Summary

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchored proteins (GPI-APs) are tethered to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane where they function as key regulators of a plethora of biological processes in eukaryotes. Self-incompatibility (SI) plays a pivotal role regulating fertilization in higher plants through recognition and rejection of ‘self’ pollen. Here we used Arabidopsis thaliana lines engineered to be self-incompatible by expression of Papaver rhoeas SI determinants for an SI suppressor screen. We identify HLD1/AtPGAP1, an ortholog of the human GPI-inositol deacylase PGAP1, as a critical component required for the SI response. Besides a delay in flowering time, no developmental defects were observed in hld1/atpgap1 knockout plants, but SI was completely abolished. We demonstrate that HLD1/AtPGAP1 functions as a GPI-inositol deacylase and that this GPI-remodeling activity is essential for SI. Using GFP–SKU5 as a representative GPI-AP, we show that the HLD1/AtPGAP1 mutation does not affect GPI-AP production and targeting but affects their cleavage and release from membranes in vivo. Our data not only implicate GPI-APs in SI, providing new directions to investigate SI mechanisms, but also identify a key functional role for GPI-AP remodeling by inositol deacylation in planta.

Introduction

Addition of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) residue to proteins is a highly conserved post-translational modification that plays crucial roles in the biosynthesis and targeting of GPI-anchored proteins (GPI-APs) to the outer leaflet plasma membrane in eukaryotes 1,2. Over 250 GPI-APs exist in Arabidopsis thaliana 3,4. Several GPI-APs have been shown to be key regulators of cell signaling, growth, morphogenesis, reproduction and pathogenesis in yeast, mammals, and plants 5-7. GPI-AP biosynthesis, remodeling, and export are well-characterized in yeast and animal cells 8,9. The GPI anchor is synthesized and transferred to target proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 1. Knockouts of Phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis (PIG) genes in mouse and Arabidopsis demonstrate that GPI-anchor synthesis is essential for animal and plant viability, male fertility, early embryo and tissue development 6,10,11. Once the GPI anchor is attached to a target protein, remodeling takes place. In animals, the first step involves the removal of an acyl chain on the GPI inositol, by post-GPI attachment to proteins 1 (PGAP1), a GPI-inositol deacylase 12. After further processing, GPI-APs are transported to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane 5,8, where they are retained or released by cleavage 13. Although homologs of PGAP1 have been identified in plant genomes 6,14,15, there are no functional data about the biological in planta impact of this GPI remodeling and maturation step in plants.

Self-incompatibility (SI) regulates the rejection of ‘self’ pollen, preventing inbreeding and promoting genetic diversity. Generally, SI is genetically controlled by a polymorphic multi-allelic S-locus, with each S-haplotype encoding a pair of S-determinants 16. Pistils discriminate between “self” and “non-self” pollen using allele-specific interactions between these two S-determinants. In field poppy (Papaver rhoeas), the female S-determinant PrsS is specifically expressed in the stigma 17, whereas the male S-determinant PrpS is specifically expressed in pollen 18. Briefly, PrpS is a small, novel transmembrane protein 18 and PrsS is a small secreted protein of the cysteine-rich peptide (CRP) family of proteins that include LUREs and rapid alkalinization factors (RALFs) 19. Cognate PrpS-PrsS interaction triggers a signaling network resulting in pollen tube growth arrest and programmed cell death (PCD) of ‘self’-pollen 20. Recently, we showed that cognate PrpS and PrsS co-expressed in the self-compatible model plant Arabidopsis rendered Arabidopsis effectively self-incompatible (designated as At-SI lines), with no self-seed set, demonstrating that Papaver S-determinants are sufficient to confer functional SI in Arabidopsis 21,22.

Here we used the Arabidopsis At-SI lines as the basis for a forward genetic mutant screen to identify new genes involved in controlling Papaver SI. We identified 12 mutant alleles of highlander1 (hld1) exhibiting suppressed SI. We mapped all hld1 alleles to AtPGAP1, a functional ortholog of the mammalian PGAP1 gene encoding a protein involved in the deacylation of GPI-APs 15. Our study of hld1/atpgap1 plants and the AtPGAP1 mutation reveals a crucial role of GPI-APs and GPI-remodeling of GPI-APs by AtPGAP1 in the Papaver SI response.

Results

Identification of SI-defective highlander1 mutants

To discover novel players of the Papaver SI process, we performed an ethyl methanesulfonate-(EMS-)based forward genetic screen on ~50,000 At-SI M1 individuals for suppressors of SI (Figure S1A, STAR Methods). Initially, we identified 40 mutants showing wild-type siliques. After excluding mutants with mutations in the PrpS1/PrsS1 transgenes, or changes in PrpS1–GFP expression, we confirmed in total twelve independent self-compatible SI-repressor mutants with restored normal self-seed set (Figure 1A; Figure S1B-C) and named them highlander1 (hld1-3/5/6/7/17/18/19/24/25/30/37/39), after the immortal warrior in the 1980s film of the same name. Pollinating hld1 pollen onto At-SI stigmas resulted in significantly longer siliques (Figure 1B, p<0.001) and higher seed set (Figure S1D, p<0.001) than those resulted from the At-SI parent line self-pollination. This loss of SI was not observed in the reciprocal cross (Figure 1B, p=0.1458, N.S.; Figure S1D, p=0.0909, N.S.). Furthermore, after the first backcross (BC) to the At-SI parent line, all the heterozygous hld1 BC1 generation plants were self-compatible (Table S1, n= 167). This demonstrates that mutation in the hld1 mutants affect the male gametophyte (pollen) and that the 50% of the pollen grains carrying the hld1 mutant alleles are sufficient for full seed set.

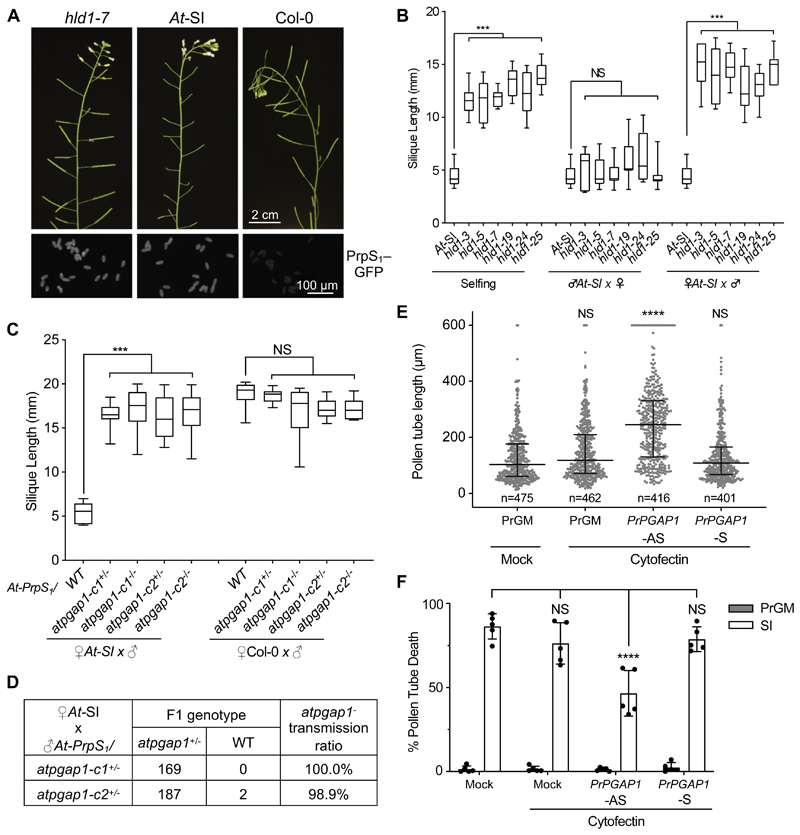

Figure 1. Identification of hld1 as a male gametophytic mutant that overcomes SI.

(A) Mutants were screened for a defective SI phenotype, with normal siliques and seed set. Upper panel: Inflorescences from hld1-7 mutants had normal length siliques like Col-0 plants, in contrast to At-SI. Lower panel: Fluorescence imaging shows that PrpS1–GFP expression in hld1 mutant pollen is similar to expression in At-SI pollen.

(B) Hld1 stigmas were pollinated with self-pollen (selfing) or At-SI pollen (♂At-SI x ♀), and At-SI stigmas were pollinated with hld1 pollen (♀At-SI x ♂). At-SI stigmas pollinated with At-SI pollen were SI controls for these pollinations. Silique length measurements showed that the hld1 mutants used as the male parent had significantly longer silique lengths than the At-SI parent line. Hld1 mutants used as the female parent pollinated with At-SI pollen displayed a normal SI phenotype of short silique lengths. N=9-11. One-way ANOVA. ***: p<0.001. NS: not-significant, p>0.05.

(C) At-SI or Col-0 stigmas were pollinated with At-PrpS1 pollen containing the CRISPR-Cas9-derived AtPGAP1 mutant allele (atpgap1-c1 or atpgap1-c2). Significant increases in silique lengths were observed when AtPGAP1 was mutated, in both heterozygous and homozygous mutants. N=12-16. One-way ANOVA. ***: p<0.001. NS: not-significant, p>0.05.

(D) Segregation analysis of the F1 population of ♀At-SIx♂At-PrpS1/atpgap1+/- showed that ~100% of the progenies are atpgap1 heterozygous mutants, demonstrating that when pollinated onto At-SI stigmas, only atpgap1- mutant pollen can bypass the SI response, resulting in successful fertilization and seed set.

(E, F) Papaver rhoeas pollen was treated with an antisense oligonucleotide designed against PrPGAP1 (PrPGAP1-AS), which alleviated SI-induced pollen tube growth inhibition (E; Results = median with interquartile range; n = the number of pollen tubes measured; one-way ANOVA) and death (F; Results = mean ± SD; n = 5 biological replicates, with ~100 pollen tubes counted for each sample in each replicate; two-way ANOVA.); the sense oligonucleotide (PrPGAP1-S) had no significant effect. ****: p<0.0001. NS: not-significant, p>0.05. PrGM acted as a negative control, and ~no pollen tube death was observed.

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) identified AtPGAP1 as the causal gene for all the hld1 mutant alleles

To reveal the molecular identity of the hld1 mutants, we re-sequenced the genome of the self-compatible population of six independent mutants after two backcrosses. SHOREmap analysis 23 revealed six different nonsynonymous mutations in a single gene, At3g27325 (recently described as AtPGAP1 by 15; Figure S2A; Table S2). Analysis of the segregating populations revealed 100% linkage between the AtPGAP1 mutation and suppression of SI (Table S3, n=298). Genotyping of the remaining hld1 mutants identified six additional independent mutant alleles of the same gene (Table S2), suggesting that the screen had a high level of saturation and that AtPGAP1 was the single causal locus for SI suppression in all the mutants identified. The identification of a single causal locus in our suppressor screen was surprising and suggests that other genes involved in SI might either act redundantly, or play important roles for plant viability or fertility.

CRISPR-Cas9 confirms that AtPGAP1 is the causal gene for the hld1 phenotype

To confirm AtPGAP1 as the causal gene for SI suppression, we generated two independent CRISPR-Cas9 knockout mutants (atpgap1-c1 and atpgap1-c2, Figure S2B) using Arabidopsis NTP303pro:PrpS1–GFP (At-PrpS1) as the background. Pollinating At-SI stigmas with At-PrpS1 pollen resulted in a SI phenotype with no seed set. However, At-SI stigmas pollinated with At-PrpS1/atpgap1-c1 or At-PrpS1/atpgap1-c2 pollen displayed normal siliques and seed set (Figure 1C, Figure S2C). This demonstrates that targeted mutation of AtPGAP1 is sufficient to prevent SI. Consistent with this, the F1 population of an ♀At-SI x ♂At-PrpS1/atpgap1+/- cross comprised 99.5% atpgap1+/- mutant plants (n=358; Figure 1D), showing that in heterozygous mutants it is almost exclusively atpgap1 mutant pollen grains, but not their wild-type siblings, that overcome SI. When introgressed into the At-SI background line, atpgap1-c1 and atpgap1-c2 were both sufficient to cause breakdown of SI, comparable to the EMS mutagenesis-derived hld1 alleles (Figure S2D, E). CRISPR-Cas9-generated mutations of AtPGAP1 phenocopy the EMS-generated hld1 mutant phenotype, confirming that AtPGAP1 is the causal gene for hld1-mediated SI suppression.

PGAP1 is also required for pollen SI in Papaver

To test whether PGAP1 also functions in the original Papaver-SI context, we investigated if the Papaver rhoeas PGAP1 ortholog PrPGAP1 is needed for an authentic Papaver pollen SI response. As a transgenic approach with this species is not possible, we used an antisense oligonucleotide approach 18,24. Treatment of P. rhoeas pollen with PrPGAP1 antisense oligonucleotides significantly alleviated SI-induced pollen tube growth inhibition (Figure 1E; p<0.0001) and pollen death from >85% to ~45% (Figure 1F; p<0.0001), whereas no significant effect was observed when treated with the sense oligonucleotide (Figure 1E, p=0.9216; Figure 1F, p=0.3277). This demonstrates that PGAP1 does not just work in the transgenic Arabidopsis At-SI context, but that it is required for SI-induced pollen tube growth inhibition and cell death in Papaver.

AtPGAP1 regulates SI irrespective of the S-alleles involved

Prevention of self-pollination by SI relies on a polymorphic S-locus involving S-specific self-recognition. Although AtPGAP1 regulated the PrpS1-PrsS1-based SI response, it was not clear if AtPGAP1 could also regulate the SI-response involving other cognate S-alleles. We therefore examined if the AtPGAP1 mutation disrupted SI in plants expressing an alternative pair of cognate S-alleles, PrpS3 and PrpS3. Pollinating stigmas expressing the PrpS3 (At-PrpS3) with At-PrpS3 pollen resulted in SI, with a significant reduction in silique length and almost no seed, compared with the control pollination ♀At-PrpS3 x ♂Col-0 (Figure 2A, B). In contrast, pollinating At-PrpS3 with At-PrpS3/atpgap1 pollen resulted in normal silique lengths and seed set (Figure 2A, B), showing that mutation of the AtPGAP1 gene abolishes the PrpS3-PrpS3-based SI. These results demonstrate that AtPGAP1 regulates SI irrespective of the S-alleles involved.

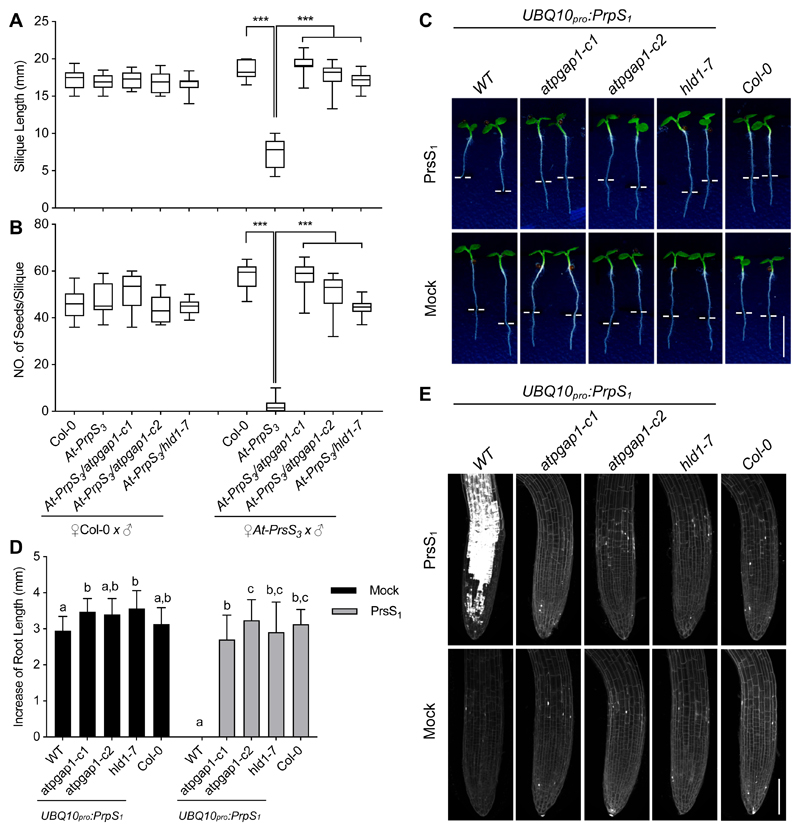

Figure 2. AtPGAP1 regulates SI in an S-specific manner and regulates ectopic “SI” in roots.

(A-B) At-PrpS3 pollen containing atpgap1-c1, atpgap1-c2, or hld1-7 mutant allele was pollinated onto At-PrpS3 or Col-0 stigmas. Silique lengths (A) and seed set (B) were measured and showed that S3-specific inhibition was prevented in the mutant lines. N=10-20. One-way ANOVA. ***: p<0.001.

(C) Treatment of UBQ10pro:PrpS1 seedlings with PrsS1 resulted in root growth inhibition; in contrast, when UBQ10pro:PrpS1/atpgap1 seedlings were given the same treatment, no inhibition was observed (upper panel). Mock treatment did not affect any of the seedling roots (lower panel). White lines indicate the position of root tips when treated. Bar = 0.5 cm.

(D) Quantification of the increases in root length 24h after treatment; 12-20 seedlings from three independent experiments were measured for each treatment. Results = mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with multiple comparison test. Different letters indicate p<0.05.

(E) Treatment of UBQ10pro:PrpS1 seedlings with PrsS1 resulted in root cell death indicated by propidium iodide (PI) signals (white); when UBQ10pro:PrpS1/atpgap1 seedlings were treated with PrsS1 protein, minimal cell death was observed, comparable with what was observed in Col-0 seedlings. Bar = 100 μm.

AtPGAP1 regulates ectopic “SI-like PCD” in Arabidopsis roots

We recently established that expression of PrpS1-PrsS1 in Arabidopsis roots triggers an ectopic “SI-like PCD” response in vegetative tissues, resulting in root growth inhibition and widespread cell death 25. We examined if AtPGAP1 is necessary for this ectopic “SI-like PCD” response outside the reproductive context. While addition of recombinant PrsS1 proteins to UBQ10pro:PrpS1 seedlings resulted in root growth arrest and cell death 25, treatment of UBQ10pro:PrpS1/atpgap1 seedling roots with PrsS1 showed no such effect (Figure 2C-E). This suppression of root growth inhibition and root cell death reveals that AtPGAP1 is not only required for SI, but also for the ectopic “SI-like PCD” response independent of the reproductive context.

AtPGAP1 is a functional HsPGAP1 ortholog

As At3g27325 had not been annotated as a PGAP1 ortholog at the time when we mapped the hld1 mutations to this locus, we investigated its possible orthology to genes in animals and fungi. Protein sequence analysis revealed that At3g27325 contains a PGAP1-like domain (PFAM domain ID: PF07819), and is a putative PGAP1 homolog 6,14. PGAP1 has been identified in mammals and its ortholog, Bypass of Sec Thirteen 1 (Bst1) in yeast; it encodes a GPI inositol-deacylase 12. We constructed a phylogenetic tree of 631 predicted PGAP1 protein homologs from >300 eukaryotic species (Figure 3A, B). Two major phylogenetic clades were identified for plants; in Arabidopsis, AtPGAP1 (At3g27325) and another PGAP1-like domain containing protein, At5g17670 were classified into different clades (Figure 3A). The divergence of these two clades can be traced back to an ancient whole genome duplication event occurring before the radiation of extant Viridiplantae (Figure 3A, B) 26. Comparison of the two homologs, AtPGAP1 and At5g17670 from A. thaliana with the Homo sapiens PGAP1, revealed that unlike AtPGAP1, which has a similar predicted secondary structure and a conserved ER localization 15 as HsPGAP1, At5g17670 is much smaller in size (Figure S3A), and predicted to be a chloroplast-located protein (https://www.uniprot.org/). This suggests that AtPGAP1 is a homolog of HsPGAP1 14,15, while At5g17670 PGAP1 is not.

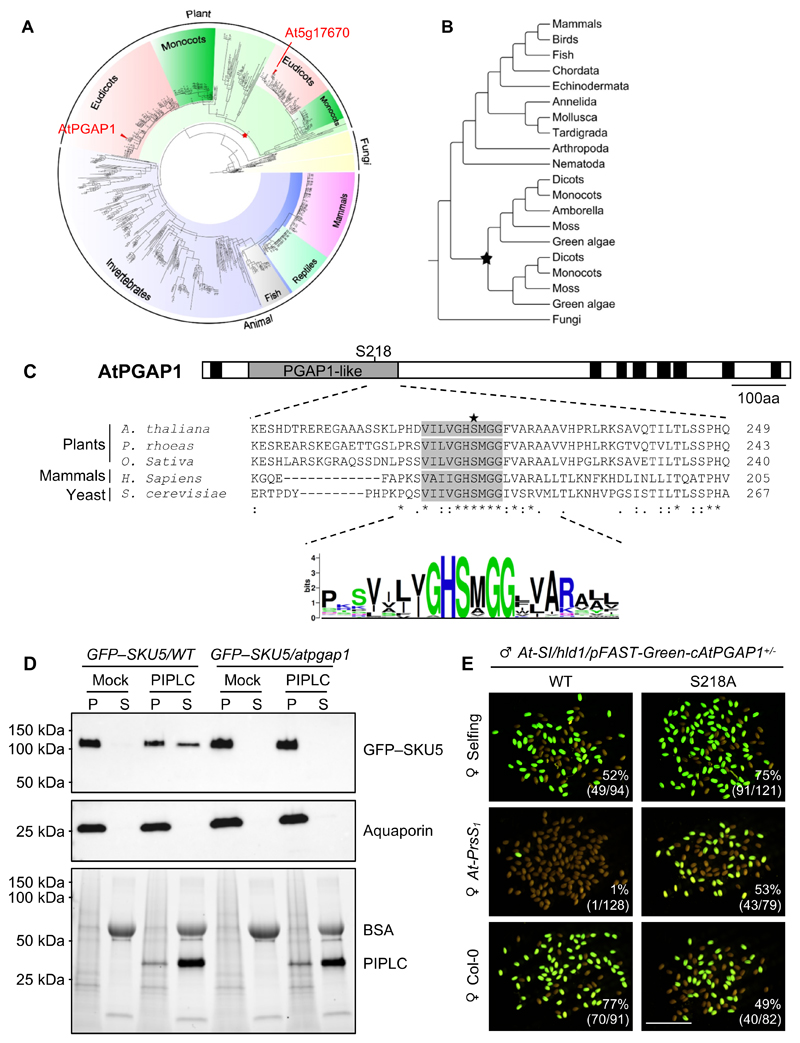

Figure 3. AtPGAP1 is a GPI inositol deacylase and this function is required for SI.

(A, B) A phylogenetic tree of 631 predicted PGAP1 protein homologues from >300 eukaryotic species identified two major phylogenetic clades in plants; Two putative Arabidopsis homologs AtPGAP1 and At5g17670 classified into different clades (red triangles). Star indicates a genome duplication event. Detailed information of the 631 PGAP1-like domain-containing proteins used for this phylogeny tree is contained in Table S6.

(C) Upper panel: cartoon of AtPGAP1 protein secondary structure. The PGAP1-like domain is indicated by the grey box. Black boxes indicate transmembrane domains. Middle panel: amino acid sequence alignment around the conserved lipase motif in the PGAP1-like domain in several higher plants, human and yeast. The grey box indicates the lipase motif with the catalytic site Serine 218 indicated (star). Bottom panel: amino acid motif logo shows that the lipase motif of the PGAP1-like domain is conserved across eukaryotic kingdoms.

(D) PI-PLC assays used pelleted membrane proteins (P) separated from soluble (S) proteins after centrifugation. GFP–SKU5 (~120 kDa) was enriched in the pellet (P) fractions in both wild type (WT) and atpgap1 mutant in the mock (buffer control) treatment. After PI-PLC treatment, GFP–SKU5 was present in the soluble (S) fraction in WT samples, demonstrating cleavage by PI-PLC, while GFP–SKU5 from the atpgap1 mutants was found in the pellet, demonstrating that in the atpgap1 mutant this GPI-AP was resistant to PI-PLC treatment. This supports the idea that in the atpgap1 mutant a persistent inositol-linked acyl chain makes GPI-APs insensitive to cleavage by PI-PLC. Aquaporin (~26 kDa) is shown as a control for membrane extraction; loading control is stain-free signals of PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Precast gels (Bio-Rad).

(E) Hld1 mutants were transformed with AtPGAP1pro:mCherry–cAtPGAP1 or AtPGAP1pro:mCherry–cAtPGAP1(S218A) cloned in the pFAST-Green plasmid vector backbone, which expresses GFP in the seeds. So GFP signals report transgene transmission in the seeds in the F1 generation. Representative images of segregating seeds resulted from pollinations by pollen from T1 heterozygous plants onto self-stigmas (upper panel), At-PrsS1 stigmas (middle panel) or Col-0 stigmas (lower panel). Numbers indicate the ratio of GFP-positive seeds (number of GFP seeds/total seeds). Bar = 5 mm. Unlike the wild-type HLD1 that rescued the hld1 phenotype and restored SI, the inositol deacylase-defective S218A HLD1 allele did not, therefore resulting in normal Mendelian segregation of GFP signals in the T2 seeds.

AtPGAP1 functions as a GPI-inositol deacylase

Mammalian PGAP1 is a GPI-inositol deacylase that removes the inositol acyl chain after the attachment of the GPI anchor to its target protein 12. HsPGAP1 is ubiquitously expressed in humans 27; we found AtPGAP1 expression in all the Arabidopsis tissues examined (Figure S3B-D) 28. A key feature of PGAP1 is a catalytic serine-containing motif, V***GHSMGG, in the PGAP1-like domain that is highly conserved across the eukaryotic kingdoms, and also present around serine 218 in AtPGAP1 (Figure 3C). Mutation of PGAP1 in mammals results in a “three-footed” structure of GPI-APs that retain an extra acyl chain in addition to the two membrane-anchored non-polar fatty acid tails 12. This configuration makes GPI-APs in the plasma membrane insensitive to cleavage by phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) and has been used to establish the GPI-inositol deacylase function of PGAP1 12. To establish the biochemical function of Arabidopsis AtPGAP1, we examined if a representative GPI-AP in the atpgap1 mutant background was resistant to PI-PLC treatment. To this end, we introduced the atpgap1 mutant into a line expressing GFP-tagged SKU5, an established Arabidopsis GPI-AP localizing to the plasma membrane and cell wall 29. A PI-PLC assay revealed that GFP–SKU5 was highly resistant to PI-PLC-mediated GPI cleavage in the atpgap1 mutant (Figure 3D). This result recapitulates analogous findings obtained in mammalian pgap1 knockouts 9,12,30, supporting the hypothesis that GFP–SKU5/atpgap1 is “three-footed” and insensitive to PI-PLC treatment 12. In summary, AtPGAP1 is an inositol deacylase and a functional ortholog of HsPGAP1, which independently confirms a recently published study 15.

AtPGAP1 GPI-inositol deacylase function is required for SI

To examine if AtPGAP1 inositol deacylase activity is required for the SI response, we mutated the conserved serine 218 in the catalytic core of the PGAP1-like domain 12 (Figure 3C) to alanine (S218A), and cloned it into the pFAST-Green plasmid vector 31. As a control we cloned the wild-type AtPGAP1 cDNA (cAtPGAP1) into the same vector and transformed both constructs into the At-SI/hld1 background. In segregating T2 seeds from T1 heterozygous At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1 control plants, in contrast to normal Mendelian segregation, only ~50% of the T2 seeds were GFP- (pFAST-)positive. This suggests that the cAtPGAP1 wild-type transgene was only transmitted via the female side, while its transmission via the male side was blocked by the restored SI-phenotype (Figure 3E; Table S4). This was further verified by the observation that the At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1 transgene was barely transmitted to the F1 seeds after pollination to the stigma of an At-PrsS1 plant (Figure 3E; Table S4). This shows that the wild-type cDNA of AtPGAP1 complements the hld1 mutant phenotype and restores SI. In contrast, selfed heterozygous T1 plants At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1(S218A) expressing the S218A mutant construct displayed normal Mendelian segregation, with ~75% GFP-positive T2 seeds (Figure 3E; Table S4), indicating that pollen carrying the S218A mutant allele failed to restore SI. Consistent with this observation, pollinating the At-PrsS1 background line or Col-0 wild-type plants with pollen from heterozygous At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1(S218A) plants resulted in a full transmission rate, with ~50% of GFP-positive F1 seeds (Figure 3E; Table S4). Thus, unlike the wild-type AtPGAP1 that rescued the hld1 phenotype and restored SI, the inositol deacylase-defective S218A AtPGAP1 allele did not. This demonstrates that the AtPGAP1 inositol deacylase activity is essential for SI, implicating a requirement for correctly remodeled GPI-APs in this process.

Plasma-membrane localized GPI-APs are required for SI

To assess if a lack of GPI-APs at the plasma membrane had the same SI-suppressing effect as faulty GPI-AP remodeling, we investigated established GPI-AP biosynthesis mutants in the SI context. SETH1 and SETH2 (orthologues of PIG-C and PIG-A) are subunits of the GPI-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase complex that transfers N-acetylglucosamine to phosphatidylinositol as the first step of GPI anchor biosynthesis 5. The respective knockout mutants are devoid of GPI-APs at the plasma membrane 5,30, and seth1-2 and seth2 mutant alleles are homozygous lethal 10. Pollen from heterozygous At-PrpS1/seth1-2+/- and At-PrpS1/seth2+/- plants pollinated onto At-PrsS1 stigmas produced short siliques without seeds, so showing no SI-repression phenotype (Figure 4A, B). However, seth1-2 and seth2 are known to almost completely abolish pollen germination and tube growth (Figure 4C) 10, so pollination assays were not suitable to establish their involvement in SI. We therefore used an in vitro SI bioassay32 to examine the effect of these mutants on pollen viability. Addition of PrsS1 to pollen of At-PrpS1/seth1-2+/- or At-PrpS1/seth2+/- plants resulted in ~50% pollen grain death in contrast to > 98% death in At-PrpS1 pollen (Figure 4D-F), demonstrating that SI-induced cell death does not occur in SETH1 or SETH2 knockouts. This demonstrates that the SI response depends on at least two processes in the GPI-anchoring pathway: the first step of GPI anchor synthesis facilitated by SETH1/2, and the later GPI remodeling by the inositol deacylase, AtPGAP1, suggesting the presence of GPI-APs at the plasma membrane being indispensable for SI-PCD.

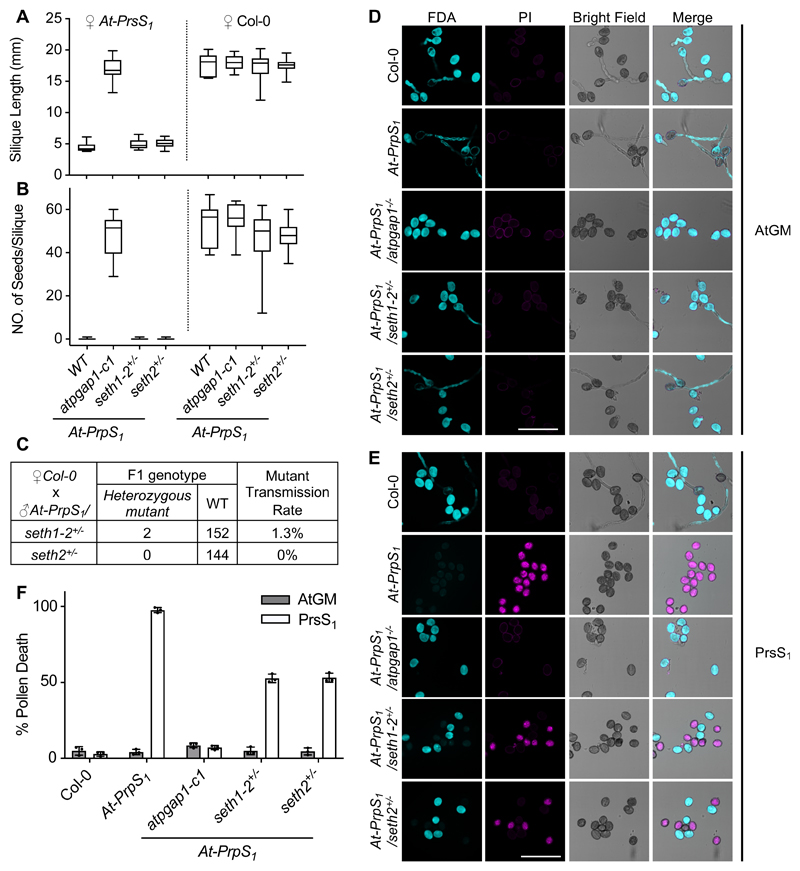

Figure 4. Evidence for involvement of the GPI-anchoring pathway in the regulation of SI-induced death of pollen.

(A-C) GPI-anchoring pathway mutants, seth1-2 and seth2, were introduced into At-PrpS1 background and pollen from these plants was pollinated onto At-PrsS1 or Col-0 stigmas. Pollinating At-PrsS1 stigmas with At-PrpS1/seth1+/- or At-PrpS1/seth2+/- pollen resulted in short siliques (A) and no seed set (B). N=13-17. (C) Genotyping the F1 seedlings of ♀Col-0 x ♂At-PrpS1/seth1+/- and ♀Col-0 x ♂At-PrpS1/seth2+/- revealed that mutation of seth1 or seth2 abolished pollen fertilization.

(D-F) The seth1-2 and seth2 mutations were introduced into At-PrpS1 background, and pollen from these plants was treated with At-GM buffer (D) or PrsS1 proteins (E). Samples were co-stained with FDA and PI 6h after treatment. Quantification of PI positive ratios (F) showed that all pollen samples were ~fully viable after treatment with At-GM, but after treatment with PrsS1 proteins, in contrast to the ~95% death induced in At-PrpS1 pollen, only minimal (~5%) pollen death was observed for Col-0 or At-PrpS1/atpgap1-c1 pollen. Bar = 100 μm. Three biological replicates were carried out, with 100-200 pollen grains counted for each sample in each replicate.

GFP–SKU5 targeting to the plasma membrane is not affected by lack of PGAP1

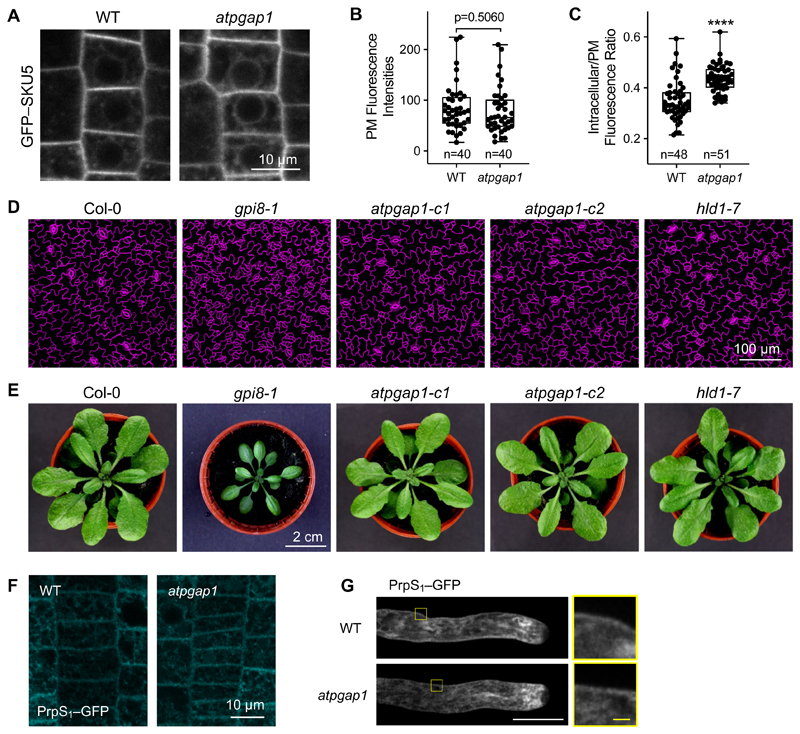

We next asked the question whether non-remodeled GPI-APs in atpgap1 mutants were actually still correctly targeted to the plasma membrane. In mammals and yeast, GPI-inositol deacylation by PGAP1 12 is important for efficient sorting of GPI-APs to exit the ER 5,15,33. However, knockout of PGAP1 only delays, but does not prevent, transport of GPI-APs to the plasma membrane, so the functional significance of GPI deacylation remains unclear 9,34. Similar to the effect of PGAP1 knockout in animals 12,30, the AtPGAP1 mutation had no obvious effect on overall GFP–SKU5 protein expression levels (Figure S4A, B; Figure 5A, B). Confocal imaging of GFP–SKU5 signals in 4-day-old GFP–SKU5/WT and GFP–SKU5/atpgap1 seedling roots and quantification showed that GFP–SKU5 was targeted to the plasma membrane at similar levels in the atpgap1 mutant (Figure 5A, B), suggesting that normal levels of this GPI-AP are targeted to the plasma membrane in the atpgap1 mutant (Figure 5B). Nevertheless, there was a significantly increased proportion of intracellular GFP–SKU5 signal in the atpgap1 mutant (****, p<0.0001, Figure 5C), consistent with delayed transport of GPI-APs observed in pgap1 mutant mammalian and plant cells 9,15. Importantly, our data show that GFP–SKU5 is still able to reach the plasma membrane, as has been reported for other GPI-APs in mammalian and plant pgap1 mutants 9,15.

Figure 5. Mutation of AtPGAP1 does not affect the targeting of GFP–SKU5 and PrpS1 to the plasma membrane, and has no major effect on plant development.

(A) Representative confocal images of GFP–SKU5 signals of 4-day-old GFP–SKU5/WT or GFP–SKU5/atpgap1-c1 seedling root meristem epidermis. GFP–SKU5 signals were observed at the plasma membrane (PM) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

(B) Quantification of GFP fluorescence at the PM showed no significant difference between WT and the atpgap1 mutant.

(C) A significant increase (****, p<0.0001, student’s t-test) in the ER/PM GFP signal ratio was observed in the atpgap1 mutant.

(D, E) The gpi8-1 mutant was established to have reduced accumulation of GPI-APs; this affects both stomata formation, and plant growth 35. This gpi8-1 was employed as a negative control here. (D) Cotyledon epidermis of 5-day-old seedlings was labelled with FM4-64. The gpi8-1 mutation resulted in has clusters of stomata, which were not observed in Col-0, nor the atpgap1/hld1 mutants. (E) The gpi8-1 mutation resulted in a significant delay of plant development which was not observed in Col-0, nor the atpgap1/hld1 mutants.

(F, G) Representative confocal images of PrpS1–GFP signals of seedling epidermis (F) and pollen tubes (G) from WT or atpgap1-c1 plants. The right hand box outlined in yellow shows a zoomed image of a part of the region of the pollen tube including the plasma membrane indicated in the left hand image. No observable difference of the PrpS1–GFP signals could be seen in the WT and atpgap1. White bar = 10 μm; yellow bar = 1 μm.

See also Figure S4.

It is well established that lack of GPI-APs at the plasma membrane strongly affect plant development. Both seth1 and seth2 mutants are homozygous lethal, and the hypomorphic gpi8-1 allele of AtGPI8, a PIG-K ortholog, exhibits reduced accumulation of GPI-APs and disturbed growth and stomata formation (Figure 5D) 35. In contrast, mutation of AtPGAP1 had no major effect on vegetative plant development (Figure 5D, E). However, we observed that flowering time was delayed in atpgap1 plants (Figure S4D), though less strongly than in gpi8-1 35. While the absence of major developmental phenotypes in atpgap1 plants is surprising, given observations in animals, they are in line with a recently published analysis of AtPGAP1 in Arabidopsis 15.

PrpS localization at the plasma membrane is not affected in atpgap1 mutants

One reason why SI might be defective in atpgap1 mutants could be that PrpS cannot localize to the plasma membrane, as some GPI-APs have been shown to play a crucial role in the proper localization of other plasma membrane proteins 36,37. However, confocal imaging of PrpS–GFP in wild-type and atpgap1 mutant roots and pollen tubes showed that PrpS–GFP did reach the plasma membrane (Figure 5F, G). Similar to PrpS immunolocalization reported in Papaver pollen tubes 18, PrpS–GFP was localized to the endomembrane system as well as the plasma membrane; its localization was similar in wild-type and atpgap1 mutant pollen tubes (Figure 5G). This provides evidence that lack of PGAP1 does not perceptibly affect the localization of PrpS, so is unlikely to be a reason for the failure of SI.

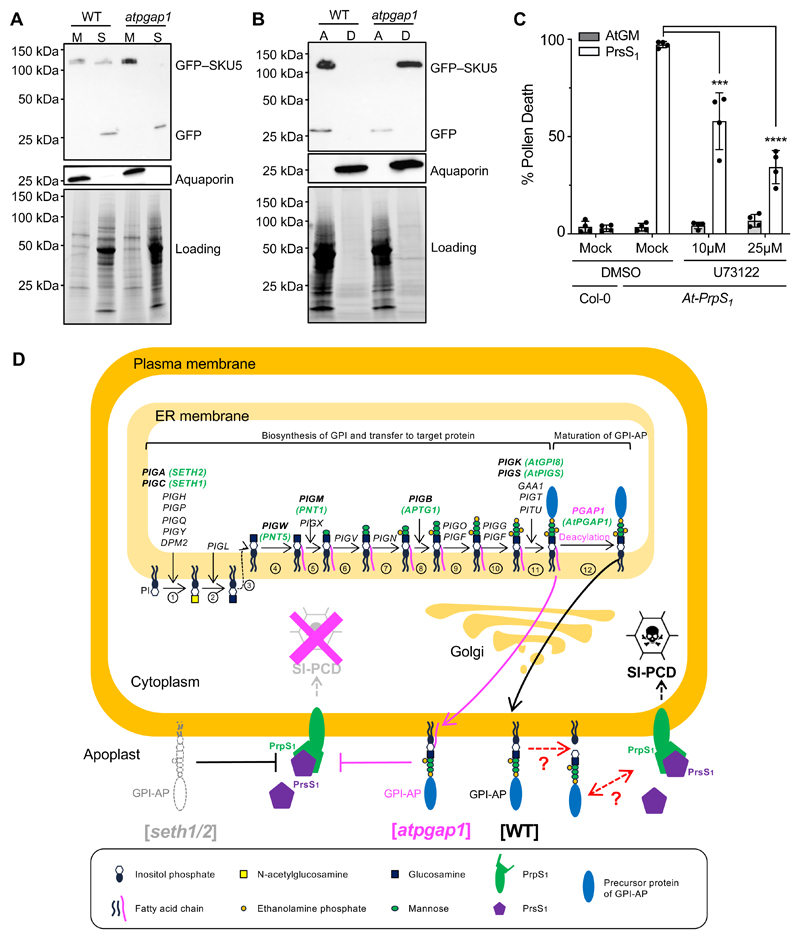

Inositol deacylation by AtPGAP1 is required for release of GFP–SKU5

Besides their localization in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, many GPI-APs in mammals are cleaved and released into the extracellular space; this can be mediated by PLC activity and is important for many cellular processes in mammals, including adhesion, proliferation, survival and oncogenesis 9,13. We therefore examined a role for AtPGAP1 mediated GPI-AP remodeling in planta. In wild-type Arabidopsis, we detected GFP–SKU5 in both membrane and soluble fractions (Figure 6A); this is consistent with a report that SKU5 can be cleaved and released into the apoplast 29. In contrast, in the atpgap1 mutant, GFP–SKU5 was exclusively detected in the membrane fraction (Figure 6A). Moreover, using Triton X-114, GFP–SKU5 was detected primarily in the aqueous phase in wild type, whereas most GFP–SKU5 was present in the detergent phase in the atpgap1 mutant (Figure 6B). Thus, in the absence of AtPGAP1, GFP–SKU5 was more hydrophobic and was retained in the membrane. This provides evidence that cleavage and release of GFP–SKU5 (and likely other GPI-APs) from the membrane requires GPI inositol deacylation by AtPGAP1 in vivo.

Figure 6. Evidence and a model for a requirement of GPI-APs at the plasma membrane for SI.

(A) Membrane (M) and soluble (S) fractions from WT and atpgap1 (atpgap1-c1) plants were extracted and localization of GFP–SKU5 (~120 kDa) proteins were analyzed on western blots. In the WT, GFP–SKU5 was detected in both fractions, but in the atpgap1 mutant, GFP–SKU5 was only detected in the membrane fraction, consistent with defective cleavage. Aquaporin (~26 kDa) is shown as a control for membrane extraction; loading control shows signals from a PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Precast gel (Bio-Rad).

(B) Whole proteins were extracted using 2% Triton X-114 extraction buffer, partitioned into aqueous (A) and detergent (D) phases. Western blot analysis showed that GFP–SKU5 (~120 kDa) was primarily enriched in the aqueous phase in the WT, but in the atpgap1 mutant it was primarily detected in the detergent phase, revealing that mutation of AtPGAP1 resulted in an increase of GFP–SKU5 hydrophobicity. Aquaporin (~26 kDa) is shown as a control for membrane extraction; loading control shows signals from a PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Precast gel (Bio-Rad).

(C) Col-0 and At-PrpS1 pollen grains were pretreated with the PLC inhibitor, U73122, or solvent (Mock) before subject to SI induction (PrsS1) or control treatment (AtGM) in vitro and samples were co-stained with FDA and PI 6h after treatment. Four independent experiments were carried out; 100-200 pollen grains were counted for each treatment. At-PrpS1 pollen treated with recombinant PrsS1 and mock solvent had high levels of death; treatment of At-PrpS1 pollen with recombinant PrsS1 and U73122 resulted in significant lower levels of death. This suggests that cleavage of GPI-APs by PLC is required for mediating SI-induced death of pollen.

(D) GPI-anchoring is a post-translational modification involving several phases which have been established in mammals and yeast. First, biosynthesis of the GPI involves a series of events [steps 1-10]. Once the core GPI is assembled [step 10], the target precursor protein (blue sphere) is transferred to the GPI by a GPI transamidase complex [step 11]. The nascent immature GPI-AP then undergoes remodeling; the first of these is deacylation [step 12], involving PGAP1, which we identified in this study (indicated in pink). After this, several other PGAP genes (not shown) mediate further modification during the transport from ER to the Golgi and then to the plasma membrane. The genes involved in GPI biosynthesis identified in humans are indicated in black; genes identified in plants are indicated in green. Knockouts of genes early in the biosynthetic pathway in mammals result in lack of expression of GPI-APs at the plasma membrane; in plants homozygous knockouts of the orthologs of PIG-C and PIG-A, SETH1 and SETH2, are lethal. We show in this study that mutation of SETH1 or SETH2 in At-PrpS1 pollen alleviates SI-induced pollen death. By analogy to animal systems, it is likely that the seth1/2 mutants lack GPI-APs at the plasma membrane (grey outline). Our data implicate GPI-APs at the plasma membrane are required for the SI response, as the normal SI-PCD response is prevented in their absence. After generation of the nascent GPI-APs, the acyl chain linked to inositol is removed by the GPI-deacylase, PGAP1 [step 12]. In the atpgap1/hld1 mutant, this step does not occur. As a consequence, the GPI-APs retain their inositol-linked acyl chain (indicated in pink), giving a 3-footed configuration responsible for retaining the GPI-AP in the plasma membrane in mammalian cells. Here we provide evidence that this is also the case in plants. We show that knockout of PGAP1 completely prevents SI, resulting in full fertility. This demonstrates that inositol deacylation, required for maturation of GPI-APs, is critical for the SI response. We propose that during an incompatible SI induction when the ligand PrsS interacts with plasma-membrane localized PrpS, this S-specific interaction may require interaction (direct or indirect) with (unknown) GPI-APs. Cartoon adapted from 9.

See also Figure S5.

AtPGAP1 regulates SI possibly by affecting PLC-mediated release of GPI-APs

As cleavage of membrane-bound GPI-APs is prevented by the “three-footed” configuration in mammalian and yeast PGAP1 mutants 9,12,30, it is conceivable that the prevention of SI by the AtPGAP1 mutation is caused by failure to cleave GPI-APs at the plasma membrane. Mammalian pgap1 cell lines lacking a GPI inositol deacylase have GPI-APs that are resistant to PLC-mediated cleavage in vitro 12. Although extracellular PI-PLCs were proposed by mammalian and plant researchers to allow cleavage of GPI-APs at the plasma membrane 38-40, the actual PLCs have not yet been identified. However, in Trypanosomes, a GPI-PLC at the external face of the plasma membrane has been identified as responsible for cleavage of the GPI-anchor of a variable surface glycoprotein 41. We therefore investigated whether PLC inhibitors might prevent SI, using the in vitro SI-bioassay. We could not test their effect on SI-induced pollen tube growth inhibition as pollen tube growth requires PLC activity 42,43, so we examined if they prevented SI-induced death of pollen. At-PrpS1 pollen pretreated with U73122 had significantly alleviated SI-induced cell death (a reduction of ~40% at 10 μM, p<0.001; and ~63% at 25 μM, p<0.0001; Figure 6C). Pretreatment with ET-18-OCH3 and C48/80 also showed similar alleviation of SI-induced death of incompatible pollen (Figure S5). The reduction in death by PLC inhibitors shows that a PLC/PLC-like activity is required for SI-induced pollen death, suggesting a possible role for cleavage of GPI-APs by PLC/PLC-like enzyme during SI. As SI is prevented by the “three-footed” GPI-AP configuration resulting from the AtPGAP1 mutation, our evidence is not only consistent with the idea that GPI-APs play a key role in SI, but that the prevention of their release from the plasma membrane is likely to be responsible for the breakdown of SI in the atpgap1 mutant plants.

Discussion

Over 250 GPI-APs have been predicted in Arabidopsis 4,44; despite recent advances in our knowledge of GPI-APs in plants, information on their functional roles remains limited. Here we identified a plant PGAP1 orthologue as essential for the Papaver SI-response. Although GPI-APs are involved in many important developmental processes in eukaryotes 31,35,45,46, the functional role of GPI remodeling at a whole-organism phenotypic level remains unclear. Our findings reveal that prevention of GPI-AP deacylation of restores self-fertility in an SI line. This points to a pivotal role for correctly remodeled GPI-anchored proteins in incompatible pollen recognition and/or rejection in Papaver SI. These data provide an important demonstration of the functional importance of GPI-remodeling and inositol deacylation in planta. Our findings open up new avenues to explore the role of GPI-AP modifications in plant cells. While the specific GPI-APs involved and the mechanistic consequences of their remodeling remain to be elucidated, our characterization of the impact of loss of this GPI-remodeling factor on SI provides valuable insights into the roles of the plant GPI pathway and raises several interesting questions.

Key differences and similarities between PGAP1 function in plants and animals

In animals, little is known about the physiological functions of PGAP1 apart from its biochemical role in deacylation in the GPI-anchoring pathway 12 and the pathological consequences of PGAP1 mutations 30,34,45,46. PGAP1 knock-out mice display serious developmental defects 34 and humans with a null mutation in PGAP1 suffer from intellectual disabilities and encephalopathy 30,34,45,46. Thus, retention of an extra acyl chain in GPI anchors causes severe developmental defects in mammals. A recent report identified a PGAP1 orthologue (AtPGAP1/At3g27325) in A. thaliana 15 and provided evidence that it functions as a GPI inositol-deacylase in plant cells, though it did not provide any data relating to biological function in a whole-plant context. Both this study and ours show that, in contrast to mammalian PGAP1 mutants, Arabidopsis hld1/atpgap1 mutant plants display largely normal development 15. Why there is this major difference between plants and mammals is an interesting question to be addressed in the future. The various hld1/atpgap1 mutant alleles isolated from our SI suppressor screen provide a valuable resource to investigate this question.

We found that in our atgap1 knockout plants, the GPI-AP reporter GFP–SKU5 was present at the plasma membrane at levels comparable to the wild type. This is similar to the situation in animal pgap1 knockout cells where, although transport of GPI-APs was delayed, plasma membrane levels of GPI-APs were not significantly decreased 9,12. Although it was recently reported that GPI-APs accumulated in the ER in an atpgap1 knockout 15, this ER retention was less extreme in our study. This difference is likely to be due to the use of the strong 35S promoter, as over-expression will exacerbate ER retention, which in turn may explain the strong ER-localized signal observed in the earlier study 15. Our approach, using stable transformants with a native promoter is likely to be nearer to the endogenous expression levels. Nevertheless, both studies show that GPI-APs can successfully reach the plasma membrane in the absence of AtPGAP1 function.

Loss of AtPGAP1 does not cause a deficiency of GPI-APs or PrpS at the plasma membrane

Our identification of AtPGAP1 implicates involvement of GPI-APs in the SI response. Many GPI-APs, for example, the widely studied GPI-AP LORELEI (LRE) and LORELEI-LIKE GPI-APs (LLGs) LLG1/2/3, play central roles in plant growth and development 47,6 and their presence at the plasma membrane is critical for their function in regulating normal development. The absence of a severe developmental phenotype in the atpgap1 mutants suggests that critically important GPI-APs are largely correctly expressed, localized, and functional in the absence of AtPGAP1. Thus, loss of PGAP1 function does not affect the targeting of crucial GPI-APs required for normal development. This provides strong evidence that GPI-AP targeting to the plasma membrane is not likely to be the defect underlying SI breakdown in atpgap1 mutants (Figure 6D). Another theoretical possibility is that the lack of GPI-APs affect PrpS localization, as it is well established in both animal and plants that some GPI-APs act as chaperones and can play a crucial role in the correct localization of plasma membrane proteins 36,37. For example, in Arabidopsis, the absence of the GPI-AP LLG1 affects plasma membrane localization of the Receptor-like Kinases (RLKs) FERONIA (FER) and FLAGELLIN-SENSING 2 (FLS2) 36,37. Although PrpS is a pollen plasma membrane-localized protein, it is clearly not a GPI-AP, so cannot be a substrate of AtPGAP1 48. However, a possible explanation of why SI is defective is that PrpS is not localized to the plasma membrane in the atpgap1 mutants because a crucial GPI-AP that acts as a chaperone is missing. As our data show that PrpS–GFP reaches the plasma membrane and has a very similar localization in wild-type and atpgap1 mutant pollen tubes and root cells, the loss of the SI phenotype is unlikely to be due to the incorrect localization of PrpS. Thus, it seems that neither GPI-AP nor PrpS localization is defective in the atpgap1 mutant plants (Figure 6D).

Implication of a potential role for GPI-APs in cell-cell signaling in Papaver SI

GPI-APs also play a key role in cell-cell signaling as co-receptors, including enhancing receptor-ligand interactions through association with partner receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and their ligands 36,37. Malectin-like RLKs (CrRLK1Ls) play critical roles in many interactions 49 and their interaction with GPI-APs in regulating plant reproduction, including pollen tube reception by the female gametophyte 47,50-52 has been intensely studied. For example LRE functions as a co-receptor for the CrRLK1L, FER 36, interacting with the ligand, RALF1. Pollen-specific-expressed LLG2/3 interacts with FER homologs ANXUR1/2 (ANX1/2) and Buddha’s Paper Seal 1/2 (BUPS1/2), and responds to RALF4/19 peptide signals to regulate pollen tube growth 53. Thus, these RLKs and GPI-APs form a receptor-coreceptor complex to perceive RALF peptide signals. While PrpS is not a GPI-AP or a RLK, it interacts with its S-specific ligand, PrsS to mediate the SI signaling pathway 20. Thus, its activity and interaction with PrsS or other proteins at the extracellular face of the plasma membrane might be regulated by GPI-APs (Figure 6D). Through comparison with what is known about well characterized GPI-APs, our data here raise the possibility that GPI-APs may be involved in PrpS interaction with its ligand PrsS.

As the ectopic “SI-like PCD” response in Arabidopsis roots 25 also requires AtPGAP1, it appears that broadly expressed GPI-APs, rather than those specifically involved in reproduction, are involved in SI. Interestingly, SKU5, which regulates directional root growth, is a member of a gene family containing pollen-expressed SKS11/12, which control pollen tube growth 54. As well as playing a key role in cell-cell signaling during reproduction and development, GPI-APs also participate in pathogen responses 37,47,55. An important component of innate immunity in plants is the interaction of RLKs with ligands to activate signaling to defense mechanisms that restrict pathogen invasion 56. For example, FLS2 is a leucine-rich repeat RLK that recognizes Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs), e.g. flagellin 57. The GPI-AP LLG1 plays a key role in these interactions, by constitutively associating with PAMP RLKs in the presence of flagellin. In this way, LLG1 plays an important role in plant innate immunity, functioning as a key component of PAMP-recognition immune complexes, modulating their ability to regulate disease responses 37. As the LLG1 clearly participates in several signaling pathways, this raises the possibility that some GPI-APs, receptors and signaling ligands have some common evolutionary origin.

Although the genetic basis of the Papaver and Brassica SI systems are quite different, they both utilize highly polymorphic plasma-membrane localized S-determinants (PrpS and SRK) that interact with highly polymorphic ligands (PrsS and SCR/SP11), which results in the recognition and rejection of “self” pollen. PrsS and SCR/SP11are cysteine-rich peptides, which are thought to be distantly related to the defensins utilized in plant innate immunity. Like the plant innate immune system, Papaver SI triggers a signaling pathway leading to PCD. While the components involved differ, there are distinct broad similarities between SI and the plant immune response 58,59, which raises the intriguing scenario of possible evolutionary parallels between SI systems and plant innate immunity systems. This has been proposed several times 60-63. Our findings here, showing that GPI-APs play a critical role in regulating Papaver SI, hint of further evidence for this functional diversification of key components involved in cell-cell recognition and signaling pathways regulating growth/development and that innate immunity in plants may also be utilized by these SI systems. Furthermore, as the Brassica SRK is a receptor kinase, it raises the possibility that GPI-APs may potentially be also involved in regulating this SI system. Thus, our study raises unanswered questions leading to several new avenues of research to be explored in the future.

How might PGAP1 work in Papaver SI?

It has been proposed that the lack of GPI deacylation disturbs GPI anchor-mediated signal transduction in animals 34; here we show that prevention of deacylation of GPI-APs in the atpgap1 mutants affects SI, which utilizes signaling to reject incompatible pollen. Cleavage and release of GPI-APs from the plasma membrane is prevented by the “three-footed” configuration in mammalian pgap1 mutants 9,12,30; our data suggest that cleavage of GPI-APs may play an important functional role in the SI context. Our observations on GFP–SKU5 suggest that GPI-APs still reach the plasma membrane in atpgap1 mutants but cannot be released into the extracellular space owing to their “three-tailed” configuration. Furthermore, our data on alleviation of SI by PLC inhibitors are consistent with a model in which prevention of SI by the AtPGAP1 mutation is caused by a failure to cleave GPI-APs at the plasma membrane (Figure 6D). How this cleavage affects GPI-APs and their function in plants will be an intriguing aspect for future research. It is tempting to speculate that cleavage of GPI-APs by PLC-like enzymes is required for PrpS-PrsS function in the SI process (Figure 6D). As such, our findings pave the way for both the identification and characterization of particular GPI-APs as well as putative PLC-like enzymes in plants involved in the SI response.

In conclusion, our study opens new avenues for research into the involvement and regulation of GPI anchoring in SI, as well as the investigation of the functional implications of GPI-remodeling in a plethora of GPI-APs in plant signaling processes in general.

Star Methods

Resource Availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Moritz Nowack (Moritz.Nowack@psb.vib-ugent.be).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown as described in25. Briefly, chlorine gas sterilized seeds were sown out on LRC2 plates (2.15 g.L-1 MS basal salts (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.1g.L-1 MES, pH adjusted to 5.7 with KOH, 1.0 % Plant Tissue Culture Agar NEOGEN), and kept at 4 °C for three days before transfer to a growth chamber for vertical growth with continuous light emitted (white fluorescent lamps, intensity 120 μmol.m2.s-1), at 22 °C. Seedlings were transferred to Jiffy pots in soil and grown under glasshouse conditions under a 16h light/8h dark regime at 22 °C.

Papaver rhoeas plants raised from seed of known SI genotypes derived from the Suttons 'Shirley Single Mixed' cultivar were used as experimental material for obtaining mRNA for the cloning of P. rhoeas PrPGAP1 gene and for pollen used for the antisense/sense oligonucleotide experiments. P. rhoeas plants were field grown. Fresh, dry pollen was collected from newly opened flowers and stored over silica gel at -20 °C, until needed.

Method Details

EMS mutagenesis and mutant screening of plant material

The self-incompatible Arabidopsis thaliana (At-SI) lines provide an easy macroscopic readout of SI-PCD, as self-pollinated At-SI lines are largely sterile and do not form elongated siliques. T2 seeds of At-SI lines were collected and sown on LRC2 plates containing BASTA (10 μg.ml- 1). Single insertion transgenic At-SI lines were obtained by selecting lines showing ~75% of BASTA resistance. Homozygous lines were obtained by selecting lines whose T3 seeds showed 100% BASTA resistance. As only ~50 seeds could be harvested from an At-SI plant, selected At-SI lines were propagated for two further generations to collect enough seeds for EMS mutagenesis. EMS mutagenesis was carried out as described in64. M1 At-SI seeds after EMS mutagenesis were sown in Jiffy pots, germinated and grown in greenhouse. The first screen was carried out ~10 days after flowering. Mutants showing longer siliques were selected. For M1 plants that did not show this phenotype, the primary inflorescences were cut back and a second screen was carried out ~2 weeks later. In total, ~50,000 M1 plants were screened and 40 mutants were identified. After eliminating those with transgene mutations, altered PrpS1–GFP expression levels, or pseudo-fertilization, 12 mutants remained; they were named highlander1s (hld1s).

To eliminate the effect of the mosaic nature of the M1 genetic background, M1 hld1 mutants (male) were backcrossed with the parent At-SI line (female) to obtain the backcross1 (BC1) generation of hld1 mutants. To reduce the number of background single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) caused by EMS mutagenesis, BC1 hld1 mutants were backcrossed again with the parent At-SI line to obtain the BC2 generation (see Figure S1).

WGS, backcrosses and SNP analysis to identify the causal gene for the hld1 mutants

As the hlds were gametophytic mutations, after backcrossing with the non-mutagenised parent, any unlinked SNP generated by the EMS mutagenesis segregated 1:3 in the pool of mutant individuals of the F1 population of the second backcross (BC2), whereas the causative SNP segregated 1:166. Calculating the SNP ratio in the BC2 population allowed us to identify the causal mutation region. For each of the hld1 mutant lines (hld1-3/5/7/19/24/25), leaf disc samples from 50 self-compatible BC2 plants were pooled, followed by DNA extraction using a CTAB-based protocol65, and whole genome re-sequencing (WGS) using Illumina next generation sequencing (NGS) platform. The At-SI line was also sequenced as the background control. SNPs were identified using SHOREmap23. Analysis of all the SNPs of the six hld1 mutants revealed six different nonsynonymous mutations in a single gene, At3g27325. At3g27325 is the only gene whose mutation was found in all the six mutants analyzed, therefore was analyzed further as a promising candidate gene.

Cloning, transgenic and T-DNA lines

All the expression vectors were generated using Greengate cloning67, Gibson assembly (New England BioLabs), or Gateway cloning (Invitrogen). High-fidelity Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) was used for all the DNA fragment amplification. All the clones were verified through Sanger sequencing.

The expression clone pFASTGreen-AtPGAPpro:mCherry–cAtPGAP1 and pFASTGreen-AtPGAP1pro:mCherry–cAtPGAP1(S218A) was generated using Greengate cloning, during which entry clones pGG-A-AtPGAP1pro-B, pGG-B-mCherry-C, pGG-C-cAtPGAP1-D or pGG-cAtPGAP1(S218A)-D, pGG-D-linker-E, pGG-E-G7T-F, and pGG-F-linker-G were cloned into Greengate destination vectors pFAST-GK-AG25. The Greengate entry clone pGG-B-mCherry-C, pGG-D-linker-E, pGG-E-G7T-F, and pGG-F-linker-G were obtained from PSB Plasmid Vector Collection (https://gatewayvectors.vib.be/collection). The Greengate entry clone pGG-A-AtPGAP1pro-B was obtained through Gibson assembly. The 2755 bps upstream of At3g27325.2 translational start site was amplified as the AtPGAP1 promoter (AtPGAP1pro) sequence. As there is a BsaI restriction site within the AtPGAP1pro sequence, two AtPGAP1pro fragments were separately amplified using primer sets 665/666 and 667/668 (detailed primer information can be found in Supplemental Table S5), respectively, with Col-0 Arabidopsis gDNA as the template to mutate the BsaI site, and assembled into BsaI linearized pGGA000 entry vector backbone using Gibson assembly. To make the Greengate entry clone pGG-C-cAtPGAP1-D, AtPGAP1 cDNA (cAtPGAP1) was amplified and cloned into pJET1.2 using CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit (ThermoFisher).

There are three different AtPGAP1 splice variants according to TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org) annotation. The coding region of AtPGAP1.1 was amplified in this experiment. As there are 3 BsaI restriction sites within the coding region of cAtPGAP1.1, cAtPGAP1.1 was amplified through a two-step protocol. Four cAtPGAP1.1 fragments were amplified using primer sets 732/675, 676/677, 678/679, and 680/683 with Arabidopsis seedling cDNA as the template. These four DNA fragments were assembled into cAtPGAP1.1 using overlap PCR. The resulting PCR products were cloned into pJET plasmid vector backbone to obtain the Greengate entry clone pGG-C-cAtPGAP1-D. To make the Greengate entry clone pGG-C-cAtPGAP1(S218A)-D, two cAtPGAP1(S218A) fragments were amplified using primer sets 732/834, 833/683 with pGG-C-cAtPGAP1-D as the template. Mutations in the primers were designed to change Serine 218 to Alanine. These two PCR fragments were assembled into cAtPGAP1(S218A) using overlap PCR, after which the resulting PCR products were cloned into pJET plasmid vector backbone to obtain the Greengate entry clone pGG-C-cAtPGAP1(S218A)-D. The expression vectors were transformed into GV3101 Agrobacterium tumefaciens competent cells. The floral-dipping method was adopted to stably transform homozygous At-SI/hld1-7 Arabidopsis plants to obtain At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1 and At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1(S218A) lines.

To generate new AtPGAP1 mutant alleles, 4 gRNAs (Table S5) were designed using CRISPOR68 and cloned into BbsI linearized Greengate entry vectors pGG-A-AtU6-26-B, pGG-B-AtU6-26-C, pGG-C-AtU6-26-D, and pGG-D-AtU6-26-E respectively via Gibson assembly. The resulting Greengate entry modules were assembled into pFASTGK-pUbi-Cas9-AG together with pGG-E-linker-G to generate expression vector pFASTGK-CRISPR-AtPGAP1. This was transformed into At-PrpS1 background line via Agrobacterium-mediated floral-dipping, as the non-mutagenized parent line At-SI is self-incompatible and unfeasible for transformation. Atpgap1-c1 and atpgap1-c2 alleles were screened from T2 Cas9-free seedlings and used for further experiments. At-PrpS3/atpgap1 and UBQ10pro:PrpS1/atpgap1 were generated by crossing At-PrpS3 22 or UBQ10pro:PrpS1 25 with atpgap1 (atpgap1-c1, atpgap1-c2, and hld1-7 in the WT background).

The expression clones UBQ10pro:PrpS1–GFP were generated using Gateway cloning, by recombining entry vectors pEN-L4-UBQ10pro-R1, pEN-L1-PrpS1-L2 25 and pEN-R2-GFP-R3 into Gateway destination vector pB7m34GW using LR Clonase II plus enzyme (Invitrogen). The expression vectors were transformed into GV3101 Agrobacterium tumefaciens competent cells and transformed to wild-type Col-0 Arabidopsis plants. AtPGAP1 mutant allele was introduced into UBQ10pro:PrpS1–GFP line by conventional crossing.

Seeds of T-DNA lines, seth1-2 (SAIL_674_B03) and seth2 (SALK_039599) were obtained from The Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Center (NASC). We introduced seth1-2 and seth2 mutant alleles10 into the At-PrpS1 background by crossing and generated heterozygous At-PrpS1/seth1-2+/- and At-PrpS1/seth2+/- lines. Primers used for genotyping these two T-DNA mutants can be found in Table S5. Genotyping of plants was carried out using Phire Plant Direct PCR Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cloning of PrPGAP1

To clone the P. rhoeas PrPGAP1 gene, a degenerate primer set 961/965 was designed based on the highly conserved region revealed by sequence alignment of A. thaliana, Papaver somniferum, and Oryza sativa PGAP1 genes. PCR using P. rhoeas DNA as template resulted in a DNA product of ~3300 base pairs, which was subsequently cloned into the pJET1.2 cloning vector (ThermoFisher). Sanger sequencing and subsequent sequence alignment analysis showed >90% identity between the PGAP1 coding regions of P. somniferum and P. rhoeas. Therefore, instead of 5’ and 3’ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) experiments, we cloned the PrPGAP1 directly, using primer sets (1098/1088, 1086/1093, 1103/1111, 1112/1106, see Table S5), which were designed according to mRNA sequence of P. somniferum PGAP1. The cDNA sequences of two PrPGAP1 alleles (PrPGAP1a and PrPGAP1b) were obtained and have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number MZ781963 and MZ781964.

Triton X-114 assay, PI-PLC assays, and Western blots

Three-day-old A. thaliana seedlings were collected into a 2 mL tube with 3 steel beads (3 mm) and frozen in liquid N2. Frozen samples were homogenized using a grinding mill (Retsch MM 400) at 20 Hz for 3 x 40 s. For Triton X-114 assays, 2% Triton X-114 extraction buffer [100mM Tris-HCl pH=7.5, 150mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 2% Triton X-114 (Sigma-Aldrich), 1x cOmplete protease inhibitor (Roche)] was added to the homogenized samples. Triton X-114 was pre-processed as described in 69 before being added to extraction buffer. Samples were centrifuged at 21,000g at 4 °C, and the supernatant retained. Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford (Bio-Rad) assay. To separate the detergent and aqueous phases, samples were incubated at 37 °C for 10 mins followed by centrifugation at 21,000g for 10 mins70. The aqueous upper phase was transferred to a new tube. Proteins from the detergent and aqueous phases were precipitated using MeOH/CHCl3 71 and dissolved in 1x loading buffer.

PI-PLC assays were modified from protocols published by71,72. In brief, membrane protein extraction buffer [100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25% (w/w) sucrose, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM KCl, 2x cOmplete protease inhibitor (Roche)] was added to the homogenized samples. Samples were centrifuged (600 g, 3 mins) and supernatants were kept as whole protein extracts. For the membrane fraction, supernatants were diluted with equal volume of water and centrifuged at 21,000g (2 h., 4 °C) and pellets resuspended in PI-PLC treatment solution [10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5% (v/v) glycerol]. PI-PLC (ThermoFisher) was added to a final concentration of 2 units.mL-1. For the mock control, 50% glycerol was added. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h, followed by centrifugation (21,000g for 2 h., 4 °C). The upper phase was transferred to a new tube and precipitated using MeOH/CHCl3 71; the pellet was dissolved in 1x loading buffer.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot were carried out as described in21 with minor modifications. Proteins were separated using 4-20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Precast gels (Bio-Rad). Stain-free signals were used as “loading controls”. Primary antibodies were incubated with membranes overnight at 4 °C in the PBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% skimmed milk powder. Anti–GFP (Takara), and anti-Aquaporins (Agrisera) were used at 1:1000 dilution, and anti-α-Tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used at 1:4000 dilution. Secondary HRP-conjugated anti-Mouse (GEHEALTH) and anti-Rabbit (GEHEALTH) antibodies were incubated with membrane for 1 h at RT with a 1:5000 dilution in the PBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% skimmed milk powder. WesternBright ECL HRP substrate (ADVANSTA) was used for detection.

A. thaliana seedling treatment with recombinant PrsS proteins

Recombinant PrsS protein treatment was performed as described in25. Briefly, PrsS proteins were dialysed in 1/5 LRC2 liquid medium at 4 °C and 10 μl PrsS proteins (10 ng.μl-1) added onto root tips of 4-day-old seedling on LRC2 plates. The plates were kept horizontal for 30 min before being placed back vertically in the growth chamber for 24 h before root length measurement. PrsS1 protein provided the “SI” treatment for the transgenic A. thaliana lines (UBQ10pro:PrpS1), with matching/cognate S-alleles in the seedling and protein; treatment with LRC2 liquid medium or recombinant PrpS3 proteins provided the controls.

Arabidopsis pollen SI in vitro bioassay

A. thaliana pollen was placed onto an 8-well chambered coverglass (Thermo Scientific Nunc Lab-Tek model number 155411) and A. thaliana pollen germination medium [AtGM; 15% (w/v) sucrose, 0.01% (w/v) H3BO3, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 2.5 mM Ca(NO3)2, and 10% PEG3350, pH=7.0 adjusted using KOH] modified from73 containing 10 ng.μl-1 recombinant PrsS proteins (SI treatment) was added. For controls, the PrsS proteins were omitted from the AtGM solution. Pollen grains were incubated at RT (~22 °C) for 6h and then fluorescein diacetate (FDA, 2 μg.ml-1) and propidium iodide (PI, 5 μg.ml-1) were added. Samples were examined using fluorescence microscopy (for setting up details, see the following Imaging section). For each sample, 100-200 pollen grains/tubes were scored for the number of FDA-positive (live) and PI-positive (dead).

For treatment with PLC inhibitors (U73122, ET-18-OCH3, C48/8074,75), a similar procedure was used. A. thaliana pollen was added to AtGM and pretreated with each PLC inhibitor for 1h prior to the induction of SI (addition of 10 ng.μl-1 recombinant PrsS protein). For the control, mock treatment, the equivalent volume of solvent was used.

Papaver rhoeas pollen SI bioassay with antisense oligonucleotide treatment in-vitro

As a transgenic approach with Papaver rhoeas is not possible, we used an alternative approach to knockdown PrPGAP1 by incubating P. rhoeas pollen with phosphorothioated antisense oligonucleotide designed against PrPGAP118,24. P. rhoeas pollen was hydrated for 0.5 h and incubated with poppy pollen growth medium (PrGM) containing 3 μM phosphorothioated oligonucleotides (Antisense-PrPGAP1 or Sense-PrPGAP1, designed using Sfold76, Table S5) and 0.5% (v/v) cytofectin (T201007H, Genlantis) for 2 h at RT before SI induction. Pollen viability were assessed using FDA (2 μg.ml-1) and PI (5 μg.ml-1) 10 h after SI treatment. Pollen tube lengths were measured using Fiji (https://fiji.sc/)77. Due to the limit of the imaging field size, pollen tubes which were longer than 600 μm (very rarely observed) were all recorded as 600 μm.

PGAP1 Phylogeny analysis

PGAP1 domain-containing proteins comprising 631 proteins across three eukaryotic kingdoms (Table S6), were downloaded from Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/family/PGAP1). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT (version 7.187). IQ-TREE (version 1.7-beta7) was used for the maximum-likelihood tree inference with 1000 bootstrap replicates (under the model of ‘JTT+R’, -alrt 1000 -bb 1000).

Imaging, image analysis and figure preparation

For PI staining A. thaliana seedling roots were mounted in 1/5 LRC2 medium containing 5 μg.ml-1 PI imaged (ex 561 nm, em 580-700 nm) with a PlanApochromat 20x objective (n/a 0.8) using a Zeiss LSM710 microscope.

For the in-vitro pollen SI bioassays, A. thaliana or P. rhoeas pollen was co-stained using FDA (2 μg.ml-1; ex 561 nm, em 580-550 nm) and PI (5 μg.ml-1; ex 488 nm, em 500-700 nm) and imaged with a Fluostar VISIR 25x/0.95 objective using a Leica SP8 confocal laser scanning system with a HyD detector.

GFP–SKU5 in A. thaliana seedling roots was imaged with a HCPL APO CS2 40x/1.10 objective using a Leica SP8 confocal laser scanning system with a HyD detector (ex 488 nm, em 500-550 nm). All images were processed and analyzed using Fiji (https://fiji.sc/)77.

Quantification and Statistical analysis

The statistical details of experiments can be found in the corresponding Figure legends. The results of statistical tests can be found in the corresponding Results section. Statistical tests were carried out using GraphPad Prism 8.0 for Windows.

Supplementary Material

Key Resources Table.

| Reagent or Resource | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse anti–GFP | Monoclonal Antibody (JL-8) | Takara | Cat#632381 |

| Rabbit anti-Aquaporin PIP1;3 | Aquaporin, plasma membrane intrinistic protein 1-3 polyclonal antibody produced in rabbit | Agrisera | Cat#AS09487 |

| Mouse anti-Tubulin | Monoclonal Anti-α-Tubulin antibody produced in mouse, clone B-5-1-2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T5168 |

| Secondary HRP-conjugated anti-Mouse | GEHEALTH | Cat#NA931 |

| Secondary HRP-conjugated anti-Rabbit | GEHEALTH | Cat#NA934 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E. coli strain: DH5a | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#18265017 |

| Agrobacterium strain: GV3101 | 78 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| PI-PLC | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#P6466 |

| U73122 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#U6756-5MG |

| ET-I8-OCH3 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#09262-5MG |

| Compound 48/80 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C2313-100MG |

| MS basal salts | Duchefa Biochemie | Cat#M0221.0050 |

| Agar No.4 - Plant Tissue Culture Agar | NEOGEN | Cat#NCM0250A |

| GLUFOSINATE-AMMONIUM PESTANAL (BASTA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#45520-100MG |

| GenePorter H Transfection reagent (cytofectin) | Genlantis | Cat#T201007H |

| Triton X-114 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#X114-500ML 9036-19-5 |

| Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | New England BioLabs | Cat#F530L |

| cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail | Roche | Cat#11697498001 |

| Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#F1303 |

| Propidium iodide (PI) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P4864-10mL |

| Recombinant PrsS1, PrpS3 proteins | 17 | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| T4 DNA Ligase (400.000 units/ml)67 | New England BioLabs 67 | Cat#M0202L_37612 |

| BsaI-HFv2 restriction enzyme | New England BioLabs | Cat#R3733 |

| NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly (Gibson assembly) | New England BioLabs 79 | Cat#C3019 |

| CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit | ThermoFisher | Cat#K1231 |

| Phire Plant Direct PCR Master Mix | Thermo Scientific | Cat#F160L |

| WesternBright ECL HRP substrate | ADVANSTA | Cat#K-12045-D50 |

| Bradford (Bio-Rad) assay | 80 | Cat#5000006 |

| Deposited data | ||

| PrHLD1a cDNA sequence | This paper | GenBank: MZ781963 |

| PrHLD1b cDNA sequence | This paper | GenBank: MZ781964 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Arabidopsis thaliana: wild type Col-0 | PSB-VIB | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: At-PrpS1 | 22 | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: At-PrpS3 | 22 | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: At-SI | 21 | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: At-PrpS3 | 21 | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: UBQ10pro:PrpS1 | 25 | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: UBQ10pro:PrpS1–GFP | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: hld1-3/5/6/7/17/18/19/24/25/30/37/39 | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: atpgap1-c1/2 | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: GFP–SKU5 | 29 | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: seth1-2 | 10 | SAIL 674 B03 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: seth2 | 10 | SALK 039599 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1 | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: At-SI/hld1/cAtPGAP1(S218A) | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis thaliana: gpi8-1 | 35 | N/A |

| Papaver rhoeas (Shirley variety) | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S5 for detailed oligonucleotides information | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pFAST-GK-AG | 25 | N/A |

| pFASTGreen-AtPGAPpro:mCherry–cAtPGAP1 | This paper | N/A |

| pFASTGreen-AtPGAPpro:mCherry–cAtPGAP1(S218A) | This paper | N/A |

| pFASTGK-pUbi-Cas9-AG | This paper | N/A |

| pFASTGK-CRISPR-AtPGAP1 | This paper | N/A |

| pB7m34GW | 25 | N/A |

| UBQ10pro:PrpS1–GFP | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Fiji | 77 | https://fiii.sc/ |

| GraphPad Prism version 8.0.0 for Windows, | N/A | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Pfam | 81 | http://pfam.xfam.org/family/PGAP1 |

| MAFFT (version 7.187). | N/A | https://myhits.sib.swiss/cgi-bin/mafft |

| IQ-TREE (version 1.7-beta7) | 82 | http://www.iqtree.org/ |

| Sfold | 76 | https://sfold.wadsworth.org/cgi-bin/index.pl |

| CRISPOR | 68 | http://crispor.tefor.net/ |

| SHOREmap | 23 | N/A |

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the PCD laboratory for critical comments on the manuscript, Ms. Freya De Winter and Mr. Karel Spruyt for technical assistance, and Prof. Elena Shpak (University of Tennessee) for providing gpi8-1 seeds. This research was financially supported by the European Research Council (ERC) StG PROCELLDEATH 639234 and CoG EXECUT.ER 864952 (MKN), Biotechnology, Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) grants BB/P005489/1 and BB/T00486X/1 (V.E.F-T., M.B.), Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) grant G011215N (M.T.), FWO grant 12I7417N (Z.L.), Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC) grant 201806760049 (F.X.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Z.L., M.K.N., V.E.F-T., and M.B. designed the study. Z.L., F.X., and M.T. performed the research and analyzed the data. Z.T. contributed to the PGAP1 phylogeny analysis. F.C. and L.S. contributed to the analysis of WGS data. Z.L., V.E.F-T., M.K.N. and M.B. wrote the manuscript with input from all the other authors.

Declaration of interests: The authors declare no competing interest.

Inclusion and diversity relating to authorship and attribution: One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as an underrepresented ethnic minority in science.

Data and code availability

cDNA sequence for PrPGAP1a and PrPGAP1b data have been deposited at the GenBank/EMBL database and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Ferguson MAJ, Williams AF. Cell-surface anchoring of proteins via glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol structures. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:285–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Low M, Saltiel A. Structural and functional roles of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol in membranes. Science. 1988;239:268–275. doi: 10.1126/science.3276003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borner GHH, Lilley KS, Stevens TJ, Dupree P. Identification of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Proteins in Arabidopsis. A Proteomic and Genomic Analysis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:568–577. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou K. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Proteins in Arabidopsis and One of Their Common Roles in Signaling Transduction. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1022. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujita M, Kinoshita T. GPI-anchor remodeling: Potential functions of GPI-anchors in intracellular trafficking and membrane dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Bio Lipids. 2012;1821:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desnoyer N, Palanivelu R. Bridging the GAPs in plant reproduction: a comparison of plant and animal GPI-anchored proteins. Plant Reprod. 2020;33:129–142. doi: 10.1007/s00497-020-00395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillmor CS, Lukowitz W, Brininstool G, Sedbrook JC, Hamann T, Poindexter P, Somerville C. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Proteins Are Required for Cell Wall Synthesis and Morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1128–1140. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez S, Rodriguez-Gallardo S, Sabido-Bozo S, Muñiz M. Endoplasmic Reticulum Export of GPI-Anchored Proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3506. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinoshita T. Biosynthesis and biology of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins. Open Biol. 2020;10:190290. doi: 10.1098/rsob.190290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalanne E, Honys D, Johnson A, Borner GH, Lilley KS, Dupree P, Grossniklaus U, Twell D. SETH1 and SETH 2 two components of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthetic pathway, are required for pollen germination and tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:229–240. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellai-Dussault K, Nguyen TTM, Baratang NV, Jimenez-Cruz DA, Campeau PM. Clinical variability in inherited glycosylphosphatidylinositol deficiency disorders. Clin Genet. 2019;95:112–121. doi: 10.1111/cge.13425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka S, Maeda Y, Tashima Y, Kinoshita T. Inositol deacylation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins is mediated by mammalian PGAP1 and yeast Bst1p. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14256–14263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujihara Y, Ikawa M. GPI-AP release in cellular, developmental, and reproductive biology. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:538–545. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R063032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luschnig C, S GJ. In: The Plant Plasma Membrane. Murphy AS, editor. Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Press; 2011. Posttranslational Modifications of Plasma Membrane Proteins and Their Implications for Plant Growth and Development; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernat-Silvestre C, Sanchez-Simarro J, Ma Y, Montero-Pau J, Johnson K, Aniento F, Marcote MJ. AtPGAP1 functions as a GPI inositol-deacylase required for efficient transport of GPI-anchored proteins. Plant Physiol. 2021;187:2156–2173. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiab384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takayama S, Isogai A. Self-incompatibility in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:467–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foote HCC, Ride JP, Franklin-Tong VE, Walker EA, Lawrence MJ, Franklin FCH. Cloning and Expression of a Distinctive Class of Self-Incompatibility (S) Gene from Papaver rhoeas L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2265–2269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheeler MJ, de Graaf BHJ, Hadjiosif N, Perry RM, Poulter NS, Osman K, Vatovec S, Harper A, Franklin FCH, Franklin-Tong VE. Identification of the pollen self-incompatibility determinant in Papaver rhoeas. Nature. 2009;459:992–995. doi: 10.1038/nature08027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bircheneder S, Dresselhaus T. Why cellular communication during plant reproduction is particularly mediated by CRP signalling. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:4849–4861. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkins KA, Poulter NS, Franklin-Tong VE. Taking one for the team: self-recognition and cell suicide in pollen. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:1331–1342. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Z, Eaves DJ, Sanchez-Moran E, Franklin FCH, Franklin-Tong VE. The Papaver rhoeas S-determinants confer self-incompatibility to Arabidopsis thaliana in planta. Science. 2015;350:684–687. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Graaf BarendH, Vatovec S, Juárez-Díaz JavierA, Chai L, Kooblall K, Wilkins KatieA, Zou H, Forbes T, Franklin F, Christopher H, Franklin-Tong VernonicaE. The Papaver Self-Incompatibility Pollen S-Determinant, PrpS, Functions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Biol. 2012;22:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneeberger K, Ossowski S, Lanz C, Juul T, Petersen AH, Nielsen KL, Jørgensen J-E, Weigel D, Andersen SU. SHOREmap: simultaneous mapping and mutation identification by deep sequencing. Nat Methods. 2009;6:550–551. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0809-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moutinho A, Camacho L, Haley A, Pais MS, Trewavas A, Malhó R. Antisense perturbation of protein function in living pollen tubes. Sex Plant Reprod. 2001;14:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Z, Xie F, Triviño M, Karimi M, Bosch M, Franklin-Tong VE, Nowack MK. Ectopic Expression of a Self-Incompatibility Module Triggers Growth Arrest and Cell Death in Vegetative Cells. Plant Physiol. 2020;183:1765–1779. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leebens-Mack JH, Barker MS, Carpenter EJ, Deyholos MK, Gitzendanner MA, Graham SW, Grosse I, Li Z, Melkonian M, Mirarab S, et al. One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants. Nature. 2019;574:679–685. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1693-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]