and pre-CMML conditions. Haematologica. 2019;104:1935–1949. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.222059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patnaik MM, Vallapureddy R, Lasho TL, Hoversten KP, Finke CM, Ketterling RP, et al. A comparison of clinical and molecular characteristics of patients with systemic mastocytosis with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia to CMML alone. Leukemia. 2018;32:1850–1856. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itzykson R, Kosmider O, Renneville A, Gelsi-Boyer V, Meggendorfer M, Morabito M, et al. Prognostic score including gene mutations in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2428–2436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elena C, Gallì A, Such E, Meggendorfer M, Germing U, Rizzo E, et al. Integrating clinical features and genetic lesions in the risk assessment of patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;128:1408–1417. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-714030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palomo L, Garcia O, Arnan M, Xicoy B, Fuster F, Cabezón M, et al. Targeted deep sequencing improves outcome stratification in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with low risk cytogenetic features. Oncotarget. 2016;7:57021–57035. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itzykson R, Fenaux P, Bowen D, Cross NCP, Cortes J, De Witte T, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemias in Adults: Recommendations From the European Hematology Association and the European LeukemiaNet. Hemasphere. 2018;2:e150. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kröger N, Zabelina T, Guardiola P, Runde V, Sierra J, Van Biezen A, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation of adult chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. A report on behalf of the Chronic Leukaemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Br J Haematol. 2002;118:67–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Witte T, Bowen D, Robin M, Malcovati L, Niederwieser D, Yakoub-Agha I, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for MDS and CMML: recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:1753–1762. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-06-724500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dick JE, Lapidot T, Pflumio F. Transplantation of normal and leukemic human bone marrow into immune-deficient mice: development of animal models for human hematopoiesis. Immunol Rev. 1991;124:25–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisterer W, Jiang X, Christ O, Glimm H, Lee KH, Pang E, et al. Different subsets of primary chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells engraft immunodeficient mice and produce a model of the human disease. Leukemia. 2005;19:435–441. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kavalerchik E, Goff D, Jamieson CHM. Chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2911–2915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause DS, Van Etten RA. Right on target: eradicating leukemic stem cells. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misaghian N, Ligresti G, Steelman LS, Bertrand FE, Bäsecke J, Libra M, et al. Targeting the leukemic stem cell: the Holy Grail of leukemia therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23:25–42. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Copland M. Chronic myelogenous leukemia stem cells: What’s new? Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2009;4:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s11899-009-0010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valent P. Targeting of leukemia-initiating cells to develop curative drug therapies: straightforward but nontrivial concept. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:56–71. doi: 10.2174/156800911793743655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taussig DC, Miraki-Moud F, Anjos-Afonso F, Pearce DJ, Allen K, Ridler C, et al. Anti-CD38 antibody-mediated clearance of human repopulating cells masks the heterogeneity of leukemia-initiating cells. Blood. 2008;112:568–575. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamieson CHM, Ailles LE, Dylla SJ, Muijtjens M, Jones C, Zehnder JL, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors as candidate leukemic stem cells in blast-crisis CML. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:657–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Järås M, Johnels P, Hansen N, Agerstam H, Tsapogas P, Rissler M, et al. Isolation and killing of candidate chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells by antibody targeting of IL-1 receptor accessory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16280–16285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004408107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrmann H, Sadovnik I, Cerny-Reiterer S, Rülicke T, Stefanzl G, Willmann M, et al. Dipeptidylpeptidase IV (CD26) defines leukemic stem cells (LSC) in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:3951–3962. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-536078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito Y, Kitamura H, Hijikata A, Tomizawa-Murasawa M, Tanaka S, Takagi S, et al. Identification of Therapeutic Targets for Quiescent, Chemotherapy-Resistant Human Leukemia Stem Cells. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2:17ra9–17ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hosen N, Park CY, Tatsumi N, Oji Y, Sugiyama H, Gramatzki M, et al. CD96 is a leukemic stem cell-specific marker in human acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11008–11013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704271104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Rhenen A, van Dongen GAMS, Kelder A, Rombouts EJ, Feller N, Moshaver B, et al. The novel AML stem cell associated antigen CLL-1 aids in discrimination between normal and leukemic stem cells. Blood. 2007;110:2659–2666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-083048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Pang WW, Jaiswal S, Gibbs KD, et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, He L, Selimoglu-Buet D, Jego C, Morabito M, Willekens C, et al. Engraftment of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia cells in immunocompromised mice supports disease dependency on cytokines. Blood Adv. 2017;1:972–979. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017004903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshimi A, Balasis ME, Vedder A, Feldman K, Ma Y, Zhang H, et al. Robust patient-derived xenografts of MDS/MPN overlap syndromes capture the unique characteristics of CMML and JMML. Blood. 2017;130:397–407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-01-763219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramshaw HS, Bardy PG, Lee MA, Lopez AF. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia requires granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for growth in vitro and in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:1124–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00903-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rongvaux A, Willinger T, Martinek J, Strowig T, Gearty SV, Teichmann LL, et al. Development and function of human innate immune cells in a humanized mouse model. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:364–372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valent P, Schmidt G, Besemer J, Mayer P, Zenke G, Liehl E, et al. Interleukin-3 is a differentiation factor for human basophils. Blood. 1989;73:1763–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saito H, Hatake K, Dvorak AM, Leiferman KM, Donnenberg AD, Arai N, et al. Selective differentiation and proliferation of hematopoietic cells induced by recombinant human interleukins. PNAS. 1988;85:2288–2292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadovnik I, Hoelbl-Kovacic A, Herrmann H, Eisenwort G, Cerny-Reiterer S, Warsch W, et al. Identification of CD25 as STAT5-Dependent Growth Regulator of Leukemic Stem Cells in Ph+ CML. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2051–2061. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadzijusufovic E, Keller A, Berger D, Greiner G, Wingelhofer B, Witzeneder N, et al. STAT5 is Expressed in CD34+/CD38− Stem Cells and Serves as a Potential Molecular Target in Ph-Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Cancers. 2020;12:1021. doi: 10.3390/cancers12041021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wingelhofer B, Neubauer HA, Valent P, Han X, Constantinescu SN, Gunning PT, et al. Implications of STAT3 and STAT5 signaling on gene regulation and chromatin remodeling in hematopoietic cancer. Leukemia. 2018;32:1713–1726. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0117-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wingelhofer B, Maurer B, Heyes EC, Cumaraswamy AA, Berger-Becvar A, de Araujo ED, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of STAT5 in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2018;32:1135–1146. doi: 10.1038/s41375-017-0005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Müller‐Thomas C, Heider M, Piontek G, Schlensog M, Bassermann F, Kirchner T, et al. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase in patients with higher‐risk myelodysplastic syndromes treated with azacytidine. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:361–370. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mangaonkar AA, Reichard KK, Binder M, Coltro G, Lasho TL, Carr RM, et al. Bone marrow dendritic cell aggregates associate with systemic immune dysregulation in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood Advances. 2020;4:5425–5430. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lou Y, Shao L, Mao L, Lu Y, Ma Y, Fan C, et al. Efficacy and predictive factors of venetoclax combined with azacitidine as salvage therapy in advanced acute myeloid leukemia patients: A multicenter retrospective study. Leuk Res. 2020;91:106317. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.