Abstract

Objective

To estimate the impact of antiretroviral therapy (ART) on population-wide adult life expectancy (LE).

Study design

A population-based open cohort study with repeated HIV status measurements and registration of vital events in south-western Uganda (1991-2012).

Methods

Non-parametric survival analysis techniques are used for estimating trends in (i) the adult LE of the general population (aged 15 and above), (ii) the adult LE by HIV status, and (iii) the adult LE deficit associated with HIV. The LE deficit is estimated as the difference between overall LE and LE of the HIV negative population. All estimates are disaggregated by sex.

Results

Between 1991-1993 and 2009-2012, population-wide adult LE increased from 39.3 (95%-CI: 35.9-42.8) to 56.1 years (95%-CI: 54.0-58.5) in women, and from 38.6 (95%-CI: 35.4-42.1) to 51.4 years (95%-CI: 49.2-53.7) in men. Most of the adult LE gains coincide with the introduction of ART in 2004; as evidenced by an increase in the adult LE of PLHIV between 2000-2002 and 2009-2012 of 22.9 and 20.0 years for women and men, respectively. Over the whole period of observation, the adult LE deficit associated with HIV decreased from 16.1 (95%-CI: 12.7-19.8) to 6.0 years (95%-CI: 4.1-7.8) among women, and from 16.0 (95%-CI: 12.1-19.9) to 2.8 years (95%-CI: 1.2-4.6) among men.

Conclusion

Population-wide LE increased substantially, largely driven by reductions in HIV related mortality. Women have gained more adult-life years than men since the introduction of ART, but the burden of HIV in terms of the life-years lost is still larger for women than it is for men.

Keywords: adult mortality, life expectancy, HIV, antiretroviral therapy (HIV), Uganda, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is now widely available in sub-Saharan Africa and there is strong evidence from clinical cohort studies in both developed and developing countries that ART has increased the life expectancy (LE) of HIV infected people in treatment programs [1, 2]. Extrapolating these estimates to all people living with HIV (PLHIV) is, however, problematic because facility data lack information on those who never make contact with the health system, or, are lost to follow up.

Here, we use data from a demographic surveillance site in southwestern Uganda covering a period ranging from the early 1990s to 2012. Repeated community-based testing for HIV ensures that the HIV status is known for most adults, which allows us to estimate adult LE by HIV status and show how these indices changed over time. Previous studies have used comparable data sources to describe mortality trends in terms of mortality rates or the probabilities of surviving adulthood [3–7], but detailed studies of population-level trends in (adult) LE are less common [8]. The appeal of LE as an index of mortality is that it is more sensitive to the shift in the age distribution of deaths, and therefore to the fact that ART prolongs the lives of PLHIV rather than eliminates AIDS deaths.

We describe the gains in adult life-years in terms of the adult LE of the population as a whole, and the adult LE by HIV status. In addition, we quantify the remaining or residual burden of HIV on adult mortality, and label this the adult LE deficit associated with HIV. A study from South Africa previously used verbal autopsy data and cause-deleted life tables for estimating the LE deficit [8]; we measure it as the difference between the LE of HIV negatives and the LE of the population as a whole [9].

Methods

Description of the Kyamulibwa General Population Cohort (GPC)

The GPC is a demographic surveillance site with around 23,000 current residents in 25 contiguous villages located in the Kalungu district (formerly part of Masaka) in rural south-western Uganda. The GPC covered 15 villages between 1989 and 1999 and has since been expanded with an additional 10 villages, including 4 small trading centres [10]. HIV prevalence in the study site was just under 7 percent prior to the rollout of ART in 2004, and increased to 9 percent in 2010 [10].

Because mortality may be under-reported during the start-up phase of the GPC, we report results for the period spanning 1991 to 2012. Data collection revolves around an annual census where information is gathered on changes to household membership (births, deaths, in and out migrations). The surveillance is complemented by village informants who record births and deaths in their registers and report on a monthly basis to the project office.

HIV testing and uptake of results

Medical surveys with HIV testing have been conducted on an annual basis since the inception of the GPC. Field workers contact all individuals aged 13 years and above who are resident for more than 3 months in the study villages, and obtain informed consent/assent before administering a study questionnaire and HIV testing. Until 2012, blood samples were drawn at home and transported for testing (two parallel ELISA tests) at the Medical Research Council (MRC) central laboratories in Entebbe. Results were made available within approximately one month of testing and participants could access their results at central counselling posts established in the study villages. Approximately 70% (range 61-89%) of the eligible residents that were contacted participated in the medical surveys between 1991 and 2012 [10]. Between 1989 and 1999, the proportion of those tested who accepted to receive their HIV results remained around 10%, despite an increase in the number of post-test counselling posts in 1993. The uptake of results increased to 36% in 2000/2001 when home delivery of results was introduced [11]. Following the introduction of ART in 2004, the uptake of test results increased to 46%, and to 56% in 2008 [12]. From 2012 onwards, rapid HIV testing with immediate return of test results on the same day was introduced per national guidelines [13], and the survey approach was also changed to invite participants for testing in a temporary hub in a central location in each village. The proportion of those contacted and accepting to test has not changed much, but the proportion of tested individuals who receive their result is now close to 99% (unpublished data). Participants who are diagnosed with HIV infection are immediately referred for care.

ART services availability

ART became available in the study site in 2004. Most PLHIV choose to go to the MRC study clinic for treatment, but ART is now also available in nearby public facilities. As per national guidelines, ART eligible individuals have three adherence counselling visits and a medical examination prior to treatment initiation. PLHIV are also required to identify a treatment adherence supporter. Following ART initiation, patients are seen at the clinic after 2 weeks, 4 weeks and then at 3-monthly intervals, or more frequently if there is a medical need. As for the other aspects of ART services provision, the study clinic closely follows the guidelines of the Ministry of Health for determining treatment eligibility (based on CD4 count thresholds), and in terms of treatment regimens. The study site may, however, be atypical in the sense that the research clinic is better resourced than most public health facilities in the area. This, for example, also facilitates the pro-active follow up of patients who miss their scheduled appointments. This is not limited to HIV, but also includes patients with other chronic conditions, including diabetes and hypertension. ART coverage in our study population has always been relatively high, and probably somewhat higher than in the rest of Uganda. For example, based on ART initiation at CD4 counts ≤200, the estimated coverage in the GPC in 2008 was 69% versus 53% for Uganda as a whole [12].

Life expectancy estimates

We estimate trends in three adult LE measures: (i) the adult LE of the general population, (ii) the adult LE by HIV status (positive, negative and unknown), and (iii) the adult LE deficit associated with HIV. All estimates are disaggregated by sex.

The adult LE is defined as the number of additional years that a 15-year old can expect to live under the mortality rates that prevail in a particular year or period. It is a synthetic and age-standardized measure of mortality, and accounts for the fact that ART prolongs the lives of PLHIV rather than avoids AIDS associated deaths altogether. Using continuous-time survival analysis methods, the adult LE is computed as the area under the Kaplan-Meier product-limit survivor curve between ages 15 and 100. As done elsewhere, we impose an upper age limit because the contribution of the years lived by centenarians to the overall LE is often trivial but could be biased by age over-reporting [8]. Percentile-based confidence bounds around LE estimates are obtained via bootstrapping with 1,000 replications. Adult LE estimates are presented for groups of three calendar years because the population is relatively small for single year estimates by sex and HIV status.

The adult LE deficit quantifies the effect of AIDS-associted mortality on the population-wide LE. It treats the LE of HIV negatives as a benchmark of achievable LE and subtracts the observed LE for the population as a whole. In other words, it is the average or per person number of adult life-years lost to HIV. The adult LE deficit depends on the epidemic magnitude and maturity as well as the mitigating effects of ART scale-up on HIV related mortality. Non-HIV mortality will moderate the LE deficit as fewer life-years are lost to HIV in a population where the death rates from other causes are high. Younger ages at HIV infection and death will widen the LE gap.

The age at infection and the presence of competing mortality risks are important considerations for understanding gender differences in the adult LE trends and deficit because women have lower non-HIV related mortality in adulthood and they are usually infected at a younger age than men [14–16]. Elsewhere, we provide greater detail on factors that invalidate the interpretation of the difference between the population-level LE and the LE of the HIV negatives as the LE deficit attributable to HIV [9]. This includes correlated mortality risks (e.g., PLHIV have higher mortality rates from causes other than HIV), and spill-over effects that may result from increased investments in HIV services, or, the utilization of these services (e.g., PLHIV experience larger mortality reductions from other causes because of their greater engagement with health services) [8, 17].

We complement our analyses of adult LE trends with an age decomposition of LE differences to better understand the contribution of mortality differences in each age group to the overall LE difference using a method described by Arriaga [18]. We conduct the age decomposition for two quantities: (i) the overall LE gains that have been made compared to the pre-ART period, and (ii) the current adult LE deficit.

HIV status imputation procedures

In order to allocate exposure time to the respective HIV status categories we classify time prior to the first recorded HIV test as HIV status unknown. Failure to do so introduces downward bias in mortality estimates because survivors would be the only ones contributing person-time prior to the first test. Time following an HIV positive test remains positive until censoring or death. Any time between two negative tests is counted as negative irrespective of the interval between tests. The time following the last negative test is considered negative for a duration corresponding to the probability that 95% of their age group remains uninfected given the sex-specific HIV incidence rates or death, whichever occurs first.

Results

In total, 27,925 adults aged 15 years and above have ever been resident in the GPC between 1991 and 2012 and included in the analysis (Table 1). A little over half (53.8%) of all adults are women and they also contribute the majority of persons-years of exposure (52.4%). Because the HIV medical survey with HIV testing is repeated each year, the HIV status information in the dataset is fairly complete (83.2% of the person-years lived). The average person-year prevalence –defined as the HIV positive person years divided by the HIV positive plus HIV negative person years– is 6.8%. A total of 2,359 deaths occurred in the entire study period (1991-2012). Over half (57.3%) of the deaths occurred after the age of 45 years. The proportion of adults who died was highest among PLHIV (29.5%), followed by those with HIV negative status (5.5%). Among people with unknown HIV status, 3.1% died (Table 1).

Table 1. Study site characteristics, and death rates by age, sex, HIV status and period (Kyamulibwa GPC, 1991-2012).

| Variable | Individuals a | Person years of observation (PYOs) | Total number of deaths | Proportion who died (row %) | Adult mortality rates (per 1,000) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ART: 1991–2003 Rate (95% CI) | ART: 2004–2012 Rate (95% CI) | |||||

| All | 27,925 | 159,638 | 2359 | 8.4 | 17.8 (16.9–18.8) | 11.9 (11.2–12.7) |

| Males | ||||||

| 15–19 yrs | 7071 | 19,043 | 44 | 0.6 | 3.3 (2.3–4.7) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) |

| 20–24 yrs | 4280 | 10,228 | 46 | 1.1 | 5.0 (3.5–7.3) | 3.9 (2.5–6.1) |

| 25–34 yrs | 3858 | 15,284 | 198 | 5.1 | 18.6 (15.8–21.8) | 7.1 (5.4–9.3) |

| 35–44 yrs | 2521 | 11,326 | 173 | 6.9 | 21.1 (17.5–25.5) | 10.4 (8.1–13.3) |

| 45+ yrs | 2579 | 20,106 | 729 | 28.3 | 36.7 (33.1–40.7) | 35.8 (32.3–39.7) |

| Females | ||||||

| 15–19 yrs | 7966 | 18,421 | 38 | 0.5 | 2.6 (1.8–3.9) | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) |

| 20–24 yrs | 5088 | 11,312 | 103 | 2.0 | 13.1 (10.4–16.4) | 4.9 (3.4–7.2) |

| 25–34 yrs | 4410 | 17,714 | 261 | 5.9 | 21.7 (18.8–25.1) | 8.3 (6.6–10.4) |

| 35–44 yrs | 2775 | 12,727 | 145 | 5.2 | 15.0 (12.1–18.5) | 8.4 (6.5–10.8) |

| 45+ yrs | 2969 | 23,477 | 622 | 20.9 | 30.8 (27.6–34.2) | 22.8 (20.3–25.6) |

| HIV status | ||||||

| HIV negative | 21,627 | 123,720 | 1182 | 5.5 | 10.2 (9.4–11.1) | 8.9 (8.2–9.7) |

| HIV positive | 2279 | 9078 | 672 | 29.5 | 117.2(107.2–128.2) | 39.1 (34.0–44.9) |

| HIV unknown | 16,265 | 26,840 | 505 | 3.1 | 21.2 (18.9–23.8) | 16.2 (14.1–18.5) |

Number of unique individuals observed in each age group or HIV status category. Individuals can contribute to more than one category as they age or their HIV status changes during follow up.

Table 1 also gives a first indication of the changes in adult mortality that have taken place following the introduction of ART services in the study site. Overall adult mortality rates have declined from 17.8 per 1,000 person-years (95%-CI: 16.9–18.8) in the pre-ART era to 11.9 per 1,000 (95%-CI: 11.2–12.7) for the years following the introduction of ART. The most pronounced declines in mortality have been registered among PLHIV where the death rates declined from 117.2 per 1,000 (95%-CI: 107.2–128.2) to 39.1 per 1,000 (95%-CI: 34.0–44.9). Detailed trends in mortality rates by HIV status have been published elsewhere [3].

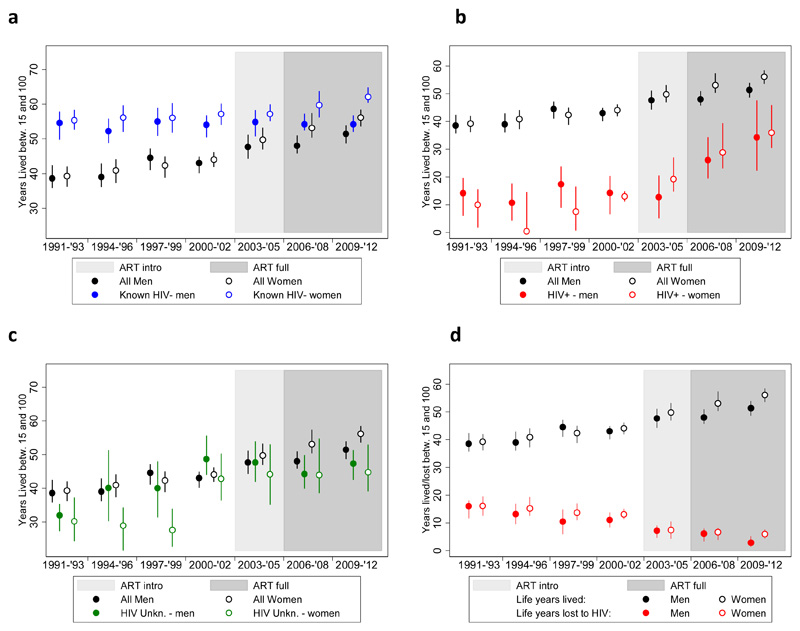

The mortality rate reductions have also translated in important gains in adult LE, as illustrated in Figure 1 (a-c). Detailed estimates along with their 95% confidence interval are presented in Appendix 1. Overall female LE increased from 39.3 years (95%-CI: 35.9-42.8) in 1991-1993 to 56.1 (95%-CI: 54.0-58.5) in 2009-2012, for a total gain of 16.8 years. The LE for men rose from 38.6 (95%-CI: 35.4-42.1) to 51.4 years (95%-CI: 49.2-53.7) over the same period, for a total gain of 12.8 years. Among women, 82.1% of these gains were achieved after 2000, and 38.1% after 2005. The corresponding figures for men are 53.1% and 29.7%, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a-d): Adult LE trends with 95%-confidence intervals by sex, period and HIV status (Kyumalibwa GPC, 1991-2012)

The adult LE of HIV negative women increased by 6.7 years between 1991-1993 and 2010-2012; from 55.4 (95%-CI: 51.7-59.4) to 62.1 (95%-CI: 59.8-64.4). In contrast, the LE of HIV negative men remained around 54 years: 54.6 years in 1991-1993 (95%-CI: 50.2-59.1) and 54.2 years in 2009-2012 (95%-CI: 51.9-56.8) (Figure 1, panel a).

The LE gain among PLHIV is pronounced for both sexes (Figure 1, panel b). Before the availability of ART at the local health facility, the adult LE of HIV positive women and men hovered around or just above 10 years. Between 2000-2002 and 2009-2012 the adult LE increased by 22.9 years for women (from 13.0 (95%-CI: 10.9 - 15.4) to 35.9 years (95%-CI: 30.8 - 46.0)) and by 20.0 years for men (from 14.3 (95%-CI: 6.6 -20.6) to 34.3 (95%-CI: 18.3 - 47.3) years). As was the case for the overall LE and the LE for HIV negatives, HIV positive women have gained more life-years in the past decade than HIV positive men, but the differences are smaller.

The trend in the LE of adults with an unknown HIV status is similar to that of the population as a whole, but LE estimates are on average a little lower (Figure 1, panel c). This suggests that PLHIV are over-represented among those whose HIV status is unknown.

The adult LE deficit associated with HIV is presented in panel d of Figure 1. In the early 1990s, the average number of life-years lost still amounted to 16.1 years (95%-CI: 12.7 - 19.8) for women and 16.0 years (95%-CI: 12.1 - 19.9) for men. By 2009-2012, the LE deficit had declined to 6.0 years (95%-CI: 4.1 - 7.8) for women and to 2.8 years (95%-CI: 1.2 - 4.6) for men. Worth noting is that the LE deficit started declining before introduction of treatment: by 2000-2002, the LE deficit had already declined to 13.1 years (95%-CI: 10.3 - 15.9) among women and to 11.0 years (95%-CI: 8.2 - 14.2) among men.

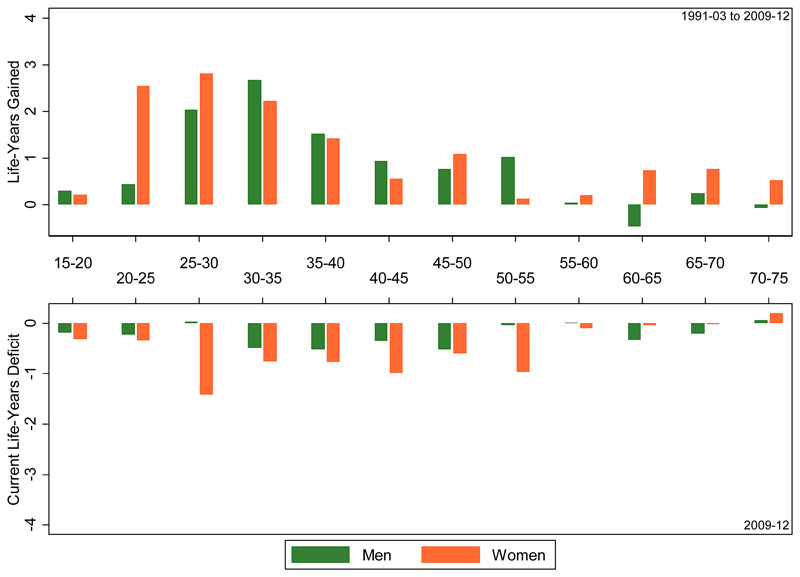

The upper panel of Figure 2 illustrates the contributions of each age group to the adult LE gains that have been made between 1991-2002 (the pre-ART period) and 2009-2012 (the most recent period with data). The lowers panel depicts the age-group contributions to the LE deficit for 2009-2012. The total LE gain that is decomposed in the upper panel amounts to 13.2 years for women and 8.8 year for men, and illustrates that mortality reductions in women and men of reproductive age have contributed most to the LE gains that have been made compared to the pre-ART years. The age profile of these contributions to the overall adult LE is younger for women than for men, and that is indeed what one would expect given their earlier age at infection [15]. The age-group contributions to the current adult LE deficit associated with HIV (lower panel) are more evenly spread across the adult age range, and that is the case for both women and men.

Figure 2.

age group contributions to the adult life-years gained between 1991-2001 and 2009-2012 (upper panel), and the adult LE deficit associated with HIV in 2009-2012 (lower panel), Kyamulibwa GPC

Discussion

This population in rural Uganda has experienced large mortality reductions between 1991 and 2012, amounting to an adult LE gain of 17 years for women and 13 years for men. The gains in adult LE are largely driven by reductions in HIV related mortality; a finding that is supported by the LE trends among HIV positive and HIV negative individuals: among PLHIV, the LE rose by 20 and 23 years among men and women. Over the same period, the adult LE among HIV negatives improved by 7 years for women and did not change for men.

The large declines in HIV-associated mortality are also captured by the difference between the adult LE of the HIV negative population and the LE of the population as a whole. In the early 1990s, this LE deficit was still 16 years or more for both sexes, but has now shrunk to 6 years for women and 3 years for men. However, not all of the decline in the LE deficit is driven by the expansion of ART programs and could also result from historical declines in HIV incidence [9]. Improvements in the screening for, and management of opportunistic infections may have contributed to the declining mortality among PLHIV prior to treatment availability, but the effect of earlier declines in HIV incidence are probably more important. Mbulaiteye and colleagues reported a decline in HIV incidence in the study population in the early 1990s [19], which is expected to have caused a decline in mortality around 10 years later [16]. This explanation is corroborated by our results because the adult LE deficit started declining before the introduction of ART in 2004. Incidentally, differences in the timing of the epidemic peak are also likely to explain the apparent discrepancy with a prior study on adult LE trends following the expansion of ART programs in KwaZulu-Natal [8]. HIV prevalence is three times as high in the South African study site, and one might therefore expect that the expansion of treatment programs made a larger difference for adult mortality. However, Bor and colleagues estimated that adult LE increased by 11.3 years between 2004 and 2011, which is comparable to the LE gains recorded in this study population, even though its HIV prevalence is much lower. In the Ugandan case, declining mortality due to historical declines in HIV incidence augments the LE gains achieved by the expansion of treatment. In South African the HIV epidemic peaked later and adult LE would have continued to decline in the absence of treatment [8, 9].

Sex or gender differences in the life-years gained and lost offer a novel perspective on an ongoing debate about equitable access to services [20]. The adult life-years gained by PLHIV is 3 years higher for women than it is for men. As suggested elsewhere, differences in the engagement with health services could explain some of the gender differences in the LE trends of PLHIV [21]. However, this phenomenon is also related to variability in the age of infection and to differences in the background mortality of men and women [9]. Women, for example, are usually infected at younger ages than men [14–16], and have lower non-HIV mortality in adulthood. In the absence of treatment, a female HIV infection and death will therefore incur a larger loss in LE. Conversely, preventing a female HIV death will entail a larger gain in life-years.

Despite the larger gains in adult LE, women still have a larger LE deficit than men, which suggest that the disproportionate burden of HIV on women persists. The matter is probably more complex than is presented here, however, as the expansion of HIV services may produce spill-over effects with possibly different repercussions for male and female mortality from causes that are unrelated to HIV (e.g., via the strengthening of maternal health services provision) [17].

This study pertains to a relatively small population that has been under active surveillance for the last 25 years, and for these reasons we cannot claim that it is representative for the country or even rural areas within the country. However, with the exception of the community outreach with HIV testing, the medical services provided to this population closely adhere to the national guidelines and are indicative of their potential impact. The results from this study also provide an empirical counterpoint for estimates that rely more heavily on modelling. The WHO, for example, reports changes in Uganda's national-level LE at age 15 between 1990-2012 of 3 years (from 46 to 49) and 6 years (from 42 to 48) for women and men, respectively [22]. Our results from south-western Uganda are indicative of much larger mortality reductions and corresponding increases in adult LE that are at least twice as high. Bor and colleagues noted equally large differences between a demographic surveillance site in KwaZulu-Natal and national-level trends for South Africa [8], which suggests that the WHO may have underestimated the LE gains following the expansion of treatment programs in populations with generalized epidemics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research is jointly funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement (G0700837) and benefited from two grants to the ALPHA Network (http://alpha.lshtm.ac.uk/) from Wellcome Trust (085477/Z/08/Z), and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF-OPP1082114). KB receives support from the MRC UK and DFID (MRC grant number G0700837). We also like to thank the residents of the study area and the entire study team.

References

- 1.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372:293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills EJ, Bakanda C, Birungi J, Chan K, Ford N, Cooper CL, et al. Life expectancy of persons receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries: a cohort analysis from Uganda. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:209–216. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasamba I, Baisley K, Mayanja BN, Maher D, Grosskurth H. The impact of antiretroviral treatment on mortality trends of HIV-positive adults in rural Uganda: a longitudinal population-based study, 1999-2009. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:e66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reniers G, Slaymaker E, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Nyamukapa C, Crampin AC, Herbst K, et al. Mortality trends in the era of antiretroviral therapy: evidence from the Network for Analysing Longitudinal Population based HIV/AIDS data on Africa (ALPHA) AIDS. 2014;28(Suppl 4):S533–542. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slaymaker E, Todd J, Marston M, Calvert C, Michael D, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, et al. How have ART treatment programmes changed the patterns of excess mortality in people living with HIV? Estimates from four countries in East and Southern Africa. Global Health Action. 2014;7 doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.22789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Floyd S, Marston M, Baisley K, Wringe A, Herbst K, Chihana M, et al. The effect of antiretroviral therapy provision on all-cause, AIDS and non-AIDS mortality at the population level--a comparative analysis of data from four settings in Southern and East Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:e84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jahn A, Floyd S, Crampin AC, Mwaungulu F, Mvula H, Munthali F, et al. Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. The Lancet. 2008;371:1603–1611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell ML, Barnighausen T. Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science. 2013;339:961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1230413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reniers G, Eaton J, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kabudula C, Crampin A, Herbst K, et al. The Impact of Antiretroviral Therapy on Adult Life Expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa; Annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asiki G, Murphy G, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Seeley J, Nsubuga RN, Karabarinde A, et al. The general population cohort in rural south-western Uganda: a platform for communicable and non-communicable disease studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:129–141. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff B, Nyanzi B, Katongole G, Ssesanga D, Ruberantwari A, Whitworth J. Evaluation of a home-based voluntary counselling and testing intervention in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20:109–116. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazooba P, Kasamba I, Baisley K, Mayanja BN, Maher D. Access to, and uptake of, antiretroviral therapy in a developing country with high HIV prevalence: a population-based cohort study in rural Uganda, 2004-2008. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:e49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downing RG, Otten RA, Marum E, Biryahwaho B, Alwano-Edyegu MG, Sempala SD, et al. Optimizing the delivery of HIV counseling and testing services: the Uganda experience using rapid HIV antibody test algorithms. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1998;18:384–388. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199808010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glynn JR, Carael M, Auvert B, Kahindo M, Chege J, Musonda R, et al. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S51–60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Mason PR, Zhuwau T, Caraël M, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet. 2002;359:1896–1903. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todd J, Glynn JR, Marston M, Lutalo T, Biraro S, Mwita W, et al. Time from HIV seroconversion to death: a collaborative analysis of eight studies in six low and middle-income countries before highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21:S55–S63. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000299411.75269.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grepin KA. HIV donor funding has both boosted and curbed the delivery of different non-HIV health services in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1406–1414. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arriaga EE. Measuring and explaining the change in life expectancies. Demography. 1984;21:83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mbulaiteye S, Mahe C, Whitworth J, Ruberantwari A, Nakiyingi J, Ojwiya A, et al. Declining HIV-1 incidence and associated prevalence over 10 years in a rural population in south-west Uganda: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2002;360:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johannessen A. Are men the losers of the antiretroviral treatment scale-up? AIDS. 2011;25:1225–1226. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834403b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braitstein P, Boulle A, Nash D, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Laurent C, et al. Gender and the use of antiretroviral treatment in resource-constrained settings: findings from a multicenter collaboration. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:47–55. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organisation. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. World Health Organisation; 2012. Trends of life expectancy at age 15years in Uganda (1990-2012) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.