Abstract

Objective

To investigate the efficacy and safety of the ‘smart’ tracheal occlusion (Smart-TO) device in fetal lambs with diaphragmatic hernia (DH).

Methods

DH was created in fetal lambs on gestational day 70 (term, 145 days). Fetuses were allocated to either pregnancy continuation until term (DH group) or fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (TO), performed using the Smart-TO balloon on gestational day 97 (DH + TO group). On gestational day 116, the presence of the balloon was confirmed on ultrasound, then the ewe was walked around a 3.0-Tesla magnetic resonance scanner for balloon deflation, which was confirmed by ultrasound immediately afterwards. At term, euthanasia was performed and the fetus retrieved. Efficacy of occlusion was assessed by the lung-to-body-weight ratio (LBWR) and lung morphometry. Safety parameters included tracheal side effects assessed by morphometry and balloon location after deflation. The unoccluded DH lambs served as a comparator.

Results

Six fetuses were included in the DH group and seven in the DH + TO group. All balloons deflated successfully and were expelled spontaneously from the airways. In the DH + TO group, in comparison to controls, the LBWR at birth was significantly higher (1.90 (interquartile range (IQR), 1.43–2.55) vs 1.07 (IQR, 0.93–1.46); P=0.005), while on lung morphometry, the alveolar size was significantly increased (mean linear intercept, 47.5 (IQR, 45.6–48.1) vs 41.9 (IQR, 38.8–46.1) μm; P = 0.03); whereas airway complexity was lower (mean terminal bronchiolar density, 1.56 (IQR, 1.0–1.81) vs 2.23 (IQR, 2.14–2.40)br/mm2; P = 0.005). Tracheal changes on histology were minimal in both groups, but more noticeable in fetal lambs that underwent TO than in unoccluded lambs (tracheal score, 2 (IQR, 1–3) vs 0 (0–1); P = 0.03).

Conclusions

In fetal lambs with DH, TO using the Smart-TO balloon is effective and safe. Occlusion can be reversed non-invasively and the deflated intact balloon expelled spontaneously from the fetal upper airways. © 2020 International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology

Keywords: congenital diaphragmatic hernia, efficacy, FETO, lamb, magnetic resonance, prenatal therapy, safety, sheep, trachea, unplug

Introduction

Mortality in congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) remains at around 30%, despite the implementation of standardized protocols for the postnatal management of such cases1. CDH patients die mainly from lung hypoplasia2. Fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (FETO) is an investigational therapy that can stimulate fetal lung growth3, and thus has the potential to improve survival and early neonatal morbidity in CDH4–7.

One of the drawbacks of the current tracheal occlusion (TO) procedure is the need for a second invasive intervention to re-establish airway patency (unplugging)8. This is done preferentially before delivery, to stimulate lung maturation6,8,9. Unplugging is currently performed by fetoscopy, ultrasound-guided puncture, placental circulation or by postnatal puncture9,10. In-utero reversal of TO is an additional invasive procedure that adds to the fetal and maternal risks. Moreover, reversal of the occlusion may be challenging, as shown in a recent study in which balloon removal attempted at non-FETO centers was unsuccessful in 30% of cases, leading to neonatal death9. Because the need for unplugging presents as an emergency in 25% cases, an experienced team needs to be available at all times. It is recommended therefore that the patient stays close to the FETO center while the fetus has the balloon in place9. All these factors could eventually limit the acceptability of FETO.

The University of Strasbourg developed an alternative occlusion device, referred to as ‘smart’ tracheal occlusion (Smart-TO) (BS-MTI, Niederroedern, France)11. This balloon has a magnetic valve which opens under the influence of the magnetic field present around any magnetic resonance (MR) scanner (Figure 1). Prior preclinical experiments demonstrated that, in a simulated in-utero environment, deflation of the balloon was successful in different fetal and maternal positions, with need for exposure to a 3.0-Tesla (i.e. stronger) MR scanner in some cases12. The feasibility of insertion and deflation of the Smart-TO balloon was demonstrated in vivo in rhesus monkeys11. Subsequently, the short-term tracheopulmonary effects of Smart-TO were investigated in fetal lambs, demonstrating lung growth and acute histological tracheal changes that were similar to those induced by standard Goldbal2 balloon12. Those experiments were done in lambs without pulmonary hypoplasia and the effects were measured immediately after reversal of 3 weeks of occlusion; however, the fate of the balloon after deflation was not documented.

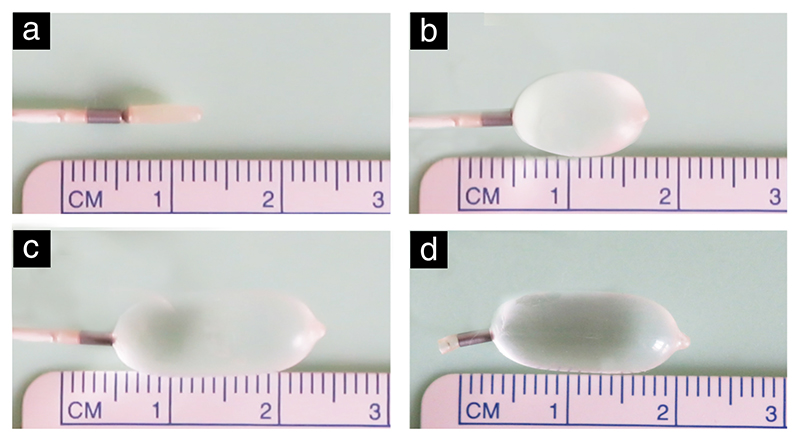

Figure 1. The Smart-TO balloon in its different states: (a) deflated; (b) inflating; (c) inflated; (d) detached.

Herein, we occluded the trachea of lambs with pulmonary hypoplasia using the Smart-TO balloon, reversed the occlusion after 3 weeks and observed the animals until term. We hypothesize that in lambs with diaphragmatic hernia (DH), TO with the Smart-TO balloon will induce a significant increase in lung size compared to internal hypoplastic controls.

Materials And Methods

Experimental balloon

The Smart-TO balloon has been described in detail previously11. Briefly, this latex balloon has a magnetic valve (Figure 1), composed of a magnetic ball and a metallic ring. The metallic components are parylene coated for biocompatibility, a technique used widely in medical devices. The magnetic ball can move freely inside the balloon, though due to the magnetic attraction it is typically against the metallic cylinder, hence acting as a valve. When exposed to a strong external magnetic field, the magnetic interaction between the ball and cylinder is released and the valve opens.

Animals and procedures

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of the Faculty of Medicine, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium (P010/2018). The guidelines of the Animal Research: Reporting of In-Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE)13 and SmartTots preclinical working group14 were followed. We used the fetal DH lamb model and in-utero TO procedure, both of which have been previously described in detail (Appendix S1)15,16. Briefly, time-dated pregnant Swifter ewes underwent fetal DH induction (one fetus per ewe) on gestational day70 ± 1 (term, 145 days). Following maternal midline laparotomy and hysterotomy, the fetal chest was exposed and incised at the tenth intercostal space. A small segment of the fetal diaphragm was excised, and two stomachs were ascended into the thorax through the defect. After recovery from anesthesia, the ewe was returned to an individual stable, and 48 h later, abdominal ultrasound was performed using a Voluson E10 ultrasound machine (GE Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) in order to assess fetal viability. Fetuses were allocated to either pregnancy continuation until term (DH group) or TO using the experimental balloon (DH + TO group) on gestational day 97 ± 1. During TO, the Smart-TO balloon was inflated and detached at the tenth ring distal to the vocal cords to ensure the exact location of the balloon within the trachea. On gestational day 116, the presence of the balloon was assessed by ultrasound (Figure S1b) and, immediately afterwards, balloon deflation was performed by walking the ewe once around a 3.0-T MR scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens, Germany). This was followed by a second ultrasound assessment to confirm balloon deflation, evidenced by the absence of the typical filled contour of the balloon10 (Figure S1d). Both the DH-induction and TO procedures were performed under a standardized clinical anesthesia protocol (Appendix S1).

At term, the ewe and fetus were euthanized, and the lambs were delivered by postmortem Cesarean section and weighed (Appendix S1). At obduction, the exact location of the deflated balloon was assessed. First, the amniotic cavity was inspected, and if the deflated balloon was not found, the lamb underwent a scout-view X-ray (OEC Fluorostar 700 COMPACT PLUS2; GE Healthcare) to locate the balloon within its body (Figure S1e). The Smart-TO balloons were checked to ensure that all components (balloon, magnetic ball and metallic ring) were present and intact. The lambs underwent standardized obduction, during which we first evaluated the presence of herniated viscera inside the thorax. Animals without a defect and stomach and bowel into the chest were excluded from the analysis17, because hypoplasia may not have been severe. The trachea and lungs were harvested, separated, and the lung-to-body-weight ratio (LBWR) was calculated18. Lungs were pressure-fixed and underwent morphometry, as previously described18 (Appendix S1, Figure S2). The trachea was inspected grossly for the presence of deformation (Figure S3) and transverse tracheal sections were obtained at the level of the plug, at least 1 cm above and at least 1 cm below. In DH lambs without TO, sections were collected at the tenth ring from the vocal cords (middle), 1-cm proximal to the middle section (above) and 1-cm distal (below). All sections were processed as described before14. On fixed specimens, the tracheal circumference was measured (Figure S4), and histological tracheal changes were scored by an experienced pathologist, blinded to the study groups, using a hierarchical scoring system of all anatomical elements (Table S1)12,19.

Statistical analysis

This study was conceived as a superiority study. We assumed that the Smart-TO would induce an increase in LBWR of at least 30% compared with the unoccluded DH lambs20. We calculated that six animals per group would be needed in order to provide a power of ≥ 90% with a two-sided type-1 error of 5%, using 2012 Power calculator (Sealed Envelope Ltd., London, UK) for a continuous outcome superiority trial21. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism for macOS V.8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Continuous measures are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) and comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Dichotomous measures are expressed as n (%). A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

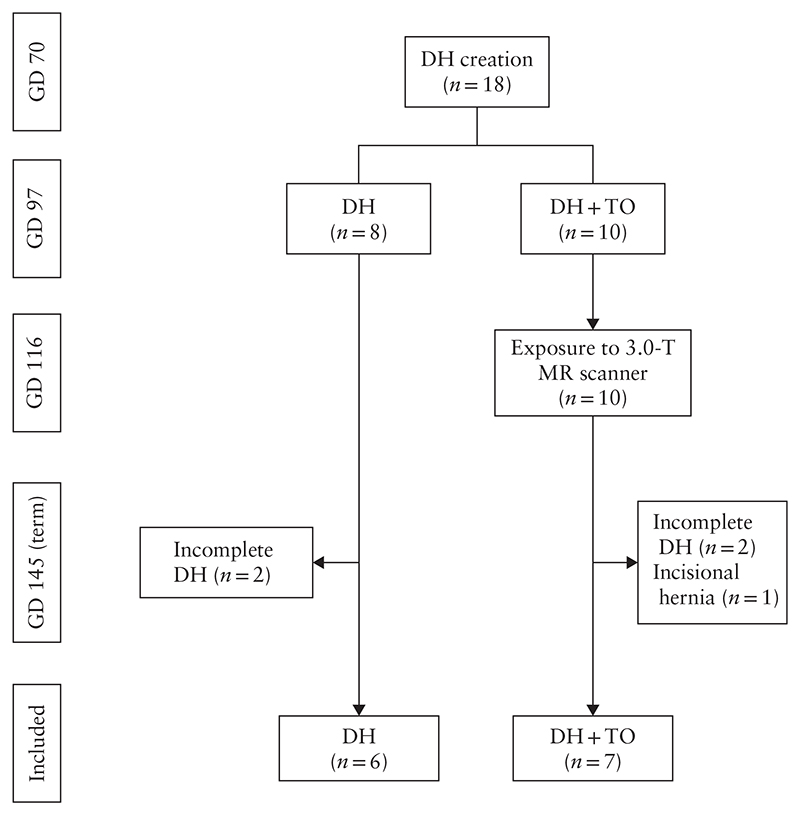

A total of 18 fetuses underwent DH induction and survived until term (Figure 2). At obduction, we identified four lambs (two in each group) in which the defect had partly healed. One further lamb in the DH + TO group had an incisional hernia in the thoracic wall, through which the stomach herniated. These five fetuses were excluded from further analysis, leaving six fetuses in the DH group and seven in the DH + TO group.

Figure 2.

Flowchart summarizing in-vivo experiments in fetal lambs included in study. DH, diaphragmatic hernia; GD, gestational day; MR, magnetic resonance; TO, tracheal occlusion with Smart-TO balloon.

All Smart-TO balloons (n=7) were present and appeared inflated by gestational day 116. They all deflated successfully after MR exposure of the ewe and were later found outside the airways. Two (29%) were in the amniotic cavity, two (29%) inside the stomach and three (42%) within the sigmoid of the fetus.

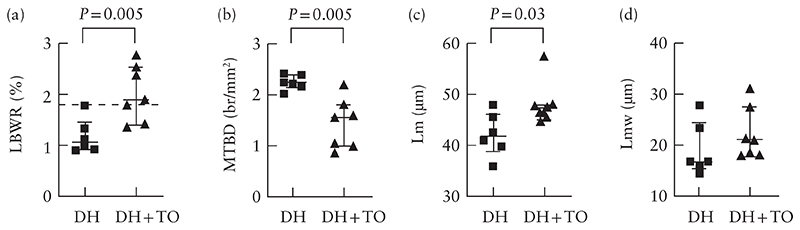

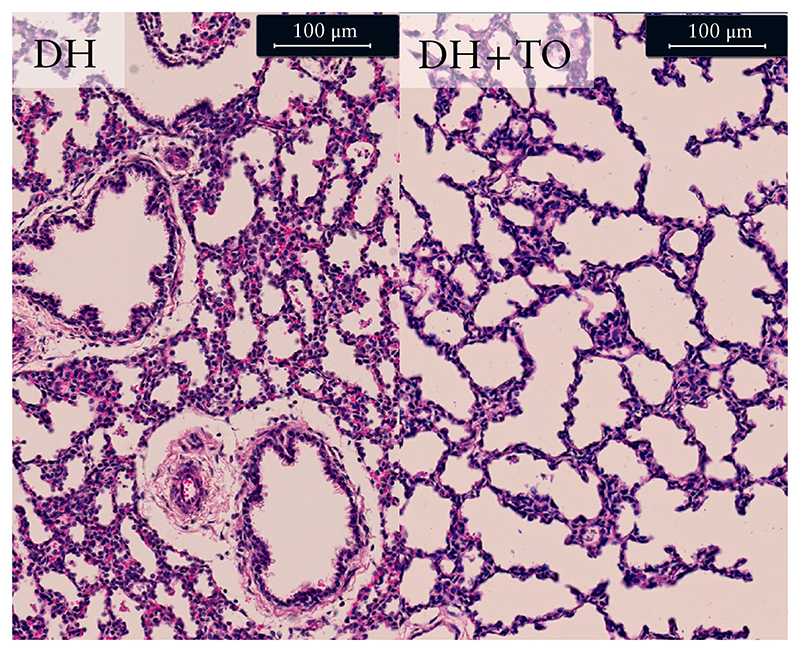

The LBWR was significantly higher in the DH + TO lambs than in the DH lambs (1.90 (IQR, 1.43–2.55) vs 1.07 (IQR, 0.93–1.46); P = 0.005) (Figure 3a). On lung morphometry, DH + TO fetuses, compared with DH fetuses, had lower mean terminal bronchiolar density (1.56 (IQR, 1.0–1.81) vs 2.23 (IQR, 2.14–2.40) br/mm2; P = 0.005), increased alveolar size (mean linear intercept, 47.5 (IQR, 45.6–48.1) vs 41.9 (IQR, 38.8–46.1) μm; P = 0.03), and comparable alveolar septal thickness (mean trans-sectional wall length, 21.1 (IQR, 18.1–27.7) vs 16.8 (IQR, 15.5–24.6) μm; P = 0.18) (Table S2 and Figures 3b–d and 4).

Figure 3.

Lung-to-body-weight ratio (LBWR) (a), mean terminal bronchial density (MTBD) (b), mean linear intercept (Lm) (c) and mean trans-sectional wall length (Lmw) (d) in unoccluded fetal lambs with diaphragmatic hernia (DH) and fetal lambs with DH that underwent fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion with Smart-TO balloon (DH + TO). Bars indicate median and interquartile range. Dashed line in (a) represents normal controls based on Bratu et al.20. Significant P-values are reported.

Figure 4.

Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showing lung parenchyma of unoccluded fetal lambs with diaphragmatic hernia (DH) and fetal lambs with DH that underwent fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion with Smart-TO balloon (DH + TO).

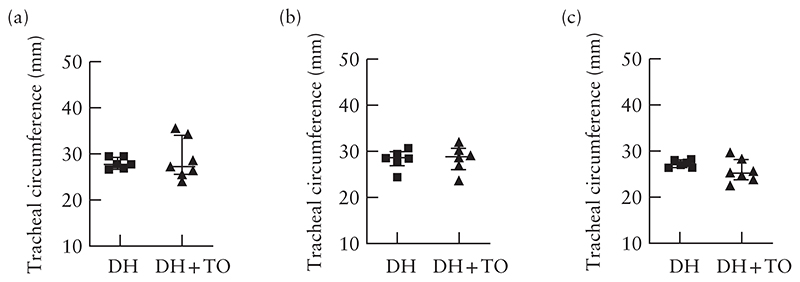

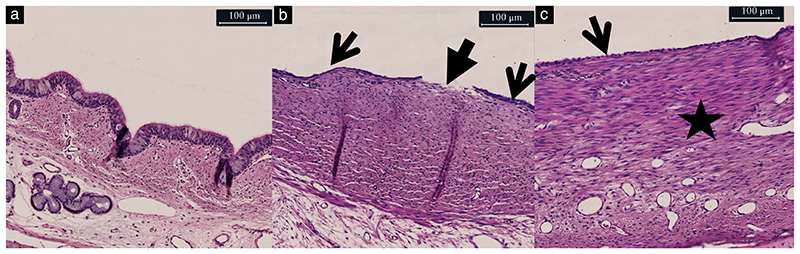

On gross inspection of the trachea, in all but one case, it was difficult to tell where the endoluminal balloon had been positioned inside the trachea. In one case, there was a prominent wider part in the trachea, with more stretched and transparent tissue between the rings and in the pars membranacea, with the contour of a balloon (Figure S3). There was no measurable difference in the tracheal circumference at, above or below the balloon level between the two groups (Figure 5). Histological changes at the level of the plug were minimal. The overall histological tracheal score was significantly higher in DH + TO than in unoccluded lambs, though both were in the low range (2 (IQR, 1–3) vs 0 (0–1); P = 0.03) (Table 1). Changes were mainly confined to the epithelium and involved unfolding or loss of integrity (Figure 6). Changes in the submucosal tissue were observed in one Smart-TO lamb, showing chronic inflammatory changes in less than 25% of the surface of the tracheal section (Figure 6c). All other tracheas had a normal pars membranacea and cartilage.

Figure 5.

Circumference of trachea at (a), above (b) and below (c) balloon level in fetal lambs with diaphragmatic hernia (DH) that underwent fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion with Smart-TO balloon (DH + TO) and at equivalent defined points in unoccluded DH lambs. Bars indicate median and interquartile range.

Table 1. Summary of histological tracheal scores in fetal lambs with diaphragmatic hernia (DH) that did not undergo occlusion and those with DH that underwent fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion with Smart-TO balloon (DH + TO).

| Score | At plug | Above plug | Below plug | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DH + TO (n = 7) |

DH (n = 6) |

DH + TO (n = 6)* |

DH (n = 6) |

DH + TO (n=7) |

DH (n = 6) |

|

| Epithelium | ||||||

| Loss of integrity | ||||||

| 0 | 5 (71) | 4 (67) | 5 (83) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| 1 | 1 (14) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Loss of cilia (quality) | ||||||

| 0 | 7 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unfolding | ||||||

| 0 | 1 (14) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 4 (57) | 6 (100) |

| 1 | 2 (29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 4 (57) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Submucosa Acute inflammation | ||||||

| 0 | 7 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic inflammation | ||||||

| 0 | 6 (86) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| 1 | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Granulomatous reaction | ||||||

| 0 | 7 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| ≥1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cartilage Viability | ||||||

| 0 | 7 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pars membranacea Ruptured | ||||||

| 0 | 7 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total score | ||||||

| 0–20 | 2 (1–3) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) |

Data are given as n (%) or median (interquartile range). *In one case, balloon was placed just below vocal cords, hence there is no sample above plug.

Figure 6.

Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of trachea in untreated fetal lamb (a) and in fetal lambs that underwent fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion with Smart-TO balloon (b,c), showing: (a) normal tracheal section; (b) loss of epithelial integrity (closed arrow) and of epithelial folding (arrows); and (c) loss of epithelial folding (arrow) and presence of chronic inflammatory reaction (star).

There were minimal epithelial changes above and below the plug in both groups, with normally appearing pars membranacea and cartilage (Table 1). The overall histological score above the plug in the DH + TO group (0 (IQR, 0.0–0.0)) was comparable with that in the unoccluded DH lambs (0 (IQR, 0.0–0.0); P > 0.99). The overall histological score below the plug was 0 (IQR, 0.0–1.0) in DH + TO lambs and 0 (IQR, 0.0–0.0) in the DH lambs (P = 0.19) (Table 1).

Discussion

Principal findings

We have demonstrated that TO using the Smart-TO balloon reverses effectively pulmonary hypoplasia after 3 weeks in the lamb model, is spontaneously expelled out of the fetal respiratory tract and does not leave obvious tracheal damage on histology.

The goal of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of the Smart-TO balloon. First, we found that the Smart-TO balloon reverses lung hypoplasia in DH lambs after 3 weeks, resulting in lungs that have similar weight to those of normal lambs20. This was evidenced by an increase in proportional lung weight and increased airway complexity, in line with previous studies12. Only alveolar wall thickness was similar to that in DH lambs, though this has been shown to be overcome by steroid administration22. This is also given clinically to FETO patients at the time of unplugging. Second, we tested whether the Smart-TO balloon would deflate when exposed to the magnetic field of a 3.0-T MR scanner and whether it would be expelled spontaneously. We simulated clinical conditions and walked the ewe around a 3-T MR scanner. In all cases, the balloon was deflated after a single MR exposure, and by the time of birth, it was found intact and outside the fetal airways, either in the fetal gastrointestinal (GI) tract or the amniotic cavity. We used the same methods as in previous studies12,19 to document the histological tracheal appearance after term birth. We observed minimal epithelial and submucosal changes, which were similar to those reported previously for a TO device19 and for the Smart-TO balloon12. There was no damage to the cartilage or the pars membranacea; however, there was a recognizable widening of the trachea in one fetus. This finding is no different from that described previously for the standard balloon12,19.

Clinical implications

Occlusion using the Smart-TO balloon reversed effectively lung hypoplasia in DH lambs, as evidenced by an increase in LBWR and airway complexity12,22,23. Based on these findings and those of our previous study comparing the Smart-TO balloon with the Goldbal2 balloon currently used in clinical practice12, and given that both devices are made of the same material and have similar dimensions when inflated, the effects of Smart-TO balloon should be comparable to those of Goldbal2 balloon when used clinically. The Smart-TO also had comparable local effects on the trachea, based on findings in our earlier study12. Similar to the Goldbal2 balloon, it may induce clinically local side effects referred to as tracheomegaly24,25, which usually has little clinical impact apart from a barking cough on effort, that decreases over time25,26. More severe effects have been reported occasionally, though they might be caused by difficulties during removal or in cases of insertion in early gestation26,27.

In current practice, after puncturing the Goldbal2 balloon under ultrasound guidance, it is usually found outside the airways, either in the amniotic fluid or the GI tract. The spontaneous migration of the balloon may be explained by a spontaneous outflow of the fluid accumulated under the balloon and fluid exiting during fetal breathing movements28. In a previous study, in which the lambs were euthanized prior to reversal of the occlusion, four out of the five smart-TO balloons were no longer in the airways after delivery12. In the present study, all balloons were found either in the GI tract or the amniotic fluid. This suggests that fetal breathing movements contribute to the expulsion of the balloon out of the airways.

If the balloon is ingested, the event should be considered equivalent to the accidental ingestion of a magnetic object by a small child, which is considered innocuous and managed expectantly29,30. Guidelines also state that when a magnet is ingested together with another metallic object, tissue may get trapped in between, and in that case, should be managed actively. This, however, does not apply here as the balloon remains intact, hence preventing entrapment.

Therefore, the fate of the deflated balloon is to move from the pharynx to either the GI tract, followed by spontaneous expulsion, or to the amniotic fluid. From there, it should be expelled during delivery. During Cesarean section, precautions for fluid suction will need to be taken. A residual Smart-TO should be identifiable on a plain X-ray11. Based on our observation of successful deflation, when using a 3.0-T MR scanner, and expulsion, clinical use of the Smart-TO balloon would obviate the need for a second intervention and staying close to the FETO center.

Research implications

We suggest moving now to a first-in-woman clinical study to demonstrate successful prenatal deflation of the balloon in clinical circumstances. Lung response, tracheal side effects and neonatal outcomes are interesting secondary readouts.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are, first, that it simulated clinical conditions of FETO and imaging methods for reversal of the occlusion (MR), as well as its documentation (ultrasound) at the time of reversal. Second, we used the well-documented DH fetal-lamb model and standardized readouts12,18,19, and the experienced pathologist was blinded to group assignment. Third, we allowed the ewe to continue the pregnancy until term, thus we were able to study the tracheopulmonary effects of the balloon at term. This way, the fetus had time to expel the balloon and we documented the location and integrity of the balloon at birth.

We acknowledge some potential limitations. First, we used a 3.0T-MR, based on our earlier experimental findings. The magnetic field of that scanner is stronger than the 1.5T-MR hardware that is more widely available. Therefore, we do not know how effective exposure to a 1.5T-MR would be; though in previous studies, reversal was also obtained effectively in nearly all cases11,12. Second, we documented reversal of the occlusion only by ultrasound and not by fetoscopic visualization, therefore, the airways may not have been patent immediately. Moreover, we did not document when the balloon was expelled. However, this study was designed to assess effects at term and to simulate the clinical scenario. Third, we included a small number of animals. Even though the study was powered sufficiently for the primary goal, and the numbers are in line with previous lamb studies, nevertheless, we acknowledge that for safety aspects, the number may be considered limited. We also excluded five fetuses that did not have a diaphragmatic defect at term. We did so because those animals may not have developed pulmonary hypoplasia17, making interpretation of the primary outcome measure (LBWR) difficult.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated, in the fetal lamb model, that TO using the Smart-TO balloon can rescue effectively pulmonary hypoplasia induced by DH. Additionally, we have shown that exposure of the subject to the external fringe field of a 3.0T-MR reverses effectively the occlusion, and the intact balloon is spontaneously expelled out of the airways. Lastly, there are no relevant adverse effects on the tracheal wall.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the G-PURE laboratory technicians Sofie Jannes and Katrien Luyten for their assistance in the histological processing of samples. We thank Rosita Kinnart and Elina Ghijsens from the Center for Surgical Technologies, Leuven, Belgium for their help with manipulation of animals.

D.B. and L.V.d.V. are funded by the Erasmus + Programme of the European Union (Framework Agreement number: 2013-0040). This publication reflects the views only of the authors and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. T.B. is funded by the Society for Anesthesia and Resuscitation of Belgium (SARB) and by the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association (OAA) International. F.M.R. is supported by the KU Leuven (Internal Funds KU Leuven, Post-Doctoral Mandate 18/215). I.V. is funded from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant (Agreement No 765274). J.D. is funded by the Great Ormond Street Hospital Charity Fund. L.J. is supported by an Innovative Engineering for Health award by the Wellcome Trust (WT101957) and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) (NS/A000027/1). S.V. is supported by a TBM-FWO grant.

Footnotes

Contribution

What are the novel findings of this work?

In fetal lambs with diaphragmatic hernia (DH), tracheal occlusion using the ‘smart’ tracheal occlusion (Smart-TO) device is effective and safe. The occlusion could be effectively reversed non-invasively and the deflated intact balloon was expelled spontaneously out of the fetal upper airways.

What are the clinical implications of this work?

This study proves the efficacy and safety of the Smart-TO balloon in the DH lamb model. This study is the last preclinical step before a first-in-woman study. Clinical use of this device would obviate the need for a second invasive intervention to re-establish airway patency, thus reducing the risks for the mother and fetus.

Disclosure

N.S. is an inventor of the patented Smart-TO balloon.

References

- 1.Snoek KG, Reiss IK, Greenough A, Capolupo I, Urlesberger B, Wessel L, Storme L, Deprest J, Schaible T, van Heijst A, Tibboel D, et al. Standardized Postnatal Management of Infants with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia in Europe: The CDH EURO Consortium Consensus - 2015 Update. Neonatology. 2016;110:66–74. doi: 10.1159/000444210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameis D, Khoshgoo N, Keijzer R. Abnormal lung development in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2017;26:123–128. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deprest JA, Flake AW, Grataco’s E, Ville Y, Hecher K, Nicolaides K, Johnson MP, Luks FI, Adzick NS, Harrison MR. The making of fetal surgery. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30:653–667. doi: 10.1002/pd.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Maary J, Eastwood MP, Russo FM, Deprest JA, Keijzer R. Fetal Tracheal Occlusion for Severe Pulmonary Hypoplasia in Isolated Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Survival. Ann Surg. 2016;264:929–933. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araujo Ju’ nior E, Tonni G, Martins WP, Ruano R. Procedure-Related Complications and Survival Following Fetoscopic Endotracheal Occlusion (FETO) for Severe Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in the FETO Era. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2017;27:297–305. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1587331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Done E, Grataco’s E, Nicolaides KH, Allegaert K, Valencia C, Castanon M, Martinez JM, Jani J, Van Mieghem T, Greenough A, Gomez O, et al. Predictors of neonatal morbidity in fetuses with severe isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia undergoing fetoscopic tracheal occlusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:77–83. doi: 10.1002/uog.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo FM, Eastwood MP, Keijzer R, Al-Maary J, Toelen J, Van Mieghem T, Deprest JA. Lung size and liver herniation predict need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation but not pulmonary hypertension in isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49:704–713. doi: 10.1002/uog.16000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flageole H, Evrard VA, Piedboeuf B, Laberge JM, Lerut TE, Deprest JA. The plug-unplug sequence: an important step to achieve type II pneumocyte maturation in the fetal lamb model. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:299–303. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90451-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jimenez JA, Eixarch E, DeKoninck P, Bennini JR, Devlieger R, Peralta CF, Grataco’s E, Deprest J. Balloon removal after fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion for congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:78e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Veeken L, Russo FM, De Catte L, Grataco’s E, Benachi A, Ville Y, Nicolaides K, Berg C, Gardener G, Persico N, Bagolan P, et al. Fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion and reestablishment of fetal airways for congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Gynecol Surg. 2018;15:9. doi: 10.1186/s10397-018-1041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sananès N, Regnard P, Mottet N, Miry C, Fellmann L, Haelewyn L, Delaine M, Schneider A, Debry C, Favre R. Evaluation of a new balloon for fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion in the nonhuman primate model. Prenat Diagn. 2019;39:403–408. doi: 10.1002/pd.5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basurto D, Sananès N, Verbeken E, Sharma D, Corno E, Valenzuela I, Van Der Veeken L, Favre R, Russo FM, Deprest J. New device permitting non-invasive reversal of fetoscopic tracheal occlusion: ex-vivo and in-vivo study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:522–531. doi: 10.1002/uog.22132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill I, Emerson M, Altman D. Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biology. 2010;8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinn G, Pearn M, Vutskits L, Mintz C, Loepke A, Lee J, Chen J, Bosnjak Z, Brambrink A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, et al. Standards for Preclinical Research and Publications in Developmental Anaesthetic Neurotoxicity: Expert Opinion Statement From the SmartTots Preclinical Working Group. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deprest JA, Evrard VA, Van Ballaer PP, Verbeken E, Vandenberghe K, Lerut TE, Flageole H. Tracheoscopic endoluminal plugging using an inflatable device in the fetal lamb model. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;81:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davey MG, Hedrick HL, Bouchard S, Mendoza JM, Schwarz U, Adzick NS, Flake AW. Temporary tracheal occlusion in fetal sheep with lung hypoplasia does not improve postnatal lung function. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:1054–1062. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00733.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipsett J, Cool JC, Runciman SC, Ford WD, Parsons DW, Kennedy JD, Martin AJ. Effect of immediate versus slow intrauterine reduction of congenital diaphragmatic hernia on lung development in the sheep: a morphometric analysis of term pulmonary structure and maturity. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;30:228–240. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200009)30:3<228::aid-ppul7>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flageole H, Evrard VA, Vandenberghe K, Lerut TE, Deprest JA. Tracheoscopic endotracheal occlusion in the ovine model: technique and pulmonary effects. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1328–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deprest JA, Evrard VA, Verbeken EK, Perales AJ, Delaere PR, Lerut TE, Flageole H. Tracheal side effects of endoscopic balloon tracheal occlusion in the fetal lamb model. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bratu I, Flageole H, Laberge JM, Kovacs L, Faucher D, Piedboeuf B. Lung function in lambs with diaphragmatic hernia after reversible fetal tracheal occlusion. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1524–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sealed Envelope Ltd. Power calculator for continuous outcome superiority trial. 2012. [Accessed 28 Nov 2020]. https://www.sealedenvelope.com/power/continuous-superiority/

- 22.Davey MG, Danzer E, Schwarz U, Adzick NS, Flake AW, Hedrick HL. Prenatal glucocorticoids and exogenous surfactant therapy improve respiratory function in lambs with severe diaphragmatic hernia following fetal tracheal occlusion. Pediatr Res. 2006;60:131–135. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000227509.94069.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson SM, Hajivassiliou CA, Haddock G, Cameron AD, Robertson L, Olver RE, Hume R. Rescue of the hypoplastic lung by prenatal cyclical strain. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1395–1402. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1284OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fayoux P, Hosana G, Devisme L, Deprest J, Jani J, Vaast P, Storme L. Neonatal tracheal changes following in utero fetoscopic balloon tracheal occlusion in severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breysem L, Debeer A, Claus F, Proesmans M, De Keyzer F, Lewi P, Allegaert K, Smet MH, Deprest J. Cross-sectional study of tracheomegaly in children after fetal tracheal occlusion for severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Radiology. 2010;257:226–232. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10092388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deprest J, Breysem L, Grataco’s E, Nicolaides K, Claus F, Debeer A, Smet MH, Proesmans M, Fayoux P, Storme L. Tracheal side effects following fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion for severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:670–673. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1579-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McHugh K, Afaq A, Broderick N, Gabra HO, Roebuck DJ, Elliott MJ. Tracheomegaly: a complication of fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion in the treatment of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:674–680. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basurto D, Russo FM, Van der Veeken L, Van der Merwe J, Hooper S, Benachi A, De Bie F, Gomez O, Deprest J. Prenatal diagnosis and management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;58:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.George AT, Motiwale S. Magnets, children and the bowel: a dangerous attraction? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5324–5328. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i38.5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson M, Tringali A, Dumonceau JM, Tavares M, Tabbers MM, Furlano R, Spaander M, Hassan C, Tzvinikos C, Ijsselstijn H, Viala J, et al. Paediatric Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:133–153. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.