Abstract

There are concerns that eating disorders have become commoner during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the electronic health records of 5.2 million people aged under 30, mostly in the USA, we show that the diagnostic incidence was 15.3% higher in 2020 overall compared to previous years (relative risk 1.15 [95% CI: 1.12-1.19). The relative risk increased steadily from March 2020 onwards, exceeding 1.5 by the end of the year. The increase occurred solely in females, and primarily affected teenagers and anorexia nervosa. A higher proportion of eating disorder patients in 2020 had suicidal ideation (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.30 [1.16-1.47] or attempted suicide (HR: 1.69 [1.21-2.35]).

An increased incidence of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic has been reported but not accurately or robustly quantified1–3. Referrals for eating disorders have doubled in the UK4. This study used electronic health records (EHR) to assess the relative incidence and outcomes (in terms of suicidal attempt, ideation, and death) of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to previous years.

Methods

We used TriNetX Analytics, a federated EHR network with anonymized data from 81 million patients, 93% of whom are in the USA. The participating health care organizations are a mixture of hospitals, primary care, and specialist providers, and include insured and uninsured patients. For further details about TriNetX see the Supplement, and ref. 5.

The incidence of a first diagnosis of eating disorder (ICD-10 code F50) was estimated for every 2-month period between January 20, 2020 (the date of the first recorded COVID-19 case in the USA) and January 19, 2021 in patients under 30 years-old who made at least one healthcare visit during this time. The incidence was compared to those in corresponding periods in 2019 using χ2 tests. Stratified results by age, sex, and subcategories of eating disorder are provided. We also compared the 2020 data with 2017 and with 2018. In a sensitivity analysis, patients were only included if they also made a healthcare visit between January 20, 2021 and April 28, 2021 (or the same period in 2020 for comparison) thus guaranteeing that they were not lost to follow up.

We assessed whether a diagnosis of COVID-19 (ICD-10 U07.1) was associated with a higher risk of subsequent eating disorders compared to a cohort of patients who had made a healthcare visit for another reason (matched for timing of the visit [in 2-month strata], demographics, and risk factors for COVID-19; see Supplementary Methods).

The risk of suicide ideation, attempt, and death within 6 months of an eating disorder diagnosis during the pandemic was compared with the previous three years using Kaplan-Meier analysis. For further details of analyses, see Supplementary Methods. STROBE reporting guidelines were followed.

Results

5,186,451 patients met the inclusion criteria (55.3% female, 44.4% male, 0.3% other; mean [SD] age: 15.4y [8.98]). 8,471 people were diagnosed with an eating disorder in the defined pandemic period (78.1% female, mean [SD] age 16.2y [7.2], and 19,843 (75.4% female; mean [SD] age 16.3y [7.6]) during the prior three years. For details see Supplementary Table 1.

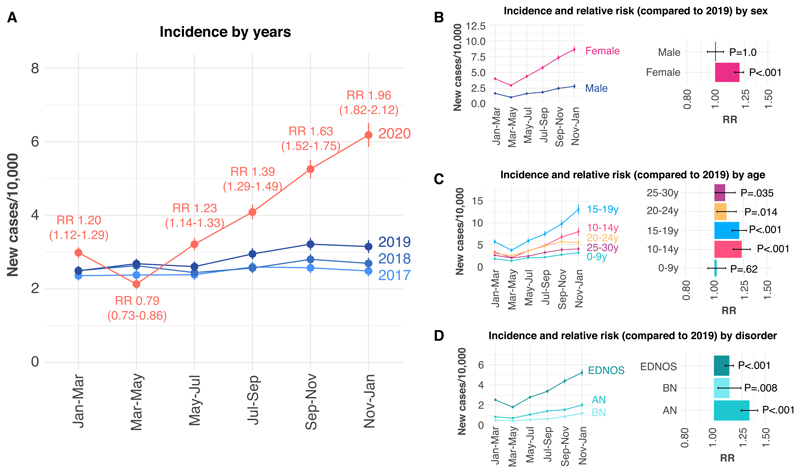

The incidence of a first diagnosis of an eating disorder has increased during the pandemic. An overall excess of 15.3% was observed compared to the previous year (relative risk [RR]: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.12–1.19, P<.001; Supplementary Table 2) with significant excesses observed in each 2-month period during the pandemic except for March 20 - May 19, 2020 (Figure 1A). Similar results were found in the sensitivity analysis (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.29–1.40; significant excess observed for all but March 20-May 19, 2021 periods; P<.001; Supplementary Figure 1). Results were also similar if 2020 was compared to 2017 or 2018 (see Supplementary Table 2). The increased risk of eating disorders during the pandemic period was limited to females (Figure 1B), was greatest for 10-19 year-olds (Figure 1C), and mostly affected anorexia nervosa diagnoses (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Incidence of eating disorders during vs. before the COVID-19 pandemic.

A: Incidence of eating disorders in 2-monthly periods during the pandemic (January 20, 2020 to January 19, 2021) compared to previous years (January 20, 2017-2019 to January 19, 2018-2020). The relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals are provided for each 2-monthly period during the pandemic compared to the same period in 2019. B: Incidence stratified by sex. C: Incidence stratified by age group. D: Incidence stratified by eating disorder subtype. RR in each stratum compared to the corresponding stratum in the previous year. RR>1 indicates a risk that is higher during the pandemic. AN=Anorexia Nervosa, BN=Bulimia nervosa, EDNOS=Eating disorder not otherwise specified.

As shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 2, compared to patients diagnosed with an eating disorder in the previous 3 years, those diagnosed during the pandemic were at a higher risk of attempting suicide (0.89% [0.68-1.16] vs. 0.52% [0.43-0.64]; hazard ratio [HR]: 1.69 [1.21-2.35], p=0.0015) and having suicidal ideation (6.3% [5.7-7.0] vs. 4.8% [4.5-5.1]; HR]: 1.30 [1.16-1.47], p<0.001), but death did not differ.

Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were not at an increased risk of an eating disorder compared to a matched cohort of patients who made a visit to a healthcare organization for a different reason during the pandemic (adequate matching was achieved for all covariates; Supplementary Tables 3-7; HR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.65–1.12, P=0.26, Supplementary Figure 3).

Discussion

These data show an increased incidence of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, and with higher rates of suicidal behavior amongst those diagnosed. After a decrease in the early part of 2020 (which likely reflects the marked reduction in all diagnoses made in the EHR network during this period6), the incidence of eating disorders increased steadily throughout the rest of 2020, such that the relative risk compared to previous years had exceeded 1.5 by the end of the year (being 1.96 in the primary analysis [Fig. 1A], and 1.59 in the sensitivity analysis [Suppl. Fig. 1]). The mechanisms underlying these observations remain to be determined, though a range of plausible explanations have been proferred.2 The finding that the increase was seen only in females, and was greater in teenagers and for anorexia nervosa, may help focus future investigations. No increased risk was observed among people diagnosed with COVID-19 infection, unlike many other psychiatric disorders in this EHR network.5,6

The main strength of the study is the use of a large EHR network which permits robust and up-to-date estimates of incidence and relative risk. Limitations include those inherent to EHR studies (e.g., lack of information about the accuracy or completeness of diagnoses; see the Supplement and ref. 5 for discussion). Our findings relate to patients who made a healthcare visit and received a diagnosis, and should not be generalized to the wider population, especially since many patients with eating disorders do not seek treatment.7 Since most patients were in the USA, findings may not apply in other locations; it was not possible to analyze separately the 7% of patients from other countries. Nationwide studies and prospective cohort studies in different settings are needed to complement these findings, and to assess how the incidence trajectory changes as the pandemic progresses. It is possible that the incidence may continue to rise further if there remains an excess of cases in the community yet to present or receive a diagnosis; alternatively, the incidence might fall if some of the recent excess reflects people whose diagnosis was made earlier than would have otherwise been the case.

In summary, our findings support the view that the incidence and outcomes of eating disorders have been adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.1–4,8–10 Services need to be resourced adequately and urgently to deal with the increased demand.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). M.T. is an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow and an NIHR Oxford Health BRC Senior Research Fellow. S.L. is an employee of TriNetX. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.T. and P.J.H. designed the study. M.T. conducted the analyses, assisted by S.L. M.T. and P.J.H. wrote the paper with input from J.R.G. and S.L. All authors approved the submission.

Declaration of interest

M.T. and P.J.H. were granted unrestricted access to the TriNetX Analytics network for the purpose of research relevant to psychiatry and with no constraints on the analyses performed nor the decision to publish. S.L. is an employee of TriNetX. J.R.G., a member of the Editorial Board, played no part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

Data availability

The TriNetX system returned the results of these analyses as csv files which were downloaded and archived. Data presented in this paper can be accessed at [URL to be added on publication]. Additionally, TriNetX will grant access to researchers if they have a specific concern (via the third-party agreement option).

References

- 1.Touyz S, Lacey H, Hay P. Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:19. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodgers RF, Lombardo C, Cerolini S, Franko DL, Omori M, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorder risk and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1166–70. doi: 10.1002/eat.23318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haripersad YV, Kannegiesser-Bailey M, Morton K, Skeldon S, Shipton N, Edwards K, et al. Outbreak of anorexia nervosa admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:e15. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solmi F, Downs JL, Nicholls DE. COVID-19 and eating disorders in young people. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:316–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–27. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:130–40. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart A, Granillo MT, Jorm AF, Paxton SJ. Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: A systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:727–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monteleone AM, Marciello F, Cascino G, Abbate-Daga G, Anselmetti S, Baiano M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown and of the following “re-opening” period on specific and general psychopathology in people with Eating Disorders: the emergent role of internalizing symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2021;285:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellini G, Cassioli E, Rossi E, Innocenti M, Gironi V, Sanfilippo G, et al. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic on eating disorders: A longitudinal observation of pre versus post psychopathological features in a sample of patients with eating disorders and a group of healthy controls. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1855–62. doi: 10.1002/eat.23368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spettigue W, Obeid N, Erbach M, Feder S, Finner N, Harrison ME, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on adolescents with eating disorders: a cohort study. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:65. doi: 10.1186/s40337-021-00419-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The TriNetX system returned the results of these analyses as csv files which were downloaded and archived. Data presented in this paper can be accessed at [URL to be added on publication]. Additionally, TriNetX will grant access to researchers if they have a specific concern (via the third-party agreement option).