Abstract

An intriguing notion in cognitive neuroscience posits that alpha oscillations mould how the brain parses the constant influx of sensory signals into discrete perceptual events. Yet, the evidence is controversial and the underlying neural mechanism unclear. Further, it is unknown whether alpha oscillations influence observers’ perceptual sensitivity (i.e. temporal resolution) or their top-down biases to bind signals within and across the senses. Combining EEG, psychophysics and signal detection theory, this multi-day study rigorously assessed the impact of alpha frequency on temporal binding of signals within and across the senses. In a series of two-flash discrimination experiments twenty human observers were presented with one or two flashes together with none, one or two sounds. Our results provide robust evidence that pre-stimulus alpha frequency as a dynamic neural state and an individual’s trait index does not influence observers’ perceptual sensitivity or bias for two-flash discrimination in any of the three sensory contexts. These results challenge the notion that alpha oscillations have a profound impact on how observers parse sensory inputs into discrete perceptual events.

In everyday life our senses are exposed to a constant influx of sensory signals. To form a coherent percept the brain needs to bind signals that arise from a common event and treat signals separately from different events1–7. Temporal synchrony is a critical cue for solving this binding problem8–11. While signals do not have to be precisely synchronous, they need to co-occur within a temporal binding window12,13. A fundamental, as yet unresolved question is how the brain instantiates this temporal binding window. How does it decide whether signals should be bound or segregated?

Since the middle of the 20th century, scientists have proposed that alpha oscillations (6-14 Hz) play a critical role in parsing visual inputs into discrete events14–21: Two flashes are thought to be perceived as a single event if they occur within one alpha cycle, but as separate events if they fall into separate cycles (Figure 1b). As a result, the phase and frequency of alpha oscillations should mould temporal binding. Consistent with a modulatory role of alpha oscillations in visual perception, previous research has shown that the detectability of visual signals at perceptual threshold22–24, their perceived timing25,26 and the emergence of perceptual illusions5,27 depend on the phase of alpha oscillations. In invasive neurophysiological recordings alpha activity has also been shown to modulate neuronal firing rates (e.g.28,29).

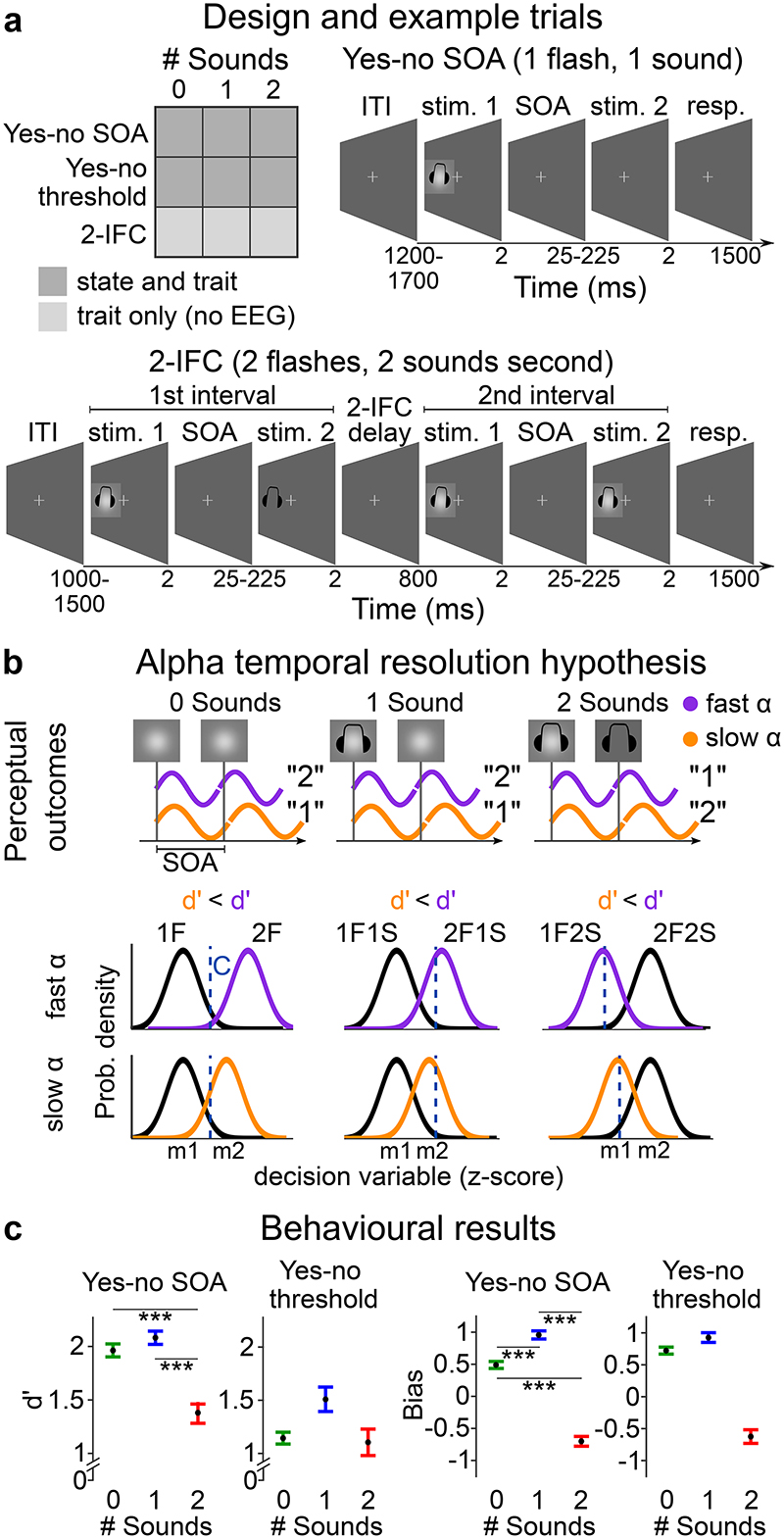

Figure 1. Experimental design, example trials, alpha frequency predictions and behavioural results.

a, Study design and example trials. The study design manipulates i. the sensory context ‘# Sounds’: one or two flashes were presented with none, one or two sounds and ii. experimental paradigm: ‘yes-no SOA’, ‘yes-no threshold’ and ‘2IFC’ design. Example trials: In the ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments, observers were presented within a single interval with either one or two flashes (together with zero, one or two sounds). They reported whether they perceived one or two flashes (followed by a confidence judgement that is not included in this report).

In the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment, the SOAs between the two flashes (or two sounds) varied (i.e. 25, 42, 50, 58, 75, 108, 158, 225 ms) to enable the estimation of psychometric functions. In the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment, the SOAs between the two flashes (or sounds) were titrated individually for each participant to yield approximately 50% “One flash” and 50% “two flash” responses for each of the following stimulus combinations: ‘2 flash + 0 sound’; ‘2 flash + 1 sound’; ‘1 flash + 2 sound’.

In the ‘2IFC’ experiment, observers were presented on each trial in one interval with a probe (e.g. ‘2 flash + x sound’) and in the other interval with a standard (e.g. ‘1 flash + x sound’). They reported which interval contained the probe (i.e. ‘2 flash’ stimulus). b, Alpha temporal resolution hypothesis16,18,30,48. Two sensory inputs are bound into one event if they fall within the same alpha cycle, but as two separate events, if they fall into different cycles. As a result, observers should be less sensitive at discriminating between one and two flashes for lower alpha frequency in purely visual perception. In audiovisual perception, audiovisual interactions or more specifically the influence of an incongruent number of sounds on the perceived number of flashes should be greater for lower alpha frequency leading to stronger crossmodal biases. Observers should be more likely to experience fusion illusions (i.e. perceive two flashes as one flash) when two flashes are paired with one sound and more fission illusions (i.e. perceive one flash as two flashes) when one flash is paired with two sounds. These audiovisual perceptual illusions introduce audiovisual biases and may reduce observers’ sensitivity to discriminate between one and two flashes for lower alpha frequency. c, Behavioural results. Perceptual sensitivity (d’ = z(HR) – z(FAR)) and bias (Biascentre= -0.5(z(HR) + z(FAR))) for ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments for each auditory context (irrespective of alpha frequency). In the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment differences in perceptual sensitivity and bias between sensory contexts cannot be interpreted, because the SOAs differed between no sound, one sound and two sound contexts. Error bars represent 1 SEM. SEM, Standard error of the mean after Bonferroni-Holm correction (per task for d’ or Biascentre). Detailed statistics and effect sizes are in Supplementary Table 3.

Recent influential studies have instigated interest in the role of alpha frequency in temporal parsing by showing a correlation30,31 and even causal influence32 of the frequency of alpha oscillations on observers’ tendency to bind signals within and across the senses.

In a unisensory visual flash discrimination paradigm30, a lower two-flash-fusion threshold was associated with a higher trait alpha frequency across participants. Additional within-participant analyses showed that pre-stimulus alpha frequency was higher for correct than incorrect flash discrimination: observers were more likely to perceive two flashes when presented with two flashes and one flash when presented one flash. By contrast, in audiovisual double flash illusion paradigms33–35, lower trait alpha frequency from peri-stimulus EEG was associated with a broader illusion window, i.e. more illusory “two flash” reports31,32,36.

How can we reconcile that higher alpha frequency is associated with more two flash percepts (on two flash trials) in unisensory visual perception, but with less two flash percepts (on one flash with two sound trials) in audiovisual perception? From a computational perspective of normative Bayesian causal inference, the brain needs to solve two computational challenges in perceptual inference: First, it needs to determine whether signals come from common or separate sources 1,3–6. Second, when signals come from a common source, the brain needs to integrate them weighted by their sensory reliabilities (or precision, i.e. inverse of uncertainty) with a greater weight assigned to the more reliable signal37–39. Alpha frequency may affect this perceptual inference process via changes in priors or sensory representations.

First, higher alpha frequency may decrease observers’ binding prior, i.e. their prior tendency to bind sensory signals within and across the senses. As a result, observers would be less likely to fuse two flash inputs into a “one flash” percept in visual perception. In audiovisual perception, it would decrease audiovisual binding and thus the experience of the double flash illusion on one flash with two sound trials.

Second and more importantly, higher alpha frequency when measured over occipital cortices may increase the temporal precision of sensory and particularly visual inputs. This greater temporal precision would enable the brain to arbitrate more reliably between sensory integration and segregation as a function of stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) leading to more within and cross-sensory binding for synchronous signals and less binding for asynchronous signals. Hence, observers would be more likely to perceive two asynchronous flashes as separate events in visual perception. Further, they would be less likely to experience the double flash illusion in audiovisual perception. Moreover, if occipital alpha frequency influences mainly visual precision, observers should also give a stronger weight to the visual signal in audiovisual perception – again reducing the occurrence of double flash illusions. In short, an increase in visual precision can influence observers’ percept via two intimately related mechanisms, namely sharpening of temporal binding within and across the senses and reliability-weighting of the sensory inputs in audiovisual perception40.

Even though alpha frequency has been linked recurrently with temporal resolution19,20,30–32,41, prior expectations or top-down biases41–43 in across-trial analyses, none of those previous studies have formally dissociated effects of alpha frequency on sensitivity (d’) and bias (Biascentre) within a signal detection theory44 framework (see e.g.45). Likewise, the thresholds obtained from psychometric functions in previous between-participant analyses could not unambiguously be interpreted as an index of perceptual sensitivity30,32.

The distinction between sensitivity and bias is important, because it may implicate different neural mechanisms: Perceptual sensitivity is associated with a sensory system’s temporal resolution or precision. It enables observers to discriminate more reliably between, for instance, one and two flashes. By contrast, biases towards one particular perceptual outcome (e.g. “two flash” reports) can arise from numerous mechanisms46. Most notably, top-down prior expectations may bias observers towards one particular percept. Biases may also reflect changes in observers’ cost functions. For instance, observers may shift their criterion depending on whether they consider misses (e.g. two flashes reported as one flash) or false alarms (e.g. one flash reported as two flashes) more detrimental. Finally, as explained above, in multisensory contexts, biases in modality-selective reports (e.g. flash discrimination) can also result from sensory-driven mechanisms of reliability-weighted integration1,3–5,37–39,47. Most notably, reliability-weighted integration can explain that observers are biased to perceive two flashes when presented with one flash and two beeps (i.e. double flash illusion) and one flash when presented with two flashes and one beep (i.e. fusion illusion, see Figure 1)47.

This study investigated whether alpha frequency is a key determinant of temporal binding within and across the senses in an extensive five-day series of psychophysics and EEG experiments. To dissociate changes in sensitivity (d’) as an index for visual temporal resolution from bias (Biascentre), we combined yes-no and two-interval forced-choice paradigms with signal detection theory. In a two-flash discrimination task, we presented 20 human observers with one or two flashes together with no sound, one sound, or two sounds. According to the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis16,18,30,48 greater alpha frequency over occipital cortices should increase the temporal precision particularly of the visual inputs. Thus, at high alpha frequency, observers should have a greater sensitivity (d’) to discriminate between one and two flashes irrespective of the number of sounds (Figure 1b). In addition, higher occipital alpha frequency should reduce audiovisual interactions and increase the visual weight in perceptual inference leading to reduced crossmodal biases (i.e. fission and fusion illusions). We first assessed the influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency as a dynamic neural state index on observers’ perception across trials. We then investigated the influence of pre-stimulus and resting state alpha peak frequency as individual trait indices on perceptual inference in between-observer analyses.

Results

Pre-stimulus alpha frequency as dynamic neural state index

We assessed the influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency as a dynamic neural state index on perceptual sensitivity and bias in visual and audiovisual perception in two EEG experiments (‘yes-no SOA’, ‘yes-no threshold’). In both experiments, observers were presented on each trial with one or two flashes in a single interval together with none, one (i.e. ‘fusion illusion’) or two sounds (i.e. ‘fission illusion’). Observers reported whether they perceived one or two flashes irrespective of the number of sounds (see Figure 1a and legend for further information).

In the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment the stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) of the two flashes or sounds varied across trials32 from 25 ms to 225 ms. For the analysis of pre-stimulus alpha frequency as a neural state index, we focused selectively on trials with intermediate SOAs (i.e. 50, 58, 75, 108 ms) that were associated with comparable percentages of “one flash” and “two flash” percepts.

In the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment we adjusted the SOA of the two flashes or sounds individually for each participant to match their “one flash” and “two flash” percepts independently for the stimulus combinations: ‘2 flash + 0 sound’; ‘2 flash + 1 sound’; ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ (see methods for details).

Perceptual sensitivity and bias across sensory contexts

Our behavioural results show that the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment at intermediate SOAs and particularly the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment successfully lowered observer’s ability to discriminate between one flash and two flashes (see Figure 1c). The across-participants’ mean d’ was between 1 and 2 in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment and between 1 and 1.5 in the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment - thereby maximizing our chances to unravel even small modulatory influences of alpha frequency on observers’ perceptual inference.

We assessed the influence of sound stimuli on observers’ flash discrimination performance by directly comparing both perceptual sensitivity and bias across the ‘0 sound’, ‘1 sound’ and ‘2 sound’ contexts. We performed statistical comparisons only for the intermediate SOAs of the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment. For the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment, this statistical comparison is not meaningful, because the SOAs were separately adjusted for the different sound contexts (see above, Supplementary Table 2).

Consistent with a large body of psychophysics research, observers experienced the sound-induced fission illusion, when one flash was paired with two sounds and the fusion illusion when two flashes were paired with one sound5,33–35,49. In the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment observers perceived one flash as two flashes on 9.4% (SEM: 0.02%) of the trials in a purely visual context, but on 50% (SEM: 0.07%) of the trials when a single flash was paired with two sounds. From the perspective of signal detection theory, this double flash illusion significantly reduced observers’ perceptual sensitivity [d’ = z(hit rate) – z(false alarm rate)], i.e. the distance between the one flash and two flash distributions for the ‘2 sound’ relative to the ‘0 sound’ context. Moreover, because observers were more likely to report two flashes when one flash was paired with two sounds, we observed a negative bias [Biascentre =- 0.5(z(hit rate) + z(false alarm rate)] (Supplementary Table 3).

Conversely, observers perceived two flashes as one flash on 37.5% (SEM: 0.05%) of trials in a purely visual context, but on 47.7% (SEM: 0.05%) of trials when two flashes were paired with one sound. This fusion illusion induced a significant positive bias for the ‘1 sound’ relative to the ‘0 sound’ context, but no change in perceptual sensitivity (for detailed statistics see Figure 1c and Supplementary Table 3). The absence of a significant effect on sensitivity can be explained by the lower number of “two flash” reports on the ‘1 flash + 1 sound’ trials (0.04% ± 0.01% SEM). It is important to emphasize that these crossmodal biases (or shifts in criterion) result from observers integrating auditory and visual signals into perceptual estimates3,33,37,–40,47.

Collectively, the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment demonstrated profound influences of concurrent sounds on observers’ two flash discrimination performance. While the double flash illusion strongly affected observers’ perceptual sensitivity, the fusion illusion was associated with a change in observers’ bias. These behavioural results raise the critical question whether and how alpha frequency modulates observers’ temporal binding of sensory inputs within and across the senses and thereby their flash discrimination performance. Does high alpha frequency increase perceptual sensitivity and attenuate crossmodal biases?

Alpha frequency influence on perceptual sensitivity or bias

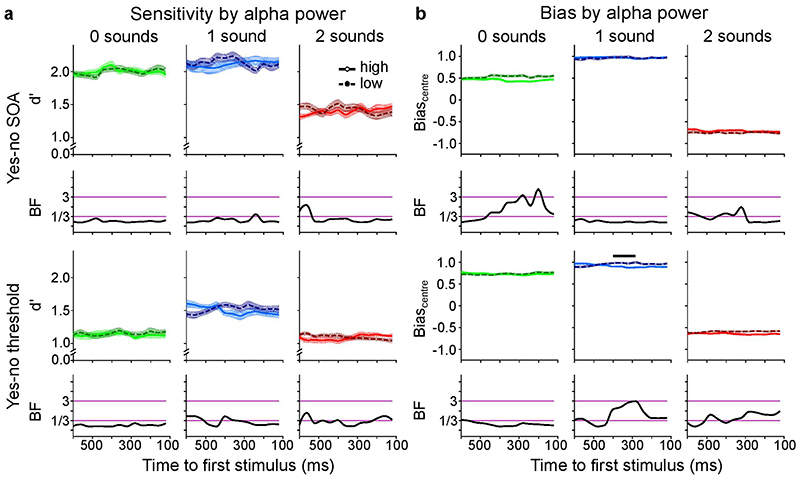

To address this question, we combined EEG with psychophysics and signal detection theory. We assessed the influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on perceptual sensitivity (d’) and bias (Biascentre) in the ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments. We ranked trials and assigned them to terciles according to their pre-stimulus alpha frequency averaged over channels O2, PO4 and PO8. We compared perceptual sensitivity and bias that were computed from trials of the first and third terciles using cluster-based randomization tests (time resolved) or paired t-tests (time collapsed). We also assessed evidence for the null- and alternative hypothesis using Bayes factors (see methods).

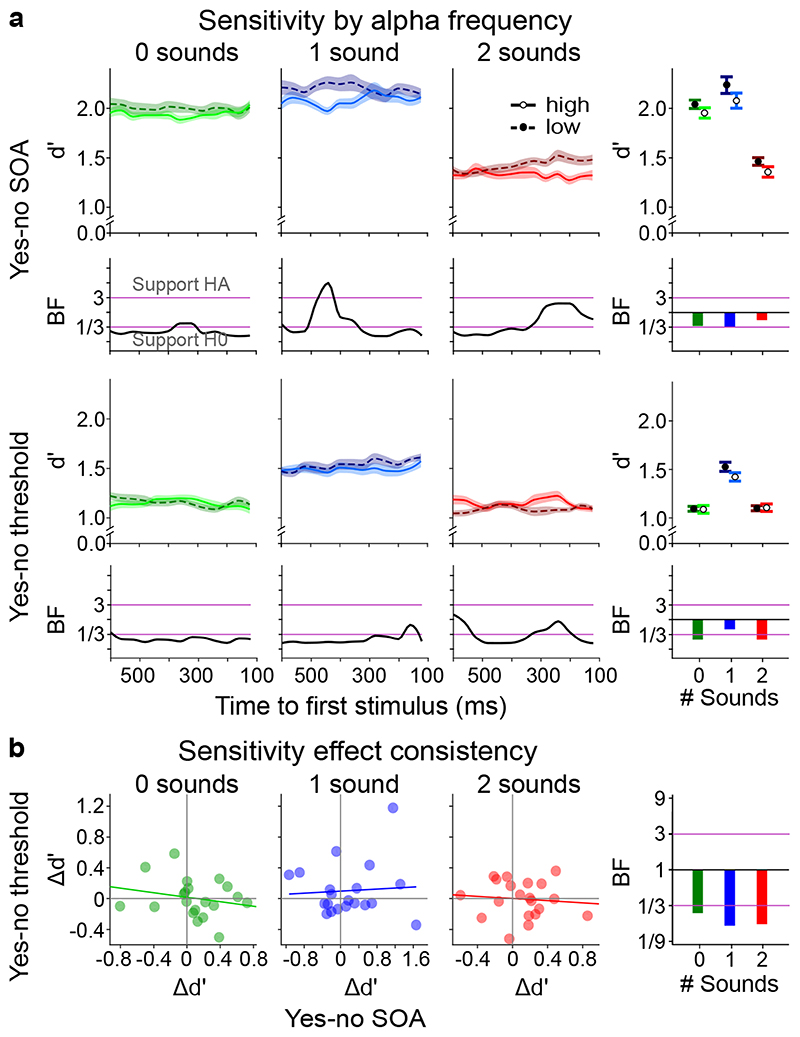

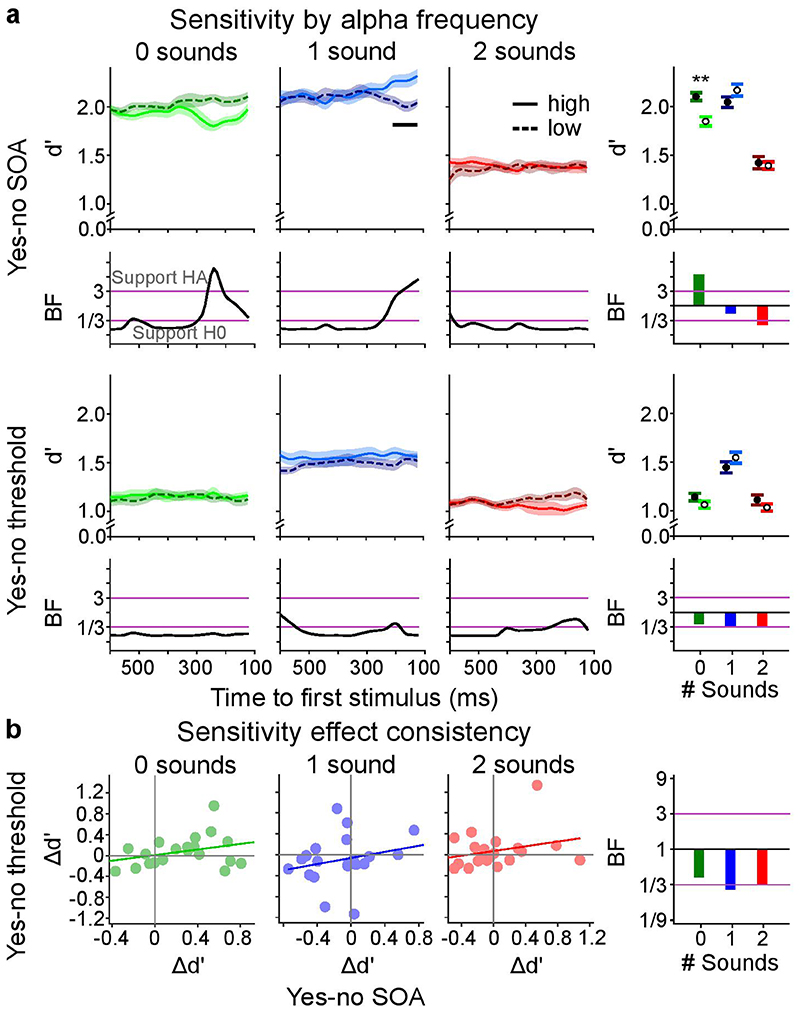

None of the tests revealed significant differences in perceptual sensitivity between the first and third terciles in any of the three sensory contexts of the ‘yes-no SOA’ or the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment for the time-resolved or the time collapsed analysis (Figure 2a, Supplementary Table 5). Further, none of the trends were replicated across the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments (Figure 2a). Instead, non-significant differences between terciles in the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment were reversed in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment and vice versa (e.g. see ‘2 sound’ condition in Figure 2a). Likewise, Bayes factors (BFs) collapsed across time supported H0. In the time-resolved analysis, the only difference that was associated with Bayes Factors > 3 for the ‘1 sound’ context in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment was exactly opposite to the predictions of the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis: we observed greater perceptual sensitivity for low relative to high alpha frequency. The corresponding analyses performed for bias revealed no significant effects of alpha frequency either (Figure 3a, Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 2. The influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on d’ (cf. Supplementary Tables 5, 7).

a, Perceptual sensitivity (across-participants’ mean ± 1 within-subject SEM) is shown for low (1st tercile, dashed) and high (3rd tercile, solid) pre-stimulus alpha frequency across pre-stimulus time for the 2 experimental designs (rows: (i) yes-no, (ii) ‘yes-no threshold’) x 3 sensory contexts (columns: no sound, one sound, two sounds). The right most column shows results where instantaneous frequency estimates were averaged over time. We observed no significant effect of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on perceptual sensitivity in any of the experiments (all p > 0.05; columns 1-3, two-sided cluster randomization tests, column 4, paired t-tests). Bayes factors (BF) indexing the evidence for HA relative to H0 are shown on a log10-scaled ordinate. Purple lines indicate thresholds for at least moderate evidence favouring H0 (< 1/3) or Ha (> 3)77. b, Within subject consistency of perceptual sensitivity relationship with alpha frequency over tasks. The difference in sensitivity between low and high alpha frequency (Δd’ = d’low – d’high) was not significantly correlated between the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment over participants for any sensory context. SEM, Standard error of the mean.

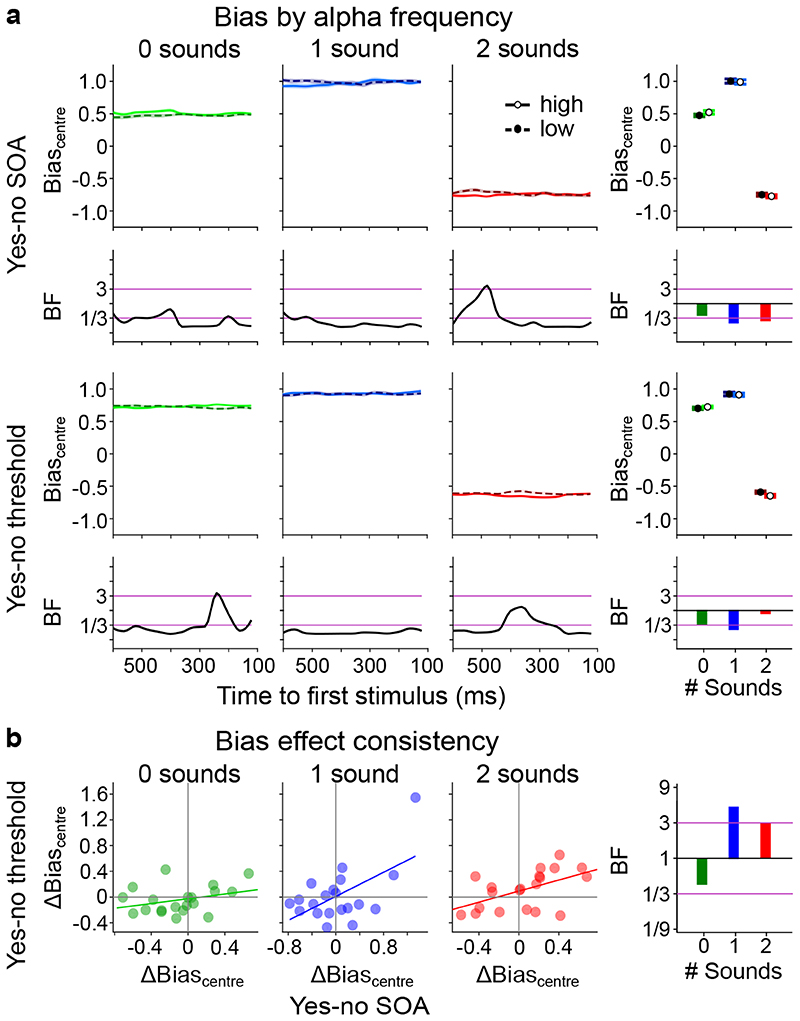

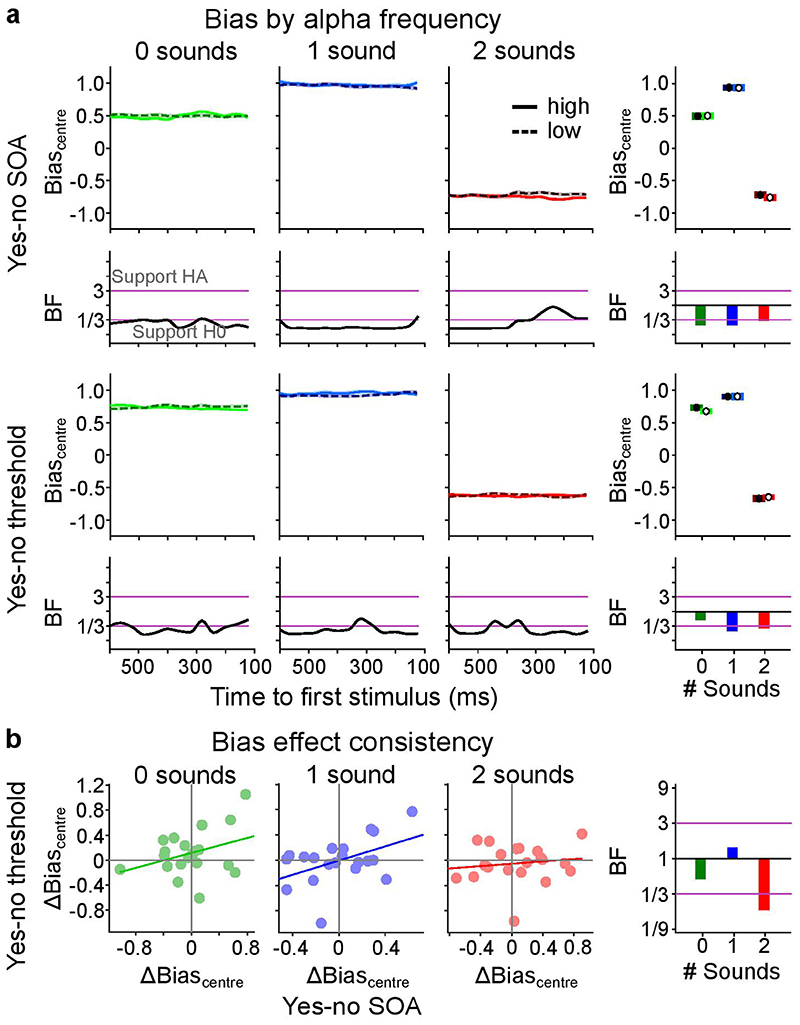

Figure 3. The influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on Biascentre (cf. Supplementary Tables 6, 7).

a, Bias (across-participants’ mean ± 1 within-subject SEM) is shown for low (1st tercile, dashed) and high (3rd tercile, solid) pre-stimulus alpha frequency across pre-stimulus time for 2 experimental designs (rows: (i) ‘yes-no SOA’, (ii) ‘yes-no threshold’) x 3 sensory contexts (columns: no sound, one sound, two sounds). The right most column depicts results where instantaneous frequency estimates were averaged over time. We observed no significant effect of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on bias in any of the experiments (all p > 0.05). Bayes factors (BF) indexing the evidence for HA relative to H0 are shown on a log10-scaled ordinate. Purple lines indicate thresholds for at least moderate evidence favouring H0 (< 1/3) or Ha (> 3)77. b, Within subject consistency of bias relationship with alpha frequency over tasks. The difference in bias between low and high alpha frequency (Δbias = biaslow – biashigh) was significantly correlated between the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment only in the ‘1 sound’ and ‘2 sound’ sensory context (see Supplementary Table 7). SEM, Standard error of the mean.

To investigate whether these null-findings result from inter-subject variability, we assessed whether the impact of alpha frequency on d’ or Biascentre was consistent between the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment separately for each sensory context. Contrary to this conjecture, the differences in temporal sensitivity between high and low alpha frequency terciles (Δd’ = d’tercile1 – d’tercile3) were not correlated between ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments (Figure 2b, Supplementary Table 7). The difference in bias (Δbias = biastercile1 – biastercile3) between low and high alpha frequency was significantly correlated between the ‘yes-no’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment over participants in the ‘1 sound’ (r(18) = 0.569, p = 0.001, 95% CI = [0.169, 0.808]) and ‘2 sound’ (r(18) = 0.529, p = 0.016, 95% CI = [0.113, 0.787]) sensory contexts. This raises the question whether the relationship between alpha frequency and bias is positive for some participants but negative for others. If this were the case, we should be able to predict the participant-specific sign of the effect in the ‘yes-no threshold ‘ experiment from the effect’s sign in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment.

As a follow up analysis, we therefore determined the sign of the alpha frequency effect on Biascentre for each participant in one experiment and applied it to the effects observed in the other experiment before entering it into the time-collapsed analysis. In the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment, there was no significant effect for either one sound or two-sound contexts (‘1 sound ’: t(19) = 1.418, p = 0.172, d = 0.065, 95% CI = [-0.038, 0.197], BF = 0.552; ‘2 sound’: t(19) = 1.902, p = 0.072, d = 0.069, 95% CI = [-0.007, 0.151], BF = 1.043). In the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment, there was a small significant effect in the ‘2 sound’ condition. But the Bayes factors provided less than moderate evidence (‘1 sound’: t(19) = 1.377, p = 0.184, d = 0.060, 95% CI = [-0.033, 0.161], BF = 0.527; ‘2 sound’: t(19) = 2.453, p = 0.024, d = 0.077, 95% CI = [0.011, 0.141], BF = 2.494).

We repeated our analyses in source space to focus on alpha sources in occipital cortices (Supplementary methods 1, Supplementary Figures 2 and 3, Supplementary Tables 10-12). Out of these 30 tests, we observed a strongly significant effect of alpha frequency on d’ that was opposite to the prediction of the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis and a brief subtle effect in the predicted direction that did not replicate across experiments. Please also see supplementary material for further control analyses assessing i. the effect of alpha frequency at high and low pre-stimulus alpha power, ii. the effect of pre-stimulus alpha power on d’ and Biascentre and iii. comparing pre-stimulus alpha frequency for “one flash” and “two flash” perceptual outcomes.

Alpha peak frequency as an individual’s trait index

Alpha frequency has been proposed to influence the temporal resolution of a perceptual system not only dynamically over trials, but also as an individual’s trait index30–32. To assess this hypothesis previous research has quantified the temporal resolution (or temporal binding window) of observers’ perceptual system in terms of a psychometric function’s ‘threshold’ (i.e., inflection point) in single interval yes-no paradigms. However, in single interval yes-no paradigms a psychometric function’s threshold can be affected by changes in perceptual sensitivity (i.e. temporal resolution) as well as shifts in criterion44. In order to interpret a psychometric function’s threshold as temporal resolution unconfounded by changes in bias we need to use two-interval-forced-choice paradigms that enable the interpretation of performance accuracy as a proxy for perceptual sensitivity (in the absence of interval biases44).

To obtain an estimate of observers’ temporal resolution as a trait index, we performed a third, purely psychophysics experiment, in which we presented observers with one or two flashes in a two-interval forced-choice paradigm. On each trial, observers indicated which of the two successive intervals contained two flashes. We assessed whether observers had any interval biases that would hamper a conclusive interpretation of threshold as an index for temporal resolution. There was no significant interval bias in any of the sensory contexts (zero sounds: t(19) = 1.503, p = 0.149, d = 0.336, 95% CI = [-0.038, 0.234]; one sound: t(19) = 1.709, p = 0.104, d = 0.382, 95% CI = [-0.034, 0.336]; two sounds: t(19) = -0.060, p = 0.952, d = 0.014, 95% CI = [-0.185, 0.174]).

Next, we obtained the threshold from the psychometric function in the ‘2IFC’ experiment as an index for observers’ temporal binding window. Further, we estimated observers’ trait alpha frequency from pre-stimulus (i.e. with ‘eyes-open’) and resting state EEG that was recorded in separate ‘eyes-closed’ runs. Crucially, we discarded psychometric functions of observers based on objective experimenter-independent goodness-of-fit tests50. Likewise, peak alpha trait frequency was obtained with an experimenter-independent peak fitting algorithm51.

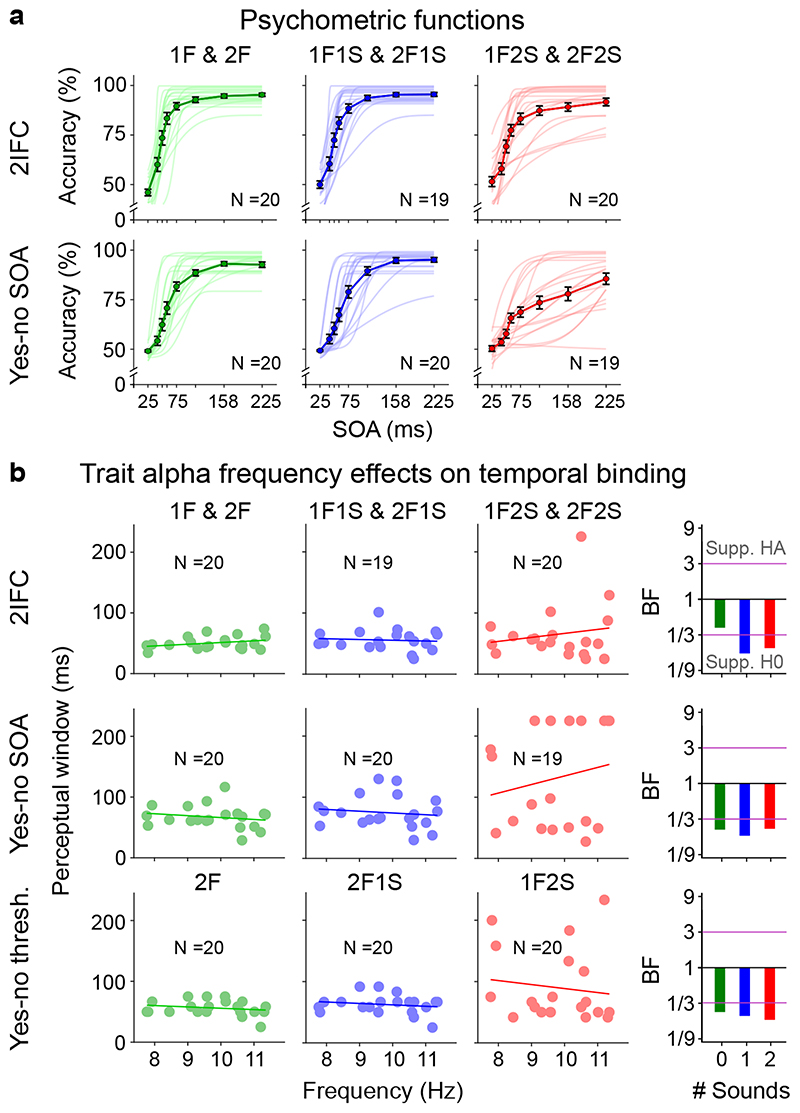

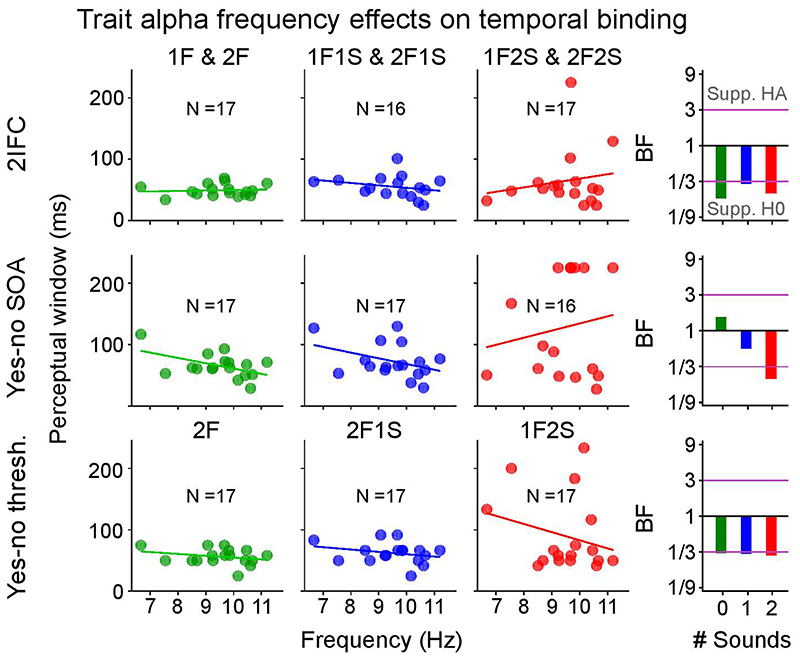

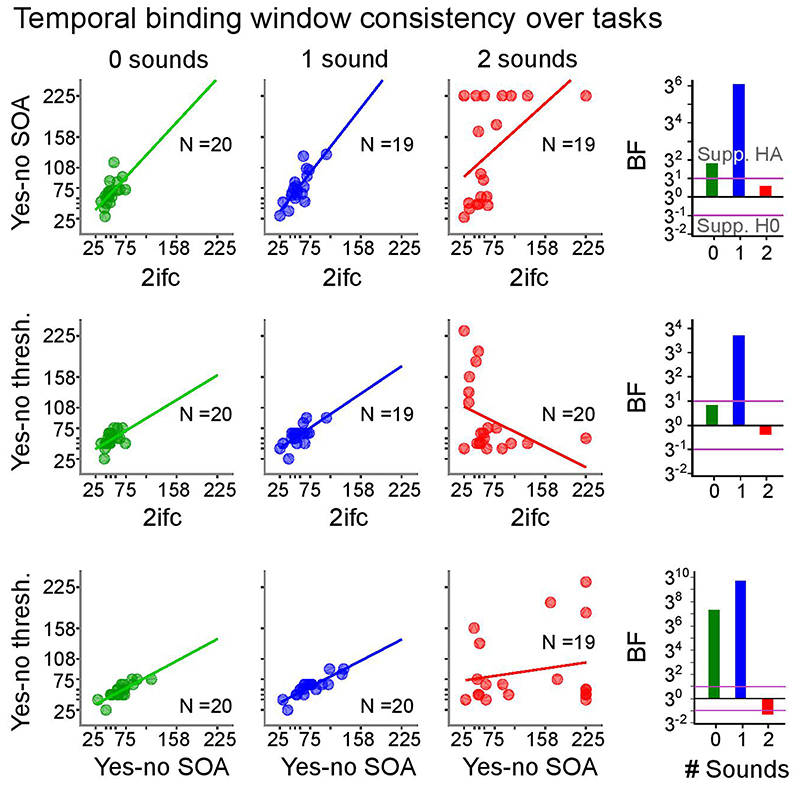

As shown in Figure 4b we observed no significant correlations between observers’ alpha peak frequency and their perceptual thresholds in any of the three sensory contexts for the ‘2IFC’ experiment (see Supplementary Table 13 for detailed statistics). Moreover, Bayes factors showed strong support for H0 for the ‘1 sound’ and ‘2 sound’ contexts. For the purely visual context, we observed non-conclusive evidence for the null-hypothesis based on Bayes factors; yet, even in this case the correlation coefficient was positive, i.e., opposite to the predictions of the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis.

Figure 4. Psychometric functions and trait alpha peak frequency correlations with perceptual threshold (cf. Supplementary Table 13).

a, Grand average response accuracies (markers, bold lines) and single subject psychometric functions (thin lines) for the ‘2IFC’, ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments. Error bars denote ± 1 SEM. N = number of participants with psychometric functions that passed the objective goodness of fit test. b, Pre-stimulus trait alpha frequency correlations with temporal binding window estimates obtained from each experiment. In the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment the binding window size is given as the asynchrony yielding approximately 50% performance accuracy for ‘2 flash + 0 sound’, ‘2 flash + 1 sound’, and ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ trials. The alpha temporal resolution hypothesis, based on previous studies, predicts a negative correlation between alpha frequency and temporal binding window length30–32. Bayes factors (BF) indexing the evidence for HA relative to H0 are shown on a log10-scaled ordinate. Purple lines indicate thresholds for at least moderate evidence favouring H0 (< 1/3) or Ha (> 3)77. Eight out of nine Bayes factors consistently provide at least moderate evidence for the null-hypothesis of no correlation between trait alpha frequency and temporal binding window. SEM, Standard error of the mean.

For comparison with past research30–32, we also estimated observers’ thresholds from psychometric functions in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment and based on the adaptive staircases in the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment, even though neither of the two can be unambiguously interpreted as temporal resolution. Further, we observed substantial inter-subject variability in the behavioural profile for the ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ condition (i.e. double flash illusion trials). In a substantial number of participants, the double flash illusion did not decrease with growing SOA or the threshold was estimated at the bounds thereby putting their estimation reliability for the ‘2 flash + 1 sound’ condition from the yes-no experiments into question (for further discussion see Supplementary Figure 7 legend assessing the relationship between thresholds obtained from the ‘yes-no SOA’, ‘yes-no-threshold’ and ‘2IFC’ experiments).

Consistent with our results from the ‘2IFC’ experiment, Bayes factors provided at least moderate support for no correlation between either of the two thresholds (i.e. from the ‘yes-no SOA’ or the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment) with alpha trait frequency in any of the three sensory contexts (Figure 4b; Supplementary Table 13). Likewise, equivalent analyses with alpha trait frequency estimated from ‘eyes-closed’ EEG or from source-reconstructed EEG provided strong evidence for the null-hypothesis (Supplementary Tables 13 and 15).

Comparable results were also obtained when estimating alpha peak frequency only over medial and contralateral channels relative to the visual stimulus. Again, there were no significant correlations, and 15 out of 18 tests substantially supported the null hypothesis (Supplementary Table 14).

In summary, Bayes factors provided robust support for the absence of a correlation between observer’s alpha trait frequency and perceptual threshold irrespective of whether this threshold reflects sensitivity and/or biases in temporal binding.

Discussion

Recent influential research has triggered a surge of interest in the intriguing notion that alpha frequency moulds how human observers parse the constant inflow of sensory inputs into discrete perceptual events. Longer alpha cycles have been associated with lower temporal resolution leading to more fusion of two flashes into a single event in visual perception and more double flash illusions in audiovisual perception30–32. Yet, previous research used experimental designs and/or analyses that could not unambiguously dissociate alpha frequency effects on perceptual sensitivity and bias.

In this study, we have tested the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis rigorously in a five-day series of experiments in which we presented observers with one or two flashes together with none, one or two sounds. To protect ourselves against spurious false positives we studied the role of alpha frequency in each sensory context across three experiments: i. ‘yes-no SOA’, ii. ‘yes-no threshold’ and iii. ‘2IFC’ (two-interval forced-choice). Further, we designed and analysed our experiments within a signal detection theory framework that enables the dissociation of changes in temporal resolution (i.e. perceptual sensitivity) from bias.

Overall, our results did not show a reliable influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on d’ or Biascentre in any of the three sensory contexts. This was the case for sensor and source space analyses that focused on alpha frequency in occipital cortices. Bayes factors provided mainly moderate evidence for the null hypothesis that pre-stimulus alpha frequency did not influence observers’ flash discrimination performance across the different sensory contexts. Occasionally, we observed significant effects of alpha frequency on sensitivity or bias. However, the most significant effect was opposite to the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis: d’ was greater for low relative to high occipital alpha frequency in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment (Supplementary Figure 2a). However, this effect was not replicated in sensor space or in the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment. The combination of the ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments in the same participants thus enabled us to discard small trends or spurious effects that naturally arise because we performed >150 statistical comparisons in search of within subject alpha frequency effects.

Likewise, observers’ trait alpha peak frequency did not impact observers’ temporal binding window irrespective of whether the binding window was estimated as the threshold from adaptive staircases or psychometric functions in yes-no or 2IFC paradigms. Again, Bayes factors provided strong evidence that alpha trait frequency at sensor and source level did not correlate with temporal binding window length. Importantly, alpha peak frequency and the goodness-of-fit of the psychometric functions were assessed in an objective, experimenter independent fashion to facilitate future replication studies50–52.

How can we reconcile these robust null findings with recent studies showing an effect of alpha frequency on two-flash discrimination performance across trials30 or observers30–32? First, previous studies did not use experimental designs or analyses that enabled the dissociation of temporal resolution and bias. Most notably, when observers are presented with ‘double flash illusion trials’ (1 flash + 2 sounds) throughout the entire experiment31,32, it is likely that differences across observers or time reflect changes mainly in criterion or bias rather than perceptual sensitivity. Consistent with this conjecture, recent research has shown that observers bias their perceptual inference according to task-instructions by modulating their alpha frequency42,43. Alpha frequency may not reflect temporal resolution per se, but rather be related to top-down biases in perception41–43.

Second, alpha frequency effects may be very brittle and prominent only for specific experimental contexts and stimulus parameters. For instance, Samaha and Postle (2015)30 matched the length of one and two flash trials, possibly turning flash discrimination into a gap detection task. Unlike Cecere et al. (2015)32, we presented both one and two flash stimuli in the periphery, because auditory influences on visual cortices are more pronounced in the periphery53,54. This could have affected the occurrence of the sound-induced flash illusion via perceptual or spatial attentional influences. Further, we randomized trials from three sound contexts (0-2 sounds; see 36,55). This provides observers recurrently with true one and two flash experiences, thereby altering their prior expectations and attentional state, which may potentially mask subtle top-down effects. Critically, however, randomizing trials from different sensory contexts mimics everyday multisensory life and enhances the ecological validity of our experiment. Our study also differed from previous studies in terms of its duration (i.e. 4-9 days), which may have increased habituation and learning effects. Further, not to exclude a large percentage of participants as in previous studies, our study may be associated with a greater inter-subject variability with some participants experiencing the double flash illusion very often or very rarely. Nevertheless, our study was able to ensure reliable parameter estimates, because each participant had at least 34 illusion and 47 non-illusion trials in the yes-no threshold experiment.

Third, the persuasiveness of the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis has been waxing and waning since its very inception in the past century15,18. Initial promising results were followed by negative findings and unsuccessful replications already in the early days (for alpha phase)17,56, but also more recently57. In the light of our null-findings we have carefully scrutinized recent studies that are often cited in support of the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis. A study similar to Samaha and Postle (2015) reported a significant association between fusion threshold and individual alpha frequency only when the flash was presented alone (at p < 0.05), but not for the remaining three conditions, when it was preceded by a constant annulus or annuli that changed periodically in luminance58. Further, correlations between alpha frequency and flicker-fusion threshold are often cited in support of the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis. Yet, these have been observed in patients with hepatic encephalopathy or pooled over those patients and controls59,60, making their interpretation tentative in the light of the widespread impact of hepatic encephalopathy on neural and cognitive functions61.

Likewise, recent audiovisual entrainment studies provided a complex picture. Contrary to the alpha temporal resolution hypothesis, a marginally significant decrease in observers’ “two flash” reports was observed after audiovisual entrainment with higher relative to lower alpha frequency62. In a subsequent study, higher relative to lower alpha entrainment increased observers’ accuracy on temporal segregation tasks and decreased their accuracy on temporal integration tasks for the first 100 ms after entrainment. Yet, surprisingly, 100 ms later the opposite cross-over interaction was significant showing better integration and worse segregation for higher alpha entrainment43.

Further, a recent audiovisual double flash illusion study observed no significant correlation between observers’ illusion rates and their trait alpha frequency when estimated from either pre-stimulus or rest periods. After excluding ≈30% participants with very high or low illusion rates, a significant correlation between illusion rate and trait alpha frequency was observed for pre-stimulus alpha, but again not for resting state alpha frequency36. Finally, trait alpha frequency did not correlate with the size of the temporal binding window as estimated from audiovisual temporal order judgments63.

The emergence of a conclusive picture has also been obfuscated by the variability of analysis choices across and even within studies. For instance, alpha frequency was variably defined as 7-12 Hz31, 8-14 Hz32 or 5-20 Hz36 and assessed as a dynamic neural state (inter-trial)30,41,42 or individual trait (inter-subject)30–32,36,41,42 index based on pre-stimulus30,36,41, peri-stimulus31,32 or resting state30,36,43 MEG/EEG data. Some studies also discarded a substantial percentage of participants putting the generality of the findings into question32,36. Furthermore, the number of unpublished null-results – coined the file drawer effect - is unknown and should not be underestimated18.

In the light of this brief review and our consistent null-results the influence of alpha frequency on binding inputs within and across the senses remains inconclusive. One possibility is that subtle effects can arise variably from attentional mechanisms that modulate the temporal precision and binding of sensory inputs at alpha frequency.

In conclusion, the current study provides robust evidence that alpha frequency does not substantially influence the temporal parsing of visual signals into discrete perceptual events in visual or audiovisual perception. Combining EEG with psychophysics and signal detection theory we show that neither dynamic pre-stimulus alpha frequency nor trait alpha frequency impact the temporal resolution or binding of signals within or across the senses. To firmly establish a fundamental role of alpha frequency in temporal parsing future research is needed that defines alpha frequency and perceptual thresholds with consistent and experimenter-independent methods replicated in a large number of participants and across multiple laboratories.

Methods

Participants

After giving informed consent 20 right-handed healthy adults (11 female, mean age: 22.4; age range: 19 - 30) completed the study. Six additional participants were excluded after the first testing session, because the eye-tracker could not be reliably calibrated (three participants) or because participants responded too slowly, multiple times or not at all on > 10% of trials in the first two-interval forced-choice run (1152 trials; Supplementary Figure 1). All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision and reported normal hearing. Participation was compensated with £7.50 per hour. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Birmingham Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Ethics Committee (approval number ERN_11-0429AP22).

Stimuli

The visual stimulus was a light-grey blob formed by a Gaussian with a standard deviation of 1.34° (maximum luminance 12.91 cd/m2) and truncated to a diameter of 4°. It was presented on a dark-grey background (0.71 cd/m2) for approximately 2 ms.

The auditory stimulus was a 2 ms pure tone (3500 Hz) with a 0.5 ms on/off linear ramp (maximum amplitude at the left earpiece was measured at 80 dB SPL). Visual and auditory stimuli were presented at -15° visual angle from a central light-grey fixation cross (12.91 cd/m2). Stimuli were created in Matlab 2014a (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) and presented with Psychtoolbox 3 (http://psychtoolbox.org).

Study design and procedure

The study included three experiments (i. two-interval forced-choice, ii. yes-no with variable SOAs, iii. yes-no at perceptual threshold), each presenting one or two flashes in three sensory contexts (i.e. with i. no sound, ii. one sound, iii. two sounds; Figure 1a). Each participant took part in those experiments in a (typically) five-day testing schedule (see Supplementary Figure 1 for details). On each day participants completed 48 practice trials before the beginning of each main experiment. EEG was recorded during the ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments. In addition, 2 minutes of awake eyes-closed EEG activity were recorded before and after each ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘yes-no threshold ‘ recording day. In the following, we describe the three experiments. We write ‘x sound’ to indicate that each task was presented with none, one or two sounds.

Yes-no variable SOA experiment (concurrent psychophysics and EEG)

In the ‘yes-no SOA’ task, observers were presented on each trial with either one or two flashes, together with none, one or two sounds (‘2 flash + x sound’ or ‘1 flash + x sound’; Figure 1a). On each trial they reported their perceived number of flashes (i.e. one or two flashes). In an 8 x 3 factorial design, we manipulated i. the onset asynchronies of the two potential stimulus onset times within a trial (25, 42, 50, 58, 75, 108, 158, 225 ms) and ii. the number of sounds (zero, one, two).

Prior to the stimulus a blank interval with fixation cross was presented for a variable duration uniformly sampled from an interval between 1200-1700 ms. This interval was 200 ms longer than in the ‘2IFC’ task (see below), because we were interested in pre-stimulus EEG activity that is unrelated to response evoked activity from the previous trial. After stimulus presentation, observers were given a 1500 ms response window. Observers indicated their perceived number of flashes with a two-choice key press using left and right index fingers on the ‘F’ and ‘J’ keys on a standard computer keyboard. An equal number of trials were acquired for each of the two possible key mappings (F = ‘one flash’, J = ‘two flashes’; or F= ‘two flashes’, J = one flash‘), which were counterbalanced across experimental runs (1152 trials) and participants. Participants were instructed to correct mistakes if they noticed them. Participants were given at least 48 practice trials to get accustomed to a change in key mapping.

An experimental run consisted of 12 blocks of 2 (repetitions per block) x 2 (number of flashes: one vs. two) x 8 (SOAs) x 3 (number of sounds) + 1 catch trial per block = 97 fully randomized trials in each block (catch trials did not contain any stimulation and were not used in this report). Four ‘yes-no SOA’ runs were acquired per participant. In total, for each participant, we collected 4608 trials, i.e. 96 trials x 8 (SOAs) x 2 (number of flashes) x 3 (number of sounds).

To ensure comparable cognitive states (e.g. alertness, fatigue etc.) and increase ecological validity, we randomized trials from different SOAs and sensory contexts. In the single interval paradigm this design choice makes the additional assumption that the decision criterion is constant across the entire recording session and does not depend on SOA or sensory context.

Trials were excluded from all analyses when multiple responses occurred on the current or previous trial, no response was registered, or response times were faster than 100 ms after onset of the last stimulus. In some cases, additional data were acquired to compensate for noisy recording periods in the EEG. As a result, the number of trials included in the analysis was on average M = 4410.6 (range: 3860, 4756).

Yes-no threshold task (SOA at perceptual threshold, concurrent psychophysics and EEG)

In the ‘yes-no threshold’ task, observers were presented on each trial with one or two flashes, together with none, one or two sounds (‘2 flash + x sound’ or ‘1 flash + x sound’; Figure 1a). On each trial they reported their perceived number of flashes (i.e. one or two flashes?). To obtain approximately equal probability of “one flash” and “two flash” responses to identical stimuli we adjusted the asynchrony between the two flashes and/or sounds within a trial separately for the ‘2 flash + 0 sound’, ‘2 flash + 1 sound’ and ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ conditions in adaptive staircases and individually for each participant. For each flash-sound pairing we performed two interleaved staircases that started at the inflection points obtained from the psychometric functions of the ‘yes-no SOA’ task (run 1 & 2 vs 3 & 4, see Supplementary Figure 1) and adapted according to one up/one down (i.e. screen refresh rate) scheme depending on observers’ response accuracy. SOAs were not allowed to exceed 5 refresh intervals (~42 ms) above or below the starting value. Staircases were terminated after 10 reversals or a maximum of 24 trials. The average across the final 5 reversals of both staircases was used as the perceptual threshold for the ‘yes-no threshold’ EEG experiment. For observers whose proportion correct did not increase in a monotonic fashion with SOA for the ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ condition in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment, we selected the SOA that was closest to a proportion correct score of 0.5. The ‘2 flash + 2 sound’ SOA was set equal to the ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ SOA. In some participants who showed markedly unbalanced “one flash” versus “two flash” response counts for any of the ‘2 flash + 0 sound’, ‘2 flash + 1 sound’ or ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ conditions during the EEG experiment, we re-started the EEG experiment after adjusting the asynchrony by 1 screen refresh interval of 8.33 ms.

Before the presentation of the first stimulus a blank screen with fixation cross was presented for a variable duration uniformly sampled from the interval between 1200-1700 ms. After stimulus presentation, observers were given a 2500 ms response window. Observers reported their perceived number of flashes and confidence with a two-choice key press using left- and right-hand fingers on the ‘A’, ‘S’, ‘D’, ‘F’ and ‘J’, ‘K’, ‘L’, ‘;’ keys on a standard (United Kingdom) computer keyboard. The responding hand coded the perceptual response, and the responding finger coded perceptual confidence with pinkie (‘A’, ‘;’) = low confidence and index finger (‘F’, ‘J’) = high confidence. An equal number of trials were acquired for each of the two possible hand-key mappings (‘A’, ‘S’, ‘D’, ‘F’ = ‘one flash’, ‘J’, ‘K’, ‘L’, ‘;’ = ‘two flashes’; or ‘J’, ‘K’, ‘L’, ‘;’ = ‘one flash’, ‘A’, ‘S’, ‘D’, ‘F’ = ‘two flash‘), which were counterbalanced between experimental runs (1152 trials) and participants. Participants were instructed to correct mistakes if they noticed them. Participants were given at least 48 practice trials to get accustomed to a change in key mapping.

An experimental run included 12 blocks x 12 (repetitions per block) x 2 (number of flashes) x 3 (number of sounds) + 1 catch trial per block = 73 pseudo-randomized trials (allowing the same flash-sound combination to occur a maximum of four times in a row). Four ‘yes-no threshold’ runs were acquired per participant. In total, for each participant we collected 3456 trials, i.e. 576 trials per condition x 2 (number of flashes) x 3 (number of sounds). In some participants, additional data were acquired to compensate for noisy recording periods in the EEG.

Trials were excluded from all analyses when multiple responses occurred on the current or previous trial, no response was registered, or response times were faster than 100 ms after last stimulus onset. As a result, the number of trials included in the analysis was on average M = 3294 (range: 3068, 3805).

Two-interval forced-choice task (only psychophysics)

In the two-interval forced-choice (2IFC) task observers were presented on each trial in one interval with a probe (‘2 flash + x sound’) and in the other interval with a standard (‘1 flash + x sound’; Figure 1a). On each trial observers reported which of the two intervals included two flashes. The delay between the first and the second interval was 800 ms. The order of the probe and the standard (i.e. interval order) was randomized across trials with an equal number of probe and standard first trials in each sound condition.

In an 8 x 3 factorial design, we manipulated i. the onset asynchronies of the two stimuli within an interval (SOAs: 25, 42, 50, 58, 75, 108, 158, 225 ms for 19 participants and 25, 42, 50, 58, 75, 108, 225 ms for 1 participant) and ii. the number of sounds (none, one, two). Critically, probe and standard within a trial always presented the same number of sounds, so that the number of sounds was uninformative about which interval included the two flashes.

Before the presentation of the first stimulus a blank interval with fixation cross was presented for a variable duration uniformly sampled from between 1000-1500 ms. After the second stimulus interval (standard or probe), observers were given a 1500 ms response window. Observers indicated the interval that presented two flashes with a two-choice key press using left and right index fingers on the ‘F’ and ‘J’ keys on a standard computer keyboard. An equal number of trials were acquired for each of the two possible key mappings (‘F = first interval’, ‘J = second interval’; or ‘F = second interval’, ‘J = first interval’), which were counterbalanced across recording days and participants. Participants were instructed to correct mistakes if they noticed them.

Participants were given at least 48 practice trials to get accustomed to a change in key mapping. To help observers distinguish gaps between trials from the delays between the two-intervals within a trial the fixation cross was rotated by 45° at the beginning of each new trial.

An experimental run consisted of 12 blocks of 2 (repetitions per block) x 2 (interval order: two flashes first vs. second) x 8 (SOAs) x 3 (number of sounds: zero, one or two) = 96 trials. To ensure comparable cognitive states (e.g. alertness, fatigue etc.) between sensory contexts we randomized trials from different SOAs and sensory contexts. As these factors are matched between the first and second interval on a given trial, in the ‘2IFC’ experiment this design choice does not have any influence on data analysis.

Two ‘2IFC’ runs were acquired per participant. In total, for each participant, we collected 2304 trials, i.e. 96 trials per condition (pooled over interval order) x 8 (SOAs) x 3 (number of sounds). Trials were excluded from all analyses when multiple responses occurred on the current or previous trial, no response was registered, or response times were faster than 100 ms post last stimulus onset. As a result, the number of trials included in the analysis was on average M = 2170.3 (range: 1940, 2278).

The ‘2IFC’ task was a psychophysics study without concurrent EEG recording, because the role of pre-stimulus activity (prior to first and second interval) is more difficult to assess in 2IFC paradigms.

Experimental setup

Testing took place in a darkened room with additional light-shielding around the stimulus computer and participant. Stimuli were presented using Psychtoolbox version 3.0.1164 (http://psychtoolbox.org/) in Matlab R2011a (MathWorks Inc.) on a MacBook Pro running Snow Leopard 10.6. Visual stimuli were presented with a 19” cathode ray tube (CRT) display with a refresh rate of 120 Hz and a resolution of 1024 x 768 pixels. Auditory stimuli were presented via EARtone 3A Insert Earphones (Aearo Company Auditory Systems, 1997). A chin-rest ensured a stable head position during task performance.

EEG and eye movement data acquisition

Continuous EEG signals were recorded from 64 channels using Ag/AgCl active electrodes arranged in an extended international 10-20 layout (ActiCap, Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany) at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz, referenced at FCz with a high-pass filter of 0.1 Hz.

Participants’ gaze position was tracked with an EyeLink 1000 Plus desktop mount (SR Research, sampling rate: 2000 Hz). The eye-tracker was recalibrated after a break (73 – 97 trials) if fixation was not focused on the centre of the screen (± 1° visual angle tolerance). After each block in which saccades toward the stimulus (> 5° from central fixation) were detected online by the EyeLink software participants were given feedback at the end of a block to encourage central fixation.

EEG pre-processing

EEG preprocessing was performed with the FieldTrip toolbox (http://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org/)65 and custom written Matlab code. Preprocessing was performed separately for each recording (approximately 70 minutes of task time; for a testing schedule exemplar see Supplementary Figure 1).

Data were low-pass (99 Hz) and notch filtered (48-52 Hz) with zero-phase shift. Noisy channels and time samples were identified via visual inspection of the EEG channel signals and horizontal eye-gaze coordinates from the concurrent eye movement recording (to identify lateral saccades toward the stimulus). Independent component (IC) analysis was applied to the cleaned EEG data and ICs unrelated to brain activity (e.g. blinks, heart beat) were rejected before back-transforming to channel space (on average 1.4 ICs were rejected per recording, range: [1, 5]). Previously identified noisy channels were interpolated via spherical spline interpolation. On average 2.1 channels were interpolated per recording (range: 0, 10). Trial epochs were extracted from -1200 ms to 700 ms relative to first stimulus onset, and down-sampled to 256 Hz. For source space analyses we downsampled to 64 Hz after applying a low-pass filter of 28 Hz. Clean trial epochs were kept for further analysis, linearly detrended and re-referenced to average.

Overview of behavioural and EEG analysis

We investigated the influence of alpha frequency on observers’ temporal perception using two approaches: i. In within-subject analyses we assessed the impact of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on observers’ perceptual sensitivity and bias based on intertrial variability. ii. In between-subjects analyses we assessed the influence of individuals’ trait alpha frequencies on the size of their temporal binding windows as estimated from psychometric functions or adaptive staircases. We computed alpha frequency from EEG signals in sensor and source space from pre-stimulus baseline and eyes-closed resting state. In the main manuscript we focus on the analysis in sensor space; for details about the analysis in source space see Supplementary Methods 1. To control for confounds by alpha power we also report an analysis of pre-stimulus alpha power in the supplementary material.

Within subject analysis

At the within subject level, we binned trials for each subject into terciles based on instantaneous alpha frequency at each pre-stimulus time point and then compared observers’ perceptual sensitivity or bias computed from the first and third tercile. We performed the within-subject analysis in sensor space on the EEG signals averaged over three channels from the right occipital cortex (O2, PO4, PO8) that measure neural activity relevant for processing visual stimuli in the left (i.e. contralateral) hemifield.

Extracting instantaneous alpha frequency across pre-stimulus time

Instantaneous alpha frequency was extracted as described by Cohen66: We filtered the EEG signals from -1200 ms to 0 ms (with additional zero-padding from 0 ms to 600 ms) in the pre-stimulus period with a 6-14 Hz plateau shaped window (15% transition zones, based on66), extracted the instantaneous phase for EEG signals from -600 ms to -100 ms using the Hilbert transform and computed the instantaneous frequency as the temporal derivative of the instantaneous phase as follows:

| (1) |

where H{s(t)} is the Hilbert transformed EEG signal s(t) filtered in the alpha band and arg{H{s(t)}} is the unwrapped instantaneous phase angle time series. We minimized the influence of transient jumps in the instantaneous frequency due to noise by applying ten median filters (linearly spaced between 10-400 ms) followed by a second median filter.

To account for slow non-specific temporal variations in alpha frequency across the multi-day experiment, we performed a regression analysis where we predicted the across pre-stimulus time mean (averaged from -600 ms to -100 ms pre-stimulus) of frequency as the dependent variable by participant (categorical), day (categorical), block number (numerical) and trial number (numerical), as well as their interactions as independent regressors. To account for these non-specific temporal variations, we used the residuals from this regression analysis as the ‘alpha frequency’ variable for all subsequent analyses. Additional within subject analyses without regressing out nuisance variables did not provide any significant alpha effects on sensitivity or bias in the predicted direction.

Extracting alpha power across pre-stimulus time

Because frequency and power can be interactively related67, we also analysed the impact of pre-stimulus alpha power on perceptual sensitivity and bias. Alpha power estimates were obtained by applying the discrete Fourier transform on 400 ms Hanning tapered sliding time windows shifted in 40 ms steps over the -600 ms to -100 ms pre-stimulus time window (with data padding from -1100 ms to -600 ms and -100 ms to 0 ms and zero-padding from 0 ms to 500 ms). Each 400 ms sliding window was zero-padded to 8 s leading to a frequency resolution of 0.125 Hz. From a set of possible frequency values [6, 6.375, 6.75, 7.25, 7.625, 8, 8.375, 8.75, 9.25, 9.625, 10, 10.375, 10.75, 11.25, 11.625, 12, 12.375, 13.25, 13.625, 14] Hz power estimates were computed at the alpha frequency value that was closest to the individual trait alpha peak frequency in the pre-stimulus baseline periods (see Extraction of trait alpha peak frequency and power estimation).

Influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency and power on perceptual sensitivity and bias

We sorted and binned trials independently for each pre-stimulus time point (i.e., every 40 ms from -600 ms to -100 ms) according to their i. instantaneous frequency, or ii. power of alpha oscillations into three terciles separately for each condition in our 8 (SOA) x 3 (number of sounds) design for the ‘yes-no SOA’ task or 1 (SOA) x 3 (number of sounds) design for the ‘yes-no threshold’ task.

In an additional analysis, we collapsed over time, that is we sorted and binned trials into terciles according to the instantaneous frequency or power that was averaged across pre-stimulus time from -600 to -100 ms.

For the first and the third tercile, we computed sensitivity d’ (i.e. temporal resolution) and Biascentre separately for each condition based on a two-equal variance Gaussian signal detection model44 that treats ‘1 flash + x sound’ trials as noise and ‘2 flash + x sound’ trials as signal:

| (2) |

| (3) |

with hit rate (HR) = proportion of “two flash” responses for ‘2 flash + x sound’ trials; false alarm rate (FAR) = proportion of “two flash” responses for ‘1 flash + x sound’ trials. Biascentre > 0 indicates that observers are more likely to report “one flash”. Biascentre < 0 indicates that observers are more likely to report “two flash”.

A small constant of 0.1 was added to hits, false alarms, misses and correct rejections consistently across all conditions to ensure real values for d’ and Biascentre. In the ‘yes-no SOA’ task d’ and Biascentre were further averaged over intermediate SOAs (50, 58, 75, 108 ms), as extreme SOAs often showed floor or ceiling performances. Per participant this analysis included approximately 600 trials for one-event conditions and 300 trials for two-event conditions in the ‘yes-no SOA’ task and 465 trials for each flash-sound combination in the ‘yes-no threshold’ task (for further details see Supplementary Table 1).

To allow for generalization to the population level, we entered d’ and Biascentre computed from data of the first and third terciles (of each participant) across pre-stimulus time into non-parametric cluster-based randomization tests (5000 randomizations) at the random effects level using the summed t-values of two-sided paired t-tests over adjacent time points (exceeding an auxiliary uncorrected alpha threshold of 0.05) as the test-statistic 68. The Null distribution of the cluster sizes (i.e. summed t-values) was obtained by randomly flipping the assignment (or label) of the data to the first and third tercile and choosing the maximum cluster value per randomization. In the time-collapsed analyses, we entered d’ and Biascentre of the first and third tercile (of each participant) into a paired t-tests at the group level. Unless otherwise stated results are reported at p < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons across time at the random effects group level.

In addition to classical statistics, we used Bayesian t-tests for dependent samples with Jeffreys-Zellner-Siow prior (i.e. Jeffreys prior on variance for Ha and H0, Cauchy prior on effect size for Ha)69 to compare the evidence for the null and alternative hypotheses with Bayes factors. We used s = 0.707 for scaling factor s of the Cauchy prior on effect size for t-tests (corresponding to a ‘medium’ scaling factor in the ttestBF function of the R BayesFactor package).

Assessing within subject consistency of the effects of alpha frequency on d’ and Biascentre estimates

To ensure that we did not miss out on subtle alpha frequency effects on d’ or Biascentre that were consistent across the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments within only few participants, but inconsistent across participants we assessed the correlation between the alpha frequency effects of the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment.

In cases of significant correlations, we assessed whether significant effects of alpha frequency were observed when we accounted for this inter-subject variability. For this we flipped the sign of the alpha frequency effect (i.e. d’ high – low frequency) in e.g. the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment based on the sign of the alpha frequency effect in the e.g. ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment and vice versa. We then assessed whether the alpha frequency effects (after flipping them according to the direction of the alpha frequency effect as estimated in the other experiment) were significant by entering them into a one sample t-test.

Between-subjects analysis

At the between-subjects level, we investigated whether the size of observers’ so-called temporal binding window correlates with their trait alpha peak frequency as measured during pre-stimulus baseline or awake eyes-closed recording sessions. Temporal binding windows were operationally defined based on thresholds obtained from psychometric functions or adaptive staircases. In the ‘2IFC’ and ‘yes-no SOA’ experiments we fitted psychometric functions to observers’ proportion correct as a function of stimulus onset asynchrony. In the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment thresholds were defined based on separate staircase procedures for each sensory context (none, one or two sounds).

In sensor space trait alpha frequency estimates were obtained over all posterior EEG channels (O1, O2, Oz, PO9, PO7, PO3, POz, PO4, PO8, PO10, P7, P5, P3, P1, Pz, P2, P4, P6, P8); further, in a control analysis we estimated alpha frequency selectively from channels over the right hemisphere (see supplementary methods for details). In source space, we estimated trait alpha frequency separately based on seven virtual channels within a right hemispheric visual region of interest (see Supplementary Methods 1 for details).

Estimating temporal binding windows based on psychometric functions in the ‘2IFC’ and ‘yes-no SOA’ tasks

For each observer, we computed the proportion correct for each of the 8 (or 7 for one observer) stimulus onset asynchronies separately for the no sound, one sound and two sound contexts for the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘2IFC’ experiments. For each SOA level, proportion correct was computed pooled over one flash and two flash trials. In the no and one sound conditions, the contribution of the one flash trials to proportion correct was therefore constant across SOAs. For the ‘2 sound’ condition, the contribution of the one flash trials to proportion correct varied across SOAs because of changes in the SOA for the two sounds (i.e. ‘double flash illusion’ trials).

Observers’ proportion correct as a function of SOA can be described by a psychometric function with four parameters:

| (4) |

where x is SOA, Fw is the Weibull function, α the threshold (inflection-point), β the slope, γ the guess-rate and λ the lapse-rate (i.e. the probability of an incorrect response independent of probe location). A Weibull function was used because it can incorporate an asymmetric shape of the psychometric function which arises from the fact that SOAs in our study cannot be negative. Critically, this standard psychometric model makes the unrealistic assumption that participants maintain attention constantly across the entire duration of the experiment or days. To account for the non-stationarity in observers’ behaviour and the associated overdispersion, we have used the beta-binomial model70,71. The beta-binomial model assumes that the response probability and hence proportion correct at a particular SOA level is not fixed throughout the entire experiment but a beta-distributed random variable. The variance of fraction correct is determined by the scaling factor η (between 0 and 1) and becomes: , where N is the number of trials at SOA x. The psychometric function is ‘fit’ to observers’ proportion correct jointly across all conditions using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) and Nelder-Mead simplex search72. We estimated separate α threshold (inflection-point), β slope, γ guess-rate parameters for the zero, one and two sound conditions. λ lapse rate and η scale parameter were constrained to be the same for the zero, one and two sound conditions leading in total to 11 parameters. The guess-rate was not fixed to 0.5, because two flash events presented at small SOA may induce an increase in perceived luminance (and hence “two flash” responses for small SOA)73 resulting in guess rates above 0.5.

To ensure that the data can be accurately described by the psychometric function we performed an objective goodness-of-fit test that compared i. the likelihood of participants’ responses given the model that is constrained by the Weibull function to ii. the likelihood given a so-called ‘saturated’ model that models observers’ responses with one parameter for each SOA in each condition50. The likelihood ratio (of i relative to ii) for the original data set was then compared with a null-distribution of likelihood ratios that was generated by parametrically bootstrapping data (1000x) from the model constrained by the Weibull function. If fewer than 5% of the parametrically bootstrapped likelihood ratios were smaller than the likelihood ratio for the original data set (i.e. p < 0.05), then insufficient goodness-of-fit was inferred and psychometric functions were estimated separately for different sound conditions. If goodness-of-fit was again insufficient, the data for this particular participant-condition pairing was discarded from further analyses.

The threshold parameter α refers to the SOA level that is associated with approximately 80% correct in the absence of any guesses or lapses. Thresholds obtained from psychometric functions have previously been used as an index to quantify observers’ temporal binding window30–32. Critically, the interpretation of the threshold from a psychometric function depends on whether it is estimated in a ‘yes-no SOA’ or a ‘2IFC’ experiment. In a ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment the threshold depends on both sensory reliability and criterion. As a consequence, the ‘yes-no’ experiments that were previously used in the literature30–32,41 do not allow us to interpret the temporal binding window as a pure measure for temporal precision and resolution. By contrast, in the ‘2IFC’ experiment the threshold can be used as a measure for perceptual sensitivity (or temporal precision). The temporal binding window obtained from a 2IFC experiment therefore allows us to assess observers’ temporal resolution (in the absence of interval bias74).

Extraction of trait alpha peak frequency estimation

Observers’ trait alpha peak frequency was extracted from i. eyes-closed and ii. task-related pre-stimulus EEG data based on Corcoran and colleagues51 using default parameters (unless otherwise stated) and all posterior EEG channels (O1, O2, Oz, PO9, PO7, PO3, POz, PO4, PO8, PO10, P7, P5, P3, P1, Pz, P2, P4, P6, P8). In addition, control analyses were performed using only medial channels and channels contralateral to the stimulus (O2, Oz, POz, PO4, PO8, PO10, Pz, P2, P4, P6, P8, see supplementary material).

Eyes-closed data were segmented into 2 s epochs with 1 s overlap, Hanning tapered, Fourier transformed to obtain power spectral density (PSD) estimates75 and averaged across epochs. Task related PSDs were estimated for -700 ms to 0 ms pre-stimulus EEG signals. In both cases data were zero-padded to 8 s resulting in a frequency resolution of 0.125 Hz. Spectral peaks were identified in the 6-14 Hz frequency range. Details of the peak-fitting routine are described in Corcoran and colleagues51. In brief, a Savitzky-Golay filter is used to smooth the periodogram and obtain the first and second derivatives. A channel’s alpha peak frequency is located at the zero-crossing of the first PSD derivative and its flanks are located at the adjacent zero-crossings of the second PSD derivative. Peak-power is defined as the PSD integral between peak flanks. Alpha frequency estimates on a given recording day were computed by averaging over all channels (weighted by peak power). Finally, individual trait alpha peak frequency estimates were obtained by averaging over days weighted by the number of successful channel peak estimates per day.

Relating trait alpha frequency to perceptual window length

To assess whether participants’ trait alpha frequency estimates are correlated with their temporal windows of perception, we computed Pearson’s correlation coefficients with threshold parameters α separately for the three sound conditions (no sound, one sound, two sounds) x two experiments (‘2IFC’ vs ‘yes-no SOA’). Bayes factors for Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed using a Jeffreys-Zellner-Siow prior with the implementation provided by Wetzels and Wagenmakers, putting a standard Cauchy prior (s = 1) on effect size76.

Assumptions of parametric statistics were assessed via visual inspection of the residuals (quantile-quantile-plots and residual plots). Normality of residuals was further assessed with Shapiro-Wilk tests. As these tests suggested that the residuals were not always normal for Pearson’s correlation coefficient, we also computed Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. In line with the parametric analyses, there were no significant Spearman rank correlations assessing the relationship of trait alpha frequency and threshold. Therefore, we only report the Pearson correlation in the manuscript.

Assessing within subject consistency of the perceptual threshold estimates across experiments

We obtained perceptual estimates for each participant from each of the three experiments via: i. psychometric functions for ‘yes-no SOA’, ii. adaptive staircases for ‘yes-no threshold’, iii. psychometric functions for ‘2IFC’. Only the threshold of the ‘2IFC’ task can be interpreted as temporal precision or resolution. By contrast, the threshold estimates from the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments can be affected by temporal precision of the sensory inputs and shifts in criterion due to biases which may differ across experimental contexts. We would therefore expect that the thresholds may be correlated between the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments. To assess the extent to which the three experiments measure common or different perceptual thresholds, we entered participants’ threshold estimates into pairwise (e.g. ‘yes-no SOA’ and ‘2IFC’) Pearson correlations.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Typical study schedule.

The standard testing schedule lasted 5 consecutive days. Each day included two experimental runs of approximately 70 minutes task performance organized in ~6 min blocks with self-paced breaks in-between blocks. Additionally, 2-3 minutes of awake eyes-closed EEG activity were recorded prior to a day’s EEG recording of task related activity. Note that in the two-interval forced choice (2IFC) experiment no EEG was recorded.

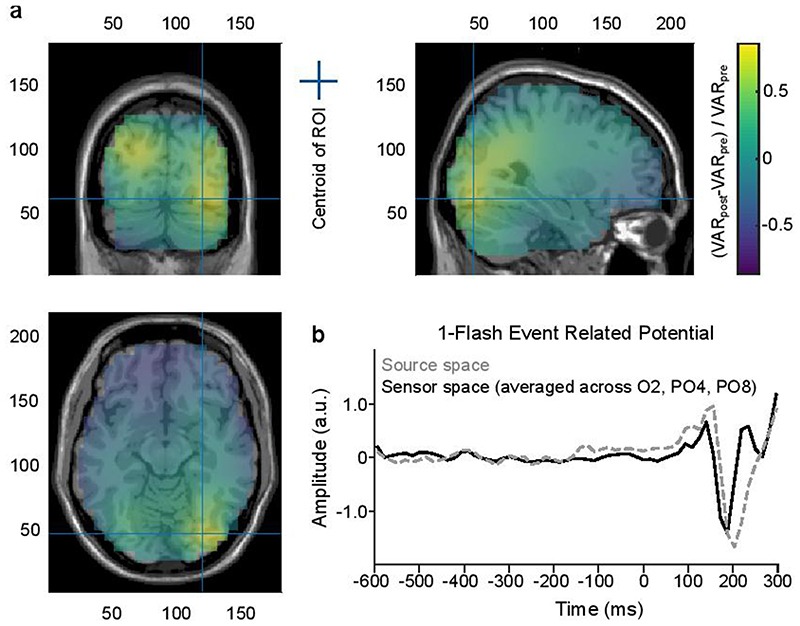

Extended Data Fig. 2. Results from EEG source analysis: Influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on perceptual sensitivity (cf. Supplementary Tables 10, 12).

a, Perceptual sensitivity (across-participants’ mean ± 1 within-subject SEM) is shown for low (1st tercile, dashed) and high (3rd tercile, solid) pre-stimulus alpha frequency in the visual source ROI across pre-stimulus time for experimental design (rows) x sensory context (columns). We observed only two significant effects of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on perceptual sensitivity in the ‘yes-no SOA’ experiment: In the ‘1 sound’ condition for the temporally resolved analysis (column 2: p = 0.015) and in the ‘0 sound’ condition for the time collapsed analysis (column 4: t20 = 3.286, p = 0.004, d = 0.270, 95% CI = [0.092, 0.416]). Neither effect was replicated in the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment. Bayes factors (BF) show the evidence for HA relative to H0 plotted on a log10-scaled ordinate. Purple lines indicate thresholds for moderate evidence favouring H0 (< 1/3) or Ha (> 3)77. b, Within subject consistency of perceptual sensitivity relationship with alpha frequency over tasks. The difference in sensitivity between low and high alpha frequency (Δd’ = d’low – d’high) was not significantly correlated between the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment over participants for any sensory context. SEM, Standard error of the mean. Paired t-test p < 0.01 (**).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Results from EEG source analysis: Influence of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on Biascentre (cf. Supplementary Tables 11, 12).

a, Biascentre (across-participants’ mean ± 1 within-subject SEM) is shown for low (1st tercile, dashed) and high (3rd tercile, dashed) pre-stimulus alpha frequency in the visual source ROI across pre-stimulus time for experimental design (rows) x sensory context (columns). We observed no significant effect of pre-stimulus alpha frequency on bias in any of the experiments (all p > 0.05; columns 1-3, two-sided cluster randomization tests, column 4, paired t-tests). Bayes factors (BF) show the evidence for HA relative to H0 plotted on a log10-scaled ordinate. Purple lines indicate thresholds for moderate evidence favouring H0 (< 1/3) or Ha (> 3)77. b, Within subject consistency of bias relationship with alpha frequency over tasks. The difference in bias between low and high alpha frequency (Δbias = biaslow – biashigh) was significantly correlated between the ‘yes-no SOA’ and the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiments over participants in the 1 sound (see Supplementary Table 12) context. SEM, Standard error of the mean.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Source space trait alpha peak frequency correlations with perceptual threshold (cf. Supplementary Table 15).

Source space pre-stimulus trait alpha peak frequency correlations with temporal binding window estimates obtained from each experiment. In the ‘yes-no threshold’ experiment the binding window size is given as the asynchrony yielding approximately 50% performance accuracy for ‘2 flash + 0 sound’, ‘2 flash + 1 sound’, and ‘1 flash + 2 sound’ trials. The alpha temporal resolution hypothesis, based on previous studies, predicts a negative correlation between alpha frequency and temporal binding window length30–32. Bayes factors (BF) show the evidence for HA relative to H0 plotted on a log10-scaled ordinate. Purple lines indicate thresholds for moderate evidence favouring H0 (< 1/3) or Ha (> 3)77 SEM, Standard error of the mean.

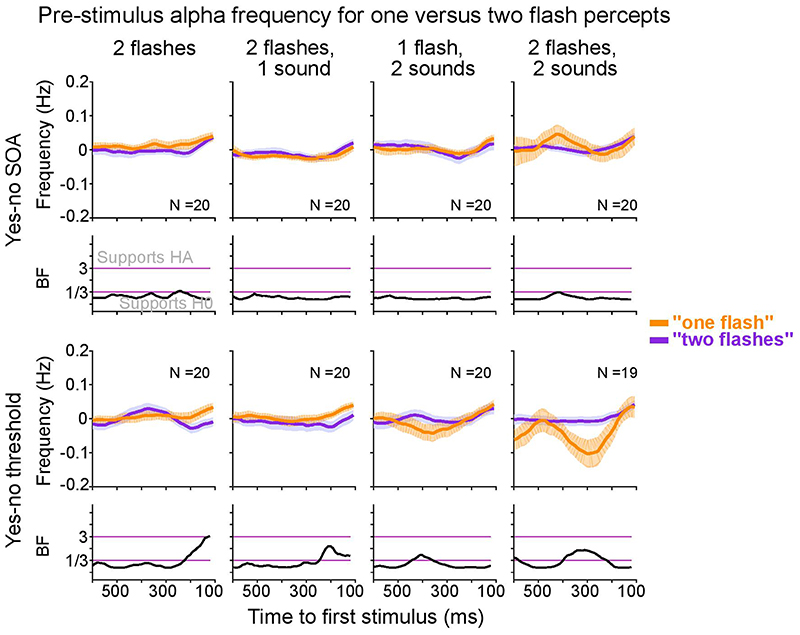

Extended Data Fig. 5. Sensor space within subject analysis: Differences in pre-stimulus alpha frequency for one flash and two flash percepts.

In line with previous research41, we compared pre-stimulus alpha frequency (-0.6 to -0.1 s relative to first stimulus onset) between perceptual outcomes (“see one flash” or “see two flashes” responses) for each ‘2 flash’ condition using cluster-based randomization tests. The alpha band definition was 6-14 Hz, and the electrodes used were O2, PO4 and PO8, as in the signal detection analyses of sensitivity and bias. Please note that this approach cannot distinguish between perceptual sensitivity and bias. We did not observe any significant differences in alpha frequency for “one flash” versus “two flashes” reports.

Error bars denote ± 1 within subject SEM. Bayes factors (BF) show the evidence for HA relative to H0 plotted on a log10-scaled ordinate. Purple lines indicate thresholds for moderate evidence favouring H0 (< 1/3) or Ha (> 3)77. SEM, Standard error of the mean.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Sensor space within subject analysis: The influence of pre-stimulus alpha power on perceptual sensitivity and bias.