Abstract

The orchid genus Nigritella is closely related to Gymnadenia and has from time to time been merged with the latter. Although Nigritella is morphologically distinct, it has been suggested that the separating characters are easily modifiable and subject to rapid evolutionary change. So far, molecular phylogenetic studies have either given support for the inclusion of Nigritella in Gymnadenia, or for their separation as different genera. To resolve this issue, we analysed data obtained from Restriction-site associated DNA sequencing, RADseq, which provides a large number of SNPs distributed across the entire genome. To analyse samples of different ploidies, we take an analytical approach of building a reduced genomic reference based on de novo RADseq loci reconstructed from diploid accessions only, which we further use to map and call variants across both diploid and polyploid accessions. We found that Nigritella is distinct from Gymnadenia forming a well-supported separate clade, and that genetic diversity within Gymnadenia is high. Within Gymnadenia, taxa characterized by an ITS-E ribotype (G. conopsea s.str. (early flowering) and G. odoratissima), are divergent from taxa characterized by ITS-L ribotype (G. frivaldii, G. densiflora and late flowering G. conopsea). Gymnigritella runei is confirmed to have an allopolyploid origin from diploid Gymnadenia conopsea and tetraploid N. nigra ssp. nigra on the basis of RADseq data. Within Nigritella the aggregation of polyploid members into three clear-cut groups as suggested by allozyme and nuclear microsatellite data was further supported.

Keywords: Gymnadenia, Nigritella, Orchidaceae, phylogenomics, polyploidy, RADseq

1. Introduction

Orchids are often subject to intense taxonomic debate regarding generic delimitation and species circumscription (Bateman et al. 1997). On one hand their immense diversity summing up to 10% of angiosperm species may be challenging to grasp and catalogue and on the other hand their often complex pollination syndromes, opening opportunities for gene flow may blurr phenotypic and genetic patterns as inconclusive for taxon delimitation. Lastly, the flagship conservation efforts and their ornamental qualities make orchids particularly prone for subjective taxonomic opinions.

The two orchid taxa Gymnadenia R.Br. and Nigritella Rich. are easily separated in the field and are regarded by many authors as different genera based on morphological evidence (e.g., Moore 1980, Baumann et al. 2006). Members of Gymnadenia are characterized by an elongate, inflorescence with resupinate flowers carrying a thin, medium-sized to long spur, whereas Nigritella species have a short and dense head-like inflorescence, with flower colour polymorphism observed in some species, and non-resupinate flowers carrying a minute sac-like spur (Moore 1980, Baumann et al. 2006, Kellerberger et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the two genera are obviously related, with common features such as a deeply divided palmate-digitate tuber, narrow unspotted leaves, and similar morphologies of the column (Pridgeon et al. 2001; Claessens and Kleynen 2011). Since the columnar structure is emphasized in orchid classification, some orchid systematists have argued that the genera should be collapsed under Gymnadenia on the basis of this apomorphic morphological feature (Løjtnant 1977; Sundermann 1980).

Gymnadenia s. str. has a wide distribution in temperate-boreal Eurasia, where it is found in open grasslands in mountain regions, as well as lowland areas including semi-open woodlands. Nigritella is confined to mountain regions of Europe and is considered as one of the few orchid genera endemic to Europe (Gjærevoll 1992). They both produce nectar and are mainly pollinated by Lepidoptera (Vöth 2000; Claessens and Kleynen 2011), however, largely by different species (Vöth 2000; Claessens and Kleynen 2011).

Population genetic studies performed in Gymnadenia have previously found relatively high levels of diversity within populations, low levels of differentiation between populations, and usually moderate levels of inbreeding (Scacchi and De Angelis 1989; Soliva and Widmer 1999; Gustafsson 2000; Gustafsson and Sjögren-Gulve 2002; Gustafsson and Lönn 2003). Both genera include diploids with 2n=40 and polyploids with multiples of the base number x=20 (Moore 1980). Most species and populations of Gymnadenia are typically diploid, but in the mountains of Central Europe, populations of G. conopsea can be tetraploid or mixed diploid/tetraploid (Trávníček et al. 2012). Small numbers of individuals with odd ploidies can also be found. As far as known, polyploid Gymnadenia are sexual and outcrossing, as are the diploids.

Diploid members of Nigritella are sexual and predominantly outcrossing, with a high degree of genetic variation within and between populations (Teppner and Klein 1990; Hedrén et al. 2000, 2018). Polyploid members of Nigritella are all reproducing asexually by agamospermy (i.e., nucellar embryony; Teppner 1996, 2004) and they have been suggested to be allopolyploids (Hedrén et al. 2000). These taxa are less variable, but populations are still often multiclonal, and some clones can be regionally widespread and shared between populations (Hedrén et al. 2018). Most polyploid Nigritella are tetraploid, but there is also one triploid, and one pentaploid species (Teppner 2004).

Despite the significant difference in spur length and the resulting differential deposition of pollinaria on visiting insects, hybrids between members of Gymnadenia and Nigritella are rarely encountered. It is doubtful whether hybridization ever goes beyond primary hybrid formation (Gerbaud and Schmid 1999). However, one of the hybrids has inherited the capacity to reproduce by agamospermy from its Nigritella parent, and is recognized as a separate species, Gymnigritella runei (Teppner and Klein 1989).

Molecular studies have so far shown conflicting results or have been inconclusive on the exact relationships between Gymnadenia and Nigritella. Phylogenetic analyses of nuclear ITS sequences, which are highly variable spacer regions separating ribosomal genes in the tandemly repeated rDNA regions of the nuclear genome (Jorgensen and Cluster 1988), have given support to the argument that Nigritella should be included in Gymnadenia (Pridgeon et al. 1997, Bateman et al. 1997, Bateman et al. 2003, Bateman et al. 2006, Stark et al. 2011, Bateman et al. 2018). According to ITS phylogenies, the primary subdivision of the group results in one small clade comprising G. conopsea s.str. and G. odoratissma, and a second more species-rich and diverse clade containing other members of typical Gymnadenia including G. densiflora, G. borealis, G. frivaldii, the Asian G. orchidis and G. crassinervis, as well as a distinct subclade comprising all members of Nigritella. Thus, Nigritella appears as a monophyletic subgroup, but it is fully embedded within Gymnadenia. Emphasizing the monophyly criterion when circumscribing genera (Bateman 2009), all members of Nigritella should accordingly be recognized as Gymnadenia, when based on evidence from ITS sequences alone.

However, phylogenies presented in Inda et al. (2012), based on plastid rpl16 and mitochondrial coxI, suggest a sister group relationship between Nigritella and Gymnadenia s.str. Similarly, Bateman (2001) demonstrated a complete separation between the genera in the plastid trnL intron, and this difference was also confirmed in a more comprehensive study (Hedrén et al. 2018), which included several additional plastid marker loci. Moreover, the two genera were shown to be divergent in phenetic analyses of AFLPs (Ståhlberg 1999), and nuclear allozymes (Hedrén et al. 2000).

Still, the molecular studies performed so far have been based on restricted numbers of molecular markers. Given the apparent conflicts between phylogenies based on different data sets, phylogenies based on single genes will often be discordant to each other and to the species phylogeny. We therefore conducted the present study in which we obtained thousands of genome-wide SNPs derived from restriction site associated DNA sequencing (RADseq; Hohenlohe et al. 2012). Data sets obtained by RADseq should provide an accurate representation of the phylogenetic relationships across the genome and, accordingly, they should be less biased than other data sets that only describe specific portions of a genome. We use our data to analyze the phylogenetic position of Nigritella relative to Gymnadenia, and we analyze species relationships within each genus. To enable comparison with previous analyses based on ITS data, we also compiled information on major ITS sequence type in the studied material and added these data onto the trees derived from RADseq.

2. Materials and methods

2. 1. Plant Material and DNA extraction

Forty-two samples were included in our analysis, seventeen samples of Nigritella, eighteen samples of Gymnadenia, two samples of Gymnigritella runei, and five samples of Dactylorhiza viridis (syn. Coeloglossum viride) which were used as outgroup. The selected samples of Nigritella covered all taxa treated as species in Hedrén et al. 2018 except for the rare N. carpatica. The samples also included four recently described segregates of Nigritella miniata (Lorenz and Perazza 2012; Table S1), although these were poorly separated according to nuclear microsatellites (Hedrén et al. 2018). Since Nigritella is restricted to Europe, the sampling of Gymnadenia was also focused on the European species (Table S2). The species used as outgroup, Dactylorhiza viridis, represents the earliest branch to split from the rest of the genus Dactylorhiza (Brandrud et al. in press 2019), which is the sister group to Gymnadenia/Nigritella. Like the latter, it also produces nectar. Most of the samples have been used previously in population-based molecular studies (Hedrén and Pedersen 2016, Hedrén et al. 2018) and agree with the taxa they have been affiliated with here.

Sampling was performed carefully to allow for continued survival of the plants, and only portions of above-ground parts were collected. Total DNA was isolated from silica dried flowers with bracts (ca. three to four flowers from Gymnadenia accessions, part of a flowering head from Nigritella accessions; Chase and Hills 1991) by following a cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) procedure (Doyle 1990) or using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen,Venlo, Netherlands). DNA extracts are stored in the DNA bank of MH at Department of Biology, Lund University or in the DNA bank of RMB at Jodrell Laboratory, RBG Kew, as indicated in Table S1. Vouchers in the form of dried flowers are deposited in the Lund University botanical museum (LD) or Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (K), Table S1. Maps of the sampling locations (Fig. 1) were generated using QGIS v. 2.4.071 (QGIS 2015), with a map layer that was extracted from GADM version 1.0 (available from www.gadm.org).

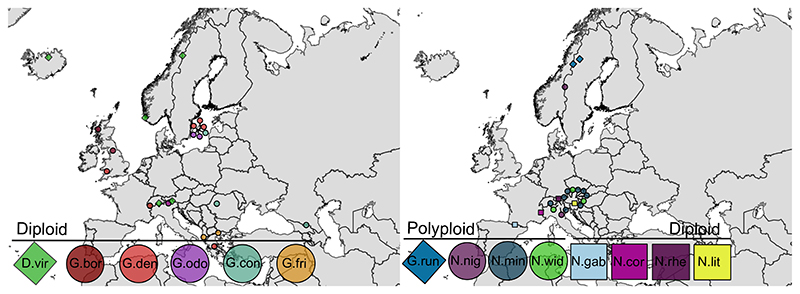

Figure 1.

Sampling maps of five diploid Dactylorhiza, 18 diploid Gymnadenia, 15 polyploid Nigritella and Gymnigritella as well as four diploid Nigritella individuals included in the present study. The map layer was extracted from GADM version 1.0 (available from www.gadm.org). The N. nigra, N. widderi and N. miniata group each comprise multiple taxa.

D.vir=D. viridis, G.bor=G. borealis, G.den=G. densiflora, G.odo=G. odoratissima, G.con=G. conopsea, G.fri=G. frivaldii, G.run=G. runei, N.nig=N. nigra, N.min=N. miniata, N.wid=N. widderi, N.gab=N. gabasiana, N.cor=N. corneliana, N.rhe=N. rhellicani, N.lit=N. lithopolitanica

2. 2. Library Preparation and Sequencing

Part of the material used in Brandrud et al. (in press 2019), were also used for the present study. DNA was purified with the Nucleospin gDNA clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RADseq libraries of 30-72 individuals per library, were prepared following the protocol detailed in Paun et al. (2016), with the following modifications. Depending on the library, for each sample 100–400 ng DNA was used. The DNA was sheared with a Bioruptor Pico using 0.65 ml tubes (Diagenode) and three cycles of 30 sec ON and 60 sec OFF. The inline and index barcodes used differed from each other by at least three sequence positions. The DNA amount of each sample was normalized within libraries. All RADseq libraries were sequenced as single-end 100 bp reads on an Illumina HiSeq platform at VBCF NGS Unit (www.vbcf.ac.at/ngs), Vienna, Austria.

2. 3. Filtering SNPs from RADseq Data

A similar bioinformatics pipeline to that used in Brandrud et al. (in press 2019) was also applied in the present study, but the loci for the synthetic reference were built de novo only from diploid Gymnadenia and Nigritella (i.e., in the absence of a reference genome), followed by mapping both diploid and polyploid accessions to this reference. Finally, variants were called and filtered across all samples.

The raw reads were demultiplexed based on index reads using BamIndexDecoder v. 1.03 (included in Picard Illumina2Bam package, available from http://gq1.github.io/illumina2bam/) and on inline barcodes using PROCESS_RADTAGS from STACKS v. 1.44 (Catchen et al. 2011, 2013). Together with demultiplexing a quality filtering was performed that removed uncalled bases, discarded reads with low quality scores and rescued barcodes and cut sites with maximum one mismatch. RADseq loci were built de novo for the set of diploid individuals with DENOVO_MAP.PL. The final settings used were requiring at least three reads to create a stack (m), allowing maximum one mismatch when merging the loci within individuals (M) as well as among individuals when building the catalog (n). The loci present in at least 50% of individuals and containing between one and 15 SNPs were extracted with EXPORT_SQL.PL in STACKS and a consensus for each of these loci was retained to produce the reference for further analysis.

The reads of diploids and polyploids were mapped back to this synthetic reference by using BOWTIE2 v. 2.2.6 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012) with default settings. Variants were then called with REF_MAP.PL and POPULATIONS in STACKS using default settings to produce a vcf file. PGDSpider v. 2.0.8.2 (Lischer and Excoffier 2011) was used to convert the vcf file to the phylip file used in the maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree and VCFTOOLS v. 0.1.14 (Danecek, Auton et al. 2011) was used to filter the vcf file used for the ordinations.

2.4. RADseq Data Analyses

A maximum likelihood phylogeny of diploid accessions was obtained by running RAxML v. 8.2.9. (Stamatakis 2014). The analysis was performed on the phylip file of concatenated SNPs with the following settings: 1,000 rapid Bootstrap replicates; searching for the best-scoring ML tree with a general time reversible model of nucleotide substitutions; disabled rate heterogeneity among sites model (i.e., the GTRCAT model). As the dataset contained only concatenated SNPs, the ascertainment bias correction of likelihoods (Lewis 2001) was applied, and 1,000 alternative runs on distinct starting trees was used. Dactylorhiza viridis was used as outgroup.

As an alternative approach to assess the phylogenetic relationships among the diploids, a TREEMIX analysis was run, including only accessions of Gymnadenia and Nigritella. For this analysis only one SNP per locus was used to approximate unlinked markers - the input file for TREEMIX was obtained by using VCF-tools, PLINK v. 1.07 (Purcell et al. 2007) and the python script (plink2treemix.py) available at the TREEMIX website (https://bitbucket.org/nygcresearch/treemix/downloads/). TREEMIX was run by successively allowing for migration events and comparing the increase of total variation explained to infer how many migrations to allow. TREEMIX graphs were visualised with RSTUDIO v. 1.0.44 (Rstudio Team 2015) using Rscripts provided with TREEMIX.

To visually illustrate the similarity between diploids and polyploids in the entire dataset (i.e., except Dactylorhiza), Principal Coordinates Analyses, PCoAs based on Euclidian distance, were conducted using the dartR package (Gruber and Georges 2018), based on a dataset including loci with maximum 10% missing data and with each allele found in at least two individuals (--maf). For a better visualization, separate PCoAs were performed for Nigritella diploids and polyploids. Finally, a coancestry analysis was run with FINERADSTRUCTURE v. 0.2. for the Nigritella polyploids only to assess their relationships. The program is using the SNPs on each locus to calculate a nearest neighbour haplotype coancestry between the individuals. The haplotype input file for FINERADSTRUCTURE was created by using the python script (Stacks2fineRAD.py) available from http://cichlid.gurdon.cam.ac.uk/fineRADstructure.html.

To infer the most likely parental species of Gymnigritella runei, VCFTOOLS was used to calculate the unadjusted Ajk statistic (--relatedness option; Yang, Benyamin et al. 2010) between Gymnigritella and each potential parental diploid, as well as between Gymnigritella and each polyploid group of Nigritella, and the results were presented as vioplots in R following Brandrud et al. (in press 2019). Relatedness coefficients, such as Ajk, have been shown to be unbiased with respect to ploidy (Meirmans et al. 2018). Ajk can take values of one for an individual compared to itself, be around zero if individuals from the same population are compared, and take negative values up to -1 otherwise. Finally, for each polyploid lineage a relative measure of inbreeding F was calculated with VCFTOOLs with the option --het. The F results were plotted as vioplots in RSTUDIO. Similar to the population index FIS, the per-individual F estimate is bound from -1 (maximum outcrossing) to 1 (maximum inbreeding), but as it is derived from a vcf file containing only variable sites, it should be regarded as a relative measure of inbreeding. The difference between F distributions between Gymnigritella, on one hand, and each of the three Nigritella polyploids, on the other hand, was tested for statistical significance with Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests in R.

2. 5. Determination of major ITS sequence types

Two major ITS sequence variants (ribotypes) have been identified in Gymnadenia sensu lato (Pridgeon et al. 1997, Gustafsson and Lönn 2003). These variants differ consistently at five positions in ITS1 and at five positions in ITS2, but do not differ in length (Gustafsson and Lönn 2003, Stark et al. 2011). In the following, the two variants are denoted ITS-E (found in early-flowering G. conopsea/G. odoratissima), and ITS-L (found in late-flowering G. conopsea/G.densiflora), respectively (cf. Gustafsson and Lönn 2003). For samples that were not already sequenced for ITS, we took advantage of a simplified protocol to rapidly screen the accessions for major ITS type by means of tetra-primer ARMS-PCR (Amplification-Refractory Mutation System), which is a protocol designed for SNP identification (Chiapparino et al. 2004). In ARMS-PCR fragments differing at single positions are selectively amplified by alternative primer pairs giving rise to fragments of different lengths, which enables simple screening by gel electrophoresis. Details of our protocol have been given in a previous paper (Hedrén et al. 2018).

3. Results

The demultiplexed data contained on average 1.2 million (+/- 1.1 SD) quality reads per individual. The data has been deposited in the NCBI Short Reads Archive (BioProject ID PRJNA489792, SRA Study SRP160094 and BioProject ID PRJNA517232, SRA Study SUB5087961, Table S1). From a de novo diploid catalog building with STACKS we retained 3,793 polymorphic loci of 94 bp for the synthetic reference according to the criteria mentioned above. The average mapping percent on this reference was ~30%.

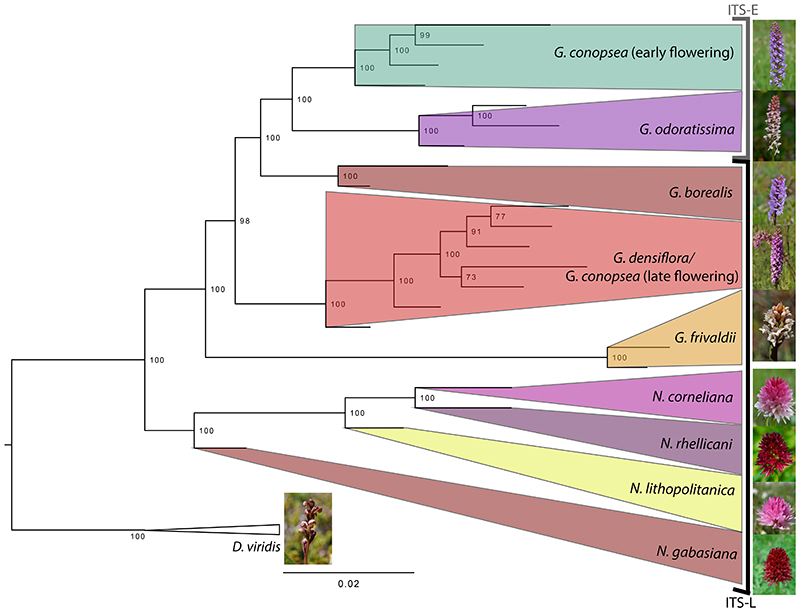

For the phylogenetic analysis on a dataset of 18,007 RADseq-derived SNPs including all samples of Gymnadenia, as well as four diploid members of Nigritella (Fig. 2), Gymnadenia and Nigritella came out as fully supported monophyletic sister groups. Within Gymnadenia, the following clades were distinguished with 100% support: G. conopsea s. str. (early flowering), G. odoratissima, G. borealis, G. densiflora/G. conopsea (late flowering) and G. frivaldii. The latter came out as sister to the rest of the Gymnadenia species. Except for the G. densiflora/G. conopsea late flowering complex, all RADseq clades were well in correspondence with the classification based on morphology.

Figure 2.

The best-scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of a concatenated dataset of 18,007 SNPs from 22 accessions of diploid Gymnadenia and Nigritella. Five samples of the diploid Dactylorhiza viridis were included as outgroup. Photos by Sven Birkeland, Richard Lorenz and Heinz-Werner Zaiss.

We also mapped the major ITS types recorded in the samples onto this tree. The clade composed of G. odoratissima and G. conopsea s.str. all had ITS-E, while the remaining samples of Gymnadenia, i.e. G. frivaldii, G. densiflora, late flowering G. conopsea, and all Nigritella had ITS-L. The general topology of the TREEMIX analysis (Fig. S1) was consistent with the phylogenetic relationships found in the RAxML analysis. One migration event between Gymnadenia and Nigritella, i.e. between the common ancestor of G. conopsea s.str. and G. odoratissima and N. gabasiana, improved the variation explained from 95.8% (without any migration event) to 98.1% (one migration allowed). An additional migration event (summing up two altogether) improved the variation contained by only 0.1%, which was considered insignificant and the scenario with one migration event was finally chosen.

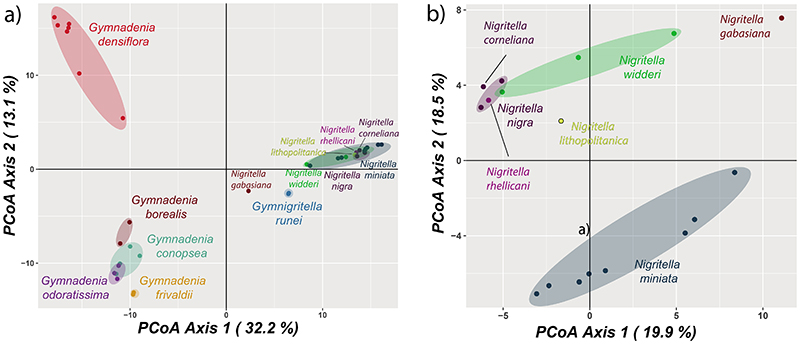

In the resulting plot given by the first two axes of the PCoA of all material (Fig. 3a), Gymnadenia and Nigritella are separated along the first axis that explains as much as 32.2% of the genetic variation. Gymnigritella runei and N. gabasiana take a somewhat intermediate position, although still closer to the reminder of Nigritella. The second axis separates G. densiflora from the other Gymnadenia, and the third axes separates G. frivaldii from the rest (result not shown). In the PCoA of Nigritella only, the polyploids are separated along axis 2, with N. miniata in one end and N. widderi and N. nigra in the other. The diploid N. rhellicani and N. corneliana appear close to the N. nigra group, whereas N. lihopolitanica and, in particular, N. gabasiana differ from the rest. The first three axes of this PCoA describe 47.7 % of the total variation.

Figure 3.

PCoA analysis performed with the dartR package (Gruber and Georges 2018). (a) PCoA on 6,487 SNPs from 18 diploid Gymnadenia, four diploid Nigritella, 13 polyploid Nigritella, and two Gymnigritella individuals. (b) PCoA on 2,038 SNPs from with 13 polyploid Nigritella and four diploid Nigritella individuals. The N. nigra, N. widderi and N. miniata group each comprise multiple taxa.

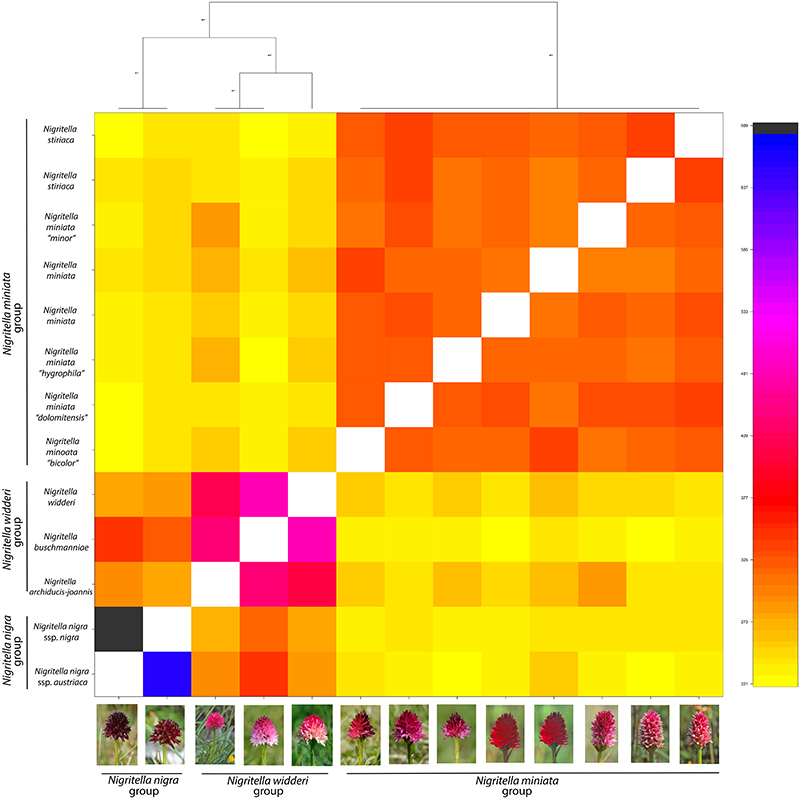

The FINERADSTRUCTURE result shows three groups within the Nigritella polyploids; the N. nigra group, the N. widderi group and the N. miniata group. The amount of coancestry shared within each group differed, with N. nigra accessions sharing comparatively many haplotypes with each other, followed by N. widderi and N. miniata. Futher, N. nigra and N. widderi seem to share more with each other that either of them does with N. miniata. The relatedness plots of the polyploids to the putative parents was analysed. The relatedness vioplots show the highest relatedness of Gymnigritella to G. conopsea among the Gymnadenia diploids (Fig. S2a) and to polyploid N. nigra s.l. among the Nigritella taxa (Fig. S2b), confirming Gymnigritella as an allopolyploid. Investigating the degree of heterozygosity in the polyploid lineages, the relative F values of Gymnigritella took positive but low values, not different from N. widderi and N. miniata suggesting an allopolyploid origin for these lineages (Fig. S2c). Nigritella nigra showed higher F values than Gymnigritella, and even though the distributions were not significantly different, this most likely indicate an origin starting from more closely related parentals.

4. Discussion

4. 1. The relationship between Gymnadenia and Nigritella

All ITS-based analyses published so far (Pridgeon et al. 1997, Bateman et al. 2003, Bateman et al. 2006, Stark et al. 2011), have shown Nigritella to be embedded within Gymnadenia. Additionally, phylogenetic analyses combining ITS with other sequence data have also shown such a pattern (Inda et al. 2012, Sun et al. 2015). Specifically, it has been found that G. conopsea s.str. (early-flowering) together with G. odoratissima form one monophyletic clade characterized by ITS-E, and all other members of Gymnadenia (e.g. late-flowering G. conopsea, G. densiflora, G. borealis, G. orchidis, G. crassinervis, G. frivaldii) together with members of Nigritella form another monophyletic clade characterized by ITS-L (Gustafsson and Lönn 2003). Based on ITS sequences, it could thus be argued that Nigritella should be part of Gymnadenia (Bateman et al. 1997).

However, all our analyses based on tens of thousands of genome-wide SNPs derived from RADseq indicate that the genus Nigritella is separated from the genus Gymnadenia. The phylogenetic analyses using RAxML and TREEMIX arranged all Gymnadenia and all Nigritella, respectively, in two separate and well-supported monophyletic clades. In the PCoA plots (Fig. 3b), members of Nigritella formed a distinct cluster clearly separated from members of Gymnadenia.

The split between Nigritella and Gymnadenia observed here also agree with patterns obtained from other genomic regions than ITS, including AFLPs (Ståhlberg 1999), allozymes (Hedrén et al. 2000), nuclear microsatellites (Hedrén et al. 2018), plastid tRNA-Leu intron (Bateman 2001) and plastid VNTRs (Hedrén et al. 2018). Also phylogenetic analyses of plastid rpl16 intron and mitochondrial cox1 sequence data agree with this basal split (Inda et al. 2012), although the number of samples in these analyses were restricted. When all evidence is taken together, we conclude that Nigritella and Gymnadenia can be validly treated as separate genera, also when a phylogenetic criterion is applied (Bateman 2009).

Because of its high variability, the ITS region has been used extensively to analyse species delimitations and species relationships in many groups of flowering plants (Baldwin et al. 1995, Álvarez and Wendel 2003). However, several types of genetic mechanisms are known to contribute to molecular evolution of the ITS regions. These mechanisms result in sequence divergence, incomplete lineage sorting, as well as homogenization, and for these reasons analysis of ITS sequence data may not necessarily reflect organismal phylogeny (Álvarez and Wendel 2003). First, the nuclear DNA regions harboring ITS are subject to a biased concerted evolution (Baldwin et al. 1995), by which divergent copies of the rDNA repeats are homogenized against each other, often in a repeated way. Such homogenization may go in the direction towards one or the other of the divergent copies, or may result in repeats of intermediate appearance (Wendel et al. 1995). Similarly, whenever divergent rDNA repeats occur together within a genome, chimeric repeat types combining portions of the parental sequences may be produced in addition to the parental types (Devos et al. 2006), and may eventually become fixed within the genome. Yet a possibility is that multiple repeat types are retained, and maintained within a single genome without much of integration. In the phylogenies obtained from analysis of RADseq data, it appears that ITS differentiation does not fully reflect the phylogeny of the Nigritella/Gymnadenia clade within the Orchidinae, and that ITS artifactually places Nigritella as a subclade within Gymnadenia. Specifically, it appears that the ITS-E sequence type evolved in the common ancestor to G. conopsea s.s and G. odoratissima from a plant with ITS-L type of ITS. Alternatively, the two major ITS types may both have been present in the common ancestor to the Nigritella/Gymnadenia clade. The present-day distribution of major ITS types may then be the result of fixation of alternative types in branches that have diverged later on, one of which corresponds to present day Nigritella. Gene flow (Fig. S1), perhaps via allopolyploids similar to the extant Gymnigritella, followed by concerted evolution may have also played a role in shaping a similar ITS type between the two genera.

4. 2. Relationships within Gymnadenia

Gymnadenia frivaldii was the sister to the rest of Gymnadenia in our SNPs-based analyses. This position differs from that given by ITS-based phylogenies, according to which G. frivaldii is embedded in the clade of Gymnadenia/Nigritella characterised by ITS-L (Bateman et al. 2006, Stark et al. 2011). However, Gymnadenia frivaldii differs from other species of Gymnadenia in, e.g., a relatively short spur and in structure of the column (Bateman et al. 2006), and its basal position in the genus could be seen in light of its somewhat deviating morphology.

The finding that G. conopsea s.str. and G. odoratissima are sister species is in agreement with ITS-based phylogenies, as they are both characterized by the ITS-E type. Gymnadenia borealis was found to be the successive sister species to this group. This placement may seem surprising as it is characterized by ITS-L (Pridgeon et al. 1997, Bateman et al. 2003, 2006, Stark et al. 2011). However, it resembles G. conopsea s.str. as well as G. densiflora in general morphology (Rich 2012).

Finally, as in Gustafsson and Lönn (2003), we found that late-flowering G. conopsea grouped together with G. densiflora. Both are characterized by having ITS-L. These results suggest that late-flowering plants similar to G. conopsea in size and overall morphology, should be included in G. densiflora, which requires an emended circumscription of the latter.

4.3. Relationships within Nigritella

The diploid members of Nigritella constitute a monophyletic sister group to Gymnadenia in the phylogenetic tree as well as in the TREEMIX analysis. The placement of N. gabasiana as the basalmost species in Nigritella is in agreement with plastid VNTR data (Hedrén et al. 2018), according to which it is clearly separated from other diploid members of Nigritella. Furthermore, all members of Nigritella, including polyploid representatives could be separated as relatively distinct clusters separated from the Gymnadenia samples in the PCoA ordination (Fig. 3a). These observations support the hypothesis that polyploid members of Nigritella have originated from diploid members of the same genus without contribution from Gymnadenia (Hedrén et al. 2000).

Except for N. nigra, which seems to be related to the extant N. corneliana and N. rhellicani, we were not able to match polyploid Nigritella to any specific diploid member of the genus included in the analysis. The polyploids have previously been hypothesized to at least partly have originated from now extinct diploid ancestors (Hedrén et al. 2000, 2018). Because they are highly heterozygous at nuclear codominant loci including allozymes and microsatellites, polyploid members of Nigritella are believed to be of hybrid origins, which is confirmed here by results of F coefficients that take similar values as Gymnigritella. On basis of AFLPs (Ståhlberg 1999), allozymes (Hedrén et al. 2000) and microsatellites (Hedrén et al. 2018), the polyploids have been found to aggregate in three groups, the nigra group (N. nigra ssp. nigra, N. nigra ssp. austriaca and, less strongly attached, Gymnigritella runei, see below), the widderi group (N. widderi, N. buschmanniae and N. archiducis-joannis) and the miniata group (N. miniata and N. stiriaca). These groups were also identified in our FINERADSTRUCTURE analyses based on RADseq (Fig. 4), but the numbers of samples were insufficient to examine the exact subdivision of each group. Given that different taxa in Nigritella are much less differentiated from each other than taxa in Gymnadenia, the number of variable SNPs within Nigritella should be relatively few. We would therefore need an extended data set including additional samples per taxon, additional populations of the diploids and perhaps also deeper sequencing with higher coverage to obtain detailed knowledge on fine-scale relationships in Nigritella.

Figure 4.

Heatmap obtained with FINESTRUCTURE on 3,447 RADseq loci for 13 polyploid Nigritella individuals. Photos by Sven Birkedal and Richard Loren

The RADseq was informative on the position and origin of Gymnigritella runei, which is a polyploid with a restricted distribution in the Scandinavian mountains (Teppner and Klein 1989, Rune 1993). According to our data, this polyploid has originated from a recent hybridization between G. conopsea s.str. and N. nigra ssp. nigra, which is evident from nuclear codominant markers as well as ITS at which it combines ITS-L from Nigritella with ITS-E from G. conopsea s.str. (Hedrén et al. 2018). We included two samples of Gymnigritella runei in our analyses. In the PCoA, they take a position intermediate between the Nigritella cluster and the portion of the Gymnadenia cluster in which samples with ITS-E are located (Fig, 4a). The relatedness plot identifies G. conopsea s. str. and N. nigra as the most likely parental species (Fig. S2), which is in correspondence with the conclusion of former studies (see e.g. Hedrén et al. 2018). The localities for Gymnigritella runei are situated relatively close to the main distribution area of N. nigra ssp. nigra in mid Scandinavia, suggesting that the former has a post-glacial origin (Rune 1993).

5. Conclusion

A sister group relationship between orchid genera Gymnadenia and Nigritella is supported by restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RADseq). Restricted gene flow between the two genera may explain why specific gene trees are discordant to the species tree topology.

The Scandinavian endemic Gymnigritella runei is supported to have originated from extant G. conopsea and N. nigra. Within Gymnadenia, the separation of G. densiflora and late flowering G. conopsea from early flowering G. conopsea s.str., as already indicated by ITS sequence data, is supported. Within Nigritella, the affiliation of polyploid taxa into three distinct groups; the N. nigra group, the N. widderi group and the N. miniata group, is supported.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Bateman, Sven Birkedal, Mark Chase, Wolfram Foelsche, Olivier Gerbaud, Cesario Giotta, Norbert Griebl, Sven Hansson, Erich Klein, Marc Lewin, Henrik Ærenlund Pedersen, Giorgio Perazza, David Ståhlberg, Eva Waldemarson and Heinz-Werner Zaiss for providing samples, photos, and/or valuable comments on this study. Financial support was given by the Royal Physiographic Society Lund, Nilsson-Ehle foundation to MH and Austrian Science Fund (FWF, Project Y661-B16) to OP.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Álvarez I, Wendel JF. Ribosomal ITS sequences and plant phylogenetic inference. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2003;29:417–434. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin BG, Sanderson MJ, Porter MJ, Wojciechowski MF, Campbell CS, Donoghue MJ. The ITS region of nuclear ribosomal DNA: a valuable source of evidence on angiosperm phylogeny. Annals of Missouri Botanical Garden. 1995;82:247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM. Evolution and classification of European orchids: insights from molecular and morphological characters. J Eur Orch. 2001;33:33–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM. Evolutionary classification of European orchids: the crucial importance of maximizing explicit evidence and minimizing authoritarian speculation. J Eur Orch. 2009;41:243–318. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM, Murphy AR, Hollingsworth PM, Hart ML, Denholm I, Rudall PJ. Molecular and morphological phylogenetics of the digitate-tubered clade within subtribe Orchidinae ss (Orchidaceae: Orchideae) Kew Bulletin. 2018;73:54. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM, Pridgeon AM, Chase MW. Phylogenetics of subtribe Orchidineae, Orchidoideae, Orchidaceae) based on nuclear ITS sequences. 2. Infrageneric relationships and classification to achieve monophyly of Orchis sensu stricto. Lindleyana. 1997;12:113–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM, Hollingsworth PM, Preston J, Yi-Bo L, Pridgeon AM, Chase MW. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution of Orchidinae and selected Habenariinae (Orchidaceae) Bot J Linn Soc. 2003;142:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM, Rudall PJ, James KE. Phylogenetic contexts, genetic affinities and evolutionary origin of the enigmatic Balkan orchid Gymnadenia frivaldii Hampe ex Griseb. Taxon. 2006;55:107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Künkele S, Lorenz R. Orchideen Europas – Ulmer Naturführer. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brandrud MK, Baar J, Lorenzo MT, Bateman RM, Chase MW, Hedrén M, Paun O. Phylogenomic relationships of diploids and the origins of allotetraploids in Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) Systematic Biology. 2020;69:91–109. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syz035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catchen JM, Amores A, Hohenlohe P, Cresko W, Postlethwait JH. Stacks: building and genotyping loci de novo from short-read sequences. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2011;1:171–182. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catchen JM, Hohenlohe PA, Bassham S, Amores A, Cresko WA. Stacks: an analysis tool set for population genomics. Molecular Ecology. 2013;22:3124–3140. doi: 10.1111/mec.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase MW, Hills HH. Silica gel: an ideal material for field preservation of leaf samples for DNA studies. Taxon. 1991:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Chiapparino E, Lee D, Donini P. Genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms in barley by tetraprimer ARMS-PCR. Genome. 2004;47:414–420. doi: 10.1139/g03-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens J, Kleynen J. Form and function. Privately published; 2011. The flower of the European orchid; pp. 1–440. [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, Handsaker RE, Lunter G, Marth GT, Sherry ST, McVean G, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos N, Raspé O, Oh S-H, Tyteca D, Jacquemart A-L. The evolution of Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) allotetraploid complex: Insights from nrDNA sequences and cpDNA PCR-RFLP data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2006;38:767–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaud O, Schmid W. Die Hybriden der Gattungen Nigritella und/oder Pseudorchis [Les hybrids des genres Nigritella et/ou Pseudorchis] Cahiers de la Société Française d’Orchidophilie. 1999;5:1–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gjærevoll O. Plantegeografi – Tapir. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber B, Unmack PJ, Berry OF, Georges A. dartr: An r package to facilitate analysis of SNP data generated from reduced representation genome sequencing. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2018;18:691–699. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson S. Patterns of genetic variation in Gymnadenia conopsea. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9:1863–1872. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson S, Sjögren-Gulve P. Genetic diversity in the rare orchid, Gymnadenia odoratissima and a comparison with the more common congener, G. conopsea. Conservation Genetics. 2002;3:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson S, Lönn M. Genetic differentiation and habitat preference of flowering-time variants within Gymnadenia conopsea. Heredity. 2003;91:284–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M, Pedersen HÆ. Symbolae Botanicae Upsalienses. Uppsala University; 2016. Plastid DNA microsatellite data do not support recognition of subspecies in Coeloglossum viride (L.) Hartm.(Orchidaceae) in northern Europe; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M, Klein E, Teppner H. Polyploid evolution in the European orchid genus Nigritella: evidence from allozyme data. Phyton. 2000;40:239–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M, Lorenz R, Teppner H, Dolinar B, Giotta C, Griebl N, Hansson S, Heidtke U, Klein E, Perazza G, Ståhlberg D, et al. Evolution and systematics of polyploid Nigritella (Orchidaceae) Nordic Journal of Botany. 2018 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hohenlohe PA, Catchen J, Cresko WA. Population genomic analysis of model and nonmodel organisms using sequenced RAD tags. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2012;888:235–260. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-870-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inda LA, Pimentel M, Chase MW. Phylogenetics of tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae) based on combined DNA matrices: inferences regarding timing of diversification and evolution of pollination syndromes. Ann Bot. 2012;110:71–90. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen RA, Cluster PD. Modes and tempos in the evolution of nuclear ribosomal DNA: new characters for evolutionary studies and new markers for genetic and population studies. Annals of Missouri Botanical Garden. 1988;75:1238–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger RT, Byers KJ, Francisco RMDB, Staedler YM, LaFountain AM, Schönenberger J, Schiestl FP, Schlüter PM. Emergence of a floral colour polymorphism by pollinator-mediated overdominance. Nature communications. 2019;10:63. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07936-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PO. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst Biol. 2001;50:913–925. doi: 10.1080/106351501753462876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischer HE, Excoffier L. PGDSpider: an automated data conversion tool for connecting population genetics and genomics programs. Bioinformatics. 2011;28:298–299. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz R, Perazza G. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Blütenmorphologie der Artengruppe Nigritella miniata s.l. (Orchidaceae) in den Ostalpen. Gredleriana. 2012;12:67–146. [Google Scholar]

- Løjtnant B. In: Nordens orkidéer (Danish edition) Mossberg B, Nilsson S, editors. Vol. 76. Gyldendals; Köpenhamn: 1977. I. [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans PG, Liu S, van Tienderen PH. The analysis of polyploid genetic data. J Heredity. 2018;109:283–296. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esy006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DM. Tutin TG, Heywood VH, Moore DM, Valentine DH, Walters SM, Webb DA. Flora Europea. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press; 1980. Gymnadenia R.Br., Nigritella L.C.M. Richard; pp. 332–333. [Google Scholar]

- Paun O, Turner B, Trucchi E, Munzinger J, Chase MW, Samuel R. Processes driving the adaptive radiation of a tropical tree Diospyros Ebenaceae) in New Caledonia, a biodiversity hotspot. Systematic Biology. 2016;65:212–227. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridgeon AM, Cribb PJ, Chase MW, Rasmussen FN. Genera orchidacearum. 1 Vol. 2. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pridgeon AM, Bateman RM, Cox AV, Hapeman JR, Chase MW. Phylogenetics of subtribe Orchidineae (Orchidoideae, Orchidaceae) based on nuclear ITS sequences. 1. Intergeneric relationships and polyphyly of Orchis sensu lato. Lindleyana. 1997;12:89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PIW, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole genome association and population-based linkage analyses. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QGIS. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project; 2015. http://www.qgis.org/ [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, Inc; Boston, MA: 2015. http://www.rstudio.com . [Google Scholar]

- Rich TCG. Gymnadenia conopsea. 2nd. Botanical Society of the British Isles; 2012. Plant Crib 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rune O. Distribution and ecology of Gymnigritella runei: a new orchid in the Scandinavian mountain flora. Opera Bot. 1993;121:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Scacchi R, de Angelis G. Isoenzyme polymorphisms in Gymnadenia conopsea and its inferences for systematics within this species. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 1989;17:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Soliva M, Widmer A. Genetic and floral divergence among sympatric populations of Gymnadenia conopsea s.l. Orchideaceae) with different flowering phenology. Int J Plant Sci. 1999;160:897–905. doi: 10.1086/314192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysisof large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark C, Michalski SG, Babik W, Winterfeld G, Durka W. Strong genetic differentiation between Gymnadenia conopsea and G. densiflora despite morphological similarity. Plant Syst Evol. 2011;293:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhlberg D. Polyploid evolution in the European orchid genus Nigritella: evidence fromDNA fingerprinting. Unpublished Master’s thesis. Institutionen för Systematisk Botanik, Lunds Universitet; 1999. [Accessed 2016-11-14]. https://lup.lub.lu.se/record/2026859 . [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Schlüter PM, Gross K, Schiestl FP. Floral isolation is the major reproductive barrier between a pair of rewarding orchid sister species. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2015;28:117–129. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundermann H. Europäische und Mediterrane Orchideen. 3. Schmersow; Hildesheim: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Teppner H. Adventitious embryony in Nigritella (Orchidaceae) Folia Geobot Phytotax. 1996;31:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Teppner H. A review of new results in Nigritella (Orchidaceae) - Sprawozdania z posiedzeń komisji naukowych [reports of the scientific committee] Polska Akademia Nauk. 2004;46(2):111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Teppner H, Klein E. Gymnigritella runei spec nova (Orchidaceae-Orchideae) aus Schweden. Phyton. 1989;29:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Teppner H, Klein E. Nigritella rhellicani spec nova und N nigra (L) Rchb f sstr (Orchidaceae-Orchideae) Phyton. 1990;31:5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Trávníček P, Jersáková J, Kubátová B, Krejčíková J, Bateman RM, Lučanová M, Krajníková E, Těšitelová T, Štípková Z, Amardeilh J-P, Brzosko E, et al. Minority cytotypes in European populations of the Gymnadenia conopsea complex (Orchidaceae) greatly increase intraspecific and intrapopulation diversity. Ann Bot. 2012;110:977–986. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vöth W. Gymnadenia, Nigritella und ihre Bestäuber. J Eur Orch. 2000;32:547–573. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Schnabel A, Seelanan T. Bidirectional interlocus concerted evolution following allopolyploid speciation in cotton (Gossypium) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92:280–284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Benyamin B, McEvoy BP, Gordon S, Henders AK, Nyholt DR, Madden PA, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Goddard ME, et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nature genetics. 2010;42:565. doi: 10.1038/ng.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.