An increase in resting heart rate (RHR) is associated with increased mortality risk,1 but the causal role of RHR for cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains unclear. We used the Mendelian randomization design to assess the associations of RHR with coronary artery disease (CAD), atrial fibrillation (AF), and ischemic stroke using summary-level data from the Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome wide Replication and Meta-analysis plus The Coronary Artery Disease consortium’s 1000 Genomes-based genome-wide association study (n=184 305 individuals of primarily European ancestry),2 Atrial Fibrillation Consortium (n=537 409 European-descent individuals, including participants from UK Biobank)3 and MEGASTROKE consortium (n=438 847 European-descent individuals).4 A secondary aim was to examine the association of RHR with 13 CVD outcomes in UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/) (application no. 29202). We restricted the UK Biobank cohort to European-descent individuals and excluded related individuals, low call rate and excess heterozygosity, leaving 367 703 participants for analyses. Studies participating in the consortia and the UK Biobank study had received ethics approval. All participants had provided informed consent.

The hitherto largest genome-wide association study of RHR in up to 265 046 individuals identified 64 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with RHR (P<5×10-8), explaining 2.5% of the variance in RHR.1 Four of the SNPs were unavailable in the outcome datasets, leaving 60 SNPs for analysis. Summary statistics data for the SNPs used in the analyses are available on request.

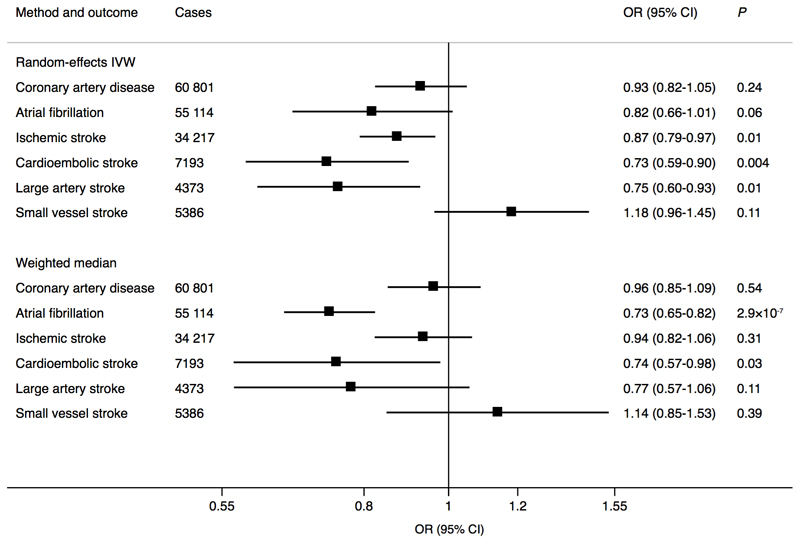

The inverse-variance weighted and weighted median methods were used to obtain odds ratios of each outcome per 10 beats per minute (0.9 standard deviation1) increase in genetically predicted RHR. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between SNPs. The MR-Egger method was used to test for pleiotropy, and MR-PRESSO to identify and correct for outliers. All statistical tests are 2-sided and considered statistically significant at a Bonferroni-corrected P value of <0.0026, adjusting for 19 outcomes (6 in the three consortia and 13 in UK Biobank).

Genetically predicted RHR was statistically significantly inversely associated with AF in the weighted median analysis, and there was suggestive evidence of possible inverse associations (P between 0.0026 and 0.05) of RHR with all ischemic stroke, cardioembolic stroke, and large-artery stroke in the random-effects inverse-variance weighted analysis; no association was observed with CAD or small vessel stroke (Figure 1). There was moderate to substantial heterogeneity between SNPs in analyses of CAD (I2=60%), AF (I2=92%), and cardioembolic stroke (I2=48%) but not large-artery (I2=13%) and small vessel (I2=17%) stroke. No evidence of directional pleiotropy for any outcome was detected (MR-Egger intercept: P >0.05 for all). The MR-PRESSO analysis identified several outlying SNPs (P <0.10) in the analyses of RHR in relation to CAD (n=3 outliers), AF (n=13 outliers), and cardioembolic stroke (n=2 outliers); the outlier-corrected odds ratios (95% confidence interval) per genetically predicted 10 beats per minute increase of RHR were 0.95 (0.86-1.05; P=0.30) for CAD, 0.75 (0.68-0.82; P=5.7×10-8) for AF, and 0.66 (0.54-0.81; P=2.0×10-4) for cardioembolic stroke.

Figure 1.

Associations of genetically predicted 10 beats per minute increase of resting heart rate with coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, and ischemic stroke and its subtypes. The Mendelian randomization analyses were conducted using summarized data on coronary artery disease are from the Coronary Artery Disease consortium’s 1000 Genomes-based genome-wide association study, atrial fibrillation from the Atrial Fibrillation Consortium and ischemic stroke from the MEGASTROKE consortium. CI, confidence interval; IVW, inverse-variance weighted; OR, odds ratio.

In secondary analyses using data from UK Biobank, genetically predicted RHR was inversely associated with AF in the weighted median analysis (odds ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval 0.61-0.87; P=3.2×10-4; n=13 538 cases) but was not significantly associated with the other CVD outcomes. The odds ratios (95% confidence interval) from random-effects inverse-variance weighted analysis per 10 beats per minute increase in genetically predicted RHR were 0.97 (0.87-1.09; P=0.62; n=24 531 cases) for CAD, 0.96 (0.82-1.13; P=0.65; n=4803 cases) for heart failure, 1.09 (0.83-1.43; P=0.55; n=1252 cases) for aortic valve stenosis, 0.75 (0.48-1.18; P=0.21; n=758 cases) for abdominal aortic aneurysm, 0.88 (0.41-1.87; P=0.74; n=231 cases) for thoracic aortic aneurysm, 0.98 (0.80-1.20; P=0.85; n=3554 cases) for ischemic stroke, 1.26 (0.95-1.66; P=0.10; n=1655 cases) for intracerebral hemorrhage, 1.31 (1.01-1.71; P=0.04; n=1834 cases) for subarachnoid hemorrhage, 1.00 (0.86-1.16; P=0.99; n=8891 cases) for deep vein thrombosis, 0.98 (0.84-1.15; P=0.82; n=5097 cases) for pulmonary embolism, 0.83 (0.67-1.01; P=0.07; n=3514 cases) for peripheral arterial disease, and 1.06 (0.99-1.14; P=0.09; n=119 500 cases) for hypertension.

A major strength of this study is the Mendelian randomization design, which compared to standard observational studies, is less susceptible to confounding because genetic variants are unlikely associated with lifestyle behaviors and environmental factors. Additionally, because disease cannot modify genotype, reverse causation bias was prevented. A limitation is that our secondary analyses based on data from UK Biobank had low statistical power. We thus cannot exclude that the lack of association of RHR with some CVD outcomes are due to inadequate power.

An inverse association between RHR and risk of AF has been described previously.5 The mechanisms underpinning the association are unclear but may involve alterations in autonomic tone or subclinical sinus node dysfunction associated with low heart rate. The association between RHR and cardioembolic stroke may be mediated through AF.

In conclusion, this MR study found suggestive evidence of possible inverse associations of genetically predicted RHR with AF and cardioembolic stroke. Genetically predicted RHR was not significantly associated with other CVD outcomes but weak associations cannot be ruled out.

Acknowledgments

Data on genetic associations with coronary artery disease have been contributed by the Coronary Artery Disease consortium’s 1000 Genomes-based genome-wide association study and can be downloaded from www.cardiogramplusc4d.org/. Data on genetic associations with atrial fibrillation have been contributed by the Atrial Fibrillation Consortium and can be downloaded from http://www.broadcvdi.org/. Data on genetic associations with ischemic stroke have been contributed by the International Stroke Genetics Consortium and can be downloaded at www.cerebrovascularportal.org/. The MEGASTROKE project received funding from sources specified at http://megastroke.org/acknowledgements.html.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forte) and the Swedish Research Council. Stephen Burgess is supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Grant Number 204623/Z/16/Z).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Eppinga RN, et al. Identification of genomic loci associated with resting heart rate and shared genetic predictors with all-cause mortality. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1557–1563. doi: 10.1038/ng.3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikpay M, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roselli C, et al. Multi-ethnic genome-wide association study for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1225–1233. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik R, et al. Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nat Genet. 2018;50:524–537. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morseth B, et al. Physical activity, resting heart rate, and atrial fibrillation: the Tromso Study. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2307–2313. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]