Abstract

Phytopathogenic bacteria inject effector proteins into plant host cells to promote disease. Plant resistance (R) genes encoding nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) proteins mediate recognition of functionally and structurally diverse microbial effectors, including transcription-activator like effectors (TALEs) from the bacterial genus Xanthomonas. TALEs bind to plant promoters and transcriptionally activate either disease-promoting host susceptibility genes or cell death-inducing executor-type R genes. It is perplexing that plants contain TALE-perceiving executor type R genes in addition to NLRs that also mediate recognition of TALE-containing xanthomonads. We will review recent findings on the evolvability of TALEs, which suggest that the native function of executors is not in plant immunity, but possibly in regulation of developmentally-controlled programmed cell death (PCD) processes.

Keywords: Xanthomonas, executor, programmed cell death (PCD), transcription activator-like effector (TALE), evolution, nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) protein

How did the TALE DNA binding domain evolve and what are its implications for plant breeding?

Transcription-activator like effectors (TALEs) from the plant-pathogenic bacterial genus Xanthomonas have attracted considerable attention in the scientific community due to their programmable DNA binding domain that can be engineered to bind DNA motifs of desired lengths, nucleotide composition, and epigenetic makeup [1–3]. Recent studies uncovered that native TALE DNA binding domains are highly evolvable and capable of rapidly adjusting their target specificity to either induce expression of disease-promoting plant susceptibility (S) genes or to avoid transcriptional activation of matching plant resistance (R) genes [4,5]. Herein, we will discuss the implications of these new findings in the context of recently developed molecular breeding strategies, whereby TALE-targeted S and R gene promoters have been engineered to generate crops with broad spectrum Xanthomonas resistance [6–10]. Moreover, we will discuss executors, a functionally and structurally unique plant R gene class that trap TALEs via their 5’ upstream DNA motifs causing transcriptional activation of downstream encoded cell death-inducing executor proteins [11]. We will review evidence suggesting that executor R genes have been mistakenly interpreted solely as components of the plant immune system, while their native function possibly lies in the execution of programmed cell death (PCD) as an integral part of developmental processes.

What are the functional domains that TALEs have evolved to activate transcription in eukaryotic host cells?

Bacteria inject TALE proteins into eukaryotic host cells where TALEs activate host gene transcription to increase susceptibility of the host. The functional domains of bacterial TALE proteins include i) nuclear localization signals (NLSs) that by interaction with eukaryotic importin α proteins facilitate the transfer into the host’s nucleus, ii) a DNA binding domain that mediates interaction with host promoters, iii) a transcription factor binding (TFB) motif domain that by interaction with the general transcription factor TFIIAγ, recruits the host’s RNA polymerase II complex, and iv) an activation domain (AD) that by yet unknown means stimulates eukaryotic transcription (Figure 1).

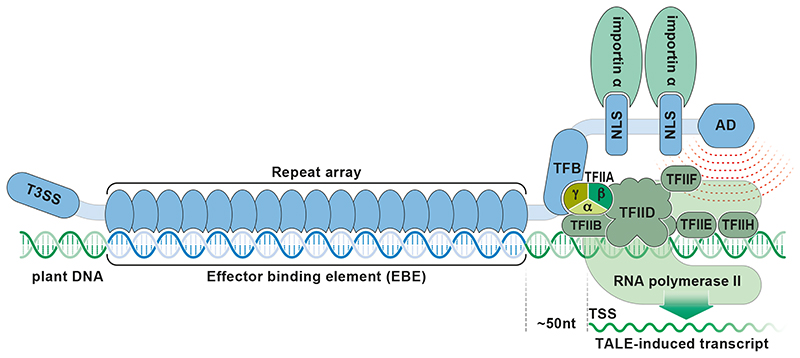

Figure 1. Transcriptional activation of plant gene by a TALE protein.

An N-terminal type III secretion signal (T3SS) marks effector proteins for translocation from the bacterial pathogen into the plant cytoplasm. Tandem-arranged repeat modules form a repeat array that binds in a sequence-specific fashion to a DNA target sequence (effector binding element; EBE). The transcription factor binding (TFB) domain mediates interaction with the gamma (γ) subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIA that is part of the host’s RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex. The C-terminal activation domain (AD) stimulates transcriptional activation. The transcriptional start site (TSS) of the TALE-induced transcript (green waved line) starts about 50-100 nucleotides downstream of the EBE. Notably, the TALE-induced TSS is typically distinct from the TSS of the corresponding native transcript.

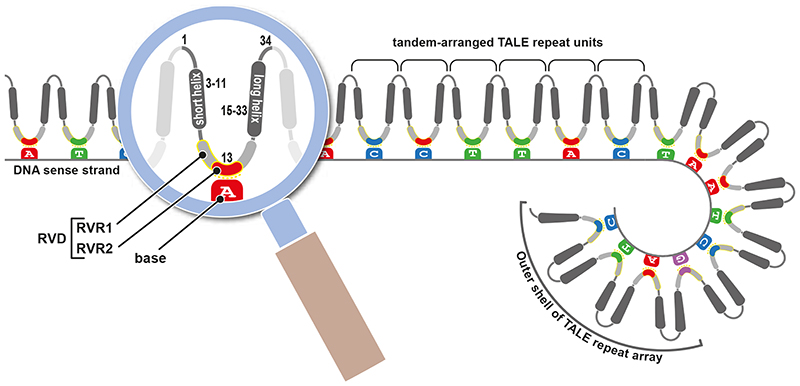

The DNA binding domain is the largest functional unit, located in the centre of the TALE polypeptide and is composed of a variable number (typically 15-20 modules) of almost identical, tandem-arranged 33-35 amino-acid modules, referred to as repeats. Each TALE repeat binds to one base in a given DNA target sequence (referred to as effector binding element; EBE) and the TALE repeats form collectively a superhelical structure that winds around target sequences in the DNA helix (Figure 2). TALE repeats differ from one another predominantly in residues 12 and 13, the repeat variable diresidue (RVD). Repeat residue 13, the base-specifying residue (BSR), faces towards the DNA bases in the EBE sense strand and defines the base preference of a given repeat. Notably, native Xanthomonas TALEs contain RVDs with pronounced base preference (‘specific RVDs’; e.g. “NI” pairs with adenine and “HD” pairs with cytosine) as well as RVDs that have either relaxed specificity (e.g. “NN” pairs with guanine or adenine) or no base preference (e.g. “NS”). RVDs with relaxed or no base preference are a typical feature of native TALE repeat arrays and probably enable TALEs to activate plant S genes across different accessions of a given host species even if these show single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within TALE EBEs. Mismatch tolerance of native TALE repeat arrays is presumably the cause of why TALEs typically not only activate the disease-promoting S gene, but also other plant genes that do not increase host susceptibility and that are likely off-targets. By contrast, in vitro assembled designer TALEs (dTALEs), fabricated for specific activation of user-defined target genes [12], typically only contain RVDs with pronounced base preference and therefore have generally few, if any, off targets.

Figure 2. Structural basis of TALE-DNA interaction.

TALE proteins bind to DNA by a variable number of tandem-arranged repeats, with each repeat pairing with one DNA base in the sense strand of matching EBEs. The TALE-DNA interaction is depicted in a simplified linear display (left) and the helical arrangement (right) where the TALE repeat array wraps around the helical structure of the DNA. Repeats are generally highly sequence related to each other with residues 12 and 13 being most variable and accordingly designated as repeat variable diresidue (RVD; highlighted by yellow frame). The repeat variable residue 1 (RVR1; residue 12) and RVR2 (residue 13) define DNA base preference of a given repeat. RVR2, also known as the base-specifying residue (BSR), makes the major contribution to the base preference of a given repeat. Residues 12-14 collectively form the DNA binding loop that is flanked by short and long helical regions. Tandem-arranged repeats wind around the DNA and form a superhelical structure. Given that the outer shell of the repeat array is formed by conserved repeat residues, its shape is likely not affected by variation in the RVD composition and thus will be mostly highly similar for each TALE protein. Please note the simplified display of the TALE protein where only the TALE-repeat array is depicted and not the N- and C-terminal parts of the TALE protein, which are displayed in Figure 1. Note that TALEs bind to double stranded DNA but that in this simplified depiction only the DNA sense strand is shown.

Base-preferences of all 400 possible two-amino acid combinations in the RVD position have been decoded experimentally [13,14] and accordingly, the preferred EBE can be predicted for any TALE based on its RVD composition. While the preferred EBE can be easily predicted for any given TALE, it remains challenging to predict whether or not DNA sequences related to the preferred EBE will indeed mediate TALE-dependent gene activation.

In summary, predictability of TALE DNA binding specificity provides indications on host target genes and the linked biological processes that a given TALE possibly manipulates. However, in silico prediction of TALE targets typically produces many false-positives, and experimental validation of these predicted targets is imperative to uncover TALE-manipulated plant processes.

How do TALEs manipulate plant processes to promote bacterial disease?

Xanthomonads populate plant intercellular spaces (the apoplast) and increase their virulence via injection of TALEs into plant cells. Upon injection, TALEs translocate to the nucleus, scan the host genome for compatible EBEs, then bind to and transcriptionally activate typically a handful of plant genes. Generally, TALEs target only one disease-promoting host S gene while all other TALE-target genes are likely off-targets. As such, TALE-activated host S genes that promote bacterial virulence have been identified for several Xanthomonas-host interactions [2,15]. The mechanistic basis of how S gene expression increases host susceptibility is most well understood for plant SWEET genes, which are transcriptionally activated by TALEs from xanthomonads infecting rice (Oryza sativa) [16,17], cotton (Gossypium spp.) [18], and cassava (Manihot esculenta) [19]. In non-infected plant tissue, expression of SWEETs is exclusive to phloem parenchyma cells whereby SWEETs mediate sugar efflux from the cytoplasm into the apoplast followed by sugar uptake into sieve element companion cells [20]. TALE-induced, ectopic expression of SWEETs results in a release of sugar from host cells into the apoplastic lumen, where increased sugar concentrations promote bacterial proliferation, most likely by serving as a carbon source for xanthomonads.

In Xanthomonas-host interactions where TALE-dependent S gene activation is crucial for bacterial pathogenicity, plant accessions where the S gene is not preceded by a TALE-compatible EBE will not support bacterial growth and will accordingly be resistant to Xanthomonas. The recessively inherited rice resistance genes xa13, xa25, and xa41 are such examples where naturally occurring DNA polymorphisms upstream of rice SWEET genes inhibit S gene activation by matching TALE proteins [16,21,22]. Recently, gene editing approaches have been used to mutate functional EBEs upstream of host S genes in rice and citrus plants to engineer pest resistant plants [23].

Continuous research on rice-infecting Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) strains has uncovered an arsenal of TALEs with distinct repeat arrays that bind to EBEs located within the 5’ upstream regions of OsSWEET11, OsSWEET13, and OsSWEET14 genes, all encoding functionally-equivalent sugar export channels, suggesting convergent evolution of Xoo TALEs. Knowledge of existing TALE repertoires in Xanthomonas species and their S gene targets facilitates mutagenesis of several EBEs in parallel, consequently generating EBE-depleted crops with broad-spectrum resistance to numerous Xanthomonas strains [7,24]. Ultimately, having the insight on TALE-targeted S genes and their upstream EBEs provides a basis to engineer pathogen-resistant crops.

Are TALE DNA binding domains evolving to promote disease or to avoid detection by the plant immune system?

TALE repeat encoding DNA segments (repeats) are almost identical in their DNA sequences and this sequence similarity is expected to favour evolvability of repeat arrays [25]. Therefore, are TALE repeat arrays with modified DNA target specificity positively selected for by evolutionary constraints? Indeed, such evolvability has been recently demonstrated for derivatives of PthA4, a TALE from the citrus (citrus spp.) pathogen Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc) that transcriptionally activates the host S gene CsLOB1 [4]. Notably, transcriptional activation of CsLOB1 is crucial to pathogenicity of Xcc since in planta growth of bacterial mutants lacking PthA4 is severely attenuated [4]. To study if Xcc would evolve in planta TALE repeat arrays that activate CsLOB1, in vitro mutagenesis was used to generate PthA4 derivatives, that due to modification of up to five PthA4 RVDs were no longer capable of transcriptional activation of CsLOB1. Repeated in planta incubation cycles of Xcc strains containing these PthA4 mutant derivatives resulted in recovery of evolved TALEs (eTALEs) that regained the ability to activate CsLOB1. Notably each of the CsLOB1-activating eTALEs had an RVD composition that was distinct from PthA4, and likely these eTALEs evolved by repeat rearrangements of the in vitro-generated PthA4 mutants [4].

Complementary experimental evolution studies were carried out on PthAW1, a TALE protein identified in Xcc that triggers cell death in sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) but not in other tested citrus varieties [4]. Repeated in planta incubation cycles resulted in PthAW1 derivatives that had lost individual repeats, presumably to escape detection by a yet unknown executor R gene in sweet orange. These observations demonstrate that the DNA binding specificity of TALE repeat arrays is shaped by evolutionary constraints.

Do EBE-depleted plant cultivars provide durable resistance to TALE-containing xanthomonads?

What are the implications of the observed evolvability of TALEs on recently engineered plant lines in which EBEs matching to known TALEs have been depleted? The use of such plants in agriculture would cause a strong selection pressure on the pathogen population towards eTALEs that regain the capability of activating S genes. It is also possible that Xanthomonas populations already comprise strains containing a large variety of eTALEs matching to different S gene upstream regions as observed for OsSWEET14 (Figure 3) and that the use of EBE-depleted cultivars will simply induce a shift in the population towards strains with TALEs that promote disease in the given host genotypes. Moreover, even if the CRISPR-engineered EBE-depleted plant varieties would offer no targets for any of the TALEs present in a pathogen population, a single S gene-activating eTALE in a given Xanthomonas strain will still be sufficient to regain susceptibility in such engineered crops. Given the evolvability of the TALE DNA binding domain it is conceivable that the occurrence of such resistance-breaking eTALEs is just a matter of time.

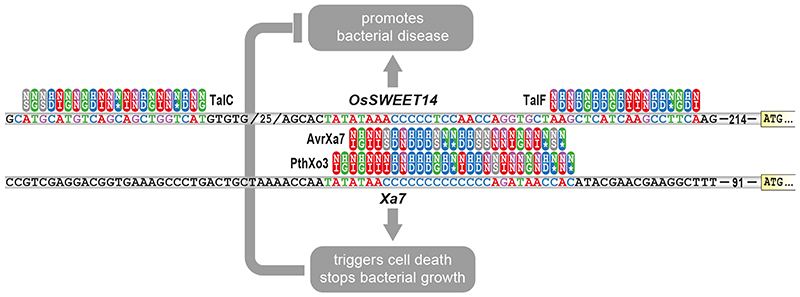

Figure 3. TALEs with a dual function that either promote disease or trigger plant resistance.

Strains of the rice pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae evolved distinct TALEs to transcriptionally activate the rice OsSWEET14 gene as depicted above. This includes the TALE proteins TalC, TalF, AvrXa7, and PthXo3. The rice executor R gene Xa7 contains in its 5’ upstream sequence an AvrXa7- and PthXo3-compatible EBE but not TalC- and TalF-compatible EBEs. TALEs are represented by repeats (ovals) with their RVDs (one-letter amino acid code). Colour coding indicates base preference of a given RVD. 5’ upstream nucleotide sequences of the rice S gene OsSWEET14 and the executor R gene Xa7 are shown in the upper and lower line, respectively.

How do host plants perceive the presence of TALEs?

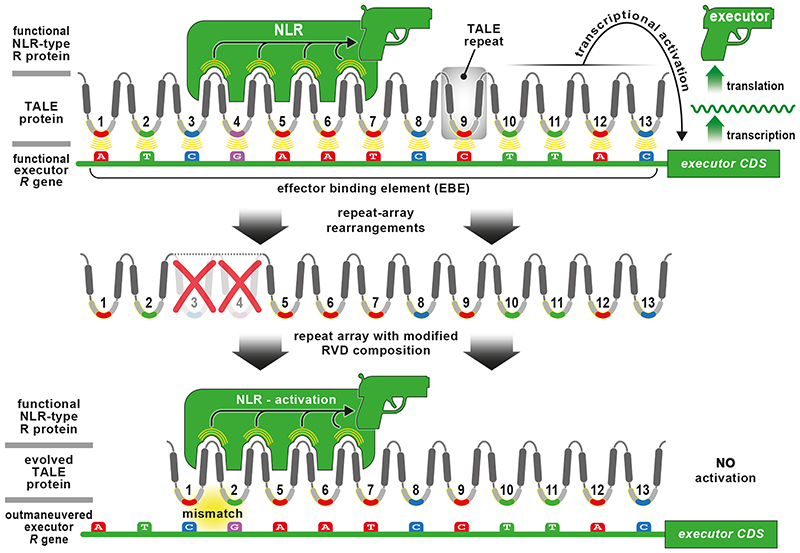

Molecular analysis of dominantly-inherited TALE-triggered plant-immune reactions uncovered two functionally distinct R gene classes: i) constitutively-expressed R genes encoding nucleotide-binding-leucine rich repeat proteins (NLRs) and ii) transcriptionally-controlled executor R genes (Figure 4). NLR proteins are defined by their unifying domain composition that enables members of this immune receptor class to either directly or indirectly sense structurally and functionally diverse microbial effectors and to trigger a defence reaction that typically correlates with HR cell death to inhibit proliferation of the strictly biotrophic pathogen Xanthomonas. Tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum) Bs4, rice Xa1, and rice Xo1 are three examples of TALE-sensing NLR proteins [26–30]. Notably, all three NLRs mediate detection of multiple TALEs with distinct RVD composition [26–28,31,32]. This suggests that these TALE-sensing NLRs recognize conserved non-RVD repeat residues that collectively constitute the outer shell of the superhelical structure formed by tandem arranged TALE repeats (Figure 2). Accordingly, rearrangements in TALE repeat arrays that change the RVD composition are not expected to affect these NLR-dependent defence reactions.

Figure 4. The impact of TALE repeat rearrangements on NLR- and executor-mediated recognition.

The displayed TALE protein is recognized either by a matching NLR protein or an executor R gene. The NLR perceives non-RVD residues of the repeat array and in turn executes an immune reaction (depicted by a pistol) that typically culminates in cell death. The TALE can also be perceived by a DNA-based receptor (EBE) of an executor R gene. Interaction of tandem-arranged RVDs with the EBE results in transcription of the downstream executor R gene that upon translation triggers cell death. TALEs can rapidly change the composition of their repeat array by inserting or deleting repeats (e.g.: deletion of repeats 3 and 4). The evolved TALE is still recognized by the NLR but no longer by the executor R gene. Note the simplified depiction of the TALE protein where only the TALE repeat array is shown. Note, that suppression of NLR-mediated recognition of TALEs by iTALEs/truncTALEs is not shown here since these atypical TALEs have been observed only in Asian rice-infecting xanthomonads.

While the NLR proteins Bs4, Xa1, and Xo1 all perceive non-RVD TALE repeat residues, the tomato and rice NLR proteins differ substantially at the structural and functional level. Tomato Bs4 is a predicted cytoplasmatic protein while the highly similar rice Xa1 and Xo1, that are likely encoded by allelic genes [30], are nuclear-targeted NLRs [28,33]. Moreover, recognition of full-length TALEs by rice Xa1/Xo1 is suppressed by atypical TALEs lacking the C-terminal transcription activation domains, that are known as iTALEs (interfering TALEs) [32] or truncTALEs (truncated TALEs) [34]. iTALEs/truncTALEs have been observed only in rice-infecting xanthomonads and it is currently unclear how these atypical TALEs supress Xa1/Xo1-mediated recognition of full-length TALEs.

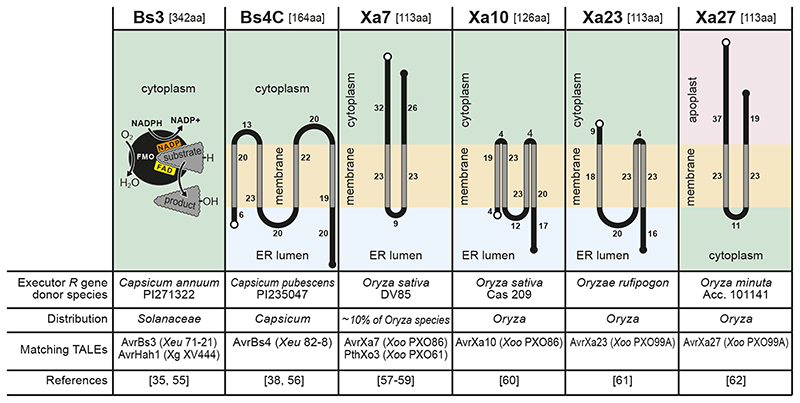

In TALE-perceiving executor R genes, an upstream EBE sequence motif serves as a DNA-based receptor that binds consecutive TALE RVDs and forces trapped TALEs to induce transcription of the downstream encoded executor gene. The translated executor R protein triggers cell death and stops proliferation of the strictly biotrophic pathogen Xanthomonas. Given that executor R proteins only execute cell death but are not involved in the perception of TALEs, this has been the defining characteristic for this peculiar R gene class. With the exception of rice Xa10 and Xa23 which are likely paralogues of one another, the six executor R proteins that are known to date share little to no sequence homology to each other, which is in marked contrast to the structural uniformity of NLR proteins [11]. However, aside from the pepper (Capsicum annuum) executor Bs3, which is the only executor with homology to a protein of known function, a flavin monooxygenase [35], executors share some commonalities including their small size (about 100 amino acids), predicted transmembrane domains, and localization in the endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 5), suggesting that executors might trigger cell death by similar means.

Figure 5. Structural and functional of executor R genes and encoded executor proteins.

Designation of executors is given on top with the size of the executor protein in square brackets. Depictions display the predicted topology and subcellular localization of executor proteins with terminal white and black circles indicating N- and C-termini, respectively. Transmembrane stretches were predicted with TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/) and are indicated with grey-coloured lines. Digits indicate the number of amino acids domains that a given domain is composed of.

All in all, TALE-sensing NLRs mediate recognition of conserved non-RVD repeat residues in TALE proteins, while TALE-sensing EBEs upstream of executor R genes mediate recognition of the highly evolvable RVDs of TALE-repeats. These functional features suggest that NLRs will provide more durable and substantially broader-spectrum resistance towards TALE- but not iTALE/truncTALE containing Xanthomonas strains, when compared to executor R genes.

How can the durability of native executor R genes be improved?

To overcome the problem of the predicted lack of durability in native executor R genes which are only equipped with single EBEs, scientists engineered executor R genes that are preceded by several tandem-arranged EBEs matching to a variety of TALEs present in corresponding Xanthomonas pathovars, providing broad-spectrum resistance [8–10]. The concept to equip a single executor coding sequence with numerous tandem-arranged EBEs seems reminiscent of the aforementioned CRISPR-based depletion of multiple EBEs to provide broad-spectrum resistance. However, there is a marked difference since Xanthomonas strains that contain several TALEs each being recognized by one of many tandem-arranged EBEs, the given strain must mutate several TALEs simultaneously to escape detection by such engineered executor alleles. This is in contrast to the aforementioned EBE-depleted pathogen-resistant plants, where a single eTALE is sufficient to regain host compatibility. In essence, promoter traps with tandem-arranged EBEs are likely superior in terms of durability as compared to EBE-depleted host plants. However, this approach relies on the presence of a transgene which still lacks acceptance in the public view.

TALE-trapping EBEs upstream of executors; evolved due to selection pressure?

As stated before, TALEs are highly evolvable and can escape detection by matching executor R genes via repeat rearrangements resulting in TALEs with modified DNA target specificity. This raises the following question: why would the plant immune system evolve TALE-specific immune receptors that rely on the most evolvable TALE domain? Circumstantial evidence suggests that executors with TALE-compatible EBEs did not evolve as TALE-specific immune receptors, but that their identification is simply a consequence of their specific in planta activity (see below). We postulate that the discovery of TALE-recognizing executor alleles is simply the result of extensive germplasm screens in which TALE-containing xanthomonads were used to uncover plant accessions that show TALE-dependent HRs. In such phenotypic screens TALEs effectively act as molecular probes that scan the genome of a given plant accession for the presence of TALE-compatible EBEs upstream of cell-death inducing open reading frames. Similar to an activation-tagging screen that uses random promoter integration resulting in the expression of nearby genes, the EBE mediates TALE-dependent ectopic expression of downstream plant genes, with the potential to induce cell death. Genetic diversity present across the studied germplasm is the fuel that boosts discovery of executor alleles preceded by a TALE-compatible EBE. Our considerations suggest that TALEs could be also used as probes to uncover phenotypes other than HR if these are induced by transcriptional activation of a given host gene. In summary, it seems plausible that executors are transcriptionally-controlled activators of cell death programs for which the biological relevance remains to be discovered. In this context, executor alleles that contain a TALE-compatible EBE in their 5’ upstream sequence have been generally interpreted by the scientific community as TALE-specific immune receptors that evolved due to evolutionary pressure to mediate resistance to TALE-containing xanthomonads. However, the presence of TALE-compatible EBEs in some executor alleles might occur simply by chance followed by human selection, an alternative hypothesis which is generally neglected. Given that there is no direct evidence that executor R alleles with TALE-compatible EBEs evolved due to evolutionary pressure, we should consider alternative models that explain the presence of TALE-activated executor alleles in the host germplasm.

What if TALE-perceiving executor alleles did not evolve due to evolutionary pressure?

If plant executor R genes would have evolved primarily to mediate protection against Xanthomonas infections, executor R genes should be present in plant species adapted to warm and humid environments since these conditions favour in planta growth of Xanthomonas [36]. Indeed TALE-sensing executor R genes have been isolated from pepper (Capsicum spp.) and rice, two plant species that are generally adapted to warm and humid climate conditions, supporting the idea that executors evolved to provide resistance against Xanthomonas. Upon careful inspection, at least two published cases reveal executor R genes that have been identified in plants in the absence of obvious evolutionary pressure.

For example, the executor R gene Bs4C that contains an EBE compatible to the X. euvesicatoria TALE protein AvrBs4 was identified in C. pubescens accession PI 235047 [37,38]. C. pubescens is the most cold-tolerant of the cultivated peppers that is grown in highland climates and does not tolerate the heat of lowland tropics [39]. This ultimately suggests that Bs4C resistance is not an evolutionary relevant trait in natural habitats of C. pubescens. Bs4C alleles are also present in C. annuum [38], the most extensively cultivated of the five domesticated Capsicum species that is grown throughout the world in warm temperate to tropical climates [40]. Interestingly, Bs4C alleles that are preceded by an AvrBs4-trapping EBE have not been identified in C. annuum genotypes, although evolutionary constraints should have favoured occurrence of such EBE-armed Bs4C alleles. It should also be noted that Bs4C-like genes are not restricted to Capsicum species but are present across all members of the nightshade family (Solanacea) including numerous plant species that are not Xanthomonas host plants [38], further supporting the notion that the native function of Bs4C might not reside in Xanthomonas resistance. In summary, the presence of EBE-armed Bs4C alleles in plants of the nightshade family does not correlate with presence of TALE-equipped xanthomonads in given habitats, suggesting that EBEs in identified executor R genes did not evolve due to pathogen pressure.

A second line of evidence in support of our hypothesis that executors did not evolve as TALE-specific immune sensors arises from studies of PthA4AT, a recently identified 7.5 repeat TALE protein that presumably evolved from PthA4, a 17.5 repeat TALE from X. citri that activates CsLOB1 [41]. PthA4AT, but not its NLS-mutant derivatives, triggers HR in lemon (Citrus limon) and Nicotiana benthamiana. This observation suggests that both N. benthamiana and lemon contain executor genes that trigger HR upon transcriptional activation of PthA4AT. Notably, the commonly used N. benthamiana laboratory (LAB) genotype is endemic to arid regions in Australia [42] which are unfavourable conditions to Xanthomonas that requires high humidity to proliferate in planta [36,43,44]. It therefore seems unlikely that the PthA4AT-induced N. benthamiana executor gene is a product of evolutionary constraints. One might also wonder why PthA4AT would uncover executors in both lemon and N. benthamiana. In this context it is worth noting that the 7.5 repeat TALE protein PthA4AT is predicted to target a sequence of merely 9 base pairs, which will occur by chance >1000 times in both the lemon and N. benthamiana genomes. Considering these numbers it seems less of a surprise that within the PthA4AT-activated plant genes at least one triggers a cell death reaction when being expressed ectopically.

In summation, the presence of EBE-armed executor genes in plants that are unlikely infected by Xanthomonas in their native habitats suggests that these executors did not evolve as TALE-sensing immune receptors, but that TALE-trapping EBEs occur by chance and were subsequently selected by breeders as monogenically-inherited plant R genes.

What is the native function of executor genes?

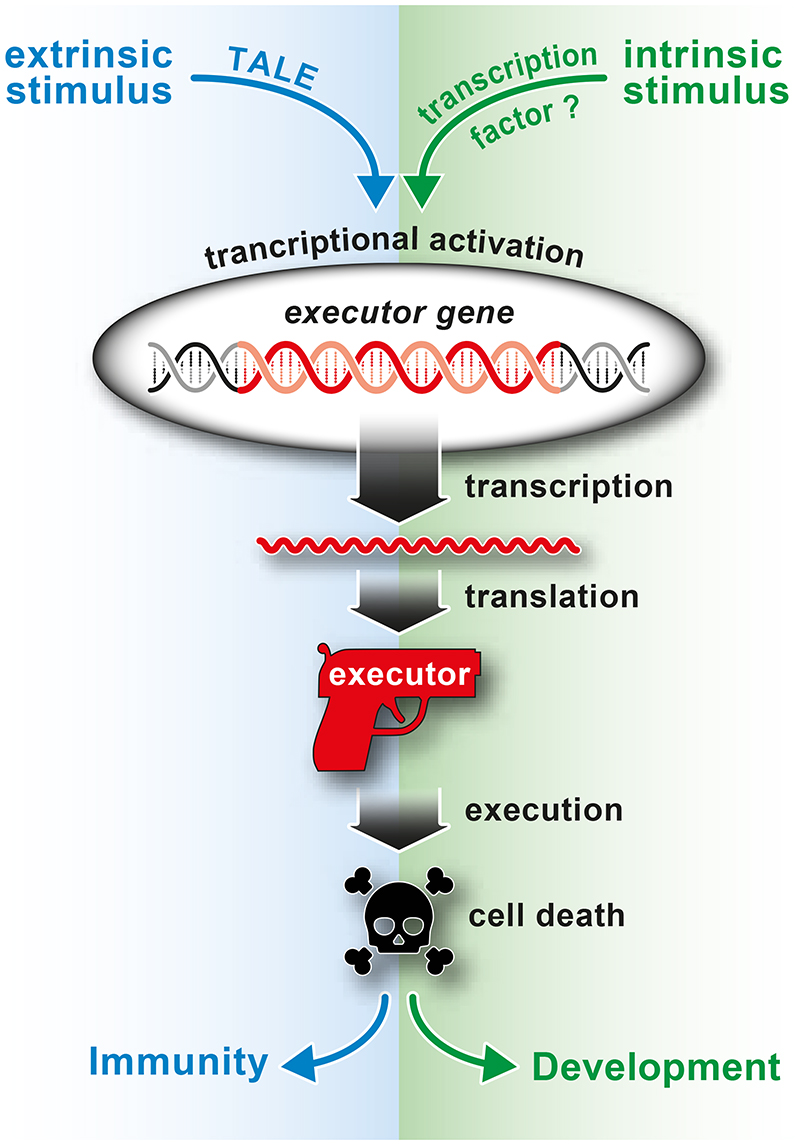

If executors did not evolve as TALE-trapping immune sensors, then what is their native function? In this context it is worth highlighting that distinct executor alleles present in accessions of a given plant species generally encode full length executor proteins, irrespective if they are equipped with TALE-trapping EBEs [45–47]. Maintaining cell-death inducing genes poses a risk to plant health since leaky expression would be detrimental. Indeed, executor transcripts have so far only been identified in plant tissue containing TALEs that transcriptionally activate the given executors. This tight expressional control resembles known features of developmental PCD (dPCD) programs that are generally confined to a few select cells within a specific organ at a defined developmental stage [48]. It is conceivable that executor genes could therefore possibly be transcriptionally-regulated activators of dPCD repurposed to provide resistance to the biotrophic pathogen Xanthomonas if the given executor coding sequence contains a TALE-compatible upstream EBE coincidentally (Figure 6, Key Figure).

Figure 6. Transcriptional activation of executor genes.

Proposed working model where executor genes are transcriptionally activated either by TALEs, resulting in plant immunity, or by the to-be-identified plant transcription factors that transcriptionally activate executors upon intrinsic stimuli. Expression of executors triggered by an intrinsic stimulus is likely restricted to a specific tissue or developmental stage and is likely involved in formation of specific cells, tissues, or plant organs.

Transcriptomic profiling of different cell death types revealed that transcriptional signatures of dPCD are distinct from the ones associated with pathogen-induced HR or cell death elicited by abiotic stresses [49]. If executor-triggered cell death would indeed be related to dPCD rather than an immunity-linked HR, executor- and NLR-triggered cell death reactions should be characterized by largely distinct transcriptional changes. Indeed, transcriptomic profiling of cell death executed by the TALE-sensing rice NLR Xo1 and the rice executor Xa23 revealed that the Xo1-mediated response is more similar to two other NLR type resistance proteins than it is to the response induced by the executor Xa23 [28]. While detailed transcriptomic studies of executors are still missing, the currently available data would be in line with the hypothesis that executor R genes are indeed part of dPCD programmes.

While we propose here a generalised model for executors in dPCD, it is possible that our model might only be applicable for some, but not all executors. Moreover, it is possible that executors trigger cell death only if expression is driven by TALEs, but not if expression is driven by plant transcription factors. In this context, it is worth noting that native- and TALE-induced transcripts of the same plant host gene typically differ in the length of their 5’ UTRs. 5’ UTRs often contain cis elements regulating translation of the downstream coding sequence. This could explain why native- and TALE-induced mRNAs can be derived from the same host gene, but have distinct transcriptional start sites, and can differ in their translational activity [50].

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Whether or not executor R genes are transcriptionally-controlled regulators of dPCD remains an outstanding question that should be studied experimentally in the future. To this end, executor knock out mutants could uncover informative phenotypes that might provide insight on their native function as well as spatial and temporal executor expression. Promoter-reporter fusions would provide a complementary experimental approach to uncover sites of native expression of executors.

Another outstanding question in the context of executor research is why the involvement of executors in dPCD processes has not been noted thus far. The few known executor genes from pepper and rice encode rather small proteins (Figure 5) that had not been annotated before TALE-dependent expression uncovered their function as cell death inducers. If indeed most executor genes are not yet annotated in plant genomes, then corresponding reads would be discarded as unmapped reads in RNA-Seq approaches even if executor reads are present in the raw data. Similarly, the lack of annotation possibly also prevented identification of executors in genetic forward screens where typically only mutations in annotated genes are considered as potentially causal mutations. Therefore, future studies of plant dPCD should consider that even in well-established model species like Arabidopsis thaliana, executor genes might have escaped annotation.

We consider it likely that executors are present in all plant species including the model plant arabidopsis. As explained above, TALEs with a small number of repeats (short TALEs; sTALEs) have the potential to transcriptionally activate numerous genes in parallel and could be used as an executor gene discovery tool in arabidopsis and other plant species. Due to sequence diversity across arabidopsis ecotypes, some sTALEs could trigger HR in an ecotype-specific fashion. Such differential, ecotype-specific phenotypes would provide the prerequisites for positional cloning of yet unknown executor genes. Given that dPCD has been studied most intensively in arabidopsis, it seems likely that newly identified executor genes can be integrated into known dPCD pathways. Newly identified arabidopsis executor genes could provide a tool to compare executor- and the numerous known NLR-induced cell death reactions and to clarify whether or not these proteins use the same or distinct genetic elements to execute cell death. Due to their tightly controlled expression, executor promoter-reporter fusions would be a valuable addition to the existing tools that visualize activation of dPCD at a cellular resolution. Moreover, it will be interesting to identify and study the upstream regulators that activate executors outside an immunity context. All in all, we postulate that the discovery and analysis of executor genes will provide a valuable tool to gain insight into the regulatory mechanisms of cell death control.

Glossary.

- Designer TALE (dTALE)

In vitro assembled TALE that binds to user-defined DNA target sequence. dTALE repeat arrays typically contain only RVDs with high base specificity to avoid off-targets.

- Effectors

pathogen-derived proteins that increase pathogen virulence. Bacterial effectors are injected into host cells via a syringe-like injection device, the bacterial type III secretion system.

- Effector binding element (EBE)

DNA sequence element to which a TALE binds. The presence of an EBE in the 5’ upstream sequence of a gene makes this gene TALE-inducible. The transcriptional start site (TSS) of a TALE-induced transcript is dictated by the EBE, typically 50-100 basepairs downstream of the EBE and often differs from the TSS of the native mRNA.

- Evolved TALE (eTALE)

TALE that evolved new DNA target specificity due to selection pressure.

- Executor

transcriptionally-controlled, cell death-inducing protein. Executor transcripts have been detected only upon transcriptional activation by matching TALEs, suggesting stringent transcriptional control. Executor proteins are structurally diverse, but often encode transmembrane proteins.

- Executor-type R genes

consist of two functional elements, a TALE binding site (EBE) and a downstream encoded executor protein, which induces cell death when being expressed. Note that only executor R genes combine the capability to recognize an effector and to trigger defence, while the translated executor has no recognition function at the protein level.

- Nucleotide binding leucine rich repeat proteins (NLRs)

NLRs are the predominant structural class of intracellular plant immune receptors and combine pathogen recognition and immune signalling activities at the protein level.

- Programmed cell death (PCD)

cellular suicide as a result of events inside of a cell; a process that is usually beneficial to the organism as a whole.

- Resistance (R) gene

mediates resistance against a microbial pathogen if present in an otherwise susceptible plant genotype. The vast majority of plant R genes encode nucleotide binding leucine rich repeat (NLR) proteins.

- Susceptibility (S) gene

encode host proteins that promote microbial disease. TALEs increase host susceptibility by transcriptional activation of host S genes. S alleles that are not TALE inducible can provide resistance to TALE-containing xanthomonads and coins these S alleles as recessively-inherited resistance (r) genes.

- Transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs)

effector class present in strains of the bacterial genus Xanthomonas with a structurally unique DNA binding domain, comprised of tandemarranged, almost identical 33-35 amino acid modules, a structural feature that promotes evolvability of DNA target specificity in TALEs. TALE-like proteins with tandem arranged DNA binding repeats have been found in the bacterial root pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum [51], the endofungal bacterium Mycetohabitans rhizoxinica [52,53] and unknown microbial marine organisms [54].

Acknowledgements

We thank Tom Schreiber, Sebastian Schornack, and Erin Ritchie for helpful comments. Work on executor genes in the AG Lahaye is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) in the context of SFB 1101 (project D08 to T. Lahaye). Research in the Nowack laboratory was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) consolidator grant EXECUT.ER 864952 and Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) project grant G002120N for M.K.N.

References

- 1.de Lange O, et al. From dead leaf, to new life: TAL effectors as tools for synthetic biology. Plant J. 2014;78:753–771. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pérez-Quintero AL, Szurek B. A decade decoded: spies and hackers in the history of TAL effectors research. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2019;57:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-100026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker S, Boch J. TALE and TALEN genome editing technologies. Gene and Genome Editing. 2021;2:100007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teper D, Wang N. Consequences of adaptation of TAL effectors on host susceptibility to Xanthomonas. PLoS Genet. 2021;17:e1009310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teper D, et al. PthAW1, a transcription activator-like effector of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri promotes host specific immune responses. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2021 doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-21-0026-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eom J-S, et al. Diagnostic kit for rice blight resistance. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1372–1379. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0268-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliva R, et al. Broad-spectrum resistance to bacterial blight in rice using genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1344–1350. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0267-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Römer P, et al. A single plant resistance gene promoter engineered to recognize multiple TAL effectors from disparate pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20526–20531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908812106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shantharaj D, et al. An engineered promoter driving expression of a microbial avirulence gene confers recognition of TAL effectors and reduces growth of diverse Xanthomonas strains in citrus. Mol Plant Pathol. 2017;18:976–989. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hummel AW, et al. Addition of transcription activator-like effector binding sites to a pathogen strain-specific rice bacterial blight resistance gene makes it effective against additional strains and against bacterial leaf streak. New Phytol. 2012;195:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, et al. TAL effectors and the executor R genes. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:641. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morbitzer R, et al. Regulation of selected genome loci using de novo engineered transcription activator-like effector (TALE)-type transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21617–21622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013133107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, et al. Complete decoding of TAL effectors for DNA recognition. Cell Res. 2014;24:628–631. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller JC, et al. Improved specificity of TALE-based genome editing using an expanded RVD repertoire. Nat Methods. 2015;12:465–471. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boch J, et al. TAL effectors - pathogen strategies and plant resistance engineering. New Phytol. 2014;204:823–832. doi: 10.1111/nph.13015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang B, et al. Os8N3 is a host disease-susceptibility gene for bacterial blight of rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604088103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Streubel J, et al. Five phylogenetically close rice SWEET genes confer TAL effector-mediated susceptibility to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. New Phytol. 2013;200:808–819. doi: 10.1111/nph.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox KL, et al. TAL effector driven induction of a SWEET gene confers susceptibility to bacterial blight of cotton. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15588. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohn M, et al. Xanthomonas axonopodis virulence promoted by TAL effector mediated induction of a SWEET sugar transporter in cassava. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014;27:1186–1198. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-14-0161-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezrutczyk M, et al. Sugar flux and signaling in plant-microbe interactions. Plant J. 2018;93:675–685. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutin M, et al. A knowledge-based molecular screen uncovers a broad spectrum OsSWEET14 resistance allele to bacterial blight from wild rice. Plant J. 2015;84:694–703. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, et al. Gene targeting by the TAL effector PthXo2 reveals cryptic resistance gene for bacterial blight of rice. Plant J. 2015;82:632–643. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timilsina S, et al. Xanthomonas diversity, virulence and plant-pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:415–427. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Z, et al. Engineering broad-spectrum bacterial blight resistance by simultaneously disrupting variable TALE-binding elements of multiple susceptibility genes in rice. Mol Plant. 2019;12:1434–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovett ST. Encoded errors: mutations and rearrangements mediated by misalignment at repetitive DNA sequences. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1243–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schornack S, et al. The tomato resistance protein Bs4 is a predicted non-nuclear TIR-NB-LRR protein that mediates defense responses to severely truncated derivatives of AvrBs4 and overexpressed AvrBs3. Plant J. 2004;37:46–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Triplett LR, et al. A resistance locus in the American heirloom rice variety Carolina Gold Select is triggered by TAL effectors with diverse predicted targets and is effective against African strains of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. Plant J. 2016;87:472–483. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Read AC, et al. Cloning of the rice Xo1 resistance gene and interaction of the Xo1 Protein with the defense-suppressing Xanthomonas effector Tal2h. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020;33:1189–1195. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-20-0131-SC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Read AC, et al. Genome assembly and characterization of a complex zfBED-NLR gene-containing disease resistance locus in Carolina Gold Select rice with Nanopore sequencing. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1008571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji C, et al. Xa1 allelic R genes activate rice blight resistance suppressed by interfering TAL effectors. Plant Commun. 2020;1:100087. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2020.100087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshimura S, et al. Expression of Xa1 a bacterial blight-resistance gene in rice, is induced by bacterial inoculation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1663–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji Z, et al. Interfering TAL effectors of Xanthomonas oryzae neutralize R-gene-mediated plant disease resistance. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13435. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu XM, et al. TALE-triggered and iTALE-suppressed Xa1-mediated resistance to bacterial blight is independent of rice transcription factor subunits OsTFIIAγ1 or OsTFIIAγ5. J Exp Botany. 2021;72:3249–3262. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Read AC, et al. Suppression of Xo1-mediated disease resistance in rice by a truncated, non-DNA-Binding TAL effector of Xanthomonas oryzae. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1516. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Römer P, et al. Plant-pathogen recognition mediated by promoter activation of the pepper Bs3 resistance gene. Science. 2007;318:645–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1144958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones JB, et al. Bacterial spot - worldwide distribution, importance and review. Acta Horticulturae. 2005:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahin F, Miller SA. Resistance in Capsicum pubescens to Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria pepper race 6. Plant Dis. 1998;82:794–799. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.7.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strauß T, et al. RNA-seq pinpoints a Xanthomonas TAL-effector activated resistance gene in a large crop genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:19480–19485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212415109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Swart EAM, et al. Variation in relative growth rate and growth traits in wild and cultivated Capsicum accessions grown under different temperatures. J Horticult Sci Biotechnol. 2006;81:1029–1037. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Bosland PW. The genes of Capsicum. Hortscience. 2006;41:1169–1187. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roeschlin RA, et al. PthA4(AT), a 7.5-repeats transcription activator-like (TAL) effector from Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri triggers citrus canker resistance. Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;20:1394–1407. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bally J, et al. The rise and rise of Nicotiana benthamiana a plant for all reasons. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2018;56:405–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.An SQ, et al. Mechanistic insights into host adaptation, virulence and epidemiology of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2020;44:1–32. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuz024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martins PMM, et al. Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri host interaction and control strategies. Trop Plant Pathol. 2020;45:213–236. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Römer P, et al. Recognition of AvrBs3-like proteins is mediated by specific binding to promoters of matching pepper Bs3 alleles. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1697–1712. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.139931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bimolata W, et al. Analysis of nucleotide diversity among alleles of the major bacterial blight resistance gene Xa27 in cultivars of rice Oryza sativa and its wild relatives. Planta. 2013;238:239–305. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1891-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cui H, et al. Promoter variants of Xa23 alleles affect bacterial blight resistance and evolutionary pattern. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daneva A, et al. Functions and regulation of programmed cell death in plant development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2016;32:441–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-124915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olvera-Carrillo Y, et al. A conserved core of programmed cell death indicator genes discriminates developmentally and environmentally induced programmed cell death in plants. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:2684–2699. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu D, et al. A plant pathogen type III effector protein subverts translational regulation to boost host polyamine levels. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:638–649. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Lange O, et al. Breaking the DNA binding code of Ralstonia solanacearum TAL effectors provides new possibilities to generate plant resistance genes against bacterial wilt disease. New Phytol. 2013;199:773–786. doi: 10.1111/nph.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Lange O, et al. Programmable DNA-binding proteins from Burkholderia provide a fresh perspective on the TALE-like repeat domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7436–7449. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carter ME, et al. A TAL effector-like protein of an endofungal bacterium increases the stress tolerance and alters the transcriptome of the host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:17122–17129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003857117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Lange O, et al. DNA-binding proteins from marine bacteria expand the known sequence diversity of TALE-like repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:10065–10080. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schornack S, et al. Characterization of AvrHah1 a novel AvrBs3-like effector from Xanthomonas gardneri with virulence and avirulence activity. New Phytol. 2008;179:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J, et al. The pepper Bs4C proteins are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane and confer disease resistance to bacterial blight in transgenic rice. Mol Plant Pathol. 2018;19:2025–2035. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo D, et al. The Xa7 resistance gene guards the susceptibility gene SWEET14 of rice against exploitation by bacterial blight pathogen. Plant Commun. 2021;2:100164. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2021.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen X, et al. Xa7 a new executor R gene that confers durable and broad-spectrum resistance to bacterial blight disease in rice. Plant Commun. 2021;2:100143. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2021.100143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang C, et al. Xa7 a small orphan gene harboring promoter trap for AvrXa7, leads to the durable resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Rice. 2021;14:48. doi: 10.1186/s12284-021-00490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tian D, et al. The rice TAL effector-dependent resistance protein XA10 triggers cell death and calcium depletion in the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Cell. 2014;26:497–515. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.119255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang C, et al. XA23 is an executor R protein and confers broad-spectrum disease resistance in rice. Mol Plant. 2015;8:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gu K, et al. R gene expression induced by a type-III effector triggers disease resistance in rice. Nature. 2005;435:1122–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature03630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]