Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a severely painful and debilitating disease of the joint, which brings about degradation of the articular cartilage and currently has few therapeutic solutions. 2-dimensional (2D) high-throughput screening assays have been widely used to identify candidate drugs with therapeutic potential for the treatment of OA. A number of small molecules which improve the chondrogenic differentiation of progenitor cells for tissue engineering applications have also been discovered in this way. However, due to the failure of these models to accurately represent the native joint environment, the efficacy of these drugs has been limited in vivo. Screening systems utilizing 3-dimensional (3D) models, which more closely reflect the tissue and its complex cell and molecular interactions, have also been described. However, the vast majority of these systems fail to recapitulate the complex, zonal structure of articular cartilage and its unique cell population. This review summarizes current 2D high throughput screening (HTS) techniques and addresses the question of how to use existing 3D models of tissue engineered cartilage to create 3D drug screening platforms with improved outcomes.

Keywords: articular cartilage, high-throughput screening assays, osteoarthritis, chondrogenesis, tissue engineering, drug evaluation

Introduction

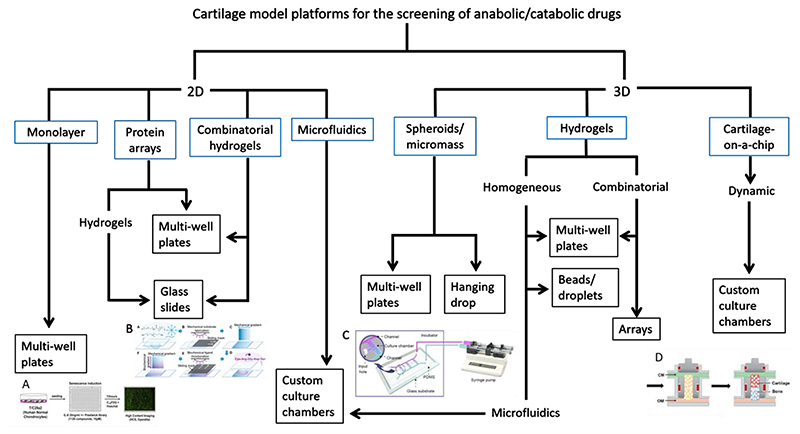

2D high-throughput screening (HTS) assays have been widely used to test compounds for therapeutic potential for the treatment of OA. However, success has been limited due to the failure of these models to accurately represent the in vivo environment. As a result, some groups have developed 3D models, which simulate native cartilage tissue and its complex cell and molecular interactions more accurately. This review summarises the current state-of-the-art 2D and 3D high-throughput systems for cartilage drug screening (figure 1), and addresses the question of how to use 3D models of tissue engineered cartilage to create screening platforms with improved outcomes. Future steps needed for improved 3D models will be identified.

Figure 1. Schematic of existing 2D and 3D drug screening platforms for cartilage and tissues of a similar lineage.

Blue boxes denote model type, black boxes denote culture formats. A. 2D multi-well plate format (reprinted by permission from Nogueira-Recalde et al. 9). B. Combinatorial hydrogel system on glass slide format (reprinted by permission from Tong et al. 45). C. 3D hydrogel microfluidic platform (reprinted by permission from Li et al. 101). D. Osteochondral chip screening platform (reprinted by permission from Lin et al. 114)

2D screening platforms

Cartilage has good phenotypic outcomes which are amenable to screening platforms. For example, the expression of type II collagen, aggrecan and sulphated glycosaminoglycans (sGAG) in the matrix are easily detected with a range of assays or dyes, and measurable alterations in its mechanical properties occur as a result of pathology or aberrant development 1. Cell-based assays, involving the application of robotics and multi-well plates to screen vast libraries of chemical compounds for a potential effect on an identified target or pathway 2,3 are a cornerstone of the drug discovery and approval process. Similarly, though often on smaller scale, such screening methods have identified small molecules which have generated much interest in the field of cartilage tissue engineering by drastically improving the chondrogenic differentiation and/or anabolic activity of precursor cells and chondrocytes.

Small molecules offer significant advantages over the growth factors and cytokines traditionally used to direct stem cell fate – the most notable being reproducibility, reduced immunogenicity, reduced manufacturing costs, improved stability (owing to low order structure) and avoidance of xenogeneic sources 4. In addition, rapid HTS allows for repurposing of small molecules with existing FDA approval which possess some hitherto unknown beneficial effect on catabolic pathways associated with joint pathogenesis or on cellular differentiation/anabolic activity. Add to that the reproducibility of these substances and the resultant implications for adopting Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), and this renders therapies exploiting small molecules more amenable to clinical translation. Instead of utilising growth factors with known modes of action in relevant cell signalling pathways, the focus is now very much on identifying small molecules which act as agonists or antagonists of those pathways, and 2D screening platforms are a rapid and cost-effective means of doing so.

Cell sources for HTS

Primary chondrocytes appear to be the obvious cell choice for 2D screening assays seeking to identify novel modifiers of anabolic/catabolic response. Unfortunately, the issue of de-differentiation during the extensive cell number expansion period required for significant scale-up limits the usefulness of these cells in HTS platforms. Chondrocyte de-differentiation in monolayer culture is a well-established phenomenon, characterised by changes in morphology (from a rounded to a more fibroblastic structure) and reduction in the expression of makers such as aggrecan and type II collagen, with concomitant increases in expression of type I collagen 5,6. Though some studies have utilized primary chondrocytes in 2D screening assays 7–9, others have opted for induced cartilage models 10 or chondrogenic cell lines 11,12. A recent study used the T/C28a2 cell line, in conjunction with automated liquid handling and high content screening, to test 1120 compounds for potential effectors of senescence and autophagy 9 (both associated with OA). For such large-scale screens, sufficient cell numbers would be difficult to obtain without the use of a cell line, although pluripotent cells may offer an alternative.

Interestingly, the majority of studies screening for potential novel inducers of chondrogenic differentiation opt for bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) as the cellular component of their platform. Presumably this is due to their well-documented chondrogenic potential 13–15, high proliferative capacity 16 and the relative ease with which they can be isolated 13. In addition, safety and efficacy has been shown in a number of clinical trials 17 utilising BMSC and they have demonstrated immune-modulatory and anti-inflammatory effects 18. However, chondrogenic differentiation of these cells requires external media induction and there is a large body of evidence (reviewed elsewhere) to suggest that they are not able to produce hyaline cartilage 19. A screening platform incorporating the cartilage superficial zone-resident progenitors would be more relevant, although limited availability of these cells would pose a barrier to high scale-up.

CRISPR gene editing allows for rapid and precise manipulation of target alleles without the risk of tumorigenicity associated with previously favoured modalities 20,21. This technology could be utilised to overcome some of the barriers to scale-up by generating stem cells with reduced susceptibility to senescence 22,23 and increased differentiation potential 24, or by triggering the re-differentiation of expanded chondrocytes 25, all of which would aid the production of more relevant screening models.

Simple 2D screening platforms

2D screening platforms have yielded a number of promising candidates for cartilage tissue engineering and for tissues with a similar developmental lineage (table 1). Small molecules with therapeutic potential for cartilage repair have also been identified, including BNTA 11, licofelone 26,27 and balicatib 4,28. Kartogenin (KGN), developed by the Novartis Research Foundation 29, is one of the more successful examples and demonstrates how effective simple HTS can be. In this system 22,000 heterocyclic molecules were screened using a 384-well format seeded with human BMSC; the presence of chondrogenic nodules, stained with rhodamine B and identified with simple light microscopy, revealed a “hit”. This small molecule was also shown to promote an early cell condensation phenotype and production of cartilage specific markers collagen type II and sex determining region Y-box 9 (SOX9). Since then, a number of groups have confirmed its beneficial effects on chondrogenic differentiation in vitro 30–32 and reported promising outcomes in small animal cartilage injury models 30,32.

Table 1. 2D screening platforms for cartilage.

| Authors | Cell type(s) | Model | Chondrogenic medium? | Molecules/parameters tested | Culture period | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson et al.(2012) 29 | Human BMSC | 384-well format. Cells seeded in monolayer and molecules added to medium. | No | 22,000 structurally diverse, heterocyclic, drug-like molecules (5 μM). KGN hit. | 4 days | Presence of chondrogenic nodules with rhodamine B staining and light microscopy |

| Rape et al. (2015)44 | Human glioblastoma cells and ASC | Combinatorial hydrogels. HA gels with stiffness and fibronectin density gradients cured onto glass slides. Cells seeded on top. | No | Different stiffnesses and fibronectin concentrations | 2 days (glioblastoma) and 7 days (hASC) | Cancer model: miR18a expression via fluorescence assay. Adipogenic/osteogenic model: Oil Red O and NBT/BCIP staining. |

| Floren and Tan (2015) 42 | Rodent BMSC/PASMC | ECM microarray. Electrospun PEGDM and PEO deposited onto glass slides and photopolymerised. Spotted with different ECM proteins. Cells seeded on top | No | Collagen I, collagen III, collagen IV, laminin, fibronectin, elastin | 24 hours | Cell adhesion and spreading with DAPI and phalloidin. ICC (PECAM-1 vascular marker). Imaged with automated confocal microscopy |

| Le et al. (2015) 12 | ATDC5 chondrogenic cell line | 96-well format. Cells seeded in monolayer and molecules added to medium. | Yes | LOPAC library of 1280 pharmaceutically active compounds | 9 days | Total collagen via fluorescent collagen probe assay. |

| Choi et al. (2016)33 | Human ASC | 60 mm plates. Cells seeded in monolayer and molecules added to medium. | No | In-house protein kinase inhibitor library of sulphonamides (1 μM and 10 μM). Compound 6 hit. | 11 days | Aggrecan expression via ELISA |

| Tong et al. (2016)45 | Human fibroblasts | Combinatorial PEG hydrogels with mechanical and ligand density gradients formed on glass slides and cells seeded on top. | No | Different stiffnesses and RGD binding densities | 24 hours | Cell adhesion and morphology, cytoskeleton structure and spreading/elongation all via staining and microscopy |

| Sharma et al. (2017) 7 | Various, including bovine chondrocytes | PEG hydrogels electrospun onto glass slide and UV cured, then peptide microarray deposited on top via array spotting system. Cells (mono- and co-cultures) seeded on top. | Yes (chondrocytes only) | Multiple peptide motifs and concentrations | 24 hours | Cell adhesion and morphology and cytoskeleton structure via staining and confocal microscopy |

| Ming et al. (2018) 8 | Rodent chondrocytes | Microfluidic device used to create concentration gradient of molecule. 8 concentrations of medium/drug directed to cells cultured in monolayer in 8 downstream chambers. | No | Resveratrol (0-200 μM) | 3 days | Proliferation via cell counting via light microscopy |

| Gobaa et al. (2018) 43 | Human BMSC | 2016-well format, combinatorial protein array. Proteins deposited onto thin layer of PEG hydrogel via robotic liquid handling system and cells seeded on top. | No | Wnt3a, Wnt5a, DKK1, BMP2, DLL4, Jag, DLK1, NCAM, GDF8, CCL2, laminin Different PEG stiffnesses | 11 days | Proliferation with DAPI and phalloidin and adipogenic differentiation with Nile Red staining. Imaged with automated microscopy |

| Deshmukh et al. (2018) 10 | TCF/LEF reporter cell line and human BMSC | Molecules adhered to multi-well screening plates via robotic liquid handling system and cell seeded on top. | Yes (BMSC only) | Wnt pathway inhibitors: SM04690, FH535, IWR-1, ICG001, iCRT14, KY02111, CX.4945 | 2 days (TCF/LEF reporters) 5 days (hBMSC) | Luciferase activity (TCF/LEF reporters) Presence of chondrogenic nodules with rhodamine B staining and automated imaging system (hBMSC) |

| Nogueira-Recalde (2019) 9 | T/C28a2 chondrocyte cell line | 384-well format. Cells seeded in monolayer. Aged/senescent model induced with IL-6. Automated cell dispensing and liquid handling. | No | Prestwick chemical library of 1120 approved drugs | Not specified | Senescence-associated-β-galactosidase activity via ImaGene Green™ C12FDG lacZ Gene Expression Kit. Autophagy levels via LC3 reporter. Imaged with Operetta® High Content Screening system. |

| Shi et al. (2019) 11 | Murine chondrogenic cell line | 96-well format. Cells seeded in monolayer and molecules added to medium. | No | Library of 2320 natural and synthetic small compounds (10 μM). BNTA hit. | 5 days | Alcian Blue stain for proteoglycans assessed via light microscopy |

ASC = adipose-derived stem cell. BMSC = bone marrow stromal cell. ECM = extracellular matrix. ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. HA = hyaluronic acid. ICC = immunocytochemistry. PEG = poly(ethytlene glycol). PEO = poly(ethylene oxide). PASMC = pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. RGD = Arg-Gly-Asp tri-peptide

The simplest 2D models comprise monolayer cell culture, with the addition of a molecule/molecular library to the culture medium and measurement of a simple output via a microplate reader or microscope. Choi et al. 33 wished to demonstrate that they could create a synthetic sulphonamide analogue of a protein kinase A inhibitor (the commercially available H-89), which had previously been shown to induce chondrogenic differentiation in rodent BMSC 34. In this model, human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) were seeded into individual 60 mm dishes and cultured for 11 days with their in-house library of H-89 analogues. Aggrecan protein expression was subsequently assessed via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and “compound 6” was identified as a novel chondrogenic inducer 33. Though this system proved effective on a small-scale with a known target, it does not lend itself to HTS and would be too laborious for a larger number of candidate molecules. Nevertheless, these simple screening systems are widely adopted in research institutes and undoubtedly have their place. Scaling up of such systems, with the use of multi-well plates and multichannel pipettes (or even robotic liquid handling systems) is also fairly commonplace. Shi et al. 11 managed to screen 2320 natural and synthetic small compounds using a 96-well format seeded with a murine chondrogenic cell line. Again, cells were seeded in monolayer and molecules were added to the growth medium; proteoglycan production was assessed after 5 days via Alcian Blue staining and simple light microscopy. Though labour-intensive, this initial screening represents the limit of automation that many labs can achieve and allowed for a rapid narrowing of the number of candidate compounds, which were interrogated with increasingly complex and rigorous methods until BNTA was identified as a potential therapeutic agent for OA.

Despite initial excitement following the discovery of the molecule described above, none currently have market approval for the treatment of OA. Licofelone completed phase III clinical trials over a decade ago but, owing inconclusive results, was never submitted for regulatory approval 35,36. Trials with Balicatib were terminated after completion of phase II when an increased risk of cardiovascular events was reported in patients receiving the drug 37. KGN is currently undergoing phase II studies for the treatment of OA, with results anticipated in late 2021 38(p2). SM04690, a Wnt pathway inhibitor whose chondroinductive properties were again identified with the aid of HTS 10, is now in phase III clinical trials for the treatment of knee OA 39.

Advanced 2D screening platforms

Some groups have sought to increase the physiological relevance of their 2D screening systems by introducing an extra level of complexity. One study reported the use of a microfluidics device to determine the optimum concentration of their candidate drug resveratrol for the proliferation of primary rodent chondrocytes 8. As a system for optimising the dose of a drug with known benefits, this technique offers some useful insight; the authors presumably wished to increase proliferation of terminally differentiated chondrocytes for subsequent use in their animal model. However, proliferation is not the primary desirable outcome of a chondroinductive molecule and may come at the expense of cartilaginous matrix production 40. Therefore, for a chondrogenic screening model, alternative outputs such as sGAG production would have been more relevant. Gradients do have well established physiological relevance, however 41, and the use of microfluidics to create them can be of great benefit in screening systems. However, production of these (usually) bespoke systems is costly, time-consuming, and rarely compatible with commercially available liquid handling systems, thus presenting barriers to scale-up.

Another means of increasing the physiological relevance of 2D screening platforms is to introduce extracellular matrix (ECM)-mimicking chemical and mechanical properties. A number of these systems, though designed for other tissue types, could easily be adapted for cartilage screening models 42,43. Others have sought to bridge the gap between 2D and 3D screening platforms by creating hydrogels with tuneable chemical and mechanical properties onto which cells can be seeded 7,44,45 To date this has not been attempted for cartilage screening models, but would be a useful addition to protocols as chondrocytes are known to be mechanoresponsive 46.

Limitations of 2D platforms

2D screening systems offer numerous advantages and will undoubtedly continue to prove useful in both research environments the pharmaceutical industry. However, there are a number of well-documented limitations to these systems and candidate molecules, which initially appear promising, often fail to perform in vivo. Cells cultured in 3D are exposed to a microenvironment which more closely mimics the native tissue from which they are derived – in addition to the obvious geometrical parallels, they are exposed to paracrine signals from neighbouring cells, more comparable mechanical properties, and concentration gradients of growth factors, cytokines, nutrition and oxygen. It has also been well-documented in tumour models that cells cultured in 3D conditions demonstrate reduced drug sensitivity and require dosages that may be orders of magnitude higher than their monolayer counterparts 47–49. ECM sequestering of soluble factors 50 and reduced mass transfer to the deeper regions of constructs 47 are likely to account for this observation. Whatever the mechanism, it is clear that dosage ranges determined from 2D screening platforms are unlikely to prove effective in vivo. Additionally, 2D models do not allow for the application of physiologically relevant mechanical stimulation during the culture period or for the use of changes in mechanical properties as an output measure. Given that cartilage is adept at withstanding a relentlessly harsh dynamic environment 51, these are important considerations for anyone seeking to create a reliable in vitro model.

3D screening platforms

3D models can reflect the spatial relationships between cells at different stages of differentiation in their extracellular matrix and more closely represent systems and functions in the human body 52. A recent review of the benefits of 3D culture concluded that it generally results in improved differentiation, protein/gene expression, viability and drug susceptibility compared to monolayer culture; and when it comes to translating the findings of in vitro work to in vivo applications, 3D systems invariably perform better 53. Cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions change dramatically when cells are taken from their native tissue to a 2D culture system where they are forced to adapt to a flat, smooth and extremely rigid surface; therefore, it is no surprise that effects observed under these conditions are often lost upon transfer to a more physiologically relevant microenvironment 54.

Given that monolayer screening platforms often fail to predict efficacy in vivo, a number of groups have sought to develop systems which recapitulate some of the tissue’s native architecture while allowing for large-scale and rapid outcomes (table 2). This is no trivial task and, while many of these models are unlikely to be adopted by the pharmaceutical industry without further development, they have proven invaluable in research settings and offer a way forward in terms of reducing the need for animal models. The number of models designed to probe for potential cartilage therapies/inducers of differentiation are relatively small, but many of the systems designed for other tissues could easily be adapted for chondrogenic applications.

Table 2. 3D screening platforms.

| Authors | Cell type(s) | Model | Tissue type | Molecules/parameters tested | Culture period | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. (2008) 78 | Bovine BMSC | Spheroids. 384-well format via microplate filling system. | Chondrogenic | NINDS library of 1040 compounds | 7 days | Automated, in-well DNA and sGAG assays. |

| Friedrich et al. (2009) 85 | Tumour cell lines | Spheroids. 96-well format via semi-automated multi-channel pipetting system. | Tumour | N/A | 7 days | Spheroid growth and integrity via semi-automated microscopy. Proliferation via thymidine incorporation assay. |

| Willard et al. (2014) 79 | iPSC with COL2A1reporter system | Spheroids. 96-well format. | Chondrogenic | IL-4, TIMP-3, NS-398, SC-514, GM-6001 | 3 days | Cell number, elastic modulus change, GAG loss, production of MMPs, prostaglandin and NO. |

| Atefi et al. (2014) 86 | A431.H9 skin cancer cell line | Spheroids. 96-well format via robotic liquid handler and two-phase PEG/dextran system | Tumour | Cisplatin and paclitaxel | 7 days | Viability and standard microplate reader-based assays. |

| Aijan and Garrell (2014) 84 | Murine BMSC, colorectal cancer line, human fibroblasts | Spheroids. Hanging drop culture via digital microfluidics and automated liquid handling system. | Tumour | Insulin and irinotecan (cancer line only) | 4 days | Viability and spheroid size via confocal microscopy. |

| Beachley et al. (2015) 87 | Human cancer cell line | Spheroids. Hanging drop culture. | Tumour | ECM digests from different anatomical locations | 11 days | Potential for metabolic assays, single-cell analysis/sorting and gene expression analysis. |

| Dennis et al. (2020) 80 | ATDC5 chondrogenic cell line | Spheroids. 96-well format. | Chondrogenic | 15 vitamins and minerals | 21 days | Collagen type II promoter expression via luciferase reporter. |

| Greco et al. (2011) 77 | C-28/I2 chondrogenic cell line | Micromass. 24-well format. | Chondrogenic | Prednisolone and naproxen | 5 days | sGAG assay and gene expression analysis (anabolic/catabolic genes). |

| Mohanraj et al. (2014) 81 | Bovine chondrocytes | Micromass. 96-well format. Cultured for 14-16 weeks before injurious compression applied. Post-traumatic OA model. | Chondrogenic | NAC, ZVF, Polaxamer 188 | 5 days | DNA, sGAG and LIVE/DEAD assays. Alcian Blue staining for sGAG. |

| Parreno et al. (2018) 82 | Bovine chondrocytes (dedifferentiated) | Micromass. 96-well format. Cells seeded onto TCP, confined inside agarose tubes with 3 mm diameter. Combinatorial screen of 3 growth factors. | Chondrogenic | TGFß-1, FGF2 and FGF18 | 14 days | Alcian Blue staining for proteoglycan accumulation. Eluted dye quantified via microplate reader. |

| Ranga et al. (2014) 94 | Murine ESC with OCT4 reporter system | Combinatorial hydrogels. 384-well format. Cells encapsulated in multifactorial PEGbased gels via robotic liquid handling system. | N/A | Mechanical properties, degradability, various proteins and soluble factors | 5 days | Colony size, LIVE/DEAD and OCT4 (GFP) expression via automated microscopy. Indentation testing, flow cytometry, PCR. |

| Dolatshahi-Pirouz et al. (2014) 95 | Human BMSC | Combinatorial hydrogels. Cells encapsulated in GelMA with different combinations of proteins and microgels printed onto glass slides via robotic spotter. | Osteogenic | Fibronectin, laminin, osteocalcin, BMP2 and BMP5 | 7 or 14 days | Osteogenic model - ALP assay, mechanical testing and mineralisation. OPN expression and Alizarin Red staining via confocal microscopy. |

| Mohanraj et al. (2014) 93 | Bovine BMSC | Hydrogels. Cell-laden hyaluronic acid set between 2 glass plates and cylindrical constructs punched out. | Chondrogenic | TNF-α | 6 days | DNA and sGAG assays. Griess assay for NO production and mechanical testing. |

| Li et al. (2017) 101 | Rabbit articular chondrocytes | Hydrogels. Cells encapsulated in Matrigel and loaded into perfusion microfluidic device. Combinatorial screen of 2 growth factors. | Chondrogenic | IGF-1 and FGF2 | 2 weeks | Collagen type II expression via ICF. |

| Galuzzi et al. (2018) 96 | Human nasal chondrocytes | Multiple: alginate beads, decellularised cartilage, spheroids, silk/alginate microcarriers. | Chondrogenic | IL-1ß | 15 days | GAG release into medium and metabolic activity. |

| Yeung et al. (2018) 97 | Human BMSC | Hydrogels. Cells encapsulated in collagen droplets then inserted into human osteochondral grafts. | Chondrogenic | GM6601 | 4 and 8 weeks | Collagen type II, MMP13 and ADAMTS-5 via ELISA. Histology and IHC. |

| Vega et al. (2018) 100 | Human BMSC | Combinatorial hydrogels. Cells encapsulated in HA gels with a gradient of tethered peptides. | Chondrogenic | His-Ala-Val motif and RGD | 7 days | SOX9 and aggrecan expression via ICF and single cell confocal imaging. Mechanical properties via atomic force microscopy. |

| Kolb et al. (2019) 103 | HEK-IL4-YFP reporter cell line | Hydrogels. Combinatorial cell aggregates encapsulated in A) non-degradable PEG followed by B) degradable, protein-functionalised PEG. Microfluidics system. | N/A | IL4, IGF1, BMP2, BMP4, ActA, Wnt3a | 8 days | Protein expression via YFP reporter and plate reader. Barcoded RNA sequencing. |

| Lee et al. (2020) 98 | Human BMSC | Combinatorial hydrogels. Cells encapsulated in PEG/alginate gels of different ratios with and without RGD and/or TGF-ß1. 3D printed onto 288 gel array | Chondrogenic | Different compressive strains and TGF-ß1 concentrations | 7 and 21 days | LIVE/DEAD assay, GAG deposition and degradation. ICF for collagen type II, aggrecan and Runx2 via confocal microscopy. Mechanical testing. |

| Occhetta et al. (2019) 113 | Human articular chondrocytes | Cartilage-on-a-chip. Cell-laden PEG hydrogels cast into PDMS microchambers at branched ends of moulds with central channel for medium exchange. Compression applied to create OA model. | Chondrogenic | Dexamethasone, IL-1Ra, rapamycin, celecoxib, HYADD 4 and HA | 24 days | DNA and sGAG assay. Gene expression (panel of genes). ICF for aggrecan, collagen types I and II, MMP-13 and DIPEN. MMP-13 release via assay kit. |

| Rosser et al. (2019) 112 | Equine chondrocytes | Cartilage-on-a-chip, microfluidic device. Fibrin-encapsulated cells pipetted into semicircular chambers. Medium forced past flat part of semicircle only, to generate jointmimicking cyclic shear stress and concentration gradients. | Chondrogenic | TNF-α and IL-1ß | 7 and 21 days | LIVE/DEAD and metabolic activity assays. Gene expression analysis for COL2A1, ACAN, SOX9. Histology and IHC. |

| Lin et al. (2019) 114 | iPSC | Osteochondral tissue chip. Gelatin-encapsulated in gelatin pipetted into custom inserts. Dual flow bioreactor delivers two types of media (top and bottom). | Chondrogenic and osteogenic | Celecoxib | 35 days | Gene expression analysis (anabolic/chondrogenic, catabolic and inflammatory markers). |

| Peck et al. (2017) 115 | Porcine chondrocytes, synovial cell line and macrophages (activated THP-1 cells) | Scaffold free. 24-well plate format. Chondrocyte-laden gelatin microspheres encapsulated in alginate. Gelatin dissolved to leave cells in cavities. After 35 days alginate removed and synovial cells added to remaining tissue nodules. Macrophages added the following day. | Chondrogenic | Celecoxib | 7 days (triculture) | Gene expression analysis (apoptotic, anabolic, inflammatory, chondrogenic). Histology for GAGs. Proliferation. |

ALP = alkaline phosphatase. BMSC = bone marrow stromal cells. ECM = extracellular matrix. ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. ESC = embryonicstem cell. GAG = glycosaminoglycan. GelMA = gelatin methacrylate. GFP = green fluorescent protein. HA = hyaluronic acid. HEK = human embryonic kidney. ICF = immunocytofluorescence. ICH = immunohistochemistry. IL4 = interleukin 4. iPSC = induced pluripotent stem cell. MMP = matrix metalloproteinase. NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NO = nitrous oxide. OA = osteoarthritis. PDMS = polydimethylsiloxane. PEG = poly(ethylene glycol). PCR = polymerase chain reaction. RGD = Arg-Gly-Asp tri-peptide. sGAG = sulphated glycosaminoglycan. YFP = yellow fluorescent protein.

Disease models are often adopted for the screening of potential novel therapeutic molecules, as changes in pathogenesis are relatively straightforward to detect via histology or gene/protein expression analysis. In vitro OA models can be chemically induced via cytokines or collagenases 55,56, mechanically induced with the application of injurious strains 55,56, or generated from chondrocytes donated by OA patients (with obvious limitations) 57. Mechanically induced models, analogous to post-traumatic OA, are a useful tool but do not offer much insight into the earlier stages of pathology, whereas chemically-induced models require a combination of factors at a range of carefully controlled concentrations and exposure times to be truly representative 56. There are a large number of genetic risk factors associated with OA susceptibility including interleukin 1 beta (IL-1ß), hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS2), lubricin, matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13) and connexion 43 (CX43) 21. CRISPR gene editing technology has been used to ablate expression of these alleles for tissue engineering purposes 22,25,58–60, but could be used to increase the expression of disease-linked alleles in order to create precision cellular models 61 which allow interrogation of the earlier stages of OA and identification of novel effectors of early pathogenesis.

High-throughput production of 3D cartilage models

Despite the many advantages of 3D culture, it is more labour-intensive and, in the case of spheroid production, requires large cell numbers. This is especially problematic for high-throughput applications where speed is paramount and large numbers of uniform constructs are required. A number of groups have developed high-throughput systems for generating cartilage microaggregates, which are readily compatible with standard micro-well plates 62–65. Conical microwells can be fabricated from non-adherent materials such as agarose 62,64 or PDMS 63 with the aid of a rigid negative template and then punched into discs which fit easily into multi-well tissue culture plates. Primary chondrocytes 62,64 and BMSC 63 seeded into these micro-wells have been shown to perform at least as well as traditional spheroids in terms of chondrogenic matrix production and gene expression, and far better than monolayer culture where dedifferentiation to a fibroblastic phenotype is usually observed. In addition, the number of cells required to produce these micro-aggregates ranges from 5000 63 down to 100 62 – a significant reduction from the 200,000 minimum required to form larger pellets. One issue with these microscale cultures is the potential for aggregates to move out of their wells during medium changes. Futrega et al. overcame this problem by placing a nylon mesh over their PDMS discs, the pores of which were sufficient to admit single cells during seeding but small enough to prevent the loss of the multicellular aggregates that subsequently formed 63. Another group generated large numbers of columnar cartilage aggregates, by culturing and differentiating adipose-derived stem cells inside the PLA-coated pores of poly(L-glutamic acid)/adipic acid hydrogels 66. Cells, preferentially bound to the PLA, gradually released thiol-containing molecules, which cleaved the PLA and enabled them to detach and formation aggregates.

Although spheroids lend themselves well to scaled-up fabrication, hydrogels allow for better mass transfer and can mimic the endogenous ECM more closely; therefore, a high-throughput system for producing cartilaginous hydrogels may be more appropriate for screening purposes. Witte et al. recently developed a microfluidics system for the rapid production of cell-laden alginate-fibronectin microgels 65. Good viability, proliferation and production of chondrogenic markers were reported in both articular chondrocytes and BMSC encapsulated in the gels, however, as no monolayer or standard 3D controls were included, it is difficult to compare the performance of this model with lower throughput systems.

High density spheroid and micromass culture

For cartilage tissue engineering, spheroids (also referred to as pellets), being the most effective in terms of chondrogenic matrix production, are the gold standard. Unsurprisingly, therefore, this model has proven popular as a 3D screening platform for potential joint therapies and chondrogenic differentiation. Given their tumour-mimicking morphology, spheroids are also popular in cancer drug screening 67,68. These self-assembling, cell-dense constructs are compatible with high-throughput due to the relative ease with which they can be formed in round bottom multi-well plates 69. One consequence of spheroid culture (particularly those exceeding 500 μm diameters 70,71) is that nutrients and waste products are not able to diffuse evenly throughout the compact cell/ECM structure 72. Though this often leads to compromised viability within the core of tumour spheroids 71–73, hypoxic conditions (which mimic native articular cartilage) have actually been shown improve the expression of cartilage-specific markers in chondrogenic spheroids 74–76.

The most basic (and arguably most scalable) attempts at creating 3D chondrogenic screening platforms have utilised high density culture of cell lines in multi-well plates. In an early example, Greco et al. added anabolic TGFß or catabolic IL-1ß to micromasses and investigated the effects of two anti-inflammatory drugs on sGAG accumulation and the expression of anabolic/catabolic genes 77. Although the outputs of this system were fairly low-throughput, other groups have increased the speed of data acquisition from standard sGAG and gene expression assays by performing them in situ, sometimes with the aid of liquid handling systems 78,79.

Fluorescent reporter systems have also proven useful in spheroid-based platforms. Willard et al. used TGFß-3 and murine tail fibroblast-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), which had been pre-selected for COL2A1 expression based on a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter system, to make pellets in a 96-well format 79. Once formed, pellets were challenged with pro-inflammatory interleukin-1α (IL-1α) to create a disease model. Five candidate OA drugs were incorporated into the model and sGAG loss to the medium was assessed via 1,9-Dimethyl-Methylene Blue (DMMB) assays, performed in situ in standard microplates. The relatively simple outputs of this platform lend themselves to scale-up and high-throughput, which makes it a promising alternative to standard 2D systems. However, the model takes over 5 weeks to set up and involves a degree of handling, wherein pellets are transferred to 96-well plates, which significantly reduces its appeal. In a simpler iteration, Dennis et al. recently used a fluorescent reporter system to screen for vitamins and minerals with the potential to enhance chondrogenic differentiation 80. The use of a chondrogenic cell line, transformed with a collagen type II promoter-driven reporter system, provided a rapid output metric and facilitated the combinatorial screening of a large number of small molecules with anabolic potential.

Post-traumatic OA models can also be generated from spheroids with relative ease. Mohanraj et al. used a high-throughput device to mechanically challenge their constructs by applying injurious compressive force 81. After the application of three potential therapeutic compounds, sGAG level was determined with DMMB assays and Alcian Blue staining. Unfortunately the outputs for this platform are laborious and the initial culture period is particularly lengthy; the only high-throughput aspect here is the application of injurious compressive force using an indentation device compatible with standard multi-well plates. Alcian Blue staining is tried and tested method of assessing the anabolic effects of compounds on chondrocytes, however, and can easily be adapted for high-throughput systems. Parreno et al. 82 eluted the dye from their 96-well format screening platform and measured it spectrophotometrically via a microplate reader. Liquid handling systems, which are compatible with standard well-plates, could further increase the throughput of these models.

Spheroids recapitulate the key features of solid tumours, including geometry and limited mass transfer to the core region 83. As such they have been successfully adopted in a number of screening platforms for potential cancer treatments 84–88. Creation of spheroids from cancer cell lines via robotic liquid handling/automated pipetting systems in non-adherent 96-well 85,86 or 384-well 88 plates is a relatively straightforward and rapid process and such equipment, already heavily utilised by the pharmaceutical industry, is becoming more commonplace in research laboratories. These platforms are used to screen large libraries of potential chemotherapeutics and, where cell death/stunted growth is the primary goal, output measurements are easily generated with simple assays and microscopy techniques. Assessing the effects of small molecules on cartilage development or degradation requires more complexity in this regard, but nonetheless the design of these models could prove useful for this application. One group developed a two-phase system wherein cells were confined to a nanolitre volume of dextran via droplet immersion into a well of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) solution and subsequently formed micro-aggregates 86,88. This system is completely automated, compatible with 96- 86 and 384-well 88 plates and can be adapted to include co-culture of multiple cell types, which would be an interesting avenue for models of cartilage given that endogenous tissue is in close proximity to the subchondral bone and its population of progenitor cells. Additionally, this model demonstrated that the effective dosage range of two commonly-used anti-cancer drugs was significantly higher for spheroids than for cells cultured in monolayer, reinforcing the importance of 3D platforms which recapitulate the native ECM. Hanging droplets can also be used to produce large numbers of spheroids for screening purposes, either with the use of microfluidic systems 84 or microarray spotters 87. However, these models usually require a degree of handling and/or the application of bespoke equipment, significantly reducing their throughput.

Lack of homogeneity in both size and shape of spheroids, is a common issue which can limit hinder the reproducibility of data for drug screening purposes 89. The use of conical multi-well plates for generation of the constructs and the subsequent application of imaging software to select only the most spherical has been suggested by one group as the best means of eliminating variability 89. Another study showed that spheroids generated from adipose derived stromal cells in non-adhesive hydrogel micro-moulds demonstrated homogeneous size and shape, while those formed using primary chondrocytes did not 90. Therefore, spheroid uniformity is an important consideration for any groups seeking to utilise this model for HTS systems.

Another factor reducing the appeal of spheroids for screening purposes is the necessity for high cell numbers, which poses a significant barrier to scale-up. Huang et al. were able to adapt this model to an impressive 384-well format, using just 10,000 bovine BMSC per pellet, with the aid of an automated liquid dispensing device and a Breathe-Easy® sealing membrane to eliminate the requirement for medium changes 78. Automated in-well digestion and DNA/sGAG assays were the primary output measures for this system, rendering it a truly high-throughput 3D screening platform.

In summary, spheroids are a sound 3D model for cartilage tissue engineering, which mimic the cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions of early development and have been shown enhance chondrogenic differentiation in vitro 91. In addition, their relatively straightforward production and proven scalability mean they offer a promising alternative to existing 2D drug screening platforms. A spheroid-based screening platform, which produces uniform structures from a plentiful cell-source and utilises some of the rapid output measures outlined above, could offer a realistic alternative to the 2D platforms currently favoured by the pharmaceutical industry.

Hydrogels

Mature cartilage is a highly structured, viscoelastic material and markedly acellular compared to most tissues 51,91,92. For these reasons a large number of studies have sought to create alternative 3D models of cartilage from hydrogels, which mimic some of the tissue’s key structural properties. In terms of predicting effective dosage ranges, there is also some evidence that these models are more effective than pellets; one study showed that oral cavity cancer cell-laden alginate displayed a chemo-sensitivity comparable to native tumour tissue, whereas cell-dense spheroids required significantly higher doses 48.

A particular advantage of hydrogels is that their cell densities can be carefully controlled, which could be especially useful for models of cell-sparse tissues like articular cartilage. Simple hydrogel systems can easily be utilised for drug screening purposes 93 and rapid production of large numbers of cell-laden constructs has been demonstrated via droplet formation 94–97 or 3D printing 98. Major drawbacks of droplet-based hydrogel systems, however, are that constructs are cultured together in one volume of medium and a high degree of liquid handling is required for processing. Large combinatorial hydrogels with gradients of tethered chemical ligands have also been used in high-throughput screening platforms 99,100, but again constructs are cultured in a shared media pool, meaning that paracrine effects from neighbouring regions cannot be ruled out. To overcome this limitation, high-throughput microgel systems with discrete wells have also been utilised; although generation of these models requires access to expensive specialist equipment 94.

Microfluidic devices have been used to culture hydrogels in dynamic conditions, thus creating shear forces and concentration gradients which help to recapitulate the endogenous environment. Li et al. 101 reported the use of such a device to screen the combinatorial effects of two growth factors on type II collagen production in Matrigel-encapsulated chondrocytes. Immunostaining of the entire polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chip, with the aid of image analysis software, allowed for rapid data acquisition. Accommodating just 3 culture chambers, this platform cannot be deemed high-throughput, but a scaled-up version of this technology could prove invaluable in determining the optimal concentration of small molecules with anabolic potential.

Recently the benefits of spheroids and hydrogels have been combined to create hybrid models, whereby small cell aggregates (as opposed to single cells) are encapsulated within hydrogels 102. Kolb et al. developed a complex model in which aggregates of recombinant protein-expressing cell lines were co-encapsulated in PEG 103. Used in conjunction with a reporter cell line that gives rapid outputs, this combinatorial microgel platform certainly lends itself to high-throughput systems and could easily be adapted for cartilage screening. However, initial generation of multiple protein-expressing cell lines is a lengthy process compared to standard screening methods and may deter interest from the pharmaceutical industry.

Organoids

Organoids are similar to spheroids, but are generally defined by three key features: they must be formed from multiple cell types or stages, must have some aspect or function of the tissue they are modelling and must develop following the same basic patterning 104,105. There are well-described organoid models for tissues such as brain 106, stomach 107 and liver 108 which fulfil all of these criteria. However, cartilage “organoids” are often simple spheroids composed of just one cell type. The distinction between spheroids and organoids is a difficult one to make with hyaline cartilage, which naturally comprises mainly one cell type and is a tissue (albeit a highly structured zonal one) rather than an organ, such as the brain. Though cartilaginous spheroids are sometimes referred to as “organoids”, for the purposes of this review the term “organoid” will be reserved for tissue with more complexity. Few attempts have been made to culture cartilage organoids with structures, cell densities and niche properties more characteristic of the native tissue than the high density pellet culture described above. In one example, however, O’Connor et al. created an osteochondral organoid, by using TGFß-3 and bone morphogenetic protein 2 to mirror endochondral ossification in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) micromasses 109. Comprising a cartilaginous core with a calcified outer ring, this model could prove very useful for the screening of potential modifiers of OA, which is after all a disease of the entire joint, including the subchondral bone 110,111. Although the 73-day culture period is not ideally suited to high-throughput processes, the expansion capacity of iPSC is a real advantage in this regard. Furthermore, the use of these cells presents greater opportunity for conducting patient- and/or disease-specific drug screening.

Cartilage-on-a-chip technology

Organ-on-a-chip technology may be a promising alternative approach to the creation of 3D cartilage models, as it lends itself to the formation of stratified structures. As screening platforms, these niche-mimicking structures are also more likely to give meaningful results and reduce the risk of futile investment in fruitless products.

Rosser et al. recently described a system in which fibrin-encapsulated chondrocytes were loaded into 3 mm semi-circular tissue chambers embedded into PDMS slabs 112. A microfluidics system was used to drive medium past only the flat side of the chamber, thus creating cyclic shear forces and concentration gradients which mimicked the articular surface and underlying, avascular tissue. Cells in this system retained their rounded morphology and chondrogenic gene expression, unlike their monolayer counterparts. Incorporation of pro-inflammatory cytokines to the system demonstrated its potential as a screening platform, but output measures were relatively low-throughput. In a similar model, Ochetta et al. went a step further by incorporating a sub-chamber into their PDMS stamp to enable the application of confined compression, thereby generating the crucial mechanical stimulus to which the joint is subject 113. Chondrocytes, encapsulated in PEG hydrogels, were loaded into the micro-chambers and high compressive loads were applied in order mimic OA pathogenesis. A range of commonly-used anti-inflammatory and anti-catabolic drugs were added to the medium for 3 days before tissue integrity was assessed with sGAG and matrix metalloproteinase 13 assays. This model is especially versatile, as compressive loads can be adjusted to recapitulate normal joint conditions for the purpose of screening potential chondrogenic/anabolic compounds. Both of these cartilage-on-a-chip systems utilise microfluidics technology to rapidly produce potentially large numbers of chondrocyte-laden hydrogel constructs, which mimic not only the mechanical properties of articular cartilage but also its physiological gradients and dynamic environment. One drawback to this technology is the requirement for custom moulds which are not compatible with standard microplate readers and, therefore, not amenable to high-throughput assay-based outcomes. However, the PDMS stamps described here can be fabricated to match the dimensions of standard microscope slides, thereby allowing for the use of automated microscopy as a means of increasing the throughput of these systems.

Neither of the cartilage-on-a-chip models described above attempted to recreate the zonal compartmentalisation of articular cartilage, nor was inclusion of cells at different stages of differentiation considered. Lin et al. 114 addressed this issue by using iPSC to create an osteochondral “tissue chip”. iPSC-derived progenitors were encapsulated in gelatin and cultured in a dual flow bioreactor, whereby cells at the base of the construct were exposed to osteogenic cues and those at the top to chondrogenic cues, with a natural gradient across the depth of the gel akin to the native environment (figure 1E). After 28 days of culture, good expression of chondrogenic and osteogenic makers were seen in the upper and lower regions of the chip respectively; induction of an OA disease phenotype was then achieved with the addition of interleukin-1ß (IL-1ß) to the medium for 7 days. By incorporating progenitor cells, multiple tissue types, dynamic conditions and tuneable concentration gradients, this model recapitulates the endogenous joint environment more closely than the vast majority described to date. To demonstrate its potential as a screening platform, the FDA-approved drug Celecoxib was administered to the system, resulting in significant decreases in expression of catabolic and inflammatory factors. This versatile model also has the potential to screen novel inducers of anabolic response in cartilage tissue, simply by omitting the IL-1ß culture period. The authors do not comment on the capacity of this system for generating and maintaining large numbers of constructs, and the output measures adopted (primarily gene expression analysis) are not amenable to high-throughput. As a system for optimising the concentration of small molecules identified by other screening platforms, however, this model certainly holds great promise.

Outlook for 3D screening platforms

3D models, which more accurately recapitulate mature cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions and display patterns of spatial gene and protein expression more akin to the native tissue environment 52, have gained popularity in recent years. In addition, a promising number of studies have demonstrated that high-throughput production of 3D cartilage models is possible and that rapid outputs are achievable with the aid of technology such as robotic liquid handling systems. Access to such technology poses no barrier for large pharmaceutical companies and is becoming more commonplace in smaller labs 9,10,43,84,94,95 Nonetheless, 3D models require longer culture periods, are more labour-intensive and can lack the requisite reproducibility for scale up 52. Models incorporating the full cascade of chondrocyte differentiation present in vivo are also lacking; a platform with such complexity might more accurately predict in vivo drug response, but would undoubtedly require greater investment of both time and funds. For smaller labs, where there is less emphasis on high-throughput, 3D platforms are widely utilised for small-scale screening and optimisation of established anabolic/catabolic agents. Complex models such as organoids are unlikely to be adopted by pharmaceutical companies in the near future for the screening of vast chemical libraries, however, large-scale spheroid culture 78 and high-throughput hydrogel production 94 offer a realistic alternatives to the inadequate 2D systems currently employed.

Conclusion

High-throughput screening platforms are essential for identifying small molecules with the potential to modify both chondrogenic differentiation and cartilage catabolic processes. 2D systems, which are economical, compatible with robotic liquid handling technology and offer rapid output metrics are currently favoured by the pharmaceutical industry. A number of potential disease-modifying OA drugs have been discovered in this way, as have molecules such as KGN, which hold great promise for cartilage tissue engineering. However, 2D culture systems do not reliably represent in vivo conditions and often fail to predict efficacy in subsequent animal models. 3D models recapitulate the cell niche more closely, produce superior cartilage in vitro and show differential dose responses to disease modifying drugs. A range of 3D models (including spheroids, hydrogels and organ-on-a-chip) have been adapted to create screening platforms for cartilage and many other tissue types. Drawbacks of these systems include longer culture periods, necessity for higher cell numbers, increased handling and increased costs. However, in order to reduce the requirement for animal models and to limit wasted investment in ineffective drugs, it is essential that research institutes and the pharmaceutical industry alike move towards the use of effective 3D models for screening purposes and design new approaches which encapsulate the complexity of zonal structures and cell types within the cartilage matrix. If 3D platforms are to be adopted on a large-scale for pharmaceutical drug screening, economic considerations must be carefully balanced with the need for outcomes which accurately predict in vivo response. Initial investment in systems with more physiological relevance could ultimately mitigate the fruitless development of drugs which fail to obtain market approval.

Impact statement.

Currently, the use of 2D screening platforms in drug discovery is common practice. However, these systems often fail to predict efficacy in vivo, as they do not accurately represent the complexity of the native 3D environment. This article describes existing 2D and 3D high throughput systems used to identify small molecules for OA treatment or in vitro chondrogenic differentiation, and suggests ways to improve the efficacy of these systems based on the most recent research.

Acknowledgements

Funding statement

The authors would like to thank the UK Regenerative Medicine Platform and the Medical Research Council for provision of funding.

Footnotes

Author(s’) disclosure statement(s)

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Contributor Information

Nicola C Foster, Healthcare Technologies Institute, Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, B15 2TH.

Nicole M Hall, Email: 2255867H@student.gla.ac.uk, Division of Biomedical Engineering, James Watt School of Engineering, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom.

Alicia J El Haj, Email: A.ElHaj@bham.ac.uk, Healthcare Technologies Institute, Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, B15 2TH.

References

- 1.Grogan SP, D’Lima DD. Joint aging and chondrocyte cell death. Int J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;5(2):199–214. doi: 10.2217/ijr.10.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamimi NAM, Ellis P. Drug Development: From Concept to Marketing! Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;113(3):c125–c131. doi: 10.1159/000232592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo B, Field MJ. The Pathway from Idea to Regulatory Approval: Examples for Drug Development. National Academies Press; US: 2009. [Accessed September 23, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo KW-H, Jiang T, Gagnon KA, Nelson C, Laurencin CT. Small Molecule based Musculoskeletal Regenerative Engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2014;32(2):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong E, Reddi AH. Dedifferentiation and redifferentiation of articular chondrocytes from surface and middle zones: changes in microRNAs-221/-222, -140, and -143/145 expression. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19(7–8):1015–1022. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlier E, Deroyer C, Ciregia F, et al. Chondrocyte dedifferentiation and osteoarthritis (OA) Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;165:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma S, Floren M, Ding Y, Stenmark KR, Tan W, Bryant SJ. A photoclickable peptide microarray platform for facile and rapid screening of 3-D tissue microenvironments. Biomaterials. 2017;143:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ming L, Zhipeng Y, Fei Y, et al. Microfluidic-based screening of resveratrol and drug-loading PLA/Gelatine nano-scaffold for the repair of cartilage defect. Artif Cells Nanomedicine Biotechnol. 2018;46(1):336–346. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1423498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nogueira-Recalde U, Lorenzo-Gómez I, Blanco FJ, et al. Fibrates as drugs with senolytic and autophagic activity for osteoarthritis therapy. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:588–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshmukh V, Hu H, Barroga C, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the Wnt pathway (SM04690) as a potential disease modifying agent for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(1):18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y, Hu X, Cheng J, et al. A small molecule promotes cartilage extracellular matrix generation and inhibits osteoarthritis development. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1914. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09839-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le BQ, Fernandes H, Bouten CVC, Karperien M, van Blitterswijk C, de Boer J. High-Throughput Screening Assay for the Identification of Compounds Enhancing Collagenous Extracellular Matrix Production by ATDC5 Cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2015;21(7):726–736. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2014.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238(1):265–272. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnstone B, Yoo JU. Autologous mesenchymal progenitor cells in articular cartilage repair. Clin Orthop. 1999;(367 Suppl):S156–162. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGonagle D, Baboolal TG, Jones E. Native joint-resident mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage repair in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(12):719–730. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yubo M, Yanyan L, Li L, Tao S, Bo L, Lin C. Clinical efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for osteoarthritis treatment: A meta-analysis. PloS One. 2017;12(4):e0175449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyndall A. Mesenchymal stem cell treatments in rheumatology—a glass half full? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(2):117–124. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somoza RA, Welter JF, Correa D, Caplan AI. Chondrogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Challenges and Unfulfilled Expectations. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2014;20(6):596–608. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilak F, Pferdehirt L, Ross AK, et al. Designer stem cells: Genome engineering and the next generation of cell-based therapies. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2019;37(6):1287–1293. doi: 10.1002/jor.24304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanikella AS, Hardy MJ, Frahs SM, et al. Emerging Gene-Editing Modalities for Osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17) doi: 10.3390/ijms21176046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu L, Hu Y, Song M, et al. Up-regulation of FOXD1 by YAP alleviates senescence and osteoarthritis. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(4):e3000201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren X, Hu B, Song M, et al. Maintenance of Nucleolar Homeostasis by CBX4 Alleviates Senescence and Osteoarthritis. Cell Rep. 2019;26(13):3643–3656.:e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez-Pinera P, Kocak DD, Vockley CM, et al. RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):973–976. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varela-Eirín M, Varela-Vázquez A, Guitián-Caamaño A, et al. Targeting of chondrocyte plasticity via connexin43 modulation attenuates cellular senescence and fosters a pro-regenerative environment in osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(12):1166. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laufer S. Discovery and development of ML3000. InflammoPharmacology. 2001;9(1):101–112. doi: 10.1163/156856001300248371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raynauld J-P, Martel-Pelletier J, Bias P, et al. Protective effects of licofelone, a 5-lipoxygenase and cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor, versus naproxen on cartilage loss in knee osteoarthritis: a first multicentre clinical trial using quantitative MRI. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):938–947. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.088732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brömme D, Lecaille F. Cathepsin K inhibitors for osteoporosis and potential off-target effects. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(5):585–600. doi: 10.1517/13543780902832661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson K, Zhu S, Tremblay MS, et al. A stem cell-based approach to cartilage repair. Science. 2012;336(6082):717–721. doi: 10.1126/science.1215157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Wang JH-C. Kartogenin induces cartilage-like tissue formation in tendon-bone junction. Bone Res. 2014;2 doi: 10.1038/boneres.2014.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spakova T, Plsikova J, Harvanova D, Lacko M, Stolfa S, Rosocha J. Influence of Kartogenin on Chondrogenic Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs in 2D Culture and in Co-Cultivation with OA Osteochondral Explant. Mol J Synth Chem Nat Prod Chem. 2018;23(1) doi: 10.3390/molecules23010181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu C, Li T, Yang Z, et al. Kartogenin Enhanced Chondrogenesis in Cocultures of Chondrocytes and Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2018;24(11–12):990–1000. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2017.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi E, Lee J, Lee S, et al. Potential therapeutic application of small molecule with sulfonamide for chondrogenic differentiation and articular cartilage repair. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26(20):5098–5102. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang K-C, Kim JY, Chang W, et al. Chemicals that modulate stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(21):7467–7471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802825105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer L, Hornig M, Pergola C, et al. The molecular mechanism of the inhibition by licofelone of the biosynthesis of 5-lipoxygenase products. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152(4):471–480. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvaro-Gracia JM. Licofelone—clinical update on a novel LOX/COX inhibitor for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2004;43(1):i21–i25. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latourte A, Kloppenburg M, Richette P. Emerging pharmaceutical therapies for osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. :1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00518-6. Published online October 29, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samumed LLC. A Phase 2, 52-Week, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Two Injections of SM04690 Injected in the Target Knee Joint of Moderately to Severely Symptomatic Osteoarthritis Subjects. 2020. [Accessed October 28, 2020]. clinicaltrials.gov; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03727022.

- 39.Tattory M. Samumed Announces Positive End-of-Phase 2 Meeting with FDA for SM04690 in Knee Osteoarthritis. :2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wuelling M, Vortkamp A. Chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Endocr Dev. 2011;21:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000328081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu D, Tong X, Trinh P, Yang F. Mimicking Cartilage Tissue Zonal Organization by Engineering Tissue-Scale Gradient Hydrogels as 3D Cell Niche. Tissue Eng Part A. 2018;24(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Floren M, Tan W. Three-Dimensional, Soft Neotissue Arrays as High Throughput Platforms for the Interrogation of Engineered Tissue Environments. Biomaterials. 2015;59:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gobaa S, Gayet RV, Lutolf MP. Artificial niche microarrays for identifying extrinsic cell-fate determinants. Methods Cell Biol. 2018;148:51–69. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rape AD, Zibinsky M, Murthy N, Kumar S. A synthetic hydrogel for the high-throughput study of cell-ECM interactions. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8129. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tong X, Jiang J, Zhu D, Yang F. Hydrogels with Dual Gradients of Mechanical and Biochemical Cues for Deciphering Cell-Niche Interactions. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2016;2(5):845–852. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Z, Li Y, Wang M, Zhao S, Zhao Z, Fang J. Mechanotransduction pathways in the regulation of cartilage chondrocyte homoeostasis. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(10):5408–5419. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kapałczyńska M, Kolenda T, Przybyła W, et al. 2D and 3D cell cultures – a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch Med Sci AMS. 2018;14(4):910–919. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.63743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsieh C-H, Chen Y-D, Huang S-F, Wang H-M, Wu M-H. The effect of primary cancer cell culture models on the results of drug chemosensitivity assays: the application of perfusion microbioreactor system as cell culture vessel. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:470283. doi: 10.1155/2015/470283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bulysheva AA, Bowlin GL, Petrova SP, Yeudall WA. Enhanced chemoresistance of squamous carcinoma cells grown in 3D cryogenic electrospun scaffolds. Biomed Mater Bristol Engl. 2013;8(5):055009. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/8/5/055009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(3):211–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foster NC, Henstock JR, Reinwald Y, El Haj AJ. Dynamic 3D culture: models of chondrogenesis and endochondral ossification. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today Rev. 2015;105(1):19–33. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kapałczyńska M, Kolenda T, Przybyłl W, et al. 2D and 3D Cell Cultures - A Comparison of Different Types of Cancer Cell Cultures. Arch Med Sci. 2016;14(4):910–919. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.63743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ravi M, Paramesh V, Kaviya SR, Anuradha E, Solomon FDP. 3D Cell Culture Systems: Advantages and Applications. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(1):16–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazzoleni G, Di Lorenzo D, Steimberg N. Modelling tissues in 3D: the next future of pharmaco-toxicology and food research? Genes Nutr. 2009;4(1):13–22. doi: 10.1007/s12263-008-0107-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cope PJ, Ourradi K, Li Y, Sharif M. Models of osteoarthritis: the good, the bad and the promising. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(2):230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson CI, Argyle DJ, Clements DN. In vitro models for the study of osteoarthritis. Vet J. 2016;209:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeung P, Cheng KH, Yan CH, Chan BP. Collagen microsphere based 3D culture system for human osteoarthritis chondrocytes (hOACs) Sci Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47946-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farhang N, Brunger JM, Stover JD, et al. * CRISPR-Based Epigenome Editing of Cytokine Receptors for the Promotion of Cell Survival and Tissue Deposition in Inflammatory Environments. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23(15–16):738–749. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2016.0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seidl CI, Fulga TA, Murphy CL. CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of MMP13 in human chondrocytes leads to significantly reduced levels of the metalloproteinase and enhanced type II collagen accumulation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(1):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao L, Huang J, Fan Y, et al. Exploration of CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing as therapy for osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(5):676–682. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fellmann C, Gowen BG, Lin P-C, Doudna JA, Corn JE. Cornerstones of CRISPR-Cas in drug development and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(2):89–100. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moreira Teixeira LS, Leijten JCH, Sobral J, et al. High throughput generated micro-aggregates of chondrocytes stimulate cartilage formation in vitro and in vivo. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;23:387–399. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v023a30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Futrega K, Palmer JS, Kinney M, et al. The microwell-mesh: A novel device and protocol for the high throughput manufacturing of cartilage microtissues. Biomaterials. 2015;62:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Moor L, Beyls E, Declercq H. Scaffold Free Microtissue Formation for Enhanced Cartilage Repair. Ann Biomed Eng. 2020;48(1):298–311. doi: 10.1007/s10439-019-02348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Witte K, de Andres MC, Wells JA, Dalby MJ, Salmeron-Sanchez M, Oreffo R. Chondrobags: a high throughput alginate-fibronectin micromass platform for in vitro human cartilage formation. Biofabrication. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/abb653. Published online 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xiahou Z, She Y, Zhang J, et al. Designer Hydrogel with Intelligently Switchable Stem-Cell Contact for Incubating Cartilaginous Microtissues. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(36):40163–40175. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c13426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fennema E, Rivron N, Rouwkema J, van Blitterswijk C, de Boer J. Spheroid culture as a tool for creating 3D complex tissues. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31(2):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vasyutin I, Zerihun L, Ivan C, Atala A. Bladder Organoids and Spheroids: Potential Tools for Normal and Diseased Tissue Modelling. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(3) doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abu-Hakmeh AE, Wan LQ. High-throughput cell aggregate culture for stem cell chondrogenesis. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2014;1202:11–19. doi: 10.1007/7651_2014_75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sutherland RM, Sordat B, Bamat J, Gabbert H, Bourrat B, Mueller-Klieser W. Oxygenation and differentiation in multicellular spheroids of human colon carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1986;46(10):5320–5329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hirschhaeuser F, Menne H, Dittfeld C, West J, Mueller-Klieser W, Kunz-Schughart LA. Multicellular tumor spheroids: an underestimated tool is catching up again. J Biotechnol. 2010;148(1):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cesarz Z, Tamama K. In: Stem Cells Int. Li R-K, editor. Vol. 2016. 2015. Spheroid Culture of Mesenchymal Stem Cells; 9176357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mueller-Klieser W. Three-dimensional cell cultures: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(4):C1109–1123. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Foldager CB, Nielsen AB, Munir S, et al. Combined 3D and hypoxic culture improves cartilage-specific gene expression in human chondrocytes. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(2):234–240. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.566135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schrobback K, Malda J, Crawford RW, Upton Z, Leavesley DI, Klein TJ. Effects of oxygen on zonal marker expression in human articular chondrocytes. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(9–10):920–933. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shi Y, Ma J, Zhang X, Li H, Jiang L, Qin J. Hypoxia combined with spheroid culture improves cartilage specific function in chondrocytes. Integr Biol Quant Biosci Nano Macro. 2015;7(3):289–297. doi: 10.1039/c4ib00273c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greco KV, Iqbal AJ, Rattazzi L, et al. High density micromass cultures of a human chondrocyte cell line: A reliable assay system to reveal the modulatory functions of pharmacological agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82(12):1919–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang AH, Motlekar NA, Stein A, Diamond SL, Shore EM, Mauck RL. High-throughput screening for modulators of mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(11):1909–1921. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Willard VP, Diekman BO, Sanchez-Adams J, Christoforou N, Leong KW, Guilak F. Use of cartilage derived from murine induced pluripotent stem cells for osteoarthritis drug screening. Arthritis Rheumatol Hoboken NJ. 2014;66(11):3062–3072. doi: 10.1002/art.38780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dennis JE, Splawn T, Kean TJ. High-Throughput, Temporal and Dose Dependent, Effect of Vitamins and Minerals on Chondrogenesis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mohanraj B, Meloni GR, Mauck RL, Dodge GR. A high-throughput model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis using engineered cartilage tissue analogs. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(9):1282–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parreno J, Bianchi VJ, Sermer C, et al. Adherent agarose mold cultures: An in vitro platform for multi-factorial assessment of passaged chondrocyte redifferentiation. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2018;36(9):2392–2405. doi: 10.1002/jor.23896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ham SL, Atefi E, Fyffe D, Tavana H. Robotic Production of Cancer Cell Spheroids with an Aqueous Two-phase System for Drug Testing. J Vis Exp JoVE. 2015;(98) doi: 10.3791/52754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aijian AP, Garrell RL. Digital microfluidics for automated hanging drop cell spheroid culture. J Lab Autom. 2015;20(3):283–295. doi: 10.1177/2211068214562002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Friedrich J, Seidel C, Ebner R, Kunz-Schughart LA. Spheroid-based drug screen: considerations and practical approach. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(3):309–324. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Atefi E, Lemmo S, Fyffe D, Luker GD, Tavana H. High Throughput, Polymeric Aqueous Two-Phase Printing of Tumor Spheroids. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24(41):6509–6515. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201401302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beachley VZ, Wolf MT, Sadtler K, et al. Tissue matrix arrays for high-throughput screening and systems analysis of cell function. Nat Methods. 2015;12(12):1197–1204. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shahi Thakuri P, Ham SL, Luker GD, Tavana H. Multiparametric Analysis of Oncology Drug Screening with Aqueous Two-Phase Tumor Spheroids. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(11):3724–3735. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zanoni M, Piccinini F, Arienti C, et al. 3D tumor spheroid models for in vitro therapeutic screening: a systematic approach to enhance the biological relevance of data obtained. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):19103. doi: 10.1038/srep19103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Côrtes I, Matsui RAM, Azevedo MS, et al. A Scaffold- and Serum-Free Method to Mimic Human Stable Cartilage Validated by Secretome. Tissue Eng Part A. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2018.0311. Published online May 2, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schon BS, Hooper GJ, Woodfield TBF. Modular Tissue Assembly Strategies for Biofabrication of Engineered Cartilage. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(1):100–114. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mansour Joseph M. Kinesiology: The Mechanics and Pathomechanics of Human Movement. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2004. Biomechanics of Cartilage; p. 980. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mohanraj B, Hou C, Meloni GR, Cosgrove BD, Dodge GR, Mauck RL. A high throughput mechanical screening device for cartilage tissue engineering. J Biomech. 2014;47(9):2130–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ranga A, Gobaa S, Okawa Y, Mosiewicz K, Negro A, Lutolf MP. 3D niche microarrays for systems-level analyses of cell fate | Nature Communications. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):4324. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]