Abstract

Objective

Running randomized clinical trials (RCT) in fetal therapy is challenging. This is no different for fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (FETO) for severe left-sided Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH). We assessed the knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of maternal-fetal medicine specialists toward the antenatal management of CDH, and the randomized controlled clinical (RCT) “Tracheal Occlusion To Accelerate Lung growth-trial.”

Methods

A cross-sectional KAP-survey was conducted among 311 registrants of the 18th World Congress in Fetal Medicine.

Results

The overall knowledge of CDH and FETO was high. Remarkably only 45% considers prenatal prediction of neonatal outcome reliable. Despite, in their clinical practice they perform severity assessment (80%) and refer families for FETO either within the context of an RCT (43%) or on patient request (32%). Seventy percent perceives not offering FETO on patient demand seems as if no treatment is provided to a fetus with predicted poor outcome. Only 20% of respondents considers denying access to FETO on patient demand not as a psychological burden.

Conclusion

Often the views of individual respondents contradicted with their clinical practice. It seems that, for severe CDH, clinicians face personal and practical dilemmas that undermine equipoise. To us, this indicates the tension between the clinical and scientific obligations physicians experience.

1. Introduction

In fetal medicine, it has been quite difficult to successfully run randomized clinical trials (RCT). For instance, the recent trial on prenatal treatment of urinary tract obstruction was discontinued because of poor recruitment.1 Among other factors, delay in high-quality evidence finding, may cause clinicians and their patients to develop their own bias, based on small, heterogenic, observational studies, and potentially leading to the loss of equipoise.2 This has also been the case for the antenatal management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH).

In CDH the partial or complete absence of the diaphragm leads to herniation of the abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity, which impairs prenatal lung development.3 Prenatal diagnosis is made in two thirds of cases,4,5 and the severity of the condition can be prenatally assessed.6 Fetuses diagnosed with severe left-sided CDH have less than 25% chance of postnatal survival.7,8 This makes it a candidate condition for fetal surgery. There is experimental and clinical evidence that fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (FETO) improves lung size hence neonatal outcome.9-11 Because of lack of robust evidence for benefit of FETO,12,13 FETO is being investigated in an RCT, entitled “Tracheal Occlusion To Accelerate Lung growth (TOTAL).14” Patients are randomized to either undergo FETO or to be expectantly managed antenatally, followed by standardized perinatal management and postnatal repair of the defect.

At the start of the TOTAL trial, the ethical character of randomization was extensively discussed, including questioning whether the clinical community was in equipoise.15 Equipoise, the existence of genuine uncertainty within a community regarding the benefits of one treatment compared to another, is a prerequisite for executing any RCT.16 Implying genuine uncertainty, RCTs aim to be consistent with the ethical duties of doctors, as patients should not be allocated to an inferior therapy. At the start of the TOTAL trial, it was agreed that equipoise was present, as FETO as a therapy still remained an experimental procedure, and existing preferences for therapy among clinicians mainly depended on the availability of FETO.15 That debate delayed the start of the trial with two years.17

Together with the generic challenges of patient recruitment in fetal treatment trials due to the relatively rareness and detection rates of the conditions, the TOTAL-trial is taking now 10 years to be concluded. Recently, some clinicians questioned again the ethical character of randomization for severe CDH cases, and some centers withdrew from the TOTAL trial, based on their loss of equipoise. To catch up with actuality, the organizers of the 18th World Congress in Fetal Medicine organized a debate on the prenatal management of CDH session.18 This world congress is the largest annual conference in fetal medicine. The discussants debated whether FETO should be offered exclusively within an RCT or also offered outside the research setting.19,20 The conference provided a suitable setting to assess the knowledge, opinions and practice of fetal-maternal specialists on the antenatal management of CDH. We thought this would not only inform us on the views of specialist on the TOTAL-trial, but also on how this may impact design and execution of this and any future fetal treatment trials.

2. Methods

This is an international, cross-sectional and anonymous knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) survey to which the 2186 registrants of the 18th World Congress in Fetal Medicine (Alicante, Spain, June 2019) were invited to participate. The survey was specifically designed around a debate regarding the provision of FETO for severe left-sided CDH, either exclusively within an RCT or on patient preference.

2.1. Design

We designed this survey to assess the knowledge, attitude and behavior of physicians involved in fetal medicine, regarding the option for patients to have FETO, either on request or within the running global TOTAL trial,21,22 according to the World Health Organization KAP-guidelines.23 The University Hospitals Leuven was the sponsor of this study.

A draft survey was designed based on a thorough literature search and discussion with selected experts in fetal surgery and ethics (Data S1). First, the expected knowledge to comprehend the dilemma was determined (condition, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis and ethics) (Knowledge),7,9,11,12,15-17,24-28 as well as the different clinical management pathways for mothers with fetuses diagnosed with isolated severe left sided CDH (Practice). Based on the literature regarding RCTs and equipoise, and the discussion preceding the TOTAL trial,15,16,29-38 statements were formulated to create contrasting opinions (Attitude). The agreed draft was pilot-tested for readability and understandability among a group of fetal-maternal researchers (Data S1), by means of the “think-aloud” method: the fetal-maternal specialists were asked to read the question and repeat in their own words what the question was asking, followed by an explanation of how they would answer the question and why.39 Questions were amended accordingly. As a final step, the survey was scored for content validity by a group of clinicians and researchers from the University Hospitals Leuven familiar with management of fetuses or neonates with CDH (neonatologists, researchers, fetal-maternal specialists, fetal surgeons, pediatric surgeons, n = 8) (Data S1). Clinicians were asked to rank each question on relevance, ranging from 1-4 (1 = not relevant; 4 = highly relevant). The item-level content validity index (I-CVI) was calculated, and questions with an I-CVI < 0.75 were excluded (three in total; two for knowledge, one for attitude) (Data S2).40 Each knowledge question had one right answer, based on the available literature.9,11,16,25,28 Therefore, each respondent received a “knowledge score” ranging from 0 to 8 correct questions. As mentioned earlier, the attitude statements were made to divide participants according to different attitudes. The expert group decided that respondents agreeing to statement A3 confirm equipoise. Similarly, agreeing to statement A7 and disagreeing to statement A8 indicated a preference for FETO exclusively within an RCT (proponent of RCT); conversely disagreeing to statement A7 and agreeing with statement A8, indicating a preference for offering FETO outside the research setting (opponent of RCT) (detailed in Data S2). The practice questions queried whether respondents assess and counsel patients carrying a fetus with CDH. In an effort to assess their practice, we combined respondents that offer (n = 160) and refer for FETO (n = 86) into one group (total n = 246) and divided them in three categories, based on how they manage their patients: (a) FETO only within an RCT, (b) FETO on request of the parents, (c) leave the decision to a tertiary center or to the parents (Data S2).

The final version of the survey (Data S3) consisted of 25 multiple-choice questions (first question on informed consent):

Demographic information of the participant (6 questions).

Information about the participant’s knowledge on CDH and FETO (8 questions).

The participant’s attitude to CDH and FETO (8 questions).

The participant’s practice in patients with a fetus with severe CDH (the population of interest to the TOTAL trial) (3 questions).

2.2. Participants and data-collection

The World Congress in Fetal Medicine is a large international conference typically attended by clinicians, who have a specific interest in maternal-fetal medicine. They are considered as representative of health care professionals who first see patients with the prenatal diagnosis of CDH, hence relevant to our research. Attendees were invited to this survey during the conference by distributing flyers and showing a link to the survey before and after the debate.

In addition, an invitation was sent by email to all attendees of the conference 10 days later. The survey remained open until 6 weeks after the conference. The online survey (LimeSurvey version 2.00+ Build 130 708, The LimeSurvey Project Team, Hamburg, Germany) was accessible from June 26th 2019 until August 10th 2019. Participating in the survey was anonymous.

2.3. Data-analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, New York, NJ, USA). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare knowledge scores between groups. A value of P < .05 was considered significant. All data are reported as number, percentage, median and interquartile range (IQR).

2.4. Poll

Prior to the debate, we conducted an on-site poll on the prenatal management of CDH by real time tele-voting to measure the impact of the debate on whether there is still equipoise on fetal therapy.19,20 This debate was part of the program of the World Congress in Fetal Medicine. Participants answered four questions (Data S4) about their view on the possibility to offer FETO outside the context of a trial, and immediately after.

2.5. Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals Leuven (S62866). At the start of the survey, all participants were shown instructions to the survey and asked to provide confirmation of informed consent by ticking a box. The anonymous data were kept in an electronic database located on the protected server allocated to the PI. This is a password protected domain and access was limited to the personnel involved in the study (PI, sub-investigators, administrators). The data will be stored for 5 years after the end of the study.

3. Results

Four-hundred and sixty-seven attendees started the questionnaire (initial response rate 22%). Of those, 156 (33%) did not finish the questionnaire, either while filling out the demographic questions (n = 68/156, 44%) or later on (n = 88/156, 56%). Eventually, this left us 311 completed questionnaires of which 44 were completed on the day of the debate. The demographics of participants are displayed in Table 1. Over 80% were maternal fetal medicine (MFM) specialists, fetal surgeons or obstetricians, 75% had 6 years of clinical experience or more and 64% were involved in research.

Table 1. Demographic variables of study participants.

| Parameter | Number of participants (n = 311) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 161 (52%) |

| Male | 149 (48%) |

| NA | 1(<1%) |

| Main profession | |

| Maternal-fetal medicine specialist | 217 (70%) |

| Trainee | 26 (8%) |

| Fetal surgeon | 25 (8%) |

| Obstetrician | 12 (4%) |

| Sonographer | 12 (4%) |

| Physician not involved in fetal medicine | 10 (3%) |

| Radiologist | 3(1%) |

| Pediatrician | 2 (1%) |

| Researcher fetal medicine | 2 (1%) |

| Pediatric Surgeon | 1(<1%) |

| Geneticist | 1(<1%) |

| Country currently working in | |

| Europe | 193 (62%) |

| Asia | 36 (12%) |

| North America | 29 (9%) |

| South America | 21 (7%) |

| Africa | 7 (2%) |

| Oceania/Australasia | 7 (2%) |

| Other | 18 (6%) |

| Years of experience in fetal medicine | |

| 0-5 | 76 (24%) |

| 6-10 | 61 (20%) |

| >10 | 170 (55%) |

| Currently involved in research in fetal medicine | 197 (64%) |

| Attended the debate | 234 (75%) |

Note: Data are displayed as n(percentage).

1. Knowledge

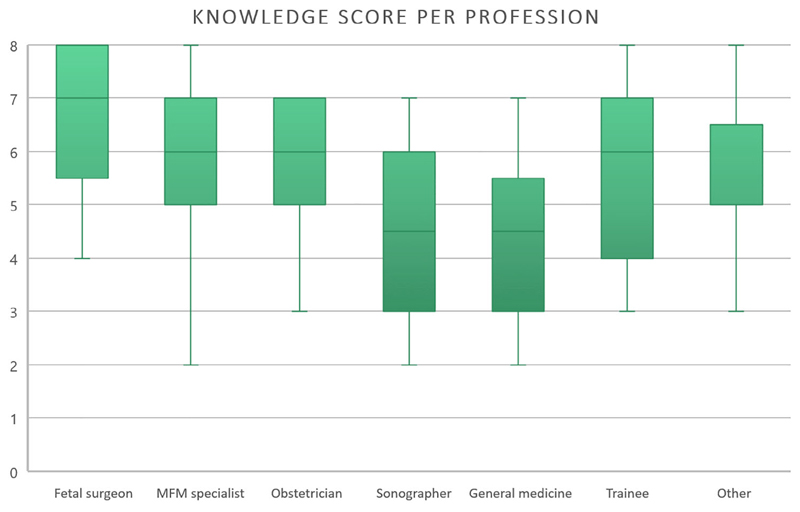

Table 2 displays the answers to the eight questions measuring knowledge. On average, respondents correctly answered 6 out of the 8 questions (median 6.0, IQR 5.0-7.0; n = 311). Only 45% (n = 139/311) agreed that neonatal survival in isolated left sided CDH can be reliably predicted in the prenatal period. There was a lack of knowledge “on the availability of emergency in utero balloon removal in tertiary care hospitals” and “evidence from RCTs on FETO” in 44% and 42% respectively. Of all professional categories, fetal surgeons scored the highest on knowledge questions (7 out of 8 questions; 5.75-8.0, n = 25) (Figure 1). Those involved in MFM-research had a knowledge score of 6 (5.0-7.0, n = 197). Respondents who attended the debate scored higher than those who did not (6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 234] vs 5.0 [4.0-6.0, n = 77]; P = .021).

Table 2. Distribution of answers to the eight knowledge questions.

| Statement | True | False | I do not know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | Clinical equipoise is a genuine uncertainty in the clinical community about which treatment is best for patients in a defined population | 253 (81%)* | 22 (7%) | 36 (12%) |

| K2 | The expected survival rate of severe lung hypoplasia, without prenatal treatment, is <30% | 281 (90%)* | 22 (7%) | 8(3%) |

| K3 | Non-randomized studies suggest that FETO improves survival in neonates with severe isolated left-sided CDH | 272 (87%)* | 14 (5%) | 25 (8%) |

| K4 | There is sufficient evidence from randomized controlled trial(s) that FETO improves survival in neonates with severe isolated left-sided CDH | 94 (30%) | 181 (58%)* | 36 (12%) |

| K5 | Delivery before 34 wk occurs in around 30% of the patients undergoing FETO | 208 (67%)* | 45 (14%) | 58 (19%) |

| K6 | For patients who underwent FETO, not staying close to a center offering emergency in utero balloon removal, increases the risks of neonatal death | 272 (88%)* | 22 (7%) | 17 (5%) |

| K7 | For patients who underwent FETO, the majority of tertiary care hospitals offer emergency in utero balloon removal | 94 (30%) | 175 (56%)* | 46 (14%) |

| K8 | In mid-trimester fetuses, one can reliably predict neonatal survival with isolated leftsided CDH | 139 (45%)* | 142 (45%) | 30 (10%) |

Note: Data are displayed as n(percentage)

was defined as the correct answer; n = 311 complete surveys.

Figure 1.

Knowledge score (range: 0-8) for professional categories [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2. Attitude

The first attitude statement (A1) polled the absolute increase in survival (%) respondents felt FETO should induce, to be considered as more effective than postnatal management. Options were 5%-10% (8%), 10%-30% (43%), 30%-50% (32%) or >50% (18%), with the answers between brackets. In other words, respondents were quite divided: 50% expected FETO to increase survival by 5%-30% whereas the others expected it to be more than 30%. The answers to the other attitude statements are displayed in Table 3. Nearly 60% (n = 186) of respondents agreed with the statement that the exact risks and benefits of FETO are unclear, hence were considered to be in equipoise. The vast majority (n = 219/311; 70%) acknowledges that not offering FETO to patients demanding it, is a psychological burden. Half of respondents were considered as proponents of an RCT (A7) (n = 161/311; 52%).

Table 3. Distribution of answers to the attitude statements.

| Statement: In my opinion, in severe CDH,… | I agree | I disagree | I do not know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2* | FETO is the only option for increasing neonatal survival rate | 166 (54%) | 82 (26%) | 63 (20%) |

| A3 | The effect of FETO is unclear: the exact benefits and risks for the fetus are still unknown | 186 (60%) | 102 (33%) | 23 (7%) |

| A4 | Doing no FETO is withholding a proven treatment option | 108 (35%) | 157 (50%) | 46 (15%) |

| A5 | Not offering FETO to parents who ask for it is a psychological burden for the prospective parents, as it seems as if no treatment is provided in a fetus with predicted poor outcome | 219 (70%) | 63 (20%) | 29 (9%) |

| A6 | Not offering FETO is giving the current standard of care | 109 (36%) | 169 (54%) | 33 (11%) |

| A7 | Offering FETO as part of an RCT, is the only option as there is no evidence on its efficacy. | 161 (52%) | 124 (40%) | 26 (8%) |

| A8 | Offering FETO only within an RCT is undesirable, as you are withholding a therapeutic option that may improve outcome. | 137 (44%) | 131 (42%) | 43 (14%) |

Note:Data are displayed as n(percentage);

the results of statement A1 are described in the results section; n = 311 complete surveys.

3.1. Relation to knowledge

To assess the correlation between knowledge and attitude, we analyzed individual knowledge scores of participants to certain attitude statements. Respondents who earlier stated they considered an increase of survival of less than 30% beneficial(A1), had a comparable knowledge score to that of those hoping for a more than 30% increase in survival (6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 157] vs 6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 154]; P = .221).

Statement A3 indicated that the exact benefits and risks of FETO are unclear and was purposely designed to assess participants whether they were in equipoise. Those who agreed with this statement, had a higher knowledge score (6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 186] vs 5.0 [4.5-5.5, n = 125]; P < .001).

Statement A7 and A8 were included to prompt a clear statement of respondents in which context FETO should be offered. Those who agreed with statement A7, hence were considered as proponents of offering FETO within an RCT, had a higher knowledge score (6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 161] vs 5.5 [5.0-6.0, n = 150]; P = .031). Similarly, those who disagreed with statement A8, and thus were also considered as supportive of FETO being offered within an RCT, scored higher than those who agreed with this statement (6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 131] vs 5.0 [4.5-5.5, n = 180]; P < .001). Of note is that 67% of proponents and 77% of opponents were consistent in their answers to both questions (NS).

Figure 2 displays the number of respondents, categorized as being a proponent or opponent of an RCT, providing right answers to the eight knowledge questions. The difference between proponents and opponents was most noticeable beyond the third knowledge question.

Figure 2.

Radar chart of percentage of participants with a correct answer per knowledge question [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3. Practice

Table 4 displays how participants manage their patients in a clinical setting. A minority of respondents do not see pregnant women carrying a fetus with CDH (n = 19; 6%) or do not assess severity nor counsel themselves (n = 38; 12%). Four out of five (n = 246/311; 79%) respondents assess and counsel patients on severity assessment. Of these, only half (n = 118/246; 48%) would refer or offer patients FETO within an RCT and a quarter (n = 69/246; 28%) on patient request. The remainder (n = 59/246; 24%) would leave the decision in the hands of a tertiary center or the parents.

Table 4. Practice of respondents when seeing a pregnant woman with a fetus with severe left sided isolated CDH.

| Statement: If I see a patient with a fetus with CDH™ | Number of participants (n = 311) |

|---|---|

| I assess severity and counsel, and if severe, I refer™ | 160 (52%) |

| …to a center which will offer FETO within an RCT | 81 (51%) |

| …to a center which will offer FETO on the request of the parents | 53 (33%) |

| …to a tertiary center, regardless of what way the patient will be managed antenatally | 26 (16%) |

| I assess severity and counsel, and if severe, I offer … | 86 (28%) |

| …FETO within an RCT | 33 (38%) |

| …FETO outside an RCT | 16 (19%) |

| …both options to parents | 37 (43%) |

| I do not assess severity nor counsel, I refer … | 38 (12%) |

| …to a center which will offer FETO | 6 (16%) |

| …to a center which offers FETO within an RCT | 7 (18%) |

| …to a center which will offer FETO on the request of the parents | 5 (13%) |

| …to a tertiary center, regardless of how the patient will be managed antenatally | 20 (53%) |

| I do not see patients with CDH | 19 (6%) |

| Other | 6 (2%) * |

Note: Data are displayed as n(percentage)

three participants would offer termination of pregnancy or refer the patient, one would offer neonatal care, t < o state they only perform assessment and counseling.

The last question queried the practice of respondents when parents insisted on having FETO. In that situation, 41% of respondents (n = 128/311) would offer or refer patients for this procedure. Only 25% (n = 79/311) stated they felt FETO should only be offered within an RCT. There were only seven respondents (2%) who would advise their patients against FETO, either in or outside an RCT. Of note is that one third of all respondents (31%; n = 97/311) had never been in this situation or did not have an opinion.

3.2. Relation to knowledge

Participants who were involved in the assessment of pregnant women carrying a fetus with CDH, had a higher knowledge score than those who did not (6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 246] vs 5.0 [4.0-6.0, n = 65]; P < .001). However, only half of the former (n = 122/246; 50%), agreed that one can reliably predict neonatal survival. Those only offering or referring patients to FETO within an RCT had a comparable knowledge score to those who do not 6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 118] vs 6.0 [5.0-7.0, n = 128]; P = .105).

3.3. Relation to attitude

How respondents manage patients clinically, is displayed in Figure 3. It displays their practice regarding referral for FETO, either as “within an RCT”, “per patient preference”, or “indifferent,” i.e. meaning the ultimate decision is only taken after consultation at the tertiary prenatal management center. Respondents managing patients based on severity (n = 246) (Table 4), and who are in equipoise (A3, n = 149), of those 54% (80/149) refer or offer FETO uniquely within an RCT and 23% (34/149) upon patient request. In 23% of cases, they would leave the decision in the hands of a tertiary center or parents. Conversely, those who disagreed with the equipoise statement (A3; n = 83), refer or offer FETO within an RCT in 36% (n = 30/83) and 39% on patient request (n = 32).

Figure 3.

Practice per attitude statement [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Respondents who consider “not offering FETO to parents who ask for it, as a psychological burden” (A5) (n = 176/246), followed patient preference for FETO in 32% (n = 57/176). Seventy-five respondents (43%) still referred patients for trial participation. Of those who disagree with the statement that not offering FETO is a psychological burden (A5; n = 49), 71% (n = 35/49) refer or offer FETO within an RCT and 14% (n = 7/49) on patient request.

Of the proponents of the RCT who assess patients (n = 124), 68% offer FETO within an RCT (n = 84/124) while 13% on patient request only (n = 26/124). In contrast, opponents (n = 104) refer or offer on patient request in 47% (n = 49/104) while 26% (n = 27/104) as participant of a trial. When using statement A8 to define the practice of opponents and proponents, practice was similar.

In summary, two-thirds of proponents offer FETO within an RCT and half of opponents offer FETO on patient request.

3.4. Poll

Table 5 displays the answers to the on-site poll prior and after the debate. Before, 15% of the respondents at the debate were of the opinion that FETO should be exclusively offered within the context of an RCT (n = 45/307). That percentage that went up to 39% after the debate.

Table 5. Answers to poll on offering FETO outside the research setting or exclusively in an RCT.

| Q1 Can one reliably predict outcome in mid-trimester fetuses with isolated left-sided CDH? | ||||

| A | B | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 138 | 43 | 85 | 45 |

| No | 125 | 39 | 82 | 43 |

| Impartial | 26 | 8 | 17 | 9 |

| I do not have the right knowledge to answer | 35 | 11 | 6 | 3 |

| 324 | 190 | |||

| Q2 Is there convincing evidence today that prenatal FETO improves survival in fetuses with isolated severe left-sided CDH? | ||||

| A | B | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 185 | 58 | 47 | 26 |

| No | 91 | 29 | 103 | 56 |

| Impartial | 27 | 9 | 27 | 15 |

| I do not have the right knowledge to answer | 14 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| 317 | 183 | |||

| Q3 Under the assumption one can reliably predict outcome in isolated severe left-sided CDH, one should today: | ||||

| A | B | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Offer FETO exclusively in an RCT | 45 | 15 | 72 | 39 |

| Offer FETO exclusively as therapeutic option | 83 | 27 | 24 | 13 |

| Offer FETO either in an RCT or as a therapeutic option | 145 | 47 | 78 | 43 |

| Not offer FETO at all | 13 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| I do not have the right knowledge to answer | 21 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| 307 | 183 | |||

| Q4 If parents insist on having FETO in their fetus with isolated severe CDH, one should offer the intervention: | ||||

| A | B | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 238 | 79 | 117 | 65 |

| No | 30 | 10 | 49 | 27 |

| Impartial | 15 | 5 | 10 | 6 |

| I do not have the right knowledge to answer | 18 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| 301 | 181 | |||

Note: A refers to presentation held by opponent of FETO exclusively in an RCT; B refers to presentation held by proponent of FETO exclusively in an RCT.

4. Discussion

We assessed the knowledge, attitude and practice of professionals to better understand the factors determining clinical equipoise with regards to the TOTAL trial. The majority of respondents was clinically involved in fetal medicine. They had a high level of knowledge on CDH and available treatment options; with fetal surgeons having more knowledge on the more procedural specific questions. Remarkably, 45% indicated they were not convinced that the outcome of fetuses with CDH can be reliably predicted prenatally. However, at the same time they express opinions on fetal therapy, with two thirds being in equipoise. The vast majority of respondents refers to the psychological burden on parents of not offering FETO on parental request, when prenatal assessment predicts poor outcome. The views and practice of respondents often differed, indicating that clinicians face personal and practical dilemmas undermining equipoise. Around 25% offers FETO on patient request.

According to the International Fetal Medicine and Surgery Society, accurate prenatal prediction of outcome is mandatory to consider fetal intervention. Though the vast majority of our respondents are professionals in clinical practice, half of them doubt prenatal prediction is possible for a fetus with CDH. This may suggest the fetal medicine community questions the accuracy of current assessment methods and prediction models. At the same time the vast majority of respondents seem to perceive CDH as a severe congenital malformation with overall poor outcome. When parents request fetal therapy, only 2% of respondents advise against it, which may indicate that the vast majority feels there is need for, and perhaps also that there is a potential benefit of interventions that improve the outcome. The latter suggests that the concept of fetal therapy is well known or at least to some extent accepted among respondents.

Though most participants were in equipoise, the translation into daily clinical practice is inconsistent. When facing mothers carrying a fetus with severe CDH, only half of respondents in equipoise, would refer or offer FETO within the context of an RCT. Our survey did not probe for the reasons for this apparent ambivalence, and we can only speculate about their reasons. One may be that respondents feel an RCT is not the optimal way to solve this question,41 given 35% of these respondents do not support the RCT. Clinicians may experience discomfort with randomly allocating pregnant patients or they might feel that prenatal therapy is superior to postnatal management.

Earlier studies show that clinicians experience “hunches” or “gut feeling,” steering them to prefer one treatment option.42,43 This personal bias is more pronounced when there is a delay in scientific evidence finding, which is the case with this trial.17 In the case of an unborn child with an a priori low chance of postnatal survival, this individual bias may be even stronger.42,44-46 This has earlier complicated the start of the TOTAL trial,15 as well as other trials in prenatal therapy.2,47 Another reason may be that in RCTs, in particular those involving potentially life-saving treatments, randomization may be considered as denying access to the potential benefits of the novel intervention and taking away the parents’ last hope.48 The high percentage of respondents indicating that not offering FETO on parental request is a psychological burden to prospective parents, supports this. As FETO is not “new,” parents may have found information through various channels, and developed their own bias and are desperate for a potential life-saving intervention for their unborn child.

These reasons may challenge the equipoise throughout a long-lasting fetal treatment trial, but should not discourage researchers to design and execute fetal treatment trials in the future. Offering a therapy upon parental request, with a low but tangible risk for maternal complications,49 and known fetal risks,24,50,51 may not be in the patient’s best interest.32 An RCT should protect patients from potential harm and concurs with the principle of non-maleficence,52,53 as well as providing future patients with high quality evidence on the preferred treatment. In situations in which parents have to make decisions with potentially far-reaching consequences for their unborn child, this is essential.

Remarkably, one third of respondents considered to be not in equipoise, still refers or offers FETO within an RCT. Also, a quarter of the opponents to an RCT, still refers or offers for trial participation. Again, we can only speculate about those respondents’ motivations. Maybe they feel peer pressure, fear being accused of functioning as a back door, or they simply want to contribute to the quest for best evidence even if individual equipoise is lost.42 Also, there may be no local access to FETO outside the context of an RCT. Our observation that many specialists attending a debate on equipoise on this matter, change their mind after hearing the arguments for an RCT, probably underscores their ambivalence to this matter.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge several weaknesses to our study. First, the response rate was less than desirable. Second, one out of three respondents starting the questionnaire did not complete it. There might be several reasons for that. One explanation may be that the questionnaire was too complex and answering too time consuming. However, this seems unlikely, as almost half (44%) did not proceed beyond the demographic questions. We could also have insisted more by sending more reminders, or have provided respondents an incentive. Third, respondents may not be representative of the “larger community.” We first advertised the survey at the end of the debate. Three out of four respondents indeed attended the debate, so that we assume that this successfully sparked attendees’ interest, but in this group, centers participating to the TOTAL may be overrepresented. Due to the anonymous character of the study, we cannot determine from which center the participants originated. Fourth, logistic restrictions (eg, patient’s inability to travel) or regional availability of FETO has not been queried and may affect practice. Fifth, participants were invited after the debate, which may have altered their opinions. Sixth, to assess knowledge, we arbitrarily created an unprecedented scale to score knowledge from 0-8, and we weighed all knowledge questions equally.

Despite, this study also has its strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the knowledge, opinions and practice of professionals in maternal-fetal medicine regarding fetal therapy for CDH and an ongoing RCT. Second, we collected 311 completed surveys, over 80% of these by professionals involved in fetal medicine. Three out of four had more than 6 years of experience and two out of three were involved in research in fetal medicine. We consider them as relevant and representative for the clinicians patients see. This study therefore provides accurate insight regarding the knowledge, attitudes and practice of these specialists on a topic under debate.

5. Conclusion

Surveyed specialists were divided on whether FETO for severe left sided CDH should be offered exclusively within a randomized control trial or upon request of parents. The findings of this study indicate a tension between the clinical and scientific obligations of fetal medicine specialists when dealing with patients eligible for an RCT. While equipoise should be their guidance, apparently for many clinicians this situation evokes personal and practical dilemmas. This may also affect the successful execution of future fetal therapy trials.

Supplementary Material

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

What is already known about this topic?

In fetal medicine, it has been quite difficult to successfully run randomized clinical trials (RCT).

Equipoise is a prerequisite for executing any RCT..

The RCT investigating the role of fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (FETO) in fetuses with severe Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) also has met significant resistance.

What does this study add?

We conducted a knowledge, attitude and practice-survey among fetal medicine specialists on the antenatal management of CDH.

Half of respondents thinks that outcome in CDH cannot be predicted reliably, though still consider fetal therapy.

Half of respondents support the concept of an RCT but 70% feel that not offering FETO on parental request is a psychological burden.

Ambivalence to a randomized trial and the perceived psychological burden determines clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof Kypros Nicolaides for the opportunity to poll attendees of the 18th World Congress on Fetal Medicine (June 2019, Alicante, Spain). JDP is funded by the Great Ormond Street Hospital Charity. JDP and NC are part-time funded by Wellcome Trust/ Gift surg.

Funding information

Wellcome Trust; Wellcome Trust/Gift surg; Great Ormond Street Hospital Charity

Footnotes

Conflict Of Interest

Prof Deprest reports being principal investigator of the TOTAL trial (University Hospitals Leuven). Prof Dierickx reports being member of the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee of the TOTAL trial (University Hospitals Leuven).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1.Morris RK, Malin GL, Quinlan-Jones E, et al. Percutaneous vesicoamniotic shunting in Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction (PLUTO) Collaborative Group. Percutaneous vesicoamniotic shunting versus conservative management for fetal lower urinary tract obstruction (PLUTO): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1496–1506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60992-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Mieghem T, Ryan G. The PLUTO trial: a missed opportunity. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1471–1473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ameis D, Khoshgoo N, Keijzer R. Abnormal lung development in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2017;26(3):123–128. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgos CM, Frenckner B, Luco M, et al. Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group Prenatally versus postnatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia - Side, stage, and outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(4):651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallot D, Boda C, Ughetto S, et al. Prenatal detection and outcome of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a French registry-based study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(3):276–283. doi: 10.1002/uog.3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo FM, Cordier AG, De Catte L, et al. ERNICA European reference network. Proposal for standardized prenatal ultrasound assessment of the fetus with congenital diaphragmatic hernia by the European reference network on rare inherited and congenital anomalies (ERNICA) Prenatal Diagn. 2018;38(9):629–637. doi: 10.1002/pd.5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo FM, De Coppi P, Allegaert K, et al. Current and future antenatal management of isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;22(6):383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jani J, Nicolaides KH, Keller RL, et al. on behalf of the Antenatal-CDH-Registry Group Observed to expected lung area to head circumference ratio in the prediction of survival in fetuses with isolated diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(1):67–71. doi: 10.1002/uog.4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deprest J, Gratacos E, Nicolaides KH. Fetoscopic tracheal occlusion (FETO) for severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia: evolution of a technique and preliminary results. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24(2):121–126. doi: 10.1002/uog.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peralta CFA, Sbragia L, Bennini JR, et al. Fetoscopic endotracheal occlusion for severe isolated diaphragmatic hernia: initial experience from a single clinic in Brazil. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;29(1):71–77. doi: 10.1159/000314617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jani JC, Benachi A, Nicolaides KH, et al. the Antenatal-CDH-Registry group. Prenatal prediction of neonatal morbidity in survivors with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a multicenter study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33(1):64–69. doi: 10.1002/uog.6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Maary J, Eastwood MP, Russo FM, Deprest JA, Keijzer R. Fetal tracheal occlusion for severe pulmonary hypoplasia in isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of survival. Ann Surg. 2016;264(6):929–933. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grivell RM, Andersen C, Dodd JM. Prenatal interventions for congenital diaphragmatic hernia for improving outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;27(11):CD008925. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008925.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TOTAL-trial. [Accessed May 2020]. [Internet]. www.TOTALtrial.eu.

- 15.Rodrigues HCML, Deprest J, Berg PPVD. When referring physicians and researchers disagree on equipoise: the TOTAL trial experience. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31(6):589–594. doi: 10.1002/pd.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman B. Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(3):141–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707163170304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basurto D, Russo FM, Van der Veeken L, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;58:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fetal Medicine Foundation. World Congress in Fetal Medicine. [Accessed March 2020, Cited March 23, 2020]. [Internet]. https://fetalmedicine.org/var/uploads/18thWCFMprogram.pdf.

- 19.Deprest J. Prenatal treatment of severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia: there is still medical equipoise. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56(4):493–497. doi: 10.1002/uog.22182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ville Y. Should we offer fetal surgery for severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia or bring those cases to trial? The difference between chance and hazard. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56(4):491–492. doi: 10.1002/uog.22103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Limotai C, Manmen T, Urai K, Limarun C. A survey of epilepsy knowledge, attitudes and practice in school-aged children in Bangkok, Thailand. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;137(1):38–43. doi: 10.1111/ane.12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinivasan NK, John D, Rebekah G, Kujur ES, Paul P, John SS. Diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: knowledge, attitude, practice (KAP) among diabetic patients in a tertiary eye care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(7):NC01–NC07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/27027.10174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control A guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. World Health Organisation; [Accessed May 2019]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43790.2008 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jani JC, Nicolaides KH, Gratacós E, et al. Severe diaphragmatic hernia treated by fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(3):304–310. doi: 10.1002/uog.6450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jani J, Gratacós E, Greenough A, et al. FETO Task Group. Percutaneous fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion (FETO) for severe left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(4):910–922. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000184774.02793.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jani J, Nicolaides KH, Benachi A, et al. Timing of lung size assessment in the prediction of survival in fetuses with diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31(1):37–40. doi: 10.1002/uog.5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruano R, Yoshisaki CT, Da Silva MM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion versus postnatal management of severe isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39(1):20–27. doi: 10.1002/uog.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeKoninck P, Gratacos E, Van Mieghem T, et al. Results of fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion for congenital diaphragmatic hernia and the set up of the randomized controlled TOTAL trial. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87(9):619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigues HCML, van den Berg PP. Randomized controlled trials of maternal-fetal surgery: a challenge to clinical equipoise. Bioethics. 2014;28(8):405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2012.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Ethics of maternal-fetal surgery. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12(6):426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. Ethics of fetal surgery. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36(2):237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allmark PJ, Mason S. Should desperate volunteers be included in randomised controlled trials? J Med Ethics. 2006;32(9):548–553. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braakhekke M, Mol F, Mastenbroek S, Mol BWJ, van der Veen F. Equipoise and the RCT. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):257–260. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller FG, Joffe S. The Ethical Challenges of Human Research. Oxford University Press; Oxford, United Kingdom: 2015. Equipoise and the Dilemma of Randomized Clinical Trials; pp. 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joffe S, Miller FG. Equipoise: asking the right questions for clinical trial design. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(4):230–235. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snowdon C, Garcia J, Elbourne D. Making sense of randomization; responses of parents of critically ill babies to random allocation of treatment in a clinical trial. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(9):1337–1355. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuhaus CP, Zacharias RL. Compassionate use of gene therapies in pediatrics: an ethical analysis. Semin Perinatol. 2018;42(8):508–514. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brierley J, Larcher V. Compassionate and innovative treatments in children: a proposal for an ethical framework. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(9):651–654. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.155317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fowler FJ. Survey Research Methods. 5th ed Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA, United States: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Focus on research methods: is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459–467. doi: 10.1002/nur.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odibo AO, Acharya G. External validity in perinatal research. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(4):424–428. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donovan JL, De Salis I, Toerien M, Paramasivan S, Hamdy FC, Blazeby JM. The intellectual challenges and emotional consequences of equipoise contributed to the fragility of recruitment in six randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(8):912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donovan JL, Paramasivan S, de Salis I, Toerien M. Clear obstacles and hidden challenges: understanding recruiter perspectives in six pragmatic randomised controlled trials. Trials. 2014;15:5. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rooshenas L, Elliott D, Wade J, et al. POUT study group. Conveying equipoise during recruitment for clinical trials: qualitative synthesis of clinicians’ practices across six randomised controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor KM, Margolese RG, Soskolne CL. Physicians’ reasons for not entering eligible patients in a randomized clinical trial of surgery for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(21):1363–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405243102106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaguelidou F, Amiel P, Blachier A, et al. Recruitment in pediatric clinical research was influenced by study characteristics and pediatricians’ perceptions: a multicenter survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(10):1151–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crombleholme TM, Shera D, Lee H, et al. A prospective, randomized, multicenter trial of amnioreduction vs selective fetoscopic laser photocoagulation for the treatment of severe twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):396.e1–396.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colli A, Pagliaro L, Duca P. The ethical problem of randomization. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9(7):799–804. doi: 10.1007/s11739-014-1118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sacco A, Van der Veeken L, Bagshaw E, et al. Maternal complications following open and fetoscopic fetal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prenat Diagn. 2019;39(4):251–268. doi: 10.1002/pd.5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larroque B, Bréart G, Kaminski M, et al. Epipage stusy group. Survival of very preterm infants: epipage, a population based cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(2):F139–F144. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.020396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Natarajan G, Shankaran S. Short-and long-term outcomes of moderate and late preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33(3):305–317. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1571150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joffe S, Miller FG. Bench to bedside: mapping the moral terrain of clinical research. Hastings Cent Rep. 2008;38(2):30–42. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2008.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed Oxford University Press; Oxford, United Kingdom: 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.