Abstract

Research on transmasculine people’s health is scant globally, including in India. We explored transmasculine people’s experiences in affirming their gender in family and social spaces, and how those experiences impact mental health. In 2019, we conducted four focus groups (n=17 participants) and 10 in-depth interviews with transmasculine people in Mumbai and Chennai. Data analyses were guided by minority stress theory and the gender affirmation model. Within family, the pressure to conform to assigned gender roles and gender policing usually began in adolescence and increased over time. Some participants left parental homes due to violence. In educational settings, participants described the enforcement of gender-normative dress codes, lack of faculty support, and bullying victimisation, which led some to quit schooling. In the workplace, experiences varied depending on whether participants were visibly trans or had an incongruence between their identity documents and gender identity. Everyday discrimination experiences in diverse settings contributed to psychological distress. Amidst these challenges, participants reported resilience strategies, including self-acceptance, connecting with peers, strategic (non)disclosure, and circumventing gendered restrictions on dress and behaviour. Interventions at social-structural, institutional, family and individual levels are needed to reduce stigma and discrimination faced by transmasculine people in India and to promote their mental health.

Keywords: transgender men, gender identity, discrimination, coping, psychological distress

Introduction

Transmasculine people or trans men are those who were assigned the female sex at birth and who identify as men or masculine. Ancient Indian treatises and popular Hindu mythologies include stories of people whom we would now call transmasculine (Pattanaik 2014). For example, in one interpretation of the Mahabharata, a classic Indian Epic, a key character named Sikhandi is a warrior-princess who becomes a man to avenge his father’s death (Custodi 2007). In the Kama Sutra, the term tritiya prakriti or people of ‘third nature’ (Vatsyayana 1994, 82) is used, as well as purusha rupini, translated by some authors as ‘a woman in the form of a man’ (Greenberg 2008, 307). While there are limitations in historicising present-day constructions of gender, this suggests that the ancient peoples of the Indian subcontinent were aware of transmasculine people. However, the current public understanding of transmasculine people in India is rather rudimentary, particularly in contrast to the increasing public understanding of transgender women (Chakrapani, Newman and Noronha 2018). Further, India is still largely characterised by patriarchal expectations of adherence to rigid gender norms (e.g. about how a man or woman should behave) (Bannerji 2016).

Globally, the literature on transmasculine people’s health is scant, with existing studies largely conducted in Western countries. In a systematic review of 104 peer-reviewed articles on trans health published between 2008 and 2014, only 20 came from lower- and middle-income countries, of which only three reported data on trans men (Reisner et al. 2016). Publications on trans health in India are largely focused on HIV-related issues among trans women (Chakrapani, Newman and Shunmugam 2020). A few articles on sexual minority women in India have included people with non-binary or ‘gender fluid’ identities (Bowling et al. 2020, 503) and a few non-peer-reviewed reports on sexual and gender minorities have included transmasculine people (Shah et al. 2015; Mingle 2016). A recent scoping review on transmasculine health in lower- and middle-income countries from 1999 to 2019 found only two peer-reviewed studies with data from India; neither study had a primary focus on transmasculine health (Scheim et al. 2020).

Evidence from Western countries indicates that transmasculine people are at higher risk for mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and self-harm, compared to cisgender men and women, as documented in population-based studies and systematic reviews (Reisner et al. 2016; White Hughto, Reisner and Pachankis 2015; Downing and Przedworski 2018). Minority stress theory was originally developed to explain mental health disparities among sexual minorities (Brooks, 1981; Meyer 1995, 2003) and has been extended to gender minorities (Hendricks and Testa 2012; Testa et al. 2015). Within the minority stress framework, mental health disparities are viewed as secondary to stigma and discrimination (White Hughto, Reisner and Pachankis 2015). The model posits that four types of external stressors (discrimination, rejection, victimisation and gender non-affirmation) lead to poorer mental health outcomes, both directly, as well as indirectly via internal stressors (internalised or self-stigma, anticipated stigma and concealment). Minority-specific resilience factors (community connectedness and pride) are hypothesised moderators of the effects of both external and internal stressors. Resilience is a multi-faceted concept; sources of resilience are identified at individual, interpersonal and community levels (Aburn, Gott and Hoare 2016; Bry et al. 2018). In this paper, we use Fergus and Zimmerman’s (2005, 399) definition of resilience: ‘the process of overcoming the negative effects of risk exposure, coping successfully with traumatic experiences, and avoiding the negative trajectories associated with risk’.

Building on the recognition of gender non-affirmation as a minority stressor for trans persons (Sevelius 2013), trans health scholars have emphasised the importance of gender affirmation as a multidimensional construct involving social (e.g. use of one’s chosen name), legal (e.g. identity documents), psychological (e.g. self-acceptance) and medical (e.g. hormone therapy) dimensions (Reisner et al. 2016). Studies, primarily from Western settings, have found these forms of gender affirmation to be associated with better mental health (Meier et al. 2011; Russell et al. 2018; Scheim, Perez-Brumer and Bauer 2020).

To address the critical knowledge gap on the experiences of transmasculine people, we used minority stress theory and the gender affirmation model to explore the following research questions: 1) what are the experiences of transmasculine people in affirming their gender identity/expression in family and social spaces, including educational settings and workplace; 2) what consequences do such experiences have for their mental health; and 3) what resilience resources are available to cope with discrimination experiences?

Methods

From January to March 2019, we conducted focus groups (FGs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs) among a purposive sample of self-identified transmasculine persons recruited through community agencies in Chennai and Mumbai. These agencies have been providing HIV-related and mental health services for sexual and gender minorities for over a decade. Maximum diversity sampling, a type of purposive sampling, was used to increase the diversity of the participants in relation to age, education, employment, and gender transition status (Patton 2015). Inclusion criteria for the participants were: age 18 years and above, self-identified as a transmasculine person, and ability to provide written informed consent. Recruitment was conducted by word-of-mouth through trained peer recruiters from community agencies who suggested a list of potential participants. From that list, eligible participants from different age groups and educational and employment statuses were invited to participate. Each FG or IDI lasted for about 60 to 90 minutes. Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of the Humsafar Trust and Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in India. Participants received INR 500 (7 USD) as compensation for their time and travel expenses.

Data collection

We developed a semi-structured topic guide (a list of open-ended questions and probes) to explore the following domains: experiences – especially stigma, discrimination and violence – in diverse settings such as the family, schools and workplace (nature of discrimination, perpetrators, reactions and consequences, redressal mechanisms); mental health issues (depression, anxiety, alcohol-related problems) and their connection to discrimination and violence; resilience resources such as family, peer and social support; and resilience strategies such as strategic disclosure or non-disclosure of gender identity. Four trained research staff, two of whom identified as trans men, conducted FGs and IDIs in participants’ native languages (Tamil in Chennai and Hindi or Marathi in Mumbai). Each FG was co-led by a moderator and a co-moderator, and each IDI was administered by one of the four staff. Questions were added to the topic guide in an iterative process based on data collected from initial FGs and IDIs (Stake 2010).

Data analysis

Focus groups and IDIs were digitally recorded and translated into English by professional translators. A codebook was developed based on a priori codes derived from the topic guides and theoretical frameworks (minority stress and the gender affirmation framework). Inductive/emergent codes identified from the text were added to the codebook for further coding and categorising. As we used both a priori codes and emergent codes (Blair 2015; Kreiner 2015) to analyse and interpret data. We combined framework analysis (Ritchie and Spencer 1994) with techniques (e.g. emergent/inductive coding, constant comparison) adapted from grounded theory approaches (Corbin and Strauss 2015; Charmaz 2014). Differences in coding and interpretation were discussed among data analysts and senior investigators, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Themes were identified by looking for similarities, differences, and other relationships between categories. Further, process tracing techniques (Mahoney 2012; Bennett and Checkel 2015) were used to identify causal pathways that were inferred or articulated in participants’ narratives in terms of how one event led to another (e.g. how discrimination contributed to psychological distress). We adapted a critical realist perspective, using both categorising strategies and contiguity-based connecting strategies to identify potential causal connections between elements and events in the transcripts or between two categories (Maxwell 2012). The validity or trustworthiness of the findings is improved by the use of methods triangulation (interviews and focus groups) and researcher triangulation (Denzin and Lincoln 2018). IDI participants were assigned pseudonyms for the presentation of results in order to protect confidentiality. Focus group participants were not assigned pseudonyms because it was not always possible to identify each individual speaker in group conversations, rather they were identified by FG number and city.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Table 1 describes participants’ demographic characteristics. Participants’ (n=27) mean age was 25 years (SD 3.0). All the Chennai participants identified themselves as Thiru Nambi (an indigenous term for transmasculine persons) and all Mumbai participants identified as ‘trans men’ (English-language term).

Table 1. Data collection details and sociodemographic characteristics of study participants (N = 27).

| Characteristics | Total | Chennai | Mumbai |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of focus groups | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Number of in-depth interviews | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Total number of participants in focus groups and in-depth interviews | 27 | 15 | 12 |

| Age in years [Mean (SD)] | 25.0 (3.0) | 25.6 (1.9) | 24.1 (3.9) |

| Income in INR [Mean (SD)] | 14600 (5879) | 12846 (3362) | 17857 (8234) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 24 | 13 | 11 |

| In a committed relationship with a cisgender woman | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Primary school (5th grade) | 2 | 2 | |

| Middle school (8th grade) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| High school (10th grade) | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Higher secondary school (12th grade) | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Secondary school diploma | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| College | 11 | 7 | 4 |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Private company | 16 | 12 | 4 |

| Self-employed | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Gender identity | |||

| ‘Trans man’ (English term) | 12 | 12 | |

| Thiru Nambi (indigenous Tamil term) | 15 | 15 | |

| Living status | |||

| Hostel | 6 | 6 | |

| Alone | 1 | 1 | |

| With parents | 15 | 6 | 9 |

| With woman partner | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| With transmasculine friends | 3 | 2 | 1 |

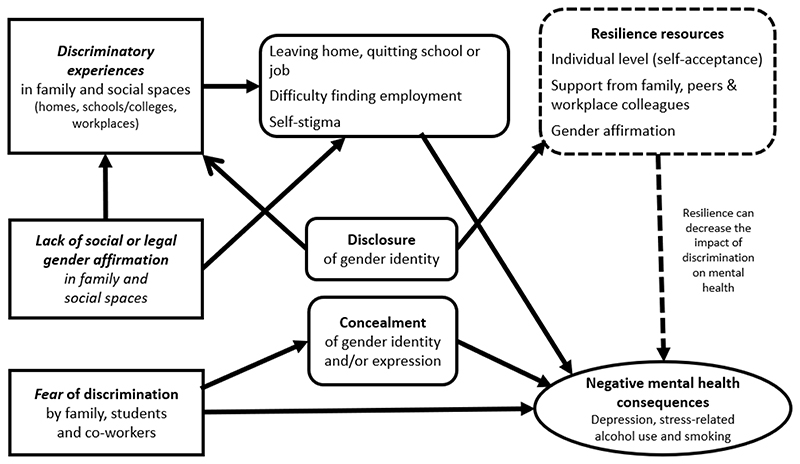

Figure 1 summarises the conceptual model developed from the findings. It shows that stigma and discrimination in family and social spaces or lack of gender affirmation may lead to negative consequences such as loss of education and employment, and negative mental health consequences; and resilience resources such as support from family, peers and friends decrease the impact of discrimination on mental health.

Figure 1. Influence of stigma/discrimination and lack of gender affirmation on mental health of transmasculine persons: a conceptual model based on qualitative findings, guided by minority stress theory and the gender affirmation model.

Navigating family spaces

Participants reported that they started to question their gender identities when they were as young as 4 or 5 years old: ‘Why do I feel like a boy?’, ‘What is happening to me?’ or ‘Why am I different from other girls?’. Participants recalled exhibiting masculine traits and behaviours during early childhood. None reported having experienced negative reactions from their family members for exhibiting such behaviours in early childhood. However, as participants entered adolescence, many family members started pressuring them to adhere to assigned gender roles. For example, an IDI participant stated:

When I entered 8th grade, I was forced to add one thing inside my T-shirt because my upper body started growing. I asked my mother, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Similar to the baniyan [male vest] worn by your [boy] friends, you need to wear it’. They restricted me from going to the swimming class. They told that I was not allowed to go anywhere with anyone else other than my close friends. I could not accept that. (Karan, Mumbai)

This participant’s experience reflects the restrictions posed on persons assigned female at birth, in general, in India, when they approach pubertal age. For transmasculine persons, such restrictions may be particularly distressing as they conflict with gender identity.

Participants reported concealing their masculine gender expression at home due to fear of negative reactions from family. For example, one FG participant stated: ‘At home, I stay like a girl. But when friends call me over the phone, I reply like a boy. Sometimes my mother used to ask me, “You are a girl, but why are you talking like a boy?”‘ (FG-1, Mumbai). Similarly, participants were frequently fearful of disclosing their gender identity to parents, and thus concealed their gender identity. A participant in a different FG stated: ‘Earlier, although I felt like a boy, I was scared of telling it to my parents. My parents used to ask me “Why you behave like a boy?” I wanted to tell. But I was scared.’ (FG-2, Mumbai). Participants experienced stress related to concealing their gender identities and having to pretend to be a girl or woman: ‘I cannot live my life openly because of my family and others. When I walk like a boy, sometimes I hesitate, worrying about what people will think.’ (Dev, Mumbai)

Disclosing gender identity to one’s parents or other family members could elicit non-affirming responses and even violence. An IDI participant said, ‘One day, I told my mother…I want to change myself like a boy. She replied that because I was roaming with boys, I felt like that, and threatened to beat me if I kept talking like that’ (Kumar, Chennai). Another participant reported:

I told them [parents] that I want to be a man. My father, mother and everyone started beating me, tonsured [shaved his head] and tied my hands. They kept me nude in a room for a whole day and forced me to wear women’s clothes and to do household work. One day I left my home. (Mani, Chennai)

In addition to verbal or physical violence, some participants feared that disclosure would lead to negative consequences like forced marriage or eviction. A few trans men from rural areas stated that conservative attitudes among rural communities increased family pressure to conform to gender norms and made coming out openly as a trans man more challenging. Similarly, fear of being ridiculed by relatives and society at large led parents to prevent their children from behaving in ways that are considered masculine or inappropriate:

My father asked me, ‘Why did you cut your hair?’ He insisted me to keep my hair long. He said, ‘We are Maharashtrians. What will the villagers tell if they see you?’ He asked me to be like my sisters. (Dev, Mumbai)

A FG participant further explained that social pressure might compel parents to enforce gender-conforming behaviour: ‘Even if family members are knowledgeable, they are not ready to accept this. They were worried about neighbours and relatives. They start questioning us – “Why are you dressing like this? What happened to you?” They force us to get married.’ (FG-2, Chennai)

Due to lack of parental acceptance, some participants voluntarily left home once they received sufficient education and had the capacity to support themselves. A few participants tried to balance family expectations with the desire to freely express their gender identity, demonstrating resilience as well. For example, a participant explained that as an adolescent he negotiated with his parents to wear salwar-kameez (ethnic wear for girls consisting of a long shirt and loose pyjama-like trousers) and payal (anklets), and to keep his hair long, when going to see relatives in his village, but in turn to wear his choice of clothing at home. However, the same participant also reported that his parents took him to a baba (saadhu or guru) to exorcise the ghost that was believed to be responsible for his masculine behaviours.

While most participants reported family nonacceptance after disclosure of gender identity, a few reported mixed reactions. For example, one trans man, whose sister rejected his gender identity, received support from his father. A few parents who initially rejected or exhibited violent behaviour later became supportive. For example, a trans man described how his relationship with his parents had changed over time, although they had taken him to a psychiatrist for possible conversion therapy:

At the age of 10, I understood the change within me and informed my parents. But they did not accept. Years later, they started arranging for my marriage. I told that guy that I am a trans man and asked him to inform my family that he did not like me. Instead he asked my family members to take me to a psychiatrist. My parents took me to a psychiatrist. Upon my request, the psychiatrist revealed my identity to my family. They did not accept immediately. But eventually they accepted me. (FG-1, Chennai)

Lack of support from family members, misgendering and lack of freedom in doing things that are taken-for-granted for a cisgender man led some participants to become distressed and to consume alcohol or drugs to cope:

One day he [elder brother] found me with drugs…maybe cocaine…My friends used to sit in a circle and take it with an ATM card…They insisted me to take it…I kept on meeting them and kept on taking it. There were many reasons…First, I did not have family support. Second, my elder brother – whenever I go to house – would start giving me lectures. He would be like ‘Here she comes. She does not have any timetable, and she comes home at 2 in the night’ this and that…So I thought let me try it so…I would go home and sleep…But after that I got so addicted…[Later] I quit it (could not afford) and started drinking. (FG-2, Mumbai)

Although alcohol or drug use and smoking were described as responses to stress and discrimination, a few trans men reported alcohol use as a sign of masculinity or just for ‘fun’ or ‘jolly’. For example, an IDI participant said, ‘A few of us drink to maintain status. I am a tomboy. I stay this way. I need to be in style. I need to consume alcohol and smoke cigarette. This kind of thinking is there [among transmasculine persons].’ (Tejas, Mumbai)

Navigating social space

Educational settings

Some participants described discrimination or bullying in schools and colleges. One trans man recollected that despite knowing his gender identity, some faculty would misgender him to make him feel uncomfortable.

In my college, when they [faculty] got to know about me, they tortured me a lot. They knew that I don’t like to be called ma’am. They used to do it intentionally…in front of others. I used to feel very angry. (Kevin, Mumbai)

Another trans man shared how he had been bullied by a male classmate, which eventually made him stop going to school:

I faced a lot of problem from a classmate. He asked me – ‘Why are you using the male toilet? Are you a male? Show me your parts…You are a ussu, ombodhu [derogatory terms]. Why are you coming to school?’ I got very angry and hit and broke his head. I stopped going to school. (FG-1, Chennai)

Participants also faced dress code restrictions in schools that acted as a barrier to gender self-expression:

I hated wearing a girl’s uniform. When I was studying 12th standard, as per the school policy, girls should wear salwar kameez [ethnic dress for girls/women] and dupatta [shawl] as uniform. I was not happy wearing them. I preferred wearing shorts, T-shirts, shirts and pants. As soon as I returned from school, I used to remove and toss away the [girl’s] uniform. (Tejas, Mumbai)

These experiences highlight cisnormativity and the lack of recognition of gender diversity in educational institutions. The pressure to wear clothes that do not align with one’s gender identity is likely to be stressful.

Workplace

Many participants reported having experienced discrimination from their supervisors or co-workers based on their gender identity or expression. Discriminatory practices included name-calling, misgendering, mistreatment, denial of promotion, and social isolation. For instance, participants reported that antagonistic or insensitive comments contributed to self-stigma and stress:

I was looked at differently because of the way I dress. I did not like wearing churidar or leggings. My co-workers teased me for my ‘dressing sense’…They make me feel wrong…They say I am doing something wrong and that I won’t have a future and family or kids. (Victor, Chennai)

You cannot concentrate on your work and only one thing goes in your mind that my colleague has said this to me…His work cannot be perfect also. It creates more pressure on him… affects you a lot professionally. (Tejas, Mumbai)

Participants who had voluntarily disclosed their gender identity to co-workers experienced both positive and negative outcomes. Positive outcomes included increased understanding, acceptance and support. Negative reactions, however, impacted on their self-esteem:

I told my co-workers about me. Initially, they thought it was weird. But when I explained to them that it is not a psychiatric problem, with examples from videos on YouTube, they started accepting me. I believe that if we explain it to the general public they will accept. (Raja, Chennai)

Participants who were consistently perceived as men preferred not to come out openly at their workplace as they did not see any reason for doing so and because they anticipated discrimination. For example, a trans man said, ‘After taking hormone injections, my appearance has completely changed. It is difficult for others to identify me [as trans]. There is no need to disclose our identity.’ (Raja, Chennai). Similarly, another participant stated: ‘In my office, they don’t know about me. They consider me as a man. I also want them to treat me as a man. If I say I am a trans man, then I may be discriminated [against].’ Although this decision to strategically not disclose gender identity could be interpreted as resilience, concealment of gender history may be stressful as individuals need to remain vigilant, with an underlying fear of negative consequences if outed.

A lack of gender-inclusive workplace policies and limited knowledge about transgender issues made the work environment unsafe for transmasculine persons:

For those who are already working and have undergone transition, they might have confusion – ‘How will the company accept me? As a male or a female?’ Even if they were placed under the male category, they need to change their ID [identity] proof and other documents. That will be a problem. (FG-2, Chennai)

Some participants reported having to compromise in relation to workplace dress codes, especially if they had dependant family members:

We often think seriously should we wear a saree [as per the workplace policy] or should we see our future? … We can’t sacrifice our future by getting worried about our issue (meaning ‘gender expression’)… We cannot leave a job after one week. We may not be then able to give anything [money] to our family and they will lose confidence in us. (FG-1, Mumbai)

Participants also reported facing discrimination during job interviews and hiring processes, which led them not to take up jobs for which they were otherwise qualified.

I went for a job interview [in the film industry]. At that time, my hair was short, and I was wearing pants and a shirt. However, in my biodata, my gender was stated as a woman. This guy [interview panellist] asked me – ‘If you are a girl why do you wear boy’s clothes?’ …. Although I got the job, I did not go back. Because today this person questioned me about my clothes, tomorrow he may question about something else. (Tejas, Mumbai)

Here, a lack of gender-congruent identity documents outed the participant to a potential employer, who in turn inappropriately questioned him, which ultimately prevented him from taking up the job. Another participant described how difficult it was to find employment and how he became anxious and used alcohol to cope:

I had run away from my home. They were going to marry me off…Then I settled here and…my friend [a girl roommate] offered me drinks one or two times. I was in tension as I could not get any job - so I drank. Then I got addicted to it. (FG-2, Mumbai)

Stress related to unemployment and employment discrimination may be compounded by cultural expectations that a man provides for his family:

Now I am 25 [years old]. I am not able to support my family financially. I am sad about that thing. I am lucky that my family accepted my wife, my girlfriend. She is staying with us. I am not able to fulfil the [financial] requirements of my family. I am making them sacrifice their requirements for my dreams of becoming a trans man. (FG-2, Mumbai)

Society

Several participants reported that a lack of understanding and awareness about trans men within wider society was a barrier to openly expressing their gender identity, which may contribute to psychological distress:

I would say that the public is not aware of trans men. Society includes everyone -family, friends, relatives, colleagues, etc. They don’t consider us as trans men. Instead, they think that we are lesbians. (FG-2, Mumbai)

Given the gendered nature of many public places, trans men reported facing problems when they used men’s restrooms or stood in queues for men (e.g. security clearance line before entering malls):

Once I went to a washroom in [a train] station. My girlfriend went into the lady’s toilet and I was going into the gent’s toilet. A man said, ‘Don’t go there, go there’. I asked, ‘Why?’. He said, ‘You are a girl’. I said, ‘Did you see? How did you decide that I am a girl?’ He said, ‘By looking at your face’… Actually, I went into depression for some time. (Karan, Mumbai)

Those participants who were perceived as cisgender men by others (mostly those on hormone therapy), however, did not report facing problems or intrusive questions: ‘Society will accept us. They will be seeing us [as] a boy so there will be no problem’ (Asif, Chennai). Thus, access to medical gender affirmation procedures helped some transmasculine persons to face less discrimination.

A few participants reported that they experienced discrimination and lost friends when their gender identity was revealed:

My close friends said that ‘You are a transgender, you can’t do anything, you only clap [equating them with hijras who clap in a particular way] and do sex work’. I felt very sad. They are my close friends and they are the ones who hurt you the most. (Dev, Mumbai)

Thus, loss of friendship and gender non-affirmation even by ‘close friends’ became a source of distress for some participants.

Resilience resources

Some trans men received support from their family, partners, cisgender friends or trans peers during the process of social and medical gender affirmation, which helped to mitigate the challenges they faced:

In my family, everyone agreed, and nobody had any objection when I expressed my feeling of getting operated [on] …My girlfriend informed her parents that this type of person is there. He is going to get the operation done, and I want to marry him. To my surprise, her parents also agreed. I was quite shocked...They said that we are happy with your happiness. (Tejas, Mumbai)

Social support from family and friends were perceived as protective against mental health issues and to contribute to increased self-esteem and self-acceptance: ‘If we get support from the family, we will never get to worry about outsiders. Family is the most important thing. If our family does not have any issue with us…we will not be scared of anyone.’ (FG-1, Mumbai)

For many participants, friends, both cisgender and transgender (some through online support groups), were their main source of support and comfort in times of distress:

I have a best friend who supports me both emotionally and financially from start to end. He is the one to whom I have disclosed about my identity. He was very supportive and understanding. Even during my surgery, he supported me financially. (Kevin, Mumbai)

Some trans men received support in the workplace. For example, one trans man shared that he had a supportive boss: ‘I had disclosed my identity to my showroom owner. Till date, he has not asked me anything and has not revealed my identity to others. He treats me as a man.’ (FG-1, Chennai).

In addition to these resilience resources, as noted earlier, the ability to negotiate with family members to wear one’s preferred clothing, moving to other locales to seek support and safety, and taking decisions on when and to whom to reveal one’s identity reflect resilience among transmasculine participants.

Discussion

Transmasculine people in India face numerous challenges in expressing and negotiating their gender identity and expression within family and social spaces, including educational settings, workplaces and neighbourhoods. We used minority stress and gender affirmation models to analyse how stressors and resilience resources in the family and social spheres were related to mental health (Figure 1). Our findings also suggest that fear of discrimination and anticipated stigma may lead to concealment of gender identity/expression, with negative mental health consequences (Rood et al. 2017). Even though disclosure of gender identity helped in obtaining support from family and trans communities, disclosure (voluntary or involuntary) also led to discrimination by others, which in turn led to negative mental health consequences. Lack of social or legal gender affirmation in family and social spaces also contributed to distress, as some had to leave home, quit school, or terminate their employment, while family and social support (resilience resources) decreased the negative impact of stress on mental health. Resilience was demonstrated by self-acceptance, strategic disclosure of gender identity, and transmasculine persons’ ability to find creative ways to bypass or negotiate rules for dress and behaviour.

Family (non)acceptance and its link to mental health was a key theme in the study. Other research that included 12 trans men from North-eastern India reported that only three of them had family support (Hebbar and Singh 2017). Family (non)acceptance may have particular salience in a culture where subordination to parents and elders is expected. Efforts to make the parents understand and accept their names, pronouns, and ways of dressing and behaving were a constant struggle for many participants, and likely to have resulted in emotional exhaustion. Given the central role of the family, and young transmasculine persons’ dependency – both emotional and financial – on their parents, participants had to carefully balance affirming their gender identities and avoiding negative family reactions including violence, restrictions on mobility, and loss of support for education. These findings on the importance of family support, and its role in mental health, are consistent with findings from studies of trans women (Ganju and Saggurti 2017) and sexual minority women (Bowling et al. 2018) in India. Participants reported that family nonacceptance could be due to fear of negative reactions from the society and loss of ‘family prestige’, similar to ‘stigma by association’ reported by other studies among sexual and gender minorities in India (Chakrapani and Dhall 2011; Tomori et al. 2018) and other collectivistic cultures (Jhang 2018; Tamagawa 2018). The reasons behind family (non)acceptance need to be further explored in future research (Parker et al. 2018).

Whether in family, educational institutions, or workplaces, transmasculine persons encountered both support and rejection. Participants’ accounts revealed the widespread cisnormative assumptions of the society, including regulations and norms on what kind of clothes to wear, how long hair should be, and what behaviours are appropriate for a person of a particular assigned sex. Daily engagement with this ongoing gender policing from all spheres of life, and across developmental life stages, takes a toll on the mental health of transmasculine persons (Rood et al. 2017). Even in the absence of overtly violent behaviour from others, misgendering or inappropriate comments are forms of microaggression, which have been shown to harm mental health over the long term (Russell et al. 2018).

In addition to overt discrimination, findings reveal the impacts of structural violence (social structures or institutional assumptions or norms that perpetuate inequality; Galtung 1969) in the form of legal non-recognition of gender. Despite the 2014 Supreme Court judgement that trans people can self-identify as a man, woman, or transgender, without need for any medical procedures, obtaining government-issued identity cards in one’s affirmed gender remains a struggle. The Transgender Persons Act, introduced in 2019 (Ministry of Law and Justice 2019), has clauses against discrimination of transgender people by any person or establishment. However, the Act and subsequent rules have been critiqued for not allowing self-identification as a man or woman without medical intervention, among other concerns, and effective enforcement of the Act has yet to be seen (Jain and Rhoten 2020). Transgender welfare boards established by several State governments in India seem to focus primarily on the issues of trans women, not trans men (Chakrapani 2012). Even if a transmasculine person might be perceived as a cisgender man in the workplace, the incongruence between his stated gender and his identity card might reveal his transgender status, resulting in loss of job opportunities. Given that financial security is essential for supporting oneself and one’s family, some transmasculine persons with incongruent gender identity cards are in a double-bind – whether to disclose one’s gender identity and risk not getting or losing a job, or to painfully hide one’s gender identity to secure or retain a job but suffer mentally. Impression management strategies that involve succumbing to institutional dress codes that are at odds with one’s gender identity have been shown to increase stress and affect mental health (Brewster et al. 2014), The need for financial security seems also to be tied to the expectation that men should support their family members, and thus not having a job or not supporting their family represents a lack of masculinity.

Certain coping strategies reported by participants, such as heavy alcohol use or smoking, ultimately affect physical health. High levels of alcohol use and smoking have been reported among trans men from high-income countries (Scheim, Bauer and Shokoohi 2016; Gilbert et al. 2018; Alzahrani et al. 2019), potentially linked to being seen as a masculine trait or a stress coping strategy (Reisner et al. 2015); participants in the present study endorsed both of these explanations. In the presence of support from family or friends, participants in this study reported not engaging in such coping behaviours.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. While the goal of qualitative research is not to generalise (in a statistical sense), our intention was to explore a range of experiences faced by transmasculine people from two cities in India. Given the exploratory nature of the study, our sample size of a total of 27 participants may be sufficient to have achieved ‘data saturation’ (no new information from additional interviews and focus groups) (Trotter 2012). Participants were recruited through community agencies working with sexual and gender minorities (although primarily working with transfeminine persons) in two cities, and thus receiving some level of support; the experiences of transmasculine persons who are not affiliated with community agencies may be different. All participants identified as trans men or thiru nambi, and the experiences of non-binary transmasculine people also may be different. We did not systematically collect information from all participants on whether they had undergone gender-affirmative procedures as this may be perceived as intrusive. To broaden understanding of the experiences of transmasculine people, future research should also recruit participants who are not receiving services from community agencies, who reside in rural areas, who are from diverse age groups (including older persons) and income brackets, and who identify as gender non-binary, and should consider recruiting participants from online transmasculine communities. Finally, we did not directly ask about potentially sensitive characteristics including caste, religion or sexual orientation, but to understand the intersectional stigma faced by transmasculine people.

Conclusion

Gender norms, gender policing, rejection and discrimination in family and social spaces pose major challenges for transmasculine people in core aspects of affirming their gender and maintaining mental health. Despite the odds, transmasculine people often manage to navigate these challenges, largely by relying on informal resources (e.g. friends, transmasculine communities). Multi-level gender-affirming and stigma reduction interventions at social and structural levels (e.g. raising public awareness of gender diversity, enforcing anti-discrimination laws), the institutional level (anti-discrimination initiatives in educational and workplace settings), the family level (e.g. family education/counselling), and the individual level (e.g. self-acceptance counselling, self-advocacy skills, linking to transmasculine community networks) are needed to reduce pervasive stigma and discrimination faced by transmasculine people in India and to promote their inclusion and well-being.

Acknowledgements

Venkatesan Chakrapani was supported in part by the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Senior Fellowship (IA/CPHS/16/1/502667). Ayden Scheim was supported in part by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship. Peter A Newman was supported, in part, by a Partnership Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (MFARR-Asia, 895-2019-1020).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest statement

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

References

- Aburn G, Gott M, Hoare K. What is Resilience? An Integrative Review of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2016;72(5):980–1000. doi: 10.1111/jan12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani T, Nguyen T, Ryan A, Dwairy A, McCaffrey J, Yunus R, Forgione J, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Myocardial Infarction in the Transgender Population. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2019;12(4):e005597. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes119.005597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerji H. Patriarchy in the Era of Neoliberalism: The Case of India. Social Scientist. 2016;44(3/4):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Andrew, Checkel Jeffrey T. Process Tracing from Metaphor to Analytic Tool. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Blair E. A Reflexive Exploration of Two Qualitative Data Coding Techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences. 2015;6(1):14–29. doi: 10.2458/v6i1.18772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling J, Blekfeld-Sztraky D, Simmons M, Dodge B, Sundarraman V, Lakshmi B, Dharuman SD, Herbenick D. Definitions of Sex and Intimacy among Gender and Sexual Minoritised Groups in Urban India. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2020;22(5):520–534. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1614670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling J, Dodge B, Banik S, Bartelt E, Mengle S, Guerra-Reyes L, Hensel D, Herbenick D, Anand V. Social Support Relationships for Sexual Minority Women in Mumbai, India: A Photo Elicitation Interview Study. Culture Health &Sexuality. 2018;20(2):183–200. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1337928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, Velez BL, Mennicke A, Tebbe E. Voices from Beyond: A Thematic Content Analysis of Transgender Employees’ Workplace Experiences. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1(2):159–169. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bry LJ, Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Burns MN. Resilience to Discrimination and Rejection among Young Sexual Minority Males and Transgender Females: A Qualitative Study on Coping with Minority Stress. Journal of Homosexuality. 2018;65(11):1435–1456. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1375367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V. The Case of Tamil Nadu Transgender Welfare Board: Insights for Developing Practical Models of Social Protection Programmes for Transgender People in India. New Delhi: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), India; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V, Dhall P. Family Acceptance among Self-identified Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) and Transgender People in India. Mumbai: Family Planning Association of India; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani Venkatesan, Newman Peter A, Noronha Ernest. In: Transgender Sex Work & Society. Nuttbrock Larry A., editor. New York: Harrington Park Press; 2018. Hijras/Transgender Women and Sex Work in India: From Marginalization to Social Protection; pp. 214–235. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani Venkatesan, Newman Peter A, Shunmugam Murali. In: LGBTQ Mental Health: International Perspectives and Experiences. Nakamura Nadine, Logie Carmen H., editors. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2020. Stigma Toward and Mental Health of Hijras/Trans Women and Self-Identified Men who have Sex with Men in India; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz Kathy. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin Juliet M, Strauss Anselm Leonard. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Custodi Andrea. In: Gender and Narrative in the Mahabharata. Brodbeck Simon, Black Brian., editors. London: Routledge; 2007. ‘Show You Are a Man!’ Transsexuality and Gender Bending in the Characters of Arjuna/Brhannada and Amba/Sikhandin(i) pp. 208–229. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin Norman K, Lincoln Yvonna S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Downing JM, Przedworski JM. Health of Transgender Adults in the U.S., 2014-2016. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018;55(3):336–344. doi: 10.1016/Jamepre.2018.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent Resilience: A Framework for Understanding Healthy Development in the Face of Risk. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurevpublhealth26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtung Johan. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research. 1969;6(3):167–191. doi: 10.1177/002234336900600301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganju D, Saggurti N. Stigma, Violence and HIV Vulnerability among Transgender Persons in Sex Work in Maharashtra, India. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2017;19(8):903–917. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1271141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, Pass LE, Keuroghlian AS, Greenfield TK, Reisner SL. Alcohol Research with Transgender Populations: A Systematic Review and Recommendations to Strengthen Future Studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018;186:138–146. doi: 10.1016/Jdrugalcdep.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg Yudit Kornberg. Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara (Calif.): ABC-CLIO; 2008. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hebbar YR, Singh B. Psychiatric Morbidity in a Selective Sample of Transgenders in Imphal, Manipur: A Descriptive Study. Annals of Indian Psychiatry. 2017;1(2):114–117. doi: 10.4103/aip.aip_24_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A Conceptual Framework for Clinical Work with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients: An Adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43(5):460–467. doi: 10.1037/a0029597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D, Rhoten K. Epistemic Injustice and Judicial Discourse on Transgender Rights in India: Uncovering Temporal Pluralism. Journal of Human Values. 2020;26(1):30–49. doi: 10.1177/0971685819890186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jhang J. Scaffolding in Family Relationships: A Grounded Theory of Coming Out to Family. Family Relations. 2018;67(1):161–175. doi: 10.1111/fare.12302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner GE. In: Handbook of Qualitative Organizational Research, Innovative Pathways and Methods. Elsbach Kimberly D, Kramer Roderick M., editors. London: Routledge; 2015. Tabula Geminus - A “Both/And” Approach to Coding and Theorizing; pp. 350–361. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J. The Logic of Process Tracing Tests in the Social Sciences. Sociological Methods & Research. 2012;41(4):570–597. doi: 10.1177/0049124112437709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell Joseph Alex. A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meier CSL, Fitzgerald KM, Pardo ST, Babcock J. The Effects of Hormonal Gender Affirmation Treatment on Mental Health in Female-to-Male Transsexuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2011;15(3):281–299. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2011.581195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingle. In&Out The Indian LGBT Workplace Climate Survey 2016. 2016. https://vartagensex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/1559396942000-mingle-lgbt-wrkplc-climt-srvy-2016.pdf .

- Parker CM, Hirsch JS, Philbin MM, Parker RG. The Urgent Need for Research and Interventions to Address Family-Based Stigma and Discrimination against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2018;63(4):383–393. doi: 10.1016/Jjadohealth2018.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton Michael Quinn. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Pardo ST, Gamarel KE, White Hughto JM, Pardee DJ, Keo-Meier CL. Substance Use to Cope with Stigma in Healthcare among U.S. Female-to-Male Trans masculine Adults. LGBT Health. 2015;2(4):324–332. doi: 10.1089/lgbt2015.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, Cabral M, Mothopeng T, Dunham E, Holland CE, Max R, Baral SD. Global Health Burden and Needs of Transgender Populations: A Review. The Lancet. 2016;388(10042):412–436. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00684-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. In: Analysing qualitative data. Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. London: Routledge; 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rood BA, Maroney MR, Puckett JA, Berman AK, Reisner SL, Pantalone DW. Identity Concealment in Transgender Adults: A Qualitative Assessment of Minority Stress and Gender Affirmation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2017;87(6):704–713. doi: 10.1037/ort0000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Pollitt AM, Li G, Grossman AH. Chosen Name Use is Linked to reduced Depressive Symptoms, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicidal Behavior among Transgender Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2018;63(4):503–505. doi: 10.1016/Jjadohealth2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheim AI, Bauer GR, Shokoohi M. Heavy Episodic Drinking among Transgender Persons: Disparities and Predictors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;167:156–162. doi: 10.1016/Jdrugalcdep.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheim AI, Perez-Brumer AG, Bauer GR. Gender-concordant Identity Documents and Mental Health among Transgender Adults in the USA: A Cross-sectional Study. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(4):e196–e203. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheim A, Kacholia V, Logie CH, Chakrapani V, Ranade K, Gupta S. Health of Transgender Men in Low-income and Middle-income Countries: A Scoping Review. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(11):e003471. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelius J. Gender Affirmation: A Framework for Conceptualizing Risk Behavior among Transgender Women of Color. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11–12):675–689. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0216-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah Chayanika, Merchant Raj, Mahajan Shalini, Nevatia Smriti. No Outlaws in the Gender Galaxy. New Delhi: Zubann; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tamagawa M. Coming Out of the Closet in Japan: An Exploratory Sociological Study. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2018;14(5):488–518. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2017.1338172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa RJ, Habarth J, Peta J, Balsam K, Bockting W. Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2(1):65–77. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomori C, Srikrishnan AK, Ridgeway K, Solomon SS, Mehta SH, Solomon S, Celenta DD. Perspectives on Sexual Identity Formation, Identity Practices, and Identity Transitions among Men who have Sex with Men in India. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2018;47(1):235–244. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0775-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Law and Justice. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act. 2019;2019(40) http://socialjustice.nicin/writereaddata/UploadFile/TG%20bill%20gazette.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Trotter RT. Qualitative Research Sample Design and Sample Size: Resolving and Unresolved Issues and Inferential Imperatives. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55(5):398–400. doi: 10.1016/Jypmed2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alain Daniélou., translator. Vatsyayana. The Complete Kama Sutra: The First Unabridged Modern Translation of the Classic Indian Text by Vatsyayana: Including the Jayamangala Commentary from the Sanskrit by Yashodhara and Extracts from the Hindi Commentary by Devadatta Shastra. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender Stigma and Health: A critical Review of Stigma Determinants, Mechanisms, and Interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 2015;147:222–231. doi: 10.1016/Jsocscimed2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]