Abstract

Development of versatile probes that would enable study different conformations and recognition properties of therapeutic nucleic acid motifs by complementing biophysical techniques can greatly aid nucleic acid analysis and therapy. Here, we report the design, synthesis and incorporation of an environment-sensitive ribonucleoside analog, which serves as a two-channel biophysical platform to investigate RNA structure and recognition by fluorescence and 19F NMR spectroscopy techniques. The nucleoside analog is based on a 5-fluorobenzofuran-uracil core and its fluorescence and 19F NMR chemical shifts are highly sensitive to changes in solvent polarity and viscosity. Notably, the modified ribonucleotide and phosphoramidite substrates can be efficiently incorporated into RNA oligonucleotides (ONs) by in vitro transcription reaction and standard solid-phase ON synthesis protocol, respectively. Fluorescence and 19F readouts of the nucleoside incorporated into model RNA ONs are sensitive to neighboring base environment. The responsiveness of the probe was aptly utilized in detecting and quantifying the metal ion-induced conformational change in an internal ribosome entry site RNA motif of hepatitis C virus, which is an important therapeutic target. Taken together, our probe is a good addition to the nucleic acid analysis tool box with the advantage that it can be used to study nucleic acid conformation and recognition simultaneously by two biophysical techniques.

Introduction

The integral role of RNA in key biological processes emanates from its ability to adopt complex structures, which interconvert between different functional conformations.1–5 Basic understanding of RNA folding and its interaction with metal ions, proteins, nucleic acids and metabolites has not only provided valuable information on structure-function relationship but has also provided means to target RNA sequences related to disease states.6–9 Biophysical techniques like fluorescence,10–13 NMR,14–16 EPR17,18 and X-ray crystallography19,20 are routinely used to study RNA structure, dynamics and functions in real time and atomic level. Notably, fluorescence-based methods employing RNA ONs labeled with fluorescent nucleoside probes significantly aid the study of RNA.21–26 While NMR-based approaches are very useful, isotope labeling (13C and 15N) of nucleic acids is not straightforward and quite expensive.27,28 In this context, 19F atom can serve as a robust label to study nucleic acids because of the following reasons. The natural abundance of 19F isotope is 100% and its chemical shift is very sensitive to changes in its local electronic environment, including conformational changes in biopolymers.29 Further, absence of this atom in biological systems eliminates the background signal. These features of fluorine have been utilized in studying metal ion-induced hammered ribozyme folding,30 metal ion and peptide binding to HIV TAR RNA,31,32 nucleic acid secondary structures,33,34,35 RNA-ligand interactions,36,37 RNA invasion,38 single nucleotide polymorphism detection,39 nano particles40 and molecular bacon-based41 nucleic acid detection, DNA-protein interaction42 and nucleic acid secondary structure in living cells.43–45 Though, the utilities of fluorescence and NMR as standalone techniques are arguably undeniable, constructing a probe system that features both fluorescent and 19F NMR labels will be highly beneficial as nucleic acids can be analyzed by these two powerful and complementing biophysical techniques concurrently. However, chemical tools that combine the useful features of both fluorescence and 19F NMR techniques are rare.

Recently, in an effort to combine two complementary biophysical techniques, bifunctional probes have been developed for studying different DNA secondary structures by fluorescence and 19F NMR spectroscopy techniques.46–48 We have also developed dual-purpose nucleoside probes composed of either fluorescent and X-ray labels or fluorescent and 19F labels.49–52 The nucleoside analogs were constructed by attaching heterocycles like selenophene and fluorobenzofuran at the C5 position of pyrimidine nucleosides, which imparted useful fluorescence properties. For example, selenophene-modified 2'-deoxyuridine analog served as a dual-app probe in detecting DNA conformations by fluorescence and X-ray crystallography (anomalous scattering of Se atom is widely used in X-ray crystallography of biomolecules).51 On the other hand, fluorobenzofuran-modified 2'-deoxyuridine provided an unprecedented probing system to study the structural polymorphism and ligand binding abilities of G-quadruplex structures formed by human telomeric DNA repeat in real time by fluorescence and in live cells by 19F NMR.52 Encouraged by these studies, we sought to harness the utility of this probe design in the conformational analysis of RNA. For this purpose, we developed fluorobenzofuran-modified ribonucleoside analog and its triphosphate and phosphoramidite substrates that would enable the enzymatic as well as chemical synthesis of labeled RNA ONs. Here, we report the synthesis, incorporation and utility of 5-fluorobenzofuran-modified uridine analog 1 in probing metal ion-induced conformational change of an important viral RNA target, namely internal ribosome entry site (IRES) RNA motif of hepatitis C virus HCV. The nucleoside analog shows emission in the visible region with a reasonable quantum yield and displays excellent solvatochromism. Its 19F chemical shift is also sensitive to changes in solvent polarity and viscosity. Rewardingly, the modified ribonucleotide is efficiently incorporated into RNA transcripts in vitro by T7 RNA polymerase. The nucleoside phosphoramidite is also compatible for incorporation by conventional solid-phase method. The fluorescence and 19F signals of the nucleoside incorporated into model ONs are sensitive to flanking bases. Further, the responsiveness of the probe was used in studying the metal ion-induced conformational change in IRES RNA motif of HCV by these techniques.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and environment sensitivity of 5-fluorobenzofuran-modified uridine 1

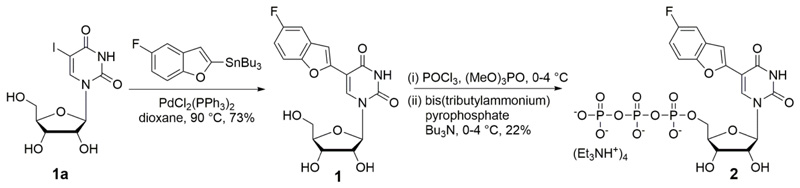

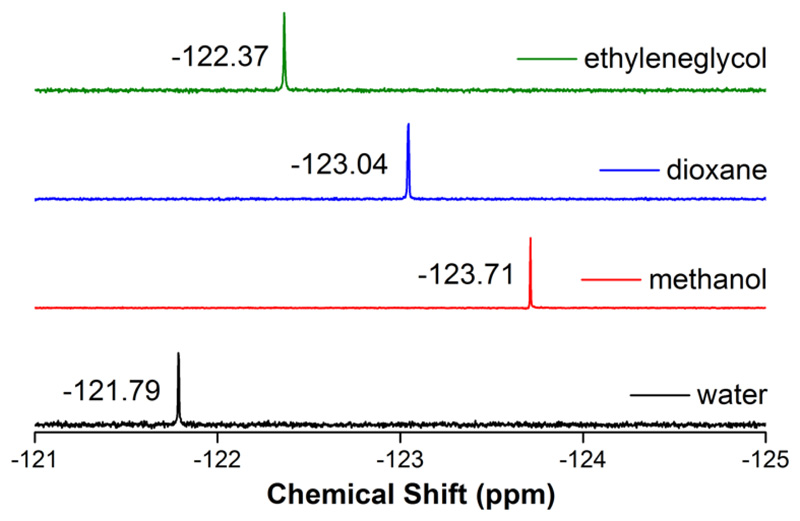

5-Fluorobenzofuran-modified uridine analog 1 was synthesized by Stille cross-coupling of stanylated 5-fluorobenzofuran52 with 5-iodouridine (Scheme 1). Before incorporating into RNA ONs the environment-sensitivity of the nucleoside analog was evaluated by performing photophysical and 19F NMR studies in solvents of different polarity and viscosity. Absorption maxima of the nucleoside 1 was minimally affected by polarity changes (Figure 1A). However, steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence properties of 1 were significantly influenced by polarity of the medium. Nucleoside 1 in water (ET(30), a solvent polarity parameter53 = 63.1) showed intense emission band (λem = 437 nm) corresponding to a quantum yield of 0.14 and an average lifetime of 0.95 ns (Table 1 and Figure S1). In less polar solvents like methanol (ET(30) = 55.4) and dioxane (ET(30) = 36.0) its emission band blue shifted to 420 nm and 400 nm, respectively, and exhibited lower quantum yields and comparatively shorter lifetimes (Ф = 0.05 and τav = 0.81 ns in methanol; Ф = 0.05 and τav = 0.85 ns in dioxane, Figure 1A, Table 1 and Figure S1). A linear correlation between Stokes shifts determined in solvents of different polarity and ET(30) value of respective solvents confirmed the responsiveness of the probe to polarity changes in the microenvironment (Figure S2). The relative orientation of the heterocycle ring with respect to the uracil ring, which is attached via a rotatable aryl-aryl bond could affect the emission properties of the probe.54 This aspect of the nucleoside analog was tested by recording the fluorescence in solvents of similar polarity but different viscosity. The analog exhibited a higher quantum yield and longer lifetime in glycerol (η at 25 °C = 954 cP) as compared to in ethylene glycol (η at 25 °C =16.1 cP) (Figure 1B, Table 1 and Figure S1). Furthermore, higher anisotropy value in high viscous solvent proved the rigidification of the fluorophore, which also explains the observed enhancement of fluorescence intensity in viscous medium. Notably, the ribonucleoside analog displayed distinct 19F NMR chemical shifts in solvents of different polarity and viscosity (Figure 2). In solvents of different polarity, orientation of the nucleoside probe's dipole is different, which can impact the shielding of the fluorine atom and alter its chemical shift.55 In solvents with different viscosity, the relative orientation of fluorobenzofuran and uridine rings change, which can affect the electronic environment surrounding the fluorine atom and hence, its chemical shift.54 Together, these observations clearly reveal that both fluorescence properties and 19F signal of nucleoside 1 are highly sensitive to the local environment, and hence, could be apt for studying RNA conformations and recognition properties.

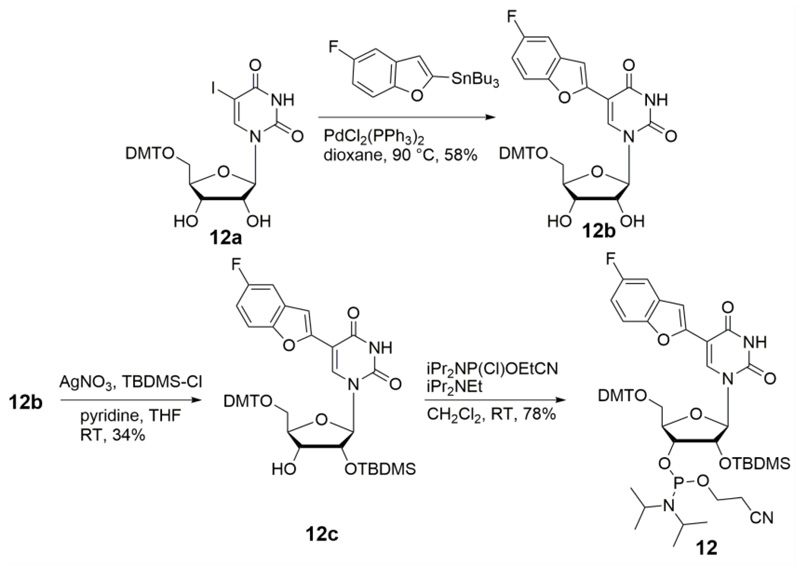

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of uridine analog 1 and its corresponding triphosphate 2. See SI for details.

Figure 1.

(A) UV (25 μM, solid lines) and steady-state fluorescence (5 μM, dashed line) spectra of nucleoside 1 in solvents with different polarity. In fluorescence study, samples were excited at respective lowest energy absorption maximum with excitation and emission slit width 2 nm and 3 nm, respectively. (B) Steady-state fluorescence spectra (5 μM, dashed line) of nucleoside 1 in solvents with similar polarity (ethylene glycol and glycerol) but different viscosity. Samples were excited at respective lowest energy absorption maximum with excitation and emission slit widths of 2 nm and 2 nm, respectively.

Table 1. Photophysical properties of nucleoside 1 in different solvents.

| Solvent | λmaxa (nm) | λem (nm) | Stokes shift x103 (cm-1) | Irelb | Φc | τavc (ns) | rc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| water | 322 | 437 | 8.17 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.02 |

| methanol | 322 | 420 | 7.25 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.81 | nd |

| dioxane | 324 | 400 | 5.86 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.85 | nd |

| ethylene glycol | 325 | 423 | 7.13 | 1.49 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.18 |

| glycerol | 326 | 422 | 6.98 | 3.30 | 0.54 | 2.78 | 0.32 |

Lowest absorption energy maximum is given.

Relative emission intensity at λem is given with respect to intensity in water.

Standard deviation for quantum yield (Φ), average lifetime (τav) and anisotropy (r) in different solvents is ≤ 0.005, ≤ 0.02 ns and ≤ 0.003 respectively. nd = not determined.

Figure 2.

19F NMR spectra of nucleoside 1 (600 μM) in solvents of different polarity and viscosity. Each NMR sample contained 15% DMSO-d6 and each spectrum was referenced relative to an external standard trifluorotoluene (TFT: -63.72 ppm).

T7 RNA polymerase efficiently incorporates modified nucleotide into RNA transcripts

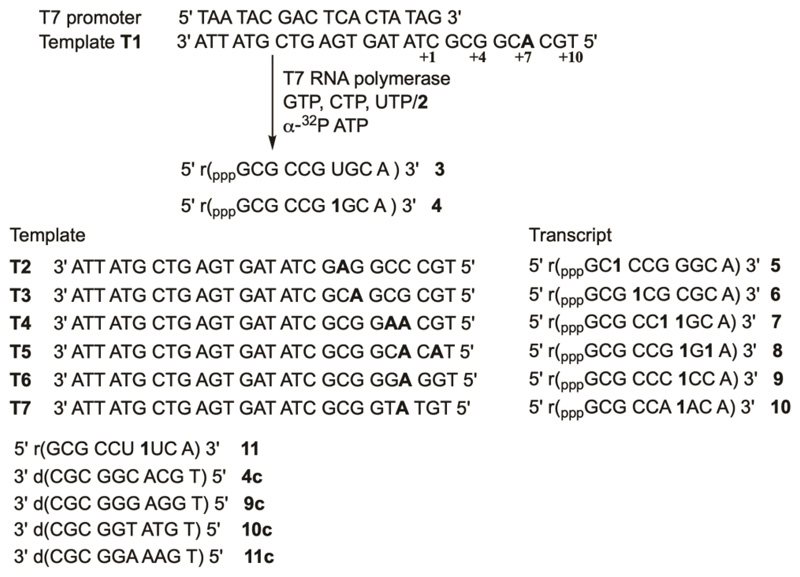

We first studied the possibility of synthesizing fluorobenzofuran-modified RNA ONs by in vitro transcription reaction. The modified triphosphate substrate 2 was synthesized according to the steps shown in Scheme 1 and transcription reactions were performed as depicted in Figure 3. A series of templates (T1–T5) containing one or two 2'-deoxyadenosines at different positions to direct the incorporation of native or modified nucleotide 2 in the transcripts was designed. The templates were annealed to a T7 RNA polymerase DNA promoter sequence and reactions were initiated by adding the enzyme in the presence of GTP, CTP, UTP/2 and α-32P ATP. Notably, at the 5' end of each template, there is a 2'-deoxythymidine residue, which would direct the incorporation of an α-32P-labeled adenosine mononucleotide at the 3' end of each transcript. Therefore, if a transcription reaction is successful then only the full-length transcript containing α-32P label would be visible upon phosphor imaging. Transcripts shorter than the full-length product may not be visible as they would not carry α-32P label.

Figure 3.

Incorporation of the modified nucleotide analog into RNA ONs by transcription reaction in presence of different DNA templates T1–T7. RNA ON 11 was synthesized by solid phase method using phosphoramidite 12 (Scheme 2). ONs 4c, 9c, 10c and 11c are cDNA ONs used in fluorescence and 19F NMR studies. "r" represent the RNA ONs and "d" represents DNA ONs.

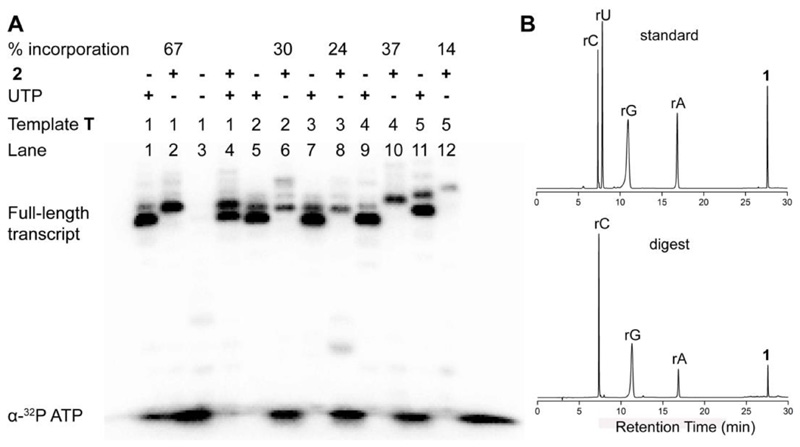

Percentage incorporation of the modified nucleotide in case of each template was calculated relative to the full-length product obtained from a reaction performed in the presence of UTP. A reaction in the presence of T1 where dA residue was away from the transcription start site yielded the full-length ON product 4 in good yields along with trace amounts of N+1, N+2 and N+3 bands due to the known non-templated incorporation of nucleotides by T7 RNA polymerase (Figure 4A, Lane 2). Retarded mobility of modified transcript 4 with respect to unmodified transcript 3 suggests the incorporation of a higher molecular weight nucleotide analog into the transcript. Importantly, in the absence of both UTP and 2 there was no full-length product, which proved that the formation of the full-length transcript was not due to any misincorporation of nucleotides (Figure 4A, lane 3). Further, when the reaction was performed with an equimolar ratio of 2 and natural UTP, the polymerase showed similar preference for both the substrates (lane 4). In the presence of templates T2 and T3 where dA was near the start site, +3 and +4 positions, respectively, a significant reduction in transcription efficiency was observed (lanes 6 and 8). Templates T4 and T5 produced doubly modified transcripts with nucleotide analog in successive and alternating positions, respectively, albite with reduced efficiency (lanes 10 and 12).

Figure 4.

(A) Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of transcripts obtained from in vitro transcription reactions with DNA templates T1–T5 in the presence of UTP and or 2 under denaturing conditions. All reactions were performed in duplicate and standard deviations in yields are ≤ 4%. (B) RP-HPLC chromatogram of a mixture of standard nucleosides (rC, rU, rG, rA) and modified nucleoside 1 (top) and ribonucleoside products obtained from digestion of transcript 4 at 260 nm (bottom). See experimental section for details.

Large-scale reaction was performed with T1, and thus obtained transcript 4 was purified by PAGE. RP-HPLC confirmed the purity of the isolated product and MALDI-TOF mass measurement confirmed the incorporation of modified nucleotide into the full-length transcript (Figure S3). Further, enzymatic digestion of transcript 4 followed by HPLC analysis of the resulting ribonucleoside mixture unambiguously confirmed the presence of nucleoside 1 in the transcript (Figure 4B). Taken together, these results indicate that nucleotide analog 4 is a reasonably good substrate for the enzyme and transcription reaction can be used to synthesize RNA ONs labeled with fluorobenzofuran modified nucleotide.

Nucleoside analog incorporated into RNA ONs is sensitive to neighbouring base environment

In ONs, the probe placed in different neighbouring base environments can alter its fluorescence properties and 19F NMR chemical shift by different mechanisms. For example, staking interaction with flanking bases, H-bonding interaction, microenvironment polarity and electron transfer process between the modified base and adjacent bases could influence the outcome of fluorescence and NMR signals.46,56–58 In order to examine the responsiveness of the probe to changes in flanking bases, we decided to synthesize model RNA ONs 4, 9, 10 and 11, wherein the probe is placed in-between two rG, rC, rA and rU residues, respectively (Figure 3). ONs 4, 9 and 10 were synthesized by large-scale transcription reactions using appropriate templates (Figure 3). The transcripts were purified by PAGE and analyzed by mass spectrometry (Table S1). ON 11 with modified uridine flanked between native uridines cannot be prepared by transcription reaction as it is difficult to site-specifically incorporate nucleotide analog using RNA polymerase. Hence, we resorted to solid-phase RNA ON synthesis protocol to synthesize ON 11. The phosphoramidite substrate 12 was synthesized as illustrated in Scheme 2 and was site-specifically incorporated to prepare ON 11, which was PAGE purified and its identity was confirmed by mass analysis (Table S1).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 5-fluorobenzofuran-modified uridine phosphoramidite 12. DMT = 4,4'-dimethoxytrityl, TBDMS = tert-butyldimethylsilyl, THF = tetrahydrofuran. See SI for details.

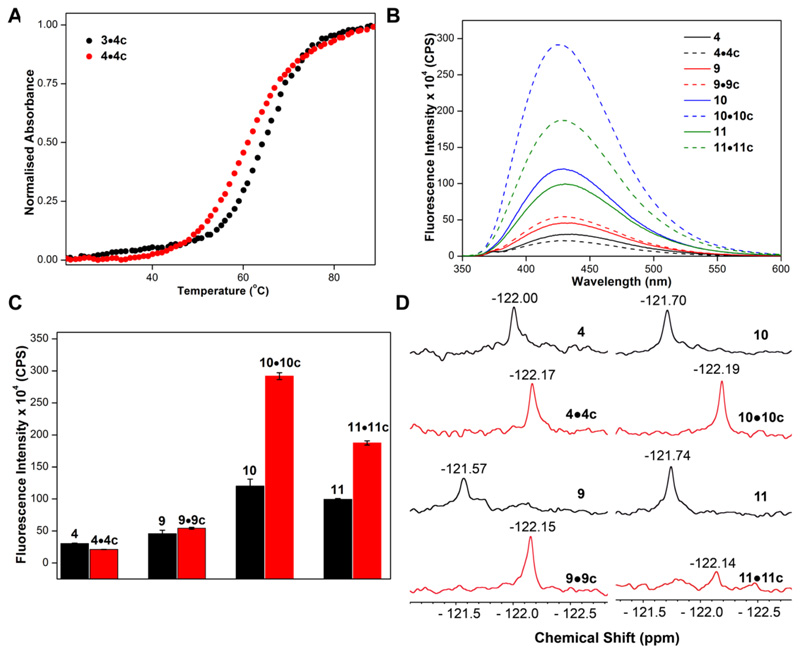

First, the effect of modification on duplex stability was examined by thermal melting analysis of duplexes (4•4c, 9•9c, 10•10c and 11•11c) formed by hybridizing modified RNA ONs with complementary ONs. Control unmodified duplex 3•4c and modified duplex 4•4c exhibited similar Tm values, indicating that the modification has minor impact on the duplex stability (Figure 5A and Table S2). It was also observed that except 11•11c, other duplexes were reasonably stable at room temperature under which the fluorescence and NMR experiments were eventually performed (Table S2). The modified nucleoside 1 when flanked by different bases in single stranded ONs exhibited different fluorescence intensities. When placed in-between rG or rC (ONs 4 and 9), the fluorescence was quenched, whereas in-between rA or rU (ONs 10 and 11), we observed an enhancement in fluorescence intensity (Figure 5B and 5C). Duplexes made of ONs 10 and 11 (10•10c and 11•11c) displayed significantly higher fluorescence intensity with no change in emission maximum as compared to respective single-stranded RNA ONs. However, duplexes made of ONs 4 and 9 did not shown appreciable change in fluorescence intensity. We believe the following could be the reason for the fluorescence exhibited by the duplexes. The C5-modified nucleoside analog in the duplex structure should be in the major groove and will experience partial stacking interaction with adjacent bases. In this scenario, the fluorobenzofuran ring could be rigidified, which would result in enhancement in fluorescence intensity. This is what we observed in case of duplexes (10•10c and 11•11c) containing the modification, which are flanked by rA or rU bases. However, in case of duplexes 4•4c and 9•9c, due to the presence of guanosine in the vicinity of the nucleoside analog, the fluorescence was quenched possibly due to the known electron transfer process.57 In 19F NMR studies, the single stranded ONs showed distinct 19F chemical shifts (Figure 5D). The nucleoside analog in the duplexes showed chemical shift in the shielded region compared to respective single-stranded RNA ONs. This change in chemical shift is likely due to more stacking interaction experienced by the duplex than the single stranded RNA ON.46 Collectively, these results indicate that the nucleoside analog is responsive to changes in neighbouring base environment, and hence, could potentially serve as a conformation-sensitive probe because conformational changes in RNA could result in subtle changes in the local environment that could have manifestations in fluorescence and NMR read outs. Therefore, as a test system we chose to study the metal-ion induced conformational change in the IRES element of Hepatitis C virus, a well-known therapeutic RNA target.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative UV-thermal melting profile of control (3•4c) (5 μM) and modified (4•4c) (5 μM) duplexes in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.1) containing 500 mM NaCl. (B) Emission spectra (0.5 μM) single stranded ONs 4, 9–11 (solid lines) and duplexes (dotted lines). (C) Bar diagram showing the fluorescence intensity of ONs at respective emission maximum. (D) 19F NMR spectra of ONs 4, 9–11 and duplexes (50 μM) in sodium phosphate buffer containing 500 mM NaCl.

Nucleoside analog reports metal ion-mediated conformational change in the IRES element

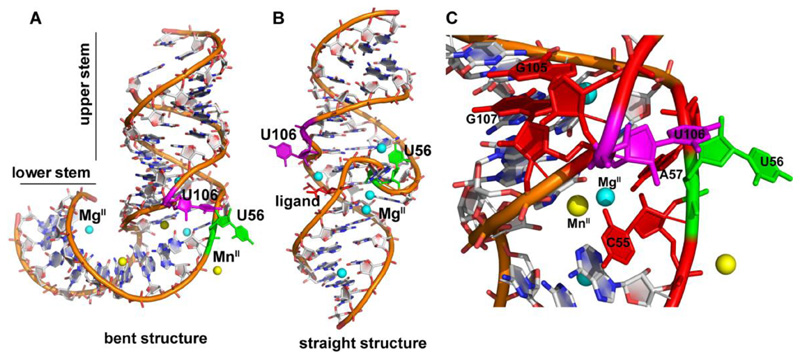

HCV is an RNA virus, which contains a highly structured IRES motif at the 5' end of its genome.59 It binds to the host 40S ribosomal subunit and initiates cap-independent translation process.60,61 The IRES element is composed of four independently folding domains.62 Domain II is highly conserved in different HCV clinical isolates63 and plays key roles such as recruitment of the viral mRNA at the ribosomal decoding site,64 dissociation of initiation factor from 40S subunit to promote 80S ribosomal assembly65 and transition from initiation to elongation steps.66 Particularly, subdomain IIa, a RNA conformational switch, adopts a 90° bent structure, which is stabilized by divalent metal ions like MgII and MnII, and this conformation is essential for translation initiation (Figure 6A).67,68 For this reason, the subdomain IIa of IRES is identified as an attractive target for the discovery of small molecule antiviral agents.63 Benzimidazole-based ligands inhibit viral translation by locking the extended conformation of IIa subdomain.69,70 High resolution structures of IIa for both metal ion-stabilized bent and benzimidazole-locked straightened conformation have been obtained by X-ray and NMR spectroscopy (Figure 6A and 6B).67,68,71,72 The L-shaped structure of subdomain IIa has a fold at internal bulge, which is flanked by two stems arranged at a right angle to each other.68 Additionally, a looped-out U106 residue at the upper stem is a characteristic feature of the bent structure. The whole L-shaped structure is stabilized by base stacking, H-bonding and direct interaction with the metal ions. In the presence of a benzimidazole ligand, the structure is straightened where the internal bulge refolds from its bent conformation and gets flanked by two coaxial helices.69,70 Subdomain IIa construct labeled with a cyanine dyes FRET pair at the two terminals reports metal-mediated RNA folding by an increase in FRET signal and ligand-induced straightening of the structure by a reduction in FRET signal.69 Apart from global structural studies, 2-aminopurine (2AP)-labelled fluorescent RNA has been used to quantify the binding affinity of MgII and MnII at different sites of the structural element.68 Based on this understanding, we aimed to use the responsiveness of our nucleoside probe in monitoring the metal ion-induced conformational change in the IRES subdomain IIa.

Figure 6.

(A) Crystal structure (PDB ID: 2NOK)68 of L-shaped bent conformation of IRES subdomain IIa stabilized by MgII and MnII. (B) Crystal structure (PDB ID: 3TZR)70 of ligand-bound straight conformation of IRES subdomain IIa. Benzimidazole ligand is represented in red color. (C) Neighbouring base environment of U56 and U106 at bent conformation (PDB ID: 2NOK). Two neighbouring bases of U106 (G105 and G107) and two neighbouring bases of U56 (C55 and A57) are shown in red color. U106 and U56 are represented in magenta and green color, respectively. MgII and MnII are represented as cyan and yellow color sphere, respectively.

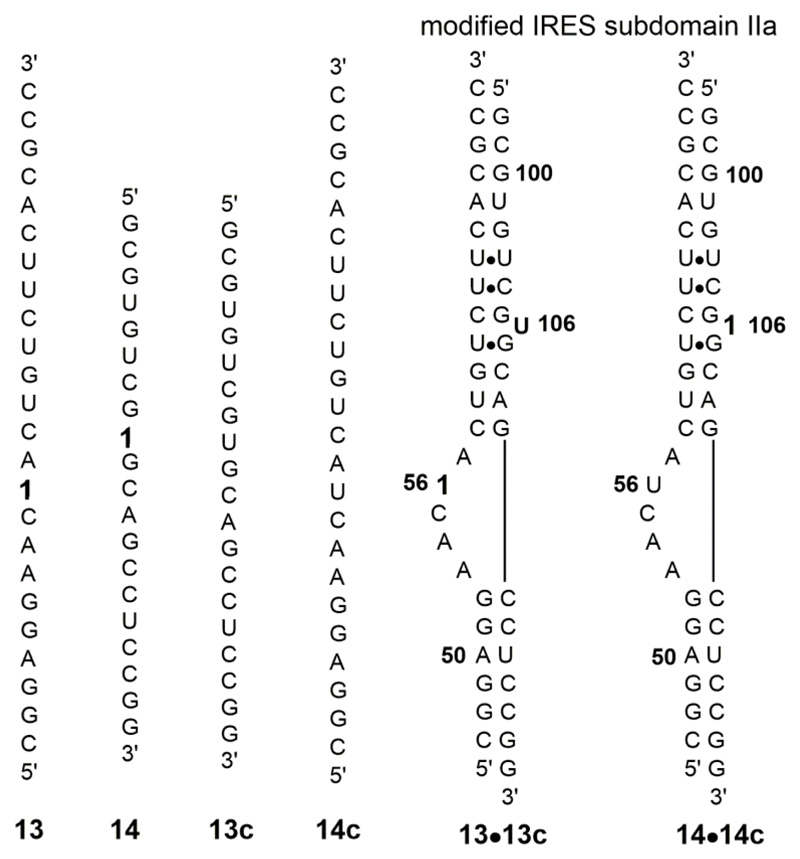

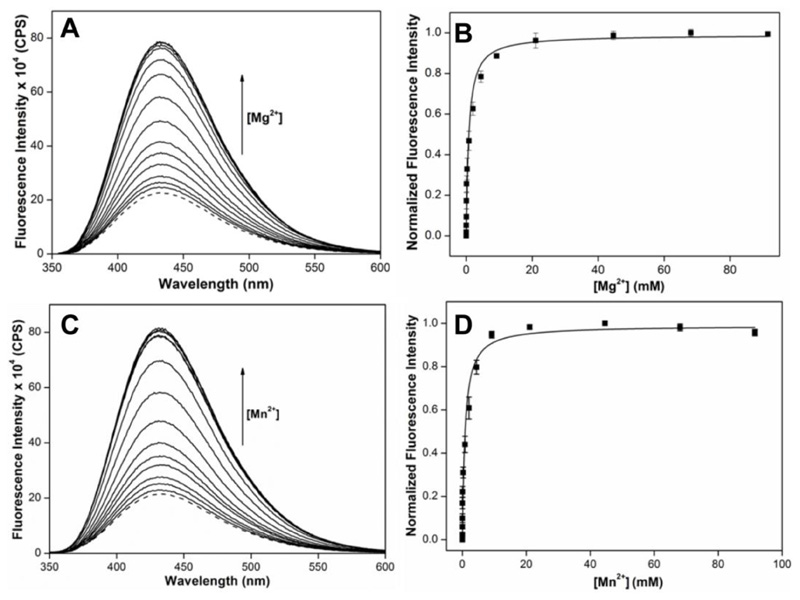

RNA ONs 13 and 14 were synthesized by solid-phase method and were annealed to complementary RNA ONs 13c and 14c, respectively, to form the IRES subdomain IIa duplexes 13•13c and 14•14c (Figure 7). The labeled ONs were purified by PAGE and characterized by MALDI-TOF mass analysis (Figure S4). In 13•13c that modification is placed at U56 (bulge region) and in 14•14c it is placed at U106 (stem region). We selected these positions for modification as crystal structures reveal substantial conformational change in these bases during metal ion-mediated bending and ligand-induced straightening of IRES element (Figure 6A and 6B). Fluorescence profile of duplexes 13•13c and 14•14c annealed in sodium cacodylate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.5) was recorded with increasing concentration of MgII or MnII ions. In the absence of these metal ions the duplexes show low fluorescence (Figure 8 and Figure S5). Addition of individual metal ions resulted in an increase in fluorescence intensity exhibiting a saturation binding isotherm with negligible changes in emission maximum (Figure 8 and Figure S5). The extent of enhancement was significantly larger in case of 14•14c in which the nucleoside 1 is placed in the stem region (U106) as compared to 13•13c containing the modification in the bulge region (U56). A plot of normalized fluorescence intensity versus metal ion concentration provided apparent dissociation constants Kd for the binding of metal ions to IRES domain IIa (Table 2). The Kd values are comparable to the reported dissociation constants obtained using the same IRES subdomain IIa motif modified with 2-aminopurine.68 In a control experiment, addition of metal ions to the free nucleoside 1 resulted only in minor changes in fluorescence intensity, which indicated that the nucleoside signalled only the metal ion-mediated conformational change in the HCV IRES subdomain IIa (Figure S6).

Figure 7.

Fluorobenzofuran modified RNA ON 13 and 14 and their complementary RNA sequence 13c and 14c. They form respective modified IRES domain IIa duplexes, 13•13c and 14•14c where U56 and U106 residues were replaced with nucleoside 1.

Figure 8.

Emission spectra and corresponding curve fits for the titration of subdomain IIa duplex 14•14c (0.5 μM) in sodium cacodylate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.5) with increasing concentration of MgII (A and B) and MnII (C and D) ions. Dashed lines represent the spectrum of duplexes in the absence of the metal ions.

Table 2. Kd values for MgII and MnII ions binding to 13•13c and 14•14c.

| metal ion | Kd (mM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 13•13c | 14•14c | |

| MgII | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.77 ± 0.15 |

| MnII | 0.032 ± 0.005 | 0.83 ± 0.16 |

The structure of IRES subdomain IIa in the absence of metal ions is not deduced, and hence, the reason for the observed fluorescence in the absence of metal ions is speculated here. 13•13c and 14•14c in the absence of metal ions exhibit a similar emission maximum (λem ~ 430 nm) indicating a polarity in-between water and methanol around the nucleoside analog placed in U56 and U106 positions, respectively (Table 1). However, in 13•13c motif the modification at U56 is flanked between C and A, whereas in 14•14c U106 is likely stacked between two guanine bases. It is well known that many fluorophores when placed near a guanine base exhibit quenched fluorescence due to electron transfer process.57 Due to this 14•14c shows lower fluorescence compared to 13•13c in the absence of metal ions. In the presence of metal ions, the subdomain IIa adopts a bent structure in which the U106 is extrahelical and not stacked between the adjacent guanine bases (Figure 6C). Hence, the modification placed in the U106 position of 14•14c displayed a significant enhancement in fluorescence intensity upon addition of metal ions. While the conformation of U56 in the presence of metals is also extrahelical, the extent of fluorescence enhancement is less as the intensity of 13•13c in the absence of metal ions is higher to begin with. Taken together, the probe successfully reports metal-mediated structure change in IRES subdomain IIa and also enables the quantification of metal ion binding by means of changes in fluorescence intensity.

19F NMR studies of modified IRES subdomain IIa

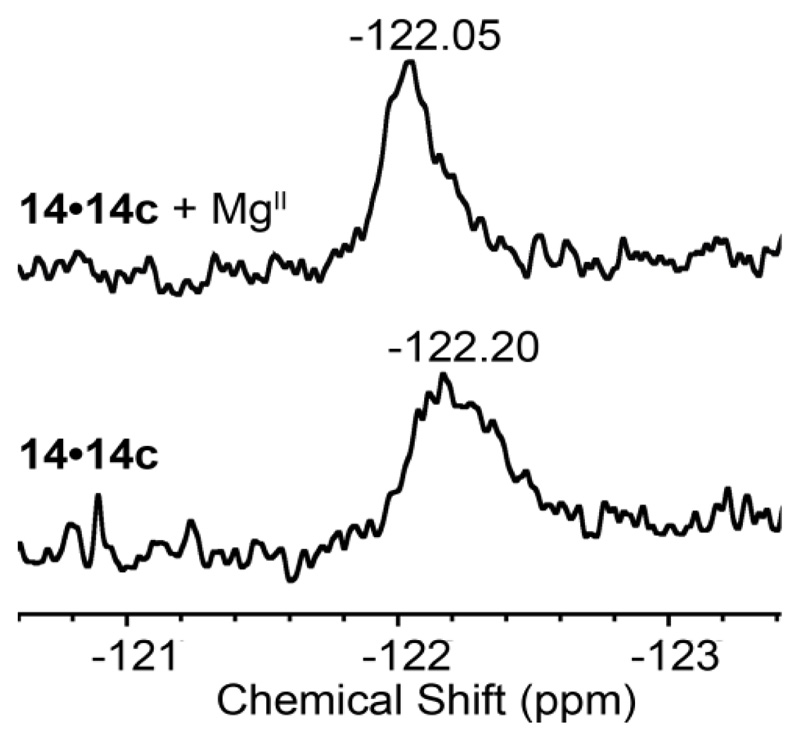

As duplex 14•14c displayed significant fluorescence response upon metal ion binding, we performed basic 19F NMR study of this duplex in the absence and presence of metal ions. Slight change in chemical shift and discernible sharpening of the 19F NMR peak in the presence of MgII ions suggest that the nucleoside probe at U106 is responsive to the conformational change as a result of bending of the domain (Figure 9). The sharpening of 19F NMR peak in the presence of metal ions indicates higher tumbling rate and slower relaxation of the nucleoside probe in extrahelical conformation in the bent state compared to the most likely staked conformation in metal-free elongated state.73 A small change in chemical shift to the deshielded region in the presence of MgII further confirms the destacking of the probe in the extrahelical conformation. The chemical shift trend observed here is similar to the trend noticed in Figure 5, where single-stranded RNA ONs show deshielded chemical shift due to reduced stacking compared to the duplexes. Duplex 13.13c showed only small changes in fluorescence intensity upon metal ion addition (Figure S5), and hence, we did not perform 19F NMR study with this duplex. Due to the paramagnetic nature of MnII, IRES-MnII complex did not give any 19F NMR signal.

Figure 9.

19F NMR study of fluorobenzofuran-modified IRES subdomain IIa duplex 14•14c (50 μM) in 10 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 6.5) in the absence and presence of 5 mM MgII.

Conclusions

We have developed a ribonucleoside analog, which acts as an environment-sensitive fluorescence and 19F NMR probe. Fluorescence quantum yield, emission maximum, excited-state lifetime and 19F NMR chemical shift of the probe are sensitive to polarity and viscosity changes. We successfully incorporated the nucleoside analog into RNA ONs by both transcription reaction and solid-phase method. Interestingly, after incorporation into RNA ONs, the fluorescence and 19F NMR properties of the nucleoside probe are responsive to its flanking bases. When the analog is flanked by A or U bases and hybridized to a complementary strand, it shows significant enhancement in fluorescence intensity. However, when flanked by G or C bases, the fluorescence of the modified nucleoside was much lower in both single-stranded and double-stranded states. It is speculated that a combined effect of polarity around the nucleoside analog, stacking interaction with neighboring bases, rigidification of the fluorophore and electron transfer process between proximal guanine bases and the nucleoside analog is responsible for the observed fluorescence changes exhibited by the probe in different ON sequences. Similarly, the analog placed in-between different flanking bases in single-stranded ONs displayed unique 19F NMR signals, which were found to be shifted to the shielded region when hybridized to complementary ONs. Further, using the responsiveness of the probe we developed a method to detect and quantify metal ion-mediated conformational change in IRES subdomain IIa, which is an important target for the discovery of antiviral small molecules against HCV. In particular, when U106 was replaced with the probe, it exhibited a dose-dependent increase in emission intensity upon addition of metal ions (MgII and MnII), which further enabled the quantification of binding affinities. It is important to mention here that the sensitivity of the probe to report conformational changes in nucleic acids depends on the position of modification in the sequence. Taken together, easy incorporation of the analog by enzymatic and chemical methods, and responsiveness to conformational changes highlight the usefulness of our two-channel readout system in investigating nucleic acid structure and recognition.

Experimental Section

See Supporting Information for the synthesis of 5-fluorobenzofuran-modified uridine 1, corresponding triphosphate 2 and phosphoramidite 12.

Photophysical analysis of uridine analog 1 in different solvents

Absorption and steady-state fluorescence studies

Absorption spectra of nucleoside 1 (25 μM) were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer in quartz cuvette (Hellma, path length 1 cm). Each sample contained 2.5% DMSO. Steady-state fluorescence of nucleoside 1 (5 μM) in different solvents was performed in micro fluorescence quartz cuvette (Hellma, path length 1 cm) on Fluoromax-4C spectrometer. Samples were excited at their lowest energy absorption maximum (Table 1). Each sample contained 0.5% DMSO. Anisotropy (r) of nucleoside 1 in different solvents was determined by analysing the data using software provided with the instrument Fluoromax-4C spectrofluorometer. Each anisotropy value was an average of 10 successive measurements. All UV absorption, steady-state fluorescence and anisotropy measurements were performed in triplicate.

Time-resolved fluorescence study

Time-resolved fluorescence study of nucleoside 1 was performed using time correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) setup (Horiba Jobin Yvon). Nucleoside 1 (5 μM) in water or ethylene glycol or glycerol was excited by using 339 nm LED source (IBH, UK, NanoLED-339L). In dioxane and methanol, nucleoside 1 (400 μM) was excited by using 375 nm diode laser source (IBH, UK, NanoLED-375L). Fluorescence signal at respective emission maxima was collected. All studies were done in triplicate and lifetimes were calculated by fitting the decay profile using IBH DAS6 software. The χ2 value for all the curve fits was found to be nearly one.

Quantum yield

Quantum yield of nucleoside 1 in different solvents was determined relative to 2-aminopurine as the standard. Following equation was used to calculate the quantum yield.74

Where s is the standard, x is the modified nucleoside, A is the absorbance at excitation wavelength, F is the area under the emission curve, n is the refractive index of the solvent, and ΦF is the quantum yield. Quantum yield of 2-aminopurine in water is 0.68.

Transcription reaction with α-32P ATP

A 1:1 solution of DNA template T1–T5 (5 μM) and promoter DNA ON sequence was annealed in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8) at 90 °C for 3 min and allowed to attain room temperature. The solution was kept on an ice bath for 30 min and stored at -40 °C. Transcription was performed at 37 °C in 40 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8) using 250 nM of promoter-template duplexes, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM of dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mM spermidine, 1 U/μL, RNase inhibitor (Riboblock), 1 mM GTP, CTP, UTP and or modified UTP 2, 20 μM ATP, 5 μCi α-32P ATP and 3 U/μL (total 60 units) T7 RNA polymerase in a total 20 μL reaction volume. After 3.5 h, the reaction was quenched using 20 μL of loading buffer (7 M urea in 10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, pH 8). The samples were heated at 75 °C for 3 min and then cooled on an ice bath. The samples (4 μL) were loaded on a sequencing 18% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and were electrophoresed at a constant power (11 W) for nearly 4 h. The bands corresponding to the radioactive products were imaged using an X-ray film. The relative transcription efficiency was calculated using GeneTools software from Syngene. The % of incorporation of modified UTP 2 into RNA ONs by T7 RNA polymerase was determined considering the transcription efficiency in presence of all natural NTPs as 100 %. Reactions were performed in duplicate and the errors in yields were ≤ 4%.

Large-scale transcription

Large scale transcription reaction in a total volume of 250 μL was performed with template T1 for isolation and further characterization of transcript 4. Transcription reaction contained 2 mM GTP, ATP, CTP and modified UTP 2, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.4 U/μL of RNase inhibitor (RiboLock), 800 units T7 RNA polymerase and 300 nM promoter-template duplex. The transcription reaction was performed at 37 °C for 12 h and white precipitation of pyrophosphate was observed. The reaction volume was reduced to one third using speedvac. 40 μL loading buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, 7 M urea, 100 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) was added and loaded onto to a 20% polyacrylamide gel and run at 25 W constant power for 6 h. Gel was UV shadowed, appropriate band corresponding to the full-length transcript was cut and transferred to a Poly-Prep column (Bio-Rad). The gel pieces were crushed, the transcript was extracted with 0.5 M ammonium acetate for 12 h and desalted using Sep-Pak classic C18 cartridges. Similar procedure was used to prepare ONs 9 and 10. Around 12–14 nmole of the transcripts was isolated from each reaction.

Enzymatic digestion of transcript 4

Transcript 4 (4 nmole) was incubated with snake venom phosphodiesterase I (0.01 U), calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (1 U/μL) and RNase A (0.25 μg), 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5, 40 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA) in a total volume of 100 μL for 12 h at 37 °C. RNase T1 (0.2 U/μL) was then added and the sample was incubated for another 4 h at 37 °C. The resulting mixture obtained from the digestion was analyzed by RP-HPLC using Phenomenex-Luna C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 micron) at 260 and 322 nm. Mobile phase A: 50mM TEAA buffer (pH 7.3), mobile phase B: acetonitrile. Flow rate: 1 ml/min. Gradient: 0–10% B in 20 min, 10–100% B in 10 min.

Solid-phase RNA ON synthesis

5-Fluorobenzofuran-modified RNA ONs 11, 13 and 14 were synthesized on a 1.0 μmol scale (1000 Å CPG solid support) by a standard ON synthesis protocol using phosphoramidite 12.75 After trityl deprotection on the synthesizer, the solid support was treated with 1.5 ml 1:1 solution of 10 M methylamine in ethanol and water for 12 h. The resulting mixture was then centrifuged and the supernatant was evaporated to dryness on a Speed Vac. After evaporation, the residue was redissolved in DMSO (100 μL) and TEA.3HF (150 μL). The resulting solution was heated at 65 °C for 2.5 h and slowly cooled to RT. The deprotected ON solution was lyophilized to dryness. The RNA ON residues was purified by 20% denaturing PAGE. The band corresponding to the full-length modified ON product was identified by UV shadowing, cut and transferred to a Poly-Prep column (Bio-Rad). The gel pieces were crushed with a sterile glass rod, and the ON was extracted using ammonium acetate buffer (0.5 M, 3 ml) for 12 h and desalted using a Sep-Pak classic C18 cartridge.

Steady-state fluorescence of RNA ONs and duplexes

RNA ONs (4, 9, 10 and 11) (0.5 μM) and the 1:1 mixture of RNA ONs (0.5 μM) and their respective complementary DNA sequences were heated at 90 °C for 3 min in sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.1) containing 500 mM NaCl. Samples were allowed to come to room temperature over a period of 2 h and kept at 4 °C for 1 h. Samples were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit width of 5 nm and 5 nm, respectively. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Fluorescence binding assay

Modified IRES subdomain IIa constructs (0.5 μM) were assembled by heating a 1:1 mixture of either 13 and 13c or 14 and 14c in sodium cacodylate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.5) at 75 °C for 4 min and allowing the mixtures to come to room temperature over a period of 1 h. 200 μL of IRES subdomain IIa construct (13•13c or 14•14c)(0.5 μM) was taken in a micro fluorescence cuvette (Hellma, path length 1.0 cm) and titrated by adding 1 μL of metal ion stock solutions of increasing concentration. After each addition the sample was incubated for 2 min and excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 3 nm and 4 nm, respectively. The changes in fluorescence intensity at respective emission maximum were calculated. The total volume change upon addition of metal ions during titration was ≤ 7%. The spectrum corresponding to a blank without any ON but containing the particular metal ion concentration was subtracted from each spectrum. A control titration where instead of metal ions, water was added to IRES constructs, did not show any detectable change in fluorescence intensity. Apparent dissociation constant (Kd) for the binding of metal ion (MgII or MnII) to respective IRES subdomain IIa constructs was determined by fitting normalized fluorescence intensity (FN) versus ligand concentration plot to equation 1 (Origin 8.5).68 All measurements were done in triplicate.

FN = normalized florescence intensity, Fi = florescence intensity at each titration point, F0 = fluorescence intensity in absence of metal ion, Fs = fluorescence intensity at saturation

Equation 1

[M] = metal ion concentration

19F NMR studies of modified model RNA ONs and IRES subdomain IIa

Single-stranded RNA ONs (4, 9, 10 and 11) (50 μM) and 1:1 mixture of RNA ONs and their respective complementary DNA sequences (4c, 9c, 10c and 11c) (50 μM) were heated at 90 °C for 3 min in sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.1) containing 500 mM NaCl and 20% D2O. The samples were slowly brought to room temperature over a period of 2 h and kept at 4 °C for 1 h before 19F NMR spectrum was recorded. In 19F studies of IRES subdomain IIa, the modified constructs (50 μM) were assembled by heating a 1:1 mixture of either 13 and 13c or 14 and 14c in sodium cacodylate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.5) containing 20% D2O at 75 °C for 4 min. The samples were cooled to room temperature over a period of 1 h and kept on an ice bath for 1 h. 19F NMR analysis of the assembled constructs were performed either in the presence or absence of 5 mM MgII. Spectra of ONs were recorded at a frequency of 564.9 MHz on a Bruker AVANCE III HD ASCEND 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with BB(F) Double Channel Probe at 298 K. The following spectral parameters were used43: 19F excitation pulse: 11 μs; spectral width: 21.28 ppm; transmitter frequency offset: -121.14 ppm; acquisition time: 80 ms; relaxation delay: 1.5 s and number of scans 28000. Each spectrum was processed with an exponential window function using lb = 10 Hz.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.M. is grateful UGC, India for a graduate research fellowship. V.A.S. is thankful to SERB-National Post-Doctoral Fellowship scheme (PDF/2016/003581) for the fellowship. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust-DBT India Alliance senior fellowship (IA/S/16/1/502360) to S.G.S., which is greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- (1).Tian B, Bevilacqua PC, Diegelman-Parente A, Mathews MB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:1013–1023. doi: 10.1038/nrm1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Serganov A, Patel DJ. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Dethoff EA, Chugh J, Mustoe AM, Al-Hashimi HM. Nature. 2012;482:322–330. doi: 10.1038/nature10885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Matthews MM, Thomas JM, Zheng Y, Tran K, Phelps KJ, Scott AI, Havel J, Fisher AJ, Beal PA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:426–433. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Barta A, Jantsch MF. RNA Biology. 2017;14:457–459. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1316929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Warner KD, Hajdin CE, Weeks KM. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:547–558. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Halvorsen M, Martin JS, Broadaway S, Laederach A. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Khalil AM, Rinn JL. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Okamoto A, Saito Y, Saito I. Photochem Rev. 2005;6:108–122. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Holzhauser C, Wagenknecht H-A. J Org Chem. 2013;78:7373–7379. doi: 10.1021/jo4010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wetmore SD, Maderville RA. Chem Sci. 2016;7:3482–3493. doi: 10.1039/c6sc00053c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Manna S, Srivatsan SG. RSC Adv. 2018;8:25673–25694. doi: 10.1039/c8ra03708f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Al-Hashimi HM, Walter NG. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Schnieders R, Knezic B, Zetzsche H, Sudakov A, Matzel T, Richter C, Hengesbach M, Schwalbe H, Fürtig B. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. 2020;82:e116. doi: 10.1002/cpnc.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bardaro MF, Varani G. WIREs RNA. 2012;3:122–132. doi: 10.1002/wrna.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Schiemann O, Weber A, Edwards TE, Prisner TF, Sigurdsson ST. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3434–3435. doi: 10.1021/ja0274610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sicoli G, Wachowius F, Bennati M, Höbartner C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:6443–6447. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Mooers BHM. Methods. 2009;47:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Peselis A, Gao A, Serganov A. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1320:21–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2763-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wilhelmsson LM. Q Rev Biophys. 2010;43:159–183. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Srivatsan SG, Sawant AA. Pure Appl Chem. 2011;83:213–232. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Xu W, Chan KM, Kool ET. 2017;9:1043–1055. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Manna S, Srivatsan SG. Org Lett. 2019;21:4646–4650. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).George JT, Srivatsan SG. Chem Commun. 2021;56:12319–12322. doi: 10.1039/d0cc05092j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Michel BY, Dziuba D, Benhida R, Demchenko AP, Burger A. Front Chem. 2020;21:112. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Phan AT, Patel DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1160–1161. doi: 10.1021/ja011977m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Becette O, Olenginski LT, Dayie TK. Molecules. 2019;24:3476. doi: 10.3390/molecules24193476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Chen H, Viel S, Ziarelli F, Peng L. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:7971–7982. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60129c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hammann C, Norman DG, Lilley DM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5503–5508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091097498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Olejniczak M, Gdaniec Z, Fischer A, Grabarkiewicz T, Bielecki L, Adamiak RW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4241–4249. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Olsen GL, Edwards TE, Deka P, Varani G, Sigurdsson ST, Drobny GP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3447–3454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Granqvist L, Virta P. J Org Chem. 2015;80:7961–7970. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Li Q, Chen J, Trajkovski M, Zhou Y, Fan C, Lu K, Tang P, Su X, Plavec J, Xi Z, Zhou C. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142(10):4739–4748. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b13207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Baranowski MR, Warminski M, Jemielity J, Kowalska J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:8209–8224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kreutz C, Kahlig H, Konrat R, Micura R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3450–3453. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lombés T, Moumné R, Larue V, Prost E, Catala M, Lecourt T, Dardel F, Micouin L, Tisné C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:9530–9534. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Kiviniemi A, Virta P. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8560–8562. doi: 10.1021/ja1014629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Sakamoto T, Hasegawaa D, Fujimoto K. Analyst. 2016;141:1214–1217. doi: 10.1039/c5an02389k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kieger A, Wiester MJ, Procissi D, Parrish TB, Mirkin CA, Thaxton CS. Small. 2011;14:1977–1981. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Dempsey ME, Marble HD, Shen T-L, Fawzi NL, Darling EM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018;29:335–342. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Olszewska A, Pohl R, Hocek M. J Org Chem. 2017;82:11431–11439. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bao H-L, Masuzawa T, Oyoshi T, Xu Y. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:7041–7051. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Bao H-L, Liu H-S, Xu Y. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:4940–4947. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Bao H-L, Xu Y. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:652–665. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Riedl J, Pohl R, Rulíšek L, Hocek M. J Org Chem. 2012;77:1026–1044. doi: 10.1021/jo202321g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Sakamoto T, Hasegawaa D, Fujimoto K. Chem Commun. 2015;51:8749. doi: 10.1039/c5cc01995h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Sakamoto T, Hasegawa D, Fujimoto K. Org Biomol Chem. 2018;16:7157–7162. doi: 10.1039/c8ob02218f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Pawar MG, Nuthanakanti A, Srivatsan SG. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013;24:1367–1377. doi: 10.1021/bc400194g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Nuthanakanti A, Boerneke MA, Hermann T, Srivatsan SG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:2640–2644. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Nuthanakanti A, Ahmed I, Khatik SY, Saikrishnan K, Srivatsan SG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:6059–6072. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Manna S, Sarkar D, Srivatsan SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:12622–12633. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Reichardt C. Chem Rev. 1994;94:2319–2358. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Sinkeldam RW, Wheat AJ, Boyaci H, Tor Y. ChemPhysChem. 2011;12:567–570. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201001002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Giam CS, Lyle JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:3235–3239. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Jean JM, Hall KB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:37–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011442198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Doose S, Neuweiler H, Sauer M. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10:1389–1398. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Wee WA, Yum JH, Hirashima S, Sugiyama H, Park S. RSC Chem Biol. 2021;2:876–882. doi: 10.1039/d1cb00020a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Iizuka N, Kohara M, Nomoto A. J Virol. 1992;66:1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1476-1483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Spahn CMT, Kieft JS, Grassucci RA, Penczek PA, Zhou K, Doudna JA, Frank J. Science. 2001;291:1959–1962. doi: 10.1126/science.1058409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Otto GA, Puglisi JD. Cell. 2004;119:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Kieft JS, Zhou K, Jubin R, Murray MG, Lau JY, Doudna JA. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:513–529. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Dibrov SM, Parsons J, Carnevali M, Zhou S, Rynearson KD, Ding K, Sega EG, Brunn ND, Boerneke MA, Castaldi MP, Hermann T. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1694–1707. doi: 10.1021/jm401312n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Filbin ME, Kieft JS. RNA. 2011;17:1258–1273. doi: 10.1261/rna.2594011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Locker N, Easton LE, Lukavsky PJ. EMBO J. 2007;26:795–805. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Pestova TV, Breyne S, Pisarev AV, Abaeva IS, Hellen CU. EMBO J. 2008;27:1060–1072. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Lukavsky PJ, Kim I, Otto GA, Puglisi JD. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nsb1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Dibrov SM, Johnston-Cox H, Weng YH, Hermann T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;46:226–229. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Parsons J, Castaldi MP, Dutta S, Dibrov SM, Wyles DL, Hermann T. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:823–825. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Dibrov SM, Ding K, Brunn ND, Parker MA, Bergdahl BM, Wyles DL, Hermann T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5223–5228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118699109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Zhao Q, Han Q, Kissinger CR, Hermann T, Thompson PA. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;D64:436–443. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Paulsen RB, Seth PP, Swayze EE, Griffey RH, Skalicky JJ, Cheatham TE, Davis DR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7263–7268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911896107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Poster MP, McElroy CA, Amero CD. Biochemistry. 2007;46:331–340. doi: 10.1021/bi0621314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Fery-Forgues SJ, Lavabre D. Chem Educ. 1999;76:1260–1264. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Tanpure AA, Srivatsan SG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.