Abstract

Background

Patients with asthma are at risk of hospitalisation with influenza, but the reasons for this predisposition are unknown.

Study setting

A prospective observational study of adults with PCR-confirmed influenza in 11 UK hospitals, measuring nasal, nasopharyngeal and systemic immune mediators and whole-blood gene expression.

Results

Of 133 admissions, 40 (30%) had previous asthma; these were more often female (70% vs 38.7%, OR 3.69, 95% CI 1.67 to 8.18, P = 0.0012), required less mechanical ventilation (15% vs 37.6%, χ2 6.78, P=0.0338) and had shorter hospital stays (mean 8.3 vs 15.3 d, P=0.0333) than those without. In patients without asthma, severe outcomes were more frequent in those given corticosteroids (OR=2.63, 95% CI=1.02-6.96, P=0.0466) or presenting >4 days after disease onset (OR 5.49, 95% CI 2.28–14.03, P=0.0002). Influenza vaccination in at-risk groups (including asthma) were lower than intended by national policy and the early use of antiviral medications were less than optimal. Mucosal immune responses were equivalent between groups. Those with asthma had higher serum IFN-α but lower serum TNF, IL-5, IL-6, CXCL8, CXCL9, IL-10, IL-17 and CCL2 levels (all P<0.05); both groups had similar serum IL-13, total IgE, periostin and blood eosinophil gene expression levels. Asthma diagnosis was unrelated to viral load, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-5 or IL-13 levels.

Conclusions

Asthma is common in those hospitalised with influenza but is not typically the classical Type 2-driven disease. Instead, they tend to be female and have ‘intrinsic’ asthma with mild serum inflammatory responses and good outcomes.

Keywords: Influenza, asthma, pathogenesis, mucosal immunity, viral lung disease

Introduction

Influenza viruses cause a continuous threat to global health, mutating and spreading in both human and animal populations. The Influenza Clinical Information Network (FLU-CIN) reported that asthma was the commonest pre-existing risk factor for hospitalization, being present in 25.3% of 1,520 patients admitted with influenza A infection[1]. This apparent increased risk is reported in other studies which paradoxically also show that individuals with asthma experience less severe outcomes and are discharged earlier from hospital than those without asthma[2, 3]. There have been many studies of immune responses to influenza infection[4, 5], but none has focussed on characterizing the effect of asthma in the host responses to natural influenza.

The Mechanisms of Severe Acute Influenza Consortium (MOSAIC) recruited patients with clinical influenza presenting to hospitals in London and Liverpool (UK) during the winters of 2009/10 and 2010/11, periods of intense influenza activity. We previously reported enrichment for a host genetic variant of the interferon-inducible transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) allele SNP rs12252-C in hospitalized patients[6] and that circulating influenza viruses evolved and change in character over time[7] and the progression of whole-blood transcriptional signatures and mediator levels from interferon-induced to neutrophil-associated patterns in severe disease[8], but have not yet described the clinical details of the study population.

We now provide detailed clinicopathological analysis of the MOSAIC cohort, segregating patients with and without asthma and confirmed influenza and focusing on measures of nasal mucosal and systemic inflammation as potential causes of enhanced disease. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract[9].

Methods

Study design and cohort

Adult patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms were recruited between December 2009 to March 2011 from 3 hospitals in Liverpool and the Wirral (Northwest England) and 6 hospitals in London. A detailed medical history, including the presence of a diagnosis of asthma, along with a record of prescribed medications on admission was obtained from case notes by specialized data collectors based on Department of Health guidelines and continued for the first 14 days of admission[10]. Three patients who were coded as having both asthma and COPD were allocated to the non-asthma group in order to avoid potential confounding (one patient had radiological evidence of emphysema; the second patient had clinical COPD and bronchiectasis secondary to crack-cocaine use and the third patient was clinically coded as having an exacerbation of COPD rather than asthma). The severity of respiratory illness was graded from 1-3 as previously described[8]. In addition, a panel of 36 healthy volunteers (with characteristics described elsewhere[8]) free of comorbidities or influenza-like symptoms were recruited to the study and nasal and blood samples were obtained at a single time point.

Sample Collection

Nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) and flocked nasopharyngeal swabs were taken as soon as possible, generally within 72 hours of admission. Influenza virus infection status was assigned on the basis of results of influenza A/B RT-PCRs performed by laboratories serving the respective hospitals, with confirmation of these results by RT-PCR for influenza A, H1N1/2009 and influenza B at the West of Scotland Specialist Virology Centre. Antibody responses to A/Engl/195/2009(H1N1v) were detected by use of microneutralization assays according to standard methods as previously described[11] at the Centre for Infections, Health Protection Agency (London, UK). Serum samples were tested at an initial dilution of 1:10 and a final dilution of 1:5120.

All other samples were collected within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. Blood collection and NPA sampling was performed as previously described[8]. Nasosorption was used to sample mucosal lining fluid from the nose as detailed previously[12]. Additionally, whole blood was collected for microarray RNA profiling (Tempus blood RNA tube, Applied Biosystems/Ambion). Research samples were collected within 24 hours of admission and, where possible, at 48 hours and in convalescence (at least 4 weeks after presentation).

Sample Processing

Samples were processed using the ultrasensitive Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) platform (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, USA), based on electro-chemiluminescence quantitative patterned arrays to detect 28 cytokines and chemokines: IFN-α2α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IL-29, TNF-α, GMCSF, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL11, CCL13, CCL17, CCL22, CCL26, CXCL8, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11. Microarray gene expression profiling was performed using HT12 V4 BeadChip arrays (Illumina), containing >47,000 probes. Detailed methodology is available elsewhere[8].

Statistical Analyses

Clinical features comparing populations with and without asthma were analysed using a combination of two-sided Fisher’s exact test, chi-squared test, unpaired t-test and two-tailed Mann Whitney test as indicated in figure legends. Mediators were compared using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s test with Bonferroni multiple correction. Logistic regression analysis was carried out to identity independent predictors of severe outcome and to investigate association of asthma in relation to severe outcome. All analyses were performed with Prism version 7 (Graphpad, La Jolla, California) and R package software (Version 3.3.2)[13].

Results

Clinical Features

Forty of 133 (30.1%) hospitalized adults had asthma (Table 1). Amongst people with asthma, influenza A was responsible for 38/40 (95%) cases (all H1) with influenza B causing 2/40 (5%) of cases. In individuals without asthma, 82/93 (88.2%) of cases were caused by influenza A (H1=77; H3=3; suspected H1 based on serology=1; undetermined=1), 10/93 due to influenza B and 1 case with influenza A and B coinfection. Females were significantly overrepresented in those with asthma compared to those without (70% versus 38.7%, P=0.0012, OR 3.69, 95% CI 1.67 – 8.18). Patients with asthma had a lower mean length of stay (P=0.0333, 8.3 days SEM±2.55 versus 15.3 days SEM±1.82,) and were less likely to require intubation and ventilation at peak severity of disease (15% versus 37.6%, P=0.0338, X2 6.78). Relatively few patients with asthma died (5% versus 17.2%, P=0.0944), but were more likely to have received the seasonal influenza vaccine (37.5% versus 18.3%, P=0.0261) and inhaled corticosteroids (P<0.0001) prior to admission. Following admission, people with asthma were more likely to have received at least one dose of oral or i.v. corticosteroids during their inpatient stay (55% vs 25.8%, P=0.0016).

Table 1. Clinical features of hospitalized influenza participants with and without asthma.

| Clinical Feature | Asthma N (%) | No asthma N (%) | P value | OR / χ2 | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Participants | 40 (30%) | 93 (70%) | - | - | - |

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||

| Gender (Female) | 28 (70%) | 36 (38.7%) | 0.0012 | 3.69 | 1.67-8.18 |

| Age 18-30a | 11 (27.5%) | 26 (30.0%) | 0.9699 | 0.06 | NA |

| Age 31-45a | 14 (35%) | 32 (34.4%) | |||

| Age 46-60a | 11 (27.5%) | 23 (24.7%) | |||

| Age >60a | 4 (10%) | 12 (12.9%) | |||

| Whitea | 27 (67.5%) | 62 (66.7%) | 0.5810 | 1.96 | NA |

| Asian/Asian Britisha | 1 (2.5%) | 8 (8.6%) | |||

| Black/ Black Britisha | 8 (20%) | 14 (15.1%) | |||

| Chinesea | 4 (10%) | 9 (9.7%) | |||

| COMORBIDITIES & CO-FACTORS | |||||

| Any comorbidities other than asthma | 25 (62.5%) | 62 (66.7%) | 0.6930 | 0.83 | 0.71-1.24 |

| Chronic pulmonary conditions exc. asthma/COPD | 3 (7.5%) | 11 (11.8%) | 0.5519 | 0.60 | 0.16-2.30 |

| Chronic neurological disorders | 2 (5%) | 6 (6.5%) | 1.0000 | 0.76 | 0.15-3.96 |

| Chronic renal disease | 3 (7.5%) | 5 (5.4%) | 0.6965 | 1.43 | 0.32-6.28 |

| Chronic hepatic disease | 1 (2.5%) | 4 (4.3%) | 1.0000 | 0.57 | 0.06-5.27 |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 10 (25%) | 19 (20.4%) | 0.6478 | 1.30 | 0.54-3.12 |

| Diabetes | 5 (12.5%) | 9 (9.7%) | 0.7587 | 1.33 | 0.42-4.26 |

| Chronic obesity | 10 (25%) | 17 (18.3%) | 0.4809 | 1.49 | 0.61-3.62 |

| HIV positivity | 7 (17.5%) | 8 (8.6%) | 0.1466 | 2.25 | 0.76-6.71 |

| Immunodeficiency (excluding HIV) | 9 (22.5%) | 15 (16.1%) | 0.4615 | 1.51 | 0.60-3.81 |

| Current or active cancer | 3 (7.5%) | 19 (20.4%) | 0.0778 | 0.32 | 0.09-1.14 |

| Haematological disorder | 0 | 5 (5.4%) | 0.3217 | 0.20 | 0.01-3.68 |

| Current or ex-smoker | 17/34 (50%) | 37/69 (53.6%) | 0.8344 | 0.86 | 0.38-1.97 |

| Current Smoker | 13/34 (38.2%) | 22/69 (31.9%) | 0.5106 | 1.38 | 0.59-3.24 |

| Pregnancy (in women of child-bearing age) | 3/23 (13%) | 10/30 (33.3%) | 0.1151 | 0.30 | 0.07-1.26 |

| Seasonal Vaccine | 15 (37.5%) | 17 (18.3%) | 0.0261 | 2.68 | 1.17-6.14 |

| H1N1 Vaccine | 8 (20%) | 7 (7.5%) | 0.0684 | 3.07 | 1.03-9.16 |

| Pre-admission Inhaled corticosteroids | 16 (40%) | 6 (6.5%) | <0.0001 | 9.67 | 3.41-27.4 |

| ADMISSION | |||||

| Oral/i.v. corticosteroids on day 1 of admission | 15 (37.5%) | 13 (14%) | 0.0046 | 3.69 | 1.55-8.80 |

| In-hospital oral/i.v. corticosteroid use (≥ 1 dose) | 22 (55%) | 24 (25.8%) | 0.0016 | 3.51 | 1.62-7.29 |

| Admission ≤2 days after symptom onset | 15 (37.5%) | 32 (34.4%) | 0.8435 | 1.14 | 0.53-2.47 |

| Admission ≤4 days after symptom onset | 24 (60%) | 49 (52.7%) | 0.4547 | 1.35 | 0.63-2.86 |

| Days between onset of symptoms and admission Median (IQR)b | 3 (2-7) | 4 (2-8) | 0.3941 | - | - |

| O2 saturation on admission ≤92% | 6/33 (18.2%) | 23/71 (32.4%) | 0.2389 | 0.48 | 0.18-1.37 |

| Oxygen administered | 8/26 (30.1%) | 28/63 (44.4%) | 0.3423 | 0.56 | 0.21-1.47 |

| Pneumonia on CXR | 3/20 (15%) | 14/47 (29.8%) | 0.2382 | 0.42 | 0.11-1.65 |

| Antibiotic use at admission | 28/33 (84.8%) | 69/73 (94.5%) | 0.1329 | 0.33 | 0.08-1.30 |

| Peak Respiratory Score 1a | 15 (37.5%) | 27 (29.0%) | 0.0338 | 6.78 | NA |

| Peak Respiratory Score 2a | 19 (47.5%) | 31 (33.3%) | |||

| Peak Respiratory Score 3a | 6 (15%) | 35 (37.6%) | |||

| Length of stay (days, mean ±SEM)c | 8.3 ±2.55 | 15.3 ±1.82 | 0.0333 | - | - |

| Influenza A positivea | 38 (95%) | 82 (88.2%) | 0.4492 | 1.60 | - |

| Influenza B positivea | 2 (5%) | 10 (10.8%) | |||

| Influenza A+B co-infectiona | 0 | 1 (1.1%) | |||

| Influenza H1 positivea | 38/38 (100%) | 77/82 (94.0%) | 0.4903 | 2.42 | - |

| Influenza H3 positivea | 0 | 3/82 (3.7%) | |||

| Undetermineda | 0 | 1/82 (1.2%) | |||

| Suspected influenza H1 based on serologya | 0 | 1/82 (1.2%) | |||

| Rhinovirus positive | 1/36 (2.8%) | 9/83 (10.84%) | 0.2788 | 0.23 | 0.03-1.93 |

| Pre-hospital anti-viral use | 2/33 (6%) | 1/77 (1.3%) | 0.2137 | 4.90 | 0.43-56.1 |

| In-hospital antiviral use (≥ 1 dose) | 37/39 (94.9%) | 85/89 (95.5%) | 0.9999 | 0.87 | 0.20-4.74 |

| Antiviral use ≤48 hours from onset of symptoms | 14/39 (35.9%) | 26/89 (29.2%) | 0.5351 | 1.36 | 0.62-3.05 |

| Antiviral use on day 1 of admission | 28/35 (80%) | 62/73 (84.9%) | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.27-1.87 |

| Positive for any bacteria 0-4 days post onset of symptoms (PCR or culture) | 10 (25%) | 20/92 (21.7%) | 0.6595 | 1.20 | 0.50-2.87 |

| Positive for any bacteria 5-10 days post onset of symptoms (PCR or culture) | 11 (27.5%) | 25/92 (27.2%) | 1.000 | 1.02 | 0.44-2.34 |

| Positive for any bacteria 11+ days post onset of symptoms (PCR or culture) | 13 (32.5%) | 19/92 (20.7%) | 0.1849 | 1.85 | 0.80-4.25 |

| Death | 2 (5%) | 16 (17.2%) | 0.0944 | 0.25 | 0.06-1.16 |

All statistical analyses done using Fisher’s exact test unless indicated otherwise.

chi-squared test

Mann-Whitney test

unpaired t-test

SEM=standard error of mean. 6 patients without asthma on pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids had comorbidities including COPD (n=4) and chronic lung disease (n=2). Note where there is incomplete data about medication and comorbidities available from medical records, a denominator value is shown.

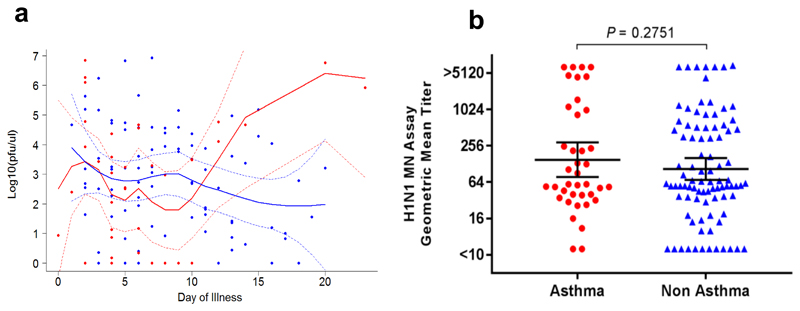

To determine predictors of a severe outcome (invasive ventilation or death), multiple regression modelling identified presentation to hospital >4 days after symptom onset and administration of in-hospital systemic steroids as factors associated with a worse outcome (Table E1). When patients with and without a severe outcome were assessed separately, presentation to hospital >4 days after symptom onset (P=0.0002, OR 5.49, 95% CI 2.28 – 14.03) and administration of in-hospital systemic corticosteroids (P=0.0466, OR = 2.6250, 95% CI = 1.02 –6.96) remained associated with a severe outcome in people without asthma, but not in those with asthma (data not shown). There was no significant difference between individuals with and without asthma in nasopharyngeal influenza viral load within 24 hours of admission and kinetics based on day of sampling after self-reported onset of influenza-symptoms (Fig. 1a). There was also no difference in H1N1 geometric mean titres as measured by microneutralization assay (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Nasopharangeal influenza viral load and serological response to H1N1 in subjects with and without asthma.

(a) Viral load kinetics based on number of days elapsed between subject-reported symptom onset and time of sampling. Dots represent individual samples with up to 2 samples collected per subject; red dots represent asthma (n=37), blue dots represent no asthma (n=88). First sample collected within 24 hours of admission and second sample between 48-72 hours of admission to a MOSAIC hospital. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) fits plotted in red for asthma samples and blue for non-asthma samples. Solid line represent LOESS fit and dashed lines 95% CI (b) H1N1 geometric mean titre as measured by microneutralization assay. Horizontal line represents the geometric mean and error bars the 95% CI. Statistical analysis performed using unpaired t-test.

Systemic and Mucosal Immune Response

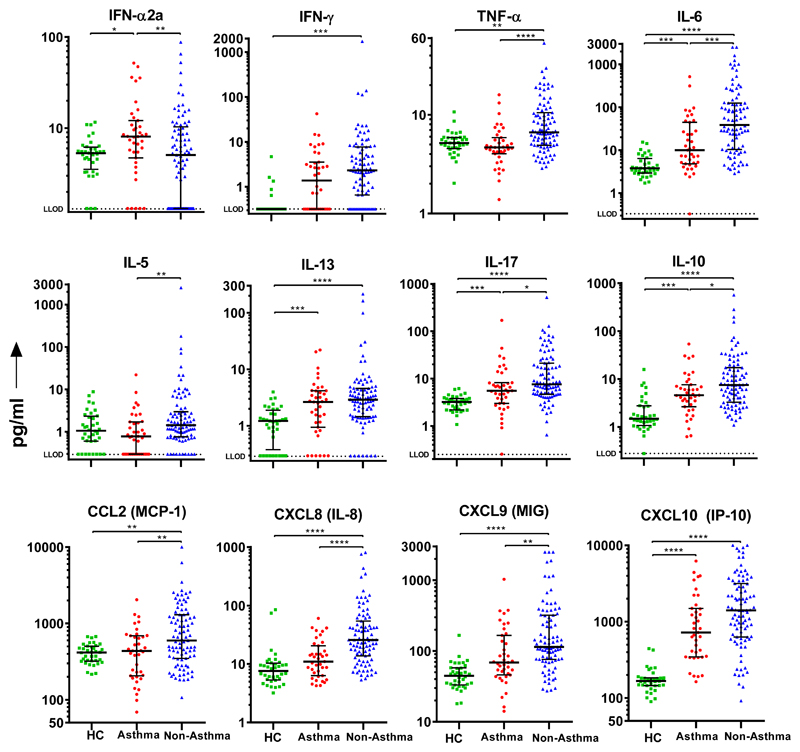

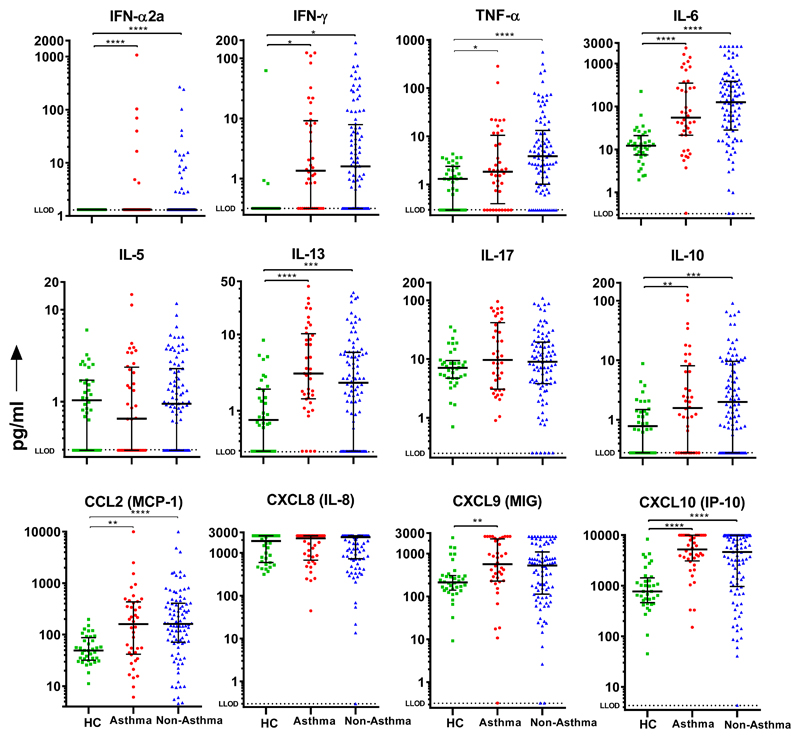

All hospitalized patients with influenza had equivalent or greater systemic and mucosal inflammation relative to non-hospitalized healthy controls (Fig. 2 and 3, Fig E1 and Tables E2–E4). During the first 24 hours of hospital admission, people with asthma had reduced systemic inflammation compared to those without as demonstrated by significantly lower serum levels of TNF-α (P<0.0001), IL-6 (P=0.0005), CXCL8 (P<0.0001), CXCL9 (P=0.0031), IL-10 (P=0.0411), IL-17 (P=0.0197) and CCL2 (P=0.0038); However, individuals with asthma had significantly higher levels of serum IFN-α2a (P=0.0099; Fig. 1 and Table E2). Interestingly, those with asthma had lower levels of serum IL-5 (P=0.0010) but comparable levels of IL-13 (P=0.3131).

Figure 2. Serum mediators measured within 24 hours of admission to hospital in individuals with and without asthma.

Dots represent individual patients (HC=36, asthma=39, no asthma=91) and error bars the median and interquartile range. Statistical analysis performed using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunns test with Bonferroni multiple correction; *P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P <0.001; **** P <0.0001. Abbreviations: HC=Healthy Control; LLOD = Lower limit of detection.

Figure 3. Nasal mediators measured within 24 hours of admission to hospital in individuals with and without asthma.

Dots represent individual patients (HC=36, asthma=40, no asthma=92) and error bars the median and interquartile range. Statistical analysis performed using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunns test with Bonferroni multiple correction. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P <0.0001. Abbreviations: HC=Healthy Control; LLOD = Lower limit of detection.

There were no significant differences in 28 nasal or nasopharyngeal cytokine and chemokine levels measured within 24 hours of admission between individuals with and without asthma (Fig. 2, Tables E3 and E4). In particular, there was comparable mucosal induction of anti-viral mediators IFN-α2a, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IFN-λ and CXCL10 as well as the type 2 mediators IL-5 and IL-13.

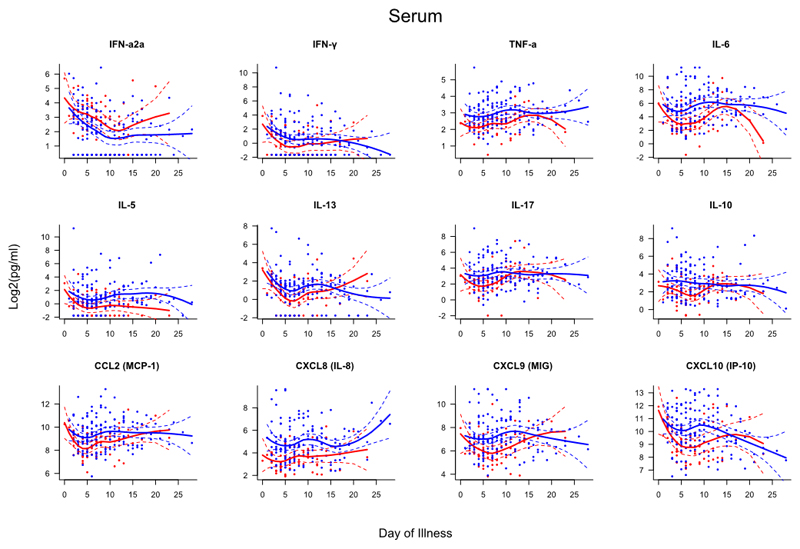

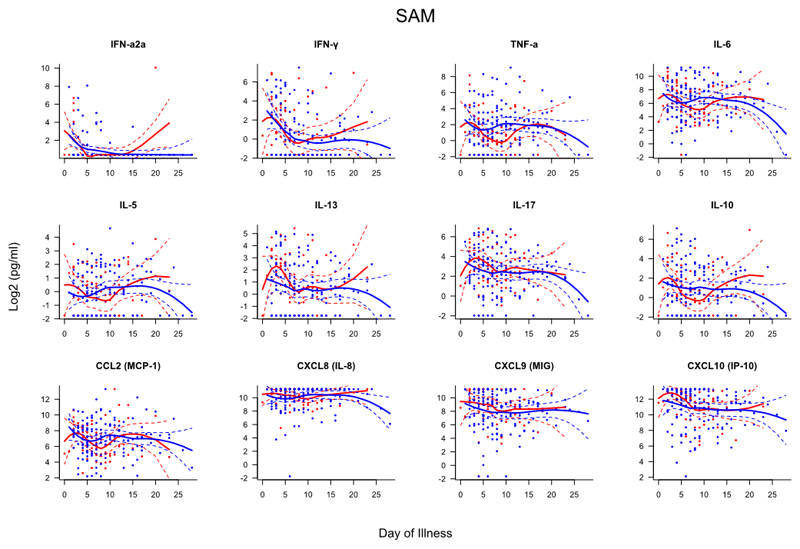

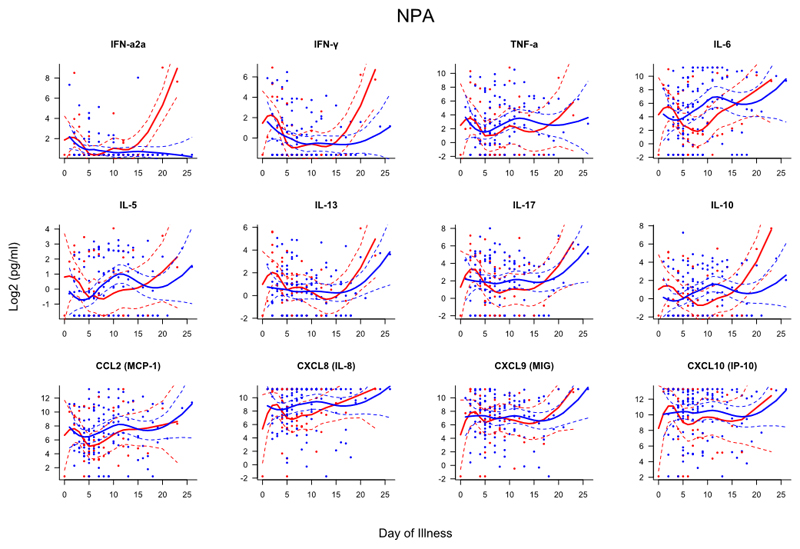

Samples from subjects were collected within 24 hours and again at 48-72 after admission (if possible). To compare the kinetics of the host immune response to infection between patients with and without asthma, mediator levels were assessed based on day of illness (DOI), i.e. the interval between subject-reported onset of influenza-like symptoms and date of sampling (Figs. E2–4). This analysis showed that those without asthma had evidence of greater systemic inflammation with significantly higher serum levels of TNF-α (days 3-12), IL-6 (days 4-11), IL-5 (days 11-19), IL-17 (days 4-7), IL-10 (days 4-8), CCL2 (days 3-5), CXCL8 (days 2-13), CXCL9 (days 5-12) and CXL10 (days 5-11). In the nasal mucosa, people without asthma had higher TNF-α levels (days 8-10) whilst all other mediators demonstrated similar kinetics.

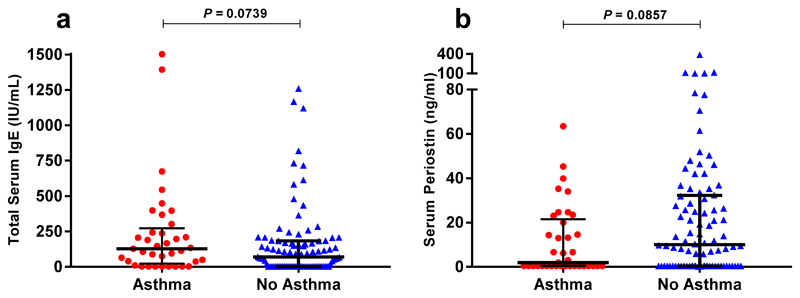

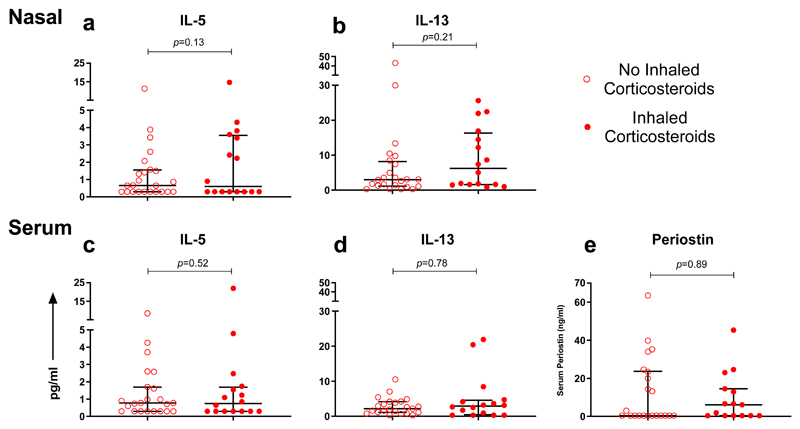

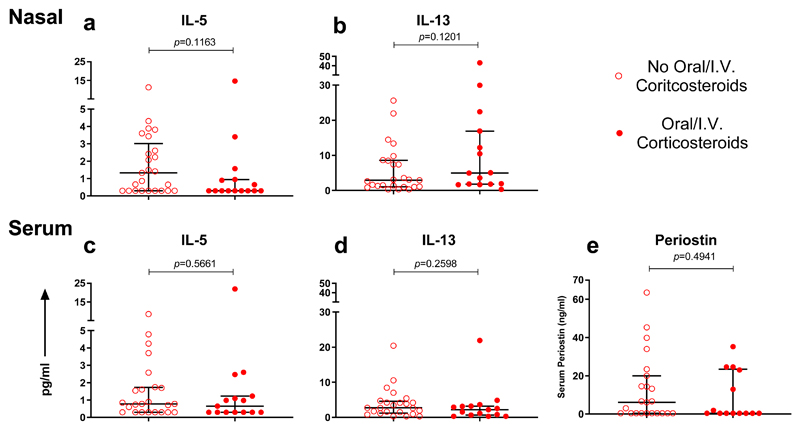

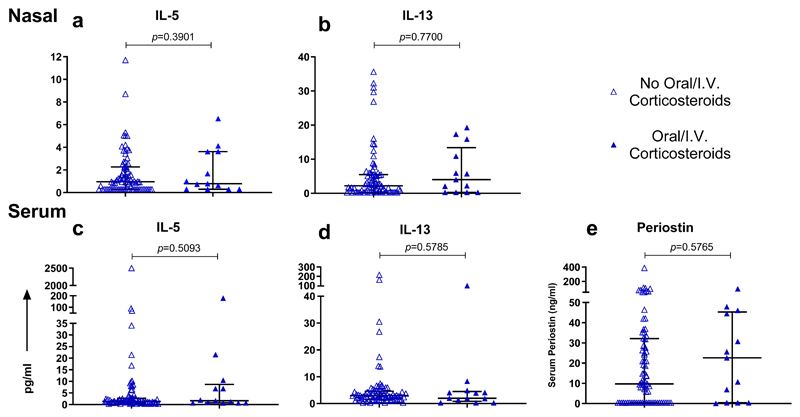

Total IgE (a marker of atopy) and periostin (a marker of IL-4/13 activation) were measured in serum, with no significant differences seen between those with and without asthma (Fig. 4). The use of pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids in patients with asthma (Fig. 5), and administration of systemic corticosteroids within the first 24 hours of admission in those with and without asthma (Figs. 6 and 7), did not significantly affect serum or nasal mucosal levels of IL-5, IL-13 or periostin.

Figure 4. Serum levels of Total IgE and periostin in subjects with and without asthma.

(a) Total serum IgE and (b) serum periostin levels measured within 24 hours of admission in individual subjects, asthma (n=37), no asthma (n=92). Horizontal bar represents the median and error bars the interquartile range. Statistical analysis performed using Mann-Whitney test.

Figure 5. Type 2 inflammatory response in subjects with asthma based on presence or absence of pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids.

(a) Nasal IL-5 and (b) nasal IL-13 levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids (n=16), subjects not on pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids (n=24). (c) Serum IL-5 and (d) serum IL-13 levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids (n=16), subjects not on pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids (n=23). (e) Serum periostin levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids (n=15), subjects not on pre-admission inhaled corticosteroids (n=22). Horizontal bar represents the median and error bars the interquartile range. Statistical comparison performed using Mann-Whitney test.

Figure 6. Type 2 inflammatory response in subjects with asthma based on administration of oral/I.V. corticosteroids within 24 hours of admission.

(a) Nasal IL-5 and (b) nasal IL-13 levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=15), subjects not on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=25). (c) Serum IL-5 and (d) serum IL-13 levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=15), subjects not on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=24). (e) Serum periostin levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=14), subjects not oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=23). Horizontal bar represents the median and error bars the interquartile range. Statistical comparison performed using Mann-Whitney test.

Figure 7. Type 2 inflammatory response in subjects without asthma based on administration of oral/I.V. corticosteroids within 24 hours of admission.

Nasal IL-5 and (b) nasal IL-13 levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=13), subjects not on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=79). (c) Serum IL-5 and (d) serum IL-13 levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=13), subjects not on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=78). (e) Serum periostin levels measured within 24 hours of admission; subjects on oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=13), subjects not oral/I.V. corticosteroids (n=77). Horizontal bar represents the median and error bars the interquartile range. Statistical comparison performed using Mann-Whitney test

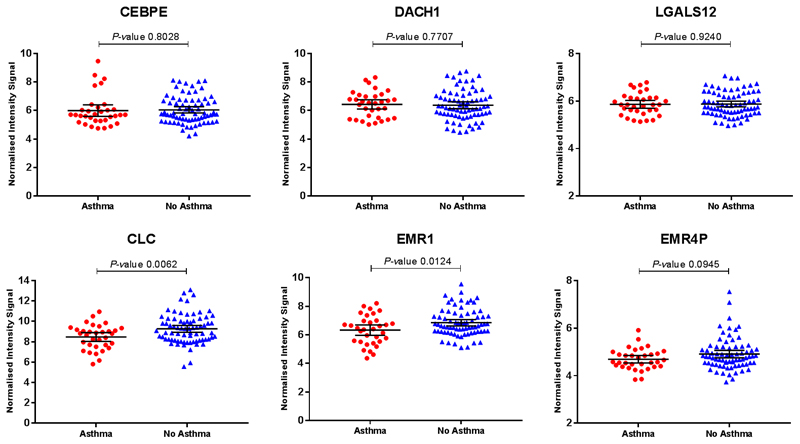

In whole blood RNA, there were no differentially expressed genes (DEG) found between individuals with and without asthma after correction for multiple testing (data not depicted). Blood eosinophil counts were unavailable, but gene transcripts that serve as markers of eosinophilia (CLC, CEBPE, DACH1, EMR1, EMR4P and LGALS12[12]) were measured. CEBPE, DACH1 and LGALS12 were not significantly different between groups whilst CLC, EMR1 and EMR4P were higher in people without asthma, indicating that those with asthma in this study were unlikely to have raised eosinophil levels (Fig. E5).

Discussion

In this study, asthma was the major identifiable predisposing condition in patients hospitalized with influenza. Influenza cases with asthma tended to be female (70%), have a shorter period of hospitalization and a reduced requirement for invasive ventilation than those without asthma. Extensive monitoring of mucosal and systemic inflammation over time showed relatively low levels of systemic inflammation but equal mucosal inflammation in subjects with asthma, compared to those without.

The sex bias noted in this study is reflected in a larger UK based cohort in which 61% of asthma patients were female, compared to only 39% of those without asthma[1] (personal communication, Puja Miles, Nottingham). It is well described that middle-aged women have a propensity to present with non-atopic asthma[14], highlighting that non-allergic triggers (such as infection) are likely to be key determinants of asthma exacerbations in this subgroup. A range of subtypes of asthma have been extensively characterized[15]. Many individuals with asthma have increased type 2 inflammation associated with mast cell and eosinophil infiltration of the airways[16]. Such patients with allergic asthma typically have elevated plasma IL-5 and IL-13, identifying them as suitable for biologic therapies that target these cytokines[17, 18]. In addition, IL-5 and IL-13 are elevated in nasosorption samples from individuals with allergic asthma (even when stable before exacerbation) compared with healthy non-atopic controls[19], as well as nasal periostin, IgE and IL-13 in severe asthma[20]. In this study, there was a remarkable lack of elevation in serum or nasal type 2 mediators (IL-5 and IL-13) and no significant rise in total serum IgE, periostin and blood eosinophil-specific gene expression in individuals with asthma relative to those without asthma. These findings suggest that individuals with asthma who are at risk of severe influenza are of a specific disease endotype: females with minimal type 2 inflammation and non-atopic features. This endophenotype is sometimes described as ‘intrinsic’ asthma (a classification ascribed to Francis M. Rackemann[21]), who noted that intrinsic asthma generally affects older individuals with frequent virally-induced exacerbations[22].

Serosurveys show that the first wave of the 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 infected one in three children in the UK[11], only a small minority suffering severe disease. The role of type 2 cytokines in the pathogenesis of influenza remains unclear. Although T-helper 2 cells (Th2) are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13[23], other cells may also contribute. For example, infection of airway epithelial cells can induce the secretion of epithelial-derived cytokines such as IL-25, Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and IL-33, which interact with innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) to induce the release of type-2 cytokines[24, 25]. TSLP induces Type 2 cytokine production even in naive CD4+ cells and indirectly affects dendritic cell (DC) function; it may have protective anti-viral effects in mice[26]. Influenza infection can enhance production of alveolar macrophage derived IL-33, resulting in increased IL-13 release by ILCs and airway hyperreactivity in mice[27]7. IL-33 may also have an important role in epithelial injury repair after influenza infection[28][29].

Interferon deficiency has been described in cultured cells from asthma volunteers following ex-vivo HRV infection[30–32], whereas robust IFN-γ and IFN-λ responses have been found in-vivo during exacerbations in children with asthma[33, 34]. A recent study of the effects of fluticasone on bronchial biopsy explants from patients with and without asthma infected ex vivo with influenza did not demonstrate any difference in epithelial cell infection rates between groups. Whilst there was a reduction in the secretion of innate immune mediators (including IFN-γ, CXCL10, MCP-1 and IL-6), type-1 IFNs were undetectable[35]. Our current study had the advantages of in vivo direct sampling of the blood and airway mucosa, showing increased serum levels of IFN-α2a in patients with asthma but comparable levels of interferons (α, β, γ, λ) and related chemokines (CXCL10 and CXCL11) in mucosal fluids.

We found that the use of in-hospital systemic corticosteroids was associated with poor outcome in those without asthma, but not in those with asthma. A meta-analysis of unselected patients with influenza-related complications found that systemic corticosteroid use is associated with worse outcomes[36]. More recently, a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial in primary care confirmed the lack of any beneficial effect of oral corticosteroids for acute lower respiratory tract symptoms in patients without asthma[37]. We found that the use of in-hospital systemic corticosteroids was associated with poor outcome in those without asthma, but not in those with asthma. However, the fact that corticosteroid use is more prevalent in patients who have increased influenza-related complications may have contributed to this association.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that presentation to hospital ≥4 days after symptom onset was associated with worse outcome amongst patients without asthma. Individuals with asthma have an abnormal respiratory epithelium with airway hyperreactivity (AHR) and may present to hospital primarily due to enhanced mucosal responses and bronchospasm. We speculate that the increased number of asthma patients being hospitalized with exacerbations may partly be due to early onset of respiratory symptoms caused by inflammation in the conducting airways. By contrast, people without asthma may present with respiratory failure caused by inflammation in the distal gas-exchanging parts of the lung.

A slower decline in viral load has been associated with increased severity of influenza infection and immunodysregulation[38]. We found that viral load measured within 24 hours of admission, subsequent clearance of virus, or serological responses to H1N1 was not significantly different between patients with and without asthma. This is consistent with our conclusions that different systemic immune responses between clinical groups are not due to an inability to control viral replication, but rather to differences in host response. Antiviral medication (oseltamivir and zanamivir) is recommended for those with risk factors for influenza complications, including asthma[39]. Antivirals were very rarely given prior to hospital admission in our patients (asthma n=2, non-asthma n=1), so cannot explain differences in immune responses measured on admission. They were not administered in 20% of asthma patients in the first 24 hours of admission for whom prescribing data was available, but most did receive at least one dose during the course of their admission. Other studies show that administration of antivirals early during illness and prior to admission significantly reduces hospital admission rates[40], and that antivirals within 48 hours of symptom onset reduces mortality in hospitalized patients[41]. Our study found that 14/39 (35.9%) asthma patients and 26/89 (29.2%) patients without asthma received antivirals within 48 hours of symptom onset. This may have been due to patients presenting later in their illness or a lack of awareness or resources available in primary care. Whilst more individuals with asthma received the seasonal influenza vaccine compared to those without asthma, vaccination rates were low compared to national norms. Immunization with H1N1 vaccine was especially rare, but it is notable that some of our cases did appear to have been appropriately vaccinated and yet developed severe influenza.

Our study has important limitations. It was designed to investigate all patients admitted with influenza rather than to address the issue of the effects of pre-existing asthma on the course of influenza. Asthma diagnosis was based on a review of clinical notes and patient-reported diagnosis of asthma and we lack spirometric data or information about baseline severity and nature of symptoms (e.g. persistent vs. intermittent asthma). We do not have blood eosinophil counts, exhaled breath nitric oxide or sputum cell counts. Only 40% of asthma patients were on inhaled corticosteroids. However, national guidance at the time of recruitment did not require its use in those with mild asthma[42]. Additionally, clinical studies recruiting those with confirmed asthma commonly have only half of participants taking inhaled corticosteroids[19]. In future studies, prospective endophenotyping of asthma patients, coupled with the measurement of mucosal and systemic immune parameters might further enhance understanding of mechanisms of disease during viral exacerbations[43]. Large cohort studies with well-characterized subjects such as the Severe Asthma Research Programme (SARP)[44] and Unbiased BIOmarkers in PREDiction of respiratory disease outcomes (U-BIOPRED)[45] have the potential to identify how underlying endophenotypes influence susceptibility to infection and predict treatment response.

In summary, our study suggests that patients with asthma hospitalized with influenza are predominantly female and have a good prognosis, with reduced systemic inflammation but comparable mucosal responses to individuals without asthma. Notably, serum total IgE levels and nasal IL-5 and IL-13 levels were not statistically different between patients with and without asthma. Our study highlights the value of assessing the airway mucosal and systemic host immune response to influenza, suggesting investigation of prospective targeted therapeutic and preventative strategies in well-characterized asthma patients with intrinsic disease.

Study Approval

The study was approved by the NHS National Research Ethics Service, Outer West London REC (09/H0709/52, 09/MRE00/67) and is registered on https://clinicaltrials.gov with trial number NCT00965354. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or their legally authorised representatives as well as healthy controls.

Extended Data

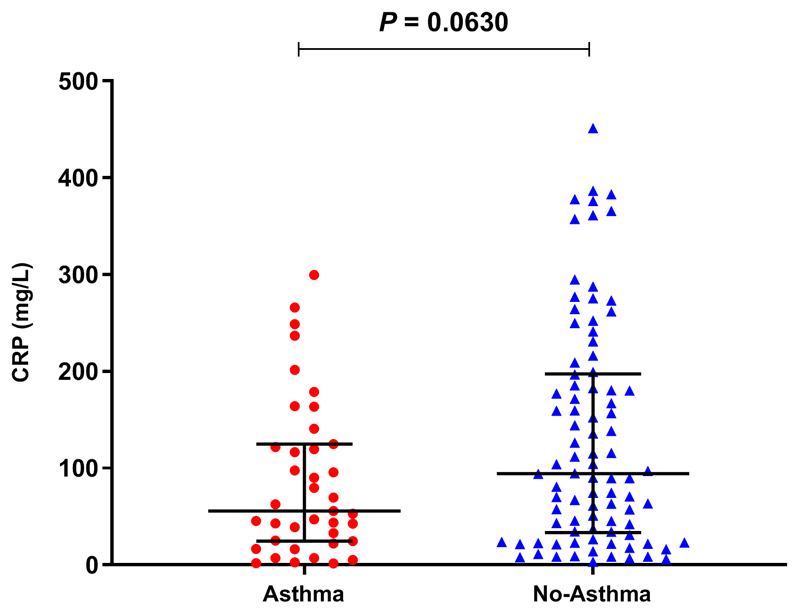

Figure E1. Serum levels of CRP in subjects with and without asthma.

Measured within 24 hours of admission in individual subjects, asthma (n=39), no asthma (n=90). Horizontal bar represents the median and error bars the interquartile range. Statistical analysis performed using Mann-Whitney test.

Figure E2. Scatterplots of serum mediators differentiated by day of illness (DOI).

Dots represent individual samples up to two samples collected per subject. Red dots represent asthma (n=64), blue dots represent no asthma (n=155). First sample collected within 24 hours of admission and second sample between 48-72 hours of admission. DOI represents number of days elapsed between subject-reported symptom onset and time of sampling. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) fits plotted in red for asthma samples and blue for non-asthma samples. Solid line represent LOESS fit and dashed lines the 95% CI.

Figure E3. Scatterplots of nasal mediators differentiated by day of illness (DOI).

Dots represent individual samples with up to two samples collected per subject. Red dots represent asthma (n=65), blue dots represent no asthma (n=153). First sample collected within 24 hours of admission and second sample between 48-72 hours of admission. DOI represents number of days elapsed between subject-reported symptom onset and time of sampling. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) fits plotted in red for asthma samples and blue for non-asthma samples. Solid line represent LOESS fit and dashed lines the 95% CI

Figure E4. Scatterplots of nasopharyngeal mediators differentiated by day of illness (DOI).

Dots represent individual samples up to two samples collected per subject. Red dots represent asthma (n=49), blue dots represent no asthma (n=123). First sample collected within 24 hours of admission and second sample between 48-72 hours of admission. Day of illness represents number of days elapsed between subject-reported symptom onset and time of sampling. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) fits plotted in red for asthma samples and blue for non-asthma samples. Solid line represent LOESS fit and dashed lines the 95% CI

Figure E5. Expression of eosinophil associated genes in subjects with and without asthma.

Whole blood samples were collected within 24 hours of admission for gene expression. RNA was extracted and analysed using Illumina microarray and the data normalized. Dots represent individual patients (asthma=33, no asthma=74) with horizontal bar representing the mean and error bars the 95% CI. Statistical analysis performed using unpaired t-test

Tabel E1. Multivariate logistic regression model of covariates associated with severe outcome.

| Outcome: Death or respiratory failure requiring invasive ventilation | P-value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma Present | 0.0521 | 0.2947 | 0.0790 - 0.9537 |

| Gender (female as reference) | 0.2862 | 1.6550 | 0.6611 - 4.2674 |

| Age (18-30 years as reference) | |||

| Age 31-40 | 0.8939 | 1.0944 | 0.2847 - 4.1500 |

| Age 41-50 | 0.6043 | 1.3669 | 0.4215 - 4.5728 |

| Age >50 | 0.0818 | 3.1190 | 0.8890 - 11.7696 |

| Admission >4 days | 0.0001 | 5.9084 | 2.4540 - 15.4449 |

| Seasonal flu vaccination | 0.1342 | 0.4002 | 0.1120 - 1.2664 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid use | 0.2068 | 0.3573 | 0.0621 - 1.6321 |

| Oral/I.V. corticosteroids | 0.0154 | 3.4629 | 1.3036 - 9.9038 |

n=133

Table E2. Serum cytokines and chemokines measured within 24 hours of admission.

| Cytokine or chemokine | Median HC |

Median A |

Median NA |

Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction; P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| (n=36) | (n=40) | (n=93) | A vs NA | A vs HC | NA vs HC | |

| IFN-α2α | 5.31 | 8.08 | 5.07 | 0.0099 | 0.0452 | 1.000 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-β | 11.67 | 11.67 | 11.67 | 1.000 | 0.0042 | 0.0021 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-γ | 0.32 | 1.38 | 2.32 | 0.1256 | 0.0806 | 0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN –λ/IL-29 | 26.84 | 12.01 | 12.01 | 1.0000 | 0.3816 | 0.1327 |

|

| ||||||

| TNF-α | 5.17 | 4.67 | 6.64 | 0.0000 | 0.5235 | 0.0015 |

|

| ||||||

| GMCSF | 1.06 | 0.29 | 0.76 | 0.4591 | 0.8004 | 1.0000 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| IL-1β | 0.78 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.2631 | 1.0000 | 0.3032 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-2 | 4.70 | 5.09 | 6.23 | 0.0906 | 1.0000 | 0.2109 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-4 | 1.66 | 0.90 | 1.02 | 1.0000 | 0.0038 | 0.0011 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-5 | 1.06 | 0.77 | 1.42 | 0.0010 | 0.2020 | 0.1791 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-6 | 3.78 | 9.98 | 38.81 | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-10 | 1.48 | 4.59 | 7.49 | 0.0411 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-12p70 | 3.99 | 1.75 | 1.98 | 0.8897 | 0.0145 | 0.0177 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-13 | 1.22 | 2.64 | 2.91 | 0.3131 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-15 | 1.63 | 3.71 | 4.81 | 0.1809 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-17 | 3.20 | 5.56 | 7.58 | 0.0197 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| CCL2/ MCP-1 | 415.82 | 435.19 | 595.56 | 0.0038 | 1.0000 | 0.0027 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL3/ MIP-1α | 10.99 | 13.49 | 13.69 | 1.0000 | 0.0725 | 0.0166 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL4/ MIP-1β | 165.28 | 125.66 | 133.52 | 0.7915 | 0.0179 | 0.0291 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL11/ Eotaxin | 1250.70 | 547.81 | 621.48 | 1.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL13/ MCP-4 | 640.96 | 357.80 | 394.07 | 0.8654 | 0.0017 | 0.0016 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL17/ TARC | 412.83 | 263.25 | 240.04 | 1.0000 | 0.0020 | 0.0007 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL22/ MDC | 4010.90 | 1381.39 | 1739.56 | 0.5969 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL26/ Eotaxin-3 | 2.51 | 15.75 | 18.36 | 0.8089 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL8/ IL-8 | 7.61 | 10.99 | 25.78 | 0.0000 | 0.0643 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL9/ MIG | 44.64 | 68.72 | 114.22 | 0.0031 | 0.0016 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL10/ IP-10 | 167.09 | 721.01 | 1409.26 | 0.0546 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL11/ ITAC | 60.98 | 187.57 | 277.71 | 0.2949 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

HC=Healthy control; A=Asthma; NA=No Asthma

Table E3. Nasal cytokines and chemokines measured within 24 hours of admission.

| Cytokine or chemokine |

Median HC |

Median A |

Median NA |

Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction; P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| (n=36) | (n=40) | (n=93) | A vs NA | A vs HC | NA vs HC | |

| IFN-α2a | 1.31 | 1.31 | 1.31 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-β | 66.05 | 41.02 | 49.52 | 0.7356 | 0.0604 | 0.1247 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-γ | 0.32 | 1.36 | 1.60 | 1.0000 | 0.0496 | 0.0495 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-λ (IL-29) | 12.01 | 12.01 | 12.01 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| TNF-α | 1.31 | 1.83 | 3.86 | 0.0674 | 0.0312 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| GMCSF | 1.17 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 0.7172 | 0.1926 | 0.0208 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| IL-1β | 31.11 | 28.03 | 25.36 | 1.0000 | 0.9505 | 1.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-2 | 1.93 | 2.47 | 3.49 | 0.7123 | 1.0000 | 0.8696 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-4 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.2432 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-5 | 1.04 | 0.65 | 0.95 | 0.7025 | 0.2192 | 0.4762 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-6 | 12.26 | 54.78 | 125.68 | 0.4013 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-10 | 0.78 | 1.58 | 1.99 | 1.0000 | 0.0041 | 0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-12p70 | 1.51 | 1.12 | 1.45 | 0.3472 | 0.3515 | 1.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-13 | 0.76 | 3.09 | 2.33 | 0.1510 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-15 | 1.17 | 2.26 | 1.94 | 0.6601 | 0.0103 | 0.0235 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-17 | 7.06 | 9.67 | 9.01 | 0.5367 | 0.2055 | 0.5915 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| CCL2/ MCP-1 | 49.16 | 160.36 | 161.93 | 0.7861 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL3/ MIP-1α | 8.65 | 28.61 | 29.41 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL4/ MIP-1β | 23.33 | 92.86 | 135.37 | 0.6431 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL11/ Eotaxin | 138.53 | 253.14 | 229.45 | 0.3149 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL13/ MCP-4 | 12.35 | 13.00 | 12.88 | 1.0000 | 0.4939 | 0.3527 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL17/ TARC | 4.96 | 17.67 | 14.37 | 0.3462 | 0.0543 | 0.2938 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL22/ MDC | 115.93 | 157.02 | 158.61 | 1.0000 | 0.3130 | 0.1788 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL26/ Eotaxin-3 | 30.91 | 44.17 | 38.45 | 1.0000 | 0.4245 | 0.2513 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL8/ IL-8 | 1880.12 | 2177.42 | 2326.43 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL9/ MIG | 212.28 | 561.13 | 525.16 | 0.1771 | 0.0037 | 0.0625 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL10/ IP-10 | 773.80 | 5215.96 | 4619.65 | 0.2013 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL11/ ITAC | 11.65 | 126.69 | 64.50 | 0.1026 | 0.0000 | 0.0010 |

HC=Healthy control; A=Asthma; NA=No Asthma

Table E4. Nasopharyngeal cytokines and chemokines measured within 24 hours of admission.

| Cytokine or chemokine | Median HC |

Median A |

Median NA |

Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction; P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| (n=36) | (n=40) | (n=93) | A vs NA | A vs HC | NA vs HC | |

| IFN-α2a | 1.31 | 1.31 | 1.31 | 0.2611 | 0.0016 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-β | 11.67 | 11.67 | 11.67 | 1.0000 | 0.0394 | 0.0386 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-γ | 0.32 | 1.05 | 0.32 | 0.2193 | 0.6190 | 0.8937 |

|

| ||||||

| IFN-λ (IL-29) | 12.01 | 12.01 | 12.01 | 0.5483 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| TNF-α | 0.30 | 7.90 | 7.11 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| GMCSF | 0.29 | 2.01 | 2.42 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| IL-1β | 0.33 | 4.76 | 3.21 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-2 | 0.58 | 5.27 | 10.08 | 0.6876 | 0.0088 | 0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-4 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 1.23 | 0.7800 | 1.0000 | 0.9828 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-5 | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 1.0000 | 0.6427 | 0.6659 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-6 | 0.33 | 10.55 | 34.27 | 0.9277 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-10 | 0.28 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-12p70 | 0.29 | 1.39 | 1.13 | 1.0000 | 0.2038 | 0.0796 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-13 | 0.78 | 2.78 | 1.76 | 0.2548 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-15 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| IL-17 | 0.25 | 9.09 | 5.20 | 0.5273 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| CCL2/ MCP-1 | 1.70 | 66.62 | 123.56 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL3/ MIP-1α | 1.37 | 28.04 | 26.42 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL4/ MIP-1β | 5.25 | 279.03 | 135.08 | 0.8527 | 0.0076 | 0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL11/ Eotaxin | 14.98 | 850.31 | 536.97 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL13/ MCP-4 | 2.94 | 38.24 | 38.26 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL17/ TARC | 4.96 | 47.84 | 29.73 | 0.5485 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL22/ MDC | 54.39 | 435.31 | 375.91 | 0.8612 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CCL26/ Eotaxin-3 | 2.51 | 26.86 | 17.95 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL8/ IL-8 | 10.40 | 2173.69 | 888.60 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL9/ MIG | 2.52 | 360.53 | 216.47 | 0.9507 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL10/ IP-10 | 11.98 | 9004.99 | 3389.03 | 0.7205 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| CXCL11/ ITAC | 0.81 | 134.15 | 135.70 | 0.7444 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

HC=Healthy control; A=Asthma; NA=No Asthma

Take Home Message.

Patients with asthma hospitalised with influenza are commonly female with ‘intrinsic’ asthma lacking classical type 2 nasal mucosal inflammation. Compared to others hospitalised with influenza, they have a good prognosis and reduced systemic inflammation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the MOSAIC administrative team (Mary Cross, Lindsey-Anne Cumming, Matthew Minns, Tom Ford, Barbara Cerutti, Denise Gardner and Zoe Williams) and thank the patients and their families, healthy volunteers, and staff at participating National Health Service (NHS) hospitals (Alder Hey Children’s Hospital; Brighton & Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust; Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust; Liverpool Women's NHS Foundation Trust; Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust; Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust; University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust).

MOSAIC Investigators: Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust: B.G. Gazzard. Francis Crick Institute, Mill Hill Laboratory: A. Hay, J. McCauley, A. O’Garra. Imperial College London, UK: P. Aylin, D. Ashby, W.S. Barclay, S.J. Brett, W.O. Cookson, M.J. Cox, J. Dunning, L.N. Drumright, R.A. Elderfield, L. Garcia-Alvarez, M.J. Griffiths, M.S. Habibi, T.T. Hansel, J.A. Herberg, A.H. Holmes, S.L. Johnston, O.M. Kon, M. Levin, M.F. Moffatt, S. Nadel, P.J. Openshaw, J.O. Warner. Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK: S.J. Aston, S.B. Gordon. Manchester Collaborative Centre for Inflammation Research (MCCIR): T. Hussell. Public Health England (formerly Health Protection Agency), UK: J. Dunning, C. Thompson, M.C. Zambon. The Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh: D.A. Hume. University College London, UK: A. Hayward. UCL Institute of Child Health: R.L. Smyth; University of Edinburgh, UK: J.K. Baillie, P. Simmonds University of Liverpool, UK: P.S. McNamara; M.G. Semple; University of Nottingham, UK: J.S. Nguyen-Van-Tam; University of Oxford, UK: L-P. Ho, A. J. McMichael Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK: P. Kellam West of Scotland Specialist Virology Centre, Glasgow, UK: W.E. Adamson, W.F. Carman.

Funding

MOSAIC (Mechanisms of Severe Influenza Consortium) was supported by the MRC (UK) and Wellcome Trust (090382/Z/09/Z). The study was also supported by the National Institute of Healthcare Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centres (BRCs) in London and Liverpool and by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Respiratory Infections at Imperial College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE). P.J.O. was supported by EU FP7 PREPARE project 602525. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health, Public Health England or the EU. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AHR

Airway Hyperreactivity

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CPAP

Continuous Positive Airways Pressure

- DOI

Day of Illness

- ECMO

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

- ILCs

Innate Lymphoid Cells

- MOSAIC

Mechanisms of Severe Acute Influenza Consortium

- NPA

Nasopharyngeal Aspirates

- TSLP

Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.J., J.D., O.M.K., M.C.Z., T.T.H. and P.J.O. contributed to the conception, design, analysis of data, and intellectual content. J.D. conducted experimental work, was involved with clinical study design and supervised sampling. A.J. and T.T. performed the statistical analysis and prepared figures. L.T.H. performed transcriptomic analysis. R.S.T. performed assay measurements and analysis. P.J.O. was study Principal Investigator. A.J., J.D. T.T.H and P.J.O. wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, Public Health England or the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest statement

AJ holds a Clinical Lectureship at the University of Cambridge which is supported jointly by the University of Cambridge Experimental Medicine Training Initiative (EMI) programme in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline (EMI-GSK) and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the funding received from this programme is not relevant to the content of this manuscript. TTH and Imperial Innovations are involved in setting up a medical device company called Mucosal Diagnostics (MD) that is an Imperial College spin-off company. PJO reports personal fees from Consultancy, grants from MRC, grants from EU Grant, grants from NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, grants from MRC/GSK, grants from Wellcome Trust, grants from NIHR (HPRU), grants from NIHR Senior Investigator, personal fees from European Respiratory Society, grants from MRC Global Challenge Research Fund, non-financial support from AbbVie, outside the submitted work; and Past President and Trustee of British Society for Immunology; Vice-Chair and Member, NERVTAG (New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group; Department of Health). The remaining authors declare that no relevant conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Myles P, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Semple MG, Brett SJ, Bannister B, Read RC, Taylor BL, McMenamin J, Enstone JE, Nicholson KG, Openshaw PJ, et al. Differences between asthmatics and nonasthmatics hospitalised with influenza A infection. The European respiratory journal. 2013;41:824–831. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Kerkhove MD, Vandemaele KaH, Shinde V, Jaramillo-Gutierrez G, Koukounari A, Donnelly Ca, Carlino LO, Owen R, Paterson B, Pelletier L, Vachon J, et al. Risk factors for severe outcomes following 2009 influenza a (H1N1) infection: A global pooled analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denholm JT, Gordon CL, Johnson PD, Hewagama SS, Stuart RL, Aboltins C, Jeremiah C, Knox J, Lane GP, Tramontana AR, Slavin Ma, et al. Hospitalised adult patients with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in Melbourne, Australia. The Medical journal of Australia. 2010;192:84–86. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshansky CM, Gartland AJ, Wong S-S, Jeevan T, Wang D, Roddam PL, Caniza Ma, Hertz T, Devincenzo JP, Webby RJ, Thomas PG. Mucosal immune responses predict clinical outcomes during influenza infection independently of age and viral load. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;189:449–462. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1616OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao R, Bhatnagar J, Blau DM, Greer P, Rollin DC, Denison AM, Deleon-Carnes M, Shieh W-J, Sambhara S, Tumpey TM, Patel M, et al. Cytokine and chemokine profiles in lung tissues from fatal cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1): role of the host immune response in pathogenesis. The American journal of pathology. 2013;183:1258–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everitt AR, Clare S, Pertel T, John SP, Wash RS, Smith SE, Chin CR, Feeley EM, Sims JS, Adams DJ, Wise HM, et al. IFITM3 restricts the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. Nature. 2012;484:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elderfield RA, Watson SJ, Godlee A, Adamson WE, Thompson CI, Dunning J, Fernandez-Alonso M, Blumenkrantz D, Hussell T, Zambon M, Openshaw P, et al. Accumulation of Human-Adapting Mutations during Circulation of A(H1N1)pdm09 Influenza Virus in Humans in the United Kingdom. Journal of Virology. 2014;88:13269–13283. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01636-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunning J, Blankley S, Hoang LT, Cox M, Graham CM, James PL, Bloom CI, Chaussabel D, Banchereau J, Brett SJ, Moffatt MF, et al. Progression of whole-blood transcriptional signatures from interferon-induced to neutrophil-associated patterns in severe influenza. Nature Immunology. 2018;19:625. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0111-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha A, Dunning J, Tunstall T, Hansel T, Openshaw P. 5.3 Allergy and Immunology. London: European Respiratory Society; 2016. Asthma patients hospitalized with influenza lack mucosal and systemic type 2 inflammation; p. OA4955. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Openshaw PJM, Hashim A, Gadd EM, Lim WS, Semple MG, Read RC, Taylor BL, Brett SJ, McMenamin J, Enstone JE, et al. Risk factors for hospitalisation and poor outcome with pandemic A/H1N1 influenza: United Kingdom first wave (May-September 2009) Thorax. 2010;65:645–651. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.135210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller E, Hoschler K, Hardelid P, Stanford E, Andrews N, Zambon M. The Lancet. Vol. 375. Elsevier Ltd; 2010. Incidence of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England : a cross-sectional serological study; pp. 1100–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leaker BR, Malkov VA, Mogg R, Ruddy MK, Nicholson GC, Tan AJ, Tribouley C, Chen G, De Lepeleire I, Calder NA, Chung H, et al. Mucosal Immunology. Nature Publishing Group; 2016. The nasal mucosal late allergic reaction to grass pollen involves type 2 inflammation (IL-5 and IL-13), the inflammasome (IL-1β), and complement; pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leynaert B, Sunyer J, Garcia-Esteban R, Svanes C, Jarvis D, Cerveri I, Dratva J, Gislason T, Heinrich J, Janson C, Kuenzli N, et al. Gender differences in prevalence, diagnosis and incidence of allergic and non-allergic asthma: a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2012;67:625–631. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenzel SE. Nature Medicine. Vol. 18. Nature Publishing Group; 2012. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches; pp. 716–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H, Fahy JV. The Cytokines of Asthma. Immunity. 2019;50:975–991. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelaia G, Vatrella A, Maselli R. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. Vol. 11. Nature Publishing Group; 2012. The potential of biologics for the treatment of asthma; pp. 958–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hambly N, Nair P. Monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of refractory asthma. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2014;20:87–94. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansel TT, Tunstall T, Trujillo-Torralbo M-B, Shamji B, Del-Rosario A, Dhariwal J, Kirk PDW, Stumpf MPH, Koopmann J, Telcian A, Aniscenko J, et al. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Nasal and Bronchial Cytokines and Chemokines Following Experimental Rhinovirus Infection in Allergic Asthma: Increased Interferons (IFN-γ and IFN-λ) and Type 2 Inflammation (IL-5 and IL-13) EBioMedicine. 2017;19:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai F, Abreu F, Ding HT, Choy D, Bremer M, Staton T, Erickson R, Peng K, Wang JS, Au-Yeung A, Hansel TT, et al. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Vol. 141. Elsevier; 2018. Nasal Biomarkers Characterization In Lebrikizumab Bronchoscopy Study (CLAVIER) p. AB118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rackemann FM. Journal of Allergy. Vol. 11. Elsevier; 1940. Intrinsic asthma; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters SP. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. Vol. 2. Elsevier Inc; 2014. Asthma Phenotypes: Nonallergic (Intrinsic) Asthma; pp. 650–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao K, Reinhardt RL. Cytokine. Vol. 75. NIH Public Access; 2015. The differential expression of IL-4 and IL-13 and its impact on type-2 immunity; pp. 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen K, Kolls JK. T cell-mediated host immune defenses in the lung. Annual review of immunology. 2013;31:605–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar RK, Foster PS, Rosenberg HF. Journal of leukocyte biology. Vol. 96. Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. Respiratory viral infection, epithelial cytokines, and innate lymphoid cells in asthma exacerbations; pp. 391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yadava K, Sichelstiel A, Luescher IF, Nicod LP, Harris NL, Marsland BJ. Mucosal Immunology. Vol. 6. Nature Publishing Group; 2013. TSLP promotes influenza-specific CD8+ T-cell responses by augmenting local inflammatory dendritic cell function; pp. 83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang Y-J, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie ANJ, Smith DE, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Nature Immunology. Vol. 12. Nature Publishing Group; 2011. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity; pp. 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rostan O, Arshad MI, Piquet-Pellorce C, Robert-Gangneux F, Gangneux J-P, Samson M. Crucial and Diverse Role of the Interleukin-33/ST2 Axis in Infectious Diseases. Andrews-Polymenis HL, editor. Infection and Immunity. 2015;83:1738–1748. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02908-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo XJ, Thomas PG. Seminars in immunopathology. Vol. 39. NIH Public Access; 2017. New fronts emerge in the influenza cytokine storm; pp. 541–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wark PAB, Johnston SL, Bucchieri F, Powell R, Puddicombe S, Laza-Stanca V, Holgate ST, Davies DE. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201:937–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contoli M, Message SD, Laza-Stanca V, Edwards MR, Wark PaB, Bartlett NW, Kebadze T, Mallia P, Stanciu La, Parker HL, Slater L, et al. Role of deficient type III interferon-lambda production in asthma exacerbations. Nature medicine. 2006;12:1023–1026. doi: 10.1038/nm1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards MR, Regamey N, Vareille M, Kieninger E, Gupta A, Shoemark A, Saglani S, Sykes A, Macintyre J, Davies J, Bossley C, et al. Mucosal Immunology. Vol. 6. Nature Publishing Group; 2013. Impaired innate interferon induction in severe therapy resistant atopic asthmatic children; pp. 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis TC, Henderson TA, Carpenter AR, Ramirez IA, McHenry CL, Goldsmith AM, Ren X, Mentz GB, Mukherjee B, Robins TG, Joiner Ta, et al. Nasal cytokine responses to natural colds in asthmatic children. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012;42:1734–1744. doi: 10.1111/cea.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller EK, Hernandez JZ, Wimmenauer V, Shepherd BE, Hijano D, Libster R, Serra ME, Bhat N, Batalle JP, Mohamed Y, Reynaldi A, et al. A mechanistic role for type III IFN-λ 1 in asthma exacerbations mediated by human rhinoviruses. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;185:508–516. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1462OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholas B, Dudley S, Tariq K, Howarth P, Lunn K, Pink S, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Monk P, Djukanović R, U-BIOPRED study group Susceptibility to influenza virus infection of bronchial biopsies in asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2017;140:309–312.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigo C, Leonardi-Bee J, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Lim WS. Effect of Corticosteroid Therapy on Influenza-Related Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015;212:183–194. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hay AD, Little P, Harnden A, Thompson M, Wang K, Kendrick D, Orton E, Brookes ST, Young GJ, May M, Hollinghurst S, et al. JAMA. Vol. 318. World Health Organization; 2017. Effect of Oral Prednisolone on Symptom Duration and Severity in Nonasthmatic Adults With Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infection; p. 721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.To KKW, Hung IFN, Li IWS, Lee K-L, Koo C-K, Yan W-W, Liu R, Ho K-Y, Chu K-H, Watt C-L, Luk W-K, et al. Delayed Clearance of Viral Load and Marked Cytokine Activation in Severe Cases of Pandemic H1N1 2009 Influenza Virus Infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;50:850–859. doi: 10.1086/650581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NICE. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Amantadine, oseltamivir and zanamivir for the treatment of influenza. London: 2009. [cited 2019 Apr 29]. 2009; [Internet] Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta168/resources/amantadine-oseltamivir-and-zanamivir-for-the-treatment-of-influenza-pdf-82598381928133. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venkatesan S, Myles PR, Leonardi-Bee J, Muthuri SG, Al Masri M, Andrews N, Bantar C, Dubnov-Raz G, Gérardin P, Koay ESC, Loh TP, et al. Impact of Outpatient Neuraminidase Inhibitor Treatment in Patients Infected With Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 at High Risk of Hospitalization: An Individual Participant Data Metaanalysis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017;64:1328–1334. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR, Leonardi-Bee J, Al Khuwaitir TSA, Al Mamun A, Anovadiya AP, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Báez C, Bassetti M, Beovic B, et al. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2014;2:395–404. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.British Thoracic Society Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Thorax. 2008;63(Suppl4):iv1–121. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.097741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, Anderson GP, Bel E, Brusselle G, Cullinan P, Custovic A, Ducharme FM, Fahy JV, Frey U, et al. Lancet (London, England) Vol. 391. Elsevier; 2018. After asthma: redefining airways diseases; pp. 350–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarjour NN, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Comhair SAA, Chung KF, Curran-Everett D, Dweik RA, Fain SB, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. Severe Asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;185:356–362. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1317PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw DE, Sousa AR, Fowler SJ, Fleming LJ, Roberts G, Corfield J, Pandis I, Bansal AT, Bel EH, Auffray C, Compton CH, et al. Clinical and inflammatory characteristics of the European U-BIOPRED adult severe asthma cohort. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46:1308–1321. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00779-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]