Highlights

-

•

Enzymatic modification of mRNA 5′ cap with non-natural moieties to alter mRNA properties.

-

•

Sensitive method for quantification of mRNA cap modifications by LC-MS/MS.

-

•

Detailed workflow from mRNA production and enzymatic modification to LC-MS/MS analysis.

-

•

Comprehensive description of LC-MS/MS techniques for mRNA analyses.

Keywords: 5′ cap, SAM, LC-MS, methyltransferase, chemo-enzymatic

Abstract

Enzymatic modification of the 5′-cap is a versatile approach to modulate the properties of mRNAs. Transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) or functional moieties from non-natural analogs by methyltransferases (MTases) allows for site-specific modifications at the cap. These modifications have been used to tune translation or control it in a temporal manner and even influence immunogenicity of mRNA. For quantification of the MTase-mediated cap modification, liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides the required sensitivity and accuracy. Here, we describe the complete workflow starting from in vitro transcription to produce mRNAs, via their enzymatic modification at the cap with natural or non-natural moieties to the quantification of these cap-modifications by LC-QqQ-MS.

1. Introduction

1.1. Enzymatic cap modifications for altering mRNA function

The 5′-cap is a hallmark of eukaryotic mRNA. The so-called cap 0 consists of an inverted 7-methylguanosine linked to the 5′-end of RNA via a 5′–5′ triphosphate bridge and is installed in all RNA-polymerase II transcripts. It is crucial for many mRNA processing and quality control steps, including maturation, nuclear export, and decay, while also stabilizing the transcript by protecting it from digestion by exonucleases [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. The 5′-cap plays an important role in translation initiation, with the N7-methyl group of the guanosine being essential for recognition by cap-binding proteins and RNA not being translated in its absence [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Additionally, the 5′-cap is subject to further modifications by methyltransferases (MTases), impacting translation and stability of the transcript. Methylations at the 2′-O-position of the first and/or second transcribed nucleotide in higher eukaryotes are catalyzed by CMTR1/2 and lead to formation of the cap 1 or 2, respectively. If adenosine is the transcription start nucleotide (TSN), its N6-position is often methylated by CAPAM [13], [14], [15], [16]. The identity and methylation status of the first transcribed nucleotide impact translation, stability, and immunogenicity of the transcript [13], [14], [15], [17], [18].

Given their importance, these cap methylation sites are promising targets for functionalizing mRNA and tuning these properties with potential applications in therapeutic modalities. We have recently developed MTase-based strategies for the site-specific, enzymatic modification of the 5′-cap in biologically relevant mRNAs. Introduction of a photocleavable group into the methyltransferase Ecm1 enabled light-controlled terminal N7-guanosine methylation of GpppG-capped RNAs and thus provided a means to trigger translation at the time point of choice (N7-methylation by Ecm1 shown in Scheme 1A) [19]. We also investigated CAPAM’s cosubstrate promiscuity and found that N6-propargylation of 2′-O-methyl adenosine at the TSN (Scheme 1B) altered the immunogenicity of the transcript while translation remained high [20].

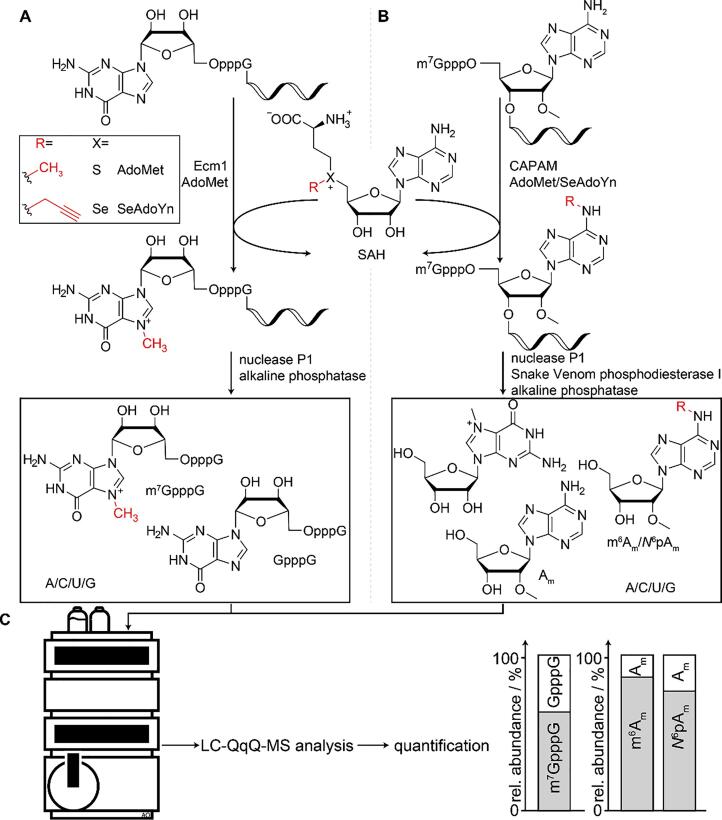

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of enzymatic modification of eukaryotic mRNA, subsequent digestion, and analysis of cap/nucleosides via LC-QqQ-MS. A) Ecm1-catalyzed methylation of the terminal guanosine at its N7 position using AdoMet as cosubstrate. For quantification, RNA is digested to nucleosides while leaving the cap intact, forming either GpppG or m7GpppG. B) CAPAM-catalyzed methylation or propargylation of 2′-O-methyl adenosine (Am) as transcription start nucleotide (TSN) at its N6-position using corresponding cosubstrates (AdoMet or SeAdoYn). For quantification, RNA is completely digested into nucleosides. C) Modifications are quantified by means of LC-QqQ-MS analysis. Nucleosides and/or caps are separated chromatographically and analyzed with a triple quadrupole mass-spectrometer (QqQ-MS) in dMRM mode. External calibration using synthetic standards then allows for quantification of modification yields.

1.2. LC-MS/MS based quantification of cap modifications

Both approaches required quantification of the respective enzymatic modifications, i.e. N7-methylation of guanosine or N6 methylation/propargylation of adenosine versus unmodified transcripts. RP-HPLC-based quantification is robust and proven. However, with limits of quantification in the low pmol range, vast amounts of RNA are required for analysis, while base-line separation of cap-related peaks from intense nucleoside signals is a prerequisite. Alternatively, liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides significantly better sensitivity (typically low fmol range; for selected nucleosides down to low amol range), reducing the amount of RNA sample required for analysis considerably. To illustrate this point, RP-HPLC-based quantification of cap modifications of a typical mRNA (e.g. RLuc-mRNA, ca. 1200 nt; 360,000 g/mol) would require 5–10 µg (ca. 12–25 pmol) of RNA, while for LC-MS/MS-based quantification 10 ng (25 fmol) or 250 ng (700 fmol) of RNA suffice, depending on whether nucleosides or intact caps are to be analyzed. To put these numbers into context: a typical 50 µL in vitro run-off transcription reaction with a cap analog yields 5–30 µg of mRNA after digestion of uncapped transcripts.

Herein, we provide a detailed protocol for the LC-MS/MS-based quantification of enzymatic cap modifications. This protocol comprises production of mRNAs (bearing different cap analogs) coding for different proteins, subsequent enzymatic cap-modifications and their respective quantification via LC-MS/MS using a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (QqQ-MS).

2. Description of the method

In this chapter, we will focus on methodological aspects for quantification of enzymatic cap modifications. This protocol is based on the digestion of RNA to nucleosides, followed by their analysis via LC-MS/MS. The two digestion protocols presented differ in the products produced, i.e. either intact cap or cap degraded to nucleosides. The choice of either protocol depends on the site of the enzymatic modification to be assessed, as explained in the following chapter.

2.1. Preparation of modified RNAs for analysis

The first scenario – i.e. digestion of mRNA into nucleosides while leaving the cap intact – is employed, if the cap-nucleotide modified by the enzymatic reaction also occurs within the RNA itself, i.e. A/G/C/U. In our case, Ecm1 methylates the terminal guanosine, resulting in the formation of N7-methyl guanosine (Scheme 1A). Since unmodified guanosine also occurs within the transcript, quantification via G would lead to inaccurate results. Despite knowledge of the mRNA sequence, the exact ratio of internal G to terminal cap G is unknown, due to untemplated addition of nucleosides during transcription and potential presence of uncapped transcripts despite their digestion [21]. However, if the cap dinucleotide itself remains intact during digestion, the MTase-based conversion can be accurately determined by quantification of GpppG and m7GpppG.

The second scenario – i.e. digestion of the cap into nucleosides – is advantageous, if the enzymatically modified nucleoside in the cap structure is unique, i.e. it does not occur in the mRNA body. In our example, CAPAM-mediated N6-methylation or propargylation of Am results in the formation of N6-methyl- or N6-propargyl-2′-O-methyl adenosine (m6Am/N6pAm; Scheme 1B). RNA from in vitro transcription with m7GpppAm as cap contains Am exclusively in the TSN. CAPAM’s specificity for the 5′-cap precludes internal modifications, allowing for quantification of N6-modified 2′-O-methyl adenosines against Am [14]. This is advantageous if non-natural nucleosides, such as N6pAm, are formed. Here, synthetic standards might not be commercially available. Synthesis of modified nucleosides is more straightforward than synthesizing the respective cap-dinucleotide, which is made by only few specialists [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. Additionally, we observed that in LC-QqQ-MS the detection of nucleosides is more sensitive than of caps.

2.2. Principle of LC-MS/MS quantification

After digestion, nucleosides or caps of interest are quantified via LC-MS/MS using a triple quadrupole mass-spectrometer (QqQ-MS) operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The principle of cap and nucleoside detection via LC-QqQ-MS analysis is central to the method described herein and will be briefly explained here (Scheme 2). The first (Q1) and third quadrupole (Q3) are separated by a quadrupole collision cell (q2) and serve as mass-filters. The first quadrupole is set to permit only selected precursor ions with their specific m/z value into the collision cell. In the quadrupole collision cell, the precursor ions dissociate into characteristic product ions by collision-induced dissociation (CID) with an inert gas (typically argon or nitrogen). The third quadrupole is set to permit only these specific product ions. By using different collision energies (CE), different product ions from the same precursor ion are obtained by CID. The most abundant product ion obtained under a certain CE is used for quantification (termed quantifier) while less abundant product ions (termed qualifier) help to ascertain specificity towards the analyte by its distinct quantifier/qualifier ratio. Analysis in the MRM mode offers multiple advantages. Background is reduced by filtering out unwanted ions in Q1 and Q3, while the combination of precursor ions with multiple specific product ions achieves a high specificity for the analyte. Unlike in scan mode, where a broad mass range is consistently scanned, in MRM mode, only the masses of selected product ions are detected. The resulting high sensitivity allows for analyte detection and quantification in the low fmol range or lower in complex matrices [27]. A prerequisite for MRM analysis is knowledge of the characteristic – and ideally specific – fragmentations of the precursor ion by CID. Additionally, the fragmentor voltage and the collision energy require optimization to maximize the abundance of respective product ions and increase sensitivity.

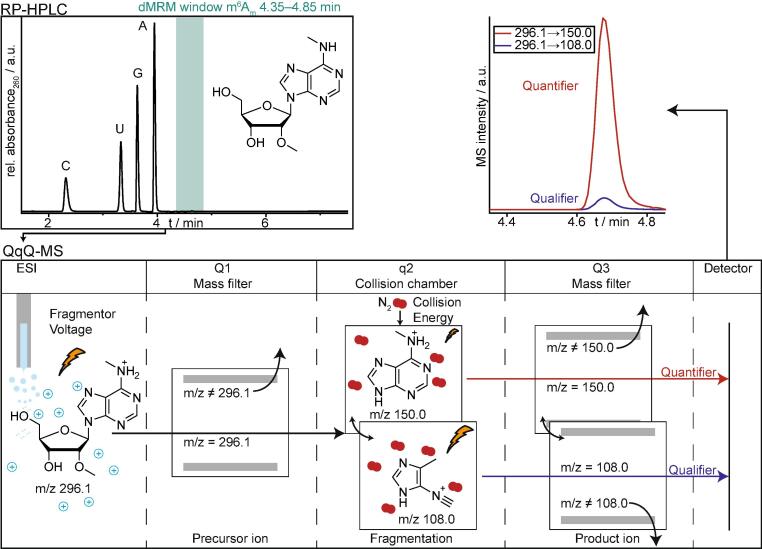

Scheme 2.

Schematic illustration of nucleoside detection via LC-QqQ-MS using m6Am as example. After chromatographic separation via RP-HPLC, nucleosides are ionized via electrospray ionization (ESI) by applying a defined fragmentor voltage in the QqQ-MS. The first quadrupole (Q1) acts as a mass filter and is set to permit only defined precursor ions into the collision chamber (q2). Here, precursor ions are fragmented via collision-induced dissociation (CID) with N2 into specific product ions. Degree of fragmentation depends on the collision energy applied. By cycling between different CEs, two (or more) specific product ions are produced from a single precursor ion. Q3 acts again as mass filter, permitting only defined product ions to the detector. The product ion giving the greatest response is used for quantification (quantifier) while other specific product ions are used as qualifiers. The respective quantifier/qualifier ratio allows for assessment of selectivity towards the analyte.

In dynamic MRM (dMRM) mode, the number of concurrently measured transitions is minimized by measuring each analyte only in a defined time window when it elutes from the column. This in turn minimizes time spent measuring analytes when they do not elute, resulting in more data points measured for each analyte and thus higher quality data. This is of importance for modern LC systems with peak widths in the range of just a few seconds. In our example, respective transitions for m6Am are exclusively measured between 4.35 and 4.85 min (Scheme 2). This requires knowledge of the analytes retention times (RT) and RT reproducibility over multiple runs. Respective RTs are given herein. If performed on a different LC-MS/MS system, RTs are easily determined, since in this method standards of analytes are required for external calibration.

For quantification of cap modifications, comparison to respective synthetic standards of known concentration is required. Calibration using stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) has become the gold standard for highly accurate quantification [28], [29]. It requires isotopologs of respective analytes with a Δm/z of at least 2. However, synthesis of these standards in weighable quantities is often tedious and not straightforward. Especially for quantification of multiple nucleosides, chemical access represents a bottleneck for most laboratories. Alternatively, by growing organisms of interest in isotope labeled media, the complete nucleoside pool is obtained as isotopologs and can be used for quantification [27], [30]. However, isotopologs of non-natural nucleosides cannot be accessed with this technique and still require synthesis. In the method presented herein, analytes are quantified via external calibration, using non-isotope labeled standards. It is more straightforward and has previously been demonstrated for the mRNA cap epitranscriptome [31], [32], [33]. Here, chemical access to non-labeled standards is easier. For quantification of enzymatically installed modifications of in vitro transcribed RNA, purity can be ascertained by precipitation and washing steps, eliminating potential ion suppression by matrix effects.

3. Material and methods

Technical note: All work involving RNA should be performed in a designated, RNase-free area. Decontamination of the workspace and the interior and exterior of pipettes with commercial RNase decontamination solutions or a 10% (v/v) H2O2 solution is recommended. Commercially available RNase inhibitors can be used to prevent RNA degradation in enzymatic reactions. Digestion of RNA into nucleosides must not be performed in this area. Ultrapure, RNase-free water should be used for the preparation of buffers and RNA samples.

3.1. Chemicals

Water used herein was obtained from an ultrapure water system (Veolia PURELAB flex 2 with biofilter) and is referred to as ddH2O in the following. Specifications: Resistivity≡18.2 MΩ × cm at 25 °C; total organic carbon (TOC) < 5 ppb; bacteria < 0.001 CFU/mL; bacterial endotoxin < 0.001 EU/mL; DNase < 5 pg/mL; RNase < 1 pg/mL; chlorine < 0.05 ppm Cl2.

Chemicals were purchased from VWR (ammonium acetate, LC-MS grade), Sigma Aldrich (acetic acid, LC-MS grade), Fisher Scientific (acetonitrile, LC-MS grade).

Nucleosides and cap standards were obtained from NEB (m7GpppG, GpppG), Trilink (m7GpppAmG), Biomol (Am), Carbosynth (m6Am) and Merck (A). N6pAm was synthesized as described previously [20].

3.2. Production and purification of enzymes

The enzymes Ecm1, CAPAM and MTAN were produced and purified as previously described [19], [20], [34].

3.3. Production of mRNA

The mRNAs with a di- or trinucleotide cap were produced by in vitro run-off transcription. Cap analogs used in this study were GpppG (NEB) or m7GpppAmG (CleanCap®, Trilink). Transcripts used in this study were RLuc, FLuc, eGFP, and RBD (receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2) RNAs. DNA templates with appropriate promoter sequences (T7 phi 6.5 for GpppG, T7 phi 6.5 initiating with A instead of G for CleanCap) were produced via PCR from respective pMRNA plasmids [35], [36]. PCR products were purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-Up (Macherey Nagel). In vitro run-off transcription reactions were prepared as described in Tables 1 and 2 in an RNase-free tube, components were pipetted in the order indicated. Homogeneity of the reactions was ensured by mixing before and after addition of the enzymes. Transcription yields for a 25 µL reaction are typically in the range of 2.5–15 µg RNA of capped RNA. Reactions can be scaled up as needed.

Table 1.

In vitro run-off transcription for production of GpppG-capped RNA.

| Compound | Cstock | Volume [µL] | Cfinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| ddH2O | – | ad 25 µL | |

| DNA template | 100–1000 ng/µL | 100 ng | |

| transcription buffer (Thermo Scientific) | 5× | 5 | 1× |

| A/C/UTP mix | 5 mM | 2.5 | 0.5 mM |

| GTP | 1 mM | 6.25 | 0.25 mM |

| GpppG | 10 mM | 2.5 | 1 mM |

| Ribolock RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Scientific) | 40 U/µL | 0.75 | 1.2 U/µL |

| Pyrophosphatase (Thermo Scientific) | 0.1 U/µL | 1 | 0.004 U/µL |

| T7 RNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific) | 20 U/µL | 2.5 | 2 U/µL |

Table 2.

In vitro run-off transcription for production of m7GpppAmG-capped RNA.

| Compound | Cstock | Volume [µL] | Cfinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| ddH2O | – | ad 25 µL | |

| DNA template | 100–1000 ng/µL | 100 ng | |

| transcription buffer (Thermo Scientific) | 5× | 5 | 1× |

| G/A/C/UTP mix | 25 mM | 1.5 | 1.5 mM |

| m7GpppAmG (CleanCap®) | 10 mM | 2.5 | 1 mM |

| Ribolock RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Scientific) | 40 U/µL | 0.75 | 1.2 U/µL |

| Pyrophosphatase (Thermo Scientific) | 0.1 U/µL | 1 | 0.004 U/µL |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | 20 U/µL | 2.5 | 2 U/µL |

Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. For digestion of the DNA template, 2 µL of DNase I (1 U/µL, RNase-free, Thermo Scientific) per 25 µL transcription reaction were added, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C.

RNA was then purified via the RNA Clean & ConcentratorTM-5 Kit (Zymo Research) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was eluted in 30 µL ddH2O, concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm.

Depending on the downstream application of the mRNA, uncapped (i.e. 5′-triphosphorylated) transcripts may have to be removed. Uncapped transcripts can be digested by consecutive action of a 5′-polyphosphatase – releasing pyrophosphate from 5′-ppp-mRNA to produce 5′-p-mRNA – and the exoribonuclease XRN1, for 5′→3′ digestion of 5′-p-mRNA. Digestion reactions were performed in an RNase-free tube and scaled according to the amount of input RNA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Degradation of 5′-ppp-mRNA to 5′-p-mRNA.

| Compound | Cstock | Volume [µL] | Cfinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| ddH2O | ad 20 µL | ||

| 5′-polyphosphatase reaction buffer | 10× | 2 | 1× |

| mRNA | max 5 µg | ||

| 5′-polyphosphatase (Lucigen) | 20 U/µL | 1 | 1 U/µL |

The reaction was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C.

For 5′ → 3′ digestion of 5′-p-mRNA transcripts, 2.5 µL of MgCl2 (50 mM, 5.3 mM final conc.) and 1 µL XRN1 (1 U/µL, 0.04 U/µL final conc.) were added to the reaction mixture and incubated at 37 °C for one additional hour.

RNA was then purified and eluted as described above. RNA integrity was assessed via dPAGE and stored at −20 °C until further use. To confirm success of digestion, uncapped RNA can be used as positive control during enzymatic digestion. Here, in the subsequent dPAGE analysis, no RNA should be visible.

3.4. Enzymatic modification of mRNA at the 5′-cap

Technical note: Sodium ions can interfere with LC-MS analysis, forming [M + Na]+ adducts that escape MRM analysis. To remove sodium ions from solutions, RNA was precipitated using NH4OAc (0.5 M final concentration) instead of NaOAc upon enzymatic modification. Pellets were washed with 70% EtOH. Of note: Buffers from commercial kits potentially contain sodium salts [37].

3.4.1. N7-Methylation of GpppG-FLuc-RNA

For enzymatic terminal N7-methylation of the terminal guanosine in GpppG-RNA, modification reactions were assembled as detailed in Table 4 in ddH2O. Homogeneity of the reaction was ensured by mixing before and after the addition of enzymes.

Table 4.

Terminal N7-methylation of GpppG-RNA.

| Compound | Cstock | Cfinal |

|---|---|---|

| GpppG-RNA | 200 nM | |

| 10 × Ecm1 reaction buffer | 10× | 1× |

| AdoMet | 10 µM | 600 nM |

| MTAN | 1.5 µM | |

| Ecm1 | 200 nM |

The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h.

10 × Ecm1 reaction buffer: 200 mM HEPES, 1500 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.5 at 20 °C

RNA was extracted and precipitated as described in 3.4.2.

3.4.2. N6-Methylation or propargylation of adenosine at the TSN of m7GpppAmG-capped RNAs

For enzymatic N6Am-methylation or propargylation of the TSN in m7GpppAmG-RNA, modification reactions were assembled as detailed in Table 5 in ddH2O. Homogeneity of the reaction was ensured by mixing before and after addition of enzymes.

Table 5.

TSN N6-modification of m7GpppAmG-RNA.

| N6-methylation | N6-propargylation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Cstock | Cfinal | Cfinal |

| m7GpppAmG-RNA | 500 nM | 500 nM | |

| 5 × CAPAM reaction buffer | 5× | 1× | 1× |

| AdoMet | 32 mM | 500 µM | – |

| SeAdoYn [38] | – | 500 µM | |

| MTAN | 750 nM | 750 nM | |

| CAPAM | 1 µM | 1 µM |

The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h.

5 × CAPAM reaction buffer: 500 mM HEPES, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.5 at 20 °C

After enzymatic reaction, RNA was extracted by phenol/chloroform. To this end, samples were adjusted to a final volume of 200 µL with ddH2O, 10% (v/v) NH4OAc, and 1 µL glycogen (RNA grade). Upon addition of 1 vol phenol/chloroform (5:1), samples were vigorously mixed (15 sec) and centrifuged (21,300×g, 3 min, 4 °C). The aqueous phase was removed, RNA was precipitated in 70% EtOH. The resulting pellet was washed with 70% (v/v) EtOH and finally dried in a SpeedVac (10 min, 35 °C, 1 mbar; RNA was found to be stable under these conditions).

RNA was resuspended in ddH2O, concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm. The integrity of the mRNA was subsequently analyzed on a 7.5% dPAGE gel. mRNA was stored at −20 °C until further use.

3.5. Digestion of RNA into nucleosides

For quantification by LC-QqQ-MS, RNA was digested into nucleosides. Depending on the modification to be assessed, the cap is either left intact or digested into nucleosides as outlined in chapter 2. For digestion of the whole transcript – including the cap – into nucleosides, a combination of nuclease P1 and snake venom phosphodiesterase followed by dephosphorylation with alkaline phosphatase was employed as described by Thüring et al. [37]. After dephosphorylation, proteins are precipitated by addition of 1/10th volume HClO4 (1 M), cooling on ice for 1 min and 10 min centrifugation at 21,300 × g. The supernatant is then transferred into suitable LC-MS vials and analyzed.

If the cap is to be left intact during digestion, nuclease P1 is used without the addition of snake venom phosphodiesterase (nuclease P1 is similarly dissolved as described by Thüring et al.) [37]. In this case, up to 4 µg RNA were incubated with 0.4 µL nuclease P1 in 1 × nuclease P1 reaction buffer (10 × reaction buffer: 200 mM NH4OAc, 1 mM ZnCl2, pH 5.3 adjusted with glacial acetic acid) in 30 µL at 50 °C for 1 h. Nucleosides were dephosphorylated by addition of 1/10th volume of 10 × fast alkaline phosphatase (FastAP™) buffer and 1 U FastAP (both Thermo Scientific) followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. Proteins were precipitated by addition of HClO4 as described above.

Typically, for LC-QqQ-MS quantification, 0.14–2 pmol of RNA were digested. The required amount of sample depends on the LC-MS system used and its respective detection limits for caps and nucleosides. Establishing these instrument detection limits (IDL, see 3.10) can help to determine the amount of RNA required for analyses.

3.6. LC-MS buffer

Technical note: All reagents should be LC-MS grade. Use one batch of freshly prepared buffer for all samples in the quantification queue, including standards for external calibration and actual samples. Changing buffers within the analysis can negatively affect the accuracy of quantification.

The column was stored in acetonitrile/water (70:30). Before analysis, the column was first equilibrated to 100% ddH2O and then into 100% buffer A using a dedicated chromatographic method. Before analysis, the column was equilibrated in buffer A by running the respective analysis method twice.

Buffer A: 20 mM NH4OAc, pH 6. For the preparation of buffer A, 1.542 g NH4OAc were dissolved in ddH2O, adjusted to pH 6 with glacial acetic acid, and filled to 1 L with ddH2O.

Buffer B was LC-MS grade acetonitrile as purchased.

3.7. The mass spectrometer

Technical note: Thorough cleaning of the ion source before quantification is recommended to increase sensitivity.

The LC-QqQ-MS system used in this study is an Agilent Ultivo Triple Quadropole mass spectrometer coupled to an Agilent 1260 Infinity II Prime LC-system.

Chromatographic separation was performed on a Poroshell 120EC-C18 3 × 150 mm 2.7 µM column plus complementary guard cartridge (both Agilent Technologies). Different gradients, flow rates and column temperatures were employed for the detection of nucleosides versus caps (Tables 6 and 7). We found that for the detection of caps, a column temperature of 20 °C gave sharper peaks compared to higher temperatures, whereas chromatographic separation of nucleosides was optimal at 40 °C.

Table 6.

Chromatographic parameters.

| Method A: Nucleosides | Method B: Caps | |

|---|---|---|

| Flow rate | 0.8 mL/min | 0.6 mL/min |

| Column temperature | 40 °C | 20 °C |

Table 7.

Elution gradient and chromatographic parameters.

| Method A: Nucleosides |

Method B: Caps |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time [min] | Buffer B [%] | Time [min] | Buffer B [%] |

| 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 |

| 7.0 | 60 | 7.0 | 30 |

| 7.2 | 100 | 7.2 | 100 |

| 8.8 | 100 | 8.8 | 100 |

| 9.0 | 0 | 9.0 | 0 |

| 12.0 | 0 | 12.0 | 0 |

Nitrogen of highest purity was used as nebulizing and collision gas. Electrospray ionization (ESI) in dMRM mode was used for analysis. The mass spectrometer was equipped with an Agilent JetStream ion source, introducing a superheated sheath gas (N2) for improved ionization efficiency (respective ESI settings are listed in Table 8). The fragmentor voltage and collision energies were optimized for each nucleoside or cap. The optimization process is explained in detail in 3.8. Respective MRM settings for each fragment are shown in Table 9. The LC-QqQ-MS system was controlled with the MassHunter Data Acquisition Software (for Ultivo LC/TQ, version C.01.00), for analysis MassHunter Quantitative Analysis Software (for QqQ, version B.09.00) and MassHunter Qualitative Analysis Navigator (version B.08.00) were used. For optimization of MRM settings, MassHunter Optimizer (version C.01.00) was used.

Table 8.

Mass spectrometer settings used for all methods described herein.

| Parameter | Settings |

|---|---|

| Gas temperature | 250 °C |

| Gas flow | 7.0 L/min |

| Nebulizer | 40 psi |

| Sheath gas temperature | 375 °C |

| Sheath gas flow | 12 L/min |

Table 9.

Mass spectrometer settings used for nucleosides and caps analyzed herein (CAV: cell acceleration voltage). Settings for quantifiers (quant.) and qualifiers (qual.) are shown.

| Compound (quantifier/qualifier) | Mode | Precursor ion (m/z) | Product ion (m/z) | Fragmentor voltage(V) | CAV (V) | Collision energy (V) | Retention time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Am (qual.) | pos. | 282.1 | 69.1 | 109 | 9 | 25 | 4.2 |

| Am (quant.) | pos. | 282.1 | 136.1 | 109 | 9 | 9 | 4.2 |

| m6Am (qual.) | pos. | 296.1 | 108.0 | 121 | 9 | 68 | 4.6 |

| m6Am (quant.) | pos. | 296.1 | 150.0 | 121 | 9 | 8 | 4.6 |

| N6pAm (qual.) | pos. | 320.1 | 68.8 | 121 | 9 | 25 | 5.0 |

| N6pAm (quant.) | pos. | 320.1 | 174.0 | 121 | 9 | 9 | 5.0 |

| GpppG (qual.) | pos. | 789.1 | 134.7 | 150 | 9 | 121 | 3.0 |

| GpppG (quant.) | pos. | 789.1 | 151.8 | 150 | 9 | 57 | 3.0 |

| GpppG (qual.) | pos. | 789.1 | 248.4 | 150 | 9 | 21 | 3.0 |

| m7GpppG (qual.) | pos. | 803.1 | 151.7 | 135 | 9 | 61 | 4.3 |

| m7GpppG (qual.) | pos. | 803.1 | 165.7 | 135 | 9 | 53 | 4.3 |

| m7GpppG (quant.) | pos. | 803.1 | 248.1 | 150 | 9 | 21 | 4.3 |

This protocol can also be applied to comparable LC-MS systems, however some of the information given herein might not apply and hardware-dependent parameters must be adapted.

3.8. Establishing MRM parameters for nucleosides and caps

To achieve optimal sensitivity for the analytes, instrument parameters such as fragmentor voltage and collision energy have to be optimized individually for each product ion. The fragmentor voltage has to be sufficiently high to give maximum abundance of the precursor ion, while at the same time not fragmenting it. The collision energies in the q2 are individually optimized to yield maximum abundance of the product ions. In the QqQ-MS system used herein, the cell acceleration voltage (CAV) was fixed to 9 V. In other systems, this parameter might be subject to optimization. Respective parameters determined for analytes used herein are shown in Table 9.

First, to identify the precursor ion, the standard was analyzed using the appropriate chromatographic method (see 3.7) in scan mode with the fragmentor voltage set to 135 V. Ideally, only one distinct peak corresponding to [M + H]+ is found while adducts corresponding to [M + Na]+ or [M + NH4]+ are not observed. Optionally, the abundance of the precursor ion can be increased by adjusting the fragmentor voltage in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode.

Next, suitable product ions formed by CID of the precursor ion were identified, serving as starting points for further optimization of the MRM parameters. The analyte was investigated using the appropriate chromatographic method in product ion scan mode. The product ion scan was set up to measure 4 product ion scans in parallel, measuring at a constant fragmentor voltage and differing collision energies. The fragmentor voltage was either set to 135 V or to the optimized value identified in SIM mode. The first quadrupole was set to permit only the precursor ion into the collision chamber. Here, sequentially varying collision energies ranging from 20 to 120 V (i.e. 20, 60, 100, 120 V) were applied, resulting in the fragmentation of the precursor ion into different product ions. The third quadrupole was operated in scan mode with the scanning range set from 50 Da up to the mass of the precursor ion, allowing for the identification of respective product ions. For nucleosides, typically intense product ion signals corresponding to the ribose loss were identified (see chapter 3.9). At higher collision energies, smaller product ions are formed. The most abundant product ions were identified and used for further optimization. To this end, the MassHunter Optimizer software was used, automatically testing different combinations of fragmentor voltage and collision energy and identifying parameters resulting in the highest abundance of selected product ions. The two or three product ions with the highest abundance were selected as quantifier and qualifier ions, respectively.

These quantifiers and qualifiers were then assembled in a suitable method (Method A for nucleosides, B for caps). In combination with their respective retention times and an appropriate retention time window (typically 1 min), a dynamic MRM (dMRM) method was created. If the retention time of the analyte is known and stable, dMRM methods are preferred over MRM methods, limiting the number of transitions measured in parallel, and consequently further enhancing sensitivity. dMRM methods are based on individual retention time windows for each MRM transition, while classical MRM measures transitions of all analytes during the whole run.

It should be mentioned that recently multiple LC-QqQ-MS based methods for the detection of caps have been published [31], [32], [33]. The MRM parameters reported there can also serve as starting points for optimization on a particular LC-MS system.

3.9. Typical fragmentation patterns

A fragmentation typically observed for nucleosides at low collision energies is the ribose loss [39]. Here, the N-glycosidic bond is cleaved, resulting in the loss of 132 Da for ribose, or 146 Da for 2′-O-methyl ribose (Scheme 3). This ribose loss typically results in the highest response and is often used as the quantifier. Further fragmentations of the cleaved nucleobase occur at higher collision energies and are less trivial to predict. These transitions often result in less abundant product ions than the ribose loss and are therefore used as qualifiers. Here, typical fragmentation patterns for positive and negative modes can be found in literature [40], [41], [42]. Fragmentation patterns for caps are difficult to predict and require individual optimization.

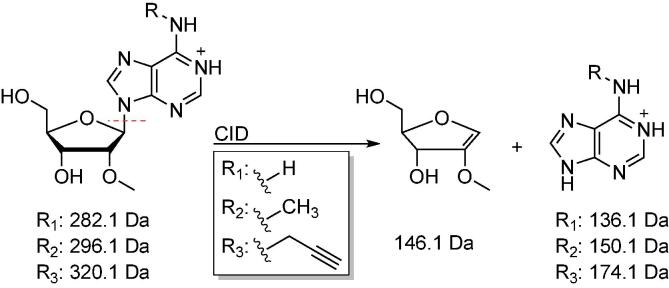

Scheme 3.

Representation of typical fragmentation patterns for nucleosides shown for Am, m6Am, N6pAm. Nucleosides typically fragment at their N-glycosidic bond, resulting in loss of ribose (-132 Da) or 2′-O-methyl ribose (146.1 Da, shown here), depending on the nucleoside analyzed. Increased collision energies typically result in further fragmentation of the nucleobase.

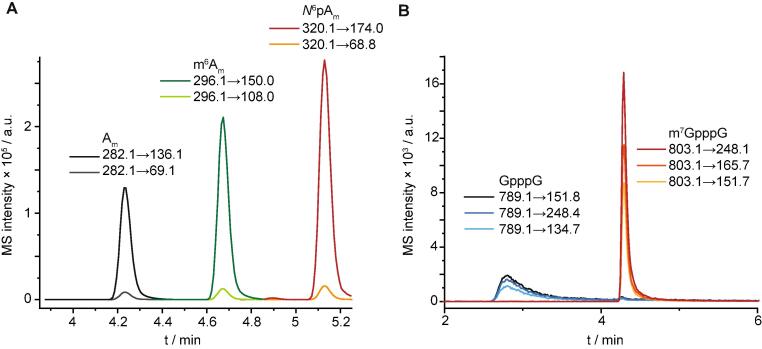

Optimized quantifier and qualifier transitions (MRM mode) for nucleosides and caps investigated herein are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

LC-QqQ analysis of nucleoside standards in dMRM mode. Shown are the MS intensities of Am, m6Am, N6pAm (A) and m7GpppG and GpppG (B). MRM-transitions of the respective quantifier and qualifier are shown.

3.10. Determination of the instrument detection limit

The instrument detection limit (IDL) was calculated as described by Sheehan et al. and technical guidelines from Agilent Technologies on this topic [43], [44], [45]. The IDL is a statistical measure and defined as the minimum amount of analyte required to produce a signal that is statistically distinguishable from the background noise level with 99% confidence and is calculated using Eq. (1). Knowledge of the individual IDLs can help to determine the minimal amount of RNA required for analysis.

| (1) |

With t(n-1,1-α=0.99) = Students’ t value appropriate for a 99% confidence level and n-1 degrees of freedom (number of replicate injections minus 1); RSD = relative standard deviation of the mean peak area from replicate analyses (=SD*100%/mean value).

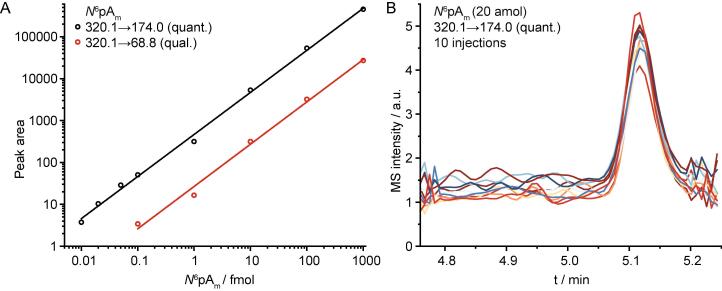

The IDL is determined by replicate injections of analyte near its expected limit of detection. To determine the amount of sample used for replicate injections, different concentrations in the low amol to fmol range were measured. This is exemplified for IDL determination of the of N6pAm quantifier and qualifier transitions (Fig. 2A). A suitable amount of analyte (within 5–10 fold of the noise level) was then chosen for IDL determination. In this example, we chose 20 amol for determination of the quantifier IDL. The average peak area for the 320.1 → 174.0 quantifier transitions of 10 replicate injections had a RSD of 7.56% (Fig. 2B). Here, t(n-1,1-α=0.99) is 2.821 with a 99% confidence level and 9 degrees of freedom (10–1 injections).

Fig. 2.

Exemplary determination of the IDL of the N6pAm quantifier transitions. A) Double-logarithmic plot showing peak areas of the quantifier and qualifier product ions versus amount of N6pAm. Multiple concentrations of N6pAm were measured near its expected detection limit, to assess which amount should be used for IDL determination. B) Example showing 10 separate injections of 20 amol N6pAm. Subsequent calculation using Eq. (1) determined IDL to be 4.3 amol. For further details, see text.

IDL (N6pAm 320.1 → 174.0) = 2.821 × (7.56%/100%) × 20 amol = 4.3 amol

Thus, 4.3 amol can be distinguished from background with 99% certainty, when looking at the 320.1 → 174.0 quantifier transition.

Using the above described methods and parameters we found low IDL for nucleosides in the single digit amol range, while caps had IDL in the low fmol range for respective quantifier transitions (Table 10). Since for quantification the quantifier/qualifier ratio is assessed to ascertain specificity towards the analyte, the IDL of qualifier transitions should be determined too and represents the lower limit of quantification.

Table 10.

Instrument detection limit of selected nucleoside analogs and caps as determined for quantifier transitions.

| Compound | Instrument detection limit (IDL) |

|---|---|

| N6pAm | 4.3 amol |

| m7GpppG | 6.8 fmol |

| GpppG | 34.1 fmol |

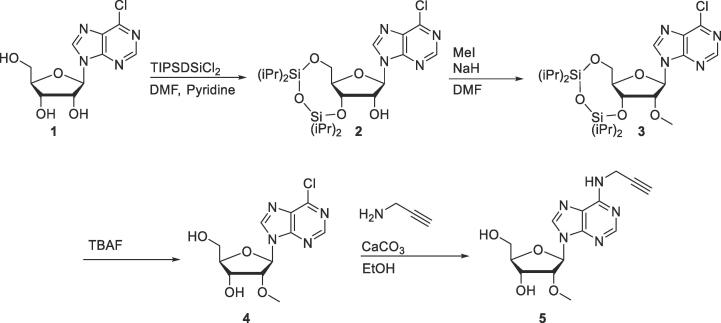

3.11. Synthesis of nucleoside standards

For the quantification of N6-adenosine propargylation by CAPAM, synthesis of the respective N6-propargyl-2′-O-methyl adenosine (N6pAm) standard was required. Since modification takes place at Am in the TSN position and does not occur within the mRNA body itself, the extent of modification can be assessed by quantification of N6pAm versus Am, avoiding laborious synthesis of the respective m7GpppN6pAm cap.

To this end, N6pAm was synthesized in four steps from 6-chloropurine riboside (Scheme 4) as described recently by our group [20]. Briefly, 2′-O-methylation required 3′- and 5′-protection with 1,3-dichloro-1,1,3,3-tetraisopropyldisiloxane (TIPSDSiCl2) followed by methylation with methyl iodide and NaH [46]. Deprotection with tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride (TBAF) released 6-chloropurine-2′-O-methyl-riboside which was reacted with propargylamine, yielding N6-propargyl-2′-O-methyl adenosine (N6pAm, 5) [47]. N6pAm was purified via semi-preparative RP-HPLC on a NUCLEODUR C18 Pyramid column (125 × 10 mm, Macherey Nagel) column. Purity of the standard was confirmed via RP-HPLC and high-resolution MS.

Scheme 4.

Reaction scheme for the synthesis of N6pAm.

3.12. Quantification of cap modification

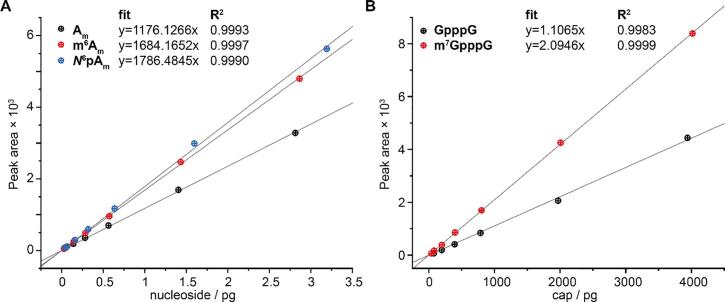

Technical note: Very accurate pipettes are required for the dissolution of standards and generation of premixed standard solutions. Alternatively, accuracy can be ensured by using microbalances as detailed by Traube et al. [28]. Quantification using two different calibration curves should be avoided. Instead, variations of the injection volume and/or dilution of the sample should be considered, so that all modifications can be quantified using a single calibration curve.

Enzymatic mRNA 5′-cap modifications were quantified via external calibration. First, stock solutions of the respective standards in ddH2O were prepared. Small amounts of the nucleoside standards (~10 mg) were weighed on a microbalance into separately tared 2 mL tubes. Then, ddH2O was added to give a concentration of 10–50 mM. Some nucleotides require initial addition of DMSO to be soluble (1–5% (v/v)). Commercial caps were obtained lyophilized and dissolved in ddH2O to give a concentration of 10 mM. These initial stocks were then successively diluted in 1/10 dilutions in ddH2O down to 1 nM. For routine analysis, standard mastermix solutions containing Am, m6Am, and N6pAm or GpppG and m7GpppG were prepared using the initial stock solutions. These mastermix solutions were further diluted down to 1 nM as described above.

For the preparation of external calibration curves, typically 7 injections of different volumes from a single concentration of the respective standard or premixed standards were measured. Injections of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5 and 10 µL (dilution pattern: 1:2:2.5:2:2:2.5:2) from lowest to highest volume in subsequent runs were performed. The resulting calibration curves span two orders of magnitude of concentration. For most accurate quantification, all recorded signal intensities should fall within the range of the chosen calibration curve. Since the amount of digested RNA was known and each modification can only occur once per transcript for quantitative cap modifications, an appropriate calibration curve covering the highest possible concentration of analyte was chosen.

For quantification, a worklist containing multiple injections of respective standards or premixed standards, and the samples to be quantified was prepared. To minimize carryover between samples, two blanks were run in between samples. Additionally, before each injection into the system, the needle was automatically washed with ddH2O/MeOH (1:1) in the autosampler.

Linear standard curves were then fitted (Fig. 3) and used for calculation of the relative abundance of different nucleosides using the software Agilent Mass Hunter Quantitative Analysis (for QqQ). Ribose-loss was used as quantifier for all nucleosides, other nucleoside specific transitions were used as qualifier. For caps, the transition of highest abundance was chosen as quantifier, others as qualifiers (see Table 9). Calibration curves with R2 values < 0.99 were not used for quantification, typically occurring at high concentrations due to detector saturation. Instead, samples were diluted and a lower concentration range was chosen.

Fig. 3.

Representative calibration curves for nucleosides (A) or caps (B). Linear functions were fitted to the points.

Enzymatic cap modifications were quantified using Eq. (2). Modified nucleosides (B) or caps were compared with their respective educts (A).

| (2) |

With A being the amount [mol] of the educt and B of the product, respectively.

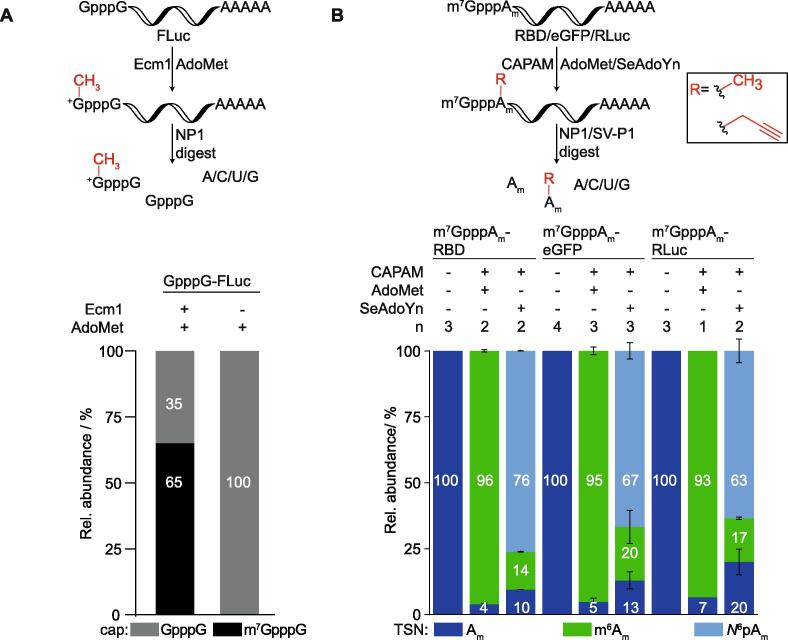

4. Quantification of enzymatic mRNA 5′-cap modification

In this chapter, we describe how to apply this method to quantify the terminal N7-G-methylation of FLuc-mRNA and the N6Am-methylation/propargylation of the TSN of RBD, eGFP, and RLuc mRNA. To this end, respective mRNAs (GpppG-FLuc, m7GpppAm-RBD/eGFP/RLuc) were produced via in vitro run-off transcription, with uncapped transcripts being digested. GpppG-FLuc mRNA was then methylated at the N7-position of the terminal G, using 100 mol% Ecm1. Upon modification, 500 ng of modified and unmodified RNA were digested to nucleosides while the cap was left intact. Quantification of m7GpppG against GpppG is more accurate than m7G against G, which is highly abundant in the transcript. Calibration curves for m7GpppG and GpppG were generated, and samples were subsequently analyzed via LC-QqQ-MS. We found that Ecm1 catalyzed methylation yielded 65% of m7GpppG-FLuc mRNA after 1 h reaction time (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

LC-QqQ-MS quantification of enzymatic cap modifications. For quantification, enzymatically modified RNAs were digested into nucleosides, leaving the cap either intact for Ecm1-catalyzed N7-methylation or digested for CAPAM-catalyzed N6-modification of Am in the TSN position. Samples were then analyzed via LC-QqQ-MS and quantified via external calibration. A) Formation of m7GpppG-FLuc RNA from GpppG-FLuc RNA by Ecm1 (100 mol%) and AdoMet. Unmodified mRNA is shown as control. Reproduced from Ref. [19] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. B) Analysis of long mRNAs (RBD, eGFP and RLuc) after modification. RNAs were modified with CAPAM (200 mol%) using AdoMet or SeAdoYn. Unmodified mRNA is shown as control. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [20] licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

m7GpppAm-RBD/eGFP/RLuc RNAs were methylated or propargylated at the N6-position of Am as TSN, using 200 mol% CAPAM. Here, 50–100 ng mRNAs were completely digested into nucleosides, including the cap, since Am occurs only in the cap of in vitro transcribed RNA. This allows for convenient quantification of m6Am and/or N6pAm against Am, offering better sensitivity compared to caps. With respect to methylation, we found near quantitative modification of all transcripts. Transfer of a propargyl group from SeAdoYn yielded propargylation in the range of 63–76 %. Here, despite using SeAdoYn and omitting AdoMet in the enzymatic reaction, methylation was also observed to a low extent (14–17%). This background methylation without addition of AdoMet results from residual AdoMet bound to CAPAM originating from the expression host [[14], [20]].

5. Discussion

The protocols presented herein comprise the production of differentially capped mRNAs and their enzymatic cap modifications with natural or non-natural moieties. For quantification of these modifications we provide protocols for sample preparation and optimization of respective LC-QqQ-MS methods, including HPLC methods for separation of nucleosides and caps, and optimization of dMRM parameters for respective analytes.

Of note, the instrument detection limit (IDL) for caps (especially GpppG) is significantly higher than for nucleosides, in line with previously reported limits of various caps [31]. This is likely due to better ionizeability of nucleosides compared to caps. There may be potential to improve sensitivity for caps by using different buffer systems such as ammonium bicarbonate in combination with different stationary phases and/or detection in negative mode as shown by Wang et al., Galloway et al., and Hudeček et al., respectively [31], [32], [33].

For quantification, standards of analytes are required for external calibration and establishing dMRM parameters and may require chemical synthesis. However, since external calibration is used, standards are easier to obtain compared to their radio-labeled isotopologs. A general limitation of LC-MS based methods for cap-quantification is the loss of sequence information. If this method is applied to quantify extent of modification in total RNA or poly(A) mRNA instead of RNA transcribed in vitro, no conclusions regarding the identity of modified transcript are obtained [31], [32], [33].

With the development and admission of therapeutic mRNAs, alteration of translational and immunogenic properties have gained considerable importance. Here, approaches comprise optimization of codons and UTR sequences as well as the introduction of non-canonical nucleosides [48], [49], [50]. Additionally, the 5′-cap is an attractive site for modifications, considering its importance to RNA integrity and recognition throughout its life cycle. Here, chemically modified caps have been reported, improving stability and resistance against decapping enzymes or altering translation [17], [25]. In enzyme-based approaches, we recently reported a method for light-activated N7-methylation of GpppG-mRNA using photocaged Ecm1 as a tool for temporal control of translation [19]. CAPAM-catalyzed modifications of Am at its N6-position did alter immunogenicity and translation of transcripts [20]. For both examples, knowledge about the extent of modification is important. Adaptations of this method should also be suitable to quantify different enzymatic modifications in the mRNA cap, i.e. methylation or functionalization of the terminal N2-position or the 2′-O-position of the TSN [51], [52], [53], [54], [55]. We therefore anticipate broad applicability of this protocol to investigating MTase-catalyzed mRNA cap modifications.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 772280). A. R. gratefully acknowledges funding by the DFG (SFB858, RE2796/6-1, RE2796/3-2). We thank A. Ovcharenko and A. M. Böttick for conceptual advice, and A.-M. Lawrence-Dörner for help with protein purification. We thank Chengqi Yi (Peking University) for providing us the plasmid pET28a-PCIF1. D. R. is a member of CiM-IMPRS, the joint graduate school of the Cells-in-Motion Interfaculty Center (CiM), University of Münster, Germany and the International Max Planck Research School – Molecular Biomedicine, Münster, Germany.

References

- 1.Konarska M.M., Padgett R.A., Sharp P.A. Cell. 1984;38:731–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edery I., Sonenberg N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1985;82:7590–7594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Köhler A., Hurt E. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:761–773. doi: 10.1038/nrm2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller-McNicoll M., Neugebauer K.M. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:275–287. doi: 10.1038/nrg3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z., Jiao X., Carr-Schmid A., Kiledjian M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:12663–12668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192445599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuichi Y., LaFiandra A., Shatkin A.J. Nature. 1977;266:235–239. doi: 10.1038/266235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimotohno K., Kodama Y., Hashimoto J., Miura K.I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977;74:2734–2738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonenberg N., Hinnebusch A.G. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcotrigiano J., Gingras A.C., Sonenberg N., Burley S.K. Cell. 1997;89:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niedzwiecka A., Marcotrigiano J., Stepinski J., Jankowska-Anyszka M., Wyslouch-Cieszynska A., Dadlez M., Gingras A.-C., Mak P., Darzynkiewicz E., Sonenberg N., et al. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:615–635. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darzynkiewicz E., Stepinski J., Ekiel I., Goyer C., Sonenberg N., Temeriusz A., Jin Y., Sijuwade T., Haber D., Tahara S.M. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4771–4778. doi: 10.1021/bi00437a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holstein J.M., Anhäuser L., Rentmeister A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016;55:10899–10903. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulias K., Toczydłowska-Socha D., Hawley B.R., Liberman N., Takashima K., Zaccara S., Guez T., Vasseur J.-J., Debart F., Aravind L., et al. Mol. Cell. 2019;75:631–643.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akichika S., Hirano S., Shichino Y., Suzuki T., Nishimasu H., Ishitani R., Sugita A., Hirose Y., Iwasaki S., Nureki O., et al. Science. 2019;363:eaav0080. doi: 10.1126/science.aav0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sendinc E., Valle-Garcia D., Dhall A., Chen H., Henriques T., Navarrete-Perea J., Sheng W., Gygi S.P., Adelman K., Shi Y. Mol. Cell. 2019;75:620–630.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun H., Zhang M., Li K., Bai D., Yi C. Cell Res. 2019;29:80–82. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0117-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sikorski P.J., Warminski M., Kubacka D., Ratajczak T., Nowis D., Kowalska J., Jemielity J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:1607–1626. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandey R.R., Delfino E., Homolka D., Roithova A., Chen K.-M., Li L., Franco G., Vågbø C.B., Taillebourg E., Fauvarque M.-O., et al. Cell Rep. 2020;32 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichert D., Mootz H.D., Rentmeister A. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:4383–4388. doi: 10.1039/d1sc00159k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Dülmen M., Muthmann N., Rentmeister A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021 doi: 10.1002/anie.202100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gholamalipour Y., Karunanayake Mudiyanselage A., Martin C.T. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:9253–9263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leiter J., Reichert D., Rentmeister A., Micura R. ChemBioChem. 2020;21:265–271. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201900590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jemielity J., Fowler T., Zuberek J., Stepinski J., Lewdorowicz M., Niedzwiecka A., Stolarski R., Darzynkiewicz E., Rhoads R.E. RNA. 2003;9:1108–1122. doi: 10.1261/rna.5430403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thillier Y., Decroly E., Morvan F., Canard B., Vasseur J.-J., Debart F. RNA. 2012;18:856–868. doi: 10.1261/rna.030932.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wojtczak B.A., Sikorski P.J., Fac-Dabrowska K., Nowicka A., Warminski M., Kubacka D., Nowak E., Nowotny M., Kowalska J., Jemielity J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:5987–5999. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b02597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kowalska J., Lewdorowicz M., Zuberek J., Grudzien-Nogalska E., Bojarska E., Stepinski J., Rhoads R.E., Darzynkiewicz E., Davis R.E., Jemielity J. RNA. 2008;14:1119–1131. doi: 10.1261/rna.990208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellner S., Ochel A., Thüring K., Spenkuch F., Neumann J., Sharma S., Entian K., Schneider D., Helm M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42 doi: 10.1093/nar/gku733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traube F.R., Schiffers S., Iwan K., Kellner S., Spada F., Müller M., Carell T. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14:283–312. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmid K., Thüring K., Keller P., Ochel A., Kellner S., Helm M. RNA Biol. 2015;12:1152–1158. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1076612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heiss M., Reichle V.F., Kellner S. RNA Biol. 2017;14:1260–1268. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1325063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J., Alvin Chew B.L., Lai Y., Dong H., Xu L., Balamkundu S., Cai W.M., Cui L., Liu C.F., Fu X.-Y., et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galloway A., Atrih A., Grzela R., Darzynkiewicz E., Ferguson M.A.J., Cowling V.H. Open Biol. 2020;10 doi: 10.1098/rsob.190306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hudeček O., Benoni R., Reyes-Gutierrez P.E., Culka M., Šanderová H., Hubálek M., Rulíšek L., Cvačka J., Krásný L., Cahová H. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1052. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14896-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz D., Rentmeister A. RNA Biol. 2012;9:577–586. doi: 10.4161/rna.19818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson J.M., Ujita A., Hill E., Yousif-Rosales S., Smith C., Ko N., McReynolds T., Cabral C.R., Escamilla-Powers J.R., Houston M.E. Curr. Protoc. 2021;1 doi: 10.1002/cpz1.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anhäuser L., Hüwel S., Zobel T., Rentmeister A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thüring K., Schmid K., Keller P., Helm M. Methods. 2016;107:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willnow S., Martin M., Lüscher B., Weinhold E. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:1167–1173. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dudley E., El-Sharkawi S., Games D.E., Newton R.P. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2000;14:1200–1207. doi: 10.1002/1097-0231(20000730)14:14<1200::AID-RCM10>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson C.C., McCloskey J.A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:3661–3668. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadr-Arani L., Mignon P., Chermette H., Abdoul-Carime H., Farizon B., Farizon M. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:11813–11826. doi: 10.1039/c5cp00104h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strzelecka D., Chmielinski S., Bednarek S., Jemielity J., Kowalska J. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8931. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09416-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheehan T.L., Yost R.A. Spectroscopy. 2015;13:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.G. Wells, H. Prest, C. W. Russ IV, Signal , Noise , and Detection Limits in Mass Spectrometry Technical Note (Agilent), 2011.

- 45.N. P. Parra, L. Taylor, Why Instrument Detection Limit (IDL) Is a Better Metric for Determining The Sensitivity of Triple Quadrupole LC/MS Systems Technical Note (Agilent), 2014.

- 46.Beigelman L., Haeberli P., Sweedler D., Karpeisky A. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:1047–1056. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grammel M., Luong P., Orth K., Hang H.C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17103–17105. doi: 10.1021/ja205137d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sahin U., Karikó K., Türeci Ö. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:759–780. doi: 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linares-Fernández S., Lacroix C., Exposito J.-Y., Verrier B. Trends Mol. Med. 2020;26:311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karikó K., Buckstein M., Ni H., Weissman D. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muthmann N., Guez T., Vasseur J.-J., Jaffrey S.R., Debart F., Rentmeister A. Chembiochem. 2019;20:1693–1700. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201900037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schulz D., Holstein J.M., Rentmeister A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52:7874–7878. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holstein J.M., Muttach F., Schiefelbein S.H.H., Rentmeister A. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2017;23:6165–6173. doi: 10.1002/chem.201604816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muttach F., Rentmeister A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:1917–1920. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holstein J.M., Stummer D., Rentmeister A. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2015;28:179–186. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzv011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]