Abstract

PARP inhibitors (PARPi) are approved drugs for platinum-sensitive, high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) and for breast (BC), prostate, and pancreatic cancers (PaC) harboring genetic alterations impairing homologous recombination repair (HRR). Detection of nuclear RAD51 foci in tumor cells is a marker of HRR functionality, and we previously established a test to detect RAD51 nuclear foci. Here, we aimed to validate the RAD51 score cut-off of 10% and compare the performance of this test to other HRR deficiency (HRD) detection methods. Laboratory models from BRCA1/BRCA2-associated BC, HGSOC and PaC were developed and evaluated for their response to PARPi and cisplatin. HRD in these models and patient samples was evaluated by DNA sequencing of HRR genes, genomic HRD tests, and RAD51 foci detection. We established PDX models from BC (n=103), HGSOC (n=4) and PaC (n=2) that recapitulated patient HRD status and treatment response. The RAD51 test showed higher accuracy than HRR gene mutations and genomic HRD analysis for predicting PARPi response (95%, 67%, and 71%, respectively). RAD51 detection captured dynamic changes in HRR status upon acquisition of PARPi resistance. The accuracy of the RAD51 test was similar to HRR gene mutations for predicting platinum response. Thus, the pre-defined RAD51 score cut-off was validated, and the high predictive value of the RAD51 test in preclinical models was confirmed. These results collectively support pursuing clinical assessment of the RAD51 test in patient samples from randomized trials testing PARPi or platinum-based therapies.

Keywords: RAD51, breast cancer, PARP inhibitor, platinum, HRD

Introduction

PARP inhibitors (PARPi) have been approved for the treatment of ovarian (HGSOC), breast (BC), prostate and pancreatic cancers (PaC).(1) In these settings, biomarkers such as sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy and homologous recombination repair (HRR) deficiency (HRD) tests enable patient selection for these targeted therapies. Amongst HRD tests, pathogenic variants in genes in the HRR pathway or genomic HRD tests -scars or signatures- are the most commonly used.(2–4)

Overall, it is estimated that over 17% of all cancers harbor genetic alterations in the HRR pathway,(5) albeit only those that are biallelic lead to HRD.(2,3) Genomic scars or signatures have shown sensitivity in identifying tumors with an HRD phenotype.(4,6,7) In patients with HGSOC, current genomic scars are informative for predicting the magnitude of benefit from PARPi as maintenance therapy after response to platinum-based chemotherapy.(8) Nevertheless, genomic HRD tests may fail to provide an accurate functional status of HRR or predict the benefit from PARPi and other DNA damaging agents in other settings. Also, these assays carry some challenges for their implementation in clinical practice, since they are technically complex, may require frozen samples, and carry a high cost. In this regard, some commercially-available panels based on targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) have incorporated measures of HRD based on surrogate genomic scars.(7) While the cost of targeted NGS testing is significantly less than for whole exome sequencing (WES), it still represents a barrier for many patients and healthcare systems. In summary, genomic testing presents technical and logistical challenges to reach large numbers of cancer patients. In comparison, histology-based tests are technically less complex than NGS tests, require less amount of sample, are less costly and can capture tumor heterogeneity and changes in HRR status during tumor evolution. As such, previous evidence has shown that detection of the downstream HRR protein RAD51 nuclear foci is a marker of HRR functionality.(9–11)

We and others have adopted preclinical models that recapitulate the patient’s disease and help investigate biomarkers of sensitivity to targeted therapies, including cell lines,(12) patient-derived xenografts (PDX) models(13–15) and three-dimensional patient-derived tumor cell cultures (PDC).(16–19) Using PDX, we developed an immunofluorescence-based test to detect RAD51 nuclear foci in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples.(14,15) The clinical utility of the assay has been tested in early triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) and in castration resistant prostate cancer treated with the PARPi olaparib.(20–22) This RAD51 assay is able to capture: 1) HRD in tumors with BRCA1, BRCA2 or PALB2 mutations, or in tumors with epigenetic silencing of an HRR gene, i.e. in BRCA1 or RAD51C; or 2) HRR proficiency (HRP) in tumors with previous history of HRD that have restored HRR as a mechanism of drug resistance.(14,15)

In summary, there is a clear need to provide access to HRD functional tests available for routine clinical diagnostics to identify patients eligible to targeted therapies. In the current work, we tested the accuracy of the RAD51 test in comparison with mutations in HRR genes or genomic HRD tests to predict response to PARPi, with further validation in clinical samples. We also conducted an analysis of the predictive value of the RAD51 assay for predicting response to platinum. The overarching aim was to provide preclinical analytical validation of the RAD51 assay to support the use of the test in clinical practice. Additionally, we described potential mechanisms of resistance to PARPi, thus cataloguing the PDX models for further experimental studies.

Materials and Methods

Generation of PDX models and in vivo treatment experiments

Fresh tumor samples from patients with HRR-related breast (triple negative, luminal B or HER2-positive), HGSOC or pancreatic cancer were collected for diagnostic and for implantation into nude mice under an institutional review board (IRB)-approved protocol. The human biological samples were sourced ethically and their research use was in accord with the terms of the written informed consents under an IRB/EC approved protocol. Experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of Animal Experimentation of the Vall d’Hebron Research Institute. All animal studies were ethically reviewed and carried out in accordance with European Directive 2010/63/EEC and the GSK Policy on the Care, Welfare and Treatment of Animals. The PARPi response criteria was based on the percentage of tumor volume change. Responders included models that exhibited Complete Response (CR), Partial Response (PR) and Stable Disease (SD) and Non-Responders included Progressive Disease (PD). For further details, see Supplementary Material.

DNA sequencing and genomic HRD by scars or signatures

DNA was extracted from PDX samples using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). For further details, see Supplemental Material. Three genomic scar/signature assays were performed: the Myriad’s myChoiceⓇ HRD test carried out at Myriad Genetics on DNA extracted from a subset of Xentech’s PDX (using NucleoBond AXG100 kit, Macherey- Nagel), HRDetect and the Genomic Instability Score (GIS: levels of allelic imbalance, loss off heterozygosity, number of large-scale transitions) performed at Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute on DNA extracted from a subset of VHIO’s PDX as described in(6) and(23), respectively.

BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation

BRCA1 promoter methylation was measured using methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MS-MLPA; MRC Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Two of the xenografts generated in CRUK/UCAM (STG139 and STG201) had been previously tested using reduced-representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS)(16) and further validated using MS-MLPA. Positive controls of BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation were used (T127 and/162).(24)

BRCA1 mRNA expression

RNA was extracted from PDX samples (15–30 mg) by using the PerfectPure RNA Tissue kit (five Prime). The purity and integrity were assessed by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system, and RNA-seq was performed in Illumina HiSeq 4000 (Illumina). Log2 transformation was used for data analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining and scoring

The following primary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence: rabbit anti-RAD51 (Abcam ab133534, 1:1000), mouse anti-geminin (NovoCastra NCL-L, 1:100 in PDX samples, 1:60 in patient samples), rabbit anti-geminin (ProteinTech 10802-1-AP, 1:400), mouse anti-BRCA1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-6954, 1:50), mouse anti-BRCA1 (Abcam ab16780, 1:200), mouse anti-phospho-H2AX (Millipore #05-636, 1:200). Goat anti-rabbit Alexa fluor 568 (Invitrogen; 1:500), goat anti-mouse Alexa fluor 488 (Invitrogen; 1:500), donkey anti-mouse Alexa fluor 568 (Invitrogen; 1:500), and goat anti-rabbit Alexa fluor 488 (Invitrogen; 1:500) were used as secondary antibodies. The immunofluorescence was performed as described in (15).

Biomarkers were quantified on FFPE PDX, PDC or patient tumor samples by scoring the percentage of geminin-positive cells with 5 or more nuclear foci of any size(15). Geminin is a master regulator of cell-cycle progression that enables to mark for S/G2-cell cycle phase.(25) Scoring was performed onto life images using a 60x-immersion oil lens. One hundred geminin-positive cells from at least three representative areas of each sample were analyzed. Samples with low γH2AX (< 25% of geminin-positive cells with γH2AX foci) or with < 40 geminin-positive cells were not included in the analyses, due to insufficient endogenous DNA damage or tumor cells in the S/G2-phase of the cell cycle, respectively. The mouse anti-geminin antibodies used in this study are human-specific so that they did not cross-react with mouse stroma.

PDC ex vivo cultures

Patient-derived tumor cells were isolated from 24 PDX through combination of mechanic disruption and enzymatic disaggregation following a previously described protocol.(16) Briefly, PDX tumors not bigger that 500 mm3 were freshly collected in DMEM/F12/HEPES (GIBCO) after surgery resection, minced using sterile scalpels and dissociated for a maximum of 90 minutes in DMEM/F12/HEPES (GIBCO), 1 mg/ml collagenase (Roche), 100 u/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich), 5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 µg/ml insulin and 50 µg/ml gentamycin (GIBCO). This was followed by further dissociation using 0.05% trypsin (GIBCO),1 u/ml dispase (StemCell technologies) and 1 mg/ml DNase (Sigma-Aldrich). Red blood cell lysis was done by washing the cell pellet with 1X Red Blood Cell (RBC) Lysis Buffer containing ammonium chloride (Invitrogene). Then, cells were resuspended RPMI 1640 with GlutaMAX medium (Gibco) supplemented with 2% of heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1 ul/ml ROCK inhibitor, 20 ul/ml B27, 0.02 ul/ml EFG, 0.2 ul/ml FGF10, 0.2 ul/ml FGF2. To obtain FFPE blocks from PDC cultures, cells were seeded at 2x105 cells/ml in 6-well plates (BD Biosciences). After 24 hours, PDC were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 2.5 µM olaparib and incubated at 37ºC in 5% of CO2. Vehicle and olaparib-treated cells were harvested, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4ºC followed by 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin.

For half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) analysis, cells (2 × 103 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates (BD Bioscience) and were treated the following day with different concentrations of olaparib for 14 days. The treatments and media were refreshed every 2 days. Olaparib-sensitive and -resistant PDX were included in every batch of analysis. Cell viability was quantified with CellTiter Glo® Luminiscent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) in an Infinite M200 PRO plate reader (TEKAN). Values at day 14 were subtracted with the mean background signal (no cells), normalized with values at day 0, relativized to controls (not treated cells) and plotted as the percentage inhibition against the log concentration of olaparib. IC50s values (half maximal inhibitory concentration) were calculated performing a nonlinear regression. Each experiment was repeated twice with two technical replicates.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism version 7.0 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Bars represent the median of at least two technical replicates, unless otherwise stated. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality of data distributions. If the null hypothesis of normal distribution was not rejected, statistical tests were performed using paired and unpaired two-tailed t-test (for two groups comparison of PDC and/or patient samples, and HRD score by Myriad in PDX). Otherwise, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney or Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used (for two groups comparison of RAD51 score and HRDetect score in PDX). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC) were calculated to estimate the prediction capacity of Myriad’s myChoiceⓇ HRD test and RAD51 scores to PARPi response. For AUC comparison, a two-sided bootstrap test was used by means of statistical package pROC in R software. Additionally, sensitivity, specificity, positive (PPV), and negative (NPV) predictive values were calculated using the pre-established cut-off. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated to estimate the agreement of RAD51 status between PDX and patient samples. To calculate the association between RAD51 score in PDX and in PDC, and between RAD51 in PDX and patient samples, a linear regression model was fitted to estimate the R-squared with CI 95%.

Sample size

The main goal of this work is to analyze in a cohort of PDX models whether the accuracy to predict response to PARPi is different using mutations in HRR genes, genomic HRD tests or the RAD51 assay. Our PDX panel (see below) is enriched with models having HRD, as >50% of models derived from patients with a germline HRR gene alteration. In addition, it is expected to find >70% of HRD-positive tumors by genomic scars since the vast majority of the PDX tumors are TNBCs according to immunohistochemistry characterization of estrogen and progesterone receptor and the HER2 status.(26) The accuracy to predict PARPi response using HRR-gene mutations is expected to be 70% while the accuracy of RAD51 assay is estimated to be 92%.(27,28) In order to detect such a difference using a 1/2.5 ratio with at least 90% power and two-sided type I error of 0.05, at least 41 PDX samples with HRR-gene mutations and 103 PDX samples with RAD51 assay information are required. Sample size calculation is based on exact binominal distribution. Assuming that not all HRR-gene tests and RAD51 assays will provide informative results, an attrition rate of 5% is estimated, and consequently, a total of 109 PDX samples are needed.

Results

PARPi antitumor activity in a series of PDX

One hundred and nine patient-derived models from three BRCA-associated cancers were established, namely from breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancers, both from primary and metastatic tumors (Figure 1; Table S1).(14,15) The antitumor activity of the PARPi olaparib or niraparib was assessed in 96 PDX models derived from 65 TNBC, 24 hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer (BC), 1 HER2-positive (HER2+) BC, 4 HGSOC and 2 PaC patients (Table S1). Upon PARPi treatment in vivo, the best response according to modified RECIST criteria was: complete response (CR) in 12, partial response (PR) in 10 and stable disease (SD) in 7 PDX models, totaling 29/109 sensitive models. Sixty-seven PDX models were PARPi-resistant (PD, progressive disease, as best response) (Figure 2A). Additional 13 resistant models were generated from nine PARPi-sensitive PDX after prolonged exposure and steep progression to olaparib. Time to progression was not observed to be associated with the type of HRR alteration (Figure S1A). In total, 80/109 models were resistant to PARPi.

Figure 1. Establishing a biobank of patient-derived laboratory models.

Study design depicting the generation of PDX from BC, HGSOC and PaC, and PDC from BC. PDX (n=109) were established from patient tumor samples and PDC (n=14) were generated from the corresponding PDX.

Figure 2. Antitumor activity of PARPi in PDX.

A) Waterfall plot showing the best response to the PARPi olaparib or niraparib in 109 PDX, as percentage of tumor volume change, compared to the tumor volume on day 1. +20%, −30%, -95% are marked by dotted lines to indicate the range of PD, SD, PR, CR, respectively. The legend summarizes the RAD51 score (A), the genomic HRD score (B) (based on Myriad myChoice® or HRDetect) and (C) the tumor type. B) Pie charts indicating the distribution of HRR functional status and HRR alterations in 96 PDX (excluding models of acquired resistance). C) Pie charts indicating the distribution of PARPi resistance mechanisms in 69 HRR-altered tumors (including models of acquired resistance).

Identification of HRR alterations in PDX and association with PARPi response

Forty out of 96 (42%) PDX models did not present alterations in HRR genes and did not respond to PARPi treatment (Figure 2A,B). The remaining 56 models harbored alterations in HRR genes and presented differential responses to PARPi (Figure 2A,B). Pathogenic biallelic variants in BRCA1 were identified in 25 models (9 sensitive and 16 resistant) and BRCA2 pathogenic biallelic variants were detected in 13 models (10 sensitive and 3 resistant). BRCA1 epigenetic silencing, evaluated by lack of BRCA1 transcript by RNA-sequencing (cut-off ≤1 tmp) and lack of functional BRCA1 nuclear foci by immunofluorescence (IF; cut-off ≤10%) was found in 13 PDX (6 sensitive and 7 resistant). We identified biallelic frameshift mutations in PALB2 in three PARPi-sensitive models (PDX093, T298, ST897) and homozygous loss of the gene encoding the RAD51 paralog XRCC3 in a PARPi-sensitive PDX (HBCx14, labelled as “other HRR genes” in Figure 2A,B; Table S1). Taken together, our analyses identified that all the PARPi-responsive PDX models in the cohort had at least one alteration in the HRR genes BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 or XRCC3.

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) also revealed mutations that could explain mechanisms of resistance to PARPi in HRR-altered PDX (Figure 2C). Three models (PDX093OR6, PDX332 and PDX405OR100) harbored mutations in PALB2 or BRCA2 that were compatible with HRR gene reversions. Three additional BRCA1-mutant models presented alterations in the 53BP1-shieldin pathway, which have been shown to confer PARPi resistance (HBCx28, PDX127, PDX230OR1) (Table S1).(29–31) Interestingly, BRCA1 nuclear foci (cut-off >10%) were detected in 7 out of 25 BRCA1-mutant models, underscoring the high prevalence of re-expression of BRCA1 proteins lacking relevant domains in this panel, which is considered hypomorphic (Table S1). The presence of BRCA1 proteins lacking relevant domains in tumors with mutations in the RING, exon 11 or the BRCT domains of BRCA1 has been associated with resistance to PARPi (Figure 2C; Table S1).(32–34) In addition, BRCA1 nuclear foci were detected in 4 out of 11 BRCA1-low models upon acquisition of PARPi-resistance. Finally, three models (PDX124OR, PDX377OR1 and PDX377OR2) were PARPi-resistant without substantial of HRR restoration, according to their levels of BRCA1 and RAD51 nuclear foci when compared to their sensitive counterparts (named as “RAD51-independent” in Figure 2C). Altogether, our genomics, transcriptomics and BRCA1 protein foci analyses identified likely mechanisms of PARPi resistance in half of the HRR-altered, non-responsive models.

We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for PARPi response of HRR gene mutations or low BRCA1 expression (mRNA or nuclear foci, Table 1). These two HRD biomarkers showed similar accuracy (67% and 69%, respectively). In summary, our data confirmed that genetic and epigenetic alterations in HRR genes had limited accuracy predicting PARPi sensitivity.

Table 1. Test performance values for the indicated HRD biomarkers predicting PARPi response.

| Biomarkers of PARPi response | BRCA1/2, PALB2 mutations (n=109) | Low BRCA1 mRNA/foci (n=108) | Genomic HRD score (≥42) (n=41) | RAD51 score (≤10) (n=109) | Platinum response (n=56) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 76% | 38% | 100% | 90% | 73% |

| Specificity | 64% | 81% | 59% | 98% | 49% |

| PPV | 43% | 42% | 50% | 93% | 26% |

| NPV | 88% | 78% | 100% | 96% | 88% |

| Accuracy | 67% | 69% | 71% | 95% | 54% |

Quantification of genomic HRD in PDX and association with PARPi response

We evaluated the association between the genomic scar Myriad myChoice® HRD and PARPi response. Genomic HRD was quantified in a subset of 41 PDX models, 11 of which harbored a mutation in BRCA1/2 or PALB2. All the HRR-gene mutated samples were HRD-positive (cut-off≥42) (Figure S1B, Table S1). In addition, the test identified as HRD-positive nine tumors lacking BRCA1 expression (BRCA1-low) of which two were known to previously harbor BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation (named as “WT with history of HRD” in Fig. S1B)(35). All PARPi-sensitive PDX were HRD positive and the median of HRD values was higher in PARPi sensitive than in PARPi resistant models (Figure 3A, median of 67 vs 36, p=0.0002). Nonetheless, 12 out of 29 PARPi-resistant PDX were also HRD positive. Accordingly, the genomic HRD test showed a limited accuracy for predicting PARPi responses (71%), similar to HRR-gene mutations or assessment of BRCA1 mRNA expression or BRCA1 nuclear foci (Table 1).

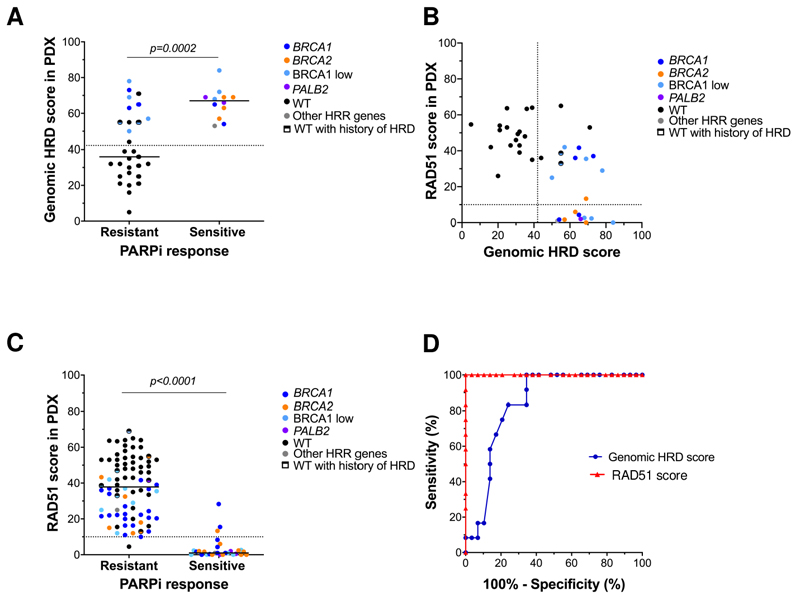

Figure 3. RAD51 functional assay predicts PARPi response in PDX.

A) Genomic HRD score in PARPi-sensitive and resistant models (n=41), measured with Myriad myChoice®. B) Comparison of the RAD51 score with the genomic HRD score as in panel B (n=41). C) Distribution of the RAD51 score in relationship to PARPi response (n=109). D) Comparison of ROC curves for the RAD51 score and Myriad myChoice® score for PARPi response in PDX (n=41).

We also quantified the whole genome sequencing (WGS)-derived HRD signature named HRDetect in an independent subset of 15 PDX, 10 of which were derived from BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and 11 from metastatic biopsies (Table S1). All PDX derived from patients with BRCA1/2-associated BCs had high HRDetect values (cut-off>0.7(6)). The GIS score in these models was concordant with HRDetect (Figure S1C). As observed for the Myriad myChoice® HRD scores, all PARPi-sensitive tumors had high HRDetect values, but 8 out of 11 PARPi-resistant tumors also had high HRDetect values (Figure S1D). In summary, these data show that genomic HRD tests provide very high sensitivity and NPV but limited specificity and PPV to predict PARPi response.

Association of functional HRD by RAD51 and PARPi sensitivity

We further aimed to investigate the functional HRD status of this PDX cohort, scoring the percentage of tumor cells with RAD51 nuclear foci in the S/G2-phase of the cell cycle (geminin-positive).(14,15) When comparing RAD51 with HRR-gene alterations, we noted that HRR-altered models had significantly lower levels of RAD51 values than HRR-WT PDX (median of 16% vs 50%, p<0.0001, Figure S1E), albeit 61% of HRR-gene altered tumors had high RAD51 scores. Similarly, 54% of tumors identified as positive for genomic HRD presented high RAD51 scores (Figure 3B).

Next, we explored the potential of the RAD51 score to predict PARPi response. PARPi-sensitive models showed a significantly lower percentage of RAD51-positive cells than the PARPi-resistant ones (median of 1% vs 38% respectively, p<0.0001; Figure 3C). Moreover, we observed an increase of the RAD51 score in the 13 models of acquired PARPi resistance derived in laboratory conditions, compared to their sensitive counterparts (median of 33% vs 1%, p=0.0006, Figure S1F). This result highlights the dynamic nature of the RAD51 test.

Using the pre-defined cut-off for RAD51 (RAD51≤10%),(9) the RAD51 assay demonstrated high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (98%), along with well-balanced PPV (93%) vs NPV (96%) (Table 1). In more detail, the RAD51 test predicted PARPi response in PDX harboring BRCA1, BRCA2 and PALB2 mutations (accuracy 92%, Figure S1G) and in PDX without mutation in these genes (accuracy 98%, Figures S1H). The accuracy of RAD51 to predict PARPi response was significantly higher than the obtained with the genomic HRD test (95% vs 71%, p<0.001). Of note, the discordant models according to the RAD51 test exhibited an intermediate response to PARPi (Figures S2A–C). A comparative receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted for RAD51 scores and Myriad myChoice® HRD test in the subset of 41 samples and revealed that the ROC AUC for the RAD51 assay was superior than for the genomic HRD score (0.97 vs. 0.81, p=0.03; Figure 3D). Altogether, these data validate the pre-defined RAD51 assay score cut-off and demonstrate that assessment of RAD51 nuclear foci by immunofluorescence is the most accurate and dynamic HRD biomarker for predicting PARPi response (Table 1).

Platinum response as biomarker of PARPi sensitivity

We established cisplatin response in a subset of 56 PDX, of which 51 were derived from breast cancers (Figure 4A). As expected, most of the PARPi-sensitive models were also sensitive to platinum (18/21, 86%), none of the PARPi-resistant PDX restoring BRCA1 function were platinum sensitive (0/8, 0%). Instead, the two 53BP1-dependent, PARPi-resistant PDX were platinum sensitive (2/2, 100%).(36)

Figure 4. Antitumor activity of cisplatin in PDX.

A) Waterfall plot showing the best response to cisplatin in 56 PDX, as the percentage of tumor volume change compared to the tumor volume on day 1. +20%, −30%, -95% are marked by dotted lines to indicate the range of PD, SD, PR, CR, respectively. B) Distribution of the RAD51 score in platinum-sensitive and resistant models (n=56).

We observed that platinum response provided lower accuracy to predict PARPi response than the RAD51 score (54% vs. 95%, Table 1). Regarding RAD51 scores and cisplatin response, we observed that cisplatin-sensitive PDX models had overall lower values of RAD51 than cisplatin-resistant PDX (median of 12% vs 21%, p=0.02, Figure 4B). However, 16/31 of the cisplatin-sensitive models presented high RAD51 scores, which suggests that these models carry deficiencies in other DNA repair pathways involved in repair of platinum-induced damage (e.g. nucleotide excision repair or Fanconi anemia pathway). Accuracy of the RAD51 assay to predict cisplatin response was similar to HRR-gene mutations or to BRCA1 epigenetic silencing (64%, 61% and 63%, respectively; Table 2). These results suggest that the RAD51 assay could help to identify patients who are likely to respond to platinum-based treatments with a similar accuracy of other HRD tests currently used in clinical practice.

Table 2. Test performance values for the indicated HRD biomarkers predicting cisplatin response.

| Biomarkers of cisplatin response | BRCA1/2, PALB2 mutations (n=56) | Low BRCA1 mRNA/foci (n=56) | RAD51 score (≤10) (n=56) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 68% | 42% | 48% |

| Specificity | 52% | 88% | 84% |

| PPV | 64% | 81% | 79% |

| NPV | 57% | 55% | 57% |

| Accuracy | 61% | 63% | 64% |

Patient-derived models recapitulate patient’s HRD status and in vivo response to PARPi

The HRD status by RAD51 in PDX was highly concordant with the corresponding patient’s FFPE tumor sample that was taken at the same time-point when the patient-derived xenograft model was established (Cohen’s kappa=0.93, Figure 5A). In agreement, the PDX response to PARPi or platinum was also highly concordant to the patient’s response to the respective drug (30 out of 36, 83% concordance, Table S2).

Figure 5. Homologous recombination repair functionality and PARPi sensitivity is concordant in patient, PDX and PDC.

A) RAD51 scores in PDX and in patient’s tumor samples concurrent to the PDX establishment. B) RAD51 in PDX and corresponding PDC treated with PARPi or vehicle. C) Representation of the logarithm of the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of PDCs treated with olaparib in comparison to the in vivo sensitivity. D) Bright-field microscopic images showing one PARPi-sensitive model (PDC405) and one PARPi-resistant model (PDC270) untreated (control) and treated with olaparib 1 µM for 14 days.

Patient-derived tumor organoids from HGSOC are being established to assess drug responses to targeted drugs in a real-time manner.(37) Therefore, we further assessed the ability of patient-derived tumor cells (PDC) to recapitulate the HRD status of the PDX and the in vivo responses to PARPi. In a cohort of 14 models, the RAD51 score in PDC was highly concordant with the score in PDX, both when the models were PARPi-treated (kappa coefficient=0.68) or left untreated (kappa coefficient=0.74, Figures 5B, S3). Concordantly, treatment with olaparib resulted in lower half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values in 24 PDC derived from PARPi-sensitive PDX than from resistant ones (102nM vs 102.9nM, p=0.017, Figures 5C,D). In summary, we demonstrated that both PDX and PDC recapitulate patient’s HRD status and in vivo response to PARPi.

Discussion

In the era of precision oncology, there is an unmet medical need for optimized use of PARPi and platinum-based chemotherapy. The use of validated HRD tests in clinical practice may fill this gap. Ideally, this test should offer a fast turnaround time, be accurate and of low cost, and be close to the point of care. In this work, we validated the predictive value of the RAD51-immunofluorescence test for PARPi response in a panel of patient-derived tumor models that recapitulated patients’ characteristics and response to PARPi or platinum. Compared to genetic and genomic HRD tests, the RAD51 test exhibited greater PPV (93% vs. 43-50%), implying a better capacity to identify patients with PARPi-sensitive tumors and differentiate from those that become PARPi-resistant after restoration of functional HRR. Alike genomic HRD tests, RAD51 identified HRD in tumors with epigenetic silencing of BRCA1, as evidenced by concomitant low expression of BRCA1 mRNA expression or low BRCA1 nuclear foci. Importantly, the RAD51 test captured the dynamic nature of HRD as shown in paired models with acquired resistance to PARPi. Regarding platinum response, the RAD51 test showed similar accuracy to HRR-gene mutations (64% vs. 61%).

In our PDX cohort, 58% of models harbored an HRR alteration, mainly driven by genetic alterations in BRCA1/2 or epigenetic silencing of BRCA1. The preclinical response rate to PARPi amongst these models was only of 42%, highlighting the limited PPV of these selection biomarkers. We identified the potential mechanism of resistance in half of the resistant models, encompassing the restoration of HRR-gene function in 24%, restoration of end resection mediated by the 53BP1 pathway in 4% or RAD51-independent mechanisms in 4%. RAD51-independent mechanisms of PARPi sensitivity or resistance represent a limitation for the accuracy of the RAD51 test. As an example, enhanced PARP trapping causes PARPi toxicity irrespective of HRD, such as in tumors with impaired ribonucleotide or base excision repair due to defects in RNaseH2 or XRCC1, respectively.(38,39) Impairment of enzymes involved in other base damage repair pathways e.g., loss of ALC1 nucleosome remodeling, also confers PARPi sensitivity.(40,41) The clinical relevance of these mechanisms is yet to be established. For 26% of the PDX in our cohort, the mechanism of resistance was not revealed by WES, but consistent with restoration of HRR by RAD51 nuclear foci formation.

The lack of PPV of the tests based on detection of HRR alterations (gene mutations or epigenetic silencing) lies upon the heterogeneity of the HRD nature. Also, even though genomic HRD tests encompass the different sources of HRD, they cannot distinguish HRR restoration. In contrast, a dynamic functional biomarker alike RAD51 can capture this heterogeneity. The discordance between genomic HRD tests and RAD51 foci is observed in half of the PDX, especially in models harboring BRCA1 epigenetic silencing, likely reflecting the “soft” status of the phenotype. This observation is in line with the TBCRC009 and TNT trials for platinum.(42,43) In summary, a functional test like RAD51 foci shows an improved performance because it captures the different sources of HRD as well as its dynamic evolution.

In patients with metastatic breast cancer, the PARPi olaparib and talazoparib have been approved for patients with a germline BRCA1 (gBRCA1) or germline BRCA2 (gBRCA2) pathogenic variant. Nevertheless, the overall response rate is within the range of 60%.(44,45) In the context of a known germline condition, a functional test that measures the tumor status of HRD before treatment initiation would likely improve patient selection for PARPi monotherapy. This would allow to optimize the prescription of effective drugs in patients who have restored HRR in their tumors. A similar scenario is expected for patients with germline pathogenic genetic alterations in PALB2 who are also sensitive to PARPi.(27,46) In addition, efforts are also being invested in expanding the patient population who may benefit from PARPi beyond those harboring germline HRR-gene pathogenic variants with metastatic cancer. Given the positive safety profile of PARPi and preliminary efficacy data in the early disease setting,(28,47) it is expected that PARPi will be incorporated as part of the neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment regimens.(48) In this regard, data supporting the use of genomic HRD tests or RAD51 as predictive biomarkers of PARPi response in breast cancer is encouraging and analysis in larger cohorts is awaited.(20,49)

Regarding platinum response and BC, genomic scars have failed to identify patients who may benefit both in the early and metastatic settings, and gBRCA1/2-mutations predicted platinum response exclusively in the metastatic setting.(43,50) Interestingly, despite cisplatin sensitivity may occur beyond HRD,(51) our preclinical data showed that the RAD51 assay may help select patients who benefit from platinum treatment, thus giving a “target” therapy option to gBRCA1/2 WT patients. In untreated TNBC, RAD51 independently predicted clinical benefit from adding carboplatin to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.(22) Further studies are needed to confirm the clinical validity of the RAD51 assay at predicting long-term platinum benefit, and to verify if the test could predict response to treatments with similar mechanism of action.

Functional biomarkers of HRD are also needed for the management of HGSOC, advanced prostate cancer or pancreatic cancer. Despite quality of tumor genetic testing and interpretation of variants’ effect have greatly improved in the recent years, there is still a scarcity of implementation of tumor genetic testing beyond the ovarian cancer population. Regarding platinum-sensitive HGSOC, PARPi have been approved as first and second-line maintenance therapy.(1,52–54) Recently, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved olaparib in combination with bevacizumab (an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody) as first-line therapy in HRD-positive platinum-sensitive HGSOC patients, using an HRD diagnostic test with demonstrated clinical validity.(1,8,55–57) This setting provides an opportunity to clinically validate the RAD51 assay. Regarding prostate cancer, the PARPi olaparib and rucaparib are now approved for men with metastatic disease(1,58), but significant intra-patient variability in clinical outcomes has been observed, particularly for those patients with alterations in genes beyond BRCA2. A functional assay such as RAD51 can be relevant to assess the clinical value of less-frequent alterations in other DNA damage repair genes, e.g. PALB2, and guide patient stratification(21). Finally, olaparib is the first targeted therapy that has been approved for gBRCA1/2-mutated pancreatic tumors that previously responded to platinum salts.(59) In this context, the RAD51 assay could be helpful to: 1) avoid platinum-based chemotherapy as selection biomarker, thus reducing toxicities for patients who may not benefit from them; 2) select patients that needed to otherwise be tested for gBRCA1/2 status, considering the low incidence of the mutations in this subset of patients; 3) increase the number of patients who may benefit from PARPi beyond those with gBRCA1/2 mutations.

We foresee that the RAD51 test will have some limitations in relationship with PARPi response: 1) it will not identify tumors whose sensitivity to PARPi lies on a DNA repair deficiency outside of the HRR core pathway (i.e. due to alterations in ATM, RNaseH2, XRCC1, ALC1); and 2) it will not identify secondary PARPi-resistance when the mechanism does not involve restoration of HRR (i.e. replication fork stabilization). In summary, the RAD51 assay could help to identify 1) patients harboring gBRCA1/2 or gPALB2 mutations who are likely to be PARPi-resistant and 2) patients without a germline condition in BRCA1/2 or PALB2 with HRD-positive tumors who are likely to be PARPi-sensitive. Using PDX we confirmed the superior predictive value of an immunofluorescence-based test detecting RAD51 nuclear foci in preclinical models treated with PARPi when compared to HRR-gene mutations, genomic HRD tests and platinum sensitivity. Given the supportive clinical data,(20,22,49) we propose to continue the analytical validation and the clinical qualification of the RAD51 assay in larger cohorts of BC patients treated with PARPi or platinum salts.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

This work demonstrates the high accuracy of a histopathology-based test on the detection of RAD51 nuclear foci in predicting response to PARP inhibitors and cisplatin.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients for providing study samples. The authors acknowledge the CELLEX foundation for providing research equipment and facilities. We thank CERCA Program / Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support. We acknowledge funding from AstraZeneca and Tesaro supporting this study [to V. Serra]. The GHD-Pink program, the FERO Foundation, and the Orozco Family provided funding for establishment of the PDX models at VHIO. This study has also been supported by the Catalan Agency AGAUR-FEDER (2017 SGR 540, 2019PROD00045) [to V.Serra and A.Llop-Guevara]. V.Serra, J.Balmaña and S.Gutiérrez-Enríquez received funds from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), an initiative of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Innovation partially supported by European Regional Development FEDER Funds: grants PI12/02606, PI17/01080; PI19/01303; PI20/00892, CP14/00228 and CPII19/00033. The study is also the result from a Transcan-2 effort (AC15/00063), the Spanish Association of Cancer Research (AECC, LABAE16020PORTT) and from the SPORE in Breast Cancer (National Cancer Institute USA P50CA098131). La Caixa Foundation and the European Institute of Innovation and Technology/Horizon 2020 (CaixaImpulse) [LCF/TR/CC19/52470003] provided funds to A.Llop-Guevara. B.Pellegrino was supported by ESMO with a Clinical Translational Fellowship aid supported by Roche. Any views, opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those solely of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of ESMO or Roche. A.Llop-Guevara received funding from Generalitat de Catalunya (PERIS SLT002/16/00477) and AECC (INVES20095LLOP).

A. Herencia-Ropero received funding from Generalitat de Catalunya (PERIS SLT017/20/000081). F.Pedretti received a fellowship from “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) (LCF/BQ/DI19/11730051). This work was also supported by Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF-19-08), Instituto de Salud Carlos III project AC15/00062 and the EC under the framework of the ERA-NET TRANSCAN-2 initiative co-financed by FEDER, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CB16/12/00449 and PI19/01181), and AECC (to J.Arribas). M. Espinosa-Bravo reports grants from FERO Foundation and from ISCIII. J.Mateo received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement 837900. S.Nik-Zainal, J.Dias and A.Degasperi are supported by Cancer Research UK (CRUK) Advanced Clinician Scientist Award grant C60100/A23916, CRUK Pioneer Award, CRUK Grand Challenge Award grant C60100/A25274 and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre grant BRC-125-20014. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

B.P. received honoraria from Novartis and BMS. V.S. received research funds from AstraZeneca and Tesaro, and honoraria from Abbie. J.B. received honoraria and travel money from AstraZeneca and Pfizer. V.S., J.B. and A.L.G. are named as inventors for patent PCT/EP2018/086759 (WO2019122411A1). S.C. is employee of XenTech. M.O.C, J.V.F are employees and shareholders of AstraZeneca. Y.Z. is employee from Tesaro. V.P. has received fees as consultant, participated in advisory boards or received travel grants from Roche, Sysmex, MSD, AstraZeneca, Bayer and Exact Sciences. M.O. received research support from AstraZeneca, Philips Healthcare, Genentech, Roche, Novartis, Immunomedics, Seattle Genetics, GSK, Boehringer-Ingelheim, PUMA Biotechnology, Zenith Epigenetics. She has received fees as consultant from Roche, Seattle Genetics, GSK, PUMA Biotechnology, AstraZeneca, and received honoraria from Roche, Seattle Genetics, Novartis, Guardant Health and Pfizer, as well as travel money from Roche, Pierre-Fabre, Novartis and Eisai. She is member of the SOLTI Breast Cancer Research Executive Board and Scientific Committee. J.M. served on advisory boards from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer and Roche and received research funding from AstraZeneca and Pfizer Oncology (not related to this work). A.M. reports grants and other from Eisai Co., Ltd; grants and personal fees from Roche; personal fees from MacroGenics; personal fees from Merck; grants and personal fees from Lilly; grants from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. T.M. received honoraria as consultant/advisory with Amgen, Baxter, Celgene, Incyte, Q&D Therapeutics, Serviere, Shire; research funding from AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Celgene. M.B. received honoraria as advisory/ conferences with Pfizer, Lilly, Novartis and travel expenses with Pfizer.

Data Availability Statement

Readers can find the genomics data acquired and used in this study in Supplementary Table 3.

References

- 1.Lynparza. European Medicines Agency; [cited 2021 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/lynparza. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokol ES, Pavlick D, Khiabanian H, Frampton GM, Ross JS, Gregg JP, et al. JCO Precis Oncol. Vol. 4. American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO); 2020. Pan-Cancer Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genomic Alterations and Their Association With Genomic Instability as Measured by Genome-Wide Loss of Heterozygosity; pp. 442–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonsson P, Bandlamudi C, Cheng ML, Srinivasan P, Chavan SS, Friedman ND, et al. Tumour lineage shapes BRCA-mediated phenotypes. Nature Nature Publishing Group. 2019 Jul 25;:576–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1382-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abkevich V, Timms KM, Hennessy BT, Potter J, Carey MS, Meyer LA, et al. Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1776–82. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heeke AL, Pishvaian MJ, Lynce F, Xiu J, Brody JR, Chen W-J, et al. JCO Precis Oncol. Vol. 2. American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO); 2018. Prevalence of Homologous Recombination–Related Gene Mutations Across Multiple Cancer Types; pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies H, Glodzik D, Morganella S, Yates LR, Staaf J, Zou X, et al. Nat Med. Vol. 23. Nature Publishing Group; 2017. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures; pp. 517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, Wang K, Downing SR, He J, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1023–31. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2696. Nat Biotechnol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller RE, Leary A, Scott CL, Serra V, Lord CJ, Bowtell D, et al. Ann Oncol. Vol. 31. Elsevier Ltd; 2020. ESMO recommendations on predictive biomarker testing for homologous recombination deficiency and PARP inhibitor benefit in ovarian cancer; pp. 1606–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graeser M, McCarthy A, Lord CJ, Savage K, Hills M, Salter J, et al. A Marker of Homologous Recombination Predicts Pathologic Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Primary Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6159–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naipal KAT, Verkaik NS, Ameziane N, Van Deurzen CHM, Ter Brugge P, Meijers M, et al. Clin Cancer Res. Vol. 20. American Association for Cancer Research Inc; 2014. Functional Ex vivo assay to select homologous recombination-deficient breast tumors for PARP inhibitor treatment; pp. 4816–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chun J, Buechelmaier ES, Powell SN. Mol Cell Biol. Vol. 33. American Society for Microbiology; 2013. Rad51 Paralog Complexes BCDX2 and CX3 Act at Different Stages in the BRCA1-BRCA2-Dependent Homologous Recombination Pathway; pp. 387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holliday DL, Speirs V. Choosing the right cell line for breast cancer research. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:215. doi: 10.1186/bcr2889. Breast Cancer Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whittle JR, Lewis MT, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Breast Cancer Res. BioMed Central Ltd; 2015. Patient-derived xenograft models of breast cancer and their predictive power; p. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz C, Castroviejo-Bermejo M, Gutiérrez-Enriquez S, Llop-Guevara A, Ibrahim Y, Gris-Oliver A, et al. RAD51 foci as a functional biomarker of homologous recombination repair and PARP inhibitor resistance in germline BRCA mutated breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1203–10. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castroviejo-Bermejo M, Cruz C, Llop-Guevara A, Gutiérrez‐Enríquez S, Ducy M, Ibrahim YH, et al. A RAD51 assay feasible in routine tumor samples calls PARP inhibitor response beyond BRCA mutation. EMBO Mol Med. 2018:e9172. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruna A, Rueda OM, Greenwood W, Batra AS, Callari M, Batra RN, et al. Cell. Vol. 167. Cell Press; 2016. A Biobank of Breast Cancer Explants with Preserved Intra-tumor Heterogeneity to Screen Anticancer Compounds; pp. 260–274.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato T, Clevers H. Cell. Cell Press; 2015. SnapShot: Growing Organoids from Stem Cells; p. 1700.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clevers H. Cell. Cell Press; 2016. Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids; pp. 1586–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gris-Oliver A, Palafox M, Monserrat L, Brasó-Maristany F, Òdena A, Sánchez-Guixé M, et al. Clin Cancer Res. Vol. 26. NLM (Medline); 2020. Genetic Alterations in the PI3K/AKT Pathway and Baseline AKT Activity Define AKT Inhibitor Sensitivity in Breast Cancer Patient-derived Xenografts; pp. 3720–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eikesdal HP, Yndestad S, Elzawahry A, Llop-Guevara A, Gilje B, Blix ES, et al. Ann Oncol. Vol. 32. Elsevier Ltd; 2021. Olaparib monotherapy as primary treatment in unselected triple negative breast cancer; pp. 240–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carreira S, Porta N, Arce-Gallego S, Seed G, Llop-Guevara A, Bianchini D, et al. Biomarkers Associating with PARP Inhibitor Benefit in Prostate Cancer in the TOPARP-B Trial. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:2812–27. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0007. Cancer Discov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llop-Guevara A, Loibl S, Villacampa G, Vladimirova V, Schneeweiss A, Karn T, et al. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. Elsevier; 2021. Association of RAD51 with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) and clinical outcomes in untreated triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC): analysis of the GeparSixto randomized clinical trial. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sztupinszki Z, Diossy M, Krzystanek M, Reiniger L, Csabai I, Favero F, et al. npj Breast Cancer. Vol. 4. Nature Publishing Group; 2018. Migrating the SNP array-based homologous recombination deficiency measures to next generation sequencing data of breast cancer; pp. 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ter Brugge P, Kristel P, van der Burg E, Boon U, de Maaker M, Lips E, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. Oxford University Press; 2016. Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance in Patient-Derived Xenograft Models of BRCA1-Deficient Breast Cancer; p. 108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballabeni A, Zamponi R, Moore JK, Helin K, Kirschner MW. Geminin deploys multiple mechanisms to regulate Cdt1 before cell division thus ensuring the proper execution of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E2848–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310677110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loibl S, Weber KE, Timms KM, Elkin EP, Hahnen E, Fasching PA, et al. Survival analysis of carboplatin added to an anthracycline/taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy and HRD score as predictor of response – final results from GeparSixto. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:2341–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tung NM, Robson ME, Ventz S, Santa-Maria CA, Nanda R, Marcom PK, et al. J Clin Oncol. Vol. 38. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2020. TBCRC 048: Phase II Study of Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer and Mutations in Homologous Recombination-Related Genes; pp. 4274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Litton JK, Scoggins M, Hess KR, Adrada B, Barcenas CH, Murthy RK, et al. J Clin Oncol. Vol. 36. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2018. Neoadjuvant talazoparib (TALA) for operable breast cancer patients with a BRCA mutation (BRCA+) p. 508. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaspers JE, Kersbergen A, Boon U, Sol W, Van Deemter L, Zander SA, et al. Loss of 53BP1 causes PARP inhibitor resistance in BRCA1-mutated mouse mammary tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:68–81. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0049. Cancer Discov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu G, Ross Chapman J, Brandsma I, Yuan J, Mistrik M, Bouwman P, et al. Nature. Vol. 521. Nature Publishing Group; 2015. REV7 counteracts DNA double-strand break resection and affects PARP inhibition; pp. 541–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dev H, Chiang TWW, Lescale C, de Krijger I, Martin AG, Pilger D, et al. Nat Cell Biol. Vol. 20. Nature Publishing Group; 2018. Shieldin complex promotes DNA end-joining and counters homologous recombination in BRCA1-null cells; pp. 954–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drost R, Dhillon KK, Van Der Gulden H, Van Der Heijden I, Brandsma I, Cruz C, et al. J Clin Invest. Vol. 126. American Society for Clinical Investigation; 2016. BRCA1185delAG tumors may acquire therapy resistance through expression of RING-less BRCA1; pp. 2903–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Bernhardy AJ, Cruz C, Krais JJ, Nacson J, Nicolas E, et al. Cancer Res. Vol. 76. American Association for Cancer Research Inc; 2016. The BRCA1-Δ11q alternative splice isoform bypasses germline mutations and promotes therapeutic resistance to PARP inhibition and cisplatin; pp. 2778–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Bernhardy AJ, Nacson J, Krais JJ, Tan YF, Nicolas E, et al. Nat Commun. Vol. 10. Nature Research; 2019. BRCA1 intronic Alu elements drive gene rearrangements and PARP inhibitor resistance; pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coussy F, El-Botty R, Château-Joubert S, Dahmani A, Montaudon E, Leboucher S, et al. Sci Transl Med. Vol. 12. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2020. BRCAness, SLFN11, and RB1 loss predict response to topoisomerase I inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancers; eaax2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunting SF, Callén E, Kozak ML, Kim JM, Wong N, López-Contreras AJ, et al. BRCA1 Functions Independently of Homologous Recombination in DNA Interstrand Crosslink Repair. Mol Cell. 2012;46:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.02.015. Mol Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farkkila A, Rodríguez A, Oikkonen J, Gulhan DC, Nguyen H, Domínguez J, et al. Cancer Res. Vol. 81. American Association for Cancer Research (AACR); 2021. Heterogeneity and clonal evolution of acquired PARP inhibitor resistance in TP53- And BRCA1-deficient cells; pp. 2774–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horton JK, Stefanick DF, Prasad R, Gassman NR, Kedar PS, Wilson SH. Base excision repair defects invoke hypersensitivity to PARP inhibition. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12:1128–39. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0502. Mol Cancer Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmermann M, Murina O, Reijns MAM, Agathanggelou A, Challis R, Tarnauskaite Ž, et al. CRISPR screens identify genomic ribonucleotides as a source of PARP-trapping lesions. Nature. 2018;559:285–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0291-z. Nature. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma P, Zhou Y, Cao Z, Deraska PV, Deb M, Arai E, et al. ALC1 links chromatin accessibility to PARP inhibitor response in homologous recombination-deficient cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2021;23:160–71. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-00624-3. Nat Cell Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hewitt G, Borel V, Segura-Bayona S, Takaki T, Ruis P, Bellelli R, et al. Defective ALC1 nucleosome remodeling confers PARPi sensitization and synthetic lethality with HRD. Mol Cell. 2021;81:767–783.:e11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.12.006. Mol Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isakoff SJ, Mayer EL, He L, Traina TA, Carey LA, Krag KJ, et al. TBCRC009: A multicenter phase II clinical trial of platinum monotherapy with biomarker assessment in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1902–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tutt A, Tovey H, Cheang MCU, Kernaghan S, Kilburn L, Gazinska P, et al. Carboplatin in BRCA1/2-mutated and triple-negative breast cancer BRCAness subgroups: The TNT Trial. Nat Med. 2018;24:628–37. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0009-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Gonçalves A, Lee K-H, et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:753–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robson M, Im S-A, Senkus E, Xu B, Domchek SM, Masuda N, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:523–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gruber JJ, Afghahi A, Hatton A, Scott D, McMillan A, Ford JM, et al. J Clin Oncol. Vol. 37. American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO); 2019. Talazoparib beyond BRCA: A phase II trial of talazoparib monotherapy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 wild-type patients with advanced HER2-negative breast cancer or other solid tumors with a mutation in homologous recombination (HR) pathway genes; p. 3006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fasching PA, Link T, Hauke J, Seither F, Jackisch C, Klare P, et al. Ann Oncol. Vol. 32. Elsevier Ltd; 2021. Neoadjuvant paclitaxel/olaparib in comparison to paclitaxel/carboplatinum in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer and homologous recombination deficiency (GeparOLA study) pp. 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, Viale G, Fumagalli D, Rastogi P, et al. N Engl J Med. Vol. 384. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2021. Adjuvant Olaparib for Patients with BRCA1 - or BRCA2 -Mutated Breast Cancer; pp. 2394–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chopra N, Tovey H, Pearson A, Cutts R, Toms C, Proszek P, et al. Nat Commun. Vol. 11. Nature Research; 2020. Homologous recombination DNA repair deficiency and PARP inhibition activity in primary triple negative breast cancer; pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hahnen E, Lederer B, Hauke J, Loibl S, Kröber S, Schneeweiss A, et al. Germline Mutation Status, Pathological Complete Response, and Disease-Free Survival in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1378. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Postel-Vinay S, Soria JC. J Clin Oncol. NLM (Medline); 2017. ERCC1 as Predictor of Platinum Benefit in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer; pp. 384–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zejula. INN-niraparib. [cited 2021 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zejula.

- 53.Rubraca. European Medicines Agency; [cited 2021 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rubraca. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banerjee S, Moore KN, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim B-G, Oaknin A, et al. Ann Oncol. Vol. 31. Elsevier BV; 2020. 811MO Maintenance olaparib for patients (pts) with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer (OC) and a BRCA mutation (BRCAm): 5-year (y) follow-up (f/u) from SOLO1; S613 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S, Pérol D, González-Martín A, Berger R, et al. N Engl J Med. Vol. 381. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2019. Olaparib plus Bevacizumab as First-Line Maintenance in Ovarian Cancer; pp. 2416–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, Scott CL, Giordano H, Sun J, et al. Lancet Oncol. Vol. 18. Elsevier Ltd; 2017. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial; pp. 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anscher MS, Chang E, Gao X, Gong Y, Weinstock C, Bloomquist E, et al. Oncologist. Vol. 26. Wiley-Blackwell; 2021. FDA Approval Summary: Rucaparib for the Treatment of Patients with Deleterious BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer; pp. 139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Vol. 381. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2019. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA -Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer; pp. 317–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Readers can find the genomics data acquired and used in this study in Supplementary Table 3.