Abstract

Soft matter systems and materials are moving towards adaptive and interactive behavior, which holds outstanding promise to make the next generation of intelligent soft materials systems inspired from the dynamics and behavior of living systems. But what is an adaptive material? What is an interactive material? How should we delineate from classical responsiveness or smart materials? At present literature lacks a comprehensive discussion on these topics, which is however of profound importance to identify landmark advances, keep a correct and non-inflating terminology, and most importantly educate young scientist going into this direction. By comparing different levels of complex behavior in biological systems, this viewpoint strives to give some definition of the various different materials systems characteristics. In particular it highlights the importance of thinking in the direction of training and learning materials, and metabolic or behavioral materials, as well as communicating and information-processing systems. This viewpoint aims to also serve as a jumping board to further connect the important fields of systems chemistry, synthetic biology, supramolecular chemistry and nano- and microfabrication/3D printing with advanced soft materials research. A convergence of these disciplines will be at the heart of empowering future adaptive and interactive materials systems with increasingly complex and emergent life-like behavior.

Keywords: responsive materials, adaptive materials, interactive materials, learning materials, training materials, smart materials, intelligent materials, systems chemistry, metamaterials

Introduction

What is an adaptive material or system? A simple question, is it not? But how is an adaptive material different to a responsive one? How should we further delineate interactive materials or systems? As soon as one engages in such discussions, it becomes obvious that such questions are challenging to answer. One of the reasons is the fact that there are hardly any clear-cut definitions or comprehensive discussions available in literature. However, as research in soft matter materials and materials systems is increasingly moving towards higher levels of complexity and takes increasing inspiration from the concepts of living species, it feels imminent and of high importance to foster the discussion on this topic and provide a roadmap to evolve synthetic systems from responsive to adaptive and interactive systems and materials. This is not only important in the context of highlighting landmark advances of future systems over present ones, but also relevant for the education of the next generation of researchers going to operate in the field. Furthermore, we are often faced with an inadequate inflation of terminology, which may also not help to develop new conceptual research directions in a clear manner. It is the objective of this viewpoint to discuss relevant conceptual differences between these material classes (responsive vs adaptive vs interactive) in a generally accessible way – albeit certainly from a personal perspective – and fertilize and contribute to this discussion, and hopefully provide some definitions and a roadmap for future materials system design. Given the brevity of this viewpoint, it will only relate at selected places shortly to some existing literature, but has the main objective on communicating concepts underlying advanced adaptivity and interactivity.

Responsive Systems

Let us first look back at the class of stimuli-responsive materials, which have been an outstanding success story for the design of advanced switchable soft materials that continue to widely impact forefront materials research and consumer technologies for sensors, photonics, biomaterials and other applications.[1] Those typically contain molecular or (bio)macromolecular segments that respond to a change in the environment (e.g. pH, temperature, light, electric or magnetic field) with a change e.g. in the conformation, connectivity, polarity, solubility or absorptivity that translates on a higher level in changes in the self-assembly behavior or a material property such as swelling/deswelling, contraction/expansion, mechanical stiffening or softening, conductivity, color, fluorescence, permeability and so on. The change in the properties from state A into state B remains typically stable until the countertrigger is given in such systems, whereupon the state/property reverts back to the original one (state A). The systems are characterized by a high reliability and ideally by low fatigue, meaning that multiple cycles can be achieved and that the systems are highly reversible – a feature that is of critical importance for applications. In terms of energy landscapes the systems change typically from one equilibrium configuration to another equilibrium configuration by modulation of the energy landscape of the environment upon application of the trigger (see also Figure 2 below). This can be most easily understood for temperature or pH changes. The energy needed to make this change needs to be taken up by these systems and is not intrinsically present in the system. Such materials have been correctly denoted as smart and responsive materials, and although terminology suggests even terms like intelligent materials, one really has to critically question how intelligent such systems are. Certainly, the combination with logic gates has contributed to empower such switchable and smart materials with higher responsivity.

Figure 2.

Responsive Systems: (a) Energy landscapes describe the switching of properties between State A and State B between two energy minima that are obtained by modulating the energy landscape of the environment after applying a trigger (e.g. pH, temperature, etc.). Note that State B could also sit in a metastable minimum. The switching process (trigger/countertrigger) is highly reversible and characterized by little to no fatigue. Adapted with permission from Refs. [18]

On a fundamental level, it may be noted that the state B may also sit in a relatively deep metastable energy well, such as for the case of azobenzenes (and their materials) that can be switched using light from a stable trans conformation to a metastable cis conformation, which relaxes back to the ground state by thermal energy.[2] This has given rise to the important design of dissipative systems, where one can argue that the change to state B is only stable as long as the trigger (light; or also other external fields) is applied to the system and then goes back to ground state A in an autonomous fashion. Hence one can speak about systems that adapt to a trigger, e.g. field intensity. Such systems are definitely an evolution from classical responsive system, but as we will learn below, constant energy dissipation alone is not a criteria to make adaptive systems on highly complex levels.

Adaptivity concepts in biology

Next, let us look at biological systems on different length and complexity scales, and identify conceptual requirements to arrive at highest levels of adaptivity (Figure 1). A comparison between the actuation principles of a pine cone and of a venus fly trap may serve as a first instructive example. The pine tree cone can respond to the humidity of its surrounding by an opening of the flaps to release the seeds under favorable growth condition (wet; (Figure 1A)).[3] The actuation is triggered by humidity-induced swelling of confined hygroscopic layers, that give rise to an anisotropic actuation response. These processes can and have widely been mimicked in synthetic systems using bilayer actuators.[4] The process is slow because the energy for this change is provided through moisture uptake and hence coupled to mass transport. The principles of a pine cone actuation should be considered as a responsive system. In striking contrast, the venus fly trap operates fundamentally differently and on much higher levels of spatiotemporal complexity (Figure 1B).[5] The venus fly trap is composed of its actuation organ that contains sensory hairs. Only if the sensory hairs are triggered three times in a given time frame, the trap is in fact triggered to be closed. Hence, the sensory input is temporally correlated and there is an information processing system in the context of a temporal threshold sensing function to prevent inappropriate closure towards e.g. a rain drop to efficiently catch a prey and to prevent wasting energy. Importantly, the trap can close very quickly, because the open form is located in a metastable energy well and confined on one side of a snap-buckling configuration, and only the energy barrier needs to be overcome to provide a quick response. In simple terms, fast and quick response can only be provided in such a system, because it is full of energy, “energized” like a spring, and because it can release this energy quickly when passing over the energy barrier. The closed state is the equilibrium state. Despite progress in actuators mimicking the general closing movement, the real complexity of the venus fly trap, being adaptive to a time correlated trigger allowing for a quick relaxation from a metastable state, is an unsolved challenge of fundamental importance for the design of soft robotics. However, the snap buckling motion has recently been realized and allowed to increase the response time drastically.[6] The venus fly trap presents one of the fastest and highly adaptive plant actuator organ systems, that works without a brain, simply by local chemically and structurally organized signal processing systems.

Figure 1.

Selected examples of biological responsive, adaptive and interactive behavior on increasing levels of complexity. The grey boxes highlight important concepts in the various examples. Reprinted and adapted with permissions from Ref.[3, 5, 7, 8, 12–14]

Even higher levels of adaptivity are encountered for instance in cephalopods that can adapt to the color, brightness and topography of the environment to camouflage them against predators (Figure 1D).[7, 8] Interestingly enough, cephalopods are considered color blind, which means that the adaptivity has to be provided through local intelligence and is not based on an eye-brain-actuator system. Indeed, the combination of sensory modules in the skin cells, being able to discern coloration and brightness, and the coupling through messenger molecules and nervous transport (yet likely not based on the central nervous system), allow the iridophores and chromatophores to provide the adaptive camouflaging through local intelligence. The important concept to learn here is the adaptation to distinct functional plateaus through an intelligent photo-chemical-structural (sensor-processor-actor) biological reaction network.

Focusing more on cellular and molecular biological systems, additional features and requirements of complex adaptation mechanisms can be identified. Here we start from the smallest relevant system feature and move upwards in scales of length and complexity. Several molecular subsystems in cells are operated in a dissipative, energy-consuming state, in which a state is maintained by constant influx and dissipation of chemical energy (mostly ATP and GTP; Figure 1C).[9] This concerns for instance the cytoskeleton fibrils, and in particular the microtubule filaments are known for their steady state dynamics manifesting in dynamic instabilities that balance polymerization (related to GTP uptake; energy uptake) and depolymerization (related to GTP hydrolysis; energy loss). The microtubules are among other features designed for spatial search and their tracks emerging from the centrosome can be stabilized from a dynamic to a quasi-static fashion using appropriate biochemical signals to provide an adaptive reconfiguration of the cell shape and function. Intuitively it seems like a waste of energy to operate systems in such a driven, energy-consuming state, however, one has to realize that such systems operating in a flux-state can adapt and reconfigure their structures much more quickly to a changing signaling landscape compared to being in a static fashion as the reorganization of static fibers through the crowded environment of a cell would consume much more energy and take more time, similar as a complete depolymerization and formation of a new track would do. Hence, the learning lesson with respect to quick adaptation is the fact that driven systems with precisely adjustable dynamics in the steady state (in the flux state) are advantageous to provide fast adaptation and reconfiguration. Despite progress in the direction of chemically fueled systems, the manifestation and control of dynamics in a chemically driven steady state continues to be a grand challenge, which in synthetic system has only been reported for few examples.[10, 11]

On a larger length scale, stem cells are relevant examples of entities undergoing outstandingly complex adaptation processes with distinct functional outcomes, that is, different differentiation lineages, whereby a complex sensory landscape is probed and processed (Figure 1E). For instance, for mesenchymal stem cells, it is known that biochemical signaling cues, topographical material contacts and patterns, static and dynamic mechanical properties, as well as matrix degradability can guide the stem cell fate into different functional outcomes.[15, 16] This implies that signals are weighed against each other and processed far beyond the operation of simple logic gates and that non-linear feedback, feedforward and thresholding signal processing routines operate in an interconnected fashion in the underlying biochemical reaction networks.

Such a computation in the inside is further completed by colonies of interacting bacteria or cell populations that can undergo quorum sensing and/or morphogenesis so that a different functional outcome is obtained in a collective fashion by communication among different entities (Figure 1F).[17] Quorum sensing is the ability to detect and to respond to the cell population density by gene regulation using chemical hormone-like messengers (so-called autoinducers). A striking example is the bioluminescence of vibrio fischeri that is turned on at high cell density. At a threshold population density, enough autoinducer signaling molecule is available (that diffuses freely in the population) to activate the transcription of the light-producing luciferin, while at the same time more of the autoinducer signaling molecule producer synthase is produced. Hence on a molecular level, the autoinducer is autocatalytically supported and amplified through a positive feedback loop. This process should really be seen as a synchronization, because it allows the otherwise unicellular prokaryote to function as a multicellular “organism”, which is otherwise the domain of eukaryotes.

A generalization of such communication and synchronization principles of entities also relates to the challenge to conduct and transduce a local stimulating event to a global and collective change or adaptation of properties, which is profoundly difficult to realize in synthetic systems as signal conduction based on simple diffusion leads to a dilution of the signal and to insufficient signal conduction speeds over long distances.

Management of Energy Landscapes

Based on the guiding principles discussed above, it becomes evident that the management of and the navigation within complex energy landscapes is of profound importance. As a starting point, a classical responsive system switches mostly between two different low energy states (state A and state B) by modulation of the energy landscape due to the application of a trigger. Repeated addition of trigger and countertrigger always induces the same change. Such a change can go classically into a different equilibrium state or can go also into slightly metastable states. However, during the repetitive operation of such trigger/countertrigger signals, there is no change in the underlying basic energy landscapes.

In an adaptive system, the behavior is different. Here the repeated addition of a signal can lead phenomenologically to various scenarios and in principal we need to distinguish between adaptation of a property or adaptation of a property change by rewiring of a switching pathway (Figure 3). First, the system may stop responding to the same signal after a number of trigger/countertrigger cycles – this is the most classical example of adaptation (Figure 3b). This implies that either the energy minimum has disappeared or that the energy barrier to go into the new minimum has increased. This should not be interpreted as a simple fatigue of the system, but rather be interpreted in the direction that the signal is now being processed differently. Second, the system adopts a distinctly different functional state after a certain number of trigger/countertriggers has been applied (Figure 3a). This implies that a different energy well has become deeper, or, more importantly in a multistable energy landscape, it has become more accessible by decreasing the energy barrier to enter it (see also Figure 4a). Third, the system starts to undergo a change in properties only once a certain amount of trigger/countertrigger cycles has been applied, while it did previously not show any functional adaptation. Similar to case two this corresponds to the formation of an energy well or to the lowering of an energy barrier to make it accessible. Note that all of these concepts relate to the principles of conditioning and simple reinforced learning effects by training. This in turn leads to the consideration of a certain memory function within the systems. A higher level of complexity can be discussed with respect to the frequency of such events (trigger/countertrigger), meaning that if trigger/countertrigger events are not occurring in a sufficient frequency or are discontinued, the memory function does not built up or gets lost, respectively (Figure 3e-h). Such an autonomous loss of a memory implies clearly that the trained function has been residing in a metastable energy well that allows interconversion back to the ground state (non-trained).

Figure 3.

Adaptivity through training of a property change through rewiring of a switch (top, a,b) and training of properties (bottom, e). (c,d) Repeated application of the trigger/countertrigger switch leads to (c) adaptation to a new functional plateau or to (d) suppression of the property change. The change in the energy landscape in (b) corresponds to the adaptation in (c). (f-h) Intensity and frequency-dependent adaptation of a material property through repeated application of a signal, and forgetting of a property through relaxation from a metastable, trained state. The arrows in (a,b) and (e) indicate the changes to the energy landscape during repeated addition of trigger/countertrigger cycles or signals.

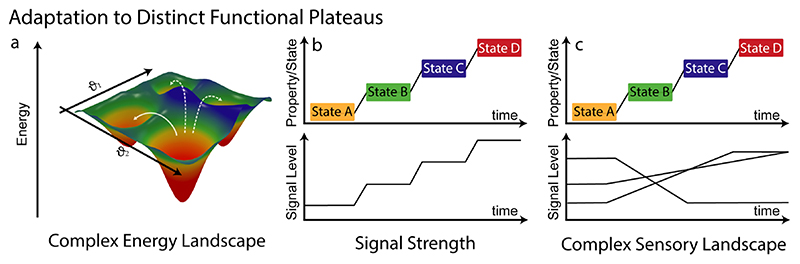

Figure 4. Adaptation to distinct functional plateaus as a function of signal strength or in the presence of a complex sensory landscape with various signal inputs that need to be correlated also in a non-linear manner.

How close are we to such materials that can be trained? Traditionally, in the field of polymer science it is well known that for instance semi-crystalline polymer materials can undergo strain-hardening by crystallization, which of course strengthens such materials. However, very often this results in fundamentally different sample geometries due to inelastic deformation and freezing of topologies. Very recently, a first self-strengthening hydrogel was reported, that could, during cyclic deformation, build up a more strongly crosslinked network, due to chain scission-induced generation of radicals that could initiate polymerization of distributed monomers and crosslinking.[19] A distinct strength increase was observed and the material was conserved in its macroscopic shape. Additionally, application of supercritical stress was also shown to allow for a transition from a non-conducting polymer to a semi-conducting one, hence providing a functional adaptation to a new property by application of a signal.[20] In general, the advances in mechanochemistry are inspiring for the generation of mechanically adaptive materials and the incorporation of latent reactivity using latest generations of force- and work-programmable mechanophores shows great promise towards training of properties or of switching behavior.[21, 22] Some of the real future challenges are to implement intensity and frequency-dependent memory functions, or enable a tailored, autonomous loss of the memory, using precise molecular control mechanisms and without altering other properties of the material that are relevant for an application.

In all of the concepts it becomes evident that changes in the energy landscape do not come for free, but that energy needs to be provided to the systems to adapt their landscape and the underlying signal processing network. This energy may be provided through influx of chemicals, light or also mechanical stimuli. If the energy is already localized within the system, such as in metastable configurations or in dissipative flux-like systems, the response time and the need to provide additional energy may be reduced, but a constant operation far-from-equilibrium may not be an ultimate necessary requirement to reach adaptation.

Computation and Communication

The second important feature that becomes evident from the biological principles discussed above (Figure 1) is the fact that we need to empower future adaptive and interactive materials and systems with advanced soft computational mechanisms that allow to distinguish and correlate multiple signal inputs in complex sensory landscapes. Compared to classical responsive systems, there have been significant advances with respect to the implementation of logic gates and coupled logic gates, which has led to materials and systems that can follow binary computation. However, adaptation to distinct functional plateaus depending on signal strength in a complex sensory landscape requires to correlate and weigh signals with each other, in particular regarding thresholding and rectification (Figure 4). Such a correlation requires to go beyond simple logic gates and demands the implementation of non-linear computational algorithms as available in complex chemical reaction networks to allow for suppression, thresholding, and/or amplification of a signal using positive and negative feedback.[23] In the systems chemistry field, there has been much progress in advanced chemical reaction networks to reach self-oscillating systems, or also bistable systems that can give rise to memory effects needed for reshaping energy landscapes. Undoubtedly, DNA-based computers and also protein-based computing systems are leading the developments there. For instance, recently a 6-bit Boolean algorithm-processing DNA computer with proof-reading and a self-assembling readout was proposed, and earlier systems for reaching consensus decisions, bistability (memories) and programmable oscillators were discussed.[24–26] Unfortunately, the connection of such advances in systems chemistry towards materials are still limited, which calls for a closer collaboration at the interface of the systems chemistry and advanced materials. Yet, for instance, protein-based hydrogels that can count signal events have been proposed.[27] The connection of the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction, the most robust chemical redox oscillator, to polymeric materials has been one landmark to reach oscillatory behavior in polymer hydrogels (and a kind of homeostasis),[28] and clearly highlights that emergent behavior can be realized by combining systems chemistry approaches with responsive materials.

One of the most promising interesting concepts for advanced adaptation empowered by signal processing routines would be Pavlovian adaptation, which is a simple form of associative learning (Figure 5).[29] The classic example of the Pavlovian dog, which salivates initially only when food is provided (unconditioned stimulus), but learns to salivate also later when it hears the steps of the assistant bringing the food or when a bell is rung prior to food provision (i.e. an initially neutral stimulus turns into a conditioned stimulus), demonstrates that signal processing routes need to become intertwined and altered due to repeated and time-correlated signal exposure. Simplistic processes in this direction have been proposed theoretically and realizations might not be too far, at least for systems operating in the realm of synthetic biology.[30–32] One of the most critical aspects in associative learning is the fact that the signal processing routes have to be truly interconnected with a re-routing of the signal processing by installation of a memory element, and that it shows important differences to simple conditioning (i.e. programming, Figure 5e). In external conditioning (programming) the signal processing route of the neutral stimulus may just be altered to lead to the desired output, but without actually re-routing the signal processing internally along the correct unconditioned stimulus pathway, which is the true relevance of associative learning.

Figure 5. Adaptation through associative learning (Pavlovian adaptation).

(a) The principles of conditioning of the salivation of a dog by interconnecting a ringing bell with the provision of food. (b) Unconditioned stimulus (food) leads to unconditioned response (salivation), (c) a neutral stimulus without conditioning leads to no conditioned response (no salivation) and (d) during conditioning and after conditioning the dog has connected both signals and later responds to the neutral stimulus (bell) with a conditioned response (salivation) even in absence of the unconditioned stimulus (food). (e) A rewiring of the signal processing pathways (W(US), W(NS) and W(CS)) occurs in a way that the neutral stimulus is interconnected to the processing of the unconditioned stimulus. A memory module (darker grey) is developed.

Beyond using chemical (pH, salt) or physical signals (temperature, light) that interact with relatively homogeneous systems and materials, the possibilities of implementing structural logic in mesoscopically structured solids, such as in snap buckling 3D printed beams that have bistable or multistable energetic configuration, is still at the infancy of exploration to reach complex adaptation and computation. Yet the increased capabilities of 3D printing towards complex mechanical systems design holds great promise to provide alternative signal processing routines using mechanical metamaterial principles.[33, 34] This in turn also relates to the need of designing hierarchical and bridging feedback mechanisms, such as chemo-mechanical, chemo-structural or opto-mechanical feedback, which allows to address different time scales and methodologies beyond the capabilities of simple bulk chemical reaction networks. To this end, there has been relevant progress for instance in the field of homeostatic self-oscillating systems embedding catalytic, heat-producing solid posts into hydrogel layers with the capability for anisometric actuation. In those, the catalytic activity and heat is self-regulated through heat-triggered immersion of the catalytic posts into a temperature-sensitive hydrogel, leading to a temporary suppression of the catalytic reaction. This results in a temporarily delayed return to the starting point and the restart of the cycle.[35] Other relevant opto-mechanical feedbacks include for instance the operation of a soft robotic gripper using light reflectance of objects in light emitting and light-responsive liquid crystalline elastomer (LCE) devices[36, 37], or the partial self-shading of light exposed LCE actuators, leading to oscillating LCE stripes.[37]

Of high importance is also the need to find pathways to engineer efficient short- and long-distance communication. Simple chemical diffusion only operates effectively over short distances, essentially being based on contact mechanisms, but on longer distances a concentration gradient of a signal would simply vanish to subcritical levels. A promising alternative is to use reaction/diffusion systems, which are mostly based on autocatalytic reaction mechanisms with a positive feedback that allow to propagate chemical waves from a local disruptive event to a global change (Figure 6). This has been realized for autocatalytic enzymatic pH reactions to for instance provide signal transport on photonic structures, or for enzymatic and non-enzymatic DNA amplification methods or other chemical systems.[38–40] The energy in such systems is provided through a pro-signal substrate that is converted in an energetically downhill process to the actual signaling molecule, that itself activates more catalysts driving the reaction front forward without loss of concentration. For larger and non-chemical systems, relevant long distance signal distribution has also been suggested for printed mechanical metamaterials composed of bistable beams that store and release elastic energy along the path of the propagation of a mechanical wave[41]. Additionally in the mechanical metamaterials world, camouflaging of mechanical topographies[42] has been reported which can be considered a signal damping mechanism.

Figure 6.

Adaptation of a material from a local stimulus to a global change can be achieved using chemically powered reaction/diffusion systems with autocatalytic amplification of the signal B using a proB substrate and an amplifying catalyst that becomes activated through the presence of B.

Towards interactive materials and systems

One of the most critical aspects to move towards systems that can feature interactivity is to implement active communication between adaptive entities, or between an adaptive entity and an adaptive surrounding, which appears to be of particular relevance for computing delivery systems in the body or for the communication of for instance hydrogel materials with cells to provide interactive cell niche materials. One key towards interactivity is to go beyond passive adaptation and provide active feedback, which can include foremost the emission of chemical counter-messengers, or physical counter-stimuli, which in turn will trigger a secondary response of the interacting entity in a system, so that both entities in fact adapt continuously towards each others signaling systems to arrive at crosswise regulation and self-regulation (Figure 7). It is obvious that this will require even greater advances in the computational abilities of materials and systems to provide an adaptive communication as the entities evolve jointly, leading potentially as an ultimate goal to biosynthetic hybrid morphogenesis (co-development and co-evolution). Other aspects, such as simplistic self-replication (not graphically shown) have been discussed for self-assembling systems[43, 44], quorum sensing has been addressed in bistable pH-systems, chemical oscillators or in the DNA world[45–47], and collective behavior in light-driven colloidal systems have been realized using competition between self-propulsion and an attraction by osmotic and phoretic effects, allowing to synchronize motion in what was termed living crystals.[48]

Figure 7. From adaptive materials to interactive materials and systems.

Concluding Remarks and Outlook

The intention of this article has been to elaborate on the differences between classical stimuli responsive materials and the next generation of materials systems providing true adaptivity and interactivity. It is important to note that this article is written from the soft matter and soft materials perspective, and other communities such as robotics, informatics, artificial intelligence or pure biology may have complementing opinions on the topic of adaptivity and interactivity. Adaptivity occurs on different levels of complexity and needs to be empowered by computational methods to allow increasingly complex decisions to be made – be it on a (bio)chemical reaction network basis or on a structural metamaterial basis or based upon a combination of both. Adaptation can be discussed in the context of navigating inside complex sensory landscapes to adapt to a distinct functional plateau or with respect to an evolution and development of the functional response. One of the most striking phenomenological concepts in adaptivity is to think in the direction of learning, and how repetitive and time-correlated signal exposure can lead to adaption in the context of training or associative learning. In all of these cases, changes to the energy landscape, in which the switches and signals operate, occur, and energy needs be provided to organize these changes. It is also evident that rapid adaptive behavior requires to trigger systems based on a metastable “energized” configuration, or requires systems to be operated in dissipative “flux-like” states as the energy is already provided inside of the system and does not need to be delivered. The constant operation from energy-rich metastable states or within dissipative systems may however not be an ultimate necessity, but it influences reaction or adaptation speed.

A true challenge emerges when considering that many successful soft material classes are not in a hydrogel state, but practically all advanced soft matter computational methods in the realm of (bio)chemical reaction networks are dependent on water (or solvent). Hence, we need to start devising regulatory network strategies that can operate in solvent-free bulk. Mechanical metamaterials and deformation-dependent feedback may provide some alternatives, but very specific chemistries may also be operational in a bulk system.

Going towards interactive materials requires ultimately to think of systems of interacting materials, components or subspecies between which active communication occurs so that the parts of the system adapt conjointly in an interactive fashion with truly emergent behavior, such as synchronization, collective behavior, self-replication, morphogenesis or biosynthetic co-development/co-evolution. Large possibilities arise at this frontier to making the next generation of interactive materials system.

How can all of this be managed? It is obvious that a further integration of disciplines needs to be fostered. Stimuli-responsive advanced materials and hierarchically self-assembling supramolecular and polymeric systems have been developed to very sophisticated levels, and, the emerging methods in top-down nano-to-microfabrication, 3D printing and microfluidics will allow to complement these hierarchical bottom-up self-assembly strategies and materials designs to allow for compartmentalization and true hierarchical system integration. Concurrently, systems chemistry, synthetic biology and also mechanical metamaterials have been advancing in designing increasingly complex behavior. However, the further integration of these fields, in particular materials science and systems chemistry, and materials science and synthetic biology, will be of outstanding relevance to lay the foundation for adaptive and interactive next generation materials systems, that one needs to think about in the context of metabolic materials systems or behavioral materials. A common language and cross-disciplinary understanding needs to be formed and this will most likely be best supported by tutorial reviews at the interface[49] and by focused conference series bringing together these disciplines. The best is yet to come and it will be exciting to see where the fields stand in 10 years from now.

Acknowledgements

A.W. acknowledges funding from the European Research Council in the framework of a ERC Starting Grant (TimeProSAMat; 677960) and by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC-2193/1 – 390951807. A.W. thanks Francisco Lossada and Laura Heinen for help with preparing some figures. A.W. acknowledges discussions with various colleagues, most notably Martin Möller, Olli Ikkala, Joachim Spatz and the livMatS team at Freiburg.

Biography

Andreas Walther leads the A3BMS Lab at the Institute for Macromolecular Chemistry at the Albert-Ludwigs-University in Freiburg (Germany). His research interests concentrate on developing and understanding hierarchical self-assembly concepts inside and outside equilibrium, and on using them to create active, adaptive and autonomous bioinspired material systems (A3BMS). Life-inspired materials systems powered by chemical fuels and orchestrated through chemical reaction networks are one ultimate research goal. He graduated from Bayreuth University in Germany in 2008 with a Ph.D. on Janus particles and pursued postdoctoral studies with a focus on biomimetic hybrid materials at Aalto University (Helsinki, Finland). After establishing his independent research group at the DWI – Leibniz Institute for Interactive Materials in Aachen in 2011, he was appointed to his present position in Freiburg in 2016. A. Walther has published ca. 150 papers (h-index 55) and has recently been awarded the Bayer Early Excellence in Science Award (for Materials), the Reimund Stadler Young Investigator Award of the German Chemical Society, a BMBF NanoMatFutur Research Group, an ERC Starting Grant, as well as the Hanwha-Total IUPAC Young Scientist Award awarded at the biannual IUPAC World Polymer Congress 2018. He is a fellow of both the Freiburg (FRIAS) as well as the Strasbourg Institute for Advanced Studies, and a founding PI and board member of the DFG livMatS Cluster of Excellence on “Living, Adaptive and Energy-Autonomous Materials Systems”.

Andreas Walther leads the A3BMS Lab at the Institute for Macromolecular Chemistry at the Albert-Ludwigs-University in Freiburg (Germany). His research interests concentrate on developing and understanding hierarchical self-assembly concepts inside and outside equilibrium, and on using them to create active, adaptive and autonomous bioinspired material systems (A3BMS). Life-inspired materials systems powered by chemical fuels and orchestrated through chemical reaction networks are one ultimate research goal. He graduated from Bayreuth University in Germany in 2008 with a Ph.D. on Janus particles and pursued postdoctoral studies with a focus on biomimetic hybrid materials at Aalto University (Helsinki, Finland). After establishing his independent research group at the DWI – Leibniz Institute for Interactive Materials in Aachen in 2011, he was appointed to his present position in Freiburg in 2016. A. Walther has published ca. 150 papers (h-index 55) and has recently been awarded the Bayer Early Excellence in Science Award (for Materials), the Reimund Stadler Young Investigator Award of the German Chemical Society, a BMBF NanoMatFutur Research Group, an ERC Starting Grant, as well as the Hanwha-Total IUPAC Young Scientist Award awarded at the biannual IUPAC World Polymer Congress 2018. He is a fellow of both the Freiburg (FRIAS) as well as the Strasbourg Institute for Advanced Studies, and a founding PI and board member of the DFG livMatS Cluster of Excellence on “Living, Adaptive and Energy-Autonomous Materials Systems”.

References

- [1].Stuart MAC, Huck WTS, Genzer J, Müller M, Ober C, Stamm M, Sukhorukov GB, Szleifer I, Tsukruk VV, Urban M, Winnik F, et al. Nature Mater. 2010;9:101. doi: 10.1038/nmat2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kathan M, Hecht S. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:5536. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00112f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Reyssat E, Mahadevan L. Soc J R. 2009;6:951. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ionov L. Mater Today. 2014;17:494. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Poppinga S, Joyeux M. Phys Rev E. 2011;84:041928. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.041928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fan W, Shan C, Guo H, Sang J, Wang R, Zheng R, Sui K, Nie Z. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaav7174. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav7174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kreit E, Mäthger LM, Hanlon RT, Dennis PB, Naik RR, Forsythe E, Heikenfeld J. J R Soc. 2013;10:20120601. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hanlon R. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R400. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gierke S, Kumar P, Wittmann T. In: Methods Cell Biol. Cassimeris L, Tran P, editors. Vol. 97. Academic Press; 2010. p. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boekhoven J, Hendriksen WE, Koper GJM, Eelkema R, van Esch JH. Science. 2015;349:1075. doi: 10.1126/science.aac6103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Heinen L, Walther A. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaaw0590. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw0590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dunlap PV, Gould AL, Wittenrich ML, Nakamura M. J Fish Biol. 2012;81:1340. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Torres-Rendon JG, Femmer T, De Laporte L, Tigges T, Rahimi K, Gremse F, Zafarnia S, Lederle W, Ifuku S, Wessling M, Hardy JG, et al. Adv Mater. 2015;27:2989. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gierke S, Kumar P, Wittmann T. In: Methods in Cell Biology. Cassimeris L, Tran P, editors. Vol. 97. Academic Press; 2010. p. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brusatin G, Panciera T, Gandin A, Citron A, Piccolo S. Nat Mater. 2018;17:1063. doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0180-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vining KH, Mooney DJ. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:728. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Waters CM, Bassler BL. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Heinen L, Walther A. Soft Matter. 2015;11:7857. doi: 10.1039/c5sm01660f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Matsuda T, Kawakami R, Namba R, Nakajima T, Gong JP. Science. 2019;363:504. doi: 10.1126/science.aau9533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen Z, Mercer JAM, Zhu X, Romaniuk JAH, Pfattner R, Cegelski L, Martinez TJ, Burns NZ, Xia Y. Science. 2017;357:475. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].May PA, Moore JS. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:7497. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35463b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Merindol R, Delechiave G, Heinen L, Catalani LH, Walther A. Nat Commun. 2019;10:528. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08428-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].van Roekel HWH, Rosier BJHM, Meijer LHH, Hilbers PAJ, Markvoort AJ, Huck WTS, de Greef TFA. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:7465. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00361j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chen Y-J, Dalchau N, Srinivas N, Phillips A, Cardelli L, Soloveichik D, Seelig G. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:755. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Padirac A, Fujii T, Rondelez Y. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2012;109:E3212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212069109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Woods D, Doty D, Myhrvold C, Hui J, Zhou F, Yin P, Winfree E. Nature. 2019;567:366. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Beyer HM, Engesser R, Hörner M, Koschmieder J, Beyer P, Timmer J, Zurbriggen MD, Weber W. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1800472. doi: 10.1002/adma.201800472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yoshida R, Ueki T. NPG Asia Mater. 2014;6:e107. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pavlov PI. In: Conditioned reflexes. Anrep GV, translator. Oxford University Press; London: 1927. Conditioned Reflexes. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sorek M, Balaban NQ, Loewenstein Y. PLOS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McGregor S, Vasas V, Husbands P, Fernando C. PLOS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gandhi N, Ashkenasy G, Tannenbaum E. J Theor Biol. 2007;249:58. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bückmann T, Stenger N, Kadic M, Kaschke J, Frölich A, Kennerknecht T, Eberl C, Thiel M, Wegener M. Adv Mater. 2012;24:2710. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Berwind MF, Kamas A, Eberl C. Adv Eng Mater. 2018;20:1800771 [Google Scholar]

- [35].He X, Aizenberg M, Kuksenok O, Zarzar LD, Shastri A, Balazs AC, Aizenberg J. Nature. 2012;487:214. doi: 10.1038/nature11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wani OM, Zeng H, Priimagi A. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15546. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gelebart AH, Jan Mulder D, Varga M, Konya A, Vantomme G, Meijer EW, Selinger RLB, Broer DJ. Nature. 2017;546:632. doi: 10.1038/nature22987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Heuser T, Merindol R, Loescher S, Klaus A, Walther A. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1606842. doi: 10.1002/adma.201606842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zadorin AS, Rondelez Y, Galas J-C, Estevez-Torres A. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114:068301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.068301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Abe K, Kawamata I, Nomura S-iM, Murata S. Mol Syst Des Eng. 2019;4:639. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Raney JR, Nadkarni N, Daraio C, Kochmann DM, Lewis JA, Bertoldi K. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2016;113:9722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604838113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bückmann T, Thiel M, Kadic M, Schittny R, Wegener M. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4130. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sadownik JW, Mattia E, Nowak P, Otto S. Nature Chem. 2016;8:264. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dadon Z, Samiappan M, Safranchik EY, Ashkenasy G. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:12096. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bánsági T, Taylor Annette F. J R Soc Interface. 2018;15:20170945. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Taylor AF, Tinsley MR, Wang F, Huang Z, Showalter K. Science. 2009;323:614. doi: 10.1126/science.1166253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gines G, Zadorin AS, Galas JC, Fujii T, Estevez-Torres A, Rondelez Y. Nature Nanotechnol. 2017;12:351. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Palacci J, Sacanna S, Steinberg AP, Pine DJ, Chaikin PM. Science. 2013;339:936. doi: 10.1126/science.1230020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Merindol R, Walther A. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:5588. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00738d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]