Abstract

Objectives

Glycosylation of immunoglobulin G (IgG) is an important regulator of the immune system and has been implicated in prevalent hypertension.The aim of this study is to investigate whether the IgG glycome begins to change prior to hypertension diagnosis by analysing the IgG glycome composition in a large population-based female cohort with 2 independent replication samples.

Methods

We included 989 unrelated cases with incident hypertension and 1628 controls from the TwinsUK cohort (mean follow-up time of 6.3 years) with IgG measured at baseline by ultra-performance liquid chromatography and longitudinal BP measurement available. We replicated our findings in 106 individuals from the 10 001 Dalmatians and 729 from KORA S4. Cox regression mixed models were applied to identify changes in glycan traits pre-incident hypertension, after adjusting for age, mean arterial pressure, body mass index, family relatedness and multiple testing (FDR < 0.1). Significant IgG-incident hypertension associations were replicated in the two independent cohorts by leveraging Cox regression mixed models in the 10 001 Dalmatians and logistic regression models in the KORA cohort.

Results

We identified and replicated 4 glycan traits, incidence of bisecting GlcNAc, GP4, GP9 and GP21, that are predictive of incident hypertension after adjusting for confoundes and multiple testing (HR[95%CI] ranging from 0.45[0.24;0.84] for GP21 to 2.9[1.5;5.68]) for GP4). We then linearly combined the four replicated glycans and found that the glycan score correlated with incident hypertension, SBP and DBP.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the IgG glycome changes prior to the development of hypertension.

Keywords: Basic Science Research, Biomarkers, Risk factors, incident hypertension, glycomics

1.0. Introduction

Hypertension is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. The risk factors for hypertension are multifactorial and include both genetic predisposition and environmental or lifestyle factors, like salt intake, diet, alcohol use, and sedentary behaviour [1,2].

N-glycans are complex carbohydrate structures added to the protein backbone via the process of N-glycosylation and are one of the main contributors to protein structural and functional properties [3]. Most of the known proteome contains glycans [4], which are highly responsive to both environmental and genetic stimuli and frequently change in response to various pathophysiological conditions including cardiovascular diseases (CVD). We recently reported that certain plasma N-glycan traits can be leveraged to improve the accuracy of established CVD risk prediction models, thereby suggesting that N-glycans are sensitive to processes involved in early disease development [5]. Animal and cross-sectional human studies also suggest that alterations of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) N-glycome, which is known to influence inflammatory response [6], may be involved in both hypertension and blood pressure regulation [7], subclinical atherosclerosis and atherosclerosis risk factors [8]. In our recent paper measuring 76 IgG glycan traits plus GlycA in two independent cohorts in the UK [8], we described the association of four IgG traits, in addition to the previously reported GlycA, with measures of atherosclerosis. In the same study, we also presented IgG N-glycans’ incremental predicitive value when combined with the ACC/AHA risk score [8]. These findings suggest that changes to the IgG glycome could be a novel biomarker to predict incident hypertension.

Here, we aimed to investigate changes in IgG glycans and incident hypertension by analysing the IgG glycome composition in a large population-based female cohort from the TwinsUK with longitudinal glycomics and blood pressure (BP) data. We then replicated the glycan-associated traits in two independent samples from the 10 001 Dalmatians study and KORA S4 cohort.

2.0. Methods

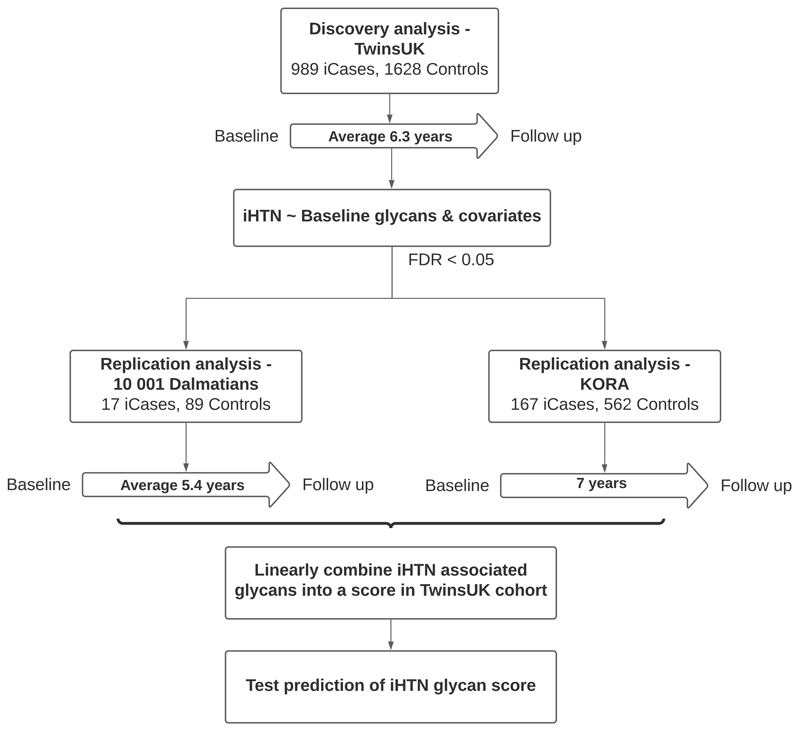

A flowchart of the study design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart of study design.

iCases = incident hypertension cases

2.1. Study population

Discovery cohort

Study subjects were individuals enrolled in the TwinsUK registry, a national register of adult twins recruited as volunteers without selecting for any particular disease or traits [9]. Here we analysed data from 2617 females (989 incident hypertension cases, 1628 controls) (mean follow-up time of 6.3 years). Data relevant to the present study include BP (at baseline and follow-up), antihypertensive drug use, body mass index (BMI), mean arterial pressure (MAP), age, and IgG glycans assessed using HILIC-UPLC-FLR, as described below.

Replication cohorts

We replicated our results in two independent samples, the 10 001 Dalmatians study [10] and the KORA cohort [11].

10 001 Dalmatians

We included 106 subjects from the “10 001” Dalmatians study, a study designed to investigate the health of the isolated island communities, including the Croatian islands of Vis, Korčula and Split [10]. Included subjects had all relevant measures including, age, sex, BMI and IgG glycans quantified by HILIC-UPLC-FLR, with an average follow up time of 5.4 years.

KORA

We further replicated in 729 individuals with relevant measures and IgG glycans measured using LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis from KORA F4 which is the first follow-up study of the population-based KORA S4 study (Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg) [11]. The covariates included were age, sex, BMI and MAP at the time of KORA F4. Blood pressure is measured in KORA FF4 which is the second follow up study of KORA S4 carried out 7 years after KORA F4.

2.2. Phenotype Definitions

Blood pressure was measured by a trained nurse using either the Marshall mb02, the Omron Mx3 or the Omron HEM713C Digital Blood Pressure Monitor (Coefficial of Variation =8.4%). Measurements were performed with the patient in the sitting position for at least 3 minutes. At each visit, the cuff was placed on the subject’s arm so that it was approximately 2–3 cm above the elbow joint of the inner arm. Measurements were carried out with the subject’s arm resting on a table ensuring that the cuff was placed at the same level of the heart. Three measurements were taken with an interval of approximately 1 minute between each reading, with the mean of the second and third measurements recorded to mitigate white coated effect.

In the three cohorts BP was measured at baseline and longitudinally (average follow-up time 6.3 (± 3.7) years in TwinsUK). Subjects were classified as hypertensive cases based on their BP level (systolic BP (SBP) >140 mmHg OR diastolic BP (DBP) >90 mmHg), use of BP lowering drugs, or a recorded diagnosis of hypertension by the doctor. Based on the above definition, hypertension was defined as prevalent or incident and all individuals with prevalent hypertension at baseline excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Ethical statement

TwinsUK, 10 001 Dalmatians and KORA cohorts were designed following the Declaration of Helsinki and were given approval by their local ethical committees. For TwinsUK, volunteers provided informed written consent and the study was approved by St. Thomas’ Hospital Research Ethics Committee (REC Ref: EC04/015). For KORA, all study participants provided written informed consent and approval was granted from the Bavarian Medical association Ethics committee (Bayerische Landesärzte-kammer) and the Bavarian commissioner for data protection and privacy (Bayerischer Datenschutzbeauftragter). The 10 001 Dalmatians study received ethical approval from the ethics committee of the Sisters of Mercy University Hospital in Zagreb and all participants provided informed consent.

2.4. Analysis of the IgG N-glycoprofile

IgG Isolation was performed on protein G monolithic 96-well plates as previously described [12]. Detailed description of the isolation protocol is available in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material: EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOL DESCRIPTION).

IgG N-glycoprofiling of the TwinsUK cohort

Deglycosylation, RapiFluor-MS labelling and purification step of IgG N-glycans was performed using GlycoWorks RapiFluor-MS N-Glycan Kit obtained from Waters Corporation (Milford, USA), in compliance with the manufacturer’s protocol [13]. All samples containing eluted and labelled glycans were stored at -20 °C until further use. RapiFluor-MS labelled IgG N-glycans were analysed using HILIC-UPLC-FLR on Water Acquity UPLC H-class instruments. Detailed description of the analysis is available in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material: EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOL DESCRIPTION).

IgG N-glycoprofiling of the 10 001 Dalmatians cohort

Deglycosylation, 2-AB (Merck, Germany) labelling and purification step of IgG N-glycans was performed following our standardised protocol as described in detail by Jurić and colleagues [14]. At the end of the protocol, the samples containing eluted and labelled glycans were stored at -20 °C until further use. 2-AB labelled IgG N-glycans were analysed using HILIC-UPLC-FLR on Water Acquity UPLC H-class instruments. Detailed description of the analysis is available in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material: EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOL DESCRIPTION).

IgG N-glycoprofiling of the KORA cohort

Digestion of IgG to tryptic glycopeptides and their following purification was performed as described previously [15]. Purified tryptic IgG glycopeptides-containing eluates were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and then dissolved with a volume of 20 μL of ultrapure water. Detailed description of LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of the IgG glycopeptides from the KORA cohort is available in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material: EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOL DESCRIPTION).

The chromatograms were all separated in the same manner into peaks and the amount of glycans in each peak was expressed as percentage of total integrated area (Supplementary Table 1). In addition to directly measured glycan structures, derived traits were calculated as described in Supplementary Table 2. These derived traits average particular glycosylation features such as, galactosylation, fucosylation, and sialylation, across different individual glycan structures. Consequently, they are more closely related to individual enzymatic activities and underlying genetic polymorphisms [16,17].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.6.3 [18]. Glycans were global normalised and log transformed because of a right-skewed distribution. To adjust for technical biases, all measurements were adjusted for batch and run-day effects using the R-package sva [19]. Derived glycan traits were calculated using normalized and batch-corrected glycan measurements (exponential of batch-corrected measurements). Glycan variables were transformed to standard normal distribution by inversion transformation of ranks (R package “GenABEL”) [20].

In the discovery cohort, Cox regression mixed models (R package “coxme” [21]) were used to identify changes in glycans before incident hypertension, with an average follow-up time of 6.3 (± 3.7) years, after adjusting for age, MAP, BMI, family relatedness and multiple testing (FDR<0.1) (Figure 1).

Cox regression mixed models were further employed to replicate the hypertension-associated glycans in the 10 001 Dalmatians cohort. In the KORA cohort, all study participants had the same follow up time, hence we used logistic regressions to replicate the associated glycans. IgG glycans were considered replicated if p < 0.05 and direction of effects were consistent (Figure 1).

To assess the combined effects of the incident-hypertension associated glycans on BP phenotypes, we generated a score by linearly combining the transformed glycan traits from the TwinsUK cohort alongside covartiates. (Figure 1).

3.0. Results

The demographic characteristics of the study populations are presented in Table 1. Here, we measured baseline and follow-up (1 to 19 years) levels of 20 directly measured and 10 derived glycan traits in 2617 subjects from the TwinsUK cohort, 106 individuals from the Dalmatians study and 729 participants from KORA. Description of the glycan structures and formulas used for the calculation of glycan traits are available in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2 respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Cohort | TwinsUK | 10 001 Dalmatians | KORA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timepoint | Baseline | Follow up | Baseline | Follow up | Baseline | Follow up | |||

| Hypertension status | All | Controls | iCases | All | Controls | iCases | All | Controls | iCases |

| N | 2617 | 1628 | 989 | 106 | 89 | 17 | 729 | 562 | 167 |

| Females, N (%) | 2617 (100%) | 1628(100%) | 989(100%) | 72 (68%) | 63(71%) | 9 (53%) | 415 (57%) | 330 (59%) | 85 (51%) |

|

Age / years

Mean (SD) |

54 (12) | 58 (11) | 63 (9) | 57 (11) | 62 (12) | 62 (7) | 58 (8) | 64 (8) | 67 (8) |

|

BMI / kg m-2

Mean (SD) |

25.7 (4.5) | 25.3 (4.4) | 27.4 (5.2) | 27.7 (3.8) | NA | NA | 26.7 (4.0) | 26.7 (4.1) | 28.5 (5.1) |

|

SBP / mmHg,

Mean (SD) |

122 (14) | 119 (11) | 137 (13) | 132 (17) | 127 (10) | 152 (7) | 117 (13) | 114 (13) | 125 (19) |

|

DBP / mmHg

Mean (SD) |

76 (9) | 72 (8) | 81 (10) | 79 (8) | 78 (6) | 85 (10) | 74 (7) | 71 (7) | 75 (11) |

|

MAP / mmHg

Mean (SD) |

91 (10) | 88 (8) | 100 (9) | 97 (10) | 94 (6) | 107 (8) | 88 (9) | 86 (8) | 91 (13) |

Abbreviations: iCases, incident hypertension cases; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

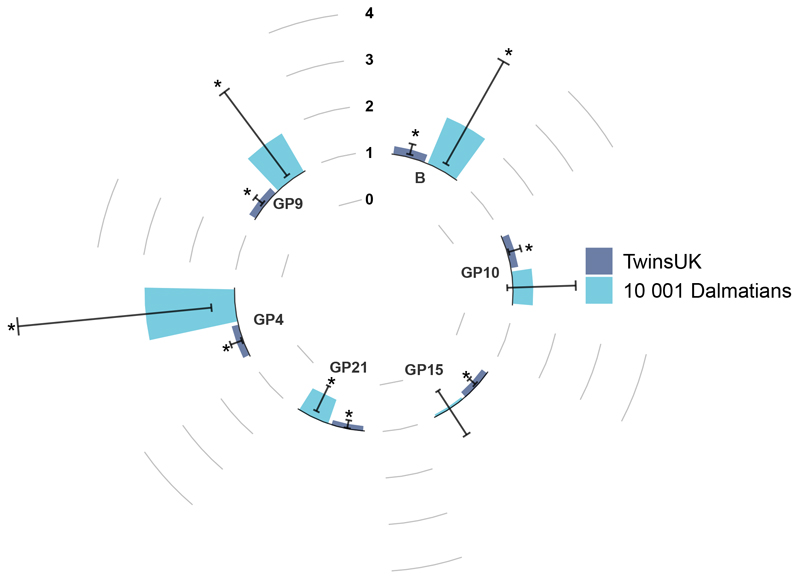

In the discovery cohort, we identify 6 IgG glycan traits (B, GP4, GP9, GP10, GP15, GP21) associated with an increased risk of incident hypertension after adjusting for covariates and multiple testing (FDR < 0.1) (Figure 2 & Supplementary Table 3). Results are consistent when further adjusting for diet (as measured by the Healthy Eating Index), physical activity, type 2 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis (at p<0.5 for B, GP9, GP15, GP21, p<0.1 for GP4 and GP10).

Figure 2. Hazard ratio’s for each glycan trait in incident hypertension. Bars represent hazard ratios and error bars represent 95% confidence interval as represented by each sample.

* denotes an FDR <0.1 in TwinsUK and a p < 0.05 and same direction in Dalmatians 10 001. Odds ratio’s for KORA S4 validation can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

We then validated the hypertension associated glycan traits in both the Dalmatians and KORA cohort. Four of the 6 glycan traits (B, GP4, GP9 and GP21) were replicated (p < 0.05) in the Dalmatians cohort using Cox models after adjusting for covariates in the overall cohort (HR[95%CI]; B = 2.07[1.16;3.68], p= 0.014; GP4 =2.92[1.50;5.68], p= 0.002; GP9 = 1.94[1.12;3.36], p= 0.019; GP21 = 0.45[0.24;0.84], p= 0.012) and in the female only sample (Figure 2 & Supplementary Table 3,Supplementary Table 4). Due to technical differences in the quantification of the glycome, of the 4 previously replicated glycan traits, only B and GP4 were measured in KORA and results showed consistent effects (OR[95%CI]; B = 1.20[0.99;1.46], p= 0.06; GP4 = 1.28[1.04;1. 58], p= 0.02) (Supplementary Table 3). Though the association with B was borderline significant in the KORA cohort, we found loss of information due to the unnecessary rank transformation we used in KORA for consistency. Indeed, when we run the analysis on the untransformed bisecting glycan (B) the association was nomincally significant (2.15[1.07;4.29]; p= 0.03).

To assess the combined effect of the four associated glycans on incident hypertension, we linearly combined the glycan traits and covariates to compute a glycan score as illustrated below in TwinsUK.

This linear combination was associated with incident hypertension in a binomical mixed effect logistic regression model (BETA[SE], p = 0.85[0.06], 2 x 10−16), and with i) SBP at follow up (BETA[SE], p = 3.88[0.16], 2 x 10−16), ii) DBP at follow up (BETA[SE], p = 1.1[0.12], 2 x 10−16) in a linear mixed effect regression model.

Likelihood ratio tests between the full model (including the 4 glycans and covariates, and the null model showed that the inclusion of the four replicated glycans significantly improves the quality of the model (loglik; FULL = -7644.2, NULL = -7440.4, p= 2.2 x 10−16). Using a time-dependent ROC curve, we also see a marginal improvement of 0.4% in the predictive value through the inclusion of our hypertension-associated glycan traits in comparison to our NULL model (AIC; FULL = 0.983, NULL = 0.979).

4.0. Discussion

Here we report that the baseline IgG N-glycome is predictive of incident hypertension. We identified 6 incident hypertension associated glycan traits in TwinsUK and independently replicated 4 to contribute to hypertension prediction, namely, B (incidence of bisecting GlcNAc), GP4, GP9 and GP21 (Figure 2). B and GP4 were validated also in KORA, where glycans were measured using a different analytical method and report concordant direction of effect for both glycans (Supplementary Table 3).

We find three of the 4 replicated glycan traits (B, GP4 and GP9) were significantly increased in individuals who developed hypertension during follow-up when compared to those defined as controls, whereas only GP21 was decreased. B, GP4 and GP9 represent simple glycan structures containing core fucose with only one or no galactose residues attached to the bisecting GlcNAc. Alternatively, GP21 is a more complex digalactosylated structure with two sialic acid residues attached to the galactose molecules, but without the bisection [12]. Furthermore, the linear combination of these 4 glycan traits correlated with incident hypertension, SBP and DBP and showed a small but significant improvement in AUC in predicting hypertension.

Our results are consistent and supported by the current literatature. Indeed, in a cross-sectional study of an ethnically diverse sample from China, Croatia and Scotland, Wang and collaborators reported positive correlations between GP4 and cross-sectional hypertension [4]. Additionally, incidence of bisecting GlcNAc, GP4, GP9 and GP21 have previously been associated with metabolic phenotypes, including dyslipidaemia [22,23], BMI [23], inflammation [24], obesity [25], and aging [26,27]. This suggests the glycomes involvement in contributing to a dyshomeostatic, pro-inflammatory environment, a recognised state involved in hypertension [28]. Moreover, in hypertensive mice (via an infusion of angiotensin II), Chan et al. [29] report an increase in circulating IgG, which accumulates in the aortic adventia. This increase was further linked to B cell activation [29]. B cells are a component of the adaptive immune system, an important player in renal and vascular inflammation [30]. Mice deficient in B cell-activating receptor showed no increase in circulating IgG or SBP [29].

Our study benefits from a large sample size, the longitudinal nature of our data that allowed us to investigate longitudinal changes, and the presense of multiple independent replication samples of diverse European origins. Nevertheless, our study also has some limitations. Firstly, our discovery cohort was solely female and both replication samples were also female dominant (Dalmatians, 68%; KORA 57%, Table 1). Secondly, given the technical differences in glycome quantification in the KORA cohort (MS compared to UPLC in Twins and Dalmatians), both GP9 and GP21 were not quantified and therefore we were unable to provide a second replication for these associations. Specifically, UPLC measures glycans from both the Fab and the Fc portion of the IgG, while MS analysis (used only on KORA samples) measures only the Fc portion. Moreover, MS analysis facilitates the differentiation of glycopeptide structures based on their m/z ratio, however it is unable to differentiate structures of the same m/z ratio but with opposed orientation of the antennae. Whereas the separation of conversely oriented antennae in glycan structures is possible with UPLC analysis since different orientation results in different retention time. Finally, hypertensive subjects were characterized only by higher systolic values, but we did not collect information on obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome.

In conclusion, our results indicate that the IgG glycoprofile of individuals who will develop incident hypertension during follow-up deteriorates in a proinflammatory, obesity-related pattern years before the actual diagnosis, supporting the role of IgG glycosylation in incident hypertension and warrants further exploration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our appreciation to all study participants of the TwinsUK cohort. Irena Trbojević Akmačić, Tea Petrović, Marija Vilaj and Anita Slana are acknowledged for their help during the laboratory work on glycan analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council AimHy (MR/M016560/1) project grant and by the Chronic Disease Research Foundation. Twins UK receives funding from the Wellcome Trust and by European Commission H2020 grants SYSCID (contract #733100); the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Facility and the Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London. Glycan analysis was supported by European Commission H2020 grants BackUP (contract #777090) and IMforFuture (contract #721815) and European Structural and Investment Funds grants “Centre of Competence in Molecular Diagnostics grant” (#KK.01.2.2.03.0006), and “Croatian National Centre of Research Excellence in Personalized Healthcare” (#KK.01.1.1.01.0010) and European Regional Development Fund grant “CardioMetabolic” agreement (#KK.01.2.1.02.0321). The KORA study was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and by the State of Bavaria. Furthermore, KORA research was supported within the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC-Health), Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, as part of LMUinnovativ and funded by the Bavarian State Ministry of Health and Care through the research project DigiMed Bayern (www.digimed-bayern.de).

CM is funded by the Chronic Disease Research Foundation and by the Medical Research Council. PL is funded by the Chronic Disease Research Foundation. SP is funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) (MR/M016560/1; AIM-HY Study) and the British Heart Foundation (BHF) (PG/12/85/29925; CS/16/1/31878) and BHF Centre of Excellence (RE/18/6/34217). MM is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded BioResource, Clinical Research Facility and Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London. AMV is funded by a UKRI and MRC Covid-Rapid Response grant (MR/V027883/1) and the Nottingham NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.

Footnotes

Author Contribution

GL, AMV and CM. conceived and designed the experiment; HD and ACi performed the experiment; DK, PL, CG, and CM analysed the data; HG, AP, OP, OG, MM, TDS, SP contributed reagents, materials and/or analysis tool. DK, ACv, PL, GL, CM wrote the original manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

GL is a founder and owner, HD and ACi are employees of Genos Ltd, which offers commercial service of glycomic analysis and has several patents in this field. TDS is co-founder and AMV is a consultant for Zoe Global Ltd. As founder and employees of companies with invested interest, GL and AMV conceived the analyses. HD and ACi performed glycan quantification. No individual with potential conflicting interests had any involvement with the analysis of the data or the direction of the manuscript text. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data availability

The data used in this study are held by the department of Twin Research at King’s College London. The data can be released to bona fide researchers using our normal procedures overseen by the Wellcome Trust and its guidelines as part of our core funding (https://twinsuk.ac.uk/resources-for-researchers/access-our-data/).

References

- 1.Kjeldsen SE. Hypertension and cardiovascular risk: General aspects. Pharmacol Res. 2018;129:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louca P, Menni C, Padmanabhan S. Genomic Determinants of Hypertension With a Focus on Metabolomics and the Gut Microbiome. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:473–481. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagae M, Yamaguchi Y. Function and 3D structure of the N-glycans on glycoproteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:8398–8429. doi: 10.3390/ijms13078398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Klarić L, Yu X, Thaqi K, Dong J, Novokmet M, et al. The Association Between Glycosylation of Immunoglobulin G and Hypertension: A Multiple Ethnic Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3379. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittenbecher C, Štambuk T, Kuxhaus O, Rudman N, Vučković F, Štambuk J, et al. Plasma N-Glycans as Emerging Biomarkers of Cardiometabolic Risk: A Prospective Investigation in the EPIC-Potsdam Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:661–668. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plomp R, Ruhaak LR, Uh HW, Reiding KR, Selman M, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, et al. Subclass-specific IgG glycosylation is associated with markers of inflammation and metabolic health. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12325. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12495-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng J, Vongpatanasin W, Sacharidou A, Kifer D, Yuhanna IS, Banerjee S, et al. Supplementation With the Sialic Acid Precursor N-Acetyl-D-Mannosamine Breaks the Link Between Obesity and Hypertension. Circulation. 2019;140:2005–2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menni C, Gudelj I, Macdonald-Dunlop E, Mangino M, Zierer J, Bešić E, et al. Glycosylation Profile of Immunoglobulin G Is Cross-Sectionally Associated With Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Two Independent Cohorts. Circ Res. 2018;122:1555–1564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdi S, Abbasian G, Bowyer RCE, Lachance G, Yarand D, Christofidou P, et al. TwinsUK: The UK Adult Twin Registry Update. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2019;22:523–529. doi: 10.1017/thg.2019.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudan I, Marusić A, Janković S, Rotim K, Boban M, Lauc G, et al. “10001 Dalmatians:” Croatia launches its national biobank. Croat Med J. 2009;50:4–6. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holle R, Happich M, Löwel H, Wichmann HE. KORA--a research platform for population based health research. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S19–25. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pucić M, Knezević A, Vidic J, Adamczyk B, Novokmet M, Polasek O, et al. High throughput isolation and glycosylation analysis of IgG-variability and heritability of the IgG glycome in three isolated human populations. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M111.010090. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waters Corporation. GlycoWorks RapiFluor-MS N-Glycan Kit – 96 Samples. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurić J, Kohrt WM, Kifer D, Gavin KM, Pezer M, Nigrovic PA, et al. Effects of estradiol on biological age measured using the glycan age index. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:19756–19765. doi: 10.18632/aging.104060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keser T, Vučković F, Barrios C, Zierer J, Wahl A, Akinkuolie AO, et al. Effects of statins on the immunoglobulin G glycome. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2017;1861:1152–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menni C, Keser T, Mangino M, Bell JT, Erte I, Akmačić I, et al. Glycosylation of Immunoglobulin G: Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Influences. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e82558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauc G, Essafi A, Huffman JE, Hayward C, Knežević A, Kattla JJ, et al. Genomics meets glycomics-the first GWAS study of human N-Glycome identifies HNF1α as a master regulator of plasma protein fucosylation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, Jaffe AE, Storey JD. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:882–883. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.GenABEL project developers. GenABEL: genome-wide SNP association analysis. CRAN; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therneau TM. Mixed Effects Cox Models. CRAN; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu D, Chu X, Wang H, Dong J, Ge SQ, Zhao ZY, et al. The changes of immunoglobulin G N-glycosylation in blood lipids and dyslipidaemia. J Transl Med. 2018;16:235. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1616-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu D, Li Q, Zhang X, Wang H, Cao W, Li D, et al. Systematic Review: Immunoglobulin G N-Glycans as Next-Generation Diagnostic Biomarkers for Common Chronic Diseases. Omics. 2019;23:607–614. doi: 10.1089/omi.2019.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novokmet M, Lukić E, Vučković F, Ðurić Ž, Keser T, Rajšl K, et al. Changes in IgG and total plasma protein glycomes in acute systemic inflammation. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4347. doi: 10.1038/srep04347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greto VL, Cvetko A, Štambuk T, Dempster NJ, Kifer D, Deriš H, et al. Extensive weight loss reduces glycan age by altering IgG N-glycosylation. International Journal of Obesity. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00816-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao Q, Dolikun M, Štambuk J, Wang H, Zhao F, Yiliham N, et al. Immunoglobulin G N-Glycans as Potential Postgenomic Biomarkers for Hypertension in the Kazakh Population. Omics. 2017;21:380–389. doi: 10.1089/omi.2017.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gudelj I, Lauc G, Pezer M. Immunoglobulin G glycosylation in aging and diseases. Cell Immunol. 2018;333:65–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakoski SG, Cushman M, Siscovick DS, Blumenthal RS, Palmas W, Burke G, et al. The relationship between inflammation, obesity and risk for hypertension in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:73–79. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan CT, Sobey CG, Lieu M, Ferens D, Kett MM, Diep H, et al. Obligatory Role for B Cells in the Development of Angiotensin II-Dependent Hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;66:1023–1033. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norlander AE, Madhur MS, Harrison DG. The immunology of hypertension. J Exp Med. 2018;215:21–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are held by the department of Twin Research at King’s College London. The data can be released to bona fide researchers using our normal procedures overseen by the Wellcome Trust and its guidelines as part of our core funding (https://twinsuk.ac.uk/resources-for-researchers/access-our-data/).