Abstract

Background

ATP citrate lyase is an enzyme in the cholesterol–biosynthesis pathway upstream of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl–coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), the target of statins. Whether the genetic inhibition of ATP citrate lyase is associated with deleterious outcomes and whether it has the same effect, per unit decrease in the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level, as the genetic inhibition of HMGCR is unclear.

Methods

We constructed genetic scores composed of independently inherited variants in the genes encoding ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) and HMGCR to create instruments that mimic the effect of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors and HMGCR inhibitors (statins), respectively. We then compared the associations of these genetic scores with plasma lipid levels, lipoprotein levels, and the risk of cardiovascular events and cancer.

Results

A total of 654,783 participants, including 105,429 participants who had major cardiovascular events, were included in the study. The ACLY and HMGCR scores were associated with similar patterns of changes in plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels and with similar effects on the risk of cardiovascular events per decrease of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level: odds ratio for cardiovascular events, 0.823 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78 to 0.87; P = 4.0×10−14) for the ACLY score and 0.836 (95% CI, 0.81 to 0.87; P= 3.9×10−19) for the HMGCR score. Neither lifelong genetic inhibition of ATP citrate lyase nor lifelong genetic inhibition of HMGCR was associated with an increased risk of cancer.

Conclusions

Genetic variants that mimic the effect of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors and statins appeared to lower plasma LDL cholesterol levels by the same mechanism of action and were associated with similar effects on the risk of cardiovascular disease per unit decrease in the LDL cholesterol level. (Funded by Esperion Therapeutics and others.)

Atp citrate lyase is an enzyme in the cholesterol-biosynthesis pathway located upstream of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR).1 Inhibition of ATP citrate lyase should therefore reduce the plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level by interfering with the same pathway as inhibition of HMGCR with a statin; thus, ATP citrate lyase is an emerging target for pharmacotherapy. It is unclear whether lowering LDL cholesterol levels by inhibiting ATP citrate lyase will reduce the risk of cardiovascular events to the same extent as inhibiting HMGCR with a statin.

Bempedoic acid is an oral ATP citrate lyase inhibitor that has been shown in randomized trials of approximately 12 weeks’ duration to reduce LDL cholesterol levels by up to 30% when used alone and by up to 50% in combination with ezetimibe.2–4 In the Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic Acid, an ACL-Inhibiting Regimen (CLEAR) Harmony trial, the results of which are reported in this issue of the Journal,5 the difference between bempedoic acid and placebo at 12 weeks with respect to the change from baseline in the LDL cholesterol level was 18.1 percentage points in patients who were already receiving high- or moderate-intensity statin therapy. Although the incidence of cardiovascular events in that trial was lower among patients who received bempedoic acid than among those who received placebo, there was also a greater number of deaths from cardiovascular disease and cancer among participants who received the intervention; this raises the question of whether the inhibition of ATP citrate lyase by bempedoic acid or by another drug could be harmful. However, the trial was not designed to detect significant differences in the incidence of major adverse cardiac events or other outcomes.

We sought to estimate the clinical effect of lowering plasma LDL cholesterol levels through inhibition of ATP citrate lyase by comparing variants in ACLY that mimic the effect of an ATP citrate lyase inhibitor with variants in HMGCR that mimic the effect of a statin. Because bempedoic acid is likely to be used in combination with statins or ezetimibe, we also evaluated the effect of ACLY variants in combination with variants in HMGCR and NPC1L1 (Niemann–Pick C1–like 1), which encode proteins targeted by statins and ezetimibe, respectively. This approach has been used to accurately anticipate the results of several randomized trials that have evaluated other lipid-lowering therapies.6–9 The objective of our study was to provide a biologic context for interpreting the results of the completed trials of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors, inform the design of future trials of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors, and anticipate, at least partially, the expected clinical effect of inhibition of ATP citrate lyase.

Methods

Study Population

The study included 470,478 participants with individual-level data, including 367,641 participants who were enrolled in the U.K. Biobank study and 102,837 participants who were enrolled in one of the 14 prospective cohort or case–control studies as part of the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes program of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The study also included 184,305 participants enrolled in one of the 48 prospective cohort, case–control, or cross-sectional studies included the Coronary Artery Disease Genomewide Replication and Meta-Analysis plus the Coronary Artery Disease (CARDIoGRAMplusC4D) consortium and 159,208 participants enrolled in one of the 18 studies included in the Diabetes Genetics Replication and Meta-Analysis (DIAGRAM) consortium for whom summary-level data were available.10–13 Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in each of the contributing studies. A description of the included studies and the genotyping platforms that were used in each study is provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Genetic Instruments

We constructed the genetic score for ACLY by combining all variants within ACLY (and also within 500 kb on either side of it) that were associated with plasma LDL cholesterol levels at a level of significance of less than 0.05, conditional on all other variants included in the score, and that were in low linkage disequilibrium (r2<0.3).14,15 Of the two alternative ACLY variants (or alleles) at each locus, the exposure allele was defined as the allele associated with a lower plasma LDL cholesterol level.15,16 For each study participant, we calculated an ACLY genetic score by adding the number of LDLcholesterol–lowering alleles that he or she had inherited at each variant that was included in the ACLY score, weighted by the conditional effect of each variant on plasma LDL cholesterol levels measured in milligrams per deciliter. For comparison, we also constructed genetic scores for HMGCR and NPC1L1, which encode proteins targeted by statins and ezetimibe, respectively, as previously described.6–8

Study Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome for the study was major cardiovascular events (defined as a composite of the first occurrence of myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, ischemic stroke, or coronary death). The key secondary outcome was myocardial infarction. The primary safety outcome was any type of cancer, and the key secondary safety outcome was diabetes. Changes in plasma lipid levels, lipoprotein levels, and the lipoprotein particle concentration were used to compare the lipidomic signatures of the ACLY and HMGCR scores. A description of the data used in each analysis is provided in Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Study Design and Oversight

The primary analysis measured the association between the ACLY score and changes in plasma lipid levels, lipoprotein levels, and the risk of major cardiovascular events. To assess for an effect modification between ATP citrate lyase inhibition and either HMGCR or NPC1L1 inhibition, we measured the association between the ACLY genetic score and plasma lipoprotein levels and the risk of major cardiovascular events stratified according to the HMGCR and NPC1L1 genetic scores, respectively. To evaluate the combined effect of ATP citrate lyase inhibition with either HMGCR or NPC1L1 inhibition, we evaluated the combined association of the ACLY and HMGCR or NPC1L1 scores with changes in plasma lipid levels, lipoprotein levels, and the risk of major cardiovascular events using a two-by-two factorial mendelian randomization analysis.6–9 Although this study was funded by the manufacturer of bempedoic acid, the sponsor had no access to the data; had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study; had no role in the drafting of the manuscript or its content; and did not participate in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the association of each genetic score with continuous outcomes, including plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels, using linear regression, and we estimated the association of each genetic score with the risk of major cardiovascular events and other dichotomous outcomes using logistic regression. All regression analyses were performed separately in each of the included studies with adjustment for age, sex, and the first five principal components of ancestry for participants with individual-level data, or with the ratio of effect estimates method for studies that provided summary-level data. These effect estimates were then combined across studies in a fixed-effects inverse-variance–weighted meta-analysis to produce summary estimates of effect with the use of a previously reported method that accounts for correlation among variants included in a genetic score.17 To compare the association of the genetic scores with changes in plasma lipoprotein levels and the risk of cardiovascular events, we adjusted each effect-size estimate to scale the results for a standard decrement of 10 mg per deciliter (0.26 mmol per liter) in the LDL cholesterol level.

All analyses were performed with the use of Stata software, version 14 (StataCorp), R software, version 3.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and SNP & Variation Suite software, version 8.1.4 (Golden Helix). A detailed description of the methods, including a description of both mendelian randomization and factorial mendelian randomization, is provided in the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 654,783 participants, including 105,429 participants who had a major cardiovascular event, were included in the efficacy analysis. A total of 656,895 participants, including 37,994 participants who had cancer and 53,145 participants who had diabetes, were included in the safety analysis. Individual participant–level data were available for 470,478 participants, including 44,628 participants who had a major cardiovascular event, 26,646 participants who had cancer, and 26,469 participants who had diabetes (Table 1). The mean age among all 654,783 participants was 62.8 years, and 51.4% were women.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Participants.*.

| Variable | Participants (N = 654,783) |

|---|---|

| No. of participants with available data | |

| Individual data | 470,478 |

| Summary data | 184,305 |

| No. of participants with major cardiovascular events | 105,429 |

| Age (yr) | 62.8±8.0 |

| Female sex (%) | 51.4 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |

| Systolic | 132.1±18.2 |

| Diastolic | 80.9±9.3 |

| Body-mass index† | 27.5±4.9 |

| Diabetes (%) | 4.6 |

| Current smoker (%) | 9.2 |

| Lipid levels (mg/dl) | |

| Total cholesterol | 206.6±39.4 |

| LDL cholesterol | 129.7±32.1 |

| HDL cholesterol | 52.0±15.4 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 154.9±38.3 |

| Apolipoprotein B | 101.4±27.3 |

| Triglyceride level (mg/dl) | |

| Median | 117.6 |

| Interquartile range | 84–163 |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. Data on age and sex were available for all 654,783 participants. Data on baseline characteristics other than plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels were available for participants who were enrolled in the U.K. Biobank cohort and the 14 case–control or cohort studies in the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes program (dbGAP) for whom individual data were available. Data on plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels were available for participants who were enrolled in the dbGAP studies and who had one or more lipid measurements (lipid measurements for U.K. Biobank participants had not yet been released). To convert values for cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.02586. To convert values for triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.01129. HDL denotes high-density lipoprotein, and LDL low-density lipoprotein.

Body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Genetic Scores

Nine independently inherited variants were included in the ACLY score, six in the HMGCR score, and five in the NPC1L1 score (Tables S3 through S8 in the Supplementary Appendix). Although each variant included in the ACLY score was only weakly conditionally associated with plasma LDL cholesterol levels, the ATP citrate lyase score was robustly associated with LDL cholesterol levels. A 1-unit increase in the ACLY score was associated with an inverse-variance–weighted mean decrease of 1.21 mg per deciliter (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94 to 1.48; P = 1.6×10−18) (0.03 mmol per liter; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.04) in the plasma LDL cholesterol level and a concordant decrease of 1.00 mg per deciliter (95% CI, 0.77 to 1.23; P=7.2×10−17) in the plasma apolipoprotein B level. In additional analyses involving 65,976 participants with lipid traits measured with the use of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, the ACLY and HMGCR scores were associated with a similar pattern of changes in the concentration and lipid composition of plasma lipoproteins; this suggests that they lower plasma LDL cholesterol levels by affecting the same metabolic pathway (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Associations of the ACLY and HMGCR Scores with Changes in the Concentration and Lipid Composition of Plasma Lipoproteins.

HMGCR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl–coenzyme A reductase) scores are shown in blue, and ACLY (ATP citrate lyase) scores are shown in red. Data are from analyses involving 65,976 participants for whom lipid traits measured with the use of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy were available. The change for each lipid trait is expressed as a percentage of the change in the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level, with both measurements in SD units. Boxes represent point estimates of effect, and lines 95% confidence intervals. HDL denotes high-density lipoprotein, IDL intermediate-density lipoprotein, and VLDL very-low-density lipoprotein.

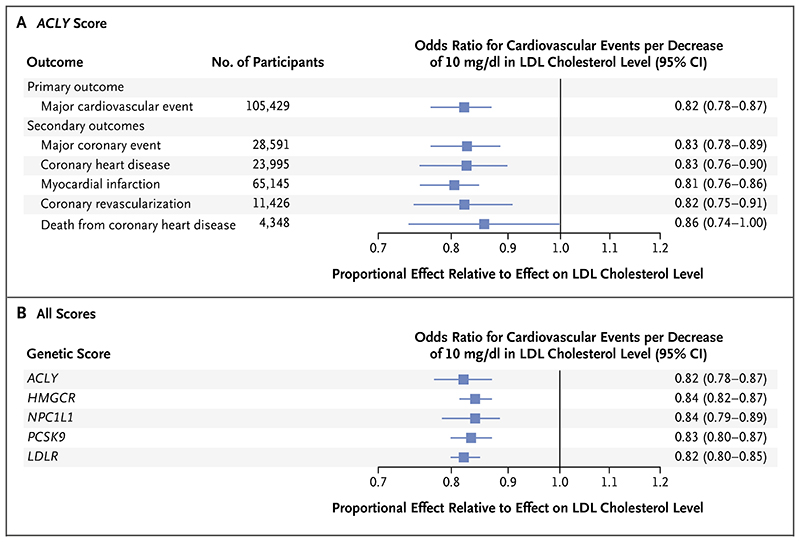

Association of Genetic Scores with Cardiovascular Events

For each decrease of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level, the ACLY score was associated with a decrease of 17.7% in the risk of major cardiovascular events (odds ratio, 0.823; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.87; P = 4.0×10−14) and a 19.4% decrease in the risk of myocardial infarction (odds ratio, 0.806; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.86; P=6.4×10−12). The association of the ACLY score was similar to the association of the HMGCR score with the risk of major cardiovascular events (odds ratio, 0.836; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.87; P= 3.9×10−19) and the risk of myocardial infarction (odds ratio, 0.827; 95% CI, 0.79 to 0.87; P=2.6×10−14) for each decrease of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level.

In addition, the ACLY and HMGCR genetic scores had similar associations with multiple different composite cardiovascular outcomes as well as with the individual components of those composite outcomes, including death from coronary heart disease (Fig. 2A, and Table S9 in the Supplementary Appendix). Furthermore, the association of the ACLY score was also similar to the association of the scores for NPC1L1, proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 (PCSK9), and the gene encoding the LDL receptor (LDLR) with the risk of major cardiovascular events for each decrease of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Associations of the Genetic Scores with the Risk of Cardiovascular Events.

Panel A shows the association between the ACLY score and the risk of cardiovascular events per decrease of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level, and Panel B shows the comparison of the association of the ACLY score and that of the other genetic scores with the risk of major cardiovascular events for the same decrease of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level. Data on major cardiovascular events and myocardial infarctions are from analyses involving the total study sample of 654,783 participants; these analyses included both individual participant–level and summary-level data. Data on major coronary events, coronary heart disease, coronary revascularization, and death from coronary heart disease are from the sample of 470,478 participants for whom individual-level data on these outcomes were available. Associations for all genetic scores are given for a standardized decrement of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level. Boxes represent point estimates of effect, and lines 95% confidence intervals. Major coronary events were defined as the composite of nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, or death from coronary heart disease. Coronary heart disease was defined as the composite of nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease, and coronary revascularization was defined as percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary-artery bypass grafting surgery. LDLR denotes LDL receptor, NPC1L1 Niemann–Pick C1–like 1, and PCSK9 proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9.

Associations of Combined Genetic Scores with Lipids and Major Cardiovascular Events

The associations of the ACLY score with plasma apolipoprotein B levels and the risk of major cardiovascular events did not change in analyses stratified according to the HMGCR and NPC1L1 scores, respectively (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, in two-by-two factorial mendelian randomization analyses, combined exposure to both the ACLY and HMGCR scores, as well as combined exposure to the ACLY and NPC1L1 scores, was associated with independent and linearly additive decreases in plasma LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B levels and corresponding independent and log-additive decreased risks of major cardiovascular events (Fig. 3B and 3C).

Figure 3. Associations of the ACLY Score, Alone and in Combination with the HMGCR and NPC1L1 Scores, with Lipoprotein Levels and the Risk of Major Cardiovascular Events.

Panel A shows the stratified analysis. Panel B shows a two-by-two (2×2) factorial mendelian randomization analysis of ACLY and HMGCR scores. Panel C shows a two-by-two factorial mendelian randomization analysis of ACLY and NPC1L1 scores. Data are from analyses involving 470,478 participants for whom individual participant data, including 44,628 cases of major cardiovascular events, were available. Changes in lipid levels were obtained from 72,411 participants with individual participant data who were enrolled in the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGAP) or the U.K. National Health Service Blood and Transplant INTERVAL study18 and for whom one or more lipid measurements were available. The solid boxes represent point estimates of effect, and lines 95% confidence intervals.

Associations of Acly and HMGCR Scores with Cancer and Other Adverse Outcomes

Neither the ACLY score nor the HMGCR score was associated with an increased risk of all cancers combined or any site-specific cancer (Table 2). Although there was weak evidence that the ACLY score may have been associated with a decreased risk of lung cancer, this finding should be interpreted with caution because the associations between lung cancer and the ACLY score and between lung cancer and the HMGCR score did not differ significantly (Table 2). In contrast, the HMGCR, NPC1L1, PCSK9, and LDLR scores were associated with an increased risk of diabetes, but the ACLY score was not (Table 2, and Tables S10 through S12 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2. Associations of the ACLY and HMGCR Genetic Scores with Cancer and Other Conditions.*.

| Variable | ACLY Variants | HMGCR Variants | P Value for Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Cases | Odds Ratio (95% CI)† | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI)† | P Value | ||

| Cancer | ||||||

| Any cancer | 26,576 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.13 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.11 | 0.17 |

| Lung cancer | ||||||

| Any lung cancer | 11,348 | 0.77 (0.64 to 0.93) |

0.01 | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) |

0.26 | 0.24 |

| Adenocarcinoma of the lung | 3,442 | 0.79 (0.59 to 2.06) |

0.12 | 1.10 (0.95 to 1.26) |

0.21 | 0.19 |

| Squamous-cell lung cancer | 3,275 | 0.71 (0.53 to 0.95) |

0.02 | 1.04 (0.90 to 1.20) |

0.58 | 0.27 |

| Breast cancer | 7,480 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.91 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.49 | 0.49 |

| Prostate cancer | 2,495 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.29 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.47 | 0.32 |

| Lung cancer in father | 27,424 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.66 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.45 | 0.23 |

| Breast cancer in mother | 25,865 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.87 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.58 | 0.58 |

| Conditions other than cancer | ||||||

| Change in blood pressure | ||||||

| Systolic | 470,478 | −0.18 (−0.49 to 0.13) |

0.24 | 0.05 (−0.18 to 0.29) |

0.62 | 0.23 |

| Diastolic | 470,478 | −0.02 (−0.18 to 0.14) |

0.81 | −0.08 (−0.19 to 0.04) |

0.19 | 0.52 |

| Hypertension | 118,064 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.01) |

0.09 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.94 | 0.21 |

| Diabetes | 53,145 | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.00) |

0.05 | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.12) |

3.32×10−6 | 3.03×10−6 |

| Gout | 4,807 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.90 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

0.21 | 0.43 |

Effect sizes are presented as associations between either genetic score and the various outcomes standardized for a decrease of 10 mg per deciliter in the LDL cholesterol level. Analyses of cancer outcomes included 367,641 participants with individual-level data who were enrolled in the U.K. Biobank study. The analysis of lung cancer was supplemented with summary data from 27,209 participants (including 11,348 participants with lung cancer) who were enrolled in the International Lung Cancer Consortium.19 Analyses of noncancer outcomes included 367,641 participants with individual-level data who were enrolled in the U.K. Biobank study. The analysis of diabetes risk is from a combined analysis involving 629,686 participants, including 470,478 participants with individual-level data from the U.K. Biobank and dbGAP studies and 159,208 participants with summary data from the DIAGRAM (Diabetes Genetics Replication and Meta-Analysis) consortium studies.13

The data shown are odds ratios, with the exception of change in blood pressure, which is an effect size.

Discussion

We found that variants in ACLY and HMGCR were associated with similar patterns of changes in the concentration and lipid composition of plasma lipoproteins and had a nearly identical effect on the risk of cardiovascular events for each unit decrease in the LDL cholesterol level. The results of our study thus confirm the mechanism by which ATP citrate lyase inhibition lowers plasma LDL cholesterol levels, and they provide validation for ATP citrate lyase inhibition as a genetic target.

We also found that the lipidomic signature of LDL cholesterol–lowering ACLY variants was similar to that of LDL cholesterol–lowering HMGCR variants, which in turn are associated with a similar lipidomic signature as treatment with a statin.20 This finding strongly implies that inhibiting ATP citrate lyase reduces plasma LDL cholesterol levels in the same way that inhibiting HMGCR with a statin reduces LDL cholesterol levels — that is, by reducing the concentration of LDL particles through up-regulation of the LDL receptor. Therefore, our study provides genetic validation for the proposed mechanism of action by which ATP citrate lyase inhibition reduces plasma LDL cholesterol levels.1

In addition, our finding that ACLY variants associated with decreased LDL cholesterol levels are also associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular events provides genetic validation for ATP citrate lyase as a therapeutic target. More relevant clinically, we found that genetic variants that mimic the effect of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors, statins, and ezetimibe, both alone and in combination, were all associated with similar effects on the risk of cardiovascular events per unit decrease in the LDL cholesterol level. Because long-term exposure to decreased LDL cholesterol levels associated with genetic variants that mimic the action of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors and statins has the same effect on the risk of cardiovascular events per unit decrease in the LDL cholesterol level, it is reasonable to assume that shorter-term pharmacologic reductions in LDL cholesterol levels due to treatment with an ATP citrate lyase inhibitor could have the same effect on the risk of cardiovascular events as treatment with a statin per unit decrease in the LDL cholesterol level. Therefore, we speculate that treatment with an ATP citrate lyase inhibitor, whether used alone or in combination with a statin or ezetimibe, would be likely reduce the risk of cardiovascular events by approximately 20% for each decrease of 39 mg per deciliter (1.0 mmol per liter) in the LDL cholesterol level.21 This speculation assumes that an ATP citrate lyase inhibitor has no off-target effects; this is impossible to determine without large and long clinical trials.

Furthermore, we found that decreased LDL cholesterol levels associated with variants that mimic ATP citrate lyase inhibitors and statins had similar effects on multiple different cardiovascular events, including death from cardiovascular disease. Because randomized trials have shown that reducing LDL cholesterol levels with a statin reduces the risk of death from cardiovascular disease,21 it is reasonable to assume that lowering LDL cholesterol levels with an ATP citrate lyase inhibitor could also reduce the risk of death from cardiovascular disease. Again, this assumption is based on the unknown side effects and off-target effects of such an inhibitor. In addition, because genetic variants that mimic the effect of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors appear to lower LDL cholesterol levels by the same mechanism of action as statins and because randomized trials have shown that treatment with a statin is not associated with an increased risk of cancer or death from cancer, it would seem reasonable to extrapolate that lowering LDL cholesterol levels with an ATP citrate lyase inhibitor would be unlikely to increase the risk of cancer.22 In the specific case of bempedoic acid, we cannot rule out the possibility that a drug-specific effect of this agent, unrelated to its intended mechanism of action, increases the risk of death from cancer.

Our study has limitations. First, as mentioned, genetic variants that mimic the effect of a therapeutic agent cannot anticipate potential drug-specific adverse effects of a therapy that is not related to its mechanism of action (i.e., off-target effects). Second, genetic variants reflect the effect of lifelong exposure to a biomarker on an outcome and therefore cannot be used to estimate the expected effect of short-term pharmacologic changes in that biomarker directly.9,23,24 Third, most major adverse effects tend to be uncommon, leading to imprecise estimates of effect, particularly with genetic variants that have small effects on the exposure of interest. As a result, evaluation of the association between a genetic variant that mimics the effect of a therapeutic agent and numerous potential adverse outcomes can lead to both spurious suggestions of increased risk and false reassurances of safety owing to potential off-target effects, imprecise estimates of effect, the play of chance related to multiple testing, and difficulties in translating the observed effect of lifelong exposure into the expected effect of short-term pharmacologic changes.

In conclusion, we found that genetic variants that mimic the effect of ATP citrate lyase inhibitors and statins appeared to lower plasma LDL cholesterol levels by the same mechanism of action. They were associated with nearly identical effects on the risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer per unit decrease in the LDL cholesterol level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by an investigator-initiated grant from Esperion Therapeutics and by grants from the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre at the Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (to Dr. Brian A. Ference); funding from the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (to Dr. Ray); a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (204623/Z/16/Z, to Dr. Burgess); a grant from Homerton College, University of Cambridge (to Dr. Oliver-Williams); a grant from the European Research Council (to Dr. Butterworth); grants from the Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the NIHR (all to Dr. Danesh); core funding for the INTERVAL study from the NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit in Donor Health and Genomics (NIHR BTRU-2014-10024), the Medical Research Council (MR/L003120/1), and the British Heart Foundation (RG/13/13/30194); and the European Commission Seventh Framework Program (HEALTH-F2-2012-279233).

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Contributor Information

Brian A. Ference, Centre for Naturally Randomized Trials, the United Kingdom, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, the United Kingdom

Kausik K. Ray, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, and Imperial Centre for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention, Department of Primary Care and Public Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, the United Kingdom

Alberico L. Catapano, Department of Pharmacologic and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Milan and Multimedica IRCCS, Milan

Thatcher B. Ference, Centre for Naturally Randomized Trials, the United Kingdom

Stephen Burgess, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, the United Kingdom, Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit

David R. Neff, Michigan State University, East Lansing

Clare Oliver-Williams, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, the United Kingdom

Angela M. Wood, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, the United Kingdom

Adam S. Butterworth, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, the United Kingdom, NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit in Donor Health and Genomics, the United Kingdom

Emanuele Di Angelantonio, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, the United Kingdom, NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit in Donor Health and Genomics, the United Kingdom

John Danesh, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, the United Kingdom, NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit in Donor Health and Genomics, the United Kingdom

John J.P. Kastelein, Department of Vascular Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam

Stephen J. Nicholls, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

References

- 1.Pinkosky SL, Newton RS, Day EA, et al. Liver-specific ATP-citrate lyase inhibition by bempedoic acid decreases LDL-C and attenuates atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13457. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballantyne CM, Davidson MH, Macdougall DE, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel dual modulator of adenosine tri-phosphate-citrate lyase and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase in patients with hypercholesterolemia: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballantyne CM, McKenney JM, Mac-Dougall DE, et al. Effect of ETC-1002 on serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic patients receiving statin therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1928–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballantyne CM, Banach M, Mancini GBJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid added to ezetimibe in statin-intolerant patients with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray KK, Bays HE, Catapano AL, et al. Safety and efficacy of bempedoic acid to reduce LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1022–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ference BA, Majeed F, Penumetcha R, Flack JM, Brook RD. Effect of naturally random allocation to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol on the risk of coronary heart disease mediated by polymorphisms in NPC1L1, HMGCR, or both: a 2 × 2 factorial Mendelian randomization study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1552–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, et al. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2144–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ference BA, Kastelein JJP, Ginsberg HN, et al. Association of genetic variants related to CETP inhibitors and statins with lipoprotein levels and cardiovascular risk. JAMA. 2017;318:947–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ference BA. How to use Mendelian randomization to anticipate the results of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:360–2. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, et al. The NCBI dbGaP database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1181–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–30. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott RA, Scott LJ, Mägi R, et al. An expanded genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Europeans. Diabetes. 2017;66:2888–902. doi: 10.2337/db16-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3555–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1274–83. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu DJ, Peloso GM, Yu H, et al. Exome-wide association study of plasma lipids in >300,000 individuals. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1758–66. doi: 10.1038/ng.3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgess S, Dudbridge F, Thompson SG. Combining information on multiple instrumental variables in Mendelian randomization: comparison of allele score and summarized data methods. Stat Med. 2016;35:1880–906. doi: 10.1002/sim.6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Angelantonio E, Thompson SG, Kaptoge S, et al. Efficiency and safety of varying the frequency of whole blood donation (INTERVAL): a randomised trial of 45 000 donors. Lancet. 2017;390:2360–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31928-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, McKay JD, Rafnar T, et al. Rare variants of large effect in BRCA2 and CHEK2 affect risk of lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2014;46:736–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Würtz P, Wang Q, Soininen P, et al. Metabolomic profiling of statin use and genetic inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1200–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emberson JR, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, et al. Lack of effect of lowering LDL cholesterol on cancer: meta-analysis of individual data from 175,000 people in 27 randomised trials of statin therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ference BA, Yoo W, Alesh I, et al. Effect of long-term exposure to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol beginning early in life on the risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomization analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2631–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies: a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2459–72. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.