Abstract

Background

The purpose was to synthesise evidence on the association between nature-based Early Childhood Education (ECE) and children’s physical activity (PA) and motor competence (MC).

Methods

A literature search of nine databases was concluded in August 2020. Studies were eligible if a) children were aged 2-7 years old and attending ECE, b) ECE settings integrated nature, and c) assessed physical outcomes. Two reviewers independently screened full-text articles and assessed study quality. Synthesis was conducted using effect direction (quantitative), thematic analysis (qualitative) and combined using a results-based convergent synthesis.

Results

1,370 full text articles were screened and 39 (31 quantitative; 8 qualitative) studies were eligible. 20 quantitative studies assessed PA and 6 assessed MC. Findings indicated inconsistent associations between nature-based ECE and increased moderate-to-vigorous PA, and improved speed/agility and object control skills. There were positive associations between nature-based ECE and reduced sedentary time and improved balance. From the qualitative analysis, nature-based ECE affords higher intensity PA and risky play which could improve some motor competence domains. The quality of 28/31 studies were weak.

Conclusions

More controlled experimental designs that describe the dose and quality of nature are needed to better inform the effectiveness of nature-based ECE on PA and MC.

Systematic Review Registration

CRD42019152582

1. Background

Traditional ECE is typically characterised by predominately man-made structures, such as swings, climbing frames and slides in the playground with very few natural features integrated (1). Children who attend traditional ECE spend only a small amount of their time outdoors providing them with fewer opportunities to engage in physical activity and play (1, 2). In comparison, one emerging type of education, nature-based early childhood education (ECE), is characterised by integrating nature into its philosophy and design, and children would typically spend most of the day outdoors engaging with natural elements (3). Key characteristics of the environment may include trees, vegetation, natural loose-parts, rivers or ponds and other natural materials that enable interaction through play. Examples of nature-based ECE include nature-based preschool or kindergarten and forest kindergartens; however nature-based ECE can vary in approach, exposure and how much time children spend outdoors (3). By providing children with more time outdoors in a diverse environment, nature-based ECE may be an important way of increasing children’s physical activity levels and developing their motor competence.

It is widely accepted that engaging in regular moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (on average 60 minutes per day) in childhood can promote a range of physical, social, cognitive and emotional benefits; for example, weight management, bone density and mental wellbeing (4–6). However, children are increasingly living more sedentary lives resulting in low and declining levels of physical activity during formal education and rising childhood obesity (7–9). Approximately 41 million infants and young children (0-5 years) are living with overweight or obesity globally (10), and overweight is both a cause and consequence of low physical activity levels (11).

In addition to engaging in regular MVPA, it is also important to participate in different types of physical activities to develop children’s motor competence (12–14). Motor competence is the degree to which an individual is proficient in a broad range of motor skills (including coordination, and fine and gross motor skills) and their underlying mechanisms (15). Motor competence is important because it is associated with increased physical activity levels in childhood and children who engage in higher levels of physical activity tend to have better motor competence (16, 17). However, levels of motor competence are low in preschool and school aged children from high-income countries (18, 19), and this is likely impacting children’s current and future physical activity levels as they mature into adolescence and adulthood. Low levels of physical activity and motor competence during early childhood are also likely to impact maintenance of healthy weight status across the lifespan (16, 20). Additionally physical activity, particularly, outdoor play is favourably associated with most sleep outcomes in toddlers and preschool children (21).

If physical activity levels, motor competence and other physical outcomes are to be improved, intervening in the early years when children are rapidly developing is crucial, and the emergence of nature-based ECE may enhance these outcomes (18, 22). Nature-based ECE provides access to and diversity of features that provide children with multiple affordances to engage in active and outdoor play. Affordances are the opportunities the environment provides and how an individual perceives and interacts with them according to their individual capabilities (23–26). For example, a tree can enable children to climb, run around, or provide shelter. These natural elements may afford opportunities for diversifying play types, developing motor competence and increasing physical activity (27). When children spend time outdoors playing in ECE, approximately 40% of their time is spent engaging in physical activity (28) and some evidence has suggested motor competence may be developed if active play interventions are provided in ECE settings (29, 30). A recent systematic review explored the associations between exposure to nature (including ECE and non ECE settings) and children’s (0-12 years) health (31). Based on evidence with a ‘likely’ or ‘high’ risk of bias, they found favourable associations on physical activity and weight status and an indication of positive trends for motor competence (31). Similarly, based on weak evidence and a small number of studies, another systematic review indicated some association between nature play and physical activity and motor competence (32).

Although previously published systematic reviews have looked at the association of nature more broadly on child and adolescent health outcomes, to our knowledge, no systematic review that focuses specifically on the role of nature-based ECE on young children’s (2-7 years) physical health and development (for this paper that includes physical activity, motor competence, sleep, weight status etc.) exists. This novel systematic review will help identify the strengths and weaknesses that exist and the gaps that must be addressed to inform future evidenced-based policy at a national and global level. Therefore, the aims of this review were to:

-

a)

Determine if attending nature-based ECE is associated with or has an effect on children’s physical health and development

-

b)

Explore children’s, parent’s and/ or practitioner’s perceptions of nature-based ECE on children’s physical health and development

The mixed-methods approach was chosen to better understand the phenomenon of nature-based ECE (qualitative studies) and to measure its magnitude, trends, and effects on physical development (quantitative studies). This approach combined the strengths of, and compensated for the limitations of both research enquiries (33).

2. Methods

This systematic review protocol was registered to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42019152582) in October 2019 and published to BMC Systematic Reviews in September 2020 (34) and is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Adapted PRISMA for reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence (35). This systematic review is part of a research project synthesizing evidence on the relationship between nature-based ECE and children’s overall health and development (34). Findings for other outcomes will be presented in a separate publication.

Eligibility criteria

The selection criteria followed the widely used PI(E)COS (Population, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design) framework.

Population

Children aged 2-7 years attending ECE and who have not started primary or elementary school education were included. Children aged 2-7 years were chosen because this age group would typically attend ECE, accounting for global differences in ECE age range. Mean age, range or median reported in the study was used to assess eligibility. In instances where age was not reported, the study was included if it was conducted in an ECE setting. Studies that solely included a child population with disease conditions (autism, physical disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism etc) were excluded.

Exposure/Intervention

Studies were included if they incorporated nature into the ECE environment; For example, this may have involved children spending most of the ECE day outdoors in nature; interventions aimed at enhancing the amount and diversity of nature in the ECE playgrounds; the introduction of a garden-based intervention within the ECE curriculum; or the exploration of the associations of specific natural elements (e.g. hills, trees, grass, vegetation etc.) in the ECE setting on physical health outcomes. Studies that did not include nature in ECE settings were excluded; for example, traditional ECE where children would typically spend more time indoors and/or their environment was predominately manmade structures such as slides, swings or climbing frames. The exposures were categorised once full texts had been agreed and detail of these categories can be found in the methodology section.

Comparison

Comparison exposures where children attended traditional ECE that were typically indoors with provided less opportunities to spend time outdoors in an area that was not predominately nature-based. These outdoor areas tended to incorporate manmade structures.

Outcomes

Any child-level outcome related to physical health and development were included. For example, physical activity, motor competence, sleep, unintended consequences etc. Studies which included outcomes that were not child-level; for example, impact on practitioners were excluded, as were papers focused on changes (i.e. outcomes) to the ECE setting and studies using unvalidated questionnaires (for both quantitative and qualitative designs).

Study designs

Both quantitative and qualitative primary research designs were included. Qualitative studies were included if they explored perceptions on children’s physical health (from parent, practitioner or child) at a time when the child attended nature-based ECE. Qualitative studies were only included if they had a comparator (i.e., exposure, control group, pre/post) to understand whether there were improvements in child physical outcomes compared to baseline, the norm and/or other exposure. Quantitative study designs were included if outcomes were measured when children attended nature-based ECE, for example: cross-sectional and case-control studies measured when the child attended nature-based ECE; longitudinal, quasi-experimental and experimental studies with at least two time points; and retrospective studies if outcomes were assessed when the child attended nature-based ECE. Studies where the outcome could not be readily associated with the exposure (e.g. assessed the impact of attending nature-based ECE after the child had left) or reviewed only one child (e.g. case studies) were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

In October 2019, nine relevant electronic databases were searched (from inception onwards):

Education Research Information Centre (ERIC) − (EBSCOhost)

Australian Education Index − (Proquest)

British Education Index − (EBSCOhost)

Child Development and Adolescent Studies − (EBSCOhost)

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts − (Proquest)

PsycINFO − (EBSCOhost)

MEDLINE − (EBSCOhost)

SportDiscus − (EBSCOhost)

Scopus (Elsevier).

Grey literature was searched in Dissertation and Theses Database (ProQuest), Open Grey (www.opengrey.eu), and Directory of Open Access Journals (www.doaj.org) to capture dissertations and reports. The first 10 pages of Google Scholar were searched and checked, and websites of relevant organisations, professional bodies and other organisations involved in outdoor learning and play were searched for relevant publications. Finally, in August 2020, citation lists of eligible studies published from 2019 onwards were screened to identify recently published evidence that may have been missed in the initial searches.

Search strategies were constructed by three authors (AJ, AM and VW), two of which have topic expertise and one is an information scientist. To develop the comprehensive search strategy, relevant systematic reviews and publications were reviewed for key words and related terms. Draft searches were reviewed and refined by the co-authors who have expertise in fields related to nature, child health and development, education, and systematic review methodology. The strategy was tested and refined until a finalised search strategy was developed. Search strategies were adapted for each database and other web searches. The literature search was not restricted by year of publication or language. A draft search strategy for MEDLINE can be found in Supplementary File 1 (34). References were imported to Endnote and duplicates removed by one reviewer (AJ).

Selection procedure

Titles and abstracts were screened once (AJ, PM, RC, IF, SI, FL, BJ, VW) with 10% screened in duplicate independently (AM). Using Covidence (www.covidence.org/) software, full-text articles were screened by two researchers independently in duplicate. In instances when reviewers disagreed, a third reviewer resolved any disagreement (AM). Where multiple publications were reported for the same study, they were combined and reported as a single study.

Data Extraction

Data from eligible studies was extracted by one reviewer (AJ) and cross-checked by another reviewer (AM, PM or HT).

For quantitative studies, the following information was extracted:

Study ID (authors, year of publication)

Country

Study design (cross-sectional, controlled cross-sectional, controlled before and after etc.)

Participants (age, gender, socioeconomic status, sample size etc.)

Intervention/ exposure type and duration (nature-based ECE, ECE natural playgrounds etc.). Details on what any possible comparator groups received were also detailed (for example, characteristics of traditional preschool).

Outcome measures (type, assessment tool, unit and time point of assessment etc.)

Outcomes and results (effect estimates, standard deviation, confidence intervals etc.)

For qualitative studies, the following information was extracted:

Study ID (authors, year of publication)

Country

Participants (i.e. age, gender, socioeconomic status, sample size etc.)

Intervention/ exposure type and duration

Research aims

Outcome measures (interviews, focus groups etc.)

Outcomes and results (summary of key themes derived from data extractor and author).

Primary study authors were not contacted to obtain missing information due to constraints on time and the large volume of studies.

Quality appraisal of included studies

The quality of all included studies was assessed at study level by two reviewers independently (AJ, AM, PM, HT) and disagreements resolved through discussion. The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool (36) was used to assess the quality of quantitative studies. The EPHPP tool is a commonly used quality appraisal tool in public health that assesses quality across a variety of quantitative study designs (36). Minor modifications were made to the tool to ensure its relevancy for the present review, for example, defining target population, specifying confounders of interest and enhancing the overall rating of the paper (see Supplementary File 2).

The Dixon-Woods (2004) checklist (37) was used to assess the trustworthiness of eligible qualitative studies which provides a set of prompts that were designed to appraise aspects qualitative methodology. Studies were excluded from the review if the research questions were not suited to qualitative inquiry (question 2) or if the paper did not make a useful contribution to the review question (question 7) (see Supplementary File 2).

Data synthesis

Data synthesis was done in three stages. Firstly, for quantitative studies we considered conducting meta-analyses, however, calculating an overall effect size estimate could not be performed because only a small number of studies could be pooled, studies were heterogenous (as interpreted by the I2 statistic) and/or studies presented beta-coefficients only which introduce bias to the analyses when pooled. A sensitivity analysis, where studies with high risk of bias (i.e. poor study quality) are removed from the analysis, was also planned.

As a meta-analysis could not be performed, a Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) based on effect direction was performed (38). In this study, the effect direction plot is used to summarise findings at study level in instances where an outcome is reported in two or more studies. Study level effect directions are then synthesised considering study quality, design and sample size to present a summary effect direction at an outcome level. The synthesis by effect direction addresses a question of whether there is evidence of a positive or negative association. In addition, a narrative synthesis summarising the effect direction was conducted in instances where outcomes could not be grouped in the effect direction plot. Outcomes were grouped into six sub-domains: physical activity, motor competence, weight status, sleep, ultraviolet (UV) light exposure and unintended consequences were grouped by exposure which were determined after the screening phase to aid interpretation of findings. The exposure categories were a) nature-based ECE, b) ECE natural playgrounds and c) natural elements within ECE (see Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of the exposure categories.

| Nature-based ECE | This category represents studies with a higher exposure to nature. These ECE settings would integrate nature in their environment and children would spend most of their time outdoors in naturalised areas such as woods, forest and/ or naturalised playgrounds. Educators are usually present and may lead on structured educational activities. |

| ECE natural playgrounds | These studies tended to utilise interventions which have enhanced the nature in the ECE playground or studies which compare natural ECE playgrounds to ECE traditional playgrounds. Children would not typically spend as much time outdoors in these studies. |

| Natural elements within ECE | This category represents a lower exposure to nature and include studies (mostly cross-sectional in design) which looked at the association of specific natural elements within the ECE setting, such as trees, vegetation, hills, grass etc., or specific features or quality of the ECE playground on specific outcomes. |

Sub-group analyses were initially planned to investigate differential associations, however, the eligible studies limited our ability to conduct sub-group analyses (age, gender, duration spent in ECE etc.).

Secondly, for qualitative studies, a thematic analysis of author reported conclusions and participant quotes was conducted, where we extracted the central phenomenon of qualitative papers that was relevant to our review, and then grouped data into higher and lower order themes. One reviewer (AJ) analysed the data inductively, generating themes which were discussed with another two reviewers (AM, PM) who checked themes and clustering against quotes (both authors’ conclusion and participant quotes, were reported).

Finally, we integrated the syntheses of both qualitative and quantitative studies using a conceptual matrix. Findings from the synthesis of quantitative studies were mapped against the themes from qualitative studies identifying confirmative and contradicting findings. Findings from the qualitative synthesis were also used to hypothesise mechanisms of why or how quantitative results might have occurred.

Certainty of quantitative evidence

A Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was used to assess the certainty of the evidence across studies at an outcome level (39). Where two or more studies reporting on the same outcome were grouped, the risk of bias, precision, consistency, and directness was assessed. Based on these assessments, the certainty of evidence was upgraded or downgraded to provide an overall rating for the certainty of the evidence: very low, low, moderate and high (39). Given the absence of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the start rating was always low, however, as per GRADE, guidance could be upgraded. Publication bias could not be assessed because there were not enough studies..

3. Results

Results of the literature search

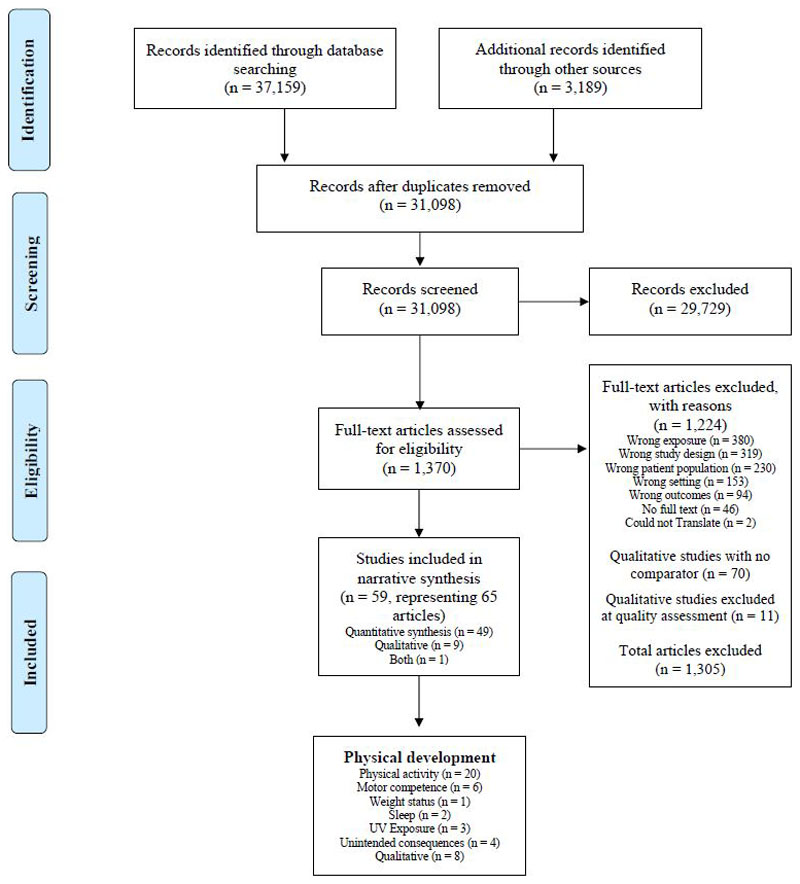

Figure 1 presents the summary of results from the systematic literature search. The headline figures (i.e. total number of ‘hits’) relate to the broader systematic review which encompasses cognitive, social, emotional and environmental outcomes in addition to physical outcomes (reported in this paper) (34). After duplicates were removed, 31,098 articles remained, of which 29,729 irrelevant titles and abstracts were excluded leaving 1,370 full text articles to be screened. 1,224 full-text articles were excluded with reasons detailed in Figure 1. Seventy qualitative studies were removed because they did not have a comparator (i.e. exposure, control group, pre/post) as did a further 11 studies after having their trustworthiness assessed. A total of 59 unique studies (representing 65 individual papers) met the inclusion criteria, of which, 39 included a physical outcome (31 quantitative and 8 qualitative) and were presented in this paper.

Figure 1. Result from the literature search.

Characteristics of the eligible studies

Geographical location

The majority of the studies were conducted in Norway (n=8) (27, 40–48), USA (n= 7) (49–55), Australia (n= 6) (56–61) and Canada (n=4) (62–65). Three studies each were conducted in Finland (66–68), Germany (69–71) and Sweden (72–74). The remaining studies were conducted in Denmark (75), Italy (76), Netherlands (77), Slovenia (78) and South Korea (79) (n= 1 study per county).

Study designs

Most study designs were cross-sectional (n= 16). Fewer were controlled cross-sectional (n= 7), uncontrolled before and after (n= 2) and controlled before and after (n= 6). The remaining 8 studies were qualitative.

Exposures

Studies were separated into three exposures (described in the methods section): nature-based ECE (n=18), ECE natural playgrounds (n=8) and natural elements within ECE (n=13). When studies included a control group, the control tended to be either a traditional ECE setting or traditional playground. In these conditions, children would spend more time indoors and their outdoor playground would predominately comprise of manmade structures such as swings and slides. There were instances where the control group also received some nature-based exposure, but this exposure was still less than in the experimental group.

Sample size and participant characteristics

The total sample size of the combined eligible quantitative and qualitative studies was n= 8,306 (n= 6,275 experimental/exposure group; n= 2,031 control). Sample sizes were small across the 39 eligible studies; only nine studies had a sample size greater than 200 (43, 55–57, 59, 66, 67, 69, 75), of which seven were cross-sectional or controlled cross-sectional (43, 57, 59, 66, 67, 69, 75) and two were controlled (56) or uncontrolled before and after (55). Sample size in the qualitative studies ranged from 12 (60, 68) to 75 participants (61).

Socioeconomic status (SES) was infrequently reported, but when it was reported it was generally moderate to high SES.

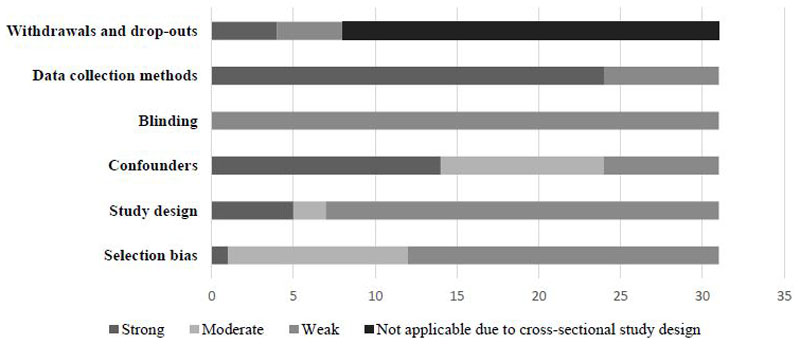

Quality of included quantitative studies

The quality of each study as assessed by the EPHPP tool can be found in Supplementary File 4. Of the eligible studies, only three studies were of moderate quality (56, 65, 79) with the remaining rated as weak. Of the three studies rated moderate quality, they represented each exposure (n=1 nature-based ECEs, n= 1 ECE natural playgrounds, n=1 natural elements within ECE). Figure 2 presents the quality rating across the 31 eligible quantitative studies by assessment item. Typically, items were rated weak because of selection bias, study design and it was unclear whether the outcome assessors and/ or participants were aware of the research questions (blinding). A weak rating for study attrition (withdrawals and dropouts) was provided in 50% of controlled before and after studies. Data collection methods tended to be valid and reliable, and confounders were rated strong or moderate in 24/31 studies.

Figure 2. Quality of quantitative studies by assessment item.

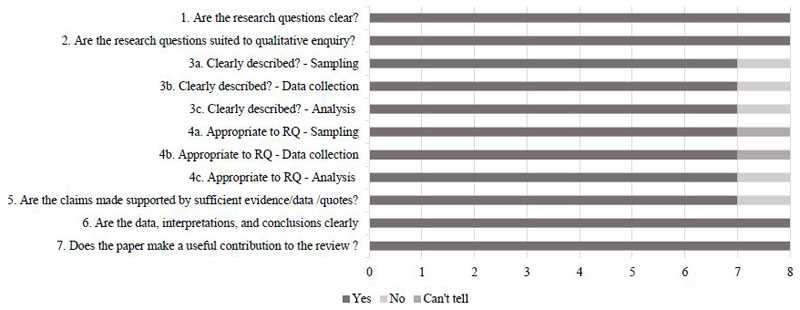

Trustworthiness of included qualitative studies

Figure 3 presents the findings of the trustworthiness of the included qualitative studies. Sampling (3a), data collection (3b) and analysis (3c) were not clearly described, analysis (4c) was not appropriate to the research question, and claims were not supported by sufficient evidence on one occasion. Finally, we couldn’t tell if sampling (4a) and data collection (4b) was appropriate to the research question on one occasion.

Figure 3. Trustworthiness of qualitative studies by assessment item.

Main findings - Quantitative studies

1. Physical activity (n=20 studies)

Of the eligible studies, 15 studies measured physical activity levels and sedentary time using devices; of which, 12 studies used the ActiGraph accelerometer (46, 51, 56–59, 62, 65–67, 75, 77), two studies used pedometers (71, 73) and one study used Global Positioning System (GPS) devices (78). The remaining five studies used observational methods such as the Observational System for Recording Physical Activity in Children-Preschool (OSRAC-P) or Children’s Activity Rating Scale (CARS) (44, 45, 52, 55, 63).

1.1. Nature-based ECE (n= 4 studies, n= 250 children)

Table 2 presents the effect direction plot for device-measured sedentary time (mins/ ECE day) and MVPA (mins/ ECE day) in eligible studies where these outcomes were reported in more than one study (51, 62). Two studies demonstrated a non-significant but positive association on sedentary time (i.e. lower sedentary mins/ ECE day) favouring children attending nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (51, 62). In one study, children who attended nature-based ECE engaged in 13.5 minutes less sedentary time compared to traditional ECE (51), in the other study the differences were marginal (one minute difference favouring nature-based ECE). For MVPA (mins/ ECE day), one study demonstrated a positive, but non-significant association where children attending nature-based ECE engaged in 6 minutes more MVPA compared to children attending traditional ECE (62). The other study showed a negative association where children who attended nature-based ECE engaged in 1.5 mins/ ECE day (95% CI: -2.8, 1.2) less MVPA compared to children attending traditional ECE (51).

Table 2. Nature-based ECE vs traditional ECE on physical activity.

| Study ID | Study Design | Sample size (E/C) |

Study quality | Sedentary time ⊕ |

MVPA ⊕ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Müller et al (2017)(62) |

Controlled before & after | 43 / 45 | Weak | ▲ | ▲ |

| Fyfe-Johnson et al (2019)(51) |

Controlled cross-sectional | 20 / 13 | Weak | ▲ | ▼ |

| Summary effect direction | ▲ | ► | |||

Abbreviations: E= experimental; C= comparison; MVPA= moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA= physical activity; ECE= Early childhood education.

GRADE − (assesses the certainty of evidence at an outcome level):

⊕ = Very low

Effect direction:

Study level: ▲= positive association with nature-based ECE; ▼= negative association with nature-based ECE.

Controlled before & after studies − difference between experimental and control group at follow-up (unless stated). Uncontrolled before & after studies − change since baseline (unless stated). Controlled cross sectional − difference between experimental and control (unless stated). Cross-sectional − positive, negative or no association.

Summary: ▲= studies show a positive association with nature-based ECE; ▼= studies show a negative association with nature-based ECE; ► = conflicting findings

Summary effect direction considers study quality, design (i.e. controlled before and after weighted more than cross-sectional) and sample size.

Additionally (not presented in Table 2), one study reported that children who attended nature-based ECE engaged in higher levels of habitual (mins/day) sedentary time and less light physical activity and MVPA across the full week, weekday and weekend compared to children who attended traditional ECE (51). The two studies that assessed physical activity using observational methods reported, i) that children who attended nature-based ECE were less stationary and engaged in more slow-easy and moderate physical activity compared to traditional ECE (63), and ii) children who attended nature-based ECE engaged in a range of physical activity types (52).

1.2. ECE natural playgrounds (n= 5 studies, n= 910 children)

In one intervention study where playgrounds were enhanced to incorporate more nature, device measured MVPA significantly decreased from baseline to follow-up by 1.32 mins/outdoor time (0.37 SE, p< 0.001) (65). However, a second intervention study indicated non-significant improvements from baseline to follow-up on MVPA (moderate to fast physical activity) and statistically significant improvements on physical activity (p= 0.001) and non-sedentary physical activity (slow to fast physical activity) (p= 0.001) as measured by Children’s Activity Rating Scale (CARS − observational assessment) (55). In this study, physical activity was a continuous variable including all five categories of the CARS assessment (1= stationary or motionless, 2= stationary with limb or trunk movements, 3= slow-easy, 4= moderate, and 5= fast), whereas MVPA (scored 4 or 5) and non-sedentary physical activity (scored 3, 4 or 5) were dichotomised (55). The other three cross-sectional studies found there was an association (p= 0.01) between CPM (raw total physical activity data collected by an accelerometer) in the natural and traditional (measured in spring and winter) playgrounds meaning CPM was similar across the environments (46); pedometer measured gait cycles/ min were lower in a nature playground (p= 0.109) compared to a traditional playground (71); and children covered a greater distance (km) (p= 0.132) when in a natural playground versus a traditional playground (78).

1.3. Natural elements within ECE (n= 11 studies, n= 3,663 children)

For the effect direction plot (see Table 3), six studies were grouped together for device measured MVPA. One study demonstrated a significant (β= 0.27, p< 0.01) association between natural elements (includes trees, shrubs, plants, hills, grass, rocks etc.) and increased MVPA (77). The other two studies suggested that higher vegetation (height in metres) (57) and natural elements (includes trees, shrubs, plants, logs, hills, grass, rocks etc.) (59) had a positive, but non-significant, association with MVPA. One study reported a non-significant difference between the experimental and control group (statistics not provided) (56) and two studies demonstrated a negative association (one significant, one non-significant) (58, 75). These studies demonstrated that MVPA decreased as the number of hilly landscapes (75), natural surfaces (58) and vegetation (58, 75) increased.

Table 3. Natural elements within ECE on physical activity.

| Study ID | Study Design | Sample size (E/C) | Study quality | Sedentary time ⊕ |

MVPA ⊕ |

Total PA ⊕ |

Step counts ⊕ |

CPM ⊕ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ng et al (2020)(56) |

Controlled before & after | 159 / 138 | Moderate | - | ■ | ■ | - | - |

| Boldemann et al (2006)(73) |

Cross-sectional | 199 | Weak | - | - | - | ▲ | - |

| Christian et al (2019)(57) |

Cross-sectional | 678 | Weak | - | ▲ | ▲ | - | - |

| deWeger (2017)(59) |

Cross-sectional | 274 | Weak | - | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ |

| Gubbels et al (2018)(77) |

Cross-sectional | 151 | Weak | ▲ | ▲ | - | - | ▲ |

| Määttä et al (2019)(66) |

Cross-sectional | 864 | Weak | - | - | ▲ | - | - |

| Määttä et al (2019b)(67) |

Cross-sectional | 655 | Weak | ▲ | - | - | - | - |

| Olesen et al (2013)(75) |

Cross-sectional | 441 | Weak | - | ▼ | - | - | - |

| Sugiyama et al (2012)(58) |

Cross-sectional | 89 | Weak | ▼ | ▼ | - | - | - |

| Summary effect direction | ▲ | ► | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | |||

Abbreviations: E= experimental; C= comparison; MVPA= moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA= physical activity; ECE= Early childhood education.

GRADE − (assesses the certainty of evidence at an outcome level):

⊕ = Very low

Effect direction:

Study level: ▲= positive association with nature-based ECE; ▼= negative association with nature-based ECE; ■ = statistics not presented.

Controlled before & after studies − difference between experimental and control group at follow-up (unless stated). Uncontrolled before & after studies − change since baseline (unless stated). Controlled cross sectional − difference between experimental and control (unless stated). Cross-sectional − positive, negative or no association.

Summary: ▲= studies show a positive association with nature-based ECE; ▼= studies show a negative association with nature-based ECE; ► = conflicting findings

Summary effect direction considers study quality, design (i.e. controlled before and after weighted more than cross-sectional) and sample size.

Four studies were grouped together for device measured total physical activity. Vegetation, natural elements, grass, and rocks had a positive association with total PA (min/ECE day) in three studies, but these were non-significant (57, 59, 66). One study reported non-significant difference for natural elements between the experimental and control groups (statistics not provided) (56). Although Määttä et al (2019) reported a non-significant positive association for some natural elements (grass, rocks), they also reported that forest and trees were negatively associated (non-significant) with total physical activity (mins/ ECE day) (66). Additionally, two studies that assessed total physical activity using observational methods reported that nature was not a predictor of physical activity (44) and not associated with observations with high wellbeing and physical activity (45). These studies could not be grouped together in the effect direction plot because one study measured physical activity only (44) and the other combined physical activity and wellbeing (45).

Three studies were grouped together for device measured sedentary time (58, 67, 77), of which, two demonstrated a significant positive association (in the case of sedentary time this is reflected by a negative statistical association, i.e. higher natural elements/lower sedentary time) (67, 77) and one demonstrated a non-significant negative association (58). For example, higher frequency of nature trips (β= −1.026, 95% CI: −1.804, −0.248), p = 0.010) (67) and natural elements (β= −0.31, p< 0.001) (77) were significantly associated with lower levels of sedentary time (67). Natural surfaces (used in effect direct plot as this variable is comparable to other studies that assessed sedentary time) and vegetation were associated with increased sedentary time (all non-significant) (58). However, this study also reported hills and shade were associated with lower levels of sedentary time (mins/ outdoor time) (58).

For step counts, one study reported a significant association (p<0.001) with high environment score (playgrounds which had a large outdoor area and integrated play areas with natural elements) (73). Similarly another study reported a significant positive association between natural elements and step counts (59).

Two studies demonstrated a positive association between natural elements and CPM (59, 77), of which one reported a significant association on habitual CPM (β= 0.21, p< 0.01) (77).

2. Motor competence (n= 6 studies, n= 430 children)

2.1. Nature-based ECE

Within the effect direction plot (presented in Table 4), three studies were grouped together for balance and speed and agility (27, 40–42, 70), and two for object control skills (42, 62). For balance, a significant positive relationship was found in two studies in children who attended nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (27, 40, 41, 70), with one other study suggesting better balance in traditional ECE (42). For object control skills, one study reported a non-significant positive association in children who attended nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (62), the other suggested that there was a non-significant negative association between object control skills and nature-based ECE (42). For studies assessing speed and agility, one study highlighted a non-significant positive association with nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (27, 40, 41). The other two studies were suggestive that children’s speed and agility was better in the traditional ECE compared to the nature-based ECE (27, 40–42, 70).

Table 4. Nature-based ECE vs traditional ECE on motor competence and unintended consequences.

| Study ID | Study Design | Sample size (E/C) | Study quality | Balance ⊕ |

Object Control ⊕ |

Speed & agility ⊕ |

Illness ⊕ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ene-Voiculescu & Ene-Voiculescu (2015)(27,40,41) | Controlled before & after |

46 / 29 | Weak | ▲ | - | ▲ | - |

| Müller et al (2017)(62) | Controlled before & after |

43 / 45 | Weak | - | ▲ | - | - |

| Lysklett et al (2019)(42) | Controlled cross sectional |

43 / 49 | Weak | ▼ | ▼ | ▼ | - |

| Scholz & Krombholz (2007)(70) | Controlled cross-sectional |

45 / 84 | Weak | ▲ | - | ▼ | - |

| Frenkel et al (2019)(50) | Controlled cross-sectional | 71 / 70 | Weak | - | - | - | ▲ |

| Moen et al (2007)(43) | Controlled cross-sectional | 267 / 264 | Weak | - | - | - | ▼ |

| Summary effect direction | ▲ | ► | ► | ► | |||

Abbreviations: E= experimental; C= comparison; ECE= Early childhood education.

GRADE − (assesses the certainty of evidence at an outcome level):

⊕ = Very low

Effect direction:

Study level: ▲= positive association with nature-based ECE; ▼= negative association with nature-based ECE.

Controlled before & after studies − difference between experimental and control group at follow-up (unless stated). Uncontrolled before & after studies − change since baseline (unless stated). Controlled cross sectional − difference between experimental and control (unless stated). Cross-sectional − positive, negative or no association.

Summary: ▲= studies show a positive association with nature-based ECE; ▼= studies show a negative association with nature-based ECE; ► = conflicting findings

Summary effect direction considers study quality, design (i.e. controlled before and after weighted more than cross-sectional) and sample size

For outcomes that could not be grouped and presented in an effect direction plot, one study reported higher scores in body awareness, gross motor skills and fine motor skills in children who attended nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (all non-significant) (76). Locomotor skills (running, skipping, hopping) were significantly (p= 0.03, η2= 0.06) better in children who attended nature based ECE compared to traditional ECE; however, perceived motor competence was marginally lower in children who attended ECE (non-significant) (62). Total motor competence (including manual dexterity, ball skills and balance) and total fitness scores were worse in children who attended nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (non-significant) (42). Scores for skipping were also significantly better in children who attended nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE at follow-up (27, 40, 41). Finally, children who attended nature-based ECE performed significantly better in a measure of strength (hanging on pull up bar) and jumping compared to children who attended traditional ECE (70).

3. Weight Status (n= 1 study, n= 172 children)

3.1. Natural elements within ECE

Findings from one study reported a non-significant association between children who attended ECE settings with high environment quality (i.e. large space, vegetation, tress etc.) and BMI (p= 0.07) and waist circumference (p= 0.25) compared to low environmental quality (74).

4. Sleep (n= 2)

4.1. Nature-based ECE (n= 1 study; n= 37 children)

Sleep was assessed using the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) which consists of eight sleep domains: bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night wakings, parasomnia, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness (79). Total sleep time was also assessed. All sleep domain scores were better in children who attended nature-based ECE compared to children who attended traditional ECE; total CSHQ score (p< 0.01), sleep disordered breathing (p= 0.04) and daytime sleepiness (p< 0.01) were significantly different (79). Total sleep time was marginally higher in children who attended nature-based ECE (10.5 hours ± 1.0 vs 10.4 hours ± 0.9) compared to children who attended traditional ECE, but this was non-significant (79).

4.2. Natural elements within ECE (n= 1 study; n= 172 children)

There was a significant association (p= 0.03) between environment quality and mean sleep time (minutes) (74). Children who attended ECEs with high environment quality had a mean sleep time of 658 minutes ± 44 compared to lower environment score 642 minutes ± 32 (74). ECE playgrounds with a high environment quality are ones which have a large space, trees, vegetation, hilly terrain and integrated with play structures.

5. UV Exposure (n= 3 studies, n= 941 children)

5.1. Natural elements within ECE

UV exposure was lower and significantly associated with ECE playgrounds with a higher environmental quality in three studies (57, 72, 73). ECE playgrounds with a higher environmental quality are those that have vegetation and trees integrated into the playgrounds to provide sufficient shade for children (57, 72, 73).

6. Unintended consequences (n= 4)

6.1. Nature-based ECE (n= 3 studies, n= 2,379 children)

Two studies assessed illnesses and sickness absenteeism using parent or teacher reported days absent from school (43, 50). Based on the effect direction plot (Table 4), one study found a non-significant positive association between nature-based ECE and illnesses (i.e. illnesses were lower in children who attended nature-based ECE) (50). The other study reported a non-significant (p> 0.05) negative association between nature-based ECE and sickness absenteeism (i.e. sickness absenteeism was lower in children who attended nature-based ECE) (43).

Other unintended consequences reported related to minor injuries (e.g., wounds, cuts and sprains) and tick bites and borreliosis (or Lyme’s Disease). For minor injuries, one study reported non-significantly less minor injuries for boys who attended nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (50). However, minor injuries were significantly higher for girls who attended nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (50). Tick bites and borreliosis were significantly more prevalent in nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE (73% vs 27% and 2% and 0.4% respectively) (69).

6.2. Natural elements within ECE (n= 1 study, n= 172 children)

One study reported no association (p= 0.12) between environment quality (high and low) and symptoms of illness (runny nose, cough fever, respiratory problems etc.) (74).

Findings per eligible study can be viewed in Supplementary File 5.

Main findings-Qualitative studies

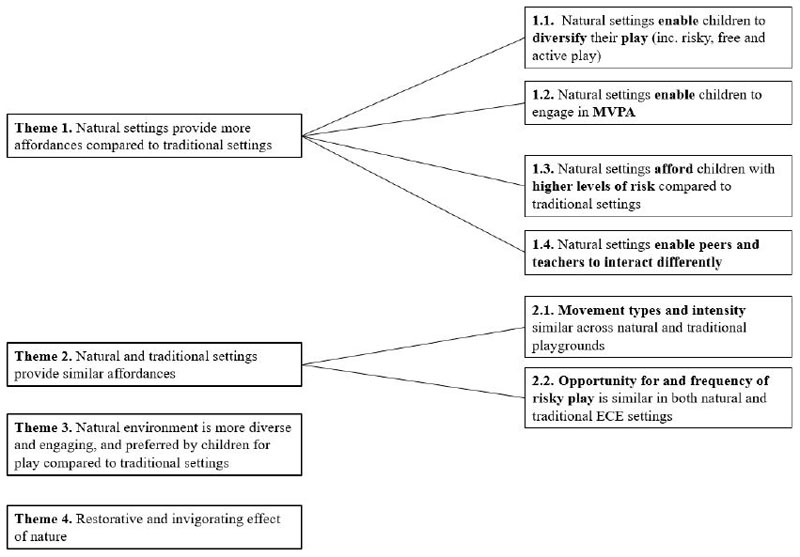

Eight studies were included in the thematic analysis, of which, five studies involved nature-based ECE and three studies were ECE natural playgrounds (study characteristics of qualitative studies can be found in Supplementary File 3). Studies tended to use direct observation and interviews (predominately with educators) to collect qualitative data. Findings from the thematic analysis are presented in Figure 4 and show four higher order themes.

Figure 4. Findings from the thematic analysis.

Theme 1. Natural settings provide more affordances compared to traditional settings

Theme 1 indicated the importance of the natural environment for affording opportunities to enhance a range of physical outcomes. For example, six of the included studies noted that the natural environment enabled children to engage in more physical types of play, such as risky, active and free play (47, 53, 54, 60, 61, 68). The importance of the natural environment for engaging in MVPA was noted in two studies (48, 68). This connection between play, motor competence and physical activity afforded by the natural environment can be summarised in the following quote:

“High physical-motor levels are created, the children jump down and run back up. They talk, shout and laugh. Three of the girls jump together and try to land in differing ways. They hold hands and try to jump together from the small knoll. There is laughter. They are eager and enduring. The small knoll has many opportunities for variation, in height and width, which invite challenges suitable for each child’s resources. The children have visual, verbal and physical contact with each other. The top of the knoll provides an overview. Some find it scary the first time they try, but together they challenge each other, supporting and encouraging each other. The children decide how much they will participate and how they jump, and how they wish to solve the challenges offered by the knoll” (48).

This quote also highlights “risk” in children’s play. Risky play is characterised by play that is “thrilling and exciting and where there is a risk of physical injury” (80). Although, this may seem potentially harmful to children, this type of play is important for children’s development as children actively engage in risk assessment, in which they must judge the benefit and consequences of dealing with such unpredictability (81). It was reported that the natural environment afforded higher levels of risk in two studies (47, 64).

I like playing in the fallen logs and trees on the playground; it is so much fun, but a bit scary too! I like the big pile of sticks and logs that we made − it is for another fort that is going to be really high off the ground" (64).

The final aspect of this theme relates to the importance of social interactions in relation to encouraging play and physical activity. Four studies also noted the importance of teachers and educators’ interactions with children in relation to encouraging play and physical activity (48, 53, 60, 64).

“I try to do different things with them every day. Like I said, we play with them at least ten minutes. So, I try to run, parachute, the blocks, climbing, sliding down the slides” (53).

Theme 2. Natural and traditional settings provide similar affordances

Despite Theme 1 indicating the importance of affordances for a range of physical outcomes, some studies also reported that setting type provided similar affordances. Two sub themes were reported: a) movement types and intensity were similar across natural and traditional playgrounds (61) and b) frequency of risky play is similar in both nature-based and traditional ECE settings (47). The latter sub-theme relates the findings reported on risky play in Theme 1. Taken together, children will seek risk irrespective of playground type, however, the nature-based ECE affords greater risk (Theme 1) (47).

“Comparing the two play environments, they both seem to include an extensive amount of affordances for risky play. At both preschool playgrounds, there are opportunities for play in great heights such as climbing, jumping down, and balancing and as well as opportunities for play with high speed such as swinging, sliding/sledding, running, and bicycling.” Taken from authors conclusions (47).

Theme 3. Natural environment is more diverse and engaging, and preferred by children for play compared to traditional settings

Two studies reported children’s preference for the natural environment (48, 64). It appears when children are outdoors in nature it affords them the opportunity to play in a diverse environment with their friends and this combination provides enjoyment.

"I like going outside and playing! I like playing with my friends, Sydney and Megan. We play hide and seek on the playground and hide in the forest in the logs and trees. I like outside because it’s so fun and I really like to play. Sometimes I play with my sister too; I like all the colours outside and all the space" (64).

Theme 4. Restorative and invigorating effect of nature

One study indicated the importance of the natural playground in helping children invigorate and/or restore their energy for play and physical activity (68). For example, the natural environment for some children provides them with more energy to continue playing, however, other children may feel the requirement to nap thus restoring their energy to engage in more play.

“Now it’s become very difficult to finish playing. They would rather continue, and those who need to take a nap, they’ve had a nice, long time outdoors and nice games so they fall asleep more easily, and it affects their energy in the afternoon. Some children have very long days here. They come in the morning and stay until five o’clock; they seem to be somehow energetic and lively in the yard. This is new for us. The contrast to the previous yard is so great that the effects can be seen here very quickly” (68).

Synthesis of quantitative and qualitative findings

Of the outcomes assessed in quantitative studies, sedentary time, weight status and UV exposure did not appear as a theme from the qualitative studies. Supplementary File 6 shows the matrix relating themes from the qualitative evidence synthesis with the findings from the quantitative evidence synthesis. The matrix indicates where findings from the two data sources were confirmatory or conflicting. Themes not present in the matrix reflects where data could not be directly linked to the results of the quantitative synthesis. However, these themes were considered for generating a hypothesis on how or why observed quantitative results occurred.

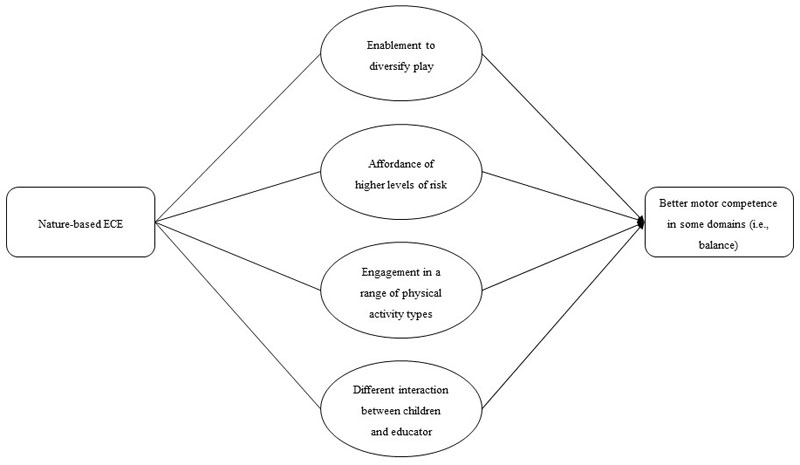

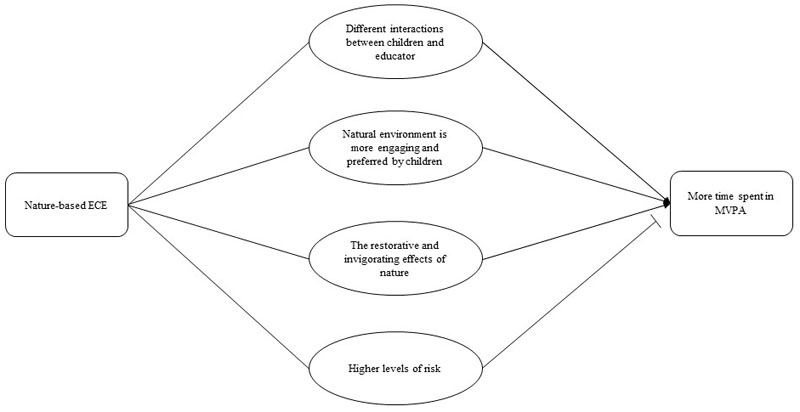

Findings from the quantitative synthesis suggested that some aspects of motor competence, such as balance, are better in children attending nature-based ECE compared to traditional settings. This might be achieved because natural settings enable children to diversify their play, engage in a range of physical activity types and allow a different child-child and child-educator interaction (i.e. encourage more play interactions). Nature-based ECE might also afford children with higher levels of risk compared to traditional ECE which foster development of motor competence to a greater degree (see Figure 5 for visual representation). Limited evidence from quantitative studies did not support the theme that any of the natural spaces (nature-based ECE, ECE natural playgrounds and natural elements within ECE) enable children to engage in MVPA (device measured). The educator observed benefit of natural settings for higher intensity physical activity (Figure 4) might be achieved through the perception that the natural environment is more engaging and preferred by children compared to traditional settings. The restorative and invigorating effects of nature - manifested in higher energy levels for play and/or the requirement to nap to restore energy levels - could benefit the duration in which children engage in higher intensity physical activity. While the perceived higher level of risk in nature-based ECE compared to traditional ECE might benefit the development of motor competence, time spent in MVPA might be reduced to manage (i.e. more deliberate and slowed movement) the riskier situations (see Figure 6). Equally, a similar opportunity and frequency of risky play in both natural and traditional spaces (ECE setting and playground) might explain why the theme ‘movement intensity is similar across natural and traditional spaces’ is not supported by findings from the quantitative synthesis.

Figure 5. Hypothesized pathway on how Nature-based ECE can benefit motor competence.

An arrow denotes where factors are hypothesised to lead to better motor competence

Figure 6. Hypothesized pathway on how Nature-based ECE might influence MVPA levels.

An arrow denotes where factors are hypothesised to lead to more time spent in MVPA. A blocked end highlight high levels of risk does not lead to more time spent in MVPA.

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to understand whether nature-based ECE is associated with children’s physical activity, sedentary behaviour, motor competence and other physical health outcomes. Based on the effect direction plot, findings indicated inconsistent associations between nature-based ECE and children’s MVPA, speed and agility, object control skills and illnesses (unintended consequences). However, positive and consistent associations were found for sedentary time and balance. Consistent positive associations were also found between specific natural elements (e.g. vegetation) and different physical activity types (sedentary time, total physical activity, step counts and CPM).

Physical activity was the most assessed outcome across the three exposure categories. Findings were inconsistent for the association of attending nature-based ECE on children’s MVPA during the ECE day. This inconsistent finding has been found in other conceptually similar systematic reviews. For example, a systematic review that aimed to understand the impact of participating in nature play on children’s (2–12 years) on physical activity levels found that, of the five studies that used device measured physical activity, only one study reported a significant difference and three studies reported no change (32). One reason for this finding might be that studies were underpowered to detect differences between exposures. In the present review, the two studies that assessed the association between nature-based ECE on children’s physical activity had small sample sizes (<50 in experimental group) and, therefore, are unlikely to be adequately powered to detect changes in physical activity. Another reason might be that level of risks afforded in the nature-based ECE was too high to allow an increase in time spent in higher physical activity levels. Similarly, other factors such as interactions between children and educators could influence physical activity levels. Lack of assessing factors that might mediate or moderate the associations between nature-based ECE on children’s physical activity make it difficult to interpret the observed result. Despite not being able to draw conclusions on the effect of nature-based ECE on children’s physical activity levels, evidence from cross-sectional studies indicated certain natural elements (e.g. vegetation, grass etc.) were positively associated with different physical activity intensities. However, these studies are limited in that they cannot determine casual inference.

However, a further important consideration regarding MVPA and other physical activity outcomes is that the inconsistent findings across reviews including the current study is perhaps indicative of it being poorly matched, theoretically, as an important outcome. Mechanistically, MVPA may not be the most appropriate outcome resultant from engaging in nature-based ECE, where the affordances created by the diverse natural environment provide opportunities for children to engage in diverse types of play (sociodramatic, symbolic, narrative etc.) on their own terms, but this may not manifest in high intensity physical activity as such. However, the benefits of engaging in diverse play types, despite potentially not being high intensity, may impact motor competence and other important outcomes not presented in this paper, such as general wellbeing, cognitive, and social and emotional outcomes. This speaks to a related issue in this field, on how to best capture the range of movement behaviours that children are likely to participate in. In eligible studies that used device-measured physical activity, the ActiGraph accelerometer was the most commonly used method. The ActiGraph accelerometer is useful for physical activity intensity, such as measuring time spent in MVPA, however, it has important limitations in that it cannot accurately detect changes in posture (82) or upper body movement (if the monitor is placed at the hip). In nature-based ECE, children will engage in a range of full-body movement behaviours through play that the ActiGraph may be unable to detect, such as climbing, balancing, or lifting objects. Device measured engagement in physical activity is a step forward in our understanding of nature-based ECE programme effects. However, it is important that consideration is given, in pre-evaluation stages of development, to the appropriate measurement tools to capture the desired physical manifestation of the outcomes deemed to be a consequence of engaging in nature-based ECE. For instance, where postural classification (e.g. sit, stand, step) or postural change is deemed to be an important outcome of interest, the activPAL (83); or an alternative method, such as direct observation might be more suitable for measuring children’s range of movement in nature-based ECE, such as climbing, jumping, balancing etc. Where possible, measurement of movement (e.g. physical activity, play, motor competence) should be well thought out as part of the evaluation design, where strengths and limitations are discussed and ideally using participatory approaches with a variety of informed stakeholders.

Given the lack of supportive evidence for MVPA in this review, motor competence, likely developed through engaging in a range of play types in nature-based ECE, may be a more appropriate outcome which would manifest in higher levels of MVPA as children mature into adolescence. For motor competence outcomes, findings indicated a positive association between nature-based ECE and children’s balance, and inconsistent findings on speed and agility, and object control skills. Speed and agility used a standard shuttle run, and although there were inconsistent associations, these differences between nature-based ECE and traditional ECE were marginal. When examining similar systematic reviews in this area, positive associations between exposure to nature on children and adolescents (0-12 years) fine and gross motor skills have been reported (31). Of the observational studies, 66.6% indicated positive associations between nature and fine and gross motor skills; in the experimental studies, 60% reported improvements in gross motor skills (31). Existing literature has indicated that motor competence in preschool children tends to be low (18) and more robust studies with larger samples are required to understand whether nature-based ECE improves motor competence more than the developmental norm. Improvement in motor competence is particularly important as the early years (2-7 years) is the period when motor competence development occurs (84), and it underpins physical activity (16, 17). Future work may also consider exploring different motor competence categories, stratified by gender, as previous research has suggested that object control skills are associated with increased physical activity for boys and locomotor skills are associated with increased physical activity for girls (18, 85). In addition, as our integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitive data revealed, assessment of play, risk, physical activity type, and child-educator interaction might provide further insights into how nature-based ECE can achieve improvements in children’s motor competence.

The remaining outcomes, weight status (n= 1), sleep (n= 2), UV exposure (n= 3) and physical unintended consequences (n= 4) were only assessed in a small number of eligible studies. Limited measurement of other physical outcomes seems common among conceptually similar systematic reviews (31, 86). One systematic review exploring the influence of nature experiences on children and adolescent’s BMI found improvements (non-significant) in weight status across four eligible studies (86); however, the quality of evidence was low so findings should be interpreted with caution (86). A larger synthesis of 17 observational studies reported generally favourable associations between exposure to nature on children (0-12 years) and weight status (31). Of the 66 analyses, 68% indicated improvements in obesity and/or overweight (31). Further evidence to understand the role of nature-based ECE on pre-school aged children’s weight status is needed, including the possible mechanisms. For example, literature suggests that improvements in weight status is associated with motor competence and physical activity (16, 20). There is also an evidence gap with no studies included in the present systematic review exploring the role of nature-based ECE on children’s diet and nutrition; this may be an important area given that possible associations with physical activity, sedentary time, or sleep would also have dietary impacts. Attention is also required on the impact of nature-based ECE on other physical outcomes that have had limited or no attention in the eligible studies (sleep, weight status, unintended consequences etc.).

It is important to note, that for some outcomes one might not expect to see a difference between nature-based and traditional ECE as there might not be plausible mechanisms to suggest an added value of exposure to nature resulting in an observed between group difference (for example, object control, ball skills, manual dexterity, fitness).

Strengths and limitations of the reviewed evidence

A total of 39 unique studies reported a physical outcome, of which n= 6 studies were controlled before and after. These studies reflected a geographical spread of high-income countries, including countries from North America, Europe, Australia, and Asia which ensure global relevancy of the review. Quantitative studies also tended to use valid and reliable measures for assessing outcomes and confounders were rated strong or moderate in 24/31 studies and qualitative studies demonstrated trustworthiness. However, no studies were conducted in low- or middle-income countries and three important factors limited our ability to draw conclusions on the findings: a) study quality, b) limited description of the exposure, and c) certainty of evidence.

Study quality was mostly impacted by two interconnected factors: a) most studies had a cross-sectional design (23/31) which means causal inference cannot be determined and b) most studies were rated weak (28/31). Based on the EPHPP Tool, the eligible studies were rated weak across the selection bias, blinding and attrition (before and after studies only) domains. For the study design domain, all cross-sectional studies were given a weak rating, uncontrolled before and after studies were given a moderate rating, and controlled before and after studies were given a strong rating. Furthermore, most studies did not report any formal power calculation (including identification of size of effect) and/or had small sample sizes, meaning that they may not have been adequately powered to detect changes.

The inconsistency and/or limited description of the exposure also limited out ability to draw conclusions. For example, for the physical activity outcome, one study did not explain the exposure or dose of nature the children received (62) and the other reported the control group received a weekly 2-hour “nature-based outdoor enrichment class” (51) − raising the question of potential dilution of programme effect on the outcome of interest (physical activity). These examples highlight an inherent problem across many of the included studies, the exposure and dose of nature received was inconsistently described, unclear, of indeterminate dose, or of potentially comparable level to their ‘control’ counterparts. In a recent narrative review by Holland and colleagues, they discussed limitations surrounding measurement of nature (87). The authors recommended that future research must clearly describe the complexity of the nature exposure, including time spent in nature, frequency of visits, and quantifying the nature (e.g. amount of greenspace, types and number of trees etc.) (87). Given that health is impacted by nature through several possible mechanisms, describing the nature children are exposed to clearly (as above) will provide important information on the specific pathways in which nature-based ECE is likely to impact on physical health outcomes (87).

Finally, GRADE assessments rated all evidence as very low as the absence of RCTs meant the start rating was low across all outcomes. In this field, it is unlikely that the “gold standard” RCT design could be used to evaluate the effect of nature-based ECE on child health outcomes. Therefore, despite following standard GRADE procedures, the certainty of evidence does not necessarily reflect the ‘best available evidence’ in the field more broadly. Furthermore, certainty of evidence with limited variation across outcome results makes it difficult to draw conclusions on the evidence. The challenges of applying GRADE to public health research has also been mentioned by Hilton-Boon and colleagues (88).

Strengths and limitations of the review process

At the development phase, a steering group of experts from policy, research and practice was created to ensure relevancy and rigour of the review. To capture as much relevant research, nine databases were searched and not limited by study design, publication year or language. Additional to published research, websites and grey literature were included in the search, and experts from policy, practice and research were contacted to provide evidence. The purpose of including this evidence and not only robust study designs was to ensure synthesis of the best evidence to date which is vital to informing future directions of the research. Both quantitative and qualitative evidence was considered in a mixed-methods evidence synthesis. This allowed us to better understand the phenomenon of nature-based ECE (qualitative studies) and to measure its magnitude, trends, and effects on physical development (quantitative studies) of children. Finally, we followed a robust systematic review protocol, thus the risk of bias in our review methodology is low.

Despite following strict systematic review procedures, the review also had a few limitations. Firstly, given the large number of articles retrieved, title and abstract screening were not conducted in duplicate. However, to mitigate this limitation a second reviewer checked 10% of the titles and abstracts. Secondly, we made minor modifications to the EPHPP tool to define the target population, specify confounders of interest and refining the overall rating of the paper to ensure the tool was relevant to the present review.

Future directions

The current evidence base is limited by weak study designs, nature exposure being poorly described, and an understanding of which physical outcomes are of most importance to children resultant from engaging with nature based-ECE (e.g. play and motor competence rather than MVPA). These current limitations need to be addressed to help inform decision makers (e.g. funding institutions such as local/national governments) to inform where investment in nature-based ECE should be made.

To begin to understand the true impacts of nature-based ECE on children’s physical health and development, evidence needs to move towards controlled studies that are adequately powered to detect changes in outcomes measured, factor important confounders (age, gender, SES, previous exposure to nature) and assess attrition. If future studies addressed the inherent problems with study design and exposure then the evidence base would be elevated allowing us to draw stronger conclusions on whether nature-based ECE is, similar to or better than traditional ECE approaches.

Finally, it is likely that there are longer term impacts of attending nature-based ECE, however, long term impacts were not assessed in eligible studies. This means we cannot draw firm conclusions on what longer term outcomes may be or what the causal mechanisms by which possible outcomes were improved. For example, as mentioned previously, we know from other evidence that motor competence and physical activity are associated which is likely to impact a child’s weight status. Similar pathways could also be drawn between motor competence, physical activity and sleep as well as many other cognitive, social and emotional outcomes. However, to understand any of these longer-term benefits, we also need to understand if any possible benefits are sustained as children transition into primary/ elementary education where they may spend more time indoors in sedentary behaviour and with less exposure to nature.

Conclusions

Based on very low certainty of evidence, findings indicated inconsistent associations between nature-based ECE and children’s MVPA, speed and agility, object control skills and illnesses. However, positive and consistent associations were found for sedentary time and balance. Consistent positive associations were also found between specific natural elements (e.g. vegetation) and different physical activity types (sedentary time, total physical activity, step counts and CPM). To enable stronger conclusions more high-quality evidence is needed where the nature exposure is adequately described and appropriate outcomes (e.g. different play types) are assessed over a longer duration. By building this evidence base we will be able to inform policy, practice and research whether nature-based ECE is equal to, or better than traditional ECE.

List of Abbreviations

- ECE

Early childhood education

- EPHPP

Effective Public Health Practice Project

- ERIC

Education Research Information Centre

- MVPA

Moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity

- PI(E)COS

Population, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- SES

Socioeconomic status

- SWiM

Synthesis Without Meta-analysis

- UV

Ultraviolet

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding Source

AJ was supported by the Scottish Government’s Early Learning and Child Care Directorate (grant number 307242-01).

PM was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and Scottish Chief Scientific Officer (grant numbers MC_UU_12017/10, MC_UU_00022/4; SPHSU10, SPHSU19) and the Scottish Government’s Early Learning and Child Care Directorate (grant number 307242-01).

RC was partly supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, under Grant UIDB/00447/2020 to CIPER - Centro Interdisciplinar para o Estudo da Performance Humana (unit 447).

JJR was supported by the Scottish Funding Council.

HT and VW were supported by the UK Medical Research Council UK and Scottish Chief Scientific Officer (grant number MC_UU_12017/13, MC_UU_12017/15, MC_UU_00022/2; SPHSU13, SPHSU15, SPHSU17).

AM was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and Scottish Chief Scientific Officer (grant numbers MC_UU_12017/14, MC_UU_00022/1, SPHSU14, SPHSU16) and the Scottish Government’s Early Learning and Child Care Directorate (grant number 307242-01).

Footnotes

Authors' contributions:

AJ, AM, VW developed the search strategy in consultation with all authors. AJ, PM, AM, RC, IF, SI, FL, BJ, VW screened the articles. AJ, PM, AM, HT conducted quality appraisal and data extraction. AJ, PM, and AM drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors made substantial contribution to the conception of this work. All authors read and approved the manuscript. AM and PM take responsibility of the integrity of the work.

Contributor Information

A Johnstone, Email: avril.johnstone@glasgow.ac.uk.

P McCrorie, Email: Paul.McCrorie@glasgow.ac.uk.

R Cordovil, Email: ritacordovil@fmh.ulisboa.pt.

I Fjørtoft, Email: Ingunn.Fjortoft@usn.no.

S Iivonen, Email: susanna.iivonen@uef.fi.

B Jidovtseff, Email: b.jidovtseff@uliege.be.

F Lopes, Email: fredericolopes@fmh.ulisboa.pt.

JJ Reilly, Email: john.j.reilly@strath.ac.uk.

H Thomson, Email: Hilary.Thomson@glasgow.ac.uk.

V Wells, Email: Valerie.Wells@glasgow.ac.uk.

A Martin, Email: Anne.Martin@glasgow.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Lerstrup I, Konijnendijk van den Bosch C. Affordances of outdoor settings for children in preschool: Revisiting heft’s functional taxonomy. Landscape Research. 2017;42(1):47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broekhuizen K, Scholten AM, de Vries SI. The value of (pre) school playgrounds for children’s physical activity level: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2014;11(1):1–28. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobel D. Learning to walk between the raindrops: The value of nature preschools and forest kindergartens. Children Youth and Environments. 2014;24(2):228–238. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British journal of sports medicine. 2020;54(24):1451–1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age web annex: evidence profiles. World Health Organization; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmons BW, LeBlanc AG, Carson V, et al. Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0– 4 years) Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2012;37(4):773–792. doi: 10.1139/h2012-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aubert S, Barnes JD, Abdeta C, et al. Global matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: results and analysis from 49 countries. Journal of physical activity and health. 2018;15(Supplement 2):S251–S273. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper AR, Goodman A, Page AS, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: the International children’s accelerometry database (ICAD) International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2015;12(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanderloo LM, Tucker P, Johnson AM, Burke SM, Irwin JD. Environmental influences on Preschoolers' physical activity levels in various early-learning facilities. Research quarterly for exercise and sport. 2015;86(4):360–370. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2015.1053105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. 2020. [Accessed August 3rd, 2020]. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/

- 11.Elmesmari R, Martin A, Reilly JJ, Paton JY. Comparison of accelerometer measured levels of physical activity and sedentary time between obese and non-obese children and adolescents: a systematic review. BMC pediatrics. 2018;18(1):106. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1031-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health and Social Care. Physical activity guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers' report. 2019. [Accessed January 2020]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report .

- 13.Howells K, Sääkslahti A. Physical activity recommendations for early childhood: an international analysis of then different countries current national policies and practices for those under the age of 5. Physical Education in Early Childhood Education and Care: Researches-Best practices-Situation. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tremblay MS, Chaput JP, Adamo KB, et al. Canadian 24 hour movement guidelines for the early years (0– 4 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. BMC public health. 2017;17(5):1–32. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4859-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Utesch T, Bardid F. Motor competence. Dictionary of sport psychology: Sport, exercise, and performing arts. 2019;186 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Cliff DP, Barnett LM, Okely AD. Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents. Sports medicine. 2010;40(12):1019–1035. doi: 10.2165/11536850-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logan SW, Webster EK, Getchell N, Pfeiffer KA, Robinson LE. Relationship between fundamental motor skill competence and physical activity during childhood and adolescence: A systematic review. Kinesiology Review. 2015;4(4):416–426. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy LL, King L, Farrell L, Macniven R, Howlett S. Fundamental movement skills among Australian preschool children. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2010;13(5):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy LL, Reinten-Reynolds T, Espinel P, Zask A, Okely AD. Prevalence and correlates of low fundamental movement skill competency in children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):e390–e398. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]