Abstract

Euphyllophytes encompass almost all extant plants, including two sister clades, ferns and seed plants. Decoding genomes of ferns is the key to deep insight into the origin of euphyllophytes and the evolution of seed plants. Here, we report a chromosome-level genome assembly of Adiantum capillus-veneris L., a model homosporous fern. This fern genome comprises 30 pseudochromosomes, with a size of 4.8-gigabase and a contig N50 length of 16.22 Mb. Gene co-expression network analysis uncovered that homospore development, in ferns, has relatively high genetic similarities with the pollen in seed plants. Analyzing fern defense response expanded the understanding of evolution and diversity in endogenous bioactive jasmonates in plants. Moreover, comparing ferns’ genomes with those of other land plants reveals changes in gene families important for the evolutionary novelties, within the euphyllophyte clade. These results lay a foundation for studies on fern genome evolution and function, as well as the origin and evolution of euphyllophytes.

Introduction

Ferns are among the most ancient, and ecologically prominent, vascular lineages of the Earth’s terrestrial flora1,2. Ferns contain about 12,000 species, being the second-largest group of vascular plants2. Due to its phylogenetic position as the closest sister linage to seed plants3, ferns are an essential lineage for understanding land plant evolution, especially for comparative analysis of ancestral characteristics in euphyllophytes4–6.

Unlike the exclusively heterosporous seed plants, ferns encompass both homosporous and heterosporous members, which differ dramatically in habitat preference, reproduction, and genome size1,7,8. The homosporous ferns are largely terrestrial and form the overwhelming majority, accounting for 99% of extant species2,6. They produce a single type of spore that typically germinates into a bisexual gametophyte. The heterosporous species are aquatic, including only 85 species, which produce male and female spores that develop into a unisexual gametophyte1. Genetically, the genome size of homosporous ferns is on average 12 Gb, which is considerably larger than that of heterosporous ferns (~2.4 Gb)1,7. Given the relatively small genome of heterosporous ferns, the reference genomes of Azolla filiculoides and Salvinia cucullata have been reported8. Unfortunately, the high-quality homosporous fern genome assembly was still scarce9, thus far, which has limited not only studies on their reproductive biology and molecular genetics, but also the construction of a comparative framework in land plants5,6,10.

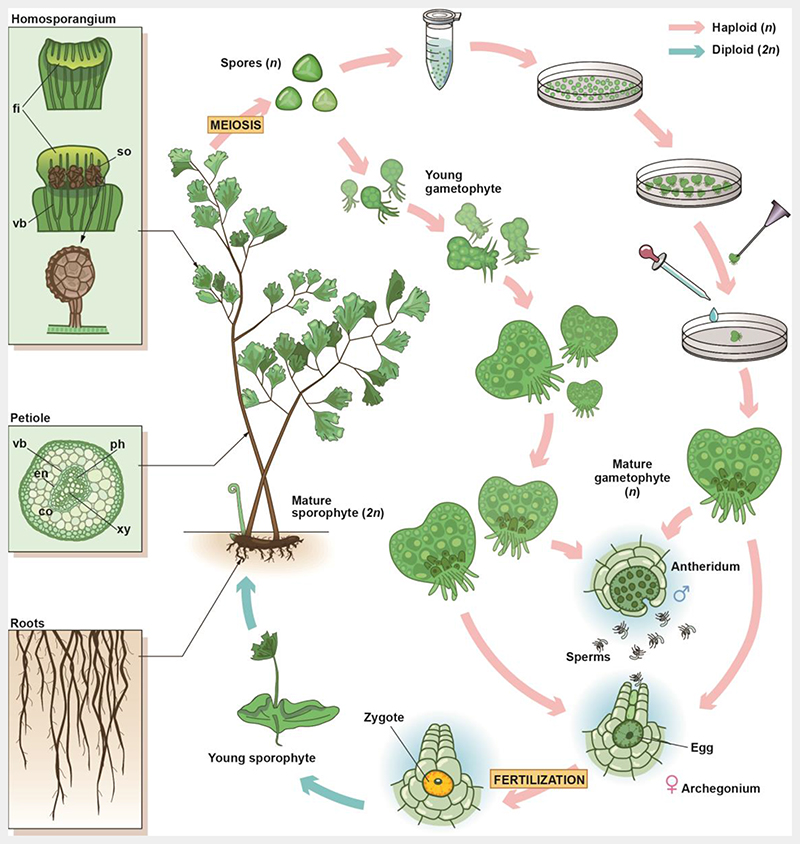

The maidenhair fern (Adiantum capillus-veneris L., hereafter referred to as A. capillus-veneris) is a popular ornamental plant (Fig. 1). Because of the comprehensive morphological observation of its entire life cycle11, A. capillus-veneris has long been used as a model fern for studying photobiology12,13, and gametophyte and sporophyte development6,11, and has the potential for studying sporangium development11. Phylogenetically, A. capillus-veneris belongs to the polypods that include more than 80% of the extant ferns, thus a good representative of homosporous ferns2,14. Moreover, a capacity for intra-gametophytic selfing makes A. capillus-veneris ideal for a genomics study, as completely homozygous diploid plants can be developed under laboratory conditions11. These attributes make A. capillus-veneris an excellent subject for genomics studies of homosporous ferns.

Fig. 1. Life cycle and intra-gametophytic selfing of A. capillus-veneris.

A. capillus-veneris is a typical homosporous fern with a creeping rhizome grown underground and pinnate fronds emerging from the rhizome. The A. capillus-veneris fronds play roles in both photosynthesis and reproduction. Margins of the frond backscroll to form false indusia, and subsequently, sori develop on the abaxial side at the terminal region of the vascular bundles (see upper left inset). Each sori contains many sporangia, and within each sporangium, the spore mother cells undergo meiosis to form four haploid spores. The spores are released from the sporangium and they then grow into a filament, heart-shaped, and finally into mature prothallus, called gametophytes. The male sex organ, the antheridium, and the female sex organ, the archegonium, form on the gametophyte to produce sperms and an egg, respectively. If moisture is plentiful, the sperms swim to an archegonium for fertilization. Under natural conditions, the antheridia and archegonia mature at different times to promote cross-fertilization. In this study, spores were sterilized and spread on Petri dishes. When spores germinated and developed into prothalli, a needle was used to pick up one heart-shaped prothallus to transfer it to a new Petri dish. During the development of this prothallus, until sexual maturity, it was irrigated with Knop’s liquid medium to promote its self-fertilization, and finally, generation of an homozygous diploid. Ph, phloem; xy, xylem; vb, vascular bundle; en, endodermis; co, cortex; fi, false indusium; so, sori.

Results

The chromosome-level genome of A. capillus-veneris

To develop a high-quality fern genome, we first generated a completely homozygous diploid A. capillus-veneris (Supplementary Fig. 1a), via intra-gametophytic selfing (Fig. 1), to simplify sequencing. The genome size was about 4.95 Gb based on the k-mer analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The resultant diploid fern was then sequenced, using a combination of PacBio long-read (126×), Illumina paired-ends (68×), Hi-C sequence (551.74 Mb valid data), as well as BioNano optical map data (141.32×; Supplementary Table 1-4). We finally assembled a 4.83 Gb genome that comprises 2,081 contigs, with a contig N50 length of 16.22 Mb, covering 97.58% of the estimated genome size (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5), and 98.79% of the sequences were assigned to 30 chromosomes (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1b, and Supplementary Table 6).

Table 1. Characteristics of the A. capillus-veneris genome.

| Genome | ||

| Size (Gb) | 4.83 | |

| Contig N50 (Mb) | 16.22 | |

| Contig number | 2,081 | |

| Sequence anchored on chromosome (%) | 98.8 | |

| Gap number | 928 | |

| Gap ratio (%) | 0.26 | |

| GC content (%) | 41.71 | |

| High-copy repeat content (%) | 85.25 | |

| Protein-coding gene | Average | |

| Gene length (bp) | 23,212 | |

| CDS length (bp) | 1,150 | |

| Exon length (bp) | 284 | |

| Intron length (bp) | 4,844 | |

| Exon number per gene | 5.01 | |

| Gene number | 31,244 | |

| Noncoding loci | Number | Total (bp) |

| lncRNA | 6,541 | 10,447,168 |

| miRNA | 80 | 8,405 |

| tRNA | 1,624 | 120,735 |

| rRNA | 540 | 491,460 |

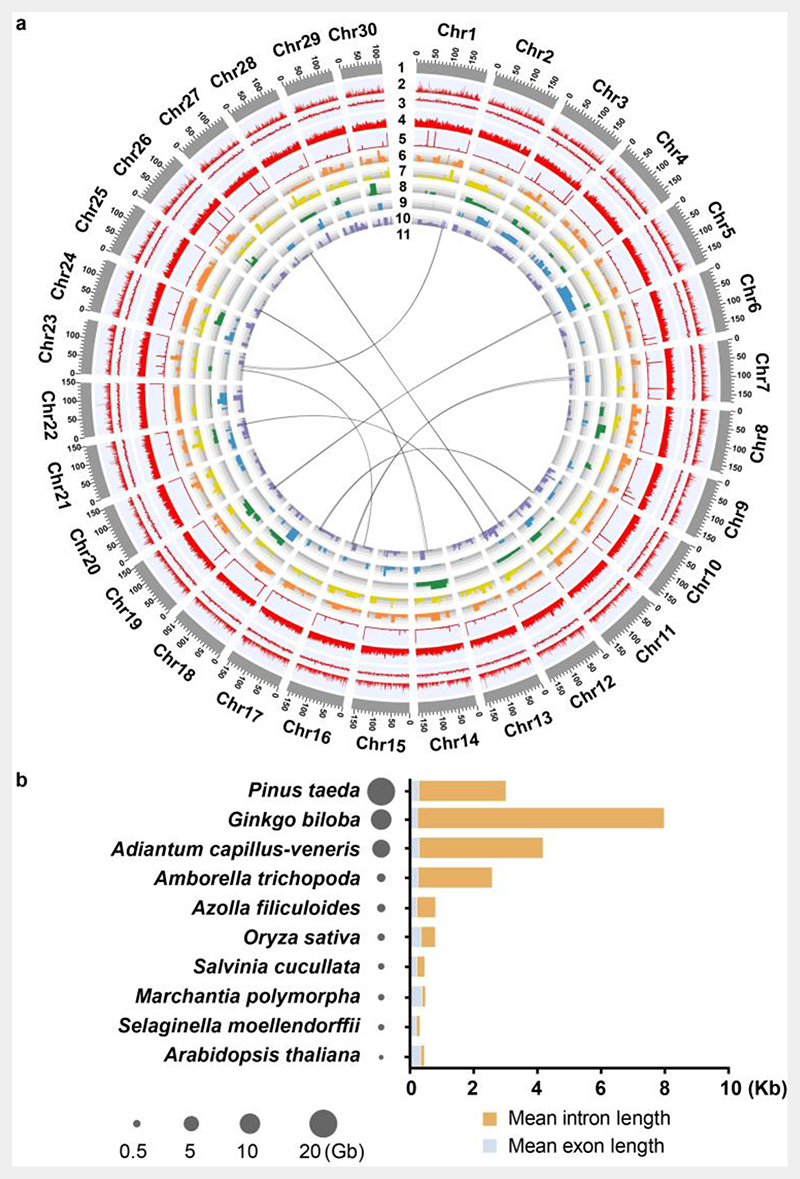

Fig. 2. A. capillus-veneris de novo genome assembly.

a. Summary of the de novo genome assembly and sequencing analysis of A. capillus-veneris. 1: chromosome length, 2: gene number, 3: GC content, 4: repeat density, 5: rRNA, 6-10: organ-specific expression genes, in which 6: gametophytes, 7: stems, 8: young-fronds, 9: sporangium-excised leaves, 10: sporangia, 11: syntenic blocks.

b. Distribution of intron and exon lengths, from ten representative species in land plants. The genome sizes of the ten species are indicated by the size of the circles.

A. capillus-veneris genome is highly repetitive with a total of 4.11 Gb repetitive sequences annotated, accounting for 85.25% of the genome length (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 7). The distribution of repeat elements of A. capillus-veneris varied across the chromosomes. Two of the dominant subfamilies of long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs), Gypsy and Copia, were distributed in gene-poor regions (Supplementary Fig. 2). Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) clusters, which were identified using a hidden Markov model (HMM)-searching-based program, were mostly embedded within repetitive regions that are rich in Gypsy and Copia. And the most prominent rRNA clusters were found on chromosomes 3 and 23 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2).

To perform gene prediction, we collected nineteen tissue samples (Supplementary Table 8) and generated corresponding transcriptomes, covering the entire A. capillus-veneris life cycle. In total, 31,244 nuclear-encoded genes were annotated with high confidence, and most of them were supported by the transcript evidence and/or having significant similarities to other known plant proteins (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 9).

To further evaluate genome quality, we aligned 949,845,898 Illumina transcriptome sequencing reads to the genome assembly and obtained a 95.44% mapping rate (Supplementary Table 8). The 30,540 expressed sequence tags (ESTs) were also used to test genome coverage, and 97.90% could be mapped onto the chromosome sequences (Supplementary Table 10). Moreover, the whole-genome optical (BioNano) mapping rate was 97.05%, with only 2 chimera contigs and no indels that are larger than 5 Kb (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 10). These results demonstrated that our assembly achieved high continuity and completeness.

The lack of recent WGD events in A. capillus-veneris

The genome size of A. capillus-veneris was 6.4 times larger than that of A. filiculoides (0.75 Gb) and 19.2 times larger than that of S. cucullata (0.26 Gb) (Fig. 2b). One of the reasons for plant genome size expansion is the occurrence of a whole genome duplication (WGD) event. To investigate A. capillus-veneris WGD events, we performed the intragenomic collinear analysis by MCScanX15 based on all-against-all BLASTP16 alignments. However, only 96 syntenic paralogues in 7 collinear gene blocks could be identified, which accounted for just 0.31% of the total genes. As shown in the dot plot for relationships among syntenic segments (Supplementary Fig. 4a), the distribution of collinear blocks was too sparse to support any large-scale duplication in A. capillus-veneris. Furthermore, both distributions of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (KS) for the whole paranome and syntenic paralogues within A. capillus-veneris exhibited no significant peaks supporting a recent whole-genome duplication (Supplementary Fig. 4b-c). These results demonstrated that no recent WGD occurred in the A. capillus-veneris genome, suggesting that WGD is not the main contributor to the expansion of A. capillus-veneris genome size.

However, the KS distributions for the whole paranome of A. capillus-veneris shows an obscure peak with a KS value over two (Supplementary Fig. 4b), which may lend some support to an ancient WGD. Similarly, the KS distributions for the paralogues located on collinear gene blocks, despite of the limited number thereof, shows a peak with a KS value over two (Supplementary Fig. 4c). A previous study from OneKP Initiative proposed the existence of an ancient WGD, which occurred before the diversification of polypod ferns (“PTERa”)17, a fern family including A. capillus-veneris2, but another study has shed doubt on the “PTERa” existence by comprehensively analyzing transcriptome covering all major fern clades18. We thus wonder if the obscure peak at KS value over two represented the remnants of such “PTERa” WGD. As the variation of substitution rates among species could affect the phylogenetic placement of a WGD event with respect to speciation events19, we employed the newly-developed approach ksrates19 to correct for the different synonymous substitution rates among A. capillus-veneris, A. filiculoides, and S. cucullata, using Lygodium japonicum as an outgroup and to adjust the value of KS peaks representing speciation events. Without correction, we found that the KS value (2.32) representing the divergence between S. cucullata and A. capillus-veneris is larger than the KS value (2.11) representing the divergence between A. filiculoides and A. capillus-veneris (Supplementary Fig. 4d). As both the KS values represent the same speciation event, our results demonstrated that S. cucullata has a higher synonymous substitution rate than that of A. filiculoides. Therefore, we corrected the differences in the synonymous substitution rate of S. cucullata and A. filiculoides with that of A. capillus-veneris, respectively. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4e-f, both KS distributions for the whole paranome and syntenic paralogues of A. capillus-veneris supported a WGD event that occurred slightly before but largely overlapped with the divergence between A. capillus-veneris and A. filiculoides or S. cucullata. The WGD event represented an ancient WGD event shared by all the core leptosporangiate species, in consistent with the previous study8, but not the “PTERa” WGD. In conclusion, these results showed that A. capillus-veneris only experienced the common ancient WGD on the branch leading to core leptosporangiate, but no additional round of recent WGD recurred in its genome.

Repeat element is the distinguishing genomic feature of homosporous from heterosporous ferns

We found that the repeat elements of A. capillus-veneris were 4.11 Gb in size, accounting for 85.25% of the genome size (Supplementary Table 7), which was much larger than the sizes of the repeat elements of A. filiculoides (312 Mb, 41.60%) and S. cucullata (90 Mb, 34.62%)8. The LTR-RTs are the dominant components in A. capillus-veneris genome, with 1.80 Gb size that is much larger than those in the two heterosporous ferns (Supplementary Fig. 5a). To investigate the LTR-RTs diversification, we further calculated the nucleotide distance (D) to infer insertion and elimination rates. It was observed that half of the LTR-RTs D value in A. capillus-veneris was much bigger (2.20, Supplementary Fig. 5b) than those in the two heterosporous ferns, A. filiculoides (0.47) and S. cucullata (1.41), indicating an early-burst and continued LTR-RTs insertions in A. capillus-veneris. However, A. capillus-veneris had the highest elimination ratio (the solo LTR-RTs / the intact LTR-RTs) that is up to 4.66, compared with 3.84 and 3.86 in A. filiculoides and S. cucullata, respectively. Despite the high purging rate, the continued insertions still led to a dramatic accumulation of LTR-RTs in A. capillus-veneris. Taken together, these findings showed that the expansion of repeat elements underlies the genome enlargement of the homosporous ferns.

Interestingly, we found that the average gene size of A. capillus-veneris (23,212 bp) was much larger than those in the heterosporous ferns (A. filiculoides, 5,000 bp; S. cucullata, 3,446 bp). However, the mean exon size and mean exon number per gene, were similar among these three species, consistent with their similar transcript length (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Thus, the notable characteristic of the gene structures in A. capillus-veneris was an expanded intron size (up to 4,844 bp of mean intron length). Further 88.98% of introns contain repeat elements. One class of repeat elements, enriched in the introns, was the LTR-RTs, which accounted for 52.47% (Supplementary Table 11), which is higher than its percentage in the whole genome (37.26%, Supplementary Table 7). The other class was long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), which were enriched in introns (16.94%, Supplementary Table 11) compared with the whole genome (3.87%, Supplementary Table 7). These results suggested that LTR-RTs and LINEs were the important repeat elements that contributed to the extension of intron length in A. capillus-veneris. Similar results could also be observed in other larger plant genomes (Fig. 2b). For example, in Gingko. biloba, LTR-RTs also contributed the most to intron expansion, followed by LINEs (Supplementary Table 12). These findings imply that, in plants, genome size might positively correlate with the average intron length.

Homosporangium exhibits genetic similarities with pollens

Homosporous ferns feature a unique sexual reproductive process, characterized by morphologically identical spores that germinate to produce bisexual gametophytes. To explore the genetic basis underlying this distinctive developmental process, we collected sporangium tissues from A. capillus-veneris pinnae over different developmental stages, including juvenile (JS), green (GS), and mature sporangiums (MS), as well as the corresponding remaining part of the pinna (i.e. juvenile sporangium vs juvenile-sporangium-excised leaf) (Fig. 3a). Based on transcriptome datasets of these tissues (Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6), distinct gene transcripts that are differentially expressed in sporangia at a given stage (i.e. tissue-enriched genes) were identified by comparing sporangium transcripts in a given stage with transcripts detected from the sporangium-excised region at the same stage (log FC > 1; q-value < 0.05).

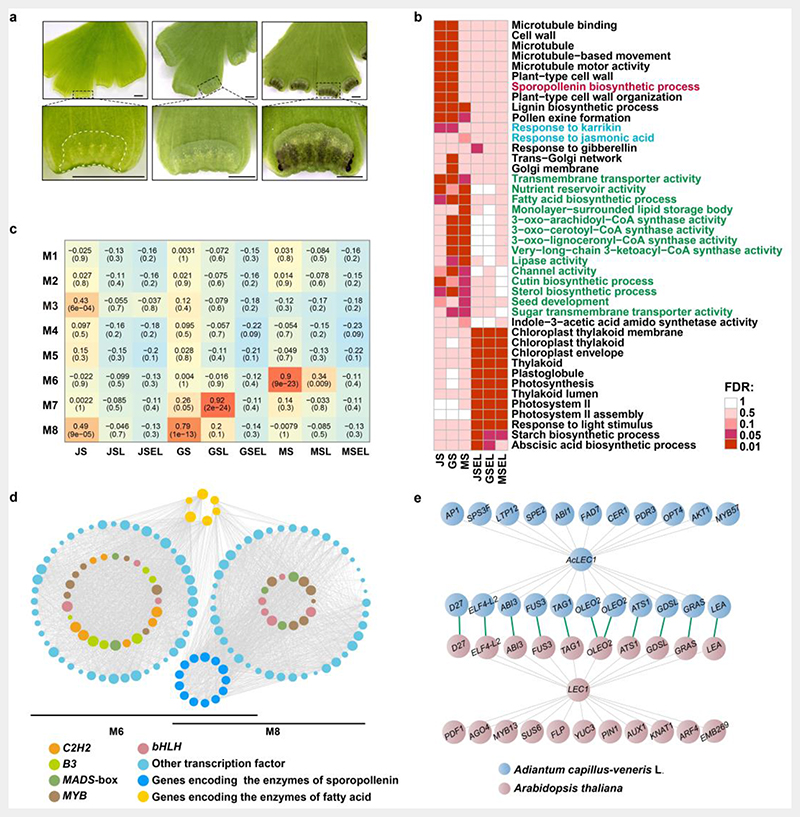

Fig. 3. Expression profile and gene network analysis during homosporangium development.

The top row shows the underside (adaxial side) of pinnae (leaves) with sporangia in three developmental stages. From left to right are the juvenile, green, and mature stages. Bar = 1 mm. The margins of the pinnae in boxes are enlarged into the images in the second row to show curled false indusia and adaxial generated sori. The false indusium with homosporangium was also outlined by a white dash line. Bar = 1 mm.

b. Heat map visualization of representative gene ontology (GO) terms for tissue-enriched genes. The colors from red to white indicate false discovery rate (FDR) as follows: 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, and 1, respectively. The listed GO terms are for significant differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.01). JS, juvenile sporangium; GS, green sporangium; MS, mature sporangium; JSEL, juvenile-sporangium-excised leaf; GSEL, green-sporangium-excised leaf; MSEL, mature-sporangium-excised leaf. Functions related to storage compound accumulation are indicated in green; functions related to the stress response are indicated in blue; functions related to spore development are indicated in red.

c. Heatmap of the correlations between the detected co-expression modules (M1-M8) and the indicated homosporangium tissues. The heatmap indicates the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) value from the correlation analysis of the overrepresentation of genes and the various tissues. Boxes contain the PCC value and P-value from the correlation analysis.

d. Regulatory network and the connection among transcription factors (TFs) and structural genes involved in sporopollenin (light blue point) and fatty acid (orange point) biosynthesis. The size of the point areas represents the copy numbers. The left and right TF circles are based on the M8 and M6 co-expression modules, respectively.

e. The LEC1 regulatory networks in A. capillus-veneris and Arabidopsis. All orthologous relationships are linked with green lines, and co-expression genes are linked by gray lines.

Gene ontology (GO) analyses showed that the differentially expressed genes in JS and GS were enriched significantly in terms associated with the cytoskeleton formation and cell wall organization (Fig. 3b and see Extended Data Table 2 for detailed results), suggesting that cell growth might remain quite active in early homosporangium. The JS and GS featured a total of 17 differentially expressed genes related to sporopollenin biosynthesis, the main constituent of the exine layer in pollen (a microspore) (Extended Data Table 2). Furthermore, the determinants, such as EMS1 (EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES 1) and TPD1 (TAPETUM DETERMINANT 1), for specification of the tapetum where sporopollenin precursor synthesis occurs, exhibited high expression in these two stages (Extended Data Table 2). These findings are consistent with the initiation of reproductive sporogenous tissue and biomass increase during early sporangium development. In addition, mRNAs were enriched in fatty acid biosynthesis in MS (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Table 2), which might be associated with the presence of storage molecules in the homospores20. Besides, we also performed GO analysis for genes enriched in the lamina part of pinnae and found that tissue-enriched genes were significantly correlated with carbon and nitrogen metabolism, consisting with the photosynthetic activities (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Table 2).

To further decipher the homosporangium development, we used weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to cluster co-expression modules, and detected hub genes and transcription factors. A total of 6,774 sporangium-specifically-expressed genes clustered into 8 co-expression modules, where three modules, namely M3, M8, and M6, were significantly (P-value < 0.01) correlated with JS, GS, and MS developmental phases, respectively (Fig. 3c). In the JS-related M3 module, the top 30 hub genes, such as Adc05362, Adc04605, and Adc09499, were associated with peroxidase activity, long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase activity, and the suberin biosynthetic process (Extended Data Table 3), whereas the top 30 hub genes in the GS-related M8 module, such as Adc06947 and Adc16154, were involved in the sugar biosynthesis and transport process (Extended Data Table 3), indicating that mainly metabolite biosynthesis activities were distinct in early homosporangium development.

The M6 module included 1,826 genes (Extended Data Table 3). Six of them were annotated as dehydration response genes, including the DSP-2221 homolog (Adc01719), four late embryogenesis abundant22 homologs (Adc15827, Adc19793, Adc19794, and Adc22177), and one dehydration response protein23 homolog (Adc22954), implying a transition from rapid cell division and metabolism biosynthesis activities, during early homosporangium development, to the acquisition of desiccation tolerance in the late stage (Extended Data Table 3). In addition, 92 transcription factor genes (TFs) in M6 were grouped into 39 gene families and 7.60% of them coded for homologs in the B3 gene family, making it the family with the most TFs within the M6 module (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Table 3). Certain members of this B3 gene family, such as ABI3 and FUS3, represent key regulators for the accumulation of starch and storage protein24, suggesting that nutrient accumulation pathways were active during homosporangium maturation. At the same time, co-expression modules contained numerous genes that are not yet well annotated (Extended Data Table 3). More experimental evidence will be required to explore the function of these genes in homosporangium development.

Insights into the LEC1 network associated with seed origin

Previous studies demonstrated that LEC1 can recruit ABI3 and FUS3 to form a gene regulatory network to execute adaptive physiological characteristics, such as storage compound accumulation, desiccation tolerance and dormancy acquisition, and functions as a master regulator of seed development in these plants25–28. In A. capillus-veneris, the homologous gene, AdcLEC1, exhibits a clear specific expression pattern in mature homosporangia and is co-expressed with AdcABI3 and AdcFUS3 within the mature-homosporangium-related M6 module (Extended Data Table 4 and Fig. 3e), which parallels the activation of LEC1 on both ABI3 and FUS3 in Arabidopsis seeds24, implying that an AdcLEC1 gene regulation network might play roles in homosporangium development.

To further assess the functional conservation of a LEC1 regulation network in homospory and the seed, we filtered out 1,390 genes co-expressed with AdcLEC1 (r > 0.5) and subsequently compared them with 1,515 co-expressed genes of AtLEC1 in Arabidopsis29, via BLAST. Here, we found that 190 A. capillus-veneris and 261 Arabidopsis genes overlapped in the two gene sets (Extended Data Table 4), and 1,200 and 1,254 were specific in A. capillus-veneris and Arabidopsis, respectively (Extended Data Table 4). Apart from conserved TFs (AdcFUS3, AdcABI3, AdcGRAS), some orthologs encoding seed-specific storage proteins, such as AdcOLEOSIN and AdcLEA, were detected in both the Arabidopsis and A. capillus-veneris LEC1 networks (Extended Data Table 4 and Fig. 3e), suggesting a similar molecular mechanism for the LEC1-mediated storage protein accumulation between A. capillus-veneris and Arabidopsis24,30–32.

As shown in Fig. 3e, the core components of a LEC1-related network are conserved in both A. capillus-veneris and Arabidopsis. Genes unique in the AdcLEC1 network were enriched in nutrient reservoirs and responses to karrikin, abscisic acid, and salicylic acid, whereas those unique in the Arabidopsis LEC1 network were enriched in the photosystem and seed maturation (Extended Data Table 4). In the lycophytes, the closest sister group of the euphyllophytes, the Selaginella moellendorffii LEC1 mRNA is detected in both reproductive and vegetative organs, which contain storage lipids33, indicating that LEC1 is functionally conserved in assimilation accumulation since it originated in lycophyte, whereas its regulatory function for assimilation accumulation was specialized within the reproductive organ in the euphyllophytes.

Molecular evolution of jasmonate signaling in plant defense

Ferns are highly resistant to insect pests and pathogens, with their rate of insect infestation being 30-fold lower than that of flowering plants34,35, reflecting the value of ferns as a source for increasing insect resistance in plant breeding programs. Studies with ferns have suggested that jasmonate (JA) signaling might be an important contributor to the strong pathogen resistance of ferns36. For an in-depth analysis of JA signaling, in ferns, we performed mechanical wounding assays on fern fronds, which partially mimicked insect herbivory. Transcriptome analyses showed that expression of the majority of JA biosynthesis genes was induced, among which AdcLOX8/14/15/17, AdcAOS3/6, AdcOPR2/11 and AdcJAR2/3/4 exhibited significant up-regulation within 0.5 h after wounding (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 7, and Extended Data Table 5). These results indicated that wounding could trigger rapid JA biosynthesis in ferns. Moreover, the levels of AOS3/6 and AOC1, rate-limiting enzymes in the JA biosynthesis pathway, increased continuously within 8 h of wounding (Fig. 4a), suggesting that wound-inducible synthesis of JA was sustainable.

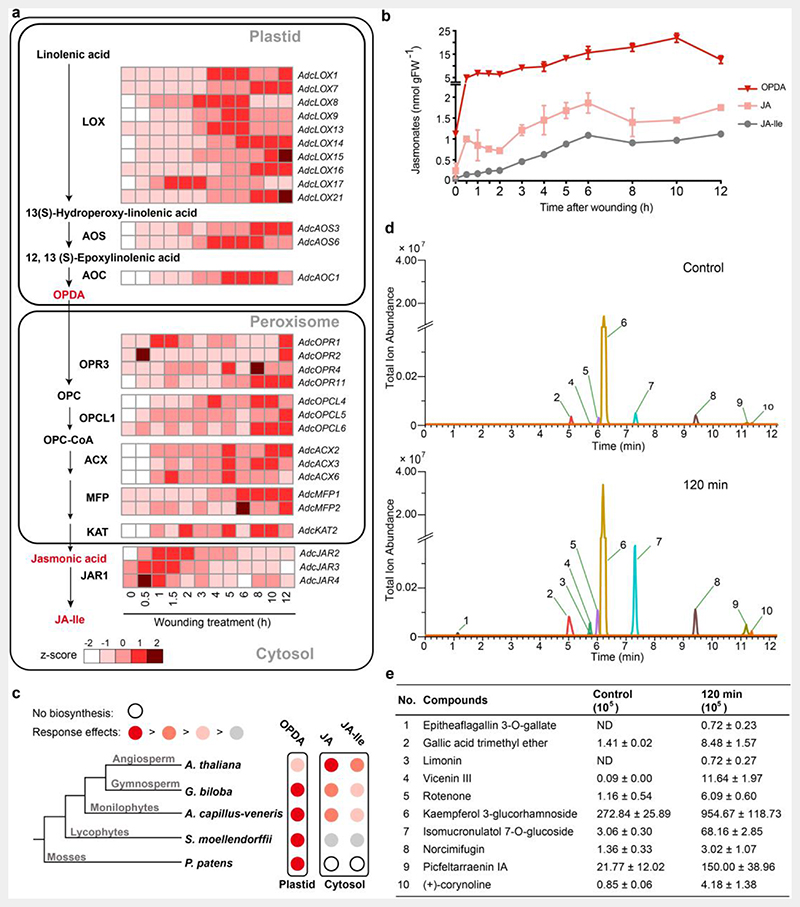

Fig. 4. Jasmonate biosynthesis pathway and defense-related metabolites in A. capillus-veneris.

a. Jasmonate (JA) biosynthesis pathway and expression profile of the representative genes. The fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM) were used to evaluate the expression of each gene, during seven developmental phases, and after a mechanical wounding treatment.

b. Time course of the mechanical wound response of JA (the precursor OPDA, jasmonic acid, and JA-Ile). Pinnae were wounded with a hemostat. Damaged pinnae were harvested at the indicated time points after wounding and analyzed for jasmonates accumulation by high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS); each data point represents the mean ± SD of five biological replicates.

c. Schematic diagram showing the relative increases in each jasmonate after mechanical wounding in species from five major clades of land plants. The relative response effects of OPDA, jasmonic acid, and JA-Ile are compared in each species, with data reported in references for P. patens, S. moellendorffii, and Arabidopsis and data generated in this study (A. capillus-veneris and G. biloba). The major jasmonate molecule exhibiting a rapid increase and considerable accumulation is indicated in dark red. The second effective wound response jasmonate with a rate and accumulation comparable to those of the major jasmonate molecule is indicated in red. The jasmonate with wound response biosynthesis is weaker and slower than that of the major jasmonte is indicated in pink. The jasmonate with wound response biosynthesis is far weaker (smaller than 100 times) than that of the major JA is indicated in gray. In P. patens, the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid and JA-Ile is absent, as indicated by an open circle.

d. Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) showed coronatine-induced significant changes of metabolites with defense function in ferns. Metabolites of fern leaves treated with coronatine for 2 h were measured using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole/mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QE/MS), with leaves without treatment as a control. Metabolites with well-known insect resistance functions that were significantly enriched in the 2-h samples were extracted and labeled; metabolites labeled 1-10 are named in (e).

e. Abundance of significantly enriched defense-related compounds labeled 1-10 in (d). The values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 5 independent biological samples). ND, not detected. Detailed data are provided in Extended Data Table 6.

Previous studies have shown that, in bryophytes, 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA) acts as a bioactive signaling molecule, where jasmonic acid and JA-Ile cannot be detected37,38. In the angiosperm Arabidopsis, JA-Ile is the biologically active form, indicating the diversification of wound-inducible JA accumulation39,40. In fern A. filiculoides, genes that are potentially associated with producing and perceiving jasmonate were detected. However, the active form of jasmonate was still largely unknown41. Here, we found that the level of OPDA increased quickly, within 0.5 h after wounding, and then increased steadily within a 10 h test period (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 13-14). Meanwhile, the continuous accumulation of JA and JA-Ile was also detected, which is consistent with the observation that enzymes responsible for JA-Ile biosynthesis from OPDA. These results showed that ferns possess the complete jasmonate biosynthesis pathway, especially the pathway from OPDA to JA-Ile. Moreover, exogenous applications of coronatine, a structural mimic of endogenous active JA-Ile, was able to trigger the biosynthesis of hundreds of secondary metabolites in pinnae (Extended Data Table 6). The remarkable activation effect of coronatine on cell metabolism in ferns is similar to that in angiosperms42, which suggested that JA-Ile could function as an active jasmonate in ferns.

Furthermore, we found that the relative abundance of OPDA and JA-Ile was distinctly different between the lycophytes and ferns. In the lycophyte S. moellendorffii, the content of OPDA was about 40,000-fold higher than the peak level of JA-Ile and the JA-Ile biosynthesis was relatively slow (beginning at 3 h after wounding)43, showing that OPDA is the main JA active molecule. However, in A. capillus-veneris, the relative abundance of OPDA/JA-Ile ratio was 58.82, under the wounding treatment, establishing that JA-Ile biosynthesis in ferns has been enhanced largely compared to lycophytes. Furthermore, in the angiosperm Arabidopsis39,40 and the gymnosperm G. biloba (Supplementary Fig. 8), OPDA and JA-Ile accumulated at a comparable level in wounded plant tissues with OPDA/JA-Ile value 4.5 and 1.7, respectively. The higher OPDA/JA-Ile value of ferns showed that the JA-Ile biosynthesis from OPDA in ferns is weaker than that in the seed plants (Fig. 4c).

The levels of a series of metabolites (phenylpropanoids, terpenes, and alkaloids), known for their defense functions in seed plants, were also found to increase under the coronatine treatment (Fig. 4d-e and Extended Data Table 6). Particularly, limonin, previously characterized as an insect toxin44,45, was induced. A number of chemicals acutely toxic to insects, such as rotenone46 and picfeltarraenin IA45, also underwent an increase in their levels. Many irritant pathogen-resistance compounds, such as picfeltarraenin IA and spiculisporic acid45, were also present at relatively high levels after treatment. These findings suggested that JA-mediated rapid accumulation of intensely toxic secondary metabolites could provide the basis for the high biotic resistance in ferns.

Gene family expansion within euphyllophytes except for the fern clade

The A. capillus-veneris genome provided an opportunity to compare the diversification of the gene content (gain, loss, expansion, and contraction), within ferns and seed plants, to infer the ancestral genomic toolkit underlying features shared by all euphyllophytes. For comparative genomic analysis, we collected genomes from 18 representative species across land plants and algae (See Extended Data Table 7). Comparatively more gene families experienced gain or expansion events at the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of euphyllophytes and seed plants (Fig. 5, Extended Data Table 8 and 9), whereas the trend of orthogroups at the node along ferns lineage was predominantly a decrease in gene content (loss and contraction) (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Table 10). A total of 1,035 orthogroups were lost entirely in ferns MRCA, and the aquatic fern MRCA exhibited a secondary loss of 679 orthogroups and 8.5 times more orthogroups with a contraction compared to ferns MRCA (Extended Data Table 10). Although this was partly due to the use of a lower number of fern species and a higher proportion of aquatic fern species which have fewer gene models, the simplification and degeneration of aquatic ferns traits, such as the degenerated root, were consistent with their reduction in orthogroups.

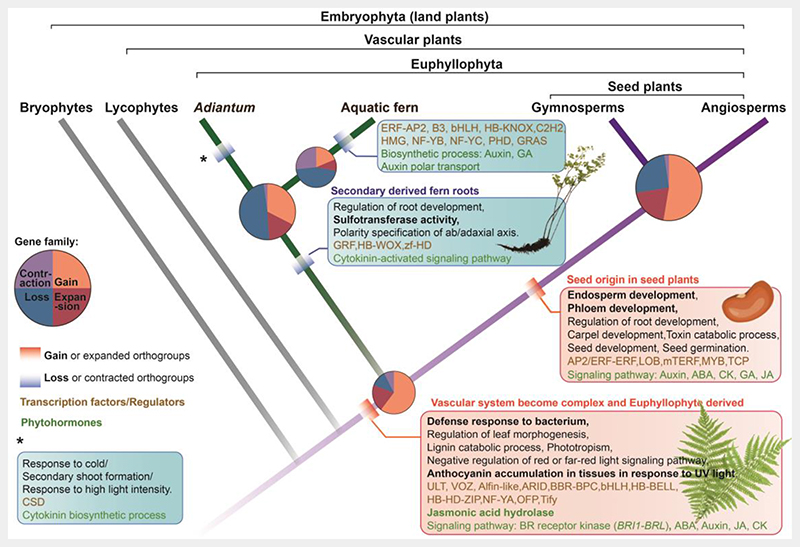

Fig. 5. Gene family dynamics enabling adaptive features in euphyllophytes.

Cladogram symbolizing land plant evolution shows gain (red boxes) and loss (blue boxes) of features in the euphyllophyte clade; phytohormone-related terms (in green) and transcription factors and regulators (in brown) are indicated. Pie plot at key nodes of land plants showing the proportion of gene family dynamics (gain and loss, expansion and contraction). Gene families that were gained or lost were in bold. The area size of the pie indicates the gene family numbers.

Numerous genes first appeared (716) and subsequently expanded (242) in the ancestral euphyllophyte (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Table 8). To obtain insights into their gene functions, we performed GO analyses and found that terms related to vascular system development, including leaf and stem vascular regulator BRI1-BRL (BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE1, BRI1; BRAS-SINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1-LIKE RECEPTOR KINASE, BRL) genes, and the phloem and xylem histogenesis regulator, ERF1 (ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1), were overrepresented (Extended Data Table 8). Furthermore, secondary cell wall biogenesis, which is involved in xylem vessel cell formation, such as the cell wall modification gene PME2/38 and secondary cell wall biogenesis gene SND1, were also overrepresented. The expansion of orthogroups related to vascular development might be key components underlying the origin of euphyll leaves, which are featured by a complex vascular venation system.

Insights into evolution of the leaf vascular system

Compared with lycophytes that bear simple single-midvein leaves and a continuous vascular systems, leaf venation in ferns and seed plants is complex, and their vascular system is interrupted by parenchymal tissues, known as leaf gaps. Given that the BRI1-BRL gene family, the key vascular regulator, has been noted to have emerged in the euphyllophytes in our comparative genomic analysis (Fig. 5), phylogenetic analysis was further employed to identify orthologs in land plants, especially in non-euphyllophyte species. Since BRI1-BRL gene family has been well-studied in seed plants47–50, we thus added genome assemblies of bryophyte and lycophyte species into the phylogenetic analysis datasets (Extended Data Table 7). Due to the high similarity between the BRI1-BRL and EMS1 lineages51, which makes it difficult to distinguish them from each other, we further identified a BRI1-BRL unique domain ID (island domain) absent in the EMS1 lineage (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 9), and its conserved amino acid sites (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 10). Finally, BRI1-BRL homologs were detected in all 12 euphyllophyte species, whereas only two Isoetes (lycophyte) homologs and one Anthoceros (bryophytes) homolog were recognized from all 12 non-euphyllophyte species (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating that the BRI1-BRL gene family was present at the MRCA of euphyllophyte.

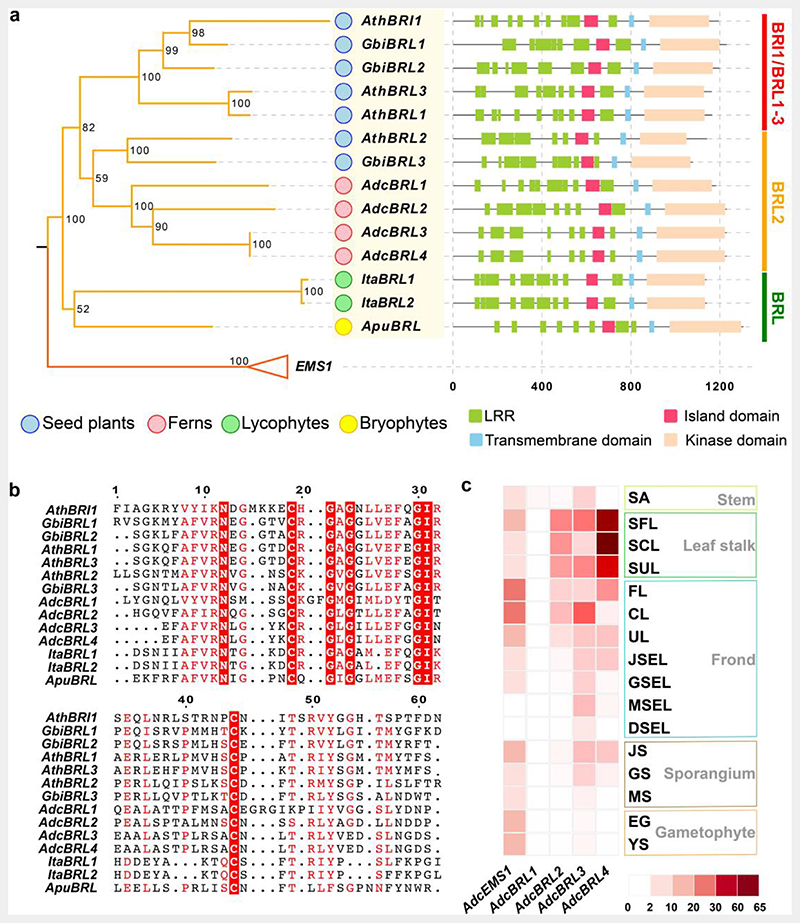

Fig. 6. BRI1-BRL gene family evolution.

a. Phylogenetic tree of the BRI1-BRL gene family in vascular plants. The EMS1 gene family, which is the sister group of BRI1-BRL, was employed as the outgroup. Bootstrap values are labeled along with clades. Boxes are used to show the domain configurations of each gene. Apu, Anthoceros punctatus; Ita, Isoetes taiwanensis; Adc, Adiantum capillus-veneris; Gbi, Ginkgo biloba; Ath, Arabidopsis thaliana. LRR, leucine-rich repeat domain.

b. The conserved sites for the BRI1-BRL gene family. The conserved sites were indicated with red boxes.

c. Expression of A. capillus-veneris BRI1-BRL and EMS1 genes in samples from various organs and tissues, including stem (SA, shoot apex), leaf stalk (SFL, stalk of the fist leaf; SCL, stalk of circinate leaf; SUL, stalk of unfurled leaf), frond (FL, first leaf; CL, circinate leaf; UL, unfurled leaf; JSEL, juvenile-sporangium-excised leaf; GSEL, green-sporangium-excised leaf; MSEL, mature-sporangium-excised leaf; DSEL, dehiscent-sporangium-excised leaf), sporangium (JS, juvenile sporangium; GS, green sporangium; MS, mature sporangium) and gametophyte (EG, embryo gametophyte; YS, young sporophyte).

The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny tree of BRI1-BRL genes, from the three euphyllophyte species, supported with > 80% bootstrap value that the BRI1-BRL family arose from two major splits: the first before the divergence of ferns and seed plants, resulting in BRL2 (BRL2 clade) and the others, and the second before the divergence of seed plants, resulting in the diversification between the BRI1 and BRL1–3 genes (BRI1/BRL1-3 clade, Fig. 6a). All A. capillus-veneris BRI1-BRL orthologs belong to the BRL2 clade. Their seed plants ortholog Arabidopsis BRL2 were regarded as key regulators for leaf vascular development with high expression levels in leaf vascular bundles50. Three of the four A. capillus-veneris BRL2 clade orthologs also exhibited > 4-fold expression in the petiole (leaf stalk), which is vascular-rich, versus other A. capillus-veneris tissues, whereas AdcEMS1 expressed in almost all tissues investigated except for mature- and dehiscent-sporangium-excised leaf (Fig. 6c), suggesting the functional diversification between BRL1-BRL and EMS1, and the BRL2 clade is functionally conserved for vascular development regulation in euphyllophytes. This might underlie the complex vascular system formation leading to the origin of the euphyll.

Conclusions

The phylogenetic position and homosporous nature make the A. capillus-veneris genome a valuable reference that facilitates interpretation of key evolutionary events, not only in ferns, including homosporangium development and outstanding pathogen-resistance, but also in euphyllophytes. A. capillus-veneris has enabled the inference of the genetic basis for the homosporangium, thereby uncovering the similarity of the homosporangium with pollen exine and the seed storage pathway. As the high-quality genome of a model species representing the major homosporangium ferns, A. capillus-veneris provides a useful model for studies on the origin of extant ferns, as well as a series of trait emergence associated with gene families evolution, eventually leading to the euphyll origin.

Methods

Plant materials

A. capillus-veneris plants were provided by Guangyuan Rao’s lab at Peking University. A previously reported method was implemented to generate a strictly self-fertilized A. capillus-veneris diploid plant, via intragametophytic selfing52. In brief, spores were sterilized using 4% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min twice, washed 3 times with sterilized water, and then suspended in liquid Knop’s medium. The spore suspension was then spread on Knop’s solid medium in Petri dishes that were then sealed and placed in the dark for 3 d; they were then placed under red light (145 μmol m-2 s-1 irradiance, 24 h/d, 25°C). After 7 d, Petri dishes were placed under white light (36 μmol m-2 s-1 irradiance, 16 h light/8 h dark, 25°C). Before sexual maturity, the prothallus was isolated, via sterile needles under a dissecting microscope, and transferred to a new Petri dish, which was then placed back under white light. Until both antheridia and archegonia were distinguishable, each prothallus was sprinkled with sterile water to facilitate fertilization. After 10 to 20 d, a bulge was visible on the adaxial surface, which was the developing embryo (new generation sporophyte) in the archegonium. The young sporophyte was then moved to soil and cultivated at 25°C with 12 h light/12 h dark regime. Genomic DNA was prepared from young fronds of this A. capillus-veneris sporophyte. The heterozygosity was estimated based on k-mer via the program GenomeScope253 (v1.0.0). The heterozygosity of this A. capillus-veneris sporophyte was 0.25%, indicating a homozygous diploid plant, which was used as sample tissue for the following genome sequencing and RNA-seq.

Genome estimation and assembly

Genomic DNA was extracted and purified from the pinnae of A. capillus-veneris using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method54. A combined strategy with whole genome shotgun (WGS), PacBio, Hi-C, and BioNano was performed for genome sequencing. Quality control of the filtered Illumina reads was performed using fastp55 with default parameters. Then, Jellyfish software56 was employed to infer the genome size from the k-mer distribution, and the inferred genome size was 4.95 Gb when k-mer = 35 bp.

A total of 579.3 Gb (~115-fold coverage) of PacBio single-molecule long reads (N50 = 19 Kb) were produced for assembly (Supplementary Table 1), using the Canu program57, which generated 4.81 Gb sequences with 7,180 contigs (N50 = 1.29 Mb). The genome assembler HERA58 was then used to improve the continuity of Canu-assembled contigs (N50 = 16.22 Mb). Next, the BioNano data was assembled with RefAligner and Assembler tools in the BioNano Solve program (https://bionanogenomics.com/) to generate the genome map (N50 = 32.86 Mb, Supplementary Table 2 and 5). The HERA-generated contigs and the BioNano genome map were used to construct the scaffolds by hybridScaffold.pl script in the BioNano Solve program. During this step, the initial scaffold N50 was up to 99.90 Mb (Supplementary Table 5). And then, 68 × Illumina sequence data were used for polishing (Supplementary Table 3). The adaptor sequences and other possible contaminant sequences, derived from insects, bacteria, fungi, and humans, as well as chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes, were removed from the assembled scaffolds. Finally, ~457 Gb Illumina clean 150-bp pair-end reads generated from five Hi-C libraries were aligned to the contig assembly using Juicer59 (Supplementary Table 4). Contigs were further clustered into 30 pseudochromosomes with 3D-DNA60 (github.com/theaidenlab/3D-DNA), which was consistent with the reported chromosome number of A. capillus-veneris61. Chromosome boundunaries and any misjoins were manually curated with Juicebox62. Finally the chromosome-level scaffold N50 of 159.32 Mb was reached. The assembly statistics are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

To check the chimeric and indel contigs of genome assembly, the comparison of BioNano maps and the current assembly was performed. The A. capillus-veneris reference genome assembly was first digested with DLE1 enzyme, in silico, to generate a contiguous BioNano optical map for each chromosome, using the fa2cmap_multi_color.pl script in the BioNano Solve program. The BioNano optical map was aligned against the generated CMAP file of reference genome, using the RefAligner tool from runCharacterize.py script from BioNano Solve. Only 2, 6 chimeric, and indel contigs (> 1 Kb) were identified. And no indel contigs that are larger than 5 Kb were identified (Supplementary Table 10).

Identification of repetitive sequences

For repetitive elements identification, we first employed the repeat-finding program RepeatModeler (version 1.0.8 in http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler.html) for de novo construction of a repetitive elements library and generated 23,414 repetitive sequences. Then, this RepeatModeler repeat library was further merged with two additional repeats databases, TIGR (http://plantrepeats.plantbiology.msu.edu) and Repbase (version 19.05)63 to generate repeat datasets for repetitive elements prediction in A. capillus-veneris. Finally, we used RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org) to identify the repetitive elements. A repetitive-elements-masked file, in which repeats were removed from the genome, was also generated for the following gene prediction analyses.

To investigate LTR-RTs evolution, we first identified LTR-RTs by using a combined program of LTR_FINDER64 and LTRharvest65. LTR_retriever66 was then employed to filter out false LTR-RTs using three types of structural and sequence features: target site duplications, terminal motifs, and LTR-RT Pfam domains. To calculate the nucleotide distance (D) to study LTR-RTs history, both ends of these full-length LTR-RTs were aligned using MUSCLE67, and the D was estimated, via the distmat in the EMBOSS package (version 6.6.0)68, based on the Kimura two-parameter (K2p) criterion69.

Protein-coding gene prediction and function annotation

Three methods, namely, homology-based prediction, transcriptome-based prediction, and ab initio gene prediction, were used to predict protein-coding gene models. To search for homologous genes, the protein sequences from all ferns and lycophytes transcriptomes in the OneKP project17 were retrieved and aligned to the A. capillus-veneris genome, using GeneWise70. For transcriptome-based prediction, nineteen transcriptomes covering the entire life cycle of A. capillus-veneris were generated in this study (Supplementary Table 8). RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy protocol and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 with a 300 bp insert size. For transcriptome-based prediction, the HISAT271 and StringTie72 programs were used for transcript assembly73. The program PASA (http://pasapipeline.github.io) was used to align spliced transcripts and annotate candidate genes. Ab initio prediction was performed with AUGUSTUS74, GlimmerHMM75, and SNAP76. Finally, nonredundant gene models were obtained with EVidenceModeler (version 1.1.0)77 to integrate the gene models developed by different datasets.

Predicted genes were functionally annotated based on the Swiss-Prot database (http://www.gpmaw.com/html/swiss-prot.html)78, NCBI nonredundant (NR) protein database (version date: 20150617), TAIR10 (version date: 20101214)79 by BLASTP (version 2.5.0+)16 with an expectation value (E-value) of 1 × 10-5 and InterProScan database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/)80. Then, GO terms were assigned using Blast2GO81. Protein sequences were also mapped to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database82 using the KEGG automatic annotation server (KAAS, https://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/)83.

To validate the assembly quality, RNA-seq reads from nineteen tissues (Supplementary Table 8), together with publicly available EST sequences from the NCBI database (downloaded from http://togodb.dbcls.jp/library), were mapped to the A. capillus-veneris genome using HISAT271 and BLAT84 with default parameters, respectively. The BLAT results were filtered with an identity and coverage cutoff of 0.9.

Identification of noncoding RNAs

We used tRNAscan-SE (version 2.0rc2)85, with default parameters, to search for tRNAs in the A. capillus-veneris genome. A total of 1,624 tRNAs were found. Moreover, the Rfam14.0 database86, including 3,445 noncoding RNA families, was used to annotate additional noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), including miRNAs, snRNAs, and tRNAs, using INFERNAL (version 1.1.2)87 program.

We predicted rRNA (5S, 5.8S, 28S, 18S) by using HMM searching based rRNA predicator Barrnap (version 0.9, https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap#barrnap), with default parameters. We finally identified 145 5S, 75 5.8S, 155 28S, and 165 18S sequences and their locations within the genome assembly of A. capillus-veneris.

Identification of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs)

In contrast to other ncRNAs, lncRNAs are defined as transcripts longer than 200 bp that do not encode proteins. These lncRNAs were searched, based on a previously reported method88, using the transcriptome datasets shown in Supplementary Table 8.

The RNA-seq reads from the samples were aligned to the genome of A. capillus-veneris using HISAT2 (version 2.1.0)71, and unique aligned reads were used for further analysis. Transcripts representing all isoforms were identified using StringTie (version 1.3.5)72. Transcripts with lengths shorter than 200 bp and open reading frames (ORFs) longer than 100 amino acids likely encoding proteins were filtered. Subsequently, three tests were used to filter lncRNAs. Firstly, all transcripts were aligned to the Swiss-Prot78 database using BLASTX (version 2.5.0+)16 with the E-value threshold at 0.001. Secondly, the ORFs and protein sequences were obtained using the transeq program in the EMBOSS package68. All predicted proteins were aligned to the Pfam database (Pfam-A)89 using HMMER with a model E-value threshold of 0.001 and a domain E-value threshold of 0.001. Third, transcripts were predicted by the Coding Potential Calculator (CPC)90 with default parameters. All sequences aligned to the above three databases were considered protein-coding genes and removed. As a result, 7,058 candidate lncRNAs were obtained. To further identify high-confidence lncRNAs, the obtained candidate lncRNAs were aligned with the ncRNA database86, by BLASTn16 with an identity threshold of 90%. Finally, we predicted 6,541 high-confidence lncRNAs.

Recent whole genome duplication analysis

To detect paralogues located in collinear blocks, all-against-all BLASTP (v.2.6.0+)16 were performed with an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10-5. The top ten alignments per gene were selected with the package MCScanX15 with default parameters to detect syntenic paralogue pairs located in collinear blocks. Only 96 syntenic paralogues in 7 collinear gene blocks were identified. The dot_plotter.jar in the package MCScanX15 was employed for drawing the dot-plot to show the relationship of collinear blocks.

Construction of KS-based age distributions

KS-based age distributions for whole paranome and anchor pairs of A. capillus-veneris were constructed by wgd91 within ksrates19. First, the paranome was built by identifying gene families using the mclblastline pipeline (v.10-201)92 with an inflation factor of 2.0 after performing all-against-all BLASTP (v.2.6.0+)16 search with an E-value cut-off of 1 × 10-10. Each gene family was aligned using MUSCLE (v.3.8.31)67 and CODEML in the PAML package (v.4.9j)93 was used to estimate KS for all pairwise comparisons within a gene family. As a gene family of n members produces n (n - 1) / 2 pairwise KS estimates for n - 1 retained duplication event, wgd91 corrected for the redundancy of KS values by first inferring a phylogenetic tree for each family using Fasttree94 with the default settings. Then, for each duplication node in the resulting phylogenetic tree, all m KS estimates for a duplication between the two child clades were added to the KS distribution with a weight of 1/m, so that the sum of the weights of all KS estimates for a single duplication event was 1. Anchor pairs were detected using i-ADHoRe (v.3.0.01)95 under default parameters within ksrates19.

To identify peaks in the KS distributions that could be signatures of WGD events, an exponential-lognormal mixture model (ELMM) was fit into the whole paranome of A. capillus-veneris, in which an exponential component was used for the L-shaped small-scale gene duplications96 and one to five lognormal components were used for potential WGD peaks. Numbers of the lognormal components were further evaluated according to the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) scores and the best ELMM model was plotted. Anchor pairs clustering was achieved by the lognormal mixture modeling of median KS values of collinear segment pairs, based on the assumption that collinear segment pairs originated from the same WGD event are likely to share a similar KS age and to fall into the same KS cluster. The original KS distribution of anchor pairs was then plotted based on the cluster result.

Correcting differences in synonymous substitution rates

The varying synonymous substitution rates across species were corrected under the method described in ksrates19. Briefly, the KS-based orthologous age distributions were first constructed by wgd91 within ksrates19, which identified one-to-one orthologs followed by KS estimation using the CODEML (v.4.9j)93. Next, two species trios, i.e., A. capillus-veneris, A. filiculoides and outgroup L. japonicum, and A. capillus-veneris, S. cucullata and L. japonicum, were adopted for rescaling the lineage-specific branch length contribution of A. filiculoides and S. cucullata into the adjusted branch length in the same KS timescale as A. capillus-veneris. Eventually, the adjusted divergence ortholog KS peaks were directly comparable to the WGD peak of A. capillus-veneris.

Comparative genomic analysis

For comparative genomic analysis, we selected taxa to represent all of the major Streptophyta lineages (land plants, Zygnematophyceae algae, and green algae) for which genome sequence data are available, including two bryophytes (Marchantia polymorpha97, Physcomitrella patens98), one lycophyte (Selaginella moellendorffii99), three ferns (S. cucullata8, A. filiculoides8, A. capillus-veneris), three gymnosperms (Ginkgo biloba100, Pinus taeda101, Picea abies102), six angiosperms (Amborella trichopoda103, Arabidopsis thaliana104, Cucumis sativus105, Vitis vinifera106, Oryza sativa ssp. japonica107, Zea mays108), as well as two Zygnematophyceae algae (Spirogloea muscicola109 and Mesotaenium endlicherianum109), which was regarded as the closest sister group to land plants, and one green alga (Klebsormidium nitens110). The details for genome resources are provided in Extended Data Table 7. The orthogroups among these species were built by OrthoFinder111 (version 2.4.0) with default parameters. All alternative splicing and redundant gene entries were removed, and the longest isoform for each gene was retained. A total of 34,392 orthogroups were identified and orthogroups with genes present in at least one land plant and one algal species were finally retained for the following analysis.

We used sixty-three low-copy gene families (one or two gene copies of each orthogroup for each genome), shared by the above eighteen species, to construct a phylogenetic species tree. MAFFT (version 7.471)112 multiple sequence alignment tool was used to align these low-copy genes. The gap regions in the alignment were trimmed with trimAL (version 1.4.rev15)113. Poor quality alignments were filtered out by Gblocks (version 0.91b)114, and only conserved regions were retained. The gap-trimmed orthologous sequences were concatenated into one supersequence with 6,853 amino acid sites for species tree construction. A maximum-likelihood phylogenic species tree was estimated by IQ-TREE (version 2.0.3)115 with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

We used the CAFE 3 (version 4.2.1) software tool116 to count gene numbers at the nodes in the species tree and infer gene families that had undergone expansions or contractions. Following the instructions given in the CAFE 3 manual, we first transformed the above species tree into an ultrametric tree via r8s (version 1.81)117. The divergence times between Arabidopsis and V. vinifera (117 Mya), O. sativa and Z. mays (48 Mya), G. biloba and P. taeda (271~310 Mya), and M. polymorpha and P. patens (395~541 Mya) were provided to r8s for scaling branch lengths into time units. All the divergence times were estimated by TimeTree (http://timetree.org). The birth/death parameter (λ) was inferred for the entire tree. Families were retained if estimated to have undergone a significant expansion or contraction at the corresponding most recent common ancestor, with a P-value < 0.01.

We carried out the DOLLOP program from the PHYLIP package (version 3.696) (https://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html) to determine gene family gain and loss evolutions. DOLLOP is based on the Dollo parsimony principle, which assumes that genes arise exactly once on the evolutionary tree and can be lost independently in different evolutionary lineages. For Dollo inference, the supermatrix tree and a binary matrix derived from the matrix used for CAFE analysis were provided. The number of orthogroup gain and loss, in each branch and node, was further extracted using in-house Perl scripts. Finally, GO enrichment analyses were performed against the orthogroups that gained or lost, expanded or contracted at each key evolutionary node within euphyllophytes (see Extended Data Table 8-10 for details).

Transcription factor identification

To identify and compare transcription factors among land plants, firstly, we used the iTAK database (http://itak.feilab.net/cgi-bin/itak/index.cgi) as a transcription factor reference and blasted the annotated genes of eighteen representative land plant species (the same as comparative genomic analysis) against the iTAK database. We then assigned these genes to specific transcription factor families, using the prediction tool iTAK118.

Analysis of homosporangium transcriptome data

Total twenty samples (Extended Data Table 1) were collected to generate the RNA-seq data for transcriptome analyses, including fist leaf (FL), stalk of fist leaf (SFL), circinate leaf (CL), stalk of the circinate leaf (SCL), unfurled leaf (UL), stalk of the unfurled leaf (SUL), juvenile sporangium leaf (JSL), juvenile sporangium (JS), juvenile-sporangium-excised leaf (JSEL), green sporangium leaf (GSL), green sporangium (GS), green-sporangium-excised leaf (GSEL), mature sporangium leaf (MSL), mature sporangium (MS), mature-sporangium-excised leaf (MSEL), dehiscent sporangium leaf (DSL), dehiscent-sporangium-excised leaf (DSEL), stem apical (SA), embryo gametophyte (EG), and young sporophyte (YS) (Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6 for their PCA analysis). Every sample had three biological replicates, except for MS and YS which had only two biological replicates. A total of 464.5 Gb RNA-seq data were acquired. The reads were mapped to the assembled A. capillus-veneris genome using HISAT2 (version 2.1.0)71 with default parameters. The average overall mapping rate reached 95.79%, and the paired mapping rate was 85.37%. The corresponding fragments per kilobase pair of transcripts per million mapped reads (FPKM) values of genes were calculated using the StringTie (version 1.3.5)72.

To examine gene expression in the homosporangium, at three developmental phases (juvenile, green, and mature), the differential expression level between sporangium and sporangium-excised leaf were calculated by using the edgeR package (version 3.20.9)119. Genes with an expression level in particular sporangium (i.e. JS) two-fold higher (logFC > 1) and significantly different (q-value < 0.05) relative to sporangium-excised leaf at the same phase (i.e. JSEL), were assigned as tissue-enriched genes.

GO and KEGG82 enrichment analyses of tissue-enriched genes were performed to elucidate the biological processes and pathways characterized in each developmental stage. The reference background datasets were the GO terms and KEGG orthology (KO) of all genes, and a P-value of 0.01 was used as a cutoff.

Gene expression values for all tissue-enriched genes were used in WGCNA (version 1.68)120. A total of eight modules were obtained using a step-by-step network construction method (Extended Data Table 3). The module eigengenes representing the first principal component were used to describe each module. The eigengenes were subsequently used to estimate the correlations between tissue specificity and module eigengenes. A tissue specificity array was constructed, using one and zero to represent presence and absence, respectively, in each tissue.

Genes annotated as TFs were extracted based on the functional annotations, and then the TFs with a Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of 0.7 or higher were further analyzed as candidate TFs that were highly correlated with homosporangium development stages. Using the above-described method, different gene sets strongly correlated with candidate TFs were obtained. TFs in the M3 module remained 0 after filtering, so the coexpression network was only analyzed in the M6 and M8 modules. Genes associated with enzymes of sporopollenin and fatty acids were selected to mark the developmental stages of homosporangium. The networks were visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.7.1)121.

AdcLEC1 coexpression network

AdcLEC1 was enclosed in the M6 module of WGCNA. The correlation coefficient matrix between AdcLEC1 and other genes in the M6 module was estimated by calculating the PCC using the cov function in the R. The genes were further confirmed with annotation information before comparison to angiosperm seed development genes. The AdcLEC1 co-expression networks were visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.7.1)121.

For comparative co-expression network analysis, we detected orthologs in both Arabidopsis and A. capillus-veneris LEC1 co-expression networks. The Arabidopsis LEC1 co-expression genes were obtained from the study by Pelletier et. al29. Reciprocal bidirectional BLAST searches were run for Arabidopsis LEC1 co-expression gene sets to A. capillus-veneris coding-genes. The first returned hit, given by reciprocal BLAST, was then compared against Pfam databases for conserved domains detection. Best hit gene pairs with the same conserved domains were referred to as orthologous gene pairs between Arabidopsis and A. capillus-veneris. It was subsequently determined whether, or not, the A.capillus-veneris orthologous genes were included in the AdcLEC1 co-expression gene sets (M6 module).

Wounding treatments

Green sporangium pinnae of A. capillus-veneris plants were crushed across the apical lamina using a hemostat, which effectively wounded approx. 30% of the pinnae area. Plants were incubated for a time course (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, and 12 h), after which the pinnae were harvested (with a clean sterilized razor blade) and immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at -80°C and later used for RNA-seq (see Extended Data Table 1 for details) and metabolic analyses.

Expression profile of JA biosynthesis genes

The JA biosynthesis genes of A. capillus-veneris were identified via BLASTP Arabidopsis JA genes based on the Arabidopsis hormone database, version 2.0 (http://ahd.cbi.pku.edu.cn)122 against A. capillus-veneris peptide sequences. The domains of the best hits were further identified, using HMM tools. The A. capillus-veneris genes with the same conserved domain as their Arabidopsis homologs were regarded as A. capillus-veneris JA biosynthesis genes (Extended Data Table 5).

The RNA-seq data from wounding treatment samples were aligned to the A. capillus-veneris genome by HISAT271. Gene expression levels were represented by FPKM values based on the above-described methods. The expression values were further transformed by the function log2 (FPKM + 1) for the heatmap plot. Expression levels of JA biosynthesis genes in A. capillus-veneris in leaves at specific time intervals after wounding treatment were extracted using a Perl script (shown in Extended Data Table 5).

Jasmonate content determination

The sample metabolites were extracted using a modified Wolfender method123. First, the samples stored in a -80°C refrigerator were dried in a freeze dryer and then ground into powder in liquid nitrogen. Then, 100 mg of powder was weighed accurately and transferred into a 2 mL centrifuge tube. To correct loss that occurred during sample preparation, 10 μL of stable isotope internal standard (10 μg/mL d5-JA, Cayman Chemical Co.) was added to each sample before extraction. Then, 1.5 mL of extraction buffer (isopropanol: formic acid at 99.5 : 0.5, v/v) was added, with vortexing for sample resuspension, followed by 2 min of vortexing, three times, in a mixer mill at 900 rpm. After a 15-minute centrifugation at 14,000 × g, the supernatants were dried in a LABCONCO CentriVap vacuum centrifugal concentrator and then resuspended in 1 mL of methanol solvent (85 : 15, v/v). A Waters Sep-Pak C18 SPE column was further used for more readily detected and more accurately quantitated detection, and then a total of 2 mL of SPE column eluent was collected per sample. The eluent was dried in a LABCONCO CentriVap vacuum centrifugal concentrator and resuspended in 100 μL of methanol solvent (60 : 40, v/v) for LC-MS analysis.

For the determination of jasmonates, the prepared samples were analyzed with an AB Sciex 4500 QTRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX). We achieved separation of all targeted compounds on an ACQUITY UPLC™ BEH C18 column (Waters) (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) based on an ACQUITY UPLC I-Class (Waters). The injection volume was set at 10 μL, and the flow rate was set at 200 μL/min. Solvents for the mobile phase were 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution was 0-10 min, linear gradient 50%-100% A, and then the column was washed with 100% B and 100% A before the next injection. The autosampler was set at 10°C to protect samples during analysis.

We acquired mass spectrometry in negative electrospray ionization mode separately, with [M - H] of target analytes selected as the precursor ion. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was applied for quantification using the mass transitions (precursor ions/product ions, Supplementary Table 13). General electrospray ionization (ESI) conditions were as follows: the temperature of the ESI ion source was 500°C, the curtain gas flow was 25 psi, collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) gas medium, and the ion spray voltage was (-) 4500 V for negative ionization mode, with ion gas 1 and 250 psi. Calibration standards were used to construct calibration curves of target analytes ranging with the same stable isotope internal standard added to the samples. Finally, we acquired mass spectra data and processed concentration calculations using AB SCIEX analyst 1.6.3 software (Applied Biosystems).

Coronatine treatments

Coronatine (Sigma C8115) was dissolved in DMSO, and then 0.1 and 1 μM working solutions were prepared with Murashige and Skoog (MS) liquid media, respectively. COR was applied to the adaxial surface of green sporangium pinnae, and the MS solution was used as a mock treatment. The treated samples were incubated over 0.5 and 2 h. Three replicate samples were taken for each treatment. At different incubation times following the treatment, pinnae tissues were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until further use for metabolomic analysis.

Metabolite detection

The samples stored at -80°C were fully ground in a SPEX Geno2010 (SPEX SamplePrep, LLC., USA) freeze dried. Then, a 50 mg aliquot of freeze-dried leaf powder was weighed and transferred into a 2 mL centrifuge tube at liquid nitrogen temperature. To extract hydrophilic metabolites from samples, one milliliter of extraction buffer (MeOH : H2O at 80 : 20, v/v, containing 0.1% formic acid) with internal standard (mixer of d5-coumarin, d3-DL-nicotine, d5-L-phenylalanine, d3-homovanillic acid, and nimodipine, with a final concentration of 1 μg/mL for each compound) was added, vortexed and subjected to a 1 h ultrasonic treatment in an ice bath for efficient resuspension of powder. Samples were then stored at 4°C, overnight. To more accurately compare metabolite differences, 1 ml of supernatant after a 15-minute centrifugation at 14,000 × g was pipetted and dried in a LABCONCO CentriVap vacuum centrifugal concentrator. One hundred microliters of reconstitution buffer (MeOH : H2O at 80 : 20, v/v) with internal standard (mixer of d5-L-tryptophan, d5-succinic acid, d3-nortriptyline, norethindrone, and diclofenac with a final concentration of 1 μg/mL for each compound) was used to resuspend each sample. Subsequently, a 14,000 × g centrifugation was applied twice to remove residuals before liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. A 10-μL aliquot of the supernatant for each sample was pipetted and mixed as QC samples, and a 1-μL aliquot was injected for LC-MS/MS analysis.

We performed a nontarget metabolomic analysis in a UPLC system coupled to a Q-Exactive orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, CA, USA) equipped with an HESI probe under both positive and negative (ESI+ and ESI-) modes. Extracts were separated by a Kinetex® Biphenyl column (Phenomenex) (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm).

The injection volume was 1 μL, and the flow rate was set at 250 μL/min. A 40-minute gradient was used, and solvents for the mobile phase were 2 mM ammonium acetate in water (A) and 100% acetonitrile (B). The column chamber and sample tray were held at 40°C and 10°C, respectively. The ESI source parameters were as follows: discharge current 6 μA, capillary temperature 320°C, heater temperature 250°C, sheath gas flow rate 35 Arb, auxiliary gas flow rate 10 Arb. Data with mass ranges of m/z 80-1200 and m/z 80-1200 were acquired in both positive ion mode and negative ion mode separately, with data-dependent MS/MS acquisition. The full scan and fragment spectra were collected with resolutions of 70,000 and 17,500, respectively.

We used TraceFinder analysis software (version 3.3, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) to analyze MS and MS/MS data acquired and achieved more than 10,000 metabolite profiles for each sample, with data processing parameter settings as follows: minimum peak width of 10 s, maximum peak width of 60 s, mzwid of 0.015, minfrac of 0.5, bw of 5, and signal/noise threshold of 6. Then, we further used TraceFinder software to annotate metabolites from mass spectra data based on commercial databases and in-house databases via a high-resolution MS-associated method. First, the candidate chemical formulae of metabolites were identified using accurate high-resolution m/z values and MS/MS fragmentation patterns with a mass accuracy of 2 ppm based on in-house databases. Finally, the annotated metabolites were checked and verified again by manually comparing both fragment patterns and isotope ratios. Peak detection, retention time correction, chromatogram alignment, and statistical evaluation were performed. The ion intensity was extracted and calculated by normalizing the single ion value against the total ion value of the entire chromatogram (i.e., EIC or extracted ion chromatography). After mean-centering and Pareto scaling, t-tests, ANOVA, and other statistical analyses for significantly changed metabolites were carried out based on the normalized data matrix. The resultant output contained a peak list with metabolite names, retention times, m/z values, t-test and ANOVA results, statistical significance values (P-values), and mean ion abundances with standard deviations (SDs, Extended Data Table 6). These results were used for subsequent multivariate statistical analysis, and the compounds were classified according to the KEGG compound database82 and PubChem database45.

BRI1-BRL gene family analysis

The methods of gene identification, protein domain profile construction, domain configuration identification, and phylogenetic analysis were as previously desecribed47. As BRI1-BRL genes in seed plants have been well studied, we focused on the analysis of homologs in non-seed plants. We thus collected as many fully sequenced genomes of non-seed plants as possible (Extended Data Table 7).

To identify BRI1-BRL homologs, model protein sequences in the above species were queried against Arabidopsis BRI1, BRL1-3, and their closest sister lineage EMS1, using BLASTP, with a threshold of E-value < 1e-5. The blast output peptide sequences were then interrogated to identify predicted conserved domains, using programs, including Pfam89, SMART124, Phobius125, Gene3D126, and TMHMM127 from InterProScan80. The amino acids neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was built using their kinase domain (KD) sequences. Genes that fell within the same well-supported clade with known BRI1-BRL and EMS1 genes were extracted for the following conserved domain filtering. Genes that lacked one of the conserved domains (BRI1-BRL: Leucine-rich repeat (LRR), ID, KD, transmembrane domain (TM); EMS1: LRR, KD, TM) were excluded. The conserved amino acids of island domains were exhibited by ENDscript server128. Finally, the LRR (PF13855, PF13516, PF12799, PF13516, PF00560, PR00019, SM00369), ID (G3DSA:3.30.1490.310), KD (PF00069, PF07714), and TM domains (TMhelix) of each BRI1-BRL and EMS1 (no ID domain) candidates were extracted. An amino acid maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of BRI1-BRL and EMS1 candidates was constructed by RAxML using conserved region stretching from LRR-ID (EMS1 doesn’t possess)-LRR-TM-KD. Conserved regions stretching from ID to KD (ID-LRR-TM-KD) were used for ML tree construction with parameter: JTT + G + I model and 100 bootstrap replicates (Fig. 6a).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Prof. Xianchun Zhang for providing helpful advice and suggestions, Prof. Guangyuan Rao for providing the homozygous A. capillus-veneris plant and DNA sequencing sample, Qing Li for guiding the genome annotation, Yaoyao Wu for providing the lncRNA determination pipeline, Tongming Yin and Hailin Liu for providing access to the Gingko biloba genome, Jiantao Zhao for converting the references to a uniform format, and Weihua Wang and Lina Xu at Tsinghua University for the assistance of phytohormone and metabolites detection. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0906200), the Elite Young Scientists Program of CAAS, and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program. The work was also supported by Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (ZDSYS20200811142605017). Z.L. is funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Special Research Fund of Ghent University (BOFPDO2018001701). Y.V.d.P. acknowledges funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 833522) and from Ghent University (Methusalem funding, BOF.MET.2021.0005.01).

Footnotes

Author contributions

S.H., S.B., Y.F. and J.Y. conceived the study. Y.F. and J.Y. designed and managed the major scientific objectives. S.H., Y.F., W.J.L. and J.Y. coordinated the project. Y.F., W.J., Yaning Yuan, L.W., and X.Q. managed the plant materials. Q.Z. and P.S. assembled the genome and estimated the genome size. Y.F., Q.L., X.L., X.Q., Q.Z., P.S., L.W. and Z.Z. annotated the genomes. H.C., Z.L., Y.V.d.P performed the WGD calling. Y.F., Q.L., X.L. identified the repetitive elements, noncoding RNAs and lncRNAs. Y.F., Q.L., Yuehong Yan, R.Z., J.Z. and S.C. clustered the gene families and conducted the related phylogenetic analysis. Y.F. and Q.L. constructed the coexpression network of AdcLEC1. Y.F., Q.L., X.Q. and X.L. carried out the RNA-seq analysis on homosporous development and jasmonate biosynthesis genes. J.Y. and R.D. performed the jasmonate biosynthesis and signaling analyses. R.D., Y.F., W.J. and Yaning Yuan contributed to hormone and metabolome sample preparation. R.D. carried out metabolome detection and characterized the function of coronatine-inducible metabolites. Y.F. and J.Y. led the manuscript preparation, together with S.H., W.J.L., Y.V.d.P., Q.L., R.D., Z.L., X.Q., X.L., X.Z. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The A. capillus-veneris genome assembly, genome annotation, and all of the raw sequencing data have been deposited at NCBI, under the BioProject accession number PRJNA593372 (genome assembly and annotation) and PRJNA593361 (transcriptome raw sequence data). The CDS and peptide files are available from https://figshare.com/s/47be9fe90124b22d3c0e.

References

- 1.Sessa EB, Der JP. In: Advances in Botanical Research. Rsening SA, editor. Academic Press; San Diego: 2016. pp. 215–254. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group. A community-derived classification for extant lycophytes and ferns. J Syst Evol. 2016;54:563–603. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pryer KM, et al. Horsetails and ferns are a monophyletic group and the closest living relatives to seed plants. Nature. 2001;409:618–622. doi: 10.1038/35054555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang C, Bowman JL, Meyerowitz EM. Field guide to plant model systems. Cell. 2016;167:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf PG, et al. An exploration into fern genome space. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:2533–2544. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szövényi P, Gunadi A, Li FW. Charting the genomic landscape of seed-free plants. Nat Plants. 2021;7:554–565. doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-00888-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark J, et al. Genome evolution of ferns: evidence for relative stasis of genome size across the fern phylogeny. New Phytol. 2016;210:1072–1082. doi: 10.1111/nph.13833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li FW, et al. Fern genomes elucidate land plant evolution and cyanobacterial symbioses. Nat Plants. 2018;4:460–472. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang X, et al. The flying spider-monkey tree fern genome provides insights into fern evolution and arborescence. Nat Plants. 2022;8:500–512. doi: 10.1038/s41477-022-01146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sessa EB, et al. Between two fern genomes. Gigascience. 2014;3:15. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Fang YH, Yang J, Bai SN, Rao GY. Overview of the morphology, anatomy, and ontogeny of Adiantum capillus-veneris an experimental system to study the development of ferns. J Syst Evol. 2013;51:499–510. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuboi H, Suetsugu N, Kawai-Toyooka H, Wada M. Phototropins and neochrome1 mediate nuclear movement in the fern Adiantum capillus-veneris. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:892–896. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wada M. Chloroplast and nuclear photorelocation movements. Proc Japan Acad Ser B, Phys Biol Sci. 2016;92:387–411. doi: 10.2183/pjab.92.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen H, et al. Large-scale phylogenomic analysis resolves a backbone phylogeny in ferns. Gigascience. 2018;7:1–11. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]