Abstract

Background

Most people with bipolar disorder spend a significant percentage of their lifetime experiencing either subsyndromal depressive symptoms or major depressive episodes, which contribute greatly to the high levels of disability and mortality associated with the disorder. Despite the importance of bipolar depression, there are only a small number of recognised treatment options available. Consecutive treatment failures can quickly exhaust these options leading to treatment-resistant bipolar depression (TRBD). Remarkably few studies have evaluated TRBD and those available lack a comprehensive definition of multi-therapyresistant bipolar depression (MTRBD).

Aims

To reach consensus regarding threshold definitions criteria for TRBD and MTRBD.

Method

Based on the evidence of standard treatments available in the latest bipolar disorder treatment guidelines, TRBD and MTRBD criteria were agreed by a representative panel of bipolar disorder experts using a modified Delphi method.

Results

TRBD criteria in bipolar depression was defined as failure to reach sustained symptomatic remission for 8 consecutive weeks after two different treatment trials, at adequate therapeutic doses, with at least two recommended monotherapy treatments or at least one monotherapy treatment and another combination treatment. MTRBD included the same initial definition as TRBD, with the addition of failure of at least one trial with an antidepressant, a psychological treatment and a course of electroconvulsive therapy.

Conclusions

The proposed TRBD and MTRBD criteria may provide an important signpost to help clinicians, researchers and stakeholders in judging how and when to consider new non-standard treatments. However, some challenging diagnostic and therapeutic issues were identified in the consensus process that need further evaluation and research.

Keywords: Treatment resistant, bipolar disorder, depression, definition, consensus.

The treatment of depressive episodes experienced by people with bipolar disorder is one of the most challenging issues faced by both clinicians and researchers. Most people with bipolar disorder spend a significant percentage of their time experiencing either sub-syndromal depressive symptoms or major depressive episodes and these contribute to the high levels of distress, global disability and mortality associated with the disorder.1,2 There are only a small number of licensed therapeutic options available for the treatment of bipolar depression, and these often fail to significantly improve patients’ symptoms and functionality.3 Consecutive treatment failures can rapidly exhaust all recommended treatment options. It has been suggested that treatment failure rates might be even higher than in major depressive disorder (MDD).4 Despite this, there are remarkably few studies which have specifically evaluated treatment-resistant bipolar depression (TRBD) and those available lack a common definition of TRBD which makes it difficult to generalise their results.3,5,6

Fortunately, during the past decade, new promising non-standard treatment options have become available, but they are either not currently included in guidelines or are recommended for use only by specialist services. These emerging treatments have a limited evidence base to support their general use and some are associated with significant risks, costs and invasiveness in comparison with standard treatments. More importantly, as there is no clear consensus on the criteria defining TRBD, it is difficult to know at which point of the treatment pathway these non-standard interventions might be considered. The few TRBD definitions proposed so far vary, and most only consider pharmacological options independently of more comprehensive and standardised treatment including psychotherapy, physical therapies and lifestyle modification.7–9 We have recently published multi-therapy-resistance criteria in MDD as a guide to when clinicians could consider the use of non-standard treatments.10 Adopting a similar approach, we first set out to reach a consensus for criteria defining TRBD mainly based on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) bipolar disorder treatment guidelines.11,12 The main aim of this study was to reach an agreement about the concept and definition of multi-therapy-resistant bipolar depression (MTRBD), encompassing pharmacological treatments as well as psychological and physical treatments. The purpose of developing MTRBD criteria was to define a point in the bipolar depression treatment pathway when clinicians may wish to consider the use of non-standard treatments, rather than provide specific treatment recommendations.

Method

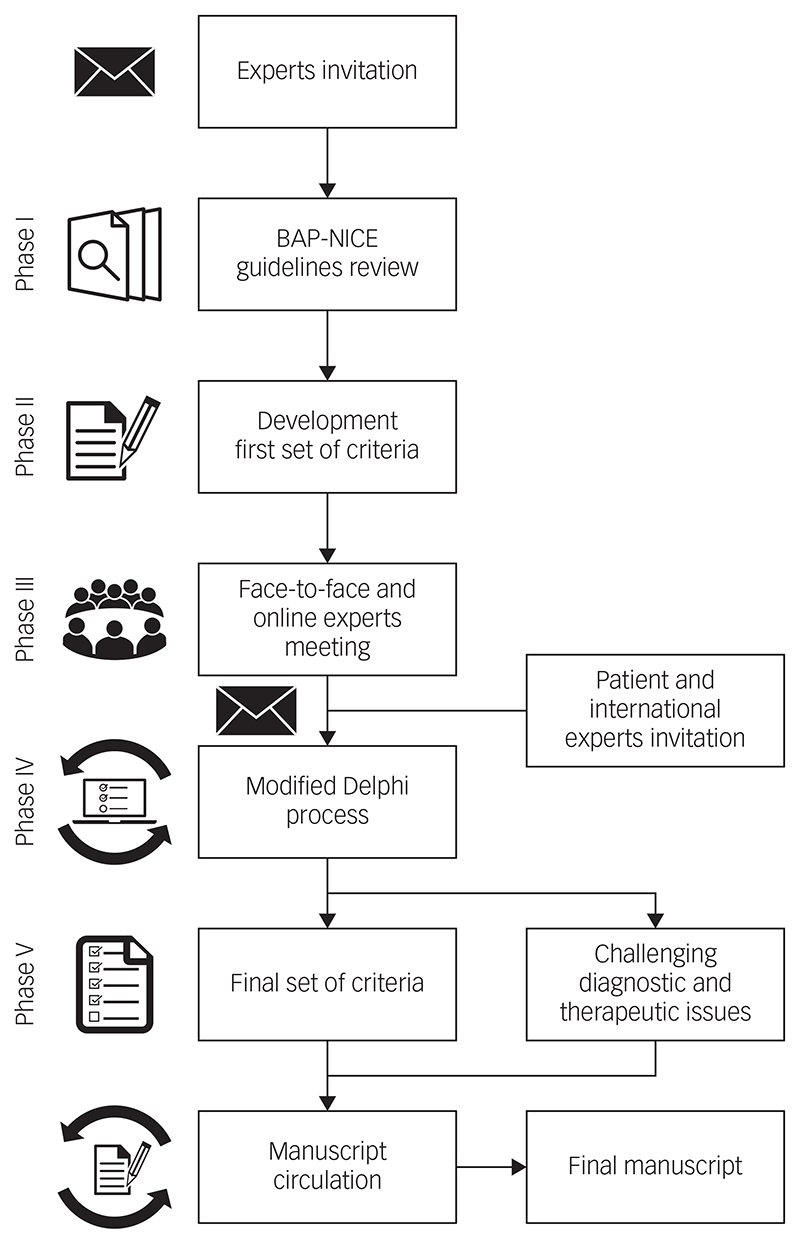

The development of the criteria definitions followed five successive phases (Fig. 1). Initially, a group of UK experts representing all major specialist centres and relevant domains of expertise were approached and all consented to participate. The initial consensus panel was composed of 18 bipolar disorder experts from primary, secondary and tertiary care. Two members of the panel (A.H.Y., P.R.A.S.) and a facilitator (D.H.-M.) developed a first set of TRBD and MTRBD criteria based on the latest NICE and BAP treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder that were among the most updated treatment guidelines at the time this project started.11,12 These criteria were reviewed and discussed during an initial face-to-face and online meeting sponsored by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (in London, March 2018), and challenging issues highlighted were noted while drawing up the initial draft criteria.

Fig. 1. The process and phases to reach consensus on treatmentresistant bipolar depression–multi-therapy-resistant bipolar depression criteria.

BAP, British Association of Psychopharmacology;11 NICE, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.12

The meeting participants decided that both TRBD and MTRBD criteria were needed to cover the whole trajectory and range of possibilities in the course of treating bipolar depression. To ensure that the criteria were as consistent and practical as possible, it was agreed that TRBD criteria should be embedded as the initial pharmacological treatment stage of the more comprehensive MTRBD criteria as a natural continuum of clinical practice.

Feedback and discussion from the initial meeting was incorporated into a new second version of the draft criteria. This, and unresolved diagnostic and therapeutic issues, were then rated for their relevance to be included in the criteria and this manuscript through a modified Delphi method.13,14 To ensure criteria generalisability, during the Delphi process, seven non-UK bipolar disorder experts from key representative international societies (the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, International Society for Affective Disorders, International Society for Bipolar Disorders, World Federation of the Societies of Biological Psychiatry and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists) were invited to be part of the consensus panel. The international representatives invited were previously or currently involved in the development of treatment guidelines in their respective societies, which are among the leading evidence-based international treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder.

Additionally, in order to include the patient’s perspective in the consensus, an expert patient was also invited to anonymously join the Delphi process. An expert patient is a person who has the knowledge needed to play an active role in making shared decisions about their own healthcare and management of their chronic condition.15 All the international representatives and the expert patient contacted accepted the invitation to be involved in the process.

The modified Delphi method was conducted using an online survey collecting anonymous responses in three rounds. The items included in the surveys were organised in three sections: (a) statements about unresolved elements of the second draft TRBD and (b) MTRBD criteria as well as (c) statements about challenging diagnostic and treatment issues identified throughout the process. The participants rated the surveys items ranging from ‘essential’, ‘important’, ‘don’t know/depends’, to ‘unimportant’ or ‘should not be included’.

The first survey round also allowed participants to add comments after rating each item that could include suggestions about other pertinent references, studies or treatment guidelines. In each round, the expert patient was offered additional information and support to understand and respond appropriately to each item according to their own judgement. After reading and analysing the comments provided by the participants, three of the authors (A.H.Y., P.R.A.S. and D.H.-M.), determined if they contained new information that merited the addition of a new item in subsequent Delphi rounds.

Survey items were classified as endorsed, re-rated or rejected. Endorsement cut-off was set to at least 80% of answers rating an item as essential or important. Items rated as essential or important by 65% to 79.9% of the participants were included in the subsequent rounds for re-rating. These cut-off criteria have also been used by similar expert consensus using the Delphi method in the field.14,16 Participants could decide whether they wanted to maintain or change their previous rating on these re-rated items only once; if items did not achieve the threshold for endorsement or re-rate, they were rejected. After each round, all the aggregated results were sent to the participants. Items requiring re-rating after the third round are outlined in the Discussion section.

Results

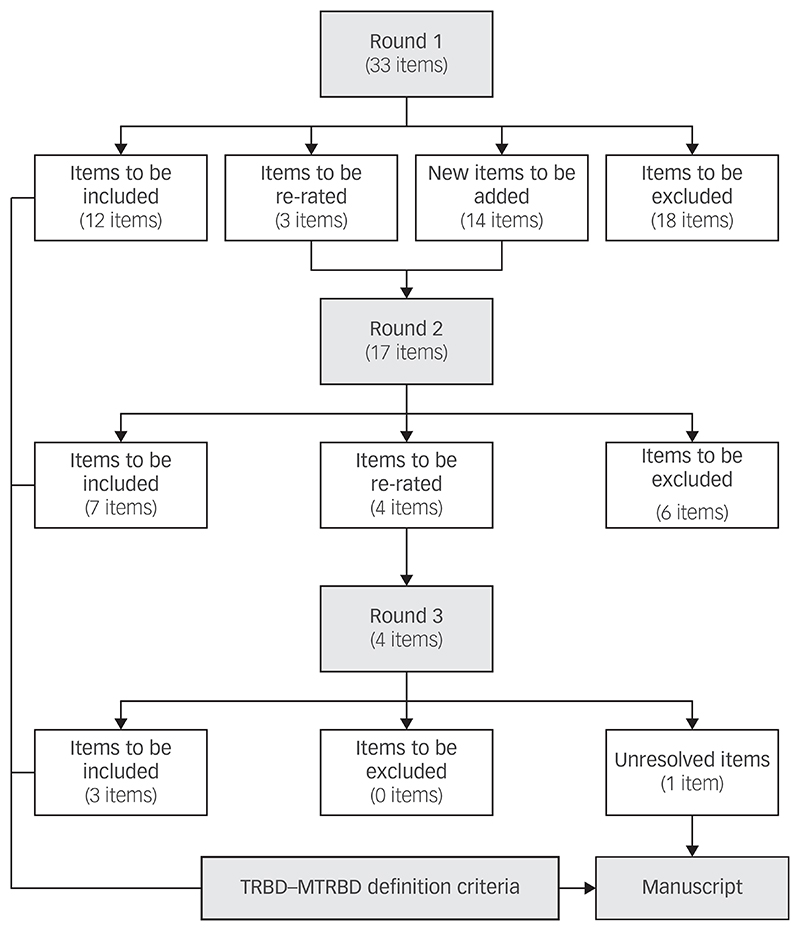

The initial survey included 33 items (Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.257), and the second survey included 17 items of which 3 were items needing re-rating and 14 were new items extracted from the comments left by the experts in the first round.

All the participants completed the first round of the Delphi survey whereas the second and third round were completed by 92.3% (24/26) and 88.5% (23/26) of the panel, respectively. In the second round, seven items were endorsed by the experts, six items were excluded and four remained unresolved diagnostic and therapeutic issues that required re-rating. In the final round, three out of the four items were endorsed and one item remained unresolved. In total, 15 out of the original 33 items were endorsed and included in the final criteria (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Results of the modified Delphi method rounds.

TRBD, treatment-resistant bipolar depression; MTRBD, multi-therapy-resistant bipolar depression.

The final consensus reached on the criteria for TRBD and MTRBD are detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Criteria for treatment-resistant bipolar depression in adults.

| Criteria | |

|---|---|

A patient diagnosed with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder according to DSM-5 criteria who currently fulfil criteria for a current moderate or severe major depressive episode AND who failed to reach sustained symptomatic remission at least for 8 consecutive weeks or did not tolerate two different trials at adequate therapeutic doses during 8 weeks either with:

|

|

| A | |

| B |

|

Combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine (OFC) and medications listed in Box B not supported by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder.11,12

Combination of lamotrigine and valproate not supported by NICE and BAP treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder.11,12 If used, monitor side-effects and/or levels closely.

Contraindicated in female patients of childbearing potential unless conditions of pregnancy prevention programme are met.17

Table 2. Criteria for multi-therapy-resistant bipolar depression in adults.

| A patient diagnosed with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder according to DSM-5 criteria who currently fulfil criteria for a current moderate or severe major depressive episode AND who failed to reach sustained symptomatic remission at least for 8 consecutive weeks or did not tolerate treatments described in points 1, 2, 3 and 4 | |||

| Pharmacological | 1. Two different treatment trials, at adequate therapeutic doses during 8 weeks, either with at least two treatments in monotherapy listed in Box A OR at least one treatment in monotherapy listed in Box A AND one treatment in Box A in combination with one different treatment in Box B | A | |

| B |

|

||

| AND | |||

|

|||

| AND | |||

| Psychological |

|

||

| AND | |||

| Non-pharmacological medical |

|

||

SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs, Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Combination ofolanzapine and fluoxetine (OFC) and medications listed in Box B not supported by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder.11,12

Combination of lamotrigine and valproate not supported by NICE and BAP treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder.11,12 If used, monitor side-effects and/or levels closely.

Contraindicated in female patients of childbearing potential unless conditions of pregnancy prevention programme are met.17

Discussion

In this study, we reached consensus definitions for both TRBD and MTRBD. We hope that these criteria will be a useful guide for clinicians when they are considering the use of non-standard treatment options and for researchers as a framework to guide future studies.

It is important to note that these are not the first proposed definitions for treatment resistance in bipolar depression. Many previous definitions are based on commonalities in the clinical presentation and treatment of bipolar depression and MDD.3,5,7,9 Most of these criteria include one or two failures to respond to treatments or reach remission to either mood stabilisers and/or antidepressants at adequate doses after between 6 and 8 weeks. However, over the past 10 years, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated marked differences in treatment efficacy of a range of treatments, for example selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) antidepressants, between bipolar disorder and MDD,18 and several studies have shown the useful role of quetiapine and lurasidone for the treatment of bipolar depression.19

In this context, Pacchiarotti et al previously provided a stepwise series of definitions for treatment refractoriness in bipolar depression ranging from treatment-resistant to involutional bipolar.7 The first step of this definition for bipolar I depression defined treatment resistance as a failure to reach remission with adequate plasma levels of lithium (0.8 mEq/L) or to other adequate ongoing mood-stabilising treatment, plus lamotrigine (50–200 mg/day) or with a full dose (≥600 mg/day) of quetiapine as monotherapy (300–600 mg/day allowed for bipolar II depression).7 An adequate trial period to reach remission was defined as 8 weeks as in our criteria. Our criteria contain similar options to those of Pacchiarotti et al, but more explicitly allow for combination therapy and do not require a minimum dose of 600 mg quetiapine for bipolar I depression.

Since the Pacchiarotti et al criteria, new emerging evidence and consensus have been published, especially regarding the use of anti-depressants, as well as other standard treatments (i.e. lurasidone).5,16 As a result, guidelines have been updated accordingly and these changes have been reflected in our version of the TRBD definition criteria. In comparison with previous proposed criteria, our MTRBD criteria were developed with a more pragmatic approach but within the initial evidence framework of the latest NICE and BAP guidelines.11,12

TRBD criteria

The agreed TRBD criteria includes failure to reach sustained remission or tolerate at least two different adequate treatment trials, for at least 8 weeks at therapeutic doses with acceptable adherence, of monotherapy (quetiapine, lurasidone, lamotrigine or olanzapine/ fluoxetine combination), or at least one of these as monotherapy and one of these in combination with lamotrigine, valproate or lithium. These criteria were mostly based on NICE and BAP bipolar depression guidelines.

The number of required failed trials was a matter of discussion that required a Delphi round to reach agreement. There were concerns that only two trials was a low threshold to consider further treatments, whereas on the other hand increasing the number of required treatment trials would extend the time that the patient remains symptomatic and inhibit access to other potential beneficial treatments. Treatment refractoriness was set as intolerance to treatment or failure to reach symptomatic sustained remission after at least 8 consecutive weeks with each trial.20 For lamotrigine monotherapy, this could be considered as 8 consecutive weeks at a stable therapeutic dose after an initial dose titration of about 6 to 8 weeks. However, the length of this particular trial alongside the controversial evidence around its efficacy as monotherapy requires a thoughtful consideration before starting it, balancing patients’ symptoms severity and preferences.21

The possibility of patient’s refusal of at least one of the trials was considered in the Delphi process, but was ultimately rejected because of the very low threshold for the definition and operational uncertainty of standardising valid reasons for refusal. Other aspects confirmed by the first Delphi round included the minimum dose of quetiapine and minimum lithium plasma levels. In both cases, the panel endorsed the minimum effective dose of 300 mg/day for quetiapine and plasma levels of 0.8 mEQ/L for lithium.

In the second round, despite some debate around the issue, the panel decided to keep the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine (OFC) as a treatment option, rather than a more generic second-generation antipsychotic and antidepressant combination. This takes into account that OFC is a licensed combination in the USA for this indication. Although only OFC is included in our criteria, we have no reason to believe that other second-generation antipsychotic and SSRIs combinations would not be effective for the treatment of bipolar depression; nevertheless, it should be noted that such other combinations have not yet been examined in clinical trials. These points are also consistent with other recent international bipolar disorder treatment guidelines.22 An additional point that was endorsed by the panel was the safety and inefficacy warning about a lamotrigine and valproate combination. This combination is not supported by the guidelines and, if used, plasma levels and side-effects should be closely monitored.

There were some suggestions for adding other agents among the initial pharmacological options which, after reviewing the body of evidence provide by the treatment guidelines adopted for this study,11,12 as well as experts opinions during the Delphi process, were ultimately rejected. They are listed in supplementary Table 1. Finally, the panel agreed that these criteria should apply to both working age and older adults diagnosed with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder.

MTRBD criteria

The MTRBD criteria extends the TRBD criteria by specifying: a trial of bupropion, or a selective SSRI, or a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) for at least 8 weeks at therapeutic doses, in combination with an antimanic drug in patients with bipolar I disorder, and carefully monitored in both patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorder; a course of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT); and a trial of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (except in the case of contraindications, intolerance or patient refusal).

The main points of controversy during the initial discussion and the Delphi process were the types of antidepressants and psychological treatments to include in the MTRBD criteria.

Even though prior consensus statements about the use of antidepressant monotherapy for bipolar depression discouraged their use, antidepressants are still widely used for the treatment of bipolar depression worldwide.16,23 It has been suggested that the risk of switch to mania should be balanced and considered on a case-by-case basis rather than recommending a broad restriction, especially in the particular circumstances of TRBD in which options are limited.24 In this context, it was initially proposed that antidepressants should be avoided in patients with either a previous history of rapid cycling, mixed episodes or manic/hypomanic switches or current mixed symptoms and agitation. However, the panel did not endorse this as a general rule, but the evidence available in guidelines and several comments of the panel emphasised that special care should be taken when antidepressants are used for the treatment of bipolar depression.11,12

In line with this, the panel agreed that if antidepressants are prescribed in bipolar I depression, they should only be used adjunctively with an antimanic drug,25 whereas in bipolar II depression, monotherapy with antidepressants is acceptable. All patients with bipolar depression treated with antidepressants should be warned about risk of switch to hypomanic or manic symptoms and should be careful monitored for the emergence of such symptoms.

The other area where consensus proved harder concerned which classes of antidepressants should be considered for the treatment of bipolar depression. The general agreement among panel members was to be as pragmatic as possible and not to limit the already few options available while balancing the benefit and risks. As a result, SSRIs, SNRIs and bupropion were endorsed by the panel in the final Delphi round.

The other widely debated area for the MTRBD criteria was the inclusion of psychological interventions in the treatment process. This is mainly because of the limited evidence on which guidelines recommend these interventions for bipolar depression.26 The panel agreed that psychological treatments, in general, should be included in the criteria, but because of the lack of evidence of efficacy for bipolar depression, only CBT was endorsed in the last round as a potentially useful approach, in particular its behavioural activation component.

The inclusion of a structured psychoeducation programme among the psychological treatments was the only unresolved item not reaching endorsement or rejection rates after the three rounds in the Delphi process. Although the effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention to prevent relapses has been extensively demonstrated, the evidence is not robust enough for the treatment of acute episodes.26 Nonetheless, and depending on the functional and cognitive status of each individual patient who has not received this intervention previously, general or brief psychoeducational interventions might be considered as an option, especially taking into account the long time required to complete the whole treatment trajectory proposed in MTRBD criteria and long-term relapse prevention after the episode has been resolved.

Finally, at least 12 bilateral sessions of ECT was the last therapeutic option included in the MTRBD criteria, provided there were no contraindications and it was accepted and tolerated by the patient. Otherwise, it was agreed during the panel discussions that this should be considered a failed trial, and thus, the criteria for MTRBD would have been fulfilled.

During the panel discussions a number of diagnostic and therapeutic considerations emerged, which are outlined below.

Diagnostic considerations

Although most treatment guidelines provide recommendations for the management of bipolar depression, they provide less clarity about how to address treatment resistance. In reflecting on this, the panel provided some theoretical and practical considerations that could be drawn from standard clinical practice and guidelines.

The first of these is the need to ensure that for people with TRBD or MTRBD a comprehensive medical evaluation is conducted. It is important that clinicians exclude primary organic or pharmacological causes for a depressive episode in bipolar disorder. This should include a medical screening comprising a complete physical examination, blood screening and imaging tests when appropriate. Additionally, any already existing organic comorbidities and treatment side-effects should be reassessed to exclude triggering or contributing factors. Abnormal test results or comorbid conditions should be evaluated and if necessary treated by a specialist as appropriate.27

Second, given the high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric conditions in bipolar disorder, the assessment of psychiatric comorbidities, particularly substance use, personality and anxiety disorders, is critical in the treatment of TRBD and MTRBD as they have been shown to have a negative impact on treatment outcomes.28–30 In this context, even if the patient is already well-known to the clinician, semi-structured interviews may be helpful to assist diagnostic comorbidity assessments.31 The co-occurrence of one or more psychiatric comorbidities requires a full assessment of its severity and specific evidencebased pharmacological and psychological treatments in coordination with professionals with expertise in these conditions, if available. Potential depressogenic agents should be avoided in the treatment of comorbid conditions, if possible.32 However, since comorbid conditions are exclusion criteria in most bipolar disorder clinical trials, there is little evidence regarding the efficacy of commonly used treatments for these patients.

Finally, the panel considered that it was important to emphasise the need to employ a systematic and consistent method to assess the severity of the depressive symptoms, quality of life and functionality with standardised scales used throughout the treatment pathway, particularly before and after starting new treatments.33 This should include continuous and rigorous medication adherence and risk assessment, including for psychotic symptoms and suicidality, as standards of clinical practice.11,12

Therapeutic considerations

General health and exercise

Current guidelines recommend a healthy diet, smoking cessation and regular exercise alongside pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, with appropriate interventions where possible.11,12,34,35 Diet, smoking cessation and exercise may benefit physical comorbidities, the metabolic risk factors associated with the use of some pharmacotherapies and may augment other therapies. However, we could not define diet or exercise ‘treatment resistance’ in TRBD or MTRBD because of the limited and heterogeneous evidence base.

Mixed states, psychotic and suicidal symptoms

Even though controversies still exist around the DSM-536 criteria for bipolar disorder with mixed features, the prevalence of mixed features using these criteria has been reported to be as high as one-third of patients with bipolar disorder with a depressive episode.37 Hence, we would suggest that screening for mixed features should be a priority during the evaluation of depressive symptoms. However, the evidence base for the treatment of mixed states is even more limited than for bipolar depression and there are no treatments currently approved by the European Medicines Agency or US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of bipolar depression with mixed features.

In general terms, BAP and NICE as well as other international guidelines such as Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments22 and World Federation of the Societies of Biological Psychiatry38 discourage the use of antidepressant treatments in these circumstances. Second-generation antipsychotics, lithium, valproate and lamotrigine have been evaluated for the treatment of depression with mixed features but not all have demonstrated efficacy in bipolar depression and most evidence is extrapolated from unipolar depression. Among them, a recent review of international guidelines reported that lurasidone and ziprasidone may be useful in treating acute mixed depression, valproate may be useful in the prevention of new mixed episodes, and lithium and quetiapine may be useful in preventing affective episodes of all polarities.39 ECT might also deserve a special consideration when mixed features are present.11

Suicide and self-harm

Following recommendations of existing guidelines and practice standards, the presence of suicidal symptoms mandates an ongoing risk evaluation to determine the most appropriate setting in which to continue the treatment. In these cases, a written risk assessment, safety plan and coping strategies must be discussed with the patient. Lithium should be considered as one of the first treatment options in these situations given its evidence in preventing suicide in the long-term treatment of individuals with bipolar disorder.40 When psychotic or suicidal symptoms are present and persistent, a re-evaluation of treatment needs to consider the option of more invasive approaches such as ECT.41

Treatment across the lifespan

The available literature for the treatment for bipolar depression in the perinatal period is generally limited, which is reflected in the limited information provided in treatment guidelines. Most of the recommendations available come from retrospective reports and/or case studies.42,43 However, in female patients of childbearing age with a potential mental health condition, general principles should be considered in those fulfilling criteria for TRBD–MTRBD according to existing guidelines. In this group, we would like to highlight that the use of sodium valproate is contraindicated in all female patients of childbearing potential unless conditions of a pregnancy prevention programme are met as is detailed in the TRBD–MTRBD criteria.17,44

The panel agreed in the second round of the consensus process that TRBD–MTRBD criteria should only be applied to working age and older adults and should not be applied to children and adolescents. The main reason for this decision was that there is insufficient evidence in these age groups about the response to standard and non-standard treatments for bipolar depression and sometimes uncertainty about the bipolar diagnosis and its potential overlap with the symptoms of other conditions. However, NICE guidelines recommend following a similar pharmacological approach as for adults, stressing the importance of modifying drug treatments according to age and not routinely continuing antipsychotic treatment for longer than 12 weeks.12

Additionally, these guidelines recommend providing to these groups, either individual CBT or interpersonal psychotherapy for at least 3 months. Similarly, BAP guidelines recommend following the same pharmacological interventions as in working age adults but also suggest considering and balancing dosing and potential harms. Nonetheless, BAP treatment guidelines emphasise the scarce empirical evidence available to assume a direct extrapolation from adult treatments in these age groups and encourages an integrated treatment approach.11

There is also a dearth of studies and evidence-based clinical guidelines in older adults. As a result of the increased rates of organic comorbidities in this population as well as the reduced hepatic and renal clearance, to avoid adverse effects, special caution should be taken titrating and adjusting doses as is recommended in existing guidelines.11,12,45

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study in which both TRBD and the new concept of MTRBD criteria were agreed by a diverse but highly qualified group of international experts, including a patient expert, using a systematic Delphi consensus process. Our initial TRBD and MTRBD criteria were also based on two of the most updated and highest quality ones among bipolar disorder treatment guidelines at the time this project started (November 2017). In comparison with previous definition proposals, our MTRBD consensus criteria were developed with a pragmatic approach considering the whole bipolar depression illness trajectory within the existing evidence-based pharmacological treatments while also taking into account non-pharmacological options. As a result, the criteria are well supported by standardised guidelines and are highly applicable to real-world clinical practice. However, for the same reasons, the criteria may be affected by the limitations and biases of the evidence contained within current guidelines. This also limits the generalisation of these criteria to other regions of the world where treatments included in the criteria might not be available. However, although the initial starting criteria were limited to the British guidelines, all panel members could suggest other evidence-based treatment options from different treatment guidelines or studies throughout the consensus process.

Currently, there is very limited evidence to guide the management of TRBD. The evidence that does exist comes from remarkably few randomised controlled trials and also open studies, case series and reports. Furthermore, the lack of a common TRBD definition used in this research limits the generalisability of their results. This is potentially one reason why treatment assumptions based on data extrapolated from the treatment of unipolar depressive episodes continue to exist.3,5,9

There are some obvious limitations inherent to the Delphi method and how we implemented it. First, the initial set of TRBD and MTRBD criteria were previously developed and discussed by a panel of experts comprising three-quarters of the whole final Delphi participants, leaving the remaining members of the panel with fewer possibilities to modify the initial criteria or raise further points. However, the first round of the Delphi survey included the possibility to add further comments to each item to be considered during subsequent rounds.

Second, there is also a potential lack of heterogeneity in an expert panel from a specific field that could lead to shared bias in the area. To balance for this, the initial panel was not limited to secondary and tertiary care participants but also included a primary care expert. Additionally, to minimise regional biases and increase the chances of generalisability, the participation in the process of international representatives from leading professional societies and an expert patient could be considered strengths of this study to overcome the above-mentioned issues.

Finally, it is important to emphasise that the proposed TRBD and MTRBD criteria does not imply treatment recommendations that clinicians should follow for therapeutic refractoriness in bipolar disorder. The rationale for our suggested criteria is to help clinicians, researchers and other stakeholders in determining when non-standards treatment options could be considered. An overview of the current non-standard treatments available for MDD, which might also be extrapolated to bipolar depression, is available in our recently published work about the definition of multiple-therapy-resistant MDD.10

Implications

These consensus criteria should be considered as a complement to clinical expertise, as well as to the resources available and the particular clinical characteristics and preferences of every single person experiencing bipolar depression. We hope the MTRBD criteria will guide clinicians, researchers and stakeholders in deciding when to consider the use of novel pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for resistant bipolar depression in the treatment pathway. Among the unresolved diagnostic and therapeutic issues, the utility of different antidepressants classes and psychological interventions for the treatment of bipolar depression remain as pressing questions urgently needing further research.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.257.

Acknowledgements

We thank the expert patient who participated as an anonymous member of the Delphi panel to reach the consensus about TRBD–MTRBD criteria. The authors also want to express their gratitude to Ms Caroline Loveland for her help with the consensus rounds invitations.

Funding

This study was funded by a Small Project Fund grant from the General Adult Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. This report represents independent work in part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centres at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Oxford Cognitive Health Clinical Research Facility. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. R.M. is funded by Nottingham NIHR Biomedical Centre, NIHR MindTech MTC and NIHR CLAHRC East Midlands.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

In the past 3 years, M.B. has received grant/research support from the NIH, Cooperative Research Centre, Simons Autism Foundation, Cancer Council of Victoria, Stanley Medical Research Foundation, MBF, NHMRC, Beyond Blue, Rotary Health, Geelong Medical Research Foundation, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Glaxo SmithKline, Meat and Livestock Board, Organon, Novartis, Mayne Pharma, Servier, Woolworths, Avant and the Harry Windsor Foundation, has been a speaker for Astra Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Glaxo SmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, Sanofi Synthelabo, Servier, Solvay and Wyeth and served as a consultant to Allergan, Astra Zeneca, Bioadvantex, Bionomics, Collaborative Medicinal Development, Eli Lilly, Grunbiotics, Glaxo SmithKline, Janssen Cilag, LivaNova, Lundbeck, Merck, Mylan, Otsuka, Pfizer and Servier. A.J.C. has in the past 3 years received honoraria for speaking from Astra Zeneca and Lundbeck, honoraria for consulting from Allergan, Janssen, Lundbeck and LivaNova and research grant support from Lundbeck.* G.M.G. holds shares in P1Vital and has served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for Allergan, Angelini, Compass pathways, MSD, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Takeda, Medscape, Minervra, P1Vital, Pfizer, Servier, Shire and Sun Pharma. J.G. has received research funding from National Institute for Health Research, Medical Research Council, Stanley Medical Research Institute and Wellcome. H.G. received grants/research support, consulting fees or honoraria from Gedeon Richter, Genericon, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer and Servier. R.H.M.-W. has received support for research, expenses to attend conferences and fees for lecturing and consultancy work (including attending advisory boards) from various pharmaceutical companies including Astra Zeneca, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Liva Nova, Lundbeck, MyTomorrows, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, SPIMACO and Sunovion. R.M. has received research support from Big White Wall, Electromedical Products, Johnson and Johnson, Magstim and P1Vital. S.N. received honoraria from Lundbeck, Jensen and Otsuka. J.C.S. has received funds for research from Alkermes, Pfizer, Allergan, J&J, BMS and been a speaker or consultant for Astellas, Abbott, Sunovion, Sanofi. S.W has, within the past 3 years, attended advisory boards for Sunovion and LivaNova and has undertaken paid lectures for Lundbeck. D.J.S. has received honoraria from Lundbeck. T.S. has reported grants from Pathway Genomics, Stanley Medical Research Institute and Palo Alto Health Sciences; consulting fees from Sunovion Pharamaceuticals Inc.; honoraria from Medscape Education, Global Medical Education and CMEology; and royalties from Jones and Bartlett, UpToDate and Hogrefe Publishing. S.P. has served as a consultant or speaker for Janssen, and Sunovion. P.T. has received consultancy fees as an advisory board member from the following companies: Galen Limited, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Europe Ltd, myTomorrows and LivaNova. E.V. received grants/ research support, consulting fees or honoraria from Abbott, AB-Biotics, Allergan, Angelini, Dainippon Sumitomo, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Sunovion. L.N.Y. has received grants/research support, consulting fees or honoraria from Allergan, Alkermes, Dainippon Sumitomo, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sanofi, Servier, Sunovion, Teva and Valeant. A.H.Y. has undertaken paid lectures and advisory boards for all major pharmaceutical companies with drugs used in affective and related disorders and LivaNova. He has also previously received funding for investigator-initiated studies from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck and Wyeth. P.R.A.S. has received research funding support from Corcept Therapeutics Inc. Corcept Therapeutics Inc fully funded attendance at their internal conference in California USA and all related expenses. He has received grant funding from the Medical Research Council UK for a collaborative study with Janssen Research and Development LLC. Janssen Research and Development LLC are providing non-financial contributions to support this study. P.R.A.S. has received a presentation fee from Indivior and an advisory board fee from LivaNova.

The original version of this article stated incorrectly that A.C. had received fees for lecturing from the pharmaceutical companies Lundbeck and Sunovion. This was an accidental duplication of the declaration of interest by A.J.C. which immediately follows it. A.C. declares no conflict of interest. This article has been updated and a corrigendum published.

Contributor Information

Diego Hidalgo-Mazzei, Centre for Affective Disorders, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, UK;and Consultant Psychiatrist, Bipolar Disorders Programme, Departmentof Psychiatry and Psychology, Institute of Neurosciences, Hospital Clinic de Barcelona, CIBERSAM, IDIBAPS, Spain.

Michael Berk, Alfred Deakin Professor of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Deakin University and Barwon Health; Director, IMPACT Strategic Research Centre (Innovation in Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Treatment); Professorial Research Fellow, The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health; Professorial Research Fellow, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health; and Professorial Research Fellow, Department of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne, Australia.

Andrea Cipriani, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Warneford Hospital; and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Anthony J. Cleare, Psychopharmacology and Affective Disorders, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London; and Consultant Psychiatrist, Maudsley Hospital, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), UK.

Arianna Di Florio, Division of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences, MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Cardiff University, UK.

Daniel Dietch, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, UK.

John R. Geddes, Senior Investigator, Epidemiological Psychiatry, University of Oxford and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Guy M. Goodwin, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Warneford Hospital, UK.

Heinz Grunze, Head of Department of Adult Psychiatry, Klinikum am Weissenhof, Weinsberg & Paracelsus Medical University, Germany.

Joseph F. Hayes, UCLH NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Division of Psychiatry, University College London; and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist, Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Ian Jones, National Centre for Mental Health, MRC Centre for NeuropsychiatricGeneticsand Genomics, CardiffUniversity, UK.

Siegfried Kasper, Psychiatry and Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical University Vienna, MUV, AKH, Währinger Gürtel, Austria.

Karine Macritchie, Lead Consultant Psychiatrist, OPTIMA Mood Disorders Service, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), UK.

R. Hamish McAllister-Williams, Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University; and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist, Regional Affective Disorders Service, Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Richard Morriss, Psychiatry and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist, Centre for Mood Disorders, Institute of Mental Health, University of Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Sam Nayrouz, Consultant Psychiatrist and Director of Clinical Studies, West London Mental NHS HealthTrust; and HonorarySenior Lecturer, Imperial College School of Medicine, UK.

Sofia Pappa, Consultant Psychiatrist and Research Lead, West London Mental Health Trust; NW London Specialty Lead in Mental Health, National Institute for Health Research; and Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer, Imperial College London, UK.

Jair C. Soares, Center of Excellence on Mood Disorders, DepartmentofPsychiatryand Behavioral Sciences,McGovern Medical School; and Executive Director, The University ofTexas Harris County Psychiatric Center, USA.

Daniel J. Smith, Psychiatry and Lister Institute Prize Fellow, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, Mental Health, University of Glasgow, Gartnavel Royal Hospital, UK.

Trisha Suppes, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine; Director, VA Palo Alto Bipolar and Depression Research Program; and Director, VA Palo Alto CSP NODES, Palo Alto, USA.

Peter Talbot, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry, University of Manchester; and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist and Director, Specialist Service for Affective Disorders, Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Eduard Vieta, Head of Department and Professor of Psychiatry, Bipolar disorders programme, Departmentof Psychiatry and Psychology, Institute of Neurosciences, Hospital Clinic, University of Barcelona, CIBERSAM, IDIBAPS, Spain.

Stuart Watson, Clinical Senior Lecturer and Consultant Psychiatrist, Northern Centre for Mood Disorders, Institute for Neuroscience, Newcastle University and Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Lakshmi N. Yatham, University of British Columbia; Regional Head, Department of Psychiatry, Vancouver Coastal Health/Providence Healthcare; and Regional Program Medical Director, Vancouver Coastal Health/ Providence Healthcare, Canada.

Allan H. Young, Chair of Mood Disorders and Director of the Centre for Affective Disorders, Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM); Academic Director, Psychological Medicine and Integrated Care Clinical Academic Group; and NIHR Senior Investigator, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, South London and Maudsley NHS FoundationTrust(SLaM), UK.

Paul R. A. Stokes, National Affective Disorders Service; Academic PsychiatryTraining Programme Lead, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, South London and MaudsleyNHS Foundation Trust (SLaM); and CRN South London Lead for Mental Health, Centre for Affective Disorders, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), UK.

References

- 1.Kupka RW, Altshuler LL, Nolen WA, Suppes T, Luckenbaugh DA, Leverich GS, et al. Three times more days depressed than manic or hypomanic in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:531–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post RM. The impact of bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(suppl 5):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tondo L, Vázquez GH, Baldessarini RJ. Options for pharmacological treatment of refractory bipolar depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:431. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0431-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C-T, Bai Y-M, Huang Y-L, Chen Y-S, Chen T-J, Cheng J-Y, et al. Association between antidepressant resistance in unipolar depression and subsequent bipolar disorder: cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:45–51. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sienaert P, Lambrichts L, Dols A, De Fruyt J. Evidence-based treatment strategies for treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:61–9. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, Kraemer H, Rush AJ. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1164–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacchiarotti I, Mazzarini L, Colom F, Sanchez-Moreno J, Girardi P, Kotzalidis GD, et al. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: towards a new definition. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120:429–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachs GS. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:215–36. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poon SH, Sim K. Evidence-based pharmacological approaches for treatmentresistant bipolar disorder. Treat mood Disord. 2015:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAllister-Williams RH, Christmas DMB, Cleare AJ, Currie A, Gledhill J, Insole L, et al. Multiple-therapy-resistant major depressive disorder: a clinically important concept. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212:274–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2017.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, Aronson JK, Barnes TRH, Cipriani A, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:495–553. doi: 10.1177/0269881116636545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline 185. NICE; 2014. Bipolar Disorder: Assessment and Management. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalkey NC. The Delphi Method: An Experimental Study of Group Opinion. RAND Corporation; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorm AF. Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry. 2015;49:887–97. doi: 10.1177/0004867415600891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donaldson L. Expert patients usher in a new era of opportunity for the NHS. BMJ. 2003;326:1279–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7402.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, Nolen WA, Grunze H, Licht RW, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1249–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Valproate Medicines (Epilim ▼, Depakote ▼): Contraindicated in Women and Girls of Childbearing Potential Unless Conditions of Pregnancy Prevention Programme are Met. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; 2018. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/valproate-medicines-epilim-depakote-contraindi-cated-in-women-and-girls-of-childbearing-potential-unless-conditions-of-pregnancy-prevention-programme-are-met . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forty L, Smith D, Jones L, Jones I, Caesar S, Cooper C, et al. Clinical differences between bipolar and unipolar depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:388–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young AH, McElroy SL, Bauer M, Philips N, Chang W, Olausson B, et al. A doubleblind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine and lithium monotherapy in adults in the acute phase of bipolar depression (EMBOLDEN I) J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:150–62. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04995gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschfeld RM, Calabrese JR, Frye MA, Lavori PW, Sachs G, Thase ME, et al. Defining the clinical course of bipolar disorder: response, remission, relapse, recurrence, and roughening. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calabrese JR, Huffman RF, White RL, Edwards S, Thompson TR, Ascher JA, et al. Lamotrigine in the acute treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:323–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97–170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samalin L, Vieta E, Okasha TA, Uddin MJ, Ahmadi Abhari SA, Nacef F, et al. Management of bipolar disorder in the intercontinental region: an international, multicenter, non-interventional, cross-sectional study in real-life conditions. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25920. doi: 10.1038/srep25920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Vázquez G, Lepri B, Visioli C. Clinical responses to antidepressants among 1036 acutely depressed patients with bipolar or unipolar major affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:355–64. doi: 10.1111/acps.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGirr A, Vöhringer PA, Ghaemi SN, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Safety and efficacy of adjunctive second-generation antidepressant therapy with a mood stabiliser or an atypical antipsychotic in acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:1138–46. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Laws KR. NICE guidance on psychological treatments for bipolar disorder: searching for the evidence. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:386–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kemp DE, Gao K, Chan PK, Ganocy SJ, Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: relationship between illnesses of the endocrine/ metabolic system and treatment outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:404–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JH, Dunner DL. The effect of anxiety disorder comorbidity on treatment resistant bipolar disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:91–7. doi: 10.1002/da.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deckersbach T, Peters AT, Sylvia L, Urdahl A, Magalhães PVS, Otto MW, et al. Do comorbid anxiety disorders moderate the effects of psychotherapy for bipolar disorder? Results from STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:178–86. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swartz HA, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, Proietti JM, Scott J. Acute treatment outcomes in patients with bipolar I disorder and co-morbid borderline personality disorder receiving medication and psychotherapy. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:192–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimmerman M. A Review of 20 years of research on overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in the rhode Island methods to improve diagnostic assessment and services (MIDAS) project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:71–9. doi: 10.1177/0706743715625935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goikolea JM, Colom F, Torres I, Capapey J, Valentí M, Undurraga J, et al. Lower rate of depressive switch following antimanic treatment with second-generation antipsychotics versus haloperidol. J Affect Disord. 2013;144:191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, Bauer M, Miklowitz D, Wisniewski SR, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:1028–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper SJ, Reynolds GP, Barnes T, England E, Haddad P, Heald A, et al. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:717–48. doi: 10.1177/0269881116645254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-5) 5th. APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McIntyre RS, Soczynska JK, Cha DS, Woldeyohannes HO, Dale RS, Alsuwaidan MT, et al. The prevalence and illness characteristics of DSM-5-defined ‘mixed feature specifier’ in adults with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder: results from the International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, Bowden C, Licht RW, Azorin J-M, et al. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the Biological Treatment of Bipolar Disorders: acute and long-term treatment of mixed states in bipolar disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19:2–58. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2017.1384850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdolini N, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Samalin L, Young AH, et al. Mixed states in bipolar and major depressive disorders: systematic review and quality appraisal of guidelines. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138:196–222. doi: 10.1111/acps.12896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldberg JF, Allen MH, Miklowitz DA, Bowden CL, Endick CJ, Chessick CA, et al. suicidal ideation and pharmacotherapy among STEP-BD patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1534–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, Mathew SJ, Murrough JW, Feder A, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:150–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma V, Sharma S. Peripartum management of bipolar disorder: what do the latest guidelines recommend? Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17:335–44. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1243470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham RK, Tavella G, Parker GB. Is there consensus across international evidence-based guidelines for the psychotropic drug management of bipolar disorder during the perinatal period? J Affect Disord. 2018;228:216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health. NICE; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs115 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Falls in Older People: Assessing Risk and Prevention. NICE; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.