Abstract

The present study used quantitative and qualitative methods to explore how lonely young people are seen from others’ perspectives, in terms of their personality, behaviour and life circumstances. Data were drawn from the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study, a cohort of 2,232 individuals born in the United Kingdom in the mid-1990s. When participants were aged 18, they provided self-reports of loneliness, and informant ratings of loneliness were provided by interviewers, as well as participants’ parents and siblings. Interviewers further provided Big Five personality ratings, and detailed written notes in which they documented their perceptions of the participants and their reflections on the content of the interview. In the quantitative section of the paper, regression analyses were used to examine the perceptibility of loneliness, and how participants’ loneliness related to their perceived personality traits. The informant ratings of participants’ loneliness showed good agreement with self-reports. Furthermore, loneliness was associated with lower perceived conscientiousness, agreeableness and extraversion, and higher perceived neuroticism. Within-twin pair analyses indicated that these associations were partly explained by common underlying genetic influences. In the qualitative section of the study, the loneliest 5% of study participants (N=108) were selected, and thematic analysis was applied to the study’ interviewers’ notes about those participants. Three themes were identified and named: ‘uncomfortable in own skin’, ‘clustering of risk’, and ‘difficulties accessing social resources’. These results add depth to the current conceptualisation of loneliness, and emphasise the complexity and intersectional nature of the circumstances severely lonely young adults live in.

Keywords: Loneliness, social support, mental health, personality

Introduction

Loneliness is a form of psychological distress felt in response to perceived deficits in one’s social relationships (Ernst & Cacioppo, 1999). Temporary, sporadic episodes of loneliness are likely to affect many individuals at some time in their lives and, if the circumstances responsible are resolved in due course, are unlikely to impose significant impairment or long-term consequences. However, for some individuals, loneliness becomes a burden that is persistent across time and pervasive across situations. Over time, loneliness predicts deterioration in mental and physical health, and elevated risk for early mortality (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2014; Courtin & Knapp, 2017; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, 2015). Preventing individuals from becoming trapped in loneliness is therefore of key importance, and a goal of research should be to develop a detailed, context-rich profile of this phenomena, in order to understand the circumstances under which that could occur.

Recent research has drawn attention to the disproportionately high rates of self-reported loneliness in adolescence and young adulthood (Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016; Office for National Statistics, 2018). These developmental stages are periods of significant transition, in which individuals face the task of establishing their independence for the first time and adapting to changes in their social networks (Lenz, 2001). Milestones such as leaving school, moving out of the parental home, entering the labour market or tertiary education, and establishing long-term romantic relationships each represent new challenges which, if not navigated successfully, could threaten to impoverish individuals of social connection and leave them feeling marginalised and cut off from those around them.

The predominant conceptual approach to loneliness defines it in terms of a mismatch between the kinds of social relationships a person desires and those that they have in reality (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Thus, loneliness is not synonymous with solitude or isolation (Victor, Scambler, Bond & Bowling, 2000). Instead, it is a state of mind, and even individuals with similar degrees of actual social connection may differ in the extent to which they feel lonely. Moreover, individual differences in loneliness show similar stability to differences in personality traits, which has led to loneliness being described as trait-like in nature (Mund, Freuding, Möbius, Horn, & Neyer, 2019). Loneliness and personality are therefore likely to be closely interrelated, and indeed, associations have been found between loneliness and each of the Big Five personality traits, particularly neuroticism (Buecker, Maes, Denissen & Luhmann, 2020; Mund & Neyer, 2018; Vanhalst, Klimstra, Luyckx, Scholte, Engels & Goossens, 2012).

Furthermore, there is evidence that associations between loneliness and personality traits are mediated by genetic influences, indicating the importance of using study designs that allow these influences to be controlled for (Abdellaoui, Willemsen, Ehli, Davies, Verweij, Nivard, de Geus, Boomsma & Cacioppo, 2018). Twin studies offer one such solution, in the form of the discordant twin method (Pingault et al, 2018). By comparing twins within a pair, unmeasured familial sources of confounding are held constant by design, as these effects are assumed to be the same for each twin. In the case of monozygotic twins, these include all genetic effects. Therefore, any differences in a given trait between two monozygotic twins cannot be explained by genetic differences. If these differences are correlated with differences in a second trait, this indicates an association independent of genetic confounding. If, on the other hand, no such correlation is observed, despite the two traits being correlated in samples of singletons, this suggests that the association between them is explained by a common underlying genetic aetiology. This method provides a powerful means of investigating the role of genetics in associations between loneliness and personality traits. Loneliness could also have implications for how an individual’s personality and behaviour is perceived by others. Past research has shown that self-reports of loneliness are corroborated with reasonable accuracy by ratings made by informants such as parents, friends and romantic partners (Luhmann, Bohn, Holtmann, Koch & Eid, 2016), indicating that loneliness is perceptible. A similar degree of agreement is observed between ‘self’ and ‘other’ ratings of personality (Vazire & Carlson, 2010). Previous research has found that lonely individuals are viewed more negatively by others (Jones, Freemon & Goswick, 1981; Tsai & Reis, 2009). This may be partly due to stigma (Lau & Gruen, 1992), but behavioural cues in social interactions may also play a role (Nestler & Back, 2013). According to a hypothesis rooted in evolutionary theory (Cacioppo et al., 2006), loneliness is an adaptive response to the experience of social disconnection, which braces individuals to cope with a potentially unsafe environment without the protection of others. As a result, loneliness is accompanied an elevated vigilance for social threats, reduced trust towards others, and more negative expectations of social encounters (Spithoven, Bijttebier, & Goossens, 2017). While this may help to maintain distance from those with potentially hostile intent, engaging in these defensive patterns of behaviour could negatively bias how lonely individuals are perceived by others. However, the impressions formed from these interactions may leave others with an incomplete or misleading perception of lonely individuals. That loneliness is closely interrelated with personality characteristics does not preclude the possibility that there are wider contextual factors that also shape the ways in which lonely individuals interact with the world. For instance, research has shown that loneliness intersects with difficulties across many domains of young people’s lives, including mental health problems, negative physical health-related behaviours, academic and job-seeking struggles, difficulty coping with stress, and childhood peer problems (Matthews et al, 2019). This coalescence of other adversities around loneliness means that each individual case is likely to be complex and multifaceted, and appraisals of personality traits based on superficial observations of behaviour may lead to lonely individuals being misunderstood.

The use of qualitative methods, alongside the more statistical approaches commonly used in research on loneliness, is one way in which the complexities of this phenotype can be explored in novel ways. A number of qualitative studies have previously been conducted on loneliness in young people. These have typically focused on specific aspects of people’s lived experiences of loneliness, such as the perceived causes of loneliness and strategies for coping with it (Korkiamäki, 2014; Office for National Statistics, 2018; Vasileiou et al., 2019). Another way in which qualitative analysis can be used to explore the nature of loneliness is to examine the accounts of individuals who have just spent time interacting with a lonely individual, and investigate whether the narratives that emerge from those accounts converge on certain themes. Such an approach could yield not only more nuanced descriptions of lonely individuals’ outward personality characteristics, but also more general observations that add context and meaning to these appraisals.

In the present study, we utilise quantitative and qualitative approaches to investigate how lonely young people are perceived by others, using data collected via home visits in a cohort study of young people. Here, the majority of the data are not provided directly by participants themselves, but instead are drawn from other people’s perceptions based on their interactions with the participants. In the quantitative part of the study, a multi-informant approach is used to measure the perceptibility of loneliness to others (interviewers, siblings and parents). Moreover, interviewer’s ratings of participants’ Big Five personality traits are used to examine the association between loneliness and perceived personality, and twin data are used to test for genetic confounding of these associations. In the qualitative part of the study, interviewers’ written notes about the participants are explored and analysed for recurring themes. In this approach, the interviewers are used as intermediaries on whom the participants’ characteristics and circumstances are impressed, and subsequently recorded and interpreted. This allows loneliness – typically conceptualised as a private and intimate phenomenon – to be examined ‘from the outside’, yielding novel insights that solely quantitative or self-reported data may not capture.

Method

Participants

Participants were members of the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, which tracks the development of a birth cohort of 2,232 British children. The sample was drawn from a larger birth register of twins born in England and Wales in 1994–1995 (Trouton, Spinath & Plomin, 2002). Full details about the sample are reported elsewhere (Moffitt and E-Risk Study Team, 2002). Briefly, the E-Risk sample was constructed in 1999–2000, when 1,116 families (93% of those eligible) with same-sex 5-year-old twins participated in home-visit assessments. This sample comprised 56% monozygotic (MZ) and 44% dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs; sex was evenly distributed within zygosity (49% male). 90% of participants were of white ethnicity.

Families were recruited to represent the UK population with newborns in the 1990s, to ensure adequate numbers of children in disadvantaged homes and to avoid an excess of twins born to well-educated women using assisted reproduction. The study sample represents the full range of socioeconomic conditions in Great Britain, as reflected in the families’ distribution on a neighbourhood-level socioeconomic index (ACORN [A Classification of Residential Neighbourhoods], developed by CACI Inc. for commercial use) (Odgers, Caspi, Bates, Sampson & Moffitt, 2012; Odgers, Caspi, Russell, Sampson, Arseneault & Moffitt, 2012). Specifically, E-Risk families’ ACORN distribution matches that of households nation-wide: 25.6% of E-Risk families live in “wealthy achiever” neighbourhoods compared to 25.3% nationwide; 5.3% vs. 11.6% live in “urban prosperity” neighbourhoods; 29.6% vs. 26.9% live in “comfortably off” neighbourhoods; 13.4% vs. 13.9% live in “moderate means” neighbourhoods, and 26.1% vs. 20.7% live in “hard-pressed” neighbourhoods. E-Risk underrepresents “urban prosperity” neighbourhoods because such houses are likely to be childless.

Follow-up home visits were conducted when the children were aged 7 (98% participation), 10 (96%), 12 (96%), and 18 years (93%). There were 2,066 children who participated in the E-Risk assessments at age 18. The average age of the twins at the time of the assessment was 18.4 years (SD = 0.36); all interviews were conducted after their 18th birthday. There were no differences between those who did and did not take part at age 18 in terms of socioeconomic status (SES) assessed when the cohort was initially defined (χ2(2, N = 2,232) = 0.86, p = .65), age-5 IQ scores (t(2,208) = 0.98, p = .33), or age-5 emotional or behavioural problems (t(2,230) = 0.40, p = .69 and t(2,230) = 0.41, p = .68, respectively). Home visits at ages 5, 7, 10, and 12 years included assessments with participants as well as their mother (or primary caretaker). The home visit at age 18 included interviews only with the participants. The Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry Research Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study. Parents gave informed consent and twins gave assent between 5–12 years and then informed consent at age 18.

Interviewers

Study interviewers were psychology graduates or nurses. At the age-18 assessment, a total of 14 interviewers were recruited across two years of data collection. Prior to data collection, interviewers undertook intensive training over four weeks, in which they were instructed on interview technique, administering measures, making observations, and ethical issues. Interviewers were only sent into the field after they had received accreditation from the project leads.

Measures

Self-reported loneliness

Self-reported loneliness was assessed when participants were 18 years of age using four items from the UCLA Loneliness Scale, Version 3 (Russell, 1996): “How often do you feel that you lack companionship?”, “How often do you feel left out?”, “How often do you feel isolated from others?” and “How often do you feel alone?” A very similar short form of the UCLA scale has previously been developed for use in large-scale surveys, and correlates strongly with the full 20-item version (Hughes, Waite, Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2004). The scale was administered as part of a computer-based self-complete questionnaire. Interviewers were blind to participants’ responses. The items were rated “hardly ever” (0), “some of the time” (1) or “often” (2). Items were summed to produce a total loneliness score (Table 1).

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics of variables

| N | Range | M | SD | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | |||||

| Self-report | 2,051 | 0–8 | 1.57 | 1.94 | .83 |

| Interviewer report | 2,053 | 0–6 | .68 | 1.19 | .70 |

| Sibling report | 2,000 | 0–6 | .54 | 1.08 | .72 |

| Parent report | 1,682 | 0–6 | .54 | 1.06 | .73 |

|

| |||||

| Interviewer-rated personality | |||||

| Openness to experience | 2,061 | 0–10 | 5.60 | 2.45 | .67 |

| Conscientiousness | 2,064 | 0–12 | 8.26 | 2.86 | .79 |

| Extraversion | 2,065 | 0–12 | 7.83 | 3.15 | .82 |

| Agreeableness | 2,063 | 0–10 | 8.60 | 1.67 | .66 |

| Neuroticism | 2,065 | 0–10 | 1.73 | 1.72 | .55 |

Note. N = Number, M = Mean, SD = Standard deviation, α = Cronbach’s alpha

Informant-rated loneliness

The ‘interviewer impressions’ section of the assessment materials was completed by study interviewers after the age-18 home visit had ended. The purpose of this section was to capture their own perceptions of the participants’ personality, behaviour and overall functioning. Interviewers were trained to administer the interview and record participants’ responses in an accepting and non-judgemental manner, but afterwards to record their impressions as a proxy for how the participants might be perceived by a prospective employer, healthcare professional or educator. Interviewers were instructed to complete this section immediately after the visit, while it was still fresh in their memories. Three items in this section were selected to derive interviewer ratings of loneliness: “seems lonely”, “feels that no one cares for them” and “has trouble making friends”. Items were coded “No” (0), “A little/somewhat” (1) and “Yes” (2)

The same three items were also included in an ‘informant questionnaire’, completed by two individuals nominated by the participant who knew them well. Questionnaires were completed by 98.0% of the first nominated informants, of whom 99.8% were the participant’s co-twin or other sibling. Questionnaires were completed by 83.5% of the second nominated informants, of whom 98.1% were the participant’s parent.

For each informant (interviewer, sibling and parent), responses to the three loneliness items were summed to create informant-rated loneliness scales (Table 1). Rather than combining the informant ratings, the scales were analysed separately in order to compare the degree of correspondence between self-reported loneliness and ratings made by individuals with different degrees of familiarity with the participants.

Perceived personality

Included in the interviewer impressions was an adapted form of the Big Five personality inventory (John & Strivastava, 1999). This began, “Based on your interaction with the twin do you think he/she is…” followed by a list of 27 traits (e.g. “Gregarious”, “Touchy”, “Curious”). Items were coded “No” (0), “A little/somewhat” (1) or “Yes” (2). The items were summed to create personality scales of openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism (Table 1).

Qualitative data

Lined sections for text notes were interspersed with the questions in the interviewer impressions section. During training, interviewers were advised to write as many notes as possible, and to allocate ample time for this in order to record valid and reliable data. Notes were subsequently transcribed to electronic format using a bespoke data entry application.

Data analysis

Quantitative analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out in Stata 15 (StataCorp, 2017). First, to examine the perceptibility of loneliness, correlations were calculated between self-reported loneliness and the three informant-rated loneliness scales. Second, to examine associations between loneliness and perceived personality traits, each of the interviewer ratings of the Big Five traits were regressed on the self-reported loneliness scale. Regression analyses were adjusted for sex and socioeconomic status. Due to the non-independence of observations in twin data, the Huber-White estimator was used to obtain robust standard errors (Williams, 2000).

Third, to test for genetic confounding, we calculated within-twin pair difference scores for each family in the sample, by subtracting Twin 2’s score from Twin 1’s score on each of the key variables (i.e. loneliness and each of the perceived personality traits). A significant association between twin differences in loneliness and twin differences in (for example) neuroticism would indicate that the association between these two traits cannot be explained by the shared environment (i.e. environmental influences that make twins similar to each other). This is because twins who grow up in the same home environment are assumed to be matched for these influences. By further restricting the analyses to monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs, who are also matched for their genomes, genetic influences are held constant at well. Therefore, if the twin difference scores remain significantly associated with each other among MZ twins, the association between the two traits cannot be entirely explained by genetic differences.

Qualitative analyses

The qualitative analyses were carried out using the text notes from the age-18 assessment. First, the loneliest 5% of participants were identified (N = 108). This cutoff was chosen as it provides an overall percentage that is similar to the proportion of individuals who answered “often” to each of the items in the loneliness scale; hence it was expected to capture the more severe or frequent cases of loneliness. Indeed, this subset comprised individuals scoring above 5 on the total scale, and to obtain such a score, a participant would have to answer “often” to at least 2 of the 4 questionnaire items.

The mean loneliness score in this group was 6.81, versus 1.28 in the remaining 95% of the sample. Demographically, however, this subset was comparable to the rest of the sample: both groups were 47% male, low socioeconomic status was similarly represented in both groups (35% in the subset versus 33% in the rest of the sample), and the mean IQ was 100 in both groups.

The interviewer notes relating to these 108 participants were then extracted. The length of the notes varied depending on the amount of salient information that arose during the interview; cases with complicated life histories tended to have longer notes. Word counts ranged from 84 to 2008 (M = 697; SD = 384). For 68% of participants, the notes were at least 500 words in length; for 92% the notes were at least 200 words in length. Thematic analysis was carried out on the notes, based on the procedure described by Braun and Clarke (2006). First, the notes were read multiple times to build familiarity. Second, a set of codes were created to flag recurring patterns in the data. Third, the codes were examined and consolidated into a set of broader themes. Fourth, the themes were reviewed in relation to the original data and refined to reach a final thematic structure. Fifth, the meaning of the themes was explored and suitable names for them were selected. Sixth, descriptions of the themes were written up with quoted excerpts drawn from the original data to support them. To strengthen the reliability of the analysis, the initial coding and identification of themes was repeated by two other raters who were blind to the initial analysis, and the selection of the final themes was agreed by consensus. Further details are provided in the supplementary materials.

Results

Perceptibility of loneliness

The correlation between self-reported and interviewer-rated loneliness in this cohort was r = .46, indicating that participants’ loneliness was visible to a stranger. Moreover, both sibling and parent ratings of participant’s loneliness had correlations of r = .34 with self-reported loneliness. The pairwise agreement between the three informants was of a similar magnitude (r’s = 0.31 – 0.43; Table 2). This is comparable to the level of agreement found between different informants for emotional and behaviours problems (Achenbach, McConaughy & Howell, 1987).

Table 2:

Correlations between self- and informant-rated loneliness.

| Self | Interviewer | Sibling | Parent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | 1 | |||

| Interviewer | .46 | 1 | ||

| Sibling | .34 | .31 | 1 | |

| Parent | .34 | .32 | .43 | 1 |

Note. All correlations are significant at p < .001. Listwise N = 1,632.

Associations between loneliness and perceived personality

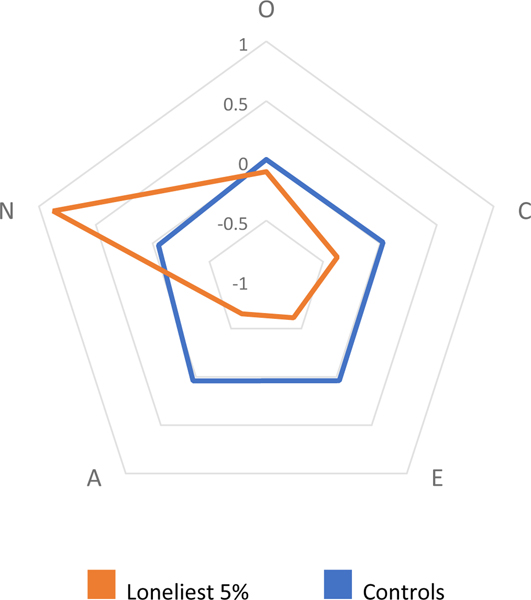

Loneliness was significantly associated with lower perceived conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness, and higher neuroticism, as rated by interviewers. However, it was not significantly associated with openness to experience (Table 3; Figure 1). In the whole sample, within-twin pair differences in loneliness were significantly associated with differences in conscientiousness, extraversion and neuroticism, but not with differences in agreeableness (Table 4). When the analyses were restricted to MZ twins only, the associations for conscientiousness became non-significant, while significant associations remained for extraversion and neuroticism. The attenuation of the coefficients, particularly for neuroticism, indicates that a substantial part (though not all) of the associations between loneliness and these traits is explained by shared genetic effects.

Table 3:

Bivariate associations between perceived personality traits and self-reported loneliness at age 18

| Personality traits: | Association with loneliness: | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| B | 95% CI | p | |

| Openness to experience | −.02 | −.05, .02 | .43 |

| Conscientiousness | −.09 | −.13, −.06 | < .001 |

| Extraversion | −.12 | −.14, −.09 | < .001 |

| Agreeableness | −.20 | −.26, −.14 | < .001 |

| Neuroticism | .31 | .25, .36 | < .001 |

Note. B = Unstandardised regression coefficient. CI = confidence interval. N = 2,044. All analyses are adjusted for sex, socioeconomic status and non-independence of twin observations.

Figure 1.

Radar chart of perceived Big Five personality scores in the loneliest 5% of participants (N = 108) versus ‘controls’ (the remaining 95% of participants; N = 1,936). The corners of the polygonal shapes indicate the mean scores in the two groups for each of the fives scales. The scales have been z-scored, such that the midpoint of the axes (0) reflects the overall sample means for each trait, and the axis ranges from 1 standard deviation below the mean to 1 standard deviation above. Scores nearer the centre of the figure are lower than the mean; scores further to the edges are higher. O = Openness to experience. C = Conscientiousness. E = Extraversion. A = Agreeableness. N = Neuroticism.

Table 4:

Associations between twin differences in perceived personality traits and twin differences in loneliness

| Personality traits: | Association with loneliness: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Whole sample (MZ and DZ twin pairs) | MZ twin pairs only | |||||

|

| ||||||

| B | 95% CI | P | B | 95% CI | p | |

| Openness to experience | −.01 | −.06, .04 | .84 | .01 | −.06, .07 | .80 |

| Conscientiousness | −.06 | −.10, −.01 | .01 | −.02 | −.08, .03 | .39 |

| Extraversion | −.08 | −.12, −.05 | < .001 | −.06 | −.11, .00 | .03 |

| Agreeableness | −.07 | −.14, .01 | .07 | −.01 | −.10, .08 | .86 |

| Neuroticism | .18 | .12, .24 | < .001 | .09 | .00, .17 | .04 |

Note. B = Unstandardised regression coefficient. CI = confidence interval. Whole sample N = 1,002 twin pairs; MZ subset N = 567 twin pairs.

Qualitative analyses

Thematic analysis of the interviewers’ text notes of the 108 loneliest individuals yielded three predominant themes. These were named uncomfortable in own skin, clustering of risk, and difficulties accessing social resources.

Uncomfortable in own skin

Interviewers’ appraisals of the loneliest participants were favourable more often than not. The most common adjectives used to describe participants were “nice”, “friendly” and “bright”. Negative descriptions, such as “rude”, “unfriendly” and “jealous” were rare. However, the quantitative personality ratings made by the interviewers were reflected in their written accounts, in which participants were frequently described as having a nervous or sensitive demeanour.

“Nervy disposition – was pacing the floor a couple of times during the interview. […] Quite sensitive and even minor slights really affect him it seems.”

[Participant 36; Male]

“I could imagine that she gets upset very easily. At times in the interview I was expecting her to burst into tears.”

[Participant 82; Female]

Interviewers observed signs of low self-worth in many cases. They noted that participants tended to use self-deprecating language; for example, making negative comments about their abilities, or apologising for things that were not their fault. Participants would also often compare themselves unfavourably to others, particularly their twin brothers or sisters.

“[Participant] was polite throughout but continually put herself down and displayed very low self-esteem.”

[Participant 68; Female]

“I think he thinks about things too much [and] is too hard on himself. Even when he answered one of my questions wrong […] he would be really apologetic or say something negative about himself.”

[Participant 27; Male]

Interviewers noted that participants exhibited signs of low confidence and shyness, which at times made it difficult to establish a rapport. Difficulties maintaining eye contact and initiating or reciprocating conversation were often observed, as well as physical mannerisms that suggested nervousness and self-consciousness.

“Seemed to try and make herself look smaller by dipping her head and pulling her arms close. […] She did not seem very confident and seemed quite introverted.”

[Participant 3; Female]

“Found him awkward during the interview – like he didn’t know how to interact with strangers, and it was left to Dad to do a lot of the chit chat. I think he didn’t really like having so much attention focused on him as well.”

[Participant 20; Male]

“Seems very nervous and uncomfortable in her own skin. Found it hard to make eye contact and seemed uncomfortable under my gaze; picking at nails, hair and shuffling about during the interview.”

[Participant 2; Female]

Often, participants would gradually become more comfortable and talkative as the interview progressed. However, in the more extreme cases, such was the difficulty of advancing conversation that the interviewers themselves felt uncomfortable in the situation.

“I found it quite hard to get conversation flowing with [participant], she gave very short answers to questions and didn’t really attempt to make conversation. [...] There were some long awkward silences when I couldn’t think of anything else to say!”

[Participant 12; Female]

As each participant was being interviewed by a stranger about highly sensitive subject matter, it is possible that the situation partly contributed to their reticence. However, signs of low confidence in other contexts were also noted. For example, among some participants interviewers noted a tendency to stay close to home, suggesting a more general reluctance to leave their comfort zone.

“It seems she has not ventured far and did not feel confident to ride the London transport or navigate areas alone.”

[Participant 21; Female]

Notably, not all participants were described as quiet or reserved. To the contrary, some were described as chatty, outgoing and confident. In certain cases, however, their talkativeness was excessive and tended towards the socially inappropriate. Interviewers interpreted this either as a further sign of nervousness or a difficulty reading social cues. In such instances, some interviewers speculated that the participant might not make a good impression in a job interview or an unfamiliar social situation.

“[Participant] was really talkative but not in terms of showing interest or general chat, he would just ask question after question and it almost felt like an interrogation at first.”

[Participant 49; Male]

“Would go off on rants and tangents and as such the interview took over five hours to complete.”

[Participant 72; Male]

Clustering of risk

The majority of participants were described as having experienced significant adversities such as mental health problems and victimisation, and in the majority of these cases, multiple different forms of adversity were present. Many of the interviewers’ accounts described complex and eventful life histories. For instance, one of the most severe cases involved a catalogue of physical and sexual abuse during childhood, parental substance problems, family conflict, homelessness, self-harm, and suicide attempts.

“I really liked the twin and felt sorry for her and what she had been through, I still felt that she had many issues to deal with and perhaps needed more in-depth help as had only had 6 sessions, which although she said had helped and helped her to be able to talk about it, she still seemed to have many issues.”

[Participant 25; Female]

Mental health problems were mentioned in more than half of cases. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were the most common, followed by self-harm and substance abuse. These mental health symptoms were often described in the context of other difficulties, such as being unemployed, or a history of adverse experiences in childhood.

“[Participant] presented with symptoms of depression, GAD and PTSD. His difficulties appeared inherently connected to the experiences of domestic violence he has been through in his childhood. He is unhappy with his life at the moment and being unemployed.”

[Participant 42; Male]

Almost half of participants were described as having been subjected to some form of victimisation. The most common of these was bullying, followed by physical and sexual victimisation by an adult. A smaller number of participants had experienced emotional abuse, neglect, or an abusive relationship. In some cases, interviewers believed that the participant’s low confidence was directly attributable to their experiences of bullying at school.

“I noted that [participant] seemed to have trouble maintaining eye contact. She was very intelligent but I felt that she had low self-esteem. Maybe the bullying had more of an impact on her than she thought.”

[Participant 6; Female]

“The bullying [participant] experienced was intense and occurred more or less every day throughout the whole of her education. As a result of the bullying [participant] left school without receiving any qualifications which she is very conscious of and makes her unconfident during interviews.”

[Participant 30; Female]

Approximately half of the accounts referred to strained relationships within the family. These tended to involve conflict or tension between the participant and a parent or sibling. Some family members had substance problems or other mental health disorders that contributed to the conflict between them. Parental separation was also mentioned frequently, although none of the interviewers’ accounts suggested that this had directly contributed to the participants’ difficulties; instead it appeared to be a concomitant indicator of family discord more generally.

“Twin has a difficult relationship with her mother. Twin has said that her relationship has improved a lot since moving out to live with her father when 15 years old. However you can see that the relationship is still strained.”

[Participant 71; Female]

“[Participant] said he hates living at home because he hates the atmosphere in the house and hates his older sister who lives there.”

[Participant 87; Male]

Lack of money featured in some cases. Difficulty finding and maintaining a job was a problem, particularly for those who were experiencing multiple difficulties at home. In some cases, participants were expected to support their own parents financially, while others had moved into their own home but had little money to subsist on. This was not only a source of stress in its own right, but also distracted participants from dealing with other stressors in their lives.

“They are renting a 1 bed flat and barely have anything in it. No washing machine, no bed, just mattress, one tiny single sofa. [Participant] said they can’t afford to put the heating on as it costs too much on the gas card, house was freezing cold.”

[Participant 2; Female]

There were mixed descriptions of participants’ general life outlook and prospects about the future. Individuals who had been proactive about seeking help for mental health problems, and who had support from family, appeared to be more positive in their outlook and confident that their situations would improve in the future. Those with more passive approaches to their circumstances, by contrast, were described as seeming lost or pessimistic.

“In general I think that she was a nice well rounded young woman, I think that her recent mental health problems seem to be under control and she has good support from friends and family to help her through it. She seemed positive for the future, and doesn’t want to dwell on what has happened and she is keen to make sure she stays well so has cut down on alcohol and is happy to still be seeing a counsellor.”

[Participant 29; Female]

“He seemed very dissatisfied with his life, but didn’t seem have any desire to make any changes […] He said that if he could live his life over again, he would change everything about it, although couldn’t get out of him what exactly he would change or do differently.”

[Participant 60; Male]

Difficulties accessing social resources

Unsurprisingly, having few or no friends featured in numerous cases. However, in many accounts it appeared that what was lacking was not social connections per se, but rather the more functional aspects of those relationships. For example, some participants were fairly socially active, but when asked about sources of social support during the interview, it became clear that their friendships were largely superficial in nature, characterised by shared activities rather than companionship and confiding.

“I got the impression that she is a sociable girl, e.g. she goes out with her friends most weekends, however based on her answers during Social Support I don’t think she confides in her friends very much.”

[Participant 70; Female]

“He views his friends as his real family. However, it seemed like they are all a group of friends he has only because they all take drugs together […] he was quite negative about them in the Social Support section.”

[Participant 52; Male]

Life transitions played a role in disrupting access to social support. Some participants had moved home frequently, sometimes to different countries, which brought instability and pressure to adjust to new environments. Others had experienced difficulty leaving the education system, or moving to a new educational setting. This led to them being unable to see friends that previously they had seen daily, or losing the support of a teacher who had helped them to navigate their problems.

“Mentioned several times that she does not have any/many friends as she lost contact with them when she left college.”

[Participant 22; Female]

“The twin was quite close to his psychology teacher at school and the twin sought him out to talk about things. However now the twin has left school he feels he has no one to talk to.”

[Participant 69; Male]

While it was clear to some interviewers that the participant they had spoken to was isolated or lacked support, others observed that the participant seemed to feel that they had less support than may actually have been the case, particularly from family members.

“[Participant] perceives that he has no family support, and although in some regard he is right, he does seem to have more help than perhaps he realises. […] As the interview went on, he did seem to concede more and more that his family are there when he needs them to be.”

[Participant 52; Male]

“I was surprised that he didn’t report more support from his family as they seemed very close and family oriented with lots of relatives living nearby.”

[Participant 5; Male]

“[Participant] said that she didn’t have any friends at all and I do think that she has difficulty forming friendships […] yet she kept telling me stories of friends.”

[Participant 43; Female]

“I think he has people there for support but he doesn’t feel that his family do enough for him. I think they are there if he wants them to be but he has pushed them away by moving out and now doesn’t really know what to do.”

[Participant 107; Male]

Similarly, interviewers noted that some participants were aware that they had access to social support, but chose to cope with their problems alone rather than draw on that support.

“[Participant] feels she does have support from her friends and family but she chooses to deal with things alone.”

[Participant 18; Female]

“Reported that sometimes relationship with family is not that great. Although thinks this is more to do with him keeping things to himself than lack of support.”

[Participant 66; Male]

This tendency to avoid seeking help from friends and family applied also to mental health services. Some participants actively resisted the idea of seeking help, on the basis that their mental health problems were an integral part of their being and that seeking to treat them was futile. Others had received some form of help but had not fully engaged with it.

“She said she would never look for any help for her anxiety because she thinks that is just who she is and no-one would be able to change it.”

[Participant 88; Female]

“She told me that she stopped taking her depression medication in September because she didn’t think that she needed it anymore but she was signed off work due to depression in October so she was obviously not feeling better at the time but she didn’t tell her doctor that she had stopped the medication.”

[Participant 13; Female]

At times, interviewers believed the participant was reluctant to disclose the full extent of the difficulties they experienced. For example, the participant might have seemed upbeat and self-assured at the start of the interview, but became distressed, irritated or closed-off when asked about past events.

“[Participant] seems guarded and I don’t feel he completely opened up. He refused to answer the Self-Harm section as I am pretty sure he has self-harmed – but didn’t want to discuss it with me.”

[Participant 61; Male]

Low trust appeared to be an important barrier to seeking help or support. It was often reported that the participant had difficulty trusting people and, in some cases, did not trust anyone. Often, this low trust was attributed to past experiences of victimisation, betrayal or exploitation. In some cases, this difficulty trusting people was considered to be a contributing factor to the participants’ loneliness.

“[Participant] has experienced several violence events. […] As a result of these events people who she thought were good friends turned against her which appears to have left her with trust issues (saying she feels as though she can’t trust anyone in the Unusual Thoughts section, and being quite suspicious of me initially).”

[Participant 96; Female]

“Has friends but doesn’t trust them and doesn’t report feeling close to them. Only answered ‘somewhat true’ to Social Support questions about friends […] I think she is a bit lonely and isolated because of not trusting anyone and not having anyone to confide in.”

[Participant 12; Female]

Discussion

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to document the outward presentation of loneliness, through the eyes of others. It replicates the finding that a person’s loneliness is perceptible to others who know them well (Luhmann, Bohn, Holtmann, Koch & Eid, 2016). Furthermore, as reported previously (Matthews, Danese, Gregory, Caspi, Moffitt & Arseneault, 2017), the interviewer ratings indicate that participants’ loneliness is visible even to someone who has met them for the first time. The study further extends prior research by investigating the other ways in which lonely individuals are perceived by others. The interviewers observed patterns of personality characteristics, mannerisms and life circumstances in the loneliest participants that illustrate the complexity of this phenotype and the wider context in which it is embedded. A distinct profile of perceived personality traits in lonely individuals was observed. Neuroticism was particularly salient: of the five traits, it was the strongest correlate of loneliness. Meanwhile, openness to experience was the only trait not associated with loneliness. Both findings are consistent with other recent studies (Buecker et al, 2020; Mund & Neyer, 2016; 2018). The present study adds to the existing literature by applying genetically-sensitive methods to these associations. Previous research using polygenic scores has shown a genetic correlation between loneliness and personality traits such as neuroticism (Abdellaoui et al., 2019). Using a twin-differences approach to control for all genetic effects, the present study provides further support for this, showing that the associations between loneliness and perceived personality traits are to a large extent explained by common genetic aetiology. This attests to the notion of loneliness as a trait-like phenomena that has much in common with personality traits (Mund & Neyer, 2018).

The qualitative analyses add further meaning to these findings, offering a rich insight into the lives of individuals suffering from loneliness, through the unique perspective of an outside observer who has been given a privileged view into their mental health, living circumstances and childhood histories. Previous qualitative research has typically involved participants discussing their own lived experiences of loneliness (Korkiamäki , 2014; Office for National Statistics, 2018; Vasileiou, Barreto, Atkinson, Lond, Bakewell, Lawson & Wilson, 2019). In the present study, our aim was to use the interviewers as mediators of information, and to assimilate that information in a holistic, bigger-picture analysis in which loneliness is set within a wider context. The strength of this approach can be seen in the ability of the interviewers to ‘read between the lines’ and make observations that might not have emerged from a first-person account. The narrative that arose from the interviewers’ accounts was one of highly vulnerable individuals who have experienced disrupted and at times chaotic lives. The data also reveal how individuals can become trapped in loneliness, through a combination of unfavourable circumstances and maladaptive perceptions that put potential sources of support out of reach.

The first theme, uncomfortable in own skin, shows lonely participants struggling to feel at ease in dyadic interactions with people they have met for the first time. Shyness, awkwardness, low confidence and negative self-perceptions made it difficult for conversation to flow freely. Whether these traits were an acquired consequence of loneliness, or a contributing factor, was not clear. On the one hand, experiencing minimal social contact for a prolonged time could both beget feelings of loneliness and also deprive individuals of the opportunity to practice social skills, receive positive feedback and build confidence in social situations. On the other hand, inhibited behaviour in social encounters could prevent individuals from building rapport and experiencing a meaningful connection with others – indeed, in some cases, participants’ own discomfort appeared to spread to the interviewers, leaving both parties feeling mutually unable to engage with each other. One predominant model suggests that feelings of loneliness influence behaviour in social situations, and the behaviour of the social partner, in a cyclical manner (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). According to this model, loneliness gives rise to negative expectations about social encounters and about the intentions of others, in turn leading to guarded behaviours and difficult social interactions that inadvertently reinforce these beliefs, creating further disconnect between lonely individuals and those around them. In this manner, loneliness could become a vicious cycle that perpetuates itself over a period of months or years.

The second theme, clustering of risk, highlights that loneliness does not occur in a vacuum, but is often part of a constellation of intersecting adversities including mental illness, victimisation and family conflict. This aggregation of hardships within individual cases Is supported by quantitative data in the same cohort, showing that loneliness in young adults is pervasively associated with psychopathology, poor stress coping, health risk behaviours and job-seeking difficulties (Matthews et al., 2019). The qualitative analyses further highlight the complex interrelationship between different factors in the context of loneliness (for example, between victimisation and low trust, and between unemployment and depression). The role of bullying was particularly salient, and merits further investigation: being a victim of bullying could be a risk factor for loneliness in its own right, but lonely individuals could also be perceived as easy targets (Pavri, 2015). However, other forms of victimisation were also described in the data, and future research should consider how associations between victimisation and loneliness vary across different types of exposure, context and perpetrator.

While the second theme highlights lonely individuals’ need for support, the third, difficulties accessing social resources, reveals barriers to obtaining or utilising that support. Objective lack of social connection was a problem in some cases, but in others the issue appeared to concern the way participants felt about their relationships with those around them. Loneliness is defined as a mismatch between one’s desired and actual social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982), and in view of this, it is unsurprising that the loneliest participants in this sample tended to perceive that they lacked social support. However, in some cases the interviewer’s observation was that these perceptions were at odds with the empirical reality of their circumstances, underscoring the subjective nature of loneliness and its association with negatively-biased cognitions. Even where participants acknowledged that they had access to support, there was often a reluctance or lack of agency to avail themselves of that support: low trust, perceived hopelessness and a preference for coping privately led to participants suffering in silence, compounding their isolation.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that the personality ratings were made by study interviewers, thereby avoiding bias that could be introduced by relying entirely on self-reports. On the other hand, as interviewers were the sole informants for the personality rating, it was not possible to test agreement with self-reports or ratings made by other informants. Nonetheless, there is evidence that informant ratings of personality traits show good agreement with self-reports, and measure the same underlying constructs (Olino & Klein, 2015). Another issue that bears consideration is that the agreement between self-reported loneliness and the three informant ratings was highest for the interviewer report. While the interviewers were blind to participants’ responses to the loneliness questionnaire, they had just conducted an in-depth interview with the participant about their mental health, experiences and circumstances. This privileged knowledge may have placed the interviewers’ in a better position to make informed judgements about participants’ loneliness. Alternatively, behavioural cues that signalled participants’ loneliness may have been more unambiguous in the highly focused interview situation. Parents and siblings, meanwhile, may have drawn on more global information about the participants, including situations in which those cues were less visible.

The qualitative analyses were restricted to the 5% of participants at the extreme tail of the loneliness distribution. This is similar to the proportion of young people who report that they feel lonely often (Matthews et al., 2019; Office for National Statistics, 2018). However, the accounts presented here may reflect exceptionally troubled circumstances that are not generalisable to young people with more middling levels of loneliness. Furthermore, despite the recurring themes that were observed in the data, no two individuals’ circumstances were identical, and these themes reflect patterns within the lonely population rather than a single exemplary profile of the lonely individual. Interviewers were not instructed to take notes according to a formal protocol, nor were they instructed to make notes specifically commenting on participants’ loneliness. Instead, their objective was to document, in a free-form manner and in as much detail as possible, what they considered to be the most salient details of the interview. This open-ended approach could be a strength, as it allowed the interviewers to focus on the most relevant aspects of each individual case, and to draw connections that might have been missed by adhering to a more structured framework.

Nonetheless, while all interviewers received the same training, some inter-rater differences in note-taking style is to be expected.

Implications

The insights from the interviewers’ accounts suggest potential avenues of intervention to reduce loneliness. Many different forms of intervention currently exist, but the evidence base is limited (Gardiner, Geldenhuys & Gott, 2018). Meta-analyses indicate that there is some support for therapeutic approaches geared towards addressing maladaptive social cognitions (Eccles & Qualter, 2020; Masi, Chen, Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2011). The findings of the current study could be informative for such interventions: first, they highlight the need to help lonely youths access and make best use of social resources, and foster a proactive and optimistic outlook. Second, because loneliness often co-occurs with other problems such as psychopathology and trauma, efforts to target feelings of loneliness should also take this wider context into account. However, the findings also suggest some barriers to the delivery of interventions: if lonely individuals are often reluctant to seek help, interventions may fail to reach some of the people most in need of them. Reducing stigma attached to loneliness and encouraging help-seeking behaviours is therefore an important objective also. Finally, the findings of this study show that lonely individuals live in a diverse range of situations, and there is unlikely to be a ‘one-size-fits all’ approach (Mann et al., 2017). Instead, it is important to consider the role of individual differences in personality, and the unique circumstances in which each lonely individual is situated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The E-Risk Study is funded by the Medical Research Council (UKMRC grant G1002190). Additional support was provided by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant HD077482) and by the Jacobs Foundation. Timothy Matthews is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow. Louise Arseneault is the Mental Health Leadership Fellow for the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). Helen L. Fisher received salary support from the ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health at King’s College London [ES/S012567/1]. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the ESRC or King’s College London. The authors are grateful to the Study members and their families for their participation. Our thanks to CACI, Inc., and to members of the E-Risk team for their dedication, hard work, and insights.

References

- Abdellaoui A, Chen HY, Willemsen G, Ehli EA, Davies GE, Verweij KJ, Nivard MG, de Geus EJ, Boomsma DI, & Cacioppo JT (2019). Associations between loneliness and personality are mostly driven by a genetic association with neuroticism. Journal of Personality, 87, 386–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, & Howell CT (1987) Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buecker S. Maes M, Denissen JJA, & Luhmann M. (2020). Loneliness and the Big Five personality traits: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Personality, 34, 8–28. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, & Cacioppo S. (2014). Social relationships and health: The toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 58–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, Burleson M, Berntson GG, Nouriani B, & Spiegel D. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 1054–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Courtin E, & Knapp M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25, 799–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles AM, & Qualter P. (2020). Review: alleviating loneliness in young people – a meta-analysis of interventions. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. doi: 10.1111/camh.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst JM, & Cacioppo JT (1999). Lonely hearts: psychological perspectives on loneliness. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, & Gott M. (2018). Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, & Stephenson D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26, 655–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, & Strivastava S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Pervin LA, & John OP (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp 102–138). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones WH, Freemon JE, & Goswick RA (1981). The persistence of loneliness: Self and other determinants. Journal of Personality, 49, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Korkiamäki R. (2014). Rethinking loneliness—a qualitative study about adolescents’ experiences of being an outsider in peer group. Open Journal of Depression, 3, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. (1992). Children’s depression inventory: Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Lau S, & Gruen GE (1992). The social stigma of loneliness: Effect of target person’s and perceivers sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz B. (2001). The transition from adolescence to young adulthood: a theoretical perspective. Journal of School Nursing, 17, 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann M, & Hawkley LC (2016). Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Developmental Psychology, 52(6), 943–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann M, Bohn J, Holtmann J, Koch T, & Eid M. (2016). I’m lonely, can’t you tell? Convergent validity of self-and informant ratings of loneliness. Journal of Research in Personality, 61, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B, Frerichs J, Pinfold V, Ma R, Wang J, & Johnson S. (2017). A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52, 627–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 219–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews T, Danese A, Caspi A, Fisher HL, Goldman-Mellor S, Kepa A, Moffitt TE, Odgers CL, & Arseneault L. (2019). Lonely young adults in modern Britain: findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychological medicine, 49, 268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews T, Danese A, Gregory AM, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, & Arseneault L. (2017). Sleeping with one eye open: Loneliness and sleep quality in young adults. Psychological Medicine, 47, 2177–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, & E-Risk Study Team (2002). Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 727–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mund M, Freuding MM, Möbius K, Horn N, & Neyer FJ (2019). The stability and change of loneliness across the life span: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 24, 24–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mund M, & Neyer FJ (2016). The winding paths of the lonesome cowboy: Evidence for mutual influences between personality, subjective health, and loneliness. Journal of Personality, 84, 646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mund M, & Neyer FJ (2018). Loneliness effects on personality. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nestler S, & Back MD (2013). Applications and extensions of the lens model to understand interpersonal judgments at zero acquaintance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5, 374–379. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Bates CJ, Sampson RJ, & Moffitt TE (2012). Systematic social observation of children’s neighborhoods using Google Street View: a reliable and cost-effective method. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Russell MA, Sampson RJ, Arseneault L, & Moffitt TE (2012). Supportive parenting mediates neighborhood socioeconomic disparities in children’s antisocial behavior from ages 5 to 12. Development and psychopathology, 24, 705–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (2018). Children’s and young people’s experiences of loneliness: 2018. London, UK: Office for National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, & Klein DN (2015). Psychometric comparison of self- and informant-reports of personality. Assessment, 22, 655–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavri S. (2015). Loneliness: the cause or consequence of peer victimization in children and youth. The Open Psychology Journal, 8, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, & Perlman D. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In Peplau LA & Perlman D. (eds), Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 1–8). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Pingault JB, O’Reilly PF, Schoeler T, Ploubidis GB, Rijsdijk F, & Dudbridge F. (2018). Using genetic data to strengthen causal inference in observational research. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19, 566–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spithoven AWM, Bijttebier P, Goossens L. (2017). It is all in their mind: A review on information processing bias in lonely individuals. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (2017). Stata statistical software: release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Trouton A, Spinath FM, & Plomin R. (2002). Twins early development study (TEDS): a multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems in childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 5, 444–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai F, & Reis HT (2009). Perceptions by and of lonely people in social networks. Personal Relationships, 16, 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhalst J, Klimstra TA, Luyckx K, Scholte RHJ, Engels RCME, Goossens L. (2012). The interplay of loneliness and depressive symptoms across adolescence: exploring the role of personality traits. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 776–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Barreto M, Vines J, Atkinson M, Long K, Bakewell L, Lawson S, & Wilson M. (2019). Coping with loneliness at university: a qualitative interview study with students in the UK. Mental Health & Prevention, 13, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S, & Carlson EN (2010). Self-knowledge of personality: do people know themselves? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 605–620 [Google Scholar]

- Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J, & Bowling A. (2000). Being alone in later life: loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 10, 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Williams RL (2000). A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics, 56, 645–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.