Abstract

In this Series paper, we review evidence on the co-occurring and synergistic epidemics (syndemic) of HIV and mental health problems worldwide among men who have sex with men (MSM). The multilevel determinants of this global syndemic include structural factors that enable stigma, systematic bias, and violence towards MSM across geographical and cultural contexts. Cumulative exposure to these factors over time results in population-level inequities in the burden of HIV infections and mental health problems among MSM. Evidence for this syndemic among MSM is strongest in the USA, Canada, western Europe, and parts of Asia and Latin America, with emerging evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Integrated interventions are needed to address syndemics of HIV and mental health problems that challenge the wellbeing of MSM populations worldwide, and such interventions should consider various mental health conditions (eg, depression, anxiety, trauma, and suicidality) and their unique expressions and relationships with HIV outcomes depending on cultural contexts. In addition, interventions should identify and intervene with locally relevant structural factors that result in HIV and mental health vulnerabilities among MSM.

Introduction

In 1981, the first known HIV/AIDS case report described a cluster of unexplained infections among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the USA.1 HIV/AIDS has since developed into a global pandemic that affects diverse populations.2 However, MSM are a priority population for prevention and treatment interventions worldwide, including in low-income countries and increasingly in sub-Saharan Africa, where MSM have not been historically visible.3–6 The 2021 UNAIDS Global AIDS Update reported that the risk of HIV acquisition is 25 times greater among MSM than among heterosexual men.7 In 2020, MSM accounted for 75% of new HIV infections in western Europe, the USA, and Canada, 53% in Asia, 46% in Latin America, 21% in the Caribbean, 20% in the Middle East and northern Africa, 16% in eastern Europe and central Asia, 14% in western and central Africa, and 4% in eastern and southern Africa.7 However, stigma and discrimination are likely to contribute to reporting bias and underestimates in regions with strong stigma towards MSM.

In the past 40 years, increasing attention has been given to the multidimensional mental health vulnerabilities of MSM, such as depression, anxiety, substance use, and trauma. For example, the prevalence of depression in MSM in the USA is estimated to be 17·2%, which is higher than the overall prevalence for adult men in the USA,8 and the risks of post-traumatic stress and substance use are at least two times higher in MSM.9,10 A 2017 meta-analysis estimated the pooled lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation at 25·8% among HIV-positive MSM and 17·0% among HIV-negative MSM.11 In the USA, rates of post-traumatic stress are much higher in HIV-positive MSM (up to 74%) than in the general population (8%).12–14 Most research into the mental health challenges faced by MSM comes from the USA, Canada, and western Europe,15,16 although data are increasingly available from Asia,17,18 sub-Saharan Africa,19–21 Latin America,22–24 and eastern Europe and central Asia.25–27

Evidence for the co-occurring epidemics of HIV and mental health problems among MSM align with the concept of a syndemic—the concentration and interaction of these two epidemics in a manner that exacerbates illness, disease, and death within this population.28 The strongest evidence for syndemics of HIV and mental health problems among MSM comes from the USA, Canada, western Europe, and some parts of Asia and Latin America, with emerging evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. The application of syndemic framework provides a means to understand the synergies and exacerbated population effects of these complex, multidimensional health conditions. Syndemic framework also underscores the social and structural inequities that marginalise MSM communities across geographical boundaries, limiting opportunities for optimal health among individual MSM.29

In this Series paper, we review literature on the multilevel factors that contribute to the global syndemic of HIV and mental health problems among MSM and, on the basis of current evidence, offer recommendations for investment in culturally responsive services to address these synergistic health conditions. We use a scoping approach that considers systematic reviews, relevant intervention trials published since 2016, community surveys, and epidemiological reports on HIV and mental health in MSM populations without geographical restrictions. We did not do a protocol-driven systematic literature search, as our aim was to identify and collate selected findings from relevant illustrative studies.

Complex determinants of HIV and mental health problems

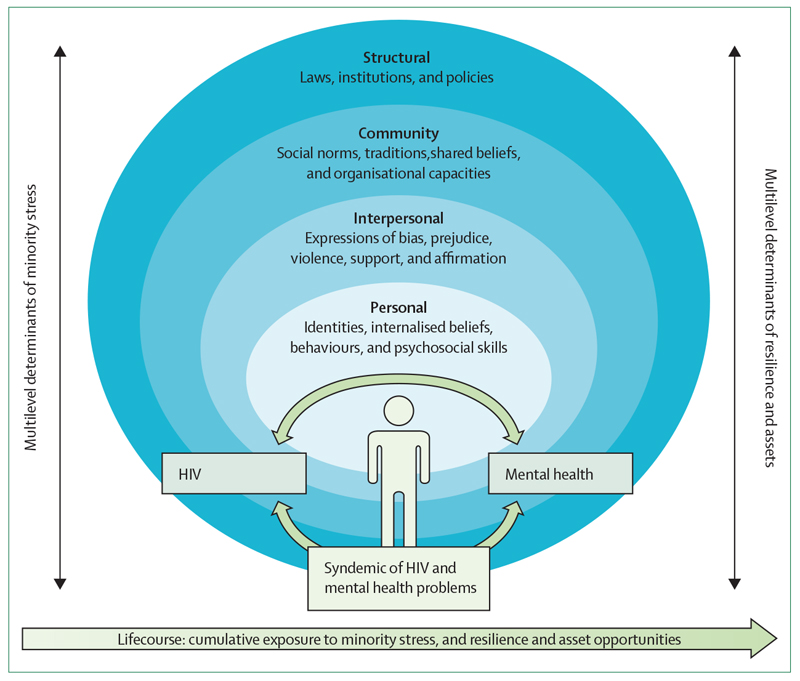

Conceptual frameworks have described multilevel factors that contribute to the disproportionate burden of HIV and mental health conditions among MSM. Although a comprehensive review is beyond the scope of this Series paper, several conceptual frameworks are useful for guiding the design and implementation of public health interventions for MSM populations (figure, panel 1).

Figure. Multilevel processes contributing to syndemics of HIV and mental health problems in men who have sex with men.

The schematic is based on selected conceptual frameworks with aetiological examples from literature.

Panel 1. Selected conceptual frameworks to understand and address global syndemics of HIV and mental health problems in MSM.

Syndemic theory

Synergistic and mutually reinforcing HIV and mental health epidemics are concentrated in communities of men who have sex with men (MSM), derive from social and structural inequities, and bring about exacerbated illness, disease, and death in MSM populations.

Sexual prejudice framework

Anti-MSM bias reflects negative regard towards non-heterosexual behaviours and identities, and arises from social factors including heteronormativity and sexual stigma.

Minority stress theory

Exposure to chronic distal and proximal stress due to anti-MSM stigma evokes psychological and physiological reactions at the individual level, resulting in mental health and behavioural health vulnerabilities.

Lifecourse approach

Health status among individual MSM is determined by cumulative earlier life experiences including exposure to bullying, abuse, emotional distress, and rejection due to anti-MSM bias.

Intersectionality theory

Individuals can have multiple identities, each with distinct histories in terms of power and inequality. These identities converge at the individual level, shaping health, human experience, and access to resources.

Health equity promotion model

Emphasis on resilience, assets, and agency of MSM to maximise health and wellness, while recognising unequal opportunities and constraints related to intersectional identities and social contexts.

Socioecological model

Individual, interpersonal, community, and societal-level factors lead to mental health and HIV risk, such as internalised stigma, domestic violence, school bullying, and anti-LGBTQ laws.

Herek’s sexual prejudice framework provides a foundation for understanding the nature of anti-MSM bias worldwide.30,31 Rather than conceptualising this bias as a form of fear towards same-sex sexuality (ie, homophobia), this framework describes sexual prejudice as the active expression of antipathy towards non-heterosexual behaviours and identities.31 Sexual prejudice derives jointly from heterosexism (a society’s prioritisation of heteronormative sexual attraction and relationships) and sexual stigma (a society’s collective disparagement of non-heterosexual expressions). Previous reviews have described how these factors have downstream effects on individual-level behavioural and biological risks that contribute to HIV transmission and psychological health.32

The minority stress model posits that exposure to sexual prejudice and anti-MSM stigma determine adverse behavioural and physiological health outcomes.33 Stigma can occur at multiple levels, including internalised, anticipated, enacted, and structural forms of bias.34 Repeated exposure to forms of anti-MSM stigma can produce emotional distress, pressure to conceal one’s identity, social isolation, maladaptive coping, and physiological reactivity. Cross-cultural evidence for the role of minority stress as a determinant of mental health problems is emerging in multiple countries.35 Several studies have found links between exposure to minority stress and HIV risk or treatment outcomes among MSM.36–38

A life-course epidemiology approach has been used to explain current mental health and HIV status, including HIV-related behaviours, as a function of the accumulation of risks and protective factors throughout a person’s previous life stages.39 This approach uses a temporal and social perspective to understand current health patterns, recognising the effect of earlier life events (eg, childhood abuse, peer bullying, and early life trauma) on HIV and mental health outcomes later in life.40–43

Originally born out of Black feminist scholarship, intersectionality theory examines the interlocking systems of privilege and oppression that operate at social and structural levels and influence the individual level for people with complex identities that are defined by minoritised race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and other marginalised statuses.44 Identities do not exist in isolation, and MSM with multiple marginalised identities (for example, MSM who are also ethnic minorities in their local context, economically disadvantaged, migrants, sex workers, and members of justice-involved or drug-using subgroups) experience negative effects of intersecting stigmas to a greater extent than do MSM with single marginalised identities. HIV and mental health interventions for MSM should be cognisant of multiple stigmas simultaneously determining health vulnerabilities among individual members of the population.

The health equity promotion model offers a strengths-based perspective to support MSM to reach optimal physical and mental health; the framework is broadly relevant for all sexual-minority and gender-minority populations.45 This model considers the role of health-promoting factors, such as individual-level agency and collective forms of advocacy, as mechanisms to challenge the adverse social and psychological processes that result in poor health of MSM. Factors that MSM can use to promote their health vary according to context, culture, and an individual’s position within society. This framework has been used primarily in mental health research with MSM, and applications to HIV have been scarce.

Each of these frameworks aligns with the socio-ecological systems model, which considers multilevel determinants of health for individuals.46 Together, these models provide complementary insight into the complex development of syndemics of HIV and mental health problems in MSM, and highlight the shortcomings of individual-level behaviour-change models for HIV prevention that do not account for mental health problems and the upstream determinants of these syndemics.

Evidence of multilevel determinants of HIV and mental health problems

Studies of the social and structural determinants of HIV and mental health inequities in MSM are most commonly done in the USA, Canada, and western Europe. Reviews of USA-based studies corroborate the role of multilevel stigma and minority stress as determinants of HIV and mental health in MSM.32,47–49 For example, self-stigma among MSM in the USA has been associated with emotional distress and HIV testing and diagnosis.47,50 A study of MSM in 28 European countries found that structural stigma (eg, discriminatory policies and laws) was associated with pressures to conceal one’s identity and with lower life satisfaction,51 and a related study of MSM from 38 European countries found that structural stigma was associated with lower use of HIV-prevention services and higher HIV risk behaviours.52 Research involving MSM from 48 countries (mostly in Europe) reported that those who migrated from a country with highly stigmatising laws to countries in which MSM were less stigmatised had a significantly lower risk of depression, suicidality, internalised stigma, and social isolation after migration.53 Studies in the USA and Canada have used intersectionality framework to analyse the role of compounding stigmas on health inequities among Black and Latino MSM, who have disproportionately higher HIV risk than White MSM.54

Anti-MSM stigmas have been characterised in many parts of Asia, where there is increasing research that describes associations between minority stress, HIV, and mental health.35,55,56 For example, a study based in India found that anti-MSM legislation was associated with pressure to conceal one’s sexual identity and was predictive of depressive symptoms.57 A study of MSM in Thailand found that lifetime suicidal attempts were associated with experiences of social discrimination, stress, internalised homophobia, and loneliness.58 Experiences of minority stress have also been linked with HIV risk behaviour among MSM in China,59,60 and with treatment engagement and mental health problems among HIV-positive MSM in China.61 A history of discrimination and anticipated stigma in health-service settings have been noted as barriers to engagement with HIV prevention or treatment strategies for MSM in Vietnam, Philippines, and Malaysia.62–64 Syndemic analysis has been used to examine health inequities (eg, HIV, mental health, and other behavioural health risks) in MSM in several Asian countries, including Taiwan, Malaysia, and China.65–67 To date, intersectionality theory has been used infrequently in research involving MSM in Asia, although increasing attention to social class and migration status among MSM in this region suggests that the use of this theory would be of practical relevance.

Multilevel stigmas towards MSM in sub-Saharan Africa have been documented, including family rejection, peer abuse and bullying, community violence, and anti-MSM policies.68 26 countries in sub-Saharan Africa have legislation that criminalises same-sex behaviour. Anti-MSM stigma and discrimination are linked to poor mental health in studies of MSM in South Africa, Lesotho, Cameroon, and Tanzania.69–72 A systematic review of 75 studies assessing HIV testing and engagement among MSM in Africa found that HIV testing and awareness of HIV status were lowest in countries with the most severe levels of structural stigma.73 Disclosure of sexual identity was higher in less stigmatising African countries; such disclosure could facilitate engagement in HIV testing and prevention in these countries.73 However, that medical environments are safe contexts for disclosure cannot be assumed. A study of MSM in Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Eswatini, Lesotho, and Senegal found that MSM who had disclosed their sexuality to health-care workers were more likely to express fear of health services, avoid health services, face gossiping by health-care workers, and feel mistreated in the health centre.74 These findings align with minority stress theory by revealing adverse interpersonal consequences, such as stigma and shame, for MSM who disclose their sexuality in unsupportive medical environments, which can ultimately result in avoidance of and disengagement with health care. Consistent with syndemic framework, studies in several African countries have shown synergistic links between HIV, mental health, and contextual inequalities among MSM.75–78 Few studies to date have used intersectionality to analyse health inequities among MSM in Africa, despite recognition of co-occurring stigmas among MSM with multiple marginalised identities in this region.77,79

Studies in Latin America corroborate the negative consequences of minority stress for HIV and mental health outcomes. Exposure to anti-MSM stigma is associated with mental health problems among MSM in Chile, Mexico, Brazil, and Peru,80–83 and with HIV risk and prevention behaviours among MSM in El Salvador, Belize, and Guatemala.36,84,85 A few studies have applied syndemic theory to examine health inequities among MSM in Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil.86–88 For example, a study in Mexico found that the presence of a larger number of syndemic conditions (eg, depression, internalised homophobia, violence, and substance use) was associated with greater HIV risk behaviour; however, this association was weaker for men who had disclosed their sexuality to more people, which suggests that openness about sexuality could promote resilience to HIV risks.

A 2020 systematic review89 of psychological and behavioural health interventions for sexual-minority and gender-minority populations (published between 2003 and 2019) examined the extent to which these interventions explicitly addressed stigma. This review included 37 published interventions, of which 33 addressed MSM. Most studies were done in the USA (n=24), with fewer studies in Canada (n=4), Australia and New Zealand (n=3), Mexico (n=2), China (n=2), Thailand (n=1), and Senegal (n=1). Internalised stigma (n=24) and enacted stigma (n=21) were the most common foci of these interventions, followed by anticipated stigma (n=12), with few studies addressing structural stigma (n=3).

Another systematic review90 in 2020 examined the extent to which mental health interventions for people from sexual minorities integrated principles of inter-sectionality theory. The review identified 43 mental health interventions for people from sexual minorities, of which seven (16%) actively addressed the effects of participants’ interlocking marginalised identities and explicitly used intersectionality theory. Of the interventions that exclusively targeted MSM (n=29), only three (10%) used intersectionality theory. Notably, the majority of mental health interventions for MSM were in the USA (n=21), with three in Europe (the Netherlands, Romania, and Switzerland), two in Canada, and one each in Australia, China, and South Africa.

Ultimately, addressing the social determinants of HIV and mental health inequities faced by MSM will require greater emphasis on community and structural interventions to improve the environments in which MSM live, to enhance access to interventions, to improve the quality of care, and to reduce the barriers to healthy living for all. Interventions that conceptualise mental health and HIV risk among MSM as exclusively individual-level phenomena, without recognising social determinants, could have little effect on improving population-level outcomes. Consequently, if left understudied and unchallenged, multilevel anti-MSM stigmas and sexual minority stress will continue to be major impediments to achieving the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets for the HIV care cascade by 2030, particularly in settings with severe sexual minority stigma.

Integrated interventions for MSM to end the global HIV epidemic

Interventions that address the interconnections between mental health and HIV risk, prevention, and treatment outcomes among MSM are necessary to achieve population-level improvements in health. However, health interventions for MSM are frequently designed to prioritise HIV over other health and survival needs. The modest and short-term effects of many HIV-specific interventions for MSM can be enhanced by integrating attention to mental health concerns, which are often personally prioritised by MSM as more immediate and proximal than their sexual health risks.91

Some interventions for HIV-negative MSM have targeted both sexual risk behaviours and mental health symptoms. For example, 40 & Forward—a group-based intervention for ageing MSM (40 years and older) who self-report depression, social anxiety, and isolation—was found to be effective in reducing these mental health issues and enhancing self-efficacy regarding condom use.92 In response to the high prevalence of HIV risk among MSM who were sexually abused in childhood, an intervention programme in the USA provided evidence for the integration of cognitive behavioural therapy for trauma and self-care as a means to reduce HIV risk and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.93 Another intervention with HIV-negative MSM in India compared resilience-focused psychosocial group and individual counselling with standard-of-care as a control, and found larger reductions in condomless sex and depressive symptoms and larger improvements in self-esteem in the intervention group than in the control group, from baseline to 12-month follow-up.94 A transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural therapy programme called ESTEEM targeted young MSM in the USA who had reported recent condomless sex and psychological distress; the programme reduced depression, alcohol use, and condomless sex compared with a waitlist control.95 Adaptation and evaluation of this intervention for MSM in Romania found an increase in HIV knowledge, recent HIV testing, and self-efficacy regarding condom use, and a reduction in heavy alcohol use and symptoms of mental health problems among programme recipients.96 The programme has also been culturally adapted for delivery to MSM in China.97

Mental health interventions for MSM living with HIV have focused on various issues facing this population, such as psychological wellbeing, substance use, sexual health, and HIV care. Examples of interventions include cognitive behavioural therapy for HIV-positive MSM with psychological distress in China,98 and in the USA, the use of a unified protocol for MSM living with HIV with sexual compulsivity issues,99 group-based, mindfulness-based stress reduction for gay men living with HIV,100 and tailored mindfulness-based intervention for MSM living with HIV who use methamphetamine.101 Integrated interventions that address intersectional issues (eg, racial discrimination and sexual stigma) and mitigate structural issues (eg, unemployment) among MSM are also being developed.102,103 This growing body of research highlights the potential of mental health interventions to improve sexual health, reduce HIV risk, and support MSM living with HIV as they navigate HIV prevention and health-care systems.

The current body of literature on integrated HIV and mental health interventions has several limitations. First, most of the research has been done in the USA, which raises concerns about generalisability to settings in which sexuality and mental health are shaped by unique cultural factors and health-service systems are very different. Much has been written about the need to decolonise public health and psychological interventions.104,105 In this regard, mental health services should be recognised as culturally encapsulated healing practices that have been generated typically through an individualistic cultural model (and financial model) of psychological health services based in western European or US settings.106 The damaging history and legacies of such mental health models related to same-sex sexuality (ie, the American Psychiatric Association categorising same-sex attraction as a mental illness until 1973), which have shaped understanding of sexual orientation in many contexts in other regions, should also be acknowledged.107 The same-sex sexual identities of men are also shaped by cultural, historic, neo-colonial, political, and economic factors in specific regions. Researchers and stakeholders should understand the specific context that shapes the identities, lived experiences, and health outcomes of MSM, and develop locally relevant and responsive programmes to minimise potential harm. For example, in high-stigma contexts, identity concealment is a common and adaptive coping strategy.56 Short-term interventions (eg, time-limited therapy), which are often practised in the psychiatric health-care system in the USA, might provide only a very limited approach to address mental health issues for MSM in other countries. Second, the mental health symptoms and experiences of MSM addressed by the current research are heterogenous. Expressions of mental health problems are likely to be context-dependent, and the relationship of these symptoms with HIV risk could vary depending on local cultural systems. Third, few structural interventions tailored for MSM address factors linked to poor mental health such as incarceration and human rights issues, economic concerns, housing and workplace discrimination, relationship validation, and marriage laws. Finally, recognition that community-based, non-governmental organisations in many parts of the world already provide locally developed, integrated approaches to address HIV and mental health among MSM is important. For example, the Humsufar Trust in Mumbai, India provides programmes that address HIV, mental health, social support, and legal advocacy for MSM and other people from sexual-minority and gender-minority populations, including young people living with HIV. Love Yourself, based in Manila, Philippines, is a non-governmental organisation that serves MSM and people from other minority populations by offering HIV testing, prevention, and treatment support services, and peer-based counselling to address mental health needs. In Cape Town, South Africa, the Triangle Project delivers HIV prevention, testing and treatment referrals, and mental health support services, legal advocacy, and substance-use harm-reduction services to MSM and other sexual-minority and gender-minority populations. In accordance with syndemic and inter-sectionality frameworks, organisations such as these typically do not address health conditions in isolation or regard clients solely on the basis of their sexual identity; furthermore, commensurate with the health equity promotion model, such organisations acknowledge the strengths and assets within local client communities and advocate for social change. However, many community organisations that serve MSM and other sexual-minority and gender-minority populations are underfunded or receive funds that are earmarked to address single health conditions (eg, exclusively HIV services). Partnerships and investment in these and other frontline community organisations is a crucial component of global efforts to improve HIV and mental health outcomes among MSM and other sexual-minority and gender-minority populations (panel 2).

Panel 2. Case study—a transformative HIV research partnership with MSM in coastal Kenya.

Research with men who have sex with men (MSM) in coastal Kenya started in 2005 when participants joined an HIV vaccine feasibility cohort study in Mtwapa. The initial studies conducted at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) were among the first on the African continent to show evidence of high HIV incidence among MSM, with HIV incidence rates before the availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis estimated at 8·6 cases per 100 person years.108 Research-based services—including HIV testing and counselling, treatment for sexually transmitted infections, MSM peer-support groups, and referrals to community advocacy groups—were provided to MSM who participated in the programme. Integration of social support and community links with the research were the mainstay of the project and contributed to its success.

In 2010, the project site was shut down by members of the local community, who were reacting to rumours that the clinic research site was initiating young men to homosexuality and into same-sex marriages—both of which are considered taboo and are criminalised in Kenya.109 A documentary by Sorious Samura, named Africa’s Last Taboo, shows original footage of the event, with large groups congregating outside the clinic, resulting in the temporary shutdown of services and arrest of research volunteers. One KEMRI participant in the programme, who was interviewed in the documentary, says that he would have been set on fire as community members poured paraffin on him and planned to ignite him, and only a miracle saved him.

Violence towards MSM is associated with HIV risk. During a study done between 2005 and 2014 in Mtwapa, the incidence of rape for MSM was 3·9 events per 100 person years.110 Physical and verbal assault were also common. In two studies assessing mental health and substance use challenges among MSM in Kenya, many reported childhood abuse (77%), symptoms of depression (31% of participants had Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores of 10 or more), hazardous alcohol use (41%), or problematic substance use (51%).111,112

In response to the clinic shutdown in 2010, the research programme initiated a sensitisation programme for community stakeholders, religious leaders, health-care providers, and government officials.113–115 Sensitisation programmes were delivered in collaboration with representatives from local LGBT organisations. The theme of these sensitisations was “facing our fears”, and fears were mitigated through respectful listening to all stakeholders involved. Evaluation in 2013 indicated long-term positive effects on sensitisation programme participants.

Research with MSM continued uninterrupted for another 10 years, until complications related to the COVID pandemic later closed services. Increasingly, research was done in collaboration with LGBT groups and peer mobilisers, including an intervention trial that aimed to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among MSM,116 a partner notification study that aimed to identify new HIV infections among MSM,117 an intermittent pre-exposure prophylaxis study,118 and the first known study to suggest that anti-MSM prejudice can be reduced among Kenyan health-care providers after sensitivity training.119 Research with MSM was enabled through the strong support for vulnerable populations, the non-judgemental attitudes of research programme staff, and a strong community stakeholder engagement programme.

Structural interventions to promote societal change and improve health equity

As of 2020, same-sex behaviours were criminalised in 71 countries worldwide. Policing of MSM reflects the historical and contemporary social construction of MSM populations as entities to be surveilled and restrained. State-sanctioned stigma impairs sexual and mental health of MSM, and their use of mental health care, HIV prevention and treatment, and other health services.120 Similarly, people from sexual minorities in many global settings have been historically pathologised and medicalised as person-objects needing treatment. These characterisations of the lives of MSM have resulted in both formal and social policing, and contribute to the disproportionate presence of men from sexual minorities in secure settings such as jails, prisons, hospitals, juvenile detention, and immigration detention facilities.121 Decriminalisation of same-sex behaviours will increase the ability of MSM to be open and not fearful about their sexuality and identities, which is essential for optimising health and use of mental health care and comprehensive HIV prevention and treatment. The historic 2016 vote by the UN Human Rights Council to adopt a resolution protecting MSM and other sexual and gender minorities against violence and discrimination provides a global-level framework to support national-level human rights advocacy efforts.

Discrimination and violence towards MSM often begins in childhood in the forms of family rejection, peer harassment and bullying, and other types of violence including sexual victimisation. This cumulative experience of stigma increases the risk of mental distress and maladaptive coping processes such as substance use.33,34 Systematic efforts are needed to disrupt societal patterns of abuse towards children who are perceived as non-heteronormative, and to provide support to children with diverse gender expressions in schools and community settings. Such efforts can reduce vulnerability to sexual, mental, and behavioural health risks later in life.

Initiatives that affirm and legitimise same-sex relationships can transform the sexual and mental health of MSM and other sexual minorities. Evidence supports the mental health benefits for sexual minorities after the passage of marriage-equality laws.122 Relationship-strengthening interventions for MSM are associated with lower HIV transmission risk and improved HIV treatment outcomes for MSM living with HIV.123 However, evidence indicates that social and political debates about marriage equality are sources of minority stress for individuals from sexual minorities, and thereby contribute to mental health problems.124 Conceiving of marriage-equality legislation in many countries is difficult, owing to local histories and belief systems. Culturally aligned approaches are needed to conceptualise opportunities for relationship strengthening and affirmation programmes for same-sex partnerships in countries with highly conservative, heteronormative values.

Recognition and investment in multilevel stakeholders within the fields of public health, biomedicine, and policy are essential to address structural-level aims and to tackle the syndemic of HIV and mental health problems for MSM. Community-based organisations and grassroots initiatives can advocate for policy changes to increase social, legal, and economic equity for and reduce discrimination against sexual minorities. Health providers and health systems can enact more inclusive approaches for MSM and people from other sexual minorities who are seeking sexual, mental, and behavioural health interventions. Transformations within health education institutions and professional training programmes are needed to prepare providers to deliver non-biased and effective services to MSM and other patients from sexual minorities. At all levels of change, individual professionals and organisational systems should acknowledge historic biases and inequitable practices that have disadvantaged MSM and individuals from other sexual minorities who are seeking services and have perpetuated HIV and mental health vulnerabilities. However, interventions should recognise the realities of local context, infrastructure, and epidemiology. MSM-centered initiatives might not resonate with local priorities in settings with generalised high-prevalence HIV epidemics, owing to overwhelming demands at the population level. At a minimum, this Series paper underscores the need for integrated HIV and mental health policies and interventions worldwide to be inclusive of MSM through responsive, engaged, and community-empowering practices.

Conclusion and future directions

We propose that prioritising the promotion of mental health among MSM is a public health strategy that could help to end the global HIV epidemic. Improving mental health in and of itself is an under-recognised public health priority for MSM populations worldwide. Integrated intervention approaches are needed. We provide several key considerations on the basis of our review (panel 3). First, psychological care is often prioritised for only part of the population (eg, individuals who meet criteria for mental disorders and who have access to psychological and economic resources), rather than considered a basic need for all individuals. Consequently, mental health services are deprioritised and typically decoupled from other health services such as HIV prevention and treatment. The integration of mental health interventions and HIV prevention and care services can happen on various levels, such as a brief mental health assessment and relevant referrals at HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis sites, the inclusion of relevant mental and relational health content as part of sexual health promotion programmes, and the formation and provision of support groups for MSM in schools, workplaces, LGBTQ-related community organisations, and HIV care clinics. Stakeholders in HIV prevention and care services can work with psychological professionals to create more comprehensive systems of care that address mental health as a key target. Second, indigenous, local approaches to mental health interventions should be understood and affirmed. Engaging local MSM communities in the process of intervention development and roll-out might be beneficial to harness resilience factors and effective coping strategies within the local community. In high-prevalence settings, local mental health, HIV prevention and treatment, and stigma-reduction programmes for general populations can be adapted to include MSM in those settings. Third, competent service providers skilled in mental health care for MSM are required. Mental health is a multidimensional construct, requiring sensitivity to unique expressions and symptoms that might vary across contexts and pose differing challenges for HIV prevention and risk. In highly stigmatising and resource-limited settings, targeting common mental health elements (ie, emotional, cognitive, interpersonal, and behavioural components) and training lay providers have proven to be effective approaches.125 Furthermore, training physicians, counsellors, and HIV service providers in the care of MSM can encourage MSM to seek psychological help and to address the intersectional stigmas of HIV risk and disease, MSM identity, and mental health. Finally, efforts to acknowledge the contributions of locally developed approaches to promoting health equity for MSM populations in diverse cultural contexts should be more commonly practised. Such efforts are likely to yield innovative solutions for HIV and mental health inequities, which can diversify the range of practices to support the health of MSM populations and contribute to the decolonisation of public health across and within global contexts.

Panel 3. Recommendations to address syndemics of HIV and mental health problems in men who have sex with men.

Prioritise mental health as a foundation for HIV prevention and treatment programmes, and for other public health programmes for men who have sex with men (MSM)

Acknowledge diversity within MSM communities and the presence of multiple stigmas related to intersectional identities

Develop, adapt, and implement brief integrated interventions that are relevant to the social context of HIV and mental health challenges in local settings

Recognise indigenous approaches to support mental health in local contexts

Invest in local community-based organisations that provide holistic health, social, and advocacy services to sexual-minority and gender-minority populations

Address childhood forms of anti-MSM bias through family, community, and school-based interventions

Support and affirm family, peer, and intimate relationships for MSM

Train health and social-service providers in delivery of inclusive programmes for MSM

Improve structural and legal systems for supporting the rights of people from sexual or gender minorities

Key messages.

There is strong evidence for a global syndemic of mental health problems and HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) populations worldwide

Anti-MSM stigma contributes to disproportionate mental health problems and HIV transmission in this population

Improving access and quality of mental health support services for MSM worldwide is essential to end the HIV epidemic

Structural determinants of mental health problems and HIV for MSM present complex challenges and require multilevel public health interventions

Efforts are needed to expand the professional and paraprofessional mental health workforce, invest in civil society organisations that support MSM, and reform policies to enable full societal inclusion and basic rights for MSM worldwide

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We used a scoping approach that considered systematic reviews, recent relevant intervention trials, community surveys, and epidemiological reports on HIV and mental health in populations of men who have sex with men (MSM). We searched PubMed and PsycINFO using relevant keywords (eg, “MSM”, “gay”, “homosexual*”, “mental health”, “HIV”, and “intervention”) for relevant reports published in English from database inception until Dec 1, 2021, without restriction by geography.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K23AT011173, R21TW012010, R21TW011762, R01MH123352, R21MD016356, and D43TW010565. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This is the third in a Series of three papers about alignment of mental health and HIV services to be published in conjunction with The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health and The Lancet Psychiatry. All papers in the Series are available at: https://www.thelancet.com/series/mental-health-and-HIV

For more on the sensitisation programme see https://www.marps-africa.org

For the documentary see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AVp8V1npqyk

Contributors

DO and SSu conceived this Series paper, and DO integrated the contributions from all authors. DO, SSu, ANB, RM, and SSh reviewed the literature and prepared the first draft. EvdE and ES prepared panels, reviewed drafts, and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Amiel Nazer Bermudez, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA; College of Public Health, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines.

Rainier Masa, School of Social Work, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Sylvia Shangani, College of Health Sciences, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA.

Elise van der Elst, KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kilifi, Kenya.

Prof Eduard Sanders, KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kilifi, Kenya; Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2019 HIV Collaborators. Global, regional, and national sex-specific burden and control of the HIV epidemic, 1990–2019, for 204 countries and territories: the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019. Lancet HIV. 2021;8:e633–51. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00152-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380:367–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coelho LE, Torres TS, Veloso VG, et al. The prevalence of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) and young MSM in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:3223–37. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davlidova S, Haley-Johnson Z, Nyhan K, Farooq A, Vermund SH, Ali S. Prevalence of HIV, HCV and HBV in central Asia and the Caucasus: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:510–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hessou PHS, Glele-Ahanhanzo Y, Adekpedjou R, et al. Comparison of the prevalence rates of HIV infection between men who have sex with men (MSM) and men in the general population in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1634. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-8000-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2021: confronting inequalities—lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of AIDS. 2021. [accessed Nov 4, 2021]. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2021-global-aids-update_en.pdf .

- 8.Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, et al. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:278–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts AL, Austin SB, Corliss HL, Vandermorris AK, Koenen KC. Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2433–41. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo Z, Feng T, Fu H, Yang T. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:406. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1575-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neigh GN, Rhodes ST, Valdez A, Jovanovic T. PTSD co-morbid with HIV: separate but equal, or two parts of a whole? Neurobiol Dis. 2016;92:116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS. 2019;33:1411–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherr L, Nagra N, Kulubya G, Catalan J, Clucas C, Harding R. HIV infection associated post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth—a systematic review. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16:612–29. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.579991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.di Giacomo E, Krausz M, Colmegna F, Aspesi F, Clerici M. Estimating the risk of attempted suicide among sexual minority youths: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:1145–52. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plöderl M, Tremblay P. Mental health of sexual minorities—a systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27:367–85. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guadamuz TE, McCarthy K, Wimonsate W, et al. Psychosocial health conditions and HIV prevalence and incidence in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand: evidence of a syndemic effect. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:2089–96. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Zhang B, Li Y, Antonio AL, Chen Y, Williams AB. Mental health and suicidal ideation among Chinese women who have sex with men who have sex with men (MSM) Women Health. 2016;56:940–56. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2016.1145171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jauregui JC, Mwochi CR, Crawford J, et al. Experiences of violence and mental health concerns among sexual and gender minority adults in western Kenya. LGBT Health. 2021;8:494–501. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makanjuola O, Folayan MO, Oginni OA. On being gay in Nigeria: discrimination, mental health distress, and coping. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2018;22:372–84. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandfort T, Bos H, Knox J, Reddy V. Gender nonconformity, discrimination, and mental health among Black South African men who have sex with men: a further exploration of unexpected findings. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45:661–70. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0565-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galea JT, Marhefka S, León SR, et al. High levels of mild to moderate depression among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Lima, Peru: implications for integrated depression and HIV care. AIDS Care. 2021 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2021.1991877. published online Oct 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torres JL, Gonçalves GP, Pinho AA, Souza MHDN. The Brazilian LGBT+ Health Survey: methodology and descriptive results. Cad Saude Publica. 2021;37:e00069521. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00069521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zea MC, Barnett AP, Río-González AMD, et al. Experiences of violence and mental health outcomes among Colombian men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women. J Interpers Violence. 2021 doi: 10.1177/0886260521997445. published online March 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hylton E, Wirtz AL, Zelaya CE, et al. Sexual identity, stigma, and depression: the role of the “anti-gay propaganda law” in mental health among men who have sex with men in Moscow, Russia. J Urban Health. 2017;94:319–29. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0133-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janković J, Slijepčević V, Miletić V. Depression and suicidal behavior in LGB and heterosexual populations in Serbia and their differences: cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terloyeva D, Nugmanova Z, Akhmetova G, et al. Untreated depression among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus in Kazakhstan: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 2017;389:941–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos G-M, Do T, Beck J, et al. Syndemic conditions associated with increased HIV risk in a global sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:250–53. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herek GM. The psychology of sexual prejudice. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2000;9:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herek GM. Beyond “homophobia”: thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2004;1:6–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:707–30. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63:985–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sattler FA, Lemke R. Testing the cross-cultural robustness of the minority stress model in gay and bisexual men. J Homosex. 2019;66:189–208. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1400310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrinopoulos K, Hembling J, Guardado ME, de Maria Hernández F, Nieto AI, Melendez G. Evidence of the negative effect of sexual minority stigma on HIV testing among MSM and transgender women in San Salvador, El Salvador. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:60–71. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0813-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aunon FM, Simoni JM, Yang JP, et al. Depression and anxiety among HIV-positive men who have sex with men and men who have sex with women in China. AIDS Care. 2020;32:362–69. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1683803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storholm ED, Huang W, Siconolfi DE, et al. Sources of resilience as mediators of the effect of minority stress on stimulant use and sexual risk behavior among young Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:3384–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02572-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emlet CA. “You’re awfully old to have this disease”: experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist. 2006;46:781–90. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mojola SA, Williams J, Angotti N, Gómez-Olivé FX. HIV after 40 in rural South Africa: a life course approach to HIV vulnerability among middle aged and older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2015;143:204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Negin J, Nemser B, Cumming R, Lelerai E, Ben Amor Y, Pronyk P. HIV attitudes, awareness and testing among older adults in Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:63–68. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9994-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schatz E, Houle B, Mojola SA, Angotti N, Williams J. How to “live a good life”: aging and HIV testing in rural South Africa. J Aging Health. 2019;31:709–32. doi: 10.1177/0898264317751945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1267–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim HJ, et al. The health equity promotion model: reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:653–63. doi: 10.1037/ort0000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bronfenbrenner U. In: Six theories of child development: revised formulations and current issues. Vasta R, editor. London: Jessica Kingsley; 1992. Ecological systems theory; pp. 188–249. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Babel RA, Wang P, Alessi EJ, Raymond HF, Wei C. Stigma, HIV risk, and access to HIV prevention and treatment services among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a scoping review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:3574–604. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03262-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunn JK, et al. Effectiveness of HIV stigma interventions for men who have sex with men (MSM) with and without HIV in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analyses. AIDS Behav. 2022;26:51–89. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herek GM, Garnets LD. Sexual orientation and mental health. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:353–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:1019–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pachankis JE, Bränström R. Hidden from happiness: structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:403–15. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hickson F, et al. Hidden from health: structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and HIV across 38 countries in the European MSM Internet Survey. AIDS. 2015;29:1239–46. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Bränström R, et al. Structural stigma and sexual minority men’s depression and suicidality: a multilevel examination of mechanisms and mobility across 48 countries. J Abnorm Psychol. 2021;130:713–26. doi: 10.1037/abn0000693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.English D, Rendina HJ, Parsons JT. The effects of intersecting stigma: a longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among Black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychol Violence. 2018;8:669–79. doi: 10.1037/vio0000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Minority stress among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) university students in ASEAN countries: associations with poor mental health and addictive behavior. Gend Behav. 2016;14:7806–15. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun S, Pachankis JE, Li X, Operario D. Addressing minority stress and mental health among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17:35–62. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00479-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao S, Mason CD. Minority stress and well-being under anti-sodomy legislation in India. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2018;5:432–44. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kittiteerasack P, Matthews AK, Steffen A, et al. The influence of minority stress on indicators of suicidality among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults in Thailand. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2021;28:656–69. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun S, Budge S, Shen W, Xu G, Liu M, Feng S. Minority stress and health: a grounded theory exploration among men who have sex with men in China and implications for health research and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2020;252:112917. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu Y, Meyers K, Xie L. HIV risk management among sexual minority men in China: context, lived experience, and implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation. Cult Health Sex. 2021 doi: 10.1080/13691058.2021.1885740. published online Feb 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan H, Li X, Li J, et al. Association between perceived HIV stigma, social support, resilience, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms among HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) in Nanjing, China. AIDS Care. 2019;31:1069–76. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1601677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adia AC, Bermudez ANC, Callahan MW, Hernandez LI, Imperial RH, Operario D. “An evil lurking behind you”: drivers, experiences, and consequences of HIV-related stigma among men who have sex with men with HIV in Manila, Philippines. AIDS Educ Prev. 2018;30:322–34. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2018.30.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Earnshaw VA, Jin H, Wickersham JA, et al. Stigma toward men who have sex with men among future healthcare providers in Malaysia: would more interpersonal contact reduce prejudice? AIDS Behav. 2016;20:98–106. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1168-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Philbin MM, Hirsch JS, Wilson PA, Ly AT, Giang LM, Parker RG. Structural barriers to HIV prevention among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Vietnam: diversity, stigma, and healthcare access. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chuang DM, Newman PA, Fang L, Lai MC. Syndemic conditions, sexual risk behavior, and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Taiwan. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:3503–18. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang H, Li J, Tan Z, et al. Syndemic factors and HIV risk among men who have sex with men in Guangzhou, China: evidence from synergy and moderated analyses. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49:311–20. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ng RX, Guadamuz TE, Akbar M, Kamarulzaman A, Lim SH. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health conditions and HIV infection among MSM in Malaysia: implication of a syndemic effect. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31:568–78. doi: 10.1177/0956462420913444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hagopian A, Rao D, Katz A, Sanford S, Barnhart S. Anti-homosexual legislation and HIV-related stigma in African nations: what has been the role of PEPFAR? Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1306391. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1306391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anderson AM, Ross MW, Nyoni JE, McCurdy SA. High prevalence of stigma-related abuse among a sample of men who have sex with men in Tanzania: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2015;27:63–70. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.951597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cange CW, LeBreton M, Billong S, et al. Influence of stigma and homophobia on mental health and on the uptake of HIV/sexually transmissible infection services for Cameroonian men who have sex with men. Sex Health. 2015;12:315–21. doi: 10.1071/SH15001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cloete A, Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Henda N. Stigma and discrimination experiences of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1105–10. doi: 10.1080/09540120701842720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stahlman S, Grosso A, Ketende S, et al. Depression and social stigma among MSM in Lesotho: implications for HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:1460–69. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1094-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stannah J, Dale E, Elmes J, et al. HIV testing and engagement with the HIV treatment cascade among men who have sex with men in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2019;6:e769–87. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiginton JM, Murray SM, Poku O, et al. Disclosure of same-sex practices and experiences of healthcare stigma among cisgender men who have sex with men in five sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:2206. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12151-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adeboye A, Ross MW, Wilkerson MJ, et al. Syndemic production of HIV infection among Tanzanian MSM. J Health Educ Res Dev. 2017;5:1000231 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gyamerah AO, Taylor KD, Atuahene K, et al. Stigma, discrimination, violence, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men in four major cities in Ghana. AIDS Care. 2020;32:1036–44. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1757020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kennedy CE, Baral SD, Fielding-Miller R, et al. “They are human beings, they are Swazi”: intersecting stigmas and the positive health, dignity and prevention needs of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Swaziland. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(suppl 3):18749. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.4.18749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ogunbajo A, Oke T, Jin H, et al. A syndemic of psychosocial health problems is associated with increased HIV sexual risk among Nigerian gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) AIDS Care. 2020;32:337–42. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1678722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsang EY, Qiao S, Wilkinson JS, Fung AL, Lipeleke F, Li X. Multilayered stigma and vulnerabilities for HIV infection and transmission: a qualitative study on male sex workers in Zimbabwe. Am J Men Health. 2019;13:1557988318823883. doi: 10.1177/1557988318823883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gómez F, Cumsille P, Barrientos J. Mental health and life satisfaction on Chilean gay men and lesbian women: the role of perceived sexual stigma, internalized homophobia, and community connectedness. J Homosex. 2021 doi: 10.1080/00918369.2021.1923278. published online June 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lawrenz P, Habigzang LF. Minority stress, parenting styles, and mental health in Brazilian homosexual men. J Homosex. 2020;67:658–73. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2018.1551665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Perez-Brumer AG, Passaro RC, Oldenburg CE, et al. Homophobia and heteronormativity as dimensions of stigma that influence sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men (MSM) and women (MSMW) in Lima, Peru: a mixed-methods analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:617. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6956-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rentería R, Benjet C, Gutierrez-Garcia RA, et al. Suicide thought and behaviors, non-suicidal self-injury, and perceived life stress among sexual minority Mexican college students. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:891–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Andrewin A, Chien LY. Stigmatization of patients with HIV/AIDS among doctors and nurses in Belize. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:897–906. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann L, et al. The ecology of sexual health of sexual minorities in Guatemala City. Health Promot Int. 2015;30:832–42. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alvarado B, Mueses HF, Galindo J, Martínez-Cajas JL. Application of the “syndemics” theory to explain unprotected sex and transactional sex: a crosssectional study in men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women, and non-MSM in Colombia. Biomédica. 2020;40:391–403. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Boni RB, Machado IK, De Vasconcellos MTL, et al. Syndemics among individuals enrolled in the PrEP Brasil Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:168–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Semple SJ, Stockman JK, Goodman-Meza D, et al. Correlates of sexual violence among men who have sex with men in Tijuana, Mexico. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46:1011–23. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0747-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Layland EK, Carter JA, Perry NS, et al. A systematic review of stigma in sexual and gender minority health interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10:1200–10. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang Y-T, Ma YT, Craig SL, Wong DFK, Forth MW. How intersectional are mental health interventions for sexual minority people? A systematic review. LGBT Health. 2020;7:220–36. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Safren SA, Blashill AJ, O’Cleirigh CM. Promoting the sexual health of MSM in the context of comorbid mental health problems. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(suppl 1):S30–34. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9898-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reisner SL, O’Cleirigh C, Hendrikson ES, et al. “40 & Forward”: preliminary evaluation of a group intervention to improve mental health outcomes and address HIV sexual risk behaviors among older gay and bisexual men. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2011;24:523–45. [Google Scholar]

- 93.O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA, Taylor SW, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care (CBT-TSC) in men who have sex with men with a history of childhood sexual abuse: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:2421–31. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02482-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Safren SA, Thomas B, Biello KB, et al. Strengthening resilience to reduce HIV risk in Indian MSM: a multicity, randomised, clinical efficacy trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e446–55. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pachankis JE, McConocha EM, Reynolds JS, et al. Project ESTEEM protocol: a randomized controlled trial of an LGBTQ-affirmative treatment for young adult sexual minority men’s mental and sexual health. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1086. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis JE. Acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-affirmative mental health practice training in a highly stigmatizing national context. LGBT Health. 2017;4:360–70. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pan S, Sun S, Li X, et al. A pilot cultural adaptation of LGB-affirmative CBT for young Chinese sexual minority men’s mental and sexual health. Psychotherapy. 2021;58:12–24. doi: 10.1037/pst0000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang JP, Simoni JM, Dorsey S, et al. Reducing distress and promoting resilience: a preliminary trial of a CBT skills intervention among recently HIV-diagnosed MSM in China. AIDS Care. 2018;30(suppl 5):S39–48. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1497768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Moody RL, Gurung S, Starks TJ, Pachankis JE. Feasibility of an emotion regulation intervention to improve mental health and reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors for HIV-positive gay and bisexual men with sexual compulsivity. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1540–49. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1533-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gayner B, Esplen MJ, DeRoche P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to manage affective symptoms and improve quality of life in gay men living with HIV. J Behav Med. 2012;35:272–85. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Carrico AW, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a positive affect intervention to reduce HIV viral load among sexual minority men who use methamphetamine. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25436. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bogart LM, Dale SK, Daffin GK, et al. Pilot intervention for discrimination-related coping among HIV-positive Black sexual minority men. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2018;24:541–51. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hergenrather KC, Geishecker S, Clark G, Rhodes SD. A pilot test of the HOPE intervention to explore employment and mental health among African American gay men living with HIV/AIDS: results from a CBPR study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25:405–22. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.5.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Affun-Adegbulu C, Adegbulu O. Decolonising global (public) health: from Western universalism to global pluriversalities. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002947. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McNamara RA, Naepi S. Decolonizing community psychology by supporting indigenous knowledge, projects, and students: lessons from Aotearoa New Zealand and Canada. Am J Community Psychol. 2018;62:340–49. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wampold BE. Psychotherapy: the humanistic (and effective) treatment. Am Psychol. 2007;62:855–73. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang BC, Chu QS. MSM and HIV/AIDS in China. Cell Res. 2005;15:858–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sanders EJ, Okuku HS, Smith AD, et al. High HIV-1 incidence, correlates of HIV-1 acquisition, and high viral loads following seroconversion among MSM. AIDS. 2013;27:437–46. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b0f81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kombo B, Sariola S, Gichuru E, Molyneux S, Sanders EJ, van der Elst E. “Facing our fears”: using facilitated film viewings to engage communities in HIV research involving MSM in Kenya. Cogent Med. 2017;4:1330728. doi: 10.1080/2331205X.2017.1330728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Micheni M, Rogers S, Wahome E, et al. Risk of sexual, physical and verbal assaults on men who have sex with men and female sex workers in coastal Kenya. AIDS. 2015;29(suppl 3):S231–36. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Secor AM, Wahome E, Micheni M, et al. Depression, substance abuse and stigma among men who have sex with men in coastal Kenya. AIDS. 2015;29(suppl 3):S251–59. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Korhonen C, Kimani M, Wahome E, et al. Depressive symptoms and problematic alcohol and other substance use in 1476 gay, bisexual, and other MSM at three research sites in Kenya. AIDS. 2018;32:1507–15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.van der Elst EM, Kombo B, Gichuru E, et al. The green shoots of a novel training programme: progress and identified key actions to providing services to MSM at Kenyan health facilities. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20226. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gichuru E, Kombo B, Mumba N, Sariola S, Sanders EJ, van der Elst EM. Engaging religious leaders to support HIV prevention and care for gays, bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men in coastal Kenya. Crit Public Health. 2018;28:294–305. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2018.1447647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.van der Elst EM, Mudza R, Onguso JM, et al. A more responsive, multi-pronged strategy is needed to strengthen HIV healthcare for men who have sex with men in a decentralized health system: qualitative insights of a case study in the Kenyan coast. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(suppl 6):e25597. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Graham SM, Micheni M, Chirro O, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the Shikamana intervention to promote antiretroviral therapy adherence among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Kenya: feasibility, acceptability, safety and initial effect size. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2206–19. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02786-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dijkstra M, Mohamed K, Kigoro A, et al. Peer mobilization and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) partner notification services among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and transgender women in coastal Kenya identified a high number of undiagnosed HIV infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab219. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Van der Elst EM, Mbogua J, Operario D, et al. High acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis but challenges in adherence and use: qualitative insights from a phase I trial of intermittent and daily PrEP in at-risk populations in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2162–72. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0317-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.van der Elst EM, Smith AD, Gichuru E, et al. Men who have sex with men sensitivity training reduces homoprejudice and increases knowledge among Kenyan healthcare providers in coastal Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(suppl 3):18748. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.4.18748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Moagi MM, van Der Wath AE, Jiyane PM, Rikhotso RS. Mental health challenges of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: an integrated literature review. Health SA. 2021;26:1487. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v26i0.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Argüello TM. Decriminalizing LGBTQ+: reproducing and resisting mental health inequities. CNS Spectr. 2020;25:667–86. doi: 10.1017/S1092852920001170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kealy-Bateman W, Pryor L. Marriage equality is a mental health issue. Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:540–43. doi: 10.1177/1039856215592318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hoff CC, Campbell CK, Chakravarty D, Darbes LA. Relationship-based predictors of sexual risk for HIV among MSM couples: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2873–92. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Casey LJ, Wootton BM, McAloon J. Mental health, minority stress, and the Australian Marriage Law postal survey: a longitudinal study. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90:546–56. doi: 10.1037/ort0000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, Patel V. Psychological treatments for the world: lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:149–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]