Abstract

Pediatric clinical research in low-resourced countries involves individuals defined as “vulnerable” in research ethics guidance. Insights from research participants can strengthen the design and oversight of studies. We share family members’ perspectives and experiences of an observational clinical study conducted in one Kenyan hospital as part of an integrated empirical ethics study. Employing qualitative methods, we explored how research encounters featured in family members’ care-seeking journeys. Our data reveals that children’s vulnerability is intricately interwoven with that of their families, and that research processes and procedures can inadvertently add to hidden burdens for families. In research, the potential for layered and intersecting situational and structural vulnerability should be considered, and participants’ agency in constrained research contexts actively recognized and protected.

Keywords: vulnerability, agency, integrated empirical ethics, childhood acute illness, low- and middle-income countries

Background

There is a recognized global inequity in the distribution of health research funds against need, with high-income countries accessing a disproportionately high level of research funding compared to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Cash-Gibson et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2014). This inequity has implications for building an understanding of health issues faced by populations in low-income settings, and for designing contextually appropriate responses to improve health and well-being. There are therefore regular calls for an increase in high quality, ethical health research in LMICs (Cash-Gibson et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2014). Within LMICs, disease burdens are disproportionately shouldered by the poorest communities, families, and individuals. Research involving these especially vulnerable groups is needed to address their needs.

In child health, given the ongoing problems of morbidity, mortality, and delayed neurodevelopment among young children living in extreme poverty, there is a clear need for clinical research to benefit these populations. Although international (and increasingly national) research ethics guidelines recognize children as a vulnerable population, they do not clearly guide researchers in how to respond to the range of vulnerabilities faced by seriously ill children living in highly precarious households, with only limited access to formal education and quality and affordable health care.

There is growing recognition that refined analyses of vulnerability are needed to understand, avoid, and minimize vulnerabilities in different research situations (Hurst, 2008; Luna, 2009; Rogers et al., 2012). Luna has argued, for example, that a particular person or subgroup (e.g., pregnant women or children) should not be seen or labeled as vulnerable in a fixed sense; rather they are rendered vulnerable by their specific situation. She has emphasized that vulnerability is relational (based on and shaped by interactions with others), and that different layers of vulnerability can interplay and overlap in different contexts to influence particular experiences and outcomes (Luna, 2009). Similarly, Lange et al. (2013) distinguish between vulnerability that is inherent—intrinsic to the human condition, arising from “our corporeality, our neediness, our dependence on others, and our affective and social natures”—and vulnerability that is more context-specific and situational, caused or exacerbated by the temporary or enduring conditions in which people find themselves.

In addition to recognizing, avoiding, and minimizing the potential to increase vulnerability in the course of research, ethical practice in research should ideally seek to understand, protect, and build upon people’s autonomy and agency. People’s “agency,” or their ability to make choices and to act, has often been seen as in contrast to their vulnerability. However, recent research has shown how expressions of agency can arise through experiences of vulnerability and vice versa, so that individuals can experience manifestations of both simultaneously (Binik et al., 2019). The importance of recognizing agency as situational and relational—in a similar way to vulnerability—is also increasingly recognized in the literature (Campbell & Mannell, 2016), as is the need to understand agency as constrained by prevailing social, economic, and cultural situations. In constrained contexts especially, Campbell & Mannell (2016) note the importance not only of recognizing the more visible and overt forms of agency, but also more discrete and less identifiable actions in order to understand, protect, and build upon people’s agency.

While some research ethics scholars have pointed to the importance of context in developing practical research ethics guidance (Luna, 2009; Rogers et al., 2012), there has been limited empirical research ethics work to understand vulnerability and agency in different contexts and how multiple sources of vulnerability manifest in research encounters. Learning from the voices and experiences of research participants themselves, and their family members, has the potential to strengthen our understanding of vulnerability, agency, and ethical practice in research.

Research that has been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa has highlighted that many family members of participants describe studies as an opportunity to access much-needed health care and advice (Kamuya et al., 2014; Molyneux et al., 2012). However, important study-related information is often not understood or easily recalled, raising concerns about levels of autonomy in decision making and validity of consent in contexts of vulnerability. Studies have also shown that even in contexts of significant constraint, individuals make active choices, thus exercising their agency in relation to research (Kamuya et al., 2015; Masiye et al., 2008). For instance, Kamuya et al. (2015) observed that some family members involved in a household-based longitudinal epidemiological study were able to avoid unpopular nasal swabs while remaining in the study in order to continue accessing study-related perceived benefits through “silently refusing” i.e., repeatedly avoiding appointments while opting against withdrawing from the study. In Malawi, an exploratory qualitative study found that people refused participation in a number of clinical studies when they became suspicious of the overall purpose and perceived the proposed procedures (such as blood draws) as harmful (Mfutso-Bengo et al., 2008). This spectrum of ways in which participant family members exercise agency from subtle to more dramatic illustrations, within the contexts of research encounters, has also been documented elsewhere (Kamuya et al., 2015; Kingori, 2015; Masiye et al., 2008; Mfutso-Bengo et al., 2008).

Studies in sub-Saharan Africa suggest that important inter-related influences on participants’ perceptions and experiences of research include: the study design and associated benefits; the institutional, socio-cultural, and geographical context in which the study is being conducted; how, when, and where consent processes are administered; and evolving interactions and relationships between study team members and research participants (Participants in the Community & Consent Workshop, 2013). Although these factors will likely shape, and be shaped by, potential participants’ levels and types of vulnerability and agency at the point of recruitment and over the course of their involvement in a study, we are not aware of any research that has specifically explored this. This is an important gap; as scholars in research ethics have emphasized, it is critical that research ethics take into consideration context-specific experiences of vulnerability when designing ethical studies and informing targeted, evidence-based interventions to those who may most need them (Lange et al., 2013; Luna, 2009; Mackenzie et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2012).

In this paper, we present family members’ experiences of a clinical observational cohort study which was part of an international empirical ethics study entitled “Resilience, Empowerment and Advocacy in Women’s and Children’s Health Research” (REACH). REACH aims to understand the potential benefits and challenges of engaging vulnerable populations in research. Elsewhere, we have described children’s complex treatment-seeking journeys into the hospital, through admission and postdischarge (Zakayo et al., 2020). We demonstrated how children’s pathways through care reflected family members’ navigation of diverse challenges related to intersecting vulnerabilities at individual, household, and facility levels. Although we also highlighted caregivers’ agency, as demonstrated in their decision making and actions, we argued that this agency was often significantly constrained by their children and families’ situation, as well as by broader structural drivers such as high levels of poverty in the area and low access to quality, affordable essential services (Zakayo et al., 2020). Here we focus on the research encounter itself—consent processes and decision making, as well as family members’ experiences of the study. We explore how research interactions featured in family members’ treatment-seeking journeys and how research-related experiences interplayed with children and their families’ vulnerability and agency. Our findings highlight the ethical challenges and issues that arise even during a carefully designed observational study at a well-resourced facility.

Study Setting and Methods

Study Setting

The empirical ethics study is part of a wider multidisciplinary collaboration aimed at developing an evidence-based, context-sensitive account of vulnerabilities and abilities of women, children, and families across diverse health research settings. The overall aim of the REACH collaboration is to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of vulnerability in research ethics, and improved practical ethical support and guidance for responsible research. The work includes empirical ethics case studies in Kenya, South Africa, and Thailand.

In Kenya, the REACH study was conducted in one of the 47 semi-autonomous Coastal counties, Kilifi. Kilifi County is one of Kenya’s poorest counties, with 68% of the population living below the poverty line. Most of the population depend on small-scale farming, and high levels of gender inequity are documented (Molyneux et al., 2005/2007; Scott et al., 2012). Kilifi County Hospital, where children were recruited into the study, has a long term and robust collaboration with the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP). KWTRP is a multidisciplinary, internationally recognized health research programme in Kenya with its headquarters in Kilifi. A collaborative working arrangement with the County Hospital management has made possible long-term strategic support in health facilities, including supporting all children admitted to the hospital regardless of participation in studies. Clinical research is integrated into health care delivery. KWTRP runs a well-established community engagement programme, including regular consultations with a network of ~220 community members elected by residents in the areas the County Hospital serves. Extensive community engagement activities include community inputs into institutional research policy.

The CHAIN Network Cohort Study

The REACH study conducted embedded qualitative work within the Childhood Acute Illness Nutrition (CHAIN) Network cohort study. CHAIN (www.chainnetwork.org) is a multidisciplinary research network aiming to understand the mechanisms contributing to young child mortality in hospital and after discharge in LMICs in order to identify interventions to improve survival (Childhood Acute & Nutrition, 2019). The network conducted a prospective cohort study at nine hospital sites in Africa and South Asia, recruiting more than 3,000 acutely ill children at admission to hospital. Children were enrolled across three strata by nutritional status: severely wasted or kwashiorkor (edematous malnutrition) (SWK); moderately wasted (MW); and not wasted (NW). Enrolled children faced a variety of social risks in terms of social disruption, household locations and types, and levels of maternal education. Audit and training were provided to sites to ensure treatment and referral for outpatient nutritional and other care after discharge was according to current national and WHO guidelines. The primary outcome of the cohort study was mortality. Children were followed post discharge for 6 months, with scheduled visits at days 45, 90, and 180, or at unscheduled visits when a child was unwell. Transport fares and out-of-pocket costs were reimbursed for scheduled follow-up visits at set institutional rates. At each of the follow-up visits, a questionnaire was administered to ascertain health, anthropometry, and a rectal swab and blood samples were repeated.

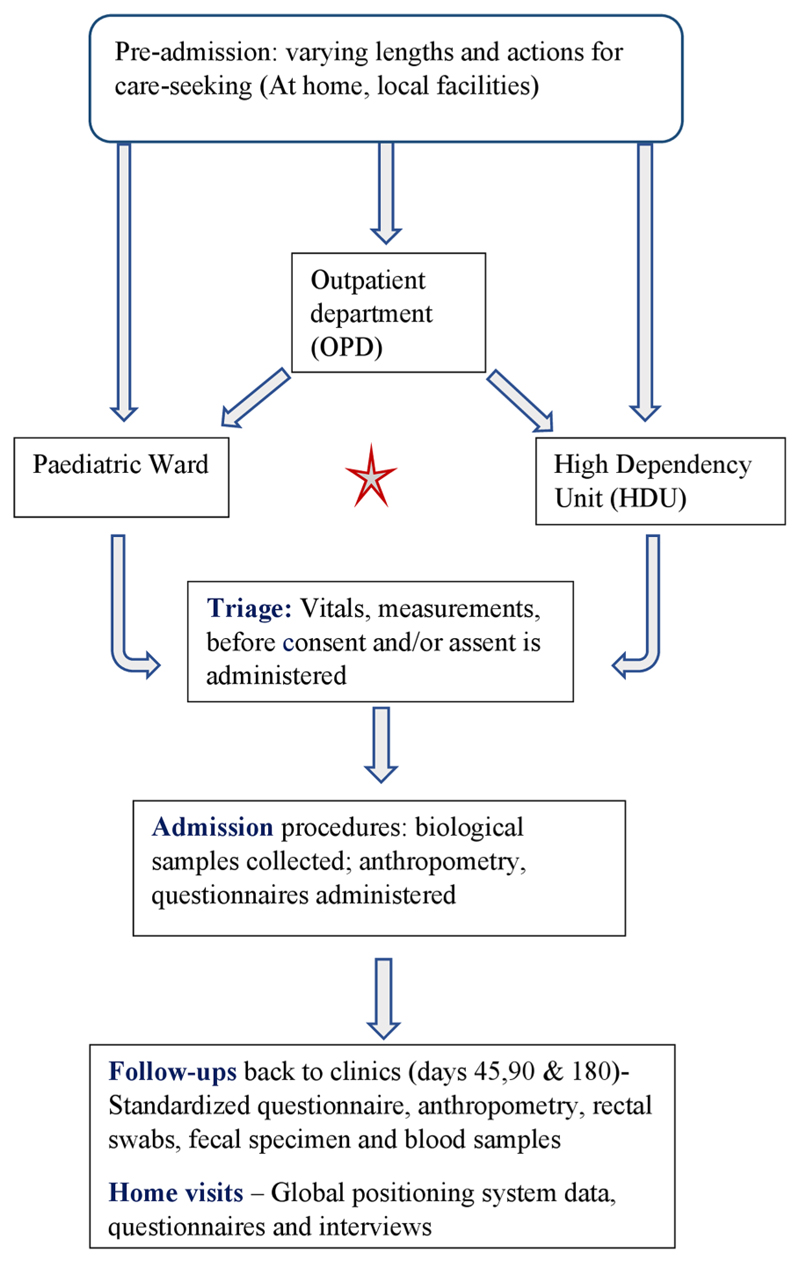

For the CHAIN cohort study, processes including consent were tailored to local contexts. In Kilifi, as illustrated in Figure 1, consent processes were designed to take place on admission, before any routine admission blood samples or treatment, in order to minimize the number of samples taken and maximize the study learning (the “social value” of the research). Patients were first triaged to identify those needing immediate life-saving treatment. Initially, all other eligible children were consented in full upon admission, but later an assent process was introduced for patients identified as seriously ill, but not needing immediate life-saving support. The assent process drew on previous experience (Molyneux et al., 2013) and involved a rapid information and permission process on admission, followed by a full consent process once the child had stabilized. All children, whether in the observational cohort or not, were admitted either in the main pediatric ward or high dependency unit, based on clinical need. Where indicated, children were referred to locally available government-provided specialist services. Referral practices were based on institutional benefit-sharing guidelines, developed through a careful research and consultation process, including community inputs (Njue et al., 2014; Participants in the Community & Consent Workshop, 2013). Table 1 summarizes the key features of the linked CHAIN study and information emphasized during the consenting process.

Figure 1. Illustration of research processes and interaction with standard care procedures.

Table 1. Features of the CHAIN Network Cohort Study.

| Who is conducting the research? | KEMRI/Ministry of Health/University of Oxford/University of Washington | |

| Study design | Stratified cohort study | |

| Study objectives | The CHAIN cohort study aims to characterize the biomedical and social risk factors for mortality in acutely ill children in hospitals and after discharge to identify targeted interventions to reduce mortality (Childhood Acute & Nutrition, 2019) | |

| Key processes and procedures |

|

Additional contextual information

|

| Risks |

|

|

| Benefits |

|

|

| Societal benefit to improve care for children |

|

|

| What happens to the samples |

|

|

| Sponsor | University of Oxford | |

| Funder | The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation |

Note. CHAIN = Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition.

Methods

As part of the integrated REACH empirical ethics study, we purposively selected 20 children from the primary CHAIN cohort, selected based on diverse attributes including their nutritional status, household socio-economic status, geographical location and whether they had experienced any socially disruptive event in their life in the months leading to admission. We talked to selected children’s primary caregivers (n = 20), usually mothers, during the child’s hospitalization, providing initial information on our ethics work and seeking permission to visit their homes to interview them and other family members involved in the child’s care. We then visited willing caregivers in their homes soon after discharge to further explain our work, seek formal consent, and conduct the first round of interviews. In the initial home visits, we also invited and consented other family members to take part in in-depth interviews. At least two additional sets of interviews were organized in homes over the following 6–12 months, including a final visit after the child’s involvement in the observational cohort had ended. Across the interviews, we aimed to understand the entire treatment-seeking journey from the perspective of each child’s main carers and other family members, including the child’s (evolving) symptoms, any actions taken, decision-making processes, and hopes and fears along the way. Specifically related to how the research encounter featured in these actions and experiences, we asked about: how participants first heard about the study; what information they recalled and how they felt at the time; who was involved in decision making over the child’s participation; why they agreed to participate; and their interactions and experiences with research(ers) post recruitment and at the end of the study.

A total of 74 in-depth interviews were held with primary caregivers and other family members (mostly mothers, fathers, mothers-in-law, aunts, uncles, and fathers-in-law) between April 2017 and July 2018. Home visits carried out by two social science researchers were organized to fit around domestic activities to avoid disruption of daily activities. The majority of households were made up of extended families, typically including grandmothers, in-laws, cousins and grandchildren, and relied on low-paying inconsistent sources of income. The 20 primary caregivers were all women aged between 19 and 38 years, and most had <8 years of primary schooling; four had some secondary or college education. Most of the primary caregivers of children with SWK were either unemployed or relied on their husbands or male family members for financial support. Further family details have been published elsewhere (Zakayo et al., 2020).

Data Management and Analysis

We have described in detail the analysis process for the treatment-seeking pathways, including vulnerabilities and identified sources of agency and social support, elsewhere (Zakayo et al., 2020). In brief, all formal interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and where necessary, translated into English, and summaries—enriched by observations and detailed team debriefs—prepared for each household visit. First, drawing on all available data, very detailed narratives were developed for each household. This offered a rich and in-depth picture of the household itself and the entire treatment-seeking trajectory and experience, including if and how research encounters featured. This approach ensured that the related research elements were not extracted and separated from their context and facilitated comparison across households. Second, a thematic approach was applied to the entire data set (specifically a framework analysis approach) where we condensed data from the transcripts through an iterative process of coding, building into categories and themes, with data managed using NVivo 10 software.

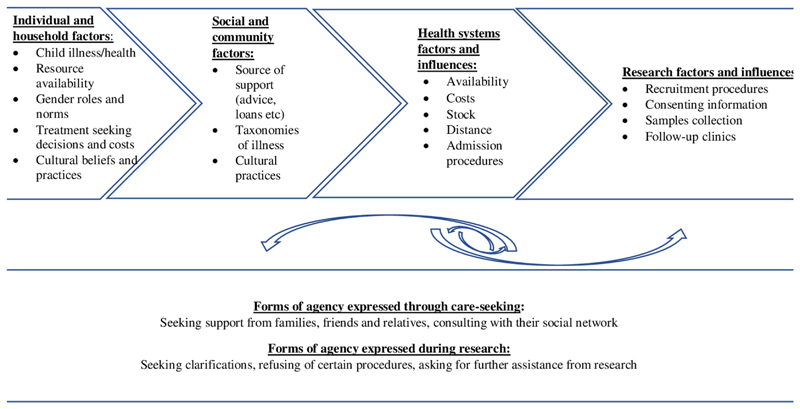

To combine data from the NVivo project and the household narratives for this paper, we developed charts focused on the research encounter. Table 2 illustrates the adopted charts, highlighting specific information on key elements of consent processes, broader research experience, and our interpretations drawing especially on household stories of how these elements appeared to indicate and interplay with family members’ vulnerability and agency (Figure 2).

Table 2. Example of Household Data Charting by their Research Encounters.

| Participant identification (PID) | Information given that was recalled | Feelings/emotions/concerns at time of information giving | Understanding of purpose and procedures | Who and why decided to join | Most appreciated | Mos concerning | Differences with non-participants | Indications of agency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HH002: Female, 24 months, 2.70 kg birth weight | That child has been enrolled and would be involved in some follow up clinical visits. When GM came to help during admission, she was informed that mother had agreed to participate, and blood would be drawn from the child. |

Got concerned when was told some test results become available after some time about 2 to 3 years. Didn't understand why that was the case. Didn't ask further explanations |

Was told child had been taken recruited into a research study, blood, urine, and stool samples will be collected, and child should be taken for follow-up after 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months to examine the child's progress. She was also told about given fare for the three visits but wasn't clear what would happen on the three visits. | Mother made the decision on her own. Agreed so that could find out what was ailing the child and wanted the child to get better. Was aware that thorough investigations would be conducted and in case, identify an illness for treatment. |

Friendly staff who regularly asked how the child was fairing. Attention given to the children was also appreciated. |

Blood draws since the child was already sick and weak. Not given results of the tests done from all the samples taken. | Mother did not notice any differences | Mother making decision to join without consulting GM whose main decision maker for family. Didn't ask for results, assumed that treatment was informed by the testing and was okay with that. |

| Hh011: Male, 15 months old, 2.06 kg at birth. | Reports being told that some examinations would be conducted, and those in research will have their bills paid in case they couldn't manage to. | Worried that they would have to incur extra costs as part of research participation. | Doesn't seem to understand what the research is and believes to be some chama/organization where children receive help with treatment. | Mother consented for her child to be involved in CHAIN, not clear why but perhaps to help out with the bills? | Was happy with fare and out-of-pocket reimbursements. | Worried about the too many blood draws. | Believed that all in the ward were part of research so didn't observe any differences. | With assumption that she would have to pay some extra money to participate, she wished she had other relatives close by-just in case she would need to pay |

Figure 2. Interaction of broader participants’ circumstances with research encounter.

Ethical Approval

REACH provided the opportunity to integrate ethics research within the CHAIN cohort study and proposal. After providing information about the study, written informed consent was sought from participants for all in-depth interviews, observations, and recordings, and checked in subsequent household visits. For appreciation and compensation for participants’ time and disruption during our home visits, each household was provided with a food package after each visit. This was based on past experience (Molyneux et al., 2012) and was in line with institutional guidelines. Where a child was observed to require medical attention during a research interaction, caregivers were referred to local facilities or CHAIN study clinicians. Any ethical dilemmas encountered by frontline staff were raised and discussed (Jepkosgei et al., 2019) in regularly organized debrief sessions.

Results

The Context in Which Caregivers Were Approached About Involvement in the Study

Children were brought to the hospital by their primary caregivers who were mostly their mothers (n = 17), in five cases accompanied also by the child’s father. For three children, the primary caregivers were an aunt or grandmother.

As described previously (Zakayo et al., 2020), many caregivers arrived at Kilifi County Hospital after having undergone a complex and lengthy period of treatment-seeking: children were often first monitored and treated at home, sometimes for extended periods, before being taken to traditional or religious healers, peripheral public health facilities, or local small private clinics. Most participants reported treatment-seeking journeys for “this illness”—often difficult to distinguish from previous illnesses—of at least 3 months (Table 3) before admission. Particularly lengthy treatment-seeking journeys were reported for children who were severely undernourished or had another chronic illness prior to admission to hospital. Many caregivers had experienced significant challenges and demonstrated considerable efforts to reach and receive care, often visiting multiple health care providers and incurring significant financial burdens, some of which were still to be repaid to family, friends, or service providers.

Table 3. Basic Carer and Treatment-Seeking Characteristics of Selected Children.

| PID | Malnutrition group | Main carer’s education | Main HH source of livelihood | Child brought to hospital by whom | Who made decision to participate | Expected admission? | Treatment seeking journey prior adm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hh1 | SWK | College | Husband—casual job | Mother and Father | Father | No | ≥12 months |

| Hh2 | Primary | Husband—watchmen | Aunt | Aunt | Unknown | ≥12 months | |

| Hh3 | None | Husband—palm tapper | Mother and Father | Father | No | ≤3 months | |

| Hh4 | None | Self—burn and sell charcoal | Grandmother | Grandmother | Was unsure | ≤3 months | |

| Hh7 | Secondary | Self—hired as salonist | Mother | Mother | No | ≤1 month | |

| Hh11 | Primary | Brother & father-in-law—masonry | Mother | Mother | No | ≤1 month | |

| Hh15 | Primary | Father and brother—masonry | Mother | Mother | No | 1 day | |

| Hh17 | Primary | Husband—small-scale fisherman | Mother and Father | Father | Unknown | ≤3 months | |

| Hh19 | None | Self—causal work | Mother | Mother | No | ≥9 months | |

| Hh20 | None | Self—causal jobs | Mother | Mother | No | ≤9 months | |

| Hh5 | Secondary | Self—runs food shop | Mother | Mother | No | 1 day | |

| Hh10 | MW | Primary | Husband—waiter Father-in-law—watchman | Mother | Mother | No | ≤3 months |

| Hh16 | Secondary | Brother—casual work | Mother | Mother | No | 1 day | |

| Hh6 | NW | Primary | Husband—banker Self—small businesses | Mother and Father | Father signed, both present and informed | No (didn't want) | ≥12 months |

| Hh8 | Primary | Husband—mason | Mother | Mother though felt need to consult | Unknown | 1 day | |

| Hh9 | College | Husband—casual | Mother | Mother | Was unsure | ≤9 months | |

| Hh12 | Primary | Self—casual work | Aunt & GM | Aunt after consulted GM | Was unsure | ≥12 months | |

| Hh13 | Primary | Self—fishmonger | Mother | Mother, consulted father | No | ≤1 month | |

| Hh14 | Primary | Father-in-law—formal employment | Father, Mother, GM | Father-mother focused on fitting child | Yes | ≤1 week | |

| Hh16 | Secondary | Brother—casual work | Mother | Mother | No | 1 day | |

| Hh18 | None | Husband—watchman | Mother | Mother | Unknown | ≥12 months |

Family members described a range of emotions and expectations on admission, from worries about their child’s condition and frustration with previous care-seeking experiences, through confusion and anger with the admission process, to more positive emotions of relief, hope, and trust that they had finally arrived at the facility that would treat their child. Several family members appreciated that their children had been triaged at the outpatient department and given immediate medication, but many reported a lack of familiarity with the hospital or admission process, and not being given clear instructions as outpatients on where to go next.

I had no hope, I had lost hope, and my brain couldn’t take in anything. I had lost hope, and I just went there knowing I was going to the hospital to have my child treated. I did not know whether my child would be admitted or would be given drugs and sent back home. I was confused. (Mother.Hh.3. SWK group)

Family members of 10 children did not expect or want their child to be admitted when they came to the hospital, and one mother was furious to hear that her child had to be admitted again: he had already been sick for a long time and had recently been admitted in a private hospital at great expense without being cured.

On admission to the wards, where further triage and consent processes were conducted, some mothers described feeling terrified about the child’s condition:

I worried that I was going to lose her to this condition…. My mind kept wandering; I visited the toilet thrice. I was restless. I was like a madwoman. But I got even more worried when they delayed attending to her. (Mother.Hh.5. NW group)

Others wished that they could contact other family members or felt exhausted and wanted the whole admission process to be over.

The Consent Process and Overall Understanding of CHAIN

The Consent Process and Decision Making

The approved consent process was to seek consent as soon as possible on admission, in order to maximize the social value of the research, while being sensitive to the often-stressful context of having a sick child admitted to the hospital. Where the father was not present, mothers and other relatives were to be given an opportunity to consult with the child’s father (including by phone), but the father’s signed consent was not required, given the potential for delays to be introduced.

Most primary carers described the consent process as part of regular admission processes (“because every place has its procedures”) or, more commonly, wanting staff “to get on with” the information giving and consent process and get it done. They described listening passively or sporadically to what was being said, and sometimes not listening at all because their attention was very much focused on their sick child. Many caregivers suggested that the choice for their child to be included in the research was not a difficult one to make. Where fathers were present, he was usually the person who was given information and made a choice. Only a few mothers consulted absent fathers by phone, to seek his view. As one mother explained:

I asked for only five minutes, and I moved away and called the child’s father because even if I had brought the child alone, I had to consult his father. So, I called him, and he said he was okay with allowing blood draws from the child. So, even though I had agreed, I had to ask his father as well. (Mother.Hh.13. NW group)

Caregivers described agreeing simply out of exhaustion with the lengthy and challenging journey they had gone through to get to the hospital, and in order for their child to get the needed diagnostic tests and treatment.

It’s because I was tired and there is no hospital I had not been to, I had visited several hospitals, wasn’t I from another hospital when I came there? So, I had to accept so that I may know what the problem is… (Mother.Hh.6. SWK group)

Yeah, I wanted to know what kind of disease was troubling her, maybe like for now that we don’t have money, I thought its better I put her in the research, that would help me. (Mother.Hh.16. MW group)

In several cases, caregivers described being grateful that the research institution would go “the extra mile” with careful tests and checks, as well as follow-ups, free of charge. One of the mothers who did not want her child to be admitted, described being so angry and concerned about needing admission that she did not listen to the information:

When they came to explain [the study] to me I was really angry that the child had to be admitted… I later told him [the consenter]: “By the way, you were talking to yourself, I don’t know what you were talking about.” I signed that thing, but I didn’t know what I was signing… (Mother.Hh.6. NW group)

A number of caregivers mentioned that they were keen for their child to be included in the project simply because of who was conducting it, having heard about the research institution’s reputation from relatives, friends, or neighbors. For instance, one mother mentioned that one of her neighbors had specifically advised her to go to and seek care from the research institution KEMRI because it is known to treat children with similar conditions. Other caregivers decided to include their child because of their previous positive encounters with the research center. For example, one mother explained:

What made me accept is that even my eldest child was recruited there. She was fitting also, and I took her to KEMRI [the research institute] where she was attended to and then given some follow-up clinic dates [just as happened for this child] … (Mother.Hh.18. NW group)

Almost all caregivers understood that they were given a choice about their child’s involvement in research. However, when asked what would have happened if they had refused their child’s participation, caregivers underscored their concern to secure quality treatment, and expressed difficulties believing or understanding the information they were given on voluntariness:

They said that even if you refused, still you would get the services, so I do not know… I could have received the services because they had told me, joining is voluntary, and even when you refuse still, the child will be treated. (Mother.Hh.13. NW group)

They explained that if someone refuses, he/she will be left alone [the decision will be accepted]. But I am not sure where those families will expect to get treatment for their child… (Mother.Hh.14. NW group)

Two mothers in our study agreed to enroll their child, in part, to contribute toward improving the care of children with similar conditions in the future:

Since I didn’t understand my child illness, I thought it’s good for research to be done so that a drug is found to treat another child with similar illness instead of going around looking for treatment. (Mother.Hh.9. NW group)

Concerns During the Consent Process and Information Giving

Several caregivers mentioned being anxious about the consent process itself before it began, including whether they would be able to comprehend the information they were given and answer any questions asked. For some caregivers, the consent process itself heightened their worries. Others reported feeling overwhelmed by the number of people who seemed to be involved in the admission process or with the amount of information given and questions. As one aunt mentioned:

I was approached by like four doctors. Everyone came, asked me questions, wrote somewhere and left. Another comes and asks me the same questions which her/his colleague has asked me, writes and then goes. And then again you are called by someone else. Initially, I was annoyed until I got used to it because you have gone there for the child to get assistance. (Aunt.Hh.12. NW group)

One mother felt strongly that having consent processes before admission was inappropriate and that the timing suggested researchers were more concerned about the research than the needs of the patient:

The research staff especially need to rectify issues mostly on the reception side. They should receive the baby first, treat the child first, then questions [consent] should come later……. Now when the person you are registering happens to die, will you continue to write, or it will be final? (Mother.Hh.5. NW group)

There were a few who described being apprehensive or fearful about interacting with the research staff, having heard rumors about the institute in their local communities and that adverse outcomes would befall anyone who engaged in any of the research institute’s projects.

After information was given, the most common concern was the potential impact of proposed blood draws on children who were already sick (discussed in detail below). Two participants mentioned worrying about whether there would be additional costs associated with study involvement and feeling confused when they were informed that their socio-economic data would be collected. Regarding the latter, one parent wondered whether these questions would support their hospital costs to be waived, and another worried that their assets would be confiscated if they were unable to pay bills. Several carers expressed concerns that results would only be available after about 2 years.

They explained to me but there is something which bothered me a bit because they said that some tests come out after I don’t know two years or one year that’s where I did not understand. (Mother.Hh.2.SWK group)

Nevertheless, the above concerns were generally outweighed by the hope of receiving (quality) treatment and recovery.

Understanding of CHAIN as a Research Activity

Overall, and drawing on all of the data we collected from family members, primary carers of only two of the 20 children appeared to understand or remember the community-wide, future-orientated goals of the research. The remaining caregivers gave detailed information on the procedures involved in the work but described the work or project as some advanced form of clinical care with extra sampling to guide a careful investigation and treatment plan for their children, with a follow-up period of routine check-ups (ranging from 3 to 8 months, or for an unknown period). The fact that they were seen more often or by more people during their research involvement may have potentially influenced how they understood the study.

The overall understanding of the research by most caregivers as some special clinical service was reflected in family members’ reactions at the end of the study and follow-up period: some felt that this meant that their children had fully recovered and did not require further medical care; others—particularly where children were still perceived by family members to be unwell—were disappointed that their children would no longer be monitored after the end of their study period.

Caregivers’ Experiences of Benefits, Burdens and the Blurred Boundaries of Research and Care

Benefits of Participation

Across all of our interviewees, there was an overall positive feeling about their children’s involvement in the study, with most appreciating the close care and attention their child received. Almost all caregivers talked about appreciating the thorough investigations and follow-up checks that continued after discharge, with many linking these extensive checks and enquiries to their children’s recovery. Several noted that the assessments and eventual diagnosis had eased their worries over time and reduced further financial burdens.

She was treated, given drugs and recovered.........they managed to diagnose the disease that had troubled me for long. I had spent a lot of money on it before, and yet once I went there, she recovered despite spending very little amount of money. (Grandmother.Hh.4.SWK group)

Like my child, he was tested, and I was given the results to know what the problem was, and I was very thankful because I’ve known what was disturbing him. Rather than taking him to a place where he is just given the drugs, and you don’t know what he is suffering from. (Mother.Hh.19.SWK group)

Participants expressed varied views when we asked them whether they had observed any differences to those who were not part of the CHAIN study. The majority reported seeing no significant differences stating that all children in their ward bays had been treated and cared for by the same health care workers. One mother reported that she thought everyone in their admission bay was a participant until she came to realize otherwise:

No, you know … we were talking with the other mothers, and they were telling me “aaah! So, this one has been recruited into a research study?” so I was asking myself, “who are these?” You know I didn’t know that we are not all in research. (Mother.Hh.6. NW group)

A few caregivers mentioned some subtle or more clear differences in terms of who attended to their children, the amount of attention given to them or the number of times their children were bled for sample collection. As two mothers explained:

We were the first people to be attended to [[M: The first ones]] yes, then our doctors were different, while the others were being attended to by the doctors who were stationed in that ward. Its only during the night when we were given drugs by the regular doctors. (Mother.Hh.7. SWK group)

I noticed a big difference because we were given additional attention………They would regularly check on the child every time they passed by. The others [non-participants] had to wait for the nurses from the other side to come……I saw that there was a difference because I would be listened to whenever I approached them [research staff] and whenever I had a problem, yes. (Mother.Hh.6. NW group)

Many participants also greatly valued the follow-up visits at the study clinic, with expenses covered, as an opportunity for their child’s progress to be checked, as well as an opportunity to visit a town and access small additional funds for essentials. Importantly, there was a general appreciation that clinical care and support continued during a prolonged health worker strike when very few people in the community had any access to public health care facilities.

Because at that time she had told me that I could not take him because the doctors were on strike, yes, but she had told me if he has anything just bring him… (Mother.Hh.6. NW group)

Burdens of Participation

Despite describing several overall benefits of participation, including the value of specific tests and procedures, caregivers raised some concerns. Some experienced general discomfort around blood sample collections with many describing the process as painful and the volumes as dangerous for sickly babies:

…. every time they draw blood from her it hurts, because sometimes they miss the vein and then they have to remove the needle and find the vein again, so you sense pain the way the child’s crying. (Mother.Hh.16. SWK group)

I was worried that with the amount of blood they would ‘drain the child yet she doesn’t have enough of it… (Mother.Hh.7. SWK group)

Some caretakers described being anxious or irritated about not receiving results from the collected samples.

Yes, and they have never told me that, “we have done our research/investigations, and we found the blood having this and this.” The researchers have never told me, and whenever I asked, they used to say to me “you will receive your results”, or “they are in the file.” (Mother.Hh.7. SWK group)

There were also some complaints or concerns around compensation for bus fares that were provided according to institutional guidelines. Several caretakers mentioned the significant challenges they faced in having to seek money every time they had to go for a follow-up clinical visit, for example having to borrow money from relatives and friends or having to try to sell for example charcoal or farm products to access the funds. It was also noted in a number of households that the amount of money that caretakers were given once they had completed their clinical visit, did not cover the actual costs incurred.

In contrast, one father explained that he never understood why money was given whenever their child’s blood was collected (i.e., for what was perceived as a routine follow-up clinical visit).

I tried to inquire from them what the money they were giving me was for. I am the one with a sick person, yet you treat and then pay me back? (Father.Hh.2. SWK group)

Although not raised directly by family members, two more hidden burdens we observed in our field interactions were the length of the postdischarge household visits and the clinic follow-up visits. Timing of postdischarge household visits was difficult for CHAIN team members to plan, depending as they did on when vehicles could leave the research center, and how many other households had to be visited. Household members were, therefore, often asked to wait for a visit on a particular day. They sometimes landed up waiting for many hours, disrupting their daily income–earning activities and household chores. There was no compensation to households for these visits, based on institutional guidelines stating that no reimbursement is needed where appointments can be planned with families around their activities, and take less than 2–3 hours in total.

Regarding the length and timing of clinic visits, these often involved very long journeys, including over mealtimes. Costs of meals were not included in the set compensation rates for clinic visits at first, leading to hunger or additional unintended costs for family members.

Exercising Agency to Negotiate Benefits and Burdens in Research and Care

Many participants remained keen to participate in the study given the perceived benefits, despite having some anxieties or concerns. Several reported actively speaking against or avoiding elements of the study they did not like in order to retain positive aspects.

For example, several mothers wanted to withdraw their child from painful bleeds but not from the rest of the CHAIN activities. They, therefore, tried, in one case successfully, to protect their children by requesting research staff to make fewer attempts to take a sample or to draw less volume. Noteworthy, here is that the samples taken during admission are part of standard clinical care, rather than for research. One mother reported declining a lumbar puncture (an investigation entirely for clinical management) because it was “painful and unnecessary.”

In some cases, caregivers were determined to remain in the research despite the carers of other children in the ward and community members trying to spread doubts and fears in their minds. One mother told us:

There were some people who were saying the research institution—KEMRI is not a good place… [that they are devil worshippers…]. But I decided to continue participation because I wanted my child to be healed. Others were saying they wouldn’t have joined if they had been asked, but for me, I joined the research study because I wanted my child to be well. (Mother.Hh.15. SWK group)

Another participant reported being warned against blood draws as they would cause harm to the child. She, however, told us that only those misinformed would make such claims.

She was saying that the drawing of blood can make the baby disabled. I do not know what, that I should not participate in that, so I just told them ‘it’s okay!’ Because others do not even understand, some have not read and realised what usually happens, or maybe they have not got someone to explain appropriately to them. (Mother.Hh.16. SWK group)

The longitudinal nature of the study through admission and into the postdischarge period through follow-ups provided an avenue to build trusting relationships between family members and research staff. Family members were sometimes able to access additional care and support from the study team.

I was told that it’s not easy for the others to give out their numbers, that is the main doctors. So, XXX [named a CHAIN staff member] gave me her number … she asked me to tell her in case he is affected by anything. Since my home was far, she told me “if you were nearby you could just bring her in case of anything, but since you are far just make a call then we can advise you. But do not rush in taking the child to a hospital.” (Mother.Hh.6. NW group)

During admission, for example, several families appreciated receiving essential items like free diapers for their children, which were required and would otherwise have cost KSh.50 ($0.50) each. In the real sense, diapers were provided to facilitate the collection of study related fecal samples. However, non-CHAIN mothers were required to buy them for hygiene. Postdischarge, another caregiver mentioned that she was able to persuade the research team to help expedite the waiting period for her child for a scheduled medical procedure. Others were able to receive a medical check-up for their own health issues, typically by being referred by research staff to appropriate care providers for treatment.

We noted that some caretakers faced challenges related to referrals. For example, one mother who had been advised that her child may have chronic heart disease had been referred to a private facility in a city more than 1 hour away for a scan. For several months she was unable to find the funds to cover the costs. Another mother was informed her child had suspected sickle cell disease, but she did not bring her child back for a confirmatory test because of the transport costs involved with the return visit, and out of an expressed concern about how such a diagnosis would be received and coped with in her household. One mother who was invited to see the CHAIN clinicians to discuss crippling vaginal pains she had been experiencing off and on for many months did not come. Although she was provided with the transport costs, her husband—who was reported to be violent—was apparently not supportive of the consultation and so she was unable to attend.

Discussion

Our study has generated detailed accounts of family experiences of a pediatric observational clinical study. Learning from the voices and experiences of research participants and family members offers potential to strengthen our understanding of vulnerability, agency, and ethical practice in health research in LMICs.

Throughout the findings we see that care-seeking pathways for most children were often lengthy and complex, and reflected family members’ actions and agency in their efforts to navigate the multiple layers of vulnerability they faced. We have described the vulnerabilities faced by families across care-seeking pathways in more detail elsewhere (Zakayo et al., 2020). But briefly, children’s biomedical conditions, and vulnerability to prolonged illness and (re) hospitalization, interacted with their families‘—and especially their mothers’—intrapersonal (biological or psychological), interpersonal (roles, relationships, and interactions), and environmental (socio-economic and cultural, and institutional) vulnerabilities. The fact that an acute illness occurs within a child’s health trajectory was conceived and built into the design of the CHAIN cohort study (Childhood Acute & Nutrition, 2019). Furthermore, in terms of intrapersonal vulnerabilities, many mothers described the emotional impact of their child’s illness and their treatment-seeking journeys. Worries, confusion, frustration, anger, hope, and relief were shaped by interactions and relationships with others in the home and community, by encounters with health providers, and by family members’ broader livelihoods situations. Although family livelihoods varied, many faced low, irregular sources of income, competing demands on those resources, complex family situations (such as physical separation, regular movement, or divorce) and gendered family and community relations. These multiple situational forms of vulnerability were shaped by the household trajectory, which was in turn affected by wider structural drivers in the community, including scarce income–earning opportunities, impoverished formal education, seasonal drought and food shortages, highly resource-constrained public-sector health services, and strong gender inequities. Thus, the child’s acute illness also occurred within a household situational trajectory, which was also influenced by the illness itself.

It is essential that these various and intersecting forms and layers of vulnerability, and the efforts and initiative that especially mothers undertake in their efforts to navigate these, are considered in designing, planning, and reviewing studies in under-resourced settings. The various forms and layers of vulnerability faced by children and their family members inevitably shaped their views and understanding of CHAIN. While many caregivers’ descriptions of CHAIN suggest a “therapeutic misconception,” where a particular activity is wrongly understood to being conducted primarily for the benefit of the individual child (Tindana et al., 2006), the word misconception is problematic (Molyneux et al., 2005), especially for a clinical observational study like CHAIN, where children are followed up closely over an extended period of time, and where there is treatment of problems identified and referral to alternative care where indicated. Perhaps more noteworthy were “research misconceptions” (the opposite of therapeutic misconceptions), where consent processes inadvertently introduced concerns about clinical investigations such as some blood sampling and lumber punctures (Marsh et al., 2011; Mbuthia et al., 2019; Molyneux et al., 2005; Participants in the Community & Consent Workshop, 2013). Again, calling these views “misconceptions” is problematic for a clinical observational study where any data on a child’s disease and progression can contribute to knowledge generated by the study. Another concern is that in several cases, consent processes also seemed to introduce a “false hope” among parents that they would have routine admission fees covered or be given free food, discussed more as follows.

Consent processes—including information giving, understanding of that information, and making a free decision—are widely considered an important mechanism to demonstrate respect to (potential) research participants, but widely recognized to be highly challenging to administer and evaluate in practice (Bull et al., 2012; Klima et al., 2014; Participants in the Community & Consent Workshop, 2013; Woodsong & Karim, 2005). For this clinical observation study, an important influence on understanding and recall were the emotional context that families were experiencing at the point of consent, in turn, related to the child’s illness, their broader treatment-seeking journeys and vulnerabilities, and their expectations and anxieties around being admitted and involved with KWTRP activities. Notable was that the consent process itself—including emphasizing voluntariness and the need to make a choice—added to the emotional admission context, sometimes adding to caregivers’ worries and frustrations and sometimes feeding into more positive emotions of relief, hope, and trust. Burdens of a consent process within this emotional context need greater attention in the literature and practice (Participants in the Community & Consent Workshop, 2013). For an observational clinical study where there is necessary and intentional blurring between research activities and clinical care, there is a risk that an emphasis on initial consent and understanding adds unnecessarily to vulnerabilities and burdens faced by family members, and crowds out other important ethical considerations.

Given challenges in many contexts with judging what level of understanding of research is appropriate, it has been suggested that an important check on respectful inclusion in studies is to explore participants’ or their caregivers’ overall feelings about the study and whether they have any regrets in participating (Klima et al., 2014; Lindegger & Richter, 2000; Woodsong & Karim, 2005). Many of the caregivers we interviewed were appreciative that their children were included in CHAIN, highlighting that they valued being talked to kindly in the wards, the clinical care they received, and regular clinic visits—with expenses covered.

To access perceived study-related benefits, we see mothers and other caregivers exercising overt agency in, for example, decisions to join the study, and more subtle forms of agency in for example their ignoring advice of others on the ward to withdraw. In some cases, caregivers were able to use their research interactions and relationships built with research staff to request for advice and support for their own health issues, and thereby gain support beyond that outlined in the CHAIN protocol (suggesting some hopes on admission and during the consent process were not in practice “false”). Nevertheless, and as reported previously (Zakayo et al., 2020), we noted that some actions by caregivers appeared to be both an act of constrained agency and a form of vulnerability. Caregivers were advocating for their children and exercising choice by, for example, refusing a lumbar puncture being requested for clinical diagnostic purposes, out of a mistaken understanding that it is “just” for research, has potential to feedback into health vulnerabilities through negatively impacting on the ability to access optimal clinical care.

Parents also shared important worries and concerns across their research encounter (such as blood volumes and sampling, the need for results, needing information on reasons for fares, and disruptions associated with undercompensated follow-ups). These burdens and concerns, some of which may not be immediately obvious to researchers or which may seem small, have important implications in terms of adding to layers of vulnerabilities faced by families, contributing to a cumulative effect. With heightened awareness through training and ethics support both research teams and institutions can learn to recognize and be more responsive to such hidden or cumulative burdens. One approach could be to add to benefits given to family members, including in relation to ancillary care. However, adding to these benefits for participants for a study like CHAIN would risk undermining already challenging consent processes by giving even greater weight to treatment benefits; potentially contributing to undue inducement to participate or “an empty choice” for parents (Kingori, 2015). Doing so might also risk introducing greater differences and relationship challenges between participants and non-participants in the same wards, and undermine the generalizability of the study findings, and therefore social value. An alternative approach in such a study would be to provide increased benefits to all admitted children and family members, many of whom will have similar vulnerabilities and needs as participants’ families (Benatar & Singer, 2000/2010; Molyneux et al., 2013; Njue et al., 2014). However, this increases the costs and reduces the feasibility of research, and also potentially reduces the generalizability of the findings to other settings. Furthermore, some children and family members would undergo the study risks or disadvantages (such as pain associated with sampling, or time taken for follow-up visits after recovery), on behalf of others, without perceived benefit. Finally, it would be difficult to know where researchers’ responsibilities for children and families would end, given the multiple forms and layers of vulnerability faced by so many, and the deep structural drivers of those vulnerabilities.

Best Practices

It is recognized that researchers have special ethical responsibilities when working with vulnerable populations. Although guidelines and governance procedures exist to protect vulnerable populations, definitions of vulnerability are not uniformly agreed upon, and interpretation and application of ethical guidance is far from straightforward.

Clinical research is critical to generate evidence-based interventions to improve childhood survival in low resource settings. Our findings highlight the importance in pediatric clinical research of recognizing that children’s vulnerability is inevitably interwoven with that of their family members and that families are likely to face multiple challenges related to layers of vulnerabilities. In planning and reviewing research, the potential for such layered situational and structural vulnerabilities must be taken into account, including the possibility that research processes and procedures will inadvertently add to hidden burdens for families. Furthermore, participants’ agency in constrained research settings should be actively recognized, responsively protected and promoted during the conduct and administration of research.

Research Agenda

The design and oversight of pediatric clinical research involving potentially vulnerable populations can be strengthened by the insights and experiences of research participants’ family members.

In this study, we conducted in-depth interviews with carers of young children and explored their perspectives of the entire treatment-seeking journeys for their children including how research featured in their experiences. Overall, we learnt that family members’ research-related experiences inevitably intersected with the challenges they faced in navigating diverse and changing vulnerabilities at the individual, household/community, and health facility levels. These challenges, together with some agency (which was constrained by prevailing social, economic, and cultural situations) shaped family members’ experience of their child’s illness, the treatment-seeking pathways they followed, their physical and emotional well-being at the time of consent, their decision making about participation in research, and their overall perceptions of research-related benefits and disadvantages.

Our data add to the limited empirical research ethics work to date that is aimed at understanding vulnerability and agency in different contexts and how multiple sources of vulnerability manifest in research encounters. Further similar research is needed from different research contexts to learn from the voices and experiences of research participants themselves, and their family members. Data from diverse contexts should contribute to better understanding of ground realities, in turn feeding into stronger policy and practice for research in low resource settings.

Educational Implications

It is essential that researchers planning and reviewing studies carefully consider the context within which research encounters will take place. For this hospital-based study, for example, many caregivers were arriving at the hospital requiring admission having undergone complex and lengthy treatment-seeking journeys. Consent processes amplified the emotional aspects of hospital admissions, and for some parents added to their emotional burdens at a difficult time. For an observational clinical study where there is necessary and intentional blurring between research activities and clinical care, there is a risk that an emphasis on initial consent and understanding adds unnecessarily to vulnerabilities and burdens faced by family members, and crowds out other important ethical considerations such as levels and types of benefits in the face of multiple layers of intersecting vulnerability.

With regards to international research collaborations, our data highlight the importance of tailoring and administering research processes in a way that is responsive to contextual realities and multilayered vulnerabilities and needs, while also recognizing and building individual’s agency in challenging contexts. Taking into account participant perspectives can strengthen and inform research guidelines and processes. In this way, researchers, ethics committees, and community members have the potential to benefit from integrated empirical ethics studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all study participants, the Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition Network, the study linked fieldworkers and data entry clerks (Julius Mumbo, Wilhemina Mwamuye, Raymond Mtepe, Hilda Mwalewa, Magdalene Salama & Elvina Mwango) and REACH team members based in Oxford (Jennifer Roest, Cai Heath & Michael Parker) for all of their support throughout the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation awarded to the CHAIN Network (grant: OPP1131320), in part by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (grant: 096527) and a Wellcome Trust & MRC Newton Fund Collaborative Award (grant: 200344/Z/15/Z). The results and interpretation presented here do not necessarily reflect the views of the study funders.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 096527, 200344/Z/15/Z, OPP1131320).

Biographies

Author Biographies

Scholastica M. Zakayo is a global health researcher with a background in Anthropology and was working as a research officer within the REACH study at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi Kenya. Her research interests revolve around Reproductive, Maternal and New-born Health, including the ethics of working with vulnerable groups.

Mary N. Kimani is a research assistant at the KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme. She is a social scientist interested in understanding individual and socio-cultural factors around illness, health and healthcare for women, children, and adolescents. She also has an interest in the ethics of researching with these groups, particularly in the African context.

Gladys Sanga is an assistant research officer in the Health Systems and Research Ethics Department at KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya. Her main research interests are in health research ethics; especially ethics around involving vulnerable groups in research in low- and middle-income countries.

Rita W. Njeru is a research officer within the REACH study at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi Kenya. Her wider research interest span health services and systems research, and research in public health ethics, especially around studies and interventions targeting vulnerable infants and children.

Anderson Charo is a field supervisor working at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme. Anderson is mainly involved in training and mentoring fieldworkers in qualitative methods of data collection and was passionately involved in the logistical planning of fieldwork in the REACH study. His current research interests center around empowering and engaging the community for effective research uptake and promoting ethical practices during consent processes.

James A. Berkley is a professor of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of Oxford. He currently serves as the codirector of the Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition Network (CHAIN). Dr. Berkley leads a research group working on serious infections and mortality in vulnerable neonates and children, antimicrobial treatment, immunity, and clinical trials.

Judd L. Walson is the vice-chair of the Department of Global Health and a professor of Global Health, Medicine (Infectious Disease), Pediatrics, and Epidemiology at the University of Washington. He currently serves as the codirector of the Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition Network (CHAIN). Dr. Walson is particularly interested in the effects of infection on childhood survival, immunologic function, and growth.

Maureen Kelley is a professor of Bioethics at the Ethox Centre and Wellcome Centre for Ethics & Humanities in the Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford. Her research focuses on ethics and maternal-child global health, and international research ethics.

Vicki Marsh is an associate professor in Public Health at the Centre for Global Health Research, Oxford University, UK and the KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP) in Kenya, with roles in research, teaching, mentorship and Science and Ethics Governance. Her research draws on empirical ethics approaches towards strengthening policy and practice in international health research, with a focus on issues of equity and accountability.

Sassy Molyneux is a professor in Global Health at the University of Oxford, and a long-term member of the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kenya. She is the social science lead for the Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition Network (CHAIN). Professor Molyneux’s particular interests include treatment-seeking, gender and intersectionality, health and research systems and equity and ethics.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note

The design, results, and interpretation presented here do not necessarily reflect the views of the study funders. The work was conducted in collaboration with the University of Oxford, Centre for Global Health, University of Washington and the Kenya medical Research Institute-Wellcome Trust Research Programme. Permission to publish this paper was obtained from the director, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI).

Authors’ Contributions

S.M.Z. contributed to the development of data collection tools, actual data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. She prepared the first draft of the manuscript and contributed to subsequent revisions. M.N.K. contributed to the development of data collection tools, actual data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and manuscript reviews and revisions. G.S. contributed to the development of the data collection tools, actual data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and manuscript reviews and revisions. R.W.N. contributed to the development of data collection tools, actual data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and manuscript reviews and revisions. A.C. contributed to the development of data collection tools, actual data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data and manuscript reviews and revisions. J.A.B. conceptualized the study and contributed to manuscript reviews and revisions. J.L.W. conceptualized the study and contributed to manuscript reviews and revisions. M.K. conceptualized the study, contributed to the development of data collection tools, and manuscript reviews and revisions. V.M. contributed to the study design, development of data collection tools, supervision of the data collection analysis, and manuscript reviews and revisions. S.M. contributed to the study design, development of data collection tools, supervision of the data collection, and analysis, and manuscript reviews and revisions.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer

The listed authors reviewed several drafts and provided important suggestions to the paper. All authors read, critically reviewed, and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

References

- Benatar SR, Singer PA. A new look at international research ethics. Bmj. 2000;321(7264):824–826. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benatar SR, Singer PA. Responsibilities in international research: A new look revisited. Institute of Medical Ethics; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binik AKM, Molyneux S, Marsh V, Cheah PY, Parker M. Vulnerability in research ethics: Setting a new agenda. 2019. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Bull S, Farsides B, Tekola Ayele F. Tailoring information provision and consent processes to research contexts: The value of rapid assessments. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2012;7(1):37–52. doi: 10.1525/jer.2012.7.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Mannell J. Conceptualising the agency of highly marginalised women: Intimate partner violence in extreme settings. Global public health. 2016;11(1–2):1–16. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1109694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash-Gibson L, Rojas-Gualdrón DF, Pericàs JM, Benach J. Inequalities in global health inequalities research: A 50-year bibliometric analysis (1966-2015) PLOS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childhood Acute, I., & Nutrition, N. Childhood acute illness and nutrition (CHAIN) network: A protocol for a multi-site prospective cohort study to identify modifiable risk factors for mortality among acutely ill children in Africa and Asia. BMJ open. 2019;9(5):e028454. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JA, Shim J-M, Ioannidis JP. Attention to local health burden and the global disparity of health research. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(4):e90147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst SA. Vulnerability in research and health care; describing the elephant in the room? Bioethics. 2008;22(4):191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepkosgei J, Nzinga J, McKnight J. Maintaining distance and staying immersed: Practical ethics in an underresourced new born unit. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2019;14(5):509–512. doi: 10.1177/1556264619835709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamuya DM, Marsh V, Njuguna P, Munywoki P, Parker M, Molyneux S. “When they see us, it’s like they have seen the benefits!”: Experiences of study benefits negotiations in community-based studies on the Kenyan Coast. BMC Medical Ethics. 2014;15(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-15-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamuya DM, Theobald SJ, Marsh V, Parker M, Geissler WP, Molyneux SC. “The one who chases you away does not tell you go”: Silent refusals and complex power relations in research consent processes in coastal Kenya. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0126671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingori P. The "empty choice": A sociological examination of choosing medical research participation in resourcelimited sub-Saharan Africa. Current Sociology. 2015;63(5):763–778. doi: 10.1177/0011392115590093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klima J, Fitzgerald-Butt SM, Kelleher KJ, Chisolm DJ, Comstock RD, Ferketich AK, McBride KL. Understanding of informed consent by parents of children enrolled in a genetic biobank. Genetics in Medicine. 2014;16(2):141–148. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange MM, Rogers W, Dodds S. Vulnerability in research ethics: A way forward. Bioethics. 2013;27(6):333–340. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindegger G, Richter L. HIV Vaccine trials: Critical issues in informed consent. South African Journal of Science. 2000;96(6):313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna F. Elucidating the concept of vulnerability: Layers not labels. IJFAB: International Journal ofFeminist Approaches to Bioethics. 2009;2(1):121–139. doi: 10.3138/ijfab.2.1.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie C, Rogers W, Dodds S. Vulnerability: New essays in ethics and feminist philosophy. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh VM, Kamuya DK, Parker MJ, Molyneux CS. Working with concepts: The role of community in international collaborative biomedical research. Public Health Ethics. 2011;4(1):26–39. doi: 10.1093/phe/phr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiye F, Kass N, Hyder A, Ndebele P, Mfutso-Bengo J. Why mothers choose to enrol their children in malaria clinical studies and the involvement of relatives in decision making: Evidence from Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal. 2008;20(2):50–56. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v20i2.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuthia D, Molyneux S, Njue M, Mwalukore S, Marsh V. Kenyan Health stakeholder views on individual consent, general notification and governance processes for the re-use of hospital inpatient data to support learning on healthcare systems. BMC Medical Ethics. 2019;20(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12910-018-0343-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mfutso-Bengo J, Masiye F, Molyneux M, Ndebele P, Chilungo A. Why do people refuse to take part in biomedical research studies? Evidence from a resource-poor area. Malawi Medical Journal. 2008;20(2):57–63. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v20i2.10958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux C, Hutchison B, Chuma J, Gilson L. The role of community-based organizations in household ability to pay for health care in Kilifi District, Kenya. Health Policy and Planning. 2007;22(6):381–392. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux C, Peshu N, Marsh K. Trust and informed consent: Insights from community members on the Kenyan coast. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(7):1463–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux S, Mulupi S, Mbaabu L, Marsh V. Benefits and payments for research participants: Experiences and views from a research centre on the Kenyan coast. BMC medical ethics. 2012;13(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux S, Njue M, Boga M, Akello L, Olupot-Olupot P, Engoru C, Kiguli S, Maitland K. “The words will pass with the blowing wind”: Staff and parent views of the deferred consent process, with prior assent, used in an emergency fluids trial in two African hospitals. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(2):e54894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njue M, Kombe F, Mwalukore S, Molyneux S, Marsh V. What are fair study benefits in international health research? Consulting community members in Kenya. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(12):e113112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Participants in the Community, E., & Consent Workshop, K. K. M. Consent and community engagement in diverse research contexts. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2013;8(4):1–18. doi: 10.1525/jer.2013.8.4.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers W, Mackenzie C, Dodds S. Why bioethics needs a concept of vulnerability. IJFAB: International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics. 2012;5(2):11–38. doi: 10.3138/ijfab.5.2.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JAG, Bauni E, Moisi JC, Ojal J, Gatakaa H, Nyundo C, Marsh K. Profile: The Kilifi health and demographic surveillance system (KHDSS) International journal of epidemiology. 2012;41(3):650–657. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindana PO, Kass N, Akweongo P. The informed consent process in a rural African setting: A case study of the Kassena-Nankana District of Northern Ghana. Irb. 2006;28(3):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodsong C, Karim QA. A model designed to enhance informed consent: Experiences from the HIV prevention trials network. American journal of public health. 2005;95(3):412–419. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]