It has been 129 years since Louis Pasteur’s experimental protocol saved the life of a child mauled by a rabid dog, despite incomplete understanding of the etiology or mechanisms by which the miracle cure worked (1). The disease has since been well understood, and highly effective vaccines are available, yet Pasteur’s vision for ridding the world of rabies has not been realized. Rabies remains a threat to half the world’s population and kills more than 69,000 people each year, most of them children (2). We discuss the basis for this neglect and present evidence supporting the feasibility of eliminating canine-mediated rabies and the required policy actions.

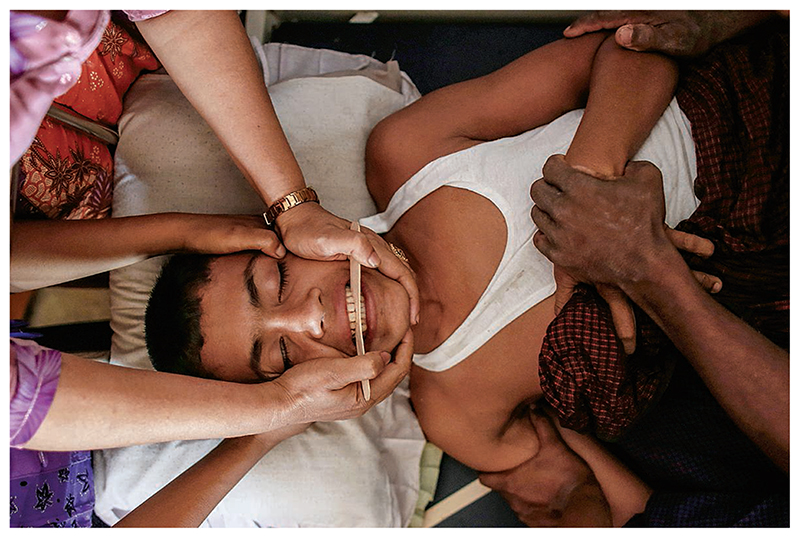

The human cost of rabies. Having not received post-exposure prophylaxis after a dog bite, a 16-year-old boy suffers the terrifying symptoms of rabies.

A Neglected Priority

Because of effective control of rabies in domestic dogs, it is no longer a disease of major concern in developed countries. In 2013, the one person diagnosed with rabies in the United States, which was predictably fatal, acquired the infection in Guatemala. In Western Europe no cases were reported in 2013; the one person who died of canine-mediated rabies in 2012 was bitten by a dog in India. With more than 95% of human cases occurring in Africa and Asia (3), largely in rural and impoverished communities, rabies threatens the world’s most marginalized people (see the first photo). Even in low-income countries, those from more affluent areas rarely die of rabies, as they are likely to promptly access highly effective post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). It is the poor who die; they are more frequently victims of rabid dog attacks, they suffer fatal delays in trying to access PEP, or simply cannot afford to pay for it (4).

Despite recent developments of simple, rapid, and highly accurate diagnostic methods (5), underdiagnosis and underreporting contribute to rabies neglect. The true incidence of human rabies in Asia and Africa is estimated to be between 20 and 160 times what is officially reported (3). The reasons for this are common among neglected diseases in low-income countries: The afflicted often do not reach medical facilities (4, 6) so are never recorded. For those who attend a medical facility, the similarity of rabies symptoms to other neurologic conditions, including cerebral malaria (7), renders clinical diagnosis without laboratory support challenging. Even where laboratory facilities exist, diagnostic samples are rarely collected, and where a clinical diagnosis is made, many cases are not reported to national or international authorities.

Coupled with this structural underdiagnosis and underreporting is the current approach to prioritizing disease interventions. Predominant disease burden metrics, such as disability-adjusted live years (DALYs), are important in focusing research and intervention agendas. However, decisions should also take into account the availability and effectiveness of control interventions and their implementation cost. For rabies, although a DALY score of 1.74 million lost per year is low compared with HIV, malaria, or tuberculosis, highly effective animal vaccines are available to control and eliminate disease in animal reservoirs and to prevent human deaths for a price considered highly cost-effective (8, 9).

Although global concerns relating to avian influenza have helped bridge medical and veterinary disciplines, a responsibility gap remains for zoonotic diseases not considered a global threat. For rabies, prevention through dog vaccination is the province of veterinary medicine, whereas PEP is the responsibility of physicians and nurses. Budgets to address rabies are rarely considered jointly, which results in everincreasing PEP costs if the disease is not tackled at the animal source. As rabies does not cause a high burden of disease in live-stock, compared with many economically important transboundary livestock diseases, dog vaccination has not been prioritized by veterinary services in low-income countries. However, if viewed more broadly as a societal burden, rather than by using a single health or economic metric, the impact of rabies and priority for its control is substantially elevated (2, 8).

A One Health approach, integrating medical and veterinary sectors, is important both to develop appropriate metrics for evaluating the disease burden, and to ensure shared operational responsibility for zoonosis control and prevention. Although international funding can facilitate this coordination (as shown for avian influenza), the most critical requirements are political commitment and building of trust and effective communication between sectors, which need not be prohibitively costly. Establishment of an effective interministerial Zoonotic Disease Unit in Kenya, which has rapidly developed integrated national plans for rabies control and elimination, provides a recent example of One Health coordination involving not only health and veterinary sectors but also wildlife services concerned with the threat that rabies poses to endangered wildlife.

Elimination Is Achievable

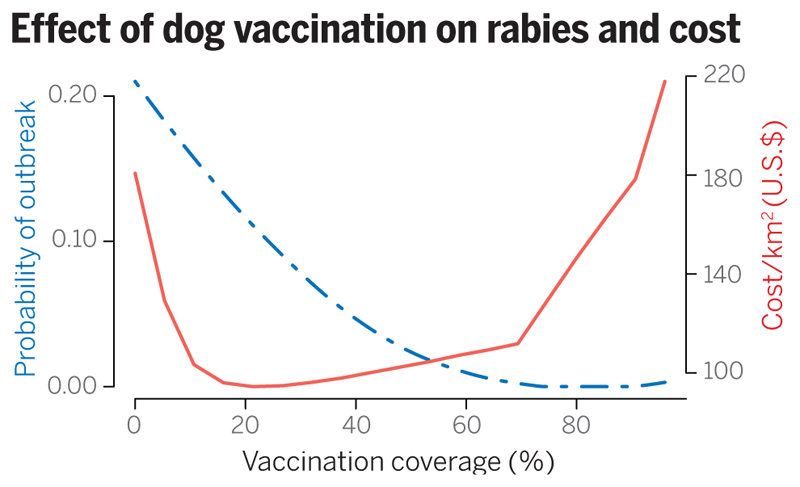

Although rabies virus is a multi-host pathogen, the domestic dog remains the principal reservoir and source of human rabies. The basic reproductive number for rabies (R 0, the average number of new cases generated by a single case) is consistently low (R 0 < 2) in dog populations worldwide, despite wide variations in population density (10). This suggests that transmission can be relatively easily interrupted through mass dog vaccination (see the chart). In contrast, although reducing dog density has been the first response to many rabies outbreaks (11), it has never been successful (12).

A growing body of evidence from Central and South America and pilot projects in Southeast Asia and Africa demonstrate the effectiveness of dog vaccination for preventing human rabies in both high- and low-income countries (13). Annual vaccination coverage of 70% controls and eventually eliminates the disease (see the second photo) (10).

Despite misperceptions of large “stray” dog populations, a high proportion of dogs are accessible for highly efficacious parenteral vaccination campaigns (14). Less than 11% of the dog population has been identified as ownerless in Zimbabwe, Chad, Tanzania, and South Africa (15). In densely populated Asian settings, where community dogs are common, techniques for vaccinating free-roaming dogs have been successfully applied (11).

Studies of rabies epidemiology in the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania and the surrounding communities demonstrate that domestic dogs, not wildlife, drive rabies transmission dynamics (16). Where dog rabies has been locally eliminated, the disease disappears in all species (15). This generates confidence that control of canine rabies is epidemiologically achievable and that large-scale elimination is a realistic goal. This has been demonstrated by the reduction in canine rabies by around 99% across Latin America, with elimination targets for the region set for 2015 (17).

Impact of dog vaccination coverage on rabies outbreak probability and cost.

The left axis and the dashed blue line show the probability of an outbreak of 10 or more cases being seeded by an introduced case under different levels of vaccination coverage. The right axis and solid red line indicate the total costs (U.S.$) per km2 of rabies control with increasing vaccination coverage. Vaccination coverage of 70% of the canine population reduces outbreak probability close to zero and is cost-effective. Cost data from (9), probability data from (10).

Is elimination of canine rabies economically feasible? Empirical and theoretical studies of mass dog vaccination campaigns in low-income countries reveal that vaccinating dogs against rabies is cost-effective up to the critical 70% vaccination coverage threshold (9), is significantly less expensive over the long-term than providing PEP to bite victims, and can result in substantial savings to the public health sector (8, 9, 18). These savings will be particularly relevant in Asia, where currently 90% of global PEP is administered (2, 3). To realize these savings, initial external financing may be needed to support investments in dog vaccination. However, to ensure sustainability, financing strategies need to involve governments and to have flexibility to encourage community engagement and to exploit new approaches to enhance cost-effectiveness, such as linking dog vaccination with other health-delivery platforms.

Across Disciplines and Borders

The only infectious diseases deliberately eradicated worldwide, smallpox and rinderpest, were within the exclusive domains of human and veterinary medicine, respectively. Eliminating canine rabies as a public health burden will require a One Health approach integrated across sectors. This has proven much easier to advocate in theory than to achieve in practice. Many low-income countries face a considerable challenge in coordinating and integrating activities across decentralized and fragmented veterinary and health care systems. This is exacerbated by a lack of linked regulatory policies.

Although growing scientific evidence is addressing misperceptions about canine rabies epidemiology and control, progress in many countries is still hampered by lack of political commitment and financing mechanisms. Pilot projects in Africa and Asia, which have supported initial investments in dog rabies control, demonstrate the power of catalytic funding to achieve operational progress, and allow veterinary and health services to move away from short-term or emergency responses toward a more coordinated and proactive program of disease prevention and control. Work is needed to determine how best to scale up from such pilot studies to the national and regional programs that will be needed for eventual elimination. International human and animal health organizations can play an important support role, for example, establishing mechanisms to ensure the affordable supply of human and animal vaccines and their effective cross-sectoral use.

A mass dog rabies vaccination clinic in Tanzania. This makeshift clinic was set up by the Serengeti Health Initiative.

An enduring challenge for global elimination is the ability to work effectively across national boundaries. This has been achieved successfully in the Americas through the RE-DIPRA network (Directors of National Rabies Control Programs), with specific budgets for cross-border control and the transparent sharing of surveillance and budgetary information resulting in a collective commitment to a public good, as well as constructive peer pressure. Newer regional rabies networks in Asia and Africa could develop along the same lines. Successful rabies control programs in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, supported through pilot funding, have resulted in transboundary networks and initiatives in neighboring countries. Initial success provides momentum for further success.

Canine rabies elimination meets all the criteria for a global health priority: It is epidemiologically and logistically feasible, costeffective, and socially equitable. Pasteur’s vision is within our reach—we only need to move the hand forward to grasp it.

Acknowledgments

K.H. is supported by the Wellcome Trust (095787/Z/11/Z), and L.T. by the UBS Optimus Foundation. Opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the supporting institutions.

References and Notes

- 1.Geison G. The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton Univ. Press; Princeton, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shwiff S, et al. Antiviral Res. 2013;98:352. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knobel DL, et al. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampson K, et al. PLOS Negl Dis. 2008;2:e339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lembo T, et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:310. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suraweera W, et al. Million Death Study Collaborators. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallewa M, et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:136. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zinsstag J, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904740106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzpatrick MC, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:91. doi: 10.7326/M13-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hampson K, et al. PLOS Biol. 2009;7:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putra AAG, et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:648. doi: 10.3201/eid1904.120380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morters MK, et al. J Anim Ecol. 2013;82:6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.02033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lembo T, et al. In: Dogs, Zoonoses, and Public Health. ed. 2. Macpherson CNL, Meslin F-X, Wandeler AI, editors. CAB International; Wallingford, UK: 2013. pp. 205–258. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davlin SL, Vonville HM. Vaccine. 2012;30:3492. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lembo T, et al. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lembo T, et al. J Appl Ecol. 2008;45:1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vigilato MA, et al. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120143. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Townsend SE, et al. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]