Abstract

Poorly-Differentiated NeuroEndocrine Carcinomas (PD-NECs) are rare cancers garnering interest as they become more commonly encountered in clinic. This is due to improved diagnostic methods and the increasingly observed phenomenon of ‘NE lineage plasticity’, whereby non-NeuroEndocrine (non-NE) epithelial cancers transition to aggressive NE phenotypes after targeted treatment. Effective treatment options for patients with PD-NEC is challenging for several reasons. This includes a lack of targetable, recurrent molecular drivers, a paucity of patient-relevant preclinical models to study biology and test novel therapeutics, and the absence of validated biomarkers to guide clinical management. Whilst advances have been made pertaining to molecular subtyping of Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC), a PD-NEC of lung origin, Extra-Pulmonary (EP)-PD-NECs remain understudied. This review will address emerging SCLC-like, same-organ non-NE cancer-like and tumour type-agnostic biological vulnerabilities of EP-PD-NECs, with the potential for therapeutic exploitation. The hypotheses surrounding the origin of these cancers and how ‘NE lineage plasticity’ can be leveraged for therapeutic purposes is discussed. SCLC is herein proposed as a paradigm for supporting progress towards precision medicine in EP-PD-NECs. The aim of this review is to provide a thorough portrait of the current knowledge of EP-PD-NEC biology, with a view to informing new avenues for research and future therapeutic opportunities in these cancers of unmet need.

Keywords: extra-pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma, small cell lung cancer, biomarkers, drug discovery

1. Introduction

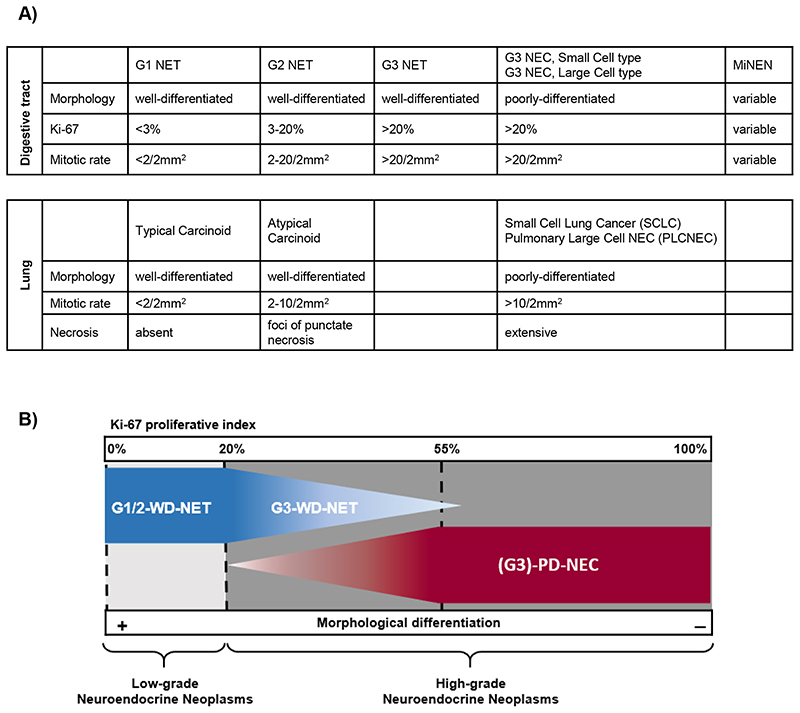

Neuroendocrine neoplasms are a heterogenous family of malignancies that can originate from different anatomical sites and share a neuroendocrine (NE) phenotype. This manifests histologically in a resemblance of the tumour cells to cells of the NE system, including presence of intra-cytoplasmatic neurosecretory granules and organoid-like cyto-architectural organisation plus expression of NE immunohistochemical (IHC) markers (synaptophysin and/or chromogranin A)(1,2). Neuroendocrine neoplasms are broadly divided into two main categories, based on their degree of morphological differentiation and replicative potential/biological aggressiveness; well differentiated neuroendocrine tumours (WD-NETs) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (PD-NECs) [Figure 1](3). PD-NECs represent the most aggressive subgroup; at a morphological level they are characterised by partial or complete loss of cyto-architectural organisation, a high proliferative rate (Ki-67 fraction ≥20%, often ≥55%), frequent mitoses and presence of necrosis. PD-NECs can present as a ‘small cell’ variant with diffuse sheets of cells having scant cytoplasm, a high nuclear/cytoplasmatic ratio and fusiform nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli and finely granular chromatin, or a ‘large cell’ variant with loosely defined organoid-like patterns of round/polygonal cells with moderate amounts of cytoplasm and large nuclei with prominent nucleoli and vesicular chromatin(1,2). While expression of synaptophysin and/or chromogranin A is required for a neuroendocrine neoplasm diagnosis in clinical practice, it is acknowledged that occasionally ‘small cell’-PD-NECs lack expression of both markers; in such cases, a ‘small cell’-PD-NEC diagnosis is made by exclusion and based on highly suggestive morphological features(4). Unlike WD-NETs, PD-NECs are rapidly growing and have a prognosis estimated in months rather than years(5). Both WD-NETs and PD-NECs can be found in co-existence with a variable proportion of a tumour histology lacking features of NE differentiation (non-NE). In the gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) tract, mixed NE/non-NE tumours with at least 30% of each component are classified separately from their pure counterparts and named mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs)(1). Progression from a WD-NET to a PD-NEC is an extremely rare observation in clinic. Most commonly PD-NECs originate de novo, or through NE trans-differentiation of pre-existing non-NE epithelial cancers under selective pressure within the tumour microenvironment such as that induced by targeted therapies(6,7); a phenomenon known as NE lineage plasticity, and which will be discussed in this review.

Figure 1. Classification of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms.

A) Table describing the current nomenclature according to the 2018 International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organisation (WHO) consensus framework(3), and the 2019 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System(1). Categories are based on morphological features for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of pulmonary origin, and a combination of morphological features and Ki-67 expression for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of extra-pulmonary origin. B) Simplified graphic representation of Table A.

NET = neuroendocrine tumour; this refers to a neuroendocrine neoplasm with a well-differentiated morphology (WD). NEC = neuroendocrine carcinoma; this refers to a neuroendocrine neoplasm with a poorly-differentiated morphology (PD). G1 (grade 1) and G2 (grade 2) identify low grades of proliferative activity and biological aggressiveness, and are defined by a Ki-67 index ≤20% for neuroendocrine neoplasm of extra-pulmonary origin. G3 (grade 3) identifies a high grade of proliferative activity and biological aggressiveness, and is defined by a Ki-67 index >20% for neuroendocrine neoplasms of extra-pulmonary origin. MiNEN = mixed neuroendocrine non neuroendocrine neoplasm; this definition applies to cancer from the gastro-entero-pancreatic tract composed of both neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine histology, each accounting for at least 30% of the tumour mass.

While the majority of PD-NECs (~90%) originate from the lung, namely small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (~86%) and large cell pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCPNEC) (~4%), a minority (~10%) arise from other anatomical sites and are generally termed extra-pulmonary (EP)-PD-NECs(5). Around a third (~37%) of EP-PD-NECs develop in the GEP tract, whereas approximately a quarter (~28%) remain of unknown origin (UNK)(5). In addition to GEP- and UNK-PD-NECs, this review will also address less common EP-PD-NEC subgroups per site of origin, each accounting for ≤10% of all EP-PD-NECs(5), namely prostate-, bladder-, uterine cervix-, and head and neck (H&N)-PD-NECs, in which some degree of molecular characterisation has been achieved. Merkel cell carcinoma has been excluded from this review, as this cutaneous NEC is etiologically related to clonal integration of a polyomavirus or chronic ultra-violet light exposure, and clinically managed as a separate entity from other EP-PD-NECs(8,9). Extra-pulmonary-PD-NECs are rare (age adjusted annual incidence of ~1/100,000 individuals according to the US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-18 registry 2000-2012 (5)), yet lethal diseases; patients predominantly have metastatic disease at diagnosis and a median life expectancy of less than 1 year(5,10). Their low incidence limits the ability to conduct clinical trials, dramatically narrowing the spectrum of therapeutic opportunities. Platinum/etoposide chemotherapy remains the only standard-of-care first-line treatment for patients with EP-PD-NEC not amenable to curative surgery(10,11). Although the majority of those patients show initial sensitivity to platinum/etoposide, tumour control is short-lived and overall survival benefit is limited. In addition, there is no consensus on second-line options(10,11).

Development of effective treatments for EP-PD-NECs has also been hampered by the paucity of knowledge of their biology and molecular drivers. Recent progress in the molecular subtyping of their NEC pulmonary counterpart SCLC may inform biological understanding and therapeutic development for EP-PD-NECs. Transcriptomic profiling of SCLC has revealed distinct molecular subtypes according to the expression of lineage-defining transcriptions factors; achaete-scute family bHLH transcription factor 1 (ASCL1), neuronal differentiation 1 (NEUROD1), atonal bHLH transcription factor 1 (ATOH1), POU class 2 homeobox 3 (POU2F3) and yes1 associated transcriptional regulator (YAP1)(12,13). These emerging transcription factor-based SCLC molecular subtypes are differentially enriched in NE and non-NE phenotypes and upregulation of MYC family oncogenes, and have unique biological vulnerabilities(12,14); they therefore represent a potential step forward in the direction of precision medicine.

Although EP-PD-NECs and SCLC share morphological and phenotypic similarities, there are differences in etiopathogenesis, clinical presentation and treatment outcomes, including weaker association with tobacco smoking, lower incidence of brain metastases and response rates to platinum-based chemotherapy in EP-PD-NECs(10), suggestive of some degree of biological divergence between these entities. Studies aimed at elucidating the genomic landscape of EP-PD-NECs, although mostly small, depict a complex scenario characterised by coexistence of pathognomonic alterations of SCLC (e.g. TP53 and RB1 loss), which are consistent across PD-NECs of different sites of origin (SCLC-like), and typical alterations of non-NE epithelial cancers from the same sites of origin (non-NE cancer-like)(6,15). This raises the question as to whether patients with EP-PD-NEC should be treated according to the phenotype (similar to SCLC) or site of origin of their cancer. In addition, there is wide inter-patient variability in treatment and survival outcomes within the EP-PD-NEC family(5,10), indicating underlying biological heterogeneity, and underscoring the critical need for biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment prediction. Other major challenges are the difficulty of accessing good quality tumour tissue for molecular analysis, and the paucity of patient-relevant preclinical models to assist biological studies and drug development.

This review will highlight emerging SCLC-like, same-organ non-NE cancer-like and tumour-type agnostic molecular vulnerabilities of EP-PD-NECs and will discuss opportunities for their therapeutic exploitation by leveraging knowledge of therapeutics in use, or under evaluation, in either SCLC or non-NE cancers from the same sites of origin.

2. SCLC-like vulnerabilities of EP-PD-NECs

2.1. Cell-cycle and DNA damage repair dysregulations

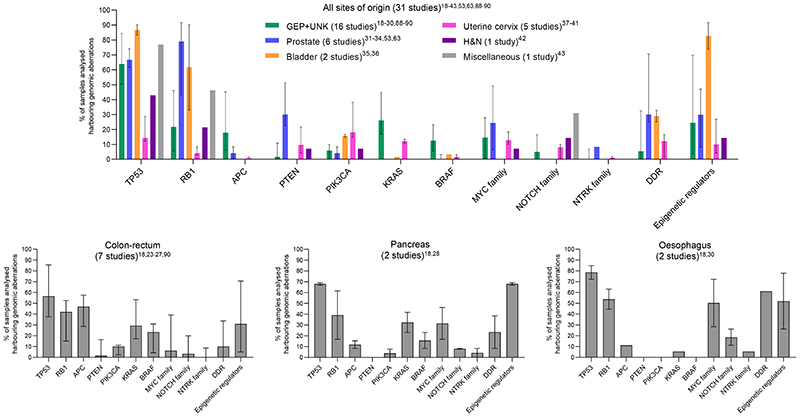

Genomic inactivation of TP53 and RB1 owing to either gene or chromosome aberration is nearly ubiquitous in SCLC (co-occurring at a frequency of ~98% in a large dataset of surgical human samples)(16), and is frequent in LCPNEC (TP53; 92%, RB1; 42%)(17). Genomic aberrations in TP53 and RB1 are also common in EP-PD-NECs(18-44)[Figure 2, Table 1], whereas they are rare in WD-NETs(19,20,22,23,44). Evidence from Trp53/Rb1 knockout mouse models of SCLC and prostate-PD-NEC indicates that combined Trp53/Rb1 loss acts synergistically as a potent driver of a lethal NE cancer phenotype; both de novo and in the background of a pre-existing non-NE epithelial cancer(6). Although disruption of TP53 and RB1 signalling is regarded as a hallmark of PD-NEC, genomic aberrations in these two tumour suppressors, in particular RB1, do not appear to be as prevalent in PD-NECs, other than in SCLC. A comprehensive multi-omic characterisation is still lacking for the majority of EP-PD-NECs and may unveil a higher prevalence of such aberrations, as shown in two recent whole exome/genome sequencing studies in GEP-PD-NECs(30,45). Other phenotypic-specific PD-NEC molecular drivers may also exist and are yet to be elucidated, and may be responsible for genotypic/phenotypic heterogeneity within the EP-PD-NEC family. For example, genomic and transcriptomic profiling of LCPNEC has unveiled two main molecular subgroups; one enriched in TP53 and RB1 co-inactivation (42%) and featuring low expression of NE-related genes, and the other enriched in TP53 and Serine/Threonine Kinase 11 (STK11)/Kelch Like ECH Associated Protein 1 (KEAP1) co-alteration (37%) and featuring high expression of NE-related genes. Alternatively, in TP53- and/or RB1-wild type EP-PD-NECs, TP53 and RB1 signalling can be suppressed by events other than aberrations at their genomic loci, such as amplification of MDM2 (a TP53 repressor)(32), mutation of TP73 (a TP53 paralog)(18,45), deletion or epigenetic silencing of CDKN2A (which encodes for the RB1 signalling effector p16)(26,45) and amplification of CCNE1 (an RB1 antagonist)(26,30,38,45). Finally, TP53 and/or RB1 protein function can be counteracted by viral onco-proteins, and when this suppression is chronic, it can lead to PD-NEC development, as shown in Merkel cell carcinoma, which most commonly is caused by a polyomavirus infection and lacks dual TP53/RB1 loss(8). For example, high-risk human papillomavirus has been reported in a subset of PD-NECs from the uterine cervix- (42.5-92.2%)(37,38,40) and colon-rectum (28.0%)(26), where it is thought to play a pathogenetic role through inhibitory interaction with RB1 protein.

Figure 2. Common genomic alterations in Extra-Pulmonary NeuroEndocrine Carcinomas.

Frequency (median and interquartile range) of samples harboring any genomic alteration (point mutation, copy number gain, copy number loss, amplification, deletion, chromosomal rearrangement) is reported for a selection all genomic studies in extra-pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas presented in this review. GEP = gastro-entero-pancreatic tract. UNK = unknown primary origin. H&N = head and neck. DDR = DNA damage repair. Remaining acronyms are defined in Table 4. Studies selected were those where samples included were from ≥10 patients.

Table 1. Detailed description of common genomic alterations in Extra-Pulmonary NeuroEndocrine Carcinomas.

| Ref. | n | Site of origin | Method | TP53 | RB1 | KRAS | BRAF | PTEN | PI3KCA | APC | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | |||||||||||

| Venzelos A, 2021(18) | 152 | GEP+UNK | NGS 360-gene panel + CNV | 63.8% | 0.0% | 10.5% | 3.3% | 30.3% | 22.4% | 0.0% | 19.7% | 0.0% | n/r | n/r | 4.6% | 0.0% | 28.3% | 0.0% | |||||||||||||

| Puccini A, 2020(19) | 135a | GEP | NGS 592/44-gene panel + CNV | 51.0% | n/r | 11.0% | n/r | 29.4% | n/r | 5.4% | n/r | n/a or n/r | n/a or n/r | n/a or n/r | n/a or n/r | 7.0% | n/r | 27.0% | n/r | ||||||||||||

| Sahnane N, 2015(88) | 89b | GEP | PCR-pyrosequencing | n/a | n/a | 17.0% | 6.8% | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Busico A, 2019(20) | 39 | GEP | NGS 50-gene panel | 59.0% | 2.6% | 10.3% | 7.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.1% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gerard L, 2020(21) | 24 | GEP+UNK | NGS 78-gene panel (ctDNA) | 87.5% | 8.3% | 16.7% | 12.5% | 4.2% | 4.2% | 8.3% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vijayvergia N, 2016(22) | 23 | GEP+othersf | NGS 50-gene panel | 56.5% | 4.3% | 26.1% | 13.0% | 13.0%. | 8.7% | 8.7% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dizdar L, 2018(89) | 18 | GEP | Sanger sequencing | n/a | n/a | n/a | 38.9% | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Olevian DC, 2016(90) | 32c | Colonrectum | qPCR | n/a | n/a | 17.2% | 58.6% | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Takizawa N, 2015(23) | 24d | Colonrectum | PCR amplification and direct sequencing | 20.8% | n/a | 8.3% | 4.2% | n/a | n/a | 4.2% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lee SM, 2021(24) | 30 | Colonrectum | NGS 382-gene panel + CNV | 43.3% | n/r | 20.0% | 26.7% | 53.3% | n/r | 23.3% | n/r | 3.3% | n/r | 10.0%. | n/r | 36.7% | n/r | ||||||||||||||

| Capdevila J, 2020(25) | 25 | Colon | NGS 61-gene panel | 84.0% | 0.0% | 48.0% | 28.0% | 0.0%. | 0.0% | 48.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Shamir ER, 2018(26) | 24 | Colon-rectum+anus | NGS 479-gene panel + CNV | 4.2% | 37.5% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 4.2% | 8.3% | 37.5% | 12.5% | 29.2% | 0.0% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 8.3% | 8.3% | 4.2% | 4.2% | 8.3% | 37.5% | 12.5% | 0.0% | ||||||||

| Woischke C, 2017(27) | 10-15e | Colonrectum | NGS 50-gene panel | 90.0% | 30.0% | 60.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 80.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Konukiewitz B, 2018(28) | 12 | Pancreas | NGS 409-gene panel + CNV | 66.7% | n/r | 0.0% | 8.3% | 8.3% | 41.7% | n/r | 8.3% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 8.3% | n/r | |||||||||||||

| Liu F, 2020(29) | 15 | Gallbladder | WES + CNV | 73.3% | 0.0% | 26.7% | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0%. | n/r | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0%. | ||||||||||||||

| Li R, 2021(30) | 46 | Oesophagus | WES + CNV | 84.8% | 0.0% | 34.8% | 28.2% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | ||||||||||||||

| Mosquera JM, 2013(63) | 49-75 | Prostateg | FISH | 28.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beltran H, 2011(53) | 37 | Prostate | FISH | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beltran H, 2016(31) | 30 | Prostateg | WES + CNV | 30.0% | 10.0% | 26.7% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 66.7% | n/r | n/r | 3.3% | n/r | n/r | 30.0% | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | ||||||||||||

| Chedgy ECP, 2018(32) | 17 | Prostateh | NGS 73-gene panel/ WES + CNV | 29.4% | 47.1% | 0.0% | 5.9% | 17.6% | 70.6% | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 11.8% | 41.2% | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | ||||||||||||

| Tan H-L, 2014(33) | 9-13 | Prostatei | NGS 50-gene panel/Sanger sequencing + CNV (NanoString) | 60.0% | n/a | 0.0% | 84.6% | n/r | n/a or n/r | n/r | n/a or n/r | 11.1% | 38.5% | n/r | n/a or n/r | n/r | n/a or n/r | ||||||||||||||

| Aggarwal R, 2018(34) | 12 | Prostateg | NGS 91-gene panel + CNV | 58.3% | 8.3% | 16.7% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 8.3% | 8.3% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 8.3% | 0.0% | ||||||||||||||

| Chang MT, 2018(35) | 61 | Bladder | NGS 281/341-gene panel/WES/WGS | 29.5% | 59.0% | 1.6% | 23.0% | 57.4 | 9.8% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 3.3% | 0.0% | n/r | n/r | 14.8% | 0.0% | n/r | n/r | ||||||||||||

| Shen P, 2018(36) | 12 | Bladder+prostate | WGS/WES | 83.3% | 33.3% | n/r | n/r | n/r | 16.7% | n/r | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cimic A, 2020(37) | 62 | Uterine cervix | NGS 592-gene panel + CNV | 17.7% | 0.0% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 11.3% | 0.0% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 17.7% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 0.0% | ||||||||||||||

| Pei X, 2021(38) | 49 | Uterine cervix | NGS 520-gene panel + CNV | 12.2% | 0.0% | 2.0% | 4.1% | 0.0% | 10.2% | 2.0% | ≤2.0%j | 0.0% | 6.1% | 0.0% | 8.2% | 2.0% | 2.0% | ≤2.0% | 0.0% | ||||||||||||

| Frumovitz M, 2016(39) | 44 | Uterine cervix | NGS 50-gene panel | 11.4% | 2.3% | 13.6% | 0.0% | 2.3% | 18.2% | 0.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hillman RT, 2020(40) | 15 | Uterine cervx | WES + CNV | 13.3% | n/r | 6.7% | n/r | 13.3% | n/r | ≤6.7%J | n/r | ≤6.7%J | 33.3% | 26.7% | 13.3% | 6.7% | ≤6.7%J | n/r | |||||||||||||

| Xing D, 2018(41) | 10 | Uterine cervix | NGS 637-gene panel | 40.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% or n/a | 10.0%. | 30.0% | 0.0% or n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ohmoto A, 2021(42) | 14 | Head and neck | NGS 523-gene panel | 42.9% | 21.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.1% | 7.1% | 0.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Meder L, 2019(43) | 26 | Differentsitesk | NGS panel (n genes not provided) | 76.9% | 46.2% | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ref. | n | Site of origin | Method | NOTCH family | MYC family | NTRK family | DDR family | Epigenetic regulators | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | Mutations | CNVs | Others | |||||||||||

| Venizelos A, 2021(18) | 152 | GEP+UNK | NGS 360-gene panel + CNV | 6.6% | 0.0% | 0.0 % | 1.3 % | 50.0% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 5.9 % | 3.9% | 27.0% | 11.8 % | 7.2% | 9.9% | 5.3% | 22.4% | 14.5% | 7.9% | |||||

| Puccini A, 2020(19) | 135a | GEP | NGS 592/44-gene panel + CNV | n/a or n/r | n/a or n/r | n/r | 3-4% | n/a or n/r | n/a or n/r | 0.0% | n/a or n/r | n/a or n/r | 23.0% | n/r | |||||||||||

| Sahnane N, 2015(88) | 89b | GEP | PCR-pyrosequencing | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||

| Busico A, 2019(20) | 39 | GEP | NGS 50-gene panel | 0.0% | n/a | n/a | 2.5% | 2.5% | |||||||||||||||||

| Gerard L, 2020(21) | 24 | GEP+UNK | NGS 78-gene panel (ctDNA) | n/a or 0.0% | n/a or 0.0% | n/a or 0.0% | n/a or 0.0% | n/a or 0.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| Vijayvergia N, 2016(22) | 23 | GEP+othersf | NGS 50-gene panel | 0.0% | n/a | n/a | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| Dizdar L, 2018(89) | 18 | GEP | Sanger sequencing | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||

| Olevian DC, 2016(90) | 32c | Colon-rectum | qPCR | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||

| Takizawa N, 2015(23) | 24d | Colon-rectum | PCR amplification and direct sequencing | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||

| Lee SM, 2021(24) | 30 | Colon-rectum | NGS 382-gene panel + CNV | 3.3% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | ||||||||||||

| Capdevila J, 2020(25) | 25 | Colon | NGS 61-gene panel | 0.0% | 0.0% | n/a | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| Shamir ER, 2018(26) | 24 | Colon-rectum+anus | NGS 479-gene panel + CNV | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 41.7% | 0.0% | ||||||||||||

| Woischke C, 2017(27) | 10-15e | Colon-rectum | NGS 50-gene panel | 30.0% | n/a | n/a | 20.0% | 0.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| Konukiewitz B, 2018(28) | 12 | Pancreas | NGS 409-gene panel + CNV | 8.3% | n/r | 0.0% | 16.7% | 8.3% | n/r | 8.3% | n/r | 66.7% | n/r | ||||||||||||

| Liu F, 2020(29) | 15 | Gallbladder | WES + CNV | 13.3% | 0.0% | 13.3% | 6.6% | n/r | 0.0% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 73.3% | 0.0% | ||||||||||||

| Li R, 2021(30) | 46 | Oesophagus | WES + CNV | 26.1% | 0.0% | n/r | 28.3% | n/r | 0.0% | n/r | 0.0% | 26.0% | 0.0% | ||||||||||||

| Mosquera JM, 2013(63) | 49-75 | Prostateg | FISH | 52.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Beltran H, 2011(53) | 37 | Prostate | FISH | 40.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Beltran H, 2016(31) | 30 | Prostateg | WES + CNV | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 3.3% | 26.7% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 23.3% | |||||||||||

| Chedgy ECP, 2018(32) | 17 | Prostateh | NGS 73-gene panel/ WES + CNV | n/a | n/a | 5.9% | n/r | n/a | n/a | 17.6% | 35.3% | 17.6% | 35.3% | 11.8% | |||||||||||

| Tan H-L, 2014(33) | 9-13 | Prostatei | NGS 50-gene panel/Sanger sequencing + CNV (NanoString) | n/r | n/a or n/r | n/a | n/a or n/r | n/a | n/a or n/r | n/r | n/a or n/r | n/r | n/a or n/r | ||||||||||||

| Aggarwal R, 2018(34) | 12 | Prostateg | NGS 91-gene panel + CNV | n/a | n/a | 0.0% | 8.3% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 16.7 % | 8.3% | 0.0% | 8.3% | 0.0% | |||||||||||

| Chang MT, 2018(35) | 61 | Bladder | NGS 281/341-gene panel/WES/WGS | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 32.8% | 73.8% (not sure if all point mutations) | ||||||||||||||

| Shen P, 2018(36) | 12 | Bladder+ prostate | WGS/WES | n/r | n/r | n/r | 25.0% | 83.3% | 8.3% | ||||||||||||||||

| Cimic A, 2020(37) | 62 | Uterine cervix | NGS 592-gene panel + CNV | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.2% (not sure if in different patients) | 0.0% | 6.4% (not sure if in different patients) | 0.0% | |||||||||||

| Pei X, 2021(38) | 49 | Uterine cervix | NGS 520-gene panel + CNV | ≤2.0%j | 6.1% | 2.0% | ≤2.0%j | 18.4% | ≤2.0%j | 2.0% | 12.2% | n/r | 20.4% | n/r | |||||||||||

| Frumovitz M, 2016(39) | 44 | Uterine cervix | NGS 50-gene panel | 0.0% | n/a | n/a | 0.0% | 2.3% | |||||||||||||||||

| Hillman RT, 2020(40) | 15 | Uterine cervix | WES + CNV | ≤6.7%J | n/r | ≤6.7%J | n/r | ≤6.7%J | n/r | 13.3% | n/r | 33.3% | n/r | ||||||||||||

| Xing D, 2018(41) | 10 | Uterine cervix | NGS 637-gene panel | 10.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% or n/a | 20.0% | 10.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| Ohmoto A, 2021(42) | 14 | Head and neck | NGS 523-gene panel | 14.3% | 0.0% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 14.3% | ||||||||||||||||

| Meder L, 2019(43) | 26 | Different sitesk | NGS panel (n genes not provided) | 30.8% | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||||

□ Point mutation

□ Copy number loss

□ Deletion

□ Co-occurring point mutation + deletion in the same sample

□ Chromosomal rearrangement

□ Co-occurring deletion + amplification in the same sample (different genes)

□ Co-occurring point mutation + copy number loss in the same sample

□ Copy number gain

□ Amplification

□ Co-occurring point mutation + amplification in the same sample

□ Co-occurring point mutation + chromosomal rearrangement in the same sample

□ Co-occurring deletion + amplification + point mutation in the same sample (different genes)

n = number of samples analysed (if a range is provided, n varied across genes analysed based on tissue availability). GEP = gastro-entero-pancreatic tract. NGS = next generation sequencing. WES = whole exome sequencing. WGS = whole genome sequencing. CNV = copy number variation analysis. FISH = fluorescent in situ hybridisation. PCR = polymerase chain reaction. n/r = gene analysed but alteration frequency not reported in the publication (usually because the alteration is absent or extremely rare). n/a = gene not assessed. a = this includes both poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (PD-NECs) and G3 well differentiated neuroendocrine tumours, however, relative proportions of the two subgroups are not provided. b = 53 pure PD-NECs + 36 mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs). c =14 pure PD-NECs + 18 MINENs. d = Includes 3 or 4 MiNENs. e = 5 pure PD-NECs + 10 MiNENs. f = 14 PD-NECs from the GEP tract and 9 from an unspecified extra-GEP origin. g = treatment-induced prostate-PD-NECs (originating from previous prostate adenocarcinomas). h = all ‘de novo’ prostate-PD-NECs. i = both treatment-induced and ‘de novo’ prostate-PD-NECs. J = mutations reported in this study were only those occurring in ≥2 samples. k = 7 head & neck/3 GEP/3 uterine cervix/8 urinary tract/5 prostate. Studies selected were those where samples included were from ≥10 patients.

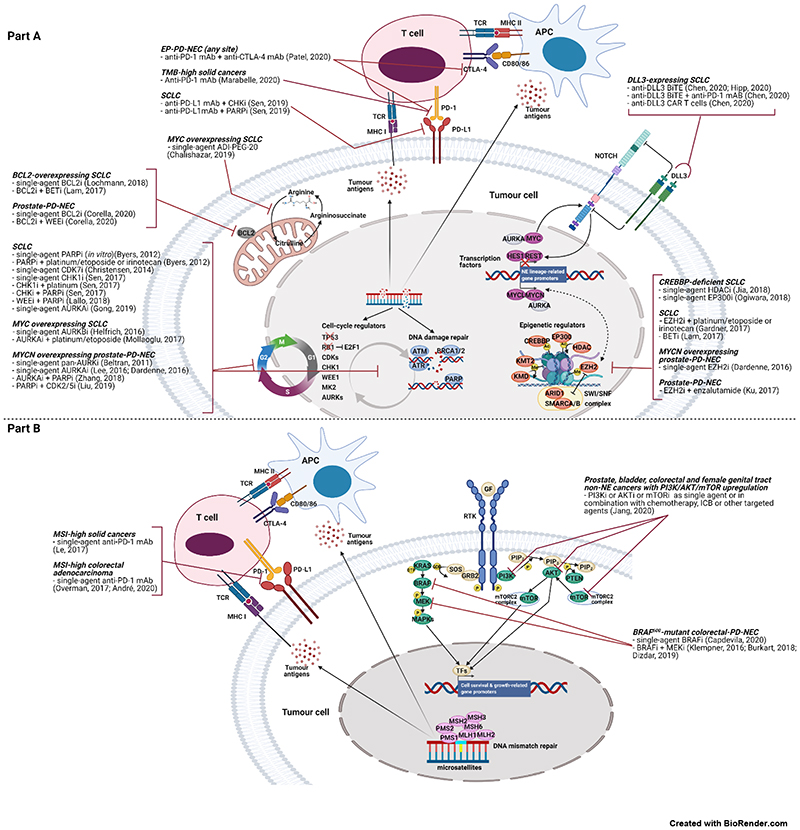

Cancer cells defective in TP53 and/or RB1 function have a reduced ability to undergo cell cycle arrest and enable DNA damage repair (DDR), if present. This makes those cells critically reliant on other cell-cycle checkpoints, (e.g. cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), WEE1, Aurora kinases (AURKs)) and components of the DDR pathway (e.g. CHK1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) proteins), especially in the context of DNA-damaging treatment, such as platinum-based chemotherapy or radiotherapy(46-49). Growing evidence points towards frequent dysregulation of the DDR pathway in both SCLC and EP-PD-NECs, providing further rationale for the therapeutic exploitation of the synthetic lethal relationship between cell-cycle deficiency and DDR in these cancers. Transcriptomic profiling of SCLC (cell lines) and prostate-PD-NEC (human samples and patient-derived xenografts) has unveiled significant enrichment in the expression of DDR proteins as compared to non-NE epithelial cancers from the same organs(46,50). In EP-PD-NECs, somatic alterations in DDR genes are present, albeit with varying prevalence partially owing to differences in the number and selection of DDR genes evaluated (2.5-70.6%)(18,20,27-29,31,32,34-38,40,41,44) [Figure 2, Table 1]. Germline mutations in DDR genes occur in 29% and 20% of patients with SCLC and EP-PD-NEC, respectively, and are predictive of increased sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy, laying the ground for the investigation of DDR inhibitors in combination with DNA-damaging agents in this patient subgroup(51). Inhibitors of CHK1, WEE1, CDKs, AURKs and PARP proteins, as monotherapy or in combination with other cell-cycle/DDR inhibitors or chemotherapy, have shown promising in vitro and in vivo activity in SCLC(46-49,52) and prostate-PD-NEC(50,53-55) [Figure 3, “i” suffix = inhibitor]. Cell-cycle/DDR-directed therapies are currently being evaluated in clinical trials in patients with SCLC(11) and EP-PD-NEC [Table 2]. For example, a combination of the inhibitors of two DDR effectors; the ATR Serine/Threonine Kinase (ATR) and DNA topoisomerase I (TOP1) demonstrated potent synergy in a drug screening study in SCLC cell lines and was selected for clinical investigation. A phase II clinical trial provided initial evidence of its activity in patients with SCLC (n=25) or EP-PD-NEC (n=10), previously treated with platinum/etoposide(56).

Figure 3.

Molecular vulnerabilities of Extra-Pulmonary NeuroEndocrine Carcinomas, associated therapeutic opportunities and supporting preclinical and clinical evidence. Part A presents SCLC-like and tumour-type agnostic molecular vulnerabilities. Part B presents same-organ non-NE cancer-like molecular vulnerabilities.

mAB = monoclonal antibody. CTLA-4=cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4. ICB=immune checkpoint blockade. TMB=tumour mutation burden. MHC I or II=major histocompatibility complex I or II. TCR=T cell receptor. APC=cell presenting antigen. ADI-PEG-20=pegylated arginine deiminase. BET=bromodomain and extra-terminal domain proteins. BiTE=bispecific T cell engager. CAR T cell=chimeric antigen receptor T cell. HDAC=histone deacetylase. KMT2=histone lysine methyltransferase 2 family. KMD=histone lysine demethylase family. MAPKs=mitogen activated protein kinases. RTK=receptor tyrosine kinase. GF=growth factor. MSI=microsatellite instability. The suffix “i” after the name of the protein means “inhibitor”. Remaining acronyms are defined in Table 4.

Table 2. Ongoing clinical trials including patients with Extra-Pulmonary NeuroEndocrine Carcinoma (https://clinicaltrials.gov/, July 2021, recruitment status: recruiting, active not recruiting or completed).

| Investigational compound(s) | Study design | Site of origin for EP-PD-NECs | Line of treatment | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Results (published or presented at international conferences) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| 5-FU/folinic acid/irinotecan/oxaliplatin vs. cisplatin or carboplatin + etoposide | Phase II randomised (parallel arms) | GEP or UNK | 1st | NCT04325425 | |

| Capecitabine + temozolomide vs. cisplatin or carboplatin + etoposide | Phase II randomised (parallel arms) | GEP or UNK | 1st | NCT02595424 | |

| Cisplatin + everolimus | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | 1st | NCT02695459 | |

| Temozolomide + everolimus | Phase II single arm | GEP or UNK (Ki-67<55%) | 1st | NCT02248012 | |

| Cisplatin + irinotecan ÷ octreotide (upon progression to cisplatin + irinotecan) | Phase II single arm | GEP | 1st | NCT01480986 | |

| Cisplatin or Carboplatin + etoposide (4-6 cycles) ÷ everolimus as maintenance therapy vs. observation only | Phase II randomised | GEP (Ki-67<55%) | 1st | NCT02687958 | |

| TAS-102 | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT04042714 | |

| 5-FU/folinic acid/nal-irinotecan or docetaxel | Phase II randomised (parallel arms) | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT03837977 | |

| TLC388 (lipotecan) | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT02457273 | |

| Capecitabine + temozolomide vs. 5-FU/folinic acid/irinotecan | Phase II randomised | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT03387592 | |

| 5-FU/folinic acid/irinotecan + bevacizumab vs. 5-FU/folinic acid/irinotecan | Phase II randomised | GEP or UNK | 2nd | NCT02820857 | |

| Temozolomide | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT04122911 | |

| 5-FU/folinic acid/nal-irinotecan | Phase II single arm | GEP or UNK | 2nd | NCT03736720 | |

| PEN-221 | Phase I/II single arm (multiple cohorts) | Any site of origin | After 1 st | NCT02936323 | |

| Nab-paclitaxel + bevacizumab | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | After 1 st | NCT04705519 | |

| Carboplatin + etoposide + paclitaxel ÷ paclitaxel | Phase II single arm | UNK | Not specified | NCT00193531 | |

| Capecitabine + temozolomide | Phase II single arm | GEP (Ki-67<60%) | Not specified | NCT03079440 | |

| Immune checkpoint blockade | |||||

| Avelumab | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | After 1 st | NCT03352934 | Preliminary results presented at ASCO 2019 by Fottner C et al. (median follow-up of 16.5 weeks, tot n=27 patients): 8 week-irDCR=32%; median OS=4.2 months. |

| Avelumab | Phase II single arm | GEP | 2nd | NCT03147404 | |

| Avelumab | Phase I/II | GEP | 1st or beyond | NCT03278405 | |

| Avelumab | Phase II single arm | Prostate | After 1 st | NCT03179410 | |

| Spartalizumab | Phase II single arm | GEP | After 1 st | NCT02955069 | |

| Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Phase II single arm, basket trial (multiple cohorts) | GEP, prostate, cervix, thymus, UNK | After 1st | NCT02834013 | Results published by Patel SP et al. (Clin Cancer Res 2020) for the G3-NEN cohort (n=18 patients, including a proportion with a lung origin): ORR=44%, 6-month-PFS rate= 44%. |

| Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Phase II single arm | Any genito-urinary site | Not specified | NCT03333616 | |

| Nivolumab or nivolumab + ipilimumab | Phase II randomised (parallel arms) | GEP | 2nd or 3rd | NCT03591731 | |

| Durvalumab + tremelimumab | Phase II single arm | GEP or UNK | 2nd | NCT03095274 | Preliminary results presented at ESMO 2020 by Capdevila J et al. In the G3-NEN cohort (median follow-up; 10.8 months): irORR=9.1%, 9-month-OS rate=36.1%. |

| Nivolumab + 177Lu-Dotatate | Phase II single arm | GEP or UNK | 1st or 2nd | NCT04525638 | |

| Nivolumab + temozolomide | Phase II single arm (2 cohorts) | Any site of origin | 1st or beyond | NCT03728361 | |

| Pembrolizumab alone or + irinotecan or paclitaxel | Two stage, phase II single arm | Any site of origin | After 1 st | NCT03136055 | |

| Toripalimab + simmtecan + 5-FU/folinic acid vs. cisplatin or carboplatin + etoposide | Phase II single arm (part I)/phase III (part II) | Any site of origin | 1st or beyond | NCT03992911 | |

| Pembrolizumab + SOC chemotherapy | Phase Ib (2 cohorts) | Prostate or urothelium/bladder | 1st or beyond | NCT03582475 | |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab + carboplatin + cabazitaxel | Phase II single arm | Prostate | 1st of beyond | NCT04709276 | |

| Camrelizumab + cisplatin or carboplatin etoposide + bevacizumab | Phase II single arm | Uterine cervix | Not specified | NCT04635956 | |

| Pembrolizumab + talabostat mesylate | Phase Ib/II single arm (2 cohorts) | Prostate | After 1 st | NCT03910660 | |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab + cabozantibib | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT04079712 | |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab + cabozantibib | Phase II single arm (multiple cohorts) | Bladder | 1st of beyond | NCT03866382 | |

| Nivolumab + cabozantinib or nivolumab + ipilimumab + cabozantinib | Phase I (2 stages) | Any genito-urinary site | Not specified | NCT02496208 | |

| Dostarlimab + niraparib | Phase II single arm (2 cohorts) | Any site of origin, except prostate | After 1 st | NCT04701307 | |

| Cabazitaxel + carboplatin + cetrelimab ÷ niraparib vs. cetrelimab + niraparib as maintenance | Phase II randomised | Prostate | 1st or 2nd (if no previous platinum) | NCT04592237 | |

| BiTE therapy | |||||

| AMG 757 | Phase Ib | Prostate | After 1 st | NCT04702737 | |

| BI 764532 | Phase I | Any site of origin (expressing DDL3) | After 1 st | NCT04429087 | |

| XmAb20717 | Phase I | Any site of origin | After 1 st | NCT03517488 | |

| Inhibitors of cell-cycle or DDR regulators | |||||

| BAY 1895344 (elimusertib) + nal-irinotecan or topotecan | Phase II single arm (2 cohorts) | Any site of origin | After 1 st | NCT04514497 | |

| Barzosertib + lurbinectedin | Phase I/II single arm | Any site of origin | After 1st (phase I), not specified (phase II) | NCT04802174 | |

| Barzosertib + topotecan vs. topotecan | Phase II randomised | Any site of origin (only small cell morphology) | 1st or beyond | NCT03896503 | |

| M6620 + topotecan | Phase I/II single arm | Any site of origin | After 1st (phase I), 1st or beyond (phase II) | NCT02487095 | |

| Rucaparib + PEG-SN38 | Phase I/II single arm | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT04209595 | |

| Inhibitors of epigenetic regulators | |||||

| Belinostat + cisplatin + etoposide | Phase I | Any site of origin | 2nd or 3rd | NCT00926640 | |

| Receptor tyrosine kinase signalling inhibitors | |||||

| Erdafitinib | Phase II single arm | Prostate | 1st or beyond | NCT04754425 | |

| Everolimus | Phase II single arm | Any site of origin | 2nd | NCT02113800 | |

| DS-3078a | Phase I | Any site of origin | After 1st | NCT01588678 | Preliminary results presented at AACR 2013 by Capelan M J et al. after recruitment of 17 patients (including 3 patients with a NE cancer): SD ≥6 months in 17.6%. |

| Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy | |||||

| 177Lu-Dotatoc | Phase II single arm | UNK (expressing somatostatin receptors) | Not specified | NCT04276597 | |

GEP = gastro-entero-pancreatic tract. UNK = unknown origin. SOC = standard of care. SD = stable disease. irDCR = immune-related disease control rate. OS = overall survival. PFS = progression free survival. ORR = objective response rate. irORR = immune-related objective response rate. Compounds: 5-FU (5-fluorouracil), oxaliplatin, irinotecan, nanoliposomal (nal)-irinotecan, docetaxel, paclitaxel, nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel, carboplatin, cisplatin, etoposide, topotecan, TLC388 (lipotecan), temozolomide, cabazitaxel, lurbinectedin, capecitabine, simmtecan = chemotherapy agents. Everolimus, DS-3078a = mTOR inhibitors. TAS-102 = a combination of a chemotherapy agent (trifluridine) and a thymidine phosphorylase inhibitor (tipiracil). Octreotide = somatostatin analogue. PEN-221 = a peptide targeting the somatostatin receptor 2 conjugated with a chemotherapy agent (emtansine, DM1). Cabozantinib = inhibitor of multiple tyrosine kinases, including the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-2, RET and MET. Bevacizumab = monoclonal antibody (mAb) targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A. Avelumab, durvalumab = mAbs targeting the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1). Nivolumab, pembrolizumab, spartalizumab, cetrelimab, dostarlimab, toripalimab, camrelizumab = mAbs targeting the anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1). Ipilimumab, tremelimumab = mAbs targeting the anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4). 177Lu-Dotatate or 177Lu-Dotatoc = radioactive compound (lutetium 177) conjugated to a somatostatin analogue (DOTATATE or DOTATOC). Talabostat mesylate = dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitor. Belinostat = histone deacetylase inhibitor. BI 764532, AMG 757 = anti-delta-ligand 3 (DLL3) and anti-CD3 bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs). XmAb20717 = anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 BiTE. Niraparib, rucaparib = poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. Elimusertib, barzosertib, M6620 = ATR inhibitors. PEG-SN38 = poly(ethylene) glycol (PEG) conjugate of SN38, which is the active moiety of irinotecan. MLN8237 (alisertib) = Aurora kinase A (AURKA) inhibitor. Erdafitinib = fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-1,2,3,4 inhibitor.

2.2. MYC family upregulation

MYC family proto-oncogenes, MYC, MYCL, MYC, are lineage-defining transcription factors mutually exclusively amplified in ~20% of SCLC(16). In SCLC genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) and human cell lines, MYCL amplification is enriched in the ASCL1high subtype, and MYC amplification in the NEUROD1high subtype(57,58), each driving distinct metabolic programmes(59). New evidence from SCLC GEMMs shows that MYC drives phenotypic evolution, promoting loss of NE identity through NOTCH upregulation, leading to a temporal shift from ASCL1high (NEhigh) to NEUROD1high (NElow) to YAP1high or POU2F3high (non-NE) states(60). In SCLC preclinical models, MYC sensitises cells to AURKA/B inhibition(57,61) (also shown in an early-phase clinical trial(62)) and arginine-deprivation(59), and enhances sensitivity to CHK1(47) and CDK7 inhibition(49)[Figure 3].

Aberrant activation of MYC family members also occurs in EP-PD-NECs [Figure 2, Table 1]. In GEP-PD-NECs, MYC is amplified in up to 51% of cases(18,19,26,28-30,44), whereas MYCN or MYCL amplification is rarer (8.3%(26,28) and 4.3%(30), respectively). In uterine-cervix-PD-NEC, either of the three MYC family members is amplified in 12.9-18.4% of cases(37,38). In prostate-PD-NEC, MYCN amplification or overexpression is highly prevalent (MYCN amplification; 40.5-52.0%)(50,53,63,64), whereas MYC amplification is less common (8.3%)(34)[Figure 2, Table 1]. Multiple lines of evidence point towards MYCN upregulation as a pathogenetic driver and a critical therapeutic vulnerability for prostate-PD-NEC, whereby MYCN upregulation promotes the emergence of an androgen receptor-independent PD-NEC phenotype(50,53-55,64). Inhibitors of MYCN synthetic lethal partners have shown promising preclinical activity in prostate-PD-NEC [Figure 3], and some of these compounds have entered clinical investigation [Table 2]. The epigenetic and transcriptional regulator enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2) is highly expressed in prostate-PD-NEC(53,54,65), where it cooperates with MYCN to repress androgen receptor signalling and drive a PD-NEC gene expression programme, and MYCN overexpression sensitises to EZH2 inhibition in vitro and in vivo(64). AURKA amplification or overexpression is also highly prevalent in prostate-PD-NEC (AURKA amplification; 40-68%, predominantly co-occurrent with MYCN amplification)(53,63). In fact, MYCN and AURKA reciprocally enhance protein stability by physical interaction, and AURKA inhibition destabilises MYCN, causing tumour regression in MYCN-overexpressing prostate-PD-NEC cell lines and mouse models(53,54,64). Transcriptomic analysis of prostate-PD-NEC human tumours and patient-derived xenografts has revealed significant upregulation of DDR (e.g. PARP1/2) and mitotic cell-cycle (e.g. CDK5) genes, alongside MYCN, and in vitro experiments have uncovered a critical link between MYCN and DDR pathways in the establishment and maintenance of a PD-NEC phenotype in prostate cancer cells(50,55). Both dual PARP/AURKA inhibition and PARP/CDK5 can suppress prostate-PD-NEC growth in vitro and in vivo, with the former combination showing enhanced activity compared to AURKA inhibition alone(50,55). Although a single-agent AURKA inhibitor yielded disappointing results in a molecularly unselected phase II clinical trial in patients with prostate-PD-NEC or adenocarcinoma with clinical features of androgen receptor independency progressing after antiandrogen therapy, tumour samples from exceptional responders showed MYCN and/or AURKA amplification or overexpression(66). Mechanistic studies investigating the biological function of MYC family members and potential associated therapeutic vulnerabilities in other EP-PD-NECs should be pursued.

2.3. Disruption of epigenetic regulation

Disruption of epigenetic regulation is among the most common oncogenic processes in SCLC(16) and EP-PD-NECs [Figure 2, Table 1]. CREB Binding Protein (CREBBP) and E1A Binding Protein p300 (EP300) encode for histone acetyltransferases and are mutually exclusively inactivated in ~13-15% of SCLC(16). They act as transcriptional co-activators by interacting with transcription factors and enabling their access to promoters, and their activity is counterbalanced by histone deacetylases (HDACs). In SCLC, CREBBP functions as a tumour suppressor and its deficiency sensitises to HDAC inhibition in GEMMs(67) and EP300 inhibition in cell lines and xenografts(68) [Figure 3].

Overexpression of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 or its protein product is frequent in SCLC(46) and prostate-PD-NEC(53,54,65). In SCLC, EZH2 promotes chemoresistance by epigenetic silencing of the cell-cycle regulator Schlafen family member 11 (SLFN11), and EZH2 inhibition prevents/reverts acquired resistance to DNA damaging agents in vitro and in vivo(69) [Figure 3]. In prostate-PD-NEC, EZH2 inhibitors are effective in suppressing tumour growth when used in combination with enzalutamide in Trp53/Rb1 knockout mouse models and derived cell lines(65), and as monotherapy in MYCN-overexpressing cell lines and xenografts(64) [Figure 3].

Genomic data indicates that a large proportion of EP-PD-NEC human samples of different sites of origin harbour alterations in at least one epigenetic regulator(18-20,26,28-32,34-42) [Figure 2, Table 1], with the AT-Rich Interaction Domain 1A (ARID1A), histone lysine methyltransferase 2 (KMT2) and histone lysine demethylase (KMD) family genes being the most frequently affected. This is supported by data from an organoid panel of 18 GEP-PD-NECs/MiNENs(45). Taken together, these data support epigenetic regulation as a viable therapeutic target in EP-PD-NECs.

2.4. Expression of the delta-like ligand 3

The delta like canonical Notch ligand 3 (DDL3) is a NOTCH ligand which inhibits NOTCH signalling through mechanisms yet to be fully elucidated in cancer. DLL3 is expressed with high prevalence (~70-80%) and specificity on the cell surface of NE cancers, including SCLC(70), LCPNEC(71), prostate-(72), GEP-(73), bladder-(74) and uterine cervix-PD-NECs(37), and DLL3 targeting is being explored as a strategy for selective delivery of anti-cancer treatment to NE cancer cells. Rovalpituzumab tesirine, an anti-DLL3 antibody-drug conjugated showed promising preclinical and early-phase clinical activity in DLL3-(over)expressing solid tumours(72,75,76), yet yielded poor efficacy and safety results in subsequent larger clinical trials(77,78). This led to discontinuation of further development of this drug. In SCLC, adoptive cell therapies using DLL3 as target antigen, including bispecific T-cell engagers monoclonal antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor T-cells, have shown in vitro and in vivo tumour-suppression activity, which is enhanced by the combination with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)(79,80) [Figure 3]; these strategies are currently in early-phase clinical investigation in patients with SCLC(77) and EP-PD-NEC [Table 2].

2.5. Upregulation of antiapoptotic signalling

The BCL2 apoptosis regulator (BCL2) is an anti-apoptotic member of the BCL2 family of mitochondrial apoptosis regulators. The majority of SCLC human samples overexpress BCL2 protein(81) and BCL2 mRNA expression is predominantly high in SCLC cell lines, and predicts in vitro and in vivo SCLC sensitivity to the selective BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax(82). The combination of venetoclax and a bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) protein family inhibitor has also shown promising preclinical activity in SCLC(83) [Figure 3]. A clinical trial is currently evaluating venetoclax in combination with or after first-line platinum/etoposide +/- ICB in patients with SCLC (NCT04422210). BCL2 inhibition may also translate to EP-PD-NECs. In fact, a transcriptomic analysis of prostate-PD-NEC human samples, cell lines and patient-derived xenografts revealed significant BCL2 mRNA and protein overexpression. Furthermore, in vivo and in vitro prostate-PD-NEC models showed sensitivity to the pan-BCL2 family inhibitor navitoclax and was synergistic with WEE1 inhibition(84) [Figure 3]. Expression of BCL2 protein has been also reported at a high prevalence in pancreatic-(85) and colorectal-PD-NEC human samples(23), providing further rationale for extending investigation of BCL2 inhibitors to PD-NECs from other anatomical sites.

3. ‘non-NE cancer-like’ vulnerabilities of EP-PD-NECs

3.1. Dysregulation of receptor tyrosine kinase pathways

Aberrant activation of receptor tyrosine kinase pathways is common in non-NE epithelial cancers from different anatomical sites, including the GEP tract, prostate, bladder and female genital tract(86,87), whereas it is infrequent in SCLC(16,46). Activating mutations in KRAS and BRAF (predominantly V600E) are reported in GEP-PD-NECs at a similar frequency as in GEP adenocarcinomas(18-28,44,88-90)[Figure 2, Table 1]. Similar to their adenocarcinoma counterparts, pancreatic-PD-NEC is enriched in KRAS mutations (23.1-41.7%)(18,28), and colorectal-PD-NEC enriched in KRAS (8.3-60%)(18,23-27,44,90) and BRAF mutations (4.2-58.6%)(18,23-27,44,90), with the latter predominantly occurring in the right colon. This suggests that targeted treatments for GEP adenocarcinomas may also find application in patients with PD-NECs from the same site of origin. For example, BRAF inhibitors are emerging as promising therapeutic strategies for BRAFV600E-mutant colorectal-PD-NEC. Both single-agent BRAF inhibitors and combined BRAF and MEK1/2 inhibitors have shown remarkable activity in BRAFV600E-mutant colorectal-PD-NEC human cell lines, xenografts and patients (case reports)(25,89,91,92) [Figure 2]. A recent study showed that BRAFV600E-mutant colorectal-PD-NEC has an EGFR methylation signature close to that of melanoma, which suppresses EGFR signalling and results in response to single-agent BRAF inhibition(25). Collectively, these data support clinical investigation of BRAF inhibitors in a subset of patients with colorectal-PD-NEC.

Dysregulations of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR pathway are also recurrent events in EP-PD-NECs of different sites of origin [Figure 2, Table 1]. Mutations and amplifications or copy number gains of PI3KCA are more frequent in PD-NECs from the colon-rectum (4.9-12.5%)(18,24,26,27), bladder (14.8-16.7%)(35,36) and uterine cervix (12.2-46.7%)(37-41), whereas mutations and deletions or copy number losses of PTEN are more frequent in prostate-PD-NEC (16.7-52.9%)(31-34,63). Therapeutic strategies targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling are currently being evaluated in clinical trials in a number of non-NE epithelial cancers(87), and may also apply to patients with EP-PD-NEC harbouring the same molecular vulnerabilities.

3.2. Microsatellite instability

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is an established oncogenic driver for a subset of GEP adenocarcinomas, most commonly of colorectal and gastric origin, occurring at a frequency of ~7.5-22%(93). MSI is typically associated with a high tumour mutation/neoantigen burden, dense lymphocytic infiltrates and immune checkpoint upregulation, and is a positive predictor of response to ICB(94). Clinical trials utilising ICB demonstrated durable responses in approximately half of patients with MSI-high cancers, including GEP adenocarcinomas(94-96). This led to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of two anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies: pembrolizumab for all patients with MSI-high cancer, and nivolumab for patients with MSI-high metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma.

MSI-high has a variable frequency in GEP-PD-NECs (0-69.2%), predominantly occurring in those of gastric and colorectal origins(18-20,24,25,88,90,97-99)[Table 3]. Similar to MSI-high gastric and colorectal adenocarcinomas, MSI-high GEP-PD-NECs have more conspicuous lymphocytic infiltrates, are significantly enriched in CpG island methylator phenotype and BRAF mutation, and have a more favourable prognosis compared to their microsatellite stable counterpart(88,97,98). Overall, there is indication that MSI is a site-specific driver for a subgroup of GEP-PD-NECs, mainly of gastric and colorectal origin, which share biological similarities with MSI GEP adenocarcinomas, and may also benefit from ICB.

Table 3. Immune biomarkers of Extra-Pulmonary NeuroEndocrine Carcinomas.

| Microsatellite instability | |||||||

| Reference | n | 2019 WHO category | Site of origin | Disease stage | Methods | MSI-high cases | |

| Venizelos, 2021(18) | 152 | PD-NEC | Oesophagus (n=18), stomach (n=16), pancreas (n=13), gallbladder/biliary y=tract (n=3), colon (n=45), rectum (n=36), unknown primary (n=19), (not reported n=2) | Stage IV: 79.6% Stage I/II/III: 20.4% |

PCR (panel**: BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, MONO-27, Penta C and Penta D) | 8/152 (5.3%) | |

| Puccini, 2020(19) | 135 | PD-NEC or G3-WD-NET (relative proportions not reported) | GEP | n/a | NGS-based (MSI-high: ≥46 loci with insertions or deletions) | 5/135 (3.7%) | |

| Milione, 2017(97) | 112 | PD-NEC | Oesophagus (n=5), stomach (n=23), duodenum (n=5), ileum-cecum/appendix (n=13), colon-rectum (n=42), pancreas (n=22), gallbladder (n=2) | Stage IV: 59.8% Stage I/II/III: 40.2% |

IHC for MMR proteins* | 4/60 (6.7%) (only 60 cases subjected to MSI analysis) | |

| Sahnane, 2015(88) | 89 | PD-NEC (n=53), MiNEN (n=36) | Oesophagus (n=6), stomach (n=36), duodenum (n=4), colon-rectum (n=37), pancreas (n=3), gallbladder (n=3) | Stage IV: 24% Stage II/III: 76% |

PCR (panel**: BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-22, NR-24) and IHC for MMR proteins* | Whole pop: 11/89 (12.4%) [Oesophagus: 0%, stomach: 11.1%, duodenum: 25%, colon-rectum: 16.2%, pancreas: 0%, gallbladder: 0%] PD-NECs: 7/53 (13.2%) |

|

| Busico, 2019(20) | 39 | PD-NEC | Stomach (n=11), pancreas (n=6), colon (n=22) | Stage IV: 66.7% Stage I/II/III: 33.3% |

IHC for MMR proteins* | 27/39 (69.2%) | |

| La Rosa, 2012(98) | 34 | PD-NEC or MiNEN (relative proportions not provided) | Colon-rectum | Stage IV: 25-33.3% | PCR (panel**: BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-22, NR-24) | 5/34 (14.7%) | |

| Xing, 2020(101) | 33 | PD-NEC | Oesophagus (n=3), stomach (n=21), small bowel (n=1), colon (n=1), pancreas (n=6), gallbladder (n=1) | Stage IV: 12.1% Stage I/II/III: 89.9% |

NGS-based classifiers mSINGS, MSIsensor, and MSIseq; MSI-high status: when >2 software programs showed MSI-high. | 0/33 (0%) | |

| Olevian, 2016(90) | 32 | PD-NEC (n=14), MiNEN (n=18) | Colon-rectum | Stage IV: 59.4% Stage I/II/III: 40.6% |

either PCR (panel**: BAT25, BAT26, D2S123, D5S346, D17S250 + CAT25) or IHC for MMR proteins* | 2/29 (6.9%) (only 29 cases subjected to MSI analysis) |

|

| Lee, 2021(24) | 30 | PD-NEC | Colon-rectum | Stage IV: 36.7% Stage I/II/II: 63.3% |

IHC for MMR proteins* and PCR (panel**: BAT25, BAT26, D2S123, D5S346, D17S250) |

1/30 (3.3%) | |

| Capdevila, 2019(25) | 25 | PD-NEC | Colon | n/a | PCR (panel**: BAT25, BAT26, NR-21, NR-24, MONO-27) and IHC for MMR proteins* | 0/24 (0%) (only 24 cases subjected to MSI analysis) | |

| Pei, 2021(38) | 51 | PD-NEC | Uterine cervix | Stage IV: 3.9% Stage II: 96.1% |

NGS-based (criteria for MSI-high definition not reported) | 2/51 (3.9%) | |

| Cimic, 2020(37) | 31 | PD-NEC | Uterine cervix | n/a | NGS-based (MSI-high: ≥46 altered microsatellite loci) | 0/31 (0.0%) | |

| Ohmoto, 2021(42) | 14 | PD-NEC | Head/neck | Locally advanced (Stage III, IVA, IVB): 78.6% Metastatic (Stage IVC): 21.4% |

MSI quantitative score: proportion of MSI unstable sites to the total 130 homopolymer MSI marker sites assessed (targeted NGS-based). MSI-high: MSI score ≥0.1. | 0/14 (0.0%) | |

| PD-L1 expression (IHC) | |||||||

| Reference | n | 2019 WHO category | Site of origin | Ab clone used | Scoring system and positivity threshold | Stained cells | PD-L1 positive cases |

| Puccini, 2020(19) | 135 | PD-NEC or G3-WD-NET (relative proportions not reported) | GEP | SP142 | n/a | n/a | 8/135 (6.0%) |

| Ferrata, 2019(104) | 57 | PD-NEC (n=48), MiNEN (n=6), G3-WD-NET (n=3) | GEP (n=21), lung (n=16), genitourinary (n=8), UNK (n=7), head/neck (n=4), MCC (n=1). | EPR19759 (ab213524) | TPS ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 9/57 (15.8%) |

| unclear | Immune cells | 14/57 (24.6%) | |||||

| Koshkin, 2018(75) | 53 | PD-NEC | Bladder | SP142 or SP263 | TPS ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 0/53 (0.0%) |

| ≥1% of the tumour area occupied by PD-L1 expressing immune cells | Immune cells | 16/53 (30.2%) | |||||

| Yang, 2019(105) | 43 | PD-NEC | Stomach | 28-8 (ab205921) | Yang et al. score >4 | Tumour cells | 21/43 (48.8%) |

| Cimic, 2020(37) | 39 | PD-NEC | Uterine cervix | 22C3 | CPS ≥1% | Tumour and immune cells | 4/39 (10.3%) |

| Roberts, 2017(106) | 37 | PD-NEC | GEP | E1L3N | TPS ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 5/37 (13.5%) |

| ≥1% of the tumour area occupied by PD-L1 expressing immune cells | Immune cells | 10/37 (27.2%) | |||||

| Salhab, 2018(107) | 34 | PD-NEC | Genitourinary (n=18), UNK (n=10), GEP (n=5), head/neck (n=1). | E1L3N | CPS ≥1% | Tumour and immune cells | 12/34 (35.3%) |

| Schultheis, 2015(108) | 33 | PD-NEC | n/a | 5H1 or E1L3N | Allred Score >2 | Tumour cells | 0/33 (0.0%) |

| Immune cells | 7/33 (21.2%) | ||||||

| Xing, 2020(99) | 31 | PD-NEC | GEP | 22C3 | TPS ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 9/31 (29.0%) |

| Bösch, 2019(109) | 18 | PD-NEC | GEP | E1L3N | TPS ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 3/18 (16.7%) |

| Kim, 2016(110) | 17 | PD-NEC or G3-WD-NET (relative proportions not reported) | GEP | SP142 | TPS ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 7/17 (41.2%) |

| Ono, 2018(111) | 16 | PD-NEC | GEP | n/a | TPS ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 6/16 (37.5%) |

| Busico, 2019(20) | 11 | PD-NEC | GEP | n/a | ≥1% (scoring system n/a) | Tumour cells | 0/39 (0%) |

| Immune cells | 11/39 (28.2%) | ||||||

| Morgan, 2019(112) | 10 | PD-NEC | Uterine cervix | SP263 | H-score ≥1 % | Tumour cells | 7/10 (70.0%) |

| Immune cells | 2/10 (20.0%) | ||||||

| Tumour mutation burden | |||||||

| Reference | n | 2019 WHO category | Site of origin | Platform used | Median or mean (mut/Mb) | Definition of high TMB | Cases with high TMB |

| Chalmers, 2017(121) | 117, 674 | PD-NEC | UNK | NGS 365-gene panel | 6.3, 2.7 (median) | ≥20 mut/Mb | 8.5%, 6.1% |

| n/a | PD-NEC | Colon-rectum | NGS 365-gene panel | ≥20 mut/Mb | ~5% | ||

| Venizelos, 2021(18) | 152 | PD-NEC | GEP + UNK | NGS 360-gene panel | 5.1 (median) | ||

| Puccini, 2020(19) | 135 | PD-NEC or G3-WD-NET (relative proportions not reported) |

GEP | NGS 592/44-gene panel | 9.5 (mean) | ≥17 mut/Mb | 7% |

| Chen, 2020(44) | 83 | PD-NEC | Colon-rectum | Different NGS platforms*** | 5.2 (median) | ||

| Li, 2021(30) | 46 | PD-NEC | Oesophagus | WES | 2.31 (median) | ||

| Xing, 2020(99) | 29 | PD-NEC | GEP | WES | 5.7 (median) | ||

| Cimic, 2020(37) | 39 | PD-NEC | Uterine cervix | NGS 592-gene panel | ≥17 mut/Mb | 3% | |

| Hillman, 2020(40) | 15 | PD-NEC | Uterine cervix | WES | 1.7 (median) | ||

| Chang, 2018(35) | 17 | PD-NEC | Bladder | WES/WGS | 10.7 (median) | ||

| Shen, 2018(36) | 12 | PD-NEX | Bladder (n=11), prostate (n=1) | WES/WGS | 9.8 (median) | ||

| Ohmoto, 2021(42) | 14 | PD-NEC | Head/neck | NGS 523-gene panel | 7.1 (median) | ≥10 mut/Mb | 21.4% |

n = number of patients. MiNENs = mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. G3-WD-NETs = high grade (ki-67>20%) well differentiated neuroendocrine tumours. GEP = gastro-entero-pancreatic tract. UNK = unknown origin. MCC = Merkel cell carcinoma. PCR = polymerase chain reaction. IHC = immunohistochemistry. NGS = next generation sequencing. WES = whole exome sequencing. WGS = whole genome sequencing. n/a = information not available. Antibodies used to detect the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1): 5H1 = mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) by Lieping Chen’s Laboratory (Yale University, US). E1L3N = rabbit mAb by Cell Signaling Technology. EPR19759 (ab213524) = rabbit recombinant mAb by Abcam. SP142 = rabbit mAb by Ventana (Roche). 22C3 = mouse mAb by Dako/pharmDx (Agilent). SP263 = rabbit mAb by Ventana (Roche). 28-8 (ab205921) = rabbit recombinant mAb by Abcam. Allred score: ranges from 0 to 8 and combines the percentage of PD-L1 expressing cells subdivided into 6 categories (0-5) with the intensity of PD-L1 expression subdivided into 4 categories (0-3). TPS = tumour proportion score; percentage of PD-L1 expressing tumour cells on the total of viable tumour cells. H-score: ranges from 0 to 300 and is estimated by multiplying the percentage of PD-L1 expressing cells by the intensity of PD-L1 expression (0-3). CPS = combined positive score; percentage of PD-L1 expressing tumour and immune cells on the total of viable tumour cells. Yang et al. score = combines the percentage of PD-L1 expressing tumours cells subdivided into 4 categories (0-3) with the intensity of PD-L1 expression subdivided into 4 categories (0-3). *mismatch repair proteins (MLH-1, MSH-2, MSH-6, PMS-2). **panel of selected microsatellite loci analysed by PCR.***publicly accessible NGS database from the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) Project Geno mics, Evidence, Neoplasia, Information, Exchange (GENIE) consortium. Studies selected where those which included samples from ≥10 patients.

4. Tumour-type agnostic immune biomarkers of EP-PD-NECs

ICB has proven effective in eliciting T-cell anti-tumour cytotoxicity with dramatic and durable responses in a subset of patients with cancer. Yet, the majority of patients do not respond to ICB or rapidly develop resistance (100). Currently, IHC expression of PD-L1, high levels of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), and high tumour mutation burden (TMB) predict ICB benefit in a number of cancer types(101,102). However, these are imperfect predictive biomarkers and there is an urgent need for improved biomarkers for patient selection and identification of synergistic therapeutic combinations.

ICB is currently in clinical trials in patients with EP-PD-NEC [Table 2], with initial evidence of activity for the combination of the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody nivolumab with the anti-CTLA4 monoclonal antibody ipilimumab(103). However, the EP-PD-NEC immune landscape is not fully characterised. IHC expression of PD-L1 is reported in 6-70% of patients(19,20,37,74,99,104-112)[Table 3]; similar variability is observed in other cancer types, including SCLC, and is due to factors including spatial and temporal intra-tumour heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression, lack of standardised methods, and differences in clinico-pathological characteristics across studies(100,101). In EP-PD-NECs, IHC expression of PD-L1 is more prevalent in tumour-associated immune cells than in tumour cells(20,74,104,106-108), and is most commonly of low intensity and restricted to a small proportion of the tumour sample(74,99,104,107,108,112). Tumour-associated immune cells are present in the majority of EP-PD-NECs, with TILs reported in 45.5-100% of cases(99,104,106,108,109,112), although usually at low density and located at the tumour edges or at the tumour/stroma interface, rather than within the tumour parenchyma(106,108). Recently, transcriptomic profiling of oesophageal-PD-NEC human samples revealed downregulation of immune response pathways with significantly reduced expression of TIL and cytotoxic-TIL gene signatures compared to epithelial non-NE oesophageal cancers. In addition, IHC showed exclusion of cytotoxic-TILs from the tumour parenchyma in 85% of cases(30). Although further characterisation of tumour-associated immune cell populations in EP-PD-NECs is needed, the evidence favours a predominant ‘immune-altered’ phenotype, as per Galon et al.(113). This suggests that the majority of patients with EP-PD-NEC will likely show low sensitivity to ICB alone, but could potentially benefit from the combination of ICB with therapies that can stimulate immune checkpoint upregulation and immune cell infiltration, such as DNA-damaging agents. For example, ICB alone has proven ineffective in SCLC, which is known to be immunologically ‘altered’/’cold’, in spite of a high TMB(114). However, the combination of ICB with first-line platinum/etoposide recently received FDA approval with superior efficacy over chemotherapy alone, in spite of a modest overall survival gain (<3 months)(115,116). Compelling preclinical evidence shows enhanced ICB via combined inhibition of cell-cycle or DDR regulators, such as CHK1, PARP (via cGAS-STING pathway)(117) or CDK7(118), which generates genomic instability to stimulate the host adaptive immune response [Figure 3]. A number of ICB combination strategies have entered clinical investigation in SCLC(11) and EP-PD-NECs [Table 2].

Pembrolizumab has US FDA approval for the treatment of patients with advanced solid tumours and TMB≥10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb). In SCLC, a high TMB enriched for clinical benefit in patients treated with ICB alone in the phase II Checkmate032 trial (TMB assessed by whole-exome sequencing in tumour tissue)(119), whereas it did not predict increased response to ICB in combination with platinum/etoposide in the phase III IMpower133 trial (TMB assessed by targeted sequencing in cell-free DNA)(120). However, the sensitivity of the methods for TMB assessment and the threshold for TMB-high differed between these two studies. Overall, EP-PD-NECs exhibit a lower median TMB (1.7-7.1 mut/Mb)(18,19,30,37,40,42,44,99,121) [Table 3] than SCLC (~9 mut/Mb)(16), which may be partially explained by a lesser role for tobacco smoking in EP-PD-NEC pathogenesis. Bladder-PD-NEC represents an exception with a median TMB close to that of SCLC [Table 3], although secondary to enrichment in APOBEC rather than tobacco smoking mutational signature(35,36). Nevertheless, a fraction of patients with EP-PD-NEC (~3-21.4%) exhibit a high TMB and may benefit from ICB alone.

5. Origin and NE lineage plasticity

The origin of EP-PD-NECs remains elusive. Accumulating evidence from clinical observations, genomic and transcriptomic studies suggests a distinct pathogenesis and, in some anatomical sites, cell of origin for WD-NETs and PD-NECs(122-124). WD-NETs are thought to develop from mature NE cells or pluripotent precursors primed for a NE lineage commitment(122,123). SCLC predominantly originates from pulmonary NE cells(125), whereas the cell of origin of EP-PD-NECs has never been formally identified. Comparative analyses of the mutational landscape of PD-NECs, non-NE epithelial cancers, and mixed NE/non-NE epithelial cancers from the GEP, bladder and prostate point towards a common clonal precursor for same-organ PD-NEC and non-NE epithelial cancer histologies at these anatomical sites(23,25,27,28,31,35,36). Multi-omic analyses of oesophageal-, bladder-, and prostate-PD-NECs indicate that, in spite of a close resemblance with their non-NE epithelial cancer counterparts at a mutational level, their transcriptomic(30,84,126-128) and epigenetic profiles(126-128) largely overlap with those of SCLC. A study looking at clonal phylogeny of bladder-PD-NECs showed that site-specific mutations shared with non-NE epithelial cancers appear earlier than PD-NEC phenotype-specific genomic events, such as TP53/RB1 loss or genome doubling(35). Therefore, the predominant emerging hypothesis is that EP-PD-NECs have distinct cells of origin, shared with same-organ non-NE epithelial cancers(6), but a convergent phenotypic evolution shared with SCLC(35,126-128). Two main, non-mutually exclusive mechanisms of EP-PD-NEC pathogenesis have been postulated: 1) origin from a multi-potent, undifferentiated (stem cell-like) site-specific precursor with the ability to alternatively acquire a non-NE cancer cell identity, 2) or through NE trans-differentiation from an originally non-NE epithelial cancer cell. The latter phenomenon, known as NE lineage plasticity, is emerging as the main mechanism underpinning the emergence of a lethal NE phenotype in lung and prostate adenocarcinoma following targeted therapies, such as anti-EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors and the antiandrogens enzalutamide and abiraterone. Lineage plasticity is the ability of cancer cells to transition to an alternative developmental lineage to adjust to adverse environmental conditions, such as those created by the selective pressure of targeted therapies, leading to loss of dependency on the original oncogenic driver, treatment resistance and tumour progression(6,7,129). To date, non-NE to NE cancer lineage transition secondary to therapeutic suppression of an oncogenic driver has been documented in the lung and prostate; a number of putative drivers have been identified, including TP53/RB1 loss, MYCN amplification or overexpression and perturbations in epigenetic regulators such as EZH2, establishing vulnerabilities that can be therapeutically leveraged(7,129). However, this phenomenon may also occur at other anatomical sites, and through different mechanisms, and will likely become increasingly observed in clinic due to the implementation of targeted therapies for a wider population of patients with cancer. This may include patients with non-NE epithelial cancers from the GEP tract, bladder or uterine cervix where the use of targeted therapies has so far been limited, yet is likely to increase with the rapid progress in their molecular and biological characterisation. For example, a study in patient samples provided initial evidence of NE trans-differentiation in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and NE trans-differentiation was driven by MYC overexpression in GEMMs, and was associated with resistance to gemcitabine chemotherapy and increased by gemcitabine in human cell lines(130). In addition, anatomical sites other than the lung and prostate may be more prone to a different lineage reprogramming, such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, when cancer cells are forced into an identify shift by anti-cancer treatment(7).

Finally, NE lineage plasticity might not only occur in the late stages of tumour evolution, but also early in the oncogenic process(129), and may drive intra-tumour NE/non-NE phenotypic heterogeneity in mixed epithelial cancers and, at least in part, be implicated in the development of de novo PD-NECs. This implies that NE lineage plasticity-directed therapies currently under investigation for treatment-induced PD-NECs could also potentially find application for mixed or pure de novo PD-NECs.

The hypotheses surrounding the origin of EP-PD-NECs presented herein are still debated and may not explain the whole spectrum of pathogenetic pathways. For example, two studies proposed a possible evolution of SCLC and LCPNEC from pulmonary-WD-NETs, based on genomic sequencing of patient samples utilising a targeted panel of 40/88 genes commonly altered in these cancers, suggesting that this may also apply to EP-PD-NECs(131,132), although progression from a WD-NET to a PD-NEC is an extremely rare observation in clinic, both in and outside of the lung.

6. Conclusions

There is growing interest in EP-PD-NECs within the scientific and clinical communities to aid the management of these patients which are becoming more common in practice. This increase in patients is partially attributable to the improved sensitivity of methods for histopathological diagnosis, in particular the wider use of NE IHC markers. In addition, a new entity is emerging, namely treatment-induced PD-NEC, resulting from the phenotypic transition of pre-existing epithelial non-NE cancers. Rise in incidence of this is anticipated as molecularly targeted therapies are more widely implemented for the treatment of non-NE cancers. In addition, the more extensive use of liquid biopsies enabling temporal monitoring of changes in the tumour genotype and phenotype may unveil a higher incidence of treatment-induced non-NE to NE cancer lineage transition. Therefore, there is a demand for more research into this lethal PD-NEC diagnosis, for which chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment, yet yields short-lived benefits.

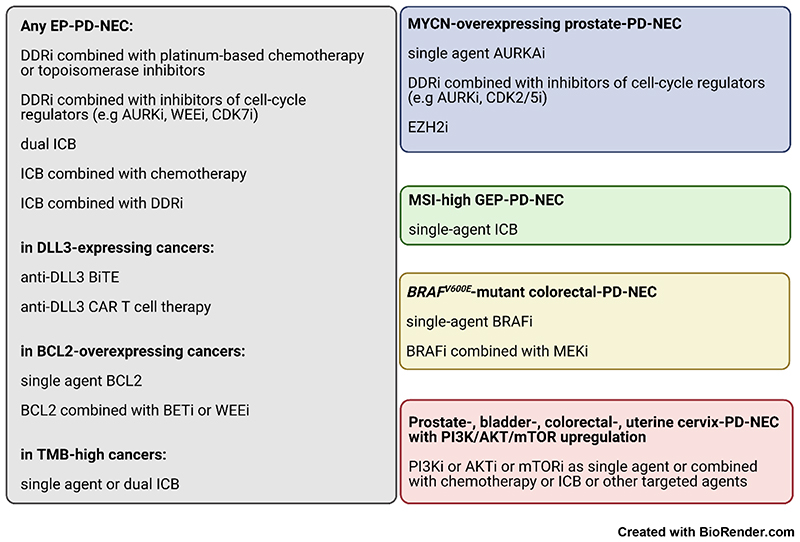

This review has attempted to provide a comprehensive overview of newly emerging molecular vulnerabilities of EP-PD-NECs and shed light on potential directions for research and treatment development [Figure 3]. New insight into multi-omic features of EP-PD-NECs and NE cancer lineage plasticity are paving the way to new therapeutic opportunities [Figure 4, “i” suffix = inhibitor] and also increasing the understanding of the pathogenesis of these cancers.

Figure 4. Summary of emerging therapeutic strategies for Extra-Pulmonary NeuroEndocrine Carcinomas.

DDR = DNA damage repair. ICB = immune checkpoint blockade. BiTE = bispecific T cell engager. CAR T cell therapy = chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. TMB = tumour mutation burden. The ‘i’ as suffix of the name of a molecular marker means “inhibitor”. Remaining acronyms are defined in Table 4.

SCLC is the best characterised NE cancer, and thus offers a paradigm for modelling EP-PD-NEC. For example, the differential expression of NE lineage defining transcriptions factors underpins the new emerging SCLC molecular classification, and is associated with unique therapeutic vulnerabilities(12,14), and may aid in deciphering biological heterogeneity within the EP-PD-NEC family. Variability in genomic features across and within EP-PD-NEC subgroups per site of origin, such as a different prevalence of TP53 and RB1 inactivation, underscores the need for a more granular classification of these cancers. Transcriptomic profiling of 18 GEP-PD-NEC/MiNEN organoids has unveiled molecular subtypes differentially enriched in NE lineage defining transcription factors, including ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3 and ATOH1, shedding light on their potential role in EP-PD-NEC biology(45). This was corroborated by a recent study in oesophageal-PD-NEC (human samples, n=38), where unsupervised clustering analysis of RNA sequencing data split the population in an ASCL1high and a NEUROD1high subgroup with similar gene enrichment to their SCLC counterparts(30).

Besides a better characterisation of EP-PD-NEC molecular subgroups, an improved understanding of the EP-PD-NEC immune landscape and tumour microenvironment is needed to inform development of novel effective therapeutic approaches. For example, inhibitors of the VEGF/VEGFR pathway are currently being investigated in combination with chemotherapy or ICB in the clinical setting in patients with advanced EP-PD-NEC, mainly of GEP origin [Table 2], with initial encouraging results(133-135). The rationale behind this is that targeting angiogenesis is known to improve the efficacy of chemotherapy and ICB in a variety of solid cancers(136). In addition, GEP-PD-NECs have a low vascular density, yet prominent angiogenesis with increased endothelial cell proliferation and abnormal vascular architecture, likely secondary to hypoxia(137), suggesting that targeting angiogenesis might be effective in these cancers. In support to this, a recent study has demonstrated potent in vivo anti-tumour activity for two VEGF inhibitors in xenograft models of SCLC and colon-PD-NEC(138). Nevertheless, angiogenesis in EP-PD-NECs remains poorly studied.

Finally, clinically useful biomarkers and patient-relevant preclinical models of EP-PD-NECs remain urgently needed. Initial studies of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) and circulating tumour DNA in patients with EP-PD-NEC provide evidence of their feasibility and potential clinical utility in these cancers(21,139), with a largely untapped potential to overcome the limited availability of tumour tissue. In SCLC, CTCs can give rise to animal models which faithfully recapitulate the morphology and treatment sensitivity of donor patients’ tumours; so-called CTC-Derived eXplants (CDX)(13,48,140). CDX can be generated from a 10mL blood sample and at multiple time points from the same patient, and are proving valuable tools for in vivo and ex vivo biological studies and drug screening(13,48,140). The CDX technology may also find application in NE cancers outside the lung, as shown in a recent study reporting on a CDX of treatment-induced prostate-PD-NEC(141). NE cancer organoids are proving reproducible and tractable platforms that can support preclinical investigation in EP-PD-NECs.

Acknowledgments

Please see Table 4 for a list of genes cited in this paper.

Table 4. List of genes cited in the paper (HUGO Genome Nomenclature Committee).

| ASCL1 | Achaete-Scute Family bHLH Transcription Factor 1 |

| NEUROD1 | Neurogenic Differentiation Factor 1 |

| ATOH1 | Atonal bHLH Transcription Factor 1 |

| POU2F3 | POU Class 2 Homeobox 3 |

| YAP1 | Yes1 Associated Transcriptional Regulator |

| TP53 | Tumor Protein P53 |

| RB1 | RB Transcriptional Corepressor 1 |

| STK11 | Serine/Threonine Kinase 11 |

| KEAP1 | Kelch Like ECH Associated Protein 1 |

| MDM2 | MDM2 Proto-Oncogene |

| TP73 | Tumor Protein P73 |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A |

| CCNE1 | Cyclin E1 |

| WEE1 | WEE1 G2 Checkpoint Kinase |

| CHEK1 (alias symbol CHK1) | Checkpoint Kinase 1 |

| ATR | ATR Serine/Threonine Kinase |

| TOP1 | DNA Topoisomerase I |

| MYC | MYC Proto-Oncogene, bHLH Transcription Factor |

| MYCL | MYCL Proto-Oncogene, bHLH Transcription Factor |

| MYCN | MYCN Proto-Oncogene, bHLH Transcription Factor |

| AURKA | Aurora Kinase A |

| AURKB | Aurora Kinase B |

| CDK7 | Cyclin Dependent Kinase 7 |

| EZH2 | Enhancer Of Zeste 2 Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Subunit |

| PARP1 | Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 |

| PARP2 | Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 2 |

| CDK5 | Cyclin Dependent Kinase 5 |

| CREBBP | CREB Protein |

| EP300 | E1A Binding Protein p300 |

| SLFN11 | Schlafen Family Member 11 |

| DLL3 | Delta Like Canonical Notch Ligand 3 |

| BCL2 | BCL2 Apoptosis Regulator |

| KRAS | KRAS Proto-Oncogene, GTPase |

| BRAF | B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase |

| MEK1 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1 |

| MEK2 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 2 |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 |

| MTOR | Mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin Kinase |

| PIK3CA | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha |

| PTEN | Phosphatase And Tensin Homolog |

| CD274 (alias symbol PD-L1) | CD274 molecule |

| PDCD1 (alias symbol PD-1) | Programmed Cell Death 1 |

| CTLA4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4 |

| cGAS (CGAS in humans) | Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase |

| STING1 | Stimulator Of Interferon Response cGAMP Interactor 1 |

| VEGF(A/B/C/D) | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (A/B/C/D) |

| FLT1 (alias symbol VEGFR1) | Fms Related Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 1 |

| KDR (alias symbol VEGFR2) | Kinase Insert Domain Receptor |

| FLT4 (alias symbol VEGFR3) | Fms Related Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 4 |

Funding acknowledgment

M. Frizziero, E. Kilgour, K. L. Simpson, D. G. Rothwell, K. K. Frese, M. Galvin, and C. Dive are affiliated with/funded by Cancer Research UK: Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute (A27412), Manchester CRUK Centre Award (A25254), CRUK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence (A20465), and CRUK Manchester Experimental Cancer Medicines Centre (A25146). D. A. Moore also is affiliated with/funded by CRUK.

Footnotes